RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

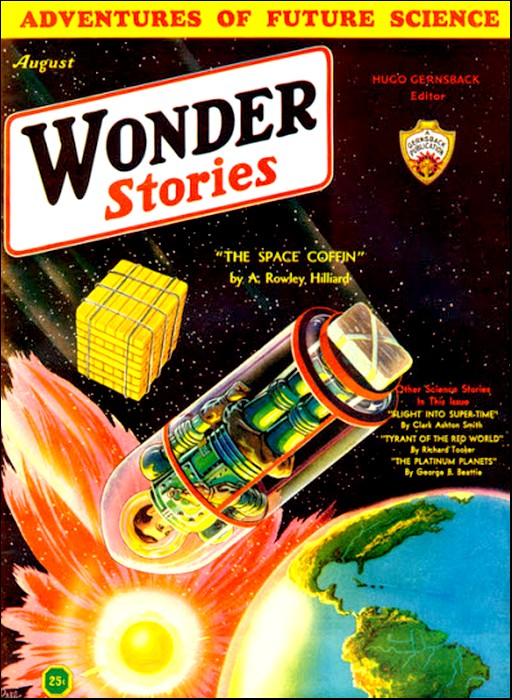

Wonder Stories, August 1932, with "The Space Coffin"

Alec Rowley Hilliard was an American writer who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. He was born on July 7, 1908, and passed away on July 1, 1951, at the age of 42 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Originally from Ithaca, New York, Hilliard was remembered in his obituary as a dedicated professional. He was survived by his wife, Annabel Needham Hilliard, their two children—Elizabeth Janet and Edmund Needham Hilliard—as well as his mother, Esther R. Fiske, and a sister, Elizabeth Hilliard. He was laid to rest at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca.

IT is difficult to tell much about this unusual story, without giving away its central mystery. You will learn, however, the extremes to which men go in order to accomplish their aims, whether such aims be for or against law and order.

Here, in this story, we have a scientific intrigue, that reaches its hands far into the American nation. In the kidnapping mystery, and the boldness of the kidnappers, the contrast to the terrible Lindbergh case is marked. The motives behind the kidnappings in this story may be compared with the fiendish brutality that accompanied the Lindbergh tragedy.

At any rate, this is a story you should enjoy.

IT was done in a moment... I turned away from the breeze to light my pipe. The night was dark, the flare of the match blinded me for a minute; so when I heard a grunt behind me I grabbed my electric torch... But he was gone!"

John Hand shrugged, and puffed calmly on the big, black pipe that had been his undoing.

"Ye say yerself and Ostermann were out walking in the garden. Weren't ye a bit foolish to allow him out of the house, Mr. Hand?"

John Hand puffed a little more quickly at the pipe—an ominous sign. His temper was short today. And McQuerdle was dragging this old story out of him again—for the half-dozenth time.

"As I've told you before," he said, without the deferential air that should be used towards a boss, "the garden was surrounded by two hundred Swedish police and soldiers—good men. A cat couldn't have got in or out."

"Ah—h!" Andrew McQuerdle, Chief of the Secret Service Division, U.S. Government, could be painfully irritating on occasion. The peace of mind of his operatives was no concern of his. "Ah!... And so ye have taken up the study of occultism and the more theoretical sciences to explain yer failure! It has been five months since ye allowed Johann Ostermann to be spirited away right under yer nose—and what have ye done since then? Ye know that only by a presidential order have Secret Service men been put on this case. And now as far as I can make out from yer reports ye've spent most of yer time in libraries, universities, astronomers' observatories, and other institutions of the more useless sort of learning. Ye are going a long way to explain a simple failure in detective work, Mr. Hand. I begin to doubt your sanity; and I cannot doubt your uselessness to this department!"

Although stung, John Hand gave no sign. "The Adjustors don't work by ordinary methods, sir; and you've got to meet them on their own ground. When a man disappears in thin air, why you..."

"Ye feel obliged to seek the aid of Einstein—is that it, Mr. Hand?"

John Hand remained impervious to the other's sarcasm. "You've got to find out how it happened, of course..." He looked earnestly across the desk at his superior. This moment was an important one in John Hand's career. For two years now he had been on the trail of "The Adjustors," a trail hard to follow; a bewildering trail full of gaps, false leads, and sudden, unpredictable shifts.

The trail was a long one: New York, Los Angeles, Tokio, Berlin, Paris, Kimberley, Stockholm; far and wide, it led, with John Hand following, dogged and baffled, always a step or two behind—until now. Now for the first time he was a step ahead; now at last he felt he could meet his opponents on even terms. He couldn't be sure, of course; you could never be sure with the Adjustors; but the mere possibility filled him with an exultant excitement, for, like all born fighters, John Hand loved a worthy enemy.

When he next spoke his tone was almost pleading. "I believe I can convince you of my usefulness tonight, sir. If the Adjustors get away with Van Swerigen, I'll admit my failure... But I've got to get to Cleveland in a hurry..."

"No-o..." McQuerdle shook his head judiciously. "No, Mr. Hand; I am afraid ye've gone stale on the case. I am going to take ye off it."

"But, sir! You'll let me go to Cleveland tonight, won't you? I'd stake my life on getting 'em this time... Give me a last chance, sir!"

Andrew McQuerdle shook his head. "Tomorrow morning the President leaves Washington on his Western trip. Ye will join his bodyguard, Mr. Hand. Ye'll have no time for Cleveland."

It seemed to John Hand that, in this moment, he had reached the climax of long years of dissatisfaction and unpleasantness on the job. He was bound to face the fact sooner or later that he neither liked nor trusted his immediate superior in the department. He faced it now. Andrew McQuerdle did not command his respect—never had.

It was not merely his rough and graceless manner of handling his men; there was a strange something behind that—something sly and unsatisfying, which John Hand felt rather than understood; He remembered Peters, discharged for bribe-taking. Peters was honest as the day is long, and Peters had known something; but John Hand had tried to pump him in vain.

He decided to make a last appeal... "But, sir—"

"That is final, Mr. Hand! Ye will make yer formal report on the case, with all possible speed, so that we can take care of the matter... Ye may go."

John Hand did not move. "I doubt if you could take care of it," he said quietly. His face was perfectly calm, hut the heavy clouds of grey pipe-smoke billowing towards the ceiling told a different story. Prepared as he must have been for anything that this man might do, he could not avoid a shock of surprise. He was being demoted—reduced to the ranks—taken off the job after two years of effort, and on the very eve of success!

McQuerdle snorted. "What, man? Of course we can take care of it! Ye believe there will be a kidnapping tonight in Cleveland, do ye not?... Then what is to prevent us from capturing the kidnappers?"

John Hand took his pipe from his mouth and looked at it thoughtfully. "They won't be there," he said.

"Eh...?"

"They will and they won't," said John Hand obscurely.

McQuerdle was irritated. After breathing hard for a minute, he said stiffly, "that will be all, Mr. Hand. Ye will make yer report..."

"I will not make a report," said John Hand.

Andrew McQuerdle's mouth dropped open, and he hitched himself forward in his chair. "Ye will not..."

"I will not." John Hand was studying the ceiling with mild eyes, apparently interested in the whirls and convolution of the grey-blue smoke collected there.

McQuerdle mastered his breathing with an effort. "Mr. Hand, I cannot allow ye to question my authority!" He paused, but John Hand said nothing. "Ye will hand me the complete report before three o'clock."

John Hand's interest in the ceiling had not waned, apparently. He was too absorbed to speak. Andrew McQuerdle's breathing was again becoming difficult. "Ye may go!" he said hastily.

JOHN HAND went. He left the Treasury Building; crossed Pennsylvania Avenue; entered his bank. He inquired about his balance, and withdrew the whole. He took a taxi to his home, and for three-quarters of an hour talked earnestly to his wife. He left her most of the money; and they parted lovingly and as cheerfully as possible under the circumstances. He went to the Washington airport; engaged a plane; and said to the pilot, "New York."

John Hand did not want to go to New York. He could ill spare the time. But he and his wife had agreed that he must see Gordon Wintermaine at once. It was with no little trepidation that he looked forward to the interview.

John Hand was one of "Wintermaine's Young Men"—as they were known in 1940, when the "Personal Mortgage" was still in its experimental stages.

Now that the Personal Mortgage is an accepted part of our daily lives, it is hard to understand the excitement and the almost universal hostility that it caused when Gordon Wintermaine introduced it in 1935. Now it seems indispensable; then it was denounced as madness. They called Gordon Wintermaine a lunatic; but they could not disregard him, because he was one of the most interesting figures of his time.

He was the scion of a great international banking house—born to control great sums of money; sway governments; make and unmake wars; and do all the tremendous things an international banker does. For a number of years he did those things, but he was not cut out for the work. His blood was warmer than an international banker's should be.

His associates looked on in horror while he loaned money to little, struggling European principalities, rushed to the aid of expiring small-town banks, and committed other rash acts—"for purely sentimental reasons, apparently," they complained. They feared that the great House of Wintermaine, which had stood for centuries as a rock of financial stability, was in danger. These fears became known. In 1934, Gordon Wintermaine got out.

He was a man more interested in human values than in money values. A good man, to him, seemed a better investment than a stock certificate. He hated those bankers' fetishes, collateral and security.

"A good man needs money," he would say. "He ought to be able to get it, even if he doesn't happen to own a house or a barn or a diamond ring..."

He was a social thinker. Articles by him appeared regularly in the popular magazines. He had one dominating idea...

"The trend of our modern civilization is towards specialization—more and more. If a man is going to amount to anything, he must be able to do one thing and do it well.

"That takes training—years of it... And in the meantime—what?

"I know a dozen young men who are talented, energetic, well-trained—who have every prospect of success; yet they are unhappy. Why? They don't have any money.

"Their expectancy of earning power is very high. In ten years they will have all they need; in twenty, more than they need... But now they worry and skimp and fret in their poverty; and their work suffers, and their souls suffer. Some of them are married, and they have the added distress of seeing their wives worry and skimp and fret. Others want to marry and can't, which is a most injurious condition, as everybody knows...

"I truly believe that they are all being permanently injured.

"To get anywhere these days a man's got to be an expert in some line. Well, why not give him a chance? Why make him suffer for it?... Suffering never helped anybody."

He plunged into his Personal Mortgage scheme with all his characteristic energy and enthusiasm. John Hand had been one of his first "clients;" and now, as he restlessly paced Wintermaine's waiting room, he remembered his first interview with the great, shaggy, square-jawed man. He could still hear the full, deep voice.

"Hand, I've looked you up. I have ways of finding things out. I know more about you than you do yourself... I think you're a good man.

"Now here's what I'm going to do. I'm giving you a regular income. I want you to live comfortably, and in some style—the way you deserve to live, if you work.

"Been having a hard time, haven't you? Wife sick—eh? Well, send her to a sanitarium, now!

"When your own earnings get up to a certain point—my secretary will give you the figures—the income stops; and you start paying me back, with interest... All right?

"If you don't make good progress on your job, the income stops anyway. This isn't charity. It's common sense.

"Also, remember this. If you fall down on your job, you'll be hurting me... People are against me. They think I'm crazy. Well, I'm not; but the burden of proof is on me, and on you men that I'm trusting... Are you with me?"

John Hand was. He had enough confidence in himself and his future for that. Also, he fairly boiled with indignation when he heard Wintermaine called "usurer" and "mortgager of souls", as he was constantly, from pulpit and press. Gordon Wintermaine did not need a publicity agent. His enemies publicized him.

In spite of the storms of protest, however, people showed an almost frantic willingness to "mortgage their souls." Then began the real work—the picking and choosing. Wintermaine had a tremendous personal fortune, and he planned to use it all; but he didn't mean to throw it away. Consequently, he was the busiest man in the United States before his project had been launched a month.

Knowing this, John Hand spoke directly and to the point—when he was finally admitted to the inner office. He told exactly what had happened that day; he explained all the circumstances; and he finished, "You see, sir, I've been after them for quite a while now, and I'd like to catch them myself." By which he meant: that having put his whole heart and soul into the job for two years, he must finish it if he were to retain one atom of his self-respect.

The older man's brows met in a frown. "You expect to catch them single-handed?" he questioned.

"Yes," said John Hand. "The man who catches the Adjustors will have to work alone; I am sure of that. McQuerdle would bungle it, and the chance would be lost—forever."

"Hmm..." Wintermaine leaned back in his chair, and looked quizzically at the other. "Mr. Hand, are you sure you are not chasing a ghost?"

"Ghost!" John Hand was really indignant. "A ghost that has kidnapped eight of the world's wealthiest men in three years? A ghost that has collected a cool eight million dollars in ransom? A ghost that—"

"Hold on a minute!" smiled Wintermaine. "I'm not denying the facts... But," he went on very seriously, "is it probable—is it possible—that these eight crimes have been committed by the same hand?"

"I'll admit it seems impossible..." began Hand, but the other went on:

"Isn't it more likely that The Adjustors is a sort of catchword or trade mark adopted by any enterprising gang that wants to throw the local police off the track? I know a number of experienced criminologists who are of that opinion. They actually scoff at the idea of there being any real Adjustors ,carrying on their operations all over the world..."

"Mr. Wintermaine," John Hand lowered his voice, and glanced involuntarily around the room, "here's a fact that your criminologists don't know. Every man that has been kidnapped by the Adjustors has been confined in the same house!"

Gordon Wintermaine shook his head. "That is impossible!"

"It is true! Each one has described it to me separately. I know every room, every stick of furniture, every book, as if I had been a prisoner there myself. It is a four-room apartment. It—"

"But, man alive!" put in Wintermaine excitedly. "It's a physical impossibility. Every man kidnapped has been returned home within twelve hours after payment of the ransom. Isn't that a fact?"

"That's a fact."

"France—South Africa—Japan—Sweden—California!" Gordon Wintermaine barked out the names disgustedly. "Where is this house?"

John Hand merely shook his head, and Wintermaine went on more calmly: "You must be right about the Adjustors. I'll admit that. But the house—no. What they've done is to fix up several places to look the same. I don't see why, but—"

"There are two small scratches on the library table, close together. Inoui Mitsui of Tokio noticed them. Van Cleef Whitney of New York saw them. Whitney told me also of a spot on the bedroom rug. The Crown Prince of Siam explained to me how he made that spot—with a balky fountain pen. I have quite a list of similar details," said John Hand quietly.

WINTERMAINE threw himself back in his chair, and exhaled audibly. For a time he said nothing, and his face was a picture of bewilderment. Then: "But, good God, it's a miracle!... Don't any of these men have an idea how they got there?"

"They know nothing at all. Here is a typical case. The victim is riding in his car, and smells a strange, sweet odor. He wakes up in the house of the Adjustors. One man went peacefully to sleep in his own bed, and woke up in the place...

"It is a richly furnished apartment, with a fine library—very comfortable. There the victim stays until he authorizes payment of the ransom..."

"How?" interrupted Wintermaine.

"By telephone."

"What!"

"Yes; he may talk to anyone he wishes. His wife, his lawyer, his business associates, even the police. It is a bit ludicrous. He is quite comfortable. He is alone, but all his wants are provided for. One man stuck it out for five months—but he finally paid. Now they are not so stubborn. Hardy, the South African diamond man paid up and was back home, all in less than a week. If Capone were alive, he would choke with envy at the beauty of the racket! One million dollars a throw—in gold!"

"Lord!" Gordon Wintermaine shook his shaggy head. After a short silence, he said, "One million dollars in gold would weigh more than a ton, wouldn't it?"

"A ton and a half."

"Well, how—"

"It just disappears."

Wintermaine shrugged. "Yes, of course I have heard that; but there must be some better explanation. Miracles don't happen—at least, we like to believe they don't..."

John Hand took his pipe out of his mouth, and looked at it thoughtfully. "It's a good enough name for something you can't understand," he said. "Picture a metal box—or trunk—sitting in a field. The agents of the kidnapped man send a truckload of gold, and fill it up. It's location has been carefully explained to them, by telephone or by radio. That night the trunk disappears. It doesn't matter how many hundred policemen are surrounding the field—or whether the roads are blockaded, or what. It disappears... And the next morning the kidnapped man wakes up in his native city, and takes a taxi home."

Gordon Wintermaine was silent for a long time, tapping the polished surface of the desk with his stubby fingertips. Finally he took out his watch and looked at it.

"It is ten minutes of three," he said, and pushed a telephone towards John Hand. "If you were to call up McQuerdle now, you could square yourself with him, couldn't you?"

John Hand looked at him stonily. "Is that what you want me to do?"

"Hell!" Wintermaine's temper flared up. "Am I your master? That's what they say about me. I buy the souls of men with my filthy money. That's rot!...

"I pick men whose judgment I can trust—and I don't boss 'em. I have no legal or moral right to boss 'em. But I can still give the advice of a sane man, I hope. Listen!

"If these Adjustors, or whatever they are, can make a ton of gold disappear, they can probably make you disappear. If they can make away with the Crown Prince of Siam, they can certainly handle you."

John Hand's lean jaw clamped harder on his pipe-stem. "I think I can get 'em," he said.

"You think!... Well, here's something we both know. if you balk McQuerdle, he'll break you—and he'll jail you..."

"If he can find me," said John Hand.

Wintermaine shrugged broadly, and suddenly laughed. "All right, all right, Hand! I wouldn't stand in the way of a determination like yours. Do whatever damn' fool thing you want to. As to the money you owe me, it isn't much, is it?"

"I'm nearly paid up. It's three thousand."

"How much has your wife got?"

"Twenty thousand."

"Good! She'll probably need it. I won't dun her. I'll take a risk on you—and a damn' poor risk it is, too!

"And now that you're in this thing for good," he said suddenly, "maybe this will interest you..." He took a sheet of paper from a drawer, and pushed it across the desk. "... Addressed to me—postmarked Irkutsk, Siberia, if that's any help!"

It was typed. John Hand read:

You are next —The Adjustors.

John Hand was silent for a long time. Then he looked up, and said, "I wouldn't worry very much about this, sir."

"Sure of yourself, aren't you?" Wintermaine smiled.

But John Hand did not explain himself further. This development was a surprise to him; and he wanted time to think it over.

Silently the men shook hands.

JOHN HAND flew to Cleveland, and paid off the plane. He telephoned the office of Robert Van Sweringen, and learned that the great man had left for his lake-shore home at three o'clock, his wife being sick. It was now four. John Hand telephoned the lake-shore home...

"No, Mr. Van Sweringen is not at home. He is at his office in the city... What? Mrs. Van Sweringen—? Who is this speaking, please?... Oh! Secret Service? No, Mrs. Van Sweringen is not ill. Would you like to speak to..."

John Hand hung up; and, leaning against the wall of the booth, cursed softly in three languages. Then he took a cab to the City Engineer's office, and studied a large-scale map of the lake-shore suburbs.

There was much territory to be covered, and he needed help. It was discouraging. Yesterday he could have commanded half the city's police force and no questions asked, but now...

He decided to bluff.

At half past four he walked into a police precinct in the northern part of the city, and flashed his gold badge at the Sergeant. "Hand, Government Operative," he said crisply.

"Yes, sir!" said the Sergeant, saluting.

"Colonel Van Sweringen has been kidnapped. He was overpowered in his car near his home, shortly after three o'clock..."

The Sergeant gulped. "Whew! Colonel Robert Van—?"

"I will need every man you can muster to search the fields in the lake-shore area."

"The fields, sir?"

"Yes. I have reason to believe we will find him there. Now, make it snappy!"

"Yes, sir—yes. But I'll have to call Headquarters. I mean, I don't have the authority..." The Sergeant's voice trailed off as he grasped the phone.

John Hand nodded negligently. He was filling his pipe. While he lighted it, he was doing two other things. He was deciding that his unfortunate lateness would necessitate the abandonment of his original plans; and he was watching the Sergeant narrowly through the first billowing clouds of smoke. The latter had said only a few words when he stopped and began listening. All the conversation, it appeared, was coming from the other end. The Sergeant's mouth dropped open slowly, and then clamped shut with a click as he said "Yes, sir," and hung up. He turned and looked at John Hand queerly.

"Orders to arrest me—eh?" John Hand was thinking that McQuerdle never wasted time—never wasted anything for that matter. A remarkable man...

The Sergeant was making ridiculous apologies. "Must be some mistake... Orders is orders... Have to send you to Headquarters... You won't give any trouble, sir?"

"Trouble?" said John Hand, raising his eyebrows. "Why should I?"

The Sergeant had no definite answer for that; and called two officers out of a side room. "Mike," he said, "you and Jerry take the car and take this man down to Headquarters. He won't give any trouble."

"And, in the mean time, what about the good Colonel?" inquired the prisoner.

"They're taking care of that already, sir. All the roads are being watched."

"The police have an unfortunate road-watching fixation," said John Hand.

"Yes, sir." said the Sergeant vaguely.

Outside, it was getting dark. The two officers flanking him held his arms firmly, and marched him towards a small roadster at the curb.

"This looks like the end of a perfect day," he said. "Hold me tight!"

Jocularity, with John Hand, was always a cloak for less pleasant emotions. He was feeling rather grim. McQuerdle, he knew, would show no mercy. There had always been a veiled enmity between them. Now, the kidnapping would succeed, and John Hand would be blamed. McQuerdle wouldn't miss a chance like that Also, there was insubordination, that unforgivable offence... The end of a perfect day! The end of a career, rather!

John Hand stood still suddenly, and knocked the ashes out of his pipe against the palm of his left hand. Anyone who knew him would have scented trouble immediately, because it was not half smoked, and he always smoked that pipe to the bitter end. A glowing coal lodged in his hand, and he said, "Ow!" The two officers had stopped about a foot ahead of him, and they were looking at his hand with concern. He said, "Ow!" again; and then dropped his pipe completely, adding, "Damn!" The two officers now looked at the pipe.

JOHN HAND was one of those tall, stoop-shouldered men that look frail and aren't. He had American Indian blood in him—a lot of it. He had, in fact, been brought up on an Indian reservation. The sports on an Indian reservation are rough; and John Hand's six and a half feet of loose-knit power was something of a by-word in the Service. The word "handling," as they used it, was a poor pun but it had a very real meaning.

His arms described half-loops behind the two policemen, breaking their grips on his biceps immediately. His hands terminated the loops at their throats, on the outside. His long fingers dug cruelly into the flesh in front, just above their high collars. It was a movement requiring exquisite precision.

The two policemen made odd snoring noises; they wasted no time in drawing revolvers. The one on the right waved his harmlessly, but the other was better situated. John Hand felt a hard muzzle pressing his left side. He stepped back; arched his shoulders; and pulled the two heads together in front of him. They met with an unpleasant crack. A simple shove disposed of them after that.

John Hand snatched up one of their caps, retrieved his pipe, leaped over them, and tumbled into the little roadster. The key was in the switch... Who steals police cars?... A goggle-eyed citizen, crossing curiously from the opposite sidewalk, saw him drive off in the dusk.

He headed north, the police cap tipped jauntily over one eye. He found the button operating the siren, and made very good time. In ten minutes he saw the silver gleam of Lake Erie, and swung left on the broad shore drive. A little, croaking voice behind the dashboard said accusingly:

"Police Car 718 stolen by fugitive from justice... Headed north from Twelfth Precinct... Probably on Shore drive, moving east or west. Car 723 proceed up Lincoln Avenue to intercept on east. Car 742 proceed up Bond Avenue to intercept on west... All other cars in Twelfth District stand by for orders..."

Bond Avenue, if John Hand remembered his map correctly, was just two blocks ahead now. He pushed the throttle down flat, and his siren rent the air. As he whipped past Bond Avenue he saw from the corner of his eye Car 742 approaching, but just a little too late to "intercept on west."

"Wonderful thing, the radio," he chuckled.

The radio said:

"Fugitive in Police Car is John Hand, wanted by Federal Government; also wanted for assault on two officers and theft of car... Tall—stooped—dark—wearing police cap... Men watching city exits in kidnap case prepare to intercept..."

"Humph!" said John Hand. To his right, beyond an iron fence, a large estate lay between him and the lake. In the gathering darkness he could just see the outlines of the Van Sweringen mansion, set among trees on a knoll. He was thinking hard now about another car that must have passed this way, roughly an hour before. He swept by the Van Sweringen driveway, with its ornate pillars... The other car hadn't turned in there!

"Fugitive John Hand in Police Car 718 moving west on Shore Drive at high rate of speed," said the radio. "Car 742 following..."

John Hand glanced back, and verified that. Two red-tinted lights were there, veering crazily. "—Also at high rate of speed," he chuckled.

"Cars 653 and 621 from Thirteenth District will proceed east to meet him," added the radio wickedly. "Cars 789, 731, 666, and 667 will close in from the south."

The fugitive frowned, and began studying the roadside to his right. Trees now, rather thick; the iron fence had given away to a stone wall. He reached up an arm, and adjusted the spotlight to shine along that wall Far ahead, among the white lights of city-bound cars he saw red ones weaving. The wailing of many sirens made the night hideous.

Suddenly he caught the flash of a white, barred gate in the wall. Stamping on the brake pedal, he pulled at the wheel. Only the little car's lead weighting kept it upright, as it swerved from the road and splintered its way through the gate. A hiss and a bang sounded the doom of a front tire; the steering wheel wrenched loose from John Hand's grasp; and only his right foot, caught between the clutch pedal and the steering post, held him in the car, as it struck a tree, skidded in a violent arc, and stopped.

Cursing at an ominous twinge in his right ankle, he clambered to the ground, and struck north through the trees. If he could reach the lake, he thought, he might yet escape. He was a good swimmer, and there would surely be boats within reach. As he remembered the map, there was about a half mile of wooded parkland and fields between the road and the lake at this point. It was part of the territory he had wanted searched.

"Well, it'll be searched now!" he chuckled, not without satisfaction. Behind, he heard the throb of many motors, mingled with horn-tooting and shouts. Beams of white light slashed among the trees. He was limping now, and when he tried to quicken his pace, he suffered his first misgivings. The ankle was bad.

There was open ground ahead. He judged it to be a field of some size, but couldn't be sure because the night was black. There was no moon. The Adjustors always worked in the dark of the moon, he remembered.

A CAR was coming through the woods—perhaps several. The shortest, way to the lake must be his way, he decided; and headed across the field. It had been plowed last spring, and now the furrows were hard and treacherous. His ankle felt like a tight blob of flesh spliced to his foot with red-hot rivets. He couldn't get much further on his feet, he realized.

Suddenly, light bathed the ground around, and he threw himself flat. Fifty feet ahead he saw a small clump of bush. The light swung away. He crawled into the bushes, and sat up, propping his back against a smooth, rounded rock. Three cars came out of the woods. One of them bumped around the edge of the field to the farther side. Came voices and the banging of doors.

John Hand shrugged philosophically, and packed his pipe. He scratched a match on the smooth rock, and, as it flared, there came a dull ringing sound. Ignoring the agony of his ankle, he leaped to his feet, and stared down at the thing. It was not rock; it was metal!

"Well I'll be—!" He doused the match, praying it had not been seen. Carefully he felt over the glassy-smooth surface of the thing on the ground. It was a cylinder, pointed at the ends something like a torpedo, and about eight feet long. On top were two little posts, with a fine wire strung between. Searching further, he found a small, cup-like depression in the side, with a metal handle sunk in it. Without hesitation, he twisted the handle, felt the soft sliding of a bolt, and pulled. The close-fitting door—almost an entire side of the thing—swung out slowly and quietly on its well-oiled hinges. John Hand heard a faint, steady hiss, and then another sound—the regular breathing of a man. He flashed his pocket light inside.

Robert Van Sweringen was suspended in the center of the cylinder, held by straps which were attached to the ends of springs extending from the inner surface. He was asleep, as his slow, long breathing showed. "Lo! The Colonel!" said John Hand.

An exploring light-beam caught the bushes, and held. John Hand froze, concentrating on the voices, which carried far in the night.

"... Nothing there, sir..."

"How the hell do you know there's nothing there? Have a look."

The light swung away, but little ones were bobbing along the ground now. John Hand unstrapped the Colonel, lifted him out upon the ground, and rolled him away from the bushes on the side opposite the approaching lights. Unable to resist the temptation of the high, starched collar, he took his pencil and hastily scribbled upon it: "To Andrew McQuerdle—With love—J.H."

Returning to the cylinder, he removed his gun from his armpit, laid it inside, and crawled in after it. Laboriously he strapped himself in position among the springs; then reached out and pulled shut the heavy door. He shot the bolt; and, to his delight, found a small catch which held it in position.

"They'll need a can-opener to get me out now!" he chuckled. "And perhaps before they find one, something else will happen."

The darkness was complete. He fumbled for his lamp. That soft, steady hissing sound puzzled him. The place was stuffy, and he felt suddenly frightened about air. The door was rubber-sealed. Even before his lamp revealed the little tank, however, he had guessed that the hiss must be an oxygen valve. A queer sieve-like arrangement near his feet must hold a lime solution for absorbing carbon dioxide, he imagined. There was nothing else to see, and he switched off the light. His ankle throbbed rhythmically.

Occasionally he glanced at the green glow of his wristwatch. A half hour passed, and still nothing happened—no sound came. He was surprised, but thought he could understand. They had tramped through the bushes, peering perfunctorily; then they had found the Colonel, and forgotten all about the bushes.

He was reasonably comfortable. He had plenty to think about; and the darkness did not worry him—nor did the loneliness. The oxygen made him a little lightheaded. He felt quite pleased with himself. He rested. Necessity had taught John Hand to take his rest where he found it.

A moment after he had noted the hour of eleven by his watch, there came a deafening, nerve-shaking clang on the wall of his prison. Startled, he found himself shaking up and down between his supporting springs, so violently that his teeth chattered. It did not last, however, and soon he was quiet again. He resisted an impulse to open the door. Something hard was pressing into the small of his back; and, hunching up one shoulder, he managed to reach it with his hand. It was his revolver.

AT first he thought that the cylinder must have rolled over; but the weight of his arms and his general sense of equilibrium told him that that could not be the case. Why, then, was his revolver not lying properly on the floor a foot below his back? He released it, and heard it strike the cylinder. His flashlight showed him where it was, stuck again the top, above his head. He frowned at it irritably, and pushed it away from his face. No telling what it might do next. With knit brows, he puzzled over the matter until nearly midnight, when he began to feel cold.

The wall of the cylinder, when he touched it, felt like dry ice. Here was something new to puzzle about. October nights do not get as cold as all that. John Hand began to feel annoyed.

"No wonder they give 'em gas!" he snorted. He wanted to smoke, but knew he couldn't. His synthetic atmosphere was too nicely gauged for that. Again he had the impulse to open the door, but resisted it. He compromised with himself by unfastening the catch which held the bolt. If anybody wanted to take him out now, he was quite willing.

His flashlight had now joined his revolver at the top of the cylinder, and he even felt his wrist-watch tugging in that direction. His arms, head, and feet felt light. His ankle, which had suffered greatly by the unsupported weight of his foot, seemed relieved. At last, his right arm surrendered to the upward pull of the little watch, and hung lazily above him.

Further speculation on this matter was interrupted, however, by another disturbance from outside. He clapped his hands over his ears and grimaced at the deafening clamor, as something again struck the walls of his prison. Once more he was shaking in the springs. The bumping, clanging, and shaking continued for some minutes; and then, suddenly, all was quiet. His revolver fell from the roof, striking him a sharp blow in the stomach. His flashlight bounced from his hip, and broke against the metal wall. Filled with a sudden premonition, he reached for the door handle.

It was turning!

He grasped his revolver, and pointed it. Light streamed in, and he felt a rush of warm air. He found himself staring directly into the face of a man. John Hand thought it was a surprised face, with its wide eyes and open mouth; but he couldn't be sure as to its expression, because it was upside down. Beyond it, he caught a glimpse of bare walls and floor. What supported the face he could not see.

For a long moment he stared into the inverted face, stupidly pointing his gun at it. Then, noiselessly, it was removed from view—upwards. He heard the soft closing of a door, somewhere in the room. Then complete silence.

He began unfastening the straps which held him. The time had come, he felt, for action. Obviously, his cylinder had been moved—where and why he must discover...

A heavy, sweetish smell came to his nostrils, and he sniffed the air suspiciously. Then he renewed his struggle with the straps, trying not to breathe. The buckles were stubborn, and his fingers were numb. The numbness was not due to cold. Swiftly, it spread up his arms and into his body, making him sick and dizzy. Too late, he thought of closing the door. He grasped its handle, but could not move it. It was as heavy as all the world. He was free of the straps now. As he tugged at the door, he seemed to be floating in the air—floating right out of the cylinder. He knew he must be dreaming. Darkness came; and he floated in it, rolling over and over and over, sickeningly, helplessly...

HE next saw the light in a room he knew, from a bed he knew. His head ached a little. He stirred uneasily, and looked around. He rolled over stiffly, and gazed down at the little ink spot on the heavy Persian rug near the bedpost. Yes, this was the bedroom in the house of the Adjustors.

His ankle was neatly bandaged and splinted; he knew that, even before he threw back the covers and saw it. His clothes had been taken from him, and he was dressed in the close-fitting grey garment which was worn by every captive of the Adjustors, and which could never be taken off. It covered the legs to the ankles and the arms to the wrists, and came high around the neck; it was secured with the metal fastenings called zippers, so arranged that they could not be unfastened by the wearer. Victims had complained to John Hand that they never got a bath; but they had to admit, at the same time, that they didn't need one. No speck of dust had ever been seen in the house of the Adjustors. It was the cleanest place in the experience of any man who had been there. There were no windows. Perhaps that was the explanation, but it didn't entirely satisfy John Hand.

Curiosity was his first emotion. He hopped through the rooms, inspecting them—the living room, the library, the other bedroom. Everything was neat, orderly, and in good taste—almost oppressively so. The silence of the place was so complete that the noises he made startled him. He tried to move quietly, but that was almost impossible on one foot. He had an unreasonable fear that someone might hear him.

HE argued with himself, annoyed. Why shouldn't someone hear him? They knew he was there, didn't they? It was no secret to them. Nothing he could do would make any difference.

Far from cheering him up, that thought depressed him more. John Hand was not accustomed to feeling helpless. It made him uneasy—jumpy. He realized that he was turning his head constantly, suddenly staring over one shoulder or the other, as if wanting to see in all directions at once. Also, he would stand for long periods of time perfectly still, listening—straining his ears in the silence—hearing nothing.

He sat down, tense and shaking, on the edge of a chair. There was something queer about the place. He had sensed it in the descriptions of the men who had preceded him here. He sensed it now; but it was too subtle—too intangible—for comprehension. Everything seemed so correct and ordinary, yet there was something wrong. He knew it. He sat there, struggling to put the feeling into a concrete thought.

As a boy, he had known fear of the dark. Every normal boy has felt it: that sudden, panic-stricken consciousness of an alien Presence—an all-encompassing, evil Thing, which cannot be seen or heard or touched, but which is still very real and terrible.

But John Hand had not been a boy for more than twenty years. Furthermore, it was not dark here; globes in the ceiling spread a soft natural radiance over everything. Yet he was afraid.

Not of the Adjustors. True, they had every reason to hate him. He had cost them a million dollars, and he was a very definite menace to their safety. True, he was entirely in their power. Still, they were men; and John Hand could deal with men. He had come into this thing with his eyes open. He had gambled on the chance of their sparing him long enough for him to penetrate their secrets. He had felt confident that, once here, he could solve the problem of their mysterious hide-out and their mysterious powers.

"Give me six hours in that place," he had said confidently to his wife, "and I'll give you the answer..."

Yes, the mystery was here; but he was not solving it. Instead, he was surrendering to it, and shaking with fear like a nervous woman! He clenched his fists and knit his brows, striving to think—striving a second time to give concreteness to his shadowy impressions.

Anybody who could have read his thoughts, then, would have called him a lunatic. It seemed to him that these four rooms, with their quite ordinary furniture and decoration, were not real at all—that they were merely screens put there to hide some terrible reality which lay behind. The studied Naturalness of everything he saw was a cloak covering the awful Unnaturalness beneath. Each table, chair, vase, and book was part of the deception... And it was a clever deception, careful and painstaking.

A less impressionable man than John Hand—or an unsuspicious man—might have noticed nothing. But John Hand knew that the whole thing was wrong. How that knowledge came to him, or what was meant by it, he could not say. In fact, for whole minutes at a time, he feared he was mad. But then he remembered that others before him had had the feeling.

He was not a man to surrender to panic fear. Fear remained, but he battled it constantly with his reason. No deception is perfect, he told himself. There must be flaws in this one, and sooner or later he would find them. The very fact that he sensed something wrong proved there were flaws. His subconscious mind—or instinct—perceived them, while his reason did not. He had run across that phenomenon many times in his detective work. And he knew what to do.

Watch for details. Never let one little unexplained fact get past you. It might be a clue. Forget nothing, until it has been well explained and accounted for; and then put it out of your mind completely, so that it won't be in the way. Treasure all your little unexplained facts. Work on them; try to fit them together; and be on the alert for similarities among them. That was John Hand's inductive method.

Whether or not They would give him time to use it was another question, he realized.

He began examining the one-piece, tight-fitting garment which he wore. He could not decide what the material was. It might be wool, but it seemed very stiff—stiffer than any cloth he knew. He scratched it with his fingernail—there was nothing else to use—and it seemed almost hard. He made a little shiny place, scratching. He hobbled into the bedroom, and examined the bedclothes. They were the same.

He returned to the living room; and examined his breakfast, which he had ignored hitherto. It was kept hot by a little electric steamer. He switched off the current. The food was in a bowl—unpleasant-looking stuff, of the consistency of gruel or porridge. The Adjustors always served food in this form, he knew. The ingredients might vary, but the form and manner of serving was always the same. He tried it gingerly, and found it extremely good, with the taste of bacon predominating. He was not hungry, however.

THE calendar clock, set in the wall, told him it was ten-thirty, A.M., October 24. He wanted to smoke. They had not left him his pipe or tobacco, and that irritated him. He didn't want to smoke out of their damned tube! Still, any smoke is better than no smoke at all; and he went to the wall, where two flexible tubes hung down from a metal panel. He knew all about them, of course. One supplied drinking water; the other, tobacco smoke. You signify your wishes for one or the other by pressing signal buttons. There was a supply of changeable mouthpieces in a box. He was glad of the opportunity of inspecting these queer arrangements at first hand. He didn't like the tobacco.

He moved over to the telephone, and idly picked up the receiver. He was about to replace it, when:

"Yes?" said a quiet voice.

John Hand was a bit taken back.

"You wanted something?" insisted the voice.

John Hand said the first trivial thing that came to his mind. "I don't like Turkish tobacco."

"What tobacco do you prefer?"

"Virginia and Perique; half and half." John Hand grinned suddenly. This was really funny, he thought.

"It will be attended to," the voice assured him. There came a click.

He replaced his own receiver, feeling a trifle dazed. So he was to be treated like a paying guest! How long?

During the remainder of that day and the whole of the following day, he carried on a minute inspection of the four rooms. He did not sleep, but he ate quite heartily. The food was undoubtedly good. He could recognize various meat and vegetable flavors. There was, however, one flavor running through it all that was new to him. He could make nothing of it. The food came to him by way of a cupboard in the living-room wall. It had a sliding panel which raised with a buzzing sound at meal times. When he had finished with his dishes he replaced them, and the panel closed.

Air was supplied through small, grated vents in the ceilings. That sweetish gas of theirs could also be supplied at a moment's notice, he thought grimly. The knowledge of his complete helplessness did not induce a feeling of resignation in him, as it might have in many men. It increased his restlesness. He was a storehouse of nervous energy. The thought of sleep was abhorrent to him. He pursued his investigations doggedly, even when they seemed to be leading nowhere.

He examined the books in the library. There was a fine variety of them—many that he would have liked to read under different circumstances. What interested him now, however, was the fact that they were uniformly bound, with thick, heavy covers.

He examined all the decorative vases, and the bowls from which he ate. They all had one characteristic in common: thick bottoms, out of proportion with their other parts. He wondered if he dared break one of them. He might discover something that way.

He was puzzled to know whether he was being watched He had found nothing to indicate that he was; but it seemed unlikely that they would neglect that precaution. He tried to simulate a certain casualness while pursuing his investigations, so that an occasional watcher would not he made suspicious.

One form of relaxation he did take, more in an at tempt to lull their suspicions than for any other reason. In the library, he found a chess set. Pasted on the back of the board was a short typewritten notice:

You may play by telephone if you wish. There is a good player at your service.

He set up the men; and played a game with the Quiet Voice at the other end of the wire, getting rather badly beaten. He was proud of his chess game, and excused himself on the grounds of nervousness.

When the third day came and he had discovered nothing of tangible value, his spirits began to fall. His confidence in himself was shaken. Truly, these were the perfect criminals! They could hold him a week or a year; it made no difference, apparently.

He felt suddenly very small and very unimportant. He was a weak little pawn in their big, expert game. He had come to "get" them, and they had treated him with contemptuous politeness... He had cost them a million dollars; and they blended his tobacco for him, and played games with him! The thought made him flush hotly.

YES, these were super-criminals. They were in no hurry, because they had no fear of discovery. That must be the secret of it, thought John Hand. From long experience he knew that a criminal's greatest weakness is his hurry. His fear of discovery is the crack in his armor. Remove that, and you have given him a new and terrible strength.

They wouldn't let him go. Why should they? It was safest for them just to keep him here, where he couldn't do any harm. Now there rose before his mind's eye pictures of his home and of his wife's face—anxious and a little frightened, as he had last seen it. Mentally he could hear her voice, telling him to be careful, as she always did. That had sometimes irritated him, he remembered with astonishment. He had thought it unnecessary and superfluous! He conceived a new horror of his prison.

But he was not a weak man. Shortly after noon that day, he seated himself in a chair in the living-room, and attacked his problem with a new energy—an energy born of desperation. He must get to the bottom of the matter soon, or admit defeat.

At three o'clock he had not moved. Slumped deep in his chair, with knit brows and blank gaze, he still struggled with the mystery... At four, his lower jaw was outthrust, and his breathing was harder... At five, the faint suggestion of a smile appeared about his mouth... And, a few minutes before six, he leaped to his feet, chuckling, with the light of triumph in his eyes.

He went quickly to the library; and taking a book at random from a shelf, tore out half a page. He crumpled the paper in his hand, and rolled it up into a little ball. He held it out in front of him, and then let go of it. He smiled at it sardonically.

The little ball of paper floated before his face. John Hand chuckled at it delightedly. Caught in an air current, it circled towards the ceiling. He reached up and grasped it, and hid it in a book.

He gazed around him with newly seeing eyes. Understanding swept over him like a fresh, clean wave. The Mystery was a mystery no longer. And Fear was gone.

John Hand went into his bedroom, and closed the door. He was virtually certain that they could not watch him in here. He had examined the walls with the minutest care, and had found nothing resembling a peep-hole.

After an hour's struggle he found how he could open the slide fasteners of the garment they had put upon him. He was excited. He had read a great deal of science fiction, which was the most popular literary form of the day. In hundreds of stories that he had read the characters found themselves in positions where the Earth's gravitational force did not exist; and it had always seemed to John Hand that they took it too calmly. They floated around in the air without seeming to be even interested in the phenomenon. The science fiction authors seemed to think that the sensation would be annoying; they emphasized its discomforts. John Hand thought it would be fun. But he had never hoped for the chance to find out. Now, therefore, he was pleasurably excited.

As he peeled off the garment, he felt as though he were expanding. He stood up, with the garment still About his legs. He felt a foot taller. His arms floated lightly. They had a tendency to fly up above his head; a natural muscular reaction, he thought. He squatted down, and took off his shoes. They probably had metal insertion also, he thought. He dragged the garment from one leg, and then from the other. As he held it in his hands, he rolled over forwards. He dropped it, and pushed against the floor with his hands. In a moment, he was floating in the air. The floor sank away from him slowly.

Instinctively he tried to right himself, to grasp at something. There was nothing he could touch; and for a moment he struggled, beating the air with his arms and legs in foolish panic. Then his good sense came to his aid. He grinned and relaxed. He stretched out luxuriously; a thrilling sensation of restfulness and comfort suffused his whole body. He watched the ceiling coming slowly down to him. Now, this was something like it!

There was none of the bodily discomfort or pain which some of the authors had imagined. Why should there be? The human body is made to withstand gravitational strain from any direction. A man is comfortable standing up, or lying on his back, or on his stomach, or on either side. He suffers no agony standing on his head. When he rolls over in bed, more than a hundred pounds of gravitational pull changes directions in his body; and it doesn't hurt him. Why, then, should the removal of the pull cause discomfort? John Hand found that it didn't, and he was childishly pleased at this vindication of his own judgment.

WHAT did surprise him, however, was the wonderful restfulness he felt. It seemed as though every muscle in his body was crying out in thankfulness at this new release from strain. This must be as good as sleep, he thought. Or better. New strength seemed to flow through his veins. He breathed deeply, and flexed his muscles, with a shiver of pure delight.

He kicked the ceiling, and sailed towards the floor again. He was turning slowly now, over and over. That was a bit annoying, because the room spun around him. He closed his eyes, and felt better immediately. The secret of the thing, he thought, was to be non-resisting. You were helpless, of course; but what did that matter?

Perhaps, though, a man could learn to handle himself pretty well. He resolved to practice that. He made his way to one wall; and then sailed back and forth across the room, diving swiftly.

"Sport of the Gods!" he chuckled. The phrase pleased him and kept running through his mind. He forgot everything else for an hour. Finally, he struggled back into the garment.

From that time on he was a new man. The chief secret of the Adjustors was this. At last, he had something on them. One success breeds others. He began to think about escape.

ON the following morning, however, he got a shock. Happening to wander into the second bedroom, he found a man in the bed. There was something familiar about the big, shaggy head on the pillow. Astounded, he recognized Gordon Wintermaine.

Gordon Wintermaine was unconscious. John Hand knew that there was nothing to do but wait for the effects of the sweetish gas to wear off. He could not help feeling surprised. And yet, what was surprising about it? There was nothing to prevent the Adjustors from continuing their operations as they had warned Wintermaine. They weren't afraid of him. There was no reason why they shouldn't...

Wait!... Yes, there was a reason why they shouldn't!

John Hand smiled in triumph. They had underrated him! Well, let them continue to do so! He would take care not to enlighten them. He would have to be very careful.

Gordon Wintermaine groaned, and stirred on the bed. Slowly, his eyes opened, and took in John Hand. He stared dully for a time. When a man wakes naturally, he is never really surprised at anything he sees. The mind has a way of adjusting itself, slowly and without shock, under those conditions.

"Hello, Hand!" said Gordon Wintermaine.

"Hello, Mr. Wintermaine. How do you feel?"

"Rotten," decided Wintermaine after a moment's consideration. He dragged himself to a sitting position. "What the hell's this?" He fingered the grey garment he wore, disgustedly.

"That's your uniform—as a guest of the Adjustors," Hand-told him lightly.

"Humph!" Wintermaine frowned around the room. Then he looked at John Hand again, with a sudden glint in his eyes. "What are you doing here?"

"Not guilty!" said Hand. The relief he felt at having a companion was showing itself in levity. "I came in place of Van Sweringen. Now that they've got me, they don't seem to want to let me go."

"Oh!" Wintermaine nodded. "I wondered what happened to you."

"How did they get you?" asked Hand.

Wintermaine ran a hand through his hair. "I remember leaving the office last night. My chauffeur drove me up to White Plains as usual... At least, I thought it was my chauffeur. Perhaps it wasn't, though. Just before we reached home I smelled something sweet... The rest is a blank."

After a short silence, John Hand said thoughtfully, "It's strange. I wouldn't have expected it."

"Why?"

"I didn't think they'd ever take you. They've taken a lot of rich men; but—just between you and me—they've never taken a really useful one before... You're not a typical victim."

Wintermaine smiled wryly. "Maybe they don't share your opinion of my usefulness."

Hand spoke awkwardly. "I'm sorry if I put you off your guard—very sorry!"

"Oh, shut up! It's not your fault." Wintermaine swung his feet to the floor. "Do they feed you here? I could eat."

John Hand led him into the living room. The cupboard was open, and contained two bowls now. Hand moved them to a table.

"Pah!" Wintermaine was glaring at the stuff.

"Not so bad as it looks," Hand told him cheerfully. The other agreed with him, after trying the food. But he soon lost interest in eating. He looked around the room curiously.

"Where on earth are we?"

"Nowhere," said John Hand.

"Eh?"

Hand lowered his voice to the faintest of whispers. "We are not on Earth," he said.

Wintermaine groaned at him. "I've got a headache," he objected. "I wish you'd save your jokes till later!"

"I have a lot to tell you, Mr. Wintermaine," breathed John Hand. He glanced around the room significantly. "But we've got to be careful. Wait a while." Then, in his normal voice, he said, "Come. I'll show you around the place."

He did. Wintermaine snorted disgustedly at the drinking and smoking arrangements.

"This is a nut-house. I'm going to pay up, and get out."

"Good," said Hand.

"Maybe I could ransom you too."

"I doubt it."

Later they were in Hand's bedroom, with the door closed. Hand had brought his little ball of wadded paper from the library. He tossed it in the air. Together they watched it. It floated about, finally coming to rest in a corner of the ceiling.

Wintermaine turned a puzzled face to Hand. "What the hell...?"

"I have discovered something," Hand told him. "When I said we were not on Earth, I meant it. There is no gravitational force here. Last night I floated around this room like a bird—or an angel. I took this off." He touched his garment. "There's metal in the weave..."

"You mean—magnets?"

"Electromagnets," John Hand pointed to the polished hardwood floor. "Underneath."

WINTERMAINE looked around the room. "Lord! You'd never guess it... I mean, I never would have," he corrected himself, smiling., "Are you sure? It's a wonderful deception. How about the food, for instance?"

"Their best trick of all. It must have been their hardest problem. They've managed somehow to mix in a metallic substance. A chemical triumph, I'd call it.... They couldn't manage with the water, though—or tobacco... Those tubes are clumsy."

Wintermaine was shaking his head slowly. "It's too much for me. It sounds like science fiction... You say we're off the Earth. Where are we—on the moon?"

John Hand smiled. "Not that far, I hope. Besides, the gravity—"

"Sure. I get you. We're not on the moon... Still, we'd have to be a long ways from the Earth to lose all gravity effect, wouldn't we?"

"Not necessarily. Suppose, for instance, we were revolving around the Earth. That would create a centrifugal force opposing gravity. We might be quite near the Earth."

"How near?"

"Well, that would depend on how fast we were revolving. The nearer we are, the faster we must move."

"Oh, hell!" burst out Gordon Wintermaine. "This is science fiction! I don't like it. You're crazy, and you're trying your best to drive me crazy!... If this place is off the Earth, for instance, how did they bring me here?"

"You came in a sealed cylinder—lifted by an electromagnet and cables, perhaps..."

"... On the end of a rope, I suppose!" In his earnestness Wintermaine was almost sneering.

"Possibly."

"Impossibly!"

"There's no harm in theorizing," said John Hand defensively.

"Sorry!" said Wintermaine quickly. "Go ahead."

"Suppose," said Hand slowly, "that this thing we're in—whatever it is—"

"Call it a ship."

"All right. Suppose that this ship is revolving around the Earth at the same speed the Earth is spinning. Then it could stay right above the same spot on the Earth as long as it wanted to, in a state of natural suspension. Now, if it had propulsion tubes..."

"What do you mean?"

"Tubes that could release expanding gasses... If it had those, it could move about at will; nearer the Earth, or farther from it—or around it, forward or backward."

"Without anybody seeing it?"

"Certainly! It is outside the atmosphere. It is small. It might be painted grey, or black..."

"Power?... Air?.... Water?... Gas for the propulsion tubes?... And what about communication?" interjected the older man.

John Hand drew a long breath. "Well, power would be easy, it seems to me. The ship, being outside the atmosphere, would be boiling hot on the sun-side and freezing on the other. A simple thermocouple would give you all the electric power you wanted. You could have batteries for storing it; so you could go out of the sun any time... As for air and water—you bring them up from the Earth's atmosphere by supply rockets. You could have a radio aerial, too; and talk to people on Earth by short-waves... Also, when you've got water and plenty of electric power, it's no trouble to get explosive gases. Oxygen and hydrogen—by electrolysis."

"Lord!" Wintermaine was visibly impressed. "You've got it worked out, haven't you?... Just the same, it's still fiction. It might make sense from the science angle, but it never would from the business angle. The thing would cost too much."

John Hand nodded unhappily. "Yes," he agreed, "it certainly would!" He wrestled with that problem in silence for a time. Then: "Still, you might look at it this way:—the ship has the whole world at its mercy, so to speak. In time—"

"Rats!" snapped Wintermaine. "No man could ever get his money out of it in his lifetime; and he certainly wouldn't build the thing for the sake of his descendants!"

John Hand had to agree to that.

"But, look here!" went on Gordon Wintermaine briskly. "I'm making a fool of myself arguing with you like this. You've got a theory—and that's more than I've got! I'll tell you what I'll do. When I get back home (or back to Earth, if you like!) I'll pass the tip to every observatory in the world. If the astronomers can't find you, then you're not in the sky; and we'll have to hunt somewhere else! Maybe one of 'em has caught a glimpse of the ship already, without suspecting what it was... Oh, rats!" he finished with a laugh. "It's science fiction!"

They let it go at that.

JOHN HAND had not given up his plan to try to escape from the apartment; but he said nothing about it to the other. That afternoon, they played three very enjoyable games of chess. Gordon Wintermaine spoke to the Quiet Voice on the telephone; blasphemously authorizing payment of a million in gold for his ransom. At dinner.time, unseen by the other, John Hand placed a chessman under the sliding panel of the food cupboard. Saying that he was tired—the truth—he went to bed at eight. For the first time during his captivity he slept. But at two-thirty he was creeping silently out of his room.

His ankle was, by this time, quite serviceable. He listened outside the other bedroom until he heard Wintermaine's heavy regular breathing. He crept into the living room.

The chessman was wedged under the sliding panel. He pushed his fingers into the crack it made, and raised the panel noiselessly. He did not yet know whether he could get his long body into that cupboard, but he meant to try. He succeeded.

The necessary posture was back-breaking. He considered what his next move should be. He had no idea of getting through the adventure unseen. In fact, his first plan had been to secret himself there until breakfast time, and grapple with the waiter when that functionary should appear. He wanted information, and he didn't much care how he got it. That was his attitude.

But now he reconsidered. He couldn't stay bent up like this until morning. Should he go to bed, and come back later? Or should he try to go farther now, unaided by the waiter?

No harm in trying, he thought. He felt around the edge of the inner wall of the cupboard. There was a crack. It must be another panel, he thought. He managed to get his fingernails under it; but it wouldn't move.

He was balked. There was nothing remotely resembling a tool in the four rooms. There wouldn't be, of course. He started to crawl out of the cupboard. Then he had an idea.

This cupboard had two sliding panels, opposite each other. When one was open, the other must be closed. Perhaps the arrangement was automatic... Slowly he lowered the panel through which he had come. When it was nearly to the bottom, he heard a click. Now he tried the other, and it came up easily. He closed the other one all the way.

He was looking into the strangest corridor he had ever seen. It was about twenty feet long. But it was twice as deep. The floor of it was twenty feet below him. In the ceiling, the same distance above, soft lights burned. It was narrow; and its walls were like cliffs, facing each other—cliffs with doorways in them like gulls nests, all up and down the surface.

For a minute he was completely bewildered. Then he saw the reason for it. The inhabitants of this place did not use gravity. The artificial gravity of the prisoners' apartment was not for them. They flew and floated. Staircases were superfluous. Now he saw projections all over the walls which must be handholds.

With a slight grimace, he launched himself into the corridor, floating horizontally. He checked his flight at the first doorway, scratching and grabbing at the wall; and peered through it. The room was a kitchen, he saw instantly. No one was in it. He was glad of that.

He reflected. If he went batting around at random, he was sure to run into someone soon; and then his flight would be rudely checked. What he wanted to do was to get to the outside of this structure.

With this idea in mind, he plunged downwards towards a doorway at the bottom of the corridor on the end. Sailing warily through this aperture, he found himself among machinery. The room was full of it: levers, dials, gauges, and switches. No one was in this room either. He was surprised at that. Didn't they tend their machinery? The whole place had a deserted aspect, for that matter. It was silent as a tomb. If they were going to let him alone like this, thought John Hand, he might discover a great deal.

Then he saw the window. It had a bluish gleam. The blood of mounting excitement throbbed in his temples. He made his way to the window.

"Good God!"

The exclamation was wrung from his lips by what he saw. Before him lay a great, deep sea of beautiful, diaphanous blue! Behind this opalescent curtain he could see dimly shapes which were familiar to him. There was a long, wavering, indented line—light on one side, dark on the other. There were other lines, the courses of which he had known from boyhood... An outline map! The Great Lakes! The Atlantic coastline!

A thrill of mingled triumph and awe shook his very soul. He had been right! Right!... But, oh God, what a difference between the theory and the actuality! The immensity of the spectacle left him weak and sick. He muttered and babbled to himself brokenly... So far away! What was he—so far away from the good Earth? He trembled. With that awesome emptiness between, could he still be a living, breathing man? Or was he dreaming? Or was he dead?

THE absurdity of the last idea helped him to conquer his fit of terror. He came out of it, laughing weakly. He was thinking, now, what a feeble creature he had turned out to be when it came to real scientific adventure. A real science fiction hero would have glanced casually out of that window, taking stock of his position without batting an eye. Probably he would have been quite bored because the Earth was so near. He would have longed for the far reaches of the outer moon of Jupiter—or some place like that, where a man could get a thrill. Above all, he would have been practical in his attitude—not emotional. John Hand resolved firmly to emulate the science fiction hero, even if it killed him. He looked out of the window again.

This time—benefitted by his new attitude—he saw a thing that was of more immediate interest than the Earth—and much closer. It was attached to the ship. It was a huge windlass—or winding drum; and from it there extended towards the Earth a great, shining cable. He followed the cable with his eye—farther and farther into the blue, until it was lost there. The drum was unwound.

Suddenly he was startled by a sound somewhere in the ship behind him. With clumsy haste, he turned himself around and pushed away from the window. He found that he was floating swiftly towards a row of levers. He stretched out an arm to check his flight. His hand slipped on a smooth metal surface, and his whole forearm plunged down among the levers. Immediately, the entire room seemed to lurch sidewise. The opposite wall rushed towards him. and struck him a stunning blow. He grasped blindly with both hands for something to steady him.

"You fool! What have you done?"

The voice was harsh, but it had a familiar ring. He managed to turn himself. Gordon Wintermaine was in the doorway, glaring at him, his face very flushed. John Hand stared at him stupidly for a moment. Then his nostrils flared out...

He snapped: "How did you get down here, Wintermaine?"

Wintermaine's eyes wavered for a split second. Then: "I found the door unlocked. The door in the living room."

"You did not !"John Hand's voice crackled. His face was very pale. Little knots of muscle stood out at the base of his jaw.

Wintermaine came into the room, making for the row of levers. John Hand moved to intercept him, his hands bent like claws.

"Let me alone, you fool!" Wintermaine's voice was a hiss.

Suddenly, the room lurched again—downwards this time. The ceiling came down and struck both men heavily. They heard a harsh squeal of rending metal. Wintermaine screamed, and floated towards the window, mouth wide open, his face now ashy pale. John Hand, at last gaining control over his wallowing body, followed close.

Wintermaine turned from the window, with a mad shout: "It's gone!"

Stunned by the man's vehemence, John Hand gasped dully. Wintermaine went on yelling in breathless staccato:

"You moved the ship!... The cable was cut... The cable caught!... The cable is gone! Damn you—it's gone!"

John Hand understood at last. Now he could see through the window. The drum of the windlass was naked. No cable stretched away from it. The Earth swung crazily around beyond, amid a black, star-studded sky.

Now Gordon Wintermaine was at the levers, jerking them desperately, staring into the faces of dials and gauges. The room leaped wildly around them.

Wintermaine finished with the levers. The room quieted—became motionless. Wintermaine turned, and faced John Hand. The two men stared at each other. Both were deathly pale. They stared into each others' eyes; and the eyes of both glittered strangely. In the little metal room was the silence of death.

Then Wintermaine started speaking. His voice was a lifeless whisper.

"We are alone here, John Hand... All my men have returned to Earth. They returned last night—by the cable... The cable is gone, now... We are alone here, John Hand, you and I... And the circumstances are such that—only one of us can ever return!"

Then John Hand knew that the time had come when he must fight for his life. He was quite calm about it. Carefully, he put both feet against the wall behind him, with his knees bent. Deliberately, he lunged. Wintermaine watched him, and smiled coldly.

Too late, John Hand saw his mistake. He was floating straight at the other, helplessly. He had no way to stop. Wintermaine was gripping the edge of a shelf with his hands. He raised both feet, and bent his knees. John Hand folded his arms over his head, trying to protect it. When he was close enough, Wintermaine kicked out cruelly. The shock sent streaks of fire through John Hand's head, and flung him back across the room. Through a mist of pain he saw Wintermaine passing through the doorway. He heard the resonant clang of the metal door. He fought his way towards the door.

AS he reached it, he heard a rushing hiss in the room; and his tortured lungs inhaled the sweetish smell. He fought and struggled at the door until blackness came.

The blackness roared. It roared loudly, and sparks shot through it. Occasionally a great, fiery-yellow globe would shoot across it, and then he couldn't see the sparks for quite a while. Gradually, they would reappear. Then would come the fiery globe again. So it went, over and over again.

But the roaring was less and less, and the sparks were becoming quieter in their movements. Now they moved in regular files across the blackness, like a parade. They looked like stars, he thought.

The realization came to him that he was conscious, and that his eyes were open. They were stars. The blackness was the sky. The fiery globe shot across, putting out the stars. That was the sun.

He tried to move, but couldn't. He couldn't move any part of his body. He felt as though he were molded in iron. Then he saw that he was looking through glass. He was in a case. He saw the dark metal around the edge of the glass. He was in a metal case, which in turn was encased in glass.

He began to think. The glass was yellow. Otherwise the sun would have blinded him. But why were the sun and the stars wheeling around him with the speed of express trains?

His mind became stronger. He was turning—not they. Now he discovered that he could move his arms and legs a little if he tried hard. When he moved his head, something flashing yellow caught his eyes. This interested him. The next time his head was turned that way, he saw something he had not noticed before. It was a big bulk—cube-shaped. The sunlight glared on it yellowly. It was near to him, and seemed to float in the emptiness.

Now he could stop himself from turning, and control his movements. He was very glad of that. Now he saw the Earth, with its blue sea of air. On the other side of him, the sun shone on a thing which he slowly realized must be the ship.

It was really a ball—a tremendous black ball, with a great winding-drum attached. He stared at it wonderingly for a long time.

Then he turned his attention to the cubicle bulk—a little island in space. It was certainly yellow. It was made of pieces of yellow stuff, in the shape of bars. It was some time before he realized that it was gold.

It was bound around and around with heavy wire.

In his case on one side Hand caught a white glare. Looking closer, he saw two sheets of paper. There were typewritten words upon them.

Resting himself comfortably, he brought the glass of his helmet close to the paper, and read:

My dear Hand,

You have a fair chance of reaching the Earth alive, if you keep your head. I shall tell you what to do.

But first, let me express my regret that our last meeting was so unpleasant. I am an old man, and my temper is very uncertain. The fault was entirely mine. I hope you will accept my apologies, for I have a great favor to ask of you.

You are now dropping slowly towards the Earth. Your rate of fall will accelerate rapidly when you get nearer to it, of course. A parachute is strapped to your back. The rip-cord is attached to the right side of your helmet and also opens the glass coffin in which you are. Pull it when the friction of the Earth's atmosphere begins to heat your case.

You are in the space-suit which we used to make repairs on the outer surface of the ship. We had only one of them.

Floating to earth with you is four tons of gold—approximately. It is all the gold we collected in the form of bullion. The greater part of our ransoms we collected in coins, which are easy to use. They have all been made use of. See where it comes to Earth, if possible. I hope it will not be lost. There is no other way to return it.

Your descent should take about eight hours. You are not revolving with the Earth. You will stay in the sunlight. When you are in the Earth's atmosphere, it will drag you with it; and by the time you land, you will be revolving with the Earth.

I cannot be sure where you will land, but I have tried to make it as safe as possible for you. Your suit will float in water. Proceed directly to Washington, taking the gold with you, if possible. You need not worry about Andrew McQuerdle.

May God go with you! If you die, I shall know it; and the short remainder of my life will be a living Hell.

JOHN HAND paused for a moment in his reading to gaze up at the great, metal ball hanging in space above him. He wondered if Gordon Wintermaine were watching him. Somehow, he could not doubt it. He read on.