RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

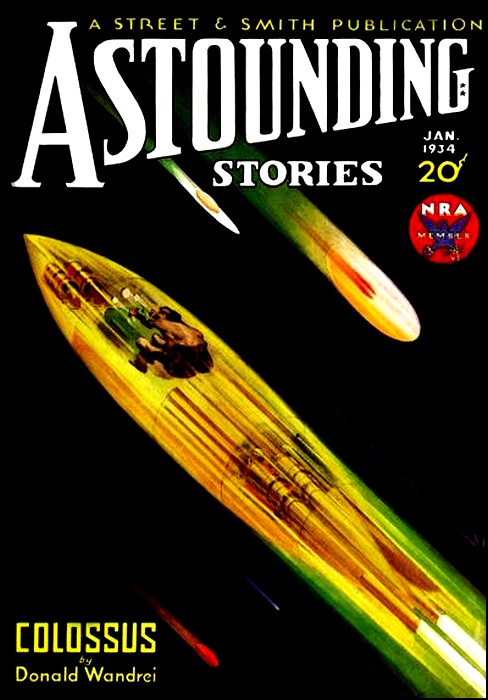

Astounding Stories January 1934, with "Breath Of The Comet"

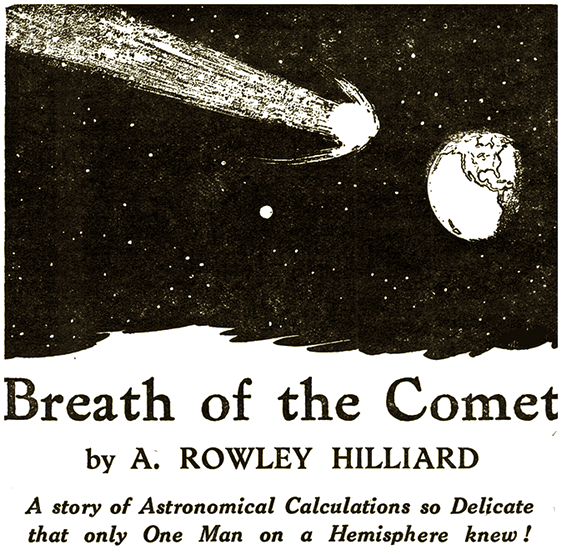

Alec Rowley Hilliard was an American writer who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. He was born on July 7, 1908, and passed away on July 1, 1951, at the age of 42 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Originally from Ithaca, New York, Hilliard was remembered in his obituary as a dedicated professional. He was survived by his wife, Annabel Needham Hilliard, their two children—Elizabeth Janet and Edmund Needham Hilliard—as well as his mother, Esther R. Fiske, and a sister, Elizabeth Hilliard. He was laid to rest at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca.

SURROUNDED BY a gaping, buzzing crowd, stood a man, haggard and worn. With an effort, he spoke.

"My friends," he groaned. "I don't know why I speak to you, because it is too late. I can only pity you, and hope—"

A roar of laughter interrupted him. He waited patiently until it had subsided; then he continued in the same sorrowful voice:

"I can only hope that I was wrong in my calculations—that you shall not perish."

"Nice of him, ain't it?" said a man in the crowd; and the merriment burst out anew, mingled with jeers and hisses.

"Tell us about your contraption again," urged their self-appointed spokesman. "We forgot about it."

"That is not true," the man said wearily, "but I don't mind. What you see here is no more than a large model of the ordinary vacuum bottle. Inside the large tank, which you see, is suspended a smaller tank; and from the space between them the air has been removed. Thus the interior of the inner tank is rendered practically immune to all outside influences. It is within the inner tank that I shall be saved from destruction. There I have a supply of oxygen and food. There I shall remain for a period of two days."

"While we all get burned up, is that it?" put in a woman indignantly.

The crowd grinned expectantly. This was the part of the show it enjoyed most. The man passed his hand over his eyes.

"But, oh, what more could I do? For months I have tried in every way to warn the people of the United States. I have shouted from the street corners; I have advertised in the newspapers; I have spent every cent of the little money I possessed. I am ruined, discredited, the butt of every ignorant numskull who chooses to jeer at me."

His fists clenched, and he raised his head. "I hate you—the whole lot of you."

The slowly-rising murmur of the crowd became a roar as he finished speaking. From all directions they surged forward. The few policemen on hand struggled and shouted orders.

The man turned and flung open a huge, plug-like door in the end of the tank. Then he swung around.

"You would kill me, would you? Well, listen to me: I, and I alone, shall not die!"

He darted into the darkness within; and with a deep clang the heavy door swung to, and remained motionless.

HE was in a place about ten feet long and barely high enough for him to stand erect. Across the bottom of the tank in which he stood, boards had been fitted to make a level footing. A storage battery and small globe on a shelf gave light. In one corner stood a small dry-ice chest; in another, an apparatus of tubes and valves which was the air-revitalizing machine. Across one side lay a mattress with neatly folded bedclothes. It was upon this mattress that Professor Ludvig Hertz threw himself.

Slowly he regained his composure. He couldn't really blame them. Why should they believe what he, a great deal of the time, could not believe himself?

His mind traveled back to the time, less than a year ago, when the awful truth—or was it truth?—had come to him. Well, truth or not, it had ruined him. Then he had been a widely respected professor of astronomy in a great American university; now he was an object of pity and derision to the country which he had made his own—to most of the world, for that matter.

Yes, the world had reflected—although with less sympathy—the attitude of Dean Mitchell of the science department whose conversation with him remained graven in his memory; and would, he knew, until his dying day.

It had been almost midnight, that night, when he had burst into Dean Mitchell's study, disheveled, trembling, horrified.

"Why, Professor Hertz, what in the world is the matter?" Mitchell had asked in surprise.

"Oh, God, it is awful! My comet is about to—although I may be wrong; but I have checked my figures over and over, and I am sure I have made no mistake!"

"What is your comet about to do?" asked Mitchell with a twinkle in his eye. In scientific circles, the Hertz comet was sometimes taken seriously, sometimes not. There were those who claimed it to be no comet at all; in fact, nothing at all. And there were those who, admitting it to be a comet, still were in serious disagreement with its discoverer regarding its composition, orbit, and characteristics in general. In fact, nobody agreed with Professor Hertz on every point, and there were those who did not agree with him on any.

"The Hertz comet," he almost shouted, "is about to destroy the Western Hemisphere!"

"What!"

"The nucleus will pass through our atmosphere on May 23rd, less than one year from to-day—less than a hundred miles from the Earth's surface!"

Mitchell, who had started up in astonishment, was now leaning back in his chair with a worried frown upon his face. For a few minutes he sat in silence, tapping his teeth gently with a pencil.

"Hertz," he said at last, "the semester is almost at an end. I am sure that it could be arranged so that you could start your vacation now. We have been working you pretty hard this year," he continued, with a sympathetic smile.

"Vacation? Working hard?" Hertz began in a dazed fashion. Then he understood, and went on indignantly: "You think I'm crazy! Good Lord, I almost wish I were. I wish I were!"

"Now look here, Hertz, you know as well as I do that for the last hundred years scientists have been agreed that no harm can come to the Earth from a comet."

Hertz leaned forward earnestly. "Dean Mitchell, you, a scientist yourself, know how dangerous it is to veto any specific proposition with a generalization such as that. They say that meteorites cannot harm the earth; yet if the great meteorite of 1908 had fallen in Berlin or London or New York City, instead of in the wastes of Siberia, the destruction would have been awful, and its victims would have been numbered in the millions."

"But meteorites are not comets," objected the other.

Hertz shook his head impatiently. "Of course meteorites are not comets. I was merely showing you that we cannot protect ourselves from cosmic destruction with vague, unstudied generalizations."

"You know, yourself," said Mitchell patiently, "that we are not trying to do that. Why, the very nature of comets renders them harmless to us. Their tenuosity—that is, their lack of density—makes it impossible for them to affect so dense a mass as the Earth, even though they may be many times larger. You know as well as I do that the Earth passed directly through the tail of the great comet of 1861, on June 30th of that year, without anything unusual happening. Therefore, why should——"

"Through the tail—yes, the tail!" groaned Hertz. "What is the tail? It is nothing; it is no more than a stream of light, or excitation of the ether. The Earth was two million miles from the nucleus—the great, roaring heart of the comet."

He paused a moment to collect himself, and then said: "My calculations show, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that the circular orbit of the Earth and the elliptical orbit of the Hertz comet coincide at a point in space, and that both the comet and the earth will reach that point together on May 23rd, 1935!"

MITCHELL remained a while in silence. He seemed reluctant to speak. At last he said: "I do not want to hurt your feelings, professor; but of course, you know that considerable doubt has been expressed in astronomical circles as to whether an orbit can be assigned to the so-called Hertz comet. To do so it is necessary that the comet be seen twice, and there is no definite proof—"

"Dean Mitchell," interrupted the other, "sixty years ago, in Germany, my father discovered a comet. He studied it closely throughout the months during which it was visible, because it displayed certain unique features."

He paused for a moment and then continued: "You are of course familiar with the fact that the stars are visible even through the nuclei of ordinary comets. What startled my father was the fact that the nucleus of his comet, when passing in front of a star—even one of the second magnitude—completely obscured it from view. He was forced to the conclusion that it was of a greater density than any ever before seen. This conclusion was supported by spectroscopic analysis of the comet's rays. The course of the comet was also peculiar, and could be explained by no known influence—"

"There's the point," interrupted Mitchell. "It was obviously one of those stray comets which is no part of our solar system—which appears and disappears, never to be seen again."

"My father did not think so. He believed it to be a 'captured comet'—one that has come under the influence of some planet in our solar system. What that planet was, he could not say; he merely postulated its existence. On that basis he was able to predict that the comet would again appear in thirty years' time."

He paused; but Mitchell, who had decided to hear him out, remained silent.

"Never will I forget the day when the comet reappeared. I was scarcely twenty years of age. My father was elated—almost mad with joy. And then came the terrible surprise and shock of learning that the scientific world—almost to a man—was arrayed against him. They ridiculed the idea of a comet whose actions they could not understand. They had not the imagination to see that there could be another planet in the solar system which they had never seen. Their unbelief broke my father's heart. He died within a year."

The man was silent.

Real sympathy showed in Mitchell's face, as he replied: "That was tragic; and I am very sorry. I hope you will not think me crude when I repeat what has been so often said, that there was no reason to believe it to be the same comet. It is true that there were some points of resemblance between the two appearances, but by no possible stretch of the imagination could the same comet have appeared at that time. Such an orbit was impossible without inventing a new planet to explain it; and we cannot do that, you know. It would have been discovered by now."

"It has been discovered," said Hertz quietly.

"Has been discovered?" repeated the other in astonishment.

"It is the planet Pluto."

Mitchell looked at him in stunned silence. Yes, certainly Hertz had been one of those who had predicted the discovery of the new planet—a discovery scarcely four years old, now.

"But if Pluto explains the orbit of the Hertz comet, why have you not proclaimed the fact before now?" he asked.

"I have been reconstructing my theory—or, rather, my father's theory—in the light of the now definite location of the planet. I wanted to make it so convincing that there could be no more disbelief. I have plotted the comet's orbit with absolute certainty.

"Not until the day before yesterday did I realize the awful consequences. I have not slept since," he said simply; and his white, haggard face testified to the fact.

Mitchell laughed uneasily. "It is impossible," he declared; and drew out his watch. "Hadn't we better be in bed?"

Hertz disregarded this. "Why is it impossible? Did not the comet of Biela intersect the Earth's orbit on October 29th, 1832? And was not the earth only thirty-two days' journey from the spot?"

"Yes, thirty-two days or about fifty million miles!" countered the other. "Has not somebody calculated that the chances against any such collision are two hundred and eighty million to one?"

Hertz shrugged impatiently. "That is Arago's wild and senseless guess. Suppose for a minute that he is accurate—that in any particular year the chances are just that. Has not our globe been revolving about the Sun and have not comets been shooting through space for twice two hundred and eighty million years and more? What, then, does Arago's calculation mean? It means that in any particular year the chances for the event are even, or better!"

UNBELIEF and perplexity showed on Mitchell's face, but now he was deadly serious. "You said that the comet would destroy the Western Hemisphere. What did you mean by that?"

"Perhaps I should have said the northwestern. I cannot tell how far south the effect of the comet's passage will be deadly. But, as surely as I am sitting here, every living thing in the whole of the United States and Canada will be withered and blasted—utterly annihilated!"

"Through what agency?"

"Heat, man, heat!" shouted Hertz. "Don't you see it? The terrific friction between the nucleus of the comet and the atmosphere of the Earth—both traveling at more than sixty thousand miles an hour—would alone do the damage. But there will be more than that. All the combustible matter of the comet—and hydrogen is surely there in great quantities—will burst into awful, scorching flames!"

"True, very true," murmured Mitchell, "if we admit the passage of the comet. But I don't admit that. How, for instance, can you be sure that it will pass over the Western Hemisphere? How can you know positively?"

"That is one of the simplest parts of the calculation. The comet will graze the earth on the side toward the Sun when it is daytime in the United States—somewhere between noon and three p. m., to be exact."

"But if it comes as close as you say, why will not the attraction of the Earth's mass cause it actually to collide with us?"

"For the same reason that any comet does not fall into the Sun—because of its tremendous velocity."

"But the attraction of the earth must change its course somewhat."

"Of course it does. Were it not for that, the comet would pass us at a distance of one hundred thousand miles. It is this attraction which I failed to reckon on until just recently. Otherwise I should have known sooner."

Mitchell sat silent. The exact and unfaltering answers of the other had seriously shaken his faith; but his mind refused to embrace Hertz's immense and terrible proposition. Instead, he was searching desperately for flaws in the argument. Suddenly he returned to the attack.

"But what of the coma—the enormous envelope of gases at the head of the comet. If the nucleus itself came so near, would not the coma smother the whole earth?"

"I do not think so," replied Hertz slowly, after a pause. "The inhabitants of the rest of the earth should thank God that this comet is one of those—of which there are many, you know—that appear to have no comas. There will be gas, of course; but I do not think that its effects will be far-reaching. There will be tremendous winds and tides all over the Earth, but I think that the Eastern Hemisphere will survive—at least in part."

For perhaps a quarter of an hour, the two men sat in silence; Mitchell frowning and drawing aimless designs on his blotting pad before him, Hertz leaning over, running his hands through his hair. The excitable German was in a state of mental agony bordering on distraction; the practical American was considering probabilities, possibilities, causes, and effects. The trend of his thought was revealed in his next question:

"Will it be possible to check your calculations?"

The other replied without looking up. "Dean Mitchell, the Hertz comet has been my life study, as it was my father's before me. Do you for a moment imagine that any adequate check can be made in the bare seven months which remain before the catastrophe?"

"Of course not," said Mitchell quickly. Even as he had asked the question, he had realized its futility. Now he spoke with quiet emphasis:

"Inadequate checks will be made, however; and they will all contradict you."

Hertz looked up at him in wide-eyed astonishment. "Why should they contradict me?"

Mitchell raised both his hands in a gesture of irritation. "Good God, man! What do you expect will happen? Do you think that, on your word alone, the two hundred million inhabitants of the United States, Canada, and Mexico are going to pack up—bag and baggage—and migrate bodily to Europe, or wherever they can squeeze in?"

Hertz sank back in his chair, his face a mask of horror. "It means death to millions!" he whispered.

AND now, as he lay upon his back in his strange iron prison—a pitiful wreck of the man he once had been—Hertz knew that Mitchell had been right. He had been subjected to the concentrated ridicule of a nation—the vicious ridicule that is born of fear.

For Professor Ludvig Hertz was, without question, a pitiful wreck, who mumbled incessantly to himself, whose hands shook weakly as he reached forward now to adjust a valve on his air machine.

He looked at his watch. Almost noon. He felt very weak. He had better eat something. Had to keep up his strength. Seating himself before the ice chest, using the top of it for a table, he partook of a very simple repast. Very simple and very short, for he quickly discovered that he was not hungry. Food did not appease that strange, powerful longing he felt.

Ludvig Hertz was lonely—lonely not so much for the companionship as for the sympathy of men. They had all been against him, would not listen to him, had merely laughed at him.

With the sound of that laughter ringing in his ears, he flushed and muttered angrily. Laugh, would they? They only did it because they were afraid and could not help themselves. Mitchell had foretold it. But fear didn't justify cruelty.

Laugh, would they? Well, he would laugh last—and alone! For he was right, and they were wrong; and to be right meant to live, and to be wrong meant to die, and so it always had been. They that had jeered would die by the millions, struggling, gasping.

Something that was strong within Ludvig Hertz rose up to strangle thought, and he buried his face in his hands. He had been wishing it! Was he mad?

Mad! People had said so. Pallid and shaking, he rose to his feet, swayed dizzily for a moment, then crumpled down upon the bed. Why had he stayed in this awful place if he was sane? Why had he not gone to Europe with those few wise ones who had gone? He had told himself that scientific interest made him stay, but he could not deny that a strange and horrible fascination held him there.

Yes, they had said he was mad. Once they had detained and examined him. At the memory, anger drove out fear.

They had called him insane when he tried to save them. And as if that were not enough, they had denounced him from their pulpits as an enemy of God and man.

God! What of Him? Would God let them die? They were not bad people—could not be, so many of them. God was justice.

His head swam. To be good was to be right, was it not? Then they were right, and he was wrong. They were so many against one, and he an enemy of God.

And in his sick loneliness he wept bitterly.

Wrong! How easy it would be! Just one little slip! Many great scientists had said he was mistaken. They would not say so without reason. True, they could not check his calculations; but they knew things that he would never know, for they were greater than he.

What a fool he had been with his comet! A little shouting fool! And he would have to go out and face them—face a hilarious crowd that would surely be there, ready for the show. His whole soul was filled with dread of that cruel comedy to come—which must surely come, for he could not remain hidden forever. If they would beat him, kill him, he would thank them; but they would not.

They would laugh! That hateful laughter that thundered in his ears—that drove him mad!

Oh, if they would only die, those cruel, laughing millions! And as he feasted on that dream, his eyes shone, and he smiled.

He tossed upon his cot, his eyes gleaming strangely in the pasty whiteness of his face, his hands weakly clenching and unclenching at his sides. His mind was no longer clear. It was a tortuous, whirling tumult in which one single element of consciousness, one lone idea, fitfully flared.

That they should die in torture—the laugh burned from their lips! Then he would laugh.

And so Ludvig Hertz passed into unconsciousness—more of delirium than of sleep.

THE strange iron refuge of Professor Ludvig Hertz had been placed on the top of a rather large knoll to protect it from the tides, and had been firmly anchored by many cables to hold it against the winds. The iron surface had been heavily coated with asbestos to preserve it against the heat. From its elevated position the ground sloped away in all directions, and it was possible to see for many miles.

To the east, far off, lay the sea; in the south, faintly visible, rose the tall spires and towers of New York City; at the west and north there stretched away the farm country, slightly rolling, sparsely wooded.

The plug-like door of the refuge was a hollow shell of iron—vacuum inside—which fitted closely into a circular passageway fused between the outer and inner tanks. It was fastened strongly on the inside with clamps.

EXACTLY forty-eight hours after it had closed, smoothly and slowly this door swung open; and far over the scorched and blackened earth there rang a laugh, wild, triumphant.

Far through the acrid barren air it rang, but no one heard it; for in this desolate waste nothing could hear or see or feel. And when it ceased, it left a deathly silence on the black earth under the red sky.

And Ludvig Hertz, breathing quickly, for the air was strangely unsatisfying and thin, surveyed a ruined world with joy.

He stooped to examine the earth. Yes; it was burned to a hard crust, as he had expected. And that hard crust stretched as far as he could see, over all the hills, making them smooth and black and beautiful.

But in many of the valleys lay water, weirdly reflecting the ruddy glow from above; and this, at first, he could not understand. Water! Slowly he turned east toward the sea.

Of course! The sea had done it—the tides. Had he not said so? There it lay, in the distance, red as blood. Above his head the sun shone crimson through an atmosphere laden with the dust and ashes of the conflagration.

The man sighed ecstatically. He loved this beautiful world of red and black, where no one laughed but him. It was so smooth, except for here and there a pitiful stubble where woods had been, except for a few black lumps on the surface of the hill around him. Those lumps—what were they? Queer twisted things.

A shriek rent the heavy silence and ended in a mad babble of sound, as Hertz laughed again. They were men!

Animated by a horrible curiosity, he stumbled down the hill among them, muttering and chuckling to himself. No feeling of pity could now find place in his warped and broken mind. In its stead was a simple, gloating pleasure. They that had come to laugh at him and could not; but he could laugh at them, for he had been right. Right beyond the shadow of a doubt; right in every particular; right against the whole world. He was great! They would pay him tribute now! Yes—now they would realize!

They would pay him tribute—who? They were dead—burned to little black lumps. They that had called him fool did not know that he was great. They that had tortured him with laughter could not now hear his.

In a mad and futile anger he ran panting down the hill and out across the open country, searching for something that could hear him or speak to him. But in that infinite solitude nothing moved, and there, was no sound.

The hot, sharp air was not good to breathe; he tired quickly, and sank down on the black earth, more lonely than he had ever been before. Was he, then, to die like this—alone? No; surely some one would come, surely they would come from the other side of the world to find him. They knew he was there. Mitchell knew, and Mitchell had gone to Europe with the wise ones. He would come, even if—

But—but—

A terrifying thought: suppose they could not come! Perhaps they were helpless. Perhaps they, too, were dead. He tried to put the thought out of his mind, but it returned again and again with ever-increasing force until it assumed the proportions of truth. What madness to dream that the comet which wrought this destruction had not killed every living thing on earth! All except him. He alone lived; and soon he, too, would die, and no one would ever know how great he was.

In futile, childish rage, he beat the hard earth's crust with his fists and sobbed aloud.

ACCOMPANIED by a low, faint hum, a speck appeared in the east. Slowly it grew, and the hum became a roar, as a great airship, its sides gleaming redly in the light of the sky, sank lower and lower toward the earth. Almost before it touched, men leaped out upon the ground.

"He should be somewhere not far from here," said Mitchell, "if he is alive."

"Which he isn't!" returned the captain shortly. "Why, great God, look at the place! It's—it's ghastly."

"Still, there is a small chance," persisted Mitchell. "He had prepared a place—"

"Look there!" exclaimed the captain suddenly, stretching out his arm.

Far out across the black surface, a man was running toward them, frantically waving his arms above his head. Faintly, they heard his shouts.

"Thank God!" cried Mitchell, and started to run quickly over the scorched, black crust.

"He sure is glad to see us," said the captain at his side, "and I don't blame him!"

Others from the ship were following them, and by the time they reached Hertz they were a sizable crowd. He was gasping for breath and could only stare at them, an eager gleam in his eyes.

"Thank God you are alive!" cried Mitchell, grasping both his hands. "The world has suffered enough without losing you. I cannot begin too soon to praise you, as the rest of the world is praising you and your great mind. We are all—"

"I am great!" The man's voice was a hoarse croak. He wrenched his hands from Mitchell's and shook his fists above his head. "I am great, and the fools who laughed at me are dead. They are little black lumps all around us. They are little black lumps because they laughed at me. Now you shall hear me laugh at them!"

He threw back his head, and the air rang with peal upon peal of wild, demoniac laughter.

"Good God!" muttered the captain, and stopped.

Mitchell was speaking to him in a quick undertone. "We must get him away from here immediately," he said. "We shall have to start back without delay. Have some of your men carry him to the ship."

"Suits me!" the captain muttered. "I've seen more than I want to see here already."

Four men grasped Hertz who, in his weakness, could offer little resistance; and the whole party moved quickly toward the ship.

"When he is out of this awful place and among friends, he will be all right," said Mitchell.

"Let's hope so," said the captain, a bit dubiously.

They lifted him through the door of a cabin, and laid him on a daybed there. He did not appear to understand what was happening, but babbled ceaselessly to himself.

Within a quarter of an hour, the ship left the ground, and was rising swiftly—a thousand feet—two thousand—

Mitchell and the captain stood at a window, gazing with ever-increasing wonder at the strange, desolate world they were leaving. A sudden cry made them turn. The man had leaped to his feet and was staring wildly about him.

"What are you doing?" he shouted. "Where are you taking me?" He stumbled to the door.

"You are taking me away from them—so I can't laugh at them!" he screamed. "You shall not. I laugh at you and them!"

"Quick!" yelled Mitchell; but the captain was too late, and together they gazed horrified into the black depths below, where a whirling thing of arms and legs dwindled to a speck and disappeared.

Away into the east sailed a great airship, leaving behind it a world where nothing lived.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.