RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

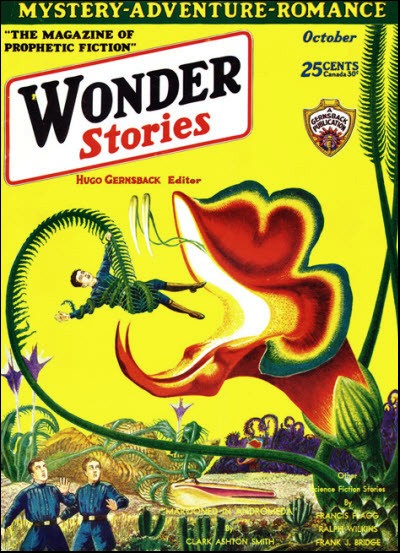

Wonder Stories, October 1931, with "Death From The Stars"

Alec Rowley Hilliard was an American writer who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. He was born on July 7, 1908, and passed away on July 1, 1951, at the age of 42 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Originally from Ithaca, New York, Hilliard was remembered in his obituary as a dedicated professional. He was survived by his wife, Annabel Needham Hilliard, their two children—Elizabeth Janet and Edmund Needham Hilliard—as well as his mother, Esther R. Fiske, and a sister, Elizabeth Hilliard. He was laid to rest at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca.

IN this gripping story, we get a peek into a few of the most profound mysteries of the universe. Many modern scientists say that life is a disease that attacks matter in its old age—that when matter cools and loses its primal energy only then is life possible. Life being a disease, all forms of life feed on each other—we are all in a sense bacteria consuming each other in a fierce struggle for existence.

There are many hundreds of forms of life that we know of, and whose properties we dimly sense. But how about the infinity of possible forms of whose properties we know nothing? Suppose we were exposed to such a thing? Would there be a gigantic struggle for existence, the human race battling against a terrible unknown enemy?

Mr. Hilliard has given us here, no world-shaking epic, but a grim, intense struggle against a devastating ravage. The precise nature of the enemy is not made clear, nor would it be clear to us were we to meet it. But we can sense in it the infinite forces of the universe massed against puny man. This story marks a new notch of achievement for Mr. Hilliard as a writer of stories about possible things.

GEORGE DIXON was struggling wildly amidst a great conflagration. Fire burned his body; blazed before his eyes, roared in his ears. For hours and hours he struggled, wondering why he was consumed....

And then he awakened, to the recognition of his own bedroom and the fact that he had been dreaming. But that burning feeling of his body did not cease. Neither did the bright flashes of light before his eyes, the roaring in his ears; and these phenomena were ten times stronger now than in a dream. His limbs twitched convulsively under the bed-clothes.

Must be sick, he thought. Nerves a bit frazzled lately. Overwork, perhaps; but he hated to admit that. Couldn't give up work now. No, not now. He rolled over, and groaned. Rotten feeling! Feel better in the morning, most likely. Had to. Had to watch his little block. He was worried about it. It had been getting smaller right along, and sort of crumbling. Yes, instead of growing it was shrinking away; and he couldn't understand that—couldn't see where it disappeared....

For an hour he tossed uneasily on the bed. Although his bodily discomfort was steadily growing, it was not that which occupied his mind. He was worrying about his little block, down in the laboratory. If he could make sure it was all right, he might get some sleep. He threw back the covers, swung his feet to the floor, and stood up. Uttering a low, startled cry he swayed dizzily, and leaned against the wall for support.

"Something pretty darned wrong!" he said aloud. His voice sounded strange and high-pitched, in his own ears. He found the light switch.

The journey down the stairs was long and terrible. He held fast to the banisters, taking one step at a time. Ordinary muscular coordination seemed to have deserted him. Each movement required an effort of will. He could not last long. Having gained the foot of the stairs, he staggered to the laboratory door on the right; burst in, and switched on the light. There was a long moment of complete silence. Then he gave a hoarse cry.

The laboratory was a large, square room, with long windows on two sides. Against the walls were set lead-topped tables, littered with tubes, retorts, and various electrical devices. But it was towards the center of the room that George Dixon stared, wide-eyed. There, on a small table, under a bell-jar, reposed a little heap of black dust. Nothing more. There was certainly nothing in the exhibit to astonish or terrify an ordinary observer.

Yet George Dixon was both astonished and terrified. For he knew that, only yesterday, there had been, under that jar, a pretty fair-sized block, composed of his "life force". And now it was gone. Where?

Things had to go somewhere, he told himself. The jar was sealed tightly to the glass plate beneath. Yet there remained only black dust—and George knew what that was.

He laid his hand on the glass. Warm, but not hot. His eyes wandered around the room—then became fixed upon a grotesque object on the window ledge. It was—or, rather, had been—his geranium plant; but now the leaves were a dead black. As he watched, one of them dropped off, and crumbled to powder on the floor.

George drew his hand across his eyes. Something was happening—something he could not understand. He must try to think. But it was hard to think. His mind didn't seem to work right—kept wandering. He wished Julius were there. Julius would help him.

HE stared at the geranium plant. Even the stalk was black. It was crumbling away—as his little block had crumbled. But that didn't make it any easier. No, he couldn't think. If only Julius....

He remembered the things Julius had said when they had last talked together. Julius had come to visit him—an unusual occurrence—saying that he was interested in a proposed experiment George had mentioned in a letter. George had explained cautiously his intention to explore for life in substances deposited on the earth from outside.

"What is life?" Julius had asked abruptly. George remembered laughing. Julius had a way of asking unanswerable questions. George had muttered something about Assimilation.

"Life is a disease,"—Julius had a way of asking unanswerable questions—and then answering them.

"Disease!" George had exclaimed.

"Exactly. A disease or corruption which afflicts the stagnant matter which is our earth. This planet's matter is very low in energy. It is cooling—disintegrating. And you and I are the crawling, writhing maggots of its decay."

"Horrible and preposterous!"

"Horrible, perhaps—but not preposterous. We say that life cannot exist upon the sun. Why? Because the sun is too hot for it. What does that mean? Merely that the sun has the protective energy to purge or sterilize itself of such 'life' as we represent. Place a needle point in a flame—as the doctor uses daily; there you have the same sort of sterilization on a small scale."

George had been slightly indignant. "You put a disagreeable interpretation on a small number of facts. That may amuse you, Julius; but I fail to see how such speculations can have any practical value..."

"They might serve as a warning to such as you."

"Warning?"

"Yes. If I understand your motives correctly, you want to explore for life in meteoric substances. Since they consist of matter in a very low state of energy—and because mere cold is not always fatal to life, even as we know it, I fully believe that you will find what you are looking for."

"That is gratifying. It makes you practically unique among scientists!"

Julius had not appeared amused. "But I am far from believing that you are wise in attempting it. When you find it—what then?"

"What then?—I don't understand you."

"Well—do you expect it to be identical with some form of life we experience on earth?"

"Not necessarily."

"Probably?"

"No. I should say that the probability points in the other direction. Life is a product of its environment; and it would be a remarkable coincidence if this supposed new life had developed under conditions identical with those on earth.

"It is my theory that some such 'life' may exist in meteoric substances, in a state of suspended animation—induced perhaps by lack of heat and most certainly by lack of food; To put it briefly, I intend to test for its presence with a variety of temperatures and a variety of foods—"

George remembered that Julius had nodded absently. There had been a strange look in his heavy eyes as he asked quietly:

"And are you not afraid?"

George shuddered, now, as he lay back in his chair. He felt dizzy and sick. His body was numb, with that helpless, prickly numbness one sometimes feels locally when his foot is "asleep". Yes, he was afraid now—but then he had merely said: "Afraid?—afraid of what?"

"Good Lord, man, don't you see it? You have just admitted that you expect this new life to be different from anything on earth...."

"But I don't see why a mere difference—"

"Wait! Let us go a little more deeply into this life-as-a-disease idea. Not only is life as a whole a disease of matter, but each species of life is a disease to every other. The tubercular bacillus on the wall of your lung has no more personal animosity towards you than you had towards the duck you ate for dinner. It is merely living off its environment, as you are. Obviously, mankind is as truly a disease of ducks as tuberculosis is of mankind....

"I SEE what you are driving at. You mean that any new life I might discover would automatically be hostile to many or all terrestrial species. Yet I see nothing terrifying in that. Man has certainly dealt with any number of hostile species during his existence, and has—"

"Man has dealt with nothing!" Julius cut in angrily. "Man has been dealt with. You talk as if he had arrived at his present form by an act of will, and fine determination. That is contrary to the first principles of evolutionary science. Man is a form of life that has been shaped by its enemies. Yet even after millions of years of adaptation, he is not immune to attack—attack by species which are a part of the very environment in which he has developed.... And you propose to introduce something new. Good God!"

When angry, Julius was somewhat overbearing. George had asked meekly, "Well then, would you advise me to give up the idea?"

"No, no, no! Am I your master? Do I do your thinking for you? Damn it, man—make up your own mind! I want to be sure you know what you're about—that's all...."

There had never been any doubt in George's mind about what he was going to do. He made that clear.

"All right! Do you have your meteorite?"

"No. It is astonishingly difficult to get hold of one. So far I have had no luck at all."

Julius drew a folded newspaper from his pocket; and held it out, indicating with his finger a paragraph:—

STRANGE THEFT IN MUSEUM

An unidentified man visited the American Museum of Natural History late yesterday afternoon, and departed with one small meteorite, the property of that establishment. He was seen by a guard, rapidly leaving the building, after having stood for some time over a case containing a number of similar exhibits. Dr. Hardman, Curator, when questioned, could suggest no motive for such a theft.

George looked up curiously from the paper. Julius was leaning back, negligently tossing from one hand to the other a small black stone. "Catch!" he said.

Clumsily George caught it. "Why, you can't—I can't—It isn't right!" he stammered.

"That is my affair!" snapped Julius. "The moral stigma attached to you by the transaction—that of receiving stolen goods, I suppose—is very small and very theoretical."

"But—"

"But, nothing! That little thing is going to be put to a real use, instead of being eternally gaped at by a succession of idiots who don't give a damn what it is or where it came from.... Now I'm going."

"But wait a minute, Julius! What do you really think about this experiment? What is your honest opinion?"

"I think it a very promising line of enquiry and a very laudable task. Praiseworthy, but uncertain.

"What is this 'life' you hope to find? How will you perceive it? Have you stopped to think that there may be life that we cannot observe through the senses developed on Earth—that does not obey the rules we have set up?

"I suppose you will use assimilation as a yardstick—a criterion by which to judge. You will look for something that increases itself at the expense of other things. A ticklish job, at the best; because that something may be intangible, immeasurable, and altogether strange to you. In other words, you are looking for a new disease—one that you will not understand when you find it... What will it attack? What will it feed on?... Who knows?"

Julius had gone, then. An unsociable man, his visits were very rare and very short.

George wished Julius were there now. He needed someone else to think for him. The little block—the food—was gone. Was there something there—something that increased itself at the expense of other things? Had he succeeded? Was there life?... The food was gone. But where was the "something that increased itself?"

Under the glass—it must be. Everything had been sealed tight....

IN the pot on the window-ledge was only a stalk. All the rest was black dust. He stared at it dully.... Suddenly a glimpse of something on the arm of his chair made him start violently. It moved towards him—a dead gray thing, splotched with black. He stared at it unbelievingly...

It was his hand!

George Dixon struggled to his feet; and stood trembling, in a wild panic. What was happening? He stared at his hands.... Diseased! The word brought a new terror. Julius's words rang in his brain:—"Life is a disease.... Something that increases itself at the expense of other things!" He stared pleadingly at the glass jar. It was under the glass. It couldn't get out....

"—Life that we cannot observe through the senses developed on Earth—that does not obey the rules we have set up...."—Some voice was repeating the words in his brain—"—That does not obey the rules..."

A horrible possibility flashed into his mind; and, with a sob, he blundered out of the room, desperately slamming the door. He needed help—he needed Julius. The telephone....

JULIUS HUMBOLDT was cursing softly as he grasped the receiver, but when he laid it down his expression was very serious. The confused babble on the wire would have been meaningless to anyone else, but it galvanized him into action. Hurriedly, he set about dressing; moving quickly about the tiny room.

Five minutes later, a shabby figure, he tiptoed down a very shabby staircase; and emerged on Tenth Avenue. Turning east, he half walked, half ran along Forty-ninth Street towards Broadway.

JULIUS HUMBOLDT was shabby because he was poor, and because he did not care anyway. He was taciturn—perhaps a misanthrope, although more inclined to disregard his fellow men than to hate them.

He had once been a professor of chemistry at Columbia University, but constant clashes with the authorities—having mainly to do with his "radical and unfounded theories"—had necessitated his resignation. He now lived precariously on a small annuity—seldom doing any work of a type calculated to increase his meagre resources. He had few acquaintances and only one friend—young George Dixon.

At Broadway, he plunged down the steps into the subway; and boarded a downtown train. Arriving at the Pennsylvania Station, he learned that the next Port Washington train left at four. Muttering to himself he studied a time-table. Great Neck—four-forty... He paced up and down the platform....

"The block is gone—gone! It's got me...."—and then something about a geranium. George had certainly sounded strange—wild... There must be something really wrong.

The block—he knew what the block was. George had written him a letter, outlining his method of procedure. He had broken up the meteorite—pounded and pulverized it into a fine powder. This powder he had mixed with a combination of foodstuffs—animal and vegetable. The whole combination he had then compressed, under great pressure, into a small, square block—which he had subjected to various temperatures and various frequencies of ultra-violet rays.

A simple, almost childlike performance, Julius reflected. Yet direct and reasonable—characteristic of George. If this gave no results, he would try some other way. But, wait...

George had said the block was gone. Gone? Julius stood still, biting his lips. Stolen?—Ridiculous! The thing had no value....

The gates clattered open; and, absentmindedly, he boarded the train. Expensive, these Long Island trains, he thought ruefully. For fellows like George who didn't have to worry about money, it didn't matter.

"—It's got me...."—What could he have meant by that? His hands thrust deep in his coat pockets, his chin on his chest, Julius Humboldt pondered the matter, as the train rumbled under the East River and out into Long Island.

AS the journey advanced, he began to feel more agitated. Several times he shook his head violently; and once gave a startled exclamation, causing the few other passengers in the car to turn amused eyes in his direction. Many frowned slightly at sight of the gaunt, forbidding figure with the face that was, by now, very, very grim.

The Great Neck station was deserted, and he set out at a quick pace to cover the half mile to George Dixon's house. The sky was overcast, and no signs of dawn were yet visible. The damp air enveloped him like a black mist, depressing his spirits and seeming to increase the sense of heavy foreboding which he suffered. The large house, set back among trees, was an ominous jet shadow, as he approached it up a winding path. Obsessed with a strange uneasiness, he walked on tiptoe, straining his eyes and ears.

In another instant he was frozen into immobility by a laugh—a sudden, high-pitched, gurgling laugh, it rose and fell and ended in a sob.

He gazed fixedly at the house. That was not George. Who—what—was there? Slowly he advanced, mounted the steps, and laid his hand on the doorknob. From inside the house there came a shrill cry, a crash—then silence.

The door was unlocked. For a long time be stood very still, his head thrust forward. Then he slipped quietly into the black interior. He remembered vaguely the plan of the place. To the left was the laboratory; to the right a sitting room; and straight ahead the stairway, flanked by a narrow hall leading to the back of the house. He moved to the left, and felt along the wall to the laboratory door? A faint line of light showed beneath it. He knocked, and waited but there was no sound. Cautiously, he pushed open the door.

The room was untenanted. Light came from a large globe in the ceiling. He advanced across the floor, his eyes darting to right and left. He paused over the table in the center, and gazed thoughtfully down at the small heap of metallic dust under the jar.

"Pretty well cleaned out," he muttered. "It's gone, all right!" Again he glanced around. This time his eye was caught by the unusual appearance of the flower-pot on the window ledge. It appeared to be filled with something black. He walked over and dug into the surface with his finger. Underneath was dry earth. It was just a thin layer of powder on top. He pursed his lips.

A sound behind made him wheel around, and gaze into the hall-way. Slowly there took shape in the darkness there a crouching, mottled figure. It was a man—half naked—whose skin was a dead grey in color—splotched with black. It was staring at him with wide, fixed eyes; and creeping forward with a convulsive motion of the lower legs. All the hope went out of him, as he recognized George Dixon. He cursed.

"George!—In God's name, what's the matter?"

Julius Humboldt had taken three quick steps forward when the other leaped. He had a flashing glimpse of wide eyes, flaring nostrils, bared teeth—and ducked instinctively. The flying body struck him a glancing blow on the shoulder, and crashed full-length on the floor. He stared at it, horrified.

"George.

The prostrate creature screamed, and beat the floor with its fists. Humboldt recoiled instinctively.

"Mad!" he breathed through white lips. He advanced gingerly; and, kneeling down, placed a hand gently on the other's shoulder. There came a quick, sharp snarl; and he snatched his hand violently from between the other's closing teeth.

Again he leaped back, and stood rigidly still. Hurried thoughts raced through his brain. He would have to do something for George—and do it quick. A doctor...?

He frowned irritably. What would a doctor do? He didn't want some fool messing around and making things worse. What would a doctor treat for? What was wrong with George?—that was the question.

HE had better assume it was the experiment that was doing it. He had been only half serious when he had warned George about it; but now... Obviously the experiment had been a success. George had found something—something that had consumed the food under that jar. Might as well call it "life" as anything else; although it must be totally different from terrestrial life. Something in the form of a ray—light ray, gamma ray—something that could pass through glass. Yes, he was pretty sure of that. But then what would it do?

He stood rigidly still, gazing with unseeing eyes down at the now quiet figure on the floor. He must marshal all the facts. He must understand this thing in order to conquer it....

George had babbled something about a geranium. Now, what... Suddenly he remembered the flower-pot, and his eyes widened. At last the thing became clear to him. He felt that he could visualize graphically what had happened—what was happening. Rays shooting out—radiating—in all directions from the jar; passing through the plant on the window ledge—and consuming it; passing through George....

He shuddered. The brain, the nerves—the most delicate organs—would go first, naturally. He must do something—get a doctor; a sedative might help. He left the room, and locked the door behind him. Making for the telephone stand, he tripped over something. It was the telephone. It was loose—the wires torn out of the box.

Well, there was an extension in George's bedroom. He took the stairs three at a time. There was a light in the room. He had just picked up the phone when something peculiar caught his eye. The bed sheet was a strange, dark grey in color. He bent closer. Yes—something wrong. He touched it, and started violently. The sheet crumbled to powder under his hand. He shook his head in bewilderment....

Obviously the sheet was affected in the same way as George and the geranium. But why the sheet? Why not something nearer the laboratory?... Then he gasped, as the full meaning of the phenomenon burst upon him. It was George that had infected the sheet. George was being fed on by the strange disease; therefore, George was giving off the rays—and in enormously greater quantities than the little block had done.

The horror of the situation overcame him, and he sat down heavily upon the bed. George broadcasting Death! He tried to look ahead—to understand the full significance of that fact.

George broadcasting Death—impregnating anything and everything that came near him. And then infected things radiating it, in their turn....

Where would it stop? What could stop it? He shrugged his shoulders helplessly. You couldn't fight a thing you knew nothing about.... The thing would spread like wild-fire. George was a menace to mankind—to all life—to the world!

Absent-mindedly he picked up the telephone; shrugged again; and set it down... Couldn't call a doctor. Couldn't call anybody. Nobody would understand. They would take George to a hospital where he would spread disaster at a terrific rate, or they would hang around and infect themselves; then go out and spread the thing. Warnings would be no use; people never paid any attention to warnings they could not understand. They would laugh at him; he could hear them....

"Life from the stars, indeed!... Disease from afar—ha, ha!" They would call him mad—and then fall victims to the thing they derided. And the minute a few were infected nothing could stop it. He, himself, knew more about it than anyone else; but he had no idea how it could be checked....

He wondered vaguely if he were infected. Perhaps not, in so short a time... Well, he would be, before he got through.

He would have to work alone... Work?—he drew his hand across his eyes.—Work?... On what? Grimly he considered. He couldn't leave George, certainly. Must try to save him, no matter how small the chances; must study the Rays—try to find out....

FROM below came a thud and a heavy pounding on the laboratory door. He shivered slightly.

What to do with George? Would have to keep him quiet. Frowning heavily, he descended the stairs. The racket in the laboratory was steadily increasing in volume. To the pounding was now added shrill, angry cries.

A hypodermic of some sort would be necessary for such noises would soon bring inquisitive people—and inquisitive people meant disaster. But how to get dope without a doctor? He knew of a doctor in the city who minded his own business; but deals like that required money, and he had no money.... Well, he had to do something right away. You could hear that howling a block awsy.

He unlocked the door. As he turned the knob, the door burst open, knocking him violently backwards. Before he could regain his balance the other was upon him. As he was borne to the floor, all other emotions were dominated by his amazement at the homicidal tendencies of this man who, a week ago, had been as mild-mannered and studious as one could wish.

He fought vainly against the powerful, frenzied grip on his throat. Blood pounded in his ears; his temples throbbed. With his one free hand he reached along the floor for something that he knew was there. He found it,—the telephone—and, swinging it up, relentlessly clubbed the head of his assailant. The grip on his throat relaxed, and the body of George Dixon rolled over limply on the floor. Getting to his feet, he raised it in his arms; and slowly mounted the stairs. He laid it on the bed and bent over it. Out for three or four hours, he decided with relief. He needed at least that.

He searched methodically through the clothes in the closet, but found only a little over six dollars. A further search of the bureau netted only the check-book of a local bank. He stared at this latter find long and thoroughly; then shook his head. No, he would try searching the rest of the house first. An hour's search, however, brought no results; and at seven o'clock he was seated at a desk with the check-book and one of George's letters before him.

Promptly at nine he was at the local bank. The young teller looked thoughtfully at the check he presented.

"Are you staying with Mr. Dixon, Mr.—Mr...?"

"Humboldt. Yes, I am."

"Well—it's a rather large—"

"If it is identification you want, I have a letter from Mr. Dixon to myself," said Humboldt brusquely.

The young man studied the proffered letter gravely. "All right, sir. You know we have to be careful, sir. How will you have it?...."

Humboldt caught the nine-fifteen train to the city. He sat huddled in the corner of a car, feeling very tired and a little sick. He felt that he was on a fool's errand. George, he knew, could not be saved; it was only a question of how long he would live. Not very long, probably. A thing that can attack vital nerves kills quickly....

Humboldt stirred uneasily in his seat. George's death, he reflected grimly, would not end the matter. Far from it!... There was enough substance in his body to feed the disease for weeks—months, perhaps. And throughout all that time the deadly radiations would continue—menacing all life, passing through all barriers....

All barriers?—He remained deep in thought during the rest of the journey. By the time the Pennsylvania Station was reached, he had come to a decision.

An hour later—richer by a few grams of morphine and a syringe; poorer by a considerable sum of money—he was studying a classified telephone directory. Finding what he wanted, he called a number, and gave an order. There appeared to be some difficulty at the other end; and he spoke irritably:—

"Yes—lead. Can you hear me?.... Good!—Do you have one, or not?... Good! I want immediate delivery.... What?.... I don't care what it costs.... Yes—this afternoon... Good!.... Get a truck. I will pay all delivery charges..."

HE gave the address, and hung up. The journey back to Great Neck he spent in deep thought. How to study the Rays? How to make them tangible—measurable?—An electroscope? Photographic plates?

He groaned in despair. All that was so arduous—so complicated; and he had need for speed. The Rays were spreading rapidly, he was certain; eating into the timbers of the house, into the ground, perhaps...

To his immense relief the house was quiet when he let himself in at the front door. He mounted the stairs on tip-toe, and cautiously unlocked the bedroom door. Caution left him, then; and for a moment he was overcome by nausea. Forcing himself, he approached, wide-eyed, the black lump on the bed. The head was bald, and the one ear that he could see was no more than a stump. The nose was a black wound in the ghastly face. The eyes were gone.

Fighting his disgust, he reached out a hand. The body felt like warm mud. He shuddered, and drew back... No need for the hyp now—but he was glad he had got the other thing....

His eye was caught by three ugly indentations in the skull. His work...

Horror surged up within him, and he dashed headlong from the room and down the stairs. He sank weakly into a chair in the living room. He was trembling; felt very tired—incapable of thought. He knew he had better get out of the house. Death was there. He imagined the Rays driving through the air about him. He felt that he could almost see them. They would be coming from many sources now—shooting in all directions....

His head fell back upon the cushion of the chair. He knew he must get up, but he needed a little rest. His strength was exhausted.... Suddenly his eyes became intent. He had been gazing at the ceiling, but had not until now noticed the dark, irregular stain in its center.

He wondered about it. It alarmed him, somehow....

What would cause such a stain? What was above this room? Feebly he concentrated on the problem. The stairs... the hall—to the right was—yes, George's bedroom! The Thing was lying there—yes, in the center right above the stain....

He shivered. He would have to get out; but he needed a little rest. He relaxed....

The stain had a peculiar shape. He decided that it had legs—a head—and one arm. He watched it steadily. It seemed to move a little....

Yes, it was moving! In sudden alarm, be struggled to rise; but could not. The one arm of the shape was stretching out towards him. He knew how it would feel—like warm mud.... His terror was a physical pain, but he could not move.

Suddenly it was all around him—the warm mud. He was sinking in it, and could not breathe. Death was near, but help was coming. He could hear it—a small bell, very faint. Then a booming sound. He renewed his struggles—and suddenly was free....

JULIUS HUMBOLDT opened his eyes, and leaped to his feet angrily, He had been asleep. Now there was somebody at the front door—ringing, knocking. He would have to go, but it was a damned nuisance! He stepped into the hall. Certainly didn't want visitors. But maybe it was...

He started slightly as he swung open the door, and saw the policeman. He remained silent, collecting his wits....

"Mr. Dixon home?" rumbled the officer.

Julius Humboldt put out his hand, and grasped the door-post. He stood perfectly still, frowning. Then:

"No. He is not at home," he said.

"No?"—the officer's tone was peculiar—"Well, maybe you know something about this.—Is your name Humboldt?"

"Yes,"—Humboldt stared fixedly at the slip of papers The officer shook it impatiently....

"Where'd you get this check?" he asked loudly.

"From Mr. Dixon."

"Yes?—Well, I wanna hear Dixon say that..." He took a step forward. Humboldt did not move.

"Mr. Dixon is not at home," he repeated.

THE officer growled. "Oh!—So you're gonna get hard, huh? You better be nice—get me? This here check is a phoney; an' I got a good mind to take you along to the station now!" He eyed the other's shabby clothes with extreme disfavour.

"You know that you can do nothing of the sort," pointed out Humboldt calmly, "until you have found Mr. Dixon."

"Well, I'm gonna find 'im soon enough. An' now I'm gonna search this house." He made another forward movement. Still Humboldt did not move.

"You have a warrant?"—his voice was cold.

Again the policeman stopped and glowered. "Hard guy, ain't yu?—Well—"

He was interrupted by the sound of a heavy truck rumbling up the drive. He turned. "What do these guys want?"

Humboldt's lips tightened. "That is none of your affair!"

"No?—We'll see about that.... Hey! What do you guys want?" He addressed the driver, who had by now climbed down from his seat.

The driver looked alarmed—then indignant. "Why, we got the coffin.... We was to deliver it here—a lead coffin. An' damned heavy it—"

"Oh, a coffin!" the officer cut in. He swung around upon Humboldt. "Is that all?.... Say there's something damned funny about this house...." He looked up and down, apparently including the entire house in his broad sneer. "We got a lot of complaints about noises in this house last night—screams like.... An' now a coffin!"

Suddenly he swung around, and bellowed at the gaping truck driver. "Take that thing down to the station-house, an' leave it there. We don't have no funerals around here without the undertaker! And as for you—" he turned to Humboldt—"I'm comin' back—get me?....With a warrant—"

Suddenly he stopped, and gaped at the other. "What the hell have you got on your face?"

A chill shot through Humboldt. He stiffened. Then: "That, also, is none of your affair," he said softly.

The officer favored him with a look of concentrated venom. "All right, Wise Guy—you wait!"—he stamped down the steps. Humboldt closed the door.

He walked very slowly, and with clenched fists, to a mirror. One glance was enough to tell him what he wanted to know, but he stared for a long time with a kind of fascination at his terrible face. Then he turned, and walked out of the house. He noted without surprise—scarcely with interest—that the grass, up against the front of the porch, was black—burnt-looking. He looked up at the window of George's bedroom.

A maple tree grew near the house, and a large branch forked towards that window. The leaves were not green. They, too, were black and burnt-looking. Humboldt laughed harshly.

Study the Rays! Much chance he would have! You couldn't study a thing that crumbled your body—stole your reason... Even his one little gesture had been thwarted, he thought bitterly. He had hoped to protect the world from George with a lead shield. And they had taken that....

He would be the second to go—but not the last. Perhaps the policeman would be the third. He would warn him....

Warn him! Again he laughed. He would say, "Don't go into that house—warrant or no warrant. In there is invisible Death. I don't know what it is. It comes from out of the skies."

And the policeman would say, "Gettin' funny, huh?"

But even if the policeman were convinced, and didn't go in, the Rays would spread—through the grass, through the trees, through the ground. How much air could they traverse?

What were they? He called them "Rays". He had made a word picture for them. But it was just a word picture—nothing more. This he knew: that they were something that fed on earthly substances—mainly living things, it seemed. How could you stop a thing like that...?

He stiffened suddenly; his jaw set; and he strode swiftly to the road, and down the hill towards the town. He would try once more. He might beat the policeman to it. He smiled grimly. Thief, forger, buyer of drugs, possibly murderer—he would try to beat the Law once again. He would commit one more crime—perhaps two....

Ten minutes brought him to a filling station. "Do you have any five-gallon tins?" he inquired of the attendant.

"Yes, sir!"

"Well, my car is out of gas—up in Mr. Dixon's garage. I want you to fill two tins, and drive me up there."

"Well, I can give you a gallon; and then you can stop by here, and—"

"Do what I say!" snapped Humboldt, "and don't stand too near me."

The other merely gaped at him.

"Get it!"—Humboldt threw a roll of bills at the attendant. The latter succeeded in mastering his astonishment.

"Yes, sir!" he cried. He filled the cans, and placed them in a rickety car. Humboldt got into the back seat.

"Go up the driveway, and set them down at the front," he directed. The other pulled up before the front steps.

"Don't you want them in the garage?" he objected.

"Do as I say," said Humboldt again. The man deposited the cans on the steps, and prepared to go.

"Had a fire?" he inquired chattily, looking around at the grass.

Humboldt did not answer. He lifted one of the cans, and lugged it into the house. He heard the car rattle away.

From the kitchen, at the back of the house, he secured a dipper; and began methodically to scatter the liquid in all the rooms—on the floors, walls, ceilings, and furniture. He hurried, running from one room to another. His legs felt numb; he was a little dizzy; and then there was the policeman....

He went upstairs. In one of the rooms he found a closet, which had a tiny window looking out upon a grove of trees at the back of the house.

"Private in back," he muttered, with an approving smile. Then he tried the key in the lock, and put it on the inside. He went on with this work. Upon the thing that had been George Dixon he poured a gallon of the fluid. Then he went downstairs and out of the house.

There was no one in sight. The grounds were fairly spacious, the nearest house being over three hundred yards away. Slowly he walked around the house, emptying his second tin on the walls and porches—on the grass. Lastly, he laid a little train of it out across the back yard.... It was getting dark.

He lighted a cigarette; and, stooping, dropped the match on the last little splotch of gasoline. A tiny flame shot up, and ran towards the house.

He walked slowly around to the front; and went in, locking the door behind him. He sat down on the staircase; and, reaching into his pocket, drew out the little bottle of morphine and the syringe. Might as well make use of it, after all, he thought with some satisfaction.

The sight of his hands sickened him: ugly, black—looked as if they might fall apart.... He charged the syringe from the bottle.

Perhaps he was saving other people from having hands like this. Deprived of food, this "life" or whatever it was from another star, might die a natural death. Then again it might not. But the chances were that he was doing a whole lot of people a lot of good....

He dug the needle into his leg, and laughed. Anyway, he had nothing to lose! A fine hero!.... Julius Humboldt had always found it hard to be sentimental.... He got to his feet, and slowly climbed the stairs. It was difficult to move. He went into the closet, and lifted the tiny window. A roar and a wave of hot air greeted him. He drew back with a smile, and locked the closet door.

A tongue of flame shot up past the window, licking at the sill. He gazed at it admiringly. Wonderful stuff—fire!.... Clean.... pure.... vital.... Highest state of matter.

The heat was choking him now The roaring and the heat were now tremendous.... He laughed.

Robbery... forgery... murder... arson... and now, one more!

He tossed the key into the flame.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.