RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

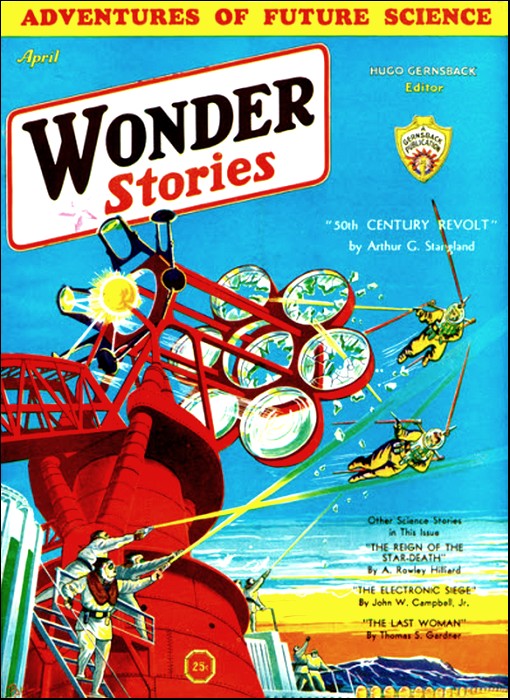

Wonder Stories, April 1932, with "Reign Of The Star-Death"

Alec Rowley Hilliard was an American writer who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. He was born on July 7, 1908, and passed away on July 1, 1951, at the age of 42 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Originally from Ithaca, New York, Hilliard was remembered in his obituary as a dedicated professional. He was survived by his wife, Annabel Needham Hilliard, their two children—Elizabeth Janet and Edmund Needham Hilliard—as well as his mother, Esther R. Fiske, and a sister, Elizabeth Hilliard. He was laid to rest at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca.

THE great chorus of applause that greeted Mr. Hilliard's finely worked out "Death from the Stars" led us to ask him for a sequel. We felt that the mystery of the Death was not fully explained, nor had its career of terror ended. From this marvelous and gripping sequel we see that the terror has but begun, and that before it ends it will have plunged civilization into as great a Crisis as it has yet faced.

Mr. Hilliard poses the question, suppose in order to save a million people it is necessary to kill in cold blood ten thousand innocents? What should society do? What would you do if you had the power to save or condemn the ten thousand and endanger the million? What would you do if you were one of the ten thousand condemned, or one of the million threatened by the ten thousand? This story is a gripping challenge to our modern civilization, as well as a thrill story from the first word to the last.

THE Coroner cleared his throat, and spoke briefly to the jury. "Now, gentlemen, you are acquainted with the—ah—the external circumstances of the tragedy. You have seen photographs of the burned house in Great Neck and of the—ah—gruesome remains. You have heard medical testimony to the effect that these remains constitute the charred bones of two men. It would appear, therefore, that they were burned to death. But—"

The pause that the Coroner had meant to be impressive was rendered rather ridiculous by his obviously painful excitement and by the nervous twitching of his upraised hand. He was a small, sandy-haired man, with light-blue eyes that blinked quickly at irregular intervals. It was clear to everybody in the room that his official duties weighed upon him heavily.

—"But," he continued shrilly, "in an event so strange, so inexplicable as this, we must look beneath first causes. Our task, gentlemen, is to determine not only the manner of death, but also the reason for the death of these two men. In other words,"—here the Coroner, by lowering his voice and almost whispering his next words, managed to get a really fine dramatic effect—"has murder been done?... Or," he added, relaxing and smiling feebly, "was the whole thing just an accident?"

His audience, understanding these questions to be purely rhetorical, kept silent. The Jury, to a man, leaned forward eagerly, paying tribute to the speaker's eloquence, as did the row of witnesses and the bloc of mere spectators. Only the newspaper reporters and the attendants appeared unmoved.

"We must probe deeper into this mystery," continued the Coroner grandly. "And I think our first concern should be to establish definitely the identity of the two men who we are morally certain were the victims of this—ah—this tragedy... About one of them we are fairly certain. He was George Dixon, owner of the house—a young bachelor, who lived there alone. He was a scientist and writer. He had lived in Great Neck for years, and was highly respected by everyone who knew him...

"But the other,"—here the Coroner lowered his voice again, significantly—"the second man—is mysterious. He was a stranger in Great Neck; no one there remembered ever having seen him before the day of the fire. Only his name was known—Julius Humboldt; and for a time I despaired of finding out anything else about him. Then Dr. Herbert Jules came to my aid. I am sure Dr. Jules needs no introduction. I am going to ask him to take the stand."

Herbert Jules was well known in Nassau County, because he was a considerable landholder, and because of his wider fame as a scientist. Furthermore, the name of his late father, Lorian P. Jules, was literally a byword throughout the whole of Long Island. He it had been who rid the territory of the menace of the man-hunting weasels which, ten years before, had threatened the destruction of the whole of New York City.[*] Lorian Jules, experimenting with X-rays on animals, had created the beasts; and they had gotten out of his control, running wild over the Island, slaying men and women for their food. The story of his struggle with them had thrilled the country; and his final victory had raised him to the stature of a national hero.

[*] See "The Avenging Ray," Spring 1931 Wonder Stories Quarterly.

Herbert Jules' testimony, after the Coroner's dramatic introduction, came somewhat in the nature of an anticlimax. He was a cool, calm-looking man—of medium height and slim, dressed immaculately in dark, well-fitting clothes. His small, neat, black beard and the ribboned, rimless pince-nez he wore heightened his matter-of-fact professional air; and his testimony was in keeping with his person.

He explained briefly that he had met Julius Humboldt at Columbia University when the latter had been teaching biology at that institution; that he knew that Humboldt had since left Columbia, but had no idea where he had gone; and he finished with a few remarks regarding Humboldt's character, the substance of which was that he had appeared to be a man of the highest integrity in no way addicted to violent or criminal activities.

The net result of Jules' testimony was to release the tension in the room considerably. The Jury relaxed, obviously feeling that the Coroner's "mysterious stranger" had turned out to be something of a flop. That gentleman, however, was only slightly damped; and when Jules had finished he rose nobly to the occasion, with the assurance of a man who has the facts on his side.

"Thank you, Dr. Jules," he said graciously. "Humboldt may be blameless, as you say; but there are several strange things that must be explained before we can be satisfied about it... Now the clerk will read the testimony of Police Officer Patrick O'Brien, who is unwell and not able to attend this inquest. Officer O'Brien was sent up to the Dixon house on the afternoon of the fire, because a neighbor had reported strange sounds and—ah—screams coming from the house earlier in the day..."

OFFICER O'BRIEN'S testimony was to the effect that, arriving at the Dixon house, he had been met at the door by the man Humboldt, who had refused him admittance, saying Dixon was not at home. Wanting to do his job well, he had argued with the man Humboldt, but to no avail; the latter would not admit him. Finally the officer had gone off to get the advice of his superiors—and a search warrant if they thought it necessary. When he did return, it was to find the house in flames—flames that quickly reduced it to a pile of ashes and débris.

But what chiefly interested the hearers were three apparently irrelevant items of information in the officer's report. They are perhaps best told in his own words, as read by the Clerk.

The first came near the beginning of the document:

"When I first got there, I was looking around; and it looked like they'd had a fire. The grass up against the house was all black and burnt-looking. I walked around to the back. It was like that all the way around. Then I rang the doorbell..."

Again:

"...While I was talking to him" (Humboldt) "I was looking at his face, and there was something wrong with it. The skin was all grey, and there was black splotches. I said, 'What's that on your face?'; and he jumped and sort of drew back, but didn't say anything..."

And again:

"... I was just leaving, when a big truck drives up to the door. I saw Humboldt looking at it sort of nervous, so I said to the driver, 'Well, what do you want?' The driver says, 'I got the coffin.' 'Coffin?' I says. 'Yeah, the lead coffin,' he says...

"'What's that for?' I says to Humboldt. He said it wasn't any of my business, but I said it darn well was my business. 'We don't have any funerals around here without the undertaker,' I says. Then I told the driver to take the coffin down to the police station. Humboldt didn't say anything..."

This last item caused something of a stir in the room—a stir which the Coroner seemed to regard in the light of a personal triumph.

"That coffin is still at the police station in Great Neck," he said impressively. "It is made entirely of lead, about an inch and a half thick. We have discovered that Humboldt ordered it by telephone from a firm in the city. He made it a rush order, and said he would pay anything to get it by that afternoon!"

The coroner paused, and there came an appreciative murmur from his audience. Dr. Herbert Jules, sitting near the front of the room, stared fixedly into space, a slight frown creasing his high forehead. He no longer appeared to be listening.

"Now we will hear from John Pew, who operates a gasoline filling station on Soundview Avenue not far from the Dixon house..."

Mr. Pew, taking the stand, deposed that he had sold to the man Humboldt ten gallons of gasoline, in tins, on the afternoon of the fire, at exactly five-thirty.

"You will note, gentlemen," said the Coroner, "that this transaction took place just fifteen minutes after Officer O'Brien left that house, threatening to return..."

Mr. Pew then went on to explain how he had taken the gasoline up to the Dixon house in his car. He confirmed Officer O'Brien's report on the strange appearance of the grass, and:

"Yeah. There sure was somethin' wrong with his face. The skin was all black and rotten-looking... He acted queer, too. He seemed awful anxious to get rid of me; and he said, 'Don't stand near me. Keep away!'..."

Herbert Jules started violently in his seat, and from then on paid not the slightest attention to the further proceedings of the inquest, which consisted, in the main, of a very fine speech by the Coroner to the Jury. Jules roused himself in time to hear the painfully indecisive final verdict of that latter organ, which stated, in effect, that the deceased, George Dixon of Great Neck, Nassau County, State of New York, and Julius Humboldt, place of residence unknown, had met their deaths, probably by burning (although not necessarily); the reason for death being, in the case of Julius Humboldt, probably suicide, and in the case of George Dixon, possibly murder at the hand of the aforesaid Humboldt (although not by any means necessarily).

DR. JULES, having caught the Coroner's eye, remained in his seat while the assemblage dispersed; and, when the latter had finally got rid of the somewhat derisive newspaper reporters, arose and approached him. The Coroner was plainly unhappy, and was talking to himself in a low, sad voice.

"Most unsatisfactory! Most unsatisfactory! I had hoped for something definite. Murder and suicide; murder and suicide—that was it... And yet—" He wrung his hands, and gazed at Jules. "Mysterious business!... No head or tail... No—"

"Mysterious is the word, Dr. Gibbs," put in Jules kindly. "I think you did remarkably well under the circumstances."

"Thank you, sir... Thank you!" exclaimed the little man gratefully. "I did my best... But I must be frank with you, Doctor. I don't understand it—not a bit! There are too many unexplained circumstances."

"Yes." Jules nodded slowly. "There are." After a short pause he asked, "Do you happen to know what is the matter with Officer O'Brien?"

Gibbs looked vague. "Well, no—I don't. I just heard he was unwell, and hadn't reported for duty."

"Where is he—do you know?"

"Yes. He is at home. He has a small farm outside of Port Washington. Raises chickens... My secretary had to go out there to take his statement, day before yesterday. Said O'Brien was just feeling bad. Hadn't needed medical attention..."

"You are County Health Officer, are you not?"

"Yes," admitted Gibbs.

"Are you busy this afternoon?"

"Well, I have nothing more than my usual routine," said Gibbs hesitantly. "Why, Doctor?"

"I am driving out to Port Washington, and I wish you would come along." Jules glanced at his watch. "It is now twelve-thirty. My car is outside. We should be back before two." He looked questioningly at the other.

"Why, certainly... I—" began Gibbs confusedly. Then his eyes widened. "O'Brien? You mean—"

"I mean that I am a little worried about Officer O'Brien," said Jules quietly. "I should feel easier if I knew exactly what was wrong with him." He gestured towards the door. "Shall we go? We can talk in the car."

Outside, they entered Jules' large and luxurious car. Jules spoke to the driver. "We are going to Port Washington, Jeremy. After that, Dr. Gibbs will direct you."

As they rolled out of Mineola, Gibbs fidgeted visibly. Soon he became vocal. "Do you think there might be some connection, sir, between O'Brien's illness and—and this other business?"

"It seems hardly possible, I admit," smiled Jules. Then he continued seriously, "But that bare possibility worries me so much that I am willing to cause you all this trouble on account of it."

Gibbs said it was no trouble at all, and maintained his questioning attitude.

"Do you," asked Jules slowly, "remember Mr. Pew's statement that Humboldt said to him, 'Don't stand near me. Keep away!'?... What does that suggest to you?"

"I've been wondering about that." Gibbs pursed his lips, and nodded jerkily. "Sounds crazy..."

"Suppose we assume him sane," insisted Jules. "What then?"

The Coroner considered. Then: "Well, there might have been something Humboldt didn't want Pew to see. The black spots!"

"Pew could see the black spots very plainly," Jules reminded him patiently. "You are making the mistake, Dr. Gibbs, of assuming Humboldt to have been a villain. Concede him altruistic motives for a moment. Suppose it was Pew he was worried about—not himself..."

"Oh!" Gibbs started, and his eyes widened. "You think there was something wrong with Humboldt that—that could have hurt Pew...?"

"That is what I am afraid of." Jules shifted in his seat, and looked earnestly at the other. "I hope you won't think me an alarmist, Dr. Gibbs; but let us suppose one more thing. Suppose that, arriving at O'Brien's farm, we should find his face blackened, in splotches or spots..."

THE Coroner gasped. "Disease!... But—but I don't know of any disease like that..."

"Nor I."

Jules was silent for a time. Then: "What does a lead coffin suggest to you?"

"I don't understand that at all," confessed Gibbs.

"To the scientist," continued Jules, "I believe that lead suggests, primarily, a shield—a barrier. At least, that is what occurred to me immediately when I heard it mentioned... And then, that black grass..." Jules' voice trailed off into nothingness, and for a time there was silence in the car.

"Do you—don't you think he wanted the coffin for Dixon?" ventured Gibbs.

"Yes, I think so," answered Jules abstractedly. Suddenly he shook himself, and straightened in his seat, his lips tightly pressed together. "I can't rid myself of a feeling of foreboding," he said; and continued in a low voice, "Gibbs, there was something terrible in that house—something weird and deadly—something that had Humboldt in its power. He was fighting for his life—and for the lives of others..."

"I knew there was something out of the ordinary, but I don't understand it at all," said Gibbs helplessly.

"I have the advantage of you," replied Jules. "I have scientific training, and I have run across a clue that you would naturally have missed. I call it a clue. It may be nothing of the sort. It may be an entirely unrelated incident. But, at the risk of making you think I have taken leave of my senses, I am going to tell you about it.

"About a month ago I happened to be looking through a scientific periodical, and I ran across an article by this same George Dixon. He was expounding a theory. His theory was, in short, that there might very easily be life existing in a state of suspended animation in substances deposited on this earth from outside—that is, in meteorites..."

Mr. Gibbs looked shocked, but made no comment.

"This is by no means a new idea," continued Jules. "Many have used it to explain the advent of life on our planet. The novelty in Dixon's case was that he planned to do something about it. He had a meteorite, and he was experimenting on it—searching for the life he believed was there."

"Well!" said Mr. Gibbs blankly.

"'Life' is, of course, hard to define. We know, in a general way, what it is on our own earth. But what is it in other worlds? How would one recognize it? Dixon planned to use the function assimilation as an indicator. He was looking for something that increased itself at the expense of other things. Perhaps he found it, perhaps he didn't; but if he had—that would explain a great deal!"

They were in Port Washington. Gibbs directed the driver to continue north, out to Manhasset Neck, for three miles, then to turn right on a small dirt road.

"You see, Gibbs," continued Jules, "it is all very well to talk about 'life from another world'; but, when you have found it, what then? The chances are it has developed under a set of conditions entirely different from your own. How will it act? Will you know it when you see it? And, above all, will you be able to handle it? Assuming it to be 'something that increases itself at the expense of other things'—what will those other things be? What will it attack?...

"It seems to me that Dixon's experiment was a dangerous one. I doubt if he fully realized its danger—at first, anyway..."

Gibbs was sitting on the edge of his seat, his eyes wide, his mouth half open. He looked bewildered and unhappy. Suddenly Herbert Jules relaxed, and smiled at him.

"You are probably thinking I have gone out of my head; and I have no doubt you are right. My over-developed imagination often runs away with me. So if our trip is all for nothing, I hope you will be charitable and not tell too many people about it... Now, I judge we have arrived."

Their car had been bumping down a narrow dirt road through the woods, and now drew up before a green-painted gate. They descended, and stood for a moment looking at the small, neat cottage, the fenced-in chicken yard, the well-kept lawn and shrubbery.

"A charming place!" exclaimed Jules. He pushed through the gate, and walked slowly down the path, Gibbs following. His eyes were darting to right and left. Suddenly he stopped, and said, "Look!"

GIBBS followed the direction of his gaze. The wire fence of the chicken yard was nailed to the left-hand corner of the house. The green lawn stretched right up to this fence. But at the very corner, up against the house, was a place where the grass was gone. In its place was a little patch of jet-black dust. And directly on the other side of the fence from this patch, two hens lay on their sides, clucking softly and flapping their wings in feeble spasms.

"Come," said Jules briefly. He threw open the front door, and they entered the large central room of the cottage. "Only one story," he muttered. He glanced around.

To their right, two doors led off—to their left, one. Quickly Jules flung open the two doors on the right, revealing a kitchen and a workshop—both untenanted. He pointed to the third door.

"Gibbs," he said levelly, "that is the corner room next to the chicken yard. O'Brien is in that room. I don't know how far gone he will be; but it's up to us to find out. We must go in there, but we cannot stay long... No matter what you see there—when I say get out, get out!... Understand?"

"Yes, Doctor—yes!" Gibbs nodded vigorously.

Jules stepped quickly forward, and opened the door. The room was empty. Jules stared at the rumpled bed.

"Gone," he said softly, and repeated, "Gone!"

Suddenly he stiffened. From under the bed came a scratching sound, and a low, whining growl. They backed away, as there emerged a strange creature. It was a dog; but it was hairless, and coal-black; and its eyes were gone. It was sniffing at them, and moving forward with jerky convulsive movements.

"Look out!" cried Jules.

The creature howled suddenly, and leaped directly at them. The two men backed through the doorway into the large room; but the dog's leap brought it into contact with Gibbs, and it fastened its teeth tightly about his ankle.

"It's mad!" he screamed.

On the table in the center of the room lay a revolver. Without hesitation Jules placed it against the dog's head and fired, once. The animal crumpled to the floor. "It was worse than mad," he said grimly. He looked thoughtfully at the revolver. "O'Brien must have forgotten this," he said. He slipped it into a side pocket. Then:

"Gibbs, we've got to find O'Brien—in a hurry! Now, let's get out of here!"

Outside again, they heard themselves hailed. A man was leaning over the gate. "Lookin' fer O'Brien?" he inquired.

"Yes," said Jules briefly. Followed by Gibbs, he made for the car.

"Well, he's gone to the city."

"What!" cried Jules.

"Yeah. He come over to my place about an hour ago, wantin' to use my telephone. Said he was sick; an' he sure looked it! Said he was going into the city to see a specialist, an' had to make the one-fifteen train. He drove away about ten minutes ago. You jest missed 'im..."

Jules swung around upon the driver. "Did we pass any cars on this road, Jeremy?"

"Yes, sir. A Ford... Just as we turned in."

Jules jerked out his watch. "Can we get to the Port Washington station in six minutes?"

"Yes, sir!" said Jeremy confidently.

"Turn the car!" snapped Jules. He spoke to the gaping man: "Did O'Brien get near you?"

"Why, no—not very," began the man slowly.

"Was he in your house long?"

"Jest a few minutes... Say! What in thunder—?"

Jules cut him short. "Listen! O'Brien is suffering from a terrible disease. Don't go near his house. Don't let anybody else go near it!... Come, Gibbs!"

The car swung around beside them, and the two leaped in. It started with a roar.

"Gibbs,"—Jules spoke rapidly—"that cottage has got to be burned—that and the grounds around it. If we don't stop this thing, you are going to wish you never were County Health Officer! It's something new—understand? I called it a disease, but it's not that, as we understand the term. It's a new activity—unearthly—from another world!"

Gibbs rallied himself, to make a feeble protest. "Doctor Jules, are you sure...?"

"I am certain!... Now, listen. Here's the solution to your Great Neck mystery. Humboldt burned that house—and himself—for the same reason you're going to burn the cottage, trying to end this thing... Dixon was dead—killed by the thing he let out of that meteorite—the thing he was looking for, but couldn't understand. He couldn't deal with it because it was entirely different from anything he had ever experienced... It passes through walls, glass, everything; and it attacks all living things. That explains the black grass around the house. That explains Humboldt's lead coffin. He was looking for something that would hold it—stop it spreading from Dixon's body. And all the time he was rotting, himself—rotting and dying. God!"

Their car was careening through the outskirts of the town. Jules glanced at his watch, and nodded jerkily.

"Now do you see why we've got to stop O'Brien—at all costs?"

"Y-yes." Gibbs was blinking rapidly, and trembling with excitement. "But—but—" he began, and choked. He was still making ineffectual noises when the car skidded to a stop beside the station platform.

PORT WASHINGTON is at the end of a branch of the Long Island Railroad; and the train was in the station, waiting to pull out, when Jules leaped to the platform.

A man in a blue uniform was walking slowly towards the steps of one of the cars. Seeing him, Jules cried, "O'Brien!"

The man stopped, and turned. He peered uncertainly in Jules' direction. Jules approached, eyeing him intently. O'Brien was a middle-aged, heavily built man with a square, bull-dog jaw and generally truculent air. He appeared unable to focus his eyes on Jules; and when he tried to stand still he swayed violently, taking quick sidesteps to keep his balance. Jules stopped a few feet from him, and said quietly, "O'Brien, you are a very sick man. I have brought a car to take you where you will be cared for properly."

The policeman growled. "Who're you? I know I'm sick, don't I?" Swinging about, he lurched towards the train steps.

Jules followed him quickly, saying, "Wait!"

O'Brien swung around, clenching his fists; and said testily, "Listen, Mister, I don't feel good enough to argue with you now, so—"

"You've got to listen to me," said Jules tensely. "You are suffering from a highly contagious disease. If you get on that train,"—he gestured at the nearest car, where rows of interested faces were peering at them through the windows—"you will seriously endanger the life of every passenger..."

O'Brien appeared to hesitate. "But—" he began. Two sharp whistles came from the train. "But, Mister, I've got to go to New York." He raised his hand weakly, and stroked the large squares of court-plaster that almost covered his face. "He—the doctor—he said if I didn't hurry I might die... An' he didn't say nothin' about it bein' catching..."

The train was moving slowly. Muttering unintelligibly, O'Brien turned, and grasped at one of the hand-rails. Jules spoke with desperate emphasis.

"You can't go, O'Brien. You'll kill every man and woman in the car with you. You—" Jules stopped suddenly, realizing his mistake. O'Brien had pulled himself to the steps. Now he turned angrily, baring his teeth.

"Yeah!" he snarled. "You're the guy was gonna save me—an' now you say you can't save nobody." He spat viciously. "Go to hell!"

The train was picking up speed. Jules saw O'Brien, still on the steps, moving rapidly away from him. He was aware of Gibbs beside him, chattering in a high, distressed voice. "You can't stop him, Doctor! We have no right—no authority. We—"

Jules sprinted beside the train. When he came parallel with the steps he clutched at O'Brien's leg. Chuckling harshly, O'Brien bent up his knee, and then straightened it suddenly. The kick caught Jules beside the head. He whirled around, lost his balance, and fell heavily. Panting, he drew himself up on one knee. He could still see O'Brien, who was swaying on the steps, clutching at the hand-rails. Jules took the revolver out of his pocket; and, aiming carefully, fired once.

O'Brien toppled slowly from the steps, at the very end of the station platform. His head struck first, with a sharp, cracking thud; and he lay still, face up.

Jules stood up, still holding the revolver. When the agitated Gibbs reached him, he did not turn his head or take his eyes off of O'Brien. He spoke through stiff lips.

"Find out how badly he is hurt—quickly!"

The train was grinding to a stop. Gibbs approached the quiet figure on the platform, and knelt over it. In a moment he was facing Jules.

"Dead!" he said pallidly.

All around were shouts and the thudding of footsteps. People were running towards them from the station and street.

"Come back here," said Jules tonelessly.

Gibbs came back, wringing his hands. "My God, Jules! This is awful..."

"Yes," Jules agreed grimly. "Now, Gibbs," he went on, speaking low and very fast, "you've got to keep faith with me. No matter what happens to me, you follow my directions. Understand?... It's your job..."

FROM the rear of the now stationary train excited people were pouring out. More were arriving from other directions. They were shouting at Jules and Gibbs, and they were crowding curiously towards the body of O'Brien. Jules looked up, frowning. He raised his voice, saying very slowly and distinctly, "Get away from that body. Stand back!" At the same time, he moved the muzzle of the revolver steadily to right and left.

His gesture had the desired effect. With startled shouts from the men and screams from the women, the front rank of the crowd surged back, fighting with the others to get out of range. Came the sound of a police whistle.

Jules was speaking sharply to Gibbs: "You must take charge. Allow no one within twenty feet of it. Get that lead coffin from Great Neck. In a hurry. Put the body into it. Permit no autopsy. You have performed the autopsy already. Understand?... Now go and find a policeman."

The last order was unnecessary. Three policemen were running towards them, splitting a path through the crowd. The foremost was hurling out commands and questions...

"Out of the way, you!... What's happened here?... Hey—drop that gun!"

Jules did not drop the gun; but leveled it again at the crowd, which, reassured by the policemen's presence, was surging closer to O'Brien's body. A second backward movement was the immediate result. Gibbs perceived the necessity for action. He stepped in front of the foremost policeman, as the latter came charging up.

"Officer, I am Gibbs, County Health Officer..."

"Yes, sir... But—" The officer was impatiently trying to get past Gibbs, but the latter held his ground. He pointed to the body.

"That man had a terrible disease... Contagious... Don't let anyone get near the body."

"All right, sir. We'll throw a cordon around it." The officer finally managed to push his way past the other. "Now, what happened? Hey!" he exclaimed suddenly, "It's O'Brien—the Great Neck man..."

"He was shot through the leg," explained Gibbs. "He fell from the train, and fractured his skull..."

"But who shot him?" thundered the distracted policeman.

"I shot him." Jules handed him the gun.

The officer gaped into his calm face. Finally: "Well, what'd you shoot him for?" he exploded.

"There is no use going into that now, I am afraid," answered Jules a little wearily. "It was necessary."

"Oh yeah? Well—" The officer's indignant retort was cut short suddenly as a light of recognition came into his face... "Say! Ain't you Herbert Jules...?"

"Yes," Jules nodded. He looked tired. His clothing was white with dust; and above his right eye was a small cut from which the blood trickled. His countenance, however, was impassive, expressionless, as he faced the officer. The latter looked uncomfortable. He was silent for a moment, shifting from one foot to the other and scratching his head uneasily. To him the name Jules stood for all that was respectable, correct, and even admirable. It stood high among the great names of residents of Long Island, of which there were many. Yet here was Herbert Jules calmly admitting he had just shot a policeman—shot him and killed him, apparently. The officer felt confused.

It was with relief that he remembered suddenly that his responsibility was not judicial in scope. His duty was perfectly clear...

"Well, sir," he sighed, "I suppose you know we gotta send you to Mineola..."

"Of course," said Jules quickly. "My car is here—with a driver. Can that be used?"

"Yes, sir. Sure! But we'll need to send a man..."

"Of course," repeated Jules. He turned to Gibbs, who with the help of the two other policemen was busy keeping back the crowd. "Dr. Gibbs, I think you should take care of that cottage tomorrow morning at the latest. It should have a guard around it now. Good luck!"

Gibbs held out his hand. "Good luck to you, sir," he said fervently. "I'll do it."

Dr. Jules was taken to Mineola; and, that night, lodged in the Nassau County jail. On the following morning, before Supreme Court Justice Wilkerson, he was indicted on a charge of Second Degree Murder and pled "Not Guilty." The trial date was not definitely fixed. In spite of the Judge's anxious and friendly inquiries, Jules refused at the time to give any explanation of his conduct. He wanted time to think; realizing, with a feeling closely akin to fear, that his explanations, expressed in their present form, would sound hopelessly wild and unconvincing in a court of law.

REGRETFULLY the Judge explained that, because of the seriousness of the indictment, bail could not be admitted. Jules was forthwith returned to his cell.

There he immediately began reviewing in his mind the events of the last twenty-four hours, the facts of which he could be certain, and particularly the theories he had evolved to explain those facts. It was borne in upon him more and more oppressively every moment how definitely and inescapably he was now committed to those theories of his—those theories so hastily evolved and so little considered.

His scientific mind now rebelled against conclusions so recklessly drawn, as he realized how scanty and bizarre was the evidence in support of them. Again and again he went over in his mind the train of reasoning which had led him so quickly into violent action; and each time it appeared more flimsy than the last, until it seemed to him he must have been mad the day before.

In this state of mind, he refused to see anybody—even his frantic lawyer. He was determined first to decide for himself whether he had been justified in shooting O'Brien—or whether he had merely committed a murderous mistake. He could not, however, refuse to see Dan Hogan, because Dan Hogan was Sheriff, and an extremely forceful man.

Hogan had been on vacation, in the Adirondacks; but, getting news of the Port Washington tragedy, chartered an airplane, and arrived in Mineola on the second day of Jules' incarceration. Proceeding directly to his office, he sent for Jules; and, when the latter had been brought in, cleared the place of policemen and locked the door.

"Jules, what in God's name is this all about?" he cried, waving the other to a chair with a wide gesture of one of his great arms. He was a mountain of a man, Hogan, with powerful, broad body and handsome, leonine head. Usually slow-spoken, the present torrential character of his speech testified to his extreme agitation. Jules, although still in an unsettled frame of mind, felt that he would rather talk to Hogan than to anyone else.

The two had been friends for years; meeting weekly at the local Chess Club, and repairing thereafter to a smoky, comfortable study in Jules' home, where they invariably sat until dawn, talking and arguing meditatively on any and all subjects. Hogan's duties as County Sheriff consumed only a very small part of his tremendous energy. His questing mind found in Jules a storehouse of information and ideas which he pillaged enthusiastically. Herbert Jules, on the other hand, found Hogan's intellectual curiosity a mental stimulus and a valuable agent for clarifying his ideas.

Now, therefore, he felt a certain relief at the prospect of unburdening himself to the other.

"Good of you to come," he said quietly. Of the two, he was by far the calmer, externally; but the lines of care on his forehead and about his mouth testified to the long hours of mental distress he had gone through.

"Good of me!" bellowed Hogan. He waved his arms about indignantly. Then he sat down heavily, and began to speak more slowly. "Jules, I'm a man that likes to get my facts straight from headquarters. Now, did you, or did you not, shoot a copper off a train in Port Washington, day before yesterday?"

"I did."

Hogan threw himself back in his chair, expelling a long breath. "Why?"

When Jules did not answer immediately, he said, "Not that you have to tell me if you don't want to, Jules, of course. But I'd like to know. You don't generally do things without good reason. I talked to Gibbs for a minute, but I couldn't get anything sensible out of him. Lot of stuff about shooting-stars and dogs... No Jules, it's not curiosity. I'm no lawyer, but I can help."

Jules started to speak, quietly, looking directly at the other. "Dan, when I shot and killed that man I believed implicitly—without the shadow of a doubt—that I was doing right..."

After a short pause, during which Hogan nodded vigorously, Jules went on: "Murder, of course, is an act hard to justify. I remember your once saying that it could never be justified. I think I argued with you then, holding that situations might occur which would make it not only justifiable but necessary."

Hogan was shifting in his chair restively, and was about to speak when Jules continued: "Now, I believe I have a good example..." He went on to tell briefly, the story of the day of O'Brien's death; beginning with the Coroner's inquest, and concluding:

"He was on the train—about to enter a crowded car. This is the way the situation appeared to me: He was carrying with him—Death. By the time the train reached New York, every occupant of the car would also be carrying Death—carrying it through the populous city—a death no man can understand, fight, or avoid..."

HOGAN'S heavy breathing was the only sound in the room. He sat far forward in his chair, his elbows resting on its arms, his hands tightly clasped together. He was frowning down at his hands, jaw outthrust and forehead deeply creased. Twice he started to speak and stopped. Then:

"Oh dammit, Jules!" he exploded. "Of course you did right, if—if—" He stumbled into silence, shaking his head.

"Yes?" said Jules encouragingly. He was well aware of what was coming.

"—If there is any such thing as this Death you're talking about!"

In those words Jules heard expressed the doubt that had obsessed him—and come near to maddening him—during the long hours alone in his cell. But, now that he heard it expressed by another, he realized suddenly that it was not his doubt at all. It was merely what he had feared to hear from others. And, in that moment, he knew his own mind.

"There is such a death," he said quietly.

Telling the story to Hogan in words had helped—helped to crystallize his thoughts, to bring back clearly the reasoning he had used. "Nothing else can explain what happened," he added with conviction.

Dan Hogan leaped to his feet, and began pacing the floor, waving his arms widely. "Man alive! I believe you. I'd take your word for anything. If you say there's a mysterious Death around here—well, there is, as far as I'm concerned..." He stopped; faced Jules; and began spacing his words slowly. "But it's not me I'm thinking about. Right now, I'm thinking about juries..."

When Jules failed to answer, he went on more quickly: "And I'm thinking about the District Attorney, Matthews. He's a coming young fellow—and mighty nasty. Out for convictions. Hates me; and he's dead against your kind—everything you represent. 'Friend of the people'—Matthews... In his work! You know the kind...

"Good Lord, man!"—Hogan resumed his pacing—"as it stands now, you've got no case! Fifty people saw you shoot that man. If you're going to justify it in court, you've got to have proofs—proofs of what you've just been telling me... Damned good proofs! And," he added, raising his hands, palms upward, in an exasperated gesture, "as far as I can see, you've done your best to wipe out every proof you had... Getting Gibbs to burn 'em—and bury 'em...!" Suddenly he came to a halt beside one corner of the desk, and struck it heavily with his fist. His face cleared.

"Jules—there's only one thing to do. That body's gotta be dug up!... Gibbs had no right to bury it so soon, anyhow. It'll be easy..."

Jules half rose from his chair, and held up one hand in an arresting gesture.

"Dan," he said earnestly, "there is only one thing I am going to ask you to do. You must use all your influence to prevent that."

Gaping at the other, Hogan lowered himself slowly into his chair. "You mean," he said at length, "you're afraid you're wrong...? But you said—"

"I know I am right," Jules cut in crisply. "There's the point." His speech, now, was quick and business-like. The lines in his face had smoothed, leaving it calm.

"Dan, you've listened to me; and you haven't understood a word I've said. I tell you there is a deadly enemy to mankind—to all life. You say, 'Yes,' absent-mindedly; and immediately propose letting it loose! Why, in one stroke you would nullify every effort I have made!"

Hogan was red in the face. "But, man alive—don't you see it? You're in a hole! They can send you to prison for twenty years—for life!..."

"... And to prevent that you would risk thousands and thousands of lives," interposed Jules quickly. "Is that it?"

HOGAN threw himself back in his chair, and shrugged his heavy shoulders. "Oh come, Jules—it can't be as bad as that! The thing can be handled..."

"Handled?" Jules raised his eyebrows questioningly. "How?... I don't know—do you?"

"Well," hesitated the big man, suddenly at a loss, "if you don't, I guess I wouldn't..."

"Do you suppose I would have shot a man, Dan, if the thing could have been 'handled'?"

Hogan made no answer.

"If that coffin were opened," went on Jules, "the man that examined the body would most surely die. Whoever cared for him in his sickness would also die. And so it would spread. When people at last realized they could not fight this new death, it would be too late. Too late to isolate it—too late to confine it. And—"

"Jules, you're only guessing!" snapped Hogan. His jaw was set stubbornly. His eyes were narrowed to slits. "All that stuff might happen, you say. You can't be sure. But I say to you—and I am sure—that you're sunk, if you can't prove your case!"

"And the very proof you want to find is the disaster I have been trying to avoid!" added Jules, smiling faintly.

"Hell!" Hogan snorted. "All right, if they won't believe you, let 'em suffer a little bit..."

"You don't know what you're saying!"

"People can deal with diseases. You know that, Jules."

"The thing Dixon let out of that meteorite is not a disease," said Jules quietly. "A disease comes from a species of terrestrial life. Diseases are parts of the world we live in; and through countless ages of adaptation and development we have acquired means of protection against them. We carry around special poisons in our systems for that very purpose...

"Do you realize what it means to live in this world of ours? It means being part of a tremendous but carefully balanced organization, every individual part of which occupies the position and the power it has been given as the result of millions of years of evolutionary adjustment.

"Of course we can deal with diseases! Any species which could not has long ago disappeared from the face of the earth. We? We are the Fittest—the Immune—Nature has selected the Immune by the simple process of killing off everything else. Nature is cruel...

"And so we have our organization: the integrated system of surviving species—each existing by sufferance of all the rest, and of the external conditions of matter which govern and determine all. It is a delicately balanced thing; yet on its continuance depends your life and mine, and that of every other living thing..."

Hogan was shifting about restlessly. It was clear that he believed time was being wasted. Before he could find words of protest, however, Jules was again speaking, very earnestly now.

"Now! From a far-off star—from a foreign and very different world—there comes a New Life. Through a strange mischance it is caused to become active here; and, miraculously, it discovers there is food. It grows.

"The picture is changed. The delicate balance of our living world is destroyed. The New Life is strong; it must be given a place. A tremendous reorganization is inevitable. Every species must be altered to fit the new conditions. New forms must be developed; old forms must surely perish. Nature is cruel...

"The Immune are no longer immune. The old order comes crashing down. And you—and I—are no more than outmoded forms, condemned to death..."

Jules ceased speaking, and for a time there was silence in the room. Hogan was licking his lips nervously, and gazing at Jules with a steady, exasperated frown. At last, he found words.

"Jules, that all sounds very great and very terrible; but"—he threw his arms quickly up and apart—"it's in the air! It's theory!... You've made me feel creepy, I'll admit—but it's not real. It's too remote... I can't let it affect me. My job is a very real one—to save you. And I'm going about it in my own way."

"Dan," said Jules quietly, "I'm sorry I haven't convinced you. I wanted you on my side. To me, the thing is very real... I believe that there is a New Life on earth. My aim has been to destroy it—throttle it—before it had a chance. With fire I have tried—as Humboldt did—to destroy its food, and thus kill it. I have tried to confine its last remaining vestige forever, behind lead walls. It may conquer the fire; it may pierce the lead; I do not know... But that coffin must never be opened! You must promise me that. Otherwise, I will plead guilty to the murder without further delay."

DAN HOGAN got up, came and stood over Jules.

"Jules," he said softly, "if there's one thing I like about you more than another, it's the way you stick to your guns. You had an ace in the hole there that I wasn't looking for—and you win..."

Jules stood up; and they shook hands. Hogan sighed.

"Yes, I'm with you," he said heavily, "but I hope you change your mind. You're in a tough spot. You've got no defense to speak of. And the people are going to be against you. People're always against anything they can't understand—damn 'em!"

IN the following days, Hogan's prediction was more than borne out. The New York newspapers—particularly the more sensational ones—seized avidly upon the O'Brien killing, and made of it daily front-page material. The fact that the victim was a policeman, the distinguished character of the murderer, and the public and brutal manner of the slaying made the story important from the very beginning.

When Herbert Jules, at first, refused to offer any reasons or excuses for his actions, interest and curiosity increased tremendously, and public indignation was born. But when Jules, on the third day, did attempt to explain his motives, the incredulity and antagonism of press and public reached a peak. Only the Times, in its conservative way, suggested that judgment be suspended; pointing to Jules' hitherto blameless behavior and many valuable scientific achievements, and heartily deplored the whole business.

The other papers showed not the slightest inclination to suspend judgment. In trying to explain his theory to a group of reporters Dr. Jules had used the word "rays," picturing the New Life as a species of penetrating, invisible radiation shooting out in all directions from its source of food and infecting any living substance in its path. Adding an ironic adjective of their own, the newspapers pounced joyfully upon this word; and used it with devastating effect.

"TERRIBLE RAYS WOULD DESTROY WORLD, SAYS JULES," was a favorite headline; and "Claims O'Brien Was Broadcasting Death" or "Says Victim Was Menace to All Life" usually followed. Here was a new kind of alibi, and they made the most of it. The majority dubbed Jules a charlatan; the more charitable called him mad.

Gibbs, who had kept faith with Jules, obeying his instructions to the letter, came in for his share of abuse. The cottage which he caused to be burned had been rented to O'Brien, it proved; and the indignant owner immediately filed suit against the State for damages incurred. Furthermore, his summary disposal of the body of the murdered man—which he had coffined and interred on the very day of death—earned him a sharp rebuke from the Attorney General in Albany, who termed it "irregular procedure" and demanded immediate explanations.

Little Gibbs stood his ground firmly; but the only "explanations" he could offer rested on the theories of the universally discredited Jules, and he thus found himself in an indefensible position. The newspapers attacked him vigorously with such epithets as "over-credulous" and "incompetent"; and he quickly perceived that his tenure of office, both as Coroner and as Health Officer, must necessarily be short. Even the ardent championship of Sheriff Dan Hogan availed him little, and did more to hurt Hogan than to help Gibbs.

In the meantime, Peyton Matthews, District Attorney, watched developments with considerable satisfaction, anticipating an easy conviction with a good deal of pleasant notoriety attached. His only concern was to fight any and all delays which Jules' lawyer might propose, so that he might bring the case to a head while popular sentiment was so strongly in his favor.

As for Jules' lawyer, he found that his only stock in trade was delay, since there was no case for the defense. He was a very discouraged man. His client appeared to take not the slightest interest in his own welfare.

These, then, were the sensational and widely-heralded developments of the week following the killing of O'Brien; but the most important development of all went along very quietly and unobtrusively. It was observed, in fact, by only one man.

THIS was a Great Neck postman. For a score of years his route had lain along Soundview Avenue. He knew every inch of the way, and took a sort of proprietary interest in his surroundings. The burning of the Dixon house—where he had delivered mail for so long—was a great sorrow to him. He found it hard to adjust himself to the change.

Absent-mindedly, he would turn in there; and sometimes get half-way up the walk before raising his eyes to the ruins and realizing his mistake. On one of these occasions, just as he was about to turn back, there came over him suddenly a strange, vague feeling that something was wrong. Puzzled, he gazed for a time at the black hole where the house had been—at the charred ground around it. Then, shaking his head, he went away. But on the following day he stood in the same place, scratching his head and knitting his brows uneasily. For some reason, the place seemed to look worse—the scene to grow drearier—every day. For three more days this impression annoyed him, until, of a sudden, he knew what caused it. The burnt part was bigger! in fact, it seemed to be spreading all over the place!

Now that he saw, he wondered how he could possibly have missed it before. Why, half the lawn was black! At first, it had only been burnt about twenty feet out from the house. He remembered that clearly; yet now, as he stood on the walk, the black part was almost up to him. He backed away, instinctively disliking that black grass; and seeing a friend, the gardener next door, hailed him. The gardener was as astonished by the phenomenon as the postman; and his trained eye caught further strange details.

"Look at that bush—and—Lord—the tree!" he exclaimed.

The thing at which he pointed was hardly recognizable as a bush. It was rather the thin, black skeleton of a bush. The branches were bare; the little stems held no leaves. Beneath it, on the ground, was a circle of black powder or dust. And the tree was even more strikingly peculiar in appearance. It stood near the center of the lawn. Its upper half was perfectly normal.

Green leaves moved and rustled in the light breeze. But its lower half was merely the black skeleton of a tree. The trunk and branches looked thin and wasted. As they watched, a blackened leaf detached itself from its stem, struck a branch, and dispersed in the form of sooty powder floating in the air. And on the ground was a small, dark, feathered object, which they saw was a dead bird.

"Well, what'd'yu think of that?" said the gardener.

Within half an hour a small crowd had collected around the two original observers, and all agreed that "there was something mighty queer about it." A policeman was attracted who, having looked, went away; and, in due course of official procedure, Sheriff Dan Hogan came to know of it. As a result, there was a cordon of policemen around the lawn that night; and on the following morning four steam-shovels and an army of workmen were wreaking havoc on neighboring property, clearing a wide circle of bare earth.

For, as Herbert Jules worriedly explained to Dan Hogan and to Gibbs, it was clear that fire had not conquered the "rays."

"As far as we know, they feed on organic matter only," he went on. "Fire does not completely destroy organic matter. Therefore, it must be cleared away. Fortunately Long Island soil is sandy, and the thin top layer of vegetable matter can be easily removed. A cleared strip around the place should act as a barrier to the rays. We do not know how far they can travel unaided by food, but I do not believe it could possibly be more than a few yards...

"Of course the cottage out at Port Washington presents the same problem."

Jules was wrong there, however. The Port Washington problem proved to be an entirely different one—and that was really the fault of Gibbs.

On the day when, with the help of the local fire department, he had burnt the cottage, he had been at a loss to know what to do with O'Brien's hens. They had appeared perfectly healthy—all except two—and it had seemed to him unnecessarily cruel to kill them. Separated from the cottage by a narrow strip of woods was a small group of four houses, most of the occupants of which had quickly been attracted to the scene of Gibbs' activities. At his offer, they had gladly accepted the homeless fowls.

But almost from the first the birds had been sickly. The new owners thought little of it, blaming nostalgia and improper diet. Even when a number of their own group began to suffer "dizzy spells" and an unpleasant burning sensation of the skin there was no suspicion of anything wrong. Gibbs had been very careless.

The five children of the little community played in the woods back of the houses; the wives doctored and fed the hens; and the husbands came home every night, sympathetic but not particularly worried over such reports as "Mary is not feeling well this evening. I have sent her to bed," or "Papa, Mama's got a headache. Let's us get supper!"

When Sunday came, however, and they all stayed home, they began to notice things. Those hens were hopeless! They couldn't even stand up, now; but lay around clucking feebly and shedding their feathers, which were of a strange, muddy appearance and very sparse. The grass around the houses had a peculiar greyish look which they had never observed before. And someone was sick in every house...

ON Monday morning the men did not go to work; but held a consultation, and quickly agreed that something was very wrong. There could be no doubt about it, now. The grass was black, not grey—all around; and the woods in back of the houses, in the direction of the burned cottage, presented an unnatural sight. Trunks and branches, shorn of their leaves, stood inky dark against the sky. Most of the small bushes and underbrush had disappeared, and an ebon carpet of dust covered the ground. The men suddenly remembered O'Brien's cottage and the strange happenings there. They became frightened.

And that was the very morning of the arrival of Dan Hogan's advance guard of policemen...

"There will have to be a quarantine."

Herbert Jules and Dan Hogan accepted Gibbs' statement with slow nods; and for a time there was silence in Hogan's office, while the three men remained occupied with their own thoughts.

Finally, Jules asked: "What is the penalty for breaking quarantine?"

Hogan's answer came quickly, as if he had been expecting the question. "It's a misdemeanor. Fine or imprisonment."

Little Gibbs looked distressed. "It doesn't seem to fit—does it?"

Hogan amplified the thought. "A fine doesn't mean much to a man whose life is at stake—along with the lives of his wife and children. As for imprisonment: how're you going to imprison people you can't go near?" He stood up, and began pacing about angrily. "As it stands now, they could walk out of that place, and we couldn't lift a finger!"

"Do you think they will?" ventured Gibbs.

Hogan stopped near Gibbs. "Well—put yourself in their place! If your wife was sick—suffering, and you phoned a doctor; and there was a line of cops all around your house that wouldn't let the doctor in, tellin' him it was sure death—would you just sit there, waiting to die?"

Gibbs buried his face in his hands.

"Dan," said Herbert Jules tensely, "if I could get out—if I could only get to my laboratory, there is a chance I might be able to do something for them..."

In two strides Hogan was at his desk, giving a number into the phone. A short pause, and then: "Hello—Matthews? This is Dan Hogan... Yes... Can you step down to my office a minute?... Yes, of course it's important!... O.K." He hung up. "Best to see him first," he explained.

Peyton Matthews was a spare young man with a high, narrow head, dark complexion, and sleek black hair. He had close-set, black eyes; a long, hooked nose; and a small, tight, straight-lipped mouth. His face was habitually expressionless; and he affected a thin, meaningless smile, with which he now favored the company as he stood in the doorway.

"The prisoner, it would seem, spends most of his time in this office," he remarked in an even, colorless tone.

Jules flushed slightly, and Hogan growled, "Sit down, Matthews."

The District Attorney strolled to a chair, and seated himself comfortably, crossing one leg over the other.

Hogan stood in the middle of the room, legs wide apart, hands deep in trousers pockets; and looked at the other. "Matthews, we want to fix it so Dr. Jules can go home."

Peyton Matthews raised his eyebrows. "Oh?"

Herbert Jules leaned forward in his chair, and spoke very earnestly. "Mr. Matthews, I hope you will help me. I would not ask favors for myself, but—"

Jules paused for a moment, as if searching for words. The lines of care were deep, in his forehead and about his eyes. When he continued, his voice was very low.

"Out on Manhasset Neck, twelve people are dying slowly. They are being killed by a mysterious force—a force new to this world—a thing no one can perceive or understand...

"I want to study that force. If I could work in my laboratory I might be able to discover some means of combatting it. The chance is very small, I will admit; but it is unthinkable that we should not try everything possible to save them!"

Peyton Matthews was not looking at Jules, but at Gibbs; and now he said, "I hear you have quarantined those people, Gibbs."

Jules held his tense position. Hogan frowned thunderously.

"Why, yes!" said Gibbs in surprise.

"And I am told, also, that you are refusing them medical attention," pursued Matthews calmly.

"Well you see, Mr. Matthews," said Gibbs earnestly, "there's nothing a doctor can do. He would just be committing suicide by going in there, because we couldn't let him out again. He would spread the—the rays..."

MATTHEWS was staring at Gibbs fixedly. "It's a queer sort of quarantine, and I doubt very much if it is legal," he said coldly. "I don't like to tell another man his business; but you know, Gibbs, there's been a good deal of criticism of your actions lately. In fact,"—here Matthews turned from the miserable Gibbs, and included the others in his gaze—"a number of strange things have been done in the name of these—ah, 'rays' that Dr. Jules seems so fond of."

"Now look here—" began Hogan, but the other had not finished.

"One minute!" he said coolly. "The quarantine Dr. Gibbs has seen fit to declare is a brutal bluff. Those people cannot legally be confined to their homes without medical attention; and they should be told as much. If they are really sick, the course you are taking is no less than murderous..."

"Well, if holding them in there is murder, letting 'em out would be massacre!" exploded Dan Hogan. He was very angry.

"Speaking of massacres," said Peyton Matthews calmly, "I understand you have petitioned the Governor to establish martial law in this county."

Hogan was taken aback at this unsuspected knowledge of the other, but he spoke defiantly: "Well, what of it?"

"Nothing—except that I think I see your motive. In case your bluff fails, you would like to be able to enforce your so-called 'quarantine' with firearms. Is that it?"

Before Hogan could find an answer, there came an interruption.

"Mr. Matthews!"

All turned towards Jules, the sharpness of his tone impelling their attention. He was sitting back in his chair, apparently comfortable and relaxed; but his brows were lowered, his jaw hard, and his eyes very steady as he gazed at the District Attorney.

"Mr. Matthews, you appear to be unable to grasp the situation in any of its essentials. You seem incapable of understanding men with simple, honest motives. I am going to try to make the thing clear to you. I hope you have something approaching average intelligence." For a moment, Jules paused. Peyton Matthews flushed darkly, but said nothing. Noiselessly, Dan Hogan found a chair, and sat down on its very edge, grinning. Gibbs gaped.

"I trust, to begin with," went on Jules slowly, "that you do not really believe that these men, whom you have been criticizing so freely, are brutally or murderously inclined... I think it is safe to assume that the quality of human kindness is as highly developed in them as in yourself. All of us, as civilized beings, set a high value on human life. But emergencies arise...

"Suppose you were given your choice: whether one man should die—or a thousand. Would it be difficult?

"I say that emergencies arise. War is a common example. In warfare, life is held very cheaply; because the welfare of the individual is weighed against that of the group—and suffers in the balance. But war is man's own folly, and not the sort of emergency I am talking about.

"It sometimes happens, however, that such a choice as I have mentioned is forced upon us from outside. Then it must be decided: the one?—or the thousand? The difficulty lies not in the choosing but in the apprehension of the choice; that is, in the grasp of the situation. Fools kill the thousand in futile attempts to save the doomed one.

"Near Port Washington are twelve people who carry in their bodies a destructive agent so virulent as to be a menace to the whole of mankind. Since no one understands it, it cannot be fought; it must be confined—isolated; and if that fails—there will follow a disaster such as the civilized world has never known!

"To prevent that, I killed a man. He had no chance for life—irrespective of my interference; the infection he carried doomed him to death. But left to his own devices he would have taken many others with him...

"And to prevent that, Hogan here should have authority to kill those twelve, if there is no other way to stop them from spreading the destruction that they carry."

When Jules finished, Matthews spoke almost immediately. "It strikes me, Jules, that you are a little too vague about this thing that makes you do and advocate such violent deeds. You call it a 'destructive agent' or a 'force' or an 'infection.' You admit you don't understand it—know nothing about it. And yet you are willing to kill people on the strength of it. That is unreasonable."

He stood up, glancing at his watch. "Now I must go. I have no more time to spare." In the doorway he turned. "As to your being released, Jules; that is impossible, of course. Now you are a confessed murderer; and it would be my duty to make every effort to prevent such a mistake being made."

With a slight nod to the others, Peyton Matthews was gone.

JULES was, therefore, returned to his cell: and he saw no one until the following evening, when he was again summoned to Dan Hogan's office.

The big man was hardly recognizable. He sat at his desk, his head supported in his cupped palms, his shoulders bowed forward, his body slumped down in his chair. When he looked up, Jules was shocked by his haggard face.

"I hope to God I never spend another day like this one!" he groaned. "Lord knows what's going to happen now!"

"What has happened, Dan?"

"I may as well tell you from the beginning...

"About noon, I went out to Port Washington. I'd been waiting around all morning to get word from the Governor; but it didn't come, and I decided to go out there anyway. I arranged to get the news by phone. There's a police booth near the place.

"The four houses where those people live are in a sort of a little valley, set close together, with a road leading down. It's an awful-looking place. It's black—just black. The fields are black, where the grass used to be; and the woods behind are black—what's left of them. There isn't much left, though. The trunks are about all. All afternoon I saw branches falling off. You can see right through to where O'Brien's cottage was.

"I checked up on the guard. We got a line of men all the way around—almost two hundred. About a quarter of a mile away the steam-shovels are working.

"You could see some of the people down there, outside the houses—a few men, and once in a while a woman. They were just sort of walking around looking at us, not doing anything.

"Gibbs was there—been there all day. He said they hadn't been giving much trouble; but he looked all broken up when he said it, or even when he mentioned them, or just looked down there. He said there'd been three doctors in the morning—doctors that the people had phoned; but he'd managed to show 'em it wasn't any use, and sent 'em away. They were stubborn though, he said.

"About an hour after I got there, a woman started screaming—in one of the houses. It was awful. She didn't stop at all; just screamed and cried, and screamed again. I could hardly stand it, and Gibbs was worse. He kept sort of wincing, all the time—every time he heard it.

"Pretty soon, then, one of the men came running towards us. When he was about ten feet away I had to tell him to stop; and he just stood there, and looked at me, and said, 'Please, sir, can't we have a doctor?'

"Well, Jules, maybe you can imagine a little bit how I felt. I didn't know what to say; but there was one word I just couldn't say, and that was 'No.' I said, 'In a while. You will have to be patient.'

"I think he knew I was lying, because he screamed out at me: 'In a while—damn you! Don't you know my wife is suffering? She's dying!' And then he cursed me and called me every name he could think of; and I just stood there, until he quit and began sobbing. He was sick, too; you could see that. He shook all the time, and he had black marks all over his hands and face.

"In a little while he quieted down; and then—all of a sudden—he looked straight at me, and began walking forward!

"It was a queer feeling, Jules—seeing him coming closer like that, with his black face, and eyes staring at me. First I ordered the man back, and then I backed away from him, too. When he saw that, he stopped; and I could see he was thinking. Then he turned around, and went down towards the house. But in less than fifteen minutes he was back again with three more men. And I knew they meant to come through. I told them to stop; but the man who'd been up before said that they were going after a doctor, and to try and stop them. They looked determined and desperate, and I could tell by their eyes how they hated us.

"Well there wasn't anything for me to do. You can't stop people if you can't shoot 'em and can't get near 'em. I couldn't ask my men to commit suicide, so I had to tell 'em to back up. So there I was, letting them go, and couldn't think of anything to do about it.

"Well, Gibbs showed me. He'd been standing beside me all the time I'd been there, not saying a word. Now—all of a sudden—he said, 'Wait! I'm a doctor. I'll go with you,' and he went over to his car and got his medicine kit. I caught him on the way back, and told him he was crazy. He just said, 'I can't stand it, Dan—I can't stand it!' and went towards the four men who were watching him sort of uncertain-like. I grabbed his sleeve.

"He turned around, and his face was set hard as a rock. He said, 'You can't stop me, Dan.' Then he smiled. 'I happen to know that—you see,' he said.

"So he went down the hill with the four men and into one of the houses. Pretty soon the woman stopped screaming.

"Well, a couple of hours went by, and every minute I was expecting the word from Albany, but it didn't come. Everything was quiet down around the houses, though; and I began to get a bit less worried. It's funny, but I couldn't seem to think much about Gibbs. Then—all of a sudden—they all began to pile out of the houses, some being carried. I couldn't figure it out at all; but I've found out since what happened. It was Matthews. He called them up, and told them there wasn't any reason why they couldn't go to a hospital for proper medical attention, if they needed it.

"I began to see that the game was up. There were three cars on the road outside the houses, and they were piling into those. I began to wonder about Gibbs, and all of a sudden I saw him. He was coming out of one of the houses, and he had a gun in his hand. I don't know where he got it.

"When the people saw him, they stayed where they were, not moving. Gibbs stayed still, too; and for a long time they all looked just like statues, without a single movement. I knew Gibbs was hoping I would get the word from Albany; and I prayed for it, too, like I have never prayed for anything in my life. But it didn't come.

"Then one of the men jumped at Gibbs, and grabbed him. He didn't even shoot. They all piled on him.

"Pretty soon the three cars came barging up the hill and past us. I sent men to follow them. I guess they went to a hospital. I oughta get a report any minute now.

"It was getting dark by that time, especially in that black hole of a valley. A drearier place I have never known. I could just barely see Gibbs, lying on the road down there. He looked awfully small and lonely. Somehow I didn't seem to realize until then that he wasn't coming out again..."

HOGAN fell silent. On Jules' face distress and horror contended. Neither spoke for some time. Then Hogan, who sat with bowed head, clenching and unclenching his fists, burst out passionately: "It wouldn't seem so tough if he'd done any good! But no. Those damn' fools in Albany don't do anything; they don't pay any attention... I tell you, Jules, they're just as responsible for little Gibbs' death as if they'd choked him with their hands!"

Jules nodded. "And yet, Dan," he said sadly, "that is the way it always happens. Whenever some sudden catastrophe—some new and unexampled menace—strikes at mankind, official action is too slow—and it is some individual that must bear the brunt of the attack. No system can act quickly in an emergency—because systems are built to deal with ordinary situations. They are sluggish; they cannot change their nature overnight. And so, in times of new and sudden danger, it is brave, unselfish men like Gibbs who throw away their lives to save their fellows..."

"But it didn't do any good!" groaned Hogan.

"I think you're wrong," said Jules quickly. "True, he failed in his immediate purpose; but his martyrdom is certain to have a tremendous effect on public opinion, and should go a long way towards compelling official action. Now the thing is out of control. Now, if ever, action must be taken. And I know what I am going to do. If it is humanly possible, I am going to find out what these rays are, and how they may be fought... But first I must get free."

Hogan shook his head disconsolately. "I don't see how it's possible, Jules. I've done everything I can, and—"

"I have a plan," Herbert Jules interrupted, "and it will need your help. It should work, I think..."

AND on the following morning they stood before Judge Wilkerson in the County Court—Jules, Hogan, Jules' lawyer—a large, florid, white-haired man, and Peyton Matthews. Hogan and Matthews stood a little bit to one side. Hogan shifted nervously from one foot to the other—obviously unhappy. He was far from approving Jules' plan, which the latter had outlined to him on the previous night. Vigorously he had objected that no cause could be worth such a sacrifice; but Jules, by a single reference to the death of Gibbs, had managed to make that objection appear ridiculous. Hogan had been forced reluctantly to do his part. He had held a long conversation with Judge Wilkerson, and the present special hearing was the result.

Nor was Peyton Matthews in a comfortable frame of mind. He was puzzled; not knowing what to expect. This move had taken him entirely by surprise; and to be taken by surprise annoyed Peyton Matthews extremely.

Judge Wilkerson was speaking, formally.

"Herbert Jules, on the fifth of this month, in this Court, before me, you were charged with Second Degree Murder in the killing of Patrick O'Brien. At that time you entered a plea of Not Guilty. I am given to understand that now you wish to alter that plea. Is that true?"

"That is true," agreed Jules calmly.

Matthews looked hard at him, a slight puzzled frown creasing his forehead.

"I wish to plead Guilty to the charge," said Jules. Matthews was surprised into betraying real astonishment on his usually impassive features. He started slightly, and stared hard at the Judge, who was again speaking.

Hogan cleared his throat, and leaned forward toward the Judge.

"And I, your honor, would like to take the prisoner into my personal custody, on sufficient bail of course."

The Judge nodded and addressed Jules. "You will be allowed to go free in the custody of Sheriff Hogan, when you have posted the sum of fifty thousand dollars with this Court."

From an inner pocket Jules' lawyer took a package of bills, and laid them on the bench. Jules bowed to the Judge, and turned away. Expelling his breath in a long and audible sigh, Hogan joined him.

"Your Honor!" All turned to see Peyton Matthews standing before the bench, one arm outstretched, his face flushed. His original suspicion, which had been changed to satisfaction by the Judge's verdict now returned in full force, together with considerable indignation.

"Your Honor, I protest that this is irregular! There is no reason why bail should be admitted. In a case so serious, bail should not be—"

"Objection overruled," said the Judge coldly.

JULES' car was waiting. He went directly to his home, a large mansion overlooking Long Island Sound in the residential village of King's Point, three miles north of Great Neck. There, from his great laboratory, he secured a small but massive lead box, of the type used to store radium solutions. Equipped also with a pair of fire tongs and still accompanied by Hogan, he returned to Great Neck. The Dixon grounds were now no more than a great black disc, an eighth of a mile in diameter, with a circumference of cleared earth, outside of which was posted a constant guard of policemen. Running at top speed, Jules crossed the sooty ground to the tree, under which lay the little black lump that had been a bird. This he deposited in his box, using the tongs; and then returned with all possible speed to safety.

Back in his laboratory, he immediately began work—using electroscopes, phosphorescent plates, and various saturated solutions, in an attempt to determine the nature of the destructive force which he knew emanated from the infected material. He realized that he was in great personal danger; and used heavy lead shields, arranging them in such a way that there was never any direct line between a part of his body and the thing he was studying. He knew of no other precaution to take; but this one alone made his operations discouragingly difficult and cumbersome.

The newspaper reports of Jules' temporary release aroused widely varying reactions because of the many divergent attitudes and opinions which the public now held towards the matter of the rays. Gibbs' and Hogan's quarantine had earned them almost universal condemnation at its inception; but, at the news of its failure, popular opinion did an about-face, and they were blamed for laxity. As Jules had anticipated, Gibbs' martyrdom was instrumental in convincing many that the matter really was serious; and the fact that the 'ray victims,' as they now were called, were at large caused a faint but very definite uneasiness.

The fortunes of these 'ray victims,' therefore, became a subject for headlines and lead articles. The attention of the public was focused upon them.

They had all gone together to a large hospital in Jamaica, where the hospital authorities gave them a special ward to themselves. It was planned that their nurses and doctors should—as it was expressed in a statement given out to the reporters who besieged the place—"take stringent antiseptic precautions."

These precautions, however, proved to be quite useless. Within two days one of the nurses was taken sick; and the rest walked out in a body, refusing to have anything more to do with the case. With the inquisitive and efficient newspaper reporters ever present, it was impossible for the hospital authorities to keep this event secret, and it was common property almost as soon as it happened. No new nurses could be found who would even so much as enter the "special ward."

"JAMAICA HOSPITAL DEMORALIZED" was the way one headline-writer put it. It was not long before the majority of patients in the institution was hysterically demanding to be removed.