RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

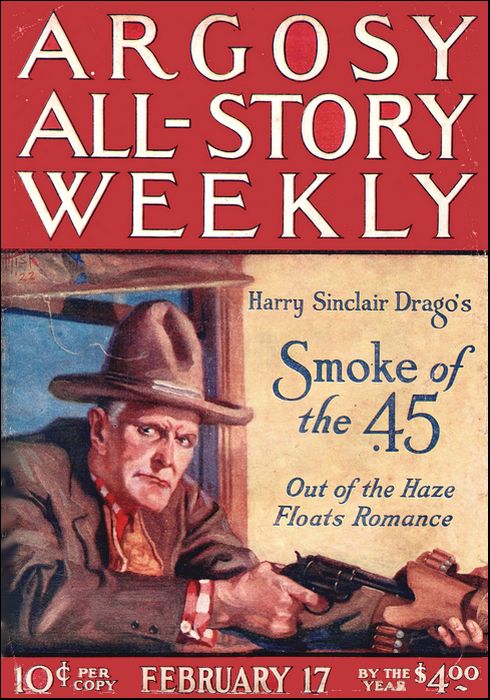

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 17 February 1923

"AND why," demanded Ty Foo earnestly, "do they call you the death man?"

"I can die," Lo Jin answered slowly, "if you but strike my head a small, angry blow."

Ty Foo looked at the man, wide eyed, incredulous. "How many times hast thou been dead from a small angry blow on thy skull? Speak, thou coolie liar. A word from me and your body will die among the sharks out there!"

Lo Jin was naked to his coolie loin-cloth, and in the tropic light that flared through the open windows of the gambling house, his attenuated figure seemed to suggest recent hardships and privations. He had arrived that morning in a famine-junk from Soo Loon. The junk had no cargo save a horde of food-crazy peasants from the Yalu River district. They had hoped, with the junk's captain, to help load dried bananas, oil, shark fin, and birds' nests from the vast storehouses of Fanuti Islands.

Ty Foo was the big comprador of the island group. He also owned the multiple gambling houses where pak-a-pau and fan-tan were played under the direction of his croupiers. Ty Foo was so wise and full of cunning that men said he could rule the Eastern money exchanges until the big banks sat up and cried for mercy.

Into his palatial gaming house had come this narrow-hipped, priest-faced boy coolie named Lo Jin, a mere skeleton from the multitude of famine-driven wretches who had sought the sunlands of the south in the hope of finding one fat meal a day. People came to Ty Foo with their sleeves full of thievish tricks—jugglers from Amoy and the Philippines, banyan tree experts with rope ladders to climb or fire to swallow. They made him weary. But here was a boy who could outshine and out-magic them all—he could die at will and deceive the medical experts! There were boundless possibilities in the idea!

"I have satisfied the hospital barbarians at Hongkong, O Great One. I have given trials in the operating theaters, and have received money for my exhibitions. But I am hungry and my people are poor!"

Ty Foo listened spellbound. Further questions elicited the fact that his young visitor had once occupied the position of a sacred dancer in the Buddha shrine of Shai-wai-Yat, at Soo Loon. The priests had discovered in him an aptitude for attaining that trance-like condition so often regarded in more civilized countries as the symbol of death. And until famine had swept the land they had profited by this semblance of death after each dance, together with his triumphant awakening, due to the invocations of the priests in the presence of wealthy devotees.

The voyage south, in the famine junk, with its horde of flesh-eating refugees, had visibly affected Lo Jin's comely exterior. And the gambling house lord was swift to appreciate the fact. Ty Foo, in spite of his snarling voice and his alleged wisdom in earthly matters, was a prey to all the inherent superstitions of the low-caste Cantonese.

"I will give you work," he declared in the sudden heat of his emotions. "One Mexican dollar a week and plenty rice. But you must keep alive until I give you the sign to be dead. Get that in your holy skull, Lo Jin!"

Lo Jin salaamed. "I will keep alive, O Great One, so that my strength may help enrich your house. But death will come to me when you nod but twice."

"Get a broom, then," grunted the business-like Ty Foo. "And make clean the dam floor of this hall. Make no dust or you will choke my dancing girls, asleep over there behind the screen."

Lo Jin found a whisk broom and a grass-silk coat which he pulled over his nakedness. Then he strewed tea leaves over the liquor-stained mats and carpets. Very skillfully he took up the litter of cigarette ends, matches, and other raffle left by the gamblers overnight.

Behind some lacquered screens and bead portières slept a group of Cantonese girl singers and players, whose business it was to beguile the weary interludes which frequently happened during the early part of the evening. Among these girl players was Hena Moy, of the Soo-Loon-Hakodate Variety Combination. Hena was in her eighteenth year; she was a soft-eyed, ivory-cheeked celestial maiden, who, on account of her advancing years, had been re-licensed and transferred from her Soo Loon headquarters to the beneficent guardianship of Mr. Ty Foo of Fanuti. Her indenture would last for another two years. By the end of that time her lips would have lost their cherry tint, her skin its beautiful golden tan which had earned for her the title of Saffron Lily.

During the long hot morning Hena Moy had been tossing on her mat, unable to sleep like the others. She had been thinking of her little brothers and sisters in far Soo Loon; of the dark-haired boy lover who had danced in the temple oi Shai-wai-Yat. This boy had promised to release her from her cruel indenture which made her the slave of the Soo-Loon-Hakodate Syndicate. Her father had forced her into the business, and for a whole year she had sung and played nightly in foreign geisha and tea houses.

The sound of Ty Foo's voice had stirred her curiosity only; it was the soft tones of Lo Jin that swept her from her sleeping mat, peering through the portière with a heart that came near to choking her.

Lo Jin was standing in the fierce sunlight near the open window, his slim figure and sunken eyes speaking eloquently of recent hardships. But his face had lost nothing of its celestial beauty, the curious esthetic pallor that marked all devotees within the ancient temple of Shai-wai-Yat. For a moment astonishment at his presence in the gambling house held her dry-lipped and unable to cry out. It was the rough touch of San Hayadi on her sleeve that recalled her to her surroundings.

"You are keeping us awake, Hena Moy," she whispered sadly. "Are you looking at a man or a goldfish?" she intoned with languid curiosity. She had lived a whole year in San Francisco, and her mysterious reference to goldfish was made with sympathy and understanding.

"I am looking at a man," Hena answered thoughtfully. "They come to these islands in those heavy junks like the starved puppies we used to see in the north. Ah! Hunger, hunger," she whispered softly, "I have seen you in the bare millet fields with the vultures. My poor people! How shall I meet you again?"

"Sleep," San Hayadi advised, drawing a cigarette from her pearl-incrusted case, "or smoke."

But the small zenana-like cubicle was too hot for sleep. Sprawling at all angles the other three members of the troupe slumbered fitfully. Once the afternoon had passed, there would be no more rest for them. With the lighting of the first lantern they would have to prepare for the entertainments that would last till dawn.

"I loved a boy in Osaka," San Hayadi bragged, "whose father is a member of our ancient nobility, a very noble samurai. You savvy that, Hena?"

"I have only loved a temple dancer," Hena sighed. "A boy of poor parents—so poor they could not feed their dear children. Some-day I shall help them!"

"You are a little fool, Hena! Always this talk of the fellow who danced and slept in a temple. The famine has got him, be sure of it. Give me the goldfish. My little samurai gets his seven meals a day, famine or no famine. I had a letter from him last mail. He has offered eight thousand dollars, Mexican, if Ty Foo will allow me to return to Nippon."

"You will go?" Hena questioned, her eyes still on the bead portière.

"Ty Foo will not let me. He says bis business go to ruin if he sells his girls. He is a pig and I have not smiled at him for a week!"

The clamor of a great port went up along the quay front, and through the ancient godowns of Fanuti. Flags and lantern junks, proas and rice boats jostled and thundered across the pandanus-skirted bay. The heat had died down outside. A soft wind from the Pacific nursed the drowsy-eyed town back to life, tightening slack muscles and brains for tie business of the coming night. Far away in the jungle-clad hills the praying flag of a Buddhist temple flaunted invitingly to the scattered Celestials in the villages and port.

The sleeping coolies of Ty Foo's gambling house became alert and anxious for work. Strange smells of food drifted in from the cooking fires of the compound, while the tinkle, tinkle, tum of stringed instruments indicated plainly that the dancing slaves were considering the program for the evening.

After dark the captains of the rice boats met within the punkah-fanned lounges of the notorious gaming hostel. White traders came also, sneakingly and under shelter of the unlit byways. They came for the entertainment that could not be obtained at the American and British clubs. In these far-removed backwaters of civilization, white men are known by their vices, the greatest of which may be the sin of living alone.

At eight o'clock, after the music had started within the beflagged recess, Ty Foo, waddled to his richly lacquered chair, where every table and settee came under direct observation. From his coign of vision he could detect any manipulations on the part of the crook or the sidesman.

The place filled rapidly. Fat Malay storekeepers and balloon-hipped Dutchmen gave greeting to prosperous Cingalee pearlers in from the Matawarra Banks. Ty Foo also welcomed them, while the mandolins and thiambles played the Hakodate jazz to the soft beating of sandaled feet.

At this moment there entered a globular-chested white man, hatless, but exquisitely dressed jn Shantung silk suiting and shirt. He came in by a door from the dark side of the street. The croupiers looked up like wolves on a scent as he slouched past and took his place at a table within a small palm-camouflaged recess near the orchestra.

Ty Foo watched him covertly until two Chinamen joined him in the recess, and proceeded to cover the table with cards, chips, and gold coins. The white man's name was Trones. He conducted an Oriental bank near the quayside. He lived alone at the bank and avoided the European clubs as though they were pest houses, confining himself to the society of Chinamen and Japs.

In spite of his aloofness, Trones's friendship was sought by all the white traders south of Macassar and Penang. But half a lifetime spent in the East had bestowed on him an Oriental genius for eluding unnecessary friendship. He conducted his bank on the principle that money needs no friends. Despite the negative side to this philosophy, Trones had managed to run a string of minor banks throughout the length of the Archipelago.

Ty Foo followed the movements of his play with more than usual interest. The two Chinamen opposed to him were members of a big pearling syndicate in Java. Suddenly Ty Foo beckoned to Lo Jin, standing in one of the recesses.

"Watch thou the three men in there," he grunted. "Take thy chemical mop and keep the floor about them clean. The white man, Trones, likes a clean floor."

Lo Jin obeyed with alacrity. Silently and deftly he plied his mop around the feet of the three players, returning as if by instinct to the side of Ty Foo.

"Now," the big Chinaman instructed in a low voice, "I want thee to catch my words, Lo Jin. In a little while work your mop back to the white man's table, and when he is deep in his calculation of the game, pull over the table with the mop. Do not touch the money when it rolls to the floor. Savvy?"

Lo Jin nodded, and the mop went back by degrees to the recess and the table that was now piled high with gold.

"I am sorry for your poor luck, gentlemen," Trones was saying in his high-pitched voice. "But you are playing with a man who will allow you every chance to recoup."

His fat hands were in the act of collecting the gold taels and paper currency into conventional piles, preparatory to stowing them away in the capacious pockets of his silk coat. The mop of Lo Jin had somehow obtruded between his feet and the legs of the table; and in extracting it the table received a violent jerk, capsizing it and spilling the gold and paper on the floor.

The fat, immobile features of Trones became suddenly transfigured. Lightning resentment and anger leaped in his eyes. His ponderous bulk heaved from the chair as he realized the cause of the mischief. His right fist smote the bowed, apologetic head of the quaking Lo Jin.

The blow was a heavy one, delivered with fury. "You meddlesome Chink! Take that and remember!"

Lo Jin seemed to reel away holding his head. He reached the center of the room, clutching spasmodically at a chair, then, with an inarticulate cry he pitched forward on his face.

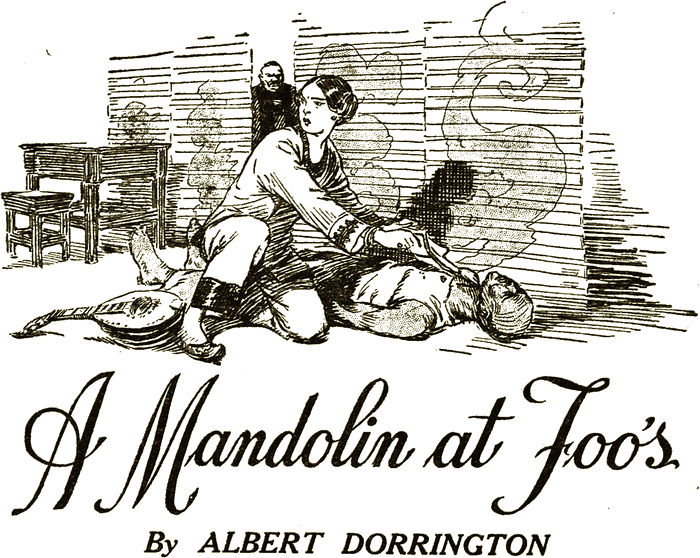

A sob of amazement came from the orchestra; a mandolin ceased playing. The ivory white face of Hena Moy peered out at the supine figure of Lo Jin, and withdrew hastily.

Ty Foo rose from his lacquered chair with a certain magisterial dignity, common to keepers of gaming houses and opium dives. He stood erect, his slanting glance focused on the prostrate boy. Then he signed to some waiting attendants.

"Pick him up," he said coldly. "Take him outside. He was very careless with the mop."

The coolie attendants carried Lo Jin to the cool veranda at the rear of the house. Ty Foo sat back in his chair with a dignified grunt of satisfaction.

Trones remained standing outside the recess, his hands moving rather foolishly in the vicinity of his pockets. His two Chinese partners had disappeared at the first breath of trouble. Trones stared at the gold coins on the floor, but made no effort to pick them up. His face had grown flabbier since the momentary flare-up. His jaw hung, quivering slightly.

He turned slowly and looked across the room. No one had moved from the tables, the episode having failed to attract the serious attention of the eager gamblers. Also the music had started again within the beflagged recess. A plaintive Hawaiian song, accompanied by the tender plucking'of mandolin strings, filled the silence.

Trones strode across the room heavily, his hands groping mechanically about his pockets. Near Ty Foo's chair he halted, to wipe his hot brow with a big blue silk kerchief.

"Is that kid of yours hurt, Foo?" he began with assumed carelessness. "Why in hell did he come fussing round my table?"

The big Chinaman shrugged and drew a nipa leaf about a seasoned suliu, preparatory to smoking it. His lips made no movement except to moisten the nipa leaf.

"I'm not a bad-tempered man," Trones went on in deadly earnest. "Perhaps I oughtn't to have socked the kid so hard. It's trying to one's patience having these boys raking about when there's a lot of stuff on the table. Is—is the beggar hurt?"

Again the Chinaman shrugged. "I bet you, Trone," he said gently, "a couple of cigars to nothin' that my man is dead!"

Trones recoiled half a pace, doubt and wonder in his eyes. In Fanuti the life of a coolie was worth no more than a hundred dollars, Mexican currency. But this fact did not minimize the flabby rush of panic that seized the white banker.

"He came heah in a famine ship out there!" Ty Foo waved a yellow fist in the direction of the quay. "Do not worry, Trone, do not worry!"

Trones had grown suddenly clammy; his thin silk coat appeared ludicrously overweighted with coin and sagged about his hot limbs like a damp sack.

"Let's go out and look at him," he suggested, his eyes wandering restlessly over the faces of the players at the near table. "I only touched him once, Foo. It wasn't a hard blow. Don't try to scare me, old party. A clout like that wouldn't hurt a rabbit."

A wisp of moon had risen in the southeast, casting a soft nimbus of light over the palm-sheltered veranda. On the bare floor lay Lo Jin, a crumpled, lifeless figure, head and face concealed in the shadows. Something rustled and moved in the darkness; Foo stepped forward and dragged a small resisting figure into the light.

"Ahe!" His breath came sharply. "Hena Moy! What do you want here?"

Hena Moy was trembling silently. The moonlight revealed tear stains on her cheeks. Her quiet sobbing aroused a sense of tragedy in the breast of Trones.

"I came to look," she quavered as one expecting a blow. "He does not move or speak. His heart is cold!"

Foo thrust her through the open door unceremoniously. "Go on with the music! " he commanded. "Hold your tongue to those girls. Go, go!"

Hena shrank back to her place in the beflagged recess, leaving the gambling-house proprietor alone with Trones.

The white man paced slowly up and down the veranda, hands thrust deep in his coat pockets. The Chinaman wagged his head in evident sympathy. "Why do you think about it so much, Trone? No good to worry."

Trones turned with features grown livid in their terror and apprehension. He thrust a shut fist in the Celestial's face.

"You yellow swine, you know why I worry! You could have killed that kid and the affair would have been hushed up. I'm different. Your infernal consul will be at me to-morrow, with the deputy police commissioner and a whole bunch of missionary society people—a whole swarm of meddling officials will drag out the kid's carcass."

Ty Foo laughed softly as he touched the boy's neck with his sandaled foot.

"You hit him velly hard, Trone," he murmured. "Boy plenty hungry. No waste rice on junks. Hi yah!" he concluded with a grunt of disgust. "I no likee such a thing my house. I flow body into bay," he suggested after a pause, and with a curious leer in the white man's direction. "Forgleet him, heh?"

Trones seemed on the point of exploding in his excess of rage and despair. Well enough he knew that all the bays and rivers in the South Seas could never hide the slim, lifeless form of the young temple dancer. The water police would fish it out, or the tides would wash it up. The result of such an event would be fatal to banker Trones.

The islands were full of live white men who would see in this episode an opportunity to punish him for his past incivilities and aloofness. They would never allow the killing of an unknown Celestial to pass without proper investigation. That in itself would expose him as a visitor to Chinese gaming houses. Also, it was one thing for a Chinaman to kill Chinaman; such deeds were common enough and never appeared to reflect on anybody; but the moment an influential white man had the ill luck to injure one fatally, innumerable Chinese guilds and tongs bleated like children for reprisals.

"Tell me," he said hoarsely, "who was that chit you found sprawling on his body?" The hairs of Trones's head and mustache seemed to bristle in his mental agony.

Foo merely grinned, and it was some time before he made answer.

"Me think she see this boy somewhere befoah. Maybe in China. She belong to Soo Loon, allee same place where junk come flom. She welly good singer and play well. She welly ni' lille gel."

A silence fell between the two, broken only by the plaintive strumming of the mandolins.

"Damn her!" Trones flung out at last. "There's always a woman about at a time like this!"

Foo was silent and thoughtful as he stared critically at the crouched up figure of Lo Jin. He stooped and touched the face with his hand. Then, breathing stertorous-ly, he knelt, pressing his ear against the boy's heart. He remained thus for several moments; then he rose and his face had the frozen look of one in the presence of a plague.

"Ta shan!" he cried with sudden ferocity. "Why did you strike so hard?"

The white man's knees quaked violently. The Chinaman's manner frightened him now. So long as Foo had remained confident he felt a certain security. But the big Celestial's tone had changed. He, too, seemed to realize the danger of their position.

Ty Foo spoke quickly and in a lowered voice. "I am in this, Trone, with you; savvy?"

The banker nodded dully; he was wondering how many people in the house had noticed him strike the mop boy.

"You see, Trone," Foo went on in his oily tones, "me an' you not welly good friends this long time."

Trones stared at him icily. "You are going back to that shipping deal, Foo. Forget it," he snapped.

A malicious gleam showed for a moment in the Chinaman's eyes. "Welly hard to fo'get one million dollar you squeeze flom me, Trone," he intimated sadly. "Allee welly you fo'get. Me never fo'get."

"It was a clean-cut squeeze, Foo. I forced you under threat of a bankruptcy, notice to sell the ships. I bought them That's all. You had to sell because I had you by the feet. You'd have done the same to me," he half protested. "Why squeal now?"

The big Chinaman sat on a palm tub and moistened another suliu. The throbbing of the mandolins inside seemed to intensify the sudden hostility which had leaped between the two. Foo's face was bent near the sprawling figure at his feet.

"One million dollars," he intoned. "Me wonder how much you give me back now," he added unexpectedly, "if I help save you 'bout dead boy?"

Trones whipped round with a suppressed oath, a sudden light of understanding in his eyes.

"You yellow skunk! Do you mean to hold me up on an accident of this sort?" he flung out, pointing to the huddled shape on the veranda floor.

The Chinaman filled the air with big gusts of smoke from his suliu.

"You give me back half," he responded without hesitation; "or I smalshe banks allee way flom here to Hongkong!"

Trones grew calmer at this barefaced threat. "You mean—" he began slowly and paused at the Chinaman's uplifted forefinger.

"Yes. This boy, Lo Jin, b'long to temple in Soo Loon, Shai-wai-Yat. Lo Jin big flavorite with allee priests an' Buddha men. If I send wire to China and say big bank manager, Mlister Trone, killee Lo Jin at Fanuti, they wire back say they will put boycott on allee banks b'longin' Mr. Trone. Savvy that?"

Trones was silent. The threat was no idle one. If the news went north that a white banker had killed a member of a sacred guild, the result would be that every Chinese trader and comprador, every trust and syndicate, down to the smallest coolie investor, would transfer their accounts from his bank without warning. Moreover, powerful influences might operate to squeeze him out of existence. The bulk of Trones's investments were incorporated in half a dozen Cantonese and South Manchurian syndicates, and the mere suggestion of a widespread boycott on his investments turned him cold. Therefore he clenched his hands and held back the torrent of abuse that rose to his lips.

"I thought you were a white man, Foo," he said with a feeble attempt at a joke. "This is a dog's game anyhow!"

"I am a Chinaman. You squeeze me on ships; I squeeze you now with this!" He kicked the inanimate boy with his foot.

The white man was again silent. In the turn of a breath he had made up his mind. "I pay, Foo, and the devil take you, only let's get out of this mess."

Ty Foo beamed. "I am your fliend, Trone. Me swear Lo Jin try to pickee your pocket, while you play card in my house. Me swear he hang about your chair allee time."

"Of course he hung about my chair," Trones agreed readily. "Can't you say he snapped a bundle of"—Trones paused and drew a long envelope from his breast pocket —"of these gold bonds," he continued, holding up a bundle of stamped securities for the Chinaman's inspection. "I brought them with me to play and pay, if need be. You never know how the game may go with Sam Lee and his brother. I like my collateral on the spot. And these gold bonds are negotiable, at sight, at any Chinese or Asiatic bank in the world. Five bonds of ten thousand dollars each!"

Foo blinked absently, nodding from time to time.

"You can swear," Trones whispered, "that he lifted them out of my pocket and tried to get away!"

A spasm of laughter crossed the Chinaman's face. "You must plove it," he chuckled. "You plove it."

"Proving things in this town is dead easy, Foo." Stooping over the prostrate boy, Trones slipped the five bonds into the inner pocket of his coat. "How's that, Foo?" he cried exultantly.

The Chinaman grunted approval, and was about to return to the house. A white-helmeted figure came into view from the long vista of palms that flanked the road leading to the rear of the gambling house. The helmet came nearer, with swift certain strides, and drew up at the gate leading to the compound.

Ty Foo smothered a soft Chinese oath.

"McLagan!" he breathed. "Waitee while, Trone. I go down gate an' speak to him."

The Chinaman stepped from the veran9a and walked slowly down the path, nodding his huge head in friendly salutation to the helmeted shape at the gate.

Trones breathed through his nostrils like a swimmer caught between tides. McLagan was deputy commissioner of police, and was on his nightly round.

MCLAGAN'S reputation as an administrator of the law was beyond reproach. It was known in the town that he had long ago marked Ty Foo's house for stricter surveillance than it had received in the past. Scarce knowing what he did, Trones followed the Chinaman down the path, but hesitated undecidedly as the deputy opened the gate and entered the precincts of the house. Ty Foo appeared to be explaining in his best pidgin the incident which had just occurred. Very slowly they joined the waiting Trones in the path.

"A bad business, Mr. Trones," the deputy declared. "I got the story over the phone a few minutes ago. These affairs soon leak out. We'll have a look at things, if you don't mind, Mr. Foo."

Sounds of merriment and dancing came from the house, but Foo's accustomed ear detected a missing note among the mandolins. Hena Moy was not playing! Unable to control his morbid apprehension, Trones pointed to the still figure of the boy on the veranda.

"I swear to you, McLagan, I only boxed his ears! I've often hit coolies and Arabs twice as hard for loitering about the bank. I wouldn't have raised a finger if he hadn't—"

"What?" the deputy asked coldly.

"Hung about my chair all the evening until I grew suspicious of his movements. There was a lot of gold on the table, and when he knocked it over I reckoned he was after the stuff. I lost my temper and gave him a clout."

"What else?" McLagan inquired, stooping low and examining the boy's face in the moonlight.

"Well, I discovered, just as you came to the gate, that I'd lost five gold bonds of ten thousand dollars each. Foo and I decided not to touch the body until we had reliable witnesses to corroborate the facts."

"You think he stole the honds?"

"I'm positive now. No one else in the room could have taken them."

"All right," nodded the deputy, kneeling beside the boy and passing his hands swiftly through the pockets of his coat. He had searched hundreds of defaulting coolies in his day, and the thinness of Lo Jin's attire made the task easy. He stood up, shaking his head with certainty and conviction.

"No gold bonds on this kid!" he jerked out. "You are mistaken, Mr. Trones."

Ty Foo's face was a study in contortions. He would have torn the coat from the boy's shoulders, only for McLagan's restraining hands.

"My word goes here, Mr. Foo!" the deputy rasped. He turned to the spellbound banker sarcastically. "Your statement is not borne out, sir. All the same," he added thoughtfully, "I do not think a man in your position has anything to gain by killing a boy of this class. Don't talk any more. There will be the usual inquest here to-morrow, midday. I wish you good night."

With a casual glance through the window of the gambling house, and a swift mental note of the occupants at the tables, he passed from the veranda to the road.

"My God!" Trones burst forth. "What do you make of that, Foo? Where are those damned bonds?"

The Chinaman collapsed into a chair, mopping his hot face with the sleeve of his coat. "Shut up!" he quavered. "I die, too, now, if you speakee one moah word!"

For the first time in his life Ty Foo felt that an unseen hand was beating him at his own game. The gold bonds had vanished. Trones had not touched the body, of that he was certain, or why would he have assured Mr. McLagan that they were in Lo Jin's possession? The problem touched him like white steel. His anger burned like a hidden flame now. The dead boy in the palm shadow was working with an accomplice, and that accomplice was close at hand.

He turned with a sullen gesture to the distracted banker.

"Go home," he advised. "We have been fooled. But I will find out the truth an' tellee you. Go!"

Trones could do nothing by remaining. He must trust Ty Foo to trap any accomplice in the ghastly tangle.

After he had gone, Ty Foo stirred himself to thought. Was the boy really dead, he asked himself, or was he merely playing a part which he had assigned himself?

Lo Jin's head was still in the shadow. The small brown hands were tight-clenched, the eyes slightly open, fixing him almost with their lifeless stare. Foo rose from the chair as though impelled by the fury of an idea.

Entering the house, he flung an order to the attendants. "Clear the rooms!" he bellowed in harsh Cantonese. "Every one must go! There has been trouble. Lock the doors."

The motley crowd surged dumbly out, conscious that the affair wkh Trones and Lo Jin was responsible for their sudden exit. In five minutes the gambling house was in darkness, with the girls packed away in their shuttered cubicles.

Ty Foo returned to the dark veranda. The night was as hot as a tiger's mouth. The compound was not visible from the road and was protected by a high wooden fence. Other Chinamen would have tilled this idle piece of land and made it yield fruit and vegetables. But Foo and his satellites were too absorbed in the more profitable business of farming men and women, and often robbing the many helpless victims of the opium habit.

So the big garden became a wilderness, a sanctuary for spiked lizards and rats and colonies of ferocious black bull-ants and tarantulas.

Foo sat in his low-backed chair and contemplated Lo Jin. If the boy was shamming death as he had learned to in the temple of Shai-wai-Yat, he would wake shortly and give some sign. He must!

The Chinaman stepped over him, breathing in short, fat gasps. "Lo Jin, you hear my voice, I know. You get up like a good boy. Everybody gone home now. You play the game very well. I savvy that you are one very great artist. You have done enough. Get up and eat some food. I give you one nice drink of tea."

There was a pleading note in the Chinaman's voice that was almost pathetic, but the soft unction of his words were lost on Lo Jin. The listless curve of his limbs, the flat inertia of his body, held an air of finality stronger than spoken words or vague protests.

Ty Foo's brain worked at the double. Some one, he knew not who, was perpetrating a fraud on him. There were ways and means, however, of testing these matters.

He rose with a savage grunt, listened with his great jowl bent as though to read sounds in and about the house, and then, with the strength that slumbered like a lion in him he raised Lo Jin in his arms as if he were a child of ten.

"I shall wake you, Lo Jin!" he said aloud. "You shall not deceive me or put shame on my house!"

He strode through the dank weeds of the compound, over tangled lianas and ferns, muttering aloud as he walked. Halting in the center of a cleared space, he drew breath in great gusts, for despite his muscular abnormalities, opium had shortened his breath.

Before him was a hill of sand, granulated and scarified by the inexhaustible activities of a colony of savage bull-ants. These aggressive creatures had always interested Ty Foo. He had seen the carcass of a goat clean picked between dawn and dark. The wolves of northern Manchuria were not more deft at their work than these swarming myriads.

A faint fluttering of silk garments accompanied by the soft trip of slippered feet caught his ear. He turned slowly and confronted the fluttering figure of Hena Moy. Her soft eyes were ablaze with an unknown terror.

"Hwa?" he challenged, his teeth bared in her direction. "Why you come?" Hena seized his arm and held it tenaciously. "You must not put his body for those ant-devils to defile! 0 man of crime, you know not what you do?" she warned.

His slat-eyes seemed to devour her young face; his huge, muscle-packed arms relaxed their grip on the boy's slender form. This toy of a girl with her theater-bred ways had always feared him—shrank from his presence with the threat of a dagger or poison lurking in her small fingers. But always eluding him.

"Say what is in your heart!" he found voice to declare. Her very presumption stirred a latent superstitious dread within him. Not for mere desire to save this temple dancer would she dare interfere. There was something else in her mind.

"The claws of the ant-devils will not wake him!" she announced. "In your arms, O man of crime, you are holding the flesh that our priests have made sacred. Beware!"

"Beware—what? I do not understand your talk, Hena Moy." His voice shook from the superstitious curiosity he could not hide. "What you mean?"

"Look at the five marks on his right arm, thou defiler! The marks that are burned in with the gold rings of Buddha! I have traveled far, from land to land, making music for barbarians and coolies to laugh at. Every one near the temple of Shai-wai-Yat has heard of this Lo Jin. Dog-ants will not destroy his pure body. Try, thou eater of crime—try, thou—"

Ty Foo shrank from her pointing finger, the sweat of his superstitious terrors oozing from his throat and brow. The hot night sky seemed to spin above his head.

"Aie! He is dead!" he choked, holding the slender figure for her to scan. "It was not my hand that struck him. You saw it, Hena Moy!"

Hena smiled bitterly, her madonna eyes poring over the still form in his arms.

"I saw this boy enter your house, Ty Foo. By his gestures I read what his talk told you. You gave him coolie work, the sacred one who has breathed the fires of holy places. Your wicked thoughts were busy finding a way to profit by the strange gift which heaven has bestowed on him. Hunger drove him to confide in you. And your evil mind soon discovered a use for him. You wanted Trones to strike him. I saw that," she asserted boldly. "You saw a chance to get money from Trones—out of the gift of death which the priests gave to this boy."

Ty Foo gasped and cringed in his morbid terror of mind. His face grew lifeless; yet there lingered a doubt in his mind.

"Trones put gold bonds in this boy's coat. They have gone, Hena Moy. It was too quick!" he complained softly.

She stamped her slippered foot on the ground. Anger flamed in her eyes. "The coward put them there to prove the boy a thief! Lo Jin is not a thief, Ty Foo. Take care that Trones does not put the gold bonds where they will be found on you!"

The Chinaman winced. Then slowly, with his burden still clasped in his arms, he returned to the veranda. His tongue had grown dry as flint, his head dizzy under Hena's accusations. He placed Lo Jin carefully on a mat and stood pondering heavily in the shadow of the palms.

"What shall I do?" he asked after a while. "How shall I protect myself against Trones if he swears that I have the gold bonds?"

Hena's answer was swift and direct.

"You must go to the Buddha house at Lindang in the hills, and make offering for thy sin against the priests."

"Lindang is ten miles away," he objected. "I cannot go. It is a coolie's business. I have no belief."

"Then the crime will find you out, keeper of shame. The hot rings of Buddha will burn your throat, eyes and heart, until you cry for poison to stop your agony!"

"I have my business to attend!" he persisted weakly.

"The police will close your house tomorrow unless this boy awakes."

"He will not awake!" the Chinaman wailed. "I have seen dead men, and men who sleep after the smoke, but this boy is dead, Hena Moy."

"Go to the Buddha house at Lindang, I say. Make offering and bow your head and heart to the only one. Return here and the boy will awake!"

A heavy sigh escaped Ty Foo. His mind seemed to grow clearer. He saw new lights.

"I will go to Lindang," he agreed. "Let us put Lo Jin in my room. You shall stay beside and watch him in my absence. I will burn sticks from the holy place at Peking. They cost eight gold tael to the hundred. I will offer butter and fresh milk and spices from the emperor's shrines. And if the boy awakes, do not let him go, Hena Moy."

"He shall not go," Hena said in a low voice.

"I will teach Trones something that he will remember. Come!"

Again raising Lo Jin from the mat, he passed into the dark, silent house toward his own apartments. Over the door of his room was a gargantuan laughing mask that reminded Hena of a god of suicide she had once seen in a shrine at Hankow.

He placed the boy almost tenderly on his favorite mat and turned to the watchful Hena standing in the doorway. "Let him lie here until I return from the Buddha house. No one shall come near you."

He passed from the room, leaving her standing beside the door. After he had gone she closed the door gently, thrusting home a long iron bolt she discovered at the bottom. A perfumed oil lamp stood within a niche in the paneled wall. She lit it carefully and then looked about her.

The apartment was crowded with bric-à-brac and curiously carved opium pipes. There were ivory fans from the palaces of departed Manchu princes, and enough porcelain to enrich the cupboards of the most fastidious connoisseurs.

She pushed open the window overlooking the main thoroughfare, letting in a draft of air upon the scent-drowsed atmosphere. She heard the voice of Ty Foo rating his, rickshaw coolies. Then, after a while, she beheld the rickshaw passing swiftly in the direction of Lindang in the hills.

For the first time she was able to look calmly at the figure of Lo Jin on the mat. The face was bloodless, the limbs cold. A shadow of uneasiness crossed her as she pressed her warm hands near his heart. There was no response to her efforts. A feeling of misery assailed her, for it seemed possible that this foolish boy had allowed his spiritual gift to carry him too far into the valley of the great shadow.

She sat very still beside him, her mind wandering back to her simple childhood days when she first met Lo Jin outside the temple gates at Soo Loon. His mother was old, his father a cripple and a beggar. Only money could help such people as Lo Jin and his destitute little brothers and sisters. Ah, it was terrible when she remembered the piles of gold she had seen thrown away and lost in Ty Foo's gaming house!

The night crept by, and the dawn came with a clatter of Traffic near the quay, the rough voices of sailormen and coolies. She leaned on her elbow and peered at the dark face beside her on the mat. The body seemed to have grown warm, the hands were moist. Her massaging fingers moved around his heart, pressing and flexing the soft muscles with the skill of an expert.

A sudden faint tide of warmth spread through his limbs. She gave a low cry of anticipation and drew back as the heavy lids opened slowly, and his lusterless eyes regarded her in dazed wonderment.

"You are awake, soul of mine!" she whispered. "The day is here!"

His tight fingers closed on hers. He made no effort to rise, but stared fixedly as one emerging from an anaesthetic.

"Give me a drink—water," he said with difficulty.

Some ice water stood in an earthen jar, near the cooling air of the open window. She held it to his lips while he sipped like a famished sailor.

"You are my good spirit, Hena," he said weakly. "Ahe, it is not sweet to wake from death. But for you I should not have come back, flower of God!"

He lay still while the sun climbed over the distant hills, heating the air and bringing life to his cramped limbs.

She related what had happened, and whispered her plans for the future as she fluttered about the room. A big brass gong stood near the door; she touched it with the courage of her new-found authority. A clean-limbed house coolie answered almost immediately and remained with bowed head in the doorway awaiting her orders.

She planned a breakfast of tea, fruit and eggs, with plenty of rice and fresh cream. In a little while the food appeared, on silver trays and in dishes of porcelain.

They ate and chatted with the knowledge that Ty Foo had finished his offerings in the temple of Buddha at Lindang. Any moment his rickshaw might enter the compound below.

Still, Hena Moy did not hurry. Her plans were set, and nothing could alter them now. She gazed long and earnestly into the boy's face to satisfy herself that the black mists of the death trance had gone. Among the piles of garments, hung in a far recess, was a priestlike robe with a hood, used on occasions, no doubt, by Foo, when secretly leaving or entering the house.

"Gather this round your body, Lo Jin," she commanded. "We must leave the house."

He stood up with the robe drawn close to him, the hood pulled over his brow. Hena disappeared for a few moments and returned wearing a heavier coat and walking shoes.

Still chatting loudly, she led him from the house to the street and along the quayside. No one opposed them. The morning crowds on the marine front were not interested in young Chinese couples or runaway slaves.

Hena halted outside a glass-fronted building that bore in gold letters "Southern Bank of Asia" on its wide windows. She glanced at the open glass doors and the rows of Chinese clerks seated on high stools behind the brass grille, and motioned to Lo Jin.

"Stay outside, pearl of my heart! We now come to our destiny, which is written in the three great books. Wait."

Stepping lightly inside, her alert eyes fastened on an inner door beyond the row of gaping clerks. Some customers stood at the counter. Without waiting for permission, she opened the door of the inner sanctum and entered.

It was a small office, furnished with leather divans and easy chairs. At a square table sat Trones, slack-mouthed, dull-eyed as a fish on ice. His leaden eyes lifted to Hena's, and for a moment the shock of their meeting was like a stroke of steel on his tense nerves. He sat back, gripping the sides of his chair.

"What do you want, Hena Moy?" he asked hoarsely. "You've no right coming in here."

Hena sighed deeply; then from the pocket of her walking coat she drew the five pink-papered gold bonds, bearing the stamped characters and engravings of the Chinese government.

His slack hands closed on the bonds involuntarily. "Whose trick is this?" he questioned sharply. "Yours or that big yellow cur that runs the joint?"

"Mine," she answered promptly.

"Then you filched them from the dead fellow's pocket?"

"You put them there to make the dead boy a thief, Mr. Trones," she answered in excellent English. "Being a rich man, you had a skin to save. The boy had only his coolie loincloth."

His fingers continued to tighten about the bonds. He did not speak for a while, but she noted that his hand shook strangely. A cold smile played about her lips. All her life she had been honest with men and women. To her there was no great mystery in what had happened. The foolish boy, Lo Jin, had learned of her whereabouts in Fanuti. With famine driving the population to despair he had sought her out in the islands of gold and plenty. She had no knowledge of his coming. And now she had to get square with Trones. For her and others it was salvation or starvation.

"You put those bonds on the boy, Mr. Trones. You knew he was past resisting. I saw and heard you througb the veranda window."

"The boy is dead?"

"I am speaking of the bonds, Mr. Trones. You told the deputy that Lo Jin had robbed you. Now, what about it?" she questioned with Western assurance.

"Tell me if the kid is really dead!"

"Would you help if you thought your blow had not killed him?"

He glanced at her sharply as if making up his mind. "Yes," he said at last. "I'd give more than enough to be out of this hell scrape!"

She opened the office door and beckoned him. He rose and followed the direction of her gesture that indicated the cloaked figure near the road, the figure that had haunted his fevered dreams overnight. He gazed long and critically at the pallid, half-turned boyish features before returning to his chair.

"Last night—I thought he would not wake again. He has been starved. So—I sent Ty Foo to the temple of Buddha to make offering," Hena Moy declared simply.

"Are you prepared to leave Fanuti?" he asked earnestly.

"I am going home with Lo Jin, Mr. Trones. He will marry me," she added with a piquant grimace. "Ty Foo can have my mandolin when you have done with him, sir."

Trones made rapid calculations with a pencil, then called to the teller behind the brass grille outside. Trones handed him the five gold bonds.

"Cash these, Wu Cheng, and hand the money to this lady," he instructed coldly.

The teller bowed and returned to the counter.

Trones faced Hena, his eyes grown easier, his voice stronger.

"I wish you luck, Hena Moy! Look after the kid and don't let him die until you've made him happy. One of my ships, the City of Peking, is leaving No. 5 berth at midday. I'll telephone the skipper to give you a passage home."

She held out her gloved hand. "Good-by, sir, and thank you!" She paused a moment to meet his wavering glance. "You are wondering," she ventured finally, "whether I am a saint or a crook!"

The ghost of a smile illumined his eyes. "You have steered the only course, Hena Moy. The loser pays. Good-by, and good luck!"

Hena collected fifty thousand dollars at the counter. She passed leisurely from the bank and joined Lo Jin. A few minutes later the crowd had hidden them from view.

TRONES sat very still in his office, a grim smile tightening his lips. Then, true to his promise, he rang up the City of Peking, instructing the captain to reserve saloon accommodations for Miss Hena Moy and Mr. Lo Jin. Afterward, Trones sat back in his chair and appeared to be listening to the pandemonium of sounds and cries that drifted across the quay.

At the moment he was about to inspect a ledger at his elbow, he became aware of a familiar, elephantine shadow silhouetted against his office window. A few seconds later Ty Foo flung into the room, a disheveled and distraught figure, his face covered with dust and grime of the roads. In his slat-eyes there was heat, rage and bewilderment.

He stood in the center of the small office, his head lowered like some huge animal about to charge. "Lo Jin has gone with Hena Moy!" he stated hoarsely. "Tell me about the gold bonds, my fliend, I do not know which way you are playin' the game!"

Trones smiled with his teeth close-snapped. "Hena had the bonds. I've just bought them back. Owing to the burning of your punk sticks at the temple, the kid came back to life. It seems to me, Foo," he went on casually, "that you framed up that little comedy last night for your own profit. You didn't lose a minute trying to squeeze me on the shipping deal we had together. Needless to say, it will not be paid. I can now telephone McLagan and tell him just what's happened."

Ty Foo mopped his hot face, the dry grin of the beaten gambler creasing his parchmentlike skin.

"Hena Moy was getting old," he rumbled. ." She wanted welly much to buy a farm an' keep chicken. Allee my girls talkee farm when they glow tired of my house. Let her go. You welly lucky, Trone, on'y to lose fifty thousand dollar!"

"Oh, I'm not losing a cent, Foo!" the white man assured him blandly. "You banked on that priest kid to help you clean me up for half a million or so. You might, if Hena had taken any chances. She played her own game. Yours missed by ever so little. The kid nearly died. Hena will now retire for life on a little duck farm in the more salubrious atmosphere of Soo Loon.

Lo Jin will make a nice husband if he does not start dying among the eggs. Still, my dear Foo, young people must have a start in life."

He paused to light a cigar and to mark the effect of his words on the red, moonlike face of the Chinaman before him.

'^Your account at this bank, Foo," he continued placidly, "totals one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars exactly. From that amount will be deducted the fifty thousand paid to Hena Moy, in consideration of services rendered last night. How's that, Foo?"

A gleam of murder shone in the big Chinaman's eyes; his body seemed to pulsate from the shock of the banker's statement.

"You t'ief!" he shouted. "How daree you tak' my money?"

By way of answer Trones lifted the receiver at his elbow, and called up police headquarters.

"Hello, hello, McLagan! Trones speaking. I want to make a statement about that little affair at Ty Foo's house last night."

"Go on, Trones," came back over the wires. "I'm listening."

"Well, Ty Foo had a young kid from one of the Soo Loon joss houses in his place last night. This kid was a specialist in the cataleptic trance business. You have seen them in India and all over the East. Well, Ty Foo induced this kid to—to—"

The big Chinaman seized his arm in a grip of iron, drawing it from the receiver. "I'll pay you for the gold bonds, Trone! No more squeal from me! Shut up now!"

Trones nodded and waved the Chinaman aside. "I was saying, McLagan," he continued at the receiver, "that Ty Foo induced the kid to take a job in his house. Unfortunately the boy ran foul of me as I explained. But fortunately he is all right now, and Ty Foo has been kind enough to pay his passage back to China. His sweetheart, Hena Moy, has gone with him; in fact, they are at this moment to be seen on board the City of Peking, cabin No. 9. Is that all right, McLagan?"

"All right, all right, Trones. Quite understand. Hope the kid and the girl will be as happy as love birds!"

They were.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.