RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

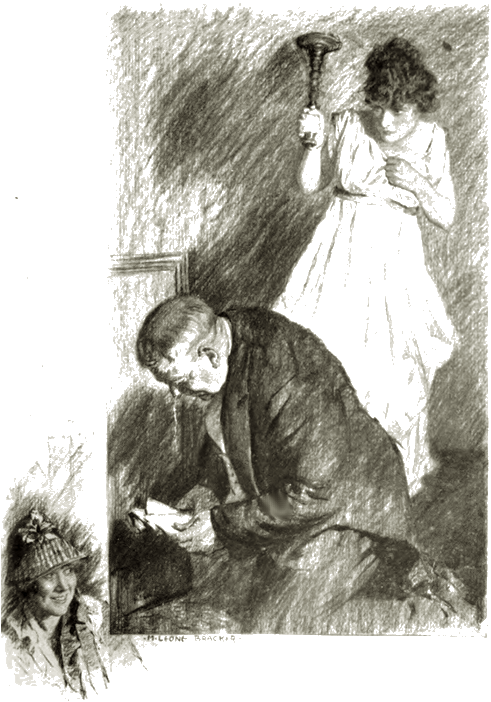

"The Door of Dread," A.L. Burt Company, New York, 1916

"The Door of Dread," The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, 1916

"The Door of Dread" is a fast-moving Secret Service adventure novel set against the tense backdrop of pre-World War I espionage. It blends undercover work, international intrigue, and a touch of romance, all driven by Stringer's characteristic pace and flair for action. The United States government faces a series of alarming intelligence leaks—naval codes, fortification plans, wireless innovations, and submarine technology are being stolen and funneled to foreign powers. The Secret Service identifies a shadowy mastermind behind these operations: Keudell, a brilliant and ruthless foreign agent. To counter him, Chief Blynn of the U.S. Secret Service assembles an unlikely team of operatives, each with his or her own strengths and vulnerabilities.

An adroit and attractive young woman.

"WHAT'S your name?"

"Sadie Wimpel."

"And your home?"

"Anywhere under me hat!"

The heavy-jowled man with the incongruously alert side-glance looked up across the polished desktop.

"What do you mean by that?"

"That me home's mostly where I happen to be."

He studied her with an eye as wistful as an old hound's eye in winter. She looked as dapper and neat, in her trim-cut tailor-made gown, as a well groomed polo pony. And under her neatness of limb was a suggestion of strength, and under her strength a trace of audacity, and under that audacity a touch of restiveness.

"Have you ever been in Europe?"

"Sure!"

"Where?"

"About all over the lot," was the languid response.

"I asked you where?"

"Well, Odessa, Budapest, Palermo, Petersburg, Rome, the Riviera, Paris, Ostend, Amsterdam, the——"

"That'll do!" cut in the man at the desk.

"Quite some little pilgrim, ain't I? the trim-figured young woman in the Bendel hat had the effrontery to ask.

The man at the desk fingered a paper-weight fashioned from an old coin-die of the Philadelphia Mint.

"Supposing you tell me what you know about this Fletcher report leak," he quietly suggested.

There was a rustle of silk as Sadie Wimpel crossed her knees.

"Admir'l Fletcher roped out a Navy report showin' how and why a foreign fleet could land in the United States. Sen'tor Lodge s'bmitted that report to the Senate. But before doin' it he told 'em the report ought 'o be printed in confidence, as they put it, and the motion was carried. Secret'ry Daniels, yuh see, didn't want any foreign guy gettin' next to the data in that report. It'd be LIke advertisin' your safe-combination to——"

"I know all that."

"Well, there was a certain foreign guy got hold o' that report."

"Who was it?"

"A capper for Keudell."

"But who?"

"The same capper that got hold of our secret signal code book from the destroyer Hull last summer."

"How do you know that?"

"B'cause I'm a friend of a friend of a friend of the boob of an ensign who gave up the book and faced a court-martial for it, a few weeks ago, on the Oregon."

"Where was the Oregon when that court-martial was held?"

"Anchored in San Francisco Bay," was the girl's answer.

For a moment or two Chief Blynn of the Secret Service stared out of the broad window of the Treasury Building. Just beyond that window was the Washington Monument, and behind that the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, where the electric elevators were rising and dipping with their afternoon crowds, and into B Street was swarming a motley throng of designers and engravers and plate-printers, side by side with stitchers and counters and sizers, with steel-press men and bull-gangers and oil-burners from the Ink Mill, all hurrying homeward after the day's work. They were part of a machinery which took on a touch of nobility because of its labyrinthine intricateness, because of its sheer unguessed complexities. Yet they were a mere company in that vast army which Chief Blynn and his agents were appointed both to appraise and protect. And they brought home to the haggard-eyed official so meditatively watching them a hint of the more immediate complications confronting him.

"You said you'd done Secret Service work before?" he asked, as he turned back to the girl.

"Yes."

"Where?"

"In Europe."

"Anywhere else?"

"Right here in America."

"For whom?"

"For yuh!"

The chief looked ponderously up from the papers in which he had pretended to be so pertinaciously interested. It was an old trick of the chief's, that of masking his mental batteries behind an escarpment of manuscripts.

"Then why haven't I a record of that work?"

"I guess you didn't know I was doin' it."

"Why?"

"Because I was actin' for Kestner."

"Of the Paris office?"

"Yes."

"And with anybody else?"

The girl hesitated.

"Yes; with young Wilsnach as well."

The chief glanced down at his pages of script.

"On what case?"

"The Lambert counterfeitin' case."

"Then why aren't you still acting with Kestner?"

"Because he's quittin' the Service."

"Who told you that?"

"Wilsnach."

"Does Wilsnach tell you everything he knows?"

Sadie Wimpel uncrossed her knees.

"Not by a long shot!"

"But working together that way, the two of you naturally became more or less confidential?"

A slight flush showed under the rice-powder on the woman's sophisticated young face.

"I was wise to Kestner's duckin' the buggy long before Wilsnach ever opened his peep about it."

"How did that happen?"

"Because I knew the skirt who was cannin' his purfession'l chances by marryin' him."

"Does marriage always do that?"

"When a slooth settles down it ain't wise to stack too high on him stayin' the curly wolf o' the singed-cat crib."

The chief puzzled for a moment or two over this apparently enigmatic statement.

"Then it's Wilsnach you want to swing in with on this new work?"

"Not if I have to crowbar me way into it."

"But why are you so sure you can help the Service out in this case?"

"I never said I wanted to help the Service out."

"Then what do you want to do?"

"I want 'o see Wilsnach make good."

For just a moment a smile flickered about the face of the pendulous-jowled man at the desk. It made the watching girl think of heat-lightning along an August sky-line.

"But how do you know Wilsnach is going to be put on this case?"

"Because he's the only man yuh've got who can round up that gang."

Again a meditative silence fell over the man at the desk. Then he threw aside his pose of hostility, as a man makes ready for work by throwing off his coat.

"Sadie, how old are you?" he quickly inquired.

"Good night!" was the girl's grimly evasive answer.

"You said your name was Wimpel. Have you any other?"

"None worth mentionin'."

"You mean you're not a married woman?"

"Not on your life!"

"And never were?"

A shadow crossed the pert young face under the Bendel hat.

"Me for the single harness!" she announced, with a shrug.

He sat pondering her for a silent moment or two.

"What nationality are you?"

"Come again," said the puzzled girl.

"Are you a good American?"

"I won't gamble on the 'good.' But ain't bein' just Amurican about enough in times like these?"

"It's enough!" acknowledged the man at the desk, with a sigh.

"But what I wanted to get at is, where did your parents come from?"

"Me mother was Irish."

"And your father?"

"Search me!"

The dew-lapped head moved slowly up and down. Then came still another moment of silence.

"Now, Sadie, there's a door you're keeping shut between the two of us."

"A door?" echoed the girl.

"Yes, a door that you don't seem willing to open; a door that seems to lead out on other days." He raised a heavy hand at the flash of alarm in her wide-open young eyes. "But I'm going to let that door stay shut, my girl; for as long as it stays that way it needn't count with either one of us."

"I don't quite get yuh," murmured the not altogether tranquil young woman. "And what's the game, anyway, wit' all this third-degree stuff?"

"Have I seemed too inquisitive?"

"No-o-o-o! But when yuh get me thumb-prints and me weight, tub-side, yuh'll just about have me record, won't yuh ?"

The chief smiled as he bent over the papers in front of him.

"My dear girl, we've had your record here for the last five years. That's part of our business."

"Hully gee!" said the girl, stiffening in the chair where she sat. Then, furrowing her young brow, she craned apprehensively about at the intimidating sheets of closely-written script.

"But that's not the point, Sadie," pursued her inquisitor. "The point is that you're a remarkably clever young woman."

Sadie Wimpel, under her rice-powder, turned promptly and visibly pink.

"Aw, Chief, cut out the con!"

"But I mean it." The girl shook her head.

"I'm a mutt and I know it. And I've been as nervous as a cat since I breezed in here, for when yuh swivel-chair boys throw a scare into me I flop straight back to me Eight' Ward talk. But plant me outside wit' the hotel broads and I can pull the s'ciety stuff so's Ida Vernon'd look like an also-ran!"

"You're not only clever, Sadie, but you're attractive. You're young and you're good to look at. And the fact that you're a distinct deviation from type makes you especially valuable for the work we're going to lay out for you."

A secretarial-looking young man in glasses entered the room and stepped softly to the chief's desk. There he murmured a discreet word or two and as softly left the room. Chief Blynn's hand went out and touched a buzzer-button on his desk-end. Insignificant as that movement was, the girl's quick eye detected a valedictory note in it.

"Then yuh're goin' to gimme that work?" she asked as she rose to her feet.

"That depends on your friend Kestner."

"Where does Kestner come in?"

"He comes in through that door in two minutes. He and Wilsnach, in fact, are waiting out there to talk this case over with me."

"So Wilsnach's there too?" said the girl, staring at the door.

"Yes, Sadie; but I've got to deny you the pleasure of seeing him. I want you to step out this other way, and go straight back to your room at the Raleigh. Then I want you to wait there until I call you up. And to-night after dinner either Shrubb or Brubacher will come and explain just what has to be done !"

The heavy-bodied man was on his feet by this time, piloting her toward the door on the far side of the room. But the girl hung back for a moment.

"There's just one thing, Chief," she ventured, with a hand-movement toward the written sheets on the desk-top. "Have yuh gotta put Wilsnach wise to all that dope there?"

"What dope?"

"About me black velvet past!"

The chief laughed.

"That's an operative's report on the Warren pearl-smuggling case," he explained. "But in the matter of that door I happened to mention, I said it would stay shut, Sadie, and shut it stays!"

"I get yuh!" she announced, as she passed out of the room. But flippant as her words were, there remained in them a tremulous note of gratitude.

Chief Blynn swung about, still smiling, as the door on the opposite side of the room opened. The next moment he was shaking hands with Kestner and Wilsnach of the Paris office.

"Kestner," the head of the Service said as he sank into his swivel-chair, "I want you to come back."

"My fighting days are over," announced the man who had said good-by to the Service. Yet he looked with no unfriendly glance at the ponderous face in which was set the shrewdest pair of eyes he had ever stared into.

"Then make this your last fight," almost pleaded the official, who plainly was not greatly given to petitioning for favors.

"Try the younger men," Kestner smilingly suggested. "Give Wilsnach here a chance on the case."

The man from the Paris office shifted a little uneasily.

"Wilsnach was on the case for a week," explained the chief, "and yesterday he asked me to wire for you."

There was open reproof in Kestner's glance at his colleague of other days.

"Wilsnach knows I came to America for quite another purpose," he explained; "for the somewhat personal, though trifling, purpose of getting married."

"My dear fellow, by all means get married," began the man at the desk. "But—"

"But at once tear off on a beagle-chase around the world after some verminous criminal with a weakness for ten-cent bed-houses and traveling steerage!"

"This chase will not take you out of America," corrected Chief Blynn. "That much I can guarantee."

"But it will take me out of my club and my newer way of looking at things," explained the patient-eyed Kestner. "You see, I seem to be developing a sort of philosophic sense of humor, and that leads to self-criticism, and that in turn keeps whispering to me that gum-shoeing and gray hairs don't always go well together!"

"So what you want is peace with honor, the same as the rest of this country that's sleeping on a volcano!"

"I've had enough of the volcano, at any rate."

"Well, for a family man who's tired of eruptions, I should think an embassy secretaryship, say Rome for ten months, then London for a year, and then one of the quieter Continental Embassies itself, would be just about the right thing to keep the rust off."

Kestner turned and eyed the older man; but that older man disregarded his stare.

"This isn't loose talk, Kestner. We can't expect you to come back without making it worth while for you. But you know the way things stand with the Administration. You know the Navy people can't afford to let much more of their stuff get out. And when you land your people you'll get your post. That's as sure as taxes and death!"

"You could do it inside of a month," prompted the bland-eyed Wilsnach.

"There are occasions," said the solemn-eyed Kestner, "when a month may seem a very long space of time."

"Isn't an ambassadorship sometimes worth three or four weeks of waiting?" inquired the man at the desk. "I know a few guys who've worked twenty years for 'em!"

"But I'm not working for ambassadorships."

"D' you mean you don't even want one?" was the somewhat acidulated inquiry.

"It's a great honor, and a great opportunity," acknowledged Kestner. "But when I work for my country I don't do it with one hand in the pork-barrel!"

The chief's gesture was one of heavy impatience.

"This thing's already been thought over and talked over. Foreign posts aren't passed around like trading-stamps. They go to the men equipped for them—and from this year those men are going to need greater equipment than flashing a gold-headed cane and writing sonnets. You know seven or eight languages, and you've covered Europe for ten or twelve years. You've learned the lay of the land and served your country on some pretty big questions."

The big form leaned forward over the desk and the big voice dropped to a more serious tone. "Kestner, that country needs you now. It needs you as it never quite needed you before. And if you're the American I think you are, you're going to side-step the tulle and organ-music for a few weeks and help this Administration out of a hole!"

A telephone-call interrupted the chief's words, but never once did his eyes leave the other man's face.

"Remember, it's not this newspaper war-talk that's worrying us. We're three months ahead of that. And it's not the ship-bombs and the factory-burnings and the labor-plots that are worrying us. We've got plenty of good workers to trail down the rest of that rough-neck stuff. We can handle the Fays and Von Papens and Van Homes and Loudens and Scholzes easily enough, though we can't always holler out how much we know about 'em. But there's another gang operating over here that's getting on our nerves. For example, who told both Vienna and Berlin that we'd approached the Danish Minister on the matter of the purchase of the Danish West Indies and gave the Germans a chance to set the Rigsdag against the bill of cession? Who surrendered our vacuum valve amplifier, for picking up wireless, to that same power? Who stole the Pearl Island's mine-field maps for the protection of the Canal? Who gave our new Fort Totten target-firing records to the foreign agent who was taken off the Nieuw Amsterdam at Kirkwall and carried them in his shoe-sole when arrested? And God knows what might happen before our next dreadnought gets off the stays! And I'm only telling you one-half of what we're up against here, with this second underground band sneaking our data before it can even be reported to the Department itself. You can pretty well see, I guess, what's got to be done by some one from this office. And I'm not the only man who thinks you ought to do it. You can count on the Secretary of the Navy, and, what's more, you can count on the White House!"

Wilsnach moved, as though to break the silence, but Kestner stopped him. Then he turned to the thick-shouldered man at the desk.

"Let me explain something to you," he began in his cool and even tones. "You know what our work is. It's a bit like tiger-shooting, seductive enough, but still dangerous. It has, as you say, a great deal of rough-neck work, and now and then an occasional risk. When you're young, you're glad enough to face those risks. There's a thrill about it. But to keep on at it, once you're nearing forty, you've got to have a spark of youth that won't go out. You've got to nurse your streak of romance. Now, the trouble is, I find my spark going out. The work doesn't seem romantic to me any more. It seems nearly always humdrum, and very often underhand."

"It's necessary work," interrupted the other.

"So is scavenging. And I feel I've done about enough of it."

"Then keep it up," persisted the chief, "by helping us clear away this final mess."

"But I'm tired of messes like this. I'm tired of the types they bring you in contact with. I'm tired of the way they have to be rounded up. I'm tired of crook-warrens and gun-play and wire-tapping. I want quietness and decency and an acre or two of lawn with a tennis-court at one end and a Japanese tea-house at the other!"

"Which is exactly what I've been trying to argue you into," promptly pointed out the chief. "You get all those things when you get your rosewood desk at the Embassy—with a silk hat and a state carriage thrown in!"

"My experience with Embassies," suggested Kestner, "hasn't precisely fixed them in my mind as abodes of quietude."

"But instead of stewing along the undercrust, you'll be a monument on the upper," said the chief, with a repeated heavy gesture that was almost one of impatience. "And we can leave the Embassies out, for we've got troubles closer than that. We've got one of the shrewdest and completest systems of espionage ever organized to break up. As I've already told you, we've founds leaks from the Navy and from the Aviation Corps. Our cipher codes have been stolen and our wireless adaptations lifted. Our canal fortification plans have been dug out, and we know two different foreign powers are trying to get the secret of our new balanced turbines, to say nothing of the Cross torpedo for which, we know beyond a doubt, one Intelligence Department has offered a cool million. And we have every reason to believe the whole business is being engineered by one of the trickiest foreign agents who ever bought a war-map."

Kestner sighed a little wearily. "And the gentleman's name?" he casually inquired.

The chief was silent for a moment or two, as though weighing the expediency of making further confession to one still outside the Service. Then he pulled out a drawer and tossed a mounted group-photograph across the desk.

"That's an enlargement from a moving-picture film showing the crowd that watched the launching of our new submersible destroyer. We stumbled on it by accident. But in that crowd is one face, and if you look at it under the glass you'll see the face of the man who's organized the entire system that we've got to beat. That's about all we know, beyond the fact, apparently, that he's working with foreign people he's brought over for the purpose, people unknown to our operatives here."

"But who's the man?" repeated Kestner, running a casual eye along the welter of closely crowded figures on the mounted picture.

"Keudell!" was the chief's answer.

Kestner's hand dropped to the desk-top. "Keudell?" he echoed, a trifle vacuously, as he took up the picture and searched through its serried faces with a narrowing eye.

"Then you've heard the name?" inquired the chief.

"Yes, I've heard the name," was Kestner's slowly enunciated answer. "And even Wilsnach here will recognize the face, I imagine."

"You mean you know the man?"

"Do we know him, Wilsnach?" Kestner asked, turning to his colleague, bent low over the photograph.

"That's Keudell," cried out the younger man. "I'd swear it."

"And what do you know about him?" asked Blynn, turning back to Kestner.

"For one thing, that I hate him the same as a woman hates a snake."

"Why?"

Kestner's answer was neither so prompt nor so direct as it might have been. "Because embodied in him is everything about this life that made it, and still makes it, odious to me."

"Does that mean," asked the chief as he watched Kestner restore the photograph to the desk-top, "that we're not to count on you in this case?"

Kestner stared for a meditative moment or two at the Washington Monument. Then he turned back to the man at the desk.

"I'm not the man for this case. But I know the people it belongs to. And I can at least start those people right."

"What people?" asked the chief.

"Wilsnach here, for one."

"And the other?"

"Is a young woman named Sadie Wimpel."

"Why this young woman?"

"Because she knows Keudell the same as a keeper knows a diamond-back!"

The heavy-shouldered man behind the desk was already on his feet.

"Then supposing we talk to the Secretary of the Navy for five or ten minutes," he suggested. "And then we'll see if we can't get in to the President himself for a few minutes."

The other two men had already risen.

"The first thing we ought to do," explained Kestner, "is to round up Sadie Wimpel."

"That," announced the chief as he crossed to the Inner door, "should not be a difficult matter."

"Do you happen to know Sadie?" Kestner asked.

"Sadie Wimpel, gentlemen, is already engaged on this case," announced the chief, with a pardonable note of pride in his voice. "And to-morrow, as Madame Fatichiara, the world-renowned astrologist, I might add, she will be doing the decoy-duck act just off Broadway!"

IT was six days after his conference in Washington that Kestner was breakfasting in his rooms overlooking San Diego Bay. He had his reasons for privacy, and nursed no inclination, apparently, to mingle with the gayer company thronging the wide verandas and corridors of that huge hostelry which seemed to exist only for laughter and music and dancing and love-making.

Yet the table was laid for two, and as Kestner sat before his iced Casaba he might have been seen to glance repeatedly and impatiently down at his watch. His look of anxiety, in fact, did not pass away until a telephone-bell rang and the hotel-office announced the arrival of Lieutenant Keays.

"I'm sorry to be late," proclaimed this young lieutenant, as Kestner admitted him and at the same moment dismissed the waiter.

The newcomer, who bore a startling resemblance to Wilsnach of the Paris office, inspected the laden breakfast table with evident relief. It was, however, a rejuvenated Wilsnach, an airy and summery Wilsnach in white cricketer's flannel, carrying a roll-brim Panama and a bamboo swagger-stick. "But to rig out in this get-up takes time."

Kestner, as they took their seats, cast a somnolently critical eye over his younger colleague. "You'll do!" he finally announced.

"But just why am I Lieutenant Keays?" inquired the man in cricketer's flannel.

"Because, my dear fellow, your arrival has been duly heralded in the evening papers," Kestner announced, "and there are one or two persons, quite outside official circles, who are rather interested in your new war-plane."

"My new war-plane?"

"Yes; which you have brought with you from the Brooklyn Navy Yard—at least, the specifications are now with you."

Kestner handed an oblong packet of papers across the table to his inquiring-eyed colleague.

"Then you've actually been finding something out?" Wilsnach asked.

"I've found out quite a number of things," was Kestner's quiet-toned answer, as he squeezed a slice of lemon over his fried sand-dabs. "And not the least important is the fact that Wallaby Sam is working with Keudell."

Wilsnach looked up in astonishment.

"That's a sweet pair to have against us!" he solemnly affirmed.

"But this seems to be only a side-show," Kestner explained. "The main-top, we must remember, is back in New York. It's only outpost work we're doing here, Wilsnach, for it's Sadie they've planted at the center of things."

A shadow crossed Wilsnach's face.

"But will it be safe for that girl, working alone there?"

Kestner smiled.

"You'd rather have her here?" he inquired.

"Couldn't she help us out, on a case like this?"

"But this case, Wilsnach, is off the main line. And you needn't worry about Sadie Wimpel not being able to take care of herself. In the meantime, however, we've got our own work cut out for us."

"Along what lines?"

"I'm not quite sure myself, yet. You see, I've had to keep under cover and remain a purely nocturnal animal, so to speak. And that's counted against me."

"Why under cover?"

"Because one of the facts I've dug out is that the sweet-scented couple we spoke of a moment ago have got Anna Makaieff operating for them, and operating right here in this hotel."

"Makaieff?" cogitated Wilsnach. "That name's new to me."

"Well, it isn't to me—and I've had the dictaphone annunciator on the end of this jointed bamboo fishing-pole covering her window every night it was open."

"Where does she come from?"

"Her father was an Anglicized Pole and her mother a music-hall singer in Paris. She was trained for the stage herself, but married before she was twenty. Then she went to India with an English army-officer who knew nothing of her antecedents. There she hitched up with a Russian grand-duke and ran away to the Orient, where she was soon deserted, and had to live by her wits. Keudell found her there when he was buying up German coast-defense data, and took her to Vienna, where she learned two or three more languages, and how to dress, and a few of the tricks of the international spy trade. She was four years in Petrograd, and those four years, I'd venture, cost the Russian government a good many million rubles in military leaks. Then she rather dropped out of things for a few years, for she actually fell in love with a young artist and stuck to him like a bur until the family railroaded the boy out of the country. To-day she's an exceptionally adroit and attractive woman of the panther type, at the dangerous age of thirty, and with her claws this time set in the flesh of a Lieutenant-Colonel Diehms out here."

"And has Diehms been—?" Wilsnach seemed reluctant to put his fellow-officer's fall into words,

"I'm afraid so."

"Poor devil!"

"Yes, poor devil, for he has a wife and two children at Wilmington, and Shrubb wires me they're the right sort!"

"And does the Makaieff woman dream you're on her trail?"

"Naturally not, or she'd even let Diehms out of her claws to get away. It makes me sick to see that poor devil dancing about with her. He's like a man in a trance."

"Could she care for him?"

"Not a rap! What she's after is Navy information. Why, she had possession of every detail of our L-1 ten days after it was launched at the yards of the Fore River Shipbuilding Company and three weeks before its acceptance trials by the Navy people themselves. And now she's after our new airship specifications. That seems to be her main object. But incidentally she's picking up any Army or Navy secret that she can get her hands on. So the only thing for this man Diehms to do, when the truth comes out, is to shut himself up and quietly blow his brains out."

"But can you afford to let him do that?"

"I can't exactly say, just yet. But our panther has hypnotized him. For example, you read last week about the aviation tests over here at the North Island school? You probably read how Lieutenant Taylor, of the Aviation Corps, established an endurance record for eleven hours and twelve minutes on only thirty gallons of gasoline. That was with our new Farlow motor. Keudell and his people to-day have full specifications of that motor in their possession. Anna Makaieff is the agent who got it for them—though it didn't come from Diehms. And inside another ten days, if no one interferes with her activities, she'll know as much about our secret adaptation of the Crozier-Buffington disappearing carriage for coast-defense guns as the Chief of Ordnance himself. So that gives you a slight hint of why this very handsome young lady from Austria has to be rounded up."

Wilsnach poured himself out a second cup of coffee. "She won't be easy to corner, I imagine."

"The hardest part is Diehms, with that decent family to pull down after him," was Kestner's meditative reply. "The poor devil can't be saved, of course. But I find it isn't easy to get the thought of that Wilmington home out of my head."

"And the woman doesn't worry you ?"

"What good is a woman of that type? She's like a cat in a squab-pen. The sooner her hide is nailed to the aviary door, the better. She's merely a sneak-thief in spangles. She's nothing more than a penny-weighter with a Paris accent, or a lush-dip with the grande dame air." Kestner's gesture was one of half-wearied disgust. "She's just panther—which means cat written large. What I'm trying to tell you is that she's carnivorous, and always will be, for wherever your panther wanders you are going to find her feeding on somebody's flesh and blood. And we'd all prefer that she wandered about in some other part of the world."

"Panthers aren't so easily rounded up," reiterated the mild-eyed Wilsnach.

Kestner sat for several minutes in studious silence. Then he smiled as he glanced up at his younger companion. "The approved method of rounding them up, I believe, is to locate their runaway, and then stake an innocent young lamb down in the jungle."

"And you're to be the lamb?" was the quick inquiry.

"On the contrary, I'm too lamentably old for such uses. And the wool would never cover me, for there's a limit to all disguises, once you've been known. Besides, your bleat can always give you away. You agree with me there, don't you, Wilsnach, that a man can never really disguise his voice?"

"I've never seen it done, off the stage."

"Precisely. So that counts me out with the lady, with whom I once had the pleasure of conversing."

"Then who in thunder is going to be the lamb?" was Wilsnach's perturbed demand.

"How would you like to be?"

"I wouldn't like it at all," was Wilsnach's prompt retort.

"Well, you may as well get used to the idea," and this time Kestner spoke without smiling, "for my plans are made, and you're going to be planted right in the path of this most predaceous lady."

"Well, it's not work I care for, and that I'll say right now!"

Kestner got up from the table and looked a little wearily out across the Bay where the green lowlands of the Aviation Field were freckled with the tiny mushrooms of serried army tents.

"I've always said, Wilsnach, that there are times the Service takes us into dirty work. And I'm sorry if this has got to be one of them."

THE second evening following the printed announcements of the arrival of Lieutenant Keays at the Coast a number of his younger fellow-officers tendered him a quite informal dinner. This dinner, which was served in one of the upper rooms opening off the dancing-floor, was sufficiently convivial in character to attract the attention of casual couples tired of waltzing and fox-trotting to the strains of an orchestra.

It had been the source of much disappointment to the young stranger from the Brooklyn Navy Yard that Lieutenant-Colonel Diehms had failed to attend this dinner. Yet Wilsnach, keeping his wits about him, did not betray his feelings. For before the evening was over he had the satisfaction of seeing Diehms step into the room where he sat. The last notes of Nights of Gladness had just died away, and to the young Lieutenant-Colonel's arm clung one of the loveliest women that the man from the Paris office had ever had the dubious good luck to behold.

Wilsnach, for all the byplay with those about him, studied her closely, but not so closely as he studied the face of the man with her.

"I call that an uncommonly beautiful woman," ventured the light-hearted Wilsnach to the officer on his right as he glanced toward the small table to which a silver cooler filled with chopped ice had just been brought. "Who is she?"

"That's Madame Garnier," answered the man on Wilsnach's right.

"Then not an American?"

"No; she's merely spending the winter here."

"But why here?" blithely persisted Wilsnach.

"She's rather interested in aviation. They say her husband is Garnier, the French inventor who's getting out that gyroscopic stabilizer for air-craft. She's going to look after the government trials for him."

Yet as the talk at Wilsnach's crowded table grew louder, and the laughter more convivial, the shadowy-eyed woman with the orange opera-cloak looked more than once in the direction of the newly arrived Lieutenant Keays. From under her dark lashes, from time to time, she might even have been detected studying his well-tailored figure with a not altogether impersonal interest. Her companion, it might also have been observed, lapsed more and more into periods of gloomy silence. And if Madame Garnier occasionally spoke at greater length to the young French waiter who attended her table than might seem necessary, and if this waiter showed any undue interest in the neighboring table and its noisy officers, no one outside of the alert-eyed Wilsnach seemed to take notice of the matter.

When the technicalities of a wordy argument among his confrères warranted Lieutenant Keays in producing certain papers and specifications from his pocket, and he allowed these to pass from hand to hand about the table, a close observer might also have noticed the minutest tightening of Madame Garnier's languorous lips. And when these papers were duly restored to the young lieutenant's possession, and later to his pocket, the woman with the ivory-white skin might have been seen whispering certain information to the gloomy-eyed officer beside her. Then as the glasses were refilled and the noisy talk resumed, Madame Garnier and Diehms left the room.

When, an hour later, the last toast had been drunk and Keays' last companion had bidden him good night, he wandered disconsolately but warily about those suddenly quieted upper regions off the dancing-floor. He wandered erratically yet alertly on, with his heart in his boots, for the sudden fear possessed him that Madame Gamier had retired for the night. Then quite as suddenly he felt his heart come back from his boots to his throat. For as he stepped out of the deserted ballroom he felt his body brushed by the perilous fringes of a golden-orange opera-cloak trimmed with sable. At the same moment a little Watteau-like fan of ivory dropped to the floor.

He stood staring down at it stupidly. He heard a small coo of startled laughter and an even softer apologetic murmur of regret. He leaned forward unsteadily and groped about on the polished floor, trying, with what appeared to be the ineffectual struggles of inebriacy, to recover the fan.

The woman at his side laughed a second time, laughed softly and mysteriously, as she stooped and caught it up. Then she crossed the room and passed out through the door into the shadowy darkness of the wide loggia swept by the balmy night sea-breeze.

Wilsnach, with studiously unsteady steps, made his way toward that same door and stepped out upon the same shadowy loggia. There, finding the wide spaces of that balmy-aired veranda unoccupied, he groped his way to a huge rustic chair beside the railing, and after swayingly communing with nature and essaying several fruitless efforts to reform his dangling tie-ends, subsided into a sleep that seemed as untroubled as it was profound.

Out of the shadowy doorway behind the sleeper stole, a few moments later, the equally shadowy figure of a woman in a golden-orange opera-cloak trimmed with sable. She advanced slowly and noiselessly to the railing, close beside the rustic chair. She turned toward the chair, stood motionless and murmured an almost inaudible sentence or two.

Her words, however, brought no answer from the recumbent figure with the straggling tie-ends. So the woman looked quietly about, stepped closer to the sleeping man and stooped over him.

A tingling of nerves needled through Wilsnach's cramped body as he felt the touch of that white hand. The fingers slipped like a snake in under his coat, but he neither moved nor lifted an eyelid. He was conscious of the fact that the woman's breath was fanning warmly at his face, that he lay within the aura of some soft and voluptuous aroma, that there was something perversely appealing about the very nearness of that perfumed body, no matter what mission had brought it so close to his own. He could still feel the slender fingers feeling exploringly about under his coat.

He could hear her quiet little gasp of relief as they closed on the packet of papers which he carried there. And he was conscious of her complete suspension of breath as the hand, still holding his papers, was slowly and stealthily withdrawn.

The next moment she was standing at the rail again, as quiet as a statue, staring dreamily out over the moonlit water. Then she turned and with a quickening murmur of drapery passed out of the circle of Wilsnach's hearing and observation.

He waited there, however, for what seemed a reasonable length of time to reckon at the margin of safety.

Yet the tired limbs remained as cramped as before. For at the very moment he had decided to gather himself together he heard the sound of a stealthy step behind him. A man stood at his side, stooped close over his face and then once more peered cautiously about the darkness. For the second time a tingle of nerves swept through Wilsnach's tired body. And for a second time a hand insinuated itself under his coat, padded quietly about and then proceeded to explore his lower pockets.

But the search proved fruitless. The man swung about, crossed the loggia and hurried in through the open door. As he did so Wilsnach twisted quickly about In the rustic chair, and peered after him.

A second later the disappearing figure had passed from Wilsnach's line of vision. His glimpse of the man was a brief one; and the light had been uncertain. But it both angered and amazed him to realize that his second visitor had been an agent so menial; had been, in fact, one of the hotel waiters.

He was still half-kneeling on the chair, with a head craned about its back, when a quicker step sounded beside him and a hand was clamped on his shoulder. The next moment he saw It was Kestner.

"Who was that man?"

"Never mind who he is. You get down to the carriage entrance and head off Diehms if he tries to climb Into an automobile. I'll get to the main door and stop him there, If he goes that way. If there's no sign of Diehms at your end of the house put a man on guard and get back into Madame Garnier's rooms with this pass-key. For if Diehms and that woman ever get out of this hotel, it's good-by!"

"But what can they do?"

"God only knows! But I've a feeling, Wilsnach, that we'll never see them alive again!"

Wilsnach did not linger to talk this over. He made his way down through the hotel and inspected the neighborhood of the porte-cocheère. He found there, however, no trace of Diehms. So, having slipped a bill into the hand of a sleepy-eyed "starter," he explained what was expected of that attendant and quickly swung back through the all but deserted hotel corridors.

He hesitated for several seconds before the door which he knew to be Madame Garnier's, for he was still uncertain as to what was demanded of him. Then he took a deep breath, fitted the key to the lock, listened intently and stepped inside.

On his right, he could see, stood a partly opened door, and he felt convinced of the fact that it led to a bedroom. This discovery left him a little uneasy and a little uncertain as to how to advance.

Then all thought on the matter suddenly vanished, for a quick sound smote on his startled ear, a sound like that of a window-sash being savagely pried open.

This was followed by a rustle of drapery and the quick sharp scream of a woman. Then came a silence, followed by the sound of a woman's voice, slightly tremulous with terror. "Who are you?"

It was a man's voice that answered, menacing, deliberate and not altogether pleasant to hear. "Never mind who I am. But I want those Navy plans you took off that Easterner, and I want them quick!"

"You will never get those papers," was the woman's deliberately defiant reply.

"I think I will!"

"Those papers belong to the Navy Department and they will go back to the Navy Department, no matter what Keudell or any of his spies may do!"

The man, apparently, had advanced farther into the room.

"Keep back!"

"Not this—"

The sentence was never finished. The next moment a shot rang out, followed by the sound of an uncertain step or two, and then the dull thud of a falling body.

Wilsnach, with his heart in his mouth, ran across the room and darted in through the half-open door.

In the center of the bedroom he saw an ivory-skinned woman in an evening-gown, with a smoking revolver in her hand. Stretched out on the floor lay the figure of a man. Beside him, on the polished hardwood floor, glistened a small pool of blood. And Wilsnach's first glance told him this was the same man who had stooped over him as he lay in his loggia chair.

The next moment Wilsnach was at the telephone. "Send the house doctor to Madame Garnier's rooms at once. At once, please, for it's an emergency case."

Then he called over the wire: "Give me room four hundred and twenty-seven." Frantically as Wilsnach called room four hundred and twenty-seven, he could get no response there from Kestner. And now, of all times, he wanted the guidance and help of his older colleague. For he was in the midst of a tangle that he could not quite comprehend.

"If this is known," still sobbed the woman, "everything will be lost."

Wilsnach stood regarding the tumbled mass of her dusky hair. He stared at it a little vacantly, as though it were no easy thing for him to digest his discovery.

"What shall I do?" cried the white-shouldered woman, as she looked up at him with distracted eyes.

"What do you want to do?" asked the somewhat bewildered Wilsnach.

Instead of answering that question, she stared at him with what seemed to be a sudden reproof.

"Can't you see what has happened here?" she asked, in little more than a whisper.

"I can see that we both seem to be working for the same Service, without quite—"

"Then what are we to do?" she cut in. "For no one must dream I'm in that Service——and every moment means danger!"

"There are several things we can do. The first is to let in that house doctor. But remember, no one else. Then wait for me here until I get back!"

He was off, the next moment, scouring the midnight hotel for some trace of Kestner. It was not until he reached the loggia itself that he caught sight of his older colleague's figure. And Wilsnach hesitated for a moment to approach that older colleague, for he saw Kestner was already accosting a trim-shouldered officer with a military cloak thrown over his arm.

"Lieutenant Diehms?" Wllsnach could hear his fellow-operative say. He could also see the officer's curt head-movement of assent.

"There's a matter I'd like to talk to you about," announced Kestner.

"Why?"

"Because in this hotel, not an hour ago, Madame Garnier stole a number of Navy secrets from an officer named Keays."

The two men confronted each other. Their stares seemed to meet and lock, like the antlers of embattled stags.

"Who are you?"

"I'm from the Secret Service at Washington, and I am here investigating Navy leaks—Navy leaks in which you are involved."

"In which I am involved?" repeater the officer.

"Do you know who Madame Garnier is, and where she comes from?"

"She is a confidential agent of our own government," was the officer's reply. "And she comes from Washington for the same work that you pretend to be doing."

Kestner stood for a moment studying the other man. But his vague look of pity did not desert him.

"I'm sorry for you, Diehms! Truly sorry! Because you've been made a tool of—more than a tool of!"

Diehms swung suddenly about. He caught the other man in a grip as fixed and frantic as the last grip of the drowning.

"By God, you'll not say that!" was his passionate cry.

Kestner had no chance to reply to that cry, for Wilsnach, reluctant to wait longer, stepped quickly up to him.

"Something's happened," announced the newcomer, at a loss as to how he should proceed.

"I know it," quietly acknowledged Kestner.

"But I must speak to you alone!"

"On the contrary. Lieutenant Diehms will be equally interested in the occurrence," coolly declared the older man. "So you needn't hesitate to speak out."

But still Wilsnach hesitated.

"Then I'll do it for you," explained the calm-eyed Kestner. "You were about to announce that Madame Garnier, to protect certain invaluable Navy secrets, has just shot a man who attempted to force those secrets from her. Is that not true?"

"Yes!" gasped Wilsnach.

"And is it not equally true that he was shot in the leg?"

"Yes."

"And yet, Wilsnach, entirely for our benefit! Listen to me, both of you. An hour ago Madame Garnier found she was under observation, when she stole certain papers I've already mentioned. She is a quick-witted woman. She proved this by the promptness with which she pretended she'd taken those papers to forestall their theft by quite another spy. But that spy is her own colleague, once known as Soldier-Ben. For the last three weeks, I find, he has been gay-catting for her here in this hotel as a waiter."

"Preposterous!" was the one word that came from Diehms' lips.

"Yet equally true," continued Kestner. "But that is not all. Madame Garnier had other evidence, to-night, that her position had become a dangerous one. She realized things had suddenly come to a final issue. She made several discoveries, yet one of them was not the fact that during the last three days a dictaphone had been placed in her room—as my duly transcribed shorthand will later show. She knew she was near her last ditch. She had courage, and she had cleverness, so she engineered this particular shooting-scene, promptly and deliberately engineered it with that poor dupe of hers, for the purpose of throwing us off the track, if only for half an hour. During that half-hour, as you very well know, Lieutenant Diehms, you and she would be out of this hotel and in a motor-car headed for the Mexican border."

Diehms stood with unseeing eyes.

"What," finally asked the young officer, "what will this mean—for her?"

"From twelve to twenty years in federal prison at Atlanta," was Kestner's answer.

A visible muscular twinge ran through the man's rigid body. "And for me?" he added.

"Only one thing—court-martial."

The young officer with the premature gray about the temples folded his arms. He stood for several moments staring heavily ahead of him.

"I'd prefer... ending things... in the other way," he slowly announced.

"l'm sorry," said Kestner, as he looked out over the midnight Bay, twinkling with its countless lights. "But it seems the only way out!"

"It's the only way," echoed the officer at his side.

"But even then there are certain things to be remembered," Kestner reminded him.

"I have not forgotten them."

"Then we can arrange those details in my room, if you'll be so good as to wait for me a moment or two."

Kestner, as the officer walked to the end of the loggia, turned to his colleague, wiping his forehead as he did so. "Wilsnach, the side-show's over, and they've sent word for you to catch the first train for New York. Are you ready to start?"

"Yes, I'm ready," the younger man replied. "But what are you going to do about this poor devil Diehms?"

Kestner stared out over the water.

"You'll find the answer to that waiting for you when you report at Sadie Wimpel's rooms. And then you'll understand why I've been saying that Service work can't always be clean work!"

SIX days later a funereal old figure came to a stop before a shabby-fronted house in a shabby New York side-street not far from Herald Square. He hesitated for a moment at the foot of an iron hand-rail, red with rust. Then he glanced pensively eastward toward Broadway, and then as pensively westward toward Eighth Avenue. Then the dolorous eyes blinked once more up at the sign-board which announced:

MME. FATICHIARA

PALMIST AND ASTROLOGIST

The next moment the man in black ascended the broken sandstone house-steps and rang the bell.

He stood in the doorway, pensive and dejected, with his rusty umbrella in his hand. About his arm was a band of crape, faded to a bottle green, and on his bespectacled face was a look of timorous audacity.

He rang again, apparently quite unconscious of having been under scrutiny from a shrewd pair of eyes that stared out through the shuttered grille-work of the door itself. Then he sighed heavily, and was about to ring for the third time, when the door opened and he found himself confronted by a large negress who, while arrayed in a costume that was unmistakably Oriental, still bore many of the earmarks of Eighth Avenue origin.

"Madame Fatichiara?" the visitor ventured, with a timid glance at the imperturbable turbaned figure.

The negress solemnly nodded, stepped aside and motioned for him to advance. This movement was made with an arm far too athletic to be lightly disregarded. Then the door was closed behind him, and another door at the rear, suggestively presided over by a stuffed owl with two small ruby lights set in its head, was silently opened.

The visitor sidled in past a screen embossed with a skull-and-cross-bones surrounded by an ample parade of what appeared to be interlocked copperheads worked in lemon-yellow. Then he edged about a bowl of goldfish suspended from a black tripod and found himself confronted by a silent and motionless woman in an ebony-black peignoir.

This woman sat behind a table draped with black velvet, on which still another suggestively reptilious design was worked in beryl green, the emblem in this case being that of a diamond-back rattler engaged in biting its own tail. On the table behind which the woman sat as motionless as an Egyptian idol stood a green jade vase in which smoldered three Japanese punk-sticks. Beside it, on a bronze tripod embossed with snakes, stood a glass globe, iridescent in the shadowy and uncertain light of the curtained room. Facing it was a human skull on a black plush pad embroidered with the signs of the Zodiac, while behind the skull stood a planchette, a pack of green-backed playing-cards, a lacquer tray of what appeared to be "mad-stones," and an astronomical chart of the heavens, framed and under glass.

The newcomer's pensive gaze, however, was directed more toward the woman than toward her significantly arrayed accessories.

As this woman's figure was backed by the dusky curtains of a materializing cabinet, and her heavily massed hair was itself as dark as these curtains, the contrasting pallor of her face, well whitened with rice-powder, produced an impression that approached the uncanny.

This impression of uncanniness was in no way mitigated by the blue pigment which had been added to the elongated eyelids or by the woman's studied attitude of languor and aloofness or by the fixed stare with which her mysterious and half-closed eyes accosted her crow-like visitor in rusty black.

This visitor, however, dropped into a chair facing the young seeress. He regarded her and her surroundings with a nod of pensive approval. Then he took out a cigar and proceeded to light it.

For one brief moment the mystic-eyed seeress watched that unlooked-for movement. Then she sank limply back in her chair.

"Hully-gee!" she suddenly ejaculated. The blue-lidded eyes were now staring and wide-opened. Their owner's air of esoteric mystery suddenly evaporated, pricked like a soap-bubble by that one betraying exclamation.

"Hully-gee, if it ain't old Willsie himself!"

Wilsnach looked quickly yet casually about, to make sure they were alone. "Sadie," he solemnly murmured, "you're fine!"

"Well, I ain't feelin' the way I look! But it kind o' sets me up, Willsie, to lamp that classic map o' yours!" She stared at him long and hungrily. Then she sat back with an audible sigh. "I guess yuh ain't back none too soon!"

"Why?" asked Wilsnach.

"B'cause yuh're sure goin' to lose your little stick-up, if yuh leave her long in this dump!"

"Anything happened?"

"Yes, lots! And here's a letter Kestner sent on for yuh."

Wilsnach took the note from her hand. But he stood smiling down at her, without breaking the envelope's seal.

"Sadie, you're fine!" he repeated.

"Fine!" she cried, wuth a hoot of derision. "I was more'n that. I was dog-goned near fined!"

"Wait," commanded Wilsnach. "What was it I told you about that enunciation of yours?"

"Oh, gee, teacher, I just gotta denounce a while b'fore I can stop to pr'nounce! I always get weak on the English when I get indignant. And I've been some little bob-cat for the big-gunners o' this swamp!"

"But why were you nearly fined?"

"Well," began the seeress, with an abandoned rush of words that contrasted strangely with her earlier air of immobility, "I hadn't been stuck up in this drum two days b'fore a flatty lamped me street-sign and blew in for a two-dollar palm-readin'. So I took 'im by the mitt and said he was sure goin' to make a journey soon. And he sez to me, 'Excuse me, miss, but yuh're the guy who's goin' to do the travelin'! And it's goin' to be right over to the Island,' he sez, 'for I'm a plain-clothes man from Headquarters!' Seein' Kestner and yuh'd told me the Feds had ev'rything fixt, I give him the glassy eye and sez, *Nix, honey-boy, nix! Save that for the web-foots,' sez I, 'for I'm hep to this burg and what yuh kin pull over on the chief! I ain't been hibernatin' up-state wit' the hay-tossers, son, and I wouldn't be exhumin' this ol' stuff if I didn't have purtection!' 'Well,' sez the flatty, showin' his badge, 'yuh'd better send in a hurry call for them purtectin' spirits, for I'm goin' to gather yuh in, and I'm goin' to do it right now! So git your street-rags on!'"

"Why didn't you do as we said, and phone Hendry?"

"That gink wouldn't let me git near a phone, nor git long enough out'n his sight to stow away a box o' smokes. He towed me acrosst to Eight' Avenoo b'fore he even melted enough to let me call a taxi. He was jus' swingin' the door open when a cop come along. That cop sez, 'Whadda yuh doin' wit' the skirt, Tim?' The gink climbs in beside me. 'Pinchin' her fur palm-readin',' he sez, as he waves for the driver to git under way. And that cop was all that saved me from being disgraced for life! He put a hand on me friend's arm and sez, 'Nuttin' doin', Tim! If they hadn't jus' brought yuh in from the goat-cliffs yuh'd a-knowed the green lamps was givin' this lady the wink! She's a federal plant, son, and yuh'd better git her back before the whole ward gives yuh the laugh!' And he got me back. But when I got back I was so hot under the collar I cudda jumped the Service for life!"

"We all have our troubles, Sadie, at work like this," soothed Wilsnach, as he studied her pert young face. He realized, as he watched her, that the very audacities which had once made her a trying enemy were converting her into an invaluable colleague.

"But this stall's bin trouble from the first crack out o' the box!" complained the young seeress as she lighted a cork-tip cigarette. "It's easy enough to say not to talk and jus' feed your sucker list on a few Mong-jews and Wollas and Sack-rays, for to make 'em think I'm French. But I ain't no more French 'n a Frankfurter, and I can't git away wit' it! I jus' can't!"

"Then you've already had visitors ?"

"Visitors? Say, a street-sign like mine brings the nuts down like an October black-frost! Gee, but the ginks yuh bump into at this game! The first ol' guy who got a dollar readin' turned confidential and said he was a widower and wanted me to join him in a Back-to-Natcher Society and take dew-baths in his back yard. Then a fat Swede who'd been a ring-thief in a Turkish-bath joint wanted me to work the Riviera wit' him as a hotel-sneak. Then a fat woman wit' three chins and no lap, the same claimin' to be the slickest clairvoyant on the Island, pleaded to know jus' how I could git p'lice purtection, especially wit' a face like mine! The ol' cat! Then a yellow-faced undertaker wit' a front yard full o' spinach and a white string-tie wanted me for his housekeeper up in Syracuse. Natcherally, I said nuttin' doin', Grandpaw!"

"Go on!" prompted Wilsnach.

"Then a mutt in the sash, door and blind trade wanted to move in wit' his trunks, bein' soused to the gills and tempor'ry furgittin' home and mother up in Ithica. Zuleika rolled him down the steps and left him cryin' ag'inst a hydrant fit to break your heart! Then a mulatto lady bookmaker come in to git me to dream track-numbers for her. So in me off time I'm makin' a stab at pickin' the circuit winners. Then' another washed-out ol' guy wit' a patented Elixir O' Life wanted me to run his Second Ark O' The Sacred Elect and be his spirit-wife on the side. I told him to git ready for the grave b'fore his mind went any worse!"

"Is that all?"

"Not by a long shot! Yesterday a couple o' promoters dropped in. One wanted me for a come-on to a company o' his to make blood oranges by stabbin' 'em wit' a needle-ful o' saccharine and red aniline. The other had doped out a scheme for makin' a million or two importin' the Guatemalan kelep-ant to kill all the boll-weevil out o' the cotton states. He offered to split even and pay travelin' expenses if I'd get out and lobby for state grants. Then a widow come in for a message from her husband, and got cryin' all over the place until I hadda warn her she was spottin' me plush-goods. I give her back her money and told her this spirit-rappin' game was all bunk. Then a couple o' sailors come in from the Navy Yard, and—"

"Sailors?" snapped out Wilsnach.

Sadie dashed his hopes. "They was soused to the gills—worse'n the sash and door guy! They was so lit up I short-changed 'em a couple o' bones, jus' for squeezin' me hand durin' business hours!"

"There doesn't seem to be much for us to work on in that group," meditated Wilsnach, after a moment or two of silence.

"What I wantta know," demanded Sadie, fixing him with a rebellious eye, "is jus' why I'm planted here, and jus' what good I'm doin' at this palm-readin' guff!"

"There's a reason for it, Sadie, and the reason is this: We've got to rake this big city for a man named Dorgan. We don't know where he is, or where he's headed for. All we know is that he's hidden away somewhere in New York."

"But where d' I come in?" demanded the seeress.

"You come in as the decoy-duck who's going to persuade the gun-shy stranger to dip down into your neighborhood. For before this man came to our city, Kestner tells me, he'd been consulting a fortune-teller named Madame Fatichiara."

"Then I ain't the one and only?" demanded Sadie Wimpel, with a distinct note of disappointment.

"No, you're merely the one particular kind of fly our particular kind of fish will rise to. I mean by that, Sadie, that if our man sees your sign, or stumbles across your newspaper advertising, it's reasonable to assume he'll come out of hiding and try to have a talk with you."

"I don't quite git that!" objected Sadie.

"You're his friend of other days," explained Wilsnach. "You were his adviser before he went under cover."

"Then why'd he go under cover?"

"Because ten days ago when he was fired from the Sinclair Steel Plant he stole a bundle of chart plans of one of our Navy boats. That boat's our new long-cruising submarine known as the Carp-Mouth Submersible. It's called that because it has a system of air-valve ejectors for mine-laying and a perfected mechanism for taking on fresh supplies along the sea-bottom. That gives it a ninety-day cruising radius without any need of returning to its base, in time of war. Dorgan got those plans. In the same bunch he also got the new Dupont magnetic detector, for indicating under water the approach of any ironclad. They were all plans and specifications from which decently qualified experts could finally work out models."

"Then this guy Dorgan's a spy?"

"Old man Sinclair contends Dorgan isn't a paid agent, but merely a sore-head who tried to get even with the company by sniping any office-papers he could grab while waiting round for his pay envelope, after being fired. Sinclair says he can't even know the value of those papers, for most of the work was done in bond and under government inspectors. That's a matter we can't be sure of. But there is one matter we can be sure of, and that is that for these papers Dorgan could get a quarter of a million in cold cash!"

"Hold me up!" breathed out the amazed Sadie Wimpel.

"Kestner's belief is that Dorgan was actually planted at the Sinclair Works. There's a kink or two in Dorgan's record. We know that he originally came from the government gun factories at Watervleit, that he was some six months at Newport News, and that he even did work on the new Arizona in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. That doesn't look like a plant. But he may have been after something worth waiting a couple of years for. The worst kink in his record, though, is that Dorgan became a pool-room habitué."

"Playin' the ponies?"

"Yes; and through this he got to neglect his work and was finally discharged. It was this woman named Fatichiara who gave him track-return tips. That's about all we know, except one thing. And that one thing is that Keudell and his gang would cut this man's throat as quick as they'd strike a match once they thought those plans were within their reach !"

"How d' yuh know he ain't gay-cattin' for Keudell right along?" demanded Sadie.

"Because Keudell doesn't appear to have been on this trail two months, let alone two years. There may have been others, it's true. But Kestner wired me that he'd got enough tips from the Madame Garnier papers to show that Keudell himself had laid a number of ropes. And those are the things we've got to trace up!"

The mention of Madame Garnier's name took his thoughts back to the letter which he still held unopened In his hand. Sadie Wimpel sat resentfully watching him as he tore the end from the envelope and unfolded a sheet of paper on which a clipping from a newspaper was pasted.

"From the Los Angeles Times," he said aloud as he made note of a brief inscription at the bottom.

But Sadie's thoughts, at the moment, were not concerned with that communication.

"It's all right t' talk about tracin' up these things, but that kind o' tracin' takes yuh through a stack o' rough-neck work, and yuh know it as well as I do! The slooth-king who sits in a swivel-chair and rounds up the big crook by tappin' a two-story bean is all right for the movies, but it won't go in real life. And if yuh ain't ready to get your roof tore off yuh'd better can your hide-and-seek game wit' the Big House boys!"

"Just a minute!" expostulated Wilsnach, preoccupied with his sheet of paper.

"What's the dope, anyway?" demanded Sadie, blinking at the sudden solemnity of Wilsnach's face, as he stared abstractedly across the table at her.

"Listen," he said, turning back to the clipping which he held in his hand. Then he read aloud:

"To the long list of Pacific Coast aviation accidents must be added still another fatality. Early this morning Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Diehms, who had been cooperating with the Navy Aviation Corps at San Diego, together with Madame Theophile Garnier, the wife of a Continental inventor, met their death in the Pacific. The accident occurred while Colonel Diehms was experimenting with the new Garnier gyroscopic stabilizer for aircraft. The trial, which was under governmental supervision, involved an altitude-test with passenger. At an estimated height of about five thousand feet the machine was seen suddenly to dip and fall. As, unfortunately, both pilot and passenger had neglected to wear life-belts, neither body has been recovered..."

It was Sadie who spoke up out of the silence.

"Yuh don't mean to say that Kestner cooked up that end for 'em?"

Wilsnach looked at her out of unseeing eyes. Then he slowly nodded his head.

"I suppose it was the best way!" he meditated aloud.

"Hully gee," Sadie cried, as she sat absorbing the significance of the words to which she had been listening, "ain't that just what I've been tryin' to tell yuh? Don't that show yuh it's just dog eat dog, and the Old Boy take the guy who's too good to sneak a chance?"

Wilsnach, at the moment, was remembering what Kestner, only one short week before, had said to him about Service work. And it was with an effort that he pulled himself together.

"Well, Sadie, no matter what kind of work it is, we're in it, and we've got to go through with it! And the sooner we get down to tin tacks the better!"

"I ain't delayin' yuh!" announced the young woman beside the crystal-gazer's globe. But for the fraction of a moment a faint shadow hung about her face, a shadow of disappointment, apparently, at his calmly masculine eagerness to escape to the impersonal.

"We've got to remember why you're here, and why I'm here. And the answer is, Keudell. And our hopes of finding Keudell seem to hang on just one thin thread: that somewhere in this city is a thief who's stolen papers which he can't unload, unless he unloads them on Keudell. And if we can't find the thief, we've got to find Keudell, or the people who are acting for Keudell."

"Then why wasn't I give a description of this guy called Dorgan?"

"Because there wasn't time, for one thing, and, for another, Romano's been covering your house and would never 've let him get away before I had a chance to get here. But I'm going to describe the man, in case any of us should miss him. Dorgan's a mechanic, remember, and he's about thirty years old. He's wide-shouldered and rather short, with curly black hair, cut close. His ears stick out a little, and one of them is mushroomed, for he worked in the prize-ring for a couple of winters. Then—"

"Wait!" suddenly announced Sadie. The faint purr of a desk-buzzer had sounded behind her black-draped table. She bent her head and watched the quick play of the vari-colored electric globes of her tiny annunciator.

"Hully gee," she murmured, as she hid away the end of her cigarette, "here's a hob-nail comin' for a readin'. And Zuleika's pushin' the double-green to say he's a guy worth watchin'!"

Wilsnach, who was already on his feet, circled about the table and lifted the black velvet drapery of the cabinet.

"I'll wait here until your man goes," he quietly announced.

Sadie, reverting to her posture of esoteric impassivity, intoned a solemn "Ong-tray-voo!" in answer to the questioning knock on the door.

That door promptly opened and a man stepped into the room. He carried his hat in his hand, and Sadie could see the black hair that curled about the edges of his outstanding ears. He was half-way across the room before he stopped, hesitated and then slowly advanced toward the vacant chair that faced the table, groping for it with an abstracted hand as he stared into the woman's heavily powdered face. Then he sat down in the chair.

"You ain't Fannie Fatichiara!" he suddenly and deliberately announced.

"Ain't I?" murmured the impassive-eyed Sadie.

"You're a faker!" announced the stranger, suddenly leaning forward in his chair.

Sadie's somnolent eye was languid with scorn.

"If any she-cat's been crabbin' my name," she majestically proclaimed, "I'll put her outta business b'fore she kin squeal for help!"

The man sniffed. "You smoke cigars?" he demanded.

"No," was Sadie's languid retort. "But I guess that pool-room king I'm pickin' winners for kin maybe blow hisself to an occasional purfecto!"

"You ain't Fannie Fatichiara!" doggedly repeated the newcomer.

The woman behind the black-draped table suddenly lost the last of her majestic mien. "Well, if I ain't Fannie Fatichiara," she challenged, "I jus' wish yuh'd lead me to her!"

The man pondered this for a moment. He seemed puzzled. "All right," he suddenly announced.

It was Sadie's turn to ponder the problem so unexpectedly confronting her. "When?" she inquired.

"Any old time!" promptly declared the visitor.

Again Sadie pondered. "How'll we go?" she temporized.

"We'll go in a taxi, by gum," was the altogether reckless answer, "and the sooner the better!"

Sadie drew her sable wrappings together and rose with both dignity and determination to her feet.

"Then yuh wait until I grab me hat and mitts," she explained to him.

She stepped back and slipped in under the draped curtains of the cabinet front. There Wilsnach caught her by the arm, his lips close to her ear.

"Follow that man!" was his fierce whisper. "Keep with him to the last gasp. For that's the thief who stole our Navy plans!"

"Then gimme a gun," whispered back the unperturbed Sadie, before stepping out through the second tier of curtains at the cabinet back. "For I'm goin' to make good on this case or quit the Service!"

SADIE WIMPEL leaned back in the taxicab with a titter of care-free amusement. That worldly-wise young lady had long since learned to preserve an outward calm during her moments of inward tension. She experienced a desire to powder her nose, but there were reasons, she knew, why it would be better not to open up the hand-bag that lay on her lap. So she merely tittered again.

Her pertly insouciant face seemed to puzzle the man at her side. He studied the azure-lidded eyes and the rouge-brightened lips, studied them with a frank and open curiosity.

"Do you know where you're going?" he finally asked.

"Nope, but I'm on my way," was Sadie's blithely irresponsible reply.

For the second time the man beside her turned and studied her face. "You've certainly got nerve!" he slowly admitted.

"Yuh've gotta have nerve," conceded Sadie, "when yuh're scratchin' for yourself!"

"It ain't always easy scratching, is it?" he inquired, with a note of newly awakened hope in his voice.

"Not by a long shot!"

Her companion still hesitated. "Maybe I could make it easier for you," he finally suggested, though it took an effort for him to say the words.

"How?" languidly inquired the woman.

"I'll tell you that in about ten minutes' time." Then he added, in audible afterthought, "I guess I'm kind of up against it myself!"

He said no more, for the cab had stopped before a sinister-looking brownstone-fronted house with curtained windows and an iron-grilled door.

Sadie did not altogether like the appearance of that house. It looked like a place, she promptly concluded, where anything might happen. But she gave no sign of her secret misgivings.

"So here's where we wade in?" was her careless chirp as she stepped from the cab and followed the stranger up the brownstone steps, swinging her hand-bag as she went.

She watched him as he rang the bell, noting the two short and the two long pushes of his finger against the little button. Then she turned and glanced carelessly about at the house-front windows, making note of the fact that they were barred by a grille work which, if airily ornamental, was none the less substantial.

There was a wait of some time before the door itself was opened. It was opened by an oddly hirsute man in the service-coat of a butler. Sadie, whose quick eyes had taken him in at a glance, found him almost as unprepossessing as the house itself. He was a peculiarly large-boned and muscular-looking man, with his hairy skin singularly suggestive of a gorilla. His eyes seemed much too small for his heavy-jowled face, and about their haggard corners was a touch of animal-like pathos. Yet about those eyes was something sullen and reserved, something heavily taciturn, something which left the whole face as blank as the front of the curtain-windowed house itself.

"Where's the boss?" asked the man who had rung the bell.

Sadie watched both of them closely, determined that no secret message or sign should pass between them without her knowing it. But there seemed no break in the steely enmity of the servant's steely eyes.

"The boss is busy," he curtly announced.

"Well, he's expecting me," confidentially announced the caller.

"Both of you?" inquired the man inside the door, apparently without so much as a direct look at the woman with the carelessly swinging hand-bag.

"Yes, I guess we'll both come in." The words were spoken casually. But for all their quietness they seemed to carry the weight of an ultimatum.

The large-boned man at the door hesitated for one moment. Then he stepped back, watched the two visitors pass into the hallway and carefully and quietly closed the heavy door behind them.

"That's Canby," whispered Dorgan out of one corner of his mouth.

"Ain't he the sour old thing?" remarked Sadie Wimpel aloud.

To that alert-eyed young woman there seemed something ominous in the snap of the closing door's lock-bar. It seemed like the spring of a trap which might be cutting off all retreat. There was something dungeon-like in its very noisiness.

Her step, however, did not lose any of its carefree resilience as she followed her companion through the second door which the servant had opened for them. The questioning glance she turned on that companion, once the room-door had closed on them again, was as tranquil as ever.

"What kind of a dump's this, anyway?" she casually inquired.

The man, who had tiptoed to the door, made a gesture for silence. He pressed an ear against the dark-wooded panel and stood there listening. Then he turned and faced her. "You wait here for a minute or two," he said in a tone so low she could hardly catch the words.

She stood watching him as he silently and with the utmost precaution opened the door through which they had just passed. Then he closed it as quietly behind him.

Yet the moment that door was shut Sadie Wimpel's manner underwent a prompt and unequivocal change. She ran to the windows and found them locked and barred, as she had expected. Then she silently tried the second door at the back of the room. That, too, she found to be securely locked. Then she promptly peeled off her gloves and stowed them away in her hand-bag. She next gave the room itself her undivided attention, making note of the faded and shabby furniture, of the white mantel-piece with its silent ormolu clock, of the wires for the call and lighting circuits which ran along the broken picture-molding. Then she took one of the faded chairs, pushed it against the wall on the farther side of the room and quietly seated herself. Whatever happened, she preferred knowing there was nothing more than solid masonry at her back.

She was sitting there, with her knees crossed, when the door was once more silently opened and the man called Dorgan stepped back into the room. He came quietly, as though the house were the abode of sleepers who dare not be awakened. Yet Sadie noticed a change in his face. It looked more troubled. The skin had lost the last of its outdoor color. It looked oily, like the skin of a liner-stoker climbing deckward for a breath of air. She noticed, too, that he was breathing more quickly. And on the low forehead she could see a faint but unmistakable dewing of sweat-drops.

He did not turn and speak to her for several moments, apparently intent on making sure his return had been unobserved.

Then, still standing at the door, he turned and studied the young woman with the pert eyes and the carelessly swinging foot. That troubled look of his seemed one of appraisal.

"What's the game?" she quietly inquired.

He stepped forward as she spoke, crossing the room with the same studied quietness. Yet he shrugged a shoulder as he stood before her, as though to disguise the urgency, the apprehension, which he could not keep from his eyes. "I'm getting leery about these people here," he said in little more than a whisper. Then he stopped.

"What's the game?" repeated the patient-eyed woman.

"I've got certain documents these people want to get hold of. They want them bad, but they're going to pay me my price for 'em!"