RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

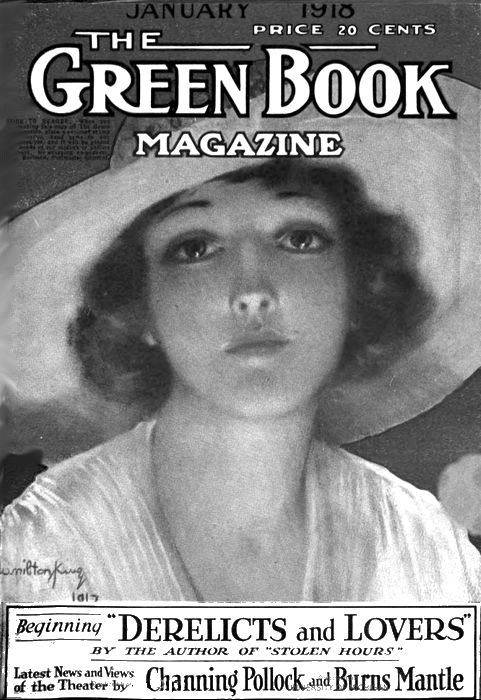

The Green Book Magazine, January 1918 with "Barhall—Barbarian"

WHEN the enormous, rose-gold ball of the declining sun balanced itself on the edge of the western horizon, and the pale dove-blue of the sky seaward merged swiftly into a dull and ever deepening gray, Barhall, who had been quartering the wide expanse of marshy "saltings" for the past two hours, called his dog, gave a last glance out to sea, and tucking his gun comfortably in the crook of his arm, turned inland.

"No more ducks for me on this coast for a year or two," he said aloud to himself, striding quickly over the lightly frozen sandy mud toward a little pine-wood a quarter of a mile inland

The slight breeze, blowing in coldly from the northeast, though it was no more than the beginning of winter, began to rise, and Barhall turned up the collar of his rough tweed shooting-coat.

"In Africa I shall miss my winters," be said, talking to himself and his dog, as those who are fond of lonely sport do. "I suppose there are wild fowl galore there, but it wont seem quite the same sort of sport shooting them.

Yes, I shall miss my winters,"—his eyes sought the pine-wood, and his face shadowed—"and my summers and all."

A speck of white moved under the outer line of wind-ravaged and stunted trees, and Barhall quickened his pace, broke open his gun and removed the cartridges as he went.

"There's an end to that for a time, Bill," he said to the retriever that ran beside him. The dog looked up, wagging his tail doubtfully, as though not quite sure that he understood There was little his master told him which he did not follow, but a two- or three-years' absence in Africa was not within his range of understanding.

THEY came in the early twilight to the road, crossed it, passed a stile on the other side and hurried across a stark pasture to the girl who stood in the shadows at the edge of the wood.

"Aren't you early, Isabel? Or am I late?" asked Barhall, and kissed her.

"I am early, Jack. I was free earlier than I expected, and I came to wait here rather than indoors."

"That's splendid, dear—every minute counts now." His arm was round her, and he was looking down at her with extraordinary pride and affection. And he had reason. For she was his, and she was very lovely, slender, fair and delicate, ethereal almost. She was one who had grown to beauty in a place of wide spaces and great clean winds, as some sweet moorland bloom or a pale windflower swaying upon a high cliff may grow to loveliness.

There was a coolness and translucency investing her; she was clear with the pure silvery brilliance of a new moon, but the delicate tint of rose upon her cheeks gave her the warmth that made her adorable. Her eyes were blue as the sea, and there shone in them the transient magic that dwells, all too briefly, in the eyes of every girl—the shy and faintly startled wonder of one who is far enough from childhood to glimpse the meaning of womanhood and to be thrilled and afraid and glad and confusedly happy at the kaleidoscopic life she glimpses.

"Oh, Isabel," he said suddenly, "I don't want to go."

"I shall think of you all the time," she said, "and you will think of me out here in the wind and the sound of the sea and the crying of the sea gulls, never seeing anyone else. That will help you. Jack—wont it help you to know that? And I shall be happy too, thinking of you."

But there was a tremor in her voice, and her eyes never looked away from his.

Barhall did not answer for a moment. His eyes had grown blank and absent, and his strong good-looking face had changed subtly,—hardened,—so that he seemed suddenly older and harsher.

"You know, Isabel, I never wanted to go with this expedition," he said sullenly. "It's not my line at all, and there is nothing in it for me—no glory, no profit. And if there were, I don't want it. Any glory I want I will get as a painter, and profit too. It's Paris I ought to be bound for—not some wretched jungle in North Africa. Good Lord! Who ever heard of a person whose one idea is to paint decently, wasting two years learning how to hunt for minerals and bribe savages for concessions!"

SHE put a white finger gently on his lips. She knew, none better, the queer, latent strain of savage obstinacy in him that sometimes asserted itself; and everyone knew of the same strain in that grim, bristling old man, Sir Henry Barhall, his father. Privately, she believed it was quite wrong, quite unwise, even a little tyrannous, to set a son who promised to become a fine, if not really great, painter, to do anything but learn the technique of the art he loved.

But she did not say so to Jack Barhall—she dreaded the possibility of the two quarreling. For all three of them knew the real reason why Jack was to go to Africa. It was not because his father wanted some one he could trust to guard his large financial risk in the expedition, not because he thought travel, of that kind, would polish Jack; but it was because Isabel Grey did not happen to be the girl Sir Henry wanted his son to marry.

They both knew, and neither had ever put it into words, until now ; and it was Isabel who spoke of it, troubled by the black frown that was ridging and lining itself between Barhall's brows, the tightening of his firm lips, the outthrust of his bold jaw and the bitter, ugly light that was dawning in his eyes.

"Why, he's cutting everything off," said the boy with a sort of resentful wonder, "—you, my work, my play, everything—all for nothing. Isabel, I'm not going. That settles it." His voice was deadly quiet at the last words, and she paled.

She stood back from him suddenly, and, facing him, put up her slim, delicate hands, one upon each of his shoulders.

"Dear, listen to me!" she said very gravely, and her eyes shone with the brightness of tears hardly restrained. "1 implore you to obey your father in this— to go upon this journey just for no other reason than because he desires it. We know why he wishes you to go. We have not spoken of it, but down in our hearts we know—have always known, I think. He does not consider the daughter of Marcus Grey the right girl to be his son's wife—that is so, Jack.

"Why do you shake your head? I understand quite well that he does not think it wise to welcome and approve a wife for you who has no money nor any influence nor brilliance—whose only accomplishment is that she has learned to love you so deeply, Jack. And though I feel that he is wrong, yet he is your father, and you must acknowledge his authority. I could not—I should fear to —let my love for you or yours for me estrange you and your father.

"There would never be any happiness at all for me if I caused that. How could I laugh with you, what pleasure could I find, when at each new happiness that came I should think of your father, grim, aging and all alone, embittered against you and doubly embittered against me? For he loves you. Jack, idolizes you; but all his life he has been accustomed to command men, to receive obedience from most, and respect and consideration from the highest, and so he cannot deny himself the right to exact obedience from you. Perhaps I am not very modern to be able to see it like that. I know that at school all my friends said that they intended to manage their lives for themselves, but that cannot really be the best way nor the kindest."

"NO, but old people are so hideously selfish, Isabel. If you don't see things exactly as they do, they consider that you are quite wrong and quite hopeless and foolish," he broke in.

"The old. Jack, are old—and to be old is to be so near the grave. I think that is why the young should set aside a little of their youth to consider them," she said softly, her eyes steadfast upon his. She drew closer to him, her eyes dark with pain.

"Jack," she continued m almost a whisper, "don't you see that your father is testing you? Perhaps he believes that in two years away from me you may— forget me."

He shook his head impatiently.

"I know that you wont," she went on, "and that would be your triumph and success. If you go with a good grace upon this expedition, doing what your father wants in the way he wants, and presently return"—she caught her breath a little—"and presently come back with your task accomplished but your heart for me unchanged, don't you believe that will convince your father that we are for each other, and he cannot change it? He will see that for himself and accept it. You will be able to say truly that you have obeyed him— done your best. Wont that count for something with him?"

Barhall's frown cleared as he reflected. Then, gently taking her hands, and holding them closely, he nodded and kissed her again.

"Oh, you are as clever as you are sweet and good, my dear—my dear," he said. She laughed a little; there was a quaint touch of indulgence in her laugh, such as is often in the laughter of woman at the overgrown boys called men that women love.

"That was nothing clever, Jack." she said. "It was just honesty. You would have seen it in exactly the same way if you had thought of it m that way."

They strolled slowly to the end of the wood and there paused at a stile, looking across the inland fields and talking. The night was close upon them now; through the shadowy dusk they could see, away to the right, the lights in the windows of the great house that was Barhall's home, and farther round the one lighted window of the cottage where Isabel lived with her father, a literary man, blind, who had left London with a small competence to end his days in the country.

"Oh, Jack, we must say good-by now," said the girl, her voice quivering in spite of herself.

He held her close, close, and suddenly she was weeping. He felt her trembling, and her hands were very cold in his.

GONE, all gone, was the calm confidence with which she had spoken of the lonely days she was soon to enter upon; she had been brave and hopeful then, but now her hope was gone, and her whole soul seemed overwhelmed with despair.

He was going; she had helped send him because it was right that he should go, and now, face to face with the farewell, her courage was suddenly gone from her.

"Don't—don't," he implored. "It will soon pass—two years—perhaps less."

Then, through the shadows, there floated to them the sound of a bell, clear, sweet and most musical. It was the vesper chime from a little chapel at the side of the wood; and in the still hush of the evening it came to them across the intervening pastures as if it were a low, beautiful message of serene peace and hope and tranquillity, and it penetrated most wonderfully through the grief of the weeping girl and pacified and comforted her. She listened, close in Barhall's arms, hushed, without moving, so that the tears dried on her cheeks unheeded, as the calm, ineffable music drooped over the countryside.

Then, at last, she looked up to Barhall.

"That is an omen of good. See—I am brave again," she whispered with shining eyes. Barhall too was touched a little, for there is a magical plaint about the ringing of a lone bell at dusk in the country that stirs most men and all women who pause to listen to it.

"Yes," he said, "an omen of good." He kissed her again, very tenderly, and that was for "farewell"—a longer farewell than either of them knew.

IF these are the days when there is nothing but his own disability to prevent a man from becoming rich, assuredly they are also the days when a rich man, in spite of his ability, may become poor in a moment—such a vortex have we made of the world.

So it was with Sir Henry Barhall. On the day when his party of concession-hunters, mining-engineers, highly trained exploiters of alien wealth, arrived on the western edge of equatorial Africa, be was a wealthy man and financially powerful.

And a day later he was practically penniless—his whole fortune had fallen through a crack in the earth. It was as simple in cause as it was colossal in effect.

An earthquake, seeming no more than a twitch or tremor of the skin of the earth to those who felt it at all, took place in the oil-field area in south Russia, and practically every oil-well in the area instantly went dry.

And where those billions of gallons of oil went, there too went the Barhall millions and many other millions with than. Thousands of rich men were stripped stark of their wealth that day. And not one life was lost—only the oil and the gold.

A cable, flashed south to Reade, the chief of the expedition, awaiting final instructions, dissolved that company of adventurers on the eve of its departure from the coast. Sir Henry Barhall needed to review his position before squandering an equipped expedition on hazards of the vague interior of equatorial Africa. That had been a gamble—a long shot—reasonable enough when there was money behind it, but not now. Most of the men were too good to be wasted. They could be used—if Sir Henry could afford to use them at all—nearer home.

That was how Reade interpreted the startling cable.

"We go home. Sir Henry's ruined," he said, "and pretty near every other boss in Russian oil too. Russian oil—why, there aint any! The bottom's fallen out of the whole district. Yes—an earthquake. This lets us out, anyway. Out of Africa at least—we're wanted nearer home, I guess. Africa's too big a gamble just now. Well, boys, that's 'Amen' to this trip."

WHY?" asked Jack Barhall suddenly. "I don't see why. Here is the expedition ready—everything in order. There will be fearful waste if we abandon it and nothing gained. I'm not an expert, but it's a matter of simple common sense, isn't it? I know my father rather well and that panic-stricken cable isn't like him. His nerve is gone. 1 think we should go on—as few of us as is reasonable to attempt it. The others can return."

His voice took on a metallic note, his jaw began to jut out and his blue-gray eyes went hard and stony.

The others stared, surprised. This stubborn-looking man was a very different person from the quiet, uninterested, boyish Barhall whom they had known.

But they did not know of that streak of obstinacy.

"Don't think I, personally, want to go on. I loathe Africa. It's not in my line —I'm a painter. But since we're here,—and if my father is really ruined, we sha'n't be able to do much for him if we turn back,—I think we may as well get on. If there's no gold, no oil, no precious stones at the end of it, we shall be no worse off and only a couple of years older."

It ended in five of them deciding to go on. The rest would return to England as soon as possible.

So Reade gave up the command to Barhall, together with all the plans and knowledge which hitherto he had kept strictly to himself; and a week later, Reade's contingent was homeward bound, and Jack Barhall, his five adventurers and a string of native bearers were already far from the coast en route for the interior.

SINCE this is not a story of business enterprise but rather of two women and their relations with a man, it is not necessary to detail Jack Barhall's journey up the Niger to Lokoja, thence up the Binue River to Yola and so by land to his goal, through matted jungles haunted by swarming wild beasts, fever-poisoned swamps and interminable marshes alive with snakes, great, parched desert-like tracts of waterless country; and, in amazing contrast, sometimes over huge areas of the most gracious and lovely parklike land, undulating gently, with beautiful clumps of trees and flowering shrubs, alive with antelope and game.

Nor is there room for any full account of the toll levied on that little company en route by the two grim specters that stalked unseen into the wild interior with them—disease and starvation, the forerunners of death. Nor of the obstacles —the heartbreaking obstacles—they encountered and overcame, the desertions of their natives, replaced inadequately, and with immense trouble and waste of time, by the bolder or greedier of the wretched inhabitants of the sparse villages they came upon. And when, ultimately, they won through to the great slave tracts, the districts of unnameable horrors where human life is of less account than that of a hen, it was only their modern rifles that, on three occasions at least, saved them from marauding slave-raiders.

They kept as much as possible to the River Binue. and in the end got through to Yola, on to Bifara, to Ribago, and so at last to the River Logone.

And of the six white men that started, only two ever saw the waters of that river which Sir Henry Barhall, from knowledge imparted to him by an explorer, since lost somewhere in the trackless regions of the upper Amazon, believed to flow over mud or sand that was heavy with gold.

They came to the Logone, these two,—Jack Barhall and one Hawkes, a prospector of about his own age,—and, gathering from the uncouth jabbering and signs of the natives that it was indeed the river they sought, turned instinctively to look behind them.

THE same thought was in their minds, and Hawkes voiced it.

"Barhall, we shall never get back. We've done it, but it's done us, too!" He was shaking with fever as he spoke, in rags, painfully thin, and his eyes glittered unnaturally.

Jack Barhall, in no better condition himself, turned again looking down at the river.

"Oh, I don't know. At any rate, if we do get back, we shall get back rich men—if it was the truth my father had about the gold. We might get it down to the coast by the Binue. Anyhow, we are here, and we may as well camp."

So they rested that day and the next.

On the third day Hawkes washed out a few panfuls of muddy sand from the river, and it was rich with gold, incredibly rich—so rich that Hawkes grew a little hysterical.

"Believe me, Barhall, that if this were known at home,—in America, in any civilized country,—there would be a rush to this place that would stamp the country between us and the coast flat. Klondike would he a fool to it," he said in a shaking voice. "Lord knows how far inland we are. but there are millions of men who would willingly put in a lifetime reaching the place for this." He held out a wet muddy pan with a pile of reddish yellow specks and pin-head fragments of the precious metal glittering at the bottom.

But somehow Barhall could not be infused with enthusiasm. He had won through, but now he was conscious of a weariness, of a great weariness. What was the good of the gold? Would they ever succeed in fighting their way with it back down seven hundred miles of the Binue to Lokoja and thence three hundred miles down the Niger to the coast? Why, even the trading-vessels of the Royal Niger Company only penetrated a few hundred miles along the perilous and uncertain waterway of the Binue, and they were run by men who were capable of running anything anywhere.

His teeth chattering, and his mind blurred with the fever in him, Barhall shrugged his rag-clad shoulders and went back to the camp to rest until he should be more master of himself.

It was not long before Hawkes followed him, quieter now and exhausted.

"Well, anyway, we're where the gold is," he said. "That's something. But—but—" His voice trailed off, and they sat staring moodily toward the waters of the Logone until the darkness.

Then they turned in.

IT was not until they were deeply asleep that one of the men outside—the most recently impressed recruit—rose from the porter's cooking-fire and disappeared northward into the night. When he returned, five hours later, he came guiding many men—tall, powerful men, light brown, almost golden in color, with keen, fierce eyes that shone in the dying glow of the fire. They moved silently on bare feet and were armed with short, heavy stabbing spears.

They stole into the shelter of the white men, the bearers from the slave-tracts staring with a sort of dull fear in their heavy eyes and muttering to each other.

But for all the stealth and silence of the men out of the night, their quarry was alarmed.

The staring, stupid-eyed porters leaped to their feet, shouting, as Hawkes' voice rose in a sudden sharp cry of warning, followed instantly by the harsh, muffled, metallic cough of a revolver fired close to its mark.

There was only one report. The listeners heard a swift padding trample of naked feet, an exclamation in English, silenced midway, and, after a queer, infinitesimal silence, a confused murmur of voices.

Then the raiders came out, two of them carrying the limp form of Barhall.

But the body of Hawkes they left behind them upon the floor of the shelter where it had fallen.

The porters seemed to recover their instinct of self-protection as the strange men approached, for they broke and ran into the darkness and were swallowed up and lost.

The white teeth of the strange men shone suddenly in the firelight as they smiled at the panic flight, but they did not pursue the porters. Instead, they laid Jack Barhall down by the fire, stanched a wound on his temple, and then, carrying him upon a litter made out of spears, they too disappeared into the darkness.

THE raiders bore Barhall swiftly and silently down to a place where the Logone narrowed, and there, in big canoes, crossed the river, heading eastward up rising ground. They traveled through the night with a confidence and unerring speed that was unusual even for savages. But these were no ordinary savages. Their stature, their color, their silence, and, especially, a sort of rough discipline which obtained among them, marked them as immeasurably superior to any known natives of the dense, fever-haunted regions through which Barhall had passed.

There was something remotely Arab about them, though they wore skins over their white cotton clothing.

The edge of the dawn was thinning the darkness when finally they came to their journey's end—a place of rocks, halfway up the side of what once must have been a volcanic mountain of immense size. They passed through a natural arch, so stupendously high that it could only have been formed in the side of the mountain by volcanic force, challenged sharply at the entrance by sentries, and so came out into the mighty, rock-rimmed plain that eons before had been the crater of this long-extinct monster among volcanoes.

The sun, already fierce, topped the far-off ridge that, miles away, was the eastern boundary of the crater, as the party hastened down the gentle slope luxuriant with vegetation, that dropped to a big central lake, surrounded by buildings, which gleamed before them.

It was a place of singular beauty, and unless there were many passes or rifts such as that by which the men had entered the crater, a stronghold that was impregnable to any foe unequipped with siege guns.

But Barhall saw nothing, knew nothing of these things. He lay, still and unconscious, upon the litter of spears, his face bloody from the oblique gash, now roughly dressed, that had been slashed from one temple to the other.

They took him straight to a large hut built on three sides of roughhewn blocks of lavalike rock, fitted without mortar, with a reed-thatched roof, and screened on the fourth side by a vine-grown bamboo trellis.

A FEW old men came out from the big hut expectantly as though they were prepared for the arrival, and directed the fighting men where to put Barhall. Evidently these were the physicians of the tribe.

Then, leaving Barhall, the raiders formed up into rather uneven fours and moved away toward the denser quarters lower down, nearer the lake.

They passed quickly through the crowding huts, mostly made of dried mud, rather sandy, strengthened with irregular, shapeless blocks of lava, and stiffened with rough wattles of reeds evidently embedded in the mud while it was soft. The place swarmed with people, mostly women, who called greetings to the men.

They passed through the crowded, close-packed village and bore away to the right, heading toward a big and much more ambitious and carefully constructed, square, flat-roofed building that stood upon the hillside, so that it commanded a view not only of the village but of the whole area of the crater.

Reaching this place, they passed through a wide entry and into a rectangular courtyard, floored with roughly shaped lava blocks, round which the great house was built. There they waited while their leader entered the house.

The reed and dyed-grass screens that curtained many of the windows, placed high up in the whitish walls, rustled mysteriously, as the men waited. Here and there the screens were stealthily drawn a little aside or lifted up, and women peeped out curiously. One could hear faint whisperings from behind the screens. Evidently, bare and blank though it appeared from outside, the place was full of people.

Then one woman, bolder than the others, threw back her curtain completely and stared out, her eyes roving the whole courtyard as though she sought some one. She was young, little more than a girl, beautiful in a fierce, hot, barbaric fashion, and judging from the heavy ornaments of dull gold that were on her arms and her neck, and the careful way in which her hair was dressed, she was one of some consequence in the place.

She disappeared quickly, a slight frown, as of disappointment, between her brows, when, from a door below, a man of literally gigantic stature came out, scowling at the company of spearmen in the center of the courtyard. He was followed by their chief, who was speaking hurriedly in tones of abject apology. At sight of the big man the men saluted with their spears.

THE huge man, clearly the chief or king of the tribe, acknowledged the salute with a savage glare and stepped across to them. They looked steadily past him, rigid as trained soldiers, but with that in their fixed tenseness which is not in the tenseness of civilized soldiers on parade—the taut, high-strung look that is inspired by the menace of death.

For they had done ill and knew it. They had been instructed to bring in two white men alive and uninjured, but one they had killed and the other seemed to be on the borderland.

There were no cowards among them, but nevertheless, not one of them could have returned the pale sinister stare of their master. For if they were brave men—and they were—he was braver, and they knew that. And they knew also that he was as swift to punish as an asp to strike, and crueller than death with those he designed to punish. Now in his look was rage, and long and terribly he had impressed it upon his people that his rage was madness.

He was a figure to fear—this king of the crater people—and never more than now, when he strode out, newly disappointed, to review the picked men who had failed him. Seven feet in height he stood, broad at the shoulders beyond the proportions of perfect symmetry, beautifully muscled, clean-limbed without a shred of superfluous flesh upon him. His hands and bare feet were surprisingly small. He was unarmed save for an ivory-hafted, lance-headed spear that looked a toy—no more, as it were, than the swagger cane in the hands of an English soldier. He wore upon his wrists broad bracelets of ivory, roughly inlaid with gold, and there was a circlet of some black shining wood spirally wrapped with the precious metal, set tightly round his head. Over his white, loose, linen robe he wore two magnificently marked leopard-skins so skillfully suppled that they hung soft and heavy as velvet from the leather strap crossing the left shoulder.

And his face was the face of a despot weary of despotism, a tyrant weary of tyranny, handsome enough, but set and cold with cruelty.

He spoke in a voice that rasped across the courtyard like a sentence of death.

"Which of these dogs slew the white man?" he asked.

The gaudy grass-woven curtains swayed and rustled as he spoke; many women were listening, but none lifted her screen now.

THE chief of the spearmen named a man. This one stood out from his fellows—a young man of superb physique but with a dull, rather brutal face. The mad eyes of the King played over him slowly, slowly. Sweat broke upon the man's forehead, glistening, but he stood rigid, his face set, his eyes fixed upon the wall behind the King.

"Give me the little gun," said the King. The chief handed the revolver taken from Hawkes, handling it with the care of a man trained to arms who is dealing with a new kind of weapon.

"This bold drinker of blood knew my order?" he asked of the chief.

"He knew the order, Great One," answered the chief humbly, reluctantly. The King, gripping the revolver with absolute correctness, though it was plainly the first he had handled, raised his arm.

"O Great One!" The chief crept forward, almost abject, and the King turned his pale, greenish eyes upon him. "Speak!"

"O Great One, we be few men in the tribe and many women. Year by year the spears dwindle and become less."

He ceased—mumbling. It was all the intervention he dared. The King dominated them all like a thundercloud.

Above their heads the line of curtains swayed and thrilled, as though touched by a breeze. But it was only the women craning to hear.

The King turned his eyes to the doomed man before him, as though he had not heard the low intercession, aimed and pulled the trigger.

There was a click, sharp, metallic, startling enough on that hot, tense silence, but only a click. The victim stared fixedly at the white wall behind the King, rigid as marble, his face slate-gray.

The King pulled the trigger again, and again the revolver clicked futilely.

A low chuckle, checked at its very birth, sounded from behind a curtain,—it was impossible to tell which,—and a dull color ran into the dusky, olive temples of the King, but he did not turn.

Instead he moved his left arm quickly, lithely, with a curious darting, underhand action, and in a flash the little toylike, lance-headed spear had transfixed the man before him. Then, even as the man swayed and reeled, gasping, the King leaped to him, shot his arm forward and back with a strange piston-stroke movement, stepped away, and was standing in his place, the spear withdrawn and reeking in his hand before the dead man reached the ground. It was all quick as light, as skillful as it was infamous.

AT the square-mouthed entrance to the courtyard, somebody laughed aloud. Every head jerked round, and the curtains billowed excitedly.

It was Barhall who was laughing—Barhall, stone-white, with a red-plastered brow, who sat upon a litter borne by four of those old men from the big hut by the lake.

But his laughter was meaningless—empty of everything but innocence. It was like the happy laughter of a little child that is amused but does not understand.

And indeed, that was what Barhall had become intellectually—a child, no more. The racking fevers and desperate fatigues of many months, the subtle poisons that the swamps had set in his blood, the mental strain and relentless application necessary to accomplish the task, the night surprise, the murder of Hawkes, and lastly that oblique cut across his forehead, which though neither deep, nor, if cleanly dressed, dangerous, had wrung every shrieking nerve of his body with an exquisite agony—these things, these shocks and terrors, had stripped his brain of memory as one strips off a garment.

His memory was gone, but not his mind. Physically, he could conquer the cumulation of evils, but because his mental, his intellectual, equipment was that of an artist, even, perhaps, a dreamer, his brain was shaken.

So, thoughtless, incapable of evil, utterly innocent, childlike, Jack Barhall sat upon his litter, in the blazing sunshine of the courtyard of the King and laughed at the tableau of murder as a child, ignorant even of life, might laugh at death.

THE people in the courtyard were quick to see that the white man was semi-delirious, and none quicker than the King.

Though Barhall was the first he had ever seen, the King had long known of that strange, far-off conquering race of white men that were spreading, encroaching everywhere. The remote and mighty tread of civilization already was shaking the earth at the foot of his throne. That was why the King was enraged to the killing-point when a company of picked men sent out under orders to capture without injury two of this strange race, failed so badly that they had slain one and wounded the other.

The King had been desirous to learn from the white men. He wanted them brought to the crater in order that, so far from hurting them, he might do them honor in return for their knowledge of war. He had gathered from the traitorous porter that they came for gold, and he had laughed. Gold! For centuries his tribe had washed the Logone sands fur gold. If these white men desired gold, he could give them more than they could find porters to convey to the coast. Gold was not so precious as ivory to the crater-folk—far less so than iron or steel.

And, here, for his plans was Barhall, his mind writhing in delirium, his eyes aflame with fever, his knowledge—his wonderful knowledge of war—gone.

The spearmen, still drawn up in the courtyard, blenched at the bitter bloodshot glare in the eyes of the King, as, the red spear still in his hand, he strode back from his colloquy with the old men who were tending Barhall. But men were short in the tribe, and that was good for them at that hour. He snarled a biting dismissal at them, and had Barhall taken into his own house, the palace of many curtains.

There was, of course, the possibility that Barhall would recover—the King had not overlooked that.

Indeed, he built upon it so much that, within the hour, there was not a servant or a slave ignorant of the order that the least slip, the slightest suspicion of folly or neglect in their service of the sick white man, would bring down on that one who made it a death so merciless as to make the passing of the spearman in the courtyard an easy death in comparison. That was the fashion in which the King of the crater-folk labored for his people.

But, like many kings before him, he forgot those behind the curtains—the wives, hungry for intrigue with a hunger that only the monotony of life in the harem ran inspire.

THEY were skillful enough with their simple remedies, those old men of the hut, and they quickly healed the spear-wound across Barhall's forehead. It was a longer and more tedious task to quench the smoldering fires of fever that burned in his veins, and longer still before he began to win back his strength.

At first the King came daily to the large corner room with two unglazed window openings, carefully screened from the heat and glare of the sun, where Barhall lay muttering, swamped in deliriums; but as the weeks passed, the King came less frequently. There was little to learn from a man who did nothing but mutter and cry out in a strange tongue, and the King returned to his hunting and intermittent bush warfare with the slave-raiders.

But if the interest of the King waned, that of others grew—especially of the beautiful girl who, alone of all the women in the palace, had dared to look out from behind her screen when the spearmen had returned from their raid to the banks of the Logone.

She. named Alanthe, was the last and loveliest of the King's wives, daughter of one of those old doctors at the hut, and was far too intelligent to rest content with the narrow, restricted life of the harem. She had been there less than a year, and already the King's passion for her had died out, even as it had for thirty wives before her.

Quick, fierce, accustomed to queen it over many suitors, she resented neglect, and months ago, her swift mind had begun to spin a web of mazy schemes whose ultimate object originally had been no more than to free herself from the bondage of the harem, made humiliating by the indifference of the King.

BUT her plans had led her always to one end. And that was the death of the King. Living, he blocked the way—he stood across the channel of her life as a steel and granite dam across a river. It would have been easy to escape from the palace. But the penalty for that was a terrible and shameful public death. To escape that she must leave the crater. That, to a bold and resourceful woman, was possible, yet not to be thought of, for the freedom of the limitless wilds outside would be but brief.

Out there, in those blazing areas of rumbled rocks and parched sand, or, further, the immense poisonous glooms of the matted jungles, ranged and prowled the slavers. Soon or late, they would take her, and she knew well enough that in this event she might have sacrificed the personal comforts of the King's harem for places a thousand times worse,

She was sick for escape, but she had nowhere to go.

So for many months she had brooded, alternating fierce rages with strange fits of sullen silence. The wives were afraid of her, and she despised them.

But with the coming of Barhall and her snatched glimpse of him as he was borne into the palace, her plans crystallized instantly. Here was a man, a white man, one of those conquerors of the world—a man who could tell her what lay beyond the slave-tracts, could help her win through those regions of terror, if he would.

Or better still, for her ambition was less to leave the crater than to win freedom from the cage of the King's wives, here was a man to take as husband and to set upon a throne, sharing it with herself. The idea struck upon and dazzled her swift brain as a shaft of sunlight may strike upon and dazzle one's eyes, and she stared stealthily round at the various wives who were in the great central room with her. She felt nothing but contempt for these—they were playing little absurd games, eating fruit or sweetmeats, gossiping, though Heaven knew what they had to gossip about.

ALANTHE, her eyes half closed, cat-like, lay back upon a couch and dreamed her leopard dreams of love and death.

That had been on the day of Barhall's coming.

Since then she had seen the waning of the King's interest in his captive; and, from the lips of the King, too, she had learned that the mind of the white man was even as the mind of a little child, empty of knowledge, though keenly receptive of learning.

"I think that he is mad, this white man," the tyrant told her on a day of idleness. "But that old skillful doctor, thy father, says he is not mad but lacks his memory, which will come back with his strength. What is that but madness—a memory that does not come back?"

Curled beside him on a great gaudy mat of woven grass, Alanthe answered that indeed it was a madness. But she knew her father and in her heart, believed that what he thought of a sick man and his sickness was more likely to be true than any opinion of the King's.

And it was that night when the King was bound in sleep by a drug from those her father had given her before she vanished into the harem, that she made her way, noiseless and gliding as some velvet-footed cat of the jungle, past the sleeping guard at the entry to the women's wing, and through the hot dim passages toward the room in which Barhall lay. This part of the palace was quite strange to her, but she had wormed out from the King a few sparse words as to where the white man's room was.

Once, in a deep dark recess, wholly unlighted by the dim, smoky lamp that hung farther down the passage, some one stirred and breathed heavily, muttering. She wheeled with a gasp like the spitting hiss of a cat, and her little, heavily ringed hand snatched at her bosom. A thin blade of steel, stained dark at its tip, shimmered faintly as she peered into the recess.

But a snore reassured her, and putting the dagger away, she glided on.

THEN she stopped abruptly at a square doorway hung inside with a curtain.

Some one was murmuring in the room beyond that curtain, talking low and hurriedly in a strange tongue. She waited there, listening.

Presently the voice died away, and she heard instead a little, dry cough—a sound that was familiar. That was her father—he had an old man's trick of coughing softly, unnecessarily.

Very silently she moved the curtain aside and peered in. The white man lay on a bed at the far side of the room, sleeping restlessly, murmuring at intervals, and on a stool beside the bed sat her father, staring absently on the floor, deep in thought.

She lifted the curtain and stole in.

The old man looked up, fear mingling curiously with terror in his eyes, as he recognized the girl. She raised her forefinger, warning him against noise, and swiftly crossed over to him.

"My daughter," he said in a quavering whisper. "This is death—go back—go back quickly to the queens' place. The guards—»"

"The guards sleep, and the King is weary and will not wake. There is naught to fear, my father."

She kissed the old man, submitting patiently to his eager welcome and long, affectionate scrutiny.

"Ah, beautiful one, let me look well upon thee! Thou hast become more lovely than ever before. Thou art a woman now, little one, but there is no girl so lovely as thou art. My heart is glad to behold thee once again before my time comes, even though thou hast broken the law to come here."

"Oh, my father, I am weary of the law of the palace—it is a chain about a woman's neck."

"The chain of the King cleaves not so close as the sword of the executioner, child," whispered the old man.

Her eyes burned.

"Fear not for me, unless the drugs thou gavest me at the marriage have lost their power," she said and raised her beautiful arms, stretching with a sort of feline grace, as though to illustrate her relief at even these few moments of escape from the women's quarter.

Her father laughed softly, as the aged wise laugh.

"Nay, nay," he said, "the drugs will yet have power to give sleep when I and thou, child, are dust."

"Perchance on a day to come, my father, 1 shall be in peril for lack of another drug—such a drug as will give a sleep that shall never end."

Through the dim light of the chamber the old man peered at her curiously.

"Sayest thou so, my daughter?"

There was a latent menace in his tow, reedy whisper.

"Sayest thou so? Are the. queens jealous of thee, Jewel of Mine Eyes? Do they plot against thee, whisper in corners, falling silent when thou drawest near? Strange is the pattern of the web they weave in the harems—the web of life and death. I know, little one."

He turned to a skin bag and felt therein, while the girl glided to the bedside, gazing down at Barhall. His wound had healed wonderfully, and the sunburn was gone from his face, leaving him very pale. He had become thin too, but the thinness of his face gave him a singularly fine-drawn look of race. He had always possessed good features, and despite his thinness, there was a clean look of increasing health and strength about him that pleased the girl. But it was upon his yellow, curling hair that she gazed with the greatest wonder and delight. There were no fair-haired people in the tribe of the crater.

"His hair is like gold—sunlight," she said to herself with naive delight.

"CONCERNING the drug, my child —the drug that gives a sleep without end," mumbled the old man and came to her side, showing a small case like a fancy grass-woven cigarette-case.

"Herein are dried leaves—no larger than thy least finger-nail. Yet if but one of these leaves be powdered and the powder made damp and sprinkled like bloom, upon a fruit, or in a dish of sweetmeats, or a vessel from which a thirsty woman, such as a jealous queen, a secret enemy, may drink, then the powder brings an eternal sleep."

He slipped the case into her hand.

"The sleep that is death. Look, then, I give thee this, my child, for thy protection. I love thee, Alanthe. Guard the leaves well, little one.... Child, I am an old man, thy father. Now I make my last gift unto thee, for thy safety's sake. I give thee the secret keys of death."

She kissed him.

"I thank thee, my father. And now I go. But it may be that I shall return again in the silence of the night, as now, to see thee. This white man with the sunny hair, my father, tell him of me. Thou sayest that I am beautiful—tell him of my beauty. It is a small thing" —her heavy lids drooped—"but I desire it greatly."

The old man chuckled at her vanity.

"Have no fear, beautiful one, I will speak of thy beauty to him."

"And now I go, my father. Farewell until I come again."

And she was gone, gliding through the still, stifling gloom of the corridor, past the giant harem guard, senseless in sleep, and so, phantom-silent, to the side of her drugged lord.

So Alanthe first saw Barhall and first loved him.

BARHALL had almost regained the whole of his strength before the doctors and the King realized how completely his memory was gone. If they were amazed at the extraordinary rapidity with which he picked up their language,—he was able to speak it with moderate ease before he left his sickroom,—they were equally bewildered at the little use he seemed able to make of it He would talk of things obvious—things actually to be seen—but of nothing else.

At first they attributed all this to his unfamiliarity with the language and his surroundings, but at last it was definitely impressed upon the old doctor, Alanthe's father, that the man was learning as a child learns, but with a man's brain.

When he had first struggled free from the clinging, clogging tentacles of delirium, his mind had been utterly blank—sound but blank, awaiting impressions, knowledge, exactly as an unexposed photographic plate awaits light. He learned at an incredible speed. At the end of two months he knew a good deal, but it was only knowledge already possessed by his teachers.

He knew nothing else. He who once could have astonished them all into sheer incredulity by a simple description of, say, London, or, less, a battleship, a motor, a theater, indeed anything incidental to 'civilized' life, knew less of these and kindred things, even than they of the crater did.

He had forgotten it all and had begun his life all over again, with semi-barbarians for tutors.

The old doctor tested him. "Tell me of the white men," he said, and Barhall, playing with a spear, looked at him with blue eyes, wide in wonder.

"White men—white men—" He was frankly puzzled.

It was quite apparent that he had forgotten. The old man shook his head a little sadly, as he stared at the handsome clear-cut face, the candid, innocent eyes, painfully innocent in a man of Barhall's age, muttered "He must be taught" and went in search of the King, who, bored, satiated and sullen, suggested an experiment:

"Let him be given the little gun that was strapped about his waist when he was taken, and a goat driven into the courtyard. It may be that we shall see if he hath forgotten how to kilL"

THIS they did. Barhall was sitting in the shade of a great banyan in the courtyard. He eyed the revolver curiously as the King gave it to him.

"Here is thy little gun," said the King. Barhall took it with the pleased surprise of a child presented with a new toy. It was uncannily clear that he had not the least idea of what it was.

Yet so strange and mechanically ordered a mystery is instinct that as his fingers closed about it they closed correctly upon the butt, and his forefinger curled in through the trigger guard. They watched him, fascinated. Then a black and white goat, pricked by a spear, bleated sharply and ran into the courtyard. The King jumped up with a swift, startling cry, pointing to the animal Barhall flung up his arm and fired. Unlike that of the dead Hawkes this revolver was loaded; there was a stunning explosion; the goat bounded high in the air and came down with a thud, shot through the heart

Barhall laughed delightedly, his face flushed, and emptied the revolver into the goat. Each shot was unerringly straight

But for all that it was nothing more than sheer "muscular instinct"—trained muscles automatically doing work they had done a thousand times before. This was instantly clear to the King and his doctors when, having emptied the revolver, Barhall continued to pull the trigger, scowling with disappointment because, instead of the expected series of explosions, nothing was heard but futile little clicks. He stared at the weapon blankly, puzzled.

"Thou seest, O King! The white man hath forgotten," muttered the old doctor. "Yet it is in my mind that he will remember slowly, a little and yet a little, until he hath regained all his knowledge. Meantime, he must be taught"

The King, restless, weary, already bored again, turned away.

"Let him be taught' Teach him, thou." And he slouched into the palace.

The next day he went out with half a regiment to purchase cloth from a Kano trader rumored to be at Kuka on the western edge of the great Lake Tchad. Kuka was hundreds of miles north of the crater, and the King would be gone many days. This was an unusual and lengthy enterprise, demanding as many men as the tribe could spare.

Alanthe watched the going of the King from behind her vividly dyed curtain.

BARHALL, urged and aided by his teacher, made extraordinarily swift progress to a stage of mental development higher than that of any of the crater-folk.

Within another month he used the tongue of the tribe fluently, was fairly adept with their weapons, had mastered the mechanism of his revolver, knew his way about the crater perfectly and had recaptured something of the old white instinct of command—this without realizing it. But of his life before the raiding of the shelter near Logone, he knew nothing—remembered nothing.

Finally, he loved Alanthe, with a sort of fierce, barbaric passion that in the old days would have startled him. But now in these surroundings it seemed most natural to him as to her.

Barhall had become, as it were, the super-barbarian, a rather splendid savage, with the tastes and training of a savage, fired strangely from under with the instincts of a white man.

From the secret gliding in the dead of night out of the harem to Barhall's chamber, Alanthe had advanced to greater recklessness. Much of the tense fear of the King was lifted from those of the palace with the departure of the tyrant, and Alanthe bribed enormously. The giant eunuch who dozed over his sword at the harem entrance she enriched in a week, and the freedom of the palace was hers thereafter by day and night. The chiefs of the household, the King's executioner—a post of many perquisites and much power in matters not remotely connected with his relentless official position—one by one she silenced.

Last to yield to this open break from the tradition of years was the father of Alanthe. But he too yielded on a day when, passing the harem guard he was attracted by that one's look, part of terror, part of awe. part of reluctant admiration.

THE old doctor stopped. "What is this?" he demanded. The man pointed toward the curtained arch of the harem entrance.

"The Queen Alanthe entertaineth the white man," he whispered.

The doctor was startled, terrified. The daring of it scared him. Alanthe entertaining the white man in the veiled, secret quarter of the palace where no man save the King and the eunuchs of the King had ever dared set foot!

The bought slave of the sword noted his horror and, in sheer bravado, swung back the heavy curtain.

"Enter, if thou wilt, old man," he said.

This was anarchy.

Trembling with excitement blended with terror, the old doctor passed under the arch.

"Guide me to the Queen," he said shakily, and the guard brought him to Alanthe's apartments.

On the threshold a sound of laughter checked him—a man's laughter, free, pleasant, unaffectedly gay. It rang out from the room, audible throughout the harem, where no man but the King had ever laughed before.

The face of the old doctor worked as he entered the apartment Barhall and Alanthe were there, playing with a tiny gray monkey that was one of her toys. Barhall, with one arm round the girl, was offering the monkey fruit and snatching it away as the animal reached for it. The little beast was ludicrously angry, chattering and grimacing furiously.

Then Barhall gave up the fruit, and they turned to the old man.

She saw, instantly, how it was with her father—the terror in his eyes, the shock upon his face—and spoke swiftly.

"Ah, fear not, my father—" she began, but he caught her hands, his pride in her beauty mingling grotesquely with his terror at the daring of it all.

"But I fear greatly, little one. The law—thou hast destroyed the law. Thou art a queen—" His voice quavered, and he fumbled painfully, for his gods were in the dust about his feet. "This is death."

"Even so," she said significantly.

"THE old man stared blankly, not understanding the confidence in her voice.

"When the King cometh again—" he began, and Barhall strode forward.

"When the King cometh, I shall kill him," he said simply. They gazed at the old doctor serenely. They made a remarkable match, but they were barbarians, both, splendid enough in their simple, natural, primitive passion for each other, but not more than savages. The King, when he returned, would be an obstacle between them; therefore the King must be slain.

Alanthe went deeper than that with everyone but Barhall. The King was a tyrant, unstable, cruel and dangerous. Let him be killed—alive, he was a menace against each man's life. No man knew at dawn whether he would live to see the sunset. One mistake and the King's rage would boil up about him and destroy him. Let the King be killed by any man who cared to risk the deed, and the tribe ruled more mercifully.

That was the line Alanthe took with the palace folk, bribing with both hands as she spoke. Uneasy and insecure under the reign of the tyrant, they were willing to listen, ready to support.

All this the girl gave her father in a light, fierce, breathless whisper. But the old man was too old. She was talking of destruction; she was outlining a policy of utter, ruthless annihilation; she was planning a great wreckage—that was all her fluent, confident whisper told him. And he was too old to realize anything but that this was a fearful thing. He simply stared, aghast. Behind him, at the entrance arch of Alanine's room rose a whispering, hurried, agitated, rising shrilly.

The queens were swarming in to see, to stare with a fearful, dangerous delight at the man who had invaded the forbidden wing of the palace.

THEY stared at Barhall, many of them with a sort of thrilling pitiful admiration, as they might look upon a handsome man on his way to execution. For he was doomed, as surely doomed as Alanthe. Nothing could save them when the King came again.

A man somewhere beyond the group shouted hoarsely in a tone of brutal command. The cluster of queens broke, flinching and terrified as the King's executioner strode in, a huge man of heavy, corded muscles, clad only in a loin-cloth and a scarlet turban, his naked sword in his hand.

His face was slaty with rage and terror. The queens knew—the women knew—it was impossible now to keep it all from the King. This meant a wholesale slaughter when the King came. He glared—his rage confused and bewildered him—the man was on the verge of blind indiscriminate murder himself. He had taken a huge bribe to ignore that which was to be a secret to no more than four or five,—trusted cronies of his,—¦ and now, it seemed, the whole palace knew!

He stood in the archway, stammering impotently. Barhall and Alanthe saw that he intended to kill them. Their death was to be his forlorn hope—how forlorn none knew better than Alanthe. The girl tore a long stiletto-like dagger from the bosom of her robe, her eyes narrowed to slits, gleaming yellowish, as a leopard's eyes; she shrieked a warning to Barhall.

The face of the executioner twisted and writhed into a grin, so distorted as to be scarcely human, and he balanced an instant on the balls of his feet for his rush.

"Thy little gun, beloved!" called the girl, her eyes on the executioner. It was needless—Barhall was ready.

And then another voice speared the intense silence—a voice that froze the executioner into a rigidity of terror—the voice of the King.

He had come again, at this hour of all the hours, unexpected, unknown, secretly, as was his custom.

He stepped in through the archway, and in his eyes was a fury that was madness. He stared for a second. Then, fighting for every word, he croaked his order to the executioner.

"Butcher me these dogs!"

He swung a trembling hand toward Alanthe and Barhall.

And Barhall shot him dead where he stood.

THE executioner dropped his sword and fawned upon the white man—the white savage. That is how those of the palace who came running found him, and they were swift to follow his example.

Barhall took his homage as a matter of right.

"I have killed your tyrant," he said, flushed, his eyes on the dead King, "and from now onward I will be the tyrant"

"More merciful than that one," swiftly Interpolated Alanthe. She threw out her arms to them. "Be glad, O my people, that ye have a white king. For he will teach ye many things—new arts of war, new crafts of peace. He will rule ye mercifully and make ye very wise, until, presently, we of the crater become mighty enough to issue forth from behind the rocks that have sheltered us so long, to enslave and prey upon those that have enslaved and preyed upon us these many years." Her voice rose, ringing. "Look well upon this white lord that ye take as king, my people, ere ye go forth to feast, and be proud, for there is no man of these regions who is worthy to stand beside him. He is not of our blood, truly, but that is a small thing, for in his veins runs the blood of that great race of whom ye have heard rumor—the white millions that send forth from among them the conquerors and kings of the world!"

The listeners—and now there were many—shouted approval.

"Ye desire that this white lord should be King!" she cried. "Ye do well! Behold him King, then, and bow down!"

She rang out the last words like a threat, and they humbled themselves before Barhall. "And as for me," continued Alanthe, naively in spite of the exaltation of the moment, "I am his Queen. Let the widows be sent to their homes, for now there is but one Queen, even as there is one King."

Then she waved her hands in superb dismissal, and as the curtains fell across the archway behind them, she sprang with open arms to Barhall for the kisses of triumph that awaited her.

BARHALL usurped the King's place without one dissentient whisper from the people.

And long before the first fierce torrents of gossip had cooled and fined down from gushings of random, quivering talk to cold, precise and more serious criticism, Alanthe and Barhall had launched the first of the great public feasts with which they inaugurated their rule. The stores and treasures of the dead King they opened and scattered prodigally.

If, during those lavish, wantonly wasteful days, any one of the crater-folk went hungry or thirsted, it was his own fault. Certainly no man capable of bearing arms lacked for anything—Alanthe, alert, fearless and swift, herself living in a whirl of excitement and passion, saw to that.

Nowhere was the feasting more riotous than in the palace on the hill.

The King had been a creature of moods, possessed of the devils of cruelty, pride and avarice—a cruelty that had slaked itself upon the people, a pride that had held him aloof from any revel and an avarice that had made it dangerous for any of his subjects to appear wealthy enough to give feasts. So that long before the riotous days were over, Alanthe and Barhall were established.

Here, said the people of the palace as of the town and villages, here was a king who did not go scowling and brooding, his executioner ever slouching truculently at his heels. Here was a king whose greed was not forever expressing itself in terms of new taxes. Here, said the young chiefs, was a king who did not reach out a tentacle from his palace to coil about each new beauty that was spoken of and immure her in the mysterious luxurious women's wing. Here, said the scarred fighting and hunting men, drinking deeply together, was a king who would lead them out of the crater and show them new devices of slaughter for practicing upon their hereditary enemies, the slavers of Bornu.

Everyone had praise for Barhall and, except the ex-queens, for Alanthe.

SOME one made the killing of the k' King into a sort of song—a song of hunting:

The leopard stole back to his lair

And lo! the lion was there.

There were a few pointed lines at the end about certain she-leopards that were evicted from the lair by the lion's mate.

Alanthe and Barhall heard some one out in the dark singing it near the palace one night, and the girl looked at the white man with strange, latently fierce eyes.

"There will be no more she-leopards, my lord?" she asked softly.

Barhall laughed—a great, rough, resounding laugh, very different from the laugh that the Barhall of a year before would have used. Indeed he was a different man—coarser, more brutal.

"Nay, my wife, there will be no more leopards in these empty rooms, as long as thou art on guard at the lair-mouth," he said and fondled her.

Her eyes grew dark, brooding. It seemed that the carelessness in his tone did not match her mood.

She came closer to him, and her arms slid round his neck.

"Truly 1 shall be ever on guard at our lair-mouth," she said tensely. "Yet thou art the King and what can I do against the King and the King's desire? If the hour should come when thou sayest to thyself, 'My wife Alanthe becometh old and dim in mine eyes. I am weary of her voice, and she hath no more charms for me. I will set her aside! What would it profit me, then, my lord, to place myself on guard at the lair-mouth?" Her lovely voice quivered a little; she was lacerating herself with her own jealousy, as women will.

Barhall pacified her with kisses and promises. But there was something boyish about him—a sort of carelessness, as of one whose attention might easily be diverted—that chilled the girl. She realized as clearly as any that, in effect, Barhall, as yet, probably was a boy intellectually, judged by the standards of his own race, and would need to be handled carefully if he was to remain content

SHE watched him a little wistfully as, presently, he went to the window-opening and stared out at the starlit night He was very handsome; never had she dreamed of a man so handsome, she thought, noting with secret pleasure how the curling yellow hair across his forehead hid the scar of his wound. Then she glanced round the great apartment beautiful in a barbaric fashion, with spotted skins, rugs,—some of these were exquisite Persian rugs obtained from the Arabs,—ivory things, curtains, patiently carved wood furniture and pillars. And she looked long at her reflection in a big mirror, the importing of which had cost much gold and several lives. She was beautiful, also—her mirror told her that. But her heart knew that Barhall was not a man who could content himself long with beautiful apartments and a beautiful wife. Those were only a small part of such a man's life.

Was he not one of those white conquerors who were sweeping steadily but surely across the whole earth? She knew that such an advance was not accomplished by men who were to be held for any long time captive to love. Watching him, she realized that there were bound to be other and greater interests for him than love, whether he remained as he was, a barbarian, one of the crater-folk, or whether he regained that memory of the past which so mysteriously had been blotted out of his mind.

In any case there would be soon the fierce delights of war luring him from her side—red war, swift raidings, subtle, murderous ambuscades, expeditions, sorties, all those savage, fatal, blood-stained joys which were part of the life of every man of the crater. And there was the hunting, the trading and bartering, the feasting and drinking with the fighting men who already were looking to him to lead them out against their ever-present enemies, the slave-raiding tribes, and above all, the slaves that he might capture—girls, perhaps beautiful.

That, all that was inevitable, even though the white memory and with it the white knowledge, skill and ambition never came back to him. And if it did, if he suddenly became in mind the white man he was in body, what would happen? Would she still be beautiful in his eyes? Would he remain with the crater-folk or go back to his own people?

She drew in her breath with a little gasp.

Then Barhall turned from the window.

"I will go out to hunt to-morrow," he said.

"It is good, my lord," said Alanthe quietly. She had suddenly lost her fear of the counter-attractions of war, of hunting, of the beautiful slaves that he might capture. All that she might combat in her own way at the right time. It was not these things that would lose him to her—it was the return of the "white" memory she feared now. The possibility of it opened up in her mind a vista that was incredibly confusing and full of strange doubts.

"It is good, my lord," she said and sent for the chief hunter of the dead King.

THEREAFTER, during weeks that lengthened into months that drew on into seasons, Barhall took his fill, and more, of the limited and primitive delights that were his for the taking. He ruled the folk of the crater partly as a spoiled child and partly as a satiated autocrat in search of new sensations might do. He used his kingship as a toy mostly, but sometimes as a scourge.

A knack for bush warfare, certain lucky victories, and an extravagant habit of rewarding them, retained for him always the affection of his fighting men; but it was not long before the rest of the people began to whisper it among themselves that the savage, ruthless certainty of the dead King was to be preferred to the feverishly shifting, ever-changing ways of this white man.

In the old days a sort of grim justice had obtained in the crater when one ventured to appeal to it. But this white king's judgments were given without regard to justice. A pretty face, a broad joke, a timely lie—any such matter would sway his judgment like a reed in the wind. Sometimes he would not trouble to judge their quarrels and claims at all—would laugh and send them away unheard.

Their taxes—of labor and goods—were raised when he began to build a bigger palace, though the half of his present palace was empty.

Soon after the palace was begun came the time when he began to lapse into strange fits of black brooding, when he would sit still as stone, his brows knotted painfully over blank and lifeless eyes that stared into space for hour after hour, and presently, day after day. They could see him at it, for he had a favorite spot on the ridge of the crater from whence he could look down upon the town from a height, like an eagle or a vulture.

They would look up and see him there, and look away again uneasily. Only Alanthe could deal with him at these times. He would emerge from his brooding with strange and agonizing pains in his head, and then the palace would become a very tomb of silence, for any noise drove the King frantic. It was during one of these bouts that he ordered his first execution and set up his executioner. A forgetful slave, crossing the courtyard outside, laughed in his hearing, and he glared from the window-opening like a man demented, called up the guard on duty at the entry to the court and had the slave speared. This guard he made his executioner.

Later he discovered that he could allay his pains with a crude, fiery spirit that the poorest of the people distilled and drank; and so the terror of the King in pain yielded to the terror of the King drunken—which was worse.

ALANTHE took over his duties one by one, and that lessened somewhat his headlong fall from popularity; but his power remained untouched.

He developed a queer cruelty that grew until it matched and passed that of the tyrant he had succeeded, and he instituted a sort of primitive arena with combats between men and men, men and wild beasts.

Then he complained that the sunlight of the daytime was too fierce and white and blinding. It hurt him, and he took to sleeping by day and living at night,

There were strange doings in the crater at that time,—weird and terrible fights in the moonlit arena, as when he set twenty captives, cannibals of the Bakuba tribe, to fight with light-throwing spears an old bull rhinoceros he and his hunters had taken in a pitfall. The moon went down behind the crags before that fight was ended, for when the Bakuba men were all destroyed, it took fifty of his best hunters and soldiers to kill the squealing monster that, stabbed with futile spears, still stamped and plowed and thundered, unconquered, across the shambles of the fight.

And he ordered all executions to be carried out at night and attended each one.

But through all her perplexity, disillusionment, blank disappointment, and a growing desire to see in him even one attribute of that far-off, greatly famed white race, Alanthe clung to him.

Bloodshed she was used to, and tyranny and cruelty were commonplaces to a woman who had dwelt in the palace of the old King.

At last Barhall began to fill again those rooms in the women's wing that had so long remained silent, empty and deserted behind their screened and curtained windows. Every beautiful captive brought into the crater, every beautiful girl his glance lighted upon in the town or outlying villages, he had brought to the palace.

Alanthe, protesting, was answered by a stupid, questioning stare as though he asked what it mattered. Then he turned and went from her. She found herself still chief wife and possessed of a power that, though more quietly, secretly and differently used, was equal to that of the King himself.

With this, for the time, she rested content. It was plain to her, as to others, that an end to the King's excess was not far. His dull, uncomprehending eyes, his haggard cheeks, the fearful and ever-increasing attacks of pain in his head—all spoke eloquently of this.

Soon, she saw, he would be sick, and if he did not die, he would return to her by force of circumstances. With that she must be content. She loved him. If he turned from her in health, she must endure that. But in sickness she could claim him and nurse him—there were none, not even the King himself, who could take that from her. It was not what she had visioned when they first loved, but it was better than nothing at all.

And the end was nearer than she dreamed.

WHEN the reign of the white King had become well-nigh intolerable to everybody, the end came very swiftly.

There had been a great raid, an exhibition of a fortnight's duration, with a savage fight at the end of it, a victory for the crater-men led by the King, the capture of many women, men and cattle. The feast of the returned fighting men had extended spasmodically over several days and was to end with a great arena-fight in the moonlight between some thirty of the captured men and an old "rogue" elephant that had been skillfully driven into the arena from outside the crater—a feat which in itself had taken scores of the most skillful and patient hunters of the tribe a week to accomplish.

On the day that preceded the evening of the great slaughter—for the wretched captives could hope to do nothing with their light spears against the raving beast whose trumpetings were echoing almost incessantly across the crater—the King endured the worst bout of pain he had ever before known. It seized upon him so that, it was whispered down in the town, he had screamed aloud till the palace rang with the sound of it and the women and slaves, blanched and shuddering, cowered in silence at their places, not daring to speak or to move.

Alanthe was with him, unafraid, able to do little to relieve him, but doing what she could. None of the drugs known to the doctors would hold him unconscious except those that would have held him so forever—the poisons.

The scar of the spear-wound across his forehead had turned crimson, and it was this that seemed to be the root of the pain—that, or its effect upon his brain.

But with the setting of the sun, the coming of the night and presently the cool light of the moon, the pain lessened and died out and Barhall remembered the arena. He ate and drank and went out with his wives to see the fight. Alanthe went with him and took the place at his right hand which in public she had never yielded

THE steep rocks surrounding the arena were thick with people who had come to see the spectacle. The sound of their voices, as they climbed here and there seeking comfortable places, was like a low, long-sustained drone in the night. There was nothing of pity in their talk for the unfortunates awaiting death in a guarded den near the arena, for these were hereditary enemies of the crater-people, and it was good that they should be blotted out

It was the law of the crater, even as it was of the jungle—"conquer or he conquered; kill or be killed"—the old, primitive law of the Stone Age, of all ages, even down to this age, even in this country, where the only modification of the law is that the weapon of the conquerors and conquered is money.

The great African moon, hanging low above the encircling ridge of the crater as yet, shed an eerie radiance on the scene; and the weather-carved crags cast monstrous and fantastic shadows across the earthen floors of the natural arena where the giant elephant stood with his great ears thrust forward, huge snaky trunk swinging and writhing and twisting, his tusks showing white in the light of the moon.

Once the big beast trampled across and paused exactly under the place where the King sat with Alanthe and his bevy of wives, curled up his trunk and uttered the strange, painful brassy sound that is known as "trumpeting."

The man who had been Barhall stared down dully, his face so haggard that the shadows under his cheek-bones were inky black, his brows knotted with the pain that was still ebbing slowly from behind his forehead The queens giggled softly where they clustered, excited by the strangeness of the hour, the noise, the uncanny light and the sensation of the coming combat

But Alanthe, aloof and cold at the right hand of the haggard man who was King, sat silently, brooding, puzzling, at odds with some dim instinct which told her that it was not thus that the white rulers of the world pleasured themselves and their people, or punished enemies fallen into their hands. She did not know why, but it seemed to her that there was something in the atmosphere of this orgy that was evil-tainted. She did not feel any special pity for the victims, for she had not been taught to pity fallen foes, but she knew that all was not well with the mind, the soul, of the man who could devise the spectacle.

"LET it begin," muttered Barhall, and a captain of the guards shouted across the arena.

A clamor of horns blared and brayed discordantly; the spearman at the hut of the prisoners became suddenly active, and the swarming watchers settled themselves intensely to miss no detail.

The doomed men emerged from the hut quickly, were hurried through a line of guards to the rough but immensely massive entrance of the arena, and the great timbers pushed back into their slots. Spears were thrown to the victims, and as they stared, bewildered still, a thousand voices roared down at them from the shadowy rock-tiers, bidding them fight

The elephant swung round, facing them, and they saw, huge, terrifying, seeming monstrous in the fantastic light, the thing they were called upon to fight.

They cowered together in a close group for a moment, but as the big beast thundered down upon them, broke up and fled. A few threw their spears, unerringly enough but with no effect other than to increase the fury of the elephant. But for all his madness the mighty killer was cunning and as quick as he was cunning. The lashing trunk curled about a man at the first rush, dashed him down, shrieking thinly, the terrible tusks pinned him, and in an instant he was dead under the knees of the elephant. His comrades made no effort at rescue. Half of them were now without spears; they struck, rattling oddly, in the dry hide of the elephant. Any effort at fighting died out at once; the frantic wretches ran dumbly, seeking, like frightened rats, to find some dark cranny in the rock wall hemming them in, where they might hide. All save one—some sort of chief among them. This man, a puny figure against the overwhelming bulk of the beast, walked fearlessly up to where the elephant was slaking his dreadful fury upon the body of the man he had just killed.

He avoided the swing of the trunk, ran round and darted in, thrusting desperately with the spear he had retained at the eye of the elephant But save to inflict more pain, he achieved nothing but his own annihilation, for the great trunk curled back like a vast, powerful spring, coiled about him; and, rising from his knees, the elephant, trumpeting wildly, flung him high, across half the width of the arena, so that he was dashed to death on the rocks at the very feet of Barhall.

BARHALL stared down at the body, and it was at that instant that his memory first returned.

He started shockingly, as a man frightened suddenly from deep sleep may start, and rose slowly from his seat, both hands pressed to his head. Down in the arena the great elephant, blowing through his trunk, was hunting busily in the crannies, dragging out the concealed men from their hiding places and killing them with a sort of dreadful and relentless dispatch.

But those about Barhall no longer had eyes for the killing—it was at the white man that they stared.

He was looking down into the arena with horror on his face.—horror and despair,—like a man unable to credit what with his own eyes he sees.

Alanthe was the only one of them all who understood.