An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Between 1904 and 1918 Edgar Wallace wrote over 200 mostly humorous sketches about life in the British Army relating the escapades and adventures of privates Smith (Smithy), Nobby Clark, Spud Murphy and their comrades-in-arms. A character called Smithy first appeared in articles which Wallace wrote for the Daily Mail as a war correspondent in South Africa during the Boer war. (See "Kitchener's The Bloke", "Christmas Day On The Veldt", "The Night Of The Drive", "Home Again", and "Back From The War—The Return of Smithy" in the collection Reports from the Boer War). The Smithy of these articles is presumably the prototype of the character in the later stories.

In his autobiography People Edgar Wallace describes the origin of of his first "Smithy" collection as follows: "What was in my mind... was to launch forth as a story-writer. I had written one or two short stories whilst I was in Cape Town, but they were not of any account. My best practice were my 'Smithy' articles in the Daily Mail, and the short history of the Russian Tsars (Red Pages from Tsardom, R.G.) which ran serially in the same paper. Collecting the 'Smithys', I sought for a publisher, but nobody seemed anxious to put his imprint upon my work, and in a moment of magnificent optimism I founded a little publishing business, which was called 'The Tallis Press.' It occupied one room in Temple Chambers, and from here I issued "Smithy" at 1 shilling and sold about 30,000 copies."

Link to complete list of Smithy and Nobby stories.

The present volume contains the last 12 stories in the 24-part series that Wallace wrote for the London weekly Ideas under the title The "Makings-Up" of Nobby Clark.

WE were talking about Luck, and the uncertainties thereof.

"Me father," said Nobby Clark, with a touch of pride," is one of the greatest card players of the age. He got quite a reputation for it. He played on a system. When he came into a game, the other people used to get up an' go away.

"'What?' sez me father, 'goin' already?'

"'Yes,' one would say. 'I promised me wife I'd be home by 10.23. an' I can just do it.'

"'Stop an' have a game,' sez father, very urgent.

"'Very sorry,' sez another chap, 'but I hurt me hand hittin' a policeman, an' I've got writer's cramp—'

"'Besides,' sez another feller, 'you're too lucky for us.'

"'What do you mean?' sez me father.

"'Oh, nothin',' sez the chap, careless, 'only I've noticed certain things, that's all.'

"'If you'd oblige me with the name of your solicitors,' sez me father, 'or if you've got a friend who'll hold your coat, we will settle this matter in two twinks!'

'If you'd oblige me with the name of your solicitors,' sez me father, 'or if you've

got a friend who'll hold your coat, we will settle this matter in two twinks!'

"With that, the feller would back out, sayin' that he didn't mean what father meant, an' as no offence was meant, no offence should be took.

"'Very well, then, sez father stern, 'you can prove your word by sittin' down again an' playin' a hand at nap.'

"An' generally the chap would sit down.

"Everythin' would go quiet for a bit; then somebody would say:

"'How many aces of spades are there in this pack?'

"'Lets have no unpleasantness,' sez me father, shufflin' the cards very quick.

"'But I had the ace of spades, an' you had the ace of spades,' sez the feller, not to be put off.

"'Accidents will happen,' sez me father, very magnanimous, 'an' I don't harbour any suspicion against you. It's your deal; I dealt last time.'

"'You did,' sez the chop, very significant.

"Then there'd be another long silence, broken only by the sound of father sayin' 'nap' an' gettin' it. Bimeby—

"'Hold hard,' sez the other feller, 'that's my trick.'

"'What is?' sez me father.

"'I took your trick with the king of hearts,' sez the feller.

"'That's curious,' sez me father, puzzled, 'especially as I've got the king of hearts in me hand!'

"'There's somethin' wrong somewhere,' sez one of the players.

"'It's a misdeal,' sez father very calm. 'It's your deal, Mr. What's-your-name—I dealt last time.'

"'You did,' sez the chap more nastily than ever.

"Then father would, perhaps, rake in two or three naps in succession, after which he'd get up.

"'I've finished,' he'd say. 'I've got to catch a train to—where is it?'

"'Stop an' play another round,' sez the nasty man; 'don't sneak away as soon as you've packed up a parcel.'

"'No,' sez me father, very firm, 'I've promised me wife I wouldn't lose more than a sov—'

"'But you haven't,' says the chap, indignant; 'you've won,' he sez, chokin'.

"'So much the better,' sez me father, an' that's the end of the argument.

"Or, perhaps, things wouldn't come his way, an' then one of the other fellers who'd been winnin' would get up an' say he must be nippin'.

"'What for?' sez me father, indignant.

"'It's gettin' on,' sez the feller lookin' at his watch, 'why, it's half-past eleven!' he sez, very shocked.

"'You sit down,' sez me father, stern, 'you don't suppose I'm goin' to let you walk away with all that unearned increment, do you? Sit down, or I'll hand you a parcel of trouble*

"So the feller sits down, mutterin' an' grousin' an' lookin' at his watch all the time.

"But after father's pipped him twice on a nap call, an' after the money begins to flow steadily over to father's side of the table, he doesn't take any more interest in time, an' when father gets up from the table at 2 a.m an' gathers up his winnin's, the feller gets wild.

"'Goin'?' he sez to me father.

"'I am,' sez father.

"'The night's young,' sez the feller.

"'But I ain't,' sez me father, 'not so young as I was. Besides I've finished my system.'

"'You've won all my money!' sez the feller.

"'That's what I moan,' sez me father, an' before the chap could recover his breath father would be homeward bound with a list to starboard—he always carried his winnin's in his right-hand trousers pocket.

"Now, the lesson I learnt from me father," said Nobby, "was this: Luck is nothin' more or less than the savvy to stop playin' when you're a winner, an' not to stop playin' until you are. An', moreover, he was the only chap I know who had a system that worked.

"Yatesey, that feller I was tellin' you about the other day, was one of them chaps who always take risks when they can't afford to, an' who always starts cuttin' their losses just as the profits come in sight.

"Naturally enough, he never made money. He was a 'G' Company man, an' I never saw him except at the canteen or in town, so that I never properly got to know him till he an' me was on detachment together at a place called Simonstown at the Cape.

"He was a rare chap for racin' an' for systems. He invented a system for winnin' money, an' went down to Kenilworth Races an' tried it.

"'It worked fine,' sez Yatesey when he came back, 'if I could have only lasted till the last race an' had £7,473 10s. 4d. on Butcher's Bride I'd have cleared all me expenses, an' made a sovereign besides—as it is, I've lost 12s.'

"Yatesey had the same opinion as me father, an' that was, that there was no such thing as luck.

"'It's information an' judgment,' sez Yatesey. 'All you've got to do to win money racin', is to read the newspapers very careful; peruse, if I may use the expression, the trainin' reports, an' there you are!

"Before a big race, he'd get the 'Cape Sportsman' to study it. Sometimes he'd read bits out to me.

"'Now listen to this,' sez Yatesey, 'here's what I call a clear an' clever summm'-up of the situation.'

"Then he'd read:

This great race is down for decision on Saturday, an' a spirited an' excitin' contest is promised. With a splendid service of trains an' good weather, an enjoyable afternoon's sport is certain The following' are the probable

Lord Raspberry's Cabbage Patch by Lonely Furrow —G1asgow 4ys 9st 3lb... Wiggs

Mr. Redfern's Foolish Error by Censor —Folly 4ys 9st 1lb... Madam

Mr. Eustace Smile's Kitchen Garden by Racquet —Greens 3ys 8st 1lbs... Little Makery

Mr. Peary's Polemic by Gascooker —Hot Time 3ys 7st 6lb... Lynchem

With to so small an acceptance list it is possible to dismiss the race in a very few words.

Some doubt exists whether Lord Raspberry candidate can stay. Our own opinion is, that if he can he will. On the other hand, he may not; but, at any rate, he must he a danger.

Kitchen Garden has form to recommend him, an' on this easy course he will take a lot of beatin'.

Foolish Error is another that appeals to us, an' we quite anticipate his victory, for a difficult course like this will just suit the far-stridin' son of Censor. Considerin' all things, however, we can see nothin' that will beat POLEMIC

though we tip this horse without any degrees of confidence.

EPSOMDORP (from our own correspondent). A glorious mornin'. Cabbage Patch cantered, an' although runnin' a little green, impressed all beholders. This handsome colt will about win the Kenilworth Handicap.

ASS VOGELFONTEIN (from our own correspondent). A rainy mornin'. Mr. Redfern's candidate. Foolish Error, has had a perfect preparation for the Kenilworth Handicap, an' I fully expect him to be returned a winner.

FREEZEFONTEIN (from our own correspondent). A nice mornin', but cold. Polemic had a capital gallop through the snow, an' pulled up as fresh as an ice floe. He is in capital fettle, an' will about win.

HARRICOTVLEI (from our own correspondent). A foggy mornin'. Kitchen Garden was given a windin'-up gallop. This remarkable three-year-old can hardly be beaten in the Kenilworth Handicap.

"Then Yatesey finished readin' he'd start all over again, as if he wasn't sure which horse to back. That was the rum thing about Yatesey; he did not know a tip when he saw one.

"But systems was his great lay.

"He often used to invite me to go racin' with him, an' I offered to go, but when he told me that I'd have to pay my own expenses, I backed out.

"But one day he comes to me.

"'Nobby,' he sez, 'if I got you a ticket will you come racin' on Saturday?'

"'I will,' I sez, an' he told me that he wanted to do me a bit of good.

"'There's a horse in the first race,' he sez, 'that's money for nothin',' he sez.

"'It's usually the other way about, ain't it?'

"But Yatesey ain't much of a humorist, an' my little joke didn't get the cocoanut.

"The great thing about racin', accordin' to Yatesey, at to know somebody in a stable. It didn't matter who it was, or what kind of stable it was, so long as you know him well enough to speak to.

"Yatesey told me all about it in the train goin' down to Kenilworth.

"'That's where I've got an advantage,' he sez, 'over the public; it ain't fair to the bookmakers, I'll admit, but, after all, I can't consider bookmakers, can I?'

"I sez 'No.'

"'I'm goin' to work my owners for courses system to-day,' sez Yatesey, 'so I think we'll give the bookmaker a bit of a shakin' up.

"'We've got to look after ourselves,' sez Yatesey very firm, ' it's no good havin' a tender 'art when you go racin', is it?'

"So I sez 'No' again.

"We got to the course an' in we went.

"I couldn't help feelin' sorry for the bookmakers. There they was shoutin' an' jokin' so light-heartedly, an' not one of 'em with any idea that Yatesey knew the first four winners, right off the reel. I pitied 'em—I did, upon me word. Nice, homely fellers, doin' their best to earn a little money to take 'em back to their dear ole homes in far-away Jerusalem.

"But Yatesey was hard-hearted.

"He took me away into a quiet corner.

"'We'll back "Do-Be-Careful" in this first race,' he sez; 'his owner likes to win here, an' besides, he's got a stone in hand.'

"'Which hand?' I sez, but Yatesey wouldn't let on. He wanted me to go shares with him in his bet, but I wouldn't—I was too sorry for the gentlemen in the loud suits.

"We went up into the stand to see the race run.

"'They're off,' sez Yatesey; 'there's the horse we've backed—he's last now, but that's only the jockey's artfulness.'

"The jockey was so artful, that when the horses came past the post he was still last, only much more so.

"'That's very curious,' sez Yatesey, frownin' heavy; 'the lad in Bogey's stable said it was a stone pinch for Do-Be-Careful.'

"'How much did you back it for?" I sez.

"'Two bob,' sez Yatesey, mournful.

"'Somebody must have seen you gambling,' I sez, 'an' nobbled the horse.'

"When the numbers went up for the next race Yatesey began to get cheerful.

"'We'll get back all we lost on this,' he sez. 'Mint Mania is, in a manner of speakin', a squinch. He'll win in a walk.'

"An' so he woold have," explained Nobby, "only the other horses didn't happen to he walkin', an' Mint Mania was passin' the winnin' post when the horses was goin' out for the next race.

"There wasn't any better luck for Yatesey in the third race, nor the fourth race either. But Yatesey wasn't what you might call depressed.

"'The beauty of bein' in the know,' he sez, 'is that you can always get out on the last race.'

"'Don't they open the gates till then?' I sez.

"'What I mean to say is, you can always make money on the last race,' an' then he explained to me that public-spirited owners always kept a certainty for the last race to give the public a chance.

"'So,' sez Yatesey, 'I'm goin' to back Old Jim.'

"Goin' home that night Yatesey was very silent, because Old Jim had only finished fourth. We'd waited a bit, hopin' that the other three would be disqualified (there was tour runners), but a feller, who was probably in league with the bookmakers, shouted 'All Ri-et!' an' we come away.

"'This,' sez Yatesey, very hitter, 'shakes my faith in owners.'

"That night after I'd got to sleep, I was wakened by Yatesey shakin' me.

"'Nobby,' he sez, 'perhaps I've done the owners, in a manner of speakin', an injustice. Perhaps the owner of the winner was the public-spirited feller. Now I've got a bit of a theory which we'll try next week. I'll back the first favourite in the first race, the second favourite in the second race, the third—'

"I didn't hear any more because I went to sleep."

"NATURALLY enough," said Private Nobby Clark, "a feller owes a lot to his early trainin', an' a wise father makes an artful son, as Shakespeare says.

"Me father wasn't always wise; sometimes he was otherwise; but he was generally to be found hangin' round when things was bein' given away, an' if that ain't wisdom, it's good business.

"Me father was a great politician. Used to speak at all the public meetin's, an' be reported, too. Sometimes he wouldn't be there very long, but generally he used to get to a place where the stewards couldn't reach him. Father was what I might call 'a voice.' Suppose it was a Home Rule meetin', an' Mr. Balfour was talkin'. It'd go somethin' like this:

"'Mr. Balfour: What I say about Home Rule is this...'

"'A Voice: Go home!'

"'Mr. Balfour: If you give Home Rule to Ireland, what about Scotland?'

"'A Voice: What about the Isle of Dogs?" (Laughter an' uproar, durin' which the speaker was ejected.)

"Father hadn't what I might call any political convictions; he had other kinds, but not political, so that made it easy for him to take what he used to call an intelligent interest in politics. There was a time when he was the most run-after man in our neighbourhood.

"One of the big political chaps would come round to our house.

"'Is your husband at home, Mrs. Clark?' he'd say.

"'No,' she'd say.

"'It's all right,' sez the political chap, 'we ain't police, we're politics.'

"'You'll find him in the tennis court,' sez mother, and they'd go through the kitchen into the backyard to find father very busy paintin' the rabbit hutch with some paint he found outside the oil shop.

"'Now, Clark,' sez the political feller, 'we shall want you for a show to-night.'

"'Liberal or Conservative?' sez me father.

"'I forget for the moment,' sez the political chap, 'the feller who's goin' to speak ain't made up his mind on the question—but all you've got to do is to put in a few well-chosen remarks, such as "You're a liar," "Fry your face," an' similar statements.'

"Father went: It was the last political meetin' he went to for a long time. It appears be went to the wrong meetin'—there was several bein' held that night—an' owin' to his political questions such as 'Why don't you marry the girl?' the assembly broke up in great confusion.

"When father went to draw his pay—five shilling —he found the political chap waitin' to pay him—with a coke-hammer.

He found the political chap waitin'

to pay him—with a coke-hammer.

"'An' my advice to you, Clark,' sez the feller when he called to see father in hospital, 'is to keep clear of politics. You ain't cut out for it: you haven't got the build, nor the constitution, nor,' he sez, 'the sense.'

"'I see your meanin', Mr. What-d'ye-call-it," sez me father, 'an' when I come out I'll chuck politics away from me.'

"An' so father did, in a highly dramatic way, wrappin' a brick in a bit of Lord Rosebery's speech an' droppin' it on the head of a political feller when he was passin' under our winder one night.

"I've always follered father's lead, an' given politics a rest, though that's no hard thing for a soldier to do, because in the Army politics ain't allowed—or wanted either.

"We had a political officer once, a chap who got seconded or somethin' for the Army, an' that was about the only time the regiment ever took politics seriously. Most of us were Conservative, the same as Captain Kinsley, but Spud Murphy, who had a down on the officer, went the other way about.

"'I'm a Socialist, I am,' sez Spud. 'I believe in dividin' the wealth, if I may call it so, of the world, an' lettin' every man have his fair share.'

"'An' what do you call a fair share? I sez.

"'As much us I can lay me hands on,' sez Spud.

"But when election day came round, an' the Captain was elected by 2, politics died down again, until a foolish young feller by the namr of Flank—Mr. Thos. Flank—started' a debatin' class at the Young Soldiers' Mutual Improvement Society in town.

"It didn't look like politics at first, because the things they used to talk about was such things as, 'Should Sunday be a day of rest?' or 'Is it better to be clever than beautiful?'

"Then some feller started a discussion, 'Should bicycles be taxed?' an' gradually we went on by easy stages until we'd got to 'Ought the House of Peers to be abolished?'

"There was a fine argument over this, nearly all the members of the Soldiers' Mutual Improvement Society takin' part, bein' under the impression that the 'House of Peers' was a public-house, an' we voted solid in consequence.

"But takin' one thing with another, politics always missed fire in the Anchesters, an' it wasn't till the year before the war that they ever filled what I might call the public eye in our battalion.

"The only chap that politics ever stuck to was Spud Murphy, who, havin' become a Socialist owin' to Captain Kinsley givin' him ten days' C.B. for absence from duty, was took bad with Socialism at the time of the election, an' remained in a critical state ever afterwards.

"Spud didn't know much about the game when he started Socialism', but it's wonderful what you can pick up, an' what with readin' one paper an' another, Spud got worse an' worse, till he'd sit for hours in the canteen—specially just before pay-day—an' argue that our beer was as much his as it was ours, an' callin' me an' Smithy all the capitalists he could lay his tongue to.

"'It ain't the beer,' he sez, bitterly, 'it's the bloomin' principle I'm after;' but me an' Smithy used to sit holdin' tight to our principles an' not leave go until we'd drank every drop of 'em.

"'What I want to point out is this,' sez Spud, 'is that bein' a true Socialist, I'm willin' to share my beer—can 1 say anythin' fairer than that?"

"'You haven't got any beer,' sez Smithy.

"'That may be or may not be,' sez Spud, 'but it don't affect the question.'

"'It affects the beer,' sez Smithy, who ain't what you might call imaginative.

"'You can't argue a question out,' sez Spud; 'you've got no logic'

"'I've got the beer,' sez Smithy, 'an', what's more, I'm goin' to keep it.'

"When pay day came round, an' Spud was flush, we'd try to catch him out, but Spud was the artfullest chap in barracks.

"He could prove to you as plain as plain, from bits he'd read in the papers, that if he added his money to yours an' divided it, he'd still be a loser.

"'True Socialism,' he sez, 'is not to take money from people who need it, but to take a from people who don't want to part with it.'

"An' it took me an' Smithy an' Tiny White, an' Corporal Timms two days to work out what he meant.

"He explained a bit later that if he came into a fortune of a million pounds or so, he would keep the 'or so' an 'share' the rest amongst his sufferin' fellows, because what comes to you by luck ain't rightly yours.

"But all Spud's theories went to blazes one fine day.

"Anchester Fair an' Cattle Show was on, an' all the waste places round Anchester was filled with swing-boats, an' roundabouts, an' coconut shies, an' similar agricultural exhibits.

"I never saw the show part of it, nor nobody else either, but the whole blessed regiment used to turn out every night, an' go down to the show grounds. What with seein' movin' picture shows, an' playin' chuck-the-ring, an' tryin' to knock the pennies off the billiard ball, the regiment spent all the money it had—it was the beginnin' of the month, too—an' the only feller who did any good was Spud. There was a sort of cheap-jack who was rafflin' Stilton cheese, a penny a ticket, an' Spud was one of the last winners.

"It was the final day of the fair an' we were walkin' round the show ground, me an' Smithy, discussin' the amount of beer we could have bought with the stuff we'd wasted, an' wonderin' where the money was comin' from to buy extras[*], when we came flop upon Spud in the moment, as the poet sez, of his touchin'.

[* Extras are the luxuries of the barrack-room table.]

"It was a fine big cheese, as much as Spud could carry. There was enough cheese there to last the whole bloomin' company till next pay day, so I up an' congratulated Spud.

"'I'm glad,' I sez very hearty, 'to see you walkin' off with this what I might describe as unearned increment under your arm. Because,' I sez, 'knowin' your kind Socialistic heart, can see you dividin' it amongst your comrades.'

'I'm glad,' I sez very hearty, 'to see you walkin' off with this

what I might describe as unearned increment under your arm.'

"'If you can see that,' sez Spud, nasty, 'all that I can say is that you must have been drinkin'.'

"'I can see him,' I sez enthusiastic, 'callin' his true friends together—his brother Socialists, like me an' Smithy—'

"'It might as well be said first as last,' sez Spud, very firm, 'that this ain't a Socialist cheese; in a manner of speakin', it's a monopoly.'

"'Do you mean to tell me, comrade,' sez Smithy, 'that you're goin' to eat this cheese on your own?*

"'That's me meanin', comrade,' sez Spud, very cheerful.

"'Then,' sez me an' Smithy together, 'I hope it'll choke you.'

"Spud staggered home with his cheese, took it up to the room, opened his box an' put it in.

"Next mornin', when me an' the rest of the room was eatin' barrack rations, there was noble Spud with a whackin' bit o' prime Stilton, an' although me an' Smithy looked at Spud in a way that would have melted a heart of stone, we didn't melt any of the cheese from his plate to ours.

"It was fairly maddenin' to see him go to his box, open it, cut off a bit as big as a pavin' block, an' come calmly to the table to eat it.

"This went on for three or four days an' we got used to it, though I could never get used to seein' Spud sittin' down, an' talkin' with his mouth full of cheese, argue that the ruin of England was the selfishness of the upper classes.

"Then one day, the company officer, comin' in to make an inspection, stopped in the middle of the room an' started sniffin'.

"'That gas is escaping' he sez; 'tell the quartermaster-sergeant.'

Over came a barrack labourer an' started tinkerin' with the gas,, but after makin' various experiments he sez that the only gas that was escapin' was out of the officer's head.

Next day in came the commandin' officer on barrack inspection.

"'Hallo,' he sez, stoppin' dead; 'what's wrong with the drains?'

"An' everybody started sniffin'.

"'Send for the medical officer,' sez the CO. 'there's somethin' radically wrong here.'

"Poor old Spud's face got longer an' longer while the officers stood waitin' for the M.O., an' what with all the other chaps in the room lookin' accusin'ly an' very stern at him, he began to tremble in his shoes.

"'It's a very curious smell,' sez the doctor when he arrived. 'I can't quite understand it.'

"The end of it was, they plastered disinfectants all round barracks—an' hoped for the best.

"'I can't make it out,' sez Spud, when they'd gone; 'it don't smell now, does it?'

"'Don't ask me,' I sez, very hasty, but Spud opened the box an' sniffed an' sniffed.

"'The best thing you can do,' I sez, 'is to get rid o' that cheese as quick as you can. Me an' Smithy will run the risk an' take a bit—won't we, Smithy?'

"'Not me!' sez Spud; 'it's a plot—a bloomin' capitalist plot to rob the poor.'

"'Very well' I sez sorrerful, 'keep it. Tomorrer, when the officer comes, I'll tell him. I'm not goin' to be poisoned.'

"That night me an' Smithy was in town buyin' some more of that smelly stuff that you get from the chemists. I forget what it's called, but it smells like bad onions, an' Gus Ward, the medial staff feller, put us up to the dodge.

"'What we must do,' I sez to Smithy, 'is to spill a little more than usual round Spud's cot; nothin's too bad for a Socialist that won't share an' share alike.

"The very next day, just before company officers' inspection, I slipped the bottle into me pocket an' goes over to Spud.

"'Spud,' I sez, 'are you goin' to take me into me into the cheese syndicate?'

"'I'll see you in the hot-water department of blazin' L.M.N.O.P.,' sez Spud.

"'Very good,' I sez, an' a few minutes after in came the officer.

"He got half-way down the room before be caught the scent.

"'What the devil?' he sez, an' just then I felt somethin' cold against the leg of me trousis—the cork had come out of the bottle!

"I got seven days' cells for creatin' alarm an' despondency amongst His Majesty's forces, also for an act contrary to good order an' military discipline—but there's compensation for everythin'. When I came out, Spud was in hospital with ptomaine poisonin'.

"I went to see him in hospital, an' after a few personal remarks on both sides, he sez:

"'Nobby, I've been thinkin' about that cheese; it's what I call an illustration of Socialism. You tried to prove it was bad by makin' it smell; I tried to prove it was good by eatin' it. You got time because you wanted it; I'm nearly dead because I had it.'

"'Where's the cheese?' I sez.

"'It's gone back to the land,' sez Spud. "The colonel's got it; it's in his garden, partly to scare away the birds an' partly to fertilise the cabbages.'"

"ME father," said Nobby Clark, "was a rare feller (or family pride.

"If anybody said anythin' against the Clarks, up would go father's quart pot an' bang it would come on the feller's head, an' the landlord of the Crown an' Anchor had to put up a notice. There was three notices in the bar. One was: As a bird at known, by his note, to is the man by his conversation'; another: 'Bettin' not allowed. No ladies served in the private bar, unless they wear boots an' stockin's'; an' the third: 'Visitors arc requested not to talk about Clark's family.'

"Father was very proud of the family. There was Octavio Clark, the great writer, an' Dick Clark alias One-Eyed Dick, the famous pirate, an' often father used to take me through the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud's an' point out various members of the family who was celebrated, one may or another.

He never forgave a dear friend of his for writin' him a letter which begun 'Dear Klark.' Next time father saw him in the street, he walked to the other side of the road. Father would go miles out of his way to avoid that feller, an' when he used to call at our house, it was always 'not at home, Mr. So-and-So.'

"As far as Ģ remember, this feller's name was Bosey, an' the way he used to run after father was scandalous. Father owed him money. One day, when father was returnin' from a stroll in the park, this Bosey feller, who was in a manner at speakin' lyin' in wait, jumped out an' seized on to the. old man.

"'What about them three half-crowns?' sez Bosey.

"Unhand me, feller,' sez father, haughty.

"'Three half-crowns,' sez Bosey, 'what you borrered, an' what I've been writin' about for munse and munse.'

"'I've had no communication from you, me good man,' sez father, 'nor do I desire same. I have never met you before, an' unless you take your vile paw from me coat, I shall, perforce, have nought else to do than to hand you into custody.'

"Father was a well educated man, as you can see, an' Booty was a trifle staggered.

"'That's nice kind of language to use," he sez, very indignant, 'an' after lendin' you that money, an' writin' regular—'

"'Ok,' sez me father, suddenly, as if a light was dawnin' on him, 'oh,' he sez, 'are you the cad that spelt me name with a K?'

"'Never mind about that,' sez Bosey.

"'Hence!' sez father, haughtier than ever, 'hence, low hound, ere I put the weight of me strong right hand across your funny face.'

'Hence, low hound, ere I put the weight of

me strong right hand across your funny face.'

"Father never spoke to Bosey after that.

"'Nobby.' be sez to me, 'let this be a solemn warnin' to you. Never borrer money from your social inferiors. They want it back. If you must borrer, do it with people of your own rank,' an' with that he gave me a long lecture on who to borrer money from. Accordin' to father the best people are chaps who are goin' away on a long sea voyage—their money brings luck. Another good kind are chaps who ain't quite right in their heads.

"I'm inclined to think," mused Nobby, "that anybody who lent money to me father, an' expected it back again must have been a bit potty; at any rate, they began to look like it when they called to collect.

"It was an art collectin' from father, an' most of the chaps who'd lent him a bit durin' the week used to wait till our garden party was on.

"We always had a garden party every Saturday evenin' in the summer. You brought your own beer, an' you sat round an' watched father feed the rabbits.

"'Oh, by the way, Mr. Clark,' one chap would say, 'didn't I lend you two shillin's on Monday?'

"Father would smile gently.

"'Not me, old friend, he'd say, "I'm afraid your memory is goin'.'

"'But,' sez the chap, 'don't you remember? You was standin' at the corner of the street an' I was comin' along, an' you sez to me—'

"But father would shake his head.

"'You've mixed me up with somebody else—how was I dressed?'

"After the feller had described how father was dressed. what sort of tie he was wearin', an' whether he was shaded or not, father would turn to the other chaps with a very significant look.

"'Poor old Bill,' he'd say. 'I'm afraid he's breakin' up.'

"Father was so respected in the neighbourhood that nobody thought of doubtin' his word, but if anybody did, then father's family pride would spring up all of a sudden, an' there was a half-arm hook in the jaw waitin' for anybody who wanted it.

"'It ain't the reflection on me, that I mind,' he used to soy. 'It's the Slur on me ancestors, Uncle Tom an' Uncle Dick'—it's family pride, Nobby, an' a very useful thing to have.'

"I've never tried, the same racket myself because the chaps you meet in the Army haven't much respect for a feller's family. They've had too much trouble with their own.

"Spud Murphy an' Tiny White were rather heavy on the family line, especially Spud when he had a little too much drink. He'd sit on his bed cot an' cry about the way he'd disgraced his family by joinin' the Army, but the only time Spud's rich brother-in-law came to call on him, he was arrested by the sergeant on for attemptin' to steal a barrack-room poker. Spud's rich brother-in-law had it stuffed down the leg of his trousis. After that, when Spud talked about his relations an' the money they had, we said nothin', but Smithy used to get up an' poke the fire thoughtfully.

"Tony Gerrard was the only feller who ever stuck to it through thick an' thin that he was well-connected. He wasn't quite certain how well connected he was. because he'd never been properly christened, an' that," explained Nobby luminously, "makes all the difference.

"Smithy used to say he got his name out of a telephone book, but Antony Gerrard. Esq.—that's how he used to sign his name before he enlisted—said he scorned Smithy.

"There's a certain Lord X," sez Tony one night in the canteen; 'I won't give you his came. But suppose I walked up to him an' offered him me hand—what do you suppose he'd do?'

"'Call the police?' sez Spud.

"'No,' sez Tony, smilin' pityin'ly, 'he'd stagger back an' say "Good heavens—is it J—?"'

"'You bein' the Jay?' I sez.

"'Me bein' so,' sez Tony.

"One night he up an' confessed.

"'I don't mind admittin', he sez, 'that me real name's not Gerrard—that's only part of me name. If you knew me name, you'd recognise it at once as belongin' to one of the greatest families in England.'

"'Name of Smith?' sez Smithy.

" So long as a feller doesn't commit the error of givin' particulars, he can go on makin' impressions, an' givin' you the idea that he's in the brightest an' beat class, an' that's what Tony did.

"It was a bit sickenin', because when Tony was around you couldn't talk about anybody.

"If somebody started 'They tell me that the Duke of Claremarket—' Tony would cough warnin'ly.

"'I'm here,' he'd say.

"Or suppose somebody started criticisin' Balfour, Tony would stop it at once.

"'There's certain reasons.' he'd say. 'why I'd rather you didn't mention Mr. B. Certain family reasons.' An naturally that would dry us up.

"Smithy was arguin' once about Napoleon Bonaparte. Not exactly arguin', but tellin' a feller that if he said so-and-so he was liar. Smithy knows a lot about Napoleon, owing to havin' read a book called 'The Heroic Drummer Boy,' or 'How England Was Saved: A Tale of the Peninsular War.'

"Smithy was in the act of tellin' the chaps how Napoleon used to go round pinchin' people's ears, an' anythin' else he could lay hand on, when Tony, who was drinkin' solitary at the bar an' listenin' with a very moody face, steps is.

"'Smithy,' he sez in a pained voice, 'don't think me foolish, but for certain reasons I'd rather you didn't mention N.B.'

"'For why?' sez Smithy.

"'I can't explain,' sez Tony, sorrerful. would mean givin' away certain secrets that have been in the family for years. All that I'll say,' he sez 'is this: Do you notice anythin' strange about me face?'

"'Yes,' sez Smithy; 'you've got a funny nose."

"'I don't mean that,' sez Tony, hasty, 'but do you see a certain resemblance to anybody you've heard about?'

"Smithy suggested a few people, but somehow didn't quite hit the idea.

"'You needn't be offensive,' sez Tony, 'amongst gentlemen there's no need to be rude an' personal. I asked you a civil question. Don't I remind you in some ways of N.B.?'

"'No,' sez Smithy.

"'Well,' sez Tony, drinkin' up his beer, 'we won't go into the question, but it's very painful for me to stand here an' listen to certain things about certain people.' An' with that he walks out.

"It was about this time that Tony began to take up his family as a serious hobby. Previous to this, he'd only dropped hints at one time an' another, but now he began to work overtime on the job- He got gloomier an' gloomier; didn't talk much; used to sit in a corner of the canteen nursin' an unsociable pint of beer, an' broodin'.

Tony used to sit in a corner of the can-

teen nursin' an unsociable pint of beer

"It got to be the talk of the camp. Fellers from other regiments used to come over to our canteen to have a look at him. It got about that he was a German Prince who'd been disappointed in love. Somebody told Tony this an' he denied it.

"'I don't mind admittin',' he sez, 'that I'm not a German Prince. Not German,' he sez, 'at any rate.'

"Be didn't take the trouble to explain what be really was, an' so, in order to spare his feelin's, we had to wait until he'd left the canteen before we started an argument about any feller.

"If he happened to be present one of the chaps would go up to him an' say: 'Excuse me, Tony, have you any objection to us discussin' Paul Kroojer—or Richard Cure de Lions, as the case might be.

"Sometimes Tony would say 'yes,' but more often—especially the day we was arguin' about Moses an' Bulrushes, an' how Moses got there—he said 'no,' he'd rather we didn't.

"Now, all this went on for months. We was shifted from Aldershot to Chatham, an' back again to Aldershot, an' as far as me an' Smithy was concerned, we got a bit fed Up with Tony an' his family pride.

"One day me an' Smithy were sittin' havin' a friendly talk about Tom Sayers an' Heenan, when Tony pushed his way into the conversation.

"'Pardon me,' sez Tony, 'but when you are speakin' of Tom Sayers will you kindly remember that for reasons that I can't give I'd be obliged if you'd say nothin' likely to injure his reputation.'

"'Tony,' I sez, me an' Smithy would be obliged to you, if you'd give that family of yours a rest.'

"'Speakin' as man to man—' sez Tony.

"'Dry up,' I sez, 'or I'll injure your reputation with the back of me hand.'

"It was what I might call the first serious opposition Tony had ever had, an' it made him broodier than ever.

"Smithy an' me went on leave to London, an' the night after we came back, we was sittin' in the library, so called because it's the only place you can get a cup of coffee, tellin' the other fellers all about our adventures, when in walks Tony, an' I could see the light of battle in his eye, to use a poetical expression.

"I was just in the middle of tellin' the fellers about a certain party me an' Smithy had seen—'The Little Gent' he was called, when in rushed Tony where a good many other fellers wouldn't have dared trod.

"'Pardon me,' he sez, 'the party you mentioned as I come in is on the stage ain't he?'

"'He is,' I sez.

"'A short, stout party?" sez Tony, guessin' very hard,

"'He is,' I sez.

"'Well,' sez Tony, 'all I can say is that when a member of a certain family disgraces hisself by goin' on the stage, it don't seem to me that it's a very friendly thing to chuck it in the teeth of another member of the same family.'

"'Meanin' you?' I sez.

"'Yes,' sez Tony, as bold as brass, 'if you're cad enough to make me confess it, yes!'

"'Is The Little Gent a member of your family? I sez.

"'He's a cousin', sez Tony, 'an' all our family's very much upset about his goin' on the stage. I've done me best to persuade him not to,' sez Tony despairin'ly. 'I've argued with him and talked to him. "Think o' the family," I sez, but he took no notice.'

"'I shouldn't think he would,' I sez, 'because the party me an' Smithy was talkin' about is the Educated Chimpanzee at the Palace,' I sez,"

"IT'S one great thing—to have a good memory," reflected Private Clark, "an' another to know how to use it.

"Me father had one of the best memories goin'. He'd remember things that nobody else remembered—or wanted to, An' at the same time he could forget quicker an' better than any man I know.

"That was what he called his forte, but what other people called his dashed artfullness. He'd recall to the very hour when it was that people wanted to borrow money from him, but, bein' delicate-minded, he never remembered or tried to remember when they actually borrowed—an' nobody else remembered it either.

"If a detective called at our house an' sez, 'Mr. Clark, where was you on the night of the twentieth ultimo?' father could remember everythin'—where he was, who he was talkin' to, what he had for supper, etcetera. An', strange to say. he was always in the very place where the detective didn't want him to be.

"Father remembered lots of things about people who got on in the world, things they'd forgotten themselves, an' hoped everybody else had forgotten.

"There was some people named Winks, who used to live in our street, who come into a bit of money, which was left 'em by an uncle in Australia who wasn't quite right in his head. As soon as the Winkses got the stuff they moved. Took a home in Lilac Avenue, had white curtains, an' washed themselves regular—an' indulged in other unnatural habits.

"The two Miss Winkses went to a private school, an' Master Winks started for the University of Bow. At first they still kept on friendly terms with our street, but after a while they began to get a bit frosty-faced, an' instead of stoppin' you in the street to ask you how the fowls was layin', or where you got that black eye, they'd pass with a nod. An' after a time they didn't even nod. Then old Winks stood for the Borough Council, an' that made him a trifle more affable.

"He came round canvassin', an' called at our house with a lady friend.

He came round canvassin', an' called

at our house with a lady friend.

"'Ho, Clark!' he sez, shakin' hands with father, 'an' how's the world treatin' you?'

"'Very well, Jim,' sez father.

"'Ahem!' sez old Winks, coughin'.

"'Bad cold that of yourn, Jimmy,' sez father.

"'Yes,' sez Mr. Winks, short. 'Fact of it is. Clark,' he sez, I've got a handle to me name.'

"'I know the time,' sez me father, 'when you hadn't got a handle to your beer jug.'

"'Yes, yes,' sez Winks, hasty, 'now about this vote of yours.'

"'I mind the time,' sez me father, thoughtfully, 'when you borrered a shirt off me to go to Epsom.'

"'Let bygones be bygones,' sez old Winks, very agitated.

"'Do you remember that day—fifth of November it was—when you got mixed up in a Guy Fox procession, an' people thought you was the guy?' sez father.

"'The question is,' sez old Winks, desperate, 'are you goin' to vote for me, or are you not?'

"'I ain't got a vote,' sez father, 'owin' to havin' just come out of prison—do you remember that warder at Wormwood Scrubbs, him with the red nose—?'

"Old Winks didn't wait to hear any more. Father said that Winks wasn't satisfied with movin' with the times—he wonted to get ahead of 'em.

"There's a feller I know in' the Anchester Regiment who's one of the finest time-movers that ever was, His name is Hoggy, an' I daresay you've read about him in the papers.

"Hoggy was a feller who'd saved a bit, an' made a bit. A nice young feller, with a curly head of hair, who was always doin' things that brought him in money. There wasn't a dodge that Hoggy didn't know about, from horse-racin' to stamp collectin'. He used to have an advertisement in the 'Bazaar' every week. One week he'd be offerin' to exchange a pair of boots an' twelve bound volumes of the Quiver for a free-wheel bicycle or-what-offers? The next week he'd be offerin' the bicycle for a gramophone or-what-offers, an' the next week he'd be sellin' the gramophone for two pounds an' an encyclopedia or-what-offers? He was such a clever feller at this sort of thing that if he started by advertisin' a pair of dumb-bells, at the end of a couple of months he'd turn them dumb-bells into a horse an' cart.

"That was his hobby swoppin'. I don't know what he did with the things he got, or where he stored 'em, or whether he ever saw 'em. My own idea is that as soon as he'd arranged the swop he'd hand 'em on to the next unfortunate feller.

"He was rather a friend of mine—not exactly a friend, but the sort of man I borrered money from—an' one day he come to me with a long face.

"'I've been had,' he sez. 'I've just swopped a Persian cat for a motor engine, an' I can't get anybody to take the bloomin' thing off me hands.'

"He'd got this motor engine in a shed in town, an' although he advertised an' advertised, nobody seemed to want to take it off his hands.

"He offered to exchange it for a beer-engine or anythin' useful, for a kitchen range or gas stove, but somehow just then motor engines was a drag on the market. I used to think his advertisement wasn't all it might have been, especially the one that went:

Motor Engine; two cylinders; one of them perfectly new, never havin' worked;

but he was such a clever feller that I shouldn't like to say he was wrong.

"Just now all the army is crazy on 'Should Soldiers Learn Trades?' an' after Hoggy had paid three weeks' rent for storin' this machine, he paraded before the C.O. an' asked if he couldn't have it in barracks because he wanted to learn motor-engineerin'.

"An' that's how the motor came into barracks.

"It would have probably rusted itself to bits only just then—it was only a month or two back—the Anchester Town Council thought they'd have a Flyin' Week. It was a new an' original idea. Nobody else had thought of it, except Blackpool, Doncaster, Folkestone, the Isle of Dogs, an' the White City.

"I tell you it created a bit of excitement especially amongst flyin' people, when the prize list came out.

"There was a prize of £5 for the best all-British aeryoplane, an' £3 10s. for a flight of two miles, an' a prize of 10s. an' a round of beef for the chap who went up highest,

"For three days the letter box at Anchester Town Hall was full of letters from Latham an' Veryhot, an' Farmer sayin' that, owin' to a recent bereavement in the family, they wouldn't be able to compete for the prizes.

"We was readin' about this in a special edition of the 'Anchester Gazette' when in come Hoggy in a state of excitement,

"'Nobby,' he sez. 'I can get rid of that dashed choof-choof.'

"'Have you bribed the dustman?' I sez.

"'No,' sez Hoggy, 'I'm goin' to turn it an aeryoplane.'

"It was an idea after me own heart, an' me an' Smithy an' almost every feller in barracks helped.

"The armourer-sergeant made the wings, an' the carpenter made the propeller, an' me an' Smithy bought the calico to tack over the framework. Hoggy got his idea out of a book, 'How to Build an Aeroplane, 1s.'

"'I've entered me name,' he sez, the night before the aeryoplane was finished, 'for the Grand Prix de Anchester—from the soap works to the gas house an' once round the steam laundry.'

"'But what's the good of that? I sez. 'You won't be able to fly.'

"'Never mind,' sez Hoggy, very mysterious.

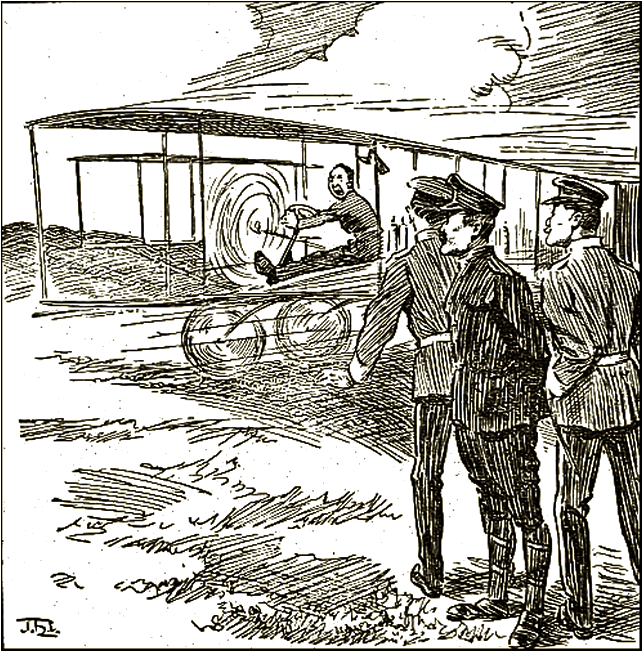

"The account of Hoggy's machine was in all the papers, an' the War Office sent a feller down to inspect it.

"It looked a perfect picture standin' in the back field, with its white wings an' its bicycle wheels (Hoggy swopped a pair of fish knives an' the life of Sir Walter Scott for 'em), an' the War Office chap was impressed. He walked round it, an' touched it, an' smelt it.

"'What do you think of it, sir?' sez Hoggy, very proud.

"'I don't know what to think,' sez the War Office chap; 'start the engine.'

"'I'd rather not just now,' sez Hoggy, who hadn't any more idea of how the engines ought to be started than he had of flyin'.

"The War Office chap took a good look at the engine.

"'It's old,' he sez, 'but it'll work.'

"'You don't mean that, sir,' sez Hoggy.

"'I do,' sez the chap, 'though I don't know what you've been doin' with it.'

"To cut n long story short, the War Office feller got so interested in Hoggy's aeryoplane that he started messing about with the engine—unscrewed it, an' laced it up; buttoned it, an' took a piece out of it. Then he put some petrol in it, an' started the propeller.

"Hoggy was scared to death, but the War Office expert was as pleased as Punch.

"'There!' he sez, 'if I hadn't seen the seen the machine you'd never have got that engine to work.'

"The night before the great Prix de Gas House, Hoggy came into our room.

"'I've got th© "Flyin' Dutchman" down to the what-d'ye-call-it grounds,' he sez, 'an' it's the only aeryoplane there.'

"'Are you goin' to fly?' sez Smithy.

"'I think not,' sez Hoggy, thoughtful, 'but I'm open to sell that aeryoplane to the highest bidder, an one or two people in town are nibblin'.

"That was Hoggy's idea.

"'It looks as if it could fly,' he sez. 'An' when I sit there with the levers in me hand, an' the mad music of the propeller threshin' the air, an' the wind whistlin' through me teeth, soarin' upward, upward, upward, people will he fallin' over one another to buy it. I got that bit about "mad music" out of the "Anchester Gazette"', he sez.

"I must say that the Anchester Town-Council owed somethin' to Hoggy. He was the only aviator who turned up. Two or three fellers came with kites, an' one chap brought a few pigeons, but the flyin' man part of it was done by Hoggy.

"There was thousands on the ground when we got there. Hoggy was talkin' with the War Office chap.

"'Up you get,' sez the War Office chap, but Hoggy didn't like the prospect.

"I don't think it's a good day for flyin',' he sez, 'there's a nine-metre wind.'

"'Nonsense,' sez the War Office feller; 'get up!'

"'The fact of it is," sez poor Hoggy, !I thought of sellin' this machine an' buildin' another.'

"'Get up,' sez the War Office chap, an' we hoisted Hoggy into the driver's seat.

"'It's all right,' I whispers, 'nothin' can happen.'

"'Suppose the bloomin' engine busts?' sez Hoggy, 'or that propeller comes off an' catches me a whack on the head? It's only fastened with glue.'

"It was a great business gettin' Hoggy to start the engine. In the first place, he didn't know how, an' in the second place he didn't want to know.

"So the War Office expert started it.

"Whar-r-r-r! went the engine, an' Hoggy's eyes nearly started out of his head with fright.

"Let go,' sez the War Office feller, an' the machine started runnin' along the ground like a scared chicken.

The machine started runnin' along the ground like a scared chicken.

"'Hi!' yells Hoggy. 'Stop it, Nobby! Stop the dam' thing!'

"To this day," said Private Nobby Clark, solemnly, "I don't know how it happened. I saw the aeryoplane runnin' over the ground, gettin' faster an' faster an' faster.

"Then suddenly it tilted to the right, an' slowly rose in the air. You could have knocked me down with a brick.

"I don't know what discovery we'd made when we was makin' that machine, but there it was—it was flyin', goin' higher an' higher an' higher.

"The people cheered like mad and the War Office feller was dancin' about mad with excitement.

"I went up to him an' saluted—he was an officer.

"'Beg pardon, sir,' I sez, 'did you show Hoggy how to work that there machine?'

"'I did,' he sez. 'I showed him how to start it, an' how to tilt the wings so as to go up.

"'Yes, sir,' I sez; 'but did you show him how to stop it, an' tilt the wings to come down?

"He looked at me.

"'Now you come to mention it,' he sez, thoughtful, 'I didn't.'

"We stood watchin' Hoggy goin' upward.

"'I taught him how to use the rudder', sez the officer, after a bit, 'an' he's usin' it'—which wan true, for Hoggy was goin' round an' round in circles gettin' smaller an' smaller."

Nobby paused.

"Sometimes," be said, pensively, "when I'm on sentry go, in the middle of the night, an' watchin' the stars, I see one twinklin' star brighter than the others, a-winkin' an' a-winkin' most furious. An' when that star begins winkin' all the other stars wink back, an' I know that somewhere in the sky Hoggy is offerin' to exchange a patent aeryoplane for a comet or-what-offers!"

(This story it based upon one of the most remarkable happening in the Boer War. —Ed., Ideas)

I MYSELF would be the last man in the world to suspect Nobby Clark of justifying or attempting to justify the questionable conduct of his father. He had a clear appreciation both of his parrot's genius and shortcomings, and valued both., at their worth. That is how I read his attitude of mind. I think Private Clark is possessed of a large charity of mind. I imagine that he is generous and lenient in some degree when he finds himself reviewing his father's acts, but if, in his filial respect, he cannot condemn, there is a certain irony in his tone when he tells these stories which makes it quite apparent that he does not condone.

"Me father was highly respected by his family," explained Nobby once. "Uncle Jim, Uncle George, an' Uncle Alf couldn't say enough about father an' the way he was looked up to by all his relations.

"Uncle Alf wouldn't have anybody but father to bail him out, an' the way Uncle Jim's family used to come, an' live with us when Uncle Jim was doin' four mouths for jumpin' on a policeman, was very touchin'.

"Then in the summer time, when there was no unemployed work goin' on, Uncle George used to come an'pay us a visit, an' once I remember all three uncles with their families came at once.

"'You're a true brother,' sez Uncle George; 'an' if you can ever make a bit out of me or Alf or Jim, you're free to do so.'

"'Hear, hear,' sez me other uncles.

"Father kept the advice in his mind, an' the first time there was a reward offered for Uncle Jim ('believed to be concerned with others in breakin' an enterin'') father stepped in an' took the prize.

"'It ain't much that I can do to get back the money they've cost me,' sez me father; 'but what I can do I will do with a cheerful heart.

"Fatber went to see Uncle Jim in Wormwood Scrubbs.

"'I didn't think you'd put me away for six months,' sez Uncle Jim.

"'I didn't think I would meself,' sez father. 'I thought you'd get two years,'

"Relations are best apart, especially poor relations, if you don't happen to be so poor as them, an' I've never known, so far as the army goes, any brothers who lived together in harmony longer than four months.

"It stands to reason, in a way, that brothers get on badly. They know each other too well, an' half the secret of keepin' friends with another fellor is not to know auythin' about him, except the side he cares to show.

"Brothers are fairly common in the army, because soldierin' runs in some families like measles, an' crooked noses, but the two strangest brothers I ever know'd was the Joneses— B. Jones an' H. Jones. It was a long time before we knew they was brothers, because one of 'em was in 'B' Company an' the other in 'H'—that's how they got their initials.

"The first time I ever thought they was brothers was when H. Jones came into B. Jones', room an' borrowed his blackin" brushes without askin'. That was a pretty sure sign they were related. They never walked out in town together, never drank together, an' one took as much notice of the other as if he'd been a fly on the wall.

"I sez to one of em—to B:

"'You're a funny sort of feller,' sez I, 'not to have anytbin' to do with your own brother—it don't seem natural.'

"'What don't seem natural to me.' he sez, politely, 'is for you to see anybody else's business goin' on without wantin' to stick your long ugly nose in'

"'B. Jones,' I sez, sternly, 'I'm actin' the best, as man to man, for the sake of peace an' harmony, an' for two pins I'd swipe the head off you.'

"I left 'em alone' after that, but me an the other cbaps used to wonder what it was that'd, so to speak, come between two brotherly hearts.

"'I shouldn't be surprised,' sez Spud Murphy if one of 'em hasn't done the other out of family property ; I've read cases like it in books.'

"Spud always was a bit romantic, an' that was the sort of book he read.

"'Perhaps B's the real heir to the property an' H is a changeling,' he sez; 'perhaĆ¼s the wicked earl done 'em both out—'

"'To be continued in our next,' sez Smithy very nasty; 'perhaps they're only ordinary brothers who are fed up with one another, just as me an' Nobby are fed up with you.'

"It wasn't long after this that Mr. Krujer began pilin' up his burjers on the border, an' the Anchester Regiment, bein'—though I say it as shouldn't—one of the best regiments in the army, was sent out.

"It was tough work in South Africa, the toughest work that most soldiers have done, for somehow the Anchesters always got in the hot an' hungry places.

"We hadn't been in the country three months before we had a casualty list as long as the Rowley Mile, an' what with the closin' up of the ranks an' the reconstruction of companies. B. Jones and H. Jones got into the same company.

"Considerin' we was fightin' every day, an' livin' on half rations most of the time, you'd have thought that these two chaps would have shown a more companionable spirit, but not they. Somehow war, an' the dangers of war, made no difference. They was on noddin' terms, borrered little things from one another, but each went his own way.

"If they'd been people in books they'd have fallin' on one another's necks' after every fight, but they was just ordinary folks an' said nothin'.

"This went on all through the war, an' towards the end our battalion was ordered out to march with a convoy through thy Western Transvaal.

"Our job was to guard it, an' it needed a lot of guardin'.

"We'd hardly got ten miles out of Klerksdorp when Dela Roy come down on us, an' it took us four hours to fight his commando off. Next day De Wet, who was in that neighbourhood, saw us an' came along to pick us up. But it was our early closin' day, an' De Wet went away sick an' sorry. Then when we was half-way on our journey, three commandoes combined to settle us for good, an' at dawn one mornin' began a fight which lasted till sunset. We held a little hill to the right of the convoy, an' this poisition bore the whole of the attack.

"It was the only time durin' the war that I ever saw the Boers charge a position, an' twice that day we had to give way before their attacks. When night came, one out of every four men had been hit.

"We posted strong guards that night, ecpectin' an attaek. an' we got all we expected.

"Firin' began before sun-up. Some of the Boers took up a position on a ridge, where they could shoot from good cover, an' two companies were ordered to clear the ridge. A. and B. companies went an' did it. We took the position with the bayonet, an' then found that it wasn't worth holdin'.

"We got the order to retire on our main post, an' started to march away. Half-way down the slope lay a wounded Boer. He wasn't a real Boer, bein' a half-breed nigger, but as we passed be raised himself up an' shouted 'Water!'

"'Fall out, Jones,' sez the officer, 'an' give that man a drink.'

"What happened exactly I don't know. We went marchin' on, leavin' Jones behind, an' suddenly I heard the crack of a rifle, an' looked round. The half-breed was runnin' like mad toward the Boer lines, a rifle in his hand, an' poor B. Jones lay very quiet on the hillside.

The half-breed was runnin' like mad toward the Boer lines, a

rifle in his hand, an' poor B. Jones lay very quiet on the hillside.

"'Shoot that man!' shouts the officer, an' a dozen men dropped on their knees an' fired at the flyin' murderer, but he dropped over the crest of the rise as quick as a flash.

"We doubled back an' carried the poor chap into camp, but it was all up with him, we could see that much. He was shot through the chest, an' we carried him carefully to the rear,

Soon after this, the Boers returned to the attack, an' we was so busily engaged wonderin' when we'd be wounded ourselves that we had no time to think of B. Jones.

"At one o'clock that afternoon the Boer firin' went suddenly quiet, an' half an hour later we heard a far away pom-pom come into action, an' knew a relief force was on its way.

"Methuen it was, with his column, an' most of as were very glad to see him. We had time now to count heads, an' see who was up an' who was down.

"That," said Bobbv sadly, "is always the worst part of war. It's the part where a corporal an' twelve men go off with spades, an' another party sews men up in blankets—men you spoke to that mornin'; men you've larked with, an drank with.

"I was fixin' up me kit an' givin' me rifle a clean, when H. Jones strolled up.

He nodded to me an' Smithv.

"'I hear me young brother's down,' he sez, very quiet.

"Yes, H,' I sez-

"'How did it happen?' sez H. Jones. So I told him.

"'What like was this nigger?' he asked after I finished.

"As well as I could I described him. He was easy to describe, because he had a big yeller face an' a crop of woolly hair.

"'Come along,' he sez after a bit, 'an' see me brother—he's a pal of yours, ain't he.'

"We found poor B. lyin' on the ground, on the shady side of an ox-wagon. The doctor was then, an' when he saw H. he look him aside-

"'I suppose vou know your brother is dyin'? he sez, an' H. nodded, then turned to his brother.

"'How goes it, Jack?' he sez gentle, an' poor B. grinned.

"'So, so,' he sez, weakly, 'me number's up."

"'So they was tellin' me,' sez H. 'Well, we've all got to go through it, sooner or later.'

"The dyin' man nodded, an' for a little while neither of 'em sp0ke.

"'Got any message to mother?' sez H., an the poor chap on the ground nodded agaiin.

"'Give her my kind regards,' he sez. 'Take care of yourself, Fred.'

"It seemed strange to me," said Nohby, thoughtfully, "that these two brothers, one of them dyin', should talk so calm one with the other, an' I never realised till then how little a feller like me knows about the big things of life, an' death.

"Poor old B. died no hour later, an' his brother was with him to the last. After it was all over he came to me.

"'Nobby,' he sez, 'which way did the Boers go?'

"As it happened I'd heard one of Methuen's staff officers describin' the line of march the Boers were takin' so I was able to tell him.

"'Thanks,' he sez. That night he deserted.

"What happened afterwards I heard from a Doer prisoner who told one of our sergeants.

"H. Jones left the camp soon after midnight, an' dodgin' the sentries, an' the outposts, he made his way in the direction of the Boers. For two days he tramped, sleepin' at night on the open veldt an' with nothin' to eat but a biscuit he took away with him.

"He was found by a Boer patrol, an' as luck wou!d have it, was taken to the very commando that held the ridge.

"By all accounts, the chap in charge was a young lawyer who'd been educated in England an' spoke English better than H. Jones ever could hope to speak it.

"'Hullo!' he sez, when H. was marched before him, an' what the devil do you want?'

"I'm lookin' for the feller that killed me younger brother,' say H.

"The young commandant shook his head with a little smile.

"'I'm afraid,' he sez very gently, 'there are many people in this unfortunate country who are lookin' for the man who killed their brothers."

"'Me brother was murdered,' say H. doggedly, an' told the tale.

"'I don't believe any of me men would have done such a thing,' he sez, ' What sort of a man was he?'

"So H. described him, an' the young lawyer frowned.

"'Bring Van Huis here,' he sez to a Boer, an' by an' bye the man he sent for came—a half-bred Dutchman with a dash of Hottentot in him.

'"'Oh, Van Huis,' sez the Commandant careless, ' they tell me you killed an English soldier at Valtspruit the other day?'

"The man grinned.

"'Ja,' he sez, 'I shot him dead.'

"'Tell me how you did it,' szz the Commandant, pickin' his teeth with a splinter of wood.

"'Hear,' sez the half-breed, 'I called him to bring me water, then I shot him.'

"The Commandant nodded.

"'That was very clever,' he sez, 'so clever that I am goin' to hang you to that tree, an' this soldier shall be your executioner.'

'That was very clever,' he sez, 'so clever that I am goin' to hang

you to that tree, an' this soldier shall be your executioner.'

"H. Jones came back with an escort of Boers, an' was placed under arrest, until the CO read the letter that the Boer Commaudant sent; then he was released.

"'What I don't understand,' sez Smithv to me afterwards, 'is how is it that these two chaps, who never took any notice of one another—'

"But I stopped old Smithy because I knew what he was goin' to say.

"'Friends are friends,' I sez, 'an' brothers are brothers—' then I stopped too, for what more can you say than that?"

"ME father?" mused Nobby Clark. No, I wouldn't call him a genius. Have I? Well, I might have done, because I'm a bit exaggeratious at times.

"But if father wasn't a genius he was somethin' very near it. He was a feller with large ideas. He was a born wangler.

"A wangler, by me way of lookin', is a chap who can wangle things, especially money. Father was the first man that ever found out the way of openin' the penny-in-the-slot gas-meter with a hairpin.

"Like all them discoveries you read about, he found it out by accident. He was tryin' to open it with a knife, an' it was mother who was watchin' his earnest labours that suggested the hairpin.

"When the gasman came round to collect his ill-gotten gains, he found tuppence in the box.

"'Hullo!' he said suspicious; 'this won't do at all. Ain't you been burnin' gas?'

"'No,' sez father; 'gas is bad for the eyes.'

"There was other things that father done, but his best bit of wanglin' was what be carried out with a chap named Hoppy Tailor.

"They was at the seaside for the season, an' was broke to the world. They had a tanner between 'em an' no way of gettin' home.

"'This is very sad, Hoppy,' sez me father. 'Have you tried to borrer the money?'

"'Yes, Mr. Clark,' sez Hoppy, respectful.

"'Did you go to the Mayor with Mr. Clark's compliments?' sez me father.

"'I did,' sez Hoppy, 'an' he set the dog on me.'

"'He must have mistook you for me,' sez me father, thoughtful. 'Well, there's only one thing to be done: you must go into a bathin'-machine an' give me your trousis through the winder.'

"'Waffor?' sez Hoppy.

"'I'm goin' to do one of my celebrated wangles," sez me father.

"So they went down to the beach, an' Hoppy, havin' got into the bathin'-machine, handed his trousis through the little winder to me father.

Hoppy, havin' got into the bathin'-machine, handed

his trousis through the little winder to me father.

"'Be quick, Mr. Clark,' sez Hoppy, 'because its very parky about the legs.'

"'All right,' sez father, an' off he goes.

"First of all he visits the gentleman who lends money, an' hands the trousis over the counter.

"'How much will you lend me on these?' he sez.

"'About tuppence a pound—the usual rate,' sez the pawnbroker.

"'Don't be comic or I'll take me custom elsewhere,' sez me father, sternly.

"The pawnbroker has another dekko at the trousis.

"'Did you come by these valuable goods honestly?' sez the pawnbroker. 'If you did, I'll let you have eighteen pence on 'em.'

"'Make it half-a-crown, an' I'll laugh at your jokes,' sez father, an' after a lot of hagglin' an' a great deal of personal remarks on both sides, he got his two-an'-six.

"'I'll get 'em out again soon,' sez father; 'an' now I come to think of it, you bein' so obligin' an' polite, I've got somethin' else I'd like to pawn,'

"'Bring it along,' sez the pawnbroker.

"Father went out jinglin' his money, walked along the High-street till he came to a place where they sell them little organs that you put rolls of paper in, an' music comes out. Father goes in.

"'Good-mornin',' sez father; 'I'm thinkin' of buyin' one of them organs of yours.'

"'Yes, sir,' sez the shopman, very pleased.

"Father took a long time selectin' one.

"'I'll take this,' sez father, 'on the instalment system; the same as it sez in the winder.'

"So he paid his half-crown, an' signed a form promisin' to pay 2s. 6d, a month for ever. He gave his name as Captain Clark, an' his address at the Hotel Wunki, Hong-Kong an' Elsewhere, an' walked off with the organ under his arm.

"He goes straight back to the gentleman he'd left the trousis with.

"'Here you are,' he sez, 'what'll you lend me on this?'

"'Did you get it honest?' sez the pawnbroker.

"'Do you doubt me?" sez me father, haughtily.

"'Yes,' sez the pawnbroker.

"'Let me have two pounds on it,' sez father, ignorin' the insult.

"'If I let you have more than 14s. I should be robbin' me family,' sez the pawnbroker.

"'Chuck in them trousis I pawned,' sez father, an' after much bitter talk on both sides, the bargain was struck.

"Back to the bathin'-machine goes father, an' shoves the trousis in to Hoppy, an' two hours later you might have seen 'em both on their way back to the Smoke.*

* London.

"This was father's finest wangle, an' as wangles goes, it was very good.

"We had a chap in our regiment named Inkey. Next to me father, he was the greatest wangler I've ever met. If he'd have been a company promoter he'd have been in prison years ago, because he was so clever.

"His great line was organisin'. He organised the regimental sports, an' the sergeants' mess dance. He only organised that once, because, the contractor lost so many spoons on' things that he said it did not pay. He organised a 'break' excursion out into the country once, an' overdid his wanglin', because, owin' to the fact that he wangled the coachman out of his beer, an' wangled the horses out of their corn, we nearly didn't get home that night.

"Inkey was the feller who was asked by the Anchester Town Council to fix up a Guy for their annual Guy Fawkes celebration.

"The Chairman of the Council sent for him.

"'We've got all the other arrangements fixed,' he sez, when Inkey offered to organise the whole show, 'but we haven't got a good Guy made. You bein' an ingenious sort... Now, what we want is a life-like Guy."

"'I see,' says Inkey, thoughtfully.

"'We've had one made,' sez the Chairman, 'but it wasn't satisfactory. We want a Guy made like Lloyd George.

"'I see,' says Inkey again.

"'It's got to be so life-like that dogs'll fly at it,' sez the Chairman.

"'I see,' sez Inkey, 'life-like, with a red nose an' smokin' a clay pipe.'

"'Somethin' like that,' sez the Chairman. 'We'll allow three pounds and provide the clothes.'

"'I see,' sez Inkey, an' away he goes, more thoughtful than ever.

"I think," mused Nobby, "that Inkey must had had a bit of trouble with that Guy. He used to come back to barracks at night—he was doin' his stuffin' at the Corporation yard—lookin' very worried.

"'I can't set the legs proper,' he sez, 'an the chest is all in an' out.'

"The day got nearer, an' poor Inkey was desperate.

"One night he came to me.

"'Nobby,' he sez, 'do you want to earn a sovereign?'

"'No,' I sez.

"'Do you want a sovereign?'

"'Yes," I sez.

"So then he put the case before me. He wanted a human Guy. A feller who'd dress himself up an' wear a mask.

"'Nobody would tell the difference,' he sez; 'all you've got to do is to sit still on a cart in the procession, an' after it's all over, we drive you back to the shed, you change, and there's your sovereign—is it a go?'

"'No,' I sez sternly, 'me pride won't allow it. Besides, a pound ain't enough—make it three.'

"'Not,' sez Inkey, very firm, 'if you was starvin' I wouldn't give you three pounds.'

"'Then take your funny face away,' I sez, 'or I'll draw pictures on it.'

"I don't know who else Inkey saw, but the next afternoon I saw Spud Murphy changin' half a sovereign.

"'Hullo,' I sez, 'one of your own make?'

"'No,' he sez, careless. 'I've got a job.'

"'Wot as?'

"'As a sort of artist's model,' he sez, an it was such a nice way of puttin' it, that I didn't let on.

"The day before the celebrations, Spud Murphy paraded before his company officer an' got leave of absence. He went out of barracks, sayin' he was goin' to London, but as I saw him an' Inkey goin' out of barracks together, I put two an' two together, an' made it six.

"The Fifth of November broke bright an' fair," Nobby resumed poetically, "an' after the C.O.'s parade, most of us began to get dressed in our walkin'-out kit, in readiness for goin' down town.

"The streets were decorated beautifully. Outside Sloggs, the oil shop, was a Union Jack an' a patriotic inscription which said, 'No Popery—Go to Sloggs for Your Soap,' an' another that said, 'Long Live the Empire—Sloggs for Ironware.' At the corner of Market-street was a string of flags of all nations, an' a stirrin' message to the people of England about Doncups Tyres.

"There was thousands in the streets. Me an' Smithy counted twenty without reckonin' ourselves, an' everywhere there was signs of animation an' drink.

"We got a good place near the mayor's grandstand, an' at 3.30, an hour after the procession was supposed to have started, an' when the crowd an' the language was gettin' a bit thick, we heard, as the poet sez, the distant chimes of music.

"'Here they come,' sez the excited people.

"It was a wonderful sight, the Anchester Guy Fawkes procession. First came a policeman on horseback, lookin' very noble in his new white cotton gloves. Then came the Anchester Town Band playin' a piece, that anybody with a musical ear could recognise as 'Rule Britannia.' Then came the Amalgamated Bird Frighteners' Association with their banner, then the Royal United Society of Bird Limers an' Allied Agricultural Pursuits with their banner; then came the Temperate Sons of Water with a banner inscribed, 'We Drink What Other Beasts of the Field Drink.' Then came the nugget of the show: Guy Fawkes hisself. He was on a trolley drawn by four prancin' horses—with a feller walkin' alongside each horse to give him a dig in the ribs every time he forgot to prance.

"The Guy was wonderful life-like. He sat by a big table with a clay pipe, an' a notice over his head 'This is Lloyd-George,' in case nobody recognised him. There was all sorts of notices stuck on the car. such as 'This Car was Lent by the Anchester Brewery Company,' an' 'Horses Supplied by the Electric Tramway Reserve Stable,' an' the people cheered themselves hoarse.

"It was a great affair. The mayor made a speech about England an' how proud we all ought to be at the opportunity of burnin' Guy Fawkes.

"'Tonight,' he sez, pointin' his finger at the Guy Fawkes, 'to-night we shall see this creature consoomed in flames.'

"I thought I saw the Guy wriggle a bit uneasy, but I wasn't sure.

"'To-night,' sez the mayor, 'in this effigy we'll burn the old bigoted superstitions, an' show the world that we're enlightened an' tolerant.'

"'Burn him now,' sez a voice in the crowd.

"'Hear, hear,' sez everybody, an' I thought I recognised the voice as me own.

"The Guy gave a little shudder.

"'Burn him now,' sez the voice again, 'I've got some matches.'

"'No," sez the mayor, 'we'll keep him for to-night.'

"All the time Inkey, who was standin' by the van, was lookin' very nervous. He was relieved when the mayor said he'd put the burnin' off, more relieved still when the procession started movin' on—an' then somethin' happened.

"Who it was threw the cracker at Lloyd-George I don't know," said Nobby solemnly; "some people sez it was me, some sez it was Smithy. They're probably right. Suddenly—

"Who it was threw the cracker at Lloyd-

George I don't know," said Nobby solemnly

"'Bang! Bang! Bang!'

"What happened then I've never quite made out.

"I saw Lloyd-George jump up with a yell an' go runnin' down Market-street follered by the Associated Bird Frighteners an' the Sons of Water. I heard yells an' screams an' encouragin' cries of 'Kill him—it's Lloyd George,' but didn't see Spud till the next day.

"He turned his back on us when we came into the canteen.

"'Hullo,' I sez, 'been to London?'

"'I have,' he sez short.

"'Pity.' I sez, 'but you didn't miss much—they didn't burn the Guy last night.'

"'No?' he sez chokin', 'why?'

"'He was too green to burn,' I sez."

THERE can be no doubt whatever that much of pathos underlies the humour of Nobby Clark. I doubt not that from the full storehouse of his varied experience, he is careful to abstract only the more pleasing of his stock for my satisfaction.

But sometimes, in a wisp of fun, you find a strain of tragedy. How it got there one does not trouble to speculate upon: its intrinsic value is infinitesimal, but for the hint it gives of the presence of that tragedy, so carefully hidden and stored away in dark mind cupboards.

Once, only once, I remember Nobby discussing that wonderful father of his seriously. Usually there was something of irony, something of pride, much of flippancy. But this time Nobby was quite serious.

"I've never properly tried to understand me father," he said, shaking his head. "In many ways he was like Mr. Cody's flyin' machine—his engines never acted twice alike.

"Sometimes, in a manner of speakin', he'd fly an' carry passengers, sometimes he'd only hop along the ground. Sometimes, when it looked as if only an hydraulic crane could lift him, up he'd go, soarin' an' soarin, like a bloomin' skylark.

"What father did never used to worry me, an' I never troubled to understand him. I believe it's a wise child that knows his own father, an' nobody knew mine, for he was as wide as Birdcage Walk.