RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

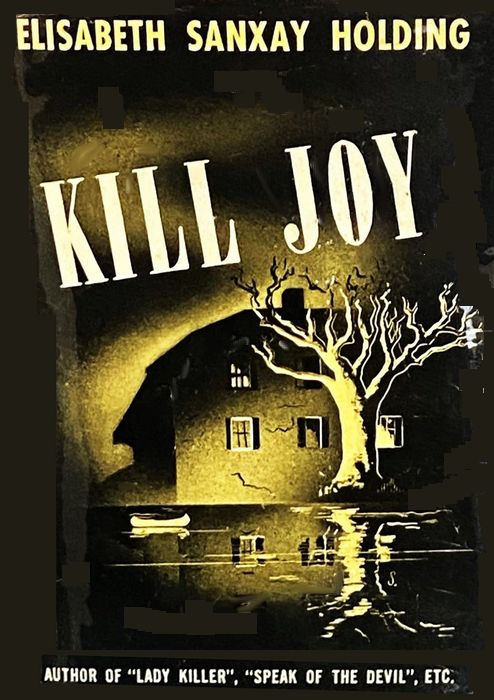

Duell, Sloan & Pearce, Inc., New York, 1942

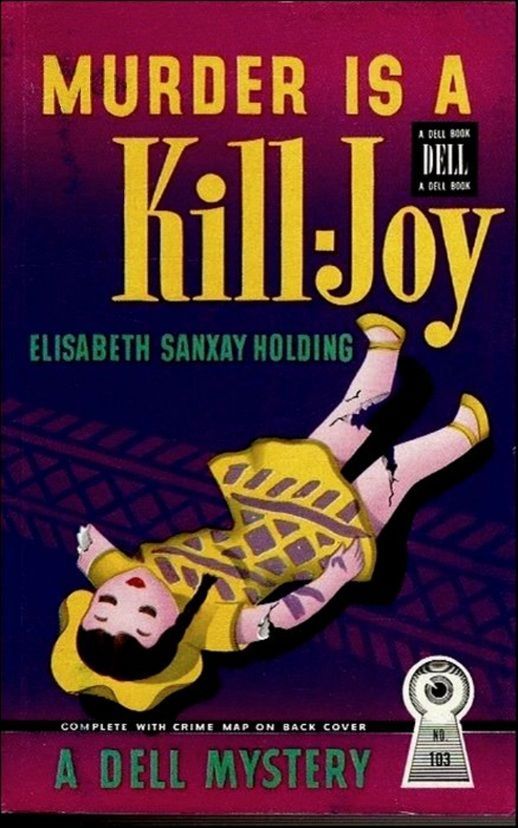

"Murder Is a Kill-Joy," Dell Books, New York, 1946

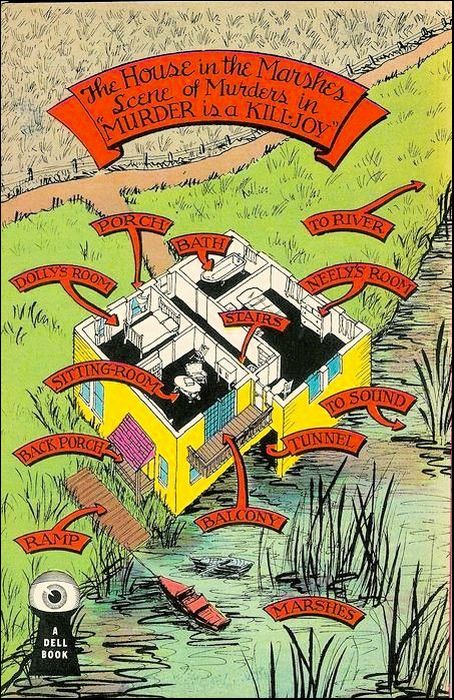

Back Cover of "Murder Is a Kill-Joy," Dell Books, New York, 1946

"Kill Joy" is a compact, atmospheric suspense novel centered on Maggie, a sensible young woman who becomes entangled in a deeply unsettling situation after agreeing to accompany her employer, the dreamy and romantic Miss Dolly, on a mysterious nighttime journey...

IT was nearly half-past two when Mrs. Crabtree and Maggie had finished their lunch and the last of the dishes was dried and put away.

"Are you coming upstairs now, Mrs. Crabtree?" Maggie asked.

"No," said Mrs. Crabtree. "No, Maggie, I think I'll stop here a bit and read my paper."

That was bad news for Maggie. Mr. Camford was home this afternoon, and she dreaded the prospect of meeting him alone in the hall. She hated his way of looking at her, an annoyed and embarrassed way, as if she were an intruder from another world. As if she were a servant, a mere servant. And she was not. She might be employed here as a maid; but that was of no significance, it was only temporary. She was a high school graduate, and a very proud girl.

"No," Mrs. Crabtree said again, "I want to read about this murder."

"Oh, Mrs. Amber?" said Maggie. "That's a terrible thing, isn't it?"

"Well," said Mrs. Crabtree, "she brought it on herself."

"Oh, d'you think so?" asked Maggie.

"They all do," said Mrs. Crabtree, settling herself in her rocking-chair with a comfortable creaking.

She was an Englishwoman of great dignity and composure, stout, high-waisted, with grey hair crimped and parted in the middle; when she put on her spectacles, she had the benign authority of a fairy godmother.

"Well, but how? asked Maggie.

"These women that get themselves murdered..." said Mrs. Crabtree. "When you study the cases like I do, you'll see how they've all been flouncing around in these pajamas and these shorts—and shorts they are. They all get themselves mixed up with men, one way or another."

"But anybody could get murdered," said Maggie.

"They could," said Mrs. Crabtree. "But they don't. They bring it on themselves."

"Well, I've read about girls, respectable girls—" said Maggie, resisting this new theory.

"Yes," said Mrs. Crabtree, "but study the cases, and you'll see they've done something very foolish like going down in a cellar with one of these foreigners, or taking a ride with a gunman. You'd better go up and change now, Maggie. It's getting on, and Mrs. Mayfield likes you to be ready in your black uniform by three o'clock."

It was hard to leave the neat tranquil kitchen and the company of the admirable Mrs. Crabtree. But it was Maggie's duty to go, and she always did her duty. Always. She went up the dark flight of stairs from the basement, and that was all right, these stairs belonged to Mrs. Crabtree and herself. But there were no back stairs in this house, and when she reached the top of this flight, she was in Mr. Camford's domain.

He might be right there in the sitting-room, she thought, and she wanted to run, she felt limp and bedraggled in her blue cotton dress. But she would not run, she walked straight as an arrow, a pretty little thing with vivid blue eyes and crisp coppery hair and a creamy skin dusted with tiny freckles.

I don't care, she told herself. I'm doing the job I'm paid to do, that's all. This is a democratic country. I don't have to stay—like this. Some day, who knows? I might meet Mr. Camford at a party some day, when I'm a private secretary, or married to somebody much better than he is.

She got safely past the sitting-room and mounted the second flight, and there in the hall she nearly ran into Mr. Camford coming out of the bathroom. He was in his dressing-gown, too, which made it worse. He stepped aside, and so did she, so that they still faced each other; he raised his eyebrows, a tall, lean, bald man, ineffably distinguished. Maggie stepped to one side again, and so did he, and there they still were.

He made a faint tut-tut sound and turned away, back toward the bathroom, as if he could not endure the sight of her, and she went on toward the last flight, her cheeks burning, a hot resentment in her heart. He's mean, she said to herself. He could speak, couldn't he? Or even smile. You'd think I was—I don't know what. Dirt beneath his feet. All right! One of these days, I'll show him, the mean old thing.

She went into her own small room and closed the door, she went to the chest of drawers, and leaning her elbows on it, looked at the picture of her mother which stood there in a leather frame, a sandy-haired little woman with a thin, fine face. Her mother's idea, this had been. You could get a nice place with a private family, she had said. You mean, be a servant? her daughter had demanded. Yes, Mrs. MacGowan had said. You'd learn more about life in that way than ever you could in an office, and when you come to figure it out, you get more money.

Maggie had utterly repudiated that suggestion. She had decided to get a nice job in an office, and why not? She had taken a commercial course in high school, and she had done well in it, as in all her studies; she had a good opinion of her abilities. The reception she got at employment agencies surprised and displeased her. It was undeniable that she had had no experience, but she sat and talked to other girls just out of business school who were sent out to get jobs. She had some interviews, but nothing came of them.

"I don't see why it is that I don't get a job," she said to another girl waiting in an agency.

"Well," said this other girl with impersonal candor, "I think it's because you're kind of old-fashioned."

"Old-fashioned?" Maggie repeated.

"Yes, kind of," this other girl said.

"There's nothing old-fashioned about me," Maggie said briefly.

But on the way home, she looked critically at herself in shop windows, and doubts assailed her, to see that straight small figure in a long grey coat and a round felt hat... There was only one week left. Mrs. MacGowan was going off to Maine to keep house for a very exacting brother while his wife went to the hospital. You'll have to get yourself settled, Maggie, one way or another, she had said, or else come with me.

Maggie went to a domestic employment agency the next day, and the moment she set foot in it she was a valuable and interesting client. She was sent out to see Mrs. Mayfield, and Mrs. Mayfield had engaged her there and then. In a way, she thought, it's not such a bad job. I've saved twenty-one dollars out of my first month's pay, and I've learned quite a lot, listening to them talk and all that, and Miss Dolly has been sweet to me. But it's not what I want, and I won't stay.

She put on her black poplin dress and the little ruffled apron and the cap that was a frill with a black velvet band. It was becoming to her; she looked pretty. But she did not want to wear a cap and apron. I'm not going to be just a maid, she said to herself. I can do better than this for myself. A lot better.

She took out her Manual of Shorthand, and her notebook, and started down the stairs. It was not nearly so bad to meet Mr. Camford in the hall when she was wearing her black uniform and her best shoes; she felt almost professional. Let him come, the mean old thing...

"Maggie!" said a low and lovely voice, and she turned to see Miss Dolly in the doorway of her room. "Come in, will you, Maggie?" she said. "And close the door. I want to speak to you."

A woman of mystery, Miss Dolly was, and Maggie was deeply interested in her. Still young, handsome and elegant, she lived a curious and solitary life here with her aunt and uncle. She never went anywhere except sometimes to do a little shopping; no one came here to visit her.

But it had not always been like this. Maggie came in every morning to do the room, and she had found in it souvenirs of a very different kind of life, little things, bottles, boxes, ash-trays from Paris and London, and in the closet were lovely evening dresses and wraps and slippers, gold and silver. Sometimes Miss Dolly would come in while Maggie was busy there, she would sit down and light a cigarette and talk with a vague and melancholy kindness; she would ask Maggie questions about herself, sometimes she gave her a little present, a cake of perfumed soap, some writing paper, an embroidered handkerchief.

"I think she's had some great misfortune," Maggie said to Mrs. Crabtree.

"I don't know about that," Mrs. Crabtree had said. "What I do know is, that she wasn't living here when I first came a year ago. She had a place of her own somewhere, and I never saw her here, and never so much as heard there was such a person till the day she came, bag and baggage, to stay."

"It seems a strange way for anyone like her to live," Maggie had said. "She's very good-looking, don't you think, Mrs. Crabtree?"

"Yes," Mrs. Crabtree had admitted. "Though I must say I don t care for such a dark complexion. It always looks foreign to me. And she talks French; I've heard her on the telephone."

This made her still more interesting.

"Why ever do you suppose she came here to live in such a lonely kind of way?" Maggie had asked.

"I couldn't say," Mrs. Crabtree had answered.

"Mrs. Mayfield and Mr. Camford seem so sort of distant to her," Maggie had continued. "I don't think they're nice to her."

"That's something I shouldn't care to give any opinion on, Maggie," Mrs. Crabtree had said with a trace of severity. "Not knowing the circumstances."

But Maggie went right on having opinions. She looked over at Miss Dolly stretched out on her chaise-longue, supple and languid in her black chiffon negligee, smoking a cigarette, her dark eyes gazing steadily and sadly out of the window. It's some love affair, thought Maggie, waiting there with her Manual under her arm.

She turned her head toward Maggie.

"Maggie," she said, "I can trust you, can't I?"

"Yes, ma'am," said Maggie.

"Ever since you came here, I've been studying you, Maggie," said Miss Dolly, "and I think you're a very remarkable girl."

The color rose in Maggie's cheeks, her heart beat faster, with pleasure and a sort of relief. For this was what she had been waiting for, this praise, this recognition that she was not really just a maid.

"Thank you, Miss Dolly," she said.

"I'm going to translate a French book into English. It's a wonderful book and I think it'll make a sensation. I'm going away to the country to work on it, and I want you to come with me as my secretary."

This was almost too good to be true.

"Miss Dolly... Thank you," said Maggie, a little unsteadily. "I haven't had much—I haven't had any real experience, but I can type pretty well. I'm a good speller—"

"I know you're just the right person for me," said Miss Dolly. "You're young—how old are you, Maggie?"

"Nineteen, Miss Dolly."

"That is young, isn't it?" said Miss Dolly with a faint smile. "But I think you're very understanding, Maggie. I think we'll have a wonderful summer."

"Yes, Miss Dolly," said Maggie. "When did you think of going, Miss?"

"I've got to go tonight."

"Tonight!" said Maggie.

"Yes. There's a car coming for me."

"But Miss Dolly, I've got to give Mrs. Mayfield notice."

"She can easily find somebody else, Maggie."

"Yes, I know, Miss Dolly, but—well, I'm sure she wouldn't discharge me without notice, and I don't feel I ought to do that to her."

"We can arrange that."

"Shall I speak to her now, Miss Dolly, and see what she thinks?"

"No," said Miss Dolly, and fell silent for a time. "Maggie," she said, "I don't want my aunt or my uncle or anyone to know we're going."

"But, Miss Dolly!" cried Maggie. "You mean for me just to go, just to walk out, and not even tell Mrs. Crabtree?"

"Maggie, I've got to go tonight," said Miss Dolly, "and I've got to go—without anyone knowing. You can take my word for it, can't you, that I've got a good reason?"

"Yes, Miss Dolly, but—"

"But what?"

Maggie was almost too miserable to answer. This thing was too good to be true. Lots of things were. I ought to've known there'd be a catch to it, somewhere, she thought.

"Maggie," said Miss Dolly, "I'm going to trust you utterly. Hand me my bag, will you? Read this, Maggie." She took a typewritten letter out of an envelope and handed it to Maggie.

"Dolly, you Devil:

I'm not going to wait any longer. Tomorrow I'm coming to the house—with a bottle of vitriol. Then you won't sneer at me any more, devil that you are.

Othello."

"But, Miss Dolly!" said Maggie, astounded. "It's some land of joke, isn't it?"

"No," said Miss Dolly.

"But, Miss Dolly, if anybody means that—"

"He does mean it," said Miss Dolly.

"But then, Miss Dolly, you ought to tell somebody. Mr. Camford—"

"He's the last person I'd ever tell. He and my aunt would turn me out of the house if they knew anything about this, and they'd take all my money."

"They couldn't do that, Miss Dolly. Nobody's allowed—"

"Yes, they could. I've signed all sorts of papers... Maggie, you must have noticed how it is here for me, how unwelcome I am. In this house—the house I was born in. It was my father's house, Maggie, and he meant me to have it. But I was very young—and very foolish... I was so happy here with my mother and father when I was a child—and maybe that's not a very good preparation for the world... My parents were so gay and generous and loving... I didn't realize how different other people were. I trusted people—too much."

There were stars in her dark eyes, and Maggie felt very sorry for her—in a way. But she was more shocked than touched.

"Do you mean they—other people—have got your house and your money away from you, Miss Dolly?" she asked.

"Oh, I wouldn't care about that if they were only kind and understanding," said Miss Dolly.

"You have to care about things like that," said Maggie briefly. "You have to look out for yourself—"

"I'm not like that," said Miss Dolly. "I just want to get away, Maggie. I just want a little peace and quiet."

"But, Miss Dolly, that man, the one that wrote the letter, he'll find out where you are, and he'll come after you."

"He won't, if nobody here knows where I've gone. Oh Maggie, please don't argue any more! Please just be kind and friendly and come with me. Things are worse, much worse than you imagine. I'll tell you later, when we're out of this horrible house. Maggie, you're so sensible and well-behaved. I need you so. Won't you come with me, Maggie?"

What a strange thing, that anyone like Miss Dolly, beautiful and rich and aristocratic, should be begging and praying Maggie MacGowan to come away with her! It's like a story, Maggie thought. I know I'm sensible. I know if there's one thing I am, it's practical. I do know how to look out for myself and I dare say I could help Miss Dolly in more ways than one. I suppose she sort of felt that, by instinct.

Miss Dolly had laid the back of her hand against her forehead, her eyes were closed, one hand dropped over the arm of the chair; she looked exhausted and curiously helpless. Look what she's got herself into, thought Maggie. There's this man threatening to throw vitriol at her—and she's signed these papers and lost her house and her money. My goodness!

"Will you come, Maggie?" asked Miss Dolly.

"Yes, miss," said Maggie.

"Oh Maggie, I'm so glad! I'll talk everything over with you once we're away from here. Maggie, the car's coming at half-past eleven. Just pack what you'll need for a day or two, and meet me at the back door. I'm so glad, Maggie..."

I'm doing the right thing, to go with Miss Dolly, Maggie said to herself. She's in a great deal of trouble, and she needs me.

But just the same, she felt mean.

Mrs. Crabtree had gone up to her room for her afternoon rest, leaving the kitchen as neat as a pin, the dessert was all made and in the ice-box, the lettuce was washed and in a sieve, the leg of lamb stood on the table ready for the oven. Always leave your meat out of the ice-box two or three hours before, you cook it, she had told Maggie.

It was quiet as the grave down here, not a sound but the loud ticking of the clock. Through the barred window you could see feet going by along the street, cracked old shoes, and gleaming new ones, gay high-heeled pumps and a child's little stubby brown shoes. Sometimes a truck passed with a hollow roar, shaking the walls, the windows rattled in a gust of wind. Mrs. Crabtree's newspaper lay neatly folded in the rocking-chair, and Maggie sat down to read it for a while.

There was a picture of that Mrs. Amber; pretty she was, and young. It's funny there's never a word about Mr. Amber, thought Maggie. Well, maybe she wasn't really married at all. Brought it on herself...? They all do, Mrs. Crabtree said, getting mixed up with men... Miss Dolly must have got mixed up some way with the man who wrote that letter. Othello. Well, that was Desdemona's husband, and he smothered her with a pillow. Vitriol... That's a terrible thing. It blinds you and eats away your flesh... I don't think she realizes how serious it is. I don't think she realizes anything much. She's so helpless. She needs someone to look after her.

She sighed, and put down the paper and opened the Shorthand Manuel. It's going to be wonderful experience, working on Miss Dolly's book, she thought. Maybe later on I can get to be a secretary for a famous author. I'll get to tea parties where there are famous people. Who knows? I might even marry a great author.

At half-past five Mrs. Crabtree descended in a clean print dress; she moved about, amiable, superbly adequate.

"Just the three of them for dinner," she observed. "I never like to work for three. Two is all right, and four is all right, and more than four. But three is awkward."

Maggie set the table as Mrs. Mayfield wanted it; real old-fashioned, she would not have any of the nice things you saw in the magazines. A fine damask cloth, the ornate old silver, the French china with a band of deep blue and gold, and right in the middle a white bowl of red carnations. A few moments before seven, Mrs. Mayfield herself came into the dining-room in a black dinner dress, a tall woman with an ungainly stoop forward from the waist, and dark hair grizzled at the temples. She looked at the table in her peering, absent-minded way.

"You're learning to do very nicely, Maggie," she said. "You can light the candles now."

Maggie lit the four candles in the chased silver holders, and the family entered. Mr. Camford, in a dark purple smoking-jacket, sat at the foot and his sister opposite him and poor Miss Dolly at the side. She had a queer look tonight, Maggie thought; maybe because she had her raven-black hair brushed back from her forehead, making her face look thinner, almost worn; or maybe it was because she had come to the table in a yellow sweater and a short skirt.

Mrs. Mayfield began to talk about a book she had just finished reading, she told about it firmly and clearly, and her brother listened with attention. No wonder, thought Maggie. She's got such an interesting way of telling about things, and she knows such a lot. Miss Dolly's very well educated and speaks French and all that, but she can't hold her own with those two. Not about books and things like that.

The rope of the dumb-waiter slapped gently against the wall; that was Mrs. Crabtree's signal that the entrée was coming up. Everything served just right, the leg of lamb carved in juicy slices, the vegetables in covered dishes, the plates warmed, the mint jelly solid.

I guess this is the last time, Maggie thought as she stood at the sideboard, and a curious pang of regret shot through her. It's nice, she thought, looking at the table with the candles and the red carnations. She knew every fork and spoon, every plate and, glass; for six months she had been handling them with care and even affection. And I like to hear Mr. Camford and Mrs. Mayfield talk, she thought. I know they're mean to Miss Dolly, but they've got something.

"Maggie!" said Mr. Camford reproachfully. "Water, please!"

He felt strongly about having to ask for water. Mr. Camford liked observant service, Mrs. Mayfield had said. And he's right, Maggie thought, filling his glass and looking down at his bald head with new indulgence. Well, I guess I'll never see him again.

She had her own dinner in the kitchen with Mrs. Crabtree, and it was cozy. Mrs. Crabtree was particular, too; they had a nice clean tablecloth and napkins, their plates were warmed, too. They ate just what the others did, only instead of coffee they had a big brown pot of tea.

"The grocer's boy had a late paper," said Mrs. Crabtree, "said he found it. He left it for me. He's a nice boy. There's more about that Mrs. Amber in it, and you can see it's the way I said. She brought it on herself. Divorced, she was, and living all by herself, except for this colored maid. And she had these cocktail parties that lasted half the night, and so on. A gay life, as they call it."

She washed the dishes, and Maggie dried them.

"Well..." said Mrs. Crabtree after she had locked the iron gate to the area and seen to all the windows. "I'll leave the paper for you, Maggie. I'm off to bed."

"Good night, Mrs. Crabtree."

"Good night, Maggie."

I'm not going to read about Mrs. Amber, Maggie thought. I'm sick and tired of it. And I've got other things to think about.

She was supposed to remain on duty until ten o'clock in case the doorbell rang. Well, it was after nine now, and she thought she could well use the interval in planning what she should take. Her bag was small, and there was so little that could be got into it that her planning was soon done.

Then, to fill in the last moments, she picked up Mrs. Crabtree's newspaper. Clubman Sought in Amber Slaying. And a picture of Mrs. Amber, smiling. She had been found dead, shot, lying on the floor or her bedroom, partially clad, the papers said. I'm sick of that case! Maggie cried to herself, and turned to the editorial page. She read the editorials every day, all of them, to improve herself.

Ten o'clock. She gave the neat cozy kitchen a last look, and turned out the light; she went upstairs to the parlor floor. Mr. Camford was in the drawing-room nearby, but the other rooms were empty; she went on up to the top floor and began to pack the little bag of imitation crocodile, very soft. She had decided to wear the black poplin dress she had on, and she packed her cap and little apron, and a clean morning uniform. Miss Dolly had said she was to be a secretary and not a maid, but there might be little things to do.

When the bag was packed, she sat down to read her book, Anna Karenina. It was one of the classics she was determined to read; it interested her and exasperated her. She left her door ajar, and at eleven o'clock she heard Mr. Camford mounting the stairs. The house was quiet now, very quiet.

Her heart beat fast, her hands were cold as ice. Oh, suppose I met Mr. Camford or Mrs. Mayfield now? she thought. Sneaking downstairs with a bag... Whatever could I say to them? Or suppose Mrs. Crabtree came out now to the bathroom and saw me? I don't think it can be right, to do anything that makes you feel so terrible.

So guilty. She put on the round felt hat and the grey coat, and bag in hand started down the stairs. What'll I say if anybody catches me? I ought to have something ready to say... Well I can't. I won't. I'll say—I'm going away, that's all. Nobody can stop me.

Nobody tried to stop her. She went past the closed doors of the bedrooms and down to the lower hall where a dim light burned all night, down into the black basement, stuffy, filled with the warm, stale smells of cooking. She unlocked the door and stood in the little space between the door and the iron gate to the area. It was nice to be out in the air, nice to look out at the quiet upper East Side street with a light on the corner, and cars going by, and now and then someone on foot.

There was a man on the corner with his back to her, a stocky, broad-shouldered man in a brown pull-over and dark trousers; the street light shone on his bare head that was silvery white. She looked at him idly, wondering what he was doing there, then she looked back over her shoulder, she listened for the sound of Miss Dolly's footsteps. A gust of wind blew through the barred gate, damp and chilly, there were no stars in the sky. Not much of a night for a drive, she thought. I hope it's not a long way.

The man was still standing there; what could he be doing? I wish I had a watch, Maggie thought. As soon as I can save up more, I'll get one. Whatever is that man doing? Could he be that Othello?

A sound behind her made her start; she saw the beam of an electric torch across the kitchen floor.

"Maggie!" said Miss Dolly's voice.

"I'm here, Miss Dolly."

Miss Dolly came to her side and set down her bag.

"It weighs a ton," she said. "Oh, there's Neely! Open the gate, will you, Maggie?"

Maggie opened the gate, and Miss Dolly went out leaving her bag behind her. "Ah, well..." said Maggie, and she picked up both the bags and followed her.

Miss Dolly and the silver-haired man had moved aside from the circle of light; they were going round the corner talking to each other, a queer couple, Maggie thought. The man was so kind of poor-looking, and Miss Dolly so stylish in her short fur jacket and her narrow black skirt, her black turban, her high-heeled shoes. The chauffeur, he must be.

There was a car drawn up to the curb, a big, old-fashioned car; the man got in behind the wheel, and Miss Dolly stood waiting for Maggie.

"Will you sit in the back, Maggie?" she said. "I want to talk to Neely."

There was a glass partition behind the front seat; Maggie, alone in the back, was shut off in silence and a moldy darkness. It's a funny feeling, not to know where you're going she thought.

She looked at Miss Dolly and she was astonished. The light on the dashboard showed her face all alive and sparkling; she was smiling, talking to that driver, and he was talking to her. Not like a lady and a chauffeur. Well, maybe he wasn't a chauffeur, but the owner of the car, only he looked so sort of poor.

It came into her head then, that, after all, she knew very little about Miss Dolly, and nothing at all about her friends. A very funny feeling it was not to know where you were going, or who you were going with.

THEY were out of the city, driving along a wide boulevard, when the rain began dashing against the window, drumming on the top of the car. The two straight rows of lights ahead twinkled through a veil of falling water, the flat countryside was blotted out, the cars and trucks that passed them went with a blurred rush.

Maggie leaned back in a corner, chilled and depressed. She was in the habit of going to bed early, and she closed her eyes and fell asleep now. But only for a little time; she waked with a start, and there was the rain and the black flat countryside, and Miss's vivid happy face turned again to the driver.

She dozed again, and waked when the car began to jolt over a road full of ruts. There were trees here and no lights, the car slipped and struggled in mud. It's just miserable not to know where you're going or where you are, she thought. If I even knew what time it was... I wish I had a watch.

That bothered her more than anything, that feeling of blank and unlimited time. Suppose I've been asleep for hours? she thought. Suppose it's tomorrow night? Well, it isn't. I mustn't be silly. There's Miss Dolly right in front of me. She's somebody I know. There's nothing queer about her. She just wants to get away from that man, and get a little peace and quiet in the country. That's natural.

She's pretty friendly with that driver... Maybe he's a friend of hers. He's got white hair, but he doesn't look old. He's got a hole in the elbow of his sweater. Well, that's nothing. Some people don't care. I've heard about millionaires that look like regular tramps.

She made an effort to go to sleep, she leaned back and closed her eyes. But the road was very bad now, she was jounced and shaken, she felt the car skid and slew around, she opened her eyes and the car stopped. The white-haired man was getting out.

There was nothing here, nothing but rain and the dark. She thought something must have gone wrong with the car, nothing serious because Miss Dolly sat smoking there, with no gesture of alarm or even curiosity. The rain dashed against the windows as if flung from a bucket; it was surprising to think of the white-haired man out in it without hat or coat.

And then a light sprang up and outlined a window, she could see the dark bulk of a house. In a moment the man came back, running, with a blanket held against his breast; he opened the door to the front seat, and Maggie saw Miss Dolly laugh, her teeth white against her rouged lips. She moved over, and the man put the blanket over her head and around her shoulders, he took her arm and helped her out.

Maggie sat close to the window; she saw them run along a path and up the steps of a little porch, the man opened the door and they went in.

Well, have they stopped in to visit somebody? Maggie thought. If I'm a secretary, it's a sort of funny way to treat me, going off and not saying a word. But I never really believed much in all that. She sat there waiting in drowsy discomfort, yawning in the close dampness. Then the door of the house opened and the man appeared in the light, waving his arm as if scooping something out of the air toward his face. She watched him for some time before it occurred to her that he was beckoning to her.

Well, that's not very polite, she thought, and taking up her little bag she opened the door and got out in the pelting rain. It was too dark and too slippery to run, she went cautiously along the path and up the steps.

"Look here!" said the man. "Get something for Miss Camford to eat, will you? Just a little snack—coffee—anything. Here's the kitchen. Take anything you see."

His hair was not white, but a pale blond; he was young, with a broad, strong-boned face, and pale eyes that rested on her for a moment with impersonal coolness.

"Here's the kitchen," he said again. "Call me if you want anything."

She went into the room he pointed at, a dim and dirty kitchen lit by a feeble bulb hanging from the ceiling, with a bare wooden floor, an oil-stove furry with grease, a narrow iron sink. She set down her bag and looked around her, and narrowed her eyes to keep from crying.

All right! she said to herself. All right! I was a fool to come. I might have known... But here she was, and she accepted the consequences grimly. She opened her little bag and put on her apron, she looked around and found a paper bag of coffee, she found a battered old aluminum coffee pot; there was a small wooden ice-box in a corner, and in it she found ham, and butter and eggs, and some ants running around. I wouldn't work for the woman who runs this house, thought Maggie, not for fifty dollars a week. I never saw—

"For God's sake..." said a voice behind her, and she turned quickly. A man in a dressing-gown stood in the doorway, a big, sun-burned, grey-eyed man, staring at her, and yawning like a big cat. "For God's sake, who are you?" he asked.

"I'm—I came with Miss Camford," said Maggie briefly.

"Susanne," he said. "The dainty little French maid."

"I'm not French," said Maggie.

The man ran his fingers through his dark hair, and it stood out like feathers behind his ears; he leaned against the doorway, and Maggie noticed with disfavor that his feet were bare.

"You're pretty," he said earnestly. "You're the cutest little trick I ever saw. Red hair, too. Are you saucy?"

With all her heart she resented his words, his tone, the way he was staring at her. She went on with her work, trying to ignore him.

"I bet you slap people," he said. "Fresh guys. Piff. Paff. Pouff. Non?"

There was a loaf of bread on a shelf, not wrapped, just out there in the dust. It was stale, too, hard as a rock, she sawed away at it with a knife.

"You're pretty," he said, "but not very polite. After all, when a pretty little girl all dressed up like Susanne suddenly appears in my kitchen in the middle of the night, I think she ought to speak."

"Is it your kitchen?" said Maggie.

"Half of it's mine," he said. "It happens to be the half you're in now."

"Where do you want supper served, please?" asked Maggie.

"What supper?" he said. "The only thing is, you ought to wear silk stockings instead of cotton..."

She looked at him with scorn in her blue eyes.

"Aha!" he said. "I knew you were saucy."

This was too much for her.

"I'm not saucy," she said. "I'm here doing the work I'm paid to do—and minding my own business. If you feel like standing there and making fun of me, I can't stop you."

He straightened up.

"I wasn't making fun of you," he said. "That's just a cheap idiot way I have. Meant to be amusing... Meant to hide my sensitive spirit. Cassidy is the name. Johnny Cassidy."

The kettle was boiling and she made the coffee; she began to butter the rock-like bread, and to make ham sandwiches. She was not a bit tired or confused now; she was deft and quick and perfectly sure of herself and she felt ready to go on working for hours in a sort of rage. I'd like to scrub the floor, she thought, and clean up this nasty dirty place. That man can stand there staring just as long as he likes. I don't care.

"Oh, Maggie!" said Miss Dolly's voice. "Oh, you poor child! What are you doing?"

"Getting some supper, Miss Dolly."

"But it's three o'clock, Maggie. You must be worn out."

"I'm not tired, Miss Dolly."

"You're not to do another thing," said Miss Dolly. "Come on, and I'll show you your room."

"I'll just finish—"

"You come along this minute," said Miss Dolly, and took her hand.

"May I ask for an introduction?" murmured Johnny Cassidy.

"This is my secretary, Miss MacGowan," said Miss Dolly, with more than a trace of curtness. "Do come along now, Maggie. What put it into your head to start all this at such an hour?"

"The—other gentleman asked me to," said Maggie.

"Neely?" said Miss Dolly. "Oh, he hasn't any sense of time at all. This way, Maggie."

Maggie picked up her bag from the corner, and Johnny Cassidy took it from her.

"No, thank you," she said. "I'd rather—"

But he went ahead of her out of the kitchen and up a steep and narrow stair; he mounted these, limber and nimble in his bare feet. He put the bag in a room and came out, and stood aside.

"Good night, Miss MacGowan," he said.

Miss Dolly closed the door and they both looked around them at the room. It was a big room, low-ceilinged, furnished with a big divan, a wicker chair, a bamboo table, some shelves of books, and a tall old-fashioned radio cabinet. Here too, the only light was from a bulb hung from the rafters; it was gloomy, shadowy, smelling of mold.

"We can fix it up tomorrow," said Miss Dolly. She crossed the room to the divan and pressed it with her hand. "It seems very comfortable," she said. "My room is just in here through this door, and the bathroom is just across the hall."

"Thank you, miss," said Maggie.

"Don't call me 'miss' any more. Call me Dolly, won't you, Maggie?"

"I'll try to," said Maggie.

"It's going to be nice here, don't you think, Maggie?"

"Well, it's hard to judge yet, Miss Dolly."

"Please call me Dolly! We're going to have a wonderful summer here, Maggie. We'll change things, and make the place charming."

"Excuse me, Miss Dolly, but—isn't there any—any lady of the house?"

"No," said Miss Dolly. "It's Neely's house. He's an artist, you know, and very talented. I didn't know Johnny Cassidy would be here. But I don't think he'll stay long. He never stays anywhere."

"There's just Mr. Cassidy and Mr. Neely?"

"Curtius. Cornelius Curtius. He's a Dutchman, Maggie, from Holland. You'll like him."

"Yes, miss."

"But you will call me Dolly, won't you? You've come here as my friend, Maggie."

"I'll try," said Maggie.

"Let's go to bed," said Miss Dolly. "We're both tired."

She smiled at Maggie a little anxiously, and after a moment she went off into the room that opened out of this big one. She came back almost at once.

"Maggie, could you possibly help me with the bed? It seems so queer."

There was nothing at all in the little room but a white iron double bed and a chest of drawers. And the bed was queer because the covers were not tucked in, but just folded on top of it. Maggie made it neatly while Dolly began to undress.

"Now I'll go and wash," said Miss Dolly, "and then I won't have to disturb you by going through your room again."

She had left her things scattered all over, her lovely delicate underwear, her little gold watch and her sapphire bracelet tangled up in her stockings on the chest of drawers. Maggie made the room as neat as she could before Miss Dolly came back. She looked surprisingly pretty and glowing, in a white terry robe, her black hair loose about her olive-skinned face.

"It's going to be lovely here, Maggie!" she said.

"Yes, miss," said Maggie. "Good night!"

She went back to the big room, closing the door softly behind her. She was not going to take off even her apron when she went to the bathroom to wash, not she! Not when she and Miss Dolly were alone in this house with those two men. Queer men...

She returned to the big room, and she wanted to lock the door. There was no key in the lock, no bolt. She fixed a chair under the knob, and took the faded green cover off the divan. Nothing under it but a mattress, no sheets, no blankets, nothing at all.

She did cry a little then, but while the tears ran down her freshly-scrubbed cheeks, she was busy. She put the green cover back, she fluffed up the pillows, she took off her apron, her black dress, her shoes, she put on her dark-blue dressing-gown and her felt slippers, she brushed her hair, one hundred strokes, and then she went to the shelves to get a book. For she had decided to sit up all night.

She found a novel that seemed nice, and she found a tabloid newspaper of yesterday's date. She sat down in a chair, determined to read, and the first thing she saw in the paper was a picture of the murdered Mrs. Amber, smiling, with her hair in a cloud about her face. Police of Two Cities Seek Clubman for Questioning, she read; and there was a picture of the Clubman, looking as he ought to look, dark and handsome, with a neat little moustache. Arthur Curran, Socialite and Sportsman, Evaded Police in New York and Boston Today. Friends think he has gone to Florida to avoid publicity in connection with the death of Mrs. Sally Amber, found partially clad.

I'm sick and tired of that case, Maggie thought. She brought it on herself, Mrs. Crabtree said... They all do, she said... By getting mixed up with some man, one way or another.

And what's Miss Dolly doing?

Coming out here to this nasty dirty queer house with these two men in it. What kind of men are they, I'd like to know? They could be blackmailers—or anything. I don't believe Miss Dolly's any judge. She seems so happy... I never saw her smiling and laughing before... I suppose she thinks she's safe now.

Well, I don't. No key in the door. I hope to goodness there isn't any kind of balcony outside the window, she thought, and rose hastily. There were some french windows at one end of the room; they would be the dangerous ones. There was a key in the lock there, she tried it and pulled the window open. And there was a balcony; the light gleamed on wet planks.

She put on her shoes and threw her coat over her shoulders, because she wanted to see, she would see, what there was out there. The rain drove at her in a slanting sheet and she stepped carefully to the railing. She saw no lights, no trees, only the dark sky. She glanced down, and there, directly beneath her she saw a sheet of black water. She could hear it lapping against the wall underneath the planks where she stood.

A house—right in the water...? She leaned over the rail, staring, half-incredulous, but it was true; that was water, moving water. Something flounced in it, making a little curl of white; something alive.

She went back into the room and locked the window, and because everything was so dreadful and so miserable, she rebelled against it. Nothing to be afraid of, she told herself, sharply. She knelt down and said her prayers, and turned out the light.

The big room was black as the pit. Very well. Everybody goes to sleep in the dark except cowards. Still in her dressing-gown and slippers, she lay down on the divan. The wind came in gusts, the rain spattered against the windows, and when a little lull came, she could hear the water lapping against the wall.

All right. She wasn't afraid of water. If something flounced again, it was a fish. Natural for there to be fish in the water, and I suppose night is the same as day to them, she thought. It'll be morning pretty soon. I'll get some sleep, and the first thing it'll be light again.

She felt cold, and she curled herself up in her coat. The wind blew and the rain poured down, and the dark water lapped, and she went to sleep.

IT'S a miserable thing not to have a watch, thought Maggie. It was certainly day, but the rain still fell, a steady drizzle now from the grey sky; it might be early morning, and it might be late. Back in New York you could tell by the sounds from the street; here there were no sounds, not even the lapping of the water any more.

She put on her clean blue cotton dress to go to the bathroom; she took it off to wash and put it on again. She was not going to meet those men in any dressing-gown. Then when she was all neat and trim, she went down the narrow stairs, quietly but not timidly. She felt that she had been deceived and shabbily treated; 'put upon,' she called it in her mother's phrase, and that warmed her heart with a good, steady anger.

The nasty dirty house was chillier and mustier than ever; she went through the room at the foot of the stairs, glancing at it with scorn, a sort of dining-room it was with a cheap golden oak sideboard cluttered with unbelievable things; she saw a red satin slipper there, two empty brandy bottles, a dying purple flower in a pot, a blue lustre horse, an iron bank modeled after the Statue of Liberty. Plenty of other things too, but she did not trouble to examine them, she went on into the kitchen, and it was just as she had left it last night; no one had touched the coffee or the sandwiches, nothing had been put away.

She put on the kettle to make tea, and then she opened the back door. There was a little porch out there and a sort of wooden tunnel roofed over by the upper story of the house and filled with dark, lapping water. On one side a ramp led up to a steep bank, there was an iron stanchion there to which a rowboat was tied, and beside this was a little launch at anchor.

And through the tunnel she could see a path of water running through flat marshes; everything was flat and grey and empty. But the damp air was salty and good, she was glad to breathe it, she was glad to see a gull swoop low over the reeds. This was a place you could get out of, it was lonely enough, strange enough, but it was no longer a nightmare.

She left the door open while she ate her breakfast of tea and stale bread. It did not seem to her proper to take any of the other food in the kitchen; only bread was always proper, it was what you had a right to take. Now then... she thought. I don't know... I'll wash the things I've used myself, of course; but I don't know if I'll clean up this nasty kitchen before I go, or not.

Go she would, as soon as Miss Dolly waked up, no matter how much she talked about being a secretary, and having a lovely summer. Of course I can't ever go back to Mrs. May-field now, after going away like that without a word, she thought, and maybe she won't even give me a reference. But I guess I can get another position like that in a nice house, and I've got twenty dollars saved up. I guess I could make out for two weeks if I have to.

The prospect did not daunt her in the least; she would have gone back to New York with a half, with a quarter as much money, and not been seriously worried. She knew she was a good worker, she knew she could do things people were glad to pay for; she was young, healthy, nimble, and she had great faith in herself. I'll walk to a railroad station if I have to, she thought; but this very day, back I go.

She looked at the sink, narrowing her eyes. Oh, well... she thought. I will clean up everything. I've just got to, that's all. She filled the kettle again, and she had begun to rinse the dishes when there was a knock at the door. As a matter of course she dried her hands and went to open it.

A taxi was just driving away, and a man stood on the porch, a portly, clean-shaven, white-haired man with a square jaw and stern blue eyes.

"Will you kindly tell Miss Camford that Mr. Angel is here," he said.

"Miss Camford isn't up yet, sir," said Maggie.

"I'm sorry," he said, "but I'm afraid I shall have to disturb her. If you'll tell her that Mr. Angel is here—"

"Does she—excuse me, sir; but will she know the name?"

He smiled a little.

"Undoubtedly," he said. "I am Miss Camford's lawyer."

A fine looking man, and handsomely dressed, a man to be credited. "Will you step in, sir?" said Maggie. "This room isn't very tidy, sir, but we just got here."

Mr. Angel looked about him at the dining-room with a distaste that pleased Maggie, he took off his hat, and he was drawing off his grey gloves as she started up the stairs.

Miss Camford's lawyer? she thought. Well, somebody's found out where she is, and pretty quick, too. Well, it's a good thing. I hope they make her leave here. It's no place for her. She knocked on the door of Miss Dolly's room, and getting no answer, she opened the door. And she was somehow touched by the look of Miss Dolly asleep with her black hair spread out on the pillow, and her face so pretty and so serene.

"Miss Dolly! I'm sorry, but Mr. Angel's here, Miss Dolly!" Miss Dolly opened her eyes and looked blankly up at Maggie.

"What?" she said.

"Mr. Angel is here, Miss Dolly."

"Mr. Angel?" she repeated. "But, Maggie!" She sat up in her lovely ivory silk nightgown with a yoke of écru lace. "Mr. Angel? But he couldn't be!"

"Well, he is, Miss Dolly," said Maggie.

"But—where is he, Maggie?"

"He's in that dining-room, Miss Dolly."

"Maggie, are the boys with him?"

"The boys, miss?"

"Neely and Johnny. Are they talking to him?"

"No, miss. I don't think they're up yet. They didn't get any breakfast for themselves anyhow."

"Let me think a moment..." said Miss Dolly. "Wait..." Maggie. Bring Mr. Angel upstairs."

"Up here?" said Maggie in stern astonishment.

"Yes. Up to the sitting-room. The room you slept in. Hurry up, Maggie! And don't tell the others he's here until I've had a chance to talk to him. Hurry up, Maggie!"

And why? thought Maggie. What's all this hurry and worry about, I'd like to know?

"Maggie, hurry!"

"Yes, ma'am," said Maggie without any expression.

She closed the door as she went out, and she took time to tidy that room, to put everything belonging to her out of sight; then she went down to Mr. Angel. She found him standing with his hands behind him looking at the sideboard. "I suppose you have a telephone here," he said.

"I don't know, sir," said Maggie.

"I hope so," he said. "I shall want it to send for a taxi presently. I'm obliged to be back in New York for an appointment. That's why I came at such an early hour. Miss Cam-ford coming down soon?"

"She'd like you to come upstairs, please, sir."

"Upstairs?" he repeated, with a look that Maggie observed with understanding and sympathy. "Miss Camford—er—she's not feeling well?"

"There's a kind of sitting-room upstairs, sir," said Maggie. "This way, please."

She led him into that sitting-room, and knocked at the bedroom door.

"Maggie?" said Miss Dolly. "Come in!"

She was wearing a dark-red housecoat with a high collar, and her hair was tied back from her forehead with a ribbon to match; she looked wonderfully tired and gentle, and wonderfully young.

"Look, Maggie!" she said. "Here's a little note for Neely. His room is the first door on the right beside the stairs. I'm asking him to drive you down to the drug store right away to get this prescription filled."

"Miss Dolly... If he could go by himself... I haven't got the dishes washed yet."

"That doesn't matter. I'd rather you took the prescription for me, Maggie."

Well, if it's something sort of confidential... thought Maggie. But how much she did not want to go knocking at that Neely's door! How much she hated all of this, the dirt, the disorder, the general queerness... She knocked, and he called out at once. "Who is it?"

"It's—me," she answered.

He opened the door, and she was relieved to see that he was dressed. "Oh, it's you!" he said. "Miss—what is it?"

"MacGowan," said Maggie. "Here's a note for you from Miss Camford, Mr. Curtius."

He unfolded the piece of paper and read it.

"All right!" he said. "Come along."

"I'll get my hat and coat, Mr. Curtius."

"Don't bother," he said impatiently.

"I won't be a minute," said she.

"Dolly wants the medicine at once," he said. "I'll wait for you outside in the car."

She knocked at the sitting-room door and there was no answer. She knocked again and waited, knocked louder. Well, for goodness sake, she thought. Has she gone and got him into the bedroom? She opened the door and entered and the room was empty. All right! she thought. It's none of my business. She got her hat and coat out of the closet, and then as she turned away, she saw Mr. Angel out on the balcony, standing by the rail. The rain had stopped, the grey sky was growing light. He had his hands clasped behind his back again, his white head was raised; he looked sort of noble, she thought, like a senator, or something.

She ran down the stairs and out of the house, and Neely was sitting at the wheel of the big car. For a moment, Maggie hesitated, but he did not open the door or suggest her sitting in front with him, so she got into the back seat. She could see now how isolated that queer house was, standing almost in that river that was not exactly a river but a slow current winding through the marshes.

They turned away from that and along a road slippery with mud, and lined with fields of grass yellow and stunted; no trees, no houses. But when the sun came out, this flat and empty world grew gay, there were dandelions and clover, there was a sweet freshness in the air. They came presently to a highway and filling stations, and diners and a little house here and there, and then they came to a street in a village, tree-shaded, tranquil, with a public library behind a grass lawn, a squat, white-pillared post office, a drug store on the corner. Neely stopped the car, and Maggie got out. I like it here, she thought. This is a nice place.

A thin man in his shirt-sleeves, with spectacles a little down from the bridge of his nose, took the prescription and studied it.

"Take me half an hour," he said. "D'you want to wait?"

"Yes, thank you," said Maggie. "Could I get a soda?"

"Yes," he said calmly.

Neely sat down beside her with his hands in his pockets.

"What's wrong with Dolly?" he asked.

"I don't know," said Maggie.

She did not care for Neely, she did not like the careless way he dressed, she did not like his rude, indifferent ways; she glanced at him and found his pale-blue eyes looking her up and down with no light in them.

"You have good bones," he said.

Well, if that's all he finds to admire in me... thought Maggie. Bones... The druggist had set the chocolate soda before her, and she began to drink it through a straw, giving it her whole attention.

"I'll come back for you," said Neely abruptly, and went out of the store; through the window she saw him get into the car and drive away.

Well, I don't know... Maggie thought, sipping the soda. It's certainly not what I expected. I just hate that house, and I don't like these two men, but still... It's experience, and if I help Miss Dolly with her book it'll be a reference, and I can get a really nice job. It's queer, and Miss Dolly's acting queer, I must say, getting so lively and cheerful all of a sudden. You'd think she'd forgotten all about that letter about the vitriol... If Mr. Angel could find out so quickly where she had gone, that Othello man might find out too... I don't know. There are lots of things I don't like, but I'll guess I'll stay.

"Here's your eye lotion, miss," said the druggist. "Forty-five cents, that'll be."

Maggie took the bottle and counted out the money. Eye lotion? she thought. Sending me off in such a hurry for that? I never heard her say anything about any trouble with her eyes. No... It was just to get that Neely out of the house while Mr. Angel was there. And I suppose she wanted me to go with him to make it look more reasonable. Well, I don't wonder she didn't want Mr. Angel to see Neely. I don't know what Mrs. Mayfield and Mr. Camford would say if they knew she was living in this nasty dirty house with two men.

She finished the soda very leisurely, and she looked around for a clock, and saw none. "Excuse me," she said to the druggist, "but can you please tell me the time?"

He took a big watch out of his pocket. "It is now—" he said deliberately, "a—ten forty-five."

"Thank you!" said Maggie.

She was getting a little tired of looking out of the window; she got up and walked about the store looking at the soap and powders, she took up a booklet about kidney pills, and read the testimonial letters in it, she went back to the window and looked out at the street where two girls in summer dresses went by, arm-in-arm. Neely's taking a long time, it seems to me.

The time grew longer and longer, the sun grew hotter. She did not like to ask the druggist to look at his watch again; she sat on a stool, she got up and went to look at a case full of cigars, the box lids up, displaying colored pictures of Indians and beautiful girls in white robes with long black hair, reclining under palm trees. A whistle began to blow.

"Excuse me," she said to the druggist, "but is that for noon?"

"That is the noon whistle over to the mills," he said.

It's certainly time Neely came back, she thought. And what if he doesn't come at all? Why, I don't even know where the house is. I don't know where I'm living. She went out into the street then, and looked up and down; there was a stationer's nearby and she went there and bought a little magazine full of condensed articles. You get a lot of information from things like that, she thought, and if I'm going to be a secretary, I want to be able to talk about what's going on.

She went back to the druggist's and sat down again. The druggist went away, and a dark and gloomy boy in spectacles came to take his place. I'll read this one article about high-lighting your personality, thought Maggie, and then I'll find out how to get back by myself.

But Neely came just before she had finished.

"You were certainly gone a long time," said Maggie.

"What of it?" said Neely. "There's no hurry."

"Speak for yourself," said Maggie. "I've got things to do."

"To wash dishes?"

"No," she said briefly, and they went out and got into the car.

"I don't know why she brought you here," said Neely.

It's none of your business, thought Maggie, and did not answer at all.

They drove the rest of the way in silence; when they reached the house he jumped out and ran up the steps and opened the door. Maggie followed with a proud lack of haste; she looked into the dining-room and the kitchen; nobody was there, she went up the stairs and found no one there either. She started to make Miss Dolly's bed when Neely called from below.

"Maggie, look here! Come here, will you?"

She went into the hall and leaned over the stair railing.

"What do you want?" she said, coldly.

"Can you row a boat?" asked Neely from the doorway.

"Yes," she answered.

"Then, will you row me somewhere?"

"I can't," she said, "I've got work to do."

"It won't take long," he said. "I've got to take a bundle somewhere."

"Take it in the car," she said.

"I'm out of gas," he said. "Come on, please. It's only a little way."

"My goodness!" said Maggie, unsteadily. "You people don't care—what you ask me to do."

"I don't know how to row," he said, as if that explained everything.

She had reached a stage in which she would have refused him flatly if it had not been for one thing. She had a passion for small boats. Her father had taught her to row and to paddle when she was a little girl; he had taught her a little about sailing, too, and she had taken to it with ecstasy. But he had died at sea, and there had been no more time or money for recreation.

"All right," she said, "if it's not far."

It was warm now in the afternoon sun and she did not bother with hat or coat. She went out with Neely to the ramp at the foot of which the rowboat lay.

"What's that?" she asked frowning.

"It's a mannikin," he said, "a dummy someone lent me to draw from, and I've got to take it back."

It looked like a body, she thought, that long thing stretched out on the bottom of the boat covered with a tarpaulin. It was queer, but everything these people did was queer. She went down the ramp and got into the boat, sure-footed and happy to feel the lift of it under her feet; she sat down and took the oars, and Neely got in awkwardly. She could look right into the kitchen window.

"I never saw a house so close to the water's edge before," she said.

"It used to be a boat-house," Neely said. "They fixed it up for the summer people."

"Which way do we go?"

"Left," he said, and she began to pull on the oars, easily and strongly, going through the dark tunnel out toward the bright glittering water. The last time I went out with Father... she thought. We were so happy that day... If I'd been a boy I'd have gone to sea. I'd have been a captain some day like Father.

They came out of the wooden tunnel, and turning left they came into a part of the river she had not seen from the house; it was far more like a real river here, with higher banks.

"The current is strong here," she said.

"It's tidal," said Neely. "The tide's running out now."

"Salt water?" she asked.

"Oh, yes," he said.

The sun was hot on her head and shoulders, the breeze was fresh against her face. Oh, this is lovely, she thought. Oh, if only I could make a living doing something like this! I'd never feel tired.

The banks were growing steeper, and now she saw a willow.

"Isn't that pretty!" she cried.

Neely did not answer; he was trying to light a cigarette, but the match blew out, and he threw it into the water. It was quiet here; the sky was so blue. The river made a turn, and the boathouse was lost to sight, there were more trees stirring in the wind. It's lovely! It's lovely! she kept saying to herself.

Neely was trying again to light a cigarette; he stood up straddling the bundle, he swayed clumsily.

"Sit down!" she said, sharply. "You'll tip the boat over."

He lost his footing and fell, grasping the side of the boat and capsizing it. Maggie was tumbled out on the surface of the water, the chill of it made her gasp. She swam a stroke or two, and put her hand on the drifting boat and looked for Neely. He was standing in water up to his waist, just standing.

"Catch those oars!" she shouted, but he did not stir. "Mr. Curtius!" she cried. "Help me to turn the boat over or we'll lose it."

But he didn't do anything. She stood up then, and she shuddered a little to find thick soft mud under her feet. She struggled with the boat, but it was very heavy.

"Why don't you help me?" she cried.

With an effort she lifted the boat, but it came down into the water again. Then something drifted by her. It was Mr. Angel, floating on his back, going slowly down the stream; the current caught him, and his arms went back behind his white head as if he stretched and relaxed in great comfort, sinking a little below the surface.

"OH...stop him!" she cried.

Neely reached for one of the oars that was floating away; he waded a few steps to catch the other oar. But he didn't even look after Mr. Angel.

"Help me—to get him!" cried Maggie.

"No. He's dead," said Neely.

"He's going out to sea!" she said in horror, and turned to go after him. The mud was too thick; she lost one of her shoes, and the feel of the mud was sickening. She began to swim after Mr. Angel, and in spite of her clothes she went fast, helped by the tide. She came up with him and took hold of his sleeve. A matter of two or three strokes would bring her to the bank and she could get him out of the water.

But a rough hand had seized her by the shoulder and pulled her backward, so that Mr. Angel escaped and went on his way.

"Don't be a fool," said Neely, standing beside her waist-deep in the water. "He's dead."

"I know that," said Maggie. "But I want—"

"You can't do him any good," said Neely, "and you'll do Dolly—and all of us—a lot of harm. Yourself, too."

She was on her feet now in that thick hateful mud; she tried to free herself, but he held her fast.

"I don't let him go out to sea!" she said.

"Look here! He had a fit or a stroke or something like that. I found him in the boat dead, so I wanted to get rid of him."

"You ought to know better!" said Maggie. "Let me go! You'll get in a lot more trouble with the police, acting like this. Let me go! It's everybody's duty to tell the police—"

"Why?" he asked.

The boat was coming along, and he stopped it. "Let's go home and forget it," he said. "Nothing we can do."

"You're awful!" she said. "I won't do it. I'm going to get Mr. Angel—"

"Angel?" said Neely. "Is that his name? Really his name? Angel?" He grinned from ear to ear. "Angel's on his way to heaven," he said. "That's a good one."

"You ought to be ashamed of yourself! You let me go this minute. I'm going to get poor Mr. Angel out of the water, and then I'm going to tell the police."

"What makes you such a fool?" said Neely. "Let Dolly have her party, anyhow."

"Party! Her party!"

"It's important. She's got important people coming."

Maggie began to struggle in earnest to get away, but he was very strong.

"Stop!" he said, not much interested. "Let's turn the boat over and get into it. Silly to be standing here in the water. You look funny."

"You're not—human," said Maggie.

Mr. Angel was out of sight now; either he had disappeared around the bend of the river, or he had sunk to the bottom.

"Come on. Let's go home," said Neely.

"I'm going to find Mr. Angel," she said, "and you can't stop me."

"I will stop you," said Neely. "I don't want you to find him. I want to go home. I want you to row me back."

"I won't," said Maggie.

"Oh, you're a nuisance!" he said angrily.

He let the oars, which he had held under his arm, drop into the water, he gave the boat a shove, he let Maggie go, and he began to walk toward the bank. "If you tell the police," he called back, "you'll get yourself in a hell of a lot of trouble, and I'll say it's all a lie. I'm not going to get mixed up in this for any dead angels."

She stood there in the mud and the cold running water with the sun blazing down upon her, not a house, not a living thing in sight, except the broad-shouldered, sturdy figure of Neely making his way across the marsh. Her teeth were chattering with cold, she clenched them and began to swim after the boat. She reached it and went along beside it sometimes swimming and sometimes wading; she caught the oars and pulled them along with her.

She went round the bend of the river, and the boathouse was in sight. But not Mr. Angel. She could see a long way ahead of her, but not a sign of him. She was utterly alone in the empty, sunny world; she was so cold... An idea began to come into her head. She tried to banish it, but in vain. If poor Mr. Angel had sunk to the bottom of the muddy water...

She swam the rest of the way, juggling both the boat and the oars, shoving them ahead of her into the dark tunnel underneath the balcony. Even in here she could not, and would not set foot on the bottom. She took the painter of the boat in her teeth and scrambled up the ramp; she made the boat fast and took in the oars. And she did all this because it was not in her to waste or destroy anything, and because she had a particular respect for boats.

Shivering and dripping, limping with one shoe on, she went round to the back door. She took off her shoe then, and wrung out her skirts and went up the stairs to the big room. There was no hot water in the bathroom, and she could not face a cold bath; she scrubbed herself with soap and a damp towel, she put on clean underwear and her felt slippers and the black poplin dress. Now I'll call up the police, she told herself.

She looked upstairs and down for a telephone until there was only one place to look. She knocked at Neely's door.

"Come in!" he said, and she opened the door.

Barefoot and in singlet and dark trousers, he was standing at a high tilted board, drawing with a piece of charcoal.

"Well, did you find your angel?" he asked.

"I'm looking for a telephone," said Maggie, briefly.

He put down the charcoal, and thrust his hands into his pockets, frowning; she noticed that his thick lashes were silvery when the sun touched them.

"My God!" he said. "I think I have a hole in my pocket. I must have dropped that telephone in the water, maybe; isn't that too bad?"

"Do you think there's anything to be funny about?" asked Maggie.

"To cry about then?" he asked. "Too many people getting killed in the world now. If some old fellow has a fit and tumbles down dead in a rowboat, all right. He's lucky. He lived a good long time, and he died easy."

There was something foreign in his speech now, not an accent, but an inflection, a choice of words, he looked foreign, too.

He took up the charcoal and began to draw again, and Maggie left him. She was completely at a loss now. There was undoubtedly a telephone to be found somewhere along the highway; but that was a long, long way to go in felt bedroom slippers. It would take a long time, too, and what would be happening to Mr. Angel in the meantime? She felt the sharpest distress to think of him, in all his dignity and decency, hurried off upon that shocking journey. He must be brought back, treated with respect and kindness.

Miss Dolly and that Mr. Cassidy will be back soon, she thought. I'll just have to wait for them, and then they can telephone. In the meantime she could get a little work done. She descended to that kitchen again, angry at it, yet with a certain grim enjoyment in the challenge it offered.

The doorbell rang—she dried her hands and took off her work apron, and went to answer it.

A very stout lady stood on the porch.

"Tell Miss Camford Miss Plummer is here," she said affably.

"I'm sorry, ma'am, but Miss Camford isn't in just now," said Maggie.

"She ought to be back by this time," said the other. "Well, I'll come in and wait."

She was a cheerful and amiable lady, dark-haired, in a gay print dress and a dark coat, and sensible low-heeled shoes, and a straw hat coming far down on her face. She looked funny, so stout and in such bright colors, but she looked, Maggie thought, like a lady.

"Miss Camford didn't leave any word for me?" she asked.

"No, ma'am," said Maggie, and Miss Plummer entered the house.

"Mon dieu!" she cried stopping in the doorway of the dining-room.

She turned to Maggie. "Do you know—?" she asked, "What they've done with all my things?"

"No, ma'am," Maggie answered. "I just came yesterday."

"What's your name, my dear?"

"It's Maggie, ma'am."

"Irish!" cried Miss Plummer.

"No, ma'am," said Maggie. "I'm Scotch. On both sides."

"Oh, dear..." and Miss Plummer. "Edinburgh... A magic city... What can they have done with the faience hen, do you know, Maggie?"

"No, ma'am," said Maggie, and withdrew into the kitchen.

She was not sure that she had done the right thing. Perhaps she should have told Miss Plummer about Mr. Angel and asked her advice. Through the half-open door she could see her moving about, shaking her head in consternation; her house, it seemed to be.

A car was coming now, she heard footsteps on the porch, and before she could reach the door, Miss Dolly had come in followed by Mr. Cassidy with his arms full of packages.

"Oh, Mitzi, you darling!" cried Miss Dolly. "Were late, but we've bought fine things... Excuse us one minute, will you?"

She caught sight of Maggie then, and she came toward her and prevented her getting back into the kitchen, and closed the door.

"Maggie," she said. "Come upstairs with me—"

"Miss Dolly, I've got something to tell you—"

"Tell me upstairs. Please come along, Maggie!"

Maggie followed her up the narrow stairway to the big room, and Miss Dolly went on into her bedroom.

"I've got a little dress here—" she said.

"Miss Dolly, something's happened."

"Well, what?" asked Miss Dolly bending over her suitcase that was open on the bed.

"Mr. Angel... Mr. Angel—met with an accident," said Maggie.

"Oh dear!" said Miss Dolly. "The poor thing told me he wasn't feeling at all well when he was here. Maggie, look! Put this on."

She held up a dress, a new dress she had bought only a few days ago.

"Miss Dolly," said Maggie. "I'm sorry to tell you, but Mr. Angel is dead."

"Oh, heavens!" said Miss Dolly. "I suppose he had a heart attack. I'm terribly sorry. But I've got to speak to you now about this afternoon, Maggie. It's terribly important for me."

"Miss Dolly, we'll have to do something about Mr. Angel, first."

"Do something? But, if he's dead—"

"He was—in the river, Miss Dolly; floating away out to sea."

"Maggie! You mean, drowned?"

"No, Miss Dolly. Mr. Curtius found him in the rowboat, dead, and he tipped over the boat. I—think he did that on purpose. I'm quite sure he did. And he wouldn't help me to stop Mr. Angel."

"Stop him?"

"He was—going out to sea," said Maggie swallowing hard. "I went after him—but I couldn't find him. If we got the police—quick—they could drag the river—"

"Yes, we will," said Miss Dolly. "What a dreadful thing! But now, Maggie, put on this dress will you?"

"What for, Miss Dolly?"

"Maggie, I told you I wanted you here as my secretary. I want to introduce you to these people this afternoon. Put on the dress; it's brand new, and I think it will suit you."

"I'm sorry, Miss Dolly, but I just couldn't," she said.

"Maggie!" cried Miss Dolly. "You can't possibly refuse to help me!"

Can't I? thought Maggie.

"Maggie, this is a really important day for me," said Miss Dolly.

An important day for Mr. Angel, too, thought Maggie; but that doesn't seem to bother you much.

"Please remember," said Miss Dolly. "These people are coming here—and I can't let them get the impression that I'm staying alone in the house with two men."

"Well, they'll see me here, ma'am."

"But it isn't the same, Maggie! If you're—" She paused, and by the pause, the effort to put the matter tactfully, made it doubly offensive to Maggie. "Anyone can see what an absolutely honest, straightforward girl you are—and if people felt that we're friends—that—that we're confidential together..."

"That lady downstairs knows I'm a servant," said Maggie. "I let her in, and I told her my name was Maggie."

"Oh, she doesn't count," said Miss Dolly. "She doesn't notice anything. Oh Maggie, do please hurry up and get ready before the Gettys come!"

"Miss Dolly, something's got to be done about Mr. Angel."

"Of course! I know it. I'll send someone—I'll send Johnny Cassidy to telephone to the police."

"Right away, miss?"

"Yes. The moment I've got you ready."

"I don't need any getting ready, Miss Dolly."

"How can you be so stubborn?" said Miss Dolly. "I've tried to be nice to you, Maggie. I asked you to come as a secretary, and you agreed—"

"I can be a secretary, miss, without dressing up in somebody else's clothes—"

"The Gettys will think I'm a bitch," said Miss Dolly.

What a word to call your own self! thought Maggie. But it impressed her; she felt a reluctant sympathy for Miss Dolly in this dilemma. Nobody wanted to be talked about, she thought. I don't think she ever ought to have come here to this house; but here she is.

"I didn't understand what you meant," she said. "Or I'd never have come."

"But it's too late now for me to do anything. Maggie, please...!"

"All right, miss," said Maggie. "This once."

It was a lovely dress; Maggie had seen it the day it came from the shop, and it cost forty dollars... A sort of long-waisted effect, and a yoke over the hips and a pleated skirt. "But my shoes, Miss Dolly. I lost a shoe in the mud—"

"Try these," said Miss Dolly.

Maggie tried on a patent leather pump.

"It's too big for me, miss," she said with quiet satisfaction.

"Well, it's a little too long," said Miss Dolly. "But it's not too wide. I have very narrow feet."

"Yes, miss," said Maggie. "So have I."

"Well, here, try this," said Miss Dolly, taking off her suede sandal.

"I guess I can make these do, miss," said Maggie, "if I fasten the straps in the very last holes."

"Please remember not to call me 'miss.' Call me Dolly."

"I couldn't, miss. I could say Miss Camford."

"All right!" said Miss Dolly with a sigh. "Now let's see... Your hair's perfect. You have very nice hair, Maggie."

"It's naturally curly," said Maggie.

"Here! Here's a new lipstick, Maggie. I'm afraid it's a little dark, but try it, won't you?"

Maggie made no objection to this. She had never before used a lipstick, but the idea gave her a small thrill of pleasure.

"Put cold cream on first," said Miss Dolly. "Use plenty of lipstick, Maggie... No, this way..."

Maggie regarded herself in the mirror. She looked taller in this grey dress, and her face was different; the rich red lips made her eyes look bluer, and her fair skin, dusted with powder, seemed dazzlingly fair. I love it, she thought. I'm going to buy a lipstick for myself.

"Now, let's go down," said Miss Dolly. "And don't open the door, Maggie. Don't wait on people."

"Who is going to wait on the people, Miss Dolly?"

"Not Miss Dolly!"

"Miss Camford."

"We'll all wait on ourselves, Johnny'll mix the cocktails, and I brought along potato chips and popcorn. It's going to be very informal. Let's go down now, Maggie."

"But what about Mr. Angel?" said Maggie with a guilty start.

"Johnny Cassidy will go and telephone."

"But, Miss—Miss Camford, every minute counts."

"It can't if he's dead," said Miss Dolly. "But I'll send Johnny right away."

The doorbell rang.

"Oh, there they are!" said Miss Dolly, catching Maggie by the wrist. "Please do the best you can..."

She started down the narrow stairway, and Maggie followed her, suddenly sick with fear. Oh, don't let me make a fool of myself! she prayed in her heart.

Miss Mitzi Plummer had already opened the door, and a man and a woman had entered.

"Gabrielle's pretty shaky," said the man. "It was pretty ghastly. We came over in the launch, you know, and when we went down to the landing-stage, there was a body—a man, washed up on our beach."

It's Mr. Angel, Maggie said to herself. It's a judgment.

"BUT how horrible!" said Miss Dolly.

"Yes..." said Gabrielle.

She was a blonde girl, very thin, with hollows under her cheekbones, and no figure. But she made an asset of her gauntness; she had style, distinction, the fluid grace of a cat, in her plain dark-blue linen dress.

"This is my secretary, Maggie MacGowan, Gabrielle. Maggie—Mrs. Getty. And Mr. Getty."

Maggie did not like the looks of Mr. Getty. He was handsome, in a way, but it was a way too male for her taste, too unromantic. He was dark, stalwart, heavy-shouldered, with a bluish jaw and a quick uncheerful smile.

"How do you do?" he said, appraising Maggie with a quick glance.

"Was it suicide, do you think?" said Miss Plummer.

"Could be, I suppose," said Getty. "But I didn't think of that. Well-dressed fellow, prosperous looking. I thought of murder."

"Murder...?" said Miss Plummer. "But why think of that, Hiram?"

"Well," said Getty, "he wasn't dressed for boating. Didn't look like anyone who'd fallen overboard from any kind of craft. Anyhow, people don't fall overboard in this kind of weather. And suicide didn't come into my head. He was too comfortable looking."

"Strange accidents happen," said Miss Plummer.

"You're right," said Getty. "Anyhow I called up Captain Hofer and he's on the job. We'll soon find out."

"He had white hair..." said Gabrielle Getty, unsteadily. "He looked—"

"Take it easy, Gabrielle," said her husband. "Try to forget it. Have a drink."