RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

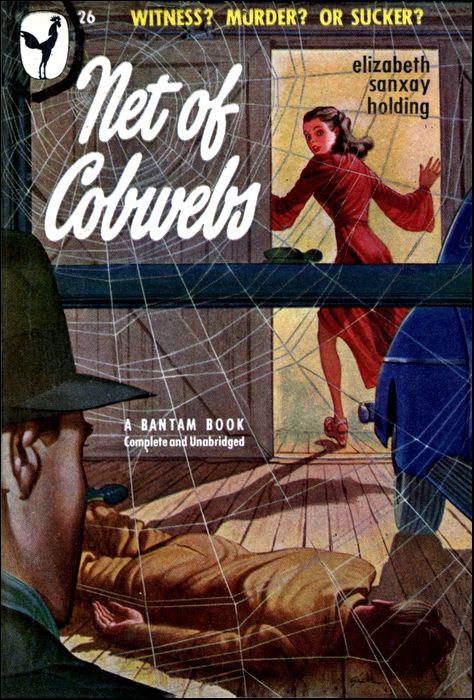

"Net of Cobwebs," Bantam Books, New York, 1946

"Net of Cobwebs" is a psychological suspense story centered on Malcolm Drake, a former merchant seaman who has returned home after a traumatic voyage that left him emotionally shattered. Malcolm now lives in his brother Arthur's orderly suburban household, surrounded by people who seem to want to help him: Helene, Arthur's refined and anxious wife, obsessed with propriety; Virginia, Helene's strong-willed sister, who tries to shape everyone's life to fit her plans; Aunt Evie, outwardly sweet and decicated to "bringing joy."

When Aunt Evie suddenly collapses and dies at a party, rumors begin to swirl that Malcolm may have been involved. The police start asking questions, and Malcolm—already unstable—finds himself trapped in a tightening web of suspicion, manipulation, and psychological pressure.

MALCOLM DRAKE waked early that morning; a little after five. It was a fine September morning and he felt fine, simply fine; he went into his bathroom and took a cold shower, and then there was the thermos bottle of hot coffee on the table. Virginia left it there every night; she was always trying to help him.

He sat down at the table, in nothing but jaunty candy-striped shorts, and poured out a cup of coffee, black and steaming, plenty of sugar in it. I feel fine, he said to himself, and he looked fine; he could see himself in the mirror set in the bathroom door. He was brown and hardy, neatly built; only he did not like his face so much, with dark curly hair growing too low on his forehead, and little, deep-set dark eyes, and two vertical creases in his lean cheeks that made him seem to be smiling, in a sad, doggy way.

He lit a cigarette with the second cup of coffee and leaned back comfortably in the chair. His windows faced the west, so he could not see the sun, but the sky was clear and pale blue. A fine day for a little exercise, that's the idea. I'm coming out of this, all right. Getting better every day.

Coming out of what? What was it he had got into, what dim little hell, like a trap of cobwebs? Never mind. Never mind. He felt fine now. The only thing that bothered him was to see the bed unmade. It would be a long time, hours, before the housemaid came around, and who wanted to sit in a room like this?

He made the bed himself, very carefully; he turned the mattress, made the sheets and the blanket smooth and taut, tucked in the corners of the white spread, laid the pillow exactly straight. He took the two overflowing ash trays and emptied them in the bathroom; he got yesterday's shirt out of the hamper and dusted with it. I like things tidy, he thought. My cabin was always—

Never mind about cabins. He was living on shore now, a new life. The thing was to get started, get going. Get dressed, that's the first step. He put on a clean blue shirt and a dark suit and his well-polished shoes; he lit another cigarette and stood by the window, looking out at the wide green lawn that ended in a belt of trees. He liked the neatness of this landscape, and the different shades of green, the pale-green birches and the dark-green pines. I might go out and take a walk, he said to himself. I think I will.

He finished his cigarette, standing there, and he lit another. Might do a little reading, he told himself, and turned back to the table, where a couple of nice books lay, picked out for him by Virginia. Wonderful girl, he thought, and still standing he opened one of the books.

He could not read. He tried. He read the first paragraph over and over, and his hands began to tremble, his mouth twitched. No... I'll go out, get out in the fresh air, he told himself.

But he could not go out.

The whole thing was coming back, like a towering wave rushing at him. He stood facing it, breathing fast, and out of the wave came a bony wrist and a thin hand. That was Alfred. Jump, you damn fool! he had yelled to Alfred.

Now... No! Look here! he said to himself. This is the bad time, early in the morning. Nobody else awake in the house. In the world.

He went like a blindfolded man, lifting his feet too high, to the closet; he opened the door and fumbled among the clothes hanging there, and in the back, in the pocket of his winter overcoat, he found his little bottle.

It was hard to get the top unscrewed, and it was hard to shake out a capsule into his hand. Bright, vivid blue they were; very fine little pills. If you took four at night, you slept; if you took just one, times like this, the whole thing slowed down, that shaking stopped; you could feel yourself coming together again.

Drake, Dr. Lurie had said, I don't want you to take any more of those capsules. Yes, I know the doctor in Trinidad gave them to you, and I consented to give you a prescription when you first came here. But you've been here six weeks now and it's time you made an effort. I'm not going to renew your prescription, Drake, and you can't get the capsules without it. Personally, I don't care for these sedatives, in a case like yours. Dangerous.

Doctor in Trinidad told me you could take a whole bottle of them and never turn a hair, Malcolm had said, and he had been pretty proud of himself for thinking that up on the spot. It had been a pleasure to see Lurie sort of foam up. A bottle of those capsules would kill you, Drake.

Just what he wanted to know. He had ten bottles now. He had called up the druggist in the village. Send over a couple of bottles of those capsules, will you? he had said. I'll give your boy the new prescription when he comes. Then when the boy had come, Malcolm had said he would send the prescription by mail. Not so good; every time he did it, it made him nervous. But the druggist didn't seem to care, and Malcolm bought everything else he could dream up from the man. And the great thing was to get perhaps fifteen bottles and hide them, and be safe.

He put the bottle back into the overcoat pocket and was going to the bathroom to get a glass of water when there was a knock at the door.

"Just a moment?" he called.

But the door opened, and in came Aunt Evie, trim and dainty in a flowered print dress, her blue-white hair all in little curls about her rose-pink face. Her blue eyes flickered at his clenched hand that held the capsule; her cupid's-bow mouth smiled.

"Malcolm boy," she said winningly, "let's go out and take a little walk in the nice fresh air, shan't we?"

"Th-thank you," he said. "L-later."

He was stuttering, and that always worried him.

"Oh, let's go now!" she said, advancing toward him in a faint cloud of perfume. "Right now!"

She thought she was helping him and saving him, and it was all wrong to feel like this about her. Only if she doesn't get away from me, I'll be sick. I'll heave. I'll go crazy. Get out! Get away from me....

"Malcolm boy," she said, and laid her hand over his clenched one. "You're not—taking anything, are you?"

Make her go. Please make her get out.

"Malcolm boy, Dr. Lurie doesn't want you to take anything now. Not anything."

He jerked his hand away and popped the capsule into his mouth. He could not swallow and he was going to choke. But he did swallow it.

"Oh, Malcom!" she cried.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I'm sorry, but would you mind.... D'you mind going away—just for a few moments?"

"Oh Malcom!" she said in a stricken voice. "You want to get rid of me!"

He did; indeed he did.

She went toward the open door and in the hall she paused and looked back at him with a piteous and forgiving smile. Over her shoulder Malcolm saw the silly gaping face of Ben, the butler/handyman; he closed the door on both of them and looked around his big, comfortable room in desperation.

Don't know what to do. Don't know what to do, he thought. He locked the door and got out the jigsaw puzzle Virginia had given him. He cleared off a table and dumped all the pieces out on it; he drew up a chair and set to work on it with his hands, his broad shoulders hunched. He tried, breathing hard, and when he fitted two pieces together that made half a lamb, he felt better. He got interested in the puzzle, only the sky was difficult; all those clouds.

The doorknob rattled; that was Arthur.

"Come in! Come in!" Malcolm cried and jumped up, knocking the puzzle all over the floor. He unlocked the door and his brother stood there, pale, gloomy, his light hair ruffled on the crown of his head, his tie crooked. Yet somehow he had a look of the greatest elegance, with his long, sharp nose and his tall, lean body.

"Malcolm?" he said. "How's everything?"

"Everything's fine," Malcolm answered, and they went along the hall and down the stairs together. Funny thing, Malcolm thought, but I always feel better with Arthur. He's not calm, not any of those things they say are good for you. But I feel better when he's around.

They went into the dining room. "Ah! Aunt Evie's not down!" Arthur said very low. "Maybe she's sick. Maybe she's laid up."

"She isn't," said Malcolm. "She came into my room this morning."

"To bring you joy."

"Oh, yes. Y'know, I wish the old girl didn't think I needed quite so much saving."

"She thinks everyone's a drunkard and a gambler and a lecher," said Arthur. "It makes her very serene and happy. Hi, Lydia!"

"Yes, sir?" said the little housemaid.

"This it, Lydia? This the new brew?'

"Oh, yes, sir!" she answered, with a dimpled smile. "Mrs. Drake told me specially, sir."

"Try it, will you, Malcolm?"

Malcolm took a sip of his coffee.

"It's a new account," Arthur said. "I've thought up this name for it—Don Carlos Coffee. Not too bad! Only I haven't got an angle. I mean, why should anybody buy it! Don Carlos, the Coffee That Is No Different.... Switch today to Don Carlos—just for the hell of it."

"Good morning, boys!" said Aunt Evie.

She was standing behind Malcolm; as he tried to rise she laid her hand on his shoulder.

"Try to eat, Malcolm boy," she said.

Her sweet perfume enveloped him; appalling things to say came into his head, things that would have made her blue-white curls rise up on her head. "I will," he said. "I will." Get out. Go and sit down. Get away from me.

"Such a lovely, lovely day," she said. "You will get out in this wonderful sunshine, won't you, Malcolm?"

"Yes, I will," he said. "I will," and at last she moved away.

Arthur pulled back her chair for her with the formal and elegant courtesy that was natural to him. He seemed so distrait and preoccupied, yet he never neglected little things like this; he never overlooked anybody.

"And this is the new Don Carlos, Arthur?" she asked.

"How did you know about it?"

"But I heard you talking to Helene, dear. It must be very, very hard to have to praise a thing you really despise in your heart."

"Despise Don Carlos?" said Arthur. "Not I."

"Money makes us do such strange, unlovely things," said Aunt Evie gently.

"Aunt Evie," said Arthur, "this is the best brew you ever set tooth to. Try it."

"I don't notice what I eat or drink, dear boy."

"But you notice aroma," said Arthur. "Just get a load of that aroma, Aunt Evie. You can help me infinitely if you'll tell your many friends about Don Carlos."

"I will, dear. But I did think, from the way you were talking to Helene, that it made you just a little heartsick to have to sing the praises of something, just for money, that you really—"

"You're mistaken!" said Arthur gravely. "My only worry is how to get people to try this king of brews. How to arouse curiosity."

"Curiosity killed the cat," said Aunt Evie with a silvery laugh. "Satisfaction brought it back. How would that do for your slogan, Arthur?"

"It's very punchy," said Arthur. "Only I'm afraid it's not quite realistic enough. I mean, with all the scientific knowledge now available, I'm afraid the consumer won't believe that cats are killed by curiosity."

Aunt Evie laughed again.

"Aren't people funny, with their poor bits of so-called scientific knowledge?" she asked. "Oh, they are," said Arthur.

She began upon her breakfast now, and Malcolm sat stirring and stirring his cup of Don Carlos, and thinking about her. About her awfulness.

When Arthur had married Helene, two years ago, he had accepted the necessity of long and frequent visits from Helene's and Virginia's Aunt Evie. After all, she had brought up the two orphan sisters; they were used to her.

The home life of Aunt Evie was something Malcolm could never imagine. She was well-to-do and lived in an apartment hotel in New York; she talked of the little parties she gave there, in the roof garden. She belonged to a cult which was called, quite simply, Joy. The motto was Joy Now, and when you waked in the morning you stretched up your arms and Accepted Joy. It came, if you did the thing right, flooding all your being, and you were able then to give it out to others. She got it, all right. She was never tired; she was radiant from morning till night, and helpful.

She explained that she could not help people unless she knew things. And she found out everything. She had a sleepless, unwearying curiosity, and great skill in putting two and two together. She believed in candor, too; what she found out she told.

"Good morning, people!" said Virginia.

She was a notable handsome girl, tall and broad-shouldered, with fine dark eyes and a fine color in her olive cheeks, a serious, quiet girl with an air of distinction in her gray flannel suit and blue blouse.

"Where's your naughty sister?" asked Aunt Evie.

"She went to sleep again," said Arthur. "That's not naughty." He pushed back his chair and rose. "I'll have to hurry," he said. "It's my day to taxi the neighbors."

"The good-neighbor policy!" said Aunt Evie, with a merry laugh, and Arthur gave a polite and spasmodic grin and went out of the room.

"Helene is a very, very fortunate young woman," said Aunt Evie. "So many men would resent it, if a young and healthy girl wouldn't come down to breakfast. But in Arthur's eyes, Helene can do no wrong."

There was no response to that.

"Ah, well—" Aunt Evie began, when Lydia came in.

"Mrs. Foxe to speak to you on the telephone, Mrs. Chatsworth," she said, and Aunt Evie rose. She was very fond of telephoning.

"Malcolm," said Virginia, "would you like to come with me this afternoon to see someone about the new bond drive?"

"Oh, certainly!"

"I called up this Mrs. Kingscrown and she seemed very nice. She asked me to come to tea and bring anyone I liked."

"That'll be very fine," said Malcolm.

"Then let's start around four...?"

She was cutting a slice of toast into neat strips; she looked downcast and troubled.

"I hope I don't really hate Aunt Evie," she said.

"You don't hate anybody," said Malcolm.

"But, Malcolm, suppose I hate her subconsciously?" she asked with anxiety.

She worried altogether too much about things like that, about her motives, about her duties, and she had a way of asking Malcolm for advice that made him unhappy. God knew he didn't have any advice to give her or anyone else.

"Well, that kind of hate couldn't do any harm," he said.

"It could do me harm, Malcolm. Hate can warp your whole nature."

"Your nature isn't warped," he said. "You're as good as gold."

"D'you know what she did, Malcolm? I heard her. She called up Dr. Lurie, and she asked him to come in this afternoon and just have a look at you without your suspecting anything. She said she thought you were slipping back. She said you had some sort of queer hostility toward her. She told Dr. Lurie she thought you were dangerous."

He gripped the handle of his cup, to stop the shaking of his hands. The handle broke, and the cup turned over, and a brown stain like mud went running over the clean white cloth. Dangerous, he said to himself in despair. That was what he dreamed in his ghastly nightmares, that was what he dreaded, all the time. Being dangerous.

"BUT, Malcolm!" Virginia said. "You don't mind anything she says."

"No, no," he said. "No... no... no. Excuse me, Virginia. Got to—got to—write some letters."

He had to get into his own room, quick, and shut the door. All right, he thought. I'm crazy. And she knows it, Aunt Evie does. 'Shock,' that damn doctor calls it. People like me don't get 'shocked.' I went through a bad time, yes. But so do plenty of other people, and they get over it. But me...? Two days in a lifeboat, forty-eight hours; what's that? Look at what other people take. Women, children.

But some of them go mad. You hear about that. Raving mad, try to jump overboard. Some people go through with it all right—and some don't.

As he reached the top of the stairs Helene opened her door and came out, tall and exquisite, in a black taffeta housecoat fitted in to her tiny waist.

"Oh, Malcolm!" she said. "I thought it was Arthur."

"Well, no..." he said seriously.

He felt a profound respect for Helene, but he was never at ease with her. She was very courteous to him, and she was kind, but there was a dainty formality about her. She was beautiful and perfect and, to Malcolm, not quite human. She smiled at him, and he smiled at her, and she sought for something to say.

"Ivan Jenette's coming out this afternoon," she said.

"Oh, is he? Fine!" said Malcolm.

"You remember him, Malcolm?"

He didn't know whether to say yes or no. Was this Jenette someone he ought to remember, and possibly did, or could remember if he tried? So he tried.

"It's a lovely day, isn't it?" said Helene.

Her gentle, friendly words did something horrible to him. She had seen, of course, that he didn't know whether or not he remembered this Jenette, and she had tried to make things better for him. But what she really did was to point out to him her own quiet, controlled sureness and his deep confusion.

"Lovely day!" he said with great heartiness. "Lovely!"

He went into his room and locked the door and stayed there until lunchtime. He had plenty to think about.

He went down and had lunch with Helene and Virginia and Aunt Evie. He was the only man; other men went to work. Only he didn't, because he couldn't.

"Shall we start about four o'clock, Malcolm?" Virginia asked.

"Start? Oh, yes!" he said. "Yes. Four o'clock. I'll finish my letters now, if you'll excuse me."

At ten minutes to four he opened the door of his closet. There were three hats on the shelf, two felt ones and a Panama; he stood looking at them, trying to make up his mind, and sweat came out on his forehead.

Now, see here! he told himself. It doesn't matter a damn which hat you wear. Just take one of them—any one—and get going.

He could not. So he closed his eyes and reached up and his hand touched one of the felt hats. He picked up his stick and he put a fresh pack of cigarettes into his pockets and went downstairs. Virginia was standing in the hall below and Aunt Evie was with her.

"Going out, children?" she said. "Don't let Malcolm overdo, Virginia."

She fluttered away, and they went out of the house and down the drive.

"She's been after Helene," said Virginia. "Telling her she ought to learn to cook, so that she could do with one servant. And she had a booklet for me, about teaching physical fitness to girls. Malcolm, maybe she's right."

"Maybe she is," he said.

He tried to think of some way to change the subject and avoid any talk about what was right and what everybody ought to do, but he could think of nothing.

"I've got to do something!" Virginia said. "Only I don't know where I'd be most useful. I wish you'd give me some advice, Malcolm."

"Virginia, I—wouldn't know..."

"Malcolm," she said, anxious, a little hesitant, "maybe if you'd try to help me, it would help you, don't you think?"

Poor kid! So that was why she kept pestering him for 'advice.' To help him. If you can get your mind off your own troubles, Dr. Lurie had said. How do you get your mind off a nightmare?

The air was thin and clear as crystal; the leaves were falling everywhere, and walking through them on the roadside made him think of the days when he and Arthur used to go scuffling through leaves like this on their way to the Military Academy. Fine snobbish little school, fancy uniforms, capes, white gloves.

Alfred had never had anything. He had grown up in a Brooklyn slum; when they signed him on, he was sixteen. I guess I'll study and be an officer, he had said to Malcolm. That was what he had been told. Fine chances for promotion with this line, my lad. Work hard, study hard, take your examinations. Only he hadn't had much time to study. Ten days at sea was all he got.

"You're awfully quiet, Malcolm."

"Yes, I do seem to be," he said apologetically.

"Malcolm, do you think Dr. Lurie is helping you, really?"

"Oh, yes! Sure. You bet!"

"I don't know if I like him much."

Virginia, don't talk any more. Please. You're such a nice kid, such a nice, good, beautiful kid, won't you please shut up and just walk along beside me?

The road was lined with stone walls and wire fences, enclosing big, well-kept estates. People with money, he thought. Like Arthur. I never bothered much about money. When they made me Purser, I was satisfied. And now... Never mind. Someone was burning leaves and that was a fine smell. Halloween, he thought. Mother used to make lanterns out of pumpkins. She was a quiet woman. Happy— but quiet about it.

They were coming to another high wire fence and he was tired of them.

"Quite a long way, isn't it?" he said.

"It's only three miles. Why? Are you tired, Malcolm?"

"Oh, Lord, no! I just thought it was quite a long way."

"I'm afraid you are tired. Oh, Malcolm, I'm worried about you!"

"Well, don't be," he said.

But that wouldn't do; that wasn't good enough. He took her hand and smiled at her, a grin from ear to ear; he kept her hand in his and they went on like that. This is better, he thought. He liked to hold her hand, balled up inside his, warm, soft as velvet, with nice little bones. A good kid, she was, quiet now.

"Here we are, Malcolm. This must be the place."

They turned into a gravel drive that led to a three-storied wooden house with a cupola and a lot of fancy scrollwork.

"Who's this we're going to see?" Malcolm asked.

"I've never met her, Malcolm. Only, at the last wardens' meeting, someone said she'd be a good person to get for the drive. Kingscrown... That's a funny name, isn't it?"

As they came to the steps that led up to the veranda, he loosened his hold on her hand. But her fingers closed around his. Well, nothing you could do about that. If she wanted to go calling hand in hand, very good. He rang the bell, and then she let his hand go. The door was opened by a pale, red-eyed maid.

"Will you please tell Mrs. Kingscrown that Miss Chatsworth is here?" said Virginia.

"She's out," said the maid. "But she was expecting me!"

"Well," said the maid, without much interest, "you could come in and wait."

She led them into a sitting room furnished in a modern style, very low white leather armchairs, a low couch with a cover of brown and blue tweed, a glass-and-chromium table at each end, a bare floor with a rug striped black and white, all airy and sunny and, to Malcolm, very agreeable. Then, as he sat down and looked around, he saw other things. On each step of a zigzag bookcase there were little things; he saw a glass cart drawn by two silver llamas; he saw a plaster replica of the Taj Mahal, a tiny Persian rug, a carved gourd in a silver stand, and other things of that sort, interesting as a toyshop. On a white leather chaise-longue that stood by the open window he saw a purple velvet doll with blond hair and extremely long legs.

"Look!" said Virginia in a low voice.

She was pointing to the iron doorstop. It was made in the form of a short lamppost, and beside it sat a lump of a black dog, winking one eye. It made Malcolm laugh.

"Do you think it's funny?" Virginia asked, surprised.

"Well..." he said apologetically.

Someone was coming up the veranda steps; the door opened and a woman came in, red-haired, tall and limber in dark slacks and a black sweater that outlined a fine full bosom.

"Sorry to be late," she said in a good clear alto voice. "Did Gussie explain?"

"No," said Virginia. "But it doesn't matter a bit, Mrs. Kingscrown. I'm Virginia Chatsworth, and this is Malcolm Drake, my brother-in-law."

"I'm Lily Kingscrown," said the hostess, "I'm sorry Gussie didn't explain, but sometimes she forgets, and sometimes she gets sort of contrary."

"Maids are so terribly hard to get, these days," said Virginia, "I suppose it's only human nature for them to take advantage of it, a little."

"Well, Gussie was just born to be taken advantage of," said Mrs. Kingscrown. "I told her to tell you they might keep me a little late at the asylum. I go there most afternoons, to help out."

"Oh, an orphan asylum?" asked Virginia.

"Lunatics," said Mrs. Kingscrown. "Mental hospital is what they really call it."

She opened a door and spoke to Gussie; then she sat down, crossing her long legs; her red hair curled up like petals from her strong-boned face with a big, beautiful good-humored mouth.

"What do you d-d-do there?" Malcolm asked.

"Well, I help out with the occupational therapy," she said. "Of course, I'm not trained, but still there are a lot of things I can do."

"But isn't it terribly depressing?" Virginia asked.

"Not as much as you'd think," said Mrs. Kingscrown. "For one thing, quite a lot of them get well. And then there are quite a lot of them who don't realize how they are. You can do a lot for them. We make gardens, and weave, and rainy days we do jigsaw puzzles."

"I think jigsaw puzzles are fascinating," said Virginia quickly. Too quickly.

Gussie was coming in now with a very lavish tea, hot buttered muffins, two kinds of sandwiches, a big layer cake.

"My husband was English," said Mrs. Kingscrown. "He was always crazy for his tea, and he got me in the habit. It is cozy, isn't it?"

She looked straight at Malcolm, with her big jolly smile, and he felt instantly and completely reassured. She knows, he thought. She knows all about things like that.

He felt very hungry now, and this was the best food he had ever tasted; he drank three cups of tea and he ate and ate. Virginia and Mrs. Kingscrown were talking about the bond drive; he did not listen to their words, but he liked the sound of their voices; he felt unbelievably happy and relaxed. This Mrs. Kingscrown, he thought. If she works in a place like that, she knows. Lots of people get well, she said.

A portly yellow cat came into the room, with the observant yet aloof air of a policeman on patrol.

"Hello, Skipper!" said Mrs. Kingscrown.

The cat winked at her, and jumped up on the chaise-longue beside the purple velvet doll; he made himself comfortable there, and purred for a while, staring at Malcolm with clear topaz eyes. Then, as if satisfied, he closed his eyes and went to sleep, in a bar of sunshine.

"Malcolm, I'm sorry..."

That was Virginia's voice, very close to his ear. He opened his eyes and looked into her eyes, dark and anxious.

"Malcolm, I'm sorry, but we'll really have to be going."

So he had fallen asleep, at Mrs. Kingscrown's tea party. He rose quickly, dazed and unsteady with sleep, and horribly ashamed of himself. The big room was shadowy; the cat was gone; the scene was chilly and strange.

"I'll drive you people home," said Mrs. Kingscrown.

"Oh, don't bother!" said Virginia.

"It's no bother. My car's right out there, and I've got plenty of gas."

Malcolm was deeply relieved to think that he did not have to part just yet from Mrs. Kingscrown. He could not bear to be parted from her; he hated to leave her house.

"Is—is S-s-skipper gone?" he asked. "That's a nice name."

"He's a seagoing cat," Mrs. Kingscrown explained. "He belonged to my husband, and he was a skipper, you know."

My God! thought Malcolm, overwhelmed.

"What line?" he asked.

"The Bell Line."

"No!"

"Why?" asked Mrs. Kingscrown. "D'you know anybody in that line?"

I did, he thought. That was my line. But not now. I'm not going to talk about that now.

"If you're ready...?" Virginia suggested, and they all went out of the house.

The sun was gone; there was a lemon-colored light in the west and the trees looked black against it; the autumn landscape seemed vast and sad. Malcolm felt cold. Arthur's house looked sad, too; he hated to go into it.

"Come in and have a drink?" he said to Mrs. Kingscrown.

"I'd love it!" she said.

Ben, tall and bony and gangling, in a clean white jacket, opened the door.

"Mrs. Drake is in the library, sir," he said, "and Dr. Lurie—"

"Let's have some Scotch, Ben, and ginger ale. In the d-d-drawing room."

The drawing room was the coldest room he had ever been in in all his life. The lamps had white shades, frosty; the carpet was pale; the sun was not coming in here.

"Malcolm," said Virginia, very low, "don't take a drink. Please, Malcolm."

"One won't hurt me, Virginia. I'm—cold."

"Please. Malcolm! Dr. Lurie told me it was the worst thing in the world for you."

"He could be wrong, Virginia."

She looked at him and then moved away, across the long room; she stood at the window, looking out. I've hurt her, he thought. I didn't mean to do that. He wanted to go after her, but he did not know what to say. He did not know what to say to Mrs. Kingscrown, either. She was sitting on a sofa, and he sat down beside her; he hoped she would talk, and she did.

"Did you read in the papers about the two French sailors in the Brooklyn subway?" she asked.

"No," Malcolm said. "I—don't seem to read the papers."

"Well, it doesn't matter," she said. "There's no law about it, is there?"

Ben came in then with a tray, and Malcolm got up at once to mix the drinks.

"Virginia?" he said. "L-little drink?"

"No, thank you," she said, without warning.

It was growing dark in the room; Mrs. Kingscrown's face looked pale in the dimness.

"After all," she said gravely, "there's nothing like Scotch, is there?"

"Nothing!" Malcolm said. "Nothing!"

The drink was beginning to help; the blood was running warmer in his veins, the numbness in his heart was thawing.

"Malcolm boy!" cried Aunt Evie.

She was coming toward him, in a lavender chiffon dress with floating sleeves and a purple jet butterfly in her blue-white curls.

"Oh...!" she said, peering at Mrs. Kingscrown; then she turned on the lamp and her smile.

"This is Mrs. K-K-Kay—" said Malcolm.

"How do you do, Mrs. Kay," said Aunt Evie. "Are you a neighbor of ours?"

"Yes, I live a couple of miles down the road."

"Have you lived here long, Mrs. Kay?"

"Only since April."

Aunt Evie's curiosity was not subtle; many people resented it. But not Mrs. Kingscrown. She seemed perfectly willing to answer questions.

"Are you a New Yorker, Mrs. Kay?"

"I'm from Brooklyn," said Mrs. Kingscrown.

"Oh, are you? I have friends in Brooklyn, very dear friends. They live on the Heights. Malcolm dear, what are you drinking?"

"Scotch."

"Dear boy, put down that glass, won't you? Alcohol is poison for you." She turned to Mrs. Kingscrown. "Malcolm's been ill, you know," she said. "So very, very ill. Dr. Lurie—"

Shut up! cried Malcolm to himself, and finished his drink quickly, so that she couldn't get it away from him.

"Why don't you try a drink, Aunt Evie?" he said. "You'd be surprised."

That made her angry; her blue eyes glittered.

"Dear boy, I've never touched alcohol. I never feel the need for artificial stimulants. Or drugs."

She was looking straight at him, and he knew what she meant. She always called those capsules 'drugs.' If she says anything to Mrs. Kingscrown about my taking drugs, he thought, I'll have to choke her, that's all.

"You ought to try some of this alcohol," he said. "Just to see what it could do to you."

"Very well!" she cried. "I will! Fix me a drink, Malcolm."

He poured a glass almost full of ginger ale and added a dash of whisky; he was handing it to her when Helene came into the room, followed by two men.

"Here I am, tippling!" cried Aunt Evie.

That fell flat, because Helene had caught sight of Mrs. Kingscrown and came toward her with the look of delight she had for guests. Malcolm said nothing, and Aunt Evie took charge.

"Helene, dear," she said, "this is a Mrs. Kay. From Brooklyn."

"I'm so glad," said Helene. "This is Dr. Lurie."

"Mrs. Kingscrown and I are old friends," said Dr. Lurie, stepping forward, a slender, straight man, with a trick of carrying his head thrown back and his square chin out; he wore his gray hair in a sort of pompadour over his broad brow and he had a look of proud suffering.

"And this is Ivan Jenette," Helene said.

This Jenette was a stocky, broad-shouldered young fellow, black-haired and sallow, with sad, bilious dark eyes. He gave Mrs. Kingscrown a foreign-style bow, heels together; then he looked sidelong at Malcolm, with considerable distaste.

"Ivan, you and Malcolm know about each other," said Helene.

"Oh, yes," said Malcolm politely, but with no truth, and Jenette said nothing at all.

"Everybody's drinking whisky in here," said Helene, "while we were so nicely having tea. Will you have a drink, Dr. Lurie and Ivan?"

"I'm taking a drink, Dr. Lurie!" cried Aunt Evie. "My very firstest one—and who knows what will happen? I do hope I shan't talk too much and say the wrong things."

Malcolm glanced quickly at her, and their eyes met. God! he thought. That's just what she means to do.

The amount of whisky he had given her couldn't, he thought, have any genuine effect upon her or anyone else. But if she chose to put on an act, to start babbling, saying the 'wrong things'... About me, he thought. About my pills and all that. I wish she'd choke.

"Good gracious!" she said, coughing and gasping. "It's like liquid fire!"

Ivan Jenette took her glass from her and set it down on a table while she went on coughing.

"But I will finish it!" she said. "Every drop! Ivan, where is my dreadful drink?"

He handed her the glass and she sipped and choked again. "Aunt Evie," said Virginia, coming across the room from the window, "don't take any more."

I agree with Miss Virginia," said Dr. Lurie.

"I'm going to be naughty!" said Aunt Evie. "Malcolm poured it out for me and he wouldn't let me have too much. I'm going to finish every drop of it!"

"I'm afraid I'll have to be going now, Mrs. Chatsworth," said Mrs. Kingscrown.

"Oh, don't hurry away!" said Aunt Evie. "I wanted a little chat with you about Brooklyn."

"Come and see me some time, why don't you?" said Mrs. Kingscrown, with perfect good humor. "Good-by, Miss Chatsworth."

"Good-by," said Virginia briefly.

"I'll go out to your car with you," said Malcolm.

For he couldn't bear to see her going away.

They went out on the terrace together and it was full dusk now.

"It's nice," she said.

They stood side by side, looking out over Arthur's peaceful domain. Her car stood there, and she was surely going to get into it and go away. There was so little time.

"Thing is..." he said. "I made—an error of judgment."

I called out—jump, you damn fool! And Alfred jumped. Like that joke about the volunteer fireman. He called out to the fellow in the burning house—jump into the net, and the fellow jumped. And cheese it, I had to laugh. There wasn't no net.

"I gave bad advice," he said.

His mouth twitched, the bridge of his nose twitched. God, if I could tell it! If I could say it!

"I gave bad advice," he said. "He was only a kid. Only sixteen. He was frightened sick, right from the start. I told him—nothing to worry about. I told him everything would be all right."

I killed him. The others on the deck—the ones who didn't jump—they were all taken off, safe and sound. Only Alfred... I told him to jump and he did. He landed flat against the thwart of the lifeboat and it caught him on the chin and broke his neck.

"The fellows on deck," he said, "they looked like gnomes. They were on deck in their life belts and they looked—very small. They looked as if they didn't have any necks. He was only sixteen."

Oh God, let me tell it, let me say it, this once....

"It was cold," he said. "It was a cold day."

She had not spoken at all; he could scarcely see her now in the gathering dusk. But he knew she was listening. "I g-gave him bad advice," he said.

"And he died?" she asked.

Her voice sounded gentle and far away. But she was standing beside him, near him. We couldn't keep the kid in the lifeboat. He was dead. We had to put him overboard. If I could tell you—.

"Mr. Drake!" said Lydia's voice, high and urgent. "Mr. Drake, are you there, sir? Mr. Drake!"

"Yes, I'm here," he said.

"Oh, Mr. Drake, sir!... Mrs. Chatsworth is dead!"

"What?" he asked, puzzled.

"She fell right down dead on the floor, Mr. Drake."

"EXCUSE me, just for a moment, please," he said politely to Mrs. Kingscrown, and followed Lydia into the house.

The drawing room was empty; he looked into the library and saw nobody there.

"Where are they all?" he asked.

"The doctor and Mr. Jenette, they carried poor Mrs. Chatsworth upstairs, and Mrs. Drake and Miss Virginia—they went up, too, sir," Lydia answered eagerly.

"I'd better go up, don't you think?"

"I don't know, sir," said Lydia.

"No. No, of course you don't," he said apologetically. "What shall we do, sir?"

"Well, who?"

"Ben and me and Mrs. Jordan, sir. What did we ought to do, sir? Go right on about—" She lowered her voice. "About dinner, and all, sir?"

He looked at her blankly.

"L-l-later," Malcolm said. "I'll l-let you know l-later."

So he was in charge. He was to tell people what to do. He stood in the hall, and his knees felt weak. I've got to take charge. Give orders. What'll I do? You tell me. Where shall I go? Where do we go from here? Upstairs. Only, when he looked at the stairs, they were so extremely steep and long he could not start climbing them. Lydia was looking at him, waiting.

"You'd better—better—better tell me—exactly what happened," he said.

"I was just going into the room, sir, with some fresh canapes Ben made, and Mrs. Chatsworth, she sort of sunk down right on the floor, and then Dr. Lurie he knelt down beside her, and you could see by looking at him that it was terrible serious."

She was crying a little, but she could not help relishing the drama of this.

"Right while I was standing there," she said, "she must of died."

"Well, why?"

"Why, sir? Well, the doctor didn't say. But don't you guess it was a kind of stroke, like?"

"Must have been. I'll get along upstairs now."

He could not start climbing those stairs. Arthur must be on his way home now, he thought. Arthur'll know what to do when he comes. Only, right now... If Aunt Evie falls down dead, you have to do something. Be helpful. Go on! Begin!

Dr. Lurie was coming down the stairs and Lydia went away.

"This is a shocking affair!" said the doctor sternly. "Yes, it is," said Malcolm. "It is."

"And reprehensible," said the doctor.

Reprehensible. Reprehensible, Malcolm said to himself. Sounds like an Amos 'n' Andy word.

"Mrs. Chatsworth had had a heart condition for some time," the doctor went on, with the same sternness. "It was not unduly serious, but at her age—she was well over seventy—"

"Over seventy, was she? Didn't know that."

"No doubt someone thought it highly humorous to give that elderly woman with heart trouble an extremely strong drink," said the doctor.

"Oh, no," said Malcolm. "Nobody. What she got wouldn't have hurt a baby."

"Mr. Drake, there's no use telling that to me. I'm a physician. This attack of Mrs. Chatsworth's—this fatal attack —was induced by an excessive dose of alcohol."

"M-mistaken," said Malcolm.

"What d'you mean by that? Are you implying that my diagnosis is incorrect?"

"Only mean that the drink I gave her wasn't excessive. Tiny, it was."

"And what's your idea of a 'tiny' drink, Mr. Drake?"

"It wasn't more than a couple of teaspoonfuls."

"I can assure you Mrs. Chatsworth had a good deal more than that."

"Well," Malcolm said, "I suppose she could have poured herself out another drink, not knowing."

"I doubt it," said Lurie. "I was observing her fairly closely, and I should almost certainly have noticed it if she'd poured any more liquor into her glass. I should have protested, very strongly, against any such thing. As it was, I had accepted your assurance that the drink you gave her was extremely small."

"Yes, it was," said Malcolm.

"I'm signing a certificate," said the doctor. "Mrs. Chatsworth was my patient, and I was present when she died, so I can properly do so. But if it wasn't for the high regard I have for your brother and his wife, I should put down alcohol as the contributing cause."

"Look here," said Malcolm. "I didn't give her a big drink because I thought it would be funny. I know what I gave her."

"Mr. Drake," said the doctor, "I understand that you've been taking some medicine—some drug—on your own responsibility. You've chosen to disregard the advice I—"

"Oh, go lay an egg!" said Malcolm.

"What!" said Dr. Lurie.

Malcolm felt very happy about saying that and about the outraged look on the doctor's noble face. It was a long time since he had felt even an impulse to hit back at anyone and it did him good.

"I said—" he began, very willing to repeat. But a key was turning in the lock; the front door opened, and Arthur came in.

"Hello," he said amiably. "How's everything?"

"Drake," said Dr. Lurie, and laid his hand on Arthur's shoulder. "I'm sorry, Drake, very sorry. Mrs. Chatsworth—" Malcolm did not want to hear any more of that; he wandered off into the library and there he found Jenette, slouched in a big chair, smoking a pipe. He looked up at Malcolm with his cloudy, dark eyes.

This is a hell of a thing to happen, isn't it?" he said. Yes, it is," said Malcolm.

"It gets on my nerves," said Jenette. "A death in the house—"

She's dead, Malcolm thought in a sort of astonishment. She's lying upstairs, dead. Poor old girl was hopping around, so lively, and now it's finished for her. It's damn pathetic. I mean, it's all right for some people to die. They can take it. But Aunt Evie...

His thoughts were growing confused and miserable. Thing is, he thought, she was so little. Hopping around...

Mrs. Kingscrown! he thought suddenly. She's gone home, I suppose. She wouldn't still be out there, would she?

"Excuse me," he said to Jenette, and went along the hall and out on the terrace. It was dark now, and only Dr. Lurie's car was standing there; she was gone, and he missed her. I'd like to say au revoir, he thought. Don't like to leave it this way. I just walked off and left her out here. I'd like her to know...

He went back into the library, where there was a telephone, and he was glad to find Jenette gone. He looked in the telephone book. Kingscrown, Mrs. Lily. There it was. He dialed the number, but nothing happened. Virginia came into the room.

"I don't get any answer," he said, frowning.

"Who are you trying to get, Malcolm?"

"Mrs. Kingscrown," he said. "I want to speak to her but I don't get any answer."

"Probably she's not at home."

"But the house ought to answer. Ought to be a servant-somebody around."

"You can try later," said Virginia. "We're going to have dinner now, Malcolm."

"Dinner?" he repeated.

"Things have to go on, Malcolm."

"I'll try the number again," he said, but still there was no answer. "This worries me," he said. "The house ought to answer."

"Well, you can try again after dinner."

"I think I'll go over there and see if everything's all right."

"But dinner's ready, Malcolm!"

"I don't seem to feel like eating, Virginia. Worries me, y'know, not to get any answer."

"Malcolm!" she said. "That's really rather silly. That Mrs. Kingscrown certainly knows how to look after herself."

"I can't help it," he said. "You know how you get these ideas."

"No, I don't," said Virginia. "Malcolm, please come and eat your dinner. Please don't be so obstinate." He was sorry about being obstinate.

"I mean, there ought to be somebody in her house. I mean—the maid—somebody."

"I wish I'd never taken you there!" Virginia cried. "But I didn't know she'd be like this."

"Well, like what?" he asked anxiously.

"So common—"

"She's not common, Virginia."

"She is! A big, red-headed wench. What's more, she's at least thirty-five."

"Well, why not?" he asked. "I mean, what's that got to do with anything, Virginia?"

"Malcolm," she said, "I'm pretty upset and unhappy about Aunt Evie. After all, she brought us up. Malcolm, I ask you as a favor to me to come in to dinner now."

"V-V-Virginia," he said, desperately anxious to explain to her. In his mind was a picture of Mrs. Kingscrown's house, dark and solitary, and it worried him; it more than worried him. It frightened him. He was in a hurry to get there. "I—I'll come right back, Virginia, if everything's O.K. I'll just t-take a look."

"All right," she said, turning away. "You've let me down, just when I need you."

Her voice was unsteady; he thought she was crying. Going away from her, hurt, disappointed, let down. I let everybody down, he thought. That's what's wrong with me.

But he had to go and see about Mrs. Kingscrown. He did not bother with a coat; he simply walked out of the house and down the drive. It had been a long time since he had gone walking in the dark alone, and it was strange. It was strange to hear the insects chirping in the grass, and the rustle of the trees; it was strangest of all to look up at the sky, it was so unexpectedly wild, pallid, with thick black clouds streaming across it. He didn't like it; it reminded him of something.

The long-haul trucks were moving along the highway with dim lights. All this going on, he thought, war or no war. Things have to go on, Virginia said. All right, but I don't. I stopped.... Never mind. I'll get in the Army when I've got over—this—this.... The Army. Not the Navy. You don't have to go to sea again. Don't have to go near the ocean again. Don't have to think about it.

He walked fast; he was in a hurry. Damn queer that the house didn't answer, he said to himself. I last saw her out on the terrace, and how do I know if she ever got home? Plenty of accidents.... A truck went by, and his heart began to beat too fast. If her house is dark... he thought.

When he turned into the driveway, he saw a lighted window at the side of the house. He was afraid the light would go out before he got there, and he turned off the drive and ran across the grass.

The shades were up and he could see her. She was sitting alone at a table spread with a lace cloth, with four candles in silver holders; she wore a green dress and her red hair glittered. She looked lonely, but she looked all right.

He felt tired, but he felt pleased; he felt as if he had done something for her in return for some immeasurably greater thing that she had done for him. Anyhow, she's all right, he thought. All by herself in that house. That nice house.

Now that he was going back, he slowed down, he took it easy. And the nearer he got to that other house, the less did he want to go to into it. I'll be late to dinner, he thought, and that's not quite the thing, in the circumstances. Better get a bite on the way.

The thought made him sweat with anxiety, even fear. I don't know any place to go, he said to himself. Don't like to walk into a place you don't know anything about. It might look queer.

My God! he thought. I used to do it. Went in anywhere, any port, even where I couldn't speak the language. I mean, if I could do that now. Just once?

He walked on to the village, and near the railroad station he saw a restaurant, white-tiled glaringly bright; he saw two waitresses in bright green uniforms moving around. He stood outside, and he did not see how he could do this. I might stumble, trip, fall down, he thought. It's been a long time....

A man went by him, in through the revolving door, and Malcolm started after him, fast. He got in, all right; it was done; he was in a restaurant alone. He sat down at a table and picked up the menu. It was a very faint purple and very blurred, and he could not read it. Something wrong with my eyes, he thought. It couldn't be that bad. A waitress was standing beside him.

"Wh-what's good tonight?" he asked.

"That depends," said she.

"On—on—on what?"

"Quit your kidding," said she, with mechanical coquetry.

"Veal!" he said suddenly.

"Tea or coffee?"

"Coffee and p-p-pie."

"Prune, custard—"

"Apple!"

He felt proud of himself; he felt strong and masterful, capable of quick and vigorous decisions. He enjoyed his dinner; he left a quarter for the waitress, and there was absolutely no trouble getting through the revolving door. Maybe it's over, he thought.

Maybe from now on he could go freely about in the world, talking to people. That was the supreme happiness. And maybe that was coming back now.

There were lights upstairs and down in Arthur's house and that bothered him. He felt so fine that he did not want to think about things, he did not want to talk to anybody. He went to the side door, and it was not locked; he went in quietly.

But Helene came out of the drawing room. "Malcolm," she said in a low voice, "could I speak to you just a moment?"

"Certainly!" he said. "Let's go up to your room."

He knew something bad was coming, and he rebelled against it. Only not against nice little Helene. He went up the stairs ahead of her and turned on the lamp in his room; he stood waiting, and as she entered the room she smiled and he bowed a little. She sat down in a chair by the window and he stood facing her.

"I thought I'd better tell you," she said. "It's not really serious, but I thought I'd better tell you."

"Oh, certainly!"

He saw her hands moving restlessly. She's nervous, he thought. This is something bad.

"I'm going to send Ben away," she said. "I don't like him. I don't think he's reliable."

I'm not understanding this, Malcolm thought. I don't know what she's talking about.

"He came to me and told me. I told him not to mention it to anyone else, and he promised he wouldn't."

"Tell? Tell?"

Her pretty little smile looked contorted. "He told me he'd seen you pour a drink out for Aunt Evie—a very big drink. Almost a whole glassful."

"I did not! I did not!"

"Malcolm," she said, anxiously and earnestly, "please don't mind. Whatever happened was nothing but a mistake. There was a bottle of ginger ale open there; it looks so much like whisky. And you'd had a drink yourself—"

"One! One jigger. One!"

"I know, Malcolm. But you hadn't had anything for a long time, and—"

"I did not!" he said. "I did not!"

"Anyhow, Malcolm, you didn't know Aunt Evie wasn't supposed to drink anything at all."

"I didn't do it," he said. "I did not."

"Well, Ben could easily have been mistaken," she said. But he could tell from her face and from her voice that she did not believe that. "Anyhow, Malcolm, it doesn't matter. Don't let it worry you, Malcolm; please don't. I only told you so that in case there was any silly gossip...."

"Arthur...?" he said. "What does Arthur say?"

"I haven't told him," she said slowly. "I'd rather he didn't know, Malcolm. He's rather worried about his business just now, and I'd rather he didn't have anything more." She looked up at him, a steady and almost stern look. "You know what he's like. So high-strung, and so terribly loyal. I'll get rid of Ben. It'll be easy enough for him to get another job, and probably the whole thing will blow over. But Arthur shouldn't be worried about it, Malcolm."

Now she was not vague and sweet, but very definite. She had welcomed him here with the kindness of a sister; she made him feel completely at home. But now she let him see beneath that pleasant surface.

"There's nothing Arthur wouldn't do for you," she said.

Look now at what he has done for you. Taken you in here, to stay week after week, with no plans, no talk of any future. Look at your fine big room. Everything done for you, everything given to you. By Arthur. Because he's so terribly loyal. And now you've gone and killed Aunt Evie. That's what she means, he thought.

"Don't let it worry you, Malcolm. No matter what happened, it was simply a mistake."

Another mistake. Another error of judgment. Dangerous, Aunt Evie had called him. You're damned well tooting I'm dangerous.

Helene went on talking.

"I'll get rid of Ben at once, and we'll just forget the whole thing."

He could not talk, because he had to keep his teeth clenched so that his jaw should not tremble. He nodded his head, in a sage and thoughtful way.

"Only, I did think I ought to tell you, Malcolm."

"Um-mm," he said, nodding his head again.

She rose. "Good night, Malcolm," she said, smiling and holding out her hand.

He took her hand in a quick grasp. "Night!" he said.

As soon as she had gone he locked the door and got out the bottle of capsules in a hurry. Two at bedtime. Repeat in half an hour if necessary. Sez who? The hell with you!

IT was half-past five when he waked, but maybe it had been early when he went to bed. He felt completely rested and ready to think. He lay stretched out flat on his back, trying to remember how many of those capsules he had taken last night. More than four?

I think I remember taking four at once, he said to himself. I was standing in the bathroom by the washbasin. I think I remember that. Then I got into bed, and I left the bottle on the table here, and a glass of water. Well, the water's gone. Did I take any more of them?

He was deeply interested in this, and a little anxious. Thing is, if you took too many, would it do anything to you? Make you—queer, any way?

He shook all the capsules out of the bottle and counted them. The bottle held fifty and there were twenty-eight left. But I don't know how many there were to start with last night. I've got to get this straight. This was important.

No. He knew what he had to think about and he started on it. It was clear now, clear as crystal.

Yesterday morning, he thought, Aunt Evie came in here. Into this room. She stood there, where I'm looking. She said, you want to get rid of me. And I said, yes. Not out loud, but I said it.

She told Lurie I was hostile to her. I didn't mean to be. But Virginia talked about hating people subconsciously. Could be that way, couldn't it? Aunt Evie told Lurie I was 'dangerous.'

All right. I don't know. But I'm not taking any more chances. I'm going.

He took a cold shower and dressed with his usual extreme neatness. Then he got his checkbook and figured his balance. Very little left, after those payments to the hospital and the doctors and all that. Only some four hundred dollars. He had gone to sea at seventeen, straight from boarding school, and he was now twenty-eight. Four hundred dollars to show for eleven years of work. Why didn't I try to save?

Because I'm a fool. Right and good. Now I'll get a job. Lots of things I can do. Keep books—accounts. I can type. I can speak Spanish, and a little Portuguese. Strong, too. Good muscular tone, one of those doctors said. Strong and willing. Only...

He went and stood before the mirror, and his face, he thought, with the deep-set little eyes and the long vertical creases in the lean cheeks, had a look of monkeylike anguish. Dumb animal pain. Not human.

"Shut up!" he cried aloud, and then he was afraid. He was afraid someone might have heard him and would come to see what was wrong.

He waited, very still, but nobody came. It was early, not six yet. But there was no time to lose. He started to pack a suitcase, and he did it beautifully, everything folded just so. Don't want to forget anything. And now, how about a note? A note to Arthur?

No, he said. I can't write a note. I'll call him up in his office later. Now...! He put on his light overcoat and a felt hat and unlocked the door. The sweat broke out on his forehead. His hands were damp and cold. This was the last time. Suppose somebody met him now? Sneaking out, with a bag? Lydia, maybe, or the cook or Ben?

Ben had been standing in the hall, and he saw me fix that drink. Ben's an oaf, a clumsy lubber. But he wouldn't make that up, would he? He's got nothing against me. No reason.... If I met Ben now? Or Helene?

Helene would be glad to see me going. On account of Arthur. Doesn't want Arthur all upset by his brother getting in trouble. How much trouble could it be?

It was dark in the hall, and he went carefully, cautiously down the stairs; he heard his own breathing, loud and fast. Like an animal panting. He took the chain off the front door, and his fingers fumbled and it rattled. But he got the door open, he got out into the incredibly sweet fresh morning air. He went along the drive, walking as quickly as he could, and now he had got away.

Now he was out in the world, alone. It was a very bad feeling. No roof over his head, no walls around him, no corner to back into. The long-haul trucks were rolling along, into the city; they moved slowly and shakily, he thought, as if they were weary. They made him nervous; he thought they would tip over. The suitcase was heavy and he had to go so fast.

"Want a lift, mister?" someone called.

It was the driver of a car labeled Merry's Paint and Varnishes. Merry is a nice name, he thought.

"Hop in!" said the driver, and Malcolm climbed up beside him. "Going to New York?"

"No, no," Malcolm answered. "Just down the road a little."

"You're around early," said the driver.

He was a big burly fellow with a blue stubble on his jowls; he was a tough guy. But he seemed happy. "Selling something?" he said. "Me? No," Malcolm said.

"I thought when I seen that bag maybe you were selling something."

I must seem pretty damn queer, Malcolm thought. Walking along the road this hour of the morning, with a suitcase. All right, I am pretty damn queer.

But he was extremely anxious to talk to this tough guy, to explain himself, to be friendly.

"Thing is," he said, "I've been at s-s-sea."

"You can have it," said the driver. "You can have it. Only thing I got against this war is you got to take a boat ride to get to it. I'll be going next week."

"Oh, you will?"

"Yep," said the driver. "And that's O.K. by me. What I mean is I haven't got no wife or kids or anything. As for the girls, well, I guess there's girls everywhere you go, hey? How's about it, sailor?"

I can't talk any more, Malcolm thought. Not like a man. Sailor, he called me. I'm not a sailor any more. He made himself laugh.

"Sure!" he said with loud heartiness. "You bet!"

The man laughed too, and it was better.

"Well, there it is," he said presently. "Well, better be on the outside, lookin' in, hey?"

"What? What is it?"

"There," said the driver. "Up on the hill. The loony bin."

"The l-l-loony bin," Malcolm said.

"That's right," said the driver. "Say, y'know they say they got a lot of guys—women, too—they get put in there that aren't any more crazy than you or me. What I mean is, to get their money, d'you see. They get them shut up there and then they can't make no will."

The subject interested him; he went on, and Malcolm looked back at the big red brick building on the hill.

"Oh!" he said suddenly. "Let me off here, will you? Thanks for the lift."

"Nothing to it," said the driver benevolently.

Mrs. Kingscrown's house looked lovely this morning. Malcolm remembered the little village his grandfather had used to set up around the Christmas tree when they were kids—a fence, a lot of arsenic green grass, sheep with a shepherd, cows, barns, white square house, like this one. She shouldn't live so near the loony bin, he thought.

He crossed the grass to look in at the windows, and the big room was empty. That stopped him. Now he didn't know what to do. It's too early to ring the bell, he thought. I thought she'd be there. I can't ring the doorbell.

Then he heard some little kitchen sounds, little clinkings of metal and china, and he went around to the back of the house. Mrs. Kingscrown was in the kitchen, with the back door wide open; she was wearing blue pajamas, her red hair curling up like petals from her clear, strong-boned face.

She turned her head at the sound of his steps on the back porch.

"Hello!" she said, unsmiling. "Come in; I'm just getting breakfast. Eat with me?"

He felt prodigiously strange, in his hat and overcoat, bag in hand; he set down the bag and took off his hat. She paid little attention to him; she was frying bacon, making toast and coffee, but he was satisfied that she was glad to see him. She just does one thing at a time, that's all, he thought.

She began carrying things into the other room, and he wanted to offer to help her, only he felt strange and clumsy in his overcoat.

"I like a big breakfast," she said. "It's my favorite meal."

He stood in the middle of the kitchen watching her.

"All ready?" she said. "Don't you want to take off your overcoat?"

"Thank you," he said, and laid it over the back of a chair.

She had spread a blue linen cloth on a round coffee table drawn up before the couch, and set it with gray pottery; everything cool and quiet. They sat down side by side, and she poured out two cups of coffee.

"Are you going away?" she asked.

"Yes," he said. "I'm going to get a job."

"Where?"

It bothered him for her to ask that. Because his idea was to take his bat; and go on, until he got somewhere that seemed right, or something definite came into his head. It would. It would. Only not yet.

"I'll get a job," he said, polite but evasive. "Work.... That's the answer, I guess."

"Sometimes," she said. "But sometimes it's not such a good idea to go off all by yourself."

"Yes," he said.

He would have given anything he had to tell her what had happened. What he had done, or maybe not done. But Helene didn't want him to tell anyone.

"I suppose these things—wear off," he said. "Shock, they call it. I don't know—I can't see why it happened to me."

She was looking at him with her bold blue eyes. She wanted to hear what he said.

"Let's eat now," she said.

Two fried eggs, crisp bacon, toast, coffee, orange juice; all so very good.

"The thing is..." he said. "The worst thing was those fellows in the U-boat. I mean, they were standing on deck, and one of them chucked a pack of cigarettes into our boat. I mean—d'you see...? There was that boy Alfred, with his neck broken, and the ship going down—standing on her nose—and they did that. I mean, it wasn't a battle—a fight. It was—"

He was making a frightful effort.

"It was—assassination," he said. "No fighting. And then they chucked cigarettes to us. I mean—if they're devils, for God's sake, let them be devils and not—like that." He put his finger inside his collar.

"You know," he said. "I could see them. See their faces. Well... One of them looked like Alfred. Same age, I should say. There they were—looking at me—and us looking at them. I mean..."

They should not have looked with human eyes, with curiosity.

"—don't seem to get over it," he said. "I don't know why. Other people do."

"You will," she said.

"Thing is, you don't know what to do. How to fight it."

"I don't think there's much fighting you can do," she said. "Just take it easy and try to look at things as straight as you can. You just get over things. I had pneumonia once—about the only time I've ever been really sick—and I used to think a lot about that. About how I just got better, day by day, without doing a darn thing, not even trying."

This idea puzzled him and fascinated him.

"But the thing is," he said, "you don't always get over things."

"Just mostly," she said. "I guess that's good enough." Without trying too much? Without such a weight of guilt because you didn't fight more?

"I telephoned you last night," he said.

"I heard the phone ring," she said. "But Gussie was sick and I was busy with her and I didn't answer it."

"Is Gussie better now?"

"Oh, yes! Have some more coffee?"

"Thanks," he said, and she poured it out for him.

This is peaceful, he thought. This is what I want. A good breakfast in this nice little house. Not necessary to be fighting all the time. Take it easy. Take it easy.

Lily Kingscrown rose and went into the other room and came back with a little box, which she set on the table before him. It had a snow scene painted on the lid in bright, clear colors.

"Cigarettes," she said. "Help yourself."

As he raised the lid, the box began to play For He's a Jolly Good Fellow in a gay, confused little tinkle. It made him laugh, and she laughed too, standing before him, tall and limber and easy in her blue pajamas.

"It's cute, isn't it?" she said.

"Darn cute," he said. "Mrs. Kingscrown—"

"Make it Lily," she said.

"Thank you," he said, pleased beyond measure. "My name's Malcolm."

"I know."

He felt so fine and so happy; only, he wanted her to understand how things were.

"I just stopped by..." he said, and then could not get on with the explaining.

"I'm glad you did," she said.

"But I mean—maybe you think it's—it's queer..."

"To come and see me?" said Lily Kingscrown. "Well, no, I don't." Her bold blue eyes rested on his face. "I've had other people that liked to come and see me," she said serenely.

"I can believe that," said Malcolm. "You wouldn't kid me?"

"Me?" said Malcolm.

How he loved this! This was the way he knew how to talk. They sat facing each other, both smoking; he raised the lid of the little box again and again it began to play For He's a Jolly Good Fellow, and again they both laughed, looking into each other's eyes.

A car was stopping before the house, and he sprang to his feet in wild alarm.

"It's probably Dr. Lurie," said Lily. "He said he'd stop in to see Gussie this morning."

It seemed to Malcolm an unimaginable disaster for Lurie to come now, at this moment. It seemed to him that he had been on the verge of saying something of vital importance.

Lily went to open the door. And it was not Dr. Lurie; it was Virginia; much worse.

"Oh, I'm sorry," she said, "but I was looking for Malcolm..."

"Come in!" said Lily.

Virginia was wearing a black skirt and a white blouse with long sleeves; her black hair was pushed back from her forehead and she looked tired and worried and very handsome. I just walked out on her, without a word, Malcolm thought. Nothing I can say to her.

But Lily could say something. Lily could save him. Virginia's a wonderful girl, but I can't go back with her. It was for Lily to save him.

"Come in and have a cup of coffee," Lily said.

"Thank you, but—things are rather upset, just now. Aunt Evie's lawyer is coming and—there are so many arrangements to make. We really need Malcolm—"

And Lily said nothing. She did not try to save him; she did not explain to Virginia...

"Will you come now, Malcolm?" asked Virginia.

"All right," he said, and came toward her. He stopped in front of Lily. "Thank you," he said.

"You're welcome," she said seriously.

He went out of the house and got into the car beside Virginia. She's done a lot for me, he told himself. She's been very kind and loyal. But she shouldn't have done this.

He sat still, looking steadfastly ahead of him. He was struggling not to feel—the way he did feel about Virginia. I owe her a lot, he thought. But by God, she doesn't own me. She shouldn't have come after me—like this.

"Malcolm," she said, "could you possibly lend me five hundred dollars?"

Startled, he turned his head to look at her. But she kept her eyes on the road.

"Afraid I haven't got quite that much," he said. "But if four hundred will do...?"

"Well, I..." she began, and stopped. "Thank you, Malcolm," she said. "Can I have it as soon as we get back to the house?"

"Certainly!" he said.

Then, when it was too late, when he had committed himself, he saw what he had done. He was giving away his chance to be free. He saw now how desperately he wanted —and needed—to be free. They turned in at the drive, and there was the house, and it was like a prison. He was going back to all that, going back to Aunt Evie.

HELENE was sitting at the breakfast table, alone, in a black sweater and skirt; she looked elegant and pale and tired. And she looked surprised to see Virginia and Malcolm come in.

"Oh, you've been out early, haven't you?" she said, with her charming and meaningless smile. "I'll tell Lydia..." Malcolm sat down at the table. There was death in the house, and it would not be correct to say that he had already had breakfast. That he had tried to run away.

"Arthur's making arrangements to have the funeral tomorrow," Helene went on. "Virginia, is there anybody else we ought to notify?"

It was a curious thing, which Malcolm had noticed before, that in spite of her dignity and poise, Helene couldn't run things, couldn't manage things. She turned to Arthur, and very often to Virginia.

"Well, Cousin Julia—" Virginia said, and Helene wrote down that name, in the little book she had near her.

Lydia brought in another breakfast for Malcolm, and while he drank his coffee, he watched the two sisters. Helene was twenty-two and Virginia was twenty-four; they were lovely girls, fine girls.

But they bore me, he thought.

He was astounded at such a thought; he was ashamed of himself. The trouble is, he told himself, I've never lived on shore since I was seventeen. Not used to a normal, quiet life like this. All right. Maybe I'd better get used to it. Because what else...?

"Mr. Pond will be here for lunch," Helene said. "You won't mind sharing your bathroom with him, will you, Malcolm?"

"Oh, no! No. Not at all. If you'll excuse me—some letters to write."

I always say that, he thought. And it's crazy. Everybody knows damn well I haven't got all these letters to write. I never write any letters. I don't know what to do, that's the truth.

As he went up the stairs, he wondered about Aunt Evie. Still here? he thought, looking at the closed door of her room. You couldn't very well ask anybody about that. He went into his own room and closed the door and looked about him in despair. Arthur doesn't need me, he thought. Nobody does. Nothing I can do. She shouldn't have brought me back.

A knock at the door, and there she was.

"Malcolm, I'm terribly sorry to bother you, but if you could give me a check..."

"Certainly!" he said, and sat down at the table to write it. Signing away everything he had. All right, I owe it to her, he thought.

"There's a bill I—want to settle," she said.

No, he thought. You wouldn't have any bill for five hundred dollars. Couldn't have. You just want to get my money away from me. For my own good. All right. Here it is.

"Here you are!" he said, rising.

"Thanks ever so much, Malcolm I'll pay you back—in a little while."

"Very glad to be able..." he said.

But you're not going to keep me here. I'll get away somehow, money or no money.

She stood there with the check in her hand, and he stood before her, with his head bent. Because he did not want to look at her.

"I hope this doesn't put you out, Malcolm," she said.

Oh, no! Keeps me in, he thought, and forgot to answer her. And in a moment she went away.

He sat down in a chair by the window and lit a cigarette. Could borrow some money from Arthur, he thought. Just enough to keep going until I find a job. Could go to the company's office, and see about a shore job. No. They might think... No. Somewhere else. Look in the newspapers.

Later in the morning, when he was working on the jigsaw puzzle, he heard someone go into the bathroom, his bathroom. Mr. Pond, that had to be. It made him unhappy; he didn't like to see new faces. He went down to lunch with reluctance, but he was cheered by finding Arthur there.

"My brother, Mr. Pond," Arthur said.

"How d'you do?" said Mr. Pond.

He looked like an Indian, Malcolm thought, lean and impassive, in a gray suit with a white pin stripe; flat cheeks, a coppery skin; black hair parted on the side. He was pleasant, but he was mysterious.

There were six of them at the table, and Ben came in to help Lydia. This was an innovation. Helene seemed surprised to see him, in his white jacket, waiting on people with great style.

Malcolm studied him with absorbed interest. So he thinks he saw me do that, fix that drink, he mused. That's a queer thing...

Very, very thin, Ben was, with knobby wrists, and a big nose, and a worried, woebegone face. He stooped to pass the dishes; he almost cringed. He's always like that, Malcolm thought. Servile. Tries to please—too much. You see that type in a ship now and then. A steward... And you don't trust 'em. Because they'll say anything, do anything they think will please you.

Did he tell that story about the drink to please somebody? But please whom? It was Helene he told, and it certainly didn't please her. Is there anybody, who'd want to believe I did that? That I killed Aunt Evie?

And did I kill Aunt Evie? That sickening doubt and panic came back over him in a wave; he had to get away. Quick... Everyone was nearly finished, just drinking coffee, and Jenette still eating his dessert.

"If you'll excuse me, Helene," Malcolm said. "Letter I— I—I've got to finish."

"Mr. Pond's going to read the will, Malcolm," said Arthur.

"Oh, now?" said Virginia.

"Unfortunately I can't stay. I shan't be able to attend the— ceremony," Pond said. "I have to go to Washington tonight."

Where's Aunt Evie? Malcolm thought. Upstairs, is she, the poor old girl? Or did they take her away? I don't want to hear her will. But if it's the proper thing...

The two girls went out of the dining room, and Pond and Arthur and Malcolm went after them. And Jenette. Jenette shouldn't come, Malcolm thought. This is a family thing. But Jenette did come; he sat in a chair beside Helene, and crossed his legs, one ankle on his knee. He looked impudently at home.

"I, Evelyn Rounsay Chatsworth..." Mr. Pond was reading, holding the document well away from him. Far-sighted, Malcolm thought. Keen Indian eyes.

"To my niece Helene, wife of Arthur Drake, the sum of five thousand dollars..." And the same to Virginia. Poor old girl wasn't so well off, after all.

"To Malcolm Drake, at present residing in Willow Bridge, Connecticut, the sum of twenty thousand dollars—"

"Hold on!" said Malcolm.

Mr. Pond glanced at him, and went on reading.

"In consideration of his handicapped condition, and to mark my confidence in his ultimate rehabilitation—"

She's got no right to talk like that! Malcolm thought. Handicapped and rehabilitation... No!

Mr. Pond was still reading. Malcolm heard Arthur's name, and then:

"To my beloved friend and teacher, Marian Jancy Foxe, the sum of ten thousand dollars in recognition of her invaluable work in forming Joy Now..."

Did he say twenty thousand—for me? Malcolm thought. It's—it's a trick. He wants to see what I'll say, how I'll act. Wants to see if I'm all right, normal, and so on. Aunt Evie thought this up, and it's a nasty trick. All right! All right! Nobody's going to get a rise out of me.

He lit a cigarette and leaned back, and Mr. Pond ceased his reading.

"Is that all?" Jenette asked.

"Oh, yes. Yes, that's all, Mr.—"

"Jenette is the name. Ivan Jenette. Nothing about me?"

"Why, no, Mr. Jenette. No."

"The damned old bitch!" said Jenette.

"Look here!" said Arthur.

Jenette rose.

"Good-by, Helene," he said, standing before her and giving her a stylish bow, heels together. "Oh... Must you go, Ivan? Now?"

"Oh, yes."

"I don't know about trains," she said. "Ben will drive you—"

"I don't care about trains," said Jenette. "And I'll walk, thank you."

Helene was plainly trying to keep this from being a scene.

"We'll see you soon, Ivan?" she said earnestly.

"No," he said, with a smile. "You certainly won't, Helene. Good-by, la compagnie."

He went out of the house, leaving behind him a blank, stiff silence.

"Ivan's a musician, you know," said Helene. "Very artistic. Very high-strung."

Her attempt to adjust the situation was a failure; her pretty, forced little smile was a failure. Mr. Pond looked at his watch.

"I'm sorry to hurry away, Mrs. Drake, but—"

"Have a drink?" said Arthur.

"Oh, thanks..."

Malcolm got up and walked out of the room and up the stairs, making for his own room. Jenette's door was open and he was in there packing a bag. He turned his head and looked at Malcolm.

"Brother, can you spare a dime?" he asked.

"Well, how d'you mean?"

"I haven't got any money," said Jenette. "If you could lend me a hundred dollars—or a thousand would be better...."