RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

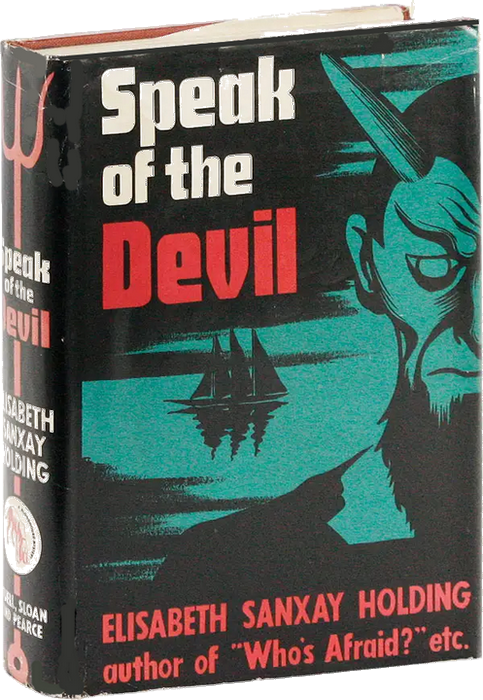

Duell, Sloan & Pearce, Inc., New York, 1942

"Speak of the Devil" is a compact, atmospheric mystery set on the fictional Caribbean island of Riquezas. Karen Peterson, traveling by ship to Havana, is charmed by a suave man named Mr. Fernandez, who persuades her to take a job as hostess at his new island hotel on Riquezas. Though reluctant, she accepts. Once there, Karen quickly senses that the hotel is a nest of secrets. The staff and guests all appear to be hiding something...

MISS PETERSON opened the door of her cabin cautiously, and glanced along the alleyway to the smoke room. And saw Mr. Fernandez looking at her. He rose.

With a sigh, she came out, closing the door behind her. She was well able to cope with Mr. Fernandez, but the weather was singularly oppressive and she felt tired; she would have preferred to avoid him. But it was too late now and she went along the alleyway, tall, broad-shouldered, and long-limbed, very handsome in her black evening dress, with her blond hair in thick braids around her head.

"Dear lady!" said Mr. Fernandez. "I haven't seen you since lunch time."

"I was resting," said Miss Peterson. "I don't like this weather."

"The glass is very low," said Mr. Fernandez.

"I thought so," she said. "You can feel it."

He drew back a chair for her, and she sat down at the table.

"It's all right on a ship," he said. "But on shore... When I think of my new hotel!"

They were both silent for a moment. They had both felt this breathless quiet before; they had seen this slow, sullen sea before; they knew the fury that was gathering somewhere.

"What's yours, Miss Peterson?"

"Gin tonic, thanks," she said.

"Make it two, Henry," said Mr. Fernandez, and brought out his gold cigarette case.

He was, after his fashion, a handsome man; a big fellow, dark, clean-shaven, with black wavy hair that bushed out a little behind the ears. He was soberly dressed in a white mess jacket and black trousers, but nothing could disguise or subdue his prodigious exuberance.

"Well, little lady?" he asked.

"I'm five feet ten..." said Miss Peterson.

He was not to be deflected.

"Been thinking over my proposition?" he asked earnestly.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Fernandez..."

"You don't know your own heart," he said, briefly.

Miss Peterson turned her sad sea-gray eyes toward the open doorway on to the afterdeck.

"You love me," Mr. Fernandez said.. "Admit it."

Salesmanship, she thought. When that man in Puerto Rico wanted me to sell refrigerators, that was the line he advised. Be positive, he said. Never negative. Tell people that they want an icebox. Be crisp. That was another thing he used to say. He told me I'd be an outstanding success at selling if I'd only give it a trial. But I wouldn't.

The ship had begun to pitch a little; as the stern dipped she saw the leaden water that seemed not to move. The sky was leaden too, no breeze. Why do I do some things, and not do other things? she asked herself. I certainly don't act according to reason. I look reasonable; and nobody can see through me. Do we ever understand one another?

She thought about that, lost in one of her Norse reveries; one of those melancholy moods that came over her occasionally, particularly in hurricane weather.

"Well?" said Mr. Fernandez, with a fond laugh. "You're a serious little lady, aren't you?"

"I seem to be," said Miss Peterson, stifling a sigh. She sipped the gin tonic.

"If you can't make up your mind, I'll make it up for you," he said. "You're going to leave the ship at Riquezas and you're going to stay at another hotel while we put up the banns, and then we're going to be married. Then you're coming to live in my new hotel. A beautiful hotel, modern, beautiful. You'll have your own car. You'll have everything. Like a little queen. When the season's over, I'll take you up to New York and I'll buy you the finest outfit of clothes—"

"Let's come to an understanding, Mr. Fernandez," she said, suddenly businesslike. "I can't marry you, ever. There's no chance of my changing my mind, ever."

"La donna è mobile..." he sang in a very good baritone.

"I don't know about that," said Miss Peterson. "But please take this as final. I like you, and I appreciate your offer. But I'm going on to Havana. I've got a job waiting for me there."

"You like me..." said Mr. Fernandez, seizing on that. "Liking and respect—what's a better basis for a marriage?"

"I don't want to get married," said Miss Peterson.

"That's because you don't understand," he said. "You're unawakened. You—"

She had heard Mr. Fernandez on that subject before, and she did not relish it.

"No," she said, in her slow voice. And nobody could possibly think that she meant yes.

Mr. Fernandez moved his glass so that the ice clinked in it.

"Maybe you haven't known me long enough; only five days," he said. "Everybody's not like me. I make up my mind like that!" He snapped his fingers. "But that's my nature. You may be different. It may take you a long time to know..." His black eyes rested upon her face. "But once you do love—or hate—God!"

Well, if that's what you like to think, Miss Peterson said to herself. At the moment, the only emotion she felt was an overwhelming boredom.

"Another drink, little lady?"

"Thanks," she said. "I'd like it."

"Henry!" he called. "Encore!" He turned back to Miss Peterson. "You're low-spirited," he said. "I've never seen you like this before."

"The weather," she said.

He did not care for that.

"You're not happy," he said. "Tell me—what is this job in Havana?"

"It's in a shop," she said. "They want someone who can speak English, and Spanish, and German."

"I know how good your Spanish is," he said. "But German, too?"

"Yes," she said.

"A good job?" he asked.

"Good enough," she said.

"I wonder..." he said. "I wonder what's happened to make you go wandering around the world like this?"

"I wonder, myself," she said, with candor.

"I wonder," he said leaning across the table and lowering his voice, "what's happened to make you turn against love?"

You'd be surprised, thought Miss Peterson. It's people like you. Men you meet in planes and ships and hotels and trains, talking about love. She said nothing out loud, and he leaned back in his chair and took a sip of his drink.

"Lady," he said, "I'm going to make a different proposition. We'll forget about marriage for the time."

"I'm going to Havana," said Miss Peterson.

"Come to Riquezas," he said. "Whatever they were going to pay you in Havana, I'll double it."

She looked up.

"Come to my new hotel as hostess," he said. "You can name your own salary. You'll have a nice room and bath, all to yourself. Fine meals. Plenty of time for swimming, riding, tennis. It's a position of dignity," he added.

This position seemed to Miss Peterson very much more attractive than the one in Havana. Especially at double the salary. But she saw grave drawbacks.

"I'm afraid—" she began.

"Yes," he interrupted. "You're afraid I'd bother you—try to make love. Well, look here..." He paused. "We'll get to Riquezas tomorrow, on the twentieth of September. I give you my word I won't say another word about marriage or love, until the twentieth of November."

Miss Peterson had heard a good deal of talk about Mr. Fernandez since she had come on board at Trinidad. He was a big man in Riquezas; he had a hotel, a club, he owned the sole fleet of launches, he had an interest in the biggest department store, he was in half a dozen other things. He had his enemies; some people spoke of him with fury. They called him bullying, grasping, vulgar, even ruthless. She thought it not impossible that he might have some of these defects; but she thought he would keep this bargain.

"But you'd be thinking all the time that I was going to change my mind," she said.

"Certainly," he said, seriously. "I'm pretty sure you will, too. But if you don't—all right. I can take it."

"I don't think it would be fair to you," said Miss Peterson.

"My dear lady," said Mr. Fernandez. "Even apart from my personal feelings, it would be a big advantage for me to have you in the hotel. It is hard for me to find the right person for that job."

She liked that better. She understood very well his Latin fashion of combining love and business.

"I don't want an American," he went on. "Some of the die-hard Britishers don't like them. I don't want an English girl, because they don't understand American tourists—the backbone of my business. You're neither English nor American. I don't know what you are, and I'm not asking. Simply you'd be a Godsend in that job."

She liked him even more for this. She was wont for the most part to call herself English; she sometimes advertised for a post as 'an English gentlewoman.' Her passport was Uruguayan; but her birthplace was Minnesota. A strange rebellion of her mother's had taken her away from home in her childhood. Still in her twenties, she had traveled far and seen much. But she did not forget the farm where she was born, the wide rich fields in summer, the winter snows. It suited her to wander over the world, but her roots were back there; she had been nourished by reality, and however fantastic her experiences were, she herself was realistic, sober, a little aloof. Not romantic.

"So that if you take the job," said Mr. Fernandez, "you'll be under no obligation to me. On the contrary, you'll be doing me a favor."

"Then—thank you," she said. "I'll come, Mr. Fernandez. On two months' trial."

"Bueno!" he said with a sudden flashing smile.

They went down to the dining-saloon then. Mr. Fernandez sat at the Captain's table because of his importance in Riquezas; Miss Peterson sat at the Purser's table, because the Purser knew her and enjoyed her company. The other people who sat at the table had not yet come down; Mr. Wavill sat there alone.

"I'll be leaving you tomorrow," said Miss Peterson. "I'm getting off at Riquezas."

"Well..." said Mr. Wavill. "You know what you're doing."

No, I don't, thought Miss Peterson. Nobody ever does. For her Norse mood still lingered; the oppression in the atmosphere lay heavy upon her.

"I won't talk business now," she said, "but tomorrow morning I'll come formally to your office, and ask about a refund for the rest of my passage."

"Suppose we have a bottle of Sauterne?" said Mr. Wavill. "As long as this is au revoir..."

"Thanks!" said Miss Peterson. "That would be—"

"Damn!" he murmured. "Here comes Mrs. Fish."

He rose politely, and Miss Peterson looked up with a smile as their table companion approached. She was a tall, slight woman, all in black, even to her stockings, with a long-nosed, chinless face like a melancholy goose, and black hair in a somewhat untidy knot at the nape of her neck. She was amiable enough in her fashion; but she was depressing, so fatigued and silent.

"You'll take a glass of wine with us, Mrs. Fish?" asked the Purser.

"Oh, no thank you," she answered, "I think it gives me neuralgia."

The wine came, and the steward filled their glasses.

"Well..." said Mr. Wavill, raising his glass and looking at Miss Peterson with a faintly sardonic smile; "I hope you'll like—Riquezas."

"If I don't, I'll go somewhere else," said Miss Peterson.

They drank the wine and were silent in a friendly fashion. The electric fans whirred softly, stirring the heavy air; as the ship pitched, the gray water seemed to slide up toward the ports, very slow, very menacing. From the Captain's table came Mr. Fernandez's voice, loud, resonant; an attractive voice.

"One doesn't feel much like eating in this weather," said Mr. Wavill.

"No," Mrs. Fish agreed.

"Let's give up," said Miss Peterson; and they all rose. Mrs. Fish went to her cabin, and Miss Peterson and Wavill sat on deck for a time in the stifling dark; then he went to his office, and she sat alone. She remembered a hurricane in Martinique when she had been in charge of two children... She sighed and remembered an earthquake in Chile. Life is very strange, she reflected.

"Well..." said Mr. Fernandez's voice from the dark. Her chair was on the forward deck; he sat down in one beside her, he offered her a cigarette and lit one for himself, and smoked for a time in silence.

"There's one thing I'll have to explain," he said. "A complication."

A woman I suppose, thought Miss Peterson. If it's too much of a complication, I'm not going to bother with it.

"I took on a girl as hostess," he said. "But she won't do." He was silent for a time. "I was a fool."

"Do you mean she's there now?" asked Miss Peterson.

"Yes," he said, "but she's not hostess any more."

"No? What is she then?"

"Different odd jobs," said he.

"An English girl?"

"American," he said.

There was a long silence this time.

"When I first met this Cecily," he said, "I thought she'd be a fine hostess. She's very musical and so on. But it didn't work at all. She doesn't get on with people. She was unpopular. It was a business arrangement pure and simple, and I couldn't afford to keep it up. I had a talk with her. I offered to pay her fare home." He began to speak in Spanish. "Inutil. We had nothing but arguments, protestations. She begged to be allowed to stay in the hotel, if it must be even in the kitchen. I was sorry for her."

"And she's still there?" asked Miss Peterson in English.

"Sí. Yes. I gave in. I let her stay. She has charge now of the ladies' powder room."

"I don't like that much," said Miss Peterson.

"Neither do I," he said. "It was a weakness on my part and now I'll insist on her going. It's nothing serious, but I thought you'd better know."

"I don't like it," she repeated.

"Dear lady," he said, "look at it this way. You'd already agreed to come. I needn't have told you a word about this. If it is obviously what you think it is, would I have told you? Would I have asked you to come? No! It's nothing serious. Awkward; that's all. Cecily will leave the island by the next boat; take my word for it."

This time Miss Peterson did not believe Mr. Fernandez. Not wholly. She did not believe that he had kept on his former hostess out of sheer kindness or because he did not like scenes. Also if it had been a matter of no importance, he would not have mentioned it.

"I don't like scenes, myself," she remarked.

"There won't be any scenes," he said. "Dear lady, I'm not a fool. Remember too that I have a reputation in that island. I shouldn't be likely to prejudice my business for a girl, eh?" There's something in that, she thought. I don't think he'd risk his reputation for anyone or anything.

"A slight awkwardness, that's all," he said. "But the girl will leave by the next boat, and we'll forget it. Have you told the Purser you're landing tomorrow?"

"Yes," she said. He rose.

"We may arrive early," he said. "You'd better turn in, and get some rest."

"Presently," she said.

He took her hand and raised it to his lips; kept it there a little too long.

"Good night!" she said, very clearly.

He left her there and she sat relaxed in her chair, her long legs stretched out, her ankles crossed. She was an expert packer and she could get ready in half an hour. She did not want to go to her cabin. It was better here, in this airless night.

"I didn't know you were going to Riquezas," said Mrs. Fish's flat, subdued voice from the dark.

"Oh, yes..." said Miss Peterson. She looked about her, but she could not make out the black figure in the shadows.

"I am too, you know," said Mrs. Fish.

"That's nice," said Miss Peterson with courtesy.

"I'm going to the Hotel Fernandez," said Mrs. Fish. "Are you?"

"I've got a job there," Miss Peterson answered. "Hostess."

"Oh. What does a hostess do?" Mrs. Fish asked.

"I'll try and make things pleasant for people," said Miss Peterson. She didn't really know what her duties would be, but she thought it would be unfair to Mr. Fernandez to admit this ignorance.

"I'm so glad you're going to be there," said Mrs. Fish. "I hear you're a trained nurse."

"I'm sorry, but I'm not," said Miss Peterson. She did not want Mrs. Fish, or any other guest of the hotel to know that she was a licensed masseuse. She had learned by experience that when people found that out, they were disposed to make extraordinary demands on her; to cure headaches, to take care of babies, to prescribe for hangovers. But Mrs. Fish had somehow found out something.

"Well, it's practically the same thing," said Mrs. Fish. As others had said. "I'm glad to think you'll be there. Such a strong personality."

"Thank you," said Miss Peterson, stifling a sigh.

There was a soft rustle, and a strong gust of perfume, lily-of-the-valley. Mrs. Fish was close to her now.

"Won't you sit down?" Miss Peterson asked, feeling that this was her duty toward a prospective guest of the hotel.

"Thank you!" said Mrs. Fish, and did sit down in the chair that Mr. Fernandez had vacated.

"You see," she said, "my husband was killed last year."

"How dreadful!" said Miss Peterson in her mild, slow voice.

"It's a nerve-strain," said Mrs. Fish. "Some day, when I'm not so tired, I'd like to talk to you about it."

"Oh, certainly!" said Miss Peterson. But it seemed to her that her new job required a little more of her. "There's nothing like travel, to take your mind off a thing like that," she added. "I should think a nice long stay in a place like Riquezas would help you a lot."

"Well, this isn't a pleasure trip," said Mrs. Fish. "I'm going to Riquezas for a reason." She paused again. "We must talk about it later on. But I'm so tired just now. I think I'll close my eyes and try to get a little sleep."

"That's a good idea," Miss Peterson said. She too, had had the idea of sleeping here, but the lily-of-the-valley perfume was so strong..."I'll have to go to my cabin," she said. "Some last minute things... Good night, Mrs. Fish."

"Good night," said Mrs. Fish. Her fatigued voice seemed to trail after Miss Peterson as she moved away. "You see," she said, without emphasis, "my husband was murdered." Miss Peterson stopped, stood still for a moment. Then, with more haste than was usual with her, she went on her way. I don't want to hear any more about that, she thought. Not now. Not in this weather.

THE sun came up in the morning, but it was a menacing sun; dull, veiled by clouds that did not seem to move. The sea had risen, there was a long heavy swell, the ship pitched heavily.

Miss Peterson staggered as she finished her packing, the light wicker chair in the cabin lurched, everything creaked and strained. The dining saloon was almost empty, Mrs. Fish did not appear, the steward came running downhill with his tray, and checked himself as the floor rose up; there were fidds on the tables.

She ate a good breakfast though, because in the background of her mind was the thought that lunch might be long delayed. She saw the Purser, she got a refund on her passage and a landing permit, and the ship stopped. It was worse then; they rolled helplessly in the long swell that came driven by the invisible fury; the deck chairs were all folded up and lashed, there was a great quiet on board.

Miss Peterson stood on deck, her nice narrow feet in low-heeled blue and white shoes planted wide apart to keep her balance, a cool blue and white print dress upon her tall frame, a dark blue hat upon her blond head. Riquezas lay before her, a flat low island looking very unimportant. A launch was coming toward them; the accommodation ladder went down.

"Disagreeable weather," said Mr. Fernandez at her side. And presently Mrs. Fish came, in a sheer black dress and a white helmet with a black puggree hanging down the back. They stood in silence watching the mail sacks go into the launch, they watched the trunks and bags of Miss Peterson and Mrs. Fish and Mr. Fernandez go down. "Well! Au revoir!" said the Chief Officer, and shook hands with them.

Mr. Fernandez went down the ladder first, Mrs. Fish followed, and Miss Peterson went last. The gray sea came up at her, and swooped down; the world seemed to swing in a sickening arc. But down she went slowly; she waited until the launch came up, a sailor caught her arm and helped her on board, and off they went.

The engines of the ship started, the propellers churned; off she went on her own way.

"Going to blow, sah," said the Negro at the wheel.

"May not hit us," said Mr. Fernandez.

"Got to do so, sah. When 'ee don't come for two years, come in three years—"

"Nonsense! Nonsense!" said Mr. Fernandez.

He was, in a subtle way, changing as he sat in his launch; he was growing bigger and grander. When they reached the jetty, he stepped ashore like a king and there was a chorus of greetings from the little crowd assembled there.

"Glad to see you back, sah...Fernandez, how are you?... Did you have a good trip, Mr. Fernandez?"

He raised his helmet, he made a vague gesture of salute with his hand, he smiled. He gave the keys of their baggage to a man in a sort of porter's uniform, and he led them along to an elegant, cream-colored roadster with a tan top attended by a chauffeur in khaki. He waved his hand again as they set off through the town.

A nice little British town, colored policemen in white gloves, a wide square after the fashion of the Spanish plaza, a bank with plate-glass windows, shop windows filled with tourist wares, a post-office with an arcade before it. But the sun was gone now; a fitful breeze stirred the dust, some of the shops had their shutters up already. They crossed a bridge, and entered the open country. They went past fields, with here and there an old estate house or a modern villa standing stark and defenseless in this flat island beneath this sky of lead.

The Hotel Fernandez was on the beach, an elaborate stone building with turrets, a patio, a colonnaded terrace. On the lawn of parched grass stood little iron tables under striped umbrellas that were shaking and straining in the rising wind.

"Those'll have to come in," said Mr. Fernandez.

They entered a large and handsome lounge. "Miss Peterson," he said, "if you'll go to the sundeck, if you please... Straight ahead of you. I'll look after Mrs. Fish—personally."

He led Mrs. Fish by the arm toward the desk, and Miss Peterson continued straight ahead, as he had told her, to a glassed-in veranda that overlooked the sea; there were palms and ferns in pots, a pleasing harmony of green and black chintz, comfortable big chairs and little glass tables. Mr. Fernandez joined her in a moment, followed by a waiter.

"I think we might have a little drink to celebrate," said Mr. Fernandez. "What would you like?"

"I think a lemonade, thanks," said Miss Peterson.

"A lemonade," he repeated to the waiter, "and bring me a beer."

Miss Peterson was standing by the open window and he joined her. The sea was running high, pounding on the white beach, breaking into high crests on the barrier reef. A very high sea for so still a day.

"Yes..." he said, half to himself. "Well..."

He lit a cigarette for her; when the drinks came, they sat down.

"I'm afraid I'll be very busy for a while," he said. "But I'll tell the housekeeper to look after you. Lunch in your own room perhaps. You can look around and get the feel of the place—the atmosphere, eh? And we can meet here for cocktails at—let's say five o'clock. If all goes well."

"Bueno!" she said.

They fell silent, and the pounding of the surf came to them, loud and ominous.

"Of course—" he began, and stopped short as a girl entered.

She was a slight girl in a black dress, and black shoes and stockings. Her long dark hair was brushed back from her forehead, her face was pale, with high cheekbones and a wide rouged mouth, her eyes were a clear, light aquamarine. She was a very unusual-looking girl, and very beautiful.

"Mrs. Barley couldn't leave just now, sir," she said. "So I came to see if I could do anything."

"Ah!" said Mr. Fernandez, somewhat wryly. "Well...Miss Peterson, this is—" He paused. "Cecily," he said. "Cecily, this is Miss Peterson, the new hostess."

The girl made a curtsey. That was a very strange thing for an American girl to do; it was either ironic, or theatrical, or both.

"How do you do?" said Miss Peterson amiably.

"Thank you, madam," said the girl. "Shall I show Miss Peterson her room, sir?"

Mr. Fernandez was more ill at ease than Miss Peterson had believed he could be. "Never mind," he said.

"I think that would be a good idea, Mr. Fernandez," she said rising.

"Bueno!" he said, rising himself. "Then I'll see you at five..."

Miss Peterson followed Cecily through the lounge and into the elevator; they rode up only to the second floor, they went along a corridor and around a corner where the girl opened a door.

"This is the room the former hostess had, madam," she said.

"That was you, wasn't it?"

"Yes, madam."

"Won't you sit down and have a smoke?" Miss Peterson asked. "I'm sorry, but I don't know your name, Miss—?"

"I'm called Cecily now, madam."

"Won't you sit down and talk to me a little? I'd like to get a little information."

"I'm afraid I couldn't help you, madam."

"It's for you to say of course," said Miss Peterson. "But if you feel like telling me some of the chief difficulties—?"

"My experience wouldn't be helpful, madam," said Cecily. "I failed."

"Maybe I'll fail too," said Miss Peterson.

"I'm in charge now of what they call the ladies' powder room," said Cecily, with her pale clear eyes on Miss Peterson's face.

"Well, I've never done that," said Miss Peterson. "But I've worked in a restaurant."

She felt as if she were dealing with a wild gazelle, she felt that if she made one brusque gesture, this young creature would flee. For in spite of the black uniform and the 'madam,' and her gentle voice, Cecily was wild. Certainly not the type I'd expect, Miss Peterson thought. She's obviously a very well-bred girl. And, I should say, a dangerous girl.

"I hope you'll like the position, madam," she said.

"I wish you wouldn't call me 'madam,'" said Miss Peterson. "After all, here we are. Two human beings. Two women. You've lost the job; and I've got it. The wheel turns. Who knows what's going to happen tomorrow?"

The wild gazelle took a few steps into the room, lured by Miss Peterson's calm good-humor.

"I suppose I'll have to leave the hotel now?" she said. "Even the powder room."

"I should think you could find something much more interesting," said Miss Peterson.

"I want to stay here," said the girl. "I've offered to stay without any pay at all. Just my room and meals. But now I suppose I'll have to go."

"I hope not," said Miss Peterson.

The girl glanced at her quickly.

"Of course," Miss Peterson went on, "I've just got here, and I don't know yet what's expected of me. Or what I can do. Won't you sit down and tell me what you had to do when you were the hostess?"

Cecily did sit down then, on a straight-backed chair near the door.

"I played the piano," she said. "Every morning from eleven to twelve, and in the afternoon at tea-time. And on Sunday we gave a concert in the evening. The cellist and the first violin from the orchestra, and myself. But—" She paused. "My playing wasn't liked," she said.

"Well, I don't play the piano," said Miss Peterson.

"You'll have to 'greet' people," Cecily went on. "You'll have to dance with the men, and sit and talk with the women. You'll have to get on with people. With everyone."

"I'm rather good at that," said Miss Peterson.

"I'm not," said the girl.

"Have a cigarette?" asked Miss Peterson.

The girl hesitated and then took one, and she relaxed a little as she began to smoke.

"You must have studied music," Miss Peterson observed.

"Yes. I have."

"I hear you're an American," said Miss Peterson.

"I'm half Polish. My mother was from Warsaw."

"That's interesting," said Miss Peterson. "Do you speak Polish?"

"A little."

Miss Peterson spoke a few words in a foreign tongue; the girl's clear eyes were fixed intently upon her.

"I'm sorry," she said. "I'm afraid I don't understand that."

"Well, maybe it's not good Polish," said Miss Peterson.

"Well, if it's a dialect..." said the girl.

A puff of wind came through the open window, and Miss Peterson got up and went to look out. "You've been here—how long?" she asked.

"Over four months."

"Then I don't suppose you've had any bad weather?"

"I don't pay much attention to the weather," said Cecily. "It's been hot enough, and it's rained, if that's what you mean."

"That's not what I mean," said Miss Peterson.

"Miss Peterson?" said a voice, and the girl rose quickly.

A short, gray-haired woman with a long upper lip stood in the doorway. "I'm Mrs. Barley, the housekeeper," she said earnestly, and moved to let Cecily go past her out of the room. "Have you everything you want?"

"Yes, I think so, thank you," Miss Peterson answered.

"I'm afraid," said Mrs. Barley, "that we're going to have some disagreeable weather."

"Is there a warning up?" asked Miss Peterson.

"Oh, you know then?" said Mrs. Barley. "Yes. They've just put up the flag."

They were both silent for a moment.

"Well," said Mrs. Barley, "we only have five guests now, and one came by this boat. The season doesn't really begin until the end of October as a rule. We have no Americans here. Fortunately."

"Don't you like Americans?" asked Miss Peterson.

"Oh, very much!" said Mrs. Barley. "But they're more excitable. If we're going to have disagreeable weather... I'm sending up a man, Miss Peterson, to put up the shutters."

Another puff of wind came in and stirred Mrs. Barley's hair. And Miss Peterson thought of what was coming across the water, rushing past one island, sweeping across another, giving a careless glancing blow at a third. Nobody could know where the fury would strike; at this moment, hundreds of people were doing what they could to prepare for the onslaught; men were looking at their cane fields, at the banana plantations that might vanish overnight. People were going to die.

"Let me know if you want anything," said Mrs. Barley.

Like a goddess. Suppose I answered, give me peace, thought Miss Peterson.

Her trunk and her bag came, and she unpacked them; a colored boy came up with an excellent lunch on a tray. Fried flying fish and plantains, salad, an ice, and very fine coffee. She was hungry, and she enjoyed it, and she was glad to be alone to do a little thinking.

She thought about Cecily. That's a very strange child, she said to herself; and I don't wonder that Fernandez is afraid of her. There's a terrific vitality in her, and it's exactly the other sort of vitality from his. He's exuberant and expansive, and she's channeled all in one direction, whatever it is. I should say that anything she really wants, she'll get. Even if it's Carlos Fernandez. An interesting child... Her hair is certainly dyed; and she certainly doesn't speak any Polish at all. Because when I spoke to her in Swedish, she didn't know the difference. Interesting, and dangerous...

She finished her lunch, and then a man came to put up shutters at her windows. That was depressing, and she thought she would go outdoors while she could. But a chambermaid came to the door just as she was going out.

"Mistress, Mis' Fish say, will you please step by she room? On the next floor, mistress, three-fifteen."

I don't want to see Mrs. Fish, thought Miss Peterson, half-surprised by her own reluctance. I don't want to hear about her husband. Murdered, she said. That's no reason for disliking the poor woman, of course, but there's a sort of aura about her, lily-of-the-valley perfume, and black clothes—and death.

She sighed and straightened her shoulders. Come now! she said to herself. Be a hostess. And she walked up one flight of stairs and knocked at the door of Mrs. Fish's room.

"Come in," said the flat, tired voice, and entering, she found Mrs. Fish lying on the bed in a gloomy dusk, the windows shuttered. "I have a toothache," she said. "I wonder if you can do anything?"

"Oh, yes," said Miss Peterson, and returning to her room, she got a tiny plaster, two aspirin tablets, and three tablets of sodium bicarbonate. "I'm afraid I'll have to turn on the light," she said.

"Oh, by all means," said Mrs. Fish.

She was wearing a crimson silk kimono embroidered with gold dragons; and that made her look paler and more tired than ever; her black hair was loose, spread out on the pillow. Miss Peterson moved quietly about; she went to the bathroom and mixed her tablets in a glass, adding a brown cough drop she had in her purse, to give it a strange flavor and color.

"What's that?" Mrs. Fish asked.

"Oh, that's a secret," said Miss Peterson, who understood the therapeutic value of mystery.

Mrs. Fish sipped this exotic drink, and Miss Peterson glanced about the room. A big wardrobe trunk stood in a corner, still locked, but a suitcase was open on a chair, and a few things had been set out on the chest of drawers. There was a photograph in a silver frame, Miss Peterson glanced at it, stared at it, moved a little nearer to examine it.

It was a photograph of the Devil, a big, burly, fierce devil, with a bold nose and mocking eyes and an elegant Vandyke beard; he stood with folded arms, dressed in a mantle and a cap that revealed his horns.

"Are you looking at that picture?" Mrs. Fish asked tonelessly. "That was my husband. In a masquerade costume. It suited him very well, don't you think?"

"Oh, yes!" said Miss Peterson. She went into the bathroom and held the tiny plaster under the hot water tap until it was thoroughly warmed, then she applied it to Mrs. Fish's gum.

"Such a relief..." Mrs. Fish mumbled, and closed her eyes.

"I'll come back presently," said Miss Peterson, and withdrew, closing the door behind her. For a moment, she stood in the corridor thinking about that extraordinary photograph. The Devil...she thought. And he was murdered. That's not right. That's not natural. Well...!

She sighed and started down the stairs. The lights were on everywhere, every window was boarded up, it was stiflingly hot. A small group was sitting in the lounge, and she did not feel like talking to them; she made her way to the sundeck, and there was Mr. Fernandez in his shirtsleeves, sitting at a table with his ledgers before him, and an oil lamp, unlit, beside them. There was a damp patch between his shoulder blades, he wiped his face with a mauve silk handkerchief; at the sound of her step he glanced up and rose.

"According to the latest wireless news," he said, "the worst of the storm will pass to the East of us. Ojala Dios!"

"Here comes the rain," she said.

It came like hail, like machine-gun bullets against the boards; the wind had a hollow spinning roar. Miss Peterson sat down, pushing her damp hair back from her temples.

"Nervous?" he asked.

"Oh, no, Mr. Fernandez," she answered. "Only, coming to a new place, there are always things you want to sort out in your mind."

"Cecily, for example?"

"She seems to me to be a very interesting girl," said Miss Peterson.

"Too interesting," said Mr. Fernandez. He wiped his face again. "She came down here on a cruise ship," he went on. "And when she asked to see me, I thought—naturally—she was a tourist, wanting to stop a little longer in my hotel—my other hotel that was. I was very much surprised, I can tell you, when she said she wanted a job. But she seemed—at that time—a very sensible girl, quiet, well-bred. She played the piano for me. I'm no judge of music, but it seemed good to me, very good. She said she could give these little concerts, and that she could help to entertain the guests in other ways. I'd never employed a hostess, but she didn't ask for a large salary, and it seemed a good idea—at the time."

"But it didn't work?"

"Por ejemplo! Complaints began almost at once. The guests complained, the servants complained. She wanted to practice; and one morning she started at seven o'clock, waking up people. I put a stop to that, and then she started practicing at nine, when people were sitting in the lounge. She has no tact. She quarreled with the orchestra leader. She wanted to go into the kitchen, and order coffee and sandwiches for herself, and that led to a quarrel with the cook. I advised her to go home. I told her there was no future here. But she was so insistent upon staying..." He shrugged his shoulders and spread out his hands. "I'm a very good-natured man."

I wonder...thought Miss Peterson.

She could hear the surf, the waves pounding on the beach; the wind had a new note, a thin piping whistle, the rain came more furiously. There was nothing to do but wait, and to hope that the mad violence could find no crevice by which to enter, no weakness in this brave, new building, standing stark and alone by the sea.

The lights went out.

Mr. Fernandez turned on a flashlight, and by its beam he lit the oil lamp.

"I'll have to reassure the guests," he said. "If you'd come too...?"

The guests were admirably tranquil. By the light of two oil lamps in the lounge they could be seen, a middle-aged couple sitting at the card table, but not playing; one old lady was knitting, another was doing nothing at all; a thin, tall man with a weather-beaten, hollow-cheeked face was moving aimlessly about, smoking.

"If you had your electric fans working properly," he said sternly to Mr. Fernandez, "it wouldn't be so bad."

"Unfortunately, the electricity has failed, Major," Mr. Fernandez explained.

"Then why don't you have punkahs?" the Major demanded. "Put some of these worthless boys to work. Gad! No air at all!"

"Do keep quiet!" said the old lady who was knitting.

"What?" the Major demanded. "What did you say, Mrs. Green?"

"I said, do keep quiet," the old lady repeated. "You have just as much air as anyone else."

"What?" he cried. "What?"

"What's that girl doing here?" asked one of the old ladies, and turning her head, Miss Peterson saw Cecily standing in an open doorway near the desk. She was outside the circle of lamplight, and in the shadowy background, she looked all black and white, a little white apron now over her black dress, and a white frilled cap on her head. It was strange to see her there, unmoving.

"Panicked," the Major observed.

Miss Peterson went over to her.

"I've just killed a man," Cecily said, in an even, very low voice.

MISS PETERSON was accustomed to responsibility, and her first thought was to keep those guests quiet. They were all looking toward Cecily, but they were, she thought, too far away to have heard the girl above all the noise of wind and rain.

"Come!" she said, and the girl followed her past the desk and out to the sun-deck. Mr. Fernandez came after them.

"I've just killed a man," Cecily said again. She spoke quietly, her light clear eyes were steady, but she swayed on her feet.

"Sit down!" said Mr. Fernandez; and she did sit down on the couch, straight and rigid in her dainty theatrical uniform, the little fluted cap like a crown.

"I killed a man," she said.

"Yes, we understand that," said Mr. Fernandez. "But how? Where did this happen?"

"In your room," said Cecily. "I shot him. I killed him."

The two tall people standing before her looked down at her with no sign of emotion. She herself was quiet, but she was breathing fast.

"I was going to speak to you, Mr. Fernandez," she went on after a moment. "I knocked at your door and a man opened it and dragged me in. He tried to—make love to me, and I shot him."

"Who was he?"

"I don't know. Someone I'd never met before."

"Where did you get the gun?"

"It was there on a table."

"In my room, eh?"

"Yes," she said, and snapped her teeth shut. But still her jaw trembled. She shivered in this airless place. Miss Peterson proffered a glass of water, and the girl took a sip. Mr. Fernandez looked at Miss Peterson over the girl's head; their eyes met.

"I'll be back in a moment," he said. "In the meantime, we'll say nothing about this to anybody, eh?"

He went out, closing the door behind him, and Miss Peterson sat down in a wicker chair, stretching out her long legs and crossing her ankles.

"I didn't know the wind could be so bad," said Cecily.

"It can be worse than this," said Miss Peterson.

"Will it last long?"

"It will seem long," said Miss Peterson.

There was a moment's silence.

"Just one shot?" asked Miss Peterson.

"Yes," Cecily answered.

"Then maybe you didn't kill him."

"I did. I know I did."

Miss Peterson clasped her hands behind her head, and gazed before her at nothing.

"Well, let's hope for the best," she said. "Let's hope the police believe your story."

There was a moment's silence.

"Do you mean that you don't believe my story?" Cecily asked with a sledge-hammer directness.

"That's right," said Miss Peterson. "I don't."

"You don't?" Cecily repeated. "But—why? What is it you don't believe?"

"Well..." said Miss Peterson, "you said you were dragged into Mr. Fernandez's room by an unknown man. He attacked you, and you found a gun lying on the table, and you fired one shot, and you killed him. If I were you, I shouldn't give the police that story."

"You mean—" Cecily began, and stopped short. One of the old ladies was trying to open the glass doors, a spare and very straight old lady in a white blouse and a long black skirt, and a broad belt about her neat waist-Her gray hair was done in two hard little rolls up from the temples, giving her an alert air. She rattled the door handle furiously in a sort of convulsion of annoyance.

"Mrs. Boucher," said Cecily. "She hates me."

"You'll remember not to say anything, won't you?" said Miss Peterson, rising. She looked at Cecily then, and the girl looked back at her, her strange, pale eyes brilliant. "All right!" she said.

Miss Peterson tried to open the doors from inside, but the old lady kept on twisting at the handle. The doors burst open suddenly, and Mrs. Boucher rushed forward against Miss Peterson.

"I want to go up to my room," she said.

"Certainly, Mrs. Boucher," said Miss Peterson, a little surprised at so ordinary a request after such an energetic struggle.

"Well, it seems that the lift's not working," said Mrs. Boucher, indignantly. "I can't walk up five flights of stairs at my time of life. And I want to go to my room. It's time for me to take my pill, and I want to write a letter. I want to go up at once!"

In the absence of Mr. Fernandez, Miss Peterson felt obliged to cope with this.

"I think we can arrange that, Mrs. Boucher," she said. "If you'll come back into the lounge, I'll see..."

She closed the glass doors as they went out, and glancing over her shoulder, she saw Cecily in her theatrical uniform, standing in there as if in a glass cage. The other guests still sat in the lounge, with three oil lamps on tables; they were silent now, in a haze of tobacco smoke. There were none of the boys about, and she borrowed a flashlight from the Major, and went out to the kitchen in search of them.

The kitchen presented an extraordinary appearance. A big room lit by two oil lamps, it was crowded with people sitting and standing; an old Negress was on her knees before a chair. "Oh, Lawd! Take away this wraf!" she chanted. "You got some good an' faithful people here, oh, Lawd!"

Miss Peterson had a few words with the cook, a thin and sorrowful man with gold earrings, standing before the big stove in a heat that was beyond belief. He was attending to his business.

"Maybe the end of all things," he said, stirring a red sauce.

"I want two good strong boys, to carry Mrs. Boucher up to her room," she said; and the cook called two for her. They were, oddly enough, enchanted by the proposal; they found it humorous. "But you mustn't laugh!" Miss Peterson said.

"She goin' to ride up in she chair like the great golden idol!" said one of them, bent double with laughter.

"If you drop she," said the cook, "going to be calamity."

"But you must stop laughing," said Miss Peterson.

The old lady accepted the arrangement in a matter-of-fact spirit. "I hope you're quite sure the boys haven't been drinking," was all she said.

Miss Peterson picked out a wicker arm-chair, a light chair, and the old lady was light; the boys lifted her without any difficulty, and Miss Peterson went ahead of them with a hurricane lantern. In his modern hotel Mr. Fernandez had a modern fireproof staircase of stone, all enclosed, with a heavy door on each landing. And somehow this staircase caught and held the noise of the wind in a great, steady rushing roar; it pressed against the ears, it confused and almost stunned the little party mounting by the light of the lantern.

When they reached the fifth floor, Miss Peterson opened the door into the corridor, the boys set down the chair and the old lady rose. "Thank you!" she said, and set off briskly. Miss Peterson followed her to light her way; she left her in her room with a lamp lighted and everything very neat, and a vase of flowers, dead as if smothered. The boys had gone; as Miss Peterson returned to the enclosed stairs she could hear their voices from below, muffled by the roar of the wind; they were in complete darkness, and looking down, she saw a little light flash as a match was struck. The flame went out, and the voices were silent, the wind obliterated the sound of their footsteps. She went on, went fast, anxious to get out of this gloomy cavern.

A frightful yell came up to her, and she stopped with a sharp intake of the breath. For of all the sounds in the world, she most feared and dreaded a human voice screaming. Another yell came. "Oh, ma sweet Lawd!"

"What's the matter?" she called, holding out the lantern and looking down. She could see nothing, she could hear nothing but that eternal hollow roar of the wind. "What's the matter? What's wrong?"

There was no sense in going back up the stairs again, she thought. No one there who'd be any help. There's no other way down but this. And she went on down the stairs. She went half sideways, keeping close to the wall, moving the lantern so that she could see above and below her. As she drew near the next landing she stopped for a moment. I hope that door won't open, very slowly, she thought. She went on past the door. She had to go on down, to see what had happened to the boys, and to get out of this tomb.

I'd be very glad to see Carlos Fernandez just now, she thought.

She had lost track of the floors now. She didn't know where the boys had been when that yell came; she wouldn't know when she came to that door. I hope I won't go too far and come out in some sort of cellar, she thought. I hope there's plenty of oil in the lantern. This is the way it is in a nightmare. You go on, and on, and on, downstairs like this, and after a while, you try to run...

Nerves, that's all. This weather, with the glass so low... After all, what does this amount to? I'm going down the stairs, in a hotel, and there's a gale blowing, and two colored boys yelled.

But there's a dead man somewhere. A murdered man.

And what of it? A dead man is one man we don't have to worry about. If... She stopped short, because a door was opening. Slowly. She was two steps above it, and she waited with her back to the wall, holding the lantern steady.

A round white circle of light from a flashlight played on the wall; the door opened wider. "Who's that?" she asked.

"My dear girl..." said Mr. Fernandez. "Where the devil have you been?"

He came toward her, and the heavy door began to close very slowly after him. He laid his hand on her shoulder, looking at her with a smile. In the light of the lantern, his dark face had a copper tinge, his lips looked very red, his teeth very white; there was an air of gaiety about him.

"I was worried," he said. "Those fool boys came running down to the kitchen with some crazy story about seeing the Devil—"

"The Devil?" said Miss Peterson.

"You know the sort of thing," he said. "And you didn't come along... I was getting damn worried. I was afraid you'd slipped, fallen in the dark."

"I didn't hurry," she said.

"Come and have a drink?" he said, and began to push open the heavy door. Over his shoulder she could see the desk, and a young man sitting at the cashier's window, with the light of a green-shaded lamp on his bent fair head. He glanced up, and she saw his face, a wide mouth, a blunt nose; a sort of Pierrot face, half rueful, and half merry.

"Mr. Fernandez..." said Miss Peterson. "About the man in your room?"

He let the door go, and it began to close by itself.

"That?" he said. "Well, I went up to my room. The door was locked, of course. All the doors lock automatically. Well, I opened the door—" He made a gesture with his wrist. "I went in. All right! There's nothing there. No man. No gun. Nothing."

"Nothing?" she repeated.

"Absolutely nothing. Are you surprised? Did you believe the girl's tale?"

"You don't think there's any truth at all in it?"

"Not a word," he said.

No, thought Miss Peterson. That won't do. Cecily wasn't putting on an act. Something certainly happened. "Did you tell Cecily you didn't find anything?" she asked.

"Certainly! I went to her at once. My dear girl, I said, I've looked in my room, and I can't find any dead men. She sat there looking at me with those big, cat's eyes, and never said a word."

"Do you think you convinced her, Mr. Fernandez, that she'd made a mistake?"

"I don't know about that," he said. "I don't care. I said to her, if you're not satisfied, then later on, when the telephone is working again, call the police if you like. Tell them this little story. By all means."

"Is she going to do that?"

"I don't know, and I don't care," he said again. "Now let's go and have a drink, eh?"

She made no demur, and they went out through the door. The guests were still sitting in the lounge, as they had been for ever and ever.

"I've ordered tea to be served to them," said Mr. Fernandez. "Also to the two ladies upstairs in their rooms."

As they passed the desk, Miss Peterson glanced sidelong at the young man, and he looked straight at her with an odd smile; a mocking smile, she thought.

"Is your clerk an American?" she asked Mr. Fernandez.

He was struggling to close the glass doors; he got them closed at last.

"I must tell you about that lad," he said. "Sit down, dear lady. What will you have to drink?"

"Nothing, thanks," she said. "Do you know, I think the wind is letting up."

He turned his head alertly; they both listened. The hollow spinning roar went on, and that savage pounding of the surf; but a high whistling note that was like the shriek of a Fury, was gone.

"I believe you're right—as always," he said, and offered her a cigarette; he bent to light it for her, his eyes smiled into hers. Very debonair, he was.

"Six months ago I was in Havana," he said. "That's my favorite place to take a holiday. You know Havana? Little Paris... Well, I was in a bar, having a drink, when somebody reached for the package of American cigarettes I'd laid down beside me. I caught hold of this fellow's wrist, and he laughed. He apologized. Said he was tired of the native cigarettes. There was something about him... He was down and out, all right, jacket all buttoned up, and no shirt, pair of tennis shoes all coming to pieces. But there was something... I offered him one of the cigarettes and a drink, and we got into a little conversation. He told me a wonderful tale, which I certainly didn't believe. But I took a liking to him. I thought he'd be an asset to my new hotel; and I brought him back with me."

"How about his passport?" asked Miss Peterson.

"You always come right to the point," he said. "I never saw such a woman. He had an American passport, all right. For Albert Jeffrey, aged forty. He said he'd come down with one of those tours, and that he'd lost his money and his luggage in a poker game."

"He's young-looking for forty..." she observed.

"He is, isn't he?" Mr. Fernandez agreed. "And he seems to have grown a little since he got his passport. Two inches, I'd say." He smiled. "Still, nobody bothered much about the passport, and I don't either. If there's something in his past, some little difficulty—very well. I was glad to give him a chance. It's worked out very well, too."

"I see..." said Miss Peterson, and smiled a little herself. She thought that Mr. Fernandez would know very well how to take the fullest advantage of any 'little difficulty' in an employee's past. But about taking a chance...? I don't know how far he'd go, she thought. Or how far he has gone.

Because, though she had not entirely believed Cecily's story, she did not believe his story, either. Something has happened, she thought. Something bad.

The wind was undoubtedly moderating; it came fitfully now; the rain would come rattling against the boards and then withdraw, and the heavy artillery of the sea would advance, shaking the earth.

"It may be just a lull," said Mr. Fernandez. "In that case of course, it will come back from the opposite quarter, and possibly worse than ever. But I don't think so. I think it's missed us this time. We—" He stopped. "What's that?" he asked.

It was music; somebody was playing the piano. He sprang to his feet and wrenched open the glass doors, and a Chopin mazurka came to them, loud, very brilliant.

"No—diga!" he said, appalled. "No! This is too much!"

He hastened along the passage to the lounge, and Miss Peterson went after him. There was Cecily at the piano, still in her cap and apron. The mazurka came to an end, and the Major clapped. But nobody else did. She began a waltz.

"Please stop her!" said Mr. Fernandez to Miss Peterson. "It's an outrage!"

"Don't you think that perhaps it might amuse the guests?" Miss Peterson asked.

"No! I don't! Did you ever see anything of the sort in a first-class hotel? And after what she told me... That girl is a devil! Please make her stop!"

Miss Peterson moved forward, and stopped, because above the virtuoso playing of the waltz she heard another sound; a hammering at the door.

"My God!" said Mr. Fernandez.

Miss Peterson went to the girl, and laid a hand on her shoulder; the music ceased and a little stream of fresh air blew in, exquisitely cool, as Mr. Fernandez opened the door to admit three men in rubber coats, two white men and a Negro. And two of them were police constables. Mr. Fernandez closed the door.

"Ah, Superintendent!" cried Mr. Fernandez. "Overtaken by the storm, eh? Well, it's an ill wind, eh...?"

He was too genial. And the man he was speaking to would notice that, Miss Peterson thought. He looked like a man who would notice everything; a slender, almost slight man with dark hair growing a little gray, a big bony nose, and small deep-set blue eyes.

"Quite!" he said civilly enough. "I'd like a word with you, if you please, Mr. Fernandez."

"This way, Superintendent. This way, please!"

Mr. Fernandez opened a door at the far side of the desk, he bowed the superintendent in before him, and the door closed.

"What's all this?" asked the Major. "Accident? Anything wrong?"

"I could not say, sah," answered the negro constable.

In her heart, Miss Peterson echoed the Major's question. What's all this? Something of grave importance to bring out a police superintendent in this weather... She started nervously at the sound of stirring chords on the piano; the opening of Weber's Invitation to the Waltz.

"Don't!" she said.

But Cecily went on until Miss Peterson took her right wrist and raised her hand from the keyboard. The superintendent had come out and stood beside them.

"Will you ladies be kind enough to step into the office?" he said.

Cecily rose, and they followed him into a small room, hot as an oven, furnished with a flat-topped desk, a swivel chair, a safe, a glass-fronted bookcase, and two fancy armchairs with green plush seats. Mr. Fernandez stood waiting to receive them.

"Miss Peterson," he said, "allow me to introduce Superintendent Losee. Superintendent, this is Miss Peterson, our new hostess, and a great acquisition to my little hotel."

He was overdoing it. He was too flowery, his smile was too brilliant.

"Thank you," said the superintendent, and glanced toward Cecily.

"This is Miss Wilmot, Superintendent," said Mr. Fernandez. "I'm afraid she's the only one who can give you any information about this—killing. She's the only one who seems to know anything about it."

Cecily made a faint sound like a gasp; Miss Peterson, too, was startled by this sudden attack, and by the venom in his tone.

"You're not obliged to answer any questions," said Losee to everyone in general. "It is my duty to warn you that anything you say may be written down and may be subsequently used in evidence against you. Will you be seated, ladies?"

They sat down in the green-seated armchairs, Losee took the swivel chair, Mr. Fernandez sat on the edge of the desk, smoking a cigarette. He looked very debonair in his white suit; he looked too debonair, even arrogant. And Losee and his constable looked very businesslike.

Well, something's happened, she thought. I wish they'd get on with it. She glanced about the little office, and on the top of the bookcase, directly behind the superintendent's head, she caught sight of a stuffed baby alligator dressed in a constable's uniform, helmet with chin-strap, belt and so on, leaning back a little to rest upon its varnished tail. She stared and stared at it, half hypnotized by this grotesquerie.

"We have received information," said Losee, in his level voice, "that a murder has been committed on these premises.

"May I ask—how you received information, Superintendent?" Mr. Fernandez asked.

"We'll go into that presently," said Losee. "It is the duty of anyone having any information to communicate the information to the police."

"Miss Wilmot is the only one with any information," said Mr. Fernandez.

Cecily looked up at him with her clear pale eyes, and he looked back at her; it was a long and deadly glance that they exchanged.

She took time to answer.

"I killed a man," said Cecily briefly.

"Cannon," said the-superintendent, and the constable brought out a notebook and a pencil.

"Do you wish to make a statement, Miss Wilmot?"

"I killed a man. I shot him—in self-defense."

"Where did this take place, Miss Wilmot?"

She was slow to answer that.

"In one of the rooms upstairs," she said at last. "I don't know which."

Mr. Fernandez looked at her quickly.

"On what floor, Miss Wilmot?" the superintendent asked.

"I'm not sure," she answered.

"You will save everyone—yourself included—considerable time and trouble, if you give me some idea—"

"I don't know," she said.

"Will you relate the circumstances which led up to this occurrence?"

"I was coming down from my room on the top floor," said Cecily. "I thought I'd stop and ask Miss Peterson if there were any orders for me. I was going along the hall—"

"On what floor is Miss Peterson's room?"

"The second."

"You were on the second floor, then?"

"I don't know. The lights were all out. I only had a flashlight. It might have been another floor."

"Very well. Continue, please."

"I saw an open door and a light inside. When I went there, a man dragged me inside. He attacked me: There was a gun lying on a table, and I picked it up and shot him."

"What did you do then?"

"I came downstairs and told Mr. Fernandez and Miss Peterson."

"How many flights of stairs did you go down?"

"I don't remember."

"What happened when you fired the shot?"

"The man fell down."

"What reason did you have for believing him dead?"

"He looked dead," said Cecily. "I spoke to him. I touched him. He was dead."

"Mr. Fernandez," said the superintendent, "can you supply Constable Cannon with a lantern? Thank you! We'll have to make a search of the premises."

"Some of the rooms are occupied," said Mr. Fernandez. "I hope you won't feel it necessary to disturb any of the guests, Superintendent."

"I hope not," said the superintendent. "Miss Wilmot, I'll ask you to come with us. You have a passkey, Mr. Fernandez?"

"Oh, yes. Certainly. But I'd better come too. I can tell you what rooms are occupied."

"Quite!" said the superintendent. "And Miss Peterson as well, if you please."

He looked at Miss Peterson; for the first time, their eyes met. And it seemed to her that his small, deep-set, unwinking eyes were a little like the alligator's.

THEY went in a procession past the desk, where Alfred Jeffrey still sat; Mr. Fernandez opened the door to the staircase and they began to mount, Constable Cannon going first with the lantern.

I don't like these stairs, Miss Peterson thought. The wind was still loud here; their shadows were monstrous on the stone walls. Nobody said a word. We're going with a lantern to look for a body, she thought. Why does he want me along? What does he think? What information has he got, and where did he get it from?

Mr. Fernandez opened the door on the first landing.

"In what part of the corridor was the room you entered, Miss Wilmot?" asked the superintendent.

"I don't remember," she said.

"Then we'll begin here," he said.

"Allow me!" said Mr. Fernandez, and approached the door facing the staircase; he opened it with a flourish, and Miss Peterson saw him smile, vividly.

The light of the lantern showed a neat and somewhat desolate little room. Losee entered, looked in the big wardrobe, he opened the door of the bathroom. They went on to the next room, and it was the same. They turned the corner into the main corridor.

"This," said Mr. Fernandez, "is Miss Peterson's room."

"Sorry, Miss Peterson," said Losee. But he looked in there, in her wardrobe, in her bathroom. He was going to look in every room; this was going on for ever and ever.

"This is Mrs. Barley's room," said Mr. Fernandez. "She may be in there. My housekeeper, you know."

He knocked, but there was no answer. He knocked again; then he unlocked the door. A candle burned in there, and by its light they could see Mrs. Barley lying on the bed, her face flushed, her gray hair disordered. She was snoring with her mouth open, and there was a bottle of gin on the floor beside her. It was a distressing spectacle, at which Miss Peterson felt ashamed and unhappy. But undaunted, the superintendent looked into her wardrobe and her closet.

They finished with that floor, and they returned to the staircase. As Mr. Fernandez opened the door, a gay faraway voice called from below. "Ahoy, there; me hearties!"

"Come up, Doctor!" said the superintendent; and they stood waiting while a man with a flashlight mounted quickly into the ring of lantern light. He was a tall man, very thin, long-legged, moving springily with bent knees; he had cropped white hair, and a brick-red face and a meaningless smile.

"Dr. Tinker," the superintendent announced, and Mr. Fernandez shook hands with him. "Glad to see you, Doctor," he said.

"Where's your corpse?" the doctor asked cheerfully. "Oh, still hunting? I had a time getting here. Trees down, wires down. We may have some more corpses. But the worst of it's over. Oh, yes. Glass is rising."

Mr. Fernandez opened the door on the second landing.

"My little suite is on this floor, Superintendent," he said. "Perhaps you'd like to look at that first?"

"We'll take the rooms in order, thank you," said the superintendent; and once more Mr. Fernandez unlocked and opened a door.

But this time it was different.

"My God!" cried Mr. Fernandez.

No one else made a sound. The light of a lantern showed a bald little man lying on his back, his eyes wide open, a pinched look about his hooked nose. He wore a singlet, and dirty white duck trousers; his heels were together and the toes of his heavy-soled shoes were turned out at right angles; his bare arms were straight at his sides.

"My—God!" said Mr. Fernandez again.

They all stood in a group in the doorway, Constable Cannon holding out the lantern so that they could see what was there.

"Can anybody identify this man?" asked the superintendent.

"That's the one!" said Cecily instantly. "That's the man I shot."

The doctor turned to look at her.

"Very well," said Losee. "Now then, kindly go down to the office and wait, Miss Wilmot. Miss Peterson and Mr. Fernandez too, if you please. Constable Cannon will accompany you."

The doctor moved forward, the superintendent took the lantern and closed the door, and the four others were left in darkness. But Mr. Fernandez and the constable both brought out flashlights; Cannon went first, holding his behind him, like a movie usher. After him came Cecily alone; as he illumined the steps, her foot in a gleaming high-heeled pump would appear. Mr. Fernandez took Miss Peterson by the arm, in a grip a little too tight. When I came down here before, she thought, that poor little bald man must have been lying there in that room, close to the staircase... What made those boys yell? The Devil, Fernandez said. Maybe...

They went past the desk where Alfred Jeffrey was still working; the people in the lounge were still there, waiting. They went into the stifling little office, and Cannon shut the door and stood before it. Now Mr. Fernandez was sitting in the swivel chair with the alligator constable behind him. The great wind still rushed at the walls.

"Couldn't we have some air?" Cecily asked.

"Presently," said Mr. Fernandez, without interest.

The door opened, and Losee and the constable entered. Mr. Fernandez rose. "Take this chair, Superintendent!"

"No. No... Don't move, Mr. Fernandez."

"I insist..."

So Losee sat again in the swivel chair, and Mr. Fernandez sat on the edge of the desk.

"Miss Wilmot," said the superintendent. "I'll ask you to repeat your account of the occurrence."

"You mean—all over again?"

"If you please."

"I was going along the hall—"

"Can you remember now which floor?"

"No," she said. "I'm sorry, but I can't. I saw a room with a light in it, and I thought it might be Miss Peterson's room—"

"You don't know which Miss Peterson's room is, Miss Wilmot?"

"Yes. Yes, I know. But the halls were dark. I was mixed up. I knocked, and a man pulled me in—"

"Will you describe the man?"

"It was that one. The one you saw."

"You're positive of that?"

"Yes," she said. "That was the one."

"Continue, please."

"He—put his arm around me. He wouldn't let me go. I struggled with him. Then I saw a little gun lying on a table, and I picked it up, and I shot him."

"Where was the man when you shot him?"

"Standing there."

"Then you had escaped from him?"

"For the moment. But he was between me and the door. He started to come at me again. I told him to stop. And when he kept on coming, I shot at him."

"What happened then, Miss Wilmot?"

"He fell."

"What was your aim when you fired this shot?"

"I didn't aim exactly. I just wanted to stop him."

"After the man fell, what did you do?"

"But I told you. I came down and told Mr. Fernandez and Miss Peterson."

"After how long an interval?"

"Oh, only a moment."

"What would you consider a moment?"

"I came down right away."

"Miss Wilmot, did you make a telephone call to the police station at two thirty-eight?"

"No," she said, staring at him. "No, I didn't."

"At two-thirty-eight, a call was received by Sergeant Brown. This call asked for police protection. According to the sergeant the call was made by a woman. 'Please send a policeman here. I'm afraid there's been a murder.'"

"I didn't say that. I didn't ring up anybody."

"This call was made just before the telephone service was disrupted. Approximately two hours before you notified Mr. Fernandez of this shooting."

"I didn't make the call."

"Were you aware of the presence of the deceased in the hotel before you confronted him in the room on the third floor?"

"No."

"Miss Wilmot," he said, "I'm going to ask Constable Cannon to read aloud to you the questions I have asked you, and the answers you have given. Go ahead, Cannon."

In a gentle sing-song voice Cannon read his notes, and Miss Peterson listened with uneasiness. The girl's lying, she thought. I can't tell which part of her story is a lie, but maybe the superintendent can.

"Miss Wilmot," he said, "do you wish to reconsider any of the answers you have given?"

"No, I don't!" she said.

"You wish it to go on record that you shot this man, and that he then fell to the ground?"

"Yes."

"Very well," he said. "I shall be obliged to place you under arrest, and subsequently to charge you with homicide. You may take with you a few articles—"

"Take...?" Cecily repeated. "But you're not—? I don't have to go—to prison, do I?"

"You are under arrest, Miss Wilmot, for shooting and killing un unknown person on these premises—"

The girl rose, her eyes fixed on his face.

"But it was in self-defense!" she said. "That's not murder."

"Miss Wilmot," said the superintendent, "that man was shot in the back."

THERE was a complete silence.

"Kindly get your things together," said the superintendent.

"May I go upstairs with her, Superintendent?" asked Miss Peterson.

"I'm sorry, but that's not possible. Constable Cannon will accompany Miss Wilmot to her door, and wait for her."

Miss Peterson rose and held out her hand to the girl.

"Take it easy!" she said.

But Cecily did not look like one who took anything easy. Her beautiful, narrow face had a look of proud scorn; the little frilled cap gave her, Miss Peterson thought, a Marie Antoinette air. Her fingers closed tight on Miss Peterson's.

"Thank you!" she said.

Cannon opened the door, she went out with her head high; and he followed her. Mr. Fernandez was lighting a cigarette.

"Superintendent," said Miss Peterson, sweet as honey, "doesn't the fact that the man was shot in the back invalidate her story completely?"

"Miss Peterson," he answered, "that young woman has stated three times that she killed this man."

"I thought the police were a little distrustful about confessions."

"Quite!" he said. "It's not at all unusual for people to confess to crimes they've nothing to do with. But this case has certain elements... This young woman has had ample opportunity to commit the crime, and she doesn't seem at all the hysterical type. On the contrary. She was playing the piano when I arrived here."

Miss Peterson believed in the maxim live and let live. But for her, that meant a little more than keeping herself alive—which she did very efficiently. She was often willing to go to considerable trouble in helping other people keep alive. She had a fairly good idea of what the prison in Riquezas would be like, and how it would be there for a young white girl.

And she had an extremely good idea, based upon experience, of what could be done in a place like Riquezas by influence. Not by bribery, but purely by prestige. Which Mr. Fernandez had. She looked at him, and he raised his eyebrows and shrugged his shoulders.

"Superintendent," she said, "if bail could be arranged...?"

"Out of the question, Miss Peterson, in a homicide case. Except in most unusual circumstances."

"But self-defense...?"

"Shooting a man in the back doesn't give the impression of self-defense."

"He may have whirled around. She may have lost her head a little—been panic-stricken."

"Miss Peterson," said the superintendent, "you're wasting your time. We received a telephone call asking for police protection, and informing us that a murder had been committed. As soon as the weather allowed, we came here; and we found that a murder had been committed. A young woman on the premises voluntarily confessed to the shooting."

"She's very young," said Miss Peterson.

"Her age, according to her passport, is twenty-one," said the superintendent.

Miss Peterson waited for a moment.

"Perhaps you'll be kind enough to give me the name of a good lawyer?" she asked. "I'd like to employ someone at once for Miss Wilmot."

"It's not within my province to recommend lawyers," said the superintendent. And in spite of his amiable and polite manner, she could see that he was growing more and more angry. "Our jail is completely modern, and very well administered," he said, and paused; and then said with suppressed fury, "The girl isn't going to a torture chamber, y'know."

No, I don't know, thought Miss Peterson. A wild gazelle in jail... But I'll have to keep quiet now. I'm irritating the superintendent. And Fernandez is not going to lift a finger to help the girl; that's plain enough.

"Shall I go into the lounge and see if everyone's all right?" she asked.

"I must ask you to remain here," said the superintendent. "When Cannon returns, I'd like a statement from you. I shall have to question everyone on the premises, naturally."

"Naturally," Mr. Fernandez repeated. "Well... You'll have my fullest co-operation, Superintendent." He smiled wryly. "A fine opening for my new hotel, eh? This fellow...off some ship, don't you think?"

"What ship do you suggest?" asked the superintendent.

"I hear that a schooner put in here," said Mr. Fernandez.

"I haven't enough facts yet," said Losee. "The very brief examination I made didn't yield anything much. No papers, nothing."

"My theory is that he's off some ship. He looks like a sailor, a deckhand. He came ashore, and when the storm broke, he wandered in here. He could have got in very easily without being noticed. There's a side entrance, for example... He gets in, he goes around to see what he can pick up."

"All your bedroom doors lock automatically?"

"Yes, that's a fact."

"How would it be possible for anyone to enter one of the rooms?"

"Locks can be picked, eh?"

"Now, about your staff, Mr. Fernandez. How many people do you employ?"

"God knows!" said Mr. Fernandez. "You know how it is here. I have on my pay roll a cook and a helper, three waiters, three chambermaids, five boys, one clerk. A skeleton staff until the season begins. But they have their relations and their friends hanging around."

"Your housekeeper, now. What can you tell me about her?"

"A fine woman," said Mr. Fernandez. "I had her in the old hotel, y'know. A very fine woman, capable, trustworthy. An Englishwoman. The only thing is, she has this little weakness—You understand."

"You mean she drinks?"

"From time to time. But it doesn't interfere with her work. Only from time to time, and only at night. This storm would get on her nerves."

"Quite. This Miss Wilmot, now?"

"Yes?"

"Did she have any love affair, to your knowledge?"

"She didn't. And if she did, it would have been to my knowledge. I assure you of that. I know very well what goes on in my hotel. No love affairs, no letters. Not one single letter since she came here."

"What do you know about her antecedents?"

"Nothing. Nothing at all. She came here on a cruise ship. She came to my hotel, and she asked me for a job. Well, I thought, why not? I thought, here's a girl of education, good manners, very musical. Why not? She had a passport; everything in order. And her conduct's been above reproach, except—"

"Except?" said the superintendent.

"She's a little hot-tempered. High-spirited."

"Any instances of violence?"

"Oh, no!" said Mr. Fernandez. "A little hot-tempered, that's all. Impulsive. She's inclined to act without thinking." He was doing his best to close the prison gates upon the wild gazelle, and doing it deliberately.

"Did she ever, to your knowledge, possess or carry any weapons, Mr. Fernandez?"

Mr. Fernandez knocked the ash off his cigarette into an ashtray in the form of a scarlet lobster.

"No..." he said, "No." At that moment there was a knock on the door, and Constable Cannon appeared carrying a small suitcase. Cecily stood behind him. She had taken off the cap and apron, but she still wore the black dress and shoes and stockings, and she had a wide black straw hat on the back of her head. She had put on more lipstick; she looked superb, pale, beautiful and fierce.

"Have you a room that's not being used, Mr. Fernandez?" asked the superintendent. "The writing-room? Very well. Tell Humber to remain in the writing-room with Miss Wilmot, Cannon. I'll need you here."

"Au revoir, Cecily!" said Miss Peterson. "And remember—take it easy."

"Thank you..." said Cecily, and her clear eyes rested upon Miss Peterson's face for a moment.

That kid is frightened, thought Miss Peterson. It's a damn shame to let her go to jail, even if she gets out in a few days, even if she gets out tomorrow, it's too much.