RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

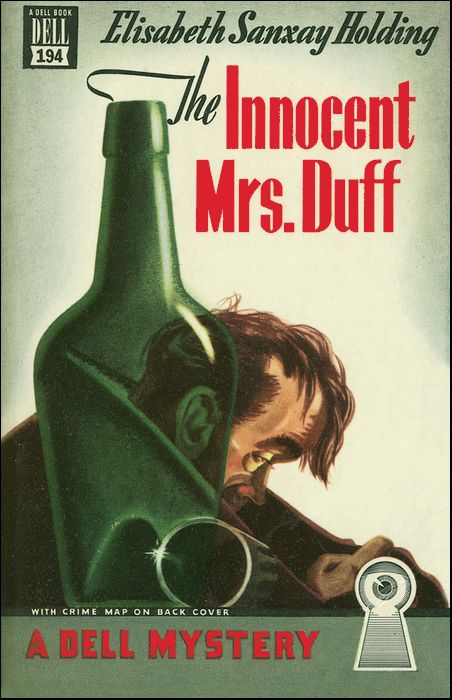

"The Innocent Mrs. Duff," Dell, 1946

"The Innocent Mrs. Duff," Simon & Schuster, New York, 1946

"The Innocent Mrs. Duff" is a psychological crime novel that explores the unraveling mind of Jacob Duff, an alcoholic widower who remarries a much younger woman. His paranoia, resentment, and self-destructive tendencies lead him into a spiral of delusion, manipulation, and ultimately murder...

"MY GOD!" Jacob Duff said to himself, standing stripped before the bathroom mirror. "I'm putting on weight!"

He was a big man, and very well-built, with broad shoulders and narrow flanks; it shocked him to study that thickening around his middle. And his ruddy, handsome face showed a sagging about the jowls. My God! he thought. I'm only forty-two. There shouldn't be anything like this...

Reggie began singing in her bedroom. Oh, shut up! he cried in his heart. You can't carry a tune. You know that; you know how it gets on my nerves, and still you keep on. Shut up!

He opened the door into his own bedroom and closed it behind him with a slam. That stopped her. But she'll do it again, he thought. There's nothing, absolutely nothing I ask her not to do that she doesn't keep on doing.

He began to dress, and this morning he admitted what for some time he had been trying to ignore: that the waistband of his trousers was tighter, was too tight; his back bulged a little between the shoulders. This made him miserable. It's her fault, he thought. She doesn't have the right sort of meals. As far as that goes, she doesn't have anything right. We've been married nearly a year, and she hasn't learned one damn thing. She never will, either. She doesn't even try.

He heard her come out of her room into the hall. She knocked at his door.

"Ready, Jake?"

"Not yet," he answered. "You go ahead."

He knew exactly how it would be. She would go running down the stairs and into the dining-room, and she would say "hello" to the housemaid. That was another thing he had asked her, again and again, not to do, but she kept right on, saying hello to everyone. To the chauffeur, to the cook, to the doctor, to anyone he was Fool enough to invite into his house. Oh, hello!

I'm ashamed of her, he thought. I admit it. That time I brought Copeley in for a drink, she said "hello, hon", to me. I caught him grinning. Everybody—servants, everybody laughing at her behind her back. And at me, for marrying her.

He hated the thought of going downstairs. I never have any appetite for breakfast any more, he thought. I used to look forward to breakfast, when Helen was alive. Good God! After being married to a girl like Helen for four years, how could I have married Regina Riordan? The name ought to have been enough for me. Reggie. A photographer's model.

He had to go downstairs. She was sitting at the table, and she was wearing another of those negligees she fancied: blue satin, with a little scalloped cape.

"Oh, hello, Jake!" she said, with that dazzling smile. A model's smile, he thought.

"Morning," he answered. "Reggie, I've asked you time after time if you'd kindly get dressed for breakfast. If you can't make the effort, then have your breakfast in your room."

"I know," she said, anxiously. "I've been trying to get some nice little porch dresses, but I honestly haven't seen anything worth buying."

"Porch dresses? What are they?"

"Oh, little ginghams, you know. Little checked dresses, or percales, things like that."

He knew they would be wrong. Helen had never had things like that.

"Why can't you wear your ordinary clothes?" he asked.

"Oh, I got it so drilled into me not to sit around in my good clothes," she explained. "At the studio we always—"

"Hush!" he said, as the maid came in through the swing door.

"The cook was able to get some bacon yesterday, Jake. You like bacon and eggs—"

"None for me, thanks. I'm going on a diet."

"Oh, Jake! Did the doctor say—?"

"Yes," he said, to keep her quiet. "Only black coffee and orange juice this morning. Where's Jay?"

"Oh, Miss Castle said he got something in his eye. They'll be right down. Honestly, Jake, I hate to sit here eating when you're not taking a thing."

"Thanks," he said.

Anyone else would see that I don't feel like talking, he thought. But not Reggie.

"Aunt Lou asked me to stop in and see her this morning," she went on. "I thought I'd take Jay."

"You'd better leave Jay to Miss Castle. That's what she's here for."

"I know. But—"

"I'd very much rather you didn't drag the child around with you."

"Well, I always consult Miss Castle, Jake."

I'd rather you never had anything to do with my son, he thought. I don't like him to go anywhere with you. I don't like him to see you here in that tawdry thing. He glanced at her across the table. She's beautiful, he thought, with distaste.

She looked taller than she was, being so slight. Her face was thin, with faint hollows under the high cheekbones, but heaven knew she was healthy enough, never sick, never tired. Like a peasant. Her eyes were dark-blue, with thick black lashes, her hair was black, her skin had a delicate rosy glow.

Jacob Duff, junior, came clattering down the stairs and into the dining-room, a thin little boy of seven, with neat fair hair and a debonair manner.

"Hello, Daddy!" he said. "Hello, Reggie!"

"I've told you not to say hello," said Duff, angrily.

"Well, good-morning," said Jay, without interest, and drew back Miss Castle's chair for her.

"Good-morning!" she said, with a smile and a slight inclination of the head.

She was an Englishwoman of thirty-five or so, handsome in a calm and disinterested fashion. She wore no make-up but a little powder; her thick light hair was cut and waved in unbecoming scallops; her white blouse with an artless little round collar did not suit her strong-boned face. But she's not interested in being 'alluring' and 'glamorous'—and cheap, Duff thought. If she chose to use lipstick and all the rest of it, she'd be a damn sight better looking than Reggie. Better figure, too. More womanly.

"I hear Jay's going to visit his auntie this morning," she said.

"I don't want to go!" said Jay, loudly.

"Don't shout like that!" said Duff. "And don't say things like that, either."

"Well..." said Jay, sulkily, and he pronounced it "wull".

"None of that," said Duff. "None of your 'wells', when you're told to do something."

"Told to do what?" asked Jay.

"Jay!" said Miss Castle, in mild rebuke.

"Well, he didn't tell me to do anything," said Jay. "I just said I didn't want to go and see Aunt Lou. Is that anything so bad?"

"Leave the table, sir!" said Duff.

"All right—sir!" said Jay, and jumped up nimbly.

"Go up to your room and stay there until you've learned some manners," said Duff.

"Learn 'em out of a book?" asked Jay; then, at the sight of his father's face, he giggled and ran scampering up the stairs.

Miss Castle went on quietly eating her breakfast, but not Reggie.

"It's just one of his wild fits," she said. "He's such a high-strung little fellow."

"Thanks," said Duff. "Thanks for explaining him to me."

"Well, I didn't mean it like that, Jake. I just meant he doesn't really mean to be rude. He's always as good as gold with Aunt Lou."

"Yes..." said Duff. "If you ladies will excuse me, I'll just glance at the news."

He was glad to put up the newspaper, to block out Reggie's face. Aunt Lou! he thought. The idea of a girl like Reggie being in a position to call her that. It's my fault. I realize that. But what was I thinking of, to do a thing like that?

His aunt, Louisa Albany, was a figure of overpowering importance in his life, and always had been. He was her heir; he would someday inherit a very nice little fortune from her, but her importance, to him, was not derived from that. It was her personality, her character, her tradition. His respect and admiration for her were beyond measure.

She could have stopped this, he thought. When I first brought Reggie to see her, if she'd said one word... Of course, she'd never met anyone like Reggie; you couldn't expect her to understand that type. She simply thought I'd be happier if I married again. She was simply thinking of my welfare.

But if she'd only realize now... I don't like to say anything out-right to her, but if she'd only see for herself. She knows me; she knows what my life with Helen was like. I don't know how she can help seeing. It's beginning to affect my health. I'm sleeping badly—and putting on weight like this isn't healthy.

"Couldn't you have one little corn muffin, Jake?" asked Reggie. "They're as light as feathers."

"No, thanks. To tell you the truth, I don't think all this heavy, starchy food is a good thing for anyone."

"I can't eat them," said Miss Castle. "I think your hot breads are delicious, but if I start the day with them, I'm quite dull all morning."

Duff glanced at her, and their eyes met for a moment. Then she smiled and looked away, but Duff had already got her message. She understands! he thought, with a sort of wonder.

"Look!" said Reggie. "I'll just run up and put on a dress and drive to the station with you, Jake."

"I'm sorry, Reggie, but I've got to pick up three or four men this morning."

"Oh, well...!" she said. "Then how about Jay and I meeting you for tea somewhere, after we leave Aunt Lou's?"

"Jay is to stay in his room all day," said Duff.

"Oh, Jake, honestly—!"

"My dear girl, I happen to be the child's father. I understand him better than you ever could. I'm not going to have him behaving like a common little brat."

"But, honestly, Jake, he didn't do anything—"

"If Miss Castle thinks I'm being harsh or unreasonable—" he said, and again he glanced at Miss Castle, and again she smiled at him.

"Suppose we wait and see what Jay has to say for himself, later on?" she suggested. "I'll go up and have a talk with him presently."

"Very good idea," said Duff.

We speak the same language, he thought. God, what a relief. She's got some sense and breeding and dignity. She's a handsome woman, too; knows how to carry herself. Reggie looks like a rag-bag in that thing.

He pushed back his chair and rose, and now was the time for him to kiss Reggie. He did not want to. It's a silly, meaningless habit, he thought.

"Well, au revoir!" he said.

"Hi! Wait!" cried Reggie, and jumping up, she ran to him. She put her hand on his arm and looked up into his face with her wide, gay, model's smile.

"You forgot to kiss me good-bye!" she said. "I guess the honeymoon's over."

And you think that's a joke, do you? thought Duff.

THE car was waiting; Nolan, the chauffeur, opened the door for him.

"Good-morning, sir," he said.

"Good-morning," said Duff. "Well stop for Mr. Vermilyea, that's all."

"Yes, sir," said Nolan.

Duff lit a cigarette and leaned back. This car-pool business was a nuisance, he thought. And Johnny Vermilyea's a nuisance, too. If he weren't so lazy, he'd walk to the station.

The three other men who had gone into the pool with him were pretty well eliminated, now that he had begun taking the nine-twenty. They had to go earlier. Only Vermilyea didn't care what train he got. Any time that suits you, old man, he said. Any time, any time. He was sauntering across the driveway in front of his big house, very dapper in his dark suit, which was, according to Duff's standards, too snugly fitting to his muscular body. With his red face, his big nose, his little bright eyes, he looked like Mister Punch.

"Hello, hello, hello" he said. "Here we are." He got into the car. "Wonderful weather for April."

"Yes," said Duff, without enthusiasm. "But this commuting business gets me down. I'm not used to it. To tell you the truth, I don't like suburban life. Born and brought up in New York."

"I couldn't live in the city," said Vermilyea, earnestly.

He was certainly close to forty and he lived, Duff thought, a ridiculous life, with his aged parents, in that big old house. His father had retired at seventy, and Vermilyea had become president of the Vermilyea Steamship Company. I'm more or less a figurehead, he would tell anyone, candidly. I've got some first-rate fellows there who do all the work.

Three nights a week he served as an orderly in the Vandenbrinck Hospital, and his leisure time was chiefly given up to Drives, drives for the Red Cross, the Community Chest, and so on; he was forever appearing at your house, trying to collect money. Duff found him boring, but after all he was a Vermilyea of Vandenbrinck; he had gone to a very good prep school, and, though not to Harvard, to Princeton.

This was the wrong sort of suburb to choose. Duff thought. I should have gone to one of those flashy new places—where Reggie might have fitted in. But I was thinking of Jay. I was thinking of Jay when I married her, too. I thought she'd be good for him, make a home. She's ruining the boy. She's making life hell for me. I'm putting on weight...

I want to get weighed, he thought. I want to see... He answered Vermilyea absently, while he tried to think where he had seen scales. At the club, of course, but he had not been there for months; people would ask him questions, make jokes about his marriage. In drug-stores? he thought.

The car stopped in the circular drive behind the railroad station.

"Five-twenty, sir?" Nolan asked.

"Yes," said Duff, and crossed the platform with Vermilyea.

"Dam good-looking fellow," Vermilyea observed.

"Who?" asked Duff.

"That chauffeur of yours. Mrs. Laird was speaking about him the other day."

"Speaking about Nolan?" said Duff.

"Yes," said Vermilyea. "She was saying it was a pity she couldn't get him for this play she's putting on for Overseas Clothing."

"Can't she find anything better to gossip about than other people's servants?" Duff demanded.

"Wasn't gossiping, old man. Just—well, here we are! Here we are!"

They got into the club car, and there were a couple of fellows Vermilyea knew. They wanted to play gin rummy.

"Sorry," said Duff, "but you'll have to count me out. I've got a head this morning."

"Oh! Big night?" one of the men asked.

"Could be," said Duff.

A big night, he thought. That's a good one. Directly after dinner he had gone into his study; he had sat there all alone all evening, reading, or trying to read, his late uncle Fred Albany's book, Big Game and Small. He had two or three whiskies, or maybe four, simply in order to get sleepy. He did that every evening now; he had to do it, or he could not sleep.

But it's not a good idea, he thought. I mean to say, drinking alone. Not good for morale. Not good for your health. I don't feel well, and that's a fact. But what the hell can I do in the evenings? I can't sit there talking to Reggie; there's nothing to talk to her about. Nobody ever comes to see us; there's no place to go. If I could take a room in a hotel in town...

Duff and Vermilyea and another man were all going downtown; they shared a taxi. Once I've started working, I'll feel better, Duff thought. But, unfortunately, there was little or no work for him to do that morning. He was the junior partner, as his father had been, in the firm of Hanbury, Martin and Duff, Surgical and Dental Appliances; they were working almost entirely on Government contracts now, and Duff left all that to Hanbury. I don't like all this red tape, he said. I don't like all these regulations, all this red tape.

There's no need for my coming in to the office five days a week, he thought, and I wouldn't do it, except for the sake of getting out of that house. But if I stay home, there's Reggie, trailing around in a wrapper, and the servants doing just as they damn please. No order, no system, no peace and quiet. When Helen was alive, everything went like clockwork. If I called up and said I'd like to bring someone home to dinner, I could absolutely count on everything being exactly right. But now...!

They had taken in so many new people that his secretary had to work in his private office half the time. She began to type, and the noise was exasperating.

"I'm going to step out for a cup of coffee. Miss Fuller," he said. "Back in a few moments."

He wanted to find a pair of scales. Funny, he thought, that you always say a 'pair' of scales. You couldn't ask anybody where to find scales; simply calling attention to the fact that you'd gained a few pounds. So he went into the drug-store in the lobby of the building. There were scales there, two kinds, the old-fashioned reliable kind with weights on a bar, and the other kind, that gave your weight printed on a ticket, in privacy. He chose the privacy. He put in a penny, and out came the little ticket.

"My God!" he cried to himself. "It's not possible." He stepped upon the trembling platform again and put in another penny; out came another ticket with the same figure on it.

No matter who might be watching him, he had to try the honest old-fashioned scales. He set the weights for what he had last weighed; five pounds more, ten pounds more, fourteen.

Fourteen pounds more than he had ever weighed in his life. It made him feel actually sick. I need a drink, he thought. Then I'm going to turn over a new leaf. Diet, exercise, and so on.

There was a bar down the street where he sometimes went after five for a cocktail. He had never entered it at an earlier hour; he could not remember ever having taken a drink at eleven o'clock in the morning, and he was ashamed to be seen going in there.

But there were plenty of men at the bar, and they looked all right, prosperous-looking fellows, well-dressed; they seemed perfectly matter-of-fact about an eleven o'clock drink. He ordered a straight rye, and drank it standing at the bar. It wasn't quite enough, and he ordered a second.

That turned out to be just what he needed. Sitting on the stool, in the dim, quiet bar, his mind began to work, quickly and clearly. This weight, he thought; I can get rid of that, easily enough. Go to one of these gyms, sweat it off in a couple of weeks. No. That's not what's worrying me. It's the whole setup. Reggie. I don't see why I should sacrifice my whole life for her. She married me for money and social position; nothing else. For all I know—

A thought came to him that was like a flash of light. Dam good-looking fellow, Vermilyea had said. Mrs. Laird had talked about Nolan's good looks. Had everybody in the neighborhood been talking about his handsome chauffeur?

I'll just put on a dress and drive down to the station with you, Reggie had said. Then she would have driven home alone with Nolan. And she had done that, a dozen, a score of times. He began to remember other things now. The way she said 'hello' to Nolan, with her wide, dazzling, model's smile.

I've been sleeping in that other room for nearly two months now, he thought, and she hasn't said a word. That simply isn't natural— unless there's somebody else. That would be absolutely typical of her, to disgrace me—with a chauffeur.

But she's not a bad girl, he thought.

On the contrary, he had found her altogether too good, too innocent; it had been like marrying a schoolgirl. He remembered the miserable embarrassments of their honeymoon. When the bellboy had opened the door of the hotel suite in Montreal, she had given a squeal of delight. Oh, Jake! Isn't this grand?

Helen had felt as he did; they had both determined that no one should know they were a honeymoon couple, and they had gone to Havana, and nobody had known. But not Reggie. Reggie had told people. She's absolutely insensitive, he thought. She doesn't realize that she's killed all the love I ever had for her. But she's not a bad girl.

Not yet. At least, I don't think so. But she could behave in a way to make a hell of a scandal with that fellow Nolan.

Anyhow, I can't stand any more of this, and I'm going to tell Aunt Lou so, frankly. I'll provide for Reggie, of course. Generously. I'm not interested in a divorce, either. I simply want to get away from that setup. I cannot stand it any longer.

WHEN her husband died, Mrs. Albany had sold his house on Ninth Street, and she lived now in an apartment-hotel not far from Washington Square. She lived, as always, with old-fashioned stateliness, combined with her own particular dash. When Duff rang the bell of her suite, the door was opened by a colored maid in a trim uniform, who led him into the sitting-room filled with the hideous Albany furniture, pictures and ornaments.

"I'll see if Mrs. Albany is at home, sir," said the maid, and withdrew.

It made no difference that he was Mrs. Albany's nephew and heir.

He would have to wait, like anyone else, and if Mrs. Albany were taking a nap, or if she were engaged with the manicurist, or if she were not disposed to receive guests, he would be dismissed, like anyone else. I have no regular hours At Home, in war time, she had told her nephew. If people want to see me, they must telephone ahead, or take their chance.

Rose, the maid, came back.

"Mrs. Albany is At Home, sir," she said, and went away, without a smile.

Louisa Albany came in promptly, a tall and very thin woman, with frizzy hair dyed a strange, pale red; she had rouge on her hollow cheeks and on her thin lips; she wore a blue satin blouse with a high collar, and a short black skirt. You could say, with truth, that her face in profile was like a camel's; you could say she was a hag. But it was none the less undeniable that she had an air; she had style, even elegance.

"Well, Jacob?" she said, in her clear, superior voice. "Sit down! I haven't seen you for some time."

"I've been rather busy. How are you keeping. Aunt Lou?"

"Very well indeed, thank you. You're putting on weight, Jacob."

His face grew hot.

"I'll soon get rid of it," he said. "I've started on a diet."

"Then I shan't offer you a cocktail," she said.

"That won't do me any harm."

"It will," said she. "You can't touch alcohol when you're reducing. Your Uncle Fred often had to go without a drink for weeks, when his weight got up. He had a perfect horror of getting fat."

"Naturally," said Duff. "Look here. Aunt Lou, I'd really like a cocktail. I'm a bit upset."

She looked at him for a moment.

"Then you shall have one," she said. "I'll make it myself."

He watched her as she crossed the room to the kitchenette across the hall.

"Ice, Rose," she said.

"Yes, madam," said Rose, who never smiled.

There was a strange, and, to Duff, an irritating harmony between Mrs. Albany and Rose. They worked together now like two professional bartenders.

"Martinis," said Mrs. Albany.

On a shelf there was a fine array of bottles, with jiggers of two sizes, swizzle sticks, glass mixers. Rose washed a lemon, and cut curls of peel; Mrs. Albany moved about neatly. Rose put a glass mixer and two glasses on a tray and brought it into the sitting-room.

"What are you upset about, Jacob?" Mrs. Albany asked, when they were alone.

"I simply can't go on like this," he said. "My life is hell."

She took a sip of her cocktail. "Light a cigarette for me, Jacob," she said. "Thank you. Is this all about Reggie?"

"Yes. I don't know how to make you understand. You're absolutely blind about that girl."

"No, I'm not," said Mrs. Albany, simply. "She has her faults. I was telling her today—you knew they came in to lunch?"

"They?"

"Yes. Reggie and Jay."

"Jay?"

"Don't shout so, Jacob."

"I said the child was to stay in his room—"

"Well, probably your Miss Castle didn't think that was a good idea."

"When I give an order, in my own house—"

"Pooh!" said Mrs. Albany. "That's no way to talk. No... I was speaking to Reggie about her housekeeping. I told her she'd better go and take one of those courses. I told her about this finishing-school—junior college, they call it now—where she could learn how to do things properly."

"It's a lot more serious than a matter of housekeeping. She doesn't care a damn for me."

"Yes, she does. She's very fond of you, and very anxious to make you happy."

He had finished his cocktail. He set the empty glass on the table and glanced at Mrs. Albany, but she took no notice.

"Mind if I help myself?" he asked. "They're excellent. Excellent. Aunt Lou, I'll tell you something that may make you realize. For nearly two months we've—" He hesitated. "We've been occupying separate rooms."

"Reggie didn't mention that. What was the quarrel about, Jacob?"

"There wasn't any quarrel. One night I didn't feel at all well, and I went to sleep in one of the guest rooms. And the next night, it was simply taken for granted. Bed turned down in there, my pajamas laid out. And it's been that way ever since. Reggie's never said a word."

"It's for you to speak of it" said Mrs. Albany, severely. "That's no way to treat your wife."

"No..." he said. "There's nothing left of our marriage. No companionship, no home life, no social life, nothing."

"Jacob," said Mrs. Albany, "Reggie is young, very young, and she has not had advantages. But she's an affectionate, loyal, good girl. She's devoted to little Jay. If you'll give her the help and guidance it's your duty to give her, she'll make you a splendid wife."

"Not she! She won't do a single thing I ask her. She doesn't learn anything."

"That's unjust. She's learned to dress in very good taste."

"That's because you buy her clothes for her."

"No. She gets things for herself now. And she's always reading little articles, about etiquette, and so on, and keeping up with the new books. And she works faithfully as a Nurse's Aid in the hospital."

"Mind if I finish up the cocktails?"

"Yes, I do mind," said Mrs. Albany. "I only made two each, and I want that for myself."

"Then d'you mind if I get a drink from the kitchen?"

"Yes, I do. You've had plenty."

"I'm upset!" he cried. "The whole thing is hell. And when I think of Helen—"

"You never cared so very much for Helen."

"I respected her."

"She saw to that," said Mrs. Albany. "Helen knew how to hold her own. And Reggie doesn't."

"Look here, Aunt Lou, I really need another drink."

"Don't ever let me hear you say you 'need' a drink."

"Well, I do!" he said. "I can't go on, with things as they are. I'll have to get away, take a room in town—"

"Out of the question!" said Mrs. Albany. "You can't desert that poor girl for no reason at all."

"All right!" he said, rising. "Suppose I told you I'd heard some very unpleasant talk about Reggie?"

"What sort of talk?"

"She's pretty free and easy with Nolan—"

"Jacob," said Mrs. Albany, "you ought to be ashamed of yourself for listening to gossip about your wife. What's more, you know as well as I do that there's not a word of truth in it. You know Reggie's absolutely incapable of anything of that sort."

"Good God!" he cried. "You have no sympathy for me whatever, no understanding. Reggie is 'incapable' of anything wrong, but I'm —I don't know what. A monster. I never knew you to be so utterly unjust."

That disturbed her.

"I don't mean to be so," she said. "I know Reggie has a great deal to learn, "and I know you're not happy, Jacob. But—to be frank, Jacob— I don't think you ever could be happily married."

"What? Why not—if I found the right woman?"

"You don't know how to be married, Jacob. You don't like it. You're not domestic. A man's man, as they say."

"And what about Uncle Fred? He didn't spend—didn't want to spend four months of the year at home."

"He wanted me with him, wherever he went," said Mrs. Albany. "He was—very companionable."

"And I'm not?"

"I don't mean to be carping and fault-finding, Jacob," she said, and she was a little anxious now. "But I'm sure that, if you'll try, you can make this marriage a success. Reggie does everything she can to please you—"

"That's where you're wrong," he said.

"No..." she said. "Jacob, give her a chance. To- to make her happy—"

"Good God!" he cried. "When you think of what I've given that girl—!"

"Jacob," said Mrs. Albany, "that's sheer vulgarity."

Their eyes met.

"I think I'd better be going," he said, coldly.

"Perhaps..." said Mrs. Albany, with a sigh.

When he went out into the little hall, she followed him.

"I dare say it's hard," she said. "But now that you're getting older, it will be easier to settle down. As time goes on." She hit his shoulder with her bony hand. "Think of Jay," she said. "Try to make the best of things, Jacob."

He stood waiting for the elevator, sunk in a bleak depression. If she'd stood by me, he thought, I might have been able to stand it, to go on. But she's hypnotized by Reggie. Now I can't stand it. Now I can't go on.

HE stopped in at a bar and got a drink; only one—that was all he wanted.

The bartender set a plate of cheese crackers and pretzels before him.

"Not for me, thanks," said Duff. "I'm on a diet."

"Well, there's plenty of us on diets now," said the bartender, somberly, "so many things you can't get."

"Compared with the rest of the world," said Duff, "we're damn lucky. The thing is, some people say alcohol puts weight on you. What do you think?"

"Well, it does with some," said the bartender. "With others it don't. It all depends on what constitution you got."

"That's probably it," said Duff.

He felt somehow reassured by this little talk. I know people who drink, he thought, drink excessively, and they're thin as rails. He knew he was going to need a few drinks at bedtime, to get some sleep, and he did not want to think that that might undo the benefits of the day's dieting. Black coffee and orange juice for breakfast, a lamb chop and a salad for lunch—nothing else. It won't take long, at this rate, he thought. And after all, fourteen pounds isn't so much, on a big frame.

He missed the five-twenty. Won't hurt Nolan to wait a while, he thought. God knows he has little enough to do these days, with no gas to run the cars. I don't know about Nolan and all that gossip...

He sat in the smoker, in a front seat, hoping not to see anyone he knew. He wanted to think about Nolan. Where did I first hear that gossip about Nolan and Reggie? he thought. But he could not remember. It's probably all over the place, he thought. You can't deny that Aunt Lou's a woman of the world. She travelled everywhere with Uncle Fred, met everybody. But she doesn't know anything about a girl like Reggie. Never met that type.

Well, he thought, with a sigh, there's nothing to do but wait. In the course of time she's absolutely certain to do something that will make Aunt Lou realize... Or she'll get sick of living like this, and she'll leave me. That would be the perfect solution.

The sun was low when the train stopped at Vandenbrinck; the river was pearly grey under a sky without color. The whole scene had, for him, a desolate look. I've had some of my happiest hours alone, he thought. In the North Woods, the Adirondacks, sailing. It's either that, or the big cities. But this suburban setup makes me sick.

The car was waiting, and Reggie was in it. Her beauty surprised him, for when he thought of her, he forgot that: the delicate loveliness of her thin young face, the grace and fineness of her body. She looked entirely right, too, in a navy-blue linen dress, her shining black hair brushed back from her face. She looked like a quiet, well-bred young girl. But who knew better than he that she was not?

Nolan was standing in the road, smoking; he threw away his cigarette and hastened forward to open the door of the car. And for the first time Duff really looked at him. Why, he's like a damn movie actor! he thought, outraged. Black, wavy hair, Nolan had, that sprang up from the temples, fine black brows over deep-blue eyes; he was of medium height, and slender, but in his very upright carriage, the set of his head, there was a vitality a little aggressive.

"Hello, Jake!" said Reggie.

He gave her something like a smile and got in beside her.

"The chairs have come!" she said.

"What chairs?"

"Why, don't you remember, Jake? You said I could order those dining-room chairs, over four months ago?"

"That's nice," he said.

"I went in to lunch with Aunt Lou, Jake, and she had an awfully good idea. About me taking a Homemaker's Course. I went to the Haverdean Junior College about it. Of course, it's sort of late in the year, but Mrs. Haverdean said that if I started right away, I'd get a good two months, and I could take some private lessons. And next year I could start when the school opens."

"Do you want to do that?" he asked.

"I'm crazy to."

"You would be," he said.

"How do you mean, Jake?" she asked.

"I think you would be crazy, to go to a school like that—with young girls."

"Well, I'm not so terribly old, Jake. Twenty-one."

"It's not that."

"But then what, Jake? You mean because I'm married?"

"That's one reason."

"But Mrs. Haverdean says they've got other married girls—"

"Please don't talk about 'married girls'. I'd rather not go on with this. If you can't see for yourself how unsuitable, how—damn ridiculous it would be for you to go Haverdean—"

"You mean, about them being society girls?" she asked. "Well, Aunt Lou said that would be all right, Jake. She said I'd make some nice friends."

"Do you want to have schoolgirls for friends?" he asked.

"Well..." she said, with a doubtful smile.

They were both silent then. It's all very well for Aunt Lou to say that I didn't love Helen, he thought. I wasn't infatuated with her; I admit that. But we got on together. We spoke the same language. Helen was a woman, not an ignorant, childish—ninny.

They had turned into the driveway: the burgeoning trees threw long shadows on the lawn, the windows had a fiery dazzle from the setting sun. It seemed to Duff that the place had a strangely deserted look. Not like a home at all, he thought. The housemaid opened the door, and they went in, to a blank silence. Never any stir here, no preparations for guests, no telephone calls.

"Where's Jay?" he asked.

"Miss Castle sent him to bed early, because he was rude to you at breakfast."

They went up the stairs together, and, without a word, separated, going to their separate rooms. If she was human. Duff thought, if she was a woman, shed ask me to come back to her. But she never says one word. Good God, what is she?

There was nearly an hour to fill before dinner. Duff washed, and went quickly downstairs. He was pleased to find Miss Castle in the sitting-room, and he thought she was pleased to see him. She-looked very nice, he thought, in a long-sleeved white blouse, her hair so neat. A handsome woman; a real woman.

"I thought a cocktail wouldn't come amiss," he said. "Will you join me, Miss Castle?"

"Oh, thank you!" she said.

He rang for Mary, and told her to bring ice cubes, gin, French vermouth, and bitters.

"And be as quick as you can," he said.

That needed explaining to Miss Castle.

"When I do take a cocktail," he said, "I like it fifteen or twenty minutes before dinner. Not right on top of the meal."

"I'm sure that's more artistic," she said. "Do you know, when I left England, six years ago, I'd never had a cocktail? Sherry, sometimes, before dinner, and once in a great while, a brandy afterward."

"If you'd rather have sherry—?"

"Oh, thank you, but I quite enjoy a cocktail now and then. If one's at all depressed or out of sorts..."

He did not like to think of Miss Castle being depressed; he wanted her to be serene and happy under his roof.

"I hope Jay doesn't give you too much trouble," he said.

"Oh, no! He's a very interesting child. But there is one thing... I don't think Nolan is a good influence, Mr. Duff."

"Nolan?" he said, startled. "Does the boy see much of Nolan?"

"He's always running off to the garage. He's quite devoted to Nolan. Of course, it's easy to understand. Nolan tells him these stories of his life in the Marines."

"I didn't know he'd been a Marine."

"Oh, yes! He was two years in the Pacific islands."

The clock on the mantel struck half past six; Duff frowned and rang again for the housemaid.

"What's your opinion of Nolan, Miss Castle?" he asked.

"Not very high, I'm afraid."

"I'd like very much to know just why."

"It's difficult to put these things into words..." she said. "I don't think Nolan is—trustworthy."

"Have you had any trouble with him? Has he been impertinent to you?"

"Oh, no, never!" she said. "I shouldn't quite call Nolan impertinent. It's simply that he's so—" She hesitated. "So extremely independent," she said. "Or perhaps cynical would be a better word."

"Have you forbidden Jay to go to the garage?"

"No," she said.

He rang the bell in the wall again, kept his finger on it.

"I'd like to know why not," he said.

"I have the greatest admiration for Mrs. Duffs ideas," she said. "She's truly, sincerely democratic. I wish I'd been brought up with a little more of that, myself. I think that spirit is increasing at home, in England. And really it's not because Nolan's a chauffeur that I object to him. It's because of his—character."

"And Mrs. Duff stands up for him?"

"I shouldn't put it quite that way," she said. "It's simply that Mrs. Duff is so very honest—"

The housemaid came in now with the tray.

"You've forgotten the bitters," said Duff. "Hurry up with it, will you?"

"I didn't see any bitters, sir. I read the names on all the bottles—"

"Let me get it!" said Miss Castle, rising.

"No, no!" said Duff. "Sit down. Miss Castle. You come with me, Mary, and I'll show you..."

He got the bottle from the pantry, and when he returned to the sitting-room, Reggie was there.

He remembered that when he had first seen her the thing that had most charmed him had been her look of exquisite cleanliness. Flower-like, he had called it. Very well; she was flower-like now, in a black-and-white checked evening dress with a long skirt and a prim little bodice buttoned up to the neck, her black hair soft about her pale, clear face; her blue eyes brilliant.

But it failed to charm him now. He knew how it would be to take her in his arms. She would nestle against him, feeling boneless; there would be a faint scent of talcum powder about her; she would be pleased with his love-making, as a kitten may be pleased at being picked up. And, like a kitten, she was happy when let alone.

Does she let Nolan make love to her, in that same way? he thought.

He mixed the cocktails and poured out two; none for Reggie. "I've never had a drink in my life," she had told him in the beginning, "and I guess I never will. I've seen too much of it, right in my own family." She had told him a tale about an Uncle Vincent, who had begun to drink and had ruined himself. It was just the saddest thing, she had said.

"Dinner is served, madam," said the maid.

"Can you put it back ten minutes, Reggie?" Duff asked. "We'd like to finish our drinks in peace."

"Oh, yes!" said Reggie. "Mary, will you tell Ellen, please?"

But the drink was spoilt now; there was none of that pleasant feeling of relaxation.

"There's a dividend here for you, Miss Castle."

"Oh, no, thanks! One is just right for me."

So he had to finish up what was in the shaker, and much too quickly.

"Well, is it all right to have dinner now, Jake?" Reggie asked.

"Certainly," he said.

He had no appetite at all. But that's all to the good, he thought, with this new diet. Reggie and Miss Castle went past him into the dining-room and he followed them.

"What do you think of them, Jake?" Reggie asked. "The new chairs?"

He thought they were terrible: a sort of bogus Windsor style, with cane seats and cane insets in the backs.

"Very nice," he said.

He drew back her chair for her; Miss Castle was already seated, and he went to his end of the table. The new chair was not only ugly but uncomfortable; the seat was too narrow, the arms constricting. He did not like the soup set before him.

"It's a meatless day," Reggie said, "but we've got some nice creamed sweetbreads—"

"Not for me, thanks," he said. "I'm on a diet. I told you so, this morning."

"Well, what can you eat?" she asked, anxiously. "Scrambled eggs, Jake? Or—"

The cane seat of the chair gave way. As he seized the arms and tried to rise, he fell over sideways, caught in the chair. Reggie came running to him.

"Oh, Jake!" she cried. "Oh, gosh! Are you hurt? Oh, Jake, I'm terribly sorry!"

Now he hated Reggie.

"No, thanks," he said. "I don't want anything more."

"But, Jake, you haven't eaten a thing—!"

"Nothing more, thank you. I've brought home some work to do. Good-night, Reggie. Good-night, Miss Castle."

He went off to that study, a ridiculous room, and locked the door. He took up Uncle Fred's book, but his hands shook so that he could not hold it. He had a bottle of whiskey in a drawer of the desk; he brought it out and poured himself a drink.

All right! All right! he told himself. I'm going to put the whole thing out of my mind. It's nothing.

Only, Miss Castle had seen him. Very well. She wouldn't think anything of it. A little—contretemps. Could happen to anyone. It's nothing. Simply, if you're a little overweight, you're—sensitive about a thing like that.

Damn those chairs! It takes Reggie to buy such flimsy, tawdry stuff. Damn. All right! Damn Reggie. Everything's finished between us, as far as I'm concerned. Even Aunt Lou could see that now, if she were here. I've got to get out.

There was a knock at the door.

"Yes?" he said.

"It's me, Jake."

"I'm very busy just now, Reggie."

"Just a minute, Jake! Please!"

He put away the bottle, and hid the glass under the desk, and unlocked the door.

"Jake, I'm so terribly sorry about what happened."

"It's nothing. Absolutely nothing, my dear girl."

"Jake, I'm so sorry. I guess those chairs just weren't any good."

"It's nothing. Let's not talk about it."

"Jake, could I sit in here with you for a while, and just read?"

"Thanks, but I have some rather important business papers."

"Could I type for you, Jake?"

"No, thanks. No typing to be done."

"Jake..." She laid her hand on his arm. "I just hate for us to get like this."

Then do something about it! he cried in his heart. Do something to stir me, to make me care again. Don't stand there-like a damn flower...

"Haven't you been feeling so well lately, Jake?"

"Never better," he said.

"I've been worried about you, Jake."

"And why?"

"Well, you hardly eat a thing, Jake." She paused. "I was talking to Aunt Lou today, Jake. About when you were a little boy. She said you always were terribly hard to—amuse. She said you always got bored so easily." She paused again. "I thought maybe you were sort of bored now, Jake," she said.

"Oh, certainly not!" he said, with bleak politeness.

"Because if you are, Jake, couldn't we do something about it?"

We? You could. You could be even a little exciting, a little seductive.

"Could we go out more, maybe? To shows, or night-clubs, or whatever you like?"

"Thanks, Reggie, that's a very nice idea. Later on, perhaps."

"Jake... We used to love each other..."

"Certainly. We do now. But at the moment, I'm pretty busy. If you'll excuse me—"

"Well, good-night, Jake," she said, and kissed him on the cheek.

One of her damn flower-kisses, he thought. I'm not going to go on like this. I can't stand it, and I won't.

HE waked in the morning, feeling strangely ill. When he got out of bed his legs were so weak he could scarcely stand. There was a grinding pain in the pit of his stomach.

This is no hangover, he said to himself. Anyhow, I didn't drink so much last night. No. This is something else. Something serious.

He was afraid to take a cold shower, feeling like this. He dressed as quickly as he could, but his hands trembled horribly. When he brushed his hair, one of the brushes somehow twisted in his hand and hit him a whack on the head. He had a very bad time with his necktie.

This is no hangover, he thought. I've had plenty of them in my day, and this isn't one. I'm going to take a drink, but it won't help me much. Not with this thing, whatever it is.

He had the good luck to get downstairs without meeting anyone. He remembered that the bottle in the study was empty, and he had to go to the cellarette in the dining-room. That was almost too much. Mary might come in, Reggie, Miss Castle, Jay, anyone, and see him taking a drink—before breakfast. The thought of it made him sweat with fear and dismay.

But I've got to! he cried to himself. I can't go on this way. He opened the cellarette in the sideboard, he unscrewed the top of a bottle, and he had poured himself a generous drink before he noticed that it was gin instead of whiskey.

"Oh, damn!" he said, aloud.

But then an idea came to him. He put the bottle back and filled up the glass, already half-full of gin, with stale water from the carafe; he carried it into his study and closed the door. He scribbled some meaningless figures on the pad before him; he sipped his drink, and lit a cigarette. He knew Reggie would come knocking at the door, and she did.

"Come in!" he said, absently.

"Oh, Jake! You shouldn't smoke before breakfast, hon!"

"Just a minute..." he said, in the same absent tone, and wrote down some more figures. He lifted the glass and took another swallow. "I'll be with you in a moment, Reggie."

Anyone would take it for granted that what he had was a glass of water. You don't expect to see a man drinking gin at eight o'clock in the morning. Normally, he thought, I'd say it was a pretty bad sign, pretty serious. Only I'm so damn sick...

Only he wasn't. That strange weakness, the pain, the trembling, were all passing away. His brain became clear, and he remembered the plan he had made the night before. It was a good plan, and he intended to carry it out at once.

He went into the dining-room, and for the first time he noticed that it was raining outside; there was a grey, dull light in the room. Reggie was wearing a black dress with long sleeves; she looked, he thought, like a shop-girl.

"Jay...!" said Miss Castle, and Jay stood up.

"G'morning, Daddy!" he said, and sat down again, so hard that his chair slid back a little.

"Good-morning," said Duff. "Good-morning, Miss Castle."

"Good-morning, Mr. Duff."

He liked all this good-morning good-morning ritual; he liked the looks of Miss Castle, in her white blouse and grey skirt, with the healthy color in her cheeks. And Jay, he thought, was a rather remarkable child. Not exactly handsome, but even now, at this age, he looked like Somebody.

"You can eat plain boiled eggs, couldn't you, Jake?" asked Reggie.

"No, thanks," he said. "I'm a little off my feed. Need a change, probably. Tell you what, Reggie. If you haven't any engagements, suppose we go out to the shack for the week-end?"

"Oh, I'd love it!" she said.

"Good! You can drive out this afternoon, and I'll come straight from the office. We can eat dinner at the Yacht Club, to save you trouble."

"Oh, let's eat home! I'll get things on the way. I love to cook, Jake."

"Nolan can wait there until I come," he said. "I don't care to have you there alone. It's pretty deserted, this time of the year."

"All right, Jake," she said.

He drank a cup of coffee and ate a slice of toast.

"Kin I go now?" Jay asked.

"No," said Duff. "You're to stay at the table until other people have finished."

Jay leaned back in his chair and folded his arms.

"Unfold your arms," said Duff.

"Well, why? What's bad about that?"

"Do as you're told," said Duff.

Jay stretched out his arms straight from the shoulders, and looked at his father sidelong.

"Sit properly!" shouted Duff.

"Well, how? I don't know how you mean!"

"Then I'll teach you. You need a good thrashing."

"I do not!" said Jay, and began to cry.

"Come, Jay!" said Miss Castle, and taking his hand she led him out of the room.

"Honestly, Jake, he doesn't mean to be naughty," said Reggie. "It's only—"

"Would you very much mind not explaining my own son to me?" he said, pushing back his chair. "I know exactly what's wrong with Jay."

And it's you, he thought. He used to be a very well-behaved child; people spoke of it. But you encourage him to spend his time with the servants; you send him out to the garage. To Nolan.

I've got to get rid of Reggie, he thought.

He did not care for the thought in that crude form. I mean, he said to himself, that I want a separation. We're not suited to each other in any way, and it is ruinous for the child. She can't be so very happy, herself. Perhaps if I simply went to her and proposed a separation, she'd agree. But Aunt Lou would make such a hell of a row about it. Give Reggie a chance. The poor girl. All that. She won't see.

So I've got to go through all this unpleasantness, he thought. His plan of last night was indeed detestable to him. It's not the sort of thing a gentleman does, he thought. But what else can I do? I haven't been into her room for nearly two months—and that doesn't seem to bother her. I never bring anyone here. I never take her anywhere. If she wasn't so damn stupid and common, she'd have seen... And, at that, maybe she does see. It's a nice life. Plenty of money, plenty of clothes. Mrs. Jacob Duff...

He hated the house and was glad to get out of it, but he hated the office too.

"I'm just stepping up for a cup of coffee," he told Miss Fuller at eleven o'clock.

He went to another bar this time, so that this little pick-me-up would not look habitual. And in this place he came across a fellow he knew, Sammy Poole.

"Hello!" Duff said, with an air of immense surprise. "What are you doing here, this time of the day?"

"Oh, I come every morning," said Sammy.

He did not seem to see anything out of the way in it. He seemed very healthy, too; he played golf, he went to a gym, and so on. Duff did not make the explanation he had been ready to make. If Sammy could take this for granted, so much the better. He had two drinks, just two; he was never going beyond that. Then he went back to the office.

I don't know, he thought. Maybe I'll cut lunch out entirely. You're bound to lose weight that way.

He dictated some letters, he saw two or three people, he talked to Hanbury.

"Mr. Duff," said Miss Fuller, "will it be all right if I go out to lunch now? It's after two."

"Oh, certainly, certainly!" he said. "Go right ahead. I didn't realize the time."

When she had gone, he had nothing to do, and he felt very sick again. He went out to the first bar, and it upset him. I can't go running in and out of bars all the time, he thought. It doesn't look well. I ought to keep something in the office, in case I want it. Plenty of fellows do that. Only Miss Fuller's in and out, all the time.

He felt a little better when he got back. At four o'clock he called Vermilyea.

"Don't hesitate to turn this down, old man," he said. "But here's the setup. My wife's gone down to our place on the shore, and I want to join her. But the garage people can't fix me up with a car. Can't—or won't. It's a hell of a trip by train, with those two changes, so I thought that, if you had enough gas, maybe you'd drive me down and stay overnight."

"Very pleased to, Duff," said Vermilyea. "What time?"

"I can't get away very early," Duff said. "I'm up to my ears in work. About seven, say?"

"There's a train leaving Grand Central at six-twenty-two," said Vermilyea. "How would that do. Duff? I could meet you at the Vandenbrinck station."

"Fine! Fine!" said Duff. "I appreciate this, Vermilyea."

Then he called up the shack, and Reggie's voice answered.

"I'm sorry, Reggie," he said, "but something's just turned up. This man's coming from Washington, and I've got to wait. I'll take a room in a hotel for the night, and I'll be out early tomorrow morning."

"Oh, I'm sorry, Jake!"

"And tell Nolan to stay," he said. "I don't want you out there alone."

"All right, Jake," she said. "Take care of yourself, and I'll see you tomorrow."

He disliked his plan more and more. But if Reggie's behaving properly, there'll be no harm done, he thought. And if she isn't... then I needn't have any compunction.

He knew Reggie well enough to feel almost sure she would be doing something that would look wrong. Something that would shock Vermilyea. For she had no dignity, no discretion.

Pictures came into his mind. Suppose they were to find Reggie and Nolan sitting side by side on the front steps, talking and laughing? Drinking soft drinks out of bottles! He imagined himself telling this to Mrs. Albany. You can realize how I felt, he would say, arriving there with a fellow like Vermilyea, and finding my wife and the chauffeur...

If they'd only be making love...! he thought. No matter what I find, I shouldn't make use of it. I'd still let her get the divorce. I'll provide for her decently. It's simply that I want somebody to realize what she really is. Aunt Lou, above all.

Vermilyea was waiting for him on the Vandenbrinck station.

"You're looking a bit seedy, Duff," he said.

"I'm dog-tired," said Duff.

"Take a little snooze, on the way out," said Vermilyea. "Nice night, after the rain this morning."

Duff leaned back in the dark car and closed his eyes. There couldn't, he thought, be a better witness than Vermilyea, a man of honor, a gentleman, who would understand all the implications of what he was going to see. Mrs. Duff and the chauffeur, sitting on the steps, drinking pop out of bottles, his arm around her shoulder.

It was worse than that, though. There was a merry-go-round on the lawn outside the house, and Reggie sat on a coal-black horse, with Nolan behind her, holding her round the waist; they went round and round, laughing, to very loud music. Fortunately Aunt Lou was with him, and she could see for herself how it was.

"The whole neighborhood's complaining," he told her. "But she doesn't care."

He opened his eyes and they were in the main street of the village, with a radio playing loudly somewhere.

"Oh, look here, Vermilyea!" he said. "Mind going back just a couple of blocks? I want to stop at the liquor store. There's nothing in the house."

The man in the store knew him well, from the days when he used to come down here with Helen.

"You're starting early," he said. "There isn't anybody else has come down yet."

"I've been working pretty hard," said Duff, "and I thought I'd like a little sea air."

"Nothing like it," said the man.

"Might as well stock up. Two bottles of rye—and I might as well take a couple of bottles of gin. A lot of people seem to like gin drinks, Martinis, Tom Collinses, and so on. Personally, I don't like gin."

He wondered a little why he had said that and why he was talking so much. It's because I'm upset about this thing, he thought. He got back into the car with a big paper bag, and Vermilyea started off again. They turned in to the Shore Road, and there was the sea, pale under the starry sky. Some ten feet below the road and fronting the ocean was that solid and comfortable little bungalow which he and Helen had always called 'the shack'. It was the only lighted house to be seen.

"I hope Reggie got my wire," said Duff. "I couldn't get her on the telephone, so I sent her a wire to say we'd be along."

"Certainly hope so," said Vermilyea. "I shouldn't like to cause Mrs. Duff any inconvenience."

"Better leave the car up here," said Duff. "Nolan will take it down to the garage. It's a rather tricky bit of road."

Vermilyea parked the car at the side of the road, and Duff led the way, down a flight of wooden stairs to the beach. His knees felt weak; he felt cold and wretched. Suppose we find something—outrageous? he thought. Suppose she's got Nolan in her room? Well, Vermilyea would never talk. Nobody else would know.

He mounted the three steps to the veranda and looked in at the sitting-room window. Nolan, in his shirtsleeves, was doing something to the radio, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth. Reggie sat in a wicker armchair, with Jay on her lap.

"OH, hello, Jake!" cried Reggie.

"Hello, Mr. Vermilyea!"

"Hello!" Vermilyea answered, smiling broadly.

"Nolan, get Mr. Vermilyea's car into the garage," said Duff. "Jay, you ought to have been in bed hours ago. What's the child doing here, anyhow, Reggie?"

"Well, he wanted to come," she said.

Duff was struggling against a furious anger that was beyond his understanding. Anger against Nolan, who was leisurely putting on his jacket, against Reggie in her black dress, even against Jay.

"Go to bed at once. Jay," he said.

"Well, I'll have to change him in to the guest room, Jake," said Reggie. "I didn't know you were coming, and I was going to keep him in with me."

"Didn't you get my wire?"

"Why, no, I just—"

"Don't change your arrangements," said Duff. "I'll share a room with Vermilyea. Only get that child to bed."

He was very nearly shouting, and that wouldn't do. He must get himself in hand.

"Sit down, Vermilyea!" he said, with great heartiness. "Sit down! Sit down! We'll have a drink. What's yours, gin, or rye?"

"Rye, thank you. Duff."

"Personally, I don't care for gin," said Duff.

No sense in saying that all the time. He went into the kitchen, and there were no ice cubes in the refrigerator; no soda. He opened a bottle of gin and poured himself a drink, and put the bottle back in the paper bag. Then he opened a bottle of rye and brought it, with two glasses, into the sitting-room.

"Sorry to say there's no ice, old man, no soda."

"That doesn't bother me," said Vermilyea.

"I'll get some water," said Duff, and returning to the kitchen, he drank the gin and rinsed out the glass.

"Cigarette, old man?"

"I'll use my own, Duff, thank you. They're worth their weight in gold, these days."

"Here! Here! Take one of mine!" said Duff. "I've got plenty, at the moment. My aunt, Mrs. Albany, gave me two cartons last week. Remarkable woman."

"So I've heard. Roger and Elly Pendleton know her."

"Remarkable woman," Duff said. "Sixty-five years old, and still-remarkable. Used to do a lot of big-game hunting with her husband, y'know, and I believe she could do it now. Y'know, when I was a kid, I used to like it better than anything when she'd come out to see me in school. She'd bring a souvenir—from Africa, India, wherever she'd been, and she'd have stories to tell that were better than any book you ever read. The other kids would all gather round... A thorough sportswoman. Thorough."

"Very interesting, Duff."

Duff told a story about Mrs. Albany and a rhinoceros.

"Well, by Jove...!" said Vermilyea.

"My uncle used to say he'd rather have her beside him in an emergency than any man he'd ever met."

"That's certainly a fine compliment," said Vermilyea.

"Yes. True, too. Another spot, old man?"

"Just a small one, Duff. You're not taking any?"

"Well, no," said Duff. "To tell you the truth, it's apt to make me wakeful if I take a drink around bedtime."

"It's just the other way with me," said Vermilyea, seriously. "It's a very rare thing for me not to go to sleep as soon as my head touches the pillow, but if it ever does happen that I can't sleep, a jigger of whiskey will always send me off."

"You're lucky," said Duff.

He was waiting for Reggie to come back. At least she'll have manners enough to say good-night to Vermilyea, he thought. But eleven o'clock came, and Vermilyea was politely covering a series of yawns.

"Shall we turn in now?" he suggested.

From his overnight case Vermilyea brought out pajamas, dressing-gown, slippers, a few toilet articles, a razor, everything of the best quality and absolutely right. God, what a relief to be away from Reggie, with her flimsy things strewn all around!

Vermilyea was breathing calmly in his bed in the dark room, asleep already. And what had he thought of that scene, that nice, cozy, domestic scene? Mrs. Jacob Duff, and the chauffeur in his shirtsleeves and a cigarette in his mouth.

Why did she bring the child here? he thought, his anger rising and rising. She's ruining him. Encouraging him to hang around with the servants all the time. God knows what he's picking up.

After a while he rose and went barefoot into the kitchen. He poured himself a drink of gin, a good one, too. I've got to get some sleep, he thought.

He went back to bed, and now he was able to sleep, in the cool breezy dark.

When he waked in the morning, Vermilyea's bed was empty. He heard voices near, he heard Jay laughing, and Reggie. She's turning the child against me, he thought. When Helen was alive, he'd run to meet me, as soon as I came into the house. Only four years since Helen died? I can't realize it... Aunt Lou could have stopped this—disastrous second marriage. Only time I've ever known her to use poor judgment.

He felt sick, very sick, but he had expected to be. I was a damn fool not to bring a bottle in here last night, he thought. Now if there's anyone in the kitchen, I can't get a drink.

Yes, I can, he thought. He got out of bed and put on his dressing-gown and slippers. He went straight to the kitchen. In the dining-room Reggie and Vermilyea and Jay were all sitting at the table.

"Good-morning, everybody!" said Duff.

"Jay!" said Reggie, in nervous imitation of Miss Castle, and Jay stood up.

"Mrs. Duff's giving us a wonderful breakfast," Vermilyea said. "Wonderful! I only wish I had more time. But for a wonder I've got to show up at the office fairly early."

The big paper bag was on the sink-board. Duff picked it up and carried it into the bedroom; he did not explain, he did not have to explain. He had a drink of gin poured out and standing on the dresser when Vermilyea came in to get his bag.

"I've enjoyed this very much, Duff," he said. "You're a lucky man."

"Oh, very!" said Duff.

No sooner had Vermilyea gone than Reggie came knocking at the door.

"Come in!" said Duff, with a sigh.

"I just wanted to know if you'd like some little sausages, Jake," she said.

"No, thanks, I shouldn't."

"Jake," she said, "now that we're down here—now that we've got more time together—couldn't we have a good long talk?"

"About what?" he demanded.

"About—whatever it is that's gone wrong between us."

She had never taken the initiative before, never had questioned him. He was not prepared for it; he did not know how he wanted to answer her.

"I'm afraid we haven't much time," he said. "I've got to go in to the office this morning."

"Oh, I thought we were going to stay here over Sunday. I told Jay so. He'll be disappointed, poor little fellow."

"I'm sorry," said Duff, briefly.

Why didn't she go away? She was obviously nervous, one hand picking at her dress, a warm color in her cheeks; she did not look at him. She's guilty! he thought.

"Jake..." she said. "Jake, honey, what's happened?"

"What d'you mean? What are you talking about?"

"Things seem to have gone—all wrong between us," she said, and there were tears on her cheeks. "I guess all married people have their ups and downs—but I thought that if we could just clear things up— if we could have a good long talk, Jake..."

"My dear girl," he said, "this is hardly the time. I haven't had so much as a cup of coffee, and—" He paused. "I'm not feeling any too well," he said.

"I knew that!" she said. "For quite a while I've thought you seemed queer."

"Tactfully put," he remarked.

"I didn't mean to be tactless. It's only that—"

"D'you mind if we postpone this?" he asked. "I'd like to finish dressing and get some coffee."

She went away then and he finished his dressing and his drink in haste. But instead of going to the dining-room, he went out of the house, to the garage. The door was open, and Nolan stood there, smoking.

"Morning, sir!" he said, alertly.

"Good-morning," said Duff. "We'll be leaving in an hour. And after you've driven us home, I'll pay you whatever is due you, and you can go."

"And why is that?" asked Nolan, with interest.

"I don't care for your manners," said Duff. "I don't care to find my chauffeur in my drawing-room, in his shirt-sleeves, smoking a cigarette."

Nolan drew on his cigarette.

"I know a frame-up when I see one," he said.

Everything in Duff drew together against this blow.

"What are you talking about?" he asked.

"I've been around," said Nolan. "You tried to frame me and your wife."

"Keep quiet!"

"For the time being, I will," said Nolan.

NOLAN'S going to blackmail me, thought Duff. Or try to, anyhow. But he can't prove anything. Can't prove I didn't send a wire to Reggie—or anything else. Only I don't want him putting any ideas into Reggie's head.

That thought made him sweat with dismay. If Reggie should turn on him, accuse him of this contemptible thing... I couldn't stand that, he thought. It was a mistake, anyhow. I'm sorry I ever tried it. It's not like me.

And if Vermilyea ever knew...? All right. Duff thought. I'm sorry. It was a bad idea, the sort of thing a gentleman doesn't do, or even think of. But I don't see how Vermilyea ever could find out. Who'd tell him? He wouldn't believe it, anyhow.

But Reggie might believe it, if Nolan told her. She and Nolan, no doubt, spoke the same language. Very likely they both knew of instances like that, a suspicious husband coming home, when he had definitely said he would not be home. It was such a damn vulgar thing for me to do, he thought.

"Is the coffee all right, Jake?" she asked.

"Very good. Very good indeed."

That pleased her.

"I'm terribly glad you like it, Jake," she said. "I honestly think I could get to be quite a good cook. I know I'd love it. Only, living around in furnished rooms the way I did before we were married, I never got a chance."

"No, of course not. Can you be ready in half an hour, Reggie?"

"I'll just wash up the dishes, Jake—"

"Don't bother. Mrs. Anderson comes in once a week to air the place. She'll attend to them."

"Honestly, I'd rather, Jake," she said. "I'd hate to go and leave dirty dishes. It'll only take a moment."

"Well, if you'd rather—" he said, and his indulgent tone brought out her wide, dazzling smile.

I'm going to behave differently, he thought. Not going to be irritable. And if Nolan does try to put any ideas into her head, she won't believe them. Anyhow, it wasn't a frame-up. I simply wanted to see if that fellow was too familiar and free-and-easy when I wasn't around. Very well. I did see.

He went into the bedroom to pack, and as he took the three bottles out of the paper bag, he frowned to see how much gin had gone since last night. Of course, the stuff evaporates, he thought, but even at that, it's too much. I'm cutting down.

Reggie was still in the kitchen and Jay was with her, drying the dishes.

"Soldiers dry dishes!" Jay said. "Reggie's a trained nurse, and I'm a soldier."

Duff very much disliked the child's calling her 'Reggie', but he had never been able to think of a reasonable substitute. He didn't like to see Jay drying dishes, either; the whole atmosphere was displeasing. When he and Helen used to come here, they had always brought a maid along; everything had been informal, but not like this.

"I've nearly finished, Jake," she said. "I just want to leave things nice and neat."

"I see! I've been thinking, Reggie... I'll be finished early at the office. Suppose you come in to town by train with me, and Nolan can drive Jay home. You could do a bit of shopping, and then we could meet somewhere for lunch?"

"Oh, I'd love it!" said Reggie.

"I want to go to New York, too," said Jay.

"Not today," said Duff.

"But I'll bring you a surprise," Reggie told the child, and he seemed satisfied.

Nolan drove them to the station and they got on the train.

"I want to speak to you about Nolan, Reggie," said Duff. "You don't realize how insolent the fellow is."

"Honestly, he's never said anything—"

"I was shocked," said Duff, "when I saw him there in the sitting-room."

"But he was just fixing the radio. I asked him to, Jake."

"I don't suppose you asked him to take off his coat and light a cigarette, did you?"

"Well, no. But I don't think he meant to be fresh."

"He's a good deal more than what you call 'fresh', my dear girl. I'm going to let him go."

He watched her covertly, to see how she took that, but he could see no emotion in her thin, gentle face.

"Well," she said, "I guess he can find another job, easily enough."

"That doesn't interest me," said Duff. "He'll certainly get no reference from me."

"But, Jake, that seems kind of hard on him."

"My dear girl," said Duff, "he's a dangerous man."

"Dangerous, Jake?"

"Yes," said Duff. "I don't want to go into details, but he made an attempt to blackmail me."

"Oh, Jake, how could he? What about?"

"Let's not talk about it, Reggie. Fortunately, I knew how to deal with him."

"But, Jake, what could he possibly try to blackmail you about?"

Duff was silent for a moment.

"I'm not going to tell you, my dear girl," he said, presently.

"Jake! Was it something—about me?"

"I'm not going to talk about it any more," he said, and patted her hand. "It's finished."

"Jake, if I did do something that looked wrong some way, I'm terribly sorry."

"Don't worry, Reggie," he said, with his hand over hers.

All right! he thought. Now let Nolan go to her with his tale about a frame-up—and see where it gets him.

He saw Reggie into a taxi at the Grand Central, and went off, in another cab, to his office. Eleven o'clock came, and he was pleased that he had not the slightest desire for a drink. I certainly shouldn't want to make a habit of that, he thought.

He was to meet Reggie at one, in a midtown hotel; he got there a little early and stopped in the bar for a double Martini. A cocktail doesn't hurt you, he thought, as long as you eat directly after it. Although, if I'd been having lunch alone, I shouldn't have wanted a drink. Only, it's so damn hard to talk to Reggie. She has nothing to say for herself. She's never been anywhere, never seen anything.

When he entered the restaurant, Reggie was waiting for him, and he felt a slight shock at the sight of her beauty and her air of distinction. She was wearing a new costume, a grey suit that brought out the long fine hues of her body, a blue blouse, a blue turban with a white band that encircled her broad and candid brow like a coif; grey gloves, a blue pocketbook. Dressed so, with her head set so well on her slender neck, her straight back, her way of sitting so quietly and easily, she looked aristocratic.

This irritated him, and so did her smile when she caught sight of him.

"Hello, Jake!" she said. "How do you like my outfit?"

"Extremely nice."

"I telephoned to Aunt Lou and she came with me."

"Well, you did a very fine job together," he said.

The headwaiter led them to a table with which Duff could find no fault. He took up the menu and studied it.

"You order for me, Jake," she said, "You know what's nice."

"There's nothing nice here," he said.

"Why don't you have a cocktail, Jake, to give you an appetite?"

"It's not a good idea, to drink in the middle of the day'."

"Well, but just for once—?"

"All right!" he said, with a good-humored laugh. "A dry Martini, waiter. Or you'd better make it a double. That saves time," he explained to Reggie. "As long as you're not drinking, You naturally don't want to sit here and watch me."

"I don't mind, Jake. Jake, Aunt Lou was asking me how things were."

"What things?"

"I mean, if we were—sort of settling down better. And I told her yes.

"Oh, did you?"

"Yes. You were sweet to me, Jake, about whatever it was Nolan tried—"

"You didn't tell Aunt Lou about that, did you?"

"Oh no! I just said I thought things were going better, and she was terribly pleased."

"I see!" he said, absently.

I did the right thing, he thought. It's better, in every way, to have things pleasant and friendly between us. If Nolan goes to her now with his fantastic tale, she wouldn't believe a word of it. Only, I'm not going in for any love-making.

"Reggie," he said, "if I haven't seemed very lover-like recently, it's because I haven't been well."

A burning color rose in her cheeks.

"Oh, well, but, Jake..." she said. "Marriage isn't just—that. I mean—that..."

Good God! he thought. It's revolting. She's like a sixteen-year-old girl in a convent. It's impossible to talk to her about anything.

"We'd better order now," he said. "I told Nolan we'd get the two-fifty."

He had a little nap on the train, and when he waked he felt greatly refreshed. Nolan was waiting on the platform, handsome and alert. As they drove to the house. Duff kept his eyes upon the fellow's strong young neck, kept his thoughts upon the fellow's insolence.

"I'd like a word with you, Nolan," he said, when the car stopped.

"Very well, sir," said Nolan, and followed him into the study.

"Close the door," said Duff. "Now, then. I'll pay you whatever's coming to you, and you can clear out."

"Very well, sir," said Nolan.

"And don't use me for a reference."

"That suits me," said Nolan.

His bright composure nettled Duff. Somehow this interview was not going as it should.

"What's more," he said, "if I hear of your repeating that slanderous lie to anyone, I'll take steps."

"What steps?" asked Nolan.

"I've warned Mrs. Duff, so that if you make any attempt to repeat that lie to her—"

"If I was going to tell anyone about that frame-up," said Nolan, "it wouldn't be Mrs. Duff."

I must not ask him who it would be. Duff told himself. As if I were anxious.

But he had to know.

"Is that so?" he said, with a scornful smile. "The tabloids, I suppose."

"No. Mrs. Albany," said Nolan.

That was like a blow in the midriff. Now he had to fight.

"D'you imagine you could collect money from Mrs. Albany on the strength of a preposterous he like that?"

"We weren't talking about collecting money. The point is," said Nolan, "if I wanted to find someone who'd believe that story, I'd choose Mrs. Albany. Once she heard the facts, she'd see just how it was."

"You're trying to blackmail me, eh? Threatening to tell Mrs. Albany—?"

"I haven't made any threats," said Nolan, "and I haven't asked for any money."

"But you intend to later. That's obvious."

"To tell you the truth," said Nolan, "I'd never thought about blackmail until you brought it up. I thought the whole thing was rather funny."

"Funny?"

"Comic. So damn crude, telling me to stay there till you came, and then calling up to say you weren't coming. And then coming, late at night, with your witness. And finding the kid there. I thought it was funny. I still do."

"You're insolent!" cried Duff.

"Could be," said Nolan, easily.

Duff could think of no way to cope with this behavior. There were no demands made, no menaces to parry, nothing here to fight.

"I'll write your check," he said. "But remember, if I hear anything more of that lie of yours—"

Nolan said nothing. He didn't smile; there was nothing to be read in his alert face. He took the check Duff held out to him.

"Thanks," he said, and turned away.

And where was he going? What did he intend to do?

If he does go to Aunt Lou with that tale, Duff told himself, she'll make short work of him. I don't see her listening to servants' gossip.

No ... he said to himself, with a dreadful sinking of the heart. She'd believe it.

He was sure of that. She was completely loyal to him, she was fond of him, but, better than anyone else, she knew his weaknesses, his potentialities. If she heard this story, plainly told, all the facts provable, she would believe it, and she would forever despise him.

He could imagine no greater misfortune than to lose her approval. She was his conscience. Whatever she said was right; what she condemned was wrong. Since his childhood, her opinion had been the important one. His parents had left little impression upon him. He had respected them, he had been grief-stricken at their funerals, hut he had almost completely forgotten them. It was his Aunt Lou who had completely captured his imagination, that spare, energetic woman, back from jungles and veldts. The presents she gave for birthdays or Christmas had an almost mystic value. Above everything else on earth he was proudest of being her heir.