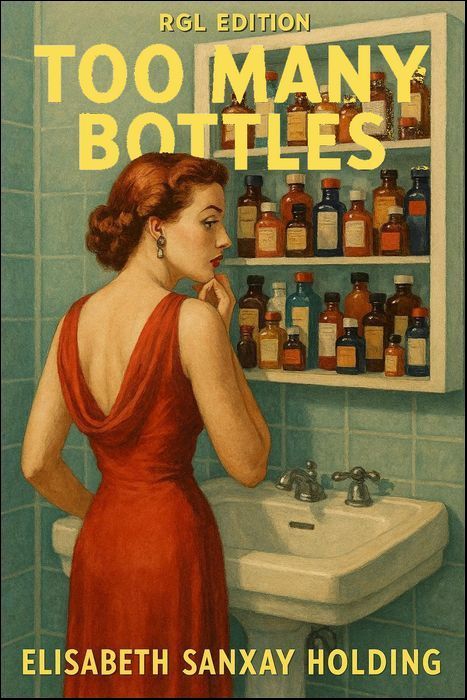

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

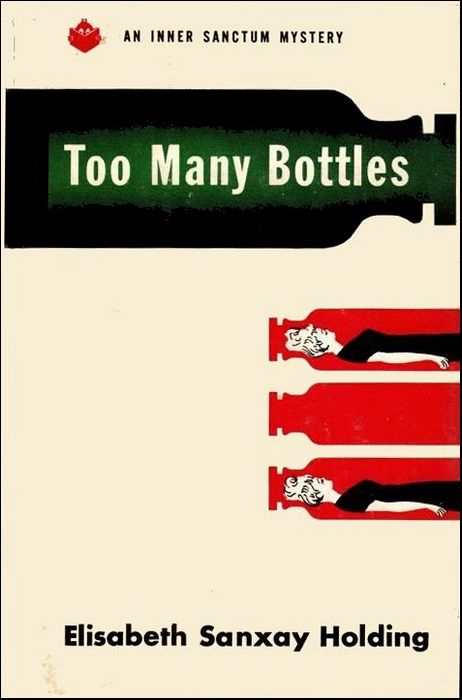

"Too Many Bottles," Simon & Schuster, New York, 1951

"Too Many Bottles," Simon & Schuster, New York, 1951

"The Party Was the Pay-off," Mercury Publications, New York

"The Party Was the Pay-off," Mercury Publications, New York

JAMES BROPHY was a writer, a mild man and hardly homicidal, but as he gradually realized that his wife, Lulu, was little more than a self-pitying shrew, there were times when his inclinations became slightly murderous. Life in the Brophy household was far from placid and something was bound to happen. The something happened on a Sunday afternoon when Lulu gave a cocktail party—the party that was the pay-off. For Lulu grew more and more frenzied and more and more pallid, and by morning the party was over and Lulu was dead. That was when James Brophy, writer, became James Brophy, suspect, a man without an alibi. He concentrated desperately on the party. Wasn't it possible that something suspicious had been said there? Couldn't that something have been overheard? Now, if only he could find a person with a clue, if only that person would stay alive long enough....

THIS party is the pay-off, James Brophy said to himself, as he began to shave. The buzz of the electric razor seemed to him unusually loud this afternoon, like an angry bee shut into the stifling bathroom with him. The afternoon sun made the opaque window blaze like a diamond; the mirror was misted from the hot water he had run, distorting his image a little.

God! he thought. It's hot in here. But the damn window won't open, and if I open the door, Lulu will come in. She'll sit on the edge of the bathtub—"perch" is what she'll say. And she does "perch." On railings, on the arms of chairs. She'll want to talk about this party, and it will be a damn mistake. It's the pay-off. That would make a good title. The Party Was the Pay-Off, This woman would be giving a cocktail party, and somehow she asks the one person in the world she's afraid of. Blackmailer? No. Someone who wants to murder her?

He was growing interested in the idea, almost excited. Someone brings this fellow, he went on. She's been hiding from him—changed her name. Thinks—Oh, Lord! Here she comes! Lulu!

A door had opened, along the hall; he heard the sharp tap of high heels. She always sounds as if she were walking very fast, he thought. But she isn't. She's like a little wooden horse, prancing up and down in the same spot. The knob turned; she was trying to open the door.

"Let me in, Jimmy—Jim," she called.

"Can't, right now, Lulu."

"Yes, now! I want to get some medicine."

She rattled the knob hard, and that was a thing that irritated him.

"In a moment," he said.

"Now!" she cried, rattling the knob again. "I want to take my medicine before the people come!"

"In a moment," he answered. "You have plenty of time."

That made her very angry. Once more she rattled the knob, she gave the door a kick, and then he heard her sharp heels prancing away. Couldn't let her in, he thought. Couldn't have her opening the medicine cabinet right in my face while I'm shaving. Lord, what a lot of medicine she takes!

He was not angry at her, or even seriously annoyed. That's married life for you, he thought, and that was his custom. The things that wearied and exasperated him he blamed married life for, and not Lulu in particular. His parents had been forever bickering; he had married friends who were like that; you saw and heard such couples on the radio, in the movies, in comic strips—the wife stamping her foot, ordering her husband to mow the lawn; the husband cringing up the stairs, shoes in hand, after a poker game with the boys. He had never wanted to marry, and to this day he could not quite understand why he had done it.

He had met Lulu on a West Indies cruise, the first time he had ever been aboard a ship. She was a pretty little woman, and very popular; he was flattered that she should single him out. And he had thought then that she was sophisticated, a woman of the world. She had lived in Paris and in London; she knew people in New. York, well-known, even famous people; writers, artists, musicians. Yet she had shown so great an interest in his work.

"But I'm no celebrity," he had explained. "So far, I've worked mostly for the pulps. I'm just beginning to break into the slicks."

She had wanted to know what the pulps were, and what the slicks; she had wanted to know what he was working on then; she had listened with an interest he had never before encountered.

"I think artists ought to be taken care of," she had said.

Brophy believed that he was a pretty good writer, and that someday he would be a very much better one, but he was not inclined to think of himself as an artist.

"I want you out for a week-end," Lulu had said. "You'll have a room and bath to yourself, and the sun-porch, to work in, and absolute peace and quiet. My sister Norma will be there, for a chaperone."

Well, he had come out here, to this very house, and it had been as Lulu promised, peace and quiet for his work, and, in addition, the company of the two pretty, gay sisters, wonderful meals, sweet, sunny spring weather.

He had gone home to his gloomy little hotel room in New York, and, as soon as he had enough money, he had called up Lulu and invited her to dinner and a show.

"Oh, that's awfully nice of you!" she had said. "But I'm simply morbid about coming into New York in the summer. Couldn't I get you to come out here again? Come Friday, and make it a nice, long week-end."

"Well, but..."

"Do come!" she had said. "We'd love it."

Me had accepted, and it had even been better than the first time; the peace and quiet for his work, the delicious meals, the good drinks, the cheerful companionship of two young and pretty women. Norma was the younger and the prettier of the two, a slender girl, with chestnut hair and beautiful dark eyes; she was very quiet, with a slow and gentle smile, and she played the piano in a way that seemed to his uncritical ear remarkable and charming. There had been a time when he had thought he was more attracted to Norma. But not for long. She was too hard to talk with; indeed, if he had not been so fond of her, he would have called her a first-class bore.

And Lulu had never bored him. She would tell him little incidents from her former life, about trips she had made with the husband she had divorced. He had been pleased that she never said a word against the man, never complained of him; she would just mention him casually. When Mel and I were in Rome—something like that. She did not use his name, and Brophy did not know what it was, or care.

There had been days when she had been pale and fatigued. I couldn't sleep, she would say, or it's this migraine. I'm no good to anyone. Then she would not try to talk; she would sit in the garden with him, or in the living-room, and turn the pages of a magazine; sometimes she would lie back, with her eyes closed, and he knew he could either stay with her, or stroll off to find Norma. She never bothers you, he had thought. She's too independent.

They had had very little company; only now and then a few local people in for cocktails. I like to entertain, she had told him; dinners, everything. But two women alone, two sisters... It's rather ridiculous. Anyhow, I can take people, or leave them.

"You're pretty independent, altogether, aren't you?" he had asked.

"Thank God my father left me so that I could be," she had said.

Well, he had learned now, after a year of marriage, that she was not "independent," but desperately clinging. He had learned that she had no scruples about complaining of her former husband. And he had learned how she really felt about people, about entertaining; he knew now of her almost frantic desire to be "popular."

"I used to be!" she had cried. "I don't know what's the matter now. Maybe it's because I've been dragging Norma everywhere with me. Or—"

"Or if it's me?" he had asked, and she had made no answer to that.

Brophy himself had never thought about being popular; he had friends, old and greatly valued friends; there had been girls who had certainly shown no aversion to him. When he wanted company, he could always find it. But for the greater part of his time he was alone, and had to be alone, to do his writing. In the beginning, he had thought Lulu exaggerated the situation; he could see no reason why people shouldn't like them. But little by little, he had to face the truth. They almost never got an invitation; they were left out of things; Lulu would read the little local newspaper and point out to him that this neighbor or that one had given a garden party, a dinner, a Sunday lunch at the Country Club. And not asked the Brophys.

What really and sharply brought it home to him was the episode at Mrs. Wylie's garden party, to which they had been invited. Two girls had been standing on the lawn, facing the house; they had not seen or heard him coming up behind them.

"Oh, Lord!" one of them had said. "Isn't that the awful Brophy's car parked there?"

"Yes," the other said, and he knew her: Biddy Hamilton. "But I haven't seen the gorilla around, have you?"

He had moved away then, in haste, to prevent Lulu coming any nearer and hearing anything like that. But he could not forget.

He unplugged the razor and dried his face, and for a moment stood contemplating his image in the mirror. He was stripped to the waist, a sturdy young man of thirty-five, his broad chest tattooed with a green and blue mermaid. Such a hateful, vulgar thing, Lulu called it, from time to time, but he was rather fond of that mermaid; it reminded him of his three war years in the Merchant Marine. He was of a good enough height, five feet ten; he was straight, strongly built, only his arms were too long. He had, naturally, known since he was a kid that they were long, but it seemed to him now that they were—grotesque. He looked at his face, and it seemed different, almost unfamiliar. The map of Ireland, one girl had called it. But now—he didn't know.... The dark, curly hair that grew low on his forehead, the deep-set dark-blue eyes, the long upper lip... Gorilla?

Biddy Hamilton was one of the people Lulu had invited, sending out bright little cards. "Cocktails—6-8. Don't bother to answer. Just come!" She sent out over forty of these, many to New York; she had liquor enough for thirty-five, canapés of all kinds from a caterer, an extra maid.

I wish to God she hadn't done this, he thought. She'll be badly upset, miserable, if only a handful of people come. Now, in this story, the Party Is the Pay-Off, the hostess will be very popular. Has to be. Woman of the world. She's happy, pleased with herself. Until she sees this man arrive, brought by somebody else. She's been trying to avoid him, changed her name, and so on. He's a blackmailer? No.... I don't like that.

He unlocked the bathroom door and stepped out into the bedroom. Lulu was sitting at the dressing-table, putting on her make-up by the special light over the mirror, a fierce, white light, very unflattering. It's meant to be, she had told him. It shows up even the tiniest blemish.

"Hurry up and dress, Jim," she said, frowning, "Someone might come early."

"I will," he said.

Not a blackmailer..., he thought. No! No, look here! It's,not a man that comes in, to make all the trouble. It's a girl. I'll make her very nice, pretty. And the man the hostess thinks she's got hooked has been looking for this girl for a year. He's in love with her.

"There!" cried Lulu. "The doorbell! Fix my medicine for me, Jim, quick!"

"What medicine?"

"It's a new bottle that hasn't been opened, quite a small one."

"What color?"

"Oh, it hasn't any color! Do hurry up! It takes a little while to act, and I need it. I feel wretched today."

"I'm sorry, Lulu."

"A tablespoon in half a glass of water," she said.

He found the unopened bottle in the bathroom cabinet, and the spoon she kept there; he measured out the dose and brought it to her.

"Just put it down here on the dressing-table. I can't stop now...."

She was darkening her lashes, one eye tightly closed, as if in a painful squint; he watched her while he dressed.

"I'll go down now," he said. "Don't hurry too much, Lulu. I'll look after things, if there's anyone there."

"It's very likely someone you don't know."

"Well, even at that...," he said, smiling a little.

"Try not to be too Bohemian," she said, and picked up the glass of medicine.

That was a word she used often, and it irritated him; when she had first begun calling him "Bohemian" he had protested forcibly. But not any more. There's never going to be another quarrel, he had said to himself, long ago, and he had held to it. The quarrels they had had, in the early days together, had been intolerable to him. She would become hysterical, screaming at him in a voice that rang in his ears long after: twice she had rushed at him, pounding his broad chest with her fists, calling him anything, everything. I hate you! I hate you! Get out of my house!

But she did not hate him, and certainly she did not want him to leave her. He knew that. She could not master these frantic outbursts. He had heard her screeching at Norma, and a colored maid; sometimes when she was driving the car, some other driver would do something that enraged her; her olive-skinned face would flush darkly; she would begin to drive recklessly, until he had to take over the wheel. She would go on and on about that other driver, calling him—or her—the ugliest names she knew. Then, in time, the fury would ebb away, leaving her exhausted, pale, yet somehow relieved.

He had realized, months ago, that this was a most unhappy and unfortunate marriage for him. The "peace and quiet for your writing" that she had used to promise was lost; he had trouble enough to get any time alone. He never asked a friend of his to come here; he very seldom went in to New York. But he had his work, after all; he saw his old friends when he did get to the city; he was healthy, unexacting, and he had, in his mind, an unreasoned hope that somehow, at some time, things would get better.

As he stepped out into the hall, he saw that the door of "his" room was open. It was not his any longer; it was the one he had used to have, when he had come here as a guest; his own bathroom opening out of it, a little balcony. Norma was in there now, arranging flowers in a vase.

"This is the Ladies' Powder Room," she said, and smiled a little. "There's going to be a maid in a uniform. Does it look nice, Jimmy?"

"Very. And so do you."

He did not entirely mean that. She was always pretty, with her fair skin, the sweet color in her cheeks, her shining chestnut hair; she was well-made, too, with a fine, proud bosom and long legs. But he did not admire her clothes; nor the rose-pink dress she was wearing now, with a flowered silk sash in a big bow at one side, fancy short sleeves, fancy low neckline in scallops, a white bead necklace and a bracelet to match. Too fancy. She had nothing of Lulu's style and taste, poor girl. Always looks like a hick, he thought, a village maiden.

"Come in and have a cigarette," she said.

"I'd better go downstairs," he said. "Lulu thought she heard the doorbell."

"It's not quite six yet," said Norma. "But maybe you'd better go and just see...."

He went on down, and in the big living-room he saw Biddy Hamilton sitting in a chair, all alone. Now, why did she come, he thought. You wouldn't think she'd want to visit the Awful Brophys. The gorilla.

She was, he thought, a remarkably attractive girl, very tall, with red hair that she wore brushed flatly back from her thin face and done in a funny little knob at the back of her neck; long blue eyes under straight sandy brows, and an air of almost insolent assurance.

"Hello!" she said. "I didn't mean to be so early. My watch was slow."

"You couldn't be too early," said Brophy. "I'll get you a drink."

"Two different maids brought me drinks," said Biddy. "But I refused. I didn't think it would be mannerly to sit here drinking alone."

"My presence makes it absolutely correct," he said. "Cigarette?"

While he was lighting it for her, a maid came in with a tray of cocktails, followed by another maid with canapés.

"Ah...!" said Biddy. "How beautiful!"

She helped herself to four canapés, and at once bit in two something like a tiny pie.

"Ho! she said, with pleasure.

The girl in my Party story could be her type, more or less, thought Brophy, sitting on the arm of a chair and watching her. She's been avoiding the man the hostess wants, but she loves him. Why has she been running away from him? Because she thinks he's guilty of—something? No. That's the pulp touch. It's got-to be more psychological. No, She thinks—

The doorbell rang, and a maid ushered in a couple Brophy had not seen before, a stout blonde woman in a tailored black linen suit, and with her a dark man, black eyes popping out of his head, a half-open, astonished mouth.

"Are you possibly Lulu's husband?" cried the blonde. "My dear, I'm thrilled! A real, live author, Froggy! I'm Billie de Paul, and this is my little playmate, Jack Lord."

Her exuberance was agreeable to Brophy. Cocktail in hand, she walked all round the room, looking at the pictures, her long, white jade necklace bouncing up and down on her plump bosom.

"I'm crazy about Art," she explained. "Whenever I go into a strange room, I can't settle down until I've looked at the pictures on the walls. Oh, isn't that utterly charming! Froggy, come here and look!"

"Later," said Froggy, in a deep mournful voice.

Then in came Mrs. Wylie and one of her daughters; the young man who ran the lending library in the village came, an old, old couple from the neighborhood, a lively young girl, escorted by a boy, a tall, bony woman in a black hat with a peaked brim that almost touched the bridge of her hose, a fattish young man in a short-sleeved yellow shirt and no jacket.

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, Brophy counted. Well, that's something, anyhow. Only, what's the matter with Lulu? Why doesn't she come down? And where's Norma? The party was getting on very well, making a good, cheerful noise; nobody was left out, or sitting in a corner; plenty to eat and drink. But he was uneasy at Lulu's absence.

"Where's Lulu?" Billie asked him, three or four times, and, a little later: "Suppose I just scamper upstairs and drag her down?"

"No!" said Brophy, hastily. "It's—probably a long-distance call. She'll be along in a few moments."

She was coming now; he could hear the sharp tap of her heels on the stairs; she was coming fast, too, faster than he ever heard her come. She almost plunged into the room.

"Billie!" she cried, in a sort of scream. "And Froggy!"

She snatched a cocktail from the maid's tray, and swallowed it, and hurried forward, both hands outstretched.

"It's been such ages!" she said, in that same high, loud voice. "Tell me everything—about everybody. Maid!"

She took another cocktail, and stood there between Billie and Froggy, and Brophy thought she had never looked better, never had been more chic. She wore a new dress, of thin black material, with narrow white ribbons threaded in and out round the neck; sandals of crossed black ribbons; her shining black hair was waved close to her fine little head; her dark eyes were brilliant.

He waited, reluctant to interrupt her talk, but at last he felt obliged to go to her side, and touch her arm.

"Better say hello to Mrs. Wylie and the others," he murmured.

"The hell with them!" she said aloud, and did not move, or even turn her head.

"Lulu... The Jobsons are here—"

"Let me alone!" she cried. "You go and talk to them. These are the only people I want to see."

She staggered a little, and caught Froggy's arm to steady herself.

"Jimmy...," said Norma's voice at his side, very low. "Perhaps you'd better—let her alone."

He turned, and at the sight of Norma's face his brows drew together. "What's the matter?"

"I don't quite know.... But she's—so keyed up.... If you could just get her not to drink any more, Jimmy."

"She never drinks much. You know that, Norma."

"Yes. But... She had a bottle—an opened bottle of whiskey on her dressing-table, Jimmy. I saw it when I went to tell her to hurry."

"She was pretty nervous about this party," he said. "Maybe...."

Mrs. Wylie had come up to Lulu.

"Good-night, Mrs. Brophy," she said, very distinctly and very frigidly. And no wonder, thought Brophy. Lulu had not spoken to her, or even once glanced at her.

"Don't go now!" she said, loudly. "There'll be a crowd of people coming out from New York any moment, and I want you to be here."

"I'm sorry," said Mrs. Wylie, "but we really can't stay. Good-night!"

"All right then!" cried Lulu. "Get-out, and stay out!"

The elderly Jobsons now approached, obviously nervous.

"I'm afraid—," Mrs. Jobson began.

"No!" said Lulu. "I don't want you to go now."

"But I'm afraid—"

"No!" cried Lulu. "Go and sit down and have another drink. I want you to wait."

They retreated to a corner, where Mrs. Jobson sat in a big, high-backed chair, and her husband stood beside her; they shook their heads when drinks or appetizers were offered to them.

"We might sit down ourselves," said Lulu. "Come on, Billie and Froggy."

She started across the room, glass in hand, and no one could fail to see how she staggered. She half-fell onto the sofa where Biddy Hamilton was sitting.

"Move, will you?" said Lulu. "Sit somewhere else. I want my friends here."

"All right!" said Biddy, amiably, and picked up a glass from the coffee table.

"That's my glass!" said Lulu. "Put it down!"

"All right," said Biddy again, and taking the other glass from the table she moved leisurely away, followed by the fattish young man in the sports shirt.

"She's a bitch," said Lulu, for anyone to hear. "Look at her! If she can't get a real man, she'll take—"

"Lulu!" said Brophy.

"Shut up!" she shouted, and kicked him on the shin, hard.

He stepped back, out of reach, and tried to think of a way to end this. I can't carry her away, he thought, and I'm not going to leave her here. I don't know.... My God! I don't know what to do. A maid came up to her.

"New York on the telephone, madam," she said.

"I'll take it!" cried Lulu. "Tell them—I'm coming!"

She could not get up until Froggy helped her; when she tried to cross the room, Brophy took her arm. She pulled away from him, and fell on her knees.

"Get out!" she screamed. "Let me alone!" -

Biddy Hamilton took one of her arms and Brophy the other; they got her on her feet, and out into the hall. Norma was waiting there.

"My call! My New York call!" she shouted. "Let me go!"

"Take the call in your room, Lulu," said Norma, and in a whisper, "Can you carry her up, Jimmy?"

She struggled frantically in his arms; she screamed and swore at him; she began to claw his face, and he hitched her up over his shoulder and began to mount the stairs.

He wondered if Biddy were still in the hall; maybe there were other people, too, watching.

"Lulu...," he kept saying to her, in a whisper. "Take it easy, Lulu."

HE carried her into the bedroom, and when Norma had followed them inside, and shut the door, he set Lulu down and turned the key in the lock. She rushed at him, and he dropped the key into his pocket.

"Don't," he said, absently, watching Norma take the bottle of whiskey from the dressing-table and lock it in the closet.

Lulu stood turning her head, her eyes glaring; then she ran lurching over to the telephone, and, trying to lift the transmitter, she knocked the instrument to the floor.

Norma picked it up, and Brophy caught his wife as she reached an open window,

"Norma," he said, "call Doctor Griffin."

"Oh, Jimmy, no! Let's not get anyone else into this. It's bad enough."

"She ought to have a sedative, something. She's... Maybe it's the D.T.'s."

"People don't get D.T.'s unless they've been drinking a long time, Jimmy."

And has she been drinking a long time? he thought. Was that the cause of her hysterical outbursts? He had never seen a whiskey bottle in their room before; he had never noticed any smell of liquor about her; he had never known her to take anything more than two cocktails before dinner, or at a party. But he had heard about the slyness of secret drinkers.

"Get Doctor Griffin, Norma," he said. "This might be serious."

He and Norma had both become curiously numb to Lulu's screams and struggles. Brophy held both wrists in one hand; she tried to kick him, but she could not, and he no longer heard anything that she screamed at him.

"Jimmy, no! Jimmy, let's wait, and see if she doesn't quiet down."

"No. Call him now, Norma. She'll exhaust herself—to the danger point—like this."

"Jimmy, please! Jimmy.... He might—send her away."

"What d' you mean?"

"She's been so—so queer, lately. Oh, Jimmy. Give her a chance! She's had—so much trouble in her life."

"What d' you mean?" he asked, again.

"Just wait, Jimmy, and see if she doesn't—quiet down."

"Norma," he said, holding fast to the struggling, screaming creature, "she needs medical attention. She's—"

There was a violent drag on his,hand; Lulu had sunk to her knees. He raised her, and she was limp, her eyes half-open.

"You see!" cried Norma. "She'll go to sleep now, Jimmy. This is all she needs."

He laid her on the bed, and stood looking down at her.

"I don't know...," he said. "She looks—I don't like her color. I'd rather call in Griffin."

"Oh, Jimmy, don't, please! She'd hate it so. I can look after her now. I've done it before."

"You've—seen her like this before?"

"She just needs to be let alone for a while, Jimmy. Shell wake up in two or three hours, and I'll give her a glass of milk, and two pills."

"What pills?"

"Sedatives. Then she'll go to sleep again, and it'll be a good, restful sleep."

"Norma, d'you mean that she—she often...?"

"Not often," said Norma. "Leave her with me now, Jimmy. Hadn't you better go downstairs and see—if everyone's gone?"

He stood silent at the bedside for a time. I can't do it, he thought. But he had to do it. Perhaps they were all still there; perhaps more people had come, and they would all be eating and drinking and laughing, and whispering about Lulu.

Lulu's got allergic to alcohol, he thought. That's what I'll say. Just within the last few weeks. Can't touch it without bringing on one of these attacks. The thing is, that she couldn't quite believe it, and this afternoon, she was so pleased to see everyone....

That was the best he could think of; he unlocked the door and went slowly along the hall, elaborating his story. She'll probably be laid up now for two or three days, after just those two cocktails. The lucky part is, she won't remember a thing. If anyone calls her up tomorrow, say what a—good time they had ...

If I say that, he thought, then maybe some of them will call her up. That would help her. But maybe she will remember. Some of it, anyhow. Poor girl! Poor devil!

As he went down the stairs, he heard no sound of voices; when he came to the doorway, he found the living-room empty. The windows were open, and the flowers in bowls and vases stirred in the light summer wind. Everything was in order; the plates and glasses removed, the ash-trays emptied; each chair and table in its proper place. The party's over, he said to himself, with a sigh of relief.

The Party Is the Pay-Off, he thought. I'll have to have a scene at the end of that, of course. Dramatic. But I'm going to keep it a little understated. It'll all be there, hatred, violence, shock—

Why, shut up! he cried to his own mind. This is no time to think about your damn story. The real thing that's happened here is a tragedy. That's no exaggeration. I don't know how Lulu'll get over it, poor girl. Maybe other people came—

Their own housemaid, Regina, had come up behind him.

"Excuse me, sir, but will there be anybody extra for dinner?"

"No...," he answered. "Mrs. Brophy's not well. You might take a tray up to her room for Miss Crockett."

"Then there'll be just yourself at the table, sir?"

"Only me," he said.

He went upstairs to knock at Lulu's door.

"Just a moment!" Norma answered; and presently when she said, "All right, now, Jimmy," he found that she had got Lulu undressed and into a pale-blue nightdress and bed jacket. She lay back against the pillows, her lashes inky-black, in contrast to her dreadful pallor, her mouth still a vivid red from her lipstick.

She doesn't look right, he thought. She doesn't look—real. He went over to her, and laid his hand on her chest, and he was glad to feel the very gentle rise and fall of her breathing.

"But anyone who's been drinking generally breathes heavily," he said.

"Not everyone, Jimmy. Try not to worry."

"Regina's bringing you a tray. After dinner I'll come up and stay with her, Norma, and you can get some rest."

"I'd rather stay with her tonight, Jimmy. You see, I—well, I've done this before, and I understand just what to do."

"Stay here all night?"

"Yes. You can sleep in your old room, Jimmy. If I should need you, I can get you in a moment."

"Thanks, Norma, but I'd rather stay with her."

The gold-shaded bedside lamp was turned on, but Norma stood outside its orbit of light.

"Jimmy," she said, in her quiet, even voice, "we've got to think of Lulu. And when she wakes up, I'm sure she'd rather—find me here."

You never knew about women, he thought. Never! Maybe when she wakes up, she'll be sick— wouldn't want me to see her. God knows.

"Suppose we just get Griffin to take a look at her," he said. "See if her—breathing is all right, and so on."

"Oh, think how she'd hate that! Jimmy, let's wait. We can call him first thing in the morning, if she isn't all right."

"You've seen her like this before?" he said. "I mean—so pale. I mean—this shallow breathing?"

"Yes."

"More than once?"

"Yes, Jimmy. More than once."

Of course, he thought, Norma could be wrong. Lulu might want it to be me here when she wakes up. But then she'll send Norma for me,

He went down to the dining-room and sat at the place that was laid for him. The dinner was excellent—bluefish, baked with anchovies—and he was a little ashamed that he had so good an appetite. Lulu never seems busy, he thought. You'd never know she lifted a finger. But she runs the house perfectly; all the meals are fine, and served on the dot; everything is clean and comfortable. Well, could she do that if she was a "secret tippler"? "More than once...," Norma had said. A bottle of whiskey in the bedroom; those hysterical scenes....

All right! he thought. If it is that way, something can be done for her. Maybe she and I could go away for a while, take a trip. Or move out of this neighborhood altogether and start all over again, somewhere else. That would be the best thing. She'll never be happy here again.

If she remembers. She's sure to know that something went wrong, and she'll want to know who was here. That would be of paramount importance to Lulu, sick or well. Out of the more than forty people she had invited, how many had come? Twelve.

Unless there were some more later, who went away when they heard something was wrong. She'd like to know if anyone else—especially those New York friends—had come. It would make her feel better, poor girl.

He did not like to ask the maid; nor the Jobsons. The affronted Mrs. Wylie had left while he was there; the scholarly library owner was out of the question, and he did not know the names of the lively girl and her escort, or the fellow in the sports shirt. He would not have wanted to ask them, anyhow. There was nobody but Biddy Hamilton, and somehow it seemed easy and simple to ask her,

He went, after dinner, to the telephone in the small library and looked up the number listed under her father's name. President of the local bank, Slowe Hamilton was, a benign and portly man with a handsome wife, two pretty daughters, and a handsome son. Brophy knew their house very well—from the outside; an old-fashioned sandstone house, like a little castle with two turrets, set well back from the street behind a wide lawn. Driving past it in the afternoon, he had seen people on the terrace that was decorated with massive stone jars filled with trailing ivy, or sitting out on the lawn in deck-chairs; one time, driving past it in the evening, he had heard someone playing a piano inside, had seen the ground-floor windows lighted, a light in one of the turrets. He imagined a family life, going on in there, old-fashioned, the mother taking the daughters shopping, two sisters on the window-seat in a bedroom, talking secrets, the father coming, home to a hearty dinner, young men in the evening, old-fashioned beaux, bringing a bunch of flowers, a box of chocolates. There was certainly nothing in any way old-fashioned about Biddy, but that was the way he chose to imagine the Hamiltons' life.

A maid answered the telephone.

"Will you ask Miss Biddy, please, if she can speak to Mr. Brophy for a moment?" he asked, and Biddy came, promptly.

"Sorry to disturb you—," he said.

"You're not," she said. "Anything but. Somebody else has just dropped in to teach me to play canasta. I don't know why I feel I have to keep on trying. I hate card, games, all of them."

"I can play Bingo," he said.

It was so easy to talk to that girl, who was so easy herself, so casual.

"I mustn't keep you from your lesson," he said. "I only wanted to ask if you'd happened to notice anyone else...? I mean, any more—guests, after I—went upstairs."

"No, I didn't," she answered. "But, you see, I left, almost right away. I asked the whole crowd over to my place. Some of them came, and some didn't, but anyhow we all went flocking out together,"

"Thank you," he said, and after a pause, "thank you."

"Well... Au revoir!" she said.

He went upstairs then, and knocked at Lulu's door. Norma opened it.

"Sound asleep!" she whispered. "Get a good night's rest, Jimmy dear."

He turned away, to the room where he had used to sleep, and he found the bed turned down, pajamas and dressing-gown laid out, slippers side by side. There were magazines and books on the bedside table, a thermos jug of ice-water, cigarettes, matches, an ash-tray. Norma must have done all this, he thought. The way Lulu used to do. Very kind of her.... But the comfort and peace of the room had no appeal for him now; he sat down in an armchair and lit a cigarette, and a black cloud of anguish came down upon him. Lulu will sleep it off, he told himself. She'll be all right tomorrow. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.... There's some poem like that, isn't there?

His easy-going optimism had left him; he could no longer think, This will pass, things will get better. If what Norma implied were true, if Lulu was, in fact, a secret drinker, things would, inevitably, grow worse. There would be more and more "scenes." I can't help her, he thought. I couldn't make her happy. I—couldn't even pretend ...

He could never again, he thought, take her in his arms without remembering the screeching, clawing hell-cat he had carried up the stairs. He put his hand to his cheek, and when he withdrew it, there was a little blood on his fingers.

All right, he thought. She wasn't herself. She didn't realize... You've got to be decent. You've got to have pity....

After a time, he went back to her room again, and again Norma opened the door. She was still wearing the fancy pink dress, but she had taken off her shoes, and her rich chestnut hair was disheveled.

"Still sleeping, Jimmy," she said. "Do try to get some rest."

She kissed him on the cheek, as she had done often before, a thistledown kiss. He patted her shoulder and went off, back to his room. He undressed and got into bed, he turned out the light and fell asleep at once.

The sun was up when he opened his eyes, and Norma had her hand on his shoulder.

"Jimmy!"

Her quiet voice seemed to him ominous.

"Is it—Lulu?" he asked.

"Yes, I'm afraid—"

"She's worse?"

"I'm afraid—"

He got up and put on his dressing-gown and slippers; he was in a hurry to get out, but Norma caught his sleeve.

"Jimmy, dear, before you go... Jimmy, she's—gone."

"Gone?" he repeated, and frowned, "Where?"

"She's dead, Jimmy."

That made him angry.

"I don't believe it," he said. "It's impossible."

"Jimmy, the doctor's here."

His frown deepened; he looked at Norma with a sort of stupid amazement. He felt stupid; not able to understand the words he heard.

"The doctor? You sent for the doctor—without calling me?"

"Jimmy, I wasn't sure. I thought perhaps I was."

"She got worse? But you didn't let me know?"

There were tears running down Norma's cheeks, but they did not move him at all.

"Why didn't you call me when she got worse?"

"You see—it wasn't like that. I went to look at her every hour or so—and the last time I looked—" A sob made her pause. "I was—afraid. So I called up the doctor."

"And not me. Why didn't you tell me?"

"I thought that if it wasn't—serious, after all—"

"All right!" he said, curtly. "Let me go, Norma. I want to see...."

The bedroom door was open, and standing by the window was a man he had never seen before, a tall, thin, black-haired young fellow with his hands in his pockets. He took them out as Brophy entered; he put on a grave expression, like a transparent mask over his cheerful, blunt-nosed face.

"Mr. Brophy? I'm Doctor Binder. I'm looking after Doctor Griffin's patients while he's away at the convention. This is a very sad thing, Mr. Brophy."

Brophy went over to the bed and looked down at Lulu. She's gone, Norma had said, and that was the right word. She was not greatly changed in appearance, but you could see that she had gone.

"Why should she be dead?" he demanded.

"Well, that's a question we can't answer. Mr. Brophy," said the young doctor. "Very sad thing, at her age. She came to see me twice, you know, about what she believed were heart symptoms. I strongly advised a cardiogram; but she wanted, to postpone it for a while. My examination, in the office, didn't point to anything very serious, but these cases—"

"She died of a heart attack?" Brophy interrupted.

He was being rude, and he meant to be. He didn't like this doctor; he didn't like anybody. He was hostile, and angry.

"And all that alcohol was the worst thing possible," said Doctor Binder.

"What d'you mean by 'all that alcohol'? You don't know...."

He bent over, and, as he had done before, he laid his hand on Lulu's chest. Her skin was cold. And there was a reek of liquor about her.

But it wasn't like that before, he thought, startled. Did Norma give her anything more to drink? He straightened up and looked at Norma, and he was angry at her, too. One of the shoulder-pads in the pink dress had slipped down her back, giving her a hunched, lopsided look; her thick hair stood out in a bush; her face was mottled by tears. He turned toward the doctor.

"Well?" he demanded. "What are you going to do about it?"

The doctor was somewhat disconcerted.

"I'm afraid there's nothing further I can do, Mr. Brophy," he said. "I'll make out a certificate, and—"

And that was all. He was going to walk off and leave Lulu—like that.

"Have you tried anything? Done anything to—to revive her?"

"Jimmy...!" said Norma. "Jimmy, dear...."

"The patient had ceased breathing before I arrived," said the young doctor, stiffly. "About two hours ago, I should say."

Brophy drew the sheet up over Lulu's face, and stood back, leaning against the wall with his arms folded, while Norma and the doctor went out of the room. She's dead, he said to himself. She died, and no one told me. They were in here together, those two, like two damn buzzing flies, and they didn't tell me. If I'd known... If we'd got a doctor earlier... A different doctor.....

It seemed to him that this death was his fault; the guilt of it made his heart like lead. If I'd stayed with her, myself..., he thought. Not left it all to Norma.

He heard Norma coming back along the hall, shuffling in her mules.

"I called Regina," she said. "If you'll get dressed now, Jimmy, we'll have breakfast."

"What? Just leave her here?"

"I've—made arrangements, Jimmy. The undertaker will be here at ten, to talk to you. And Doctor de Peyster, from St. Andrew's, a little later." He was silent for a moment.

"Norma, look here...!" he said. "I—if you wouldn't mind—I wish you'd—put some perfume on her."

"Perfume, Jimmy?"

"Yes. Sort of—sprinkle it around. The thing is—" He paused. "There's such a damn strong smell of—liquor."

"I didn't notice it, Jimmy. But anyhow it would evaporate, dear."

With an effort, he went over to the bed and drew down the sheet; he bent over the rigid little doll that lay there, all in blue silk and satin and lace.

"No!" he said. "It's enough to knock you over."

"But I don't think perfume—" Norma began. "I think that would be worse."

He went to the dressing-table. There was an empty atomizer there and beside it a tiny bottle labeled Amour du Diable. He took out the stopper and sniffed it, and it seemed to him overpowering and horrible. But Lulu knew about those things; she always bought the best. He filled the atomizer and brought it to the bedside; he sprayed her hair, her neck, her nightdress, the pillow.

"Jimmy!" cried Norma. "Oh, don't! No more!"

The whole room was filled with the intolerable perfume; it was like a mist, like the smoke of some ancient erotic incense. A wave of nausea swept over him; he put his hands into his dressing-gown pocket, so that Norma should not see them clenched.

She drew the sheet over Lulu again.

"Jimmy, you'd really better get dressed now," she said, and for the first time since he had known her there was a kind of coldness in her tone.

All right! he said to himself. All right! I don't like the idea of this—undertaker fellow finding the room like this any more than she does. But it's better than the other.

He went out of the room reluctantly, and in his dazed mind was a feeling that some monstrous wrong had been done to Lulu. Why should she be dead? he kept asking himself.

HE had breakfast alone with Norma, and Regina waited on them, sniffling, giving a suppressed sob from time to time.

"She must have been fond of Lulu," Brophy said, when the girl was out of the room.

"I don't think so," said Norma. "It's just a servant-girl theatricalness."

Brophy did not agree. Thin and flat-bosomed, with pale, dust-colored hair, a pale face with a big bony nose, Regina seemed a creature without age; you could, thought Brophy, easily imagine her going off to school, in a middy blouse, and dark skirt, and long black stockings, with this same face and figure and hair. But she had always seemed to him entirely honest and guileless. When she broke anything, she had come to him, or to Lulu, weeping, making no excuses. I dropped it. I knocked it off the table.

She was fond of Lulu, he thought. And who else?

"We ought to send telegrams," he said.

"I telephoned a notice to the New York papers," she said, "and the local paper."

Her chestnut hair was smooth now; she was pretty again, in a black cotton dress with a white embroidered collar.

"Thank you," he said. "But aren't there any relatives?"

"No," Norma answered. "None that she'd want here. And her friends will see the notice in the newspapers."

She was distrait this morning, exhausted and hollow-eyed; she was strange, as everything else was strange, and unreal. She went off to the kitchen after breakfast, and Brophy did not know where to go, or what to do with himself. He had put on a dark suit, too heavy for the warm weather, and a black tie, left over from a war-time funeral; he felt clumsy and foolish, entirely at a loss. It didn't seem right, he thought, to read the newspaper; he walked up and down the sun-porch, hands clasped behind his back, until the undertaker came."

Caulish, his name was, and he was a very decent fellow, quiet, serious, with none of the maudlin sympathy Brophy had dreaded.

"Miss Crockett tells me that Mrs. Brophy wished to be cremated," he said.

"Well... Brophy said. "I don't know. We never discussed it."

"I suppose her sister would know."

"Yes...," Brophy said.

"At three o'clock tomorrow afternoon, isn't it?"

"Tomorrow? Too soon," said Brophy.

"I understand that's what will be in the newspapers, Mr. Brophy."

Norma's taken too damn much on herself, Brophy thought, with a flash of annoyance. But it passed off at once, and he felt a little ashamed of it. After all, he thought, I didn't do a thing, didn't make a move. And somebody had to take charge.

"Miss Crockett tells me you want everything very simple, quiet," Caulish went on. "She mentioned a sum.... I don't like to mention it now, but it's always better, Mr. Brophy. Better for the family to know exactly—"

"What sum?" Brophy asked. ,

"Miss Crockett said five hundred dollars."

Brophy had no idea whether that was a high price, or a low one, or simply average. Better leave it to Norma, he thought.

"Yes," he said.

Then, for the first time, he began to think about money. He did not like it; it seemed a sort.of cruelty to Lulu. He knew, of course, she had an ample income; the house was in a good neighborhood, there were always two servants, the food and the liquor were of the best quality; she had plenty of money for clothes, anything she wanted. He had known, from the beginning, that she had much more than he had ever earned, and he had been glad of that; indeed, he would never have asked her to marry him otherwise. She couldn't have lived on his average of four thousand a year. Whenever he sold a story, he gave her a check, keeping out enough for his taxes, his clothes, his small personal expenses.

"Someday you'll make a fortune!" she used to say. "You'll write a bestseller."

She had, he thought, been extraordinarily tactful and decent about money matters. No matter what "scenes" they had had, they had never been in any way connected with finances. He had never asked her for money; he had had enough of his own to buy what he needed, and he had felt independent. Only now, after Caulish had gone, did he face the situation squarely.

She supported me, he said to himself. My God! And she's probably left me money—a lot, maybe. I can't take it. I've been... My God! A kept man.

And why did I ever get married, anyhow? I didn't mean to. I'd made up my mind I never would. I suppose that was because of my parents. They didn't give me a very rosy view of—domestic life....

His father had been a captain in the Merchant Marine, on the South American run; he had been away eight weeks at a time. His mother had been a stylist in a department store, a tall, handsome, full-bosomed woman; she had made a good salary, she had a lot of friends. They had both been kind to him, and interested in him, nice people; he still didn't know why they had not liked each other, why they had lived apart and never seen each other.

Well, it didn't matter any more. Only that now, when he tried seriously and honestly to examine his own marriage, he could understand it. He had found Lulu attractive, but not more so than a dozen other women; he would never have thought of marrying her if he had not come here for those weekends.

And that, he had thought, was Home. The order, the grace, the quiet, the companionship—when he wanted it—of the two pretty, cheerful women.

If she's left me enough money, he thought, I could keep this place on; I could work here; I could ask Matthews to stay here. No!

He walked up and down the sun-porch, up and down, sweating in his heavy suit, trying to think things out, trying, in his fashion, to think out himself. Some writers, as he well knew, were autobiographical; they could look inside themselves and dredge out a passion, a grief, a joy; the heroes in their books were themselves, and the villains but another facet of themselves....

But Brophy knew little or nothing about himself. He was purely and simply an observer. He was interested in other people; he noticed how they acted, how they talked; in his writing, his characters had an excellent appearance of being real. But they haven't any insides, Matthews had told him. You've never even tried to understand what makes people tick.

It's true, he thought. I never understood Lulu. Did she—love me? And did I love her? Ever?

Regina came to the doorway.

"Doctor de Peyster's here, sir, and Mr. Jones."

Oh, Lord! thought Brophy, in a panic. Doctor de Peyster was the clergyman who had performed the marriage service for Lulu and himself; he had made little impression then upon the nervous bridegroom, and he had, since then, become obliterated. I don't know how to talk to a clergyman, he thought. He'll—I suppose he'll try to comfort me, and all that.

He felt obliged to go into the living-room, though, and there he found two clergymen, standing side by side, one small and elderly, with a thin and fine-cut face, the other taller, a weedy young fellow.

"Mr. Brophy," said the older man, "this is my curate, Mr. Jones."

Mr. Jones took Brophy's outstretched hand in a limp grip.

"Miss Crockett telephoned me this morning," Doctor de Peyster went on. "She asked me to conduct your wife's funeral service, and, naturally, I assented. I did not know, at that time, that it was to be a cremation."

"I see ..., said Brophy.

"I am sincerely anxious to avoid bigotry in my form, Mr. Brophy, and I can assure you I have given the matter long and serious study. I can come to but one conclusion. The burial service established by the Episcopal Church is not and cannot be adapted to cremation. Moreover, a conscientious reading of the Scriptures confirms my view. I cannot officiate at this cremation, Mr. Brophy."

"I'm sorry," said Brophy. "We can change it, then, to—"

"Miss Crockett assures me her sister was very strongly in favor of cremation. Very strongly. She had, in fact, exacted a promise from Miss Crockett to see that this wish was carried out. Had she—expressed this wish to you, Mr. Brophy?"

"We never talked about it," said Brophy.

"No? That's rather unusual, I think. Most of us, I think, take an interest in deciding upon our final resting-place."

He went on, and Brophy tried to listen.

"My young colleague, however," said Doctor de Peyster, "doesn't see eye to eye with me in this matter, and he will, if you wish, conduct the services tomorrow afternoon."

"Oh, thanks!" said Brophy.

"I wanted, however, to come and explain in person to you and to Miss Crockett my reasons for not fulfilling her request. If you'll extend her my deepest sympathy...?

"Oh, I will!" said Brophy, and shook hands with him and with Mr. Jones. As he went to the door with them, he realized that he had not asked them to sit down; the serious conversation had been conducted standing. Damned oafish! he called himself, displeased.

He and his mother had always lived in second-rate hotels; he had gone to boarding-school at an early age, and to summer camps; he seemed out of place in a house, a home. Mine? he thought. Well, I don't want it. I'll sell it.

They took Lulu away; he heard the men go upstairs, and then he went into the library and shut the door; he heard them come down again, slowly. Poor girl! If I'd stayed with her, if I'd got a doctor earlier....

There was a knock at the door, and he opened it.

"Jimmy," Norma said, "do you mind having lunch alone, dear? Because I—think I'll take a nap."

"Of course!" he said. "Only—"

She gave him a smile, and turned away, but he put his hand on her shoulder and turned her back.

"Norma...," he said. He found no right words in his mind; he used what came naturally. "Norma, you look like hell."

"I'm tired," she said. .

She looked as if grief had clamped a brutal hand against her face, bruising her healthy and delicate skin; there were deep purplish rings under her eyes, the lids were discolored and half-closed, her lips were parted as if it were difficult to breathe.

"You shouldn't stay alone," he said.

"I want to. I must."

"Norma... Doctor de Peyster told me to give you his—deepest sympathy. Norma, d'you want him to come back and—talk to you?"

"No. Nobody. Please."

He let her go then, but without knowing whether this was right or wrong. Her face haunted him; he closed the library door and lit a cigarette, and he felt ashamed of this. His chief and overwhelming-emotion was this miserable shame; he was ashamed that he did not feel more grief, more sense of loss, ashamed that he enjoyed his cigarette, that he felt a certain hunger for his lunch.

Above all, he felt ashamed that he should profit by Lulu's death. I hope to God she's left everything to Norma, he thought. But he knew it couldn't be so; the husband had some sort of legal right or share. I don't want anything! he cried to himself. As soon as I can, I'm going to get out of here. Out of this house; out of this town. I don't want anything, not a damn cent.

Little as he liked to face it, he knew why. It was because he had not loved the dead woman. He had never understood her, or tried to do so; even his lovemaking had had a casual quality. Like a sailor in a strange port, he thought. Sometimes when he sat here, in this very room, reading, she would come down the stairs in a gauzy negligee; she would put her arms round his neck, there would be the scent of some new perfume....

Perfume...! he thought. I hope that perfume I used on her did the trick, so that the undertaker and his men didn't notice—that other. But I can't understand it. When I left her, when she was asleep, there wasn't that smell of alcohol on her. I know that, I could swear to it. But when I came back, she was reeking of it.

All right! She got something more to drink, after that time I saw her asleep. It's got to mean that. Well, how? Maybe she got up when Norma was asleep and found the bottle in the closet. That could happen. Or maybe Norma left her for a few moments, went to get something from her own room. However it was, however it happened, she got some liquor. And maybe that was the last straw. Maybe that was the pay-off.

The Party Was the Pay-Off. Shut up! Never mind about your damn story now. The thing is, if I ought to tell the doctor? All right; why? Lulu's dead. Any sense in suggesting that Norma slept through her getting up, or left her for a while? When Norma did—what I ought to have done. Stayed with her. And I went to bed, and slept. Like a hog.

A gorilla, Biddy Hamilton had called him.

"Lunch, sir," said Regina, with a sort of scratch at the door.

It disturbed him to see the table spread with a linen cloth, a bowl of flowers in the center, the usual silver service at this place. These were Lulu's things, she had provided them; it seemed to him wrong and petty to be using them; to be sitting here alone in luxury, gross to have an appetite for the meal before him

"Mr. Melton's here, sir," said Regina,-in a whisper.

"Who's that?" he asked.

Her eyes filled with tears of embarrassment and distress.. "It's him—it's Mrs. Brophy's—first, sir," she answered.

"Oh, yes!" said Brophy, as embarrassed as she was. He knew the name, of course, he had heard it often, had seen it written in books and so on. But Lulu had resumed her maiden name after the divorce; he had never heard her called Mrs. Melton, never had thought of her so. I don't want to talk about him or about our three miserable years of marriage. It was a mistake; we ought to have known from the first time we met that we could never, never get on together.

Norma had been more talkative. Just the sight of them together was enough, she had told Brophy. Gilbert was so gross-looking and Lulu was so delicate. No, I never liked Gilbert. He was always trying to "kid" me as he called it, and I—wasn't amused.

What's he come out here for, Brophy asked himself. It seemed to him that politeness, or correctness, required that he should go out to meet this unwelcome guest in the living-room and not eat lunch in his presence, or invite him to partake. He had not finished his meal; with great reluctance, he pushed back his chair and rose.

I don't think the fellow's "gross-looking," he told himself with a certain surprise. On the contrary, he thought Melton remarkably handsome, tall, a little heavy about the chest and shoulders, with neat silver hair and a ruddy face. Type I'd use for a millionaire yachtsman. I'd make him the trustworthy type; a gentleman.

"Mr. Melton?" he said.

"And you're Brophy? I've heard about you—read some of your stories."

Certainly there seemed nothing in the least hostile about Melton, no sign of the jealousy he might have shown toward a man considerably younger than himself,, who had supplanted him with a possibly much regretted woman.

"If you have no objection, Brophy," he said, "I'd very much like-to—attend the ceremony tomorrow."

"Well, you see," said Brophy, rather at a loss, "I've left things pretty well in Norma's hands... I mean to say—"

"Oh, she won't want me," said Melton. "But she'll be reasonable, Brophy. And if you don't object—"

"No—"said Brophy.

He was not entirely sure how he felt about this. It might, he thought, be a little unseemly, even ludicrous, to see two husbands at Lulu's funeral....

"And now that we're alone, for the moment...," said Melton, lowering his voice, "I'd like to speak about the financial set-up, Brophy."

"I don't know anything about it," said Brophy. "I don't know what Lulu had, or how she's disposing of it."

"She didn't have anything but her alimony—"

"Alimony!" cried Brophy.

Melton paused a moment, obviously ill-at-ease.

"She—well, she certainly gave me to understand that you—well, understood the situation. I mean to say, legally, of course, the—the alimony would stop when she remarried. But she asked me—she explained the situation.... She said you intended to pay back every penny, when the book came out."

"No," said Brophy, and walked over to the window, stood there looking out over the smooth lawn, at the road where cars went by in a stream, at the tree-shaded street that ended before the red-brick public library. I've been living on this fellow's money, he thought. That's the hardest thing to take....

"Lulu wrote about you, several times," Melton went on. "Said you were very generous to her with whatever you did make. And she seemed to feel sure that this book you're writing would make a fortune."

"What book?"

"Afraid I don't know the details, Brophy. But some new book you're writing."

"I don't write books," said Brophy. "Just serials and shorts, mostly for the pulps."

"Pulps.... Ah, yes!" said Melton, obviously entirely at sea. "Very interesting, Brophy. In the meantime, I'd be glad to—to share the—extra expenses—"

"No, thank you," said Brophy in a louder tone than he was accustomed to using. He had never felt so utterly sunk and depressed.

"No...," he said. "As soon as the funeral's over, I'll leave here. Tomorrow."

"But, my dear fellow! You'll need to see about subletting the house. And moving out Lulu's things."

"I'll find someone to arrange all that."

"Tell you what," said Melton. "Billie de Paul's very good at that sort of thing. If she's still here in the house—"

"No. She went home yesterday, after the—party."

"She was here this morning. Called me up from here."

"Not here. Not in this house."

"Well, she said so. Called me at some unearthly hour, before it was daylight. She was the one who told me about the—tragedy. Said she was calling, from your house."

"She wasn't," said Brophy.

"Told me she came back after the party. Said she was worried about Lulu, wanted to talk to you. But she said she found you—sort of tied up with some girl, so she waited out on the sun-porch, and presently she fell asleep, and when she waked, you'd gone upstairs. She said she didn't feel in any shape to drive herself back to New York that night, so she went into the kitchen and got herself a snack, and went back to sleep until this morning."

"She says she was here in the house all night, and no one saw her or heard her? The doctor coming in and out, and Regina—That's hard to believe."

"It's been done, Brophy."

"Yes. I've used things like that in stories. But this girl she says I was 'tied up with'... Does she mean Norma?"

"Lord, no! If she'd meant Norma, she'd have said so. No.... Billie's one of the best; very fond of her. But she's certainly outspoken. Maybe a little too much so. Well..." He paused, and glanced at Brophy sidelong, a glance Brophy could not read. Was it reproach, or was it a sort of pity?

"Want the picture in Billie's own words?" he asked. "A snooty red-headed bitch—"

"All right!" said Brophy curtly. "I wasn't 'tied up' with anyone, and I don't believe the de Paul woman was here all night. It doesn't matter, anyhow:"

"You're right!" said Melton, earnestly. "It doesn't matter. Well, Brophy, I'll shove off now. And with your permission, I'll see you tomorrow at the—"

"The ceremony," said Brophy. "You'd better get in touch with Norma about the details."

"I'll do that, Brophy. And later, perhaps, we can discuss... eh?"

"Thanks," said Brophy.

From the open doorway he watched Melton climb into a fabulous roadster, with a chauffeur at the wheel, and go spinning down the drive. I've been living on his money. Alimony....

He went to the telephone and called Matthews' number. An understanding sort of fellow, Matthews was, an old and greatly valued friend, a commercial artist.

"Find me a room—a cheap one—for the day after tomorrow," he said. "Or, if you can't, let me stay with you while I look around."

"Sure," said Matthews. "But—anything wrong, Jimmy?"

"Plenty," Brophy answered. "I've got to get out of here."

NORMA came down to dinner, and it was an ordeal. She made an effort to talk; Brophy made an effort to respond. But he could not endure the sight of her stricken tear-stained face.

"I thought we'd have the service here, Jimmy, instead of in the church," she said. "I was sure you wouldn't mind—and I think Lulu would like it better."

"Oh, yes! Certainly!" he said.

"It'll be at half-past two," she went on. "They'll bring Lulu here at one—so that everyone—can see her."

"Norma...," he said. "Try to take it a little easy, dear."

She tried to smother her sobs with her napkin.

"I want—I want everything—to be as lovely—as possible. For L-Lulu."

"I know it, dear."

"There are a few people—from New York. I've asked them—to an early lunch—so that they—can see Lulu...."

"That's—very nice. Very thoughtful."

"And Gilbert. You don't mind, Jimmy?"

"No. Only, who's Gilbert?"

"Gilbert Melton. Oh, Jimmy, I haven't hurt you, have I? Have I, Jimmy?"

"No, no!" he protested. "No, Norma, you haven't."

But she was sobbing so desperately that he got up and went round the table to her; he put his hand on her shoulder and she laid her cheek, wet with tears, against it.

"Jimmy...," she said. "Did you love Lulu—very much?"

"Look here!" he said. "I don't think this sort of talk is good for either of us, Norma."

"But I—I must know that. If you—loved her—very much."

"Certainly," he said.

And what is love? he asked himself. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know why I married her. I was attracted by her; I liked her. But—all right. What really got me was her way of living. I liked coming here more than I'd ever liked anything. The peace and quiet that I had for working. Then; not afterward. The house seemed to me the way a home ought to be. Everything cheerful and cozy, everything running so smoothly. I thought it was what I'd been wanting, all my life.

Yah! Poor, lonely young fellow, weren't you? Wanted a home, and probably kiddies, did you? So you married a woman who certainly wasn't likely to have kiddies, and you lived in a home that was paid for by another man's money. And you didn't do this wonderful work you thought about. Three stories to the slicks, in two years. Otherwise, the good old pulp stuff. "Death Shakes the Dice." "Murder Wears a Muffler." All done on alimony. O God...!

"Jimmy... I ordered flowers. Beautiful flowers...."

"Norma, let's not talk any more. I—let's not. Have you got anything that will help you to sleep?"

"I don't want to sleep, Jimmy. I want to give this night—to Lulu."

"Norma, that's—I mean, it can't do poor Lulu any good, and—"

"How do you know it can't?" she asked, raising her head. "How do you know she's not here with us now?"

He had a hard time to get her up to her room. Then he went to the bathroom he had shared with Lulu, and opened the cabinet, to look for some kind of sedative. He had opened that cabinet at least once, and usually twice every day for over two years, but always casually, to get out his toothpaste, shaving lotion, iodine for a cut, perhaps. He had never before really looked at it. And now, when he did, he felt a slight shock. The four glass shelves held row after row of bottles, liquids and pills of varied colors, vivid greens, ruby red, bright-yellow capsules and bright-blue ones. Almost all of them had prescription numbers, from Larsen in the village; many of them had blue stickers. This prescription cannot be repeated, or a copy given. He saw labels that read: One teaspoon at bedtime. One capsule at bedtime. Sleeping stuff, he said to himself, in deep distress.

He had friends, fellow-writers, who took goof-balls, got them in the black market at fantastic cost. He had often enough argued with them. Those things slow you down, he would say. Better to stay awake all night. Maybe you're all right now, but in the end, they'll catch up with you.. Sure as fate.

He looked at all those bottles. He remembered the nights when he had stayed downstairs to work, and then come up, never very late, to find her sleeping so soundly she did not hear him when he came in, did not stir when he got into bed beside her.

Dick Johansen committed suicide with those damn pills, he thought: And Alice Baker.... They saved her, the first time she tried, but the second time she brought it off. I don't know why. She was a pretty girl, with lots of friends; she made plenty of money; she had Charlton waiting to marry her... I don't understand these things. Taking drugs, killing yourself. I couldn't write a psychological novel. I wouldn't know how to motivate my people. I'm too healthy. Or maybe too dumb.

He closed the cabinet. Nothing there for Norma, he thought. Well, I'm sorry. I didn't realize how much she cared for Lulu. He went downstairs and poured himself a moderate drink of whiskey; then he went up again, to that old room he had used to have; he undressed and got into bed. All those damn bottles..., he thought. If Lulu-had kept away from doctors, and drugs....

Had she—taken something, last night? Or was it just liquor? The doctor would have known. Almost every drug has pretty definite symptoms. I know that. I've used a lot of them in stories. I've looked them up. Poor girl! Poor Lulu! I never knew she had a bad heart. I thought—well, to be frank, I thought she was pretty much of a hypochondriac. I didn't listen very carefully to all her—symptoms....

He waked at seven, which was his habit, and went down to breakfast, served to him promptly by the still red-eyed Regina. I want to finish that story quick, he thought. I'll need the money.

He felt it would be improper to work in the sun-porch, where he could be seen; he sat in that guest-room, and so well did the writing go that the. time flew past.

"Lunch is served, sir," said Regina, knocking at the door.

He made haste to wash and comb his hair, and go downstairs. And what he saw dismayed him. The two big living-rooms were filled with white flowers, masses of them; he had never seen so many. At one end of the front room was a sort of bower, and there she would lie, he thought.

Norma was there, in a sheer black dress; Melton was there, and two people he didn't know.

"Mr. and Mrs. Revell, Jimmy," Norma said. "Old friends of Lulu's."

Mrs. Revell was a thin woman with a blotched face and fair hair worn very long; her husband was big and burly and bald, and the marks of dissipation were on them both. They all followed Norma into the dining-room; they sat at the table in pompous silence, and the air was heavy, almost sickening with the perfume of the white flowers. I suppose it's the heat, Brophy thought. Even if I don't pay the rent. But not a word came into his head. Melton and Norma were the ones who carried the burden. Melton said it was a sultry day; Norma said the farmers needed rain.

"What do they grow around here?" Melton asked.

A car was coming up the drive; in a moment the doorbell rang, and Regina went to answer it. She came to Brophy's side, and leaning down, she whispered :

"It's the police, sir."

Brophy pushed back his chair and rose.

"Excuse me just a moment...," he said, and went into the front living-room.

Doctor Griffin, whom he knew well enough, was there; a portly little man with a high crest of gray hair, like a cockatoo, and somewhat the figure of one, with his chest thrust out, his short legs and in-turned toes.

"Here's Lieutenant Levy," he said, in his irascible way. "Horton County Police. We've come to stop this funeral, Brophy."

"Now, just a moment...," said the man with him, a tall and lean young man, black-haired, with a big nose, big ears, big hands.and feet. He was, Brophy thought, like an Egyptian monarch in some ancient frieze, but his long, dark eyes were gentle, his voice was mild. "We're very sorry to intrude just now, Mr. Brophy, but Doctor Griffin has lodged an objection against Doctor Binder's—certificate and we're obliged to investigate."

Doctor Griffin had lost every trace of bedside manner; he was bristling.

"Binder certified that Mrs. Brophy died of endocarditis. I—" He checked himself, with an effort. "I have no wish to—belittle a colleague, but I am sure Binder was misled. The day before I left for the convention that is, exactly nine days ago—I completed a thorough check-up of Mrs. Brophy. There were no symptoms of endocarditis. A cardiogram showed nothing wrong with the heart. The circulation, blood pressure and so on were excellent. As soon as I learned of this certificate, I went immediately to the police."

"Doctor Griffin's our County Medical Officer," said Lieutenant Levy.

"I demanded an autopsy, before this woman was hurried off to be cremated. In my examination of her, exactly nine days ago, I found nothing, nothing whatever that might cause this extraordinarily sudden, death. I make no claim, mind you, to being one of your heart specialists. But neither is Binder. And I'd had Mrs, Brophy under my care for nearly four years. I know her condition."

"Then what do you think caused her death?" Brophy asked.

"Poison."

"What?" said Brophy. "What? You think someone—poisoned her?"

"Not necessarily," said Doctor Griffin, irritably. "She might very well have done it herself."

"Suicide?" cried Brophy.

"No!" said Doctor Griffin, angry now. "It's simply that Mrs. Brophy was very indiscriminate, very rash in her use of drugs. I've always been aware that, instead of keeping to the prescriptions I gave her, she was in the habit of visiting other doctors, quacks, charlatans, buying patent medicines. I don't know what she'd taken before this party—"

"I gave her some medicine," said Brophy. "She asked me for it."

"What medicine?"

"I don't know. A new bottle she told me to open."

"Let me see it."

"I wouldn't know it now from the others, now it's been opened."

"Let me see all the bottles you have."

"You're welcome to go upstairs and look in the medicine cabinet," said Brophy, curtly. "You know the way."

"You'll accompany me," said the doctor.

"No," said Brophy.

"We'd better all go," said the Lieutenant, amiably.

The doorbell rang, and Regina came hastening to open it; she admitted two women, all in black, and led them at once into the library. Brophy saw them standing there, surrounded by all the white flowers; he saw Norma come out of the dining-room to meet them.

"All right!" he said, quickly.

Half-way up the stairs he stopped Levy with a hand on his sleeve.

"Look here!" he said. "What am I going to tell all these people? What in God's name can I tell my sister-in-law? She'll be—I don't know how she'll stand this."

"I'll tell her, Mr. Brophy," said the Lieutenant.

"Couldn't we just have the ceremony—and then you could take her away.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Brophy, very sorry. But the deceased has already been removed to the hospital, and we couldn't take her out until after the p.m."

"This is a damned brutal thing for Griffin to do."

"It's no more than his duty, Mr. Brophy. Mrs. Brophy was his patient, and if he had reason to believe that the certificate issued was incorrect—"

"Brophy!" called Doctor Griffin.

He was standing before the open medicine cabinet, looking at the incredible bottles.

"Be good enough to identify the bottle from which you poured medicine for Mrs. Brophy," he said.

"I told you I couldn't," said Brophy.

"No wonder," said Levy. "Now, if you just have some recollection of the size of the bottle, the color of the liquid in it, anything like that, it might help us."

"It was colorless—like water...," Brophy answered, trying to concentrate. "At least, I think it was. What I do remember is, that it had a screw top—black—and I had to whack it against the basin a few times to make it turn."

Then he remembered something else.

"I chipped it!" he said. "If that's any help. I knocked a little piece out of that top."

Doctor Griffin was already examining the bottles, taking down one or two and setting them on the basin.

"Levy," he said, "I'll want all this trash—everything, without exception—taken down to the laboratory and analyzed."

"I'll see to it, Doctor."

Brophy looked at the Lieutenant with a certain exasperation. He's a booby, he said to himself. Nice fellow, very civil and all that, but he's letting that pompous ass of a Griffin run the whole show. It's Griffin that stopped the funeral,.Griffin that says it's poison; Griffin gives the orders.

"I'll be off now," said the doctor. "Calls to make. See you later, Levy."

He gave Brophy a curt nod, and went past them, down the stairs.

"My sister-in-law will have to be told," Brophy said. "And all the rest of them. It's—"...

"It is," said Levy. "I'll do it for you, if you want."

"But—how will you do it?"

"I'll find someone with authority, some sort of standing, and I'll tell him to get everyone out, quietly. I'll tell him the doctors have disagreed about Mrs. Brophy's heart condition, and that has to be settled before a certificate's issued. I'll make it very medical. Big words. Coronary occlusion. And nothing about poison."

"Thank you," said Brophy, after a long moment. "But I think I ought to do it myself."

"I see! I'd advise you, Mr. Brophy, I'd strongly advise you to say nothing—to anyone at all—about the theory that Mrs. Brophy may have taken something injurious."

"Why not?"

"That's my advice, Mr. Brophy."

"All right."

"And just a moment. Before you go downstairs, will you give me a list, or a partial list, of the people at the cocktail party?"

"The local people, yes."

Levy wrote down the names in a little book.

"Anyone else, Mr. Brophy?"

"There were two people from New York, but I don't know where they live."

"Their names, please?"

"There was a woman called Billie de Paul, and a man called—" He thought a moment. "Jack Lord."

"Thank you," said Levy, putting away his little book.

"When will you know about—my wife?" Brophy asked.

"Sorry, but I can't tell you. We might get a full report tomorrow, and it might be a week or more, if Doctor Griffin makes them analyze every tablet in an aspirin bottle."

"He's a damn bad-tempered pest," said Brophy. "What does it matter if the poor girl took some medicines that didn't belong together, or something of the sort? He might think a little about the living—about her sister, for instance.

"Mr. Brophy," said Levy, "everyone in a community can be thankful for a doctor who is vigilant."

There was a dignity in the Lieutenant that impressed Brophy, against his will.

"Sorry, but I'm not thankful for this fellow's interference," he said. "Well, I'll be going now...."

As he began to descend the stairs, it seemed to him that he could not do this, that it was beyond him. Find somebody with some authority and standing, to go around and tell people... ?

It occurred to him that Melton would be very good for this, but he dismissed the idea, a little shocked at himself. The perfume of the flowers reached him now; he heard a rustling and murmuring, as if from an enormous crowd. My God! he thought. If there is a big crowd—come to her funeral... And when she was alive, and wanted a crowd, at her party....