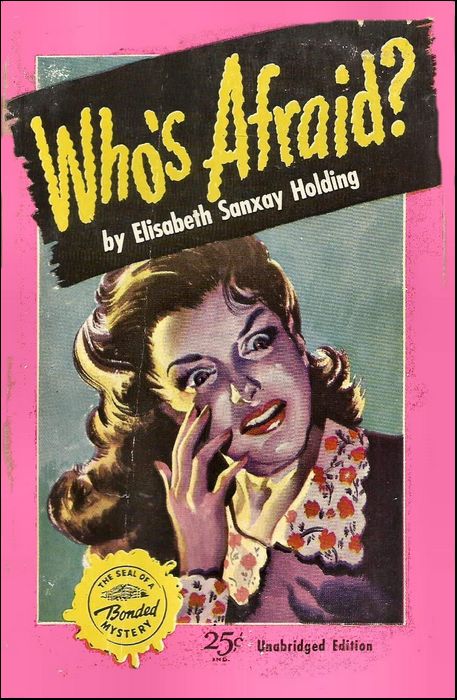

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Who's Afraid," Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York, 1940

"Trial by Murder," Novel Selections, Inc., USA, 1940

"Who's Afraid?" is a tightly constructed psychological suspense novel centered on Susie Alban, a young woman traveling through New England as a sales representative for Gateway's "culture program," a dubious charm-school-style enterprise.

What begins as an ordinary business trip quickly turns sinister. At her very first appointment, the husband of her prospective client reacts violently upon hearing the name "Chiswick," Susie's employer, and slams the door in her face. Later that evening, Susie discovers this same man's dead body on the path leading to her lodging house...

THIS is life! Susie thought, leaning back in the Pullman chair. She stretched out her long legs and crossed her ankles modestly, she looked with satisfaction at her new shoes. Nice shoes, she thought, and nice feet. Far from small, but narrow. Aristocratic, I dare say.

Mr. Chiswick had put ideas like that into her head. A month ago she had seen his advertisement in a New York newspaper.

Wanted: Young lady, with unquestionable social and cultural background. Experience not essential. Write stating qualifications. C. C. Box 907.

Bogus, she had thought; just another of those things, selling from door to door on commission.

But you never know. She had registered at three agencies, but they had told her July was a bad month, they said there were so many young people just out of college, and indeed she saw them with her own eyes. She had studied those other girls, her competitors, and sometimes she had been depressed. The little cute ones get the breaks, she thought.

She knew better than to make any attempt at cuteness. She was too tall for that, a thin young creature, limber and nonchalant, with a dark, serious, good-humored face. She had dressed as magazine articles advise applicants to dress: she had worn an immaculate white blouse, a black skirt, colorless nail polish; her hair had been neat. She looked all right; but so did practically everybody else.

Only Mr. Chiswick had found her superior. He had liked her letter, and he had arranged an interview, he had told her she was exactly the type he had had in mind. He was perfectly satisfied with her Social Background; a father who was a professor of English in a smallish upstate college, a grandfather who had been mayor of that smallish city. He admired her culture as no one else ever had. She had a good scholastic record, but nothing brilliant, no travel either; she had felt a little nervous when he had given her a list of names to read aloud.

Madame de Maintenon. Madame du Barry. Cleopatra—"There!" he had said. "Now, nine out of ten of the young ladies I've interviewed have pronounced that 'Clear-patra.'" He liked the way she spoke, and he had liked her appearance. "You've got distinction, Miss Alban," he said. She liked that. She liked Mr. Chiswick. Only she was not altogether sure about Gateways.

It was a correspondence course. It offered to the Women of America a system for developing the individual charm that lies dormant in each of you. Through the Three Gateways of the Spiritual, the Physical, and the Mental.

Well, Susie thought, some of those exercises are good, darn good. All that about the care of the skin, and about diet is perfectly sound. And the great women of the past are pretty interesting. It couldn't hurt anyone to take the course, and it might help a lot, in some cases.

Let us analyze Charm, one of the folders said. Susie, as was her duty, had seriously studied all the literature of Gateways, but she did not find the Chiswick description of Charm satisfactory. I think he's too fond of the mysterious and the subtle, she thought. Personally, the kind of charm I'd have, if I could, would be a lot more obvious. I'd like to knock them cold. I'd like men to lose their heads completely the moment they set eyes on me.

She sighed. Or even one man, she thought. All my beaus have been pretty dingy—and they never seem to have any trouble at all in keeping their heads. Here I am, twenty-one, and there's never been anyone really exciting. I've always picked the right boys to fall in love with, the handsome, debonair ones. But the men who fall for me are very otherwise. Some plump, and several with spectacles. Well, will it be always like that?

No, she said to herself. It won't. I've got the nicest outfit of clothes I've ever had in my life, and I'm going to be traveling around, meeting new people all the time. If I can't get some results, I'm hopeless. Or I wonder... She looked out of the window dreamily. I wonder if I could try the mysterious line myself... A veil, and mascara? The Egyptian women lengthened their eyes with kohl...

"Pardon me, madam," said a man's voice at her elbow. "Would you care to look at this magazine?"

She had had a glimpse of him before, sitting at the end of the car, a jaunty fellow growing bald, dressed in a brown belted jacket, gray flannel trousers, and brown-and-white sport shoes; he looked, she thought, like a neat, clean tramp.

"Oh, thank you!" she said, taking the magazine he held out. This was done without any thinking, it was pure instinct to be friendly when someone else was friendly. But when he swiveled the empty chair beside her, and sat down facing her, she did begin to think. Maybe I'd better not encourage him.

She opened the magazine and began turning the pages. It was a trade journal devoted to hardware; there were photographs of windows full of tools, photographs of men at dealer's conventions. Well, what's the idea? Susie thought. Is it something subtle, to show me that he's some big hardware man?

"Does it interest you?" he asked.

She glanced up at him, determined not to encourage him. But he had a look that surprised her, a look that was somehow familiar. His underlip was thrust out, his little blue eyes twinkled in his ruddy face. Obviously he thought this was a joke. You can discourage a man if he's trying to flirt, Susie thought, but it's pretty brutal to discourage anybody's jokes. Especially when he's not young.

"Well, maybe it's very instructive," she said.

"It is," he said. "It's good to know that there are thousands of men thinking about hardware, night and day, planning to develop it. Thinking up new ways to display can-openers."

Something familiar about you, she thought, glancing again at him. Have I met you before?

"What's a 'ricer'?" he asked.

"It's a thing you squash potatoes through," she said. "To make those little squiggles, you know."

"Now that's it!" he cried. "That's the spoken word." He leaned forward. "If you'd been asked to write a definition of a ricer," he said, "it would have been something like this: A ricer is a kitchen implement by which potatoes are forced through a sieve. Wouldn't it?"

"I guess so," said Susie.

"I'd be willing to bet you can't write a decent letter," he said.

"Well, you'd win," said Susie.

He brought a package of cigarettes out of his pocket. "Confound it!" he said. "I forgot. No smoking in here. Shall we go into the smoker?"

"All right!" Susie said, starting to rise. But she sat back again. After all, she thought, even if he does seem familiar, I don't know anything about him. If it wasn't for Mr. Chiswick, I wouldn't care. I mean he seems like a cheerful little guy, and I'd be willing to talk to him, and no harm done. But Mr. Chiswick was very earnest about appearances. Remember, Miss Alban, he said, that you're representing Gateways not only while you're actually interviewing prospective clients, but all the time.

"Well?" said the man. He was standing, looking down at her.

"I don't know about going in a smoking car," said Susie. "I never have."

"Then it's time you did," he said. "You don't want to travel through life in a sissy Pullman."

"I know. But...?

He brought a wallet out of his breast-pocket, and from that he took a card and handed it to her. Dr. Valentine Jacobs, was engraved on it.

"A doctor?" Susie asked.

"Of philosophy," he said.

"Oh, of course!" she cried. "You're a college professor!"

"You've heard of me?" he asked. "Maybe you've read or seen one of my books?"

"Yes, I probably have," said Susie. I'm certainly not going to tell him he's typical, she thought. Nobody likes to be typical of anything. But that's why he seemed familiar. He's got that special professor's way of being up-to-date. She rose, "I will go in the smoker, thanks," she said.

Not even Mr. Chiswick, she thought, could object to her going with a Ph. D. This is fun, she thought. This is the way traveling ought to be. Meeting new people.

They went through the car, Dr. Jacobs first, jaunty and slight in his belted brown jacket, and the tall young Susie behind him, a pleased look on her serious dark face. They went through a second car, and a third, then he opened the door of the fourth, and they stepped into a gray haze.

"There's a seat," he said, leading the way down the aisle.

There were no other women in here, only men, and they all seemed so subdued and gloomy; the floor was bare and the lights seemed dim. Queer, thought Susie; a ghost train.

"Well, fellow travelers!" said Dr. Jacobs. He had stopped, and stood resting his hand on the back of a seat where two men were sitting, both of them young, and both good-looking. One of them smiled, and one did not; then the doctor went on to a vacant seat, and waited for Susie to settle herself by the window.

"Two interesting young fellows," he said. "One of them's quite a radical, and the other's a die-hard conservative." He offered her a cigarette, and lit it for her, and one for himself. "It's very instructive—for me," he said. "I continue to learn."

Yes, thought Susie, Father talks like that. I learn from my students, more than they suspect... I like Dr. Jacobs. He's cozy, and you can see that he likes Youth.

"And do you lean toward the Left?" he asked.

"Well...? said Susie. She had been asked that question before, and she had an answer. "This is a transition period...? she began; but he laughed, which was something other professors had not done.

"That's fraudulent," he said.

"I know it," said Susie. "I really haven't any opinions, much."

"You're...? he said, and stopped, because one of his interesting young fellows had risen and come to his side; a slim fair-haired boy with gray eyes.

"Excuse me!" he said, "but if you'll give me the address of the boarding-house you mentioned in South Fairfield...? She looked up, and found him looking sidelong at her. They both glanced away.

"Just tell your taxi driver to take you to the Brett house," said Dr. Jacobs.

"I see," said the other. "Thanks...? He lingered a moment, but nothing more was said. "Well, I think I'll get a breath of fresh air," he said, and went off down the aisle.

"He's the radical," said Dr. Jacobs. "His name is Carroll. He seems to be a very decent sort of young fellow, but of course I don't know anything about him. Would you like to talk to him?"

Susie thought about it.

"That was why he came, of course," said Dr. Jacobs. "He hoped to be introduced to you."

And now, thought Susie, you're just letting me use my own Judgment. You're waiting to see what Youth will do. "I'm going to South Fairfield myself," she said. "Only I'm going to stay at the Fairfield Arms."

"Don't!" said Dr. Jacobs. "Take my advice, and don't. It's one of the most depressing little hostelries I've ever met in a very extensive experience. At Mrs. Brett's you'll get excellent food, a good bed, a big, clean room, and for considerably less money."

"But it's been sort of arranged for me," Susie said. "I'm on a business trip, you know, and I've got a list of what is supposed to be the best hotel in each town."

"The supposition is erroneous for South Fairfield," he said. He did not press the matter, though; they finished their cigarettes chatting affably enough. "I think I'll go back to the sissy Pullman now," Susie said. "It's pretty thick here."

The doctor escorted her back to her seat, and sat down opposite her. "Would you mind telling me," he asked, "what kind of business trip you're making? It's nothing but rank curiosity on my part...?

"Well, no, I don't mind," said Susie. But she did. She told him in a sketchy fashion about Gateways. "I think," she said, "that any sort of culture is better than none."

The doctor listened; he looked at one of her booklets, and put it into his pocket. He rose. "I hope you'll decide to come to Mrs. Brett's," he said. "But in any case, I'll see you, Miss—?"

"Susie Alban."

"Miss Susie Alban," he repeated. "I'll leave you the magazine, to study."

With a smile he went off, and it was flat and dull without him. If I were a man, Susie thought, I'd wander around in the train like that. Talking to everybody. That Carroll boy was rather attractive. Did he really want to be introduced to me? Did he like my looks when he saw me going past him? Or was he just bored? I'd feel so differently about everything if even one man would be smitten by me at first sight. Of course, it's nice for a man to learn to care for you as he knows you better; but just one sudden, violent conquest would help.

The six or seven people in the car with her were either reading or sleeping. They did not look interesting. She was growing restless and faintly worried. Suppose, she thought, that that Carroll boy is somebody I would have liked, and now I'll never meet him? There must be lots of things like that in life. Your whole future is changed by turning a special corner at a special moment...

I'm going to Mrs. Brett's, she thought.

"South Fairfield!" said the conductor in a confidential tone. "Next stop, South Fairfield!"

He took Susie's two bags out to the platform, and Dr. Jacobs joined her there.

"I think I'd like to go to Mrs. Brett's," she said.

"Excellent!" said he. He descended nimbly to the platform, and helped her down. As the train slid quickly away, young Carroll approached them. "Miss Alban," said the doctor, "this is Richard Carroll—also going to Mrs. Brett's."

Carroll took off his hat, and they looked at each other.

"The fellow I met in the smoker is coming too," Carroll said. "Name is Loder."

This Loder was standing a little way off; big, dark, somewhat sullen, but handsome. Carroll made a signal to him, and he came up to them, bag in hand. "We can share a taxi," the doctor said. "Miss Alban, Mr. Loder."

He gave her a dark look, no smile, they all crossed the platform of the sunny little station. "Doctor! Doctor!" cried a voice. A thin man with a neat little straw-colored mustache was hurrying toward them.

"Well, Brett, how are you?" said the doctor.

"We have a new car, y'know, Doctor," said Brett. "So I came to fetch you."

"Excellent!" said the doctor. "And I've brought you three more victims, Brett."

Brett gave a smile like a spasm. "This way, please?" he said, and they went in a little troop. This is fun! Susie thought. The open road, and meeting new people. This is the life!

I'LL have to get rid of this girl, one of the four men in the car was thinking.

The rich stillness of midsummer lay on the world; the grain was ripe in the fields, the trees marched up the hills, pale-green and emerald-green and yellow-green, here and there a dark spruce and a copper beech, all unstirring against the pure blue sky. It made him sick to look at that unbounded peace, and to think of his danger.

I could manage Eve, he thought. Eve! God! what a name for her! I remember that book of Bible stories we had when we were children. The Angel driving Adam and Eve out of Paradise. She had long hair down to her knees, and a little dress made of skins, and she was holding Adam's hand. My Eve never had any idea of leaving her snug little garden hand in hand with me. No. She was going to stay right there, and I was to be driven out.

But she liked me, the first moment she saw me. More than liked me. She loved me... She won't admit it. She's too damn respectable and prudent, but I could see... Even now, if I had money, or prestige. Or anything. Look at the risks she took, coming out to meet me, with that husband of hers, half-crazy anyhow with suspicion... Even now—if I had anything...

Her letter's in my pocket now. I'm afraid you've misunderstood me... Better for us not to meet again. Only, we're going to meet again, Eve darling, and I never misunderstood you. Not for one little minute. You're frightened, now, that's all.

"Oh, yes!" said Susie. "I have to send Mr. Chiswick a report every night."

I could be put in jail, the man told himself. I could be locked up like a wild animal. This girl could do that. She set the pack after me, with one word. I've got to stop her. I can manage Eve, all right; but this girl.... Is she a fool? Or does she know already?

God! In another two weeks, or less, I'd have been all right. I admit I made mistakes, took too many chances. I admit I lost my head—a little—over Eve. But I could have fixed all that. Unless somehow he's found out. Unless he's sent this girl to spy on me. To get the facts. The evidence. I could be put in jail. I could be locked up.

But I'm not going to be put in jail. If old C. had any facts, he wouldn't have sent the girl. He'd have sent a policeman. So he can't be sure. If he suspects anything, he's sent her to check up, get information. I've got to stop that. I've got to get rid of her.

Is she a fool? Did she say she'd come from Chiswick because she doesn't know anything, or was it a trick? While I'm studying her, is she studying me? That friendly air—that could be a good line. But I've got to know—and know quick. And whatever it is, whether she's a fool or not, I've got to stop her.

"Oh, yes!" Susie said, answering a question he had not heard. "I've got the name of at least one prominent woman in every town; and I'm supposed to get other names through her."

Why is this other fellow asking her all these questions? What's his interest? Suppose I ask a question now? Then I'll know. However she answers it, I'll know. Only I've got to take the right tone. Casual...maybe...better not ask just now.

But he did ask. "Is your list confidential?"

"Oh, no!" Susie answered. "In fact, I'm supposed to get a line on people before I see them, if possible. Maybe one of you knows the woman I'm going to see here? Her name is Mrs. Person."

There was a silence so complete and so strange that she looked from one face to another.

"Did I drop a brick?" she asked.

Somebody laughed with heartiness. "I wish you luck!" he said. "I suppose you'll be starting off to see Mrs. Person first thing in the morning?"

"Ah reckons Ah will," said Susie.

You won't get there, thought the man. I'll stop you—somehow.

THE car turned up a gentle hill on the summit of which stood a fine old house, badly in need of repair, with tall white pillars up the front. It was unfenced, no garden, only a wide stretch of grass growing high and rank, and here and there a noble old tree; there was a look of neglect about the place, but it was in no way depressing.

"Queenie'll be a bit surprised," said Brett. "She wasn't expecting anyone but you, Doctor. If you people will make yourselves comfortable on the veranda for a moment...?"

He stopped the car, and they all descended. On the veranda was a row of rocking-chairs. Susie sat down in one; the doctor sat on one side of her, and the fair-haired Carroll on the other. Loder walked past them to the end of the veranda and stood looking out at the horizon. Insects were chirping in the grass, but that cheerful chorus was part of the golden peace; the shadows of the trees were long, the blue of the sky was paling a little.

I've been in the city so long, Susie thought, I'd almost forgotten how lovely the world is. I'm so glad I came here instead of going to any hotel. I like this. I'm so thankful I got this job instead of a job in an office. I wish I could travel for—let's say four years, until I'm twenty-five. Then I'll be ready to get married and settle down.

Suppose nobody very attractive ever wants to marry me? I know the Gateways idea is that every woman can have charm, but I'm not so darn sure about that. And if it was true, and they all found out how to be charming, think of the competition! I honestly could do more, though, about developing a spot of charm in myself. Which would be my quickest way, I wonder? The physical, the mental, or the spiritual? Study Your Self, the course says. Observe how others react to you.

She turned her head quickly toward Carroll to see if he was looking at her. He was not. He was staring straight ahead of him with a tired look on his fine-drawn face. She glanced toward Loder, and he was still gazing at the horizon. Handsome, she thought, contemplating his pale and rather sullen face. I like that sort of haunted, bitter type.

The house door opened and a woman came out; the doctor sprang to his feet.

"My Queen!" he cried, and approaching her, he took her hand and raised it to his lips.

The woman laughed, leaning against the doorway, a slender deep-bosomed young woman in a blue cotton dress, with a blue bandanna tied over her untidy copper-colored hair. She had a wide gamine mouth, a turned-up nose, narrow blue eyes; she was slatternly, she was impudent, and she was fascinating.

"This is Miss Alban, Mrs. Brett," said the doctor. "And the Messieurs Carroll and Loder."

"Which is which?" asked Mrs. Brett, turning her head.

"Oh, you're Mr. Loder?" she said, and her blue eyes looked him up and down. "Well, I hope you'll like it here, Mr. Loder." Then she turned to Susie. "I'll show you your room," she said amiably. "If things aren't so nice you can blame my husband. He had a right to phone up from the station and tell me to expect you." She opened the screen door. "But if there's any way to do things wrong, trust Percy to find it," she said.

She led the way up a broad and beautiful stairway, and opened a door on the floor above. "If you want anything," she said, "just go out in the hall and call me. Dinner'll be kind of late, I'm afraid, but I'll do my best."

She went off, and Susie closed the door. It was a big room, filled with the bright dazzle of the setting sun; the sweet air came in at the open windows; it was bare, very bare, only a little day-bed, a chest of drawers, one chair, one small rag rug on the polished floor, but it was clean, and to Susie, indescribably charming.

This is the life! she said to herself. All these new places and new people. You feel so darn light and carefree, just coming in casually like this for a night or two... But I probably shouldn't feel so joyous. It's not business-like. I ought to think about my work. They were all stricken when I mentioned Mrs. Person... Something queer there. Well, I'm sorry, but I like there to be something queer.

She strolled up and down the big room, glad to stretch her legs after the journey. Maybe Mrs. Person is evil. The local Lorelei. In that case she won't want our course in how to be charming, but she might give me the name of someone else. Anyhow, I look forward to meeting Mrs. Person. I like a touch of mystery.

She stopped to look at herself in the mirror over the chest of drawers. I'd like either Carroll or Loder to fall for me, she thought. Or both. Nothing serious, but just enough to build me up. The doctor said that Carroll wanted to meet me. He may be liking me more than I know. He may have come here simply on my account. They say a woman always knows when a man's attracted, but I don't. I never suspected that Carter boy of being smitten until he began that frightfully embarrassing stammering.

Well, do I like Carroll? I think I like Loder better. More intense. And that's typical of me. I always fall for the boys who don't pay any attention to me. This—

A door banged downstairs, and Mrs. Brett's voice came up to her, low and husky but distinct.

"You're a brute!"

"Less of it, if you please," said Brett's voice curtly.

"There's going to be a lot more of it," said she. "You're a brute! Four people. Four people—for me to cook and scrub for!"

"Queenie!" he said. "Be reasonable—"

"I won't!" she said. "You're not going to make a slave of me, Mr. Percy Fancypants Brett. I won't put up with it, and I don't have to, either. I could walk out on you right here and now; and there's somebody who wouldn't expect me to scrub and slave."

"Very well!" said Brett.

"What do you mean, 'very well'?" she demanded.

"You'll see!" he said.

"Percy—"

"Let me alone!" he said. "I know damned well what you're hinting at, and I've had enough. Stand aside there!"

The door banged again and there was silence.

Pretty sordid, thought Susie. Pretty horrible to think of people tied to each other when they felt like that. I thought Mr. Brett was rather nice; polite and gentle. He's very different from Queenie, better educated, more civilized. But she's an attractive hussy in her way, no doubt about it; and more vital than he. A remarkably ill-suited couple, I should say.

There was a great tramping of feet outside, as if a regiment was coming upstairs.

"Same room you had before, Doctor," said Brett's voice, cheerful now. "Mr. Loder and Mr. Carroll, you can choose between these two to suit yourselves."

"I'll take this one," said Loder, instantly; and a door closed almost with a slam.

"Well, I'll be damned...!" said Carroll with surprise.

"Seems to be nervous," the doctor observed. Two other doors closed, and then there was a knock at Susie's door. It was Brett with her two bags.

"Everything all right, Miss Alban?" he asked, with a gentle apologetic smile.

"Oh, yes, thank you!" she said.

"I'm just driving down to the village, Miss Alban," he said. "I wondered if you'd like to come along? I could take the road by the lake, and you could see something of the countryside."

"Why, yes, thank you, I'd love it," said Susie.

He seemed to be waiting.

"You mean, right away?" she asked.

"Well y'see, I have a lot of errands to do," he explained.

"All right!" she said, and put on her hat again. They went down the stairs and out of the house to the car that stood in the driveway.

"Complicated," he said, "this business of being an innkeeper. But very interesting. Meet all sorts of people." They sped off down the hill, and Brett kept on talking in a pleasant, but not very entertaining fashion. "Not much going on in South Fairfield," he said. "Prosperous little town, though." He told her the population, the number of churches, he told her about a new bus route. He was driving fast and he kept his eye on the road, so that she did not feel obliged to look at him, or to listen very attentively. She said, "I see!" from time to time, and enjoyed the scenery.

They turned into a long straight road, lined with fields behind stone walls, all empty in the golden sunset light, no buildings, no traffic. "Quite lonely," Susie observed.

"Well, y'see," said Brett, in his apologetic way, "it's a new road. People haven't got into the habit of using it much yet. Now, then, here's the lake."

It looked like a flooded meadow, a quiet sheet of water fringed with reeds; it had no beginning, no end, no definite outline, it simply spread out with tongues of still water stretching across the fields. "I see!" said Susie politely. She didn't like this lake, or this road; it seemed to her a melancholy scene. They were coming now to a wood.

"Now, there, just beyond those trees," said Brett. "There's the old road. You can see the roof of the hotel."

That put an idea into her head. "If it's not taking you out of your way, Mr. Brett," she said, "could you stop at the hotel? There might be a message for me, and anyhow I'd like to give them my address in case Mr. Chiswick wanted to reach me."

"Mr. Chiswick...? Brett said. "Oh, yes! Certainly, Miss Alban." He drove steadily on. "Suppose I leave you there, Miss Alban, while I do my bit of shopping? Might be tiresome for you, stopping at all these shops and so on."

She agreed to that, and he turned into a side street of little wooden houses, each with its front yard and its fence of palings. There was no daylight saving here, and it was twilight now under the fine old trees; here and there a light twinkled in a kitchen window. I wonder...Susie thought. I wonder if this would be a good time to see people. Better than the morning, maybe. You'd be almost sure to find the women at home now.

"Does Mrs. Person live near the hotel?" she asked.

He took a long time about answering. "I believe she does," he said at last. "But—" He paused. "If you won't mind my offering advice...?" he said. "Thing is, I've lived here for some years, and naturally one gets to know something about the natives, what?"

"Oh, yes!" Susie agreed.

"If I were you," he said, "I'd see Mrs. Green tomorrow. President of the Women's Club here. Quite important. Very nice woman. If I were you, I'd skip Mrs. Person."

"Oh, would you?" said Susie. "Why?"

"Waste of time to see her," said Brett, and began telling her how important, how popular Mrs. Green was. "I'll be coming into town tomorrow morning," he said. "I'll be very glad to drive you in, any time you like."

What is all this about Mrs. Person, she thought. Everybody seemed queer when I mentioned her, and Mr. Brett obviously doesn't want me to see her. Well, I'm sorry, but that makes me all the more anxious to see her.

They were in the main street of the little town now, and Brett stopped the car before a small, neat building of red brick. South Fairfield Arms, the sign said. "I shan't be long," he said. "Half an hour or so, that's all."

"Oh, I'm in no hurry," said Susie.

The lobby of the South Fairfield Arms was a subdued and forbidding place. In enormous high-backed chairs against the wall, each with a staring light behind it, each within range of a brass spittoon and a brass ashstand, sat four or five men reading newspapers. In a vague and wandering way, she approached the desk.

"Excuse me!" she said to the clerk. "Any mail or message for Miss Alban?"

"Alban?" he replied. "No, madam. Nothing."

"Well, if there should be, will you please send it on, in care of Mr. Brett?"

"Mr. Brett," he said, and wrote it down on a card. Rather a nice-looking boy, Susie thought, if only his hair wasn't so long. He glanced up to see why she lingered.

"I wonder," she said, "if you could tell me where a Mrs. Person lives?"

"Mrs. Alexander Person?" he asked.

"That's it," said Susie.

"Well, about two blocks from here," he said. "You walk straight along in the direction of the Town Hall till you come to Oak Avenue, and it's the first corner on the right."

"Thank you!" she said, and turning away, she re-crossed the lobby and went out into the street. It had come into her head that she would go to see Mrs. Person now.

It can't do any harm, she thought. If she's busy, I'll come back tomorrow. I've got some of our literature in my purse, enough to go on with, and I've got some application blanks. It would be pretty nice if I could make a sale now, the very first day. That would certainly impress Mr. Chiswick.

She walked briskly in the cool and pleasant dusk, she came to Oak Avenue and turned the corner. And a completely unexpected and panic fear seized her. She stood still, looking up the quiet tree-lined street of small houses. I—can't...she thought. I can't just walk up to the house and ring the bell. I don't know what to say... I couldn't possibly say that introductory speech. It's awful. "I've been asked to call on you, Mrs. Person, as the outstanding woman of your community—" No! I can't! It's so bogus. Nobody would let me go on with that. Nobody would ever dream of buying that course—for seventy-five dollars. It's—

Listen! Get hold of yourself. Mr. Chiswick's paying my expenses and I've got to try. I will try. Only the morning is the best time, definitely. This is not a good time. People are getting their dinners. Tomorrow... No. Now.

She started forward at a snail's pace. I've been asked to call on you, Mrs. Person... Suppose she's hostile and horrible? All right! Let her be. Probably lots of people will be. I'll have to do this dozens and dozens of times. Here we are.

This was the house on the first corner to the right, but it was a very small and humble house for the outstanding woman of the community. Susie stopped again with her hand on the low gate. There was a dim glow visible through the glass of the door, but otherwise the house was dark. Probably out, thought Susie. She drew a long breath, and pushed open the gate, she walked along the path and up the steps. Her knees felt weak. She rang the bell and waited.

Everyone's out, she thought. Oh, if only nobody comes...!

But somebody was coming, stumping along the hall, the door was flying open with a crash, and a frightful little old man stood there, with a pompadour of white hair above a brick-red face, with glittering little blue eyes. He glared at her, and then began to grin slowly.

"Young gal," he remarked. "Young and pretty. Well, my dear?"

"Well, I—does Mrs. Person live here?" Susie asked.

"What's the matter with Mr. Person?" he asked gaily. "City gal, ain't you?"

"Well, yes, in a way," said Susie.

He laughed loudly. "Ah!" he said. "That's what I like. A city gal. I like 'em dark, too. Big—black—eyes—mmmm-mmmm...?

Is he trying to be funny? Susie thought. Anyhow, I don't like him. She drew back a little. "Well, I'll look in again," she said uncertainly.

"Here! Here! What's your hurry?" he demanded. "If you want to see the missis, why, step right in!"

"No, thank you," said Susie. "I'll come back—"

"Come in! Come in!" he said, coaxingly. "Step in and have a chat—"

"Alexander!" said a low and beautiful voice.

A woman had come into the lighted hall behind him, a slight woman in a limp, dark dress, and black hair pinned in a heavy knot at the nape of her neck.

"Alexander!" she said again, moving forward. "You wanted to see me?" she asked Susie.

"Well...Mrs. Person?"

"Yes," said the other gravely.

"Well, I've been asked to call on you"—Susie said in an unsteady voice, looking fixed past the old man to Mrs. Person—"as an outstanding woman in your community, Mrs. Person—"

"Yes," said Mrs. Person. "Who asked you to call?"

That was an unorthodox question. "Well," said Susie. "Mr. Chiswick—"

"Chiswick!" yelled the old man. "Chiswick!"

He came at Susie with his fist raised, his thin old mouth in a tight line, his blue eyes blazing. "Get out!" he screamed. "Get out!"

She turned and ran down the steps, and he stood in the doorway shouting after her. "Your Chiswick... Tell your blank blank Chiswick to come here himself. Tell the blank blank blank I'm waiting for him...?

Some of the words he used she had never heard, but they were unmistakable, and intolerable; she ran from them as if they were poisoned arrows.

"I'll kill your blank blank Chiswick!" he yelled. "Tell him...?

The house door closed with a slam, and Susie stopped; she leaned against a tree, sick and shaken.

ONE of the four men she had met that day was standing on the other side of the street in the shadow of a tree, listening to old Person.

God! he said to himself. How did he find out?

"I'll kill your blank blank Chiswick!" yelled old Person.

God! the man cried to himself. Then he was afraid he had cried it aloud, and he looked over his shoulder. The street was deserted, the house behind him was dark. The sound of footsteps made him turn back, and he saw the girl going toward the corner. She looked tall, and very slight in the dark; she went leisurely, and he thought that was because she was satisfied. She told old Person, he thought. That's what she went there for.

It shocked him. It's the one thing I never thought of, he said to himself. It's the worst thing she could have done. That damned vindictive old savage... I'd rather have the police. I'd—well, I'll have the police, too. My God! I only needed two weeks, or less, and I'd have been all right. I'd have been safe. I wasn't even worried, this morning.

A sort of anguish seized him when he thought of this morning. He had eaten his breakfast with relish, he had felt wonderfully well, vigorous, confident, because his plans had been good ones. And then she came...

He started after her, keeping to the strip of grass beside the pavement on his own side of the street. He had nothing definite in his mind, nothing but a feeling that he must not let her out of his sight. Where's she going now? he asked himself. To the police?

He remembered old Person's voice cursing and yelling. That was the first hound baying. But that wasn't enough for her. She wanted the police after him, too. The whole pack, to hound him down. And why? He had never injured her, he had never heard of her, never imagined before today that anyone like her existed. There she was, strolling along, so damned nonchalant. Pleased with herself.

It came into his mind that she was smiling to herself in the shadow, and he hated her. She wants to see me hunted down like an animal, he thought. And he went after her, perfectly silent on the grass. He quickened his steps; his heart quickened, too. There was still nothing definite in his mind, only a curious excitement. He wanted to catch up with her, that was all.

She had almost reached the corner of the deserted street. He wanted to catch up with her before she reached the street light on the corner. So he began to run.

Suddenly there was a clatter of horses' hoofs, and he stopped in terror. The hunt is up. The Four Horsemen... You don't—you—can't be hearing galloping horses... That's a sound out of a play. Out of a nightmare. The Valkyrie. The witches after Tam o' Shanter. The sheriff's posse after the killer.

She reached the corner. He saw her clearly under the street lamp. So damned nonchalant in her dark suit, her hat on the side of her head. He knew she was smiling to herself. Or laughing.

Around the corner came a big, heavy, gray cart horse, ridden by a boy in overalls, who was leading another big gray horse. They went past him with a clatter, and when he turned his head, the girl was out of sight. He went after her, but she had gone into another world, not a tree-lined, deserted street, but a street with little shops, and people, and traffic. She could afford to laugh at him now. She was safe.

She's going to the police, he thought. For God's sake, why doesn't she hurry? Because she was enjoying this; taking her time. Laughing at him. He had to go sauntering along the street on the other side. I've got to make a plan, he thought. When she goes into the police station, I'll...I'll what? Get a train to New York? Or to Bassville? Or is it safer here? Easier to hide than to run? I need time. I need time to think. I need time, I tell you.

She went into the Fairfield Arms.

He stopped where he was, before a very small shop with a newsstand outside it. If she's not going to the police...? Maybe I'd better wait and see. Only the one thing he could not do was wait. A dreadful sense of urgency possessed him. Wait? he thought. Just hang around and wait until she's good and ready to take the next step? I won't!

Someone coughed, and he turned his head to find a man standing at his shoulder, staring at him. He took some pennies out of his pocket and picked up a newspaper, and turned back along the street.

I'll see Eve, he thought. And you're going to keep me out of this, my dear Eve. You can keep that damned old savage quiet, if you try. And you're going to try. If I can shut him up, I've got a chance. No matter what that girl does.

That sense of excitement came back to him. I've got a chance, he thought. I'm not a fool. I can deal with this if I keep my head. I don't have to be hunted.

He lit a cigarette, and he smiled to see how steady his hand was.

SUSIE sat in one of the high-backed chairs against the wall waiting for Mr. Brett. Don't be silly! she told herself. In work like this, I'm sure to run across some unpleasant people. This was really nothing—all in the day's work. When you analyze it, what was it but a nasty old man swearing? I don't understand though, why the very mention of Mr. Chiswick's name started him off.

She thought of Mr. Chiswick, thin, elderly, with his pince-nez, and his trim little gray beard; Mr. Chiswick, so polite and correct. Nobody could call him names like that, she thought. Unless the old man was crazy. That seemed rather probable when you think how he behaved the moment I got there.

She sighed and glanced again at the clock. Mr. Brett was very late. Well, she thought, I certainly can't go back to see Mrs. Person, ever. I'll have to see this Mrs. Green tomorrow. I wonder if I ought to put all this in my report to Mr. Chiswick? Tell him how the old man made threats. I don't know... Maybe it isn't important. I am silly, to be so upset. Only there was something about that old man—something pretty horrible.

She moved restlessly, and then an idea came into her head, and she rose and went to the desk.

"Do you know Mr. Brett by sight?" she asked the clerk.

"Yes, madam," he said, coldly.

"Well, when Mr. Brett comes in, will you please tell him that I've decided to walk back."

"Very well, madam," he said.

"And can you tell me how to get to that new road by the lake?"

He looked as if this were almost more than he could bear.

"You go straight along to Oak Street," he said, "and you take the first turning to the right—"

"Oh, by Mrs. Person's house?"

"Yes," he said. "Right next to that house you will see the entrance to Woodmont Park. You can go straight through there to the New Road."

"Thank you!" said Susie.

She was very reluctant to go near that house again, but she despised the reluctance. I need a good brisk walk in the fresh air, she thought. I haven't had any exercise all day. I haven't had very much to eat, either, she thought, as she set forth. Just a sandwich and a cup of coffee before I got on the train. I hope Mrs. Brett is a good cook.

Oak Street looked better now, there were more lights in the houses. It's just an ordinary street, she said to herself. And probably what happened was ordinary, too. I wonder how I ought to report that interview? As a failure? I wonder if an experienced and very good salesman could have coped? Or would it have been hopeless for anyone? I wish it hadn't happened the very first place I went. It sort of undermines your self-confidence. If this Mrs. Green is hostile...

There were lights in the Person house, lights upstairs, and as she turned the corner, she saw a very bright light in the back of the house, shining out over the grass. Very quiet neighborhood, she thought, not even a dog barking. I wish I had a nice cheerful dog along with me. Now, where's the park?

It was not at all hard to find. Half-way along the block there was a signboard with a glaring light over it.

WOODMONT PARK DEVELOPMENT

CHOICE HOME SITES

LAKE SHORE LOTS

IMPROVEMENTS

APPLY TO A. PERSON, SOLE AGENT

Beside the sign was the entrance to a macadam road lined with woodland, but straight and broad and well-lit; she could see the roofs of houses ahead. It's not lonely, she thought. The lights were strung on a wire, and each one made a bright circle among the leaves, with massed darkness behind. Quite a thick wood, she thought.

The houses had no lights in them, and as she came abreast of them, she saw that they were empty and unfinished. She saw the stone walls of a foundation like a ruin. The trees rustled with an unceasing sound. Very quiet neighbors, she thought, going a little quicker. I hope there aren't any owls. I—wouldn't like it if an owl started to hoot.

The road was downhill now, and the lights, she thought, were farther apart. She thought that she could see through the rustling branches, the pale gleam of water below her. The lake, she told herself and remembered how it had looked, spreading out formless and still over the meadows. Well, then I must be getting near the New Road.

She stumbled over something, and looked down. It was a foot in a white sock and black shoe.

Someone was lying among the trees at the side of the road. Someone hurt? Someone—more than hurt? I'll go and get a policeman—I'll go—

She stopped herself. You can't run away. You have to see...She moved closer, but it was dark in the shadow of the trees. "Is there—anything wrong?" she asked aloud.

No answer. She opened her purse, and took out a book of matches; she struck one, and bent down. She had a glimpse of old Person's scarlet face and staring blue eyes; then she dropped the match, and stumbled backward.

He's dead, she thought. Don't run. That's a horrible thing to do. He's dead... I'll have to get somebody. But I won't run. I'll walk. The trees were making a strange sound—as if they were rushing after her. Don't look back. Just go ahead, quietly.

But there was another sound, a soft crackling. She had to look back over her shoulder, and she saw a little pile of leaves blazing at the foot of a tree. I did that, when I dropped the match, she thought. She had started the fire, and she would have to put it out. She had to go back.

It was a small blaze. But it was only a few inches from old Person, and that made her give a sob like a gasp. She trampled out the blazing leaves in a sort of frenzy in her desperate haste to get away.

Then almost at her shoulder, a voice spoke. She sprang away from that dark form, she knocked her shoulder against a tree, and leaned back with no strength left in her.

"It's me," said the voice. "Charles Loder. Anything wrong?"

She could not speak for a moment, so overwhelming was her relief.

"Yes," she said. "Yes. It's something... It's a man. Right—there. He's—dead."

"I've got a flashlight here," said Loder. "I'll take a look." She closed her eyes, so as not to see that figure again. But with her eyes closed, she saw even more vividly that scarlet face, and the staring blue eyes.

"Dead drunk," said Loder, in a moment. "Let's get going."

"Drunk?" she repeated, still with her eyes closed. "Do you honestly think so?"

"Sure of it!" said Loder. "Let's go."

He took her arm, and she opened her eyes and moved forward mechanically.

"Oh, but not that way!" she said. "We've got to go back to the village and get help."

"He doesn't need any help," said Loder.

"We can't just leave him there."

"Why not? It's a nice mild night."

"His wife might worry...?

"Maybe she's used to it," said Loder. "He doesn't look like anyone you'd miss very much."

He tried to draw her away, gently enough, but she stood still.

"I think—we ought to do something about him," she said. She spoke in a nice, reasonable way, but her teeth were chattering.

"I think you'd better come along to the house and get your dinner," he said. "Come on, you poor kid."

His voice was very gentle; when she did not move, he put his arm around her shoulders. "Come on, Susie!" he said. "We'll go along the road a little way, and then we'll sit down and have a smoke until you're—rested."

"That's a good idea," she said.

He kept his arm around her shoulders, and it was a comfort to her. He was young and friendly and kind, and she liked him. They started down the hill under the rustling trees; she drew a deep breath and felt steadier.

"It was sort of startling to come across him like that," she said. "And I'd already had trouble with him."

"Trouble?" asked Loder.

"I went to see his daughter, or his wife, or whatever she is," Susie said, "and he opened the door. He flew into a frightful rage, and yelled at me."

"But what about?"

I guess I'd better not tell that, she thought. It's not right to talk about Mr. Chiswick's affairs. "Goodness knows!" she said. "I suppose he was drunk then, or anyhow beginning to be."

It was reassuring to think that old Person had been drunk, so that what he said didn't count. She was beginning to feel cheerful again. They went on down the hill, and there beyond the trees was the lake. They stopped, looking at it, a pale sheet of water stretching out over the fields, perfectly still.

"If it is a lake...? Susie said, half to herself. "It looks like the Deluge. It hasn't any banks."

"There's a little path here," he said. "Let's go along it for a way, and see what it's like."

"Let's not," she said.

"Come on, Susie," said Loder. "We'll find some place to sit down and have a smoke."

She liked Loder, and he was, she thought, being as nice as he could be. But she didn't want to go in among those dark trees, or any nearer to the lake.

"We'd better—" she began, and stopped at the sound of whistling. Brisk and lively whistling that was coming nearer; it was the Priests' March from Aida, pepped up.

"Look here, Susie!" said Loder, almost in a whisper. "Let's... Come on, Susie! I want to talk to you."

He tried to pull her toward the wood. "No!" she said. "No, thanks. I want to see...?

"Susie!" he said with a certain urgency. "Please—"

Footsteps rang out, two figures appeared at the top of the hill, marching in step to the brisk whistling.

"Susie!" said Loder. "Don't say anything. To anybody."

"Why not?" she said, startled and uneasy.

"Because it might lead to a lot of trouble," he said. "Villages like this often have very strict laws about drunkenness. If the police pick up that fellow, and they know you've seen him, you'd have to go to court as a witness. You might have to stay here for days. The whole thing would be in the newspapers. It wouldn't do your business any good."

"They couldn't—"

"The old Blue Laws," he said. "It's against the law to get drunk, and it's a criminal offense not to report it, if you see a drunk."

"I honestly don't think—"

The two figures were marching smartly down on them. "Then keep quiet on my account," said Loder. "I don't want any trouble with the police."

The two figures passed under a light, and Susie recognized the doctor with young Carroll.

"Hello!" she called, very glad to see them.

Loder let go of her arm; he got out a cigarette and lit it.

"Hel-lo!" cried the doctor. "It's never Miss Alban. Well! Well! And who's this? Loder? Allons, mes enfants!"

He was in high spirits, in very high spirits; and it did not seem to trouble him that the two young men were completely silent. He took Susie's arm, and began to sing. "Glo-ry and love to the men of old...?

"Sing!" he urged her.

"I can't," said Susie, and he went on alone in a surprisingly good tenor voice. He started one song after another. "Mine eyes have seen the glory...? All along the road by the lake, and on to the highway. Then he started Sambre et Meuse, in French, excellent French.

When he stopped for breath, Susie said politely: "You have an awfully good accent."

"Why not?" he said. "I was in France three years."

"Oh, were you? Studying?"

"Oh, no!" he said. "Killing."

He made a lunge with an imaginary bayonet. "Comme çi!" he said. "Comme ça!"

"Don't!" cried Susie.

He laughed cheerfully, and began singing again. "There'll be a hot time—in the old town—tonight." All the way up the hill, up the steps of the veranda; he was still caroling when Percy Brett opened the door for them.

IT was half-past seven when they all sat down at the table.

"Seven o'clock is the regular time," said Queenie Brett. "But I didn't know there'd be four extra, so I had to send Percy to the village to get some things, and the car broke down." She paused. "Anyhow, that Percy's story," she said.

She had put on a long dress of black lace with a big, white artificial flower on one shoulder; her coppery hair was done high on her head; black mascara made her long blue eyes strangely vivid. Hussy, thought one of the four men at the table. But she can cook.

And I can eat, he thought. I'm not even nervous. My hand's perfectly steady now. I've got a good appetite. It's damn queer, but I feel—better now.

Well, he thought, that's natural. I mean I've proved that I can think fast and act. I admit that I was nervous before. But when the time came, I was absolutely cool and collected. I didn't make a single mistake. And no matter what happens in the future, I know that I can deal with it. I like the way that hussy cooks. I'm hungry. I didn't know I was like this.

Nobody here knows it. They think I'm an ordinary, commonplace man.... If they had any idea... He put his napkin to his lips to hide a grin. I didn't mean to smile, he thought. I'm not callous. I wouldn't have done that if I hadn't been driven to it. Hounded. I had to defend myself; and I did.

Eve will know what's happened. It'll do her good. She'll be frightened. She certainly never thought I had it in me to—defend myself that way. It'll be a lesson for her. She's treated me like a dog—but she won't in the future. I don't need to worry about Eve. She'll never say a word, naturally. But she'll know. I'll go to see her tomorrow, and it'll be very different. You won't be quite so condescending now, my dear Eve. You never dreamed I was like this.

Yes. I feel better. My worries aren't over, not by a damned sight. But I can cope with them later. This is a breathing-space, and I need it. A good dinner, and a good night's sleep, and then I'll be ready for whatever happens. It's a mistake to try and make long-range plans. You have to be guided by circumstances. You have to be flexible. What happened today, for instance, was completely unexpected, but when it happened, I was able to handle it. I seem to have the type of mind that works best in an emergency. The thing for me to do is to get a good night's sleep, and wait.

"And how do you like South Fairfield, Miss Alban?" asked Queenie.

"Well, I haven't had a chance to see much of it," Susie answered.

He glanced up at the sound of her slow and amiable voice. Yes, he thought, you're still here. And I may have to do something about you later on. But not now. You're not dangerous. You're simply a fool. A colossal fool. You don't know anything. If you'd ever suspected anything, you wouldn't have gone home that way. Alone, in the dark. No, he thought, I was mistaken. I'll have to watch her, in case she finds out anything, or suspects anything later on. But I don't have to bother about her now. I'll get out of here early tomorrow, and settle things in Stonebridge. All I need is twenty-four hours' start ahead of her. She can't do me any harm here.

"It's a beautiful town, so Percy tells me," said Queenie. "Not as big as New York, maybe, but better. More trees, and more caterpillars. We've got everything here. There's the Palace Theatre, only twenty-five cents to see a picture a year old, and so cut it don't make sense. We've got Society, too. We've got the grand Madame Alexander Person. I suppose you'll be seeing her bright and early in the morning?"

"Well, no," said Susie. "I guess I'll change my plans a little. I'm going to take an early morning train to Stonebridge—"

God! the man cried to himself. That was the one thing he had not expected; the one thing that must not happen. Here! he thought. Take it easy. It's only chance. It doesn't mean anything. She's just a fool.

But he had to be sure.

"I used to know somebody in Stonebridge," he said. "A Mrs. Burke. I wonder if she's on the list of your prospects?"

"No," she said. "It's Mrs. Malter I'm going to see there."

All that vigor and confidence, that sense of well-being drained out of him; he felt collapsed. But he sat straight in his chair, and he thought, he hoped, that his face did not betray him. This could not be chance. This was—what? A threat?

It must be a threat. And he would have to meet it. There was to be no breathing-space. No good night's sleep. Back came that horrible feeling of urgency and haste, that swirling confusion in his head. He had to make a plan now, instantly. While he sat here at the table.

He couldn't rest, even for a few hours. Because he was hounded. And if one of the snarling pack was silenced, others were coming on; God knew how many others. A silent and invisible pack, to hunt him down and destroy him.

He had to look at Susie again, and this time she smiled. He had never seen anything so horrible as that smile of hers, slow, subtle, triumphant. She's enjoying herself, he thought. She wants me to know she's going to Esther's. She thinks I can't stop her.

She knows what's happened here. Maybe other people know now. The police. A cold sweat came out on him and that physical nausea returned. He wanted to push back his chair and go. Run. Run...

Take-it-easy. You can't run.

"It's hot in here, isn't it?" said Queenie.

She was looking at him. He was afraid to wipe his forehead. She noticed everything; that damned hussy...

"Let's go into the other room," said Queenie. "And maybe we could have a game of poker."

"I don't know how to play poker," said Susie.

I do, he thought. I've always been lucky. Look at the whole thing that way. Like a poker game. Bluff. Watch her. Be ready. What if she does know what's happened? She can't prove anything. Nobody could. I didn't make any mistakes. Not a single one.

My brain's beginning to work again, he thought. I'll find a way to stop her from going to Esther. I'll find a way to stop her from smiling like that.

WHEN dinner was finished, they went, all except Queenie, into the next room which was in every way a Front Parlor, a big handsome room, but filled with shiny furniture upholstered in a sickly green, and lit only by a chandelier in the ceiling.

Brett brought in a box of chips and two decks of cards, he set up a folding table in the center of the room. "Let's see," he said. "Five of us—"

"Thanks, but I'll just watch," said Susie.

"Oh, no!" said Dr. Jacobs. "You must sit in."

"I don't know how—"

"I'll teach you," he said.

"Well, thanks," said Susie, "but I don't think I will. Not tonight, thanks."

"Oh, come on!" said the doctor, and took her arm.

Somehow, she did not like that. "No, thanks!" she said.

Then he tried to pull her toward the table. Just as Charles Loder had wanted to pull her back from the road by the lake. "No!" she said, trying to free her arm.

The doctor began to laugh, silently; his shoulders were shaking, his mouth was stretched wide, it seemed to her as if he were panting like a dog. She looked at him with strange uneasiness.

"Let me go!" she said, sharply.

He released her arm at once, and he stopped that laughing.

"Please join us!" he said. "I'll stake you to a dollar's worth of chips, just for the pleasure of your company."

A phrase was running in her head, picked up Heaven knows where. Certainly it was not advice that her parents or her teachers would have thought necessary to give her. Never play cards with strangers. It seemed to her of singular importance.

"No, thank you!" she said very distinctly.

There was a complete silence. And it occurred to her, for the first time, that she was the only woman among four men. Well, what of it? She asked herself. But her uneasiness was growing again. The doctor stood at her shoulder, not stirring or speaking. She glanced at Brett who was bending over the card table, and she thought he was watching her through his blond lashes. In haste she turned her head to look for Charles Loder, the one she liked best, the one who had been kind and nice. He was sitting on the sofa with his legs stretched out and his arms folded; she smiled at him but he stared back at her with a dark unwinking stare.

They were strangers, and she was alone. She knew nothing about them, and she could guess little or nothing. They were not only strange, but they seemed hostile. "I think I'll go upstairs...? she said and turned toward the door.

Carroll was standing there, and he smiled in a way that touched her. He looked tired, a little shabby in his gray suit; but so young, so understandable, so nice.

"Will you stay and look on for a while?" he said. "You might bring me luck—and I need it."

"All right!" she said.

"Now then!" said the doctor. "Loder?"

Loder didn't answer; he sat there with his arms folded, staring straight ahead of him.

"Hey, Loder!" said the doctor, and he came to with a start.

"Yes?" he said, "What?"

"Are you sitting in this game?" the doctor asked.

"Why not?" said Loder, rising.

He had been nice in that park; he had put his arm around her, he had spoken in a very kind and friendly way. But now he was queer. Susie sat down on the sofa as the four men took their places at the card table, and she thought that the doctor and Brett were queer, too. Maybe that's just because I'm tired, she thought. My first working day—if you can call it work.... I hope it isn't a sample of how things are going to be. I hope I'll never come across anyone else like that old man. But I've got to put him out of my head. He was drunk, that's all. That's why he yelled those things about Mr. Chiswick. He just seized on that name. Mr. Chiswick told me this was entirely new territory.

Of course, she thought, frowning, it's possible that the old man had met Mr. Chiswick somewhere. They might have met in New York. It might have been years ago, and Mr. Chiswick may not have been so nice then as he is now. Maybe he's not nice now. I'll kill Chiswick, the old man said, and he meant it. He meant he wanted to. People do kill people. When I first came across the old man lying there by the road I thought he'd been killed. I thought... I've got to stop thinking about him, lying there, staring. He's probably home in bed now, with his eyes closed. It's morbid, to keep on thinking about him. I must be tired—only I'm certainly not sleepy. I might try to take an interest in this poker game. It's probably a typical scene. Typical of traveling salesmen. Only the doctor's not a traveling salesman. I don't know why he's here. I don't know whether Richard Carroll and Charles Loder are salesmen, either.

She looked at Carroll's thin, tired young face, and he seemed to feel it, for he glanced at her and smiled again. She looked at Loder, and as he took no notice, she stared at him. His face in profile was very handsome but with something ominous in the straight black brows, the out-thrust underlip, even the quick way he moved his smooth dark head. He looked like a fighter, she thought.

It was a very quiet game. Someone would say—Pass-Raise you one—Raise you two... Not very interesting, she thought. "I'll see you, Brett!" said the doctor. There was complete silence while he and Brett looked at each other. Then they laid down their cards, and Brett raked in all the chips.

Carroll shuffled the pack with virtuosity, and dealt a new hand. Loder took his up, glanced at it and laid it down. "I'm out!" he said, and pushing back his chair, he rose and came over to the sofa. "Cigarette?" he asked.

"Thanks!" said Susie.

He bent and lit it for her, and remained standing before her. "Sit down?" she suggested, but he didn't answer. That seemed to be a habit of his. He lit a cigarette for himself and went back to the table; he sat there, pale, dark and somber.

"All right! It's yours, Brett," said young Carroll; and again Brett raked in all the chips. "I guess that's finished me. I'm too hard up to lose any more."

"I'll stake you," said the doctor.

"Thanks," said Carroll, "but I guess my luck's out tonight." He came and sat down by Susie.

"I didn't bring you luck then," she said.

"It wasn't that," he said, "but—" He lowered his voice. "The doctor's—a bit high," he said. "I never like that, in a game."

"High?" Susie said. "You mean that's a way he has of playing?"

"Don't you know what 'high' means?" asked Carroll, surprised.

"Oh, that?" she said. "You mean you think he's been drinking?"

"Who's been drinking?" asked the doctor, turning round in his chair, and as Susie's face grew hot, he began to laugh again. "That's set me thinking," he said. "If you've got a drop of anything in the house, Brett...?"

"Beer, Doctor," said Brett.

"Then—" the doctor began, when the doorbell rang, and Brett pushed back his chair. But footsteps were already going along the hall, so he waited.

"Well, for the love of Pete!" said Queenie's voice from the hall. "And what do you want?"

"I want to see Mr. Percy Brett," said a man's voice.

"Why?" Queenie asked. "What about?"

"Ask Mr. Brett to step out here, if you please," said the man's voice.

"I won't," said Queenie. "I won't have cops coming here, spoiling my business."

"A cop...? said the doctor in an undertone.

"Get Mr. Brett out here, or I'll go in and get him," said the man.

Brett rose, and went into the hall.

"Well, Sergeant?" he said in his pleasant voice. "What can I do for you?"

"I'll have to ask you to come along to the station, Mr. Brett."

"He will not!" said Queenie. "What about?"

"Now, Mrs. Brett—" said the sergeant.

"Queenie...? said Brett. "Why do you want me, Sergeant?"

"Captain Catelli wants to ask you some questions," said the sergeant.

"What about?" cried Queenie. "You've got to tell him what about. This is America, and you're not going to pull him in—"

"Wants to ask you a few questions," said the sergeant, "in re this here accident to Mr. Person."

"What accident?" asked Brett.

"That's what we want to find out," said the sergeant. "Now, Mr. Brett...?

"Don't you go, Percy!" said Queenie.

"I'm perfectly willing to answer questions," said Brett.

The doctor moved to the doorway, and Susie followed him.

"Mr. Person's accident serious?" the doctor asked.

The sergeant looked at him calmly. A blond man, he was, portly and erect.

"A fatal accident," he said.

"My God!" cried Queenie. "Murdered—"

She checked herself, and there was a complete silence. Looking over the doctor's shoulder, Susie saw how very white Brett was. He was looking at his wife, and she looked at him, her lips parted.

"I just thought that...? she said, "because he was so unpopular.... I just thought that maybe somebody...?

"Perfectly natural," said the doctor. "The sight of a policeman puts ideas like that in anyone's head."

"Yes, that was it," said Queenie.

There was another silence. "Well, Mr. Brett—" the sergeant began.

"Are you arresting Mr. Brett?" asked the doctor.

"Nope," said the calm sergeant. "Captain Catelli wants to ask him some questions."

"I don't know whether it's a legal requirement," said the doctor, in an affable, apologetic way, "but it's customary, isn't it, to give a witness some information as to what he's being questioned about?"

"I'm not trying to put anything over," said the sergeant. "Not on nobody. Old—that is, Alexander Person was killed this afternoon between around five-thirty and seven; and the Captain wants to know where Brett was at that time."

"Excuse me!" said Susie, and everyone turned to look at her. "Was...is it all right for you to tell me how Mr. Person was killed?"

"Knifed," said the sergeant.

She had to go on. She had to know.

"Was he—did it happen in his own house?"

"Nope," said the sergeant. "By the roadside."

Then he was dead when I found him, she thought. He was murdered when I saw him there. Murdered. Knifed. With his eyes open... She felt a little sick for a moment; she waited for that to pass, and then she turned back into the sitting room to Loder. He stood near the table, and he looked at her, a dark narrow look. Someone outside closed the door into the hall.

"Look here!" she said, going close to him and speaking very low. "We've got to tell about finding—"

"Sit down!" he said, and almost pushed her onto the sofa. "Don't say one word!" he whispered. "I'll explain later."

"But—"

He was looking down at her, still with that dark, narrow glance. "If you say anything," he told her, scarcely moving his lips, "you'll ruin two innocent lives."

He turned on his heel, and walked off into the dining room, and she sat on the sofa, paralyzed. I'm the one who found the body, she thought. It's a serious thing, to keep that from the police. Even if my telling did get some innocent people into trouble... And I have only Charles Loder's word for that.

A new thought came to her that made her eyes widen. But did he know then? she thought. He had a flashlight. He could see better than I. He bent over him and had a good look. Then he said, "dead drunk," and he told me that tale about Blue Laws. I don't know why I believed him—except that he seemed young and nice, and there weren't any reasons for suspicions. But if he did know...

And where did he come from, anyway? I was stamping out the fire, and he was there. I didn't see him on the road. I didn't hear him until he spoke. It was so dark under the trees... I couldn't have seen him if he'd been there all the time.

It was horrible to think of that. Horrible to imagine Charles Loder standing there in the dark, under the rustling trees... "Knifed?" she said to herself. That could be done in silence.

"You look pale," said Carroll. "Don't you feel well?"

"I'm all right," she answered.

"I'm sorry you're so upset," he said. "You didn't know the man, did you?"

"No," she answered. "Only—"

Charles Loder was coming back with a glass of water. "Like some whiskey?" he asked. She shook her head and took a sip of water, and glanced up cautiously at Loder. Oh, no, she thought. He's not a murderer. I know that. Maybe it's instinct, or intuition, but, anyhow I know it. She gave a long sigh, and he stood smiling down at her; they smiled at each other.

The door opened and the doctor came in holding Queenie by the arm. She was as white as paper, but she was smiling in a dazed, almost idiotic way; she sat down on the sofa beside Susie, and turned the smile on her. Then in came the sergeant walking proudly, his back curved in, his front curved out, his head a little on one side.

"A few little questions...? he said, persuasively.

The doctor seated himself on the arm of the sofa beside Susie.

"Where's Mr. Brett?" she whispered.

"They took him to the station," he murmured. "But don't worry. Don't worry about anything." He laid his arm along the back of the sofa behind her shoulders.

"Been having a little game, I see," said the sergeant, looking down at the cards on the table, with a sly smile on his pink-and-white face. He's the first policeman I've ever seen inside a house, thought Susie, and studied his profile, a rather sharp nose, a short upper lip. Like an Easter rabbit, she thought. I hope he's stupid. Because I'm nervous, or something.

"Now, miss!" he said. "Just a few questions."

No! she thought, in a panic. I haven't made up my mind yet whether to tell, or not... I need a little time... I'm not ready...

Name? Age? Address? Occupation? She answered in a vague and hesitant way, and he wrote down the answers in a note-book.

"Now, Miss Alban," he said. "I understand you were in town this afternoon. If you'll give me an account of your movements between five-thirty and seven...?"

"Well," she said, "Mr. Brett drove me in to the hotel."

"Yes?"

I'm not going to make up a lot of lies. I can't. I won't. What "innocent lives" could be ruined? I don't believe that. I hate this! I hate this!

"Mr. Brett drove you to the hotel," said the sergeant. "And then—?"

"I walked around."

"Around where?"

"I don't know."

"Take it easy," said the doctor, and his hand was on her shoulder with a firm and steady pressure. "The clerk at the hotel—"

"Here now!" said the sergeant. "That'll do, Doctor."

Thank you, Doctor! Susie cried in her heart. Of course, the hotel clerk would tell, or had already told, how she had asked the way to Mrs. Person's house. And he would tell how he had later told her the way home—through Woodmont Park. I can't lie, even if I wanted to, she thought.

"I don't remember the names of the streets," she said. "I went to call on Mrs. Person, to sell her one of our courses, but I didn't get a chance to talk to her."

"See anybody at the house?"

"An old man opened the door."

"Did you have a talk with him?"

"Well, not exactly," said Susie. "He was—disagreeable. He told me to go away."

"In what you would call an abusive way?"

"Yes," she said. "He yelled at me."

"Did he threaten you, miss?"

"No," she said.

"Did you see Mrs. Person again when you went back to the house?"

"I didn't go back to the house."

"You didn't go back to Oak Street?"

"Yes, but not to the house."

"You went through Woodmont Development on your way home?"

Now it's come! she thought. I'm sorry, but I'm not going to lie. "Yes," she said.

"What time was that, miss?"

"I don't know. But it was dark."

"Now, after Mr. Brett left you at the hotel—when was the next time you saw him?"

"When we got back here. He opened the door for us."

"Did you meet anybody you know in Woodmont Development?"

"Yes," she said, and again she felt the pressure of the doctor's hand on her shoulder. "Mr. Loder, and Mr. Carroll, and Dr. Jacobs."

And now he'll ask me—

"Thank you," said the sergeant, and he turned to Carroll. He had finished with her.

Robert Carroll. Age, twenty-six. Address, River Turrets Hotel, New York City. Occupation?

"Salesman," said Carroll.

"What's your line, Mr. Carroll?"

"I can't see how that matters," said Carroll, briefly.

"I don't, either," said Queenie, suddenly. "I don't see why you have to come here and pick on my guests."

"Now, then, Mrs. Brett...?

"What do you think this is?" Queenie demanded. "A special excursion from New York, to bump off old Person? And if you think they did it, why did you go and pull in Percy?"

"That's enough, Mrs. Brett," said he.

"It's a damned sight too much, if you ask me," said Queenie. "You live here, and you ought to know who's the likeliest one to knife old Person."

"You'll have to leave the room, if you won't keep still," said the sergeant.

She laughed. It was a clear and a pretty laugh, wonderfully insolent. The sergeant's face reddened.

"I know who killed old Person with a knife," she said.

"You'd better be careful what you say—" he began.

"Want to make something of it?" said Queenie. "Because I don't care. I'll say it to anybody."

"Any more interruptions, and out you go," said the sergeant.

"Really?" said Queenie, resting three fingers elegantly on the crown of her tawny head.

There was something magnificent about her, something in her defiance that changed the very air. So that they no longer seemed like puppets, helpless before an impersonal force. They were people now. And the sergeant, still red, turned back to Carroll.

"I'm a salesman," said Carroll.

"If we want more information on that later," said the sergeant, "we know how to get it. Now let me have an account of your movements between five-thirty and seven."

"I drove into town in a taxi with Doctor Jacobs and Loder. We went to the hotel and had a drink, and then I went out and took a walk. I don't know where I walked, and I don't know what time I started or what time I got back to the hotel."

"All right! Who did you meet when you took a walk?"

"Nobody I knew."

"Ever been here before, Mr. Carroll?"

"Yes."

"When?"

"Two or three months ago."

"Still being a salesman?"

"Yes."

They were frankly hostile, curt and wary. Carroll's tired young face was tense, and somehow happy as if he enjoyed this.

"When you went back to the hotel, who was there?"

"Doctor Jacobs. We had another drink."

"Mr. Loder there?"

"I don't know. The bar was crowded. I didn't see him; but that doesn't mean he wasn't there."

"And then?"

"And then we walked home."

"Your name, Mr. Loder?"

"Charles Loder. Age twenty-two."

"Occupation?"

"I'm on a holiday," said Charles.

"What's your occupation when you're not on a holiday?"

"I'm an author."

"Mean you write books?"

"Short stories," said Charles.

"Address?"

Charles lit a cigarette.

"I'm not settled anywhere," he said. "I move around, looking for material."

"Where's your mail sent to?"

Suddenly Charles changed his manner; his brusque and almost sullen air turned to a confidential bonhomie.

"That depends on who's writing to me, and where I happen to be," he said.

"I've got to put down some address," said the sergeant.

"Well, what's the matter with this place?" asked Charles. "I've got a room here and a bag."

"Do you want to give this house as your address?" asked the sergeant.

"Why not?" said Charles, airily.

"It's up to you," said the sergeant, and wrote in his book. "Now, about this afternoon?"

"I drove into town with Doctor Jacobs and Carroll. We went to the hotel and had a drink. Then Carroll said he was going to take a walk, and after a while I thought I'd do the same. So I went out, and I walked around."

"At what time, and where?"