RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Deep West," Little Brown & Co., Boston, 1937

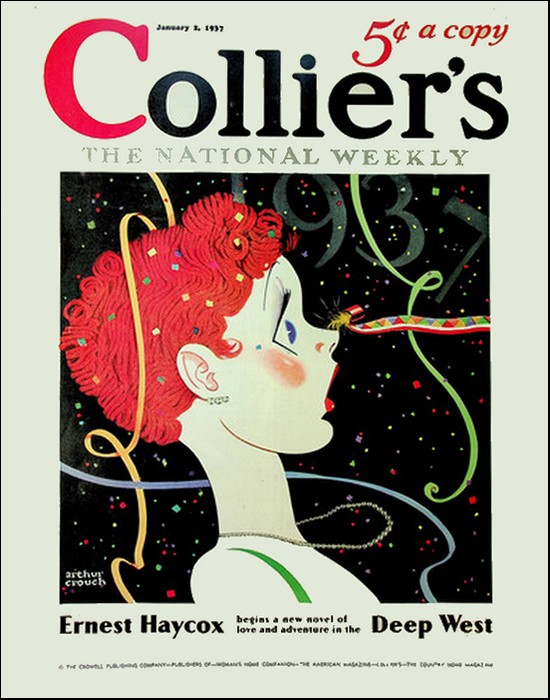

Collier's 2 January 1937, with first part of "Deep West"

"You know too much to live!"

Cash Gore's voice was touched by hatred. "You were a fool to ride here, Benbow."

Jim Benbow said quietly, "I came to tell you that I know this outfit is crooked. But I'm going to wait for proof."

"You can go on waitin'," Gore sneered.

"O.K.," Benbow said coldly. "But I'll be back. And I'll wipe you off the map, Cash."

An organized band of cattle rustlers was making life hell for the ranchers. Jim Benbow was set on breaking up the gang. But he was a law-abiding man and had to have proof that Cash Gore was boss of the desperadoes. Jim's knockdown fight to get that proof makes a fast and stirring yarn.

JIM BENBOW dropped off the train at Two Dance and stood on the platform a little while, watching the red and green coach lamps of the westbound slide away and vanish at last in the layered darkness lying over the vast dry sweep of this land.

A telegraph key clattered inside the station. The smell of coal smoke and steam lingered behind. Arapahoe Street ran gently upward between Two Dance's frame buildings, cross-barred with shop lights shining across the loose dust. Horses stood three-footed in front of Faro Charley's and farther along, by the gallery of the Cattle King Hotel, the high-wheeled stage was making up for its night's run southward to the reservation. Beyond town the low outline of Two Dance Range made a ragged silhouette. A freight engine's bell began to ring down the siding and Izee Custer strolled out from the thick shadows of the station house.

The two of them swung together and walked by silent agreement toward Faro Charley's, the matter-of-fact Izee Custer stretching out his legs a little to match Jim Benbow's broad stride. There was a six-inch difference of length between these two. "Get your chore done?" asked Izee Custer.

"Yes."

"Pete Cruze," murmured Izee, "is eatin' supper up at the hotel."

"Drop him word to stay there until I give the signal. I want this thing staged right."

Riders were wheeling out of the prairie darkness into Two Dance, swinging at the hitch racks, and lights flashed more brightly from all those buildings as the town woke to its evening's liveliness. Ed Swain came from the hotel, made one long jump to the stage's seat and sent his four horses away from Two Dance at a fast trot. Benbow and Izee Custer were at the open doorway of Faro Charley's, and here Benbow came to a sudden halt, his flat and high shape swinging in the saloon's full glow. Izee Custer laid his hand against Benbow to prevent collision. He lifted a round and stolid face and said: "Huh?" Afterwards he turned to see what drew Benbow's attention. There was a big clay-colored horse standing by the Cattle King porch.

"Yeah," murmured Izee. "Cash Gore came in about an hour ago."

Change stirred Benbow's long lips, a faint impatience cracked the habitual serenity he imposed upon his cheeks. His jaws definitely established the long borders of a big-featured face, shelving squarely at the chin. His eyes were a sharp gray with a light in them that could turn, as now, restless and exacting. Like a hidden heat unwittingly exposed. He had high cheekbones, minute weather lines slanting out toward them from his eye corners across a smooth and bronze-turned skin. When he let the pressure go from his lips they grew fuller.

"Connie's around somewhere, too," said Izee. "Came in this afternoon with Clay Rand. Clay's been at the poker table with Faro Charley ever since."

Jim Benbow stepped into the smoky warmth of Faro Charley's and stopped with a characteristic roll of his shoulders, catching the identity of the crowd at one quick survey. Mirrors flashed up a sulky brilliance in here and Price Peters pivoted from the bar and grinned at him. A few punchers from the Mauvaise Valley—a clannish district—made their own group at one end of this bar; and a man in a loud yellow shirt, looking like a rider on the loose, stood at the other end and whirled a glass between his fingers in a solemn isolation. Shad Povy, roustabout in Menefee's stable, lay full length at the foot of a wall, drowned in whisky.

There was a game going on at a corner table, with Faro Charley dealing and Clay Rand and two other men sitting in. Jim Benbow went over there to lay his hand quietly on Rand's shoulders. Rand looked up, a flushed and irritated expression all across his half-handsome face. When he saw Benbow a swift smile took the irritation away. He said: "How was Cheyenne, kid?"

Faro Charley called: "Open?" It was a thoroughly colorless voice. He let his glance lift to Benbow for a moment and then nodded, his stiff shoulders remotely stirring.

Benbow went back to join Izee and Price Peters; they lined up at the bar and in silence took their whisky. Price Peters had a horse ranch over on the edge of the badlands. Around thirty-five and a graduate of Princeton, '72, he already was beginning to turn gray. There was a kind of ironic reserve about him that repelled most people in the Two Dance country, a let-me-alone manner hard to penetrate. Only Jim Benbow had ever got behind that reserve to really know the man. They made a strange and steadfast group, those four—Benbow and Price Peters and the silently solid Izee Custer, and Clay Rand whose voice suddenly cut through the soft-drawled confusion of men's talk. "Throw this damned deck away, Charley."

The three partners at the bar looked quietly and comprehendingly at that scene. Clay Rand's cheeks, always highly colored, were florid with drink and the sting of bad luck. He tossed his hand to the floor. Faro Charley murmured, "Tough, Clay," and broke open another deck.

Price Peters said softly: "He's been droppin' his money there since two o'clock. Connie came in with him. Somebody ought to tell him she's probably ready to go home."

Jim Benbow pushed back the brim of his hat in a restless motion, these other two men closely watching him for some break in that tough and smooth and reserved expression. "It's his fun," he suggested, and then looked indifferently at the yellow-shirted stranger standing by the end of the counter. The man's eyes lifted to him for one brief moment, and slid away. Afterwards Benbow's turning glance reached the dead-drunk Povy on the floor. Presently he was smiling in a soft way, in a way that altogether changed him. Both his partners turned to see what had caused that; and by common impulse they walked over to the corner, standing above Povy and commonly speculating on the man.

Benbow said: "Povy, wake up."

"He'll be like that till tomorrow morning," said Custer. "Takes him all night to sleep off his jags."

"You sure?" drawled Benbow.

Izee Custer's eyelids slowly came together and a bright light began to glitter. They stood there, silently considering. Chips made a brittle clack in the room and one of the Mauvaise Valley punchers laughed and struck the flat of his palm against the bar. The steady blang-blang of a freight engine's bell ran over the town's housetops and afterwards they were all thinking of the same idea and considering its possibilities. Benbow waggled his head to Izee who instantly reached down to catch Povy by his armpits and drag him into the saloon's back room, Benbow and Price Peters following. Benbow closed the door.

"The train?" said Price Peters.

"Sure."

"Now wait," Izee broke in. "A little blood—"

Benbow murmured: "Suppose he's got a gun anywhere?"

"An idea," said Price Peters, and made for the back door. Izee Custer called, "Wait for me, Price," and trailed him into Two Dance's rear alley.

Benbow stood there with a little smile breaking its way across his long lips. The ragged light of this back room slanted across his cheeks, turning them irregular and remotely hard. Out front, Clay Rand was swearing again, whereupon Benbow's smile quit showing. He straightened and a dark unruliness had its way with his eyes while he stood there alone, vanishing as soon as Izee and Price Peters came back. Izee had a tin cup in his hand; Price had found a rusty .32. "It was under his bunk in the stable," said Price. "It's loaded."

Izee said: "Ben Dairy's wife will sure kill me when she finds out I slaughtered one of her hens." Leaning down he sloshed the contents of the tin cup deliberately across Shad Povy's shirt, that chicken's blood making a wide, irregular stain.

The three of them stood back to observe the effect. "Better hustle," said Price Peters. "The freight's due to pull out."

Izee and Benbow seized the completely indifferent Povy by head and heels and walked out the back way, Price Peters following. Half down the back alley, Benbow thought of something else. "Should have a couple empty shells in that gun."

Price fired the gun twice at the sky. The freight engine was hooting for the switch and the long string of cars jerked into life. The three partners made the moving caboose on the run, lugging Povy inside. A brake-man reared up from his bunk, took one startled look and broke into bitter protest.

"Listen, you fellows. No dead men in here!"

"You'll be stopping at the Mauvaise loading pens," said Benbow. "Joe Russell will be there. You tell Joe that Jim Benbow said to pass Povy along."

"What?"

"He'll know."

The three partners dropped off the caboose as it rolled by the station house. They stood there a moment, and then turned back up Arapahoe Street. "You sure Povy won't wake up till morning?" asked Benbow.

"Never does," said Izee.

"He'll be up in the Yellow Hills by then."

They were in front of Faro Charley's, and Price Peters had begun to laugh immoderately. Benbow said, "I'll be back," and went on toward the Cattle King alone. Constance Dale came slowly down the galleried porch to meet him. She had been standing there; she had been waiting there for Clay Rand.

Benbow pulled off his hat, speaking evenly. "If you're ready to go home, Connie—"

"Where's Clay?"

"I'll get him."

She reached out and touched him with her hand, rooting him to the spot. "Let him play poker." Against the thick shadows of the porch her supple form stirred and made its pattern of grace for Jim Benbow; a stray sliver of light from the hotel window came out to touch her face, and though her eyes were hidden from him at the moment he could tell by the lift of her chin and the slow, cool way she spoke that she had been waiting long for Clay, and was hurt by the wait. He knew her better than she knew herself—this only child of old Jack Dale, Hat's owner. She could ride the hell out of him, Benbow thought, when her anger was up. And she could go still and distant and try to hold her feelings away from him. One thing or the other—it was that way with them most of the time. But she couldn't hide much from him. She stood soldier-straight, still touching his arm, and her lips made a faint and sweet line in smiling. A strong-tempered and dark-headed girl who could have her way with him any day, and knew it.

"I'll go home with you," she said. "When you're ready."

He said: "You had better break Clay of that habit before you marry him."

"I don't break my men, Jim."

Pete Cruze appeared in the Cattle King's doorway, thinly silhouetted against the light shining through from the hotel lobby. He said: "When you want—"

Benbow's voice sang its soft and thin and wicked tune at Pete Cruze. "Get out of sight." Pete Cruze faded and Constance Dale's head lifted another inch and her eyes were suddenly in the light, round and puzzled and cool. But she didn't ask any questions, knowing Jim Benbow too well. Benbow's fingers were rolling out a cigarette; she could see his narrowing lids deliberately shut away his thoughts. There was a man pacing down the walk slowly, coming beside the gallery of the Cattle King. In another moment she turned to find Cash Gore paused there. Gore said: "Evenin'."

"Good evening, Cash."

Benbow pulled his attention from the cigarette, placing it on Cash Gore with a deliberateness, and there was then in this cool, windless night the faint intimation of some dry and deadly thing creeping up. Gore was a high and narrow shape on the walk. He had paused and removed his hat out of courtesy, his rusty red hair vaguely gleaming under the hotel lights. There wasn't any way of telling what his interest was, for his eyes were too closely guarded to be read and a mustache dropped its straggling ends across his mouth to hide whatever expression might have been there.

"Cheyenne still alive?" he said.

"Yes," said Benbow.

Cash Gore nodded with a kind of saturnine indifference and went on. Benbow dropped his attention back to the cigarette, yet Constance knew he was carefully listening to Cash Gore's footsteps tread toward Faro Charley's saloon. Benbow had mannerisms even in his silence; he had little expressions that betrayed his mind to her always' observant eyes. It was something she could not help, this deep interest in what he thought and what he felt. She had known him for years, sometimes hating him and sometimes almost loving him, and never able to release herself from the turbulent pull of his personality.

He bent toward her. "Tell that fool Cruze," he said in a soft-running murmur, "to stay out of sight until he gets his orders," and wheeled away from the porch.

Six horses stood in a row before Dunmire's stable and men crouched at the base of the stable's wall, their cigarette points glittering through the dark. Cash's men. When he came into Faro Charley's again he observed Cash Gore standing alone at the bar, the shackle-jointed frame eased against it and the drawn and quick-tempered face bowed over a glass of whisky. These things Benbow saw in one rapid survey—the stranger with the yellow shirt still immersed in his own isolation, Izee and Price Peters grouped about the poker table, Clay Rand grown more flushed and more irritable from his run of luck. Benbow put his arms on Clay Rand's chair, but his glance went over to touch Izee Custer and tell Custer something; and then dropped back to Clay.

Custer said, to nobody in particular: "Hell, I've had enough of this place," and left the saloon.

Benbow bent over to speak quietly to Clay Rand. "Connie's ready to go home."

"Sure," said Clay Rand, and looked at his cards. There was a bet made. Rand called it and lost. He put both his palms on the table, staring at Faro Charley. His eyes were a deep blue, and unstable with sultry anger. All this blond-headed man's features were full and bold. Benbow said: "Come on, Clay. We're all ready to ride." Clay jerked his head around. "Good God, Jim—let a man alone!"

Benbow said, "All right, kid," and wheeled away from the table, showing no expression. But Price Peters, still at the bar, sent a rapid glance from Benbow to Clay Rand and gently shook his head. Cash Gore swung to look at this scene with a slicing, taciturn interest.

At that moment Pete Cruze walked into the saloon, a young and grinning boy with an oversized Adam's apple. He saw Jim Benbow and stopped, and an expression of uneasiness came to his face. He said uncertainly: "Hello, Jim."

Benbow stared at Cruze. "What you doing here, Pete?"

"Just rode in for some tobacco."

"Who's taking your place at the line cabin?"

Pete Cruze dropped his eyes. "Well," he said, "nobody. I didn't figure to be gone long."

Benbow said: "Damn a man I can't trust. You had orders to stay there. What have I got to do—give you a nurse and a guardian?"

"Jim," said young Pete Cruze, all at once losing his uneasiness, "don't talk to a man that way."

The room turned still and the poker game stopped. Clay Rand lifted his head, at once alert and puzzled. Nobody said anything for a moment. Cash Gore swung his lank shape completely around to see what all this was. Benbow spoke with an irony that hurt: "How do you want to be talked to, Mr. Cruze?"

"Well," said Pete Cruze stubbornly, "not like that."

Benbow said: "My apologies for showing a lack of respect for your feelings. Of course, Mr. Cruze, no gentleman wants to be tied down to one spot when he's out of tobacco. I'll just relieve you of the trouble."

"Listen—"

"You've got your walking papers from Hat," stated Benbow bluntly. "Right now."

Pete Cruze put his hands into his pockets and pulled them out. He got redder and redder and his Adam's apple slid up and down. He murmured, "Well, shucks," and then simply bawled at Benbow, "to hell with your damned job! I quit before you fired me!" And having said that, he stamped from the saloon the picture of mortal affront.

Clay Rand said: "Kind of a tough guy tonight, Jim. Who stepped on your foot?"

Benbow had an answer for Clay, a wickedly even answer: "This place seems to be full of gentlemen of leisure. Don't let me trouble your game, Clay."

Clay Rand's ruddy cheeks took on an instant set. He laid down his cards. "You're a little too high, Jim. I don't work for Hat, and my time's my own."

"I'll remember that," said Benbow and turned to Price Peters. "Riding my way?"

The stranger in the yellow shirt moved out from the end of the bar. "If you're in the market for a rider—"

Benbow had started for the door. He wheeled and looked down on this lesser-built man whose face was flat and unsentimental and indifferent. He had a crooked nose scratched whitely by a scar, and a pair of eyes incredibly watchful.

"Where you from?" said Benbow.

"Arizona," put in the stranger.

Benbow said briefly: "It's tougher up here, Arizona."

"Do I look easy?" asked the stranger with a faint insolence.

Benbow stared at the man; and presently grinned in a thin, appreciative way. "If you find the Hat outfit tomorrow, I can use you. Coming, Price?"

Price strolled over, going out of the saloon with Benbow. The man so suddenly named Arizona went back to his corner and wigwagged silently for another drink, Cash Gore's glance following him with a bitter-bright attention. Clay Rand started to lift his cards again. He looked at them, and dropped them abruptly and got up from his chair. "See you next week," he told Faro Charley, and started for the door.

But just before he swung away his glance lifted carelessly and touched Cash Gore across the room. Cash Gore met that inspection evenly and then swung his narrow shoulders back to the bar. He put both elbows on it and his head rolled forward and thus he stood, still and taciturn and engaged in his own secret thoughts. Once his lips moved and he slid a covert look at Arizona, as though some sudden and powerful idea had stirred him; and dropped his head again.

Clay Rand left the saloon, catching up with Benbow and Price Peters. The three of them walked on in thorough silence for a short distance. Afterwards Rand laughed and put his arm on Benbow's shoulder. "Forget it, kid. I lost a hell of a lot of money tonight and maybe I spoke too fast."

"Sure," drawled Benbow. "Sure," and all at once the feeling between these three men changed and the strain went away. Price Peters spoke with an open relief. "That's better. I don't like to hear you boys wrangle."

Clay Rand observed: "Never saw you work on a man like you did Pete Cruze."

Benbow said: "He was supposed to stay where I put him."

They came to their horses in front of the Cattle King. Izee Custer stood there, talking with Constance Dale; and Jim Benbow saw how Connie's face came around and showed its faint anger when Clay Rand went forward to her. He didn't, Benbow observed, apologize to Connie for his delay. It wasn't in the big, blond man to make amends that way. He had another way, which was to smile at the girl and let the careless, teasing melody of his voice have its effect. "I tried to win enough off Faro Charley to build you a mansion in the Yellow Hills, Connie."

"And didn't?" said the girl.

"I guess Faro Charley will be buildin' the mansion," explained Clay Rand wryly. "Well, another day, another kind of luck."

"I suppose," said Connie in a small voice.

They went out to the horses and swung up. Paused a moment, Jim Benbow looked back toward Dunmire's stable to observe again the shadowy shapes of Gore's men. They had been there all this while, motionless and speechless, and waiting for Gore. Clay Rand was laughing with a deep and reckless amusement at something Connie had said or done; and now Connie turned her horse and fell abreast Benbow. There was a little interplay of feeling here Benbow had missed, for he saw the sudden and desperate set of her face. Somehow Clay had hurt her again. She said, to Benbow, the very coolness of her tone telling him of her stifled pride: "Ready to go, Jim?"

Square Madge Reynolds crossed from Donlake's store to the Cattle King. Near Benbow she lifted her head—this big and buxom and still attractive woman—and smiled at him and spoke with a quick favor: "Hello, Jim."

Benbow lifted his hat, and then she had gone into the Cattle King and Benbow put his horse to a trot, leaving Two Dance behind. Ahead of them lay the formless shape of Two Dance Range. There was a faint and wild-scented wind crossing this night and in the bitter-black depths of the sky all the stars were glittering.

"You have friends in strange places, Jim."

He said, "I take 'em where I find them," and let it go like that. She was thinking of Square Madge, and she would remember that against him. Or maybe it would be in his favor. He never knew about Constance Dale. She had a way of judging his life and sometimes of analyzing it for him with a frankness that was startling, as though her interest in it was too deep to be ignored. As though she had a share in his life. Well, he had been Hat's foreman five years and there was little reserve between them.

Clay Rand was chuckling out his pleasure at something Price Peters had said. Things, Benbow thought, ran this fast for Clay. He could curse at his luck over the poker table; and forget it soon, and find things in the night to set off his gay humor. Always this man lived by extremes, and had his way of making people love him.

Rand said: "What took you to Cheyenne, Jim?"

"Stockmen's convention."

"That all?" questioned Rand idly.

"Yes."

"You can be a close-mouthed sucker," jeered Rand.

Izee Custer's voice came from the rear. "A good habit for these times."

"So," said Rand, a soft curiosity in his talk, "there was something else."

"No," said Benbow. It was the way he said it. Talk stopped there and they ran up the Two Dance grade in silence and alternately walked and cantered along the pine-guarded alley that was the summit pass. Deep in the timber they saw the brief flash of Summit Ranch and afterwards, falling down the slope into the black sweep of Two Dance Valley, the faint and far-spaced glint of isolated outfits began to break that deep plain's mystery. They passed Gay's store and presently reached the valley floor. By tacit agreement Benbow and Peters and Izee Custer drew ahead and halted, leaving Constance Dale behind with Clay Rand. Benbow rolled himself a cigarette, hearing Clay Rand's talk rise and fall in a kind of amused and melodic bantering; and hearing Connie's quiet answer. She would be forgiving him for his sins, as she always did, as all people forgave Clay Rand. There was silence then, back there. After a while Connie said: "Clay!" and Benbow scraped a match across his leg to ignite the cigarette. The planes of his face, against this sudden yellow light, were flat and hard. The light went out as Connie came up alone. Clay Rand was racing off to the southeast, taking the short cut across the valley to where his own small outfit, Short Arrow, lay at the base of the Yellows. They went on, hearing his voice calling cheerfully back: "So long!"

A mile farther ahead Price Peters turned with a brief "good night," and struck for his own place down toward the badlands, westward. Benbow and Connie pressed forward, while Izee Custer dropped discreetly back; and after another forty minutes of steady riding along the flat width of the valley they raised the Hat's lights and passed into its yard.

BIG JACK DALE'S voice emerged from the solemn depths of the porch. "That you, Jim?"

Connie said, openly amused: "Is it your foreman or your daughter that interests you the most?"

"My foreman," drawled Big Jack Dale, "is a necessity."

Connie slid from her horse and went into the house, dropping her father a kiss on the way. It was as though she made a reluctant concession to Big Jack; and as though he accepted it reluctantly. There was, Benbow thought, always that unsentimental manner masking the real affection between those two. Izee Custer took the horses away and Benbow stood on the porch steps, idly smoking out his cigarette. Big Jack Dale shifted in his chair and sighed, and said:

"Get your business done?"

"All the cattlemen are cryin' about the rustlers this year," said Benbow. "It's the same story, from Jackson's Hole to Julesburg. We're bein' hurt. So's everybody else. Seems like there's a reason."

"A reason won't help spoiled beef," growled Big Jack Dale. "But what is it?"

"The little boys are growing into big boys. The big idea hit 'em all at once, which is that it's easier to gang up and make a real business of rustlin' than to play a lone hand. There's gangs all over the state. They got a system. A man planted in the outfits to hear things. A bunch to run the stuff. A bunch to hold it somewhere, a long ways off. Another bunch to peddle it. It's what all the stockmen in Cheyenne say."

"You think it's that way here?"

Jim Benbow dropped his cigarette, grinding it beneath a boot heel. He sat down, stretching his long frame forward, pulling his big hands together. Hunkered over that way he listened to the shallow river cluck and ripple its way through the willows near the porch. "I mean to find out," he said.

"How?"

"I fired Peter Cruze in Two Dance tonight. And hired another man."

"What other man?" said Dale. "Another man."

Big Jack Dale's amusement came along the dark with a husky sibilance. "All right, Jim. All right." He got up then and stamped his walking stick three times on the porch flooring; and went inside the house.

Benbow rubbed his hard palms together, and held them still and stared at a point of light pulsing far across Two Dance Valley, which was Rho Beam's chuck wagon making camp near the base of the Yellow Hills. But he wasn't thinking of Rho Beam or the chuck wagon. It was the softness of Constance Dale's voice when she spoke to Clay Rand that kept ringing like the gentle echoes of a bell in his head.

She came out of the house quickly, passing him and turning to face him at the foot of the porch. He saw the oval of her face shining through the shadows, with that streak of darkness lying like a velvet strip across her eyes. A straight-bodied girl, full of fire, full of hidden wealth. Something struck him and left its fresh shock. He kept remembering her as a leggy kid, built like a boy, without hips and without bosom; but he was seeing something he hadn't seen before. She was a mature woman now, more reticent than she had been; modeled in the way a woman should be.

"Jim," she said, "you're a glum man."

"As usual."

She murmured, "As usual," and sank beside him. Suddenly she had tipped against his shoulder, without sound. It startled him. She was too proud to-cry, but he could feel her body trembling; she reached out to catch his hand and to grip it in the way of a girl somehow frightened.

He said, as stolid as he could manage: "Buck fever?"

"I'm supposed to be happy."

"Hits some people in strange ways."

She stood abruptly up, and spoke with a swift outrage. "Damn you, Jim Benbow! Don't be so brutal."

He didn't answer that for a moment. He sat there, hands idle and his head inclined toward the ground. After a while he said: "Let a man alone, Connie. I can't help you. I can't even help myself."

He heard her swift, sharp sigh. She murmured: "I'm sorry, Jim. So sorry."

After she had gone into the house he got up and circled the yard, keening this night for what it held. The day's heat was out of the earth and autumn's chill flowed along the valley. Turning back to the bunk-house, he heard the fast drumming of horses come up the Two Dance road; and in a little while made out a string of riders running by, bound for the Yellow Hills. He could not see them, but he knew who they were. This was the way the men of Running M—Cash Gore's men—used in homeward travel.

Around eight o'clock that evening the train crew laid

the loose form of Shad Povy before Bill Russell at Mauvaise

station. Part of Russell's crew happened to be there and

these men took up Povy and carried him to the near-by

ranch house. An hour later, when the Rocky Springs stage

came by, they put Povy aboard. At midnight, following his

instructions, the driver stopped on the long grade leading

up Yellow Hills and lugged Povy to a comfortable spot in

the pine timber and left him there. Thus, having come sixty

miles from Two Dance in a dead stupor, cheerfully and even

enthusiastically cared for along the way, Shad Povy at last

rested on the upper edge of Two Dance Valley, stained by

blood and with two bullets fired from his gun.

Benbow was at the corrals with Custer and three other Hat men when Arizona rode up, shortly before sunrise the next morning. Arizona eased himself in the saddle and for a moment let his glance have its sharp way with the men scattered about the place. Physically he was not a match for any of the Hat crew, and yet there was something about him that made these other men take their careful look. A steely calm covering the hint of a wildness fitfully asleep. A way of absorbing the world with his eyes.

He said, to Benbow: "You still want a hand?"

Benbow kept his attention on Arizona, as though his thoughts were not fully satisfied. But he spoke to Izee. "Take him over to the line cabin Pete Cruze had."

Custer went off to saddle his horse. Arizona let his legs hang full length, free of the stirrups; and rolled himself a smoke. None of the other men broke the silence and presently Arizona said: "Anything about this line cabin I ought to know?"

Benbow said: "You look like you could take care of yourself."

"My habit," said Arizona briefly.

"Stick to the habit," answered Benbow. "It's all I've got to tell you."

"That kind of a job," observed Arizona, the lids of his eyes drawing together.

Izee Custer trotted up. Arizona joined him and without further parley those two rode over the ranch bridge and fell into a steady canter southward across the flats of the Two Dance. Presently they were a pair of diminishing shapes under a sudden burst of sunlight, the color of Arizona's yellow shirt dying out. Gippy Collins, who was only a kid, spoke up.

"Well, where's Pete Cruze then?"

"Fired," said Benbow, and turned to his own horse. In a little while he was riding northward through the swell of a fine, brisk morning with a flawless sky above Two Dance Valley ran this way twenty miles with scarcely an undulation, with only the willows of the river breaking the flow of the flat earth. On the north lay the low Two Dance Range in a kind of continuous wall; to the south the ramparts of the Yellow Hills shouldered abruptly up from the valley floor, dark-streaked by pine timber. In the foreground little spirals of dust were rising from wagons hauling hay out of the river meadows. This was the heart of the valley, these miles of Hat lying between the hills and rolling east to Mauvaise siding fifty miles removed. He could not see the quarters of the-neighboring outfits, but he had them all in his mind clearly. Rand's Short Arrow tucked in a crease of the Yellows, twelve miles off, Running M two miles west of Clay, its houses backed against the mouth of Granite Canyon, Diamond-and-a-Half more remotely placed in the Yellows. Behind him, in the west, Block T and The Cresent and Price Peters' horse ranch verging off into the chalky color-streaked gulches of the badlands. With a few ester here and there.

This was the Valley. The year was 1884 and Benbow, cruising on through the strong light of the day, had only to close his sharp eyes to recall in his mind every trail and spring and boundary mark within an area eighty miles square. This summer was his fifth season as Hat's foreman. And his tenth since, as a wild and foot-loose kid, he had come up the trail from Texas. It hadn't been so long ago that Indians made their lodges along this river; and he could remember seeing Sam Yancey's body lying up by the breaks, naked and without scalp.

Riding this way, studying the ground and horizon always for news, a man often pondered strange things and reached strange answers. Only, sometimes there were no answers. That was what he thought this morning. A man fooled himself into believing he could drift with the seasons, the seasons not changing and himself not changing. It was hard to realize he wasn't a footloose kid any more and it was hard to think that Connie Dale, within the reach of his voice for so long, would presently marry Clay Rand. That would be the break—the end of something. It was hard to figure beyond that break. Was that what Big Jack Dale, hunkered down in his porch chair, was thinking too?

This while, his eyes were running the deep reaches of the valley. He had seen Arizona and Izee Custer vanish at the base of the Yellows and later that morning he watched Izee travel back, shooting up dust spirals as he rode. It was beyond two o'clock when Benbow reached Hat again to find Izee crouched on his heels in the shade of a corral, taking ease. Izee opened his eyes, said briefly, "He'll do," and closed them again.

Benbow ate a solitary dinner and went to the office adjoining Hat's big living-room. Jack Dale sat on his customary wide leather chair, his feet hoisted to the sill of an open window, his attention strayed somewhere beyond the thickening whorls of fall haze lying across the Two Dance. Benbow sat up to the desk and opened the work book. He wrote in it, "Arizona, hired," and added the date—and put after the name a faint cross. The cross represented something in his mind, something he couldn't write in the book.

He set the book aside, and remained there before the desk, his solid fingers idle; and his mind narrowing down to Hat's business. All the life of the ranch, its people, its livestock and water rights, its bank account and its bills on Omaha were there before him, set down by his own hand. He knew more about Hat than old Jack. He represented it, he operated it, he made most of its decisions. Considering the desk, more and more involved in his thoughts, Benbow could hark back and realize how deliberately Jack Dale had thrown this on his shoulders until now the old man was like a silent partner. It was Jack Dale's life—this big and sprawling outfit which lay chunked out between the twenty-mile sweep of the Two Dance and Yellow ranges. But it had come to be his, Benbow's, life too. Until nothing else mattered much. He was, he thought, a fixture, a part of the place.

Yet there was that shadow of change over him, unsettling him. When Clay married Connie, it would properly be Clay who sat at this desk. There wasn't room for two riding bosses on Hat.

Jack Dale said: "Where's Rho Beam?"

"In the Yellows, with the chuck wagon."

"Beef should be heavy this year."

"We'll be shipping out of Mauvaise all the way till early winter. The market is good."

By and by Jack Dale turned his head toward Benbow to catch a careful look. It wasn't like this big, bronzed puncher to be dallying before a desk late of a fall afternoon. Benbow was a restless one, a driver, a fighter. But he sat here, with the steam out of him; with his tough cheeks drawn into tight lines.

Jack Dale said, indolently: "When I was young I had a fever to travel. So I rode till I was gant. Like a longhorn starved for salt and lookin' for it." He let that lie in the still air. And then he said: "You're twenty-five, Jim. Don't your feet fiddle?"

"I got that knocked out of me early, Jack. When I was fourteen, coming up the trail from Texas."

"Man's got to be a little wild when he's young," murmured Dale. "And let the wildness spill. Or he goes sour, like a bad horse. Or flat, like a hand-fed deer." He cleared his throat. "I observe there's some hell in you. It's why I sent you to Cheyenne—to get drunk and wind up in the cooler. You didn't do it."

"Think that would help, Jack?"

Dale's glance sharpened on Benbow. Afterwards he shook his head. "No, I guess that ain't it." But there was something in him that stirred his habitual silence powerfully and had to come out. In a little while he spoke again. "A few women need gentle handling. But it's my observation the rest of 'em like a man better if he makes them cry now and then. Seems to me women have a habit of just admirin' men that treat them softly and with understanding—and fall in love with the kind that give 'em storm and trouble. They like the rough way better than the smooth."

A rider galloped impetuously into the yard and stopped and a woman's voice—Eileen Gray's quick, expressive voice—sailed through the house. "Connie." Presently both women were on the porch, talking. Benbow got out of his chair. He stood in the middle of the office, his tough and flat shape making a high presence there. He looked down upon Old Jack Dale's grayly passive face with a full understanding of what the Hat owner was trying to tell him. He shook his head. "It will have to be the way it is, Jack," he said quietly, and strolled out to the porch.

Jack Dale settled more deeply in his chair. Indian summer's haze stirred like fire-smoke all across the Two Dance Beyond, the ramparts of the Yellow Range were dim and strange—just as they had been fifteen years before when his wagons had ventured to this choice and dangerous ground of the Sioux. Isolated images rose before him and passed on—of men he had known so well, of things he had done in his heartier years. But his thoughts, irritably insistent, returned to this Jim' Benbow who was so much like a son—and in whom he had so deliberately entrusted the management of the ranch. Now after five years he saw that hope die; and like an inveterate poker player silently discarding a poor hand, he threw his particular ambition away. And sat wholly still in the chair, watching the day turn on.

Benbow stood against a porch post watching the two girls. Eileen Gray's glance came to him immediately and took a personal notice. She said in a teasing voice: "Don't be so serious, Jim. I'm worth a smile, am I not?"

It drew the smile out of him and then Eileen, satisfied with her accomplishment, turned toward Connie and the two fell to talking about the wedding of the following week. Eileen was marrying Joe Gannon who ran a one-man spread over against the Ramparts.

There was a contrast here Jim Benbow noticed clearly. Eileen Gray was like a flash of restless color, slim and laughter-loving, and with graphic features that kept registering all the sudden changes of her temper. A pretty kid. One that wanted men to like her and was hurt by any man's indifference. Connie sat quietly by, a taller girl and outwardly a calmer one—hearing all that Eileen said and meanwhile listening beyond the words for things left unsaid. Once her eyes lifted to Jim Benbow, as though wanting to know what he thought.

There was a rider coming across the flat on a steady lope, which would be Clay Rand riding in to see Connie. Benbow built himself another smoke, the secret knowledge in his head making this picture very sharp to him. Connie's glance rose to that approaching figure and all the gravity of her face softened, changing the expression of her eyes and mouth—even though she was trying to hide that change. When the hoofs of the horse struck the hard earth in the yard Eileen Gray swung around and then the laughter went immediately out of her, replaced by a dark and half-haunted look. Benbow saw how completely she threw her heart at Rand; and then he pulled his eyes from the girl, silently enraged.

Rand slid from his saddle and came on forward, a high and gallant shape against the sun; he removed his hat and his smile was as it always was on that flushed and handsome face—softening all resentment. He said, "A picture of beauty for a fact," and then his chuckle ran the dry air. "Marred only by the face that's shocked a thousand men. Meaning Hat's hard-boiled foreman."

"Maybe I'm in the way," drawled Benbow.

"Just came over to protect my interests," grinned Clay Rand. "You're runnin' me a tough race."

Benbow said: "Me? I was disqualified at the post, Clay. I grew up with Connie and she knows me too well."

Clay drawled: "Never let a woman know you too well, kid. They like a little mystery."

Connie said smoothly: "If it's mystery you want, Clay, you'd better cover your tracks a little better."

Clay Rand's ruddy cheeks showed a deeper flush. It was a thing that stabbed into his pride; he showed that. Then Eileen Gray stirred to attract his attention and spoke in a begging way. "You coming to my wedding, Clay?"

"I never miss weddings, Eileen."

They made a three-cornered group on the porch, with Jim Benbow in the background, out of the scene. There was something here that excluded him definitely, and he dropped his cigarette on the porch, ground it beneath his foot and returned to the office to find Jack Dale asleep on the corner couch, his face covered by a newspaper. Benbow drew out his hay and stock record and began to work at it. On the forks of the Two Dance five hundred tons. At the willow meadow thirty tons. The Indians on the reservation were saying it would be another tough winter—a starving winter. Sometimes they were right and sometimes they were wrong, but in the cattle business a man had to be smart. Smart with beef and ignorant in the ways of a woman. It seemed to be his story.

He worked on with his mind thus split. Hay and beef and Clay Rand and Arizona and himself and Connie Dale—and the far darkness of Hat's future. Another six hundred tons along the upper corner of the river. His big fingers moved with a steady regularity, pressing the pen point into bold strokes. The voice of Clay and the girls rose and fell along the porch. The day droned on and the hay hands were riding into the yard with the late long-flung shadows. Somewhere Izee said in a quick voice: "Jim—come out here." It was five-thirty then.

When he got to the porch Izee simply pointed toward the farther sheds of Hat, around which came a rider at a jiggling trot. He rode a scrubby horse barebacked, with a piece of rope twisted Indian fashion for a hackamore; a little man all bent over and having a hard time of it.

"Povy," murmured Izee, in his blandest manner. Hat's men were moving forward to see what this was. Clay Rand said: "What is it?"

Shad Povy brought his sweat-caked horse to a stand at the porch. Dry blood stretched all across his shirt and he had the expression of a fugitive on his peaked face. He tried to ease himself and almost fell off. He looked at the encircling hay hands and back to Benbow. A hoarse croak came out of him.

"Jim, before God, I dunno how it happened! I'm a condemned man! Last night I killed a fella! Gimme a fresh horse. I got to leave the country."

There was a shocked silence on the porch. Izee put his hand across his face slowly and looked at Benbow. And then Benbow sat down suddenly on the porch steps and laid his broad palms on his knees for support and let go with a deep, uncontrolled shout of laughter.

Povy said: "What the hell, here? I—"

His lips were moving, but nobody heard what he said. The whole yard full of men were at once whooping, as though they had gone crazy. Izee's grin got broader and broader; and Benbow seemed to be crying, to be praying. It went on like that for a full minute, with Shad Povy staring about him, his expression beginning to break. He said, "Aw," and his jaws dropped. All at once he jerked up the hackamore rope and yelled out: "Damn you, Jim! One of these days you'll go too fur!" And afterwards he galloped out of the Hat yard, his skinny frame bouncing a foot at each forward surge the beast made, the wild howling of the collected Hat crowd following him mercilessly.

Connie said: "You ought to be spanked, Jim Benbow."

Clay Rand stared at Benbow. He hadn't laughed much at the joke. He spoke now with a faint malice, a thin note of envy. "Why didn't you let me in on this last night?"

Benbow got to his feet. He had to wipe the tears out of his eyes. He only lifted his hand at Rand and then went down the yard with Izee Custer, both of them howling.

The supper triangle began to bang behind the house and the crowd broke for the low, long ell running back from the main quarters. The sun dropped over the western badlands in one fast flashing sheet of flame; and violet began to flow immediately across the valley. Eileen said: "I've got to hurry," and went out to her horse. In the saddle, she looked down at Clay Rand in a way that was quiet and rigidly unhappy. "I hope you'll like this wedding, Clay," she said, and then raced out of the yard.

Connie Dale rose from her chair. "Staying for supper?"

Clay Rand shook his head. "No. What did she mean, Connie?"

Connie looked at him. She had a way of going quietly angry that always turned her face slim and pointed and proud. "Clay, I'm not as much of a fool as you might think. Your affairs aren't very mysterious."

He came up the steps to her immediately, not smiling any more. He said: "Connie, can't you be charitable to a man?" She started to speak, but he bent his blond head down and kissed her. They were like this for a moment—long enough for Benbow to see them when he came back from the bunkhouses. Clay stepped back, serious and strained and having a rough time with his feelings.

"I think I'd always forgive you," murmured Connie Dale. "It's something I can't help."

Benbow swung wide of the porch, going deliberately away from it. Clay Rand clapped on his hat. He stood a moment before the girl who was so stirred, who so deeply showed the way of her heart. "Hope for a sinner," he said gently. "Never change toward me, Connie. Never mind what happens—never change."

"Stay for supper."

"No," he said, "not now," and went to his horse and rode away. Connie watched him swing out across the valley toward his ranch far over at the foot of the Ramparts. Dusk whirled along the flats in wide blue streamers.

IT was dusk and then it was dark, with Old Jack and Connie and Benbow on the porch. The hay haulers and the few home ranch riders were grouped down the yard by the bunkhouse and somebody had brought out a guitar, playing "Buffalo Gals." A breeze ruffled up the dying earth-heat and dust and hay smell was very strong. Far over in the Two Dance footslopes the lights of Gay's store were winking and vanishing and winking again. The sound of riders made a trembling echo of! in the stillness—riders coming on fast.

Old Jack Dale said: "Takes me back. We used to sit here and listen to horses comin' hell bent like that and wonder if it was the Indians. Trouble out of the Yellows. The Two Dance hills never meant any grief. Riders, from that way meant good news. But it was always trouble when they came from the Yellows. Time goes too fast. Cheats a man. Promises him a lot of things when he's young. All of a sudden he's old and it's time to go."

"Dad," murmured Connie Dale.

"Not complaining," said Old Jack Dale. "I've had my fun."

Off yonder the rhythm of the riders was abruptly broken; and afterwards one single horse rushed along the road past Hat, and disappeared. Benbow had been leaning against the steps; he sat up at once, listening into this night. Jack Dale's chair creaked and the old man said: "Which is odd."

Izee Custer's short and rolling shape appeared in the yard. He came on to the foot of the porch, not saying anything, the point of his cigarette making a red hole through the shadows. The lone rider's horse sent back its diminishing echoes and then they ceased entirely. But there was something on the edge of the Hat yard, something that stirred and stopped. Benbow rose. He said, "Put out your cigarette, Izee," and watched that glowing point drop to the earth.

There was a horse drifting in, the shape of it breaking vaguely through this darkness; riderless yet with some low shadow across the saddle. Benbow stared at that a long moment and then murmured, "Bring a light, Izee," and walked out from the house.

The horse stopped and threw up its head, expelling' a draughty breath. Benbow said, "Easy, easy," and took his time. But when he caught the dragging reins he stood fast, at once identifying that burden lashed across the saddle. A man there. His voice ripped the shadows. "Hurry with that lantern."

Men ran on from the bunkhouse. Old Jack Dale challenged him from the porch, "What you see?" Izee trotted forward with a lantern. He came around Benbow and held the light full against that pony's burden. They saw it at once.

This was Arizona, thrown across the saddle and tied there like a sack of meal. His head hung down and his arms hung down and his face was turned to chalk; and he was dead.

Izee said in a singsong voice, "Wait," and reached out to a bit of paper fluttering on a thong attached to Arizona's neck. He passed it over to Benbow, who smoothed it against his knee and held it before Izee's lantern. It said:

Here's your range detective from Cheyenne, Benbow. You didn't fool anybody.

All Hat's crew stood around the horse in a still, shocked circle. Jack Dale came up to have his quick look and Connie walked forward and put her hand on Benbow's shoulder, the sound of her breathing irregular and very, small. Izee Custer saw the girl's white face staring at the pony's burden and instantly swung around, putting his body between it and die light. There was a feeling here that dragged its spider-like tentacles across all of them, screwing up their nerves. Izee Custer's dark eyes lifted to Benbow to reveal a brighter and brighter glitter.

Benbow moved suddenly through the circle, leading the horse down the yard. Izee handed his lantern to somebody else; in front of the crew's quarters he helped Benbow unfasten the dead Arizona and lift him inside to one of the bunks. The light traveled forward from hand to hand, shining down on the man again and showing the blue, pencil-pointed hole centered in his forehead.

"Rifle bullet," said Izee, voice plunking that long stillness like a rock dropped into a well.

Gippy Collins, Hat's youngest rider, said: "Well, who was this fellow? What'd he take Pete Cruze's place for?"

Izee grunted, "Shut up, Gippy," and followed Benbow out of the bunkhouse. Benbow called, "Gippy, come here," and waited until the kid's stringy shape appeared uneasily before him. "Ride into Two Dance, Gippy. You'll find Pete Cruze there. Tell him to come back."

"Whud he do?"

Izee repeated gently: "Shut up, Gippy."

Benbow went down the yard with Izee as far as the porch. Jack Dale sat in his chair, making no motion. Connie stood with her shoulders touching a post, her face showing vaguely to Benbow. Jack Dale's voice ran the silence with an iron distinctness.

"You framed something, but it leaked out. Is that it?"

"I arranged this with Arizona at Cheyenne four days ago. His real name was Tory and he was a detective for the Cattlemen's Association. Cruze knew his part, and played it well when I fired him. But there was a leak." He spoke in a dying, softening voice. Connie turned nearer him when she heard that tone, knowing the fury held beneath it. Gippy Collins pounded out of the yard toward Two Dance town; the shallow river sent its clucking echoes into this deep stillness. Benbow stirred his tall figure. He spoke again. "We're going to have some trouble, Jack."

"You can have it," said Old Jack Dale, "or you can avoid it."

"Trouble will hurt Hat."

"It's your choice, Jim. You're runnin this ranch. It's your say."

"Hat," said Benbow, "comes first. It always has."

"I built Hat out of trouble," Dale said. "But you can duck this trouble if that's your desire. I make no recommend."

"No," said Benbow. "I'm out to break, or be busted. But I can leave Hat clear of it."

"How?"

Benbow looked up at the girl. "When you marry Clay, Connie, he'll be the foreman here. I'm not desirous of turnin' a wrecked ranch over to him. When you marrying him?"

She said: "Why, Jim?"

And Jack Dale growled: "What's that got to do with it?"

"I can wait my time until he comes. I can hold off on this fight—if it ain't too long. But if it's to be a delayed affair then I'll have to quit and go after these fellows on my own hook."

"Quit?" said Dale in a resounding tone. "Who the hell is pickin' foremen for this ranch, you or me? You'll stay."

But Benbow's answer was softly stubborn. "Clay's my best friend, but there ain't room for two foremen here."

"Who said there'd be two foremen? He'll be Connie's husband, but you'll run Hat."

"Connie," said Benbow, "your dad ought to be a smarter man than that. Tell him what he doesn't see."

The silence ran on, Connie Dale not-speaking. Izee turned away because he knew he had no place here. Jack Dale pushed himself out of the rocker, his heavy body a painful burden to his joints. "I guess I see," he said.

Connie Dale descended the steps until her eyes were level with Jim Benbow's face. She touched his arm and her voice was softer with him than it had ever been. "I don't know when I'll be married, Jim. But you'll have to stay until then."

"Why?" asked Benbow. "Why?"

Jack Dale went to the house doorway, and paused there. He said: "When I ran Hat I never stepped around a fight. I'd like to see one more scrap before I die." Having said it, he went inside.

Connie said: "What are you afraid of, Jim?"

He swung away from her deliberately. But she was a strong presence at his side, like fragrance riding the night air, like melody coming over a great distance. Well, it was worse than that. Here stood Connie Dale to shake him badly with the hint of a womanliness so fresh and turbulent and strong. All across the flats the full shadows of night pulsed; the faint lights of Gay's store were winking out from the foothills and the near earth had a gray, lucent shine to it. He remembered the way Arizona's body hung over the saddle.

He said irritably: "What do you want to delay the marriage for?"

"I don't know, Jim," she told him, humbly. "I don't know."

"Nobody," he grunted, "seems to know anything."

She repeated: "What are you afraid of?"

He wheeled and reached for her, pulling her down the steps altogether until she fell against him. He had a tight grip on her arms and could feel the sudden tremor running through her body, through all its soft resilience. There was a little moment of passiveness; and then she was pushing against him. He let her go.

She said: "Is that what you're afraid of?"

He couldn't find the right answer. Wildness drifted with the night and the feel of it was queer to him, like the weightless, breathless air preceding the break of bad weather. Only it was worse than that, His thoughts couldn't reach ahead, but off there somewhere—in the farther space and in the future time—lay something that turned him spooky, sending through him a cold thread of actual fear.

He took her hand, holding it without pressure in his own big palm. "It's the end of good times, Connie. For all of us, I'd guess."

GEORGE GRAY was marrying off his only daughter and only child, and since he was a large-handed man in a neighborly land, all of Two Dance Valley collected at Block T this crisp morning to help him celebrate. Standing beside the keg of whisky set up on a platform, George Gray considered the valley men around him with a rather harassed glance. He couldn't, he told them frankly, consider himself in his right mind. Preparing for the ceremony had been just one damned thing after the other, and if he'd known it was to be like this, with the womenfolk crying all over the place and the house decorated up like Fourth of July and the work on the ranch gone plumb to the devil while his riders wore themselves gant running to town for things forgot at the last minute, he'd of put Eileen and Joe Gannon into a buggy and made a shotgun wedding of it long before now. Having said it, he tapped the keg for another drink and took it quick and straight. And said, dismally, "Your health, Joe."

They were all here, Jim Benbow, Izee, Clay Rand and Price Peters, Gray's own Block T crew, Gordon Howland who ran Crescent over on the edge of the badlands, Jubal Frick of Running M and Cash Gore, his foreman, the folks from Summit Ranch and from Gay's store, and Nelson McGinnis of the remote Diamond-and-a-Half up in the Yellow Hills. And the bridegroom, Joe Gannon, who stood uncomfortably and unsmilingly with the group. And a young kid who had ridden into the yard and made himself at home, though nobody knew him. The bishop, who had come from Cheyenne to perform the ceremony, was in the house, rehearsing with the women.

Everybody filled up at the whisky barrel to acknowledge George Gray's toast. Everybody but Joe Gannon. Gannon said, "Thanks, George," and looked around him with an air that wasn't quite easy. He was ten years older than Eileen, a rather somber man who ran his own spread over in the Yellows and had a reputation for a short temper.

Gordon Howland, George Gray's nearest neighbor for fifteen years, spoke up cheerfully. "You can sleep late tomorrow and rest your mind."

They all grinned at that, knowing how much worry Gray's half-wild daughter had caused him along the years. Clay Rand turned to wink at Benbow; and then Benbow saw Joe Gannon stare at Rand with a swift flash of anger. The crowd broke up, loitering around the tables spread in the yard for the wedding breakfast. The youthful stranger stood with the Block T crew, his gawky and immature face turning about in curiosity. Rand and Price Peters and Izee had come up to Benbow, to form the inevitable partnership. Benbow heard the kid speak in an insolent tone.

"I got to get a new horse. A posse ran hell out of me, clean across Utah."

Most of the men in the yard caught that and turned to look. Benbow observed the way the kid reacted to this interest, lifting his shoulders and slyly smiling.

Price Peters looked at Benbow. "Tough. He admits it."

"Fresh from mama," said Benbow. "Just tryin' to cut a figure."

"Bad place to announce his sins," murmured Price.

Mrs. Gray came out of the house and called, "George," and Gray walked away from the party. Clay Rand drove both hands into his pockets, restlessly clattering some silver change. "A wedding's a long time to wait for breakfast." Sudden Ben Drury, sheriff of the county, came, curving into the yard, a little man and a close-mouthed man with a clever manner. There was a group half-circled around one of the tables and going over that way, Benbow found a man from Gay's store seated opposite husky Ben Phillippse of the Block T outfit. They were trying out their strength, palms locked, elbows on the table. Ben Phillippse grinned and drove the other one's arm sidewise down to the table, and let it go. He said, "Well, anybody else?"

"Sure," called Izee, "I got a man for you; Sit down there, Jim."

"I'll have some," agreed Benbow and took his place opposite Ben Phillippse, locking his big palm into Ben's. "Say when."

"When," said Phillippse and threw power into his arm hugely. It lifted Benbow an inch up from the bench, but he kept his arms straight. Phillippse quit grinning at once and threw his right shoulder forward to get a better leverage. His lips stretched out from the effort and he began to throw a heavy breathing through his wide nostrils. Benbow said, "It ain't enough, son," and forced Phillippse' hand to the board.

Phillippse said in astonishment: "I never knowed you could do that, Jim," and promptly got up from the table.

Jack Dale spoke from the circle. "Hat feeds its men well. Fifty dollars to the fellow that can lick Jim."

"A go," said Clay Rand and sat down in Phillippse' place, matching his palm to Benbow's. Benbow said seriously, "I'd rather not, Clay," but Clay Rand shook his head and said, "Go," and threw his strength into that arm. A moment later he was standing half upright, his knuckles pinned to the table top by Benbow's sudden burst of strength, a swift, rash anger boiling into his bright blue eyes. Benbow let go and sat still and cool. Rand turned his hand around, staring at the fresh bruise across the knuckles; his cheeks were red as fire and all the humor was out of him.

"Kid," he said unevenly, "I hate to get licked."

"A sucker's remark," called Price Peters at once.

Rand wheeled away, not saying anything more. Benbow lifted his attention quietly to the rawboned shape of Cash Gore standing by. Gore's eyes were half closed in the manner of a man deeply considering a fresh, strange thought. He met Benbow's glance carefully and without a change of expression; yet behind that attitude of indifference Benbow saw a white flame burning its wicked light. Benbow said: "Interested, Cash?"

Gore lifted a hand, pressing it carefully across his mustache. He murmured in a dry tone, "I never do fool things, Benbow."

All at once the silence of the circle turned thick and a feeling of strain crept along it. Benbow got up from the table, hearing George Gray's voice summon them all to the house. Nobody else moved for a moment and Benbow, letting his eyes stray to either side, saw the cramped interest of all those faces, the thoughtful attention. They were like men waiting for something they had long expected to hear.

"I always said you were a clever man, Cash," agreed Benbow. Then his added phrase fell with an idleness that was more effective than a rifle shot. "And a careful one, too."

Gore's answer held that same dry rustic "That's right."

Jubal Frick came through the circle to touch Gore on the arm. "That's all, Cash."

Gore swung on the Running M owner, shaking the man's arm away and speaking to him sharply. "I'll make up my own mind, Jubal."

Jubal Frick spoke with a touch of apology. "I know, Cash, but—"

"Mind your business," said Cash Gore. . He was shaming the Running M owner before this crowd. Jack Dale stood up to his full height, outraged yet silent. Nelson McGinnis of Diamond-and-a-Half stared with an angry wonder. They were all waiting for Jubal to give this overweening foreman his just answer, and shock was a plain thing in the crowd when Jubal, without meeting any man's eye, turned quietly away.

"A good way," drawled Benbow, "as long as it works." He left it like that and swung toward the house. The valley men broke out of the semicircle as though released from frozen attitudes.

Price Peters walked in audible astonishment beside him. "You see that?" he grunted. "You see that?" But there was nothing more said, for they were all crowding into Block T's front room where Eileen and Joe Gannon were side by side before the bishop. Karen Sanderson, a big and blonde German girl, was playing the old-fashioned organ and some of the woman had already begun to weep quietly, instantly reducing every man to a wilted silence. When the music stopped Eileen and Joe knelt before the bishop who began to recite the wedding ceremony.

Clay Rand leaned near Benbow, ironically whispering. "Why do they cry—for happiness or for knowing what marriage is like?" But Benbow was indifferent to that talk, for he saw Connie standing tall and pale and near to being beautiful in the bridesmaid's place; and he saw her eyes turn and find Clay Rand and send something across the room that was sad and strange and lovely—and meant for Clay alone. Benbow dropped his head, listening to the last words of the bishop.

The organ started up again and at once everybody was talking. Price and Izee and Clay were bending their heads together. Price said: "Joe's a jealous son-of-a-gun," and winked. And at once the four of them walked toward Eileen in single file, Price leading.

Price said: "All brides get kissed," and took Eileen into his arms. Gannon stood darkly by, stabbing Price with his eyes; and afterwards Clay came up and caught Eileen. Everybody in the room had been laughing at this, but the laughter died out, for Eileen stared at Clay, suddenly white as paper. Her arms resisted him a little before he kissed her. He had quit smiling and Joe Gannon seized him and whirled him around, ablaze with that quick rage always so near his heart. Gannon said: "You've had your time at that, Rand. The time's gone by."

Clay grinned insolently at Gannon. "When I go to weddings, Joe, I always kiss the brides."

Izee and Benbow took their turns and went on. A plump redheaded, little girl at the doorway said to Izee, scornfully, "I thought you were a bashful man," and went out with him. Benbow suddenly found Connie Dale walking without comment beside him, across the yard to the tables. He turned away, but her hand was in his arm, stopping him, and when he looked at her he saw a hurt pride showing out and a clear call for his help. They sat down together at one of the tables. Eileen came out with Joe Gannon and the bishop and the Grays. They started for this table, and then Joe Gannon wheeled and went rapidly around Block T's low horse barn.

Connie said: "What is he doing?"

Joe Gannon came back, driving a buggy across the yard. He stopped and jumped out and held his arm for Eileen to rise by; and stepped up to the seat again. He wasn't smiling and he wasn't pleased. There had been talk going on and now it ceased and into this quiet he placed his talk with a grudging effort.

"I thank you and my wife thanks you. We'll be at the ranch for any of our friends. But if anybody comes up there to start this fool shivaree business they'll run into buckshot." Afterwards he turned the buggy about the yard and lashed the team into a trot that carried them, unbreakfasted, eastward along the valley.

"Why did she marry him?" breathed Connie.

George Gray pounded a knife into his plate to get the crowd's attention. "What we're here for is to eat breakfast. Hop to it." He sat down and let his body go idle, staring at the table in a strange, troubled way.

The plump redhead came up, holding Izee firmly by the arm. "Connie, did you see Izee kiss the bride? Wasn't it romantic?" Her round cheeks were pink and she was smiling at Izee, though the smile had an edge to it and her voice was remotely exasperated.

Izee said uncomfortably: "Well, it's a custom, ain't it?"

"If there's nobody else you want to kiss," said Mary Boring with a restrained wickedness, "sit down and I'll bring your breakfast."

Izee sat down, muttering. The crowd was at the table, with a good deal of talk running around. Clay Rand came up to stand a moment by Connie, his high-colored features ironically amused at all he saw. He said: "When we're married, honey, I'll let you eat before I haul you away in the buggy."

Connie said, "Thank you, Clay," and didn't look up. Benbow had finished. He rose and left them there, going on toward his horse. Price Peters and a few of the younger men made a circle around Karen Sanderson who stood tall and serene and striking among them. Benbow removed his hat and said, "How are yon, Karen?"

She gave him her hand and across the enigmatic composure of her features a glow of pleasure appeared. Her voice was even and touched by faint huskiness; she spoke carefully, the inflections of English being still difficult to her. "I'm glad to see you, Jim."

"Women," complained Price Peters, "are always glad to see him. He seems high on the eligible list. Why is that, Karen?"

Karen Sanderson showed Price a slanting, veiled glance. "I have heard you speak German."

"Yes," said Price. "Long ago when I was a gentleman and a scholar."

Karen Sanderson spoke a few quick words in her own tongue.

"I think," said Price, gently, "you're right."

"I hope so," put in Benbow.

Color ran quickly across the girl's cheeks. "You understand?"

"No. But whatever it is, I hope so," said Benbow, and moved away.

Karen Sanderson's azure-blue glance followed him half across the yard and then came back to Price, without expression.

Clay Rand walked up. He said, "Hello, Karen," and Price Peters' sharp senses felt coolness come between those two people plainly. It was that much of a change, Karen Sanderson looking at Rand with a distant pride, with a reserve and a faint shadow of contempt. She didn't speak. Rand let a brief laugh fall and swung away.

"And he is not," she murmured to Price.

Walking toward his horse, Benbow came by a knot of Block T hands in time to hear the strange kid speak up in a bragging voice: "I'm called the Travelin' Kid. Once down in Arizona I led a sheriff three hundred miles—"

Benbow stopped and caught this scene at a glance. The Block T men listened gravely, knowing a liar when they heard one. But Cash Gore kept himself a little aside from this group and observed the kid in a manner that was as sharp as the edge of a knife, as sharp and as predatory. He caught Benbow watching him and made a brief circle on his heels and walked away. Benbow went on to his pony, climbed up and trotted across the yard. He lifted his hat to Mrs. Gray, said, "See you next week, George," and left Block T behind him.

Price Peters meanwhile had drifted back toward the whisky keg. He stood there idly, displeased with his thoughts as was his habit; and then raised his glance from the ground to follow Clay Rand's retreat toward the horses standing three-footed by the Block T corral. Cash Gore was already over there, fiddling with a stirrup. For a moment Gore and Rand were side by side. Peters' mouth made a downpointed semicircle and his eyes narrowed on that scene. Neither man seemed aware of the other, yet Price thought he saw Gore's lips move just before Rand swung up to his saddle, adjusted his reins and rode after Benbow.

Price was so engrossed in his thoughts that the touch of another man's arm beside him jerked him straight. Looking around he found Izee; and for a moment they swapped glances. Izee cleared his throat, started to speak and changed his mind.

Price said: "Yeah."

BENBOW returned to the ranch from Block T and immediately afterwards struck across Two Dance Valley. At noon he had reached the ramparts of the Yellows and thereafter climbed that stiff edge of the hills and made his way through one and another of the corridors of a thick pine forest where silence lay like deep pools of water. At two o'clock he reached Rho Beam's chuck wagon and stopped for a cup of coffee with Old Veersdorp, the cook. Rho and the four Hat men who made up this outfit were somewhere back in the timber hazing up mavericks. Keeping Hat stock branded and located was a year-around proposition and this chuck wagon seldom got back to the home quarters.

"Tell Rho," said Benbow, "to kill a two-year-old and send a quarter to Frank Isabel. I'll be back here late tonight to get the other."

"Goin' tords Granite Canyon?"

"Maybe."

Old Veersdorp let his eyelids droop. "Rho went over that way last week and had a shot took at him."

Benbow went on at a leisured gait. Later reaching a naked dome on the edge of the Ramparts he climbed it afoot to have his look at the valley below, all aswirl with the powder-blue haze of Indian summer. Far across the land's yellow and chrome surfaces Hat's buildings lay as a faint blur. Dust rose from the hay wagons on up the river, and dust made its ribbonlike shape along the Two Dance-Running M road. Those two horsemen creating that bannered signal would be Cash Gore and Jubal Frick returning to their ranch. And across the valley another rider, seeming motionless because of the distance, ripped up his smoky trail. From this vantage point he could see the wide gap in the northeast where the valley ran between the prows of the Two Dance and the Yellow ranges toward the railroad at Mauvaise station.

He traveled on without hurry. Crispness lay under these trees, foretelling winter. Somewhere a shout sounded and ran on in a thinning echo. He passed a bunch of Hat stock in a little meadow. The trail, never very even, began to rise and dip to the more abrupt contours of this tangled land; and at five or thereabouts he reached the edge of Granite Canyon.

At the bottom of the canyon a small creek, laced whitely by the foam of its fast travel, dropped toward Running M out on the edge of the bench. In the other direction the high rock walls made a sweeping turn, carrying this natural highway deeply on into the heart of the rugged Yellows. A wagon trail marched crookedly beside the creek.

He put his horse back into the trees, himself taking position at the edge of the canyon. He had brought along his field glasses and from time to time he focused them on the outline of Running M's quarters just visible at the canyon's mouth, half a mile away. Men were moving around the yard, and around six o'clock a rider came into the canyon at a rapid gait. Lying flat on his belly, Benbow watched the man come forward and pass directly beneath. At this distance he had no trouble recognizing the husky, tublike shape of Indian Riley swaying with a characteristic looseness in the saddle. Once Riley's very dark and very round eyes lifted, his eyes sweeping the rim of the canyon; afterwards he rounded the upper bend and was out of sight.

Benbow went back to his horse and rode into the trees, taking a faint trail that paralleled the rim of the canyon. Going upward at a casual trot, he finally bent away from the canyon and came at last to a little meadow occupied by a gray log hut. It was sunset time, with long and hard flashes of light streaming above the timber and shadows banking themselves palely against the pine trunks. Stopped at the margin of the meadow Benbow called across it:

"Pete."

Pete Cruze was somewhere along the far edges of this meadow; his voice came back. "That you, Jim?" and afterwards he walked forward into the open patch and met the advancing Benbow.

Benbow said: "You campin' over there?"

"I like it better than in the cabin," Cruze said dryly.

"Trouble?"

"Shot at this mornin'. Before daylight—through the window."

Benbow nodded. "I thought it might come that way. Take up your belongings, kid, and join Rho Beam's chuck wagon."

"I can stick it out here," said Pete Cruze stubbornly. "To hell with Indian Riley's crowd."

"You'll join Rho's outfit," repeated Benbow, and then remained silent a little while, his long jaw crawling forward and settling his lips into a broad, thin crease.

He said softly, "You come with me, Pete," and waited while Pete Cruze went back into the timber for his horse. The two of them turned on up the trail.

The sky light faded and shadows were running thicker all through these pines, with a little wind springing up. The trail here struck straight into heavier timber, climbing steadily, and at the end of a half hour shot off to the left and led them to the canyon's rim again, dropping into it by sudden switchback turns. Below them directly, at a point where the canyon widened into the falling slopes of the Yellows, three gray houses sat elbow to elbow beside the creek.

Lamplight glimmered through the windows and men moved along the yard; and behind the houses somebody stood in a corral roping out horses. There was this much visibility left in the fading day. Benbow got down from his horse and drew his rifle from its boot. Seeing that, Pete Cruze followed suit. Both of them dropped flat at the rim's edge.

"It's always polite to return a callin' card," said Benbow. "We'll concentrate on the windows. Indian Riley might be pleased with the compliment." He let go then with his shot, tire dreaming stillness of the hills burst apart by the long and sharp clap of that explosion. One huge shout raced above the shot echo and all those men below turned to weaving shapes, racing to the rear of the houses. Pete Cruze had opened up, pleased with himself as he fired. Lights went out down there, one by one leaving the settlement presently in its half-darkness. Indian Riley's outfit, crouched out of sight, set up an answering fire. A bullet went whining past Benbow, high over his head. Benbow rolled on his side to refill the gun and raked the settlement with another calculated burst of firing; and stopped then. "That's enough, Pete."

They crawled back from the rim and got into their saddles, diving back down the trail. At the cabin he said, "Get your stuff and join Rho," and went on alone. When he reached the main trail he dropped immediately into the canyon's bottom and followed it toward the open plain, with darkness falling fully across the world. Running M's light winked in his face and Running M's dogs, hearing his approach, began to sound. He curled past Jubal Frick's corrals into the front yard and dismounted there. Somebody's high shape retreated around the far corner of the house; and two men rose almost in unison from Running M's porch chairs. Jubal Frick was there, but it was Cash Gore's voice that laid a toneless challenge on Benbow.

"Who's that?"

The front door stood wide, with lamps throwing a fresh, butter-yellow beam through it. When he stepped onto the porch he had to cross that light; and Cash Gore's voice came again, flatter than it had been before.

"You're draggin' your picket, Benbow."