RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

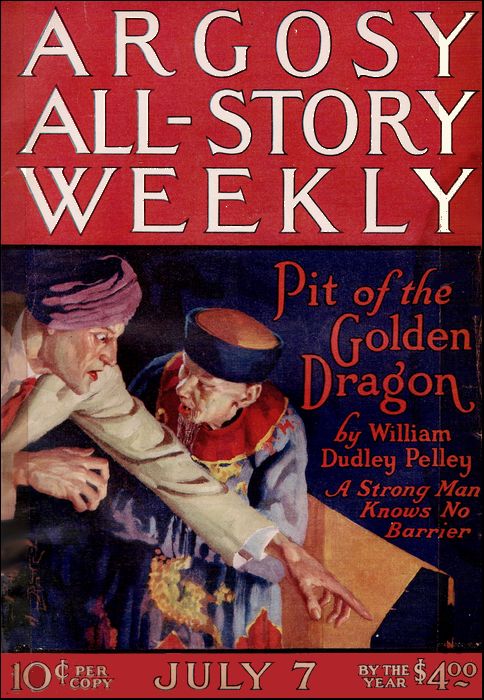

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 7 July 1923

with "The Acumen Of Martin Macveagh"

GEORGI GORZAS was an immigrant of many years past, from the little town of Poti on the east shore of the Black Sea. And he kept a small shop for the sale of rugs and Oriental bric-à-brac in a part of the city given over to others like himself of foreign birth.

Short and heavy set he was with a round poll, pink under a white stubble of close-cropped hair, scraggy eyebrows and a huge mustache he was always brushing aside when he ate or drank the light wines one could get, when first I knew him, and in which he was wont to indulge.

It was a rug that brought us together the first time. I saw it in his window and went inside to inspect it. Later we became friends.

Georgi got the rug out of the window, and we looked it over. I told him something of myself, and he reciprocated in kind. It was a matter of mutual interest. Physician though I am, rugs and rug lore are a hobby of mine, and Georgi saw it at once, of course. In the end I bought the one we had been discussing, and later formed the habit of dropping into the shop to examine his stock from time to time.

It was so I met Kuba, his daughter. Georgi told me she was like her mother. If so, his dead wife must have been a beautiful woman, indeed. Kuba was blond, with hair the color of amber honey, and a slender, lithesome figure, and lips like the flame of the hibiscus petal, in the warm whiteness of her face. And she was the apple of Georgi's eye.

Her father spoke broken English, but Kuba was American in all but birth, her parents having brought her to the land of their adoption as a child of five.

After such an introduction and the following association, there was nothing unusual, therefore, in Kuba's calling me on the telephone one afternoon and inviting me over to inspect a new and rare specimen of the weaver's art.

I called at the shop that evening and found a third party unexpectedly in their group—a young man as dark as Kuba was fair, with a great mass of nearly black hair that covered his head in a bushy shock.

Georgi introduced him as Kars Gorzas, the son of his brother. "From Tiflis he iss, toctor, und hees papa und mamma iss dead. So I wrote heem to come und lif wid hees oncle und hees cousin. Und see v'at he prought. Ged id, Kuba."

Kars grinned with a flash of strong white teeth, and Kuba, entering the shop back of which they lived, returned with a rug at sight of which I gasped. It was old, faded, mellowed like wine by age. But—it was an Eighur if I knew anything of such matters. And Georgi confirmed my judgment as Kuba unrolled it on the floor.

"See. toctor—a Tree of Heafen! Priceless—ab-so-lutely priceless!" His keen old eyes gleamed beneath their scraggy brows.

A Tree of Heaven it was, with the spreading branches, the varicolored cartouches, each with its contained cuneiform symbols on either side—a Tree of Heaven, and only Heaven knew where Georgrs nephew might have picked it up, or how he had brought it through the customs, or anything—except that there it was, with the stocky little old rug dealer gloating above it, and pointing to the first cartouche of faded pink.

"See, toctor—can you read id?"

I shook my head. I was no student of cuneiform. "Can you?" I returned.

He nodded.

"Man is a thistle blowing,

Woman a falling rose."

My interest quickened. The thing was Omaresque. It caught the fancy. Even the sound of its translation hinted at the origin of the rug—its age. Man a thistle.

The comparison was not inapt even in modern days. Human nature did not change—or not much. Woman a rose—in a garden—of Babylonia—a Babylonian maiden, hundreds and hundreds of years ago, perhaps. One thought of the hands that had woven the suggestion into the fading threads. Those hands were dust—but here was their handiwork. I glanced at Kuba. She, too, was a budded rose of womanhood. Her blue eyes met mine, and she colored faintly as though she understood.

Georgi shifted to the second cartouche, which was red.

"Who knows where the thistle blows

Death in the heart of the rose?"

His daughter caught her breath. "That's not a bit nice," she said.

Georgi smiled. "Bud id iss life, leetle Kuba," he told her softly. "Der rose dies—alvays. Only der perfume lifs—der soul. Id iss der vay of der vorld. Bud see, toctor." He pointed to the last cartouche of all, which was black, but not an even black—a thing of mottled effect as though some of the threads had turned rusty with the years. "Dis I cannod yed translate. Iss dese lines symbols or nod? V'at do vou t'ink?"

I bent over the thing, but I could not be certain. I shook my head again, balking the question, and glanced at Kars. "Where did you get it?" I asked.

He smiled, but made no other answer, and Georgi explained: "He don' spik English mooch. Bud—id comes from a reech man's house, he tells me. One can ged sooch t'ings cheap in Georgia, seence id vent Bolshevic. Und he knows I like sooch t'ings, so—ven I write heem to come life wid me und Kuba, he prings id. Und—I s'all not sell id. I am interest in dis plack cartouche."

I didn't blame him. He was pretty well fixed, and could afford to keep the Eighur, which was a thing to quicken a connoisseur's heart. So, after possibly some half hour of further discussion of the rug, I expressed my pleasure in having been asked to view it, and left.

And though in the press of work I did not see either Georgi or his daughter for some considerable time after that, I did not forget either them or the rug.

I thought of it instantly on the afternoon Kuba walked into my office during my consultation hours and took the patient's seat at the end of my desk. "Woman a falling rose—death in the heart of the rose." She was like that—her mouth a crimson petal, and death in her as in all of us, of course, but at that moment—glorious life as well.

Then, as we exchanged a mutual greeting, I noted a little lurking expression of what I thought anxiety in her eyes. And her first following words assured me I was right.

"Doctor, I wish you would drive over to see father, if you will."

"He's not well?" I questioned.

"He's not—exactly himself." She appeared to hesitate in the form of her answer. "I—I'm afraid it's his mind, and so is Kars. It's principally—that Eighur rug."

"The black cartouche?" I said, my interest mounting.

She nodded. "Yes. He's puzzled over it ever since Kars brought it—trying to make it out. But two weeks ago he hung it up on the wall and sat down in a chair in front of it, and he's—been there pretty much ever since. Kars and I have to coax him to bed and to his meals."

"He sleeps, though?" I questioned.

"Very little."

"And eats?"

"Hardly anything. He drinks a little wine. You know he has been accustomed to it all his life, and Mr. Sergovitch, a friend of Kars and a steward on an ocean liner, got a little for him."

I frowned. I didn't like what she said in the least. Fixed ideas, set determinations upon some object or subject are bad things at best, and especially so in men of Georgi's age. And then I looked Kuba full in the face.

"Just what did you mean by saying it was principally the Eighur?" I inquired.

Unexpectedly she colored and dropped her eyes. "I suppose I may as well tell you everything, doctor. Father doesn't like Serge. Kars brought him to the house shortly after you were there last, and—he came frequently after that. About a month ago—he—asked me to become—Mrs. Sergovitch." She broke off with a little self conscious laugh.

"He is a man of your own people?" I queried, taking advantage of the Slavic sound of the name to cover my surprise, at the information her somewhat stumbling explanation gave.

"Yes, doctor." She nodded without looking up.

"And your father does not approve?"

"No, doctor. I hardly know why, either. Serge had been very nice in every way he possibly could."

"And you—does he mean much to you?" I asked with the privilege of the physician, since ofttimes the doctor comes more closely into contact with the intimate details of his patients' lives than any one save the priest. "Do you love him, Kuba?"

"I don't know." She lifted her eyes frankly. "Honestly, doctor—I don't know. I like him well enough. He's really handsome, but—I guess I've never thought very much about marriage."

Once more she laughed in a catching fashion.

I smiled. If the girl herself was uncertain I judged that any impression Sergovitch may have made was not very deep.

"Well," I said, "when your time comes you won't think so much about it either. You'll think mainly of the man. Don't marry till you feel that way, little girl."

"Anyway, father absolutely forbade it," she returned and rose. "He became very much excited. That is why I felt I had best tell you about it. I told Serge I could not give him an answer then, and of course now—I wouldn't think of such a thing. You'll come over this afternoon?"

"In a little over an hour," I promised.

And I kept my word. I drove across to Georgi's shop, and Kars led me instantly into the living room where Georgi sat brooding over the rug.

He was in a chair before it as Kuba had described him, and he paid no least attention to our entrance until she spoke.

"Father, here is Dr. Payson."

"Huh?" He grunted then and turned his head slightly, peering at me from beneath his scraggy brows.

His appearance shocked me in spite of what Kuba had told me. There was more than a hint of failing mentality in the stare he bent upon me, and he seemed doubly aged since I had seen him, no more than a husk of his former self. Also there was an actually childish heat in the way he flared out:

"Inderruptions! My Gott, alvays inderruptions! Veil, Pay-son, vat do you vant?"

"Why," I said as casually as might be, "I just dropped in to see you. Miss Kuba thought you were not as well as you should be?"

"Vell?" he grumbled. "I'd pe vell enough eef I could read der piack cartouche. Somedimes id iss tedders, and somedimes nod."

I drew up a chair and sat down.

"Georgi," I said, "you're overdoing. You're tiring yourself out. If you'd take it easy—give yourself a little rest—"

"Rest?" he interrupted with a frown. "I can't rest, Pay-son. My head iss too ifull of ledders."

"Exactly. That's just it," I agreed; took out my thermometer and got it under his tongue.

He took it after a moment of hesitation, and held it, staring again at the rug. Abruptly he cried out, "Hah!" and bent forward, only to lean back, mumbling: "Nod yed—nod yed."

I caught the bit of glass and mercury as it fell from his lips.

"Georgi," I said sharply. He actually seemed to have forgotten my presence.

"Huh?" He glanced at me. "Oh, yes, Pay-son—yes, yes."

I made the best examination of him I could. He complained fretfully the whole time, but submitted. And I found little for my pains. His heart was a trifle quickened, the pulse too tense, and he was getting old.

In the end I prescribed a steeping powder to be administered that night, and advised that while Georgi slept the rug should be removed. After that everything was to be done to divert Georgi's mind from it. The reading of the black cartouche would seem to have grown to a monomania with him. I could see no other explanation of his conduct, and I told Kuba what I thought. She shuddered.

"I—hate the sight of the thing," she declared with an emphasis that mirrored her feeling as clearly as the words.

Kars was standing by the street door of the shop as I made my way out, apparently waiting for me.

"He iss mooch seeck?" he inquired, having apparently picked up a little English since I had met him first.

"Yes," I said. "I'm afraid he is."

"Eet ees hees head?"

"His mind—yes," I assented, and walked past him.

That night Georgi slept.

But the next day Kuba telephoned to say that he had grown well-nigh violent upon waking to find that the rug had been taken away, and that Kars and she had been unable to pacify him until they had put it back.

"Doctor, what are we to do?" she asked with a pitiful little quiver in her voice. "He's in there now, staring at that horrible black cartouche."

I said I would come over. And to my surprise, Georgi seemed to know me at once.

"Ha, Pay-son!" he exclaimed. "I'll tell you someding. Id iss in dere eef I could ged id out—eef id vould keep quiet. Id, viggles—comes oop und goes pack. But vun dime I fooled id. I pretended to pe asleep, und id stayed oop so long I read der first wort. Listen, Pay-son, dot first vort iss—Death."

"Oh, my God," I heard Kuba whisper under her breath, and even so there was tragedy in the sound of it, the jangling of overstressed nerves.

"See here, Georgi," I said, "what does it matter? How did you rest last night?"

"Hey?" He eyed me. "Vat does anyding matter, Pay-son? Death in der rose—death in eferyding vat iss alife."

He chuckled as though at some grizzly joke.

"Well, yes—of course," I assented. He put a hand on my arm. "I'll tell you someding more, Pay-son. Id iss alife. Id knows. But—I'll fool id. I'll vatch."

There was no longer any question but that the man was mildly mad.

"But," I said, "if that's the case, and you have to fool it, why not rest a little—go lie down, and catch it off its guard?"

He frowned at that, appeared to consider. "Trouble iss, I can't rest, Pay-son) My head iss—funny. I'd like to—rest—eef I could," he actually whimpered at last.

I gave it up, and Kuba followed me into the shop. And there I turned to her without waiting for her to speak.

"It's utterly hopeless unless we can get his mind off the rug or he should actually manage to read it, or fancy he had."

Kars.began speaking rapidly in his own tongue the instant I paused..

And Kuba translated: "He thinks possibly—we should have him taken to—some institution. But—I can't bear to think—of it except as a last resort. Do you think—?"

"I don't know," I told her. "Suppose you give him another powder to-night, and try to get him to eat. In the meantime I'll have a talk with a friend of mine and see what he can suggest."

"If you will, please, doctor," she agreed.

And that evening I drove over to Martin MacVeagh's for the purpose of keeping my word. I was actually distressed over Georgi and confess I wanted help.

MacVeagh was my friend, and, like myself, a physician, though one not engaged in practice in any general sense. Tall, slender, but well formed, with mobile features, spare fleshed, capable hands, hair of the color once denominated brick dust, and gray eyes, he was by no means handsome. But he was possessed of one of the most remarkably analytical minds I have ever known, a magnetic personality, and an at times almost feminine fineness of understanding that ever should the need arise quite overrode the calm deliberation and unswerving fidelity to purpose commonly attributed to the Scot.

Possessed also of independent means, he had taken a house shortly after leaving college, and fixed it up to suit himself, with living rooms on the ground floor and a series of laboratories above. There he devoted himself to what he chose to call "trail-blazing"—the scientific investigation of medical theories and problems—some of them those of others, many of them self-evolved.

In his whimsical denomination of his activities Martin literally told the truth. He spent his days, and sometimes his nights, in blazing trail for the everyday workers like myself to follow to better and more complete results. Few men not of scientific interest ever entered his doors. But I had the run of the place when I desired; and many were the hours I had spent there in listening to his discussions of theory and experimental demonstration, of which I never tired.

So when I found myself faced by Georgi's distressing condition I could think of no one better qualified to discuss the matter with me than my trail-blazing friend. And I drove over after dinner, having first telephoned to make sure I would find him alone.

Jukkins, his man—Martin was unmarried—showed me into a huge room with a fireplace and a massive flat-topped desk beside which my host was seated.

"Hello, Henry," he greeted my appearance. "What's on your mind?"

I told him the whole thing, and he lighted a cigarette and sat knocking the ashes onto a little tray from time to time.

"The man's off his head, of course. The human mind is a peculiar thing. Not unnaturally, though, his monomania has turned on a lifelong hobby," he said when I was done.

"I know," I said; " but what shocked me, Martin, was that when I saw him last he was interested in the rug, but as mentally right as we are."

"Assuming that we are," he returned, favoring me with a peculiar sardonic grin in which he at times indulged. "Is there anything in it—the black cartouche, I mean?"

"I don't know," I told him. "There are faded lines, as I've said. Georgi says they're alive—that they wiggle. But that is all bosh."

"Or eye strain," said Martin, discarding his cigarette. "But if there are cuneiform symbols in the other cartouches, we may assume that there are in the last, I think. I'd like to see it, and your patient."

"Now?" I suggested. It was more than I had hoped for.

"Well—there's no time like the present, is there?" He smiled and glanced at his watch.

As I recall, he spoke only twice after that on the drive over to Georgi's.

"Give him anything but that sleeping powder, Henry?"

I said I had not.

"Introduce me as a physician to his daughter."

I replied that I would, and followed his advice.

We went into the shop and found Kars, Kuba and a second man, whom she made known as Sergovitch as soon as I had presented Martin. I recognized the name and sized the fellow up. He was dark, well appearing, with a somewhat dapper air about him accentuated by a small Continental mustache.

"It was good of you to bring Dr. MacVeagh," he said as we shook hands. "We were just speaking of our poor friend here and"—he smiled in a deprecating fashion—"I was asking if there should not be a—how do you say?—"

"Consultation?" I supplied, rather surprised at his lack of the word since his English, even if accented a trifle, appeared excellent indeed.

"Yes," he accepted, nodding. "Nothing personal, doctor, I hope you'll understand. Kuba felt that you understood the situation. I presume there is nothing strange in her father's trouble taking the turn it has. He has been handling rugs for years."

"Nothing," said Martin shortly, joining the conversation for the first time. "Now if we might see the patient and—discuss him later."

"Of course, sir." Sergovitch stepped back with a slight twitching of the lips that showed he had not missed the almost painful abruptness of MacVeagh's words.

Kuba, too, glanced quickly at Martin as she turned to lead the way to where Georgi still sought to plumb the meaning of the black cartouche.

"Father," she said, and laid a hand on his shoulder, "here is Dr. Payson again with Dr. MacVeagh, his friend, he has brought to help you."

There was a veiled hope—a clutching at straws as it seemed to me m her voice. But Georgi chose to translate her announcement to the measure of his own desires.

"Hah, Pay-son! Now I haf almost god id. I told you id vas alife, didn't I, Pay-son? Und now I tell you someding else. Dere iss a soul in id—a leetle los' soul, died indo der warp und der woof. Und id's dryin' to ged oud. Id's peen dryin' for years und years. Ven I can read der meanin', dot vill sed id loose. Und der first vort is death—"

It was rather startling, rather weird—that thought of a lost soul caught, bound up, imprisoned in the fading threads—eerie, uncanny, what you like. I saw Kuba shudder. Her blue eyes turned again to Martin, tacitly asking his aid for another soul as I thought.

And then Martin was speaking. "Just so, Mr. Gorzas. It was recognized long ago that lost souls entered just such rugs—especially those that were very much faded, was it not?"

"Heh!" Georgi's gaze leaped to him. His old eyes flashed. "So—you know someding—you! Now you will helup me to helup dot leetle lost soul ged loose!" His fingers twitched in excitement. "Dis rug iss an Eighur—from Ninevah—Babylon—who knows? Kuba—a cless wine for Pay-son und his friend und me. Quick, Kuba. Hah!"

Ninevah, Babylon! And this was the twentieth century world. I heard the slender blond girl catch her breath in a gasp. She was palpably startled by Martin's words even if I was not. I knew the superstition he mentioned, and I knew, too, that he was possessed of the most amazing store of heterogeneous information from which he was always digging something up. But save for her sibilant inhalation she gave no sign as she left the room to return after a few moments with a bottle and three glasses on a tray.

But Martin, as he took his, looked into her eyes and smiled. "Thank you, Miss Gorzas. A soul is a wonderful thing. We should help it in any way we can, should we not?" he remarked.

"Yes—oh, yes, indeed," she faltered with an oddly searching expression, as though she were striving to read his full meaning. Then she turned to me with the tray.

Georgi, however, noticed nothing. He drained his wine at a gulp. I watched him. His hand shook and his head kept nodding like that of a senile paretic. He looked a man worn out, verging upon collapse.

Martin meanwhile sipped at his glass, appeared to roll its amber contents on his tongue. "A very wonderful wine, Mr. Gorzas," he declared. "May one ask where you obtained it?"

"Serge god id," Georgi said gruffly. "He iss in lof wid leetle Kuba, so—he prings her papa vine." His lips quivered, for an instant it was as though in a flash of sanity he smiled.

I glanced at Kuba and met her troubled blue eyes.

Then Martin set his glass aside and went closer to the Eighur as though to inspect it. And while he stood there, Sergovitch tapped on the door and called through that he was leaving.

Kuba stepped into the shop, and Martin turned to Georgi. "We haven't shaken hands yet, Mr. Gorzas," he said.

"Hey? No-o." Georgi put out a shaking wrist.

The two men gripped, and I saw Martin's sensitive finger creep up and find the radical pulse.

"And now about the translation," he veered back to the rug. "Man is a thistle blowing, woman a falling rose."

"So—dot iss right. Dot iss der first cartouche." I saw Georgi thought Martin had read it. I fancied likewise I saw MacVeagh's purpose and sat waiting—marking his every word and move.

"You have read them all?" he asked.

"All bud der last. Der first vort of det iss—"

"They are all about the rose and the thistle?"

"Yes." Georgi frowned, twitching his scraggy brows. m

"Then may we not assume that the rose and the thistle are memtioned in the black cartouche also?"

"And der first vort—" Georgi began again.

"Quite so," Martin once more cut him short, and glanced again at the Eighur. "The first word is death." He paused and then without warning intoned slowly:

"Death to the thistle and to the rose."

"Hah!" Georgi sprang to his feet as he cried out: "Hold on! Vait! Dot's id—dot's id. Death to der thistle und to der rose. Bud—ten thousand, thousand like dem oud of der dust in vich dey find—repose. Gott! See—J haf read id! At last I haf read id! Der soul is—loose!" He swayed drunkenly, sagged, sank together like an empty sack. Martin caught him before he touched the floor.

"Get Miss Gorzas," he prompted.

But Kuba had heard that breaking shriek of triumph. As I turned to comply with Martin's bidding, she ran in pale faced and wide eyed, with Kars at her heels.

"His bed, Miss Kuba." Martin spoke across the burden in his arms.

"In here." She kept her control and opened a door before him.

He bore Georgi through it.

"Undress him," he directed Kars. "Get a nurse, Henry."

I nodded and went into the shop to use the telephone. Sergovitch had disappeared and there was nobody about.

I got hold of a woman I frequently employed and gained her promise to come up at once.

Martin was sitting in the living room, staring at the rug, when I went back. He turned his glance toward me.

"Immediately," I said, and he rose and followed me into the bedroom.

Kars and Kuba had Georgi in bed. The girl's eyes questioned us as we entered.

"What happened?" she asked. "I heard him scream just before I ran in and—"

"He read the last cartouche," said Martin slowly. "Death to the thistle and to the rose. But—ten thousand, thousand like them out of the dust, in which they find repose."

"Ten thousand, thousand like them—out of the dust," she repeated, and glanced at the face of her father. "And now. Dr. MacVeagh?"

Martin surprised me. He went close to her, reached down and took both of her hands in his. "Miss Kuba," he said very gently, "would you wish him to—go on—if he is to be—as a little child?"

For a moment she made no answer, simply stood breathing deeply. Small doubt but that she understood. And then her mouth quivered. "Oh—no—no—I think not," she faltered. "Not if he should be—like that."

Martin's gray eyes lighted at the almost Spartan choice. "Then," he said, "I will tell you that in my estimation he will not live long or suffer much."

Silence, then, which Kars Gorzas broke, speaking swiftly with his eyes on his cousin's face.

She smiled wanly when he was done, and drew her hands from Martin's grasp. "He says—he will—take care of me—but, oh—if he only had never brought that dreadful rug to him!" She turned away to the bed and sank down on her knees beside it, and drew her father's hand to her lips with a sob.

Martin moved toward the door. I asked Kars to go into the shop and wait for my nurse, and followed him out.

When the woman came we gave her what instructions seemed best and left shortly after.

"Well?" I said when we were in my machine, "just what do you think?"

"I think," said Martin dryly, "that I overshot the mark. It was my intention to suggest a possible reading of that cartouche, let down the strain on the man's mind if I could. But—by a bit of infernal luck I hit too close to the truth, and he took the words off my lips. His excitement did the rest. The reaction was too great and—he broke."

"He'll die, of course?" I pressed for an opinion.

"Of course. You can't rebuild brain cells, Henry, and the man is nothing but skin and bones—burned out."

"And," I said," you think he really read it there at the last?"

"I think so" ^Martin assented. "His translation matched the rest. And when he read it, he knew it. It was his last conscious flash and it was—too much. He collapsed."

"Naturally," I agreed. "He's been eating next to nothing—keeping up on sheer determination and a little of that wine."

Martin made no immediate answer, and then: "The girl is the main reason for the latter, as one may suppose from what you tell me."

"Quite possibly," I said.

He chuckled, actually chuckled. He had a bizzare sort of humor at times. "And Georgi wasn't so muddled but he saw the point of Kuba's suitor currying favor by catering to her father's appetite, which being a steward, he could without much trouble. I suppose you consider that natural also, my friend?"

"I don't see anything unnatural about it at least," I declared. "These Europeans don't agree with us on prohibition. It would be natural enough for him to get it for Kuba's father under the conditions, I should think."

"Exactly," Martin gave me another of his diabolical grins. "That's the point."

"What is?" I demanded. Frankly I couldn't see any sense in the discussion of what Seregovitch had done.

"It's naturalness," he returned.

"See here," I exploded. Georgi had been my friend and all at once MacVeagh's manner piqued me, "do you or don't you know what you're talking about?"

"Not certainly," he said slowly. "It's hard to be certain of some things even when they're right under your nose. Do you know I sometimes think a great many things are missed, just because of the fact that their very naturalness, their triviality, causes them to be overlooked."

"What things?" I questioned, feeling my interest quicken in spite of myself.

"Oh, the solutions of problems—the deeper meaning of things we meet," he answered as though half to himself. "I suppose this will leave Gorzas's daughter pretty much alone in the world. She's a beautiful women, Henry. She has personality—a mind. And still waters run deep. She—feels this keenly, no matter how well she maintains her control, she's tnat sort; the sort a man would do well to win—and keep."

His words amazed me. Although women liked him he was in no sense a ladies' man. Now I found myself wondering if he were taking a personal interest in Kuba. She was beautiful enough to warrant it and I recalled how, when she had asked for his opinion, he had taken and held her hands. The thought shaped my answer.

"Still, she has Kars and Sergovitch, even if they are not actually engaged. Georgi's death will probably bring that about."

"Eh? Sergovitch?" he rejoined with another chuckle. "Oh, yes—the steward, mustn't forget Sergovitch or—ten thousand thousand like him, Henry. I see your point. Wonder if they'd sell that rug?" he broke off abruptly.

Actually I winced. Sometimes for all that I admired him immensely, MacVeagh both puzzled my understanding and got sadly on my nerves. One moment he had been discussing Kuba and the grief that had come upon her and the next he was casually voicing a cold blooded speculation on a point of barter and trade.

"I don't know," I said rather shortly as I stopped the car in front of his house. "But you might ask Kars."

"Thanks. Not a bad suggestion." He got out and grinned at me again. "Goodnight."

"Good-night," I grunted and drove off.

And this was the last I saw of him until two days after Georgi died. Then on the day of the funeral which I attended, Martin gave me another surprise. Unexpectedly he also was present and tacked onto me during the services both at the chapel and the grave, so that he was with me when Kuba came over with Sergovitch and thanked us with a wistful smile despite her tears.

Martin stood there until she had finished and then addressed the man at her side. "Lucky you could be here. You've obtained leave?"

Sergovitch twiched his brows, and shrugged. "I've given up my berth, sir. Miss Gorzas needs me right now, and we expect to be married shortly. I can always get another place."

"Doubtless. And I must be getting back to mine." Martin lifted his hat and walked off.

Kuba watched him with a puzzled expression in her eyes before she turned back to me. "Serge felt it would be best—since I have no one else—now," she reverted to the subject of her marriage, speaking slowly. "It will be just ourselves, and you, doctor if—you will come."

"I will," I said bridging over the situation as best I could. "I was your father's friend, and I would like to feel myself yours."

Then I went to where my machine was parked and found that MacVeagh had already driven away in his. I hardly knew why, but as I ran home I was conscious of a renewed feeling of annoyance with him rather hard to express in words.

Consequently, when he called me up the afternoon of the third day and asked me to come over that evening, I was glad. I had found there was generally some definite reason back of his at times peculiar actions, and to say the least his questioning of Sergovitch the day of the funeral had smacked to me of bad taste.

So I went over after dinner and found him seated beside his desk with a bottle of amber-colored fluid and a pile of crisp new bank notes before him, along with several test-tubes in a rack

"Hello," he said, shoving over a box of cigars. "Sit down and light up. When Kars gets here our party will be complete."

"Kars?" I repeated as I struck a match.

"Yes." He lighted a cigarette. "I took your advice about that Eighur.

"You're going to buy it?"

"Well," Martin blew out a stream of smoke. "That remains to be seen. Hello, there's the bell. He's punctual it seems."

Jukkins padded along the hall, and I made no response. Once more I was feeling a trifle piqued that Martin should have asked me over merely to witness his purchase of that infernal rug rather than for any other reason. Possibly two minutes passed and then Jukkins "ushered Kars Gorzas in.

"Good evening," Martin said without rising. "Have a cigar, Mr. Gorzas, and sit down. You've decided to sell me that Eighur?"

"Yes. I t'ink so." Kars helped himself to a smoke. I saw his eyes dart to the pile Of paper money "Tanks." He stepped back to a seat

"And the price?" Martin lifted the currency from the desk and riffled it like a pack of cards.

"Vat you t'ink?"

It struck me Kars was feeLing his way, forcing his customer to an offer.

Martin tossed the notes aside. His manner subtly altered. "I don't mind answering that since you ask me," be said, and suddenly he laughed. "You told your uncle it came from a rich man's house, and—what I think is—that you stole it. You stole it, didn't you, Kars? You're bolshevik at heart and it was part of the loot when Georgia was—sovietized?"

For a moment Gorzas stiffened. Then as Martin paused and sat regarding him with one of those devilish grins of his distorting his face, his lips parted slowly, and he smiled. On the instant it was as though the two of them understood each other and were sharing a joke between them. "Vell—vat of eet?" he returned.

Martin's grin faded. "Why, simply that there doesn't seem to be much chance of the original owner's showing up to claim it," he said slowly.

"He won't," Kars agreed grimly, so that I realized with a shock of disgust that the two of them were bargaining for a dead man's rug.

"Just so," Martin nodded. "But, before we go any further, suppose that I tell you a story—about a young man who lived in Georgia, and had an uncle who was a dealer in rugs in the United States. When the young man's father died, this uncle wrote him to come and make his home with him and his cousin, who was a very beautiful girl. And he came, and brought his uncle an Eighur rug as a present. Are you interested, Kars?"

I stiffened. Once more Martins manner had changed. To me it seemed that an actual note of menace had crept into his quiet voice. And Gorzas seemed to sense it, too, because his brows contracted, and he fidgeted in his chair before he said, somewhat gruffly: "Vat about eet?"

"I'm coming to that." Martin leaned back in his chair and dropped his hands into the pockets of his coat. "This young man's uncle was well to do—he had money. He had worked and saved. And the young man was bolshevik at heart. So, after a time he formed a plan to steal his uncle's money as he had stolen the rug he—Sit still! I can't miss you at this distance—Kars."

There was a phantasmagorialike element about it all—a continual bizarre shifting and change. One moment Gorzas was a self-admitted, unabashed thief, bargaining for the sale of his plunder—the next he was starting from his chair, snarling, with lips rolled back from his teeth. Then—then he was sinking back into it, crouching down before the flat, black weapon in MacVeagh's hand, shaken, gone sickly pale, with the furtive eyes of a cornered rat. And suddenly the atmosphere of the room had grown electric—charged with a threat as ominous as that of a rising storm.

Martin's voice came again like the murmur of its thunder as he went on: "He chose a peculiar means to effect his purpose. In the region of Trebizond, in Asia Minor, there grows a certain grape, and from that grape is made a wine. And that wine has a most devilish effect, in that while a glass or two may not hurt one, its continued use destroys the mind of the one who drinks it, so that in the end he becomes hopelessly insane."

I saw the whole diabolical thing at last, and I think I must have unknowingly uttered a sound, for Martin's eyes turned to me briefly and jerked back to the man in the chair beyond him—gripping its arms with tightly crooked fingers. Then he resumed:

"So this young man gave his uncle that wine. But, he had to get it first, and he did so through a steward on an ocean liner—one of his own people, and a man of like mind. And that man brought it to the young man's uncle as a friend. And the uncle, who had always been used to his wine before prohibition, was glad to get it, not knowing his nephew's intent. That went on until the uncle was practically mad, and his daughter called Dr. Payson to see him, and he in turn called me in. Then, because it is my business to know many things, and because after I arrived at Georgi Gorzas's house, he himself offered me a drink of this selfsame wine, I also stole something before I left. After he had become unconscious, and you and your cousin Kuba were undressing him, Kars, and Dr. Payson was telephoning for a nurse, I went back to the living room where it sat on a tray with three glasses, and stole that bottle of wine. And I brought it here to my house and analyzed it. And then I was sure, and everything else was plain. Here"—he gestured suddenly to the flask of amber fluid on the desk—"is the stuff with which, Kars, you murdered the man who had given you a home. And in these tubes—"

I leaped to my feet as Gorzas sprang. In a sweep of his arm he had hurled bottle and test tubes into a splintering wreck across the room and stood glaring at his accuser as he panted: "Proof eet? Proof eet, now, eef you can—you fool!"

"Sit down!" Martin's tone was deadly, and the mouth of the automatic was as black as a period to life itself. "I can prove it without any trouble. That bottle was only colored water—the stuff in the test tubes the same. Did you think I was fool enough really to place them where you could destroy them. The wine of Trebizond is safe where you cannot reach it, as well as the deadly brain destroying alkaloid which it contains."

The wine of Trebizond! Sinking back into my chair, I watched while Gorzas crept step by step backward to his own. He was cowed, now—had been tricked and he knew it. I saw a tremor shake him. He licked his lips with his tongue.

"And if that isn't enough," said Martin, "Serge Sergovitch was arrested this evening for smuggling wine into the country. Well, Kars?"

Gorzas shuddered. He clenched his hands. "He vas reech," he stammered thickly, and broke off, gasping. A little dew of perspiration came out and glistened in the light at the roots of his bushy black hair.

"And you told Kuba you would attend to everything," Martin went on. "Of course you meant to—you and Serge Sergovitch. It was the principal part of your plan. She was the price of his help, wasn't she, Kars?"

"He vanted her. Ve didn' mean to keel heem—only mak heem crazy," Gorzas mumbled.

Martin reached out with his automatic and struck a single blow with its muzzle upon the bell of a little bronze Chinese gong.

The door of the room was flung wide, and an inspector of police stepped through it.

MacVeagh gestured to the cringing thing in the chair. "Here is your man, inspector," he said. "He has practically confessed to the murder of his uncle, Georgi Gorzas. The charge against Sergovitch should be changed to accessory before the crime."

"You suspected it from the first," I said, after Kars had been led stumblingly from the room.

Martin nodded. "Yes. The man's condition suggested some drug, and I was certain after I had analyzed the wine. But I waited until after the funeral, because God knows that little girl had enough to stand up to, and then I struck. They deserved it of course, and I wasn't going to let her fall into their hands."

Well, it was like him—like the Martin MacVeagh—sensitive as a woman in his finer feelings, inflexible to duty, I had always known. And of course it made everything he had done quite plain.

"And you were right all the way through," I said, "even to Georgi's death leaving her all alone in the world."

MacVeagh's expression softened. He flung the little black gun on the desk and harked back to the Eighur in his answer: "Yes—poor little Georgia rose. But at least she is saved from that death in the heart she would have come to understand so well if their scheme had worked out as they planned."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.