RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

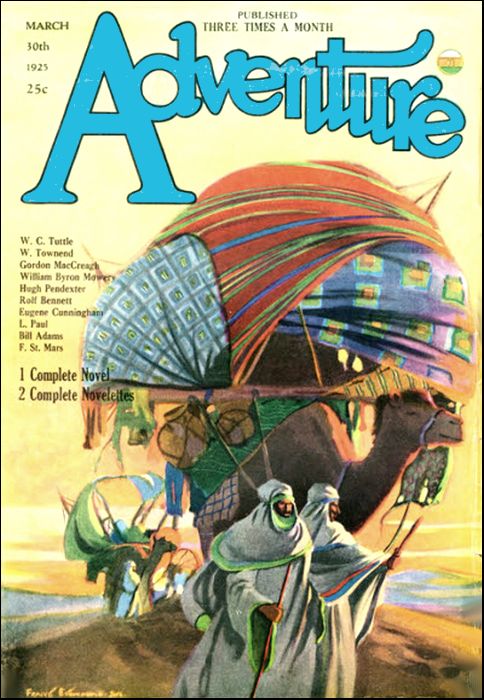

Adventure, 30 March 1925, with "Out of the Jungle"

THE senhor has been looking for me for two days? Bom, what information of the upper river is it that you want? For it is getting to be so that when men send strangers to look for Theophilo Da Costa it is always that they require information of the back country beyond the great rapids.

Not of the rivers, but of a man? Dom Perigoso? The Mister Dangerous? Hm! Why come to me, senhor? All Manaos City knows this man. Ask of the waiter who brings the little coffee that you have just ordered. Go out and ask the loungers along the water front. They will tell you that he is young and big of bone and that he knows the rivers and that he is Dom Perigoso; and, basta, that will be all that you will learn—unless they might dare to search back into the foul memories of their class and retail a savory scandal of his past. As for me, I am a man of the upper rivers and no retailer of biographies.

The senhor has a letter from my good friend Tio Romeiro? I may be permitted to see? Oho, this is different! The senhor is an Americano who requires a guide to take him into the jungles for the purpose of making a survey of the cedar wood, and he would know whether this Dom Perigoso is a fit person to entrust with his safety.

The senhor will be good enough to accept my apologies. I have dealt with many Americanos, and some of them have been whole men. And this Mister Dangerous, perhaps he, too, is an Americano—or maybe an Ingles or an Allemão—some one of the light haired peoples. I know no more than himself.

Yet who else knows more of the truth about him than I? And since this matter of going into the upper jungles is truly a matter of entrusting not only one's safety but one's whole life to the man who guides, and since my good friend Tio Romeiro is voucher for you, I will tell what I know, and you may then judge for yourself what manner of man is this guide.

WHO he is or what his name, I cannot tell. And he—if he ever knew—has long since forgotten. But of what moment is it how a man is called? It is what he is that we of the upper rivers take into account. And as often as not we call him some name that grows out of his character and forget the useless one that his fond parents gave.

So with Perigoso. Out of the jungle he came—was brought, rather, by his mother when he was—how do I know how old? A child of four or six, or maybe ten. I know nothing of how they look. She came down from somewhere above with the lad, a frail pale woman who was paying her penalty to the jungle, which is no place for a white woman to live; and she said that his father had already paid his penalty to the jungle, which is a place for few white men to live for too long.

Those were the days when rubber was the new king of Amazonas, and people acclaimed it as black gold; and men of all the nationalities came and went throughout and around Manaos and infested all the nearer rivers, and money flowed like in a mining camp; and no man knew nor cared who came or who went or whether with a woman or alone. Not like now, when the police take the full ten finger prints of all strangers and make them pay for the registration.

The city was but emerging in those days out of the jungle to its greatness that died so swiftly. And, like the jungle, it was no place for a woman to live—alone. So she died and left the boy motherless; and, as. the money-mad men of the period said with a careless laugh, truly fatherless also. So the good padres took him and brought him up and clothed and fed him and gave him an education better than that of most of the men who laughed so carelessly.

In which respect he was better off than many another who had both mother and father. But none the less such is an ill beginning for a lad. For in a wild city such as was Manaos of the rubber days there are always many who would cover the suspicion of their own birth by pointing the loud finger of scorn at an orphan brat.

So it followed that the boy in all his little comings and goings and wordy arguments was pushed aside and derided by the other boys, whose natural inclination at that age is that of young demons. When he would venture to hold his own in a discussion, always was the clinching argument the obscurity of his fatherhood. Though it is my belief that the woman spoke truth. For many men in those days went up into the nearer jungles to look for rubber; and knowing nothing of the jungles, took their wives— and the jungle ever took its steady toll.

Yet what matter whether she spoke truth or no? The handicap which the boy carried was no fair test. In those very years when his character and assurance should have been growing, he was ever thrust under and overridden with rough scorn. The senhor understands, no?

So he came to his youth. Big of bone and sandy of complexion. Strong enough to tear apart with his hands any of those frailer, darker tormentors of his. Yet shambling of gait and furtive of look; for the spirit which should have been his had been too much suppressed and had not kept pace with his growth.

And then, since youth is the time for troublesome emotions, he came, of course, to meet the girl, and hung with the attraction of opposites awkwardly round the skirts of a fiery little minx who lived in the Rua de Leon and queened it among the lads of the city. All the suppression and heartache of his boyhood he poured out beneath her window in the most mournful of the songs of our Portuguese tongue—than which no love lyrics of any people, even the senhor's own—are more distressing.

The very musicians whom he hired to play his accompaniments laughed as they thrummed their guitars and injected ribald impromptus of their own composition. And she, she giggled from behind the bars and played tricks upon him, such as compelling her duenna, who was a sleepy, silly woman of half Indian blood, to slip her fat hand through the hangings and drop the rose or the perfumed piece of rag or whatever it might be. But, carramba, it takes a long time to persuade a love sick youth that he is being laughed at.

Then came, of course, the rival. A flashy youth who had achieved some sort of leadership by reason of his assertiveness over the rest and who desired the girl doubtless for no other reason than to flaunt his superiority. Joaquim, was his name—Joaquim Something-or-other. I never knew the rest of it.

He told the lovesick one on one or two occasions in the presence of others to stay away from that particular window; to go down into the little streets behind the market where were half-breed maids and Zambos who would be glad to accept the attentions of a white man for no other reason than his color. And all his friends laughed loudly at the witticism. Yet so infatuated was the other, that in spite of his pusilanimity which held him from resenting the insult, he still sang his mournful dirges and paid his ridiculous court.

Till one day this Joaquim took opportunity in a public café when he was surrounded by his friends to call loudly to the other that he brought word from the Senhorita Whatever-her-name-was to say that she wanted no bastard of unknown parentage hanging about under her window of nights; and he laid hand, as he spoke, to the pretty little dagger with the imitation jeweled hilt that so many of our young bloods affected.

The senhor knows, of course, that this is fighting talk which no man may pass by.

But this wretched youth, alas for him, had so grown into the way of being browbeaten and thrust under that the spirit that should have flamed within him at the contumely was but a weak little spark, almost dead for lack of nurture; and he—well, he took backwater, as you Americanos say, and slunk shamefaced from the place.

A common enough tale, is it not, senhor? I tell it but to explain how this youth acquired his name. For after that he was known throughout the city as "Dom Periguiça." The senhor understands perhaps enough of the Portuguese?

No? The periguiça, then, is a feeble animal that hangs upside down from trees; and though it has three powerful great curved claws on each foot, it shrinks and moans and resents no sort of rough treatment. How do you call it in English? A sloth? Ah, yes. So, Sir Sloth, they named him in scorn; and the name was received with hilarity in all the cafés and promenades; and Dom Periguiça the unhappy youth was known as thenceforth.

We have a saying, "Hang an evil name upon your dog, and the dog will soon hang himself." So it was with this Dom Periguiça. When a man has been shamed beyond the limit of his self-respect what is there left to hold him from sinking out of sight?

Having once submitted to contumely the youth was lost. He was ashamed to be seen in the cafés where the ill-concealed jeers met him. He shrank even from meeting in the street those who had known him. He lost his little employment, whatever it was; and presently the haunts of the white folks saw him no more.

Such a condition, senhor, is like a quicksand. It grips one by the knees, and the sinking then is slow but sure. The Periguiça, having furnished his little entertainment, was soon forgotten, except for an occasional report during the next year or two that he had been seen slinking furtively along the back streets where lived the breeds and the negro Zambos who were willing to treat him as an equal on account of his color alone.

An ill condition for a white man to sink to. But, qué carramba, who can save a man from such but himself? And it is an inexorable law of quicksands that the deeper a man sinks and the more desperate his case, the less strength has he to save himself.

So presently even the occasional reports ceased; and those who remembered the merry jest when the talk swung backward in the cafés laughed carelessly and said that he had doubtless long ago fed himself to the caimans in the creeks below the new abattoir.

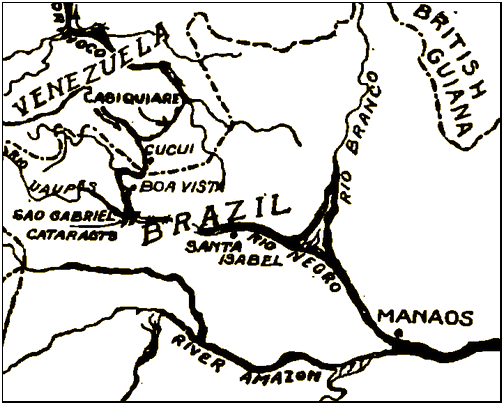

AND then, when the forgetfulness was complete, whom should I chance upon but this Dom Periguiça again. I was preparing for a long travel up the Rio Negro to the Casiquiare, the natural canal that connects the Negro with the Orinoco beyond the borders of Venezuela, and I had a small freight to carry as far as Santa Isabel for a Greek trader—who later swindled me out of the half of my payment.

No more than half a boat load it was. But finnicky little stuff. A few packages of knives and a half-dozen of ax heads and a case or two of salt and so forth; and they were to be delivered, a package here and a half a package there to this petty contractor and that little padrão of those who gathered Brazil nuts and assembled them at Santa Isabel. Stuff that required an endless tallying and accounting.

I, senhor, am a river man and no mathematician. So I let it be known that I could make use of a tally clerk for this little portion of my journey. And who should come to me and beg me almost with tears in his eyes to take him but this Periguiça.

"Celestes!" said I, "I thought you were dead." And then, remembering the tales about him of not so very long ago, "But consider; this journey in a small batelão up a river which is four miles wide is not without its little dangers."

This I said unthinkingly; and in the next instant I regretted it, for I had no desire to hurt unnecessarily the feelings of the youth who was, in all conscience, miserable enough. Lean he was and grown to a shambling manhood with overlarge hands and feet sticking forth from his inadequate clothing, and with the eyes of an animal that has been well beaten yet not enough to drive it to desperate bay. Yet I marveled that he had contrived at least to keep himself clean.

"This," said I to myself, "is a sign that he has not drowned the last of his self-respect in the liquor shops."

For it is my observation, senhor, that a white man, however low his sinking, retains at least his pride of race until his sensibilities have been dulled by drink. A man may well live among the lesser races by reason of adversity. It is when he falls to swilling with them that he is past redemption. So I said to the lad—

"What madness have you that you suddenly want to go up to the border of civilization?"

And he told me with a mournful admission that had its pathos:

"No. madness, Senhor Theophilo. But the need of remaining alive. Here I am known, and by my own people I am not wanted. Out of the jungle I came, and back to the jungle I go."

So I told him:

"You are a fool. The jungle is no place for a white man to live."

But he spread out his big hands and said—

"Neither is Manaos City—for such a white man as I."

So, qué diabo, it was after all no business of mine; and I, remembering his priestly education, knew that he would at least be an adept handler of accounts. So I said:

"Bom, very well, I will hire you for the tallying of all this mess of the Greek's and you shall come with me as far as Santa Isabel."

Whereat he was almost on the point of weeping again. But he was grateful. Sancta Ma'e, how the man was grateful for having been taken away from a life which must have been for him very close to the ultimate perdition! How carefully he kept tally in his priestly round hand of all the confusion of petty gear! And how he expanded as the days of boat travel went by in an atmosphere where he did not feel himself to be an object of scorn to all white men and of no more than toleration to black!

There came times when he even smiled.

Crouching in the prow of the batelão he would watch for hours the dense miles of river fringe swing by where no man lived, and the furtive look in his eyes would give place to an open glow. Not the light of exhilaration that you or I might show when the sun is hot and the river breeze is cool against the cheek; for the spirit in him was too crushed to take delight in the good things of the open places; but a somber glow as of a jaguar on a limb whose thoughts no man can guess.

And he would sniff with uplifted head like a jaguar at the down-river winds which brought with them no jeer or careless insult. It was then that he would smile, slowly and with nodding head. And then suddenly memory would come back to him; and with memory, the instinctive quick flash back over his shoulder with the hunted look to see if any one might be laughing at him.

I tell you, senhor, it was a difficult matter to travel with that unfortunate young man without having him feel that he was—well, how shall I say—not altogether an equal. And it is a terrible thing for a white man to feel that he must speak to another shrinkingly and with respect. Yet so he spoke to me, addressing me always as Senhor Theophilo; and always he asked questions about Santa Isabel; about the few nut gatherers there and how they lived. Truly I felt a pity for that man whose interest in white men and in their doings was dead.

Yet, carramba, what affair was it of mine? His life was his own to sink or to save.

In due time we came to Santa Isabel; and I concluded my little business there, and he made a faithful accounting of all the petty trash of the Greek's, and I summoned my crew of up-river Indians who waited for me there, and prepared to proceed on my long and arduous journey up to the Casiquiare.

And then, forsooth, arose another heartrending outcry. He came to me, again almost weeping, and begged me.

"Here I can not stay," he said. "That man, the half-breed who keeps the nut sheds, knows me, and he has called me by—by that name. And—and God pity me—I dare not kill him."

And he implored me to take him with me up river, away, anywhere where he could hide from the scorn that he could no longer bear. He would work for nothing, he said. He would be my slave. He would demand nothing other than his food. And he would be faithful and true and all the rest of it, without end.

But I, meu Deus, while I felt pity for him, I had a whole man's journey before me and a man's work. I could not saddle myself with one whom even my Indians would presently discover and deride.

Yet I did not know what to counsel him. The best I could think of was a feeble advice to go back and be brave and fight his own battle back to self-respect. Copy book maxims only, and useless at that. For in those days there was no regular steamer to Santa Isabel. Only an occasional launch in every four or six months; and, as he pointed out to me, no other trader who came to take away nuts would take him on his batelão with him—which, of course, was most lamentably true. So, after much consideration, I told him: "Look, this I will do for you. I will give you a dugout canoe and food such as you will need; and you must then go down river as far as you may care or dare. By keeping close to the shore there is little danger; and you can find some new rubber settlement where the men are perhaps strangers from some place other than Manaos. Take work with some seringuero, and take another name or something. Take also your courage in both hands; and then, if God is good, you may win back to your manhood."

Severe talk, perhaps, senhor. But what more could I do? His case was impossible. And I, carramba, I was no savior of men's souls. So I gave him the outfit I promised, and added some little trade goods beyond what I owed him—for indeed my heart bled for his misery—and I came away up river.

A BAD journey that was. Everything went wrong. At the great caxoeira of São Gabriel I lost a man. Right at the beginning of the rapid it was too. The rope by which we were hauling up against the fierce current slipped from the bitts, and before we could check it it had taken the man with a turn round his ankle, and in a flash, before we could do anything, he was gone. So we were compelled to make the rest of the haul with a short crew—which means something, I can tell you, when one is struggling for some five days to progress through forty miles of furious water.

Then at the mission, the last lone point of civilized habitation above the rapids, I was compelled to lose a week while the good padre stuffed me full of quinine. So angered was I at the mischance that I deliberately refused to make an offering at the shrine for my recovery—though I felt, indeed, that I owed a thanks for that I had not brought that poor devil of a Periguiça along with me.

"Sancta Ma'e!" thought I, "what a time we should have had with him."

I thought often of that unhappy young man's case thereafter as I progressed up the river, and I wondered how the outcome would be. For a white man who can no longer live among white men must do one of two things. He will go among the savages and will either, on account of his superior intelligence, become a king among them; or he will, on account of his inferior physical dexterity with insufficient tools, sink to a position of dependence upon the labor of such women as he may acquire.

The problem held interest enough to occupy my mind during the solitude of travel—till more trouble came, and, like others had done before, I forgot him.

At Boa Vista, which was no more than a name on the map, I found suddenly a new grass hut where no man had lived before; and in the hut a stubby fellow who told me that this was the Venezuelan border and I could go no farther. This to me, Theophilo Da Costa, who had spent my life traveling in those back countries where there were no borders.

But just in those days, you see, senhor, when rubber was beginning to be found in the upper rivers, much importance was suddenly being attached to boundaries which had been no more than imaginings in the minds of the map-makers but a year before.

Such a prohibition was, of course, no hindrance to me. But it was an annoyance and a delay; for that fool of a Venezolano was so inflated with the importance of his position away there beyond the borders of nowhere that for a period of some days he prated of his integrity before he would finally accept twenty milreis and let me pass.

Truly did that extortion gall me; and the temptation to obliterate that official and his petty outpost was great. But my little business which I was working on would require that I should return there later.

"'Cremento," said I to myself. "Twenty milreis was cheaper than a private war with Venezuela." So I bought him and passed on.

But what need to weary the senhor with a recital of the hardships of travel in that country? You will not be going that far, and you will find your own journey hard enough in all conscience. Suffice it that I remained in the Casiquiare some two months and then came down river again to meet with the greatest surprise of my life.

Not so far below Boa Vista was I when, passing by a village of the Kubbeos, a man hailed me from the shore. The water at that place was not particularly fast and there was a convenient eddy before the village. So I turned my batelão in to see what the man wanted—and, miravel, who should it be but the Periguiça!

"Sanctos!" I exclaimed. "How do you come here and why?"

He smiled slowly with his somber eyes.

"In your canoe which you gave me," he said simply. "Down, I could not go. For how should I know whom I might suddenly meet in some place who would publish me before all strangers? So I came on up."

The doggedness of this man to get away from everything that he had known was astounding.

"But, name of a saint!" I cried. "What do you propose to do with yourself then. Where are you aiming to go?"

To which he merely repeated his creed.

"Out of the jungle I came and back to the jungle I go."

"And how much farther do you think that you can go, madman," I asked him, "before you come again to men and cities? Not four days farther up is a Venezolano who wears a uniform and a sword and claims the half of the earth as his dominion."

But he was content.

"Then here I stay," he said with finality. "This is a good place and these Kubbeos are a friendly people."

"But—but—" I started to remonstrate.

But no more. What could I say? Did one ever hear the like before? Here was this youth whom I had left some three months journey down-river to return in quiet safety to some rubber camp; and now he sat in a Kubbeo village at just about the midmost point between civilizations. How did he get here? I asked him. By what miracle had he arrived thus far in a single dugout canoe; and had he not been afraid?

The question slipped from my tongue before I could check myself. But he, poor fellow, was accustomed to meeting that thought, and he felt in no wise hurt. He turned out his hands.

"Out of the jungle am I," said he. "Why should I fear the people of the jungle who are a kindly people?"

And what could I say? It was true. All those people of the upper Negro, Huitotos and the Baniwas and the Kubbeos, are a shy, simple folk; and in those days, before the rubber gatherers had penetrated to their country, they held no antagonism against the white men.

Today, the rubber gatherers have been, and after their few short years of exploitation, have gone; and nothing of their doing remains except an angry hostility among the Indians. But then it was different. I realized then that it was only white men with their many refinements of brutality that this man shrank from meeting.

An ill condition for a white man to be in, as I have said before. But one for which there was no remedy except in the man himself. So I left him. Only one request he made. He brought me the little money I had paid him for his tallying and said:

"Senhor Theophilo, there are some little things that I shall need for my use—" and he enumerated sundry tools and things— "and since your business will bring you back here in a few months, I would beg you—"

But I told him to go to the blue fiend with his money; and I came away, leaving him to the life which he had chosen with such persistence.

NOW what would the senhor think would be the outcome of such a condition of living? Would the youth rise by reason of his superior intelligence to be a king among those savages; or would he sink by reason of his civilized dependence upon a hundred and one artificial aids to life to a position of degradation among them? A question which I asked myself many a time as I traveled down-river; for truly the problem interested me, who for the sake of my own business made a study of Indians in their relation to white men.

So it was not without speculation that I came again after nearly a year to the Casiquiare, wondering how this youth who had withdrawn himself from his own people had progressed.

I found him —how shall I say? Improved? I do not know whether his condition would be called exactly a betterment. One improvement there was, and a marked one. The furtive shrinking expression had left his eyes and he walked now among men without looking eternally over his shoulder to see whether one might be pointing the finger of scorn at him. The habit of flinching had passed from him among these people who knew nothing of his story to jeer at.

So far, good. But for the rest—not so good. His little clothing had long since reached the stage of shreds and hung on him in strings; and he wore, in place of a hat which is the badge of the white man all the world over, a headband of plaited fiber to keep the hair out of his face, as did the Indians. Lean he was and stringy; but hard and brown and well fed. I looked to see whether with all this there had come in the place of flinching that assertiveness of the white man over a lesser race.

But so much of a miracle was perhaps too much to expect. A spirit which has been well crushed in its youth does not expand to man-sized proportions in the space of a year. Instead of assertiveness, therefore, I found a certain submission. How shall I explain it? Not humility; for self-respect was beginning to grow where he was at least the equal of other men. But submission to custom and convention; acceptance of tribal law. Out of the jungle he had come, as he said; and back to the jungle he had gone. The white man had gone Indian.

He was a maker of canoes, he told me; and as such he accepted with eager gratitude the few tools and things that I brought him. With their help, he said, he hoped to establish himself at last in his sphere of usefulness, and as such to hold a recognized place in the tribe.

For these are a community people, you must understand, senhor. They live in great community houses; and each man, as well as each woman, must do his share of labor for the common welfare. He had been set first to hunting, he said, to bring in meat with sundry others of the strong young men. Doubtless on account of his height and strength these primitive people had instinctively ascribed to him a prowess which entitled him to the most honorable occupation among them.

But the thing was, of course, absurd. Of what value is a white man with a bow and arrow or a blow gun? These things come with practise from youth up. Inept-ness was here his undoing. Catching fish, therefore, was the next stage down the line. Yet here again; can a white man suddenly learn the intricacies of making a fish trap out of split reeds or know the ways of fish? Well for him—or for any white man in the same circumstances—that they were a community people. Were he left to his own devices, he would have starved.

So he was demoted once again to a mere artizan grade; a digger-out of tree trunks to make canoes; where he discovered a certain facility of his hands and there stuck. A descent enough for a man of his muscles, be he white or brown. Carramba, the next stage would have been musical instruments, reed flutes; or the cultivation of mandioca with the women.

Yet at the canoes—thank heaven for the prestige of the race—he seemed to be established; and so remained at least a man; even though his word would carry no great weight in council as against that of others of the more honorable professions. And the worst of it was that he seemed to be content. As long as he was at least a man, the equal of other men, not flouted or jeered at, his broken spirit craved no more.

Aie-aie, my heart bled for him.

AND so I left him and went on up to the Casiquiare; and at Boa Vista , on the way I found that the Venezolano guard of the frontier had died and that apparently the word had not yet reached the far outside. At any rate, no provision had been made for his replacement.

So as a little matter of patriotic regard for my own country I took up his frontier mark and carried it a hundred miles farther up river with me and planted it again at Cucui, where the next man found it and accepted it as it was; and there the frontier stands to this day. So I take credit to myself such as few men may boast. That of having added a hundred miles to the borders of my country.

My business in the Casiquiare this time was swift; for the Indians knew now what I wanted and their supplies were ready. Plumes I was bringing out, for which I received a good price from a French buyer in Manaos; for those were the days before grandmotherly societies in the senhor's country as well as in sundry others had succeeded in prohibiting the importation of feathers.

There was more money in those days in feathers even than in rubber, and the outlay and risk were but a tenth. A half pound of salt or a small mirror I paid to the Indians for an ounce of the plumes, which I sold to that Frenchman for twenty-five milreis— and he, as I have heard, being a profiteer without conscience, sold them again to the makers of hats in Paris for three times that value.

But this I did not know then. I considered the market good; and for the rest, as with all trade, it was but a matter of organizing the supply. Since my Indians knew now that I would pay a high price for feathers, they had them waiting for me, and I made my collections without loss of time and returned to Manaos; and a period of some five months passed before I returned to fetch another cargo and to inspect my white man who had been well on the way to becoming an Indian of the third grade.

I found an Indian complete. A tall brown man with work-hardened muscles who wore a girdle of bark cloth and a head band and grass sandals and no more. Yet he stalked forward and greeted me as "Compadre," instead of, the Senhor Theophilo, as he had always insisted upon before.

"Oho," said I to myself. "This is an improvement this time. He has found his place among men, and with it he has found the spirit to look men in the face. A true son of the jungle. One of those few white men whom the jungle will take into its lap, and instead of killing him off-hand, will make a whole man of him."

And I shook him by the hand and congratulated him on his health, which was a marvel, and invited him to come and eat with me in my batelão, and we would talk over men and happenings. But he with one blow shattered the half of the illusion about improvement.

"Gladly will I come and sit and talk," said he. "But eat, I can not; for the ipagé has called for a general abstinence till sundown while he makes some magic or other."

"Sanctos!" I cried. "Have you come down to listening to the hocus-pocus of the witch doctors?"

He denied the charge swiftly. Yet with a certain shamefacedness that indicated more than he would admit; and he quoted lamely the proverb:

"'When one lives in the river one does not quarrel with the caiman.' Since all the village fasts, why should I flout the beliefs of these good people, my friends? And as for the ipagés, laugh not so scornfully, my friend; for they are not altogether charlatans. This I tell you, who live among them and have ample opportunity to observe."

Qué caralhos! This was the worst yet. Beliefs, he called them, you will notice, senhor; instead of superstitions. And I was convinced while he still spoke that he himself was more than half over the edge of believing. A dozen times I had seen the same thing; even among river men; yet never so marked as this.

Yet it is inevitable. A man can not live in close association with others, be they civilized or savage, without absorbing something of their minds as well as of their manners. And with him it was hereditary. Back to the jungle he had gone; and the jungle had taken him into its bosom as its own long lost son.

Health he had gained and strength, and a certain assurance to talk once more with a white man—or at all events with me, who was the only one he now ever saw. It was a matter of gratification to me that he had not sunk to a position of dependence in the tribe, as I had feared when I found him on the downward grade from the more honorable occupations.

But this submission to tribal superstitions was not good to see in a white man. Yet he showed me now another angle of his development, and I began to see hope for him again; and I was glad, for I had come to regard this youth almost as a protege- of mine.

This was the sign. Just as his civilized handicap of inexpertness had reduced him in status; so now his civilized advantage of intelligence began to assert itself. He brought me a half dozen of grass hammocks and said to me:

"Amigo Theophilo, I have here a thought for a small business. Look, these hammocks are of the finest. The fiber of the tucum grows here extraordinarily well, and these Indians twist it by hand under water and make such work as you see. Not many. Here one and there another in the back creeks as one chief dies and another is elected. But I have persuaded some of the skilled ones to make up this half dozen, promising them in return, machetes and ax heads. Now do you, Theophilo, take and sell them for me in Manaos. They are much better than those I have seen occasionally in the trade store of Araujo Companha, and should fetch a good price."

I smote him on the shoulder.

"Carramba," I said. "This is splendid. You are becoming a trader, no less. Assuredly will I sell them for you; and such hammocks should bring two hundred milreis apiece, which I will translate into goods for you—and my commission for the whole transaction will be one-third."

With which he was well content. And indeed I had made him a fair bargain; for the rule of the river is one-half.

"But look you," said I to him. "Take advice from one who knows this business of trade."

And I told him how he should make a flat price with his workers; an ax head or a few fish hooks or whatever it might be for each hammock; and the profit would then be legitimately his for further operations. And I warned him that he must pay scrupulously what he promised, and that he should then give a small present in addition, thereby retaining the good will of his workers. Much good advice out of my hard experience I gave him for nothing; and I told him also the final secret of all trade.

"Organize your labor, my son," I told him. "See to it that you can deliver a specified quantity at a specified time and of a specified quality. That is all. If you can do this you can be a contractor; for this hammock business offers a greater profit even than feathers.

"But organize above all your labor. Go swiftly up and down river and set the weavers to work to prepare a store of hammocks against my return. Promise a good payment and have no fear. Out of your profits on these six you will be able to pay for all the hammocks you are likely to get, since six months goes to the weaving of one such.

"After that, when the Indians learn that knives and machetes can indeed be acquired for hammocks you can establish yourself as hammock king; and then all possibilities are open to you; even the calling of a trader of the upper rivers; and you will then be a whole man among men."

As I spoke his somber eyes glittered, and his lips set in the expression of determination for which they were made; while he nodded slowly to himself and mused on the picture, looking, with that trick of his, for all the world like a jaguar on a tree limb. Till finally he said:

"Amigo, you offer great possibilities to me. I had thought to be an Indian and here to end my days among a simple and a kindly folk—as maybe I shall do still. But I shall do this thing that you tell me. And after the experiment has proven itself we shall see. While these Indians are my superiors in courage and natural skill, my superior intelligence of a white man may yet make an honorable place for me. We shall see."

AND so I took his hammocks and ]eft him. Full of high hopes was I for his regeneration; for the lad had shown himself to me to have good metal in him. Believe me, Senhor, a man bred in the cities can not root himself up from the life which he has known and travel suddenly in a dugout canoe to the farthest center of the jungles and there keep alive for a couple of years unless he has something. So I said to myself:

"Behold this soft metal of misfortune tempered by the crucible of hell in that tropic jungle and ready to emerge as a good blade."

And I took credit to myself for my share in this regeneration and determined that the next time I went to the good Padre Balzola for an absolution I would lay it before him to my good account.

But, qué diabo, I was over confident. A man whose spirit has been broken during those early years of the building period does not find it again, whole to his hand, so quickly.

In this wise the disillusionment came: I took the hammocks down to the store of Araujo in Manaos and told him that I had them on consignment for a friend of mine who lived up river.

And while the younger partner, the son, admired their texture, a sort of a trader fellow came in to purchase supplies and exchange gossip; for that great supply house is the meeting place for all river men. I knew the man slightly, a braggart fellow by the name of Joaquim who owned a couple of good boats and peddled goods among the down-river rubber men. He showed an unwarranted interest in these hammocks and inquired with an ill-veiled carelessness from where they had come. So I told him and added for good measure:

"Information which will not profit you at all, my friend; for that is in the upper rivers where you will never go."

But he smiled silkily, showing white teeth, and said to the younger Araujo:

"Ouve lhe. Listen to how these up-river men like to imagine always that nobody but themselves can travel their water."

And the Araujo, shrugging—

"Well, it must be admitted that it is the few who go."

Whereupon the fellow imparted a fierce upward twist to his mustache and laughed with loud bravado.

"And yet," he boasted, "I have been planning for a long time to make an up-river trip myself for the purpose of picking up a business opportunity or two which these rapid-runners have overlooked. In fact, I am even now outfitting for the upper Negro."

Whereupon it was my turn to laugh; and I said:

"Good, I will give you directions and channel markings of the rapids; and you will do me favor in return by carrying word to my friend that I am delayed somewhat by business and that I shall arrive shortly with his goods."

And I added also for the benefit of Araujo—

"Tell him also that the news is good; that I have sold his hammocks—though for no more than the half of their worth; a paltry two hundred and fifty milreis apiece."

And therewith I swaggered from the store and left them to scandalize me behind my back. And I laughed as I went; for it was no news to me about this fellow's up-river aspirations. I was well informed that he had taken that fool of a French buyer and had made him very drunk one night in the Café dos Estrangeiros and had extracted from him there information about the prices that he paid me for my egret plumes. I knew, too, that he had swiftly grasped the opportunity to take into his employ a man whom I had discharged on the occasion of my return previous to this one.

I had been sorry to lose the man; for he was a good man on the steering paddle and he knew the currents. But the fool had stolen a woman of the Huitotos and had kept her for a week while I was away in a small canoe up the Igarapé Pucanawa to make an arrangement with that creek tribe for otter skins. So, while I saved his life on that occasion, I got rid of him; for I was not going to become embroiled in any tribal vengeances on my future journeys through the Huitoto country.

With this man's knowledge—which I had taught him—I felt that this braggart man might well reach into the upper country. But I had no fear that any down-river man would steal my business from me. So I laughed at the man and insulted him with an easy mind.

But, saints protect us, how easily may a man who thinks himself secure overlook his vulnerable points! For my feather business I was safe enough. But this business of the hammocks from which I was hoping so much for my protégé—to say nothing of my own commission—carramba, that was another matter. Much as I might have advised the lad, it is, after all, experience that pulls the sure paddle.

Consider, senhor, what happened. This was told to me later by that woman stealer who was an eye witness to it all.

THE braggart boatman reached the upper country. Mischances and accidents did he meet with a-plenty. But the point is that he reached—thanks to my own trained man. Coming then to this Kubbeo village, he made a special halt to give himself the pleasure of telling my friend how he was on his way to fetch feathers from the Indians of the Casiquiare.

Credit must be given to the man for his boldness; for how was he to know that that friend would not take my part and resist him? But he had, it must be admitted, an aggressive assurance that carried him far in argument. So he stepped off at the little landing before the village and was very properly surprised at the apparent Indian who was pointed out to him as a white man who spoke good Portuguese, and who, upon recognizing a stranger, made no further advance. His surpise, not unnaturally in the circumstances, changed to the disdain which so many feel for one who has gone native. "Hey," he called. "Come here, 'Squaw Man.' I have a message for you from that arrogant fellow who calls himself your friend."

And then, as the lad came forward to hear my message, the disdain changed, with recognition, to loud scorn.

*"Oho," he crowed. "——! Look then at who is this friend of that Theophilo! The Periguiça, no less! Ho-ho, my old rival, the fatherless one! Canastos, what a meeting!"

Senhor, had T been there, I would have given the lad a machete and told him—

"Go, kill this man here and now."

And so would have saved his manhood for him. For with my encouragement and moral support the new spirit that was growing in him would have surely risen to the call; and, having wiped out the insult, would have established itself as a firm conviction of confidence for all time.

But alas and evil luck for the wretched youth. There was no one to encourage him; to stiffen his manhood. Alone he stood, and face to face with one who had mastered him of old.

As for me, louco qué foi, fool that I was. To me it had never occurred that this Joaquim might be the same blustering youth who had put him to shame in the matter of that little cat of the Rua de Leon. There are a thousand Joaquims, all the way from saints to peons. How should I have suspected such an evil coincidence? Though had an inkling of it come to me, I would never have subjected my young friend to so drastic and sudden a test. I would have delayed the fellow; would have scuttled his boat; would have kidnaped and held him by force, if necessary; till I might have gone up myself and at least have prepared the way.

But it was an ill fate that pursued the unfortunate from his birth. Much as he had grown, he was not yet ready to meet such a trial without friendly support. I believe even that had the rest of the Indians understood Portuguese and could have grasped the import of the insult, shame would have come to my young friend's aid and would have stiffened his courage to some show of resentment.

As it was, alas. The ascendancy of that other who had dominated him in the past was too strong for him. He did indeed—so the woman stealer told me—half stride forward for a moment with fire in his eyes.

But the utterly careless scorn of that Joaquim brought him to hesitation; and complete subjection was, of course, the next immediate step. He lowered his eyes, and his hands dropped weakly to his sides, and he shuffled away.

What was the natural outcome? In the upper rivers the old law holds, "He shall have who can take." This Joaquim found a nice little hammock business ready to his hand. My friend had been busy. He had traveled afar among all the river villages and had persuaded whole families to set to work on hammocks—on no more than his word, of course.

It was an indication of his rare ability to control Indians that he had persuaded them to labor on his mere promise of payment upon my return with his goods. But to hold those same Indians before he had furnished proof of his straight dealing—and against a rival who had actual goods wherewith to pay—would have been a miracle.

So this Joaquim circulated among the settlements and told the Indians that the other white man—meaning me—was dead; and that in my place came he. And in proof of it he brought, of course, the goods that had been promised; knives and beads and mirrors and all manner of shiny things.

What Indian could resist such? Had my unfortunate friend but once lived up to his bargain, there was no doubt that he could have held them for the future against all competitors, even as I felt secure about my feathers with those Casiquiare tribes. But as it was, they traded the hammocks leadily with Joaquim. And he, he came every evening to the little landing to display his stealings to the Periguiça and to spend a pleasant hour or so jeering at him and showing what a fool he was making of him before bis own Indians.

After which he would go across the river and make camp in a little glade on that shore. For this Joaquim was no real hero, and he felt a nervous suspicion that my friend might yet muster up courage enough to incite the Indians against him.

The whole circumstance was very unfortunate indeed and an ill trick of fate. I do not blame my unhappy friend. The trial was too sudden. It took him with the disadvantage of surpise, and it was too severe to face alone and unaided.

What, again, was the natural outcome? The laws hold in the upper jungles just as surely as in the cities; and it is my observation that when a man's spirit is sick with adversity—be his skin white or brown —his mood is ripe to listen to the spiritual doctors. As it is also my observation that the type of mind which feels the call to be a spirit doctor—be he a good padre of the mission or a painted savage ipagé—feels also the urge to control the minds of other people.

So there came to the unfortunate in his trouble the ipagé. A shrewd and a cunning controller of tribal destinies. And he made the customary talk of all the healers. In effect:

"Look," he said, "of yourself you are not strong enough to overcome the evil that has befallen you. That white man has made a fool out of you before all the people and has stolen away your goods. Appeal, therefore, to the Juruparí, whose servant I am; and by my magics which I will make I will drive away this man from here."

Senhor, to you this may sound fantastic talk to tell to a white man. But how do the spirit healers control except by understanding men's minds? Consider the case.

The man had left his own people, crushed and cast out by them. He had come among a kindly and a friendly folk and had lived isolated among them for two years. Some of their ideas he must have absorbed. Some of the undoubted magics of their witch doctors he must have observed. Further, he was in great trouble. What more natural than that he should say to the ipagé:

"Well, go ahead. For my part I can not lose by it; and if you can magic my enemy away from here you are a greater magician than I have given you credit for."

SO the ipagé chuckled to himself and set about preparing a great magic strong enough to fall upon a white man, who as a rule are not easily affected by witchcraft. For two days he beat upon a wooden drum, and for two nights he rattled upon a gourd rattle and howled; and on the third day he painted red circles of the genipa juice round his eyes and vested himself in all his vestments of skins and skulls and feathers, and sent for the white man.

"Look," he said to his near convert, "that place where your enemy now camps is not favorable to the Juruparí because the sun at midday falls full upon it. Do you, therefore, carry out faithfully the instructions that I now give you; and my magics will, within three more days, drive your enemy away from that place to another place where the sun does not fall; and the Juruparí will then first make him sick with a wasting sickness and will presently kill him."

Well, what would a man do in the circumstances who was already almost half believing something of the powers of the witch doctors? Skeptical he might be; but desperate he was also; and at the worst he could not lose any further. So he took the magics of the ipagé, which were fantastic enough. The entrails of a chicken and an unborn monkey and such clap-trap, all steeped in a foul-smelling broth of certain herbs.

"Listen," said the ipagé. "You will go by night and you will place these, half at the upper side of the camp of your enemy, where the Juruparí, traveling down with the stream, will see them and know them; and half at the lower side of the camp, where the Juruparí, traveling up with the wind, will see them and draw strength."

It is indicative of the power that the crafty old ipagé was beginning to exercise over the man that he took all these charms and went. In the third hour after midnight, when men sleep soundest, he took a dugout ubá and paddled across the river.

It is indicative, too, of the cunning woodcraft that he had learned during those years among the Indians that he was able to place the magic mess as directed; and indicative yet further of the courage that his desperation had given him that he dared to do it at all. For in that country of the poisoned blow-gun a sleeper does not wait to ask, "Quien es?" when he hears footsteps prowling round his camp at night. The rule of the upper rivers is not to come to a camp by night. Or, if one must, to carry a lantern and to shout aloud to herald one's coming.

But the Periguiça succeeded in planting his magics without mishap. Naked he went like any other Indian, so that there would be no dragging even of a loin cloth among the bushes; and as silently as the very best of the hunters of the tribe. At the north and the south of the little glade he placed the brew; and neither Joaquim nor his dull-headed down-river Indians heard sound or stir, though the upper deposit was within half a dozen meters of his tent. For this Joaquim, believe me or not, was one of those luxurious peddlers among the rubber camps who carried a tent to sleep in.

So the Periguiça returned and reported all that he had done, and the witch doctor said:

"Good, ipangu—" by which he meant, warrior of the tribe, as distinct from "kariwa," white man—"wait now for three days and see the magic of the Juruparí work its magic."

And ipangu, my unfortunate friend let himself be called; and he sat him down to wait, half skeptical yet half believing.

And on the third day, miravel, the miracle happened!

Watching eagerly from the farther shore, while the ipagé burned things that stank and muttered incantations and turned his eyes into his head in trance, he saw his enemy gather up his gear and strike his tent and load it all into his batelão and move down river to another glade where tall trees with a thick rubbery leaf threw a shade over the clearing.

It was then that the old ipagé chuckled and swelled his shriveled chest and said:

"Ho-ho, did I not tell you, ipangu? The third day comes and he goes, as I said it would be. Great is my magic and powerful is the Juruparí whom I serve. Wait yet three days—or maybe one or two more, for those white men are hard to bewitch—and you will see him sicken; and then in three times as many days the Juruparí will kill him, and you will be free from your enemy. Afterward you will pay me what I ask, when that other white man, your friend, comes up river again."

And it was then that the once white man became, ipangu, indeed in his own mind. Of all the white men he had ever known there was but one—myself—who did not persecute him and make a fool out of him; and of all the Indians there no one who did not befriend him. And now this witch doctor was delivering him from a persecution which even I, whom he had regarded as all-powerful in the upper rivers, had not been able to prevent.

What blame that he turned from his useless early teachings and trusted in the power of the old ipagé? Even though the third day came and his enemy still traveled among the Indians stealing his hammocks. For the ipagé said:

"Wait, ipangu. Give me yet a little time, for he is a white man. Let me make my strongest death magic."

And he shut himself up in his hut which was built like a jaguar trap, and planted his carved stick before the door to represent himself; which signified that no one might enter, and that all messages must be spoken to the stick; and from within he emitted groans and stinks and heavy smokes; and in the morning and in the evening he called once to his convert who waited in attendance:

"Does he walk abroad, Ipangu? Does he sicken?"

"Not yet, 0 Stick of a Great Wizard," answered the convert. "He still steals my goods and laughs his way among the people."

So the wizard groaned yet louder and blew upon the dread Juruparí horn for another day or two; and at last the watcher answered to the evening inquiry:

"Today, O Stick, he has not gone abroad. He has sat outside his tent and remained quiet."

And the wizard howled from within and emitted a pandemonium of ghost noises and cried:

"Wait! Wait but a little, ipangu! The Juruparí has put his mark upon him. I see it. I see the sickness that eats his breath. I see the death that sits in the trees waiting to leap upon him. Tomorrow, ipangu. Watch him well tomorrow."

And on the morrow, in reply to the evening inquiry, the watcher replied:

"0 Great Stick of the greatest of all Wizards, this day he has stayed within his tent all day; and his people, too, have taken the batelão out into the stream, and go ashore only to carry food to him."

So the ipagé shouted in praise of the Juruparí who was all-powerful and well disposed to his servant. And he made a fiesta of noises of triumph which he kept up unabated till the long, weird shrieks of the quahee bird announced that dusk had gone and night had come. Then he emerged at last from his long magic-making.

Having demonstrated to the final most exacting limit the power of his witchcraft, his ascendency over his convert was complete. He felt it was safe time now to begin to tell what was in his mind about the payment for all his labors.

"When the other white man, your friend, comes, ipangu," he said, "you shall tell him that you have urgent need of a cooking pot of the kind that does not break; and perhaps—if the man dies quickly—a little salt for a present."

Small payment enough for the astounding feat of magicking a man to death. The moderation of the fee, was, in fact, almost as astounding as the feat. Much more remarkable to my mind than the fact that this white man should have adopted, first the habits, and then the dress, and finally the beliefs of the Indians among whom he lived. Why should he not? All his upbringing and his environment had driven him in that direction. The last of his racial differences had been purged from him, and he was now a full Indian.

THEN I came. And it was time. To find a fine new batelão tied up near the opposite bank was no surpise to me; for news of this other white man's had met me at every turn of the river. But to find my unfortunate friend, of whom I had expected so much when I last came away, now a convert to black magic and under the thumb of a witch doctor was a shock.

Naked but for his bark cloth girdle and head band, and tanned brown and hard, he squatted before me like any other Indian. Except that, had he been an Indian with an Indian's courage and his own muscles, he would long ago have been a chief. Yet I saw hope for him still in the fact that he was sorely ashamed when he came to my boat and told me the tale of all these doings. Much more ashamed, indeed, of his cowardice before the Joaquim, who had made such a fool out of him, than of his subservience to the witch doctor. The latter he defended.

"But amigo Theophilo," he insisted, "I have seen. Here is the proof which you can see for yourself. As he promised, so has he done by his witchcraft. Had it been but the once, I would have said, perhaps it is a chance. But having driven the man from the one place by his magic, he is now just as surely killing him by his magic." In indignation I retorted. "Nom diabo, the fellow surely needs killing for the things which he has done to you. But a whole man, even though only an Indian, does his own killing."

To which his only reply was—

"Yes—but—"

And he lowered his eyes and shifted his big frame in discomfort before my scorn. Which I noted with great joy; for this was tremendous advance. There had been a time when he admitted his pusillanimity without shame, as a thing which he could not help; and it was only the scorn that people heaped upon him that hurt. Now he felt shame at last for that he had given reason for scorn.

Yet the law makes no exceptions. So there was a penalty as well as an advance. As his courage seemed to be growing in association with courageous men; so his senses, for lack of stimulus, seemed to be dulling to their own simple level where even a witch doctor could make a fool of him and twist him round to serve his needs. If I would save my friend, it was necessary to show his little mind to himself, as naked as his great body.

"Look," I said to him,"you have admitted that an Indian should have greater courage than you because he has been brought up in the midst of greater dangers. But as to the common sense—"

But he interrupted me to argue the matter.

"No," he said. "That used to be. Now I can go where the Indians go and do whatever the Indians do. I hold my own with them. It is only a matter of usage."

Whereupon I snapped back at him.

"Good. Make it, then, a matter of usage to hold your own with white men also."

To which his reply, while his face twisted with pain, was again—

"Yes—but—"

I laughed at him.

"So-ho," I said. "In courage you claim to be now at least the equal of an Indian—as also in intelligence."

But his spirit rebelled at that.

"No!" he cried swiftly. "By no means. I am a white man and have my white man's superior intelligence. Were I inferior to these Indians, excellent people though they are and the only ones who have never bescorned nor befooled me, I should be in poor case indeed."

Here was encouragement again. So I struck swiftly.

"So?" I said with derision. "You can do whatever the Indians do and you have, besides, your white man's superior intelligence, and these people have never befooled you? So indeed? Look you now, my friend. If you have but a little courage, as much as an Indian, to do the thing that I tell you to do, I will show you also how little sense you have, no more than an Indian. Answer me, then— Have you courage enough to go across the river to your enemy's camp while he is sick and bring me a branch of one of those trees which shade his tent?" And he said—

"That thing an Indian would not do; for the Juruparí is there. Yet I will do it."

And he went boldly, without hesitation, and paddled across in his ubá, handling the craft through the currents with great strokes as skilfully as any other naked Indian and twice as strongly. The downriver men from Joaquim's batelão jabbered at him; but he paid no attention to them. Instead, he stepped quietly ashore and strode past the tent without a word and cut a low branch with his machete. Then as swiftly and surely as he had gone, he came back and gave the branch to me.

"Good," I said to him. "In bodily capabilities I see you have grown indeed. But now let me show you how small your mind has become."

And I crushed some of the thick gummy leaves of that tree with my machete blade against the split palm deck of my batelão and gave them to him to smell.

"Smell hard," I said to him. "And tell me how you feel."

He did so, wondering; and—

"Pah!" he spat. "Sick at the stomach they make me feel and heavy in the head."

"Good," I laughed. "Now listen to me, white man of the superior intelligence. That crafty old witch doctor has two hundred times as much intelligence as you; for he has twisted you round his little finger like a fool. By witchcraft he said he would drive your enemy from that first camp; and he gave you guts and clap-traps which you must place in the sun to draw his magics with? Fool.

"Any one of the Indians, your friends, who are not so foolish, could have told you that the juice of the inga-shipo rots things quickly and draws, not magic, but the borua flies that sting and lay their eggs in the flesh of a man's back or in his leg."

At that he opened his eyes and gasped, and the hot blood rose to his neck. But he muttered:

"Well, and if so, that does not explain away the magic of making a man sick in another place half a mile from there."

So I laughed again loudly; and:

"Double fool," I derided him. "Look across at that bank over there as far as you can see. What other open place is there where a man might pitch his tent except that one which is shaded by those trees? Trees in which the Juruparí might sit and work his magic. Ho-ho, simple one. Any Indian except a down-river Indian could have told you that these were Juruparí trees indeed by name as well as by evil effect. But, being Indians as simple as yourself, they would ascribe the evil to the power of the Juruparí.

"Yet any white man who knows the upper rivers—as well as any witch doctor who is as clever as a white man—could tell you that a man sleeping under those trees at night, when all trees shed their vapors, would presently suffer from heaviness of the head and listlessness which would keep him sick abed. That it would ever kill the man, I do not believe. Yet I know from my own experience before I learned the ways of the river that—ho ho!—that he must have the very ——'s own headache.

"Now, what do you say to all that magic, you of the superior intelligence? Let me tell you, ipangu, that even now your witch doctor, as well as all his lesser assistants, are laughing at you. Tell me now whether they have ever made a fool out of you?"

And this time he had no answer to give me at all. He sat very still and silent, except that his great fist opened and closed repeatedly on his knee so that the knuckles showed white under the brown tan, and his eyes glowed somber and angry into the distance of the otner shore.

AND so I judged it best to leave him. I stepped ashore and went visiting in the village. I took a small present to the chief and chewed through the ipadú ceremony with him, and laughing, told him that his ipagé was a very great scoundrel. But the chief clapped his hand over his mouth so that such sacrilege might not enter his body and mumbled through his fingers that, no indeed, the ipagé was a very great wizard. And I laughed again and said:

"That word I take back, O Chief. I was wrong. He is a very clever and a cunning necromancer, and you may tell him that the white man compliments him."

With that the talk turned to tales of the old man's past prowess, each more wonderful than the last; and from that, to the inevitable discussion of the weather and the lishing and the mandioca crop and the hunting; and so on, far into the night.

When I returned to my batelão my friend still sat there, motionless almost as I had left him. He rose stiffly at my coming and said:

"Amigo, with your permission I will sling me a hammock in your boat. I do not wish to return tonight among the Indians."

So I humored him and worried him with no foolish questions. It was enough for me to see that he had thought much. With but few words between us I went to sleep. And in the morning I was awakened by the soft bump of an ubá against the side of my boat. My friend, with stern face and somber look, was preparing to get into it.

"What are you proposing to do?" I asked him.

And he said.

"The whole of what I am going to do I do not know yet. But watch me, my good friend and guide, and tell me if I do well."

And with that he paddled swiftly across the river. Straight to the batelão he went and climbed on board. From where I sat I could hear the sound of his angry voice raised, giving orders, and the answering jabber of those down-river Indians. Then presently without more ado I saw him give a shove with his great arm to the loudest talker so that the man fell into the water. Two others he beat toward the rope that tied the boat to its anchor stone; and the others without further argument took up their paddles.

To the bank I saw the boat go, and heard more angry orders. And then the crew all piled ashore; and while some carried their sick master to the boat, the others struck the tent and collected the gear; and then the boat came back across river and tied up alongside of mine. My friend was still silent and stern.

"What now?" I asked him.

And he replied with another question.

"Was it well?"

"Yes," I told him. "It was well done. But those were only Indians, and downriver Indians at that. What of the man?"

And he answered, troubled.

"I do not know. But do me the favor, amigo. Nurse me this man well. Till then I keep away from here. After then—I do not know. I must think. Do you advise me what to do; and send me word when he is well."

So I told him that assuredly I would attend to the man. That it would not be a matter of more than a couple of days or so. A good physic and an aspirina and clean air were all that was needed to put him on his feet. And he thanked me and went away from there with his head bowed on his chest and with long strides that trampled everything, unseeing, underfoot.

I knew that a mighty battle was about to take place between his fears and his manhood; and I did not envy him that fight. But it was his own to win or lose. I could not help him, nor any other man.

In three days I sent him word to say that Joaquim was as well and as braggart as ever, and he should come and make his stand, now or never. But I gave him no advice as to what he should do. Better, I thought, that he should make his own decisions and stand on his own feet.

He came in answer to the summons, swiftly. Which was a good sign; for I had feared hesitation. But it was evident in his demeanor that he had fought his battle and had made his decision, whatever it might be; and that, what was more, he had steeled himself to carry it out.

ON the deck of my boat we were sitting; and he climbed on board and squatted before us, naked as he was, and saying no word, his expression more than ever that of an angry jungle cat's. This should have been a warning to Joaquim. Anybody but a fool should have seen that this was a change indeed from the periguica whom he had known. But Joaquim was always a fool blinded by the folly of his own conceit. His greeting was one of braggart hilarity.

"Ohe, my good Periguiça," he chuckled. "I find I have to thank you for the small service of bringing me away from that place of stinks. Who would ever have thought of such a thing?"

To which my friend replied, speaking only to me—

"I have beaten the witch doctor."

My heart leaped within me at the thought and all that it meant. But I said only:

"Tcha-tcha, that was not well done, amigo. An up-river man must by all means keep friends with the witch doctors."

And Joaquim added, fatuous still in his folly:

"What? The Periguiça has beaten a man? Que maravel! Ho, ho, what will happen next? Truly, my good Periguiça, you improve in the jungles."

Then at last the Periguiça spoke to him, deeply in his belly, growling without moving.

"Do not use that name again."

That was all. The surpise of such a brusk order from such a source was sufficient almost to throw the Joaquim off the bale of print goods upon which he sat. But after a gasp or two and a stutter of amazement his anger came to him.

"Qué caralhos, fellow," he snarled. "You speak to me like that and I rip your liver out."

And he made the sign with his hand which among us means the ultimate insult.

My friend's reply was as sudden as the jungle cat's. He shot a great paw out and gripped the insulting hand as it made its circle in the air. Without any word he just applied pressure and crushed it till Joaquim screamed with surpise and pain and snatched with his free hand for the knife in his sash belt.

The other, still squatting on his haunches, and without effort, twisted the arm that he held till the elbow became stiff; and, using this as a lever, turned and thrust Joaquim off from his bale so that he rolled on the deck. There he held him at his mercy.

Then at last came to Joaquim the realization of the man's strength. And the rage which had leaped into his eyes at the insult gave place to wonder, and the wonder to fear. As well it might be. For, carramba, that naked figure squatting there with the sun on his bronze muscles showed power and a fierce suppressed anger. A very coldly dangerous man he looked to be.

For Joaquim, of course, that was enough. These braggarts are never great doers. He whimpered something about his hurt; and as for me, I didn't blame him; for the sudden realization had come to him that this man whom he had so tormented and wronged could lift him up and break him in two.

As the whimper rose to a squeal, the other pushed him from him with the stiff arm; and Joaquim rolled over and over and was then wise enough to lie where he arrived on the deck. My friend turned his face toward me, stern and without elation.

"Was it well done, my friend?" he asked.

I fell upon him and embraced him.

"Amigo mio!" I cried. "It was well and a hundred times well done. Now at last you have shown yourself a white man able to hold your own against a white man. Let it become a matter of usage."

And I embraced him again in the fullness of my heart.

But he withdrew himself from my embrace, cold and stern as ever.

"Yes," he said. "I am a white man. I have thought much with myself, and I have seen much within myself. A white man am I of whole white parents. Not with the Indians will I live, but with white men. Tell me then, my friend and adviser, what must I now do?"

But I answered him quickly.

"Nay, my friend. You are a white man of the light haired peoples. Make up your own decisions as a whole white man should."

So he thought a while—just a little. And then he announced his findings.

"This, then, is my decision." He turned to Joaquim who still sat upon the deck rubbing his elbow and weeping with useless rage. "You Joaquim—For all the things that you have done to me all my life and yours; and for all the harm you have done me among my people here; and for all my hammocks which you have stolen—for all these things I should kill you with my two hands.

"But I am not accustomed to killing—as yet. So all that I do is to take back my hammocks which are rightfully my business built up by me. And in return for your life which I do not take, I confiscate only your boat, which I need to carry on my business."

And he turned to me to ask once more:

"Is it fair? Is it well done, my friend?"

"A hundred times fair," I told him readily. "By the rule of the river a man who steals the business of an up-river trader forfeits his life. You do well by him."

"Yes," he said with conviction. "I am an up-river trader. My business is to sell the hammocks of my Indians to the shops in Manaos. I return down river with you, amigo Theophilo, in my own boat—if you will lend me some white man's clothes."

But at that Joaquim raised a howl on the deck and cried out that he would die up there among the Indians, and, Madre Deus, we could not leave him there to die. But my friend told him fiercely to shut up and added:

"This I will do for you. I will give you a dugout canoe; a good one, made by myself when I was an Indian; big enough for you and your crew of six men. And I will give you food from my boat such as you may need for your journey down river. It is enough. I, whom you used to call by that name which you will never use again, came up river in a canoe big enough for one man, without food and without a crew. Go, swiftly, and tell them that I am coming."

SO that was the end of that matter. What more is there to tell? We went together, my friend and I, to collect my feathers; and on the journey up I showed him all that I knew about the management of a batelão, and helped him to train his crew which he picked from among his people. And then we journeyed down river again, he with a more profitable cargo than I.

Without event of any sort we traveled down river back to civilization. My friend, silent and stern as ever, thinking long thoughts as he sat at the steering paddle of his boat and looking at nothing through lus morose eyes. I, wondering how would transpire the first meetings with other men who might not be so easily cowed as that braggart Joaquim. For among the rubber gatherers were men whom even an up-river man might respect without shame to himself.

But my fears were needless. Out of the jungle had come health and strength and consequent confidence to my big young friend. We arrived in due course at the first of the rubber settlements; and there a man known to both of us of old came alongside.

"Hola, Theophilo," he called. "Como vae?"

And he climbed by his ill fate onto my friend's boat, thinking it to be one of mine. There, after the first gape of astonishment, came recognition and the amusement which he thought was his right.

"Mira então!" he cried. "Look, then, whom we meet! Dom Periguiça of all people, whom we thought to be dead. He-he, where did you pick him up, Theophilo?"

The man was something of a fool too; else surely would that somber face with the jungle cat eyes have been a warning. But he laughed lightly and paid no further attention to it, turning to call me again. But as he turned, my friend made a long stride and gripped the man by the shoulder.

Astonished, he tried to twist himself round to see what this amazing thing might be, and wrenched to free his shoulder, snarling with rage:

"Nails of the —! Let me go, you crazy Periguiça, before I kill you."

But that one great arm was as strong as the whole of the man's body. With one move my friend twisted his hip under the man's belly and threw him in a single heave clear ten feet with arms and legs flying into the river. Then as he came up spluttering and mouthing threats of death, the Periguiça who used to be told him coldly:

"You mispronounced, my friend. My name is Perigoso."

And, caramba, Perigoso he looked, standing there with his feet wide apart and his big shoulders hunched forward, the chest showing through the rent where my thin coat had ripped with the effort, and his face dark and unsmiling with the light of the jungle cat in his angry eyes. A dangerous man indeed.

So that the rubber man, as he swam and looked, changed his mind; and muttering, "Valgame Deus," he climbed into his own canoe and paddled swiftly ashore without further offense.

That story spread, of course; as did other similar ones. For there were many such lessons to be dealt out and many hard men to be disillusioned. How many rash would-be bravos my friend threw into the river I never knew. But the time was surprisingly short before men forgot that other name and, Dom Perigoso—the dangerous one—he was called in all the water fronts.

So there is the tale, senhor. What manner of man he went into the jungle and what manner of whole man he came out, I have told you. Judge, then, for yourself whether he knows the rivers and the jungles, and whether he is a fit man to be entrusted with your safety. As for me, I would recommend you to him as readily as to myself. Então, it is enough, no?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.