RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

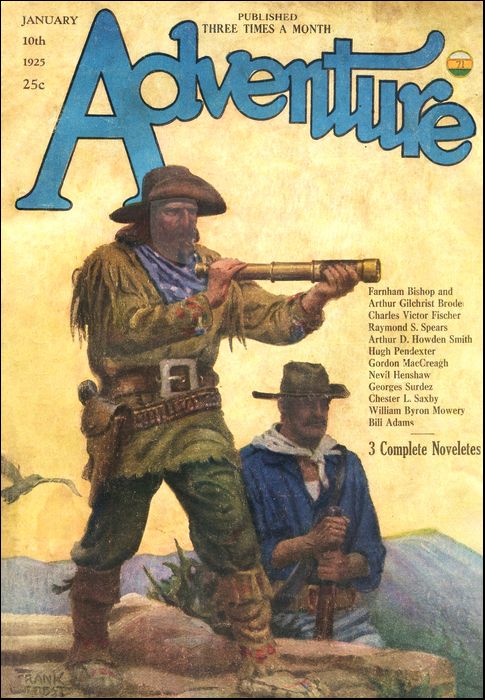

Adventure, 10 January 1925, with "The Courage Medicine"

THE Senhor Americano is a scientifico and would know all about the caapi, the drug that gives courage; and men have told him to seek out Theophilo Da Costa? What, the learned doctors of Manaos City and the vendors of herbs in the marketplace have not already sold the senhor this root and that root and told him that it was the caapi of the upriver Indians?

Ah, the senhor would go to study the caapi in its own place where it grows? Oho, that is different. Yes, without doubt those medicine peddlers would send you to a man of the upper rivers; and to whom rather than to me, who knows all about the caapi?

That, the senhor says, no man knows? The senhor does not understand. I am Theophilo Da Costa; and I tell you that I know of at least one tribe that uses the caapi and that I have witnessed the whole uncanny ceremony that they go through to give them courage for a terrific ordeal. I tell you more than that. I say that I myself have drunk the caapi. I and but one other white man. And as to gaining courage therefrom—well, I don't know. For myself, I, who consider myself no coward, had no stomach for that ordeal. But listen and I will tell you; and the senhor shall then judge for himself whether a man may drink courage out of a drug.

HE was a compadre of the senhor's that other white man. An Americano, and no sort of scientifico at all. He just came to me and besought me with fat rolls cf money in his hands to take him where he might get this caapi of which he had heard; for he sorely needed courage for a certain purpose of his own; and he added, while yet the fear of death was in his eyes, that, having obtained this courage medicine he would have to make a journey into the Rio Branco country alone.

A big man of bone he was; though over-fleshy for his time of youth; and his face held the makings of a whole man in it; but the lines in it were soft yet; and the eyes, instead of the strong purpose of a whole man, held only pleading and the enthusiasm of visions which needed the hardening into resolve.

"Hmm. Good metal," said I to myself, "but unproven."

I could see how it was with him. The youth came of a family of position and wealth, and the way of his life had been made too easy for him. What man, surrounded by luxury and sheltered by much money has an opportunity to find his own manhood?

So I asked him no questions at all about his mysterious purpose or his journey into the Branco. What need? Am I a fool? Why does a young man with fear in his eyes leave all the comforts that wealth can buy and go into the farthest ends of the jungle? Because some woman has made a fool of him and has driven him to the test. We who live in the jungles meet many such; and as they die on our hands they gasp out their tale and send pitiful messages in our care to those others who have had the good sense to stay at home.

And why should this particular young man require to go out into the Branco alone? Did he think I was blind as well as a fool? Did I not know that out of the Branco, which flows down from the Guianas into the Rio Negro, there came tales of diamonds which grew more insistent with every month? And was it not then clear that the woman demanded diamonds as the proof of his courage and devotion?

But who shall counsel headstrong youth when a woman drives? So I said to him only:

"Homem, you can not buy courage; nor can you eat it. But if you must have this caapi, mark well what I say. We must journey to the Tiquié River, no less. A river of the exact center of the earth; for it flows into the Uaupes at the very line of the Equator. A river that is unknown to any of us river men, even to me; for there live the Tucana, who have the habit, not uncommon in this Amazonas of ours, of keeping a strong outpost village at the mouth of their water to warn off strangers; and if the strangers are also fools and insist, they shoot the little darts of the uirari poison at them out of blowguns. The purpose for which you need the caapi of the Tiquié Tucana is your own; but weigh it well, amigo mio, weigh it well."

Still the young man insisted, while he yet trembled at my recital, that his need was imperative; that life without gaining his purpose was not worth living; and he offered to pay me whatever I would.

Pois bem, senhor, we of the upper rivers do not pass a third of our lives amongst savages and a third in dugout canoes and a third in sick bed for the salvation of our souls, as do the good missionaries. So, though I had small relish for the sudden breaking-in of this youth from the lap of luxury into the beyond of civilization, since he had money in fat rolls and the courage to admit that he needed courage, I felt a sympathy for him, who, needing no wealth, was yet befooled by a woman into risking his life to find it for her gratification. So I made contract with him to take him to this Tiquié River and to do there whatsoever I might to make friends with those implacable Indians—which task has fallen to me before now—and to obtain for him some of this courage medicine which he so much desired.

YET the travel turned out to be not so easy as I had hoped. It was just by ill chance a bad time for me. It is my custom to keep a batelão in each of the rivers on which I trade. A stout boat of my own building, and yet as nearly indestructible as our cataracts demand, being indeed no more than a solid body of a long war canoe with an added freeboard of a couple of planks and a palm thatch roof over the latter end of it.

Such a boat will carry two thousand kilos of freight in addition to its six paddle-men and a passenger or two; and such a boat I keep usually at Santa Isabel, which is the furthest station on the Rio Negro which is reached by the river steamer.

But it had been my ill fortune to wreck the boat at the whirlpool of O Forno in the forty-mile cataract of São Gabriel. No fault of mine, senhor. I would take it as great shame to lose a boat through lack of care or skill. But in this case—as my Indians insisted, on account of refusing to make the sacrifice to the demon of O Forno—a whole tree trunk, submerged in the whirlpool, driving suddenly upwards like a battering ram, struck me from beneath and drove me upon the rocks.

Que Deus lhe maldiça.It was a great loss to me. All my freight and two Indians, one of whom was a good man on the bow paddle. So I had to arrange to hire boats as we went along. I made the suggestion to the young man that we wait till a batelão might be built, a question of no more than a month or so.

But the youth was as all you Americanos. When all time was before us he counted time as a thing of inestimable value and insisted that we push forward with speed. Então, the discomfort was his as well as mine; and he, as I have said, was not used to discomfort.

Had I built a batelão of my own design, I would have had a space to swing two hammocks. As it was, we had to hire such boats and canoes as were available and had to make camp—since he found it impossible to sleep in the wet bottom of a canoe—ashore every night.

Sleeping ashore, senhor, in those upper jungles is a laborious luxury. For the jungle grows for miles at a stretch down to the water's edge and out into the shallows. A day one may travel the upper reaches of the Rio Negro and see no shore; only black water rushing between giant tree roots; and how far beyond that impenetrable fringe the shore may lie, no man knows.

Only here and there a point of high land with a rocky front, jutting out of the sea of jungle, offers a camping place. And since the good God did not design the Amazon jungles for man to travel, He did not arrange these camp sites at convenient distances.

As often as not it would be necessary to make camp while yet a good two or three hours of daylight remained; for the next possible spot would be beyond reach within that time. Much of this so valuable time was therefore lost; more, in the long run, than if we had waited to build a batelão. But the Senhor Americano, so queer was his reasoning, was satisfied, since we were at least, as he insisted, doing something.

As for me, I shrugged and continued on in that haphazard manner; for I have long since given up the thought that it might be possible to teach the senhor's restless compatriots to take things easily. It was galling indeed that I, Theophilo Da Costa, who was known among river men, as a maker of my forty miles a day when the currents were not too bad, should lag along at a fifteen or a twenty. But since the man who paid was content, should I wear myself out in the struggle?

And, qué caramba, what more could one do when one must sleep in all the security of a tent in order, forsooth, that the vampire bats might not settle upon one's face. Look senhor, twenty years have I traveled these rivers without a tent, ever since I was a boy; and only five scars of the bats do I carry. But the youth, as I have said, was unaccustomed to the life of a man, and he had truly a horror of the little murcielagos; much more than of the tigre or of snakes.

Clammy things, he called them in his unreasoning fear; and he shrank, as one does under the whine of a bullet, when they flitted by his head. But he grew. The boy grew as we journeyed.

Came a time when the camp site that we had aimed for was in possession of the sauba ants. Why, only the good God can say; for there was nothing to eat on that bare, outjutting rock; and what man can explain the doings of ants? Except that it was dusk, and that the sauba go about their fiend's ways at night.

I showed the fearful one how one might sleep in security among the sauba by laying a trail of farinha meal round one's blanket; for they, as long as there was good food left, would carry that off grain by grain and would not pass the barrier to molest the sleeper; being by preference eaters of roots and leaves and anything, in fact, that grows. Though they are no bigots, I can tell you, in that respect, as the innumerable scars on the legs of all jungle men will attest.

It was evidence of the youth's growing confidence that he agreed to sleep at all in the circumstances. Though the mountain of good farinha that he built around his cot—for, believe me or no, senhor, he carried a cot to sleep in—caused my Indian paddle men to draw in their bellies and groan.

But consider what mischance must needs happen for the benefit of this man who was struggling with his fear. I awoke in the night, sensing that strange something which always rouses the jungle man. Without moving, I listened. There was no sound except the steady, soft, clip-clip, of the ants' jaws, as was to be expected; which was comforting reassurance in itself that no wild beast was anywhere near us on that rock.

What then, had awakened me, I wondered. I felt for my rifle and listened still. Then all at once I realized the strangeness. The sound of the clipping jaws, beside being all around me, was also above.

"Dientro," said I. "Do they fly too, these accursed ants?"

I opened my eyes; and lo and behold, where I had gone to sleep in a tent, I saw now the stars clear above me.

"Defende me Deus!" I exclaimed as I rubbed my eyes. "Has the tent blown away?"

And with my speech the young senhor spoke to me at once, showing that while he had indeed lain down, he had slept not at all.

"The roof," said he, "has been disappearing piecemeal for the last hour. What new plague of the jungle is this?"

And there was anger in his voice besides the fear. A good sign. For it is my observation that anger and fear do not mix well.

"Name of a name!" said I, "I thought I knew all the mischances that might happen in the jungle. But this is new. Lie still my friend and pray that the rock does not melt from under us."

As indeed was all that was possible. Marooned we were within our charmed circles of farinha meal. And, believe me, senhor, one does not step abroad in the night when the sauba are on the path. An inch long they come in those jungles; and their jaw-spread is the greatest of all the ants; a quarter of their length, no less. So I made sure by match-light that my barrier of meal was still sufficient and dozed again till the dawn; our very isolation being, as I have said, our security.

And with the first light what do you think we discovered? Caramba, that the ants had made a highway along the tent ropes and had eaten up most of the top!

Why, who can say? Unless it was that the lower wall portions were wet from contact with the weed growth of former camp sites while the top remained dry; and who can guess what new thing the sauba will eat? Leggings I have seen them demolish in a night; and shoes; and well-worn tasty breeches. But never having slept in a tent in my life, how should I know that they would relish tent cloth?

"This," I told the boy, "comes of sleeping on shore. In a boat one has security, even though it be wet."

And he, forsooth, was able to laugh at me.

But out of that evil came good. For the tent being now useless, that weight was perforce discarded; and he learned to sleep like the rest of us, with his head covered by a corner of his blanket against the visits of the bats.

But, having overcome that fear, he was beset now with an anxiety that he lacked the protection of walls, of something, even though only canvas, against the beasts of the night.

Truly, that youth of the cities was able to think up more dangers than I ever knew about. But he grew out of that too, in time; and there came a day when he discarded a cot and learned to sleep in a hammock slung among the trees, thereby reducing by a full half the labor cf making camp. But that was much later.

So we progressed. Though slowly enough. For this matter of hiring boats from local rubber men and nut gatherers is an unsatisfactory business. To begin with, they do not care to rent out to people going the good Lord knows whither; and it was only that I, Theophilo, was known to them that enabled me to get boats at all.

And to go on with, those local paddle-men whom those petty traders supplied would not go beyond the borders of their own tribes. So our progression was in a series of small jumps of a few days at a time with a more or less tedious period of bargaining between each. As yet we had experienced no hardship of travel.

WE reached the great caxoeira of São Gabriel in due time; and I put the proposal to the boy that he could take an Indian as guide and walk the safe jungle trail of forty miles and camp there for a few days till I brought the boat up through the cataracts. He hesitated over the plan, and I could see that he clutched eagerly at the thought. But there for the first time I saw determination creep into his eyes; and he said, no, he would stay in the boat with me and see how it was done.

"Good lad!" said I, and no more.

And so he stayed in the boat; and while his eyes grew dark with alarm as we hung on the edge of a whirlpool or hauled up against a stiff current, trusting to a rope which an Indian had made fast to a tree, he made no other sign; and after the first day of it he was able even to light a pipe and hold it between his teeth—where it duly went out for lack of drawing.

But he grew all the while. His astonishment at finding at São Gabriel a feeble old priest of a mission was an act of a comedy.

"How did that old man ever get up here?" he kept demanding. "Is there a season when the water is different from what we have just gone through?"

"Assuredly there is," I told him. "In the rainy season the water is much different—and then one does not pass at all."

But the thought of that feeble old man living there, unprotected and isolated from all civilization, took hold of him, I could see, and he pondered on it deeply.

"Here commences the real jungle," I told him, laughing. "For this is the final outpost of civilization. Henceforward, hard travel."

Whereupon he called upon the inferno in the manner of the gringos and demanded what I called the travel that was passed. And what do you think was the first hardship that struck him? The fact that we left our money in the care of the good priest against our return. For after São Gabriel money is but valueless weight, and a kitchen knife is worth more to those farther Indians than the same weight in gems.

But to this young scion of wealth the thought of being without money, coins, in his pocket was truly the leaving behind of the last vestige of all things that he had been brought up to require. And verily for a while his imagination seized hold of the fact to build up for himself a host of new fears about things which might now happen.

But he outgrew it as he had adapted himself to other things. And by the time that we reached the double stream, the one half the black water of the Negro and the other half the white water of the Uaupes, he was asking with bravado what dangers there were here worse than below the last limit of civilization.

But the fly belt that we passed through with our entry into the Uaupes soon put a damper on his bravado. As for me, I am dark complexioned and well burned by twenty years of sun, and on my face they do not show. But on his fresh white skin those myriad piumes of the Uaupes, that raise a tiny blood blister with each bite, made such a fiesta that at a short distance the pustules merged and he looked like an Indian.

Yet at this, though he groaned at his defenselessness, he did not complain. Here was merely discomfort; and discomfort he had grown to accept as a part of the daily travel. It was nothing to fear; and it was the thought of fear that obsessed him.

"Senhor," said I to him, for we had grown to be friendly enough to talk of things intimately, "what is this fear thing that you are afraid of?"

And he thought a while and answered.

"It is just that. I am afraid of being afraid."

"Afraid of what?" said I.

He replied that he did not exactly know. He was afraid of all manner of things that might befall. All his life, he said, he had been the scorn of his youthful companions because he shrank from doing the things wherein danger might lie. Their sports and their contests and their wild rides in automobiles; all these held terrors for him. Particularly was he afraid of facing his fellow man in controversy. He had never had a fight, though often teased and beaten. All these things were a source of unspeakable shame to him—and, he added with some hesitation, to certain others.

"Oho," said I to myself, "to the woman, of course, who scorns him for his pusillanimity."

And I sought to comfort the obvious shame of his self confession by telling him that all men were afraid of something or other at some time. Whereat he returned quickly:

"Yes. But they have the courage to go on in spite of it."

"Good," said I. "Then we have no need to go any farther on this wild chase after caapi. For you have been afraid, yet you have come thus far."

Thereupon he turned red through the purple-brown of his piume bites and murmured that he realized now the shame of all his little fears where it turned out that no danger had existed.

"M-hm," thought I to myself. "There has been no time in my life's knowledge when we have not considered the passing of the caxoeira of São Gabriel as six days of concentrated danger."

And it came into my mind that the trouble with this youth was but a confusion between courage and confidence. He had been too sheltered in his upbringing to know that he could meet and overcome the unknown danger which might exist—which knowledge, after all, is the courage which enables a man to go on.

"Well," I told him, "be of good heart. Dangers will be familiar traveling companions of yours by the time you go alone on that business which calls you to the Rio Branco."

And there, as I had once before seen the first sign of determination come into his eyes, I saw now in his face the beginnings of the hardness which comes to a man who finds his own spirit. He said nothing. But I felt sure that when a danger came he, though he might lose his head—as who may not who is unaccustomed to meet danger?—he would at least not run away from it.

And in truth, when we fell presently into a real and very immediate danger, he recognized it no more than he had the peril of the caxoeira.In this wise it came about.

THE last of the old rubber outposts had been at a place called the Isla Jacaré, the Island of Alligators. Here remained now a former rubber agent by the name of Manduco, a brigand by birth and a killer of defenseless Indians. With him I haggled for three days for the hire of his leaky old boat of the rubber days and for six Indians to paddle it.

"Canastos," he growled, "for ten years, ever since the accursed rubber lured me into this country and then left me high and dry, I have prophesied that Theophilo Da Costa would go once too often on one of his wild trips; and this one is it. Who will pay me for my boat when you never return from the Tiquié?"

But I told him I would give him a letter to the good padre of São Gabriel to pay him one hundred milreis for the hire of his boat; and his Indians I would pay in trade at the rate of six meters of print cloth per man for each month that I used them.

"As for the Indians," he said, "you may pay them a meter a day or nothing at all, as you please—until they run away from you in this Tiquié country. But for the certain loss of my boat that is not enough. I suppose that missionary has relieved you already of everything that is worthwhile. Half his income comes from the effects of fools who go up river and never return; and the other half from the few wise ones who are so glad to get back that they make an offering. Why should I also not make a profit on your death?"

And to that he stuck till I had to agree to pay him the full price of his boat, and then he tried to cajole me into leaving the half of my gear in his keeping. But since I remained obdurate, he made other plans for its acquisition.

Six Indians he provided with his boat; and he stood on the shore to tell us with emphasis adios, the final farewell, instead of até logo, adding as the last cheering word:

"It is but three months ago that the canoe of two feather gatherers floated down from somewhere up there, empty except for a zarabatan, a blow gun, laid carefully in the very middle."

And he grinned at the merry jest. The young senhor, who was beginning to understand Portuguese, asked me if any of all this talk might be true. I shrugged.

"Who knows?" I said. "The man is a liar by heredity. Yet, if true, those were two of the many fools. We are two of the few wise ones."

And I told him further that the wise ones came back to make offering by the simple method of doing nothing foolish; and it would be foolish not to watch very carefully those six Indians of Manduco's. For I could see within the first day that they were no paddle-men; but villainous dependents of that arch villain, relatives, no doubt, of his sundry women.

Whereat the youth said nothing, as was his way when he pondered deeply. But presently I saw him with determination in his face removing the old cartridges from his pistol and putting in new ones; and I wondered by what observation he had learned that precaution.

Yet in spite of precaution and my boast, we were not quite wise enough.

It had been my intention, upon reaching the Rio Tiquié, to tie up at the opposite bank from that at which it entered the Uaupes, and to send then an Indian with my carved stick to the chief of their outpost village to institute negotiations before venturing our necks into that territory.

Yet we traveled up on the right bank, the Tiquié side, because Manduco's Indians said that since we must needs make camp ashore, good sites were available on that side. Which indeed was true, and which I was glad to know; for my custom had been always to keep the left bank, with a mile of good water between me and that Tiquié of unsavory reputation; for it is the fools who run risk when there is no need.

It happened thus that on the fourth night we made camp on the right bank, the last before crossing over to the other side. I was having my day of the terciaria malaria, which takes me always at sunset and lasts for three hours before the ague passes and I can walk again. Else we should not have fallen so easily into the trap. But I was in no condition to note localities and signs.

My chill was upon me when we arrived at what seemed a suitable place; so I staggered ashore and shivered in my hammock, while the camp arrangements fell upon the shoulders of the young senhor. All of which he carried out with the dispatch which he had learned, and it was only his inexperience in observation which held him from suspicion.

And it was also our good fortune that the boat leaked abominably; for which reason we had instituted the custom of putting ashore overnight most of our goods and gear which would suffer from wetness.

So it came about that while I lay helpless, there was a shouting and a splashing and a cursing; and the explanation of it, when I was afoot again, was that while the senhor had been busy with the stowing of gear those crafty Indians had quietly slipped the rope and paddled off downriver in a panic with such goods as remained on board.

IT was then that I gave the senhor leave to curse me for a fool. Treachery I had expected from that rogue Manduco; but a petty stealing of a few bolts of cloth and some food, never. The loss was not great. Some little cloth, as I said, and a vast weight of food in tin cans which we had dragged with us half across the continent because the senhor had deemed them necessary for his subsistence.

So that, in spite of my rage against that petty robber, I was able to laugh at the misfortune; for truly that bulk of metal had been a sore trial to me. And presently, as I moved about the camp with a lantern, picking up the signs that I now found time to observe for the first time, I heard the boy laughing also; and he said that he laughed at the thought of the pleasant surprise we should afford to Manduco upon our return. Then I told him:

"Amigo, here is no laughing matter. The stealing of our gear is nothing; but there was more to that plan of Manduco's than just stealing; for the loss of a boat in these upper rivers is as serious as the loss of a camel in the desert; and without a craft of some sort we can neither go back nor forward."

"Pshaw!" said he with the confidence that was becoming his habit. "In a week we can build a raft and float back with the current to have our little talk with Manduco."

"Assuredly, my friend," I told him, "when time is of no value one can build anything, even a batelão. But just now are the little minutes of time more important than ever in your life. For all the very plain signs tell me even in the dark that this high land is a well-used landing-place for canoes—and I know of no settlement along this shore except the Tucana outpost of Taraqua."

It was here that I expected him to demonstrate some of his fear that he so bragged about. But he, after a silence, said only:

"The place of the Indians who use the caapi? Then we have arrived."

Ma'e Deus! I would have held discussion with the madman as to what need he had to go hunting for caapi.But here was no time nor place to argue.

Stranded we were. Marooned upon the edge of the thick jungle on a little strip of high land which led back straight to the most hostile village in all the upper Uaupes. Some sort of preparation for defense was the first necessity.

And yet, what would be the use? What defense can two men prepare in the dark against a village of a hundred warriors who could creep through the blackness like jungle cats and blow a noiseless dart tipped with immediate death out of nowhere? There was nothing that one could do except promise offering to the mission chapel on the one hand and to hope on the other that the Taraquanas might not be in an ugly mood.

As for me, I sat surrounded by weapons and did both with fervor and concentration for the rest of the night. The senhor, too, loaded up his sundry expensive guns and sat silent on his cot—doubtless praying.

Whether it was the promises or the prayers which prevailed, I can not say. But the morning finally came, and we were still alive. Never was I more thankful for daylight; and I was prepared for it.

Between donating my belongings piecemeal to the greater glory of the good São Gabriel, I had been planning and cogitating and replanning; and my decision was to play the bold course—since it was the only one open—and to trust to the luck which had always been with me in my dealings with bad Indians.

SO I took my carved stick and, holding it well in view, I walked up the path which led to the village, looking neither to right nor to left, though I knew that I passed through a lane of Indians lying in the underbrush with blowguns to their lips.

By the grace of God no signal was given, and I reached the clearing on my own feet. Some two hundred meters back from the river it was, with three great community houses, molocas as they call them, fronting it; and it was empty of all life, even of fowls and dogs.

The central moloca was, of course, the council house, a long barrack of forty meters in length by a frontage of twenty-five, built of the split trunks of chunto palm and thatched with its leaves. No sign of life moved, except the eyes of two thick-set warriors who leaned naked upon their tall feathered spears before the closed door.

I knew that this was ceremonial, and therefore that some move had been expected of me before deciding on the killing. The closed door—which ordinarily among all those upriver Indians would remain open the year round—was a sign that welcome was withheld. Speaking, therefore, no word, I planted the sharp end of my carved stick in the ground before the council house and went back the way that I had come.

My calling card had been delivered—though it was a great loss of dignity not to have sent it by the hands of a servant. Still, the ceremony of delivery had been accomplished, and upon its reception hung our fate.

As I passed for the second time through that lane of hidden Indians I promised the half of my goods to the altar of São Gabriel; and the dignified walk at which I had set out increased to the swift stride of the jabiru stork, while the little hairs crawled all up and down my back.

"Now," said I to the young senhor, "be very much afraid and make prayers that there has been no recent misfortune in the village which the witch-doctors can blame upon us."

For I was in no mood to be soft-spoken, and I judged it best to let the panic run its course now rather than be hampered by a fear-crazed youth later when the need for action might be imperative. But he, though his eyes indeed showed the pain of an extreme effort of the will, answered nothing.

Till finally, between his teeth:

"No, my good friend and guide. I have learned that the time to be afraid is when you show anxiety."

"Meu Deus!" I cried. "I show it now, for this hour I consider the most anxious of my life."

But he grunted forth a hard laugh and made oath after the manner of you Americanos.

"Shucks of the corn?" he said. "No, my friend. You are not yet afraid."

Yet indeed I was. Afraid down to the cold marrow of my bones. Though how was I to show it to this maniac who considered that he held a monopoly on fear? Nor could I convince him during the long period of waiting which followed; and he sat and waited as I did, cold-set and silent.

But the luck, it so happened, remained good, and no silent death streaked out of the jungle upon us. Instead, there came as the day wore on, a sturdy man of middle age who wore nothing but a G-string and a tassel above his left elbow made of the hair of the red howler monkey and of toucan feathers; by which I knew he was a sub-chief.

He carried my carved stick and another, both of which he planted in the ground and then squatted behind them. I squatted immediately as he did, facing him with the sticks between us; and he gave then the greeting, speaking in the language which we call Geral, which is a lingua franca for inter-communication among all these Indians of upper Amazonas.

"Hath the á puré, Kariwa," he said. "The stick of Theophilo is known to us by hearsay. So the chief of Taraqua, whose name is K'Aandi, sends his stick to you."

It was then that I promised the rest of all my goods to the mission chapel in honor of all the saints by whose grace I had maintained a reputation for fair dealing among the Indians of the Bahuana and Desana who bordered on these Tiquié Tucanas; and at that moment I wrote off as well, and over-well spent all the extra little items of trade goods and the good measures of cloth which at times had seemed less necessary than keen bargaining demanded.

That I spoiled the Indians was what was thrown up to me by other—and less successful—upriver men; and my answer henceforth I considered as ready—that I had well spoiled then, Deugraças."

The chief's personal stick was a sign of the return call; and I knew that welcome was extended to us, a thing that had not been known from these Tiquié Tucanas to a white man before. It was the ceremony now that we send a present back to the chief with his stick. And what, thought I, would be a most unusual and honorable gift?

I cast about swiftly in my mind—and then I saw it, lying hatefully before my eyes; and such was my relief from the anxiety of the last hours that I was able to laugh out loud.

"Ho ho," said I to the senhor. "The acceptable sacrifice is to hand. We must send him, as a gift never yet seen in these parts—your cot."

And without more ado I snatched the cumbrous thing from where it still stood after the night's use and piled it upon the broad back of the sub-chief and packed him off. And I laughed anew at the sight of his dignity under that thing of struts and hooks and canvas, and then turned to laugh at the face of the senhor as his last comfort of civilization was torn from him.

THIS indeed was his greatest hardship of the whole expedition; for he was one of those who had pampered himself to the belief that sleep was a function of importance which must take place in a feather bed; and he had considered it a hardship enough at the outset to sleep upon this thing, even with a vast roll of a mattress which cumbered the canoes and boats of our travel till the wetness which it sopped up out of the bilges rendered it more of a weight than one man could lift, and the mildew finally rotted it away.

Thereafter he had clung to the cot as the last remnant of things necessary to civilized man—even after he has given up shaving and permitted his beard to grow. His face, therefore, in the present circumstance of relief was a source of much joy to me. Yet presently he, too, was able to laugh; and I smote him on the shoulder and said to him:

"My advice to you, amigo, is that when the chief asks what present you want in return, you tell him a grass hammock. For in a hammock you must sleep henceforth; and a hammock such as this chief will present will be a wondrous thing woven by hand from hand-twisted fibers and embellished with the feathers of humming birds; a work of one family for a year. Take it and bring it back to your own country to brag about when you return; for the Americanos who possess such are not many."

Which he did. And the hammock which he received in exchange for his accursed cot was indeed a thing of beauty.

The chief, K'Aandi, when the long ceremony of the greeting and the introducing to the tribe with the smoking of the great community cigar was concluded, must needs be shown like a child how the toy worked.

In his own corner of the moloca—which among all these Indians is the far left one from the door—he squatted over the thing while we demonstrated its collapsible virtue; and it was a wonder to me how in that community house of fifty families where there was no privacy other than a low rail to mark off the little three-meter section of one family from another, the rest respected his privacy and went about their business taking no more notice of us than if we had been shut off from their view by stone walls; though they must have been torn asunder to see the working of this marvel.

As for the chief, so absorbed was he with the mechanism of the foul thing that it was not until he had learned how to take it apart and reassemble it with his own hands that he was content to recline upon it and fill his cheek with a wad of the ipadu powder and ask of us what was the reason of our coming.

I judged it wise to tell him a tale so marvellous that all suspicion of encroachment upon his country by the white man or of exploitation of his people would be immediately removed. So—

"Kaa, Father of Andi," I told him, "this youth who accompanies me is from a place of many molocas on a river many years journey by canoe from here. Unlike all other men he is, in that he boasts that he has fear. He is afraid of all manner of things, and he would undergo the caapi treatment to cure that fear."

So great was the astonishment of the chief that the success of the story was instant. He paused with a bone spoon of the ipadú half raised to his mouth and called sundry of the sub-chiefs over to his corner of the moloca to view this wonder, one much more amazing than the miracle of the folding cot. With their own ears they had to hear me repeat the accusation; and they clicked their tongues and murmured, "Qua gani?" in their astonishment that the other did not resent it.

For, as among all savages, as the Senhor Scientifico will immediately understand, courage was to them the first attribute of a man, ranking even before strength. It is my observation that moral courage, the courage to admit that one lacks courage, is the development of civilized man.

So amazing was this confession to those savages that all thought of doubt against us was immediately banished from their minds. So extraordinary a reason for our coming must be true; and the chiefs squatted in a half circle facing the wondrous enigma and had me ask him innumerable questions as to what he feared, and if so, why?

Did he fear the tigre of the jungle, they wanted to know, or venomous snakes? Or fast water among rocks? Such things they could understand.

But, well—er; no, not just those things so much, replied the young senhor. But—

"But what?" they demanded.

What more was there in a man's life to fear? Enemies? Why? What could one man do that another might not; and in warfare was it not a matter of luck whom the darts struck and who escaped?

No, he had not just thought of enemies, replied the senhor, finding it embarrassing to answer these so direct questions about his obsession. In fact, he said, it was not so long ago that he had been through a very big war.

"Not enemies? That was good," said the chorus of chiefs. "Well, what then?"

Ah, they had it! He feared, of course, the Juruparí, the devil-devil who lived in the fierce thunderstorms of that equatorial belt; and in the dark jungles and in certain deep pools. That was understandable, and not so very shameful; for while they themselves, the Tucana of the Tiquié", did not fear the Juruparí, they knew that many other tribes feared him greatly; and they were none the worse hunters or warriors for that.

But here the senhor was on safe ground.

"By no means," he shouted, and he laughed at the thought. "The Juruparí of all things he did not fear."

"Amm-ma parú!" muttered the savages; and they clapped their hands to their mouths.

For, while one might not fear the Juruparí, one hardly ventured to laugh at him.

Forthwith innumerable further questions they showered upon me to ask this most peculiar young man. Would he really dare to stand out in the open in a thunder shower? And would he dip his hand in certain black pools that they could show him and call upon the Juruparí to take him if he could? And would he even stand alone without weapons for one hour under certain trees in the deep jungle? Anu-i quá! He must be a very great witchdoctor.

Then K'Aandi, the chief, who had been studying this phenomenon, pointed his finger at the youth and said to me:

"This I would know. Ask the young Kariwa who laughs at the Juruparí why he keeps his fear? Of what value is it to him? In what way does it lessen or remove a danger?"

To which reasoning there was no reply. The mystery remained; and it was with difficulty that I was able to drag my so interesting exhibit away to return to our camp and prepare a meal for ourselves.

"Behold yourself," I said to him. "You are become a portent in the land; a wonder to all the tribe and a subject for conversation over the cooking fires for many a night to come."

To which he answered nothing. For he was wrapped in a deep cogitation within himself. It was clear to me that the simple and direct questions of those savages who had no unhealthy imaginations had set him to thinking profoundly upon this question of fear which had become so complex a thing for him, as against the reasoning of those primitive minds to whom fear was a concrete thing, having a definite object; a wild beast, or an enemy, or a devil.

After a long silence, while I prepared the meal, he spoke suddenly out of his dreams.

"I realize one thing," he said, "and that is that timidity before an unknown possibility is the product of a civilized imagination."

After which he relapsed again into his meditation; to which I left him in peace; for it is my observation that where reason comes to the fore, fear must needs be pushed into the background. Only of one question I reminded him, which those naked Indians had pressed.

"Of what value was fear? In what way did it alter the danger?"

And I left him to find the answer to that simple question out of his own philosophy. Yet, simple though the question and propounded by a savage mind, the finding of the answer for himself occupied that young senhor for many a day of deep thinking with his chin between his hands.

Time there was, and time to spare. For while we had been accorded the hospitality of the tribe instead of a swift death—thanks to the good repute of my carved stick and to the wondrous story of my inexplicable companion—it was a far cry yet to the gaining of their confidence to the extent of acquiring the caapi, which was a very secret drug attended by an elaborate ceremony of initiation, as is attested by the great Americano explorer, the Senhor Doctor who writes that he has no more than heard of it.

The matter had to be taken up with the ipagé, the chief witch-doctor; and he, of course, had to make a magic of many days before he could come to a decision. To which end I take credit to myself that I was able to help him.

I make but two rules in my dealings with all those Indians of the upper rivers. The one is, having struck a bargain, to give just a little bit more than the bargain demanded; and the other is to make friends with the witch-doctors, as I did in this case.

I sent him first a present of a whole pound of salt; after which he lost no time in sending for my inspection a stick of a most wonderful and elaborate caning, a whole book, indeed, symbolizing his wisdom and his exploits.

After that I became an intimate of the old man's; and a most kindly and shrewd old wizard he was. Pot companions we were; for over many a gourd of the foul-smelling juice of the caju fruit he asked me a thousand questions about the world beyond the Rio Tiquié—which meant to him downriver as far as São Gabriel, where there lived, so he had heard, a white witchdoctor who could cure sicknesses.

A point of view had this old man which was most entertaining. Of the sea, for instance, he could form no conception. A water that would take many days to cross. That must be a very big river, said he.

A house of stone he could not understand. Why, he asked, when the chunto palm was so easily split and was proof for all time against water as well as insects?

A river steamer capable of carrying a thousand people, he very politely disbelieved. No tree trunk that could be dug out grew that large, he insisted.

Yet he was able, speaking of the young senhor, and discussing this fear of his, to say:

"Why is a man what he is? Ask of his father and his mother and of his upbringing."

No fool was that old man. Yet he had his superstitions

"Is it true," he asked one day when I brought the talk round to the matter of caapi, as I did on all occasions, "that he is a witch-doctor among his own people, as some of the young chiefs say?"

And I, thinking to further his quest by representing him a man worthy of initiation into knowledge, answered quickly that indeed he was the greatest of necromancers in his own country.

Fool that I was! I might have known that the first instinct of all savage wizards is to see proof of the wizardry of others. Into the same foolish trap that a hundred others have fallen was I now fallen myself. I, who profess to know Indians.

SO here was I, faced with the necessity of finding a bagful of tricks for this useless youth of mine. I went to him and demanded what tricks he had learned during his long life of leisure when all time hung upon his hands instead of the need of making a living. And he answered me with uplifted eyebrows—"Nary a trick."

"Think, man," I cried in despair. "Think! What can you do? What do you know out of all your colleges that will be miraculous to this savage who knows nothing?"

And he answered helplessly again—

"Nothing."

So we sat and cudgeled our brains; he suggesting at haphazard what might be done with simple chemistry—had he but the apparatus and could he remember how it worked. Till I demanded of him in exasperation, what did the expensive academies of his country teach that a naked savage did not know?

Yet in the course of time an idea came into his head.

"The other day," he said, "when you lit your cigarette with your burning glass at the sitio of Manduco, a small boy who was watching, ran away. Would that—?"

I fell upon him and embraced him. It is my custom, traveling the upper rivers—where matches, if they do not give out, their heads become moist in the humidity and fall off—to carry a good burning lens which many a time has given me light and fire. Here was surely a magic to hand. So I took the youth to the old witch-doctor and told him a circumstantial tale of how the greater magics of the white man required a considerable time to prepare—which the old fellow could well understand.

"But," I said, "he has a little magic of drawing fire from the sun, which he would give to you in token of friendship."

"That," said the old man cautiously, "would be a very useful magic—if true."

Which indeed it would be in a country where for half the year all things are soaked by torrential rains, and fire must be carefully tended and kept burning lest one have to rub together two moist sticks for half a day.

So at my word the youth picked a dead leaf—this being the dry season of the year—and focused the glass upon it. The response of that tropical sun was instant. The little spot of light blackened, smoked, and burst into flame. All in a second.

"Amm-mul!" said the wizard, his hand over his mouth. "That is a very powerful magic. And he added quickly—

"Who else of our people has seen it?"

"No one," said I promptly.

And he, with naive confession:

"That, then, makes it ten times more useful. And—and, my brother, the young white wizard, will give me this magic and teach me its workings?"

"As a token of friendship," said I, "asking nothing in return."

So the newly accredited wizard showed his older brother in the craft how to work the thing and taught him even an incantation, something to the effect of, "Hokum, soakem, get the oakum," and so forth, which I now forget.

And he left the old man to practise his new magic with the greatest wonder and delight of his life—as who would not, having boasted of being a wizard for fifty years, and possessing now for the first time a real wizardry?

Thus it happened that within a day or two the wizard came to our camp to make a personal call and to say that a caapi ceremony was being prepared, though not for some twenty days yet, at the dark of the moon; and that the young white wizard, if he still desired, could then go through the ceremony with the young men of the tribe; and then, if he proved himself worthy, caapi would be his according to his needs.

I smote the senhor on the shoulder and told him:

"Alegra vós, rejoice, for the aim of all our traveling is achieved. You shall see what no white man has seen; and the medicine of courage shall be yours—if you have first the courage to get it. And believe me, when I tell you, amigo, I who have been asking questions about this ceremony, if you can get it, you do not need it."

But his face set in the expression of determination which was becoming his habit, and he said with doggedness that he needed it for his purpose and that he would surely go through any old initiation ceremony to get it. Yet I, who had learned that this ceremony was no mere play of youths at an academy, shrugged and wondered.

WHAT need to weary the Senhor Scientifico with an account of our living during the next twenty days? We did as all men do in the jungle. As for the youth, I advised him to climb every day a tall tree and to swim a thousand meters and run a thousand; for this ceremony was one of endurance as well as of courage. Which things he did, though, in truth, he had not much need; for hard travel had removed much of the softness from his big frame.

And as for me, I built me a new batelão for our future travel; purchasing a dug out canoe—a labor of three or four men for as many months—for its own length in print cloth; and adding to it a freeboard of three planks, hand-hewn out of luiru tree trunks, for which labor I paid a pair of sturdy youths a kitchen knife and three fish hooks apiece. For the rest, I moved about the molocas and observed the ways and manners of the people, as is my custom, against my future need.

Time which for me was well spent. But the youth fretted. He was nervous, it was clear. He had keyed himself up to the highest pitch of resolution of his life; and the tension of waiting wore him down.

But the last of the moon disappeared finally and left the night as black as the stars would permit; and the time was at hand.

The ceremony was to take place, not here at the outpost village, but five days' journey up the Tiquié River, in the heart of the Tucana country.

So there set out from Taraqua a flotilla of canoes containing only sturdy young men, each with a carefully wrapped palm-leaf box. K'Aandi, the chief, apportioned me six youths as paddle-men for my batelão under the charge of his own nephew, and sent by his mouth a message to the chief of the village to which we journeyed to say that Theophilo the Kariwa was his friend.

The old wizard had gone on before to collect his lesser wizards and make preparation for the ceremony, which appeared to be a big one; for, as we traveled, small detachments of naked youths, all with palm-leaf boxes, joined us from other villages.

Of travel on the Rio Tiquié what is there to tell? Except that, as usual, those other Indians had lied to me when they told me of the terrible caxoeiras to be traversed. Cataracts there were, of course; but no worse than many another on the higher Uaupes.

Yet such is the custom of Indians, to report fearful things of any country that they do not know. Also it is good to know that on this river which crosses and recrosses the equator some twenty times there are more flies and noxious insects than in all the rest of Amazonas; and that while the days are the very steam of the fiend's brewing, the nights call for two blankets. Food need not be carried; for the water is good and monkeys are plentiful.

Arrival had been timed to the day. In the noon hour we came to the village, a big one of five molocas, all facing the river, with a great clearing before them.

The canoes were hurriedly dragged ashore; and without loss of time the young men, squatting in groups all over the clearing, proceeded to open their boxes and, producing from them gourds of paint and the most elaborate of feather headgear and fringes and trailers, spent the rest of the afternoon in dressing each other up for the ceremony.

Something of the reason and the nature of the ceremony I had learned, which the senhor, being a scientifico, will be interested to know.

Most of those upriver peoples, you must know, have no conception of a God to worship; their nearest approach to religion being a belief in the Juruparí, a spirit of malignance to be propitiated. But these Tiquié people are in this respect different from all other primitive peoples whom I know or of whom I have heard. Instead of propitiating the evil spirit, they, being a fierce and untamed people, their practise is to fight him.

Thus, when the mandioca crop has failed or the fishing is bad or there is sickness in the village, instead of offering gifts to the Juruparí, they go through an elaborate ceremony of defiance, a protracted affair lasting for three days, during which they show their devil, first, that they are a strong, virile people of much stamina; and culminating with a personal meeting with their devil, at which they demonstrate to him that they are in no way afraid of him.

And it is here that this mysterious caapi comes at last into use. For since this meeting with the devil in person is an ordeal requiring considerable courage, the warriors nerve themselves up for it with the courage medicine.

After which, the young men who have passed the ordeal successfully are entitled to wear the head-band of red monkey fur at ceremonial gatherings—though, caramba, they need no such recognition! For their devil leaves his mark on them plainly enough—and they are entitled also to carve a ring round their sticks, and to obtain caapi from the witch-doctors for all and sundry purposes, such as warfare and so forth.

This ceremony, then, began with dusk on the day of arrival. The whole village, men and women, with the visiting warriors, some three hundred people in all, engaged in the opening; the men naked except for paint and parrot feathers, and the women without even paint.

Being gathered in the great clearing before the molocas, a shrill hissing whistle was set up by the musicians, and the whole crowd swiftly formed a circle, arms interlocked over each other's shoulders, and commenced the performance of an interminable snake dance—the prevalence of which among all Indians the Senhor Scientifico has doubtless written a book about.

In the center of this great weaving, twining circle stood a woman heavy with child and holding by the hand a growing boy and girl. The significance of this being clearly, as I have said, to show the malignant spirit who oppressed them that they were by no means a dying race.

After an hour or so of this demonstration, the woman quietly withdrew; and the dance continued with variations and without intermission throughout the night and the following day and night and the next day. This to demonstrate the stamina of the tribe.

The chief and the older men, of course, dropped out early in the ceremony and sat round on low wooden stools carved out of a single piece, keeping a sharp eye on the young warriors to see that when a man slipped from the line to snatch a bite of food or a drink of water he did not dally for too long. Ten minutes or so being the limit before he was driven with jeers and derisive calls to rejoin the dance.

And all the while there was kept up an accompaniment of soft reed flutes blowing a plaintive melody with a rhythm on each fifth note to which the dancers stamped time with their feet. So persistent was this rhythm that as the hours passed I felt all my senses sway to its unvarying beat and my body almost float in a manner which I am unable to explain.

But the Senhor Scientifico, who has doubtless written a treatise on the power of rhythm, will understand better than I.

As for me, I shook the growing intoxication from me and went around in the dark to look for my young man, whom, in the interest of all these doings, I had lost sight of. And where do you thank I found him at the last?

IN A corner of a moloca, stripped down to a breech clout, and in the hands of a group of old women who by torchlight were painting him with red and yellow ochres and bedecking him with feathers of the macaw and toucan. In his eyes was a light of excitement and he laughed with nervous bravado.

"Gee," he said. "I've got to get into this dance thing. It's all a part of the ceremony, and I can't afford to miss it; and—and—"

I, senhor, am a man of the upper rivers, a trader among the Indians and a man of practical habit. I do not pretend to understand the reasonings of emotional youth. Yet I could see that the nervous tension of the last few weeks and that persistent rhythm beating through the dark had carried him off his feet. I nodded.

"It is what I came to tell you," I said. "You must go through the ceremony if you want to get the caapi.But do not lose your head; and husband your strength, for the ordeal which is to come will tax you to the utmost."

He but laughed again and went out and mixed with the other dancers; and they, without a word of surprise or of recognition, simply opened space and took him between them just as one of their fellows. They were all intoxicated with suppressed excitement, as was he.

I watched him, as the hours progressed, with anxiety; wondering whether he could outlast the strain. But I had no need to worry on that score. His body was young and strong as a bull, and the hard travel and exercise had well fitted him for such a trial.

He rested from time to time, as did the Indians. He ate and he drank as they did, and returned again to the maddening sway and stamp of each fifth beat with the other painted Indians. And he never looked at me. The maniac was an Indian.

So the night passed, and the day—during which the dancers passed from the heat of the sun into the shade of the great council moloca, never ceasing from their loops and circles and serpentines—and so also passed the next night and the next day.

I tell you, senhor, that was a test for an athlete. The women had long since dropped out of the dance. The men of middle age had been retiring in ones and twos. Only the young and the strong remained, swaying, swinging and stamping to that infernal rhythm.

And with them, my young friend, whom I now recognized only by his height; for the sweat running from his body had so mingled the painted designs that he was as the other Indians, a daub of crazy color.

The older men drooped on their stools in sleep; and at last, as the second day wore on, the dancers, too, began to show signs of weariness.

Then came the caapi.

A drink which ceremonial cup bearers, distinguished by a special head gear of egrets' plumes, served in little gourds. All partook of it; for all were about to see the Juruparí—all except the women. Those who still danced, the strong young men who were going to face him in ordeal, partook of it copiously, dropping out from the line as often as they felt the need.

I, too, sitting among the chiefs, partook with them; and this only I can say about it. The liquid was almost colorless, flat tasting and somewhat bitter. Stimulating it was; for the weariness passed from the dancers with the first hour and the sleep from the eyes of the old men. Exhilarating too; for I, who am a practical person of no imagination, felt—how shall I say?—free of care and responsibility. Careless, rather, of my actions; for I felt impelled, in spite of my forty years, to give way to that accursed rhythm that beat so incessantly into my temples; to don paint and feathers, and to join young senhor my friend, who danced and stamped with such abandon.

Like strong wine was the exhilaration; but by no means alcoholic; for though one drank copiously, there was no dizziness or giving way of the limbs. But as to receiving courage from the potion—well, the Senhor Scientifico shall hear and judge.

As the day drew to its close the conduct of things began to change. The dancers, though they surged and stamped with an increased vigor and enthusiasm, became sober of expression. Their enthusiasm was forced. The ordeal of the Juruparí was drawing close; and this was a matter to be approached with awe.

With sundown the dancers streamed out into the open, and the women were herded together and driven into the great council moloca—for it is death for a woman to see the Juruparí—and certain of the sub-chiefs were posted as guards against their curiosity. Conversation amongst us who watched lagged. As the swift tropic dark closed down men spoke in whispers. A happening of much seriousness was about to take place.

Consider, senhor, the scene.

THE moonless night. The swift chill that comes with the darkness. The great open place fringed by the tall dark molocas and the darker jungle. Away to one side a cold gray river of chill mist. No speech. No sound—except the interminable wail of the flutes and the stamp of the dancers; which had ceased to be a sound and was now only a rhythm that beat at the brain.

In the midst of all this the shadowy forms of the dancers on whose wet bodies the light from just a few little fires gleamed as they passed—and who were suddenly perceived to be stark naked, having shed all their ornaments and feathers; and who danced now singly, each man on his own merits to face with his own courage what was coming.

I tell you, senhor, that even I responded to the theatrical effect of all this and felt the creepiness of the occasion. As for my young man, I could watch him no longer. He was lost to me, merged in the gloom with the other weaving figures.

Then into the silence of that rhythm came a sound. Afar in the jungle at first. Boom-boom, boom-boom, it came. Almost like deep drums; yet too protracted for a drum.

"Aa-aah!" A whisper went up from the still figures who stood about me. "The Juruparí comes!"

And he came swiftly. The booming approached nearer; and I, striving to locate its direction, found that the sound was peculiarly all-pervading. I could not tell from where it came, or how near or how far; except that it grew louder and crashed all round everywhere, till the air was all one booming vibration; and—curse upon it—the vibration was the demoniac rhythm that had beat into my brain for three incessant days.

My whole being tingled to it; and I felt—how shall I say?—mad with all the rest of them. Ready to jump up and do any wild thing which at least would mean action.

Then suddenly one noticed that the shadowy dancers were augmented by fantastic figures weirdly painted with white which glimmered in the firelight. When they came in or how, was unknown. They were just there; and they swayed and stamped back and forth amongst the dancers and blew ever upon great funnel-shaped horns from which issued this so maddening booming. Some one gasped in the dark near me.

"Amm-mu i quá! The Juruparí. Mmá-u! Six to choose from!"

So here was the devil in person. For this, senhor, is their belief: These men, the six who blew upon the Juruparí horns, which symbolized the voice of their devil, all prevailing, were neophytes of the witchdoctors, who, while the warriors were making their ceremonial of preparation, had been in the deep jungle undergoing also a secret preparation at the hands of the witch-doctors.

Details of this preparation I have never learned, for it is secret even from the chiefs. But during that preparation—which is surely some form of spirit raising, for the men appeared to be in a sort of trance—the Juruparí himself had entered into the body of one of them, even the witch-doctors did not know which.

So there, among the six, was the devil in person circulating among the dancers. Here came the ordeal, the proof of courage.

Suddenly one of the dancers, nerving himself to the utmost, rushed to the side line and took a deep draught of caapi from one of the ever-ready cup bearers; and so, stimulated to the highest pitch of his courage, rushed back and tapped one of the six on the shoulder, for all that he knew, the very devil himself. This was the challenge. Instantly the rest, never ceasing their weave and stamp, opened out and left a space with the two dim figures, the challenger and the challenged, in the middle.

One could feel the tenseness of the moment.

Then it was observed for the first time that the Juruparí man carried, in addition to his horn, a long whip. A terrible thing made of some kind of a vine with a tapering lash like a coach-whip.

Without more ado, the challenger lifted his arms above his head and stood so, naked and unprotected. The Juruparí man took aim with his whip, measuring the stroke and the distance to the man's naked waist—and, with all his strength—Swish!

Even in the dark, for this was near to me, I could see the immediate welt where the lash curled about the man's body. But never a groan. Never a wince from the still figure.

Instantly the booming horns crashed out with a renewed vigor. The man had passed. The devil himself had tried to wrest a sign of pain from him and had failed. In the dark around me I could hear murmurs of approbation.

Immediately followed the most extraordinary change-about. The devil, having failed to break his man, must now take his turn. Without a word he handed the terrible whip to the man and in turn lifted his arms. Whereupon the man braced his feet apart and took a careful measure—and he surely tried his utmost to wring a groan from the devil.

Truly an extraordinary ordeal, and the weirdest of all sights that I have seen. All happened in a few seconds. And then, before one was well aware of what had passed, out of the darkness where another warrior took the ordeal of his courage, came another swish! And presently another; and another.

And so on, far into the night. Ever the booming rhythm of the Juruparí horns, and ever and anon the terrible swish of the whips. Consider, senhor, what a test of courage that was for an Indian who believed implicitly in his personal devil, to say nothing of the mere physical courage which faced the lash without a groan.

Even I, who only watched, was cold in the night and hot by turns. Just how I felt, I can not say. Only this I know. At no time did I feel that the caapi that I had drunk had inspired me with courage sufficient to rush in and face that ordeal.

As for my young man who was mad with the rest of those naked Indians, he was lost. In the darkness I could not see whether he remained among the dancers; far less whether he had found the courage to face the ordeal.

The uncanny night wore on. Presently all the young men who still danced had taken the test. Some of them, out of sheer bravado, twice or even three times. Presently again one was aware that the Juruparí men had disappeared the way they had come; without warning, taking their terrible whips and their more terrible horns. The incessant booming began to die away in the jungle. And then the dark figures amidst the firelight, dancer and watchers, began to realize that it was a very sore and a weary tribe.

In twos and threes they dropped off and stumbled toward the molocas; and presently I was left standing alone in the dark, tingling yet and drunk with the accursed beat that still pulsed in my blood, and looking for devils. I made haste to reach the shelter of my batelão.Of my young friend I knew nothing—and did not care.

BY morning, of course, I was sane once more, and I went up into the village to learn what I might learn. Men and women walked about with hollow eyes, sober of mien, yet with expressions of exhilaration. It had been a great triumph. Eighty-seven warriors had taken the ordeal and not one had flinched. The Juruparí who oppressed them had been very thoroughly shown that he could not cow that village, and he might as well leave them alone.

A young man came out of a moloca and stood in the doorway and stretched and rubbed the weariness from his eyes. I could see in the daylight two great welts reaching round his waistline and half around again. Yet he laughed out at the good sunshine as he stretched.

And then the wonder of a certain phase of this thing came over me. Consider senhor.

Eighty-seven warriors there were, and only six Juruparí men. Of the eighty-seven, each had received a lash, or more—and had returned it to one of the six! Consider, then, the condition of those six who had ambition to graduate to be witchdoctors. Surely is some magic known to those people.

But I had no time to speculate on magic. I was looking for my crazy young man. And in the course of time I found him. In a moloca he was, huddled amidst a pile of paint-begrimed and weary young men, who yet jested with one another as they rubbed the sleep from their eyes. And round his waist was a welt as thick as my thumb, the mark of the Juruparí to attest his courage.

I took him away down to the batelão and fed him and doctored him and put him once more to sleep, where he stayed till the next day. When he was washed of his paint and dressed and changed to a white man once more, I said to him:

"Amigo, come away with me home. You have no need of the caapi to give you courage."

But he, feeling tenderly his waist, grinned painfully and said—

"No, without the caapi I would never have done it."

"Rubbish!" said I with anger. "Hear while I tell you about yourself, my friend. As for those Indians, they believe that the caapi will give them courage, as also their fathers and their grandfathers have believed. They become drunk with the ceremony of the preparation and with the magic of rhythm; and so they face their fear of their devil who is more terrible to them than the whip.

"And as for you. While you, too, were drunk with rhythm and with magic, you have faced your fear and taken the supreme test of the whip, which to us white men is much more terrible than the devil. Which is no more than I have expected of you all along as we came to each lesser test during our travel. For you have shown throughout that you need only confidence to face your fear and to follow example, reasoning that what another man may do without cringing you may do also."

"Yes," he interrupted me quickly, "that's just it. But will I face my fear alone? That is a very different thing; and that is what I must find out. No, I must have my caapi which I have earned, and I must yet make my journey into the Rio Branco alone."

Que caralhos! What use to argue with youth which is set in its belief? And what need to weary the senhor with a profitless tale? The boy got his caapi, an acrid smelling powder which was to be brewed and drunk at need; and we bade farewell with interchange of gifts to those unapproachable Indians who had become our friends; and journeyed downriver in our new batelão.

Back and forth we argued the matter of his fear for many weeks as we traveled. But what use? He was insistent that he make his journey alone up the Rio Branco—where I told him I would have accompanied him for friendship's sake—and he could keep all the accursed diamonds that he might find. But he only laughed and insisted ever upon his need for going alone.

So at the inflow of the Branco we parted in anger. I indignant that he should desert me after all my trouble; and he sorrowfully insistent, yet promising to keep in touch. So I gave him the batelão and hoped that he might go to the —— in it, and so came on down to Manaos.

AND in the course of time there came to me, passed by one trader to another, a package. Small and not heavy. And I said to myself—

"Dientro, has the boy had such luck already?"

And I locked it away with care. And presently there came again another package; and another. And I cursed myself for a fool for not having insisted on going up with him to hunt at least for what I might find.

Five packages came in all. And then suddenly one day the youth himself. Brown, almost, as myself; and as hard of limb as of feature. The body and the face of a whole man.

And he fell upon me and embraced me and called me his very good friend and mentor who had taught him the most valuable lesson of his life—that fear was a most useless thing, having no value either to diminish or to remove a danger.

And I said to him—

"Rubbish. A naked Indian taught you that."

And he laughed aloud and shook my hand over and over again and said—true, that was so; but that I had taught him, oh, all the virtues of the world. For the boy was very pleased with himself. So I, to complete his happiness, produced his packages and delivered them to him safe and sound. But he demanded with astonishment—

"What? Didn't you open them?"

Whereat I was offended again and told him stiffly that Theophilo Da Costa was not known to be a pryer into other people's affairs. But he laughed most uproariously again and smote me on the back and opened up the packages before me. And what do you think they contained?

Caapi! Five equal portions.

After much more senseless laughter of youth at my astonishment he condescended to explain.

"I apportioned it out to cover the time," he said. "So much for each month, to use it as I might need. And as I found that I was able to travel alone—and to meet Indians who were not so good and traders who were worse—I sent each monthly allowance down to you to show you that I hadn't forgotten my lessons."

"Graça me Deus!" I exclaimed. "And were there, then, no diamonds?"

It was he now who was astonished.

"Diamonds?" he said. "Never heard of any. I went up because it was a mean country and I just had to feel confident that I could meet it."

"And the woman?" I asked. "Was there no young woman who made a fool out of you and sent you away?"

"Young woman who made a fool out of me?" he shouted. "Dozens of 'em, thank —— and young men, too. Till my life was miserable. But I'll show 'em now, by golly."

And I, looking at him, said to myself—

"Caralhos, it is my opinion that this savage will show those one-time friends of his many surprising things."

JUDGE then, Senhor Scientifico, for yourself, you who understand such things. Whether courage is a thing which can be drunk out of a medicine; or whether, as that old witch-doctor told me, it is a thing which one has from his father and his mother; and which, owing to his upbringing, can be hidden for a time for lack of opportunity to bring it forth, and of confidence to know that it is there?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.