RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

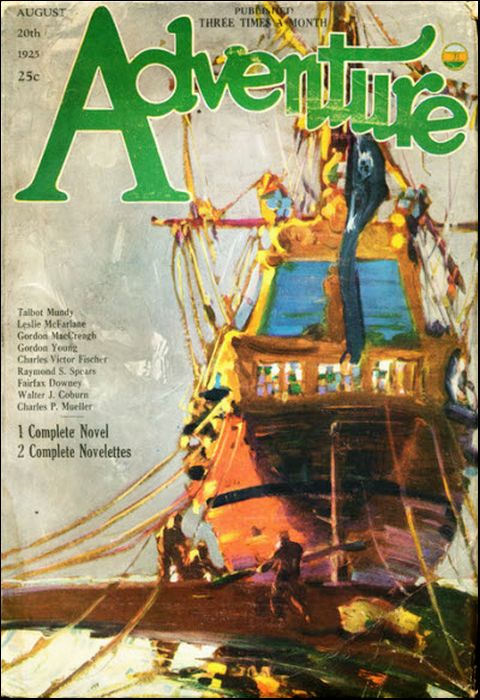

Adventure, 20 August 1925, with "The Jest Of The Jungle"

THE senhores are in search of a river-man and have been recommended to me? Bom, it is well; for I am above all things a man of the upper rivers.

Do I know the river Uaupes as far up as Brazil touches on the borders of Colombia? Dientro, have the senhores not been told that I am Theophilo da Costa?

Would I be willing to take the senhores so far? Umm-mm, at a price I would—but wait I was going to say that for a proper price I would take the senhores into any part of all Amazonas—even into the country of the Jivero head-shrinkers, if their desire and their foolishness went so far. But I lay a check on my hasty words and add a condition. It is: I will do so if I am satisfied as to the reason for the desire.

Your desire is to take a vengeance for the killing of Billee the gringo? Ha, that was boldly spoken. But—you will pardon—it is my observation that it is not usual for senhores from America of the North to make so arduous a travel for the sake of a little feud. A travel that will not be so comfortable, I can tell you, as sitting on the deck of this great hundred and fifty-foot steamer of the Companhja Navigazione and drinking the cool water of the pupunha fruit.

You desire also, having taken that vengeance, to secure the green stones for the sake of which Billee was killed?

Oho, that is different again. The little green stones! Ho ho, the jest of the jungle! It has drawn you into its net now, yes? Truly, a wide-flung net is that jest. A merry jest for half the nations of the earth! Listen to the procession of them.

First there was the German, the scientifico who discovered the joke. Then Billee the gringo. Then the two robbers, the Americana and the Swede who followed Billee. Then the gang of our Brazilian cutthroats with the Frenchman and the Spanish half-breed who followed those two. And now the senhores.

And which of all of them ever came back?

Senhores, the jungle is no place for men who do not know the ways of the jungle—even though green stones be many. And who knows the truth about the little green stones? My advice to you, er—tenderfeet, as you call it, no?—is to put out of your minds the hunting for the little green stones. And as for the vengeance—that is another matter. But since you are Americanos of the North and foolhardiness is born to you, even as it was to that Billee, I will not waste my advice born out of my experience. And since you are kin to Billee, I will even tell you the truth about the matter. For Billee I have counted to be my friend; and if any man know the whole truth about this jest, it is I, Theophilo da Costa; for I have been in the net since its first weaving. Look you, I will even show you the first of those evil stones, the earliest snarl of that twisted jest.

Wait but till I loosen this money belt and—Ah, so is better. I breathe more freely. I put on weight, senhores, idling here in Manaos between trips. But a week among the rapids of the Gabriel and a day or two of the malaria will put me in condition again.

Look, a wonderful pebble, no? Large as a turtle's egg, and of a perfect green, without flaw. A stone of quality. Two hundred and thirty-five carats at least; and it will cut to close to a hundred. A stone that would buy a governorship of a state.

The senhor is not impressed? Oho, you know something of stones then? You think—You are afraid that—You regret to say—

Ha ha! Say it, senhor. Have no compunction. For I have known it myself these six months and more. A piece of a bottle glass, no? The joke, as you say, was on me.

Ho ho, and what a joke! A joke, truly, of the jungle's best But I was not the only fool. For look you, by reason of that joke eleven men lie dead. Eleven, and who knows how many Indians? And there will be more. For those Desana of the upper Uaupes do not forgive killings. I tell you, senhores, I who know those people, there will surely be more—though the green stone be but a piece of a bottle carefully rubbed down on a rock and chipped at the corner to show color. Truly one of the grimmest of the jokes of the jungle,

And yet, senhores, I who have been watching this thing from the very beginning, have a belief that this is not such a very great joke on me after all; for I am at least alive. And it is my observation that, just as some men are born blessed in the cities for a bustling life in the city, and some are born in the country for a peaceful life in the fields; so are a few men born with a curse that destines them for the jungle; and to the jungle they must go.

Them the jungle tries out on its steaming cauldron of hell, and of those few, it kills the most, as unfitted. But the very few, those in whose blood it is to love its very wildness and its loneliness and its ferocity, it takes to its bosom as would a wolf mother; testing them every now and then to make sure that they are still worthy, but permitting them to survive.

And look you, I have been a man of the upper rivers for twenty years, and I nave been through this latest most elaborate trial of the jest And I live—though eleven men lie dead. And there will be more, I tell you; there will surely be more. For others will surely go up on the false trail of the green stones, not knowing the ways of the jungle.

WITH the German it began. The scientifico who hunted after roots and herbs. He came in, loaded down with tin boxes and presses and blotting papers, prepared for a two years' stay among the unknown plants of the foot-hills. And within four months he went out again, hurrying in a great excitement, loaded down with the weight of some tremendous secret. He reached as far as Belem, three thousand miles from our jungles and almost to safety. And then the jungle smiled the first slow, cold smile of this jest and reached out its long arm and caught him with something or other that he had contracted while within its depths; and he died.

The tale came up to me in due course, for it is my business to keep track of those who go out carrying secrets from my country of the upper rivers..

Shortly came Billee the gringo, all pink and new and young and full of enthusiasm, knowing nothing at all and displaying a child's trust of all men in his big, clear eyes, and having no secret of any sort.

He came to look for emeralds, he told all and sundry with a delightful frankness, and he sought information and advice. All Manaos smiled at the innocence of the youth. As though anybody who knew anything at all about emeralds would tell it to the first naive stranger.

So presently, since all those who want to travel the far reaches of our upper rivers come eventually to Theophilo, this Billee came also to me. And he stood with his legs wide apart and his hands deep in the pockets of his breeches, and demandwl of me with his engaging cheerfulness—for all the world as though he were asking to be advised on a little tour of the city—that I direct him to the good God knew where between the border of Brazil and Colombia to hunt for emeralds.

But what need to explain this so ingenuous youth? The senhores know, of course, how Billee looked and spoke. Fresh from the nursery almost. So I said to him to dissuade him:

"Amigo, do you know what you ask? Consider this travel to the further Uaupes. The steamer will take you to Santa Isabel; seven days—or ten or maybe fifteen—depending upon the rain and the current, which no man knows. From there on is our country of the upper rivers. Jungle conditions hold and civilization is left behind. One goes by batelão, big dug-out canoes with an added freeboard of a pair of ax-hewn planks on either side. Six paddles to the canoe and a thousand pounds of trade goods. Comfort has ceased. From dawn to dark is the rule of the river. One eats as one goes and one sleeps in the wet bottom of a canoe.

"Yet there is no hardship of travel for some ten days till one comes to the caxoeiras, the rapids. São Gabriel the first. Forty miles of bad water, where one progresses by sending an Indian to crawl from tree to overhanging tree with a long rope which he makes fast to a limb, and then all haul up together on the rope. After the Gabriel is peace for some fifteen days; except that at the mouth of the Uaupes, which comes in at the right bank, one enters a belt of piume flies which lasts four days. Then peace again for three days. Then another accursed belt of insects for seven more days. Then the caxoeira of Ipanoré, where all baggage must be taken out of the canoe and carried past the bad water over a trail, and the empty boat then be hauled up by rope and push and sheer sweating muscle against the current and over the rocks. Men have been known to slip on those slippery rocks and be snatched away in an instant by the devils of the whirlpools or be smashed by the plunge of the heavy canoe.

"If one passes the Ipanoré in safety, comes in five more days the caxoeira Jauareté; and after that a caxoeira, or two or three, every day or so. What matter their names? But there are some nineteen or twenty, till one reaches the country which may, or may not, be the border between Brazil and Colombia.

"A long and a bad travel, my young senhor. One which is made with difficulty and danger even by experienced men who know the upper rivers. And you, who are not a river-man, nor even a geologist, would go careering up in those jungles, hoping to find ground wherein grow emeralds. Senhor, this is not the talk of a sane man."

But this Billee had a confidence as great as his innocence; and he said with a sturdy insistence that he was not so crazy as he might seem; that he had a map—as though that were the final surety.

Whereat I could do no other than laugh out loud. For, let me tell you, senhores, there is a traffic in maps of treasure said to be hidden in this place and in that place. Treasure there is in this vast Amazonas of ours. Treasure in breath-snatching quantities; and men but begin to know what the river fringes of our jungles hide. But certain astute rogues, who learned during the wild rubber days that gringos are credulous, take advantage of that very fact to prepare maps of the most circumstantial character upon paper taken from the walls of our old buildings, and then set out to ensnare gringos who are young and unwary, as was this Billee.

All of which I told him. But he had all the courage of his youth; and he insisted doggedly that his mind was made up to go. Even though his map might be false, he must learn to stand upon his own feet. And he laughed at the adventure of the thing, and spread his big loose shoulders to sniff up great draughts of air through that upturned nose of his; and he said—as though such privation were no more than a joke—that he would at least know what roots and herbs might be eaten in the jungle; for while he was truly no geologist, his training had been as a botanist.

It was then that a glimpse of the light came to me. For I remembered that German who was also a plant hunter, and I remembered his excited hurry; and I saw here a connection between those two who labored together on so profitless a subject.

And thus it was that I, who considered myself wise in the ways of the jungle, was drawn craftily on to the stupendous joke which the jungle was preparing with men's lives as the laughing points. I, who had laughed carelessly with the other river men at the temerity of that German scientifico who had thought to wrest a treasure from our jungles. For, seeing the connection, I said:

"Oho, this is different. The trail begins now to smell of meat."

And I asked Billee to tell me more of his map. And he, poor fool, immediately produced it and showed it to me, laying bare at one stroke all his knowledge for any experienced man to seize and make use of.

"Put it away, most simple one," I told him. "And let no man ever know that you possess such a thing; for it may be that it has value."

And when he did so, wondering and with a hurt look in his eyes, I told him that I myself had no time just then to go paddling off after every such breath of a rumored treasure that came with the down-river winds; but that if he insisted on making the venture and going off on this wild hunt after treasure I would find for him the necessary outfit. So he laughed again with the carelessness of a boy who goes off to hunt wild pig of an afternoon and said that, treasure or no treasure, he would at least have the joy of the venture, and that the assistance I offered would be as a gift from God, for then he was sure he would succeed; and he shook hands with me with enthusiasm and said that we should be partners.

Truly that was a youth with a charm as great as his folly—which was very great. But my heart went out to him. So I made out for him an order on the house of Araujo Companha for stores and trade goods such as he would need; and I found for him a canoe and a good crew and a capitan for the crew. An up-river Indian who came down now and then with cloaks of parrot feathers for the carnival dancers. Small and wizend like a makako monkey he was, and he lived with his people like monkeys on platforms in the trees above the flood water of the Uaupes, and all Manaos knew him as a great rogue and a clever thief. But he was a cunning and clever canoe man. So I said to him:

"Pacheco, I know you for a great scoundrel and a shrewd jungle man. And you, Pacheco mio, know me. So I deliver this babe into your hands to take him where he will. See that he comes back as nearly whole as possible."

And I paid him in advance. One rifle of Winchester with a hundred cartridges—which was good pay; but I exacted much, from the man in giving this great infant into his care. Besides, I am one who has always had a preference for gambling on a business deal with a man whose face I like, rather than with one who comes with a wallet full of slimy references. And the face of this Billee was a good face. Young, of course, and empty of experience; but, as we river men say, there was rock beneath the mud. I am one also who believes in luck; and who could tell but that this one might meet with the luck that so often comes to the foolish?

So Pacheco took him in his charge and they went off up river and were swallowed up in the silence of the jungle; and I heard no further word for a space.

THEN in the course of time there came down from the Rio Uaupes those two others of whom the senhores have heard tell as the killers—but this jest is by no means so simple as a mere killing; but is as twisted as the Rio Uaupes itself. These two were the Americano and the Swede, who were the next two selected by the jungle for the furtherance of its great practical joke. They had been away on some business of their own—experimenting with palm oil nuts, they said—and they made a loud talk in the Praça da Cathedral, displaying the bottle glass and proclaiming to the world that they and their countryman, Billee, had found the place of the green stones, and that they came now to raise money for the purpose of continuing operations.

And all Manaos gathered with goggling eyes to look at the green glass, and spat with disgust and said:

"Qué fortuna dum louco! What luck of a fool! To think that that swaddling child should have had a true direction; and we—may the archangels spit upon us—we but laughed at him."

But I said to myself again—"Oho, the trail smells not so good." For I judged this Billee by the open face of him to be no man to make a partnership with one who outfitted him in Manaos, and later to pick up with two others in the jungle, countryman or no countryman. So I sought out the two in the Botequim dos Estrangeiros where they drank the noon hours through, and ordered three bottles of guaraná with rum in it and engaged them in conversation.

Yes, they said, Billee was their good friend and compatriot—from the very same state as the Americano, attaching some sort of virtue to that fact. And Billee had had a map of the place of the green stones; but being green himself, had not known how to get to it. So they had joined their experience to his information and had made a partnership; and here was the sample of the first finding, and all they needed now was money to continue the operations and they would return immediately to their good friend Billee who had remained behind to guard the camp.

A good story and circumstantially rendered. I did not ask them why they did not register the claim under the mining law and so protect themselves; for our mining laws in Brazil are not so well established as are yours of America of the North. And of what use are mining laws in the upper rivers where there is no law?

So I gave them congratulations; and, thinking myself cunning, fell into the net which the jungle had spread for me while it chuckled at my foolishness for thinking that I knew its ways. Though I am one of those selected children of the jungle whom it permits to survive, it blinded me with the blindness of a fool who is wise in his own estimation; and I bought the fragment of a beer bottle for a conto and a half of mUreis—which they swore was but a tenth of what such a stone was worth—from these two scoundrels who were already marked for death. Yet they accepted the money with an alacrity which should have made me suspicious. But, as I have said, when the jungle prepares one of its elaborate frauds, its children have the wits of children.

So they purchased food and equipment and trade goods enough for a whole exploration and celebrated their good fortune after the manner of the senhore's country, by remaining very drunk for three days. And then they went off up river again.

But even in my folly I was not altogether a fool. For that long Americano and that heavy Swede had not hoodwinked me one bit beyond the matter of the bottle glass; and my judgment of Billee remained as that of a man of honor—even though he did come from the same state as that other.

So I called an Indian of the São Gabriel named João, who was a convert to the mission; but for all that a keen jungle man and one to be trusted. And I told him to take a light dug-out and two men and to follow the trail of those two to their place, and to tell Pacheco to send me word of the happenings in the upper Uaupes country.

Within the hour he went, in a light uba which could skim along under the shadow of the overhanging branches of the shore and keep a sharp watch on a heavily loaded flotilla like the others.

And in the course of some three or four months he came back and reported that he had followed the pair for forty-three days by sight till he had lost them among the many channels of the Umarituba shallows, and had then followed for twelve days more by questioning among river Indians. Which was almost as good as following by sight; for nothing happens in the upper rivers which the Indians of those rivers do not know; and what they see they remember in every detail, for their minds have never been trained to write a thing down for record and then forget it.

So he traced those two all the way up to the Rio Kerary which comes in at the left bank of the Uaupes at the moloca of Yapu Ua, a Desana chief of some eighty fighting men. And at the Rio Kerary, João told me, those two had turned in and traveled for two days till they came to a place where there was a camp and a great digging in the clay bank of the river; and that there they had stopped and made camp again and let word be known among the molocas that they would pay two ounces of salt per day for men to work for them.

BUT of Billee and of Pacheco there was no sign in that place. So João, since he knew the Geral talk and the proper ceremonies for visiting in safety, went to the moloca of Yapu Ua to make further inquiry; and there he learnt from an Indian that another Indian had told him how he had secretly followed a canoe some months before in the hope of getting some loot by night, in which canoe was a white man with a crew of Indians. But that he had been foiled in his hope of loot by the alertness of the capitan of those Indians, who was as jungle-wise as the white man was simple. And how two other white men with a big canoe and a crew of downriver Indians had overtaken the other white man in camp; and how he, lying below them in his uba, had heard the sound of fighting with guns; and then the next morning the two white men had gone on alone in their canoe. Whereupon he gave up the following, being frightened, for these were bad men.

So do the rumors of the upper rivers travel down to the city; and that was the tale that came down of the lulling; and I remembered how Billee in his innocence had babbled of this Kerary river. So I went before the altar of São Sebastian in the cathedral and laid oath upon myself; for I said:

"Oho, the trail smells now very foul. A cleaning up must be done."

The senhores, who spoke of a vengeance, will understand. For this Billee was my partner after all—even though it had been no more than his spoken word. And if a man does not hold by his partner, with whom shall he hold? So I sent word up to Santa Isabel to make ready a batelão of my own which I kept hauled up there on the beach in the charge of a nut gatherer who was friendly to me; and I told him to summon certain Indians whom I named to him by name, a double crew and good fighters all; and to send them down to me swiftly. For the little stern-wheel steamer that makes the trip to Santa Isabel every month or so had just wheezed away on its hazardous journey, and it could not arrive there and return—even if there were no accidents— and then be ready to go up again in less than a month at best.

Not that there was a particular hurry; for a vengeance may well wait for a year or so and be none the worse for the keeping. Yet I said to myself that the secrets of the jungle, such as the place of the green stones, sometimes leak out, and it would be well to establish myself before, others should hear of it and I should have then to fight for my partnership inheritance. Also it happened that I could devote the time just then out of my own business to attend to this matter conveniently. So I made my plans leisurely with the thought that it would be no more than a justice to let those two labor a while to get out some of those stones, which would be blood money for masses for their own souls.

But first I paid to João, the convert, the reward which I had promised him; wherein I showed that I was still a fool. For João proceeded immediately to drink up the money, and babbled his tale in the market places; and the people nodded and said:

"Deus lhe benza. God rest his soul. That boy, with all his luck, was not one to find such a treasure in the upper jungles and keep it. It is clear now how those other two got his map and found the great green stone that they brought for sale.

But I was annoyed; for the jungle, anxious to play its jest out to the end, had let loose the scent before I was ready. And, believe me, senhores, this is one of the wizardries of the jungle. Comes a tale of a profit to be wrested out of its dark maw, and immediately fools who know nothing of its lurking dangers and its cunning pitfalls rush forth with insufficient preparations, or with no preparations at all, to win their fortunes in a day—and they pay with their lives the inexorable toll of the jungle. A whisper of a stolen treasure from the dim distances, and killers immediately scurry like rats fast upon the trail of killers.

Hardly had the drunkard's half-misunderstood talk gone forth, when there became apparent a great hurrying and. a whispering among certain of the hangers-on to no known business, who are always to be found round the tables of the botequims of the dock front. Salteadores all, scum which the tide of rubber, when it swiftly fell, left littering the water fronts of Manaos.

Great preparations were in hand with clumsy secrecy for the purchasing of boats and the hiring of paddle-men and the laying in of such goods as are needed for up-river trade. They would have kept their plans secret, those river rats. But if a secret can leak out of the jungle, where it is known to only a few, what chance has a secret of treasure along the Manaos water front? When the jungle plays, such, matters become fate.

All the most hidden rumors came to me; for I am one who believes that fate assisted by a little precaution is likely to be a good fate.

CHIEF among these expedicionistas was one Luis, whose wife kept a bawdy hotel for sailors, on the profits of which he flaunted, himself in the drinking shops under the title of Dom Luis Pereira. With him was a gathering of the nationalities, some nine or ten of them; men who had come to reap a fortune out of rubber when rubber was black gold; and when the price of rubber dropped to the price of black mud they had never been able to get money enough to get out and away. So they picked up a living in sundry shady ways along the water front and waited, hungry for just such a chance as this one.

"As the names came to me one by one I was disquieted; for my batelão had not yet arrived, and the preparations of these ruffians progressed apace. The most cut-throat crew of all Manaos water front was gathered for this treasure raid up the Rio Uaupes. My plan had been to carry out my feud at my leisure with those two who had gone before, and to establish myself on the digging which was mine by my partnership right with Billee, which I could then hold against all comers. But I could hardly hope to enter into a war of dislodgment against this fresh array of scoundrels; and it would be small comfort to me to reflect that they would probably wipe out my feud against those other two as soon as they arrived to take possession.

I found this João and took him by the throat.

"Sot," said I to him. "Renegade convert. Look now what you have done. There will be killings in the upper rivers; and upon your conscience they will lie and will cost you many penances at the hands of the good padre of the mission—to say nothing pf the fine which I will impose upon you and all your family to supply me with labor for the passing of the caxoeira of São Gabriel.

But he placed his face on the ground and covered his eyes—for these converts do not fight back when one beats them. And he wept for my forgiveness and offered amends.

"Look senhor," said he. "I will take my uba, and will go swiftly to warn him."

"To warn whom, fool?" I demanded. And he said:

"Senhor, it is in my mind that maybe Pacheco and that white man are not dead. For I will confess. I made strict inquiries of the Indians of Yapu Ua, knowing that they would surely visit that place of the killing; and I hoped—the senhor himself cannot blame me—I hoped to get for a small price maybe the rifle of the white man or pf Pacheco, since the Indians cannot use them, having no cartridges. But no man knew of any such loot."

I shook him by the throat so that his head rattled.

"Forty fools as well as a scoundrel," I said. "Do you think that those other two, the bad men, would have left any rifles lying about in the jungle?"

But he cried out that it was not so; sometimes in the confusion of a fight the Indians who were the servants of white men might pick up useful things, which they hid away; and though they might not be able to take them themselves, they sold them by description to other Indians who could go and find them. So he had hoped for a rifle perhaps. But no one of Yapu's men had heard of any trading in hidden loot with the down river Indians of those two bad men; and therefore it was in his mind that, though there might have been fighting, there was no killing, and that Billee and Pacheco had got away with all their property. Otherwise there would surely have been some small trifles out of their camp hidden away for later selling.

But to me that seemed to be a slim hope. For even if, through some providence of the good God, Billee might have escaped with his life, what chance would he have, new and inexperienced as he was, to survive the jungle; and even if that miracle should be, what chance would he have to defend his green stones from this new invasion of this cutthroat gang? None the less I beat João and told him that if it might be so, it was all the more reason for haste now; and that the most amends he could ever make would be to take his son, a sturdy canoe man, and race up river in his uba, traveling night and day, to tell my batelão men to travel down river likewise, or more so.

So he went. And I for my part saw to it that no time would be lost through any neglect of mine, once my batelão did arrive. And I made a diligent survey along the water front and in all the side creeks to ascertain what boats might be available in Manaos City for those filibusters. And as I inquired and inspected, I found myself beginning to be able to smile once more.

For you must know, senhores, that not every boat is fitted to travel the caxoeiras, as also not every man is fitted to go up into the upper rivers. Of craft, ships' boats were available in plenty in the city; keel boats with plank bottoms which would open out like the fingers of a hand upon being dragged bodily over the rocks. But not a single batelão with a solid bottom hewn out of a tree trunk. I could give to any one of those boats a month's start and would arrive the first at the Kerary.

IT is in such little matters that the jungle favors its children who know the needs of the jungle. So I felt in a mood to make a jest of all these preparations. I met this Dom Luis and said to him:

"Hola, como va'e? I hear you are going on a big expedition up river."

For a moment he was taken aback; and then his little black eyes glowed like a peccary's, and he made as though to reach for his boot, where he carried the stiletto engraved braggingly with the warning—"Não me ameaça. Don't cross me."

Myself, I have never held with all these fancy ways of carrying a knife, such as in the boot or in the sleeve, concealed in order to enhance the surprise when produced. They serve to amuse boys and the theatrically minded. In full view in the sash is my habit, as the senhores may see; and I claim that a view of a well-used knife is in most cases as good as its use.

As it was with this Dom Luis. He dropped his raised foot to the ground and stuttered his anger, champing with his teeth just as do the peccary boars before rushing at a hunter.

"How—how do you know that I go up-river?" he demanded fiercely. For he thought that his secret was well kept among the gang that he had gathered.

"Aha," I told him, not without malice. "We of the upper rivers know all about everything that is coming to us."

"Ouve lhe." He sneered back. "Listen at the man. Então, if you know so much, what do you know about my plans?"

"That the talk is that you make preparation to go up the Rio Negro into Venezuela and through the Casiquiari to the Rio Orinoco for the purpose of collecting egret plumes," I said without hesitation. Whereat he grinned and nodded with sudden friendliness. Till I smiled and added—

"And yet I, who have an urgent business of a little feud in the upper Uaupes, have been planning to pass you on the way."

With which I laid my hand upon my knife hilt, for I knew that his rage would be savage and without reason, as is the peccary boar's. So also it was. For he, though he knew that I might easily disembowel him while he reached for his boot, none the less did so, squealing his fury, and charged at me as though he were a whole herd. -

As for me, this pleasant boar-baiting had gone farther than I had intended. I had my urgent business of the two white men whose time had come to die on the Kerary, and I could afford no leisure to defend a brawling case in the law courts of Manaos. So I take no shame to myself that I tripped him with my foot as he charged blindly, and I ran away laughing.

After that, Dom Luis made much boasting of what he would do to me when next we met, and cried aloud in all the rum shops that he was looking for me. But under cover of his outcry he was very cunning. He put speed to his preparations for departure and worked with more silence than I gave him credit for. So that he actually threw dust in my eyes and got away with his gang before I knew of it.

For what play I gave him honor and took a black piece for myself. But I was not disquieted. I knew his two boats, and I knew by one means or other all about every man in his crews. The boats were heavy and wide, having room indeed for much freight; but slow. And while, with extreme care, the passage of the caxoeiras might be made in them, much time would surely be lost by reason of the keel seams requiring to be frequently caulked. Nor were the men any collection to worry about. Dock sweepings and mangrove creek Indians all, chosen for their cutthroat appearance rather than for their skill at the paddle.

That gang would not be difficult to outstrip in the race; and for that small benefit I was duly thankful. I would have time to cope with the two brigands who were already there at the Kerary, and could then make whatever arrangements I might to defend myself against this rapscallion crew who would shortly arrive. Just what I could do was not clear in my mind. But something surely would present itself when I was once on the spot, and anxiety about it now would not help the situation.

So, while I waited for my batelão, I busied myself with the laying in and packing of provisions and trade goods for a swift getaway and a long and hard travel; and I found time also to visit my good friend, the Padre Ferenz, and receive a blessing upon my urgent business.

So it happened that when four days later my batelão came I was all ready to load and start away on my journey to find out the last truth about Billee, and to find particularly those two who said that they were partners of Billee. I had to laugh when I say that my Indians, who knew my ways, had built a palm-leaf shelter over the after end of the batelão into which a man might crawl out of the sun. The leader of them, a good lad named Ochkochthithero, for he swam like a manatee, looked at me and grinned.

"For the pirarucú," he said.

I commenced to tell them sternly that there would be no pirarucú this voyage; that the river custom was to feed the crews mandioca and no more. But who can deny the nearness of that sun-dried fish without salt when it lies in bales and festers on the dock?

And indeed it is my custom to give each man each day a ration of this frightful fodder; as well as—on special days when they have worked hard—a tot of caxirí, which is a white cane rum of excoriating strength.

Other men of the rivers grumble at me and tell me that I pamper my crews and cause discontent amongst theirs. But who gets the most work out of his men? I ask them. Who can rely upon his crew to fight for him when need arises? Who travels five days, to the other's six? I tell you, senhores, that this little extra expense in feeding is amply repaid in good will and hard work—though, after all, it is my right; for a man who is willing to crouch under a palm leaf shelter in a canoe in company with half-dried pirá is deserving of much loyalty.

So it happened that within two hours of arriving my batelão was swinging up river again to the beat of six paddles against its sides and the hum of the men as they chanted their interminable mm-hmmmhm-mma, to give rhythm to their strokes.

Of the journey there is nothing to tell. Canoe travel is of all joumeyings the most tedious. One sits on a bale of stinking fish till the cramp of one's limbs forces one to change one's position and sit on another bale. One eats and one sleeps and nothing ever happens. Only the Tndians ply the paddles with endless monotony; and when they rest, the relays edge into their places and take the paddle without losing a stroke. And one broils in the heat and sleeps once more, and wakes and rubs the cramp from one's limbs and wishes that one might at least reach a caxoeira where there would be strenuous work for all to stretch the benumbed muscles. Yes, there are more exciting things than canoe travel on the upper rivers.

SANTA ISABEL I made in nine days, which is a run which the steamer itself would not be ashamed of. There they said that nothing had been seen of Dom Luis and his gang; that we had surely passed them among the maze of islands; or that they had taken the other bank, which even at that point of the great black river was below the horizon. But I gave that Luis credit for a man of some force of personality, and I deluded myself with no false hopes. The only hope which I allowed myself to think on was that there might have been something in that João's conjecture and that perhaps Billee had escaped with his life. So I pushed on without wasting an hour; for none knew better than I how urgent would be his need for assistance in these upper jungles, with white men as well as Indians hostile to him.

So, four days later, in the back-water below the race of O Forno, where the demon of the rapids keeps all his victims, we saw the bones of a new boat, broad and heavy, which had been capable of carrying much freight

"The hand of the jungle!" said I to myself; and I laughed. Not that I thought that Dom Luis, or any of his gang might have gone with the boat. By no means. None of that town-bred gang, I well knew, would remain in a boat to make that passage. They would walk the trail, of that I was sure. But I laughed to think of the discomfort and the cramps of of that crew crowded now into the one boat in addition to such cargo as they might have saved.

But my Indians laughed not at all They pointed to the newest victim and murmured to one another; and they must needs all go ashore and make each man an offering of his full day's ration of pirá placed upon a table formed of a stone balanced upon two others. The while I fretted with impatience. But I knew that it was poor policy to interfere too much with the superstitions of Indians, and water men at that.

So, having appeased the demon, we traversed O Forno and the rest of the São Gabriel bad water without mishap. And a day later we swung out of the black water of the Rio Negro into the white water and the piume flies of the Uaupes. And three days later again, what should we see ahead of us but a great splashing of badly handled paddles which almost hid in the spray a big new boat loaded down to the gunwale edge with goods and men.

In another hour we overtook it with ease, my Indians swinging their paddles like one man and jeering a fresh insult to the others with each stroke.

Then at last I breathed freely and made reservation with myself to remember the good Padre Ferenz for his blessing. For the race, at least, was won; and that is more than a little, let me tell you, when one races against the misfortunes of our rivers, however great his experience. What the jungles of the Rio Kerary would bring forth in the near future, the jungle would decide. For the present I was well pleased. So, though the river was wide enough to pass well out of gun-shot, I could not resist to myself the pleasant game of edging close and calling across the water:

"Ohé, Dom Luis. You have lost your way. You must turn back to the joining of the waters and follow the black water North to the Casiquiari. Can you not see by all the signs that you travel in white water and westward?"

His only answer was to shake his fist and to shout the word which amongst us Brazilians means a killing.

It was an easy shot where he stood in the prow of his boat outlined dark against the sun on the water. But I shrugged.

"Or is it," I taunted him again, "since many names are similar in the upper rivers, that you meant, instead of Casiquiari the Cascaiary, as an upper branch of this Uaupes is called?"

"Yes yes, that is so. Caiary we are bound for," cried a dull-witted one of his gang who thought to cover their plan with this cleverness. But Luis cursed him for a fool; and, drawing the knife from his boot, made the sign of the cutthroat in the air.

"You think you are very clever, you Theophilo," he shouted. "You and all the rest of you up-river men. But I tell yon that you can t keep to yourselves everything from us who come from below. What matter that you have the faster boat? In time we, too, will arrive at the Kerary; and then we shall see who shall find and who shall take."

I made a trumpet out of my hands and shouted back a farewell at him.

"Good," I called. "I shall tell the jungle chiefs of your coming with much loot."

Leaving which little thorn for him to reflect upon, we drew out of range. Only I shook my shoulders and threw back my head that he might see me laugh. For though I, Theophilo da Costa, do not fight against white men by stirring up the jungle Indians, it would do that gross fellow no harm to reflect that just a word to the Desana people, who use the poison blow gun, telling them that those who came after me were no friends of mine, would inaugurate a relentless stalking of them by day and nigh t by invisible devils who would shoot swift death out of soundless tubes.

Three hours later they were out of sight After which there was no pleasing relaxation any more to break the monotony, except the long string of caxoeiras which began at the Ipanoré, and the thought of my vengeance on the account of Billee, and the making of plans to hold my inheritance of the green stone digging against those robbers who followed with the treasure lust in their hearts—which treasure lust is but another word for the killing lust

In due course then, after much hard work, I arrived at the Rio Kerary and proceeded up that river two days to the camp of the white man whom I had come so far to make a reckoning with. But I left my boat at a bend of the river and crept through the jungle to investigate; for I was not minded to come without precaution upon men who gambled with life for the sake of the little green stones.

I FOUND them, of course, without difficulty—and found with them my first surprise. The camp was at the edge of the river, where an ugly gash stood out yellow in the sun against the hot green of the jungle. A muddy stream, diverted in a little canal from higher up, flowed through the mess of bare clay and general rubble and polluted the stream below.

A common enough wash ground of prospectors. But the surprise, immediately ominous of death, was that Indians, standing as outposts, watched the camp from all sides. Men of the Desana they were, who lolled in clear enjoyment of an easy labor in which they were not interested, except for the pay that they earned thereby. But within the half ring of outposts stretching from river bank to river bank were the white men and those down-river Indians whom they had brought with them; and their appearance was the very opposite of the easy enjoyment of the sentries. Nervous they were, all of them, and ill at ease, looking ever over their shoulders as men who feared- some menace; and it was clear that the white men in turn stood guard over their workmen, who would otherwise surely have run away.

Here seemed to be no camp to be afraid of. So I slipped easily between two of the dozing sentries and stood suddenly confronting those two white men whom I had come to kill—and my surprise was immediately redoubled.

For after their first surprise at my presence, they, who should have had an evil conscience, were filled with joy to see me.

"Amigo," they hailed me, and, "deliverer." And they all but clung to me as would people from whose minds a great weight had been lifted.

"'Now will everything be all right," they said. "For you have influence, Theophilo, and if you but give the word to the chiefs. they will call those devils off."

"What devils?" I demanded with suspicion.

"We do not know," they said. "But we are hunted by night and by day. Shot at from all sides with rifles. We have sent presents to Yapu Ua, the chief of the moloca at the mouth of the river; but he disclaims responsibility among his men. Yet this is Desana country, and what other wild men are there?"

A tale astonishing enough. But I was not to be diverted so easily from the reason of my long journeying. I remained aloof and stern.

"Before there is talk of friendship and deliverance," I said "I have a question which I have made a long journey to demand of you two. What of Billee the gringo?" And I held my rifle muzzle low as I spoke.

Neither the Americano nor the Swede was a man to be easily browbeaten. Swindlers they were and men of little principle, but either could well take care of himself—in any ordinary circumstances. But just now they were in a condition of shattered nerves by reason of the harrying of which they spoke. As we who know the jungles know there is no fear that grips lonely men so completely as the constant expectation of an unseen death sneaking in out of the dim silences. So they, instead of showing fight, lied easily without turning a hair.

"Oh Billee," they said, and they made light of it. "We had a disagreement with Billee and we parted company."

"Oho," said I. "A disagreement, you call it? A disagreement arising suddenly upon the first meeting and entailing the shooting of guns and the complete disappearance of Billee and his crew."

At that they glanced at one another and the fight came into their eyes. But I held my rifle very ready. So they lied again. Yet seeing that I knew so much already they admitted the half.

"True, there was fighting," they said. "But no killing. Billee went safe."

Now senhores, I am one of those who lives in the upper rivers, and in our lives there is little room for sentiment. Yet my heart told me to believe this miracle. Though my mind remained full of suspicion and cast back swiftly on the probabilities and possibilities of the matter.

That Billee, new and full of inexperience, might have escaped with his life out of a fight with these two hard men was miracle enough. Yet what João, the convert, had told me flashed back into my memory. My heart took hold on this and kept singing that there was room for hope. And my mind took hold on the forlorn hope and told me that I had seen the jungle perform its miracle upon men before now. I had seen it take one of those whom, it selected for its own children and, instead of killing him offhand, nurture him and bring out all the man that there was in him. And thinking on all this, I said to myself:

"That boy, after all, was strong and alert, in spite of his babe-like confidence; and his eyes were jaguar eyes, without fear; else he never could have laughed so cheerfully when he came away to plunge into the wilderness. And he had Pacheco—wise old scamp Pacheco—to teach him the lore of the jungle."

So I postponed the killing of those two whom I held at my rifle muzzle and said to them:—

"Now listen carefully, you bandidos. You know that I, Theophilo da Costa, do not travel the rivers without Indians who can use the rifle as well as the paddle. Remember then that these Indians surround your camp with finger upon the trigger. So tell me certain things without trying any tricks."

This matter of my men surrounding the camp was, of course, what you Americanos call bluff. Yet in the present condition of the nerves of those two it was good enough to insure their good behavior. So I asked them first:—

"This, then, is the digging which you made in partnership with Billee?"

They said it was so.

"Oho," I said, "and it was here that you found the great stone that you sold me?"

"Exactly so," said they.

"Show me, then, some others of your finding," I demanded swiftly.

At which their faces fell, and—

"We have had bum luck," they grumbled. "We have found no others."

"Oho," said I again.

And it was then that I determined to show my stone to a lapidary immediately upon my return to Manaos, and cursed myself for a simple fool for not having done so in the first instance. But an idea which was growing in my mind about green stones grew stronger, and I smiled to myself. But to them I said:

"That was luck in keeping with other that is coming to you. Listen now, you two so clever liars—and remember my Indians who watch your every move from beyond the line of your foolish sentries. Listen, and I will tell you some of the truth which you are hiding. This is what you did:

"You followed fast after this so foolish Billeee and you came upon him in his camp and you made him some proposal about joining your experience in partnership with his map; which he, being a man of honor, immediately refused. You thereupon fought with him and obtained possession of his map—or he in his innocence showed it to you, that map of the Germain scientifico which said, 'So and so many days up the Rio Kerary and at such and such a bend of the river.' And you came on immediately and commenced your digging. Finding nothing immediately, or at least, but the one stone, and your supplies running out, you came down to sell the one and to replenish your stores. Then you came back to dig some more. Is it not so?"

Excellent liars though they were, they could find no instant denial of my reconstruction of the story from the details which I already knew. They commenced indeed to recount a rambling tale. But their hesitation had been long enough.. I cut them short and said:

"Enough, enough. I do not want to hear lies. Tell me instead some truth about this sniping at you with rifles."

So they told me sullenly enough how the shooting would come suddenly and without warning from any direction out of the blackness of the jungle; sometimes by broad daylight, but preferably at dusk when the finding of the shooters would be difficult; and how they had hesitated to plunge into the woods against hidden rifle-fire; the more so. since they dared not go scouting singly, and together they dared not leave their down-river Indians, who would immediately steal their batelão and paddle away from that place.

By daylight the one or the other had scouted through the bush behind the digging; but had never found sign nor trail of their enemies. Therefore they blamed the shooting upon Indians, who alone would have such woodcraft. Yet again, what Indians would have rifles? And if so, how would they shoot so straight? For the Swede had been grazed once across the thigh and once by splinters from the cooking fire, and the Americano had almost smelt the balls that passed before his nose. So they had erected screens of branches between the camp and the jungle so that they might, at least, be hidden from view, and had hired these men of the Desana to act as outposts. But the shooting, though from longer range, still came with heart-stopping uncertainty; and the Indians were never molested; only the white men. So the nerves of both of them had just broken under the strain.

Truly they were in a pitiable case. I looked at the miserable pair beyond my rifle sights and I saw reason to laugh. Many reasons. For I was beginning to see how this elaborate jest of the jungle, in which they had acted as the lures to drag me into the net, was now turning against them. I was beginning to see an answer to the riddle of this shooting; vague, perhaps, and unformed, but yet—

"How long has this shooting been going on?" I asked them suddenly.

They told me, some two weeks, on and off. And then I laughed again. For the persistence of hope in my heart put the possibility into my mind. How a man, having lost his batelão in a fight with two other men, and having been wounded perhaps, might by this time have had time to recover. And then, if he had in him the makings of such a man as the jungle would accept for its own, a man of confidence and a courage that would not die and of a rugged health that would survive; and if he had with him a wise old jungle man to show him every trick and trap and danger of the jungle—why then it would be possible for such a man to learn and to absorb and to grow to be a child of the jungle indeed, and so to make his way overland, hiding from Indians and living, the good Lord and the jungle knew how, to this place, where men stole his digging of green stones, and to wage war upon them.

If! If! There were many ifs. But there remained room for hope. And so, instead of killing those two, I laughed; for surely was the great jest shaping itself against them. And as I laughed, I received confirmation for my lightness of heart.

In the form of a bullet it came. A crackle like a whip-lash in the air, followed by the smash and clatter in the jungle beyond, and then by the far smack of the report—from across the river.

"Celestes!" I ejaculated, and left my menacing of those two with my rifle to drop behind the pile of camp gear. For their part, their nerves were so overwrought that they screamed at the suddenness of this new angle of danger and leaped into the trench by which their wash water flowed.

And again I laughed. For that report was without any manner of doubt the long bullet of a high-power rifle of small caliber—such a rifle as Billee had carried.

And following on that first shot came presently the contrasting hum of a heavy ball and the subdued tock of a big bore from the cane fringe on the other side— such a rifle as I had given to Pacheco.

Well could I afford to laugh. Miracle though it was, and the many ifs notwithstanding, there was no mistake in my mind now. Billee, it must be himself! Billee the gringo and that good old scoundrel, Pacheco. Who else? But, "Miravel," I said to myself, "he must have grown, that boy. Billee, the jungle man, he is. For this is no business of an amateur."

So I leaped up from my shelter and waved my arms and—

"Billee!" I shouted. "Ohé Billee! Behold me, Theophilo!"

But, carramba, a ball crackled before my face so close that I felt the splitting of the air. I take no shame that I shouted in dismay and dropped behind my shelter faster than any marmot. Long shooting it was; but too terrifyingly close to play friend and foe with. From the water trench I heard an ugly laugh and the sneer.

"The red monkey has bitten that Theophilo, and he is crazy. He thinks that this devil is that gringo babe in arms."

Yet for my part I was convinced. Who else would it be but Billee, grown from his babehood in these last hard months to the full stature of a jungle man, and attending very capably to his own vengeances? But, assiste me Deus, what was I to do? This was a dilemma that was not made any the easier by lying behind a pile of trade goods and thinking on it. I tried in a foolish sort of way to lift my hat on my rifle barrel and wave it in some sort of signal. But all the response it brought was more bullets; fast and viciously close.

NAILS of the Green One, but I was in an evil case. There, across the river somewhere in the jungle fringe, crouched my Billee, resurrected out of the dead; and here, behind a pile of trade goods lay I, whose urgent necessity it was to make connection with him against these bandits as well as against that other army of ruffians who were on the way to rob our mine. There was he, hiding in the jungle with all the craft that cunning old Pacheco could command, from white med and Indians alike. And here was I hiding from him behind a case of lard—or for all I knew, behind a case of dynamite. Name of evil, it was a situation to drive one frantic. How was I to make myself known as a friend? On that side of the river they were expecting no friends in all the jungles of Amazonas. If I had dared to step down to the river's edge and gesticulate and shout, maybe I might have obtained recognition. But the river was wide at that bend—three hundred meters at least; a far distance for the voice to carry, or to recognise a man in the shadows of the jungle; and it was, besides, getting to be dusk—and those lads were wasting no time in conjecture about the personnel of their enemy's camp, nor losing any opportunity of lessening the number of their enemies.

I racked my brain and tore at my hair; for should I fail to make that God-given contact then, how long a time would pass before I could find another? And time just then was worth, perhaps, a whole mine of little green stones.

The senhores perhaps do not understand how easy it is for a man who knows the jungles and who wants to hide in them to remain forever hidden. But, believe me, you might camp along our rivers for a year and I be within five hundred meters of you all the time, and you would never know it. So I, knowing old Pacheco's cunning, lay in futile frenzy while the darkness closed—and the darkness, when it once begins to fall in those jungles of the equator line, falls with the speed of a falling blanket.

I was still cursing the irony of the circumstances when it fell. And with the immediate voices of the night, I, who knew some of the ways of the jungle, could hear the voice of the jungle—laughing at me. And those others, under the safe cover of the dark, crawled all wet and muddy from their water trench and laughed at me too. But to them I said:

"Laugh on, fools. Laugh on. You are very clever at stealing maps from a boy who used not to know anything of the jungles; and very clever at finding green stones to hoodwink a man who has no excuse not to know better. But you are not clever enough to know that the jungle is laughing at you even more than at me. A good joke on me this is for you to laugh at. Better almost than the joke of the green stone that you sold me for a conto and a half of milreis. But I make you a present of the warning that the jungle is even now preparing to extend that joke onto you. I make you a present also of your lives. They are for the jungle to attend to at its own will."

With that I left them to their own devices, to chew upon my warning and to be as miserable as I could hope. I went back to my own batelão; and with the first dawning I returned down stream to the mouth of the Kerary and sent one of my men to carry my carved stick to Yapu Ua. And he, having had fair dealing with me in the past, sent a sub chief bearing his carved stick to me with the message that his moloca was where it had been before. So I went up and made the ceremony of dipping the mandioca bread in the red hot chili stew with him; and when the women had taken away the dish I spoke.

"Hath-the á pure, Yapu the father of Ua," I said to him in the formal greeting. And he answered:—

"Hath-the á pure, Kama."

After which conversation could proceed. And Tasked him:

"Your men hunt as far as two days up the Kerary. Tell me, then, what is this tale of shooting with a rifle at the camp of those white men, and why have you not killed them already?"

A very cunning old chief was Yapu, and he grinned and told me, answering after the Indian fashion the last question first

"Kariwa, White Chief," he said, "my young men indeed hunt on this side of the river for two days up and more, for they are strong runners. But the farther bank, where the digging is, is the country of the Bahuana; so those strangers belong to them; and we have no desire to make a feud with the Bahuana over what is theirs by right Yet, since the Bahuana molocas are far away, the strangers made a trade with my young men, paying knives and salt and fish-hooks for their labor. Therefore I sent a message to the chiefs of the Bahuana, making an agreement with them that they should not kill those men as long as they paid my people the things we need. When they cease to pay, my word is that I send a swift messenger to the Bahuana, delivering them over with all the rest of their goods. And the Bahuana, desiring no feud with my young men, who are many and strong, agreed to this agreement."

"Oho," said I. "Some such thing I might have guessed. Now tell me of those other men who make war upon the strangers out of your country; and why have you not killed them?"

"We have not killed these," said Yapu, "because there is a jurupary man, a devil doctor of the Tucana people, who has sent messages through voices speaking out of the dark saying that he has a private war with those strangers. So we do not hunt him; particularly since he is very clever at concealment, hiding sometimes on this side of the river, sometimes on the Bahuana side. Yet my young men, who are brave, spying upon him, report that he has with him a white man."

So I laughed out loud in the gladness of my heart. Here was the proof. Who would the cunning fellow be but old Pacheco, and who could the white man be but Billee the gringo? So here they were, that clever scamp, Pacheco, and Billee, who had come into the jungles a tenderfoot. Under that master hand my Billee, it seemed, had grown to be a true son of the jungle, and was in a fair way to regain possession of his digging without any assistance of mine.

"BUT, picaro," I said to myself, "since the fool escaped with his life and was able at least to travel, why in the name of the Green One did he not steal a canoe from some jungle chief and come down river to me to get assistance in recapturing our mine, instead of going off like a mad man to wage a single-handed warfare against those robbers?"

Yet I was forced to give him a good mark for his accursed independence. That was Billee all over. Exactly as he had been repared to tackle the whole jungle all by imself when he first came to me; so he was now determined to regain his digging without aid. Proof positive of his identity. Who else would be such a princely fool? The more so since my suspicion about that digging for green stones in a clay bank was growing in my mind as fast as Billee himself had grown.

So I gave Yapu Ua a machete of Collins with a wire handle and said to him:—

"That white man js my friend. Give me now two of your best hunters that we go into the jungle to look for him without loss of time."

So I left my batelão with the half of my crew in the igarapé, the creek which runs below Yapu's moloca, and went with the hunters to hunt for the trail of Billee.

But what a fruitless hunting that was. Truly was Pacheco a master; and it very soon became evident to me that in spite of his clever pretense at being a devil doctor and his bold message to the jungle tribes, he was trusting them not at all. To hunt for a marked fish in the Amazon is a saying amongst us Brazilians. But to hunt for a man in the jungle is an equal task. Where the inner jungle stretches no man knows how far, and where today's lushy growth covers yesterday's trail, and where one must hew a road with machetes to travel ten miles a day, how is one to find a man who knows how to hide?

More than once those uncanny hunters of the Desana found where the camp had been. But it was always three or four days since it had been deserted. Aimlessly we toiled and sweated in that moist dimness of the under jungle where the sun never reaches, yet where the heat is as of a bath. As for me, I am a river man, I am no crawler upon my belly amongst the ticks and the wood lice. Fever began to come upon me and my stomach turned against meat.

In the meanwhile time was going relentlessly on. But with this new suspicion of mine about that digging in the clay bank time was assuming a lesser importance than I had given it at first. So when the hunters at last showed me a tree of a rare species which stood by the side of a jungle trail, I was willing to call a halt to this aimless wandering. Ingapu, the tree was called. I knew of the name. The message tree, it means, and it is used by the jungle tribes as a sort of post office. For the bark of it is almost white and it is an outstanding mark in the jungle. In it they leave signs and strange patterns of twisted liana vines, the meaning of which other Indians understand.

"Here," the hunters of Yapu told me, "that devil doctor is in the habit of leaving sometimes a present for the chief."

So I said to myself, "Good." And I wrote a letter and tied it in a waterproof wrapping of the puna bark and placed it within the little house that the Indians make in such trees. Presently this jungle runner of mine would find it and would come to me. In the meanwhile I would go back and wait in the comfort of my batelão safely tied up in the creek below the moloca of Yapu. Let those two bandits dig away in the clay bank, I said to myself, and I laughed. For my suspicion about that digging was that I was beginning to see another angle of this most elaborate jest that the jungle was conducting.

I have told the senhores about the paucity of names in these upper rivers of ours. It is the same in all pioneer countries, is it not? One finds within a few days travel the same name recurring, sometimes a little different, sometimes not changed at all. And I had a memory of that German scientifico as a man who, while wasting his life in a fruitless study, was filled with the terrible thoroughness of his people and was no fool to go running off his head, writing a map of finding treasure, unless he were very sure about that treasure. So I was able to laugh as I remembered that while the Rio Kerary was here, there was a creek seven days journey further up called Igarapé Kerary. And I wrote thus:—

"Fool," I said. "I have important news for you about this Kerary. I wait at the moloca of Yapu."

And I went back to wait in the comfort of my batelão, where my hammock rope would not be gnawed by wood rats in the night and where the insects that I ate with my food were such as I was accustomed to.

And what a tale it was that met me upon my arrival at the moloca!

THE Rio Kerary, where it had been polluted with the soil from the washing, was polluted now with blood. A big batelão had come up crammed with men, old Yapu told me; and these men had gone up the river silendy and had made sudden war upon the two first white men. And those two white men were dead, as were all their Indians. Also—and Yapu's face became suddenly ferocious as he told me—three men of the Desana who stood guard round the camp had been killed by the indiscriminate shooting.

I clicked my tongue after the Indian manner to denote sympathy. Old Yapu clucked back and said that it was indeed a pity for the families of those men; but his face remained fierce. But my sympathy had been for those white men who now held the camp, for these Desana, as I have said, do not forgive killings.

The laugh that came to me stuck in my throat as I began to observe the manner of the jungle in making its grim jest. First upon that German scientifico, whom, having permitted to discover its treasure and almost to escape, it slew at long distance. Then upon Billee the gringo, who followed the scientifico and who barely escaped with his life. Then upon the two who had stolen Billee's map, and, lacking knowledge of the upper rivers, had gone up the first stream of the name of Kerary that they came to and at the seventh bend of the stream had commenced a fruitless digging in a bank of clay. Then upon me, to whom they had sold a piece of a beer bottle for a conto and a half of milreis. Then again with swift justice upon those two, whom Dom Luis and his gang, for the sake of that green bottle glass, had put beyond reach of any vengeance of mine.

I had been able to laugh with the jungle hitherto as I saw one after another of the points of its jest, even when one of them touched me. But this thing frightened me. How was I to know whether I had served my full turn in the fun making, or whether the jungle was still reserving me in its net for a butt? So I remained uneasy while I waited for Billee to come. I was anxious to hurry away from that place, clear of the area of the net.

And in a very few days it became clear to me that I was far from clear. Instead of Billee came a hunter of the Desana with a piece of cardboard from a cartridge wrapper, which he said the hand of a devil, reaching out of nowhere, had thrust into his hand while a voice told him to carry it swiftly to the white man who stayed at the moloca of Vapu Ua. He had been almost afraid of carrying the bewitched thing. But his fear of throwing it away had been greater than his fear of carrying it. So he brought it to prove that he was a very brave warrior.

So I gave him a kitchen knife and then read the letter. Something after this manner had Billee written:

### LETTER

Thanks, you old mighty good scout. Mighty nice for you to come alter me. I know the news about the Kerary. Those fatherless ones have jumped our claim. So I'm off to shoot the —— out of them. Come on mucho pronto and bring plenty cartridges—And for the sake of St. Mike, some clothes.

Billee.

P.S. Pacheco says: "Unga irapu. Puranga yarula nge."

The Green One ride on him for that. Was such a mountain of madness ever heard of before? Here was I, with equipment and men, ready to steal away quietly from all that turmoil and to go hunting for our green stones with the boy under the wing of my experience. And there was he, somewhere in the deeps of the jungle, filled with all the hot independence of youth that knew it all and needed no advice.

"Cremento," said I to myself. Was this my Billee of the pink-and-white face and the innocent eyes, whom I had toiled so far to render assistance to? Or had the jungle bewitched him and turned that crazy spirit of his into the body of some other man, some hard old wanderer of the waste places?

The only saneness in all this insanity was the postscript of old Pacheco. Written out according to the sound in English it was. But I was able to understand it to mean:

"He is not mad. He is a good son of the jungle."

That at least was evidence of the jungle miracle which I had suspected. But I was disappointed in the boy. Here was I, after a most arduous travel of two months to avenge his death—and found that he was by no means dead. Then I had spent a most uncomfortable period in the sweat-and-insect bath of the inner jungle to save his life from the manifold dangers that lurked there—and found that he was apparently very well able to take care of his own life. And as for rendering him assistance to save our mine—carramba, no sooner had I found him than he rushed off to risk his life single-handed battling with those cutthroats over a worthless bank of clay.

Verily a superb joke. But I had gone past the place where I could laugh at it any more. A terror of this thing was growing upon me. I had thought that I had served my turn. But we were not out of it yet, Billee and I. This, was no infant's play that that wild youth had pitted himself against. A camp of some eight cutthroats with sundry Indians was a different matter from two scared men. There were plenty to guard camp while others, hard men and killers, scouted the jungles to find one lone white man who made war upon them with all the assurance of an army.

How I cursed him for a fool! It was desperately necessary that I find him now and tell him how much of a fool, before the jungle should conceive the further humor of letting one of his enemies do so first. But, carramba, what was I to do? The jungle, while it might well have made a whole man out of an inexperienced boy, could not suddenly put a grown man's foresight into the hot head of youth. My fool, in his eagerness to dash off to the rescue of his claim, had omitted to leave his new address. Was I to go off once more, crawling on my belly through all the jungles of Kerary, hunting for this maniac who hid from his enemies with all the skill that the jungle and Pacheco had taught him?

YET what else? We had escaped with our lives under the impending shadow of this joke for long enough, and I was filled with a horrid fear of lingering under such a grim humor any longer. So with rage in my heart as well as fear, I took my batelão and set forth. But I was no fool to go crawling and hewing a road through the inner jungle all the way to the digging, like that crazy young man of mine did. I went up the river in my boat as I had done before; only with this precaution—that I sent a man in a light canoe half an hour in front of me all the way. For it is by precaution that a man keeps alive in the upper rivers.

So I came without hurt to a tiny creek below the digging; and there I hid my batelão and took two of my men and went into the jungle to crawl about in the muck till I should meet my fool. And I sent two other men to scout on the other side of the river to catch him and bring him to me; for how should I know from where he would conduct his war?

But I chose the lower side myself, the side across the river from the camp, from where he had so successfully shot at me. And there I crept and climbed and sweated for days, just like any other creeping thing of the jungle.

There was but one sign that I could hope for; and presently it came to me—a rifle shot. I was almost able to be glad; but I knew too much to be sanguine. Half a mile away I judged it. Not more; for a shot, muffled and shut in amongst those vast trees, would scarcely carry further. Yet half a mile through the undergrowth at the feet of those same trees meant half an hour of strenuous and cautious crawling.

Was anybody but a fool going to fire a shot at a camp full of armed men and then wait in the same place for half an hour to let an enemy come and find him? Which, of course, was just what they were desperately trying to do. More than once during the following days as I lay in the jungle fringe watching that digging across the river, I would hear a shot somewhere to the right or to the left of me, and would see with satisfaction the scurry of men as they ducked for shelter. Not very often; for the place was now a fortified camp with earthworks thrown up for protection. It was seldom that a man showed. But when one did, a ball would come whizzing out of the long distance of nowhere and the man would jump in the air and run for his life—or sometimes drop out of sight.

What the damage was, I could not telL But it was pleasingly clear to me that those robbers were having a most unhappy time. More than once a canoe full of raging men would dash across the river and plunge cursing into the underbrush on our side. More than once, as I scrambled in the direction of the latest shooting, I heard the blundering of inexpert men floundering about in the undergrowth.

It would have been easy to creep upon these and take them by surprise. But to what good? Though I had no reason to be lenient with any one of Dom Luis' cutthroats, I could not feel it my duty to kill them for wearing themselves out digging in a clay bank where there were no green stones of any sort. And as for protecting Billee against them. Pouf, I knew that those blunderers could never come upon this new Billee of the jungles any more than they could upon me.

So I left those clumsy seekers to go hunting after ghostly rifle shots as best they might; and I spent my own days amongst the insects and the jungle cats and such vermin. And at the last I found him, of course.

It was in this wise: I was crawling with all the precaution that my experience knew towards the place where I had heard the last shot, when a hiss like the deadly warning of the jararaca sounded suddenly close to my ear.

"Em cima os maos!"

One does not argue with a whisper like that within two feet of one's head. I put them up, of course, without argument. And then the rifle barrel that thrust at me out of the foliage was followed by a face which hung suspended bodiless in the dense greenery. A gaunt face, seamed by hunger and tanned Indian-brown by exposure, bearded like a jaguar and with eyes of equal menace.

I must leave you to imagine my shame, senhores. That I, Theophilo, should have permitted myself to be caught at such a disadvantage was a disgrace that will stand, as a black mark against my woodcraft There was poor comfort that I was moving while the other had lain stilL for it should have been my business to detect the other's movement before he detected mine. To my great shame it was that the reverse had been the case. Yet there was some comfort in that face. It was the face of a hard, alert man, keen to think and quick to act The face of a man who had lived through much and had profited much by the living and who now knew more than just much. To that face I said:—

"I suppose you must be Billee the gringo. But—"

But the whole of the man crashed out from his concealment and fell upon my neck.

"Theophilo!" he shouted. "Why, you old ruffian!" And he swore at me affectionately after the manner of the gringos while he shook my hand and would not leave go and called me by disreputable names. Till at last he stopped to shout his laughter—and—

"Look, Pacheco," he crowed. "Look at who it is who came crawling so slyly, thinking to catch us unawares."

And in the next instant the shrewd monkey face of old Pacheco grinned out at me from the opposite side where he had lain in wait And I, I was so overcome that in the fulness of my heart, in spite of the shame of my capture, I disengaged a hand from Billee's and, Indian though he was, I shook hands with the old scamp warmly—which was a tale that he recounted with pride later to all the Indians of Yapu Ua.

But. here was Billee, capering in his nakedness—for the thorny lianas of the jungle had left him little more than his boots—and shouting again his exuberant abuse of me. I laid my hand swiftly over his mouth.

"Name of a saint," I warned. "Has the madness not left you yet? They will hear you across the river—to say nothing of the half dozen at least of our enemies who must be crawling about in the muck looking for that last shot."

But he growled in his throat and his eyes became fierce on the instant as he said:

"May the —— eat them. Now that you are here, what do those babes in the woods matter? They will never find us in a hundred years. Besides, we are now three. It is enough. Of those robbers six are left—perhaps five, I am not sure. I don't like this skulking in the jungle making a long-distance war. I am ready. We can clean out that camp in one afternoon."