RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

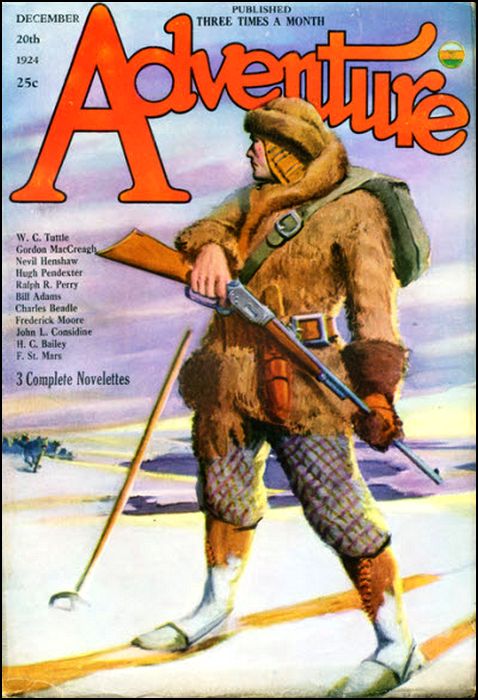

Adventure, 20 December 1924, with "The Trail-Smellers"

WILL I undertake a small freight for the senhores? Como não? Why not? Freighting is my business, and I, Theophilo Da Costa, will undertake to deliver a freight to any place in all Amazonas—provided the price is right; and the price is dependent upon the distance and the danger involved.

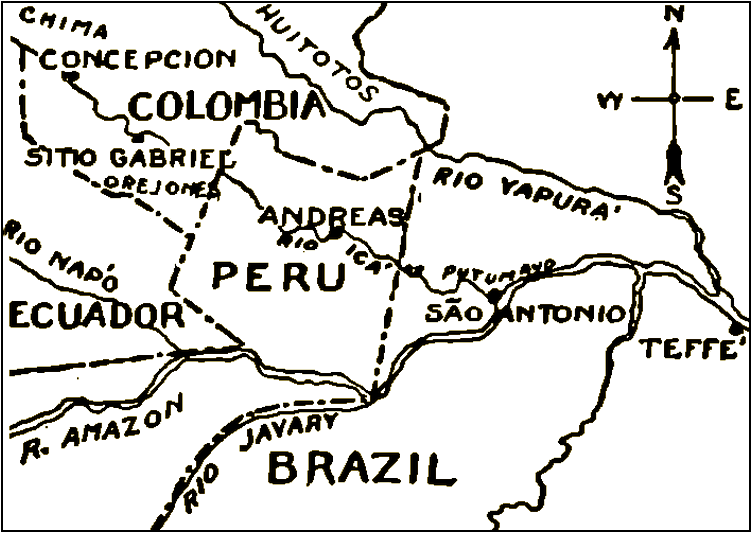

Up the Rio Içá into the Putumayo country? Oho! Into that disputed country of no man where the boundaries are indefinite, claimed by Ecuador and Colombia and Peru and our own Brazil; and where, while international boundary commissioners haggle interminably at Lima, the law is to him who is strongest.

The rubber has been abandoned these six years, since it does not pay. The little balata there is worked out; for the method employed by those foolish collectors kills the trees. Nothing is left but desolation; angry Indians who have been fed full-bellied with promises; and the crumbling sitios of traders who went up when the rubber was good and have never had money enough since to get away.

You, senhores, who travel up this Amazon River on the comfortable steamers of the Companha Navigazione, do not hear much of these things; but believe me who knows, it is true.

To carry your "little freight" would mean a special journey for me, which would be long and tedious with many places of bad water and with no other recompense. I would have to charge you for four months at least of time. Danger, I might easily discount; for, those Putumayos have been well beaten to tameness; and, while they sometimes, by reason of that very beating, are goaded to uprising, my men are all Huitotos from the Yapurá, and few of these other tribes care to get into trouble with Huitotos.

So there lies the case, senhores. For my time I must charge you one conto of milreis. If your freight is worth it, buom, I am ready to start tomorrow. Tell me but what it is and where it is to be delivered. But I tell you in advance that there is only one freight that is worthwhile carrying in these days up the Rio Içá, or Putumayo, as men call it after it passes through the borders of Brazil into Peru and through that corner of Peru into Colombia—if ever those borders will be settled.

To Concepçion? But, senhores, why not say, "to the Amazon River?" There are a hundred Concepçions in this Amazonas of ours. Four I know on the Rio Içá alone. We have Conceptao da Virgem on the Brazilian side, and the Conceptions Imaculada and Maravillosa in the Peruvian corner, and then just plain Concepçion far up in the foot hills of Colombia. The difference is a journey of a thousand miles. Who, then, in all these Conceptions is to get this freight which is so important?

Como? How? A case of pâté de foie gras? Ha ha, it is enough. The senhores do not have to tell me any more. I know exactly where you wish me to carry this freight and to whom it is to be delivered. You wish me to go even beyond the country of the Putumayo, beyond the caxoeira of Unti, or cachuela, as they call the bad water rapids up there in Colombia. And the fancy food is for Gabriel, the administrador of Indians, no?

Ho-ho, for Gabriel the Zambo, the half-negro and half-Indian. Gabriel, who never had but the one name; but whom they call, "Angel" Gabriel; for when his voice is raised a man dies. Senhores, this interests me much. But your freight will I not carry. I will not cheat you. For look, they do not want fancy foods at the sitio Gabriel today; no, not even though paid for in advance. That one freight of which I spoke as being worthwhile do they want; and the sitio Gabriel is the one place where they want it.

Guns, senhores. Rifles of Weenshterr, or better still of Mauserr, with many cartridges, is all that they want; and they will pay for them in gold. Gold that the Indians bring in fat quills of the jabiru stork.

Look you, amigos—draw your heads near and pretend to look at this map while I tell you softly—There are rifles on this steamer, a consignment from the house of Frantz Weiborg in Manaos going to Quito, where the garrison is talking of revolution because the pay has not come for four months. What matter how I know? It is my business to know what happens along these upper rivers of Amazonas. Now, if the senhores can devise some means of acquiring these rifles, or a part of them, we can do good business together; for Joselito Davis, the Blanco, will pay many quills of gold for each such weapon.

Gold that the Chima Indians bring in from nobody knows where; for nobody has ever been into their country except this Joselito. My belief is that they smell it out; for they hunt game as do wolves, running with their noses in the air.

Listen, I will tell you the doings at the sitio of Gabriel o Angelo, and you shall see what a trade may be done in rifles just now.

THIS Joselito, you must understand, is a blanco, a white man like ourselves. His father was of America of the North. A man tall and fierce, and a miracle with the pistol. Him I never met; but the tale is that one might throw a gourd in the air, and he would immediately produce two enormous revolvers of Colt from nowhere and would pierce it with twelve shots.

A great traveler was he of much eccentricity and an unconquerable antipathy for his own people. He settled first in Manaos; and from there suddenly one day, upon arrival of a gringo who said he knew him, leaped upon a river steamer and came to Teffé at the mouth of the Yapurá. From there he came suddenly here to São Antonio and stayed but a few months. Then swiftly once more he packed up and traveled up this Rio Içá, pressing ever deeper into the wilderness where he might not be bothered by meeting with wandering gringos.

Finally he reached the country of the Muniwas, who had never seen a white man; and there he seemed satisfied at last, and took some six or eight wives to work for him, and built a chacra and settled down to live on plantains and mandioca and monkey meat.

Truly men are strange and have many strange ways which are beyond our understanding. But what matter? I tell you these things only that you may understand what manner of man his son was.

José, they called him; and later Joselito. For as the lad grew up with the stringy muscles and turbulent spirit of his father, his talk was ever of becoming a bull fighter, and Joselito, "The Wizard," was his hero. Long-faced and thin-nosed he grew to be, with narrow eyes and faded hair, as light skinned as any one of my Huitotos; he never gained the height of the Americano, his father. Yet a youth good to look upon and of good promise.

But what chance of fighting bulls could ever come to a youth born and brought up in the furthest foothills of a jungle river?

The father died, and the boy grew up and followed the fate of all his kind. He drifted down the river to the rubber camps of the Putumayo. When the rubber was good he made money and lived on champagne and caviar along with the other padrones of the rubber gatherers. When the rubber from the plantations of the East Indies cut a big hole in the market and the jungle rubber fell through the bottom of it, he drifted up the river again to cast in his lot with this Gabriel the Zambo.

A cunning fellow, this Gabriel. Balata was beginning to find a market; and he knew where there was balata on the Colombian side. So he quickly called himself a Colombiano and made application to the government at Bogota to be appointed Indian agent at his hacienda of San Gabriel de la Annunciaçion y Concepçion.

Of knowledge of the Holy Book I have perhaps less even than this Gabriel. So I can not comment upon the grandiose name he chose. But this I do know: The estate consisted at that time of a palm thatch hut with a chilli-pepper plant in front and a mandioca patch behind.

But he made representation through friends of his, rubber men who had come down into the Putumayo and were now going home. All rubber men lie in harmony together. So in the course of time there came a pronunciamento of appointment; and Gabriel the half breed forthwith sat down to grow fat and become a king. For the office of administrador of Indians carries with it authority as magistrate, which means in these far places of isolation lord of the high justice and the middle and the low, as it was in the old days.

Strange creatures indeed are men in these jungles where the nature that the good God gave them shows itself without the cramping restrictions of civilization.

Consider this Joselito, senhores; a youth of promise and action, a man as white as you and I, one who may be relied upon to keep his bargain in a trade. And consider his fate: To be the underling of this half breed.

And why? Because the good God gave to the other the blessing of cunning unhampered by the curse of conscience—the one as great a necessity in these jungles where men are close to the primitive, as the other is a handicap.

So Gabriel settled down and grew fat while the Indians who were unfortunate enough to live on the south bank of the river—Orejones, they are, a quiet, subdued people—built for him a sitio with store rooms and sheds and landing stages, and then proceeded to fill those sheds with balata.

And while Gabriel grew fat, Joselito grew ever leaner; for to him fell all the labor of directing the gatherers of the gum; and the direction of a crew of balata gatherers is more strenuous than laboring among the trees.

Search gangs must be organized to go out and cut their way through the densest jungle to hunt for the trees. Ax men must be sent out to fell the located trees and gash the bark, so that the latex may ooze out onto a bed of plantain leaves. Porters must be sent out on the trail of the ax men a week or so behind to gather up the coagulated mass of gum and leaves and dirt. And the whole must then be boiled in great tubs and stirred and strained, and boiled again and stirred yet again, till it has been through some four or six of such boilings, depending upon the condition of the latex, before it is white enough to be cast in molds of twenty kilos each and stamped with the name of the producer.

And all this labor of organization fell upon the shoulders of Joselito; for the nature which he inherited from his father was to be up and doing; while Gabriel lolled back in a long-armed chair which had been stolen at some time from one of these very Companha Navigazione boats and grew fatter every day. So fat he grew that his pajama suit in which he lived would meet no more across his gross belly. And ever he smiled with unction as he thought upon the balata that was piling up in his store rooms, and paddled his bare feet in an earthen bowl of water when it was hot.

BALATA, senhores, is no more than a question of labor. For it is not a tree that grows in groves. It is in many places, but usually so isolated that it does not pay to search it out. It is only where, for reasons of soil or rainfall or whatever it may be, it grows fairly close together that the ordinary producer can work it at a profit. But any man who can control sufficient labor sufficiently cheaply may work balata almost anywhere in the upper rivers. Note now the craft of this Gabriel. His official position had put him in the happy position of producing it at the minimum cost, for he paid his labor nothing at all. Having gained for himself official authority, all that remained for him to do was to enforce it.

For a single man to enforce his authority over a few thousand jungle Indians is easy, provided that the jungles are sufficiently far enough away for no reports to filter out to the government, and provided that the man is not handicapped with the curse of a conscience.

All that Gabriel did was to summon the sub-chiefs of the tribes before his throne and tell them that he required so many men to work balata. If a sub-chief did not immediately promise to send the required number, Gabriel would suddenly heave himself up into a sitting posture and would roar forth at him in the great bull voice that is the heritage of all these half breed Zambos.

If that did not immediately terrify the savage into submission, the fat smile would come back into his face and he would pick up the great pistol that lived ever in the chair with him under his thigh and would shoot at the man. Sometimes he hit him; sometimes he missed. But the result would always be the same. If he missed, the man would be frightened into obedience. If he hit—well, there were other sub-chiefs, and the Indians to work balata would swiftly be forthcoming.

A veritable king of the upper Içá became this Angel Gabriel, as do all these far administradores dos Indios. And he was wise in his ways. For, look you, what complaint would ever reach the far government of Bogota? There is no trade that goes up over the mountains from this last removed corner of Colombia. Trade comes down river through the last removed corner of Peru into the almost last corner of Brazil. And even the boundaries, as I have said, are in dispute; and who is there to.care or interfere with what happens in who knows whose country?

Toward us—that is to say, toward me; for few traders ever go so far—the Zambo was ever careful to be most affable and hospitable. Many a cargo of his balata have I brought down here to São Antonio and delivered safely to the down-river steamer; and many a time have I eaten his rice and his stinking pirarucu fish; and have kept my own counsel about the tales that have come to me.

Not one, but a hundred Indians have begged me in their helpless way to make report of his doings, refusing to take payment of the mirrors and fish hooks which I gave in trade for their resin and feathers of the egret. But to whom should I report? Meu Deus, there are worse men than he in the Putumayo.

More than once has Joselito spoken with me, conferring upon whether something might not be done for this needless oppression. But to do anything would mean depositions and witnesses and charges made by responsible men at the capital. And I, I am a river man. I do not journey a month over the mountains to Bogota.

To Joselito I suggested that he journey to Bogota himself and lay the case before the Ministerio de la Hacienda. But to travel over the mountains requires, believe me, senhores, an expedition with many men and mules, a costly affair. And Gabriel contrived, as is the custom, to keep his few paid assistants ever in debt to himself for goods drawn from his store. Nor would he ever permit any one of them to own a pistol. All the need that might arise for the use of pistols in the sitio Gabriel, he said, he could amply take care of himself.

Very cunning had this Zambo been in all his arrangements.

Então, to make matters short, thus the affairs progressed with the usual harmony of these upper rivers until came the woman to make the inevitable discord.

I have said, senhores, that the greatest handicap to a jungle man is the curse of conscience. I would amend that by saying that the one yet greater calamity that can befall a man where civilization ends is a woman. One woman. Many do not matter. They are but a temporary nuisance, as I know who have had them. But one. Defende me Deus! May the good God protect me from losing my head. It is sufficient that He has cursed me with the conscience that is difficult to train.

This was a woman of the Huitotos, who are well famed for their comeliness and much sought by river men for their qualities of virtue and domesticity. I do not know how she got there; but probably she came with some party of her men folk, who are as famous for their strength and river craft as are the women for their looks.

At all events this Joselito Davis must see her; and it was immediately his evil fate to fall utterly in love with her, and she apparently with him. Nothing would do but that he should marry her.

"Fool," said I to him—for I was there at the time on this last up-river trading trip— "you are a Blanco, even though you do live in the last corner of the earth and work for a Zambo. You are a white man, Senhor Davis—" I gave him the title to stir up in him the pride of race— "A white man like myself. And we of the upper rivers do not marry. Give the girl a measure of cloth and a gift for her father, as is the Huitoto custom, and make her grateful as well as happy."

But he was young and without the power of reason; and the Indian half of his blood, I suppose, called to him. So he persisted in his determination. And right at that point the complications that hang ever round the skirts of a woman began to wrap themselves round him.

THE first was Gabriel. As magistrate, he had the duly licensed power to make marriages. Also many other powers, as of imprisonment and punishment; to which he had added of his own accord all the other powers which he happened to think of. And one which he thought of most frequently and with greatest relish was that of the high justice and the middle and the low.

So, when he saw the maid, he smiled his fat smile and said, no, he would not marry them; at all events not immediately. Later perhaps, when he might be tired of the Rirl. And he lay back in his chair and dropped his hand to play with his great pistol, and smiled more unctuously than ever as he looked upon the girl, who was well shaped and fair.

Very high handed? Assuredly, senhores. And foolish, too, to treat his right-hand man so. But he was drunk with his own power, this Zambo—as is always the case with the breed when power comes into their hands. And furthermore, he was in an evil temper these days; for the balata was almost gone; and though he flew into terrible rages and shot at helpless Indians, very little was coming into his store sheds. Hardly worth my while to carry trade so far any longer. And indeed this would have been my last trip, were it not for the matter of the rifles.

So the case was apparently settled. The king had spoken. There was no more to be said. Joselito came to me for counsel, much troubled.

"If you must have her, take her and run away," I told him coldly; for I was disgusted that a Blanco should so let his face be pushed into the mire by this gross fellow.

But I was wrong, senhores. The lad was still young, and his environment had been all his life one of submission to those in higher authority. And rebellion against higher and established authority is a very difficult thing. The boy needed but some happening which would stir him deeply to arouse the true spirit of him.

So I answered him with more kindness when he asked me again:

"Where can I run to? To the south are the Orejones, and to the north are the Chima."

True, it was a desperate situation. On the southern bank of the river, where stood the sitio, were the Orejones, who hated him because he enforced the commands of Gabriel the king, and who were moreover the abject creatures of the fellow, obeying his least command.

On the north bank, the dense jungles peopled by the Chima, wild implacable creatures, so close to the animals that even the naked Maku nomads whom all other Indians despise, look down on them and call them the ground apes. Squat things they are, with monkey faces and bodies hung well forward and stooping, fit for running through the tangled tapir trails which are their roads. And they hunt, as I have said, by scent, like the great dogs that our forefathers employed to hunt the runaway slaves.

This is a true thing, senhores. They are in appearance, and in this particular of over-developed scent organs, the counterparts of the Chunchos of the far southern jungles of Peru, whom the good padre Ignacio Ferrero has described at length. It is probable indeed that they are a wandering offshoot of that tribe. Myself have I seen one of them, for a small reward, smell out a garment hidden in the underbrush, and scuttle then, clucking and chattering, into the jungle, taking the garment with him as being sure of what he held in his hand and suspicious that the promised reward would not be paid.

This much I know for myself. But the Indians tell miraculous tales of their prowess. Better than dogs, they say they are, having more intelligence; yet falling short of dogs on a faint trail by reason of the fact that they sniff the air rather than the ground, and the scent may thus be overlaid by the stronger scents of the jungle, such as the overpowering scent of certain orchids or the sweet-sickly smell of bee trees or that strong sour-sweet smell of ants which even we white men can detect.

Much of these Indian tales can we overlook, of course; but, at that, what chance would a youth, even though he knew the jungles as well as this Joselito, have of winning through such a people to the more friendly tribes still farther north on the Rio Yapura?

So I advised him kindly.

"Fool," I said. "Go up-river to your own people of the Muniwas. Raise a war party of the young men and come down and kill this Zambo and be king in his place."

His long narrow eyes fired at the thought. But after thought he shook his head.

"No," he said. "They are not my people. I am a white man."

Então, bom. I shrugged. What was I to do? The affair was, after all, not mine to embroil myself with a ruler who could cut me off from the upper head waters whence came the best feathers of the egret and where I was planning to go at that very time.

YET that same night the spirit of the lad awoke in him. The necessary deeply stirring happening was apparently his so foolish love for this woman. So he took his mate, as a true man should, and stole a canoe; and when morning came he was gone.

But not up-river to the Muniwas, as I had counseled him. What youth of twenty-two or so ever takes good advice? Particularly when his judgment has been unbalanced for love of a maid?

When it was found that he was gone, and with him the woman whom the king had selected for his own, Gabriel o Angelo roared so that one of his disgruntled underlings muttered in my hearing, "Gabriel o Burro." And indeed his gross, hair-covered belly panted beneath his open pajama coat in keeping with his voice, like a wind-broken mule's.

Furious inquiry brought trembling Indians of the little settlement which fringed the river bank below the sitio who said that they had seen him come softly by night with the woman and take an uba, a light dug-out, and paddle swiftly downstream.

Then I knew what was in his mind. He was speeding to Andreas in the Putumayo, where there is a mission, in order to get married like a white man forsooth. But, tcha-tcha, what foolishness! I could have told him what would happen.

Gabriel roared and swelled at the neck, and gave orders for a fast canoe with six paddlers to start immediately in pursuit; and to come back with both the fugitives; or it would be better for them not to come back at all.

The result, of course, was inevitable. What chance has a two-paddle canoe, one of them a woman—even though she be a Huitoto—to outdistance six strong men born with paddles in their hands? They took but a hurried supply of farinha of the mandioca yam and sped from the bank, verily like an arrow, using the short choppy pulling stroke of all these Indians of the Içá. Not like my Huitotos, who use a long stroke, pushing from the shoulder, which is perhaps not quite so speedy, but which they can keep up for endless hours at a stretch while they take turns to maintain a humming rhythm of mm-m—hmm mm-m—há on two notes.

The Huitoto method, I think, is better. Yet I knew that these pursuers would keep up the chase without a break for rest or food, resting in relays of two at a time and taking for nourishment only the farinha gulped down with river water dipped up in a gourd, on which fare they can subsist for a month if need be.

My heart pained me for that young man; for I knew what the outcome would be. And Gabriel saw his canoe go off and shouted his last threats at the men, and then returned to pant in his chair after that exertion. And slowly, as his breath came back to him there came with it the smile, fat and oily and very evil. And he began to tell me with gusto what he would do to that couple who had so dared to flout his royal authority.

But I had other business to attend to, and left him to his own enjoyment. I had a leak in one of my boats to stop, and I was in difficulty, for I had no calking material. But I overcame it after much thought by melting down resin of the puna tree with butter, which made a very satisfactory pitch. Also word had come to me that some of the less wild Chima were hiding in the jungle fringe across the river, waiting to trade with me for iron arrow-heads and fish hooks.

A half day's work, not more; and I was in a hurry to get on up river. But I waited over to see what would happen to this foolish Joselito; and it occurred to me, too, that my presence might be of some possible service to him.

On the third day they came back, the pursuers and the pursued. But of the six who went only four came back, and of the four, two carried machete wounds. So the lad had fought. I was glad. But what availed his fighting, after all, since both he and the woman lay bound in the bottom of the canoe?

Gabriel lolled in his throne under the thatch of his veranda which looked out on to the riverfront, and smiled as a spider must smile when its prey comes into its trap. I stood by, thinking that perhaps I might at least save his life for Joselito; for I knew the evil that lay beneath that fat smile. But Gabriel was not a fool. Joselito was his best worker, and he did not intend to lose that labor just yet.

FOR a while he gloated over the two as they stood before him with their hands bound in front of them, as is the custom of these Indians, and which, after all, is safe enough and very practical; for a man so bound may eat for himself without the trouble of loosening him, and a simple cord passing under his thigh prevents him from taking his teeth to the knots except when he is permitted to eat.

The men of the sitio gathered round, half-fearful, half-curious, with the apathy of well bullied men. But they left a wide space between the prisoners and the river behind them. That is to say in other words, before the range of the pistol. Also the men who held them, held shrinkingly at arms' length. Very illuminating was their attitude on the customary method of justice at the sitio of Gabriel the angel.

Gabriel said no word. Neither did the prisoners. Only the boy glared at him as a jaguar glares, without a flicker of the eye. To which Gabriel replied with a grin like a caiman, and pointed with his head at the beating-post.

This post was a diversion of his own thinking. Simply a post planted in the ground, and some six or eight feet high. A culprit to be "corrected" was but lifted till his bound wrists passed over the top and there he stood then, free to move, to run round and round the post in his efforts to escape the lash of twisted tapir hide; thereby affording much amusement to the beholders. Truly a pretty sport.

The creatures of the Zambo seized Joselito and hustled him swiftly to obey their lord's order. He saw me looking at him, and grinned at me wide open.

"He has stolen a canoe, and he has killed two men. It is the law," he said.

I remained silent. The man was cunning like the devil, and it was his right to administer justice.

But Joselito made no sport for the crowd. He refused to run round the post as the whip tore the already ragged shirt from his back. Neither did he cry out. He leaned merely against the post with his head, taking a loose end on the thong that bound his hands between his teeth, and braced his back to the blows. The Indian who swung the whip remembered that this was the overseer, the jefe, who had enforced upon him and upon his people the orders of the king, and he took joyful toll for all the labor that he had furnished without pay, till the Blanco's knees began to waver and grow limp and the head and bound wrists began to slip slowly down the pole. Still came no cry from the lad. Truly had he found his spirit, the spirit of the tall fierce man from the north, his father.

But from the woman came a sudden cry; a scream as of a tigre da montanha. With the scream she turned her head suddenly and bit fiercely into the arm of the man who held her. Shouting on the name of God, the man let go of his grip; and she, screaming again, ran swiftly forward at Gabriel where he lolled back in his chair and gloated.

As the hands of her man had been passed over the post of torture, so she threw her bound wrists over the head of Gabriel and sunk her teeth into the side of his neck, tearing at it as the tigre tears at the thick vein of a fat tapir.

With the startled shouts of surprise from the others mingled my own shout of encouragement; for at that moment I hated this fat beater of men. But the man's very fatness saved him. Too deeply protected was the vein. His men rushed forward and dragged the woman from him and held her, panting and spitting fury, while he in turn panted in great sterterous sobs and stanched his bleeding neck with the corner of his pajama coat.

As the fear presently began to die out of his eyes, the rage began to come in. And as his breathing began to ease, the voice came back to him. Like a bull of the sanded arena he bellowed, and with a shaking hand he fumbled for the pistol beneath his thigh and lifted it.

But even in his rage he caught my eye, and his natural cunning reminded him that I would be a bad eye-witness to have to his doings, being not without influence in these upper rivers. So he pointed the pistol, instead of at the woman, at the whipping post.

"Her too," he roared. "Remove that man of hers and give her a taste of the taming that comes to these who show disrespect to the agent of the government."

But at this I stepped into the matter.

"Gabriel o Angelo," I told him. "This thing will now cease."

He looked for a moment as if he would point the big pistol at me.

"And why not?" he frothed at me. "Why in the name of all —— the not? Car'alhos, am I not the justice of the peace, appointed by the government, and has this savage cat not broken the peace? Why shall she not be beaten?"

I was able to smile in my turn, for the fortune of the circumstances was all on my side.

"Because," I said to him with much enjoyment. "Because this woman is a Huitota; and my men are all Huitotos. Fifteen of them, all armed; and it is well known that the Huitotos do not permit their women to be beaten by strangers."

He choked on his rage then; but even so the blessing of cunning did not depart from him. He looked round and saw my men standing with sullen faces; and he knew that they could erase his sitio from the scene with ease as well as with much gusto. For—here was the rebound of justice—he knew that he could expect but little defense from his own Indians.

So he swallowed his rage, gulping hard many times, while he still dabbed at his lacerated neck, from which the blood flowed plentifully over the dirty pajama coat and fat naked belly.

"Very well," he grumbled. "Good. The justice of the government will be magnanimous. Put them both in the calabouço to think over their crimes for a few days; and we will say that they have been punished enough."

Then he turned again to me with a smeary friendliness.

"Amigo Theophilo," he said. "It is for your sake that I do this. Moreover I am a just man. Though in my just anger I might have been impelled to exact the full penalty of the law; for you will admit that I was much tried. Come, let me but get one of my women to bind unguent upon these wounds where that she-cat of the pampas bit me, and we shall eat together."

But I had no stomach for his rice and fish and yet less for his company. So I gathered my men and took to my boats, having wasted enough time already; for I was bound up-river to the headwaters where the garca hunters would be waiting for me, according to arrangement, with two season's supply of feathers of the egret. Five month's journey was before me and much bad water. So I cried the "Awai-ee-ee-o" and my Huitotos dipped their round-bladed paddles and bent to the long song of mm-m—hmm mm-m—há.

THE next that I heard of Joselito the Blanco was a confused jumble of stories relayed from one river Indian to another. A matter of small importance to travel so far, you will say. Without doubt, senhores, a little affair But in the upper rivers nothing ever happens; and such matters constitute the news of one's neighbors, even though the neighbors live with a hundred miles of wilderness between them.

It is these little things that are the gossip of the day when canoes meet. Why, I have heard four hundred miles away such trifling matter as "The head-hunters have made a raid on So-and-So's village," or "Such and such a woman's child has been carried off by a jaguar."

So the tale presently filtered up to me that the woman had been released from the calabouço and set to work with the other women of the household of Gabriel, with the promise of regaining the royal favor if she conducted herself well. At which I was forced to smile; for he was a gross beast, and the maid, as I have said, was fair; and I knew that he was but seeking to save his face before he should take her.

But she, so far from behaving herself, made endeavor to effect the escape of her man, who was not to be forgiven so easily—as why should he? For there was but little work to be done just then with the balata gatherers. She was, of course, caught in her attempt—the other women gave information against her, it seems—for she was young as well as fair.

And then—the tale was not very clear; for the man who told me had omitted to ask unimportant details—somehow or other the woman died. No, she was not beaten. She just sickened and died. I have thought since that some of the other women could possibly explain how.

So that ended that complication. The way for the forgiveness of Joselito and for his return to work was now clear. It required but a little period yet for him to forget his infatuation and his anger against his chief. Gabriel, in fact, even condoled with him through the bars of the door and assured him that he personally bore no ill will against him; but that his offense against the law in the killing of the two men necessitated yet a little while of incarceration. So that presently, as he hoped, all would be peaceful again and a good worker returned to labor.

Often have I laughed to myself in imagining the unction of the man as he spoke his magnanimity. But this Joselito seemed to be incapable of appreciating his chief's spirit of forgiveness. He contrived somehow his own escape one evening and burst suddenly in upon the Zambo as he sat at his meal attended only by his women.

Weaponless he leaped upon his enemy with his bare hands to fight him as the white men fight. And the tale of that fight was good hearing. Would that I had been there to see it. Calling him a black half-breed and a hairy monkey of the woods, he buffeted the fat Zambo about the face with his fists and elbows and tore much hair from his head and finally kicked him in the stomach, so that he groaned like a stricken ox and nearly died. He would indeed have torn the throat out of the man as he lay; but that the shrieking of the women brought men running; and they threw themselves upon him, five at a time, and dragged him off and thrust him once again in the calabouço.

When Gabriel the Angel recovered under the ministrations of his women he was still a very sick man; but his first speech, thickly through his swollen throat, was that on the morrow the boy would surely die at the beating post; and that in the mean while, as an earnest of what was coming to him, his tongue was to be cut out for the things he had said during the fight.

Yet in the same moment he changed his order, saying, no, let the tongue stay, for he desired to hear him scream for mercy under the whip. Let it be an ear, and let it be suspended round his neck by a thong.

A fellow by the name of Gorgio, a brother of one of his women, whom he had raised to a deputy administratorship, took seven others and went and did this thing. And when he reported the doing to Gabriel, that one laughed like a wolf and fell to coughing blood by reason of the soreness of his throat. Yet he laughed still at the thought of the morrow's enjoyment.

But Joselito Davis did not wait for the morrow. In the night he escaped again; it turned out that he had gnawed a window bar with his teeth; for the calabouço was but a homemade affair with hardwood fittings instead of iron; and in the general confusion of the night the thing had been overlooked. So he got away and swam the river to take refuge in the jungles of the northern shore.

Gabriel's fury was no more than was to be expected. But what could he do? The men who were responsible for the guarding of the prisoner, Indians of the Orejones, of course, when they found that he was gone, ran away to hide in the farthest confines of their tribe. So presently, when the fury was exhausted, Gabriel laughed again.

"I would have enjoyed his punishment myself," he said. "But the Chima of the deep jungles know things about killing that even I can not hope to emulate. Send them a garment of his to smell, and promise them a whole pound of fish hooks for his head when they are through with it."

SO that was the end of that matter. I was sorry when I heard of it, for the lad had proved himself to be a man. On my way down from the head waters I told the tale to the chiefs of the Muniwas, hoping almost that they might send their young men to make a raid on the sitio Gabriel to take vengeance for a man who was the son of a woman of their tribe. But they took counsel and said:

"He is not of our people. He is a white man. And why for a white man's sake should our young men attack a sitio where there are guns?"

Which, after all, was no more than was to be expected. So I came on down, thinking that this was but another case of a good man destroyed by the complications which hang round the skirts of a woman. I considered him as dead. Yet the next news that I heard of this Joselito came while I was at the sitio myself.

I was delayed there a full month by reason of an attack of the malaria terciana; and while there, there came one day a man in an uba, a dug-out of the smallest size. So little and so low in the water that he looked, as he paddled up the river, exactly as if he sat in the water and progressed.

He grounded his craft on the beach right in front of Gabriel's veranda and came up to talk with us. And as he approached, Gabriel fell from his chair with fright; and I, too, muttered a defende me Deus, and prepared to back away to a distance.

For the man's limbs and face were all deeply pitted with little scars and eaten away as by some frightful disease. He guessed what was in our minds and made haste to reassure us. He grinned a lipless grin and called out in a thick lisping voice, as if the tongue, too, had been affected:

"No, it is not the smallpox; nor that other. It is but one of the mischances of the jungle."

And he came into the veranda and stood before us. Truly he was a sight to inspire horror. He wore garments of the tapa cloth, which is made by beating out the bark of a certain tree, scanty enough to show the terrible pitted scars on his body. But the worst was his face.

"God have mercy," I said to myself. "That such a mischance does not come to me in the jungles."

The man's nose was gone, eaten down to a hollow such as one sees among the lepers of Villa Sancta. The lips showed gums and teeth in a perpetual grin. The ears were just waxy patches, like a macaw's; and from the midst of the wreck glowed the eyes, small and red like a parrot's.

Yet he seemed to be full of a considerable satisfaction; though in truth it was difficult to tell whether this man grinned or scowled. There were no features left to express his thought.

"Men Deus, amigo," said Gabriel to him when he had sufficiently recovered from his fear, "but the jungles have treated you more badly than most."

The man grinned—apparently.

"Not so badly," he lisped. "Look."

And from his girdle he produced quills. Thick wing quills of the jabiru; a whole bundle of them. And they were all filled with gold sand.

"And I know where there is more of it," said the man, "a riverbed full. But I need outfit. Provisions, medicines, weapons. Particularly is my first immediate need for weapons. A machete, long and heavy, and a pistol, the biggest in the land; for they are a terrible people where that gold is."

Gabriel was ever eager to make a trade; and especially was he eager when he knew that his customer had dire need; for then his price mounted according to the need. So he heaved himself out of his chair and waddled to his storeroom with the smile of benevolence which he always prepared for the charming of his customers when he told them his prices.

"First the pistol," said the man. "For that is my greatest need; and you must show me how to use it, for I am unaccustomed."

"Meninho!" muttered Gabriel. "Unaccustomed to the use of guns; and are you not afraid to venture back where mischances like yours happen?"

The man thrust his hand beneath his bark shirt to finger an amulet which hung from a cord, and crossed himself and barked what was meant for a laugh.

"I am nowadays afraid of nothing," he said with hardness in his voice. "Show what you have."

So Gabriel produced a great revolver of Colt and told him:

"Look! This is a pistol of the finest. It belonged to an Americano who came to live among the Indians and who died; and the pistol came to me then in trade. That Americano could hit with it the head of a lizard at forty paces. Its accuracy is of the best. This is the finest and largest pistol that I have. It is the mate to the one I use; and you may believe me, who know, that it will kill a man very completely at forty paces. It will cost you two quills of gold."

"Good," said the man. "That pistol is worth anything at all to me. Show me now how to use it."

So Gabriel waddled back to his chair, for standing was a pain to him, and explained the loading and the care of the weapon; and he told the man:

"Look now! This is my advice. Since you have no practise with the pistol, the way to shoot straightest is to rest it, so, over the crook of your left arm to steady it. And when you shoot at a man, shoot not at his head, which is small; but at his stomach, which is large. He will surely die just the same, though it will take longer and hurt more, much more. But that—ho-ho—that is his misfortune."

AND he showed him, further, how he should score a cross in the nose of the bullet, which was a talisman of luck and would also cause the ball to break apart in the wound and do deadly damage. And he told him, too, how he should press slowly upon the trigger and not jerk it in firing the shot. All the use of a pistol he taught him; and he loaded it up and gave it to him, saying:

"That pistol, my friend, is cheap for only two quills of gold."

The man looked at the weapon.

"This pistol is well worth two quills of gold to me" he said.

And he stood there in the veranda in front of Gabriel and rested the barrel on the crook of his left arm and pointed it at Gabriel's great naked stomach and pressed slowly upon the trigger.

Gabriel's great body squeezed back in the chair as if struck with a great weight. His eyes opened in wide surprise, and, "Como?" he muttered thickly. "Como? How—how?" which ended with a groan as of a bull at the thrust of the matador, and his body slid down further in the chair. But the eyes remained open and full of wonder and the fear of death.

I leaped to seize the madman. But he pointed the pistol at me. And, as I stood back, the full madness came upon him. He tore the amulet from his breast, a gruesome thing, like a dried mushroom threaded upon a thong, and thrust it in Gabriel's face.

"Look at it!" he grated hoarsely at him, for his voice could not shout. "Look at it and remember! The other one is eaten away with the rest of my face; but this dried one they wouldn't eat. Can you see still, Zambo? Look! Look at the thongl Your own thong—with the ear of Joselito threaded upon it! Can you remember yet? You said it would take long to die. Look at me and remember."

"Deus da Graça!" I cried. "It is the dead one!"

He looked at me and grinned recognition, and turned then again to his leaping and thrusting of that horrible dried ear in Gabriel's face.

"He knows me," he hissed. "Theophilo knows. Look at my face, Zambo, and know me too. Not the smallpox, Zambo; not the rotting sickness. Ants! Formigas do forno, the fire-oven ants of an inch long!

"They followed me, those fiends of the Chima jungle. Though I lay in the slimy creeks with the caimans, they smelt out my trail. In an ant tree I took refuge! In many ant trees! Madre mia, what a forest of ant trees is in that jungle!

"Look at my face, Zambo, and judge what I have suffered. What the ants left, the blood poisoning completed. To die of a wound in the stomach is no suffering at all. And you will surely die, as you promised, even though it takes longer and hurts more. But that—ho-ho—that is your misfortune.

"Many more things I have to tell you, Gabriel, who will soon be an angel of the devil. But your people press round. I must chase them off. Wait for me, my angel. Do not die yet. Swiftly will I chase them and tell you then all the things that are in my soul."

It was time and high time for him to turn in his own defense; for the men of the sitio crowded the space in front of the veranda, waiting only the necessary man of initiative to lead them on to a rush. Joselito reached under the stricken man's thigh and took the other pistol that the people knew so well. Standing then with both of them in his hands, the pair of deadly things which had been his father's, he stepped to the front of the veranda and croaked his defiance at the crowd.

And as the pistols pointed, the men whom they singled out melted away.

In an incredibly short space of time I could see canoes being launched by ones and twos and speeding away from that place. Presently only Indians of the sitio stood in the open space before the veranda. Of the creatures of Gabriel not one remained to take vengeance for their master who had been.

Which after all, senhores, is not to be wondered at. For when a man has schooled a people to be ruled by fear, they will naturally be afraid of any other man who vanquishes the first. And why should men fight who have nothing left to gain and only their lives to lose?

So, as the time passed, and with it the frenzy of Joselito's rage, I was able to talk to him and calm him down, and presently able also to lead him away. And I got him something to eat, which he much needed; and thereafter I got him to sleep, which he needed much more.

Gabriel o Angelo died two hours later in great torment. But I think, as Joselito had said, that it was not even a small portion of what he himself had suffered.

So that was the end of that matter.

Later Joselito told me the full tale of his wanderings in the jungle and of his many escapes from the Chima wild men who hunted him by scent. And terrible was the tale. But all that has nothing to do with the business in hand of procuring rifles, which are a necessity for the finding of the gold; or rather, of the getting of it. Of the finding, Joselito told me also. The place is known to him without any manner of doubt. The gold is easy to get, too, being free-washing sand of the river bed.

All is easy, but the Indians. The Chima, who are as relentless as wolves. For defense against them are many men needed; and for the men, rifles.

And for these rifles, senhores, will there be gold. Many fat quills for each gun. And that is the only trade for which there is a value today in all the Rio Içá. And Joselito, my good friend Joselito, has told me that he will give his trade to no other but me. And since he is now very surely the king of all the upper Içá, the trade will be good and the price very good indeed.

Is it not then better to prevent those rifles from going up to make a revolution at Quito? Assuredly, senhores.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.