RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

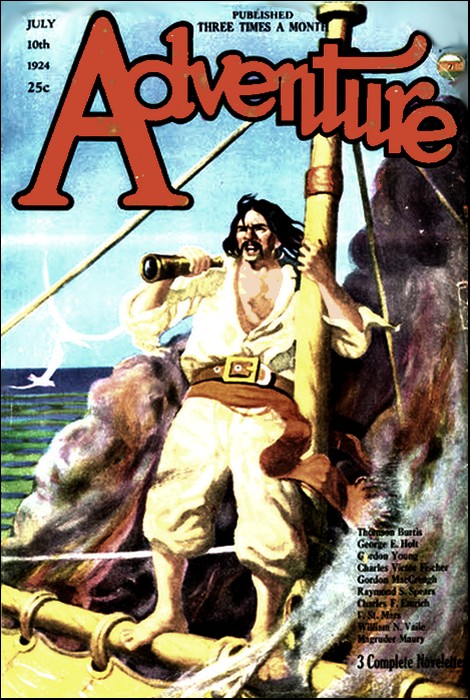

Adventure, 10 July 1924, with "The Inca's Ransom"

RAIN in ropes, interspersed with sleet in hurricane sheets, smashed down on the high and desolate ravine known as the Barranca del Brujo, the Wizard's Gorge.

That great zigzag gash in the mountain flank reared its perpendicular cliffs of cold gray sandstone fourteen thousand feet high in the thin air—which was a good six thousand higher than where vegetation died, and was cold enough to feel like the very top of the bleak world. Yet it was dwarfed by the towering mass of the great ghost mountain which loomed blurry and white and vast over its twisted head.

Chocque Chullunkaya, the Indians called it. The Golden Snow. But why, they could not say. Their fathers had called it so. That was all they knew. Twenty miles distant at least it was from the gloomy gorge; yet it seemed to impend over its very brink, as if hungry to hurl its whole mass bodily into the chasm. The storm found its wild birthplace on the vast white slopes of the place of ghosts; and as it sprang shrieking from its caves and crevasses it lifted the snow in great blankets and whirled them down to plaster them like paste against the upper face of the great spur that thrust itself in a thin wedge into the landscape.

Like a letter V it was, thin and steep and towering. At its far foot, much too tumultuous to freeze, the mountain torrent ran that had cut the gorge in the early beginning of things. Five miles along the northwest face it raced to double round the sharp, unyielding nose of the wedge and go roaring and leaping almost five miles back on the lower side before it settled down to a more orderly onslaught on the spur of Sachsahuaman and the valley of Villcamayu, where the massive masonry of the ancient Inca city of Cuzco still defies the elements, as intact as the day it was raised—which distant day no man knows.

High up on the sharp edge of this great V a jutting excrescence impended hungrily over the gorge; an outcrop of pink and pale-green dolomite which had withstood the erosion of the years and hung now exposed and threatening over the torrent. On its flat top, worn smooth by the treading of ages, scoured clean by the lashing rain and swept smooth of snow by the fierce wind, a tiny crimson tent clung. Not more than three feet high at best, and perhaps two and a half feet across its irregular base. Just such a conical mound as might be made by draping a crouching figure with a red blanket.

At long intervals the thing moved; shifted position stiffly; and then for a long interval again remained motionless. The wind tore at the crimson covering and hurled its sleet against it like shot, molding the weather side to a stiff cast over a skeleton frame. But the ragged cone clung as a limpet clings, apparently by suction. Till at last the storm devils withdrew in disgust and retired temporarily for a rest; and then the thing moved again.

A slit in its top opened, and there protruded from it a head. A skull rather, with ancient parchment stretched over its bones. Parchment that was old and brown and bald and cracked in a thousand furrows. Over the bridge of the great eagle nose and the sharp angles of the high cheek-bones it looked as if the bone were surely about to break through; and the tight-drawn slit of the lips gave no indication that they could ever open and permit speech to issue forth. A dried trophy that might have been in the collection of some head-hunter.

But the eyes! Deep-sunken, of course, in their withered sockets, and shaded like windows under low-hanging eaves of osseous bald brows. Yet like windows lighted from within; extraordinarily bright and piercing and alert. Eyes uncannily young in that withered skull.

Like an aged tortoise the head protruded from its covering and craned a lean neck to gaze unwinking into the teeth of the storm. Then it nodded slowly and withdrew itself once more to wait.

This was Winter's last raging effort; and in some queer way the wizard of the gorge knew it. By intuition or by second sight or by faith—or perhaps by that same instinct that tells a turtle or a ground-hog that Spring has arrived—he knew that the sun, whose hereditary priest and servant he was, would that day shine upon him after an absence behind the mists of five clammy months.

Rain or sleet or snow made no difference to him. He had been born in a lofty hut on the mountain scarp where the snow whirled in under the eaves and salted his mother's blanket with a fine white powder. Of his fathers and of their fathers none that he knew even a legend of had ever descended below the ten-thousand-foot levels. Tremendous lungs and immunity to cold, therefore, were his heritage almost as much as the half-forgotten lore of the ancient priesthood. So with amazing hardihood and sublime faith he waited.

And since faith can move mountains, the storm presently exhausted its rage and passed. The snow devils retreated sullenly to their caves. The rain and the sleet spat their final fury as warmer air, rising from the vast plains beyond the Cordillera, whipped over the snow peaks and scattered the concentrated moisture. The heavy clouds first thinned; then were rent in ragged sheets which raced off down the valley; and presently the sun streaked through and a little later found a wide blue patch and sent a long, watery ray to find the outpost rock where his servant waited.

Incredibly old though he was, the priest sprang to his feet with almost the alacrity of a youth. He threw the faded crimson poncho from him and stood naked in the thin beam. Lean and withered and stringy; yet erect as on that distant day when he was first initiated. He threw his long arms out to his god and stared him unwinking in the face as he chanted the greeting:

"Illappa. Inti, Ccama arajpacha. Achachi-pa jampatinya. Lord Sun, Light of the Heavens! Thine ancient servant gives thee adoration. Thy servant calls upon thee—" and so on in a long, quavering chant which came to an end with the indomitable promise of service to come:

"Thy servant makes oath before thee to protect the sacred trust. To find the accursed writing of the treasure that must never come to light. Thine ancient servant swears. Help thy servant, Lord Sun."

It was a prayer and an oath such as any young man in the full pride of his youth might have made. But the ancient priest was the last of his kind. All the others had gone before him. The sacred stock had run dry. There was no stout son to take up the trust. Gone were his people from the face of the earth. Of the Incas-yocca remained only a not very authentic history and some broken shards—and the wisdom of his fathers which had come down to him. Yet the sacred trust must be guarded inviolate.

THIS trust was the ever-recurring story of Inca treasure. All the world knows that the priests of the Inca, when they found that they were helpless to defend themselves against the ravening gold-lust of the white conquerors, buried or cast into their sacred lakes vast treasures of the metal that attracted these ruthless strangers to their land.

Half the adventurers of the world have believed that legends of the casting have persisted through the years among Indians and witch-doctors and half-breed descendants of the conquerors, and have hoped some day to trace the forgotten clues to some of the lost hoards.

The fate of some of them has been to try. Some have been bold enough to go out on a lone prospect, following the trail of a rumor. Some have been lucky enough to get possession of a tattered chart left by some other earlier adventurer. Some have been wealthy enough to organize an expensive expedition. Some have even married squaws and have been taken into Indian families.

And all of them—or very nearly all—have been disappointed. They have hunted and dug and fished; and, while a few have been lucky, the sum total of their findings has amounted to less than a hundredth part of what has been spent in the search.

And why? Because of the sacred trust. The gold was accursed, the ancient priests declared. Because of it their country was laid waste and their people slaughtered by strangers. Therefore was the veil of the huaca, the tabu, laid upon it. Never must it be spoken of nor shown. And, though the people of the Inca have vanished and their civilization is little more than a rumor, and their language has utterly disappeared, still the ancient tabu persists.

Those who know—if they know anything—lower their eyes and become wooden-faced and sullen as soon as treasure is mentioned. The curse of the tabu holds even among the descendants of the peoples who used to be the Inca's slaves. There have been adventurers of many nations who have met Indians who, they were convinced, knew. They have bribed them; they have married them; they have even tortured them as the first conquerors did. But no Indian has ever told.

All that has ever been found has come from the stories and desultory records that have been handed down through the descendants of the conquistadors.

AS HAD happened to the old wizard of the gorge. In the lake that the mountain torrent formed far below his outpost rock a great treasure had been sunken; a hundred llamas loaded with gold. In some manner a rumor of the sinking had come to one of Pizarro's adventurers, whose memoirs had come through devious handing-downs to a half-breed descendant who, during the last Fall, had arrived with assistants and with equipment to drain the sacred lake and redeem the gold that was accursed, huaca forever.

Him the ancient priest had sacrificed to the sun god. But the document, the knowledge of the secret, remained. As long as that knowledge existed the secret was in imminent danger. Therefore must the knowledge be rooted out and destroyed forever.

Then the Winter had shut down on the scene with the suddenness of the first Andean snowfall and had imprisoned the guardian of the gorge in his cave for four long months. Like an aged turtle he had returned within its depths and had subsisted on his store of broad beans and frozen potatoes, isolated from all humanity and buoyed up by his indomitable resolve to find and destroy the last shred of evidence that threatened his sacred trust before he should go to join his fathers. And now he was making oath before his god to take up the search as soon as the trails should be passable.

In Cuzco, the new city that had sprung up under the shadow of the ancient Inca capital, the half-breed descendant of the old Spanish swashbuckler had lived. That was all that the wizard knew. In Cuzco, then, among some thirty thousand inhabitants the accursed document must be sought.

Rather a hopeless task, it would seem, for an old man, feeble and illiterate and alone—and above all an Indian, a person to be spurned and thrust aside. Yet for the old wizard not quite so hopeless as it might seem. His method was strikingly simple and direct.

With the perfection of faith he prayed to his god to clear the trails with speed; and the god heard him and shone with all the sudden ardor of the Andean Spring. Within a few days the tortuous goat-track that had once been a well-kept Inca road, and which passed the very front door of the ancient cave of mysteries, was clear of snow. Clear enough for the old wizard at any rate, to whom snow meant nothing. He scrambled along the sheer mountainside with an astonishing agility and with an uncanny memory for crumbly places now covered with the treacherous honeycomb slush of Spring.

Cuzco city lay twenty miles away at the head of its historic valley of Villcamayu. Yet in some wonderful manner the old man arrived there. With his bowl-shaped felt hat and his patchy crimson poncho and baggy llama-wool pants and grass sandals he looked just like any other old Aymara Indian shuffling about the market-place.

There were white men and mestizos who would have given large sums of money to know that they were looking at one of the last of the priests of the sun; for persistent legend had it that secrets of vast treasures had been handed down from father to son along the sacred line. But nobody paid any attention to the old man. So decrepit did he appear even that nobody kicked him roughly out of his way.

The wizard came to a halt before one of a row of women who sat behind brilliantly colored blankets spread upon the bare cobbles of the market-place, upon which were displayed little piles of garden truck, potatoes and okka and quinoa and chuno. The woman looked at him once and then hastily made up a package of coca-leaves, which she thrust into his hand.

"Auquiha," she muttered. "That my father cast the eye upon my poor produce."

The wizard extended a shrunken claw from under his poncho and held it a moment, palm down, over the blanket. After that a clamor ran all down the line, begging the old man to receive their gifts. He passed along the row of blankets, and what he needed for his sustenance he accepted and gave a brief flash of his hand in return.

A young priest of the Franciscans, assistant to the good father whose perquisite it was to bless the stalls of the market with a dash of holy water and to receive therefor the customary dole, asked indignantly of his Indian servant who carried his bag who might that old man be over whom the people made such a fuss.

The Indian immediately became a bovine incarnation of dullness and said that he did not know. How should he know? It was doubtless some beggar to whom the women gave charity.

Yet a little while later, to another Indian, a youth who asked him the same question, he replied:

"That is Mamu the Soothsayer, the wizard of the Chocque Chullunkaya. Go, boy, and stand in his path and hope that he may look favorably upon you."

And the youth said:

"But Mamu the Soothsayer is dead. My father, who is old, told me that no man had looked upon his face since he was a youth. Besides, why should I, who have been to the mission school and can read my own name, crave the favor of an old man?"

So the other Indian very naturally cursed him for a pert young know-all and went his way. And the youth, being a youth, with all the curiosity that belonged to his age, went and planted himself in the way of the old man. And the old man, seeing him to be a youth, alert as well as idle, laid his withered claw upon his arm and looked with frightening keenness into his eyes from under his bald bony brows and said:

"Son, I am old and feeble; alas, very feeble. It is necessary, therefore, that you find out for me the house of one Diego de Soto, who went not so long ago into the mountains and never came back. I wait yonder in the sun. Go, and return with speed."

So the boy, who would rather have loafed the pleasant morning away in the market-place, went to inquire about the de Soto who had disappeared, and grumbled at himself for going. Still, he went.

So the whole day passed. The wizard withdrew himself into his poncho tent and waited, crouched unnoticed under the blue-and-pink tiled wall of the house of Natalia de la Vieja, the chela woman who had made her fortune through selling German anilin dyes to those who wove blankets and ponchos. His knees drawn up to his chin, and the little mound of faded crimson poncho crowned by a shapeless felt hat, he was just an old Indian asleep in the sun.

Evening came, but no youth. Still the wizard sat motionless—waiting. Time meant less to him even than to the elements. Darkness came, and still he waited, unruffled, confident that his behest was being carried out. Then at last came a man who made obeisance.

"Auquiha yatina, Father of Knowledge," he said. "My son still seeks, having gathered the help of his friends. Through the night they will seek. Let the wise one come to my poor house and rest"

So the old man went with him and huddled in a corner of the hut, silent and mysterious—and waited. Throughout that night and the next day and the next night, wrapped in the mantle of his concentration. In the following morning the boy came. He was drawn-looking and weary.

"My father," he reported, "the man who was Diego de Soto lived in the street called del Coronel, in the third house from the end. There live now his woman and his mother and his woman's brother with his woman and eight children."

Mamu the Soothsayer half-lifted his head from his knees, so that just the piercing eyes gleamed over the poncho's edge.

"Good," he said. "It is now necessary to bring me a servant of that house."

The youth looked askance, and then mutinous.

"But, my father—" he began.

The wizard interrupted him.

"Go," he said.

So the youth went. And presently there came an Indian, wondering and sullen, who said that he was a servant in the house of Diego.

Once again the old wizard half-raised his head.

"It is necessary that we be alone," he said.

Without argument the owner of the hut arose, and his woman gathered up her two children and the inevitable blanket bundle of odds and ends which always lay ready to hand; and they went out and left the wizard alone with the servant of the house of Diego.

Without preliminary or explanation the wizard proceeded to give his inexorable orders about the "writing upon parchment" which must be found—somehow, some way—and delivered to him.

The servant began to raise the first of a hundred objections. But the wizard said simply:

"I wait here. It is necessary that you use speed."

The servant became aware of just two eyes boring into his soul from the dark space between the brim of the felt hat and the drawn-up knees under the poncho. So he went.

It was evening again when he returned with the information that there had indeed been a writing upon parchment, but that the Diego who had disappeared had taken it with him to show to a white man who was going to make his fortune for him; and neither Diego nor the writing had been seen since.

Old Mamu the Soothsayer squatted silent and motionless for an hour while the servant squirmed in uneasiness before him. Then he lifted his head and made a prophecy.

"It will happen," he spoke out of his wisdom, "that that white man will come again. Perchance soon; perchance not for many years. Perchance alone; perchance with others. It is not known to me at this speaking. But surely will he come; and he will seek servants and men with mules to go with him to the Barranca del Brujo. When that day comes let word be brought to me with speed."

Then he rose for the first time in three days from his corner and wrapped his poncho about his aged limbs and went from that place. He had reached a point where he was helpless. It was necessary now to make a big magic and to cast the omens and to pray to his Lord Sun for guidance against that coming.

For he was shrewd psychologist enough to know that, if that document about treasure still existed, there was no power on earth which could keep some hardy white man or other from reading therein the call of the Red Gods and embarking upon so joyous venture.

AS A matter of fact the white man was at that moment in far-away New York, engaged in that heartbreaking preliminary which faces all would-be adventurers—the raising of the necessary capital. He sat in the library of a coldly cautious coffee king, reviewing in his mind all the arguments which he would put forth to meet the objections that successful business men always produce against all joyous ventures that can not be reckoned at a safe six or ten or fifteen per cent.

Some of the arguments he had ready to hand. He had learned them by experience; for he had been to other successful business men before, and he had learned that business minds all ran in the same groove.

Whatever had not been done by somebody else before and proved to be profitable was to be regarded with disfavor. Until there came the thousandth man with vision, having also knowledge enough about matters outside of his own direct business to see the possibilities and take a chance. After which the rest of the herd would follow madly in the successful one's wake and try, by using all the tricks known to their craft, to catch up with the far-sighted leader.

In this case he had progressed beyond the first, most difficult, barrier. His experience had taught him the necessity of starting with a dramatic story to capture his prospective "angel's" interest; and he had learned well enough to succeed during a previous interview in interesting this financier to listen to his proposition.

He had survived the period of fretful waiting while the cold man of money was "thinking it over"—which meant that the man had shown the proposition to some of his friends to pick holes in. Now at last had arrived the second interview.

The white man was hopeful—he had at least hooked his big fish. Remained to play him.

"Well, Mr. Templar," said the big man genially, "I've had your document verified, and I'm assured it checks up with what you say. I believe it to be genuine. But it is more than vague about the position of the lake. Now go ahead and convince me, if you can, that you know where the lake is, and that the gold was actually dumped into it."

Templar was ready and full of the enthusiasm of youth. He ran his fingers through his tousled, mud-colored hair far inspiration.

"All right, Mr. King, I'll spill the yarn; and I want you to try and keep in your mind that this isn't any fool pirate-treasure story. You're satisfied that the parchment is genuine. Good. You'll admit then that it's reasonable to believe that it should have come down in the family till this Diego man had sense enough to read it?"

Mr. King nodded; but was ready with his objection.

"I hope you'll admit, young man, that it's reasonable to ask, why didn't anybody else read it during all those years and go after the boodle?"

"Surely. I'll admit they must have. But what would they know about the location of a nameless ravine and a little mountain lake? It was all too vague to do anything with—and they were all maņana folk.

"Now this Diego was a breed. Half-Indian. From that side of it he knew that there was this mysterious gorge with a tabu on it and that an old witch-doctor lived there who made magic with fiends and kept the other Indians scared stiff of the place. So he had sense enough to connect two and two."

"All right. I'll consider the point made," said Mr. King with a legal reserve. "But what evidence have you that it was the right place?"

"Well, gee whiz—" the young man ran his fingers through his hair again—"I told you before. This Diego man got in touch with an American who was down there for some reason—a couple of jumps ahead of the sheriff, I imagine—and he put up some money and hired me as engineer, and we went right there and saw for ourselves."

"Ah!" Mr. King was alert. "But what makes you think that the gold was there?"

He leaned back in his heavily padded chair and lighted a cigar with a smile indicative of having put a poser.

The young man grinned cheerfully back at him and took a long breath for his final assault.

"I've got nothing but my word for the rest, Mr. King. You can check up on all the foregoing at no very great expense by just sending your own representative with me, just as though I came to you with samples of a mine. But I hope to convince you that I'm not lying."

Mr. King just nodded for him to proceed.

"Well, lemme describe the locale, first. There's the big deep ravine; shaped like a V, it is. Melting snow from the mountain up at its head forms the little river, which in turn forms little lakes as it descends. Now there's a great wedge of a cliff of metamorphose sandstone, a quartzite formation, harder than the rest, which made the stream cut round it and form the V. 'Way up on the cliff is the old witch-doctor's lookout station, a dolomite outcrop. Back of that again, sheer along the cliff face, is an old Inca road, and back of that again is the cave in which the old man lives."

Mr. King was leaning forward in his chair again, watching the young engineer's face with the interest of a hawk. Templar saw that his story held the man, and his heart thumped in his throat almost loudly enough to break the flow of his speech. He swallowed hard to get a hold on himself and continued:

"Now then, here's what happened. I started to cut off the inflow—the lake is right under the old road, you must understand—and to siphon the thing dry. Well, right from the start the old witch-doctor laid himself out to obstruct. He scared off our peons. He busted the flume. He—at least I think he did—he got rid of Diego. Anyway Diego started out to kill the old man, and he never came back."

The financier was gripping the arms of his chair, and his cigar had gone out.

"And then what?" he prompted as Templar paused to marshal his thoughts.

"Well, then—" Templar grinned in rueful reminiscence—"he beat me hands down. He turned an underground river into my lake."

"How d'you know that?" snapped the hard man of business.

"We went up into the cave and saw, that other white man and I. There was an awful chute, wet and slimy and spooky, 'way back in the bowels of the earth. The old witch-doctor was there, putting a spell on us or something; and, by golly, I believe it worked. Anyway the other man made a grab for him and slipped, and slithered into the mill-race, and in a second he was gone. In one swoop down that smooth, oily chute into the black bottom of nowhere. Then—then I got scared and ran."

There was a long silence. The cool man of far-sighted affairs slowly relaxed in his chair like a trance medium coming to life. At last, almost in a whisper—

"And then?"

Templar had no skill in spellbinding. But his very lack showed the straightforwardness of his story.

"Well, that was all," he finished lamely. "But that's how nobody else knows about the thing now but me. And that's why I believe—I mean, on account of the old wizard's determination to stop us—that the story in the parchment is true. I believe there was a huge load of gold coming along the road to pay the ransom of the Inca when Pizarro murdered him. And I believe that the priests dumped it right there. And I know that I can get it; 'cause now I know how I was beaten last time. There's no trick to cutting off the water supply, and then I can guarantee to drain the lake in a month."

Mr. King lighted himself another cigar. He had still an objection to make; one which seemed serious enough to wreck the whole project; and he was businesslikely brutal about its expression.

"Well, young man, I'm inclined to believe what you tell me. I don't think you could invent all that description; and your story sounds good enough to gamble on. But—from what you tell me, that gorge you speak of must be one of a nasty place, and I'm too old to go gallivanting about over the top of the earth on a wild treasure hunt. So if I grubstake you, as you call it, how am I to know that you won't just up and skip with the expense money?"

Templar was not hurt, or even offended—he had been meeting these men for several months. His answer was ready.

"Good enough, Mr. King. Your objection is sound, but not insurmountable. I come to you as a mining man. Now suppose this was a mine and I went to any promoter with samples. In the regular course of procedure he'd send his own representative with me to handle the funds. Half the mines in history have been opened up that way.

"Well, you can do the same thing. Don't give me any money. Send your own man along with me—anybody you want to trust. Let him hand me the expenses as they're needed."

The financier smoked furiously for some seconds. He could see no flaw in that proposal. Then he announced his decision—this one did have the faculty of making up his mind without calling a meeting of trustees and directors.

"Young man, you've sold me on that last. That sounds fair enough for anybody—provided my man can keep his end up once you've got him out there alone. But let that go for the present. Now tell me. How much will it cost? And how much do you expect for your end?"

Templar with difficulty restrained himself from grabbing his hat and throwing it up in the air and yelling. Yet in the midst of his exultation he was unable to restrain the reflection that comes to all men who risk their lives in the far corners of the earth in the pursuit of fickle fortune, and then come home to comfortably entrenched capital to look for "front-end money" to exploit their hard-won findings.

"Oh, I know the rules. Grubstake money takes half; and then five or ten per cent, more to hold control. I'm in no position to kick; and I bow before grubstake law. I dig up the knowledge. I do all the work. I take all the risk. You gamble about fifteen thousand dollars and take the better end of a split on some few millions profit."

The financier took no pains to restrain a grim smile.

"To him that hath shall be given," he quoted. "But why fifteen thousand?"

Templar was on sure ground here. He gave his details snappily and in short order. He was quoting an estimate for an engineering job now.

"About seven for equipment—that's cheap, 'cause some of my old pipe-line will be lying there and must be usable. Three in reserve in case of accidents; and five for expenses—that item comes heavy 'cause I'll have to take white labor, say four men, 'cause I'll never be able to get Indians to stay on that job.

"And what's more, if you're afraid I'm going to double-cross your man when I've got him out there, let him pick his own crew; friends of his or yours, if you like. They don't have to be horny-handed sons of toil. There's going to be no heavy labor involved in the thing; nothing that I wouldn't do myself. All I need is a little help."

The financier drummed with his fingers on the arm of his chair, reviewing in his mind the scanty list of people he had met during his business career whom he thought he could trust. Then he made his decision with the finality and swiftness which had placed him where he was in the business world.

"All right, young man; I'll play. I'll give you my nephew. A few months away from the bright lights will do the young scoundrel good. He's never done anything but play the ponies and run with a bunch of shady men and fast women. It'll be cheaper for me to send him with you than to pay his phony checks.

"Now, I'm going to be busy, and I won't have the time to go into details of this thing with you. So I'll send my nephew to get in touch with you, and you can make all further arrangements with him. You make out your papers and contracts with him, and he'll report to me whatever may be necessary."

Templar was not enthusiastic over the thought of shepherding a young waster of the bright lights. But no would-be adventurer who needs financing is ever in a position to pick and choose. Templar was glad to accept any terms. Though the sour reflection grew as he went home that there was a fine irony in the fact that this careful man of business was willing to trust a youth whom he himself condemned as a scamp, rather than himself, whose record was one of clean, hard work, simply because the former happened to be a relative. But such is the way of hard-headed men of business.

But for all that as he went down the street with long strides and began to add architectural details to the castles he would build with his half of the treasure, he suddenly did grab his hat and yell as he threw it high in the air.

SO IT came to pass that the wizard's prophecy was presently abundantly verified, to the great wonderment and awe of the peons of Cuzco marketplace. There came to him in a great flurry of excitement no less a person than a cacique, one who had acquired comparative wealth among his people through the cultivation of coca-leaf. He found the wizard crouched at the entrance of his cave, wrapped in his poncho, head and all withdrawn, as was his wont; a red mound of mystery in the sun, crowned with a battered, bowl-shaped hat. Without movement or inspection the wizard's voice came from beneath the covering.

"Be welcome, Jottua, cacique of Songo."

Whereat the cacique greatly marveled. How was he to know that the stones he dislodged as he scrambled along the precipitous path echoed like gun-fire back and forth along the top of the gorge and heralded his coming while he was still a mile away, and that the wizard from his vantage-point at the very apex of the V could peer between a split boulder created long ago by his forefathers for that purpose?

"My father," he began to report in an awed voice. "The prophesy is come true."

"I know," said the level voice beneath the poncho. "White men are in Cuzco."

The cacique clapped his hand over his mouth.

"Ow," he mumbled. "My father knows ail things. It is true. In the fica of Gomez they are, seeking mules to carry packs. Five of them. One who speaks Spanish, and four who are drunk."

"I know," repeated the wizard, and sat silent, motionless and mysterious.

It was one of the very first teachings out of the lore of the ancient priests, his forefathers, that a mantle of mystery covered many a period of indecision and thought—which is a much more effective trick of psychology than the custom of many civilized wise men who endeavor to make thinking time under cover of a flood of words. Another gem out of the observation of the ancient soothsayers was that if one sat still long enough the other would eventually speak in the sheer need of breaking the uncomfortable silence and would supply further information which could be preempted as no new thing.

The need with the squirming cacique became insistent. He dared to intrude upon the abstruse meditation of the seer with a clumsy offer.

"If my father needs the service of men those of my plantation—"

The seer interrupted him with a hasty negative. Men, open resistance, was the last thing that he desired; for then would the secret of his gorge be advertised to the world. No; he would have to contrive—somehow, someway—to outwit these white men. Five of them, with all modern science at their back. And he, a lone, feeble man with nothing but his native wit and the half-forgotten wisdom of an ancient cult.

Yet the secret of that sacred trust must be kept. It was the one dominating force in his life, as it had been in the lives of his grandfathers before him.

In some manner, quietly and without fuss, these white men must be persuaded that they followed a chimera, that there was no treasure—which would be difficult in the face of that accursed parchment. Still, somehow they must be dissuaded. Or if that should prove to be impossible—they must be utterly destroyed.

The old soothsayer made the gesture that signified that his visitor might go—it was evident that no further information was to be had. The cacique made obeisance before the huddled mound of mystery and went, unblessed, unthanked; yet satisfied with the importance of a great story to be told in the market-place about the supernatural wisdom of old Mamu the Soothsayer.

When he was alone the old man rose wearily and withdrew into the inner compartment of his cave, the chamber of mysteries where the ancient stone gods lived, and set about casting the omens of the coca-leaves to discover what craft an old and feeble man might devise against these terribly persistent white men whose strength and whose knowledge were so much greater than his own.

FOUR days later the white men arrived in the gorge below. The one who spoke Spanish and the four who were still drunk. With them came a train of mules bearing lengths of pipe and timbers and planking and tools and tents and all the mess of gear that is required for a camp in the wilderness where nothing grows at all.

The one who was sober left them all to their own devices while he jumped eagerly off his saddle mule and strode up the slope to the lip of the silver-surfaced lake in the depths of which lay his hopes.

He stood on the brink and made a quick survey of the scene; and a pleased grin began to chase the lines of harassment from his face. Things had not changed much since he was there last. The gorge was as gloomy and as grim and as desolate as ever.

Nothing other than the elements had endeavored to undo his work.

The flume that he had built to cut off the inflow from above had broken down in a few places, and the water splashed merrily into the lake. It was inconsiderable; yet from the lower end where he stood a small river roared out through the gap that he had blasted. The underground river was still doing business at the old stand. But that caused him no anxiety; he knew where to cut that off now.

His old pipe-line was almost intact. The pump had rusted beyond repair; but he had foreseen that. The proposition on the whole was very favorable. Encouragement, for the time being, took the place of worry, and he stepped down the rubble-strewn slope and set to with a will to direct the disposal of all the gear.

It was not so easy as it might have been. Each of the half-dozen mule-drivers bawled questions at him at once; and since he could not answer them all at the same time, they sat down to take things easy and let the mules wander while one of their number was being shown what to do.

Or when the busy white man yelled at them to get busy themselves and unload certain gear at a certain point, they would catch the wrong mule and deposit its load far from the spot where it was needed. Even in a narrow ravine a perfectly awful amount of labor can be expended in removing sundry mule-loads of tents and things from one place to another place where they should be set up. Templar had made camps often enough to know that he wanted a tent-mule, for instance, unloaded within three feet of the spot where the tent was to be set up; and he sweated in spite of the chill elevation as he wrangled with the mule-men, who were only one degree less stupid than their beasts.

The other four were of no assistance to him whatsoever. True, they could not—with perhaps one exception—make themselves understood to the drivers; but not one of them made the slightest effort to use his two hands and carry a package. For one thing, they were still wandering in the fog resultant upon their celebration of arrival in a country where prohibition was not; and for another, they were too appalled at the desolate prospect before them. They sat about on convenient boulders, washed-out and headachy, and mumbled their feeble disgust to one another while they absorbed consolation from their fat hip flasks.

"Holy gee, what a hole!" they told one another. And, "Sweet poppa, do we cotta live here a cola months?"

The desolate, forbidding ravine was in point of fact considerably different from the gay street of a million lights which was their ideal of existence.

However, Templar contrived to get all the confusion of gear stowed in due time, and paid off and dismissed the mule-men—who were glad enough to get out of that haunted place. Then he found time at last to stand with his hands deep in his breeches' pockets and feet wide apart and make a wry-faced survey of his crew in the environment in which they were going to work for the next few months. As he looked, the harassment and worry stole back into his face in concentrated form. They were a sorry-looking crew. On the steamer they had seemed not so very inferior to the nondescript gathering that travels on those West Coast boats; but here they surely did not fit

Not a one of the four showed the slightest promise of being a useful worker. But then, of course, they did not pretend to be. Templar had enlarged upon the fact that no really hard labor would be entailed; and these cronies of the nephew—men whom he could trust—had come along on a treasure-hunting picnic. They argued that they could easily put up with the discomforts of camp for a few months in return for the "share" of the gold which would accrue to them.

There was King, the nephew, who was just about what might have been expected from his uncle's recommendation of him. He was dressed, like all of them, in the prescribed camp costume, in nice new khaki shirt and cord breeches and high-laced boots. But he looked too much like what-the-young-man-will-wear-in-camp-this-Summer. In keeping with his costume was a face equally immaculate, bloodless and weak, physically and morally.

"Hah! Looks like a darn good dancer," was Templar's comment.

Then there was Baboon, a geologist. Tall, slender, and not ill-looking. Nothing actively bad about him. In fact the only visible thing that could be determined against him was that he was King's friend.

The other two were from a different class.

Docket, big and burly and densely ignorant; though with a certain natural cunning in his little eyes; running a little to stoutness from an easy living which he had not been brought up to. No mean portion of that easy income had been derived from tips on sure-fire winners which he had furnished for the investments of hopeful souls like King's.

Templar wondered how it came about that even a young rake like the financier's nephew could have selected this gross person for a companion. He did not know much about the life of a rake, or he would have guessed the common old story of the racetrack man who "had something on the young blood." As a matter of fact, the man held so many notes of the nephew's which the uncle must not know about that he had been able to force his client's hand and insist on being let in on the present gamble for fortune.

Then there was Marty—he had no other name—he was Jim Docket y's tout—and looked it.

A sorry looking crew indeed. Not to be utterly condemned, perhaps, in their proper sphere. But for an engineer with a job requiring manual labor they were distinctly not in the best of form.

Yet Templar—being but a young man with a project which needed finance—had not been in a position to pick and choose. The financier's nephew had the right to select his own men; and he had picked, as had his uncle, people whom he thought he could trust.

Templar's wry smile slowly contracted to one of ruminative worry. He had seen men herded together in close association in camps before. In good camps; and he had seen them go to pieces under the strain. For man, being a gregarious animal, is designed to live together in herds—not isolated by twos and threes together.

This was not going to be a good camp; and he had told them all so before they started. But their conceptions of a camp had been derived from a Saturday afternoon's automobile picnic. Templar looked them over and wondered. Very seriously did he wonder—even about himself.

His face was almost grim as he squared his shoulders and braced himself to face the first unpleasant task. He stood before them on wide-spread legs and delivered the little speech which he had thought over so often as he bad seen the necessity grow.

"Well, feelers, we're here. And here we're stuck for a couple of months. Tomorrow I'll tell you how we're going to set about the job. But there's one point I want to make clear right from the start. You feelers loaded up a mule with four cases of hooch to bring out here. Well—that mule didn't come!"

He waited for the outbreak. But the only immediate effect of his announcement was an incredulous dawning of understanding on the fuddled senses of the four.

"That's right, boys," he repeated. "I ordered it. And I'll tell you why. The last time I was here two white men got killed and the whole job flunked just because they kept themselves soused. The old wizard who lives up there isn't any kind of a fool; and he beat me out hands down. This time I'm not taking any chance of being beat."

The sense of what he was saying began to get home. As is the habit of weak men, three of them began to stir up their courage to the pitch of remonstrance by first complaining to each other about this dictator's gall. What did he think he was? Who gave him the authority to pull that line anyhow? etc. The fourth, Docket, remained silent; but much the more dangerous.

Templar showed a rare discernment in realizing that he must establish his ascendency now or not at all. He raised his voice over the growing clamor, and his jaw began to thrust itself aggressively to the fore.

"One more thing. I know that all of you shoved a couple of quarts apiece into your saddle-bags in case the baggage should be held up. Now I've seen men killed on less than that in a desert camp. And what's more, I want to get down to work tomorrow. So I'm going to frisk those bags and bust up the reserve."

This time the three were dumb with indignation. But Docket rose and stepped not very steadily up to the engineer.

"See here, sport," he growled in a habitually husky voice. "Lemme tell yuh 't you've got one — of a naive. Who the blasted — made you a boss around here? Now I'm telling yuh there ain't no — white-collar engineer coin 'to take no quart outa my bags. So whadda ya goin' ter do about it?"

He teetered back and forth as he threatened with the portentous ferocity of his kind and present condition. Templar knew enough to exercise restraint.

"Don't be a — fool, Docket," he said. "I'm going to do it; and I'm going to do it right now; and you're too drunk to put up a scrap about it. You've got too much of a load even to follow me up to where the bags are. So quit."

The cliff wall came down sheer to the ravine bottom on the side below the wizard's rock. But on the other side was a steep slope strewn with rubble and loose boulders. The tents had been pitched on a more or less flat ledge at the head of this, close up against the opposing cliff, as a natural protection against possible flood. It was quite an awkward climb at any time.

Templar scrambled up, and Docket started to follow him; bent on rescue at any price. But it was true. He was too drunk. He succeeded only in slipping and floundering about at the bottom of the slope in a series of self-created avalanches, where the other three were able to join him and help to voice the loud indignation while their self-established chief methodically ransacked their saddle-bags and smashed one after another of their precious store.

He completed the sacrifice to efficiency and stood once again wide astraddle to look down on them.

"Don't get sore about this, feelers," he urged. "You'll think differently tomorrow. Now I'm going to fix grub for tonight. Tomorrow we'll lay out a schedule. And let me give you a tip. The sun will be gone in an hour from now; and, believe me, it'll get so suddenly cold that you'll want your tents and blankets. So the tip is to lay off those hip flasks so you'll be sober enough by that time to get up here."

But they only clamored in impotent rage and mouthed curses at him.

A poor beginning for a long and dreary job.

AND Mamu the Soothsayer, flattened out on his rock high above them like a lizard, watched these things with the keenness of the great condors that circled with endless monotony high above him. And the thousand furrows of his dried-out parchment face agitated themselves; and, as he watched, they deepened; and as he watched more, they cracked; and finally spread ever so slightly; till it might almost have been said that the wizard smiled.

For full half an hour the expression remained set, almost as if the withered parchment had no resiliency of recovery in it; and at intervals he nodded, stiffly as a lizard nods in the sun. Then the sinking orb slanted coldly over the saddle-back crest of the mountain of the Golden Snow and threw the shadow of it on a deep groove carved in the hard dolomite just before his face. And suddenly, with the miraculous elasticity that his aged joints seemed capable of, he leaped to his feet and flung out his wasted arms to his god in thanksgiving for what he had seen.

"Illappa, Illappa," he called. "Inti, achachi-pa arunianva. Lord Sun! Thine ancient servant greets thee. Thy servant sees the omen of the dissension among the white ones. Great is the Lord Sun. Illappa. Ccama arajpacha!"

His thin voice carried down to them on the thin air in broken, fading echoes; and then, just as the last whisper died away, the returning waves thrown from the upper cliffs enveloped them in an eerie wailing of crescendo shrieks till all the rock-bound devils of the bleak ravine howled at them, and presently reluctantly drifted on down the gorge, whispering and whimpering, and threatening to return as some projecting angle caught the sound and flung it back.

When he could make himself heard, Templar called down to the startled four, laughing at the alarm in their faces.

"That's him. That's the old boy himself saying hello to you. Come on up and take a look at him and get introduced. 'Cause you can bet your shirt that you'll see a heap more of him before you're through."

Docket, the big burly one, shuddered. He was ignorant enough to be densely superstitious and just befuddled enough to be wildly imaginative.

"Gee," he murmured as he looked affrightedly over his shoulders as if expecting to see demoniac faces grinning out at him from every dim crevice of the cliff. "Gee! Ain't that the limit!"

But he was sober enough now to climb the slope to the cheerful shelter of the camp-fire. And the other three followed him.

THE morning was by all standards of measurement quite the worst cold gray dawn after the night before that any one of the crew had known. The sun shone in a cloudless sky, as it

would do for the next few months without a break. But at fourteen thousand feet there is no cheerful warmth to the sun's rays; and it is appalling how cold a tent can be at night—and not one of the four knew how to make the most of blankets in camp.

A very sorry crew indeed they were when Templar woke them—and rewoke them half an hour later; and again an hour after that. In addition to the heads which they had legitimately earned, their limbs ached with the effort of trying to keep warm all through a chilly night.

But the aroma of coffee and bacon acquires a totally new and potent magic at eight A.M. and fourteen thousand feet. They dragged themselves out of their tents—lest these things, as Templar shouted to them, should grow rapidly cold—and gathered round the folding mess-table, a haggard and a very miserable quartet of treasure-hunters.

Templar showed generalship in substantiating his leadership while the others were yet in a chastened mood. While they ate, he laid down the simple rules of camp.

"Listen, fellows, and you can get some cheer out of this. I've looked over things, and I can tell you right away that there's not nearly so much of a job as I had expected. Quite most of my former work stands good. All it needs is a little repair.

"We've first got to cut off the intake. There's a half a week's work fixing up that old flume that you see there; and then there's an underground feed which we must dam off above. I'll tell you about that presently. When that's done, all we'll have to do will be to sit by and watch her siphon."

"What's siphon?" grunted Docket sulkily. "Thought it was a soda-water bottle."

Templar had to think a while in order to translate his explanation into words suitable for an intelligence quotient of twelve.

"Siphon means that that pipe-line thing you see running all the way down the valley goes up over the lip of the lake and forty feet under the surface—I laid it myself and I know. Well, when we've put in a couple of new lengths here and there and rigged a pump to start suction it'll keep on going of itself due to atmospheric pressure."

Docket was intrigued, though skeptical.

"D'ya mean," he asked obtusely, "that we don't cotta keep on pumping, an' the water'll just crawl up the pipe an' keep on goin'?"

"Exactly that," said Templar as patiently as might a teacher to a backward child. "It'll keep on going at about five thousand gallons per minute; and all you'll have to do will be sit by and see that nobody comes along and gums the works."

"Chee! An' then we gets the boodle?" piped up Marty.

"Not yet. The lake is more than forty feet deep. When it empties that far we'll have to join on another length of pipe. Two more lengths ought to do it."

Even the tipster's tout had vision. He could picture to himself a lake bottom paved with gold.

"Chee!" he murmured again. "An' then we kin go in an' scoop it up?"

Templar was not cut out for a teacher; he was a doer. He was getting weary of lecturing in this kindergarten language. He took a long breath.

"No, not yet," he explained. "The gold will have been covered over with a certain amount of sludge deposit. We'll have to dig a little soft dirt. I don't imagine there'll be any need to screen it, because all this Inca gold was in ingots. But what I want you fellows to understand is that there's no real hard work to tackle; mostly waiting and keeping watch."

"Huh, suits me," growled Docket, whose resentment about yesterday's affair was beginning to reassert itself as his vitality revived under the stimulus of the coffee and bacon cooked by Templar while he slept. "Suits me; 'cause I ain't figurin' on doin' no labor."

"Not a stroke more than your share," said Templar quietly.

Docket pushed back his chair threateningly and half-rose, employing the age-old bluff of the lower grades of intelligence, indicated by ferocious demeanor accompanied by loud tone of voice.

"Not a stroke more'n I want, Mr. White-Collar Engineer; an' I don't see nothin' in sight to make me, neither."

He seemed to be imbued to an unusual extent with that resentment against all persons of a more refined station in life which marks many of his kind. Templar was unable to keep the innuendo out of his voice.

"I wonder what gentleman mishandled you at some time?" he asked.

The point was utterly lost on the man. But he bellowed a loud denial of ever having been mishandled by anybody, and added emphasis by leaning over the table and glowering down at Templar, who sat quite still with both hands in full view. It was, according to the bully's experience, the next move in the purely animal instinct of intimidation.

At this juncture his employer and his employer's friend rose to avert what impressed them as the impending slaughter of their only engineer. But the burly tipster was enjoying the full flush of confidence in the success of his bluff. He threw the restraining arms from him and enlarged upon his determination to assert his independence.

"Lay off o' me now. This flossy bird an' me's cotta come to a showdown. 'F he figures he kin come the prohibition agent on me, like he done yestiday when I wasn't feelin' good, an' then put up a play like he was a boss here, we cotta argue it out, 'n' that's all ther' is to it."

Templar squared his shoulders, as was his habit when about to embark upon action. He was still young enough to enjoy a dramatic situation, and he affected a bored tone of voice in order to accentuate it.

"Let him be, King. I don't want to call on you to control any one of the men you picked to bring here; though it's your funeral by rights. But I'd like all of you to remember one thing. What you fellows don't seem to realize is that there's not a gun in camp among you."

The burly Docket shrank visibly as the high pressure of his belligerence oozed from him, and he sat down slowly. The others followed suit, their wide eyes and nervous, picking hands registering the dawning of realization that they had come to the kind of place they had read about, where policemen were not and where they were face to face with one another as individuals uncurbed by law.

Templar grinned at them.

"Never thought of that, did you? Just came out like babes in the wood. Not a gun among you—oh, yes, I made sure of that long ago. Well—" he rose and pushed back his chair and stood over them, suddenly aggressive in his turn—"neither have I any! I don't carry a gun. For the same reason I don't allow liquor in camp."

He let the words soak in.

"Now, Mr. Docket, if you want to be sure who runs this camp, we'd better decide right now."

Docket y's mind was slow to assimilate new impressions. His little eyes flashed to the faces of the others and up to Templar's stern gaze and then back to the others, never meeting any single look and holding it—the animal uneasy. He met no encouragement. They were cowed by the coup, as he was himself. His eyes fell before the challenge in Templar's.

King relieved the situation and accepted the position by appealing to all.

"Of course there's got to be a nominal head or director or something over the work; and after all, I'm only my uncle's financial representative. So of course the boss should be Templar, who knows all about what's got to be done and all that." And he added, "Dontcher know."

"You're right," said Templar with emphasis. "And it isn't nominal either. I've been through this thing before, and I've learnt a heap; and I know how to run camp. So let's cut out the arguments and arrange schedule."

He sat down and grinned at them in all amity, now that his point was established; and they smiled back weakly—some of them. The cheerful grin faded slowly from Templar's face. He was not meeting with the straightforward response which he had been accustomed to find among the kind of men he had been accustomed to meet. He had known quarrels in other camps; but those, when they had once been decided one way or the other, had closed the incident. Nothing had been held back to rankle. But here somehow he felt that the incident was by no means closed. An uncomfortable premonition of future trouble came to him; and he wondered—very hard indeed.

The great condors circling in the thin blue ether high above craned their bald heads and turned their cold yellow eyes to watch those strange doings in the ravine. And as the condors watched, so did old Mamu the Soothsayer crane his withered neck over the edge of his rock and watch every gesture; and watching, he drew inferences of the character of each one and tabulated them against his future need to play upon them as he might contrive—which was another of the very astute teachings out of the lore of the ancient priests of the sun—as it was of the priesthood of many other peoples who had never heard of the people of the Inca.

The dominant one, he knew, of course. They had met before; and he knew him to be resourceful and terribly persistent as well as equipped with fearful magics known to the white men. Him Mamu regarded as his most dangerous adversary.

Three of the others he put down as of no account. They were weak and irresolute. Their only danger was that they had knowledge of that which must be kept secret.

But the fourth. The wizard judged him with keen attention. He was boastful; therefore vain. Loud and quarrelsome; yet controllable by a stronger will. Obviously evil-tempered. So much he could determine from the man's actions, without hearing or understanding more than varying tones of voice. A tool, the wizard counted him. To be used perhaps if need be and if the sun god would help, to destroy the others.

A situation not so hopeless for one who knew how to make use of the passions of men. In the meanwhile he could watch as tirelessly as did the great birds, the messengers of the sun god.

TEMPLAR let his amateur crew finish breakfast and light up their various selections of smoke before he introduced the distasteful subject of manual labor.

"One of the first things we've got to arrange," he began with a sly contracting of the eye-corners, "is about who takes first crack at cooking." It was a bombshell.

"Cooking? Holy gee, I don't know a thing about cooking."

"Nor me."

"Me neither."

"Aw, —, I yain't gonna do no pot-wrastlin' fer nobody."

Templar was in the delightful position of complete independence.

"All right, fellows; I don't care. I told you before we started that this camp was going to be one of the worst I've ever known. I told you you'd never be warm. I told you there was no firewood within forty miles, and all you'd ever see to bum would be chips from our scantlings. I told you there'd be no labor available. I told you you'd better bring a white cook; but you all figured you'd have to split shares with him and wouldn't do it. You all made your agreements with Mr. King with open eyes, and now it's your funeral.

"You can make any arrangement about grub you like. I'm wide open. We can each rustle our own if you want—it's inefficient; but as far as I'm concerned I'd be sure of good grub. Or, I'm willing to take my turn of eating what you fellows cook. I've been in camp before, and I've eaten worse grub than you fellows know how to spoil. Grub is the last thing to make me unhappy. I'm no sybarite."

There followed a silence full of consternation. Cooking in camp over a kerosene stove had appeared a sort of picnic idea to them from the viewpoint of far Broadway. But it took on a sinister aspect when they found themselves faced with the hard and immediate fact that somebody had to get up in the cold morning to make coffee and bacon.

Templar was human enough to enjoy the situation. There were a thousand men whom he would have chosen to bring with him rather than any one of the companions whom necessity had thrust upon him, and it gave him a sour satisfaction to see them suffer from their own deficiencies.

He let them reflect on the gloomy prospect while he went on to outline the vastly more important matter of the work that was to be done.

"Well, think over the grub prospect as we work, fellows. Here's what to do; and I'm aiming to get a start on it today. First there's the cut-off of that inflow. The flume. Half a week's work on that, and nothing that'll be heavy on your lily-white hands. Then the pipe-line. A little bit harder; but you'll be getting used to it. Three days on that. Then the big job—but no, 't isn't such a big job either—though I've more than a heap of respect for the old man of the mountain who lives up there."

Sheepish uneasiness was on the faces of all of them as they recollected the panic of the evening before. The desolate, steep-walled gorge, coupled with all its attendant discomforts, did, in point of fact, carry the impression of imprisonment in close proximity with a mysterious being of occult powers about whom they had heard so much. Docket and his tout, who sat with their backs to the wizard's outpost, both stole glances over their shoulders.

"No, not right behind your ear, Marty. It's 'way up. See that pink-and-green-streaked rock up there? And back of it the remains of the Inca road? Well, the cave mouth is just behind that hidden by the rock. Now here's the job; nothing in itself, but I've an idea it's going to be the toughest of the lot, 'cause the only place we can get at the underground flow is inside that cave."

"What underground feed?" from Baboon, the geologist.

"Well, it's this way —excuse the elementary stuff, Baboon. You fellows can all see that there's a heap more water coming down 'way up the ravine than flows into the lake here. See that big fall up there? Well, most of that runs into a natural fissure in the sandstone, which is just an arm or a tunnel of the same system of underground drainage which formed the cave where the old man lives. It runs right along through the cave and then ducks under again and comes out somewhere under the surface of this lake. I've a theory that that is why the old Incas thought this to be something queer and made it sacred, and that's why they dumped the treasure into it."

That magic word! It chased the gloom which had settled over all of them at the dismal prospect of cooking and of—to them—hard labor. They brightened up amazingly and showed immediate interest. All except Baboon. The elementary mysteries of geology had no interest for him, and the explanations were merely boring.

"What we want to know," he interrupted impatiently, "is how you're going to put a cork in that underground system and keep it out of here. I don't see any divide or watershed or anything. Suppose you do cork it up; it's got nowhere else to go. It'll just fill up the hole or the cave or the tunnel or whatever it is, and then overflow and keep right on coming."

"Just what I'm coming to," said Templar. 'The old Inca engineers cut an artificial channel and side-tracked that water. Built a stone dam right across the edge of an awful hole where the river plunged down to connect with our lake, and side-tracked the whole stream down another fissure. My guess is that they ran it off as part of their wonderful water-supply system of old Cuzco."

"Well. How'd it get back in here then?"

"That's where the old wizard came in with trumps. I had everything fixed up here; siphon going fine; and I'd reduced the water-level by nearly twenty feet when he busted the dam and flooded me out. So our job is to repair the dam. Not such an awful job in itself. Yet—I don't know—that old wizard—he's a darned shrewd old man."

Docket y's belligerent scowl came very easily to his face.

"Aw, —!" he grunted. "There ain't no old man gonna keep me from gettin' at that dough. 'F he gives any trouble leave 'm to me."

"Yah! Yuh wasn't dat noivy yestid'y," Marty jeered at him.

Docket flared out. The more readily since here was safe opportunity to reestablish some of his lost prestige.

"You shut right up. I wasn't in no shape yestid'y. I yain't scared o' that boid. No, nor nobody else neither."

The last with sulky bravado. Templar affected not to have noticed the implication. Work was to be done. He broke up the conference and tried to infect his crew with some of his own enthusiasm.

It was no very brilliant success. Work, physical labor, was an effort that was foreign to all of these people—except perhaps to Docket. But that had been a long time ago; and since those days he had developed that "line of graft" which accounted for his present comfortable condition.

Still, by dint of strenuous example, progress of a sort was achieved, though the few days estimate for the repair of the flume dragged on into ten. It was not a very shipshape job, and would never have passed the scrutiny even of an inspector of street-cleaning. But Templar let it go; after all it would not have to stand for more than a month or so, and then the gold would be theirs.

It was only the constant promise of the rich reward that kept the crew at their job at all. Each succeeding day saw them grumbling louder and snarling more readily at one another, as the soreness of their hands kept pace with the soreness of their digestions.

The food, in truth, was awful. The first lot had fallen upon the geologist, and his very best efforts seemed to indicate that he was earnestly striving to perpetuate specimens of his profession. Tempers suffered accordingly. There was nothing new about any of it. It has happened in all camps, and will so continue to happen.

"Feed the brute" is one of the wisest of our maxims; for the men are few whose souls can rise above the discomforts of a continuously unsatisfactory cuisine. Those who go out into far-away camps know it. The most Christian and forbearing of men will disclose a savage temper after a poor dinner.

In this camp all the dinners were below the minus mark of imperfection; and these men were of the great metropolitan order of sybarites, except Templar, who could eat, when occasion demanded—as can all the brethren of his craft—anything at all.

But the others. They came to mess reluctantly, with an anticipatory grumble which developed into the growling of bears as they viewed the mess which was spread before them. Baboon growled back and challenged those who didn't like it to take on the job themselves. But loudest growlers as is the custom of camps, shrank from drawing upon their own heads a similar measure of disapproval—and growled the louder therefore.

And on the top of it all, it was cold. Permanently cold—and no satisfying warmth of recuperation in meals. Quite the worst camp he had known, as Templar had warned them. He began to be uneasy about the sullen tempers of his crew.

AND as ceaselessly as the ill-omened condors, old Mamu the Soothsayer watched. He haunted them. All day the round bald dome of his skull could be distinguished peering over the edge of his rock. And every evening with the setting of the sun, just as the swift darkness was beginning to swoop down on the narrow gorge, he would leap to his feet, a ragged portent the color of a smear of blood in the last rays, and would call upon his god for inspiration to save the sacred trust of his fathers from these white men who profaned the place of the tabu.

The wailing echoes crawled up and down the ravine and added a chill premonition of their own to the prevailing dissatisfaction.

Docket the superstitious remembered some half-forgotten tale of his youth about the last of the harpists, perched upon a high crag, cursing some English invader, and he experienced an uneasy prickling of his spinal hair. He shook his fists up at the wizard and shrieked curses back at him; and then, half-ashamed at his display of nerves, growled:

"Gee, that boid gimme the willies. I'd liked to see 'm miss his step jes' oncet. Haw, haw! He'd sure flatten out some."

"If he was to miss right now, he'd likely flatten you," said King sourly. "It's a clear drop from up there."

But the old wizard had no nerves. He stood on his dizzy brink and looked down with the same beady-eyed scrutiny as did the great carrion birds from the crags. His only concern was keen observation of everything that these white men did.

Queer, the old man thought, how they quarreled and snarled at one another over their work. If they hated it so, why then did they work? There was no overseer with a whip driving them. Yet they drove themselves for the sake of the gold they coveted. How they mucked and scrabbled for that poor metal which could be used only for ornament, these white men! Of a surety they must all be mad for that metaL

Old Mamu was quite unable to conceive the extent of the physical discomfort to which they were subjecting themselves—what with the perennial cold and the high elevation that caught at their starved lungs and the wretched food that gnawed at their starved stomachs—all for the sake of the gold. But he could see the effect of their privations on their tempers.

"What wouldn't these white men do for gold?" he cogitated aloud to himself. "What had not those other white men whom the legends of his fathers told of done for gold? If the ancient records written in knotted strings were true, they had suffered inconceivable hardships and committed unthinkable crimes for that yellow stuff which could serve no useful purpose, but which seemed to have the power to make them mad."

If these men became so affected by the mere hope of finding gold at the bottom of the lake, what would they not do if they could see some of the hoard that he knew about?

Once again there came over his face the slow deepening of the thousand furrows and the thin stretching of the lips which indicated that the old man chuckled inwardly.

"Ha!" he muttered to himself with cold satisfaction. "There was a sacred trust which I am quite sure is known to no living creature but myself—and perhaps to the great condors, the sun birds, that have watched unceasingly from the beginning of time."

As if to remind him that arrogation of all knowledge to himself was a presumption, an enormous king condor—with the white bands under its wings—dropped from above in a vast volplane and hurtled down the ravine on motionless pinions in one grand, glorious swoop; so close that he could hear the swish of the wind through its great feathers and could see the cold glitter in its yellow eye.

The bird turned its bald, wattled head to look at him as it swept past and croaked sepulchrally, hoping doubtless, as did Docket, that the frail old man would lose his balance and so furnish a meal.

But to the wizard it was no other than a warning against presumption. He amended his chuckle therefore. The secret was known, of course, to the Lord Sun and to the sun birds, his messengers; but of all living human beings, to himself alone. For the ancient records knotted into colored strings had it that the priests of the sun, when they had once come to the inexorable decision that never must the fatal knowledge come to the white men, had killed off all those others, slaves and weaker vessels, who knew and might be tempted or tortured to tell.

There was a power to render a world of white men mad! There was a latent force, hidden in the heart of his hills! If these men reverted so easily toward the animal at the thought of a mere small consignment of the Inca's ransom, what would they not do if—

The old man's muttering suddenly ceased. He stood tense, quivering throughout his body, while his thin, claw-like fingers slowly closed like the grip of a raptorial bird and his beady eyes glittered as had the eye of that condor. A tremendous thought began to take form in his brain.

That condor! The sun bird!

It was a message. Lord Sun had sent his messenger with that thought! That was why the bird had come so close and had spoken so ominously. It was an inspiration direct from his god!

The ancient priest flung out his arms and cried his worship aloud.

"Illappa! Inti, Ccana arajpacha! Lord Sun, Light of the Heavens! Thine ancient' servant hears. Glorious is the Sun. Lord over all the earth!"

He left the shrill echoes to drift up and down the ravine and scuttled back into his cave, into the inner chamber of mysteries, to make a mighty wizardry.

"— OLD scarecrow!" and, "I'm gonna twist that boid's neck one o' them days," and, "What the is he crowing about now?" were some of the growls that went up from the toilers below.

Templar seized upon the opportunity to improve the shining hour with a crude attempt to play upon the psychological reactions of his crew.

"He's cussing us out, fellows, 'cause we've got the flume done and we're that much nearer to the treasure. Let's dig in on the pipe-line and fix up the siphon. Just a three-day job"—he still clung to his hopeless estimate of their capabilities—"and then we'll tackle the dam. Just a dozen blocks of stone to be put back in place. They're lying ready to hand. An easy afternoon. Then, boys, nothing to do but sit down and wait for the yellow ingots to shine up through the bottom."

A crude attempt. So might a schoolteacher have exhorted wayward pupils. How much keener a juggler of men's minds was that untutored old wizard!

The response was not so enthusiastic as might have been hoped; though quite as much as might have been expected. Dyspeptic men do not rush merrily to labor, and they are inclined to be sourly argumentative.

"Thought you said there'd be some digging to be done. How about the sediment of a few hundred years?"

"Sediment, shucks."

Templar belittled the dismal thought. "This is a rock formation. There's nothing coming down from above to settle. Sure, there'll be a little muck; must be. But, gee whiz, I can see you fellows licking that off when you get a ten-pound ingot of gold in your hands."

It was beginning to work in spite of its crudeness. That magic word was sure of response.

"—!" Docket breathed. "Ten pounds! At how much d'ja say an ounce? Twenty bucks? I'm a sonuva gun! Ther' ain't noth'n' I wouldn't lick off'n a ten-pound ingot o' gold."

"I'll bet you there ain't," was an acid comment to this. Aggravated by—

"Nor ther' ain't noth'n' yuh wouldn't do for a dozen of 'em."

The innuendos began to soak in.

Docket y's temporary flash of good humor turned to instant belligerence.

"Say!" he bellowed. "What 'n — youse guys think you're doin'? Makin' a monkey outa me? I seen you do worse than lick mud, Tommy King; and don't yuh ferget that I knows them as'd like to know it neither. Yeah, yuh don't cotta look sideways at me, brother. An' you, Marty, shut yer face right up, or—"

"Oh for —'s sake!" Templar shouted. "Let's cut out this scrapping and get down to work. Here, grab that Stillson, King, and gimme a hand; and you two fellows carry pipe. Come on, get busy."

King came meekly enough. The very thought of possible disclosures by the other cowed him. Docket, however, glared rebellion. Once started, he was the pigheaded type that hated to be foiled of his say-so. But Templar had already turned his back and was busy with the couplings of the rusted old pump.

Docket y's belligerence was the kind that required wordy argument and loud invective to rouse it to the point of active hostility—dogs show a high development of the same tendency. Lacking the counter irritation, Docket moved off to do as he was told, but satisfied his honor, as is the habit of his type, by mumbling audibly what he would do one of these days to that stuck-up louse who tried to come the boss over him.

Templar was wise enough to let it pass. Work was more important than fruitless quarreling. Some day, he knew, the inevitable conflict would come to a head; but he hoped to postpone it to the time when the work would be finished and they would be sitting waiting for the siphon to empty out the lake. Nor was he very sure what the result of that conflict would be—Docket was a big man and burly, though soft—yet it was a prime necessity that he should maintain his ascendency till the work was accomplished. After that it would not matter.

He set himself to taking out leaky sections of the heavy six-inch pipe and replacing them with new ones, affecting not to hear Docket y's slighting remarks each time he came near.