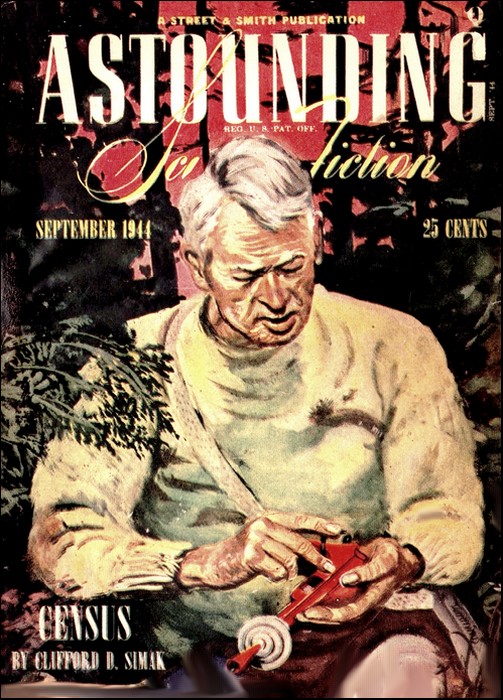

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Science Fiction, Sep 1944, with "Culture"

It was a culture, all right—but not in the more common, sociological sense. That was what they didn't understand at first—

BLOODSON was fat. He was also big. Big and fat—physically and financially. His huge body slouched motionless behind the immense black desk as the two stumbling men were brought in. Coldly, Bloodson watched the men, feet dragging, start the long trip toward him across the dazzling white floor. Effective!

Bloodson's small eyes blinked once as a stomach-twinge sent him the pain message that already his newly installed stomach was developing the usual ulcers. His fourth stomach. This time he would accept no more excuses from the surgical staff. Punishment regardless—as soon as these men were efficiently dealt with of course.

The men halted wearily. No—not wearily. Bloodson tensed. No—these men were something else. Something—extra. Bloodson felt the back of his mind groping hurriedly down into the deeper thought channels, searching swiftly for something as precedent. His nape hairs tingled as the mental processes spewed forth nothing. So there was something unusually wrong here. He, too, could feel it. His psycho-medics—the fools-had reported that much before they gave up. Well, he'd show his bungling staff why he was Bloodson.

His brain narrowed. Analyze: The men just stood there. Their ripped gray uniforms showed the violence with which all insignia had been removed. BLOODSON EXPLORATORY ENTERPRISES insignia. Faces: gray. Eyes: dull—no—unfocused. Breathing: slow. Tension: arms, fingers limp. Severe nervous shock—perhaps. Bloodson's nostrils flared. Only the shorter one showed anything: just the slow twitching of a muscle in his right cheek.

Bloodson took a flashing glance at the notes on his desk, then leaned his massive bulk forward and—his exquisite chair squeaked! It was terrifying—that squeak. In the unbelievable vastness of that soaring room of polished beauty and efficiency—that squeak sawed the nerves. Effective! Bloodson knew.

And at the proper instant, he followed with the one word, "Why?" Softly.

The word slithered across the sleek twenty feet of desk at the two men like an amorous serpent.

The cheek muscle of the shorter gray-faced man stopped for an instant—and then continued twitching. Slowly and rhythmically. The silence deepened. The room was motionless except for the cheek muscle.

Bloodson frowned. He moved his head to stare deep into the unfocused eyes of the shorter one. Instantly, his mind reeled under the smashing impact of something that brought a quick sweat to his armpits. Locked there—behind those two visual windows was a brain frozen in the tortured pattern of something too horrible for a human mind to bear. The fuses in that mind had burnt out under the terrible overload, leaving the helpless brain imprisoned in a swirling, chaotic jumble. Bloodson, shivered, and snatched at his tottering reason. Attack!

He exploded. A mountain of flesh with a whipping saw-edged voice: "Do you men want me to have you psychoed?"

Powerful as thunder crashes, rolling and booming, his amplified words smashed at the two men bouncing off to boom heavily against the distant walls of that vast room. "What explanation can you possibly offer? An entire expedition; millions of credits; years of work—all lost—except for you two stubborn, silent men."

Bloodson's voice dropped. "And the lives of the expedition. How many? If you won't talk"—the voice roared—"I have ways of making you talk. You killed nine of the men with your own hands! Why?"

The men stood there.

"What happened to the other men you didn't kill?"

Silence.

"I warn you—" Bloodson's voice way ominous. "I had a Keybetl neuro-recorder on that ship. I can have you psychoed. I can have my psycho-medics reconstruct what happened. But I warn you—the drain of nervous energy from your bodies will make you blithering idiots for years to come. Will you talk?"

Silence.

Bloodson's teeth made an audible sound. Grinding. "Psycho them."

ON the instant, the room light dimmed and men approached wheeling a machine. Heavy and squat. Pneumatic chairs swelled up out of the floor and the gray-faced men were forced into them as neat robed medics hurried up, unreeling thin shining wires from the Keybell,

The short one's cheek muscle twitched rapidly as the flashing scalpels and tiny clamps inserted the trailing wires in the proper places. His jaw worked. Up and down. But no words came. His wooden-faced companion submitted, heedless of what the medics were doing to him.

Pressure of a switch; a low hum; and a pinkish milk-white cloud solidified in the center of the room. Vague images swirled and flickered. Jumbled voices—disjointed thoughts vibrated the room,

"You can do better than that," snapped Bloodson, "What am I paying you medics for?"

THE swirling mist brightened and suddenly snapped into crystal-clear reality. Three dimensional. The interior of a spaceship—a group of men—and a young voice interlocked with a developing thought tendril of worry—

"—somehow there must be an explanation behind all this." Hardwick tried to ignore the hunger biting at his stomach and at the same time to make his voice sound convincing. "It's merely a missing factor that must be found." The growing worry nagged at him—Junior Command was an alarming thing when it unexpectedly turned into Senior Command, complete with an emergency not in the books. "That missing factor means our survival or—"

Benton interrupted. "If you were going to say 'survival or not'—I'd change it to 'survival or we'll all go psycho!' Huh?" Benton's sharp face looked around as if expecting a laugh. Not a man laughed. Faces were grim.

Hardwick held on to his overstrung nerves. "Let me finish, Benton. The scouting parties should return any moment. If they have found no trace of Captain Houseworth or the others, then we must consider them—dead." He sensed the level stares of the crew. "And that passes the command definitely to me."

Hardwick looked each man in the eye. These men were irritable. Their enforced thirty-period diet of concentrates had played havoc with their nervous systems. And the fact that they knew he, acting as Senior Command, was just as green to deep space as they were, didn't exactly help things either. They also knew that an immediate attempt had to be made to force out into the open the unseen, unguessed something that seemed to brood over this space-buried planet. He searched carefully for signs of open resentment to the fact that they realized their lives rested in his accurate judgment of the situation—and what must be done without delay. Now!

He felt a brief surge of confidence. He could detect no open resentment—yet. The next move was up to him.

Hardwick took a long breath, "Now"—he turned to the oil-splattered engineer—"what about the engines?"

The engineer sounded weary. "The same, I've explained to everybody until I'm sick of saying it. Those engines were in perfect working order until the third waking period after we landed. They just stopped. That's all. They are still perfect—except they won't work. Do you understand me?" His voice rose. "Every stinking tube and coil I've taken apart and put back half-a-dozen times. Everything's perfect. Except—"

"Except they don't work," finished Benton, dryly. "And how much longer can we function on the emergency batteries alone? Four more waking periods is tops. We won't have to worry about eating concentrates. That's my guess. Huh?"

Hardwick gave Benton a long look. "If our hydroponics hadn't disappeared, we wouldn't be eating concentrates. Those ponies were your responsibility and you've offered no satisfactory explanation as yet."

Benton shrugged. "I still don't see how those stupid, naked natives could have stolen forty tons of ponic tanks. Too big. Too heavy. The lock was guarded—or wasn't it? I'm not psychic. They don't seem to eat, anyhow. We don't know yet if they do eat, or if they do, where they get it. No agriculture; no industries—all they seem to do is play. What a stupid—"

Metal-shod feet clanked through the open starboard lock. "Something around here isn't so stupid!" It was Doc Marshal, the medic. "Other scouting party back yet?"

Wassel, the language expert, shouldered in past Marshal's bulky figure and sat down on the tool locker with a metallic thump.

Hardwick shook his head. "Did you find the captain or the men?"

A shadow flitted across Marshal's firm-jawed face. "No," bluntly. Then his face softened. "That makes you the skipper for sure, lad. Organization is your specialty, so you should do all right. Luck to you." He flexed his massive shoulders. "But we investigated that smaller black temple in the valley."

"And scared the blazes out of our well-balanced, beautifully integrated minds. Eh—Doc?" This from Wassel.

The slender sociologist in the corner stirred irritably. "If you will remember, I originally insisted that it is dangerous to interfere with any civilization's temple of religion or to try to contact their females."

"Who said anything specific about religion or women?" countered Marshal. "What did we know about their religion or their women? Where are their females anyhow? Whoever heard of a race consisting only of males between the apparent ages of ten and fifty? Where are the kids? Where are the old ones?**

"Or the women?" rumbled Wassel from where he rested.

"A moment," cut in Hardwick smoothly. "While it is true we are qthe first expedition in this star cluster, I still don't think sociological problems should concern us too much. It was our luck and should be our good fortune to have discovered a planet rich in coal deposits. We've tried to trade fairly with these natives for their hydrocarbons which are so precious to our laboratories. Our mechanos have filled the ship's hold to capacity. Despite the fact they don't seem interested in payment—we will leave just payment, regardless."

"If we leave," said Benton softly.

The sociologist shot Benton a dark look. "We are discussing sociological considerations more important than a temporary emergency."

"Temporary?" Benton's jaw dropped.

The thin sociologist ignored him. "I admit that it is decidedly a departure from the norm for a humanoid race to not appear interested in gainful trade—or acceptance of gifts. These natives have upset me more than I care to admit. I've offered them everything from gaudy trinkets to sub-ether communicators. They are not interested. Therefore"—he put his fingertips together—"regardless of what we might leave as payment, assuming we take the coal, if the payment has no value to them—we are stealing the coal." He leaned back in his corner. "That is my point and I might add that it could be a clue toward that missing factor you mentioned."

Benton sniffed. "My bet is that the engines would start if we put that coal back where the mechanos got it. Might be something religious. Then maybe we'd get off this space-forsaken hunk of dirt. Although I don't see how in blazes they could mess up our engines like this. And I'm hungry." He looked at Wassel. "If we could find out where or how they eat... hey, Wassel... how about it? Why don't you ask them for a handout?"

Lips tight, Wassel said in a slow voice: "I am a qualified expert at analyzing, understanding and speaking any language—given time. Any language—"

"Except this one," said Benton.

"Benton," Wassel jumped to his feet. "If you don't quit interrupting people—"

"At ease!" mocked Benton. "Everything's fine. In ten periods you've learned fifty-three words and seven gestures,"

"He did his best," said Benton steadily. Then to Doc Marshal,

"What about that temple? What scared you?"

Marshal took a long breath before he answered. "We weren't exactly scared, we were just—" He groped for a word.

"We don't believe it," said Wassel in a flat voice.

Hardwick felt a slow chill settle on his heart.

"That's all we needed!" exploded the engineer. "More things we can't believe, Quf skipper vanishes into nothing out of a locked control room. Men go for walks and don't come back. We don't know their language—we don't know their religion—we don't know anything—the ponies are gone—and my perfect engines wont work."

"What's getting into him?" snapped Benton. "While he sits here safe in the ship tinkering with a lot of tubes—we've all been out there floundering around, deliberately trying to find something that will flatten our ears down if we do. I say give the coal back—"

HARDWICK felt a curious sense of detachment as the hot words and accusations crackled back and forth in the cramped quarters. Let them argue. Let them talk. Somehow—somewhere, their anger-stimulated minds were going to find the thread they had all missed. A thread that could be captured and dragged out into the open where these usually cold scientific minds could logically weave it into the larger unseen, unguessed pattern. Nerves were reaching the breaking point. You couldn't blame the men. The helplessness of trying to find something to fight and not finding it was unnerving to the finest of nervous systems—especially nerves connected to growling stomachs.

Something had to be done. He was now Senior Command beyond a doubt—and the men looked to him for organization. Hardwick felt very young and troubled as he let his mind spiral back down into the room noise.

Marshal was speaking: "—as soon as we reached the door of the smaller black temple in the valley we stopped and checked the fuses on our blasters. The natives we had passed, as usual, practically ignored us."

"Up to this moment," broke in Wassel, "none of us had ventured inside a temple"—he nodded toward the sociologist—"in accordance with his ideas. We hadn't found a trace of the skipper, and Doc was in a frenzy of curiosity after seeing a native with an injured arm walk into that temple and then walk out a few moments later—perfectly healed. That's strong stuff to take without a look-see. Eh—Doc?"

Doc Marshal grunted.

"Besides," Wassel straightened up, "although limited by the small vocabulary I had picked up—I nevertheless had spent the entire previous waking period questioning one native whose attention I was lucky enough to hold. It was difficult as their language is coupled with gestures."

"Wait until you hear this," interjected Marshal. "It'll blast you."

"Well—I tried to find out what was meant by this sign," Wassel gestured, "accompanied by the long double-vowel sound." He looked around as if prepared for disbelief. "It means 'Going to Heaven'!"

"What?" The question came automatically in several voices.

"Yes—as far as I can understand—those natives merely live for the time until they go to a place which would be the same in our comprehension as—Heaven!" Wassel looked around the room nervously. "But they also return! Evidently they do it quite often. Go to Heaven and return to wait impatiently for the next time. When I pressed the native for more detailed information as to why and how the process took place he became vague—something about: You had to come and get yourself."

There was a dead silence. Wassel looked around.

Hardwick could sense the men—their minds already filled to the bursting point with contradictions—trying to digest that astounding bit of information—and then rejecting it. Their nerves, meanwhile, pulled a shade tighter.

Hardwick said quietly, "What happened inside, Doc?"

Wassel flushed a deep red. "I see—" the words came out heavily, "you don't think I correctly interpreted—**

"Forget it!" interrupted Marshal. "I'll tell them something just as bad. I'll be brief. Inside the temple were a lot of gadgets we couldn't understand. So I'll skip that. We waited. Pretty soon, two natives came in carrying another one between them. He was a mess—looked as if he had been mangled somehow. Well—they pushed open a red door at the far end and carried him in. Then they walked out and shut the door. They waited." Doc Marshal closed his eyes. "Whatever went on behind that red door I don't know, but a moment later that native walked out perfectly well." A pause.

"That's all?" breathed the engineer in a hushed voice.

"That's all," said Wassel bluntly.

THE room was silent save for the hiss of the emergency air circulation system.

Benton broke in sarcastically. "1 don't suppose you even tried to look behind that door?"

Hardwick snapped himself to the alert. "Would you, Benton?"

Benton flustered, "Why... of course... I would have—"

"That's fine." Hardwick felt his duty of command give him strength. "Put on your body armor—that's what you and I are going to do."

Hardwick's further orders were interrupted as Miller returned from his scouting trip. He was alone. He walked through the air lock like a dead man. White-faced. Wordlessly he passed through the stunned group and continued to his quarters.

"Miller—" Hardwick's tone was sharp. And as Miller continued aft, stumbling heedlessly down the passageway, he motioned to Benton. "Get him."

Miller was brought back. He sat down like an automaton.

Hardwick felt prickles start up his back. "Where are Thompkins and McKesson?"

Miller began to shake his head from side to side. Slowly. But no words sounded. Long racking sobs began to twist him double. His eyes were dry. His mouth drooled wet. Roughly, Doc slapped him, but Miller continued to sob—long racking sobs as if his throat would burst.

Hardwick fought to steady his voice as he said: "Miller's one of our best men. What could do that to him?"

Marshal frowned and began to question Miller in a quiet voice until the words came, haltingly: "Outside... Thompkins... almost here... and then—" Miller shuddered. The voice stopped.

"Quick," rapped Hardwick, "see if Thompkins is outside. Find him."

When they dragged in what once must have been Thompkins, Hardwick clenched his hands until the nails dug deep into his palms. He saw the shocked crew turning away—sickened—trying desperately to control themselves. The engineer leaned over ill, while Benton stared wide-eyed, saying, "Get it out of here."

Hardwick had to force himself to look at the motionless thing on the deck. Twisted, torn, mangled—the body looked—yes—looked as if something tremendous and irresistible had forced half of it inside out. Only half of it—that was what made it so revolting. Like a child's glove. A wet trail, splotched with crimson, indicated mutely the direction of the air lock.

Something cracked inside Hardwick's brain.

"Enough !" he roared, "we've had enough of this. All men into their full battle armor—we're going to settle this or blast every stinking temple to ruins. Marshal—you and Wassel find out from Miller exactly what happened. Find out about McKesson—drug him if you have to—but get it out and tape it. I'll want to hear it before we leave. Now jump! On the double!"

That did it. The verbal explosion did it. The men moved swiftly, each to a job he had been trained for. This was something they could understand and relish. Action at last after endless waiting. Hardwick's orders rolled from the loudspeakers throughout. The ship vibrated to the thud of running feet, excited voices, the clank of body armor and the breaking out of battle equipment.

THE assembly klaxon blared, and the men jammed the tiny room forward of the lock.

Hardwick counted them: "... twelve—thirteen. A baker's dozen. All right, men. This is it. We've been trying to handle this thing in a civilized way according to the book some brass hat writes sitting at a desk. By following the book we lost four men. That's four men too many. We've tried to think this thing through to learn what to fight—well, now well find it! Marshal play the tape you got from Miller."

The men were silent and attentive as Miller's halting voice, drug-deadened, filled the room: "Three of us... up to biggest temple... top of the hill... Black... five miles square... five miles high... I guess... got to the door... big door or opening... yes... opening... McKesson volunteered to go in." A long pause. "He... went in the blackness... and... his torch and radio call just winked off—" Pause. "We waited long time... decided best return to ship... almost here when a wind and rustling noise... something came down... could see Thompkins struggle and something... twisted and turned him until... until—" A longer pause while Doc Marshal's voice was heard to say, "Might as well give him another shot." Then Miller: "Must have fainted because when I came to, I saw... 1 saw—" The sobbing started again.

Hardwick switched off the tape. "That's it men—whatever it is. We'll take a look at that temple first. Take along two semiportable blasters and extra-heavy duty fuses. Let's go."

The men marched, close formation, with a semiportable blaster wheeling front and rear through the town and past the outskirts. Without the heavy-duty blasters the party could have reached the temple with the aid of their suit repulsors in a tenth of the time. But the walking felt good to their ship-cramped muscles.

The naked natives they passed only favored them with brief stares. The late afternoon sun glinted dully on their formidable battle armor as they climbed the hill to the square black temple. Far below, their ship dwindled until it resembled a tiny gold needle.

Hardwick halted before the opening. The building—if it was a building—was a solid black without seam or blemish. It erupted, squat and massive, five miles up into the air. What substance composed its walls he didn't try! to guess or why or how or when such a building was built. The opening was only noticeable by being blacker than the walls. Experimentally, he nicked on his powerful hand torch and was surprised to see the opening swallow the intense beam like space itself. The opening seemed to be several hundred yards wide and about half a mile high. He couldn't be sure. What reason could a race of naked natives have for a thing like this?

With the men watching, Hardwick approached the opening and carefully thrust the head of his battle-ax into the blackness. It just disappeared. He felt nothing. He withdrew the weapon and examined it critically. Perfect. Careful to keep clear of the black veil—it seemed a veil—he again thrust the ax through and lowered it until it touched something solid at what should be floor level. He straightened up and drew back. As he turned, he noticed the setting sun was withdrawing before long black shadows that were slowly swallowing the ship in the valley beneath. A chill developed unaccountably. The Powers of Darkness? Hardwick muttered irritably at himself. He was being silly. The men were waiting.

"Hardwick!" It was a voice, full of alarm, crackling in over his headset. The men were running toward him and pointing at something behind his back.

HE swung around, both hands tense on the handle of his heavy battle-ax. Something was stepping through the veil. It was a native. Bronzed and bare of any clothing. The native walked toward them, mouthing words and making gestures. In some sort of a way, Hardwick felt that he should know this native. As if he had known him somewhere.

The native walked over to Benton and said in perfect Earthian "Well... I didn't think I looked that surprised. Come along now—"

Marshal gasped. "He speaks Earthian. Why, he looks like—"

"Seize him," ripped Hardwick as the native took the open-mouthed unresisting Benton by the arm and led him toward the dark opening.

One of the gunners whipped up his blaster and the native's eyes widened in alarm. "Don't," he screamed as the blaster leveled, "you don't understand... don't—"

The blast caught him deep in the shoulder and spun him around, hanging desperately on to Benton who seemed dazed by the nearness of the blast.

Dashing forward, Hardwick saw the native, with a last agonized gesture, push the numbed Benton through the yawning opening into the all-engulfing darkness.

Hardwick and Marshal were on the native in a flash, dragging him away from the veil.

"You speak Earthian," gritted Hardwick, "now we've got one of you. What goes on?"

"He looks like Benton," cut in Marshal.

The native rolled his head helplessly, his voice weak. "I am Benton." The voice faded and the eyelids fluttered.

Hardwick gasped. He looked close. It was true—it was Benton. A different Benton. Skin bronzed from bead to foot. Slightly older, perhaps. Bare feet calloused.

The bronzed Benton licked his dry lips and tried to gather strength. "Remember Wassel said you had to come get yourself to go to Heaven!" His voice rattled and the eyes dimmed. "I've been in Heaven—lots of women. Beautiful women and lots of kids—my kids. Was going to explain... only... you—" A long quiver started to run through the body. "Don't go back... they—"

Benton was dead.

Hardwick was startled to see Doc Marshal straighten up suddenly. His face was drained of all blood. Silver white. His voice thick, he said, "Let's get back to the ship."

"No," Hardwick was firm. "I'm going in there and see what—"

"It won't do any good," said Marshal dully. "I've got to get back to the ship. I've got to. Then I'll know for sure." He flicked on the warming button to his suit repulsors. "I'm going now. Coming, Wassel?"

Hardwick's mind rocked. This was unthinkable! He was in command—or wasn't he? Could Marshal be turning yellow? Anger blazed within him. "I'm going in there."

"If you wish," said Marshal tonelessly, "but it won't do any good. I'll know for sure when I get to the ship." He pushed his throttle open and soared swishing up into the night.

Wassel looked at Hardwick keenly. "Should I go with him? Think he needs me?"

"He needs something." Sickened, Hardwick turned away. "The rest of us can handle this." He didn't even look up as he heard Wassel's body whistle up and up in a long looping night down toward the ship. He felt empty.

Hardwick pulled at his scattered emotions. This was no time for a letdown. "You—Taylor. Hook up to my belt cable and you to Gregor and so on down the line. I'm going in as far as a cable length. If my radio cuts out—don't enter unless I give three tugs. If I pull once—pull me out. Quickly. If you want me to come out, pull twice and then pull me out anyhow. Got it?"

THE men moved about their duties quietly, their glowing hand torches and shining battle dress giving them the appearance of gnomes. Hardwick shook himself. He must get a better grip on his nerves or he would be imagining things. He tried a short laugh. The laugh sounded like a grunt. Or did he need to imagine things? Hadn't enough happened already?"

Slowly, carefully, he approached the black curtain. It drank the beam of his torch. No reflection. He pushed his battle-ax through. Nothing—then his arm. No sensation. Now, tensely, he inched his foot into the blackness. It seemed solid. Now he was almost inside—almost—

Instantly, blackness. Hardwick shivered but began a slow sliding, inching progress deeper into the blackness. His headset was dead. Not even the hiss of static. He mustn't get lost. The thought made him whirl in the direction of the opening behind him. Nothing—panic seized him and he was about to grope for the belt cable when without warning he was jerked viciously from his feet. His mind spun as he felt himself hurtle through space to crash heavily on a hard surface.

Hardwick opened his eyes. He was outside! Sprawling on the ground. Everything was a chaos. Dimly he could see the men firing rapidly in all directions. Firing at something he couldn't see. And didn't understand. His mind snarled inside his skull. The eternal stumbling and fumbling and waiting now seemed ended. Something was happening. He started to run over to where one of the semiportable blasters was spitting intolerable flashes into the dark sky—and stumbled over a body. Automatically he dropped his glare shield to absorb the blinding flashes from the blaster and saw it was the crushed and mangled body of Taylor. The strong cable was snapped from the belt like thread. That tremendous jerk—his temples pounded—had pulled him out. But what had done that to Taylor. A few feet away he saw another body flattened and impressed into the hard soil as if from the blow of a gigantic maul.

Overhead, things swirled and whirled. His straining eyes couldn't quite catch an image in definite focus. The men were drawn together in a tight ring—back to back—their blasters flashing upward in futile seeming blasts. The impressions, the thoughts, the incoming scenes all washed into his mind as a gigantic overwhelming wave. Almost in the same instant, he gave the command to return to the ship, dropped his cable and flicked on his repulsor. He waited until the last man had cleared and then put on full acceleration for the distant ship.

The air sighed at his body armor as Hardwick, every muscle tense, eyes wide, waited for something to happen to him. The wind whistled. Vague things brushed him—or did he imagine it? His knee hurt.

The ship swelled in size as he dropped swiftly. He could see tiny figures tumbling into the open lock. The lighted opening yawned—swallowed him—the lock clanged. He was inside!

"SIT down, Hardwick." The voice was weary. Weary as death.

Hardwick turned.

Doc Marshal faced him. He held a blaster cocked at full aperture.

Stunned, Hardwick stood there.

"Sit down. I don't think outside will bother us now that we are hack to where we are supposed to stay like good little boys." Marshal twitched the blaster. "Pardon this thing—but first I must know how all of you will feel about what I have to say. It's not pleasant."

Hardwick hardly heard his words. He had noticed a faint familiar throbbing beneath his feet. Why—that meant the engines were functioning again. That meant they could move once again. He galvanized into action. "The engines... we're leaving—"

"Hold it!" It was Marshal holding the blaster dead on him. "We're not going anywhere."

The words just skittered across Hardwick's mind for an interval before his brain accepted the unbelievable knowledge his ears brought.

"Not... going... anywhere?" Hardwick heard himself say the meaningless words and his mind tightened. "Seize him, men. We're getting out of here."

Not a man moved. Their eyes were riveted oh the blaster held so steadily.

For the first time Hardwick noticed that Wassel was standing slightly behind and to the right of Marshal. His eyes held an expression that made Hardwick wince. He looked at Doc Marshal and there, too, was a look of hopeless, utter defeat.

Hardwick sat down.

"That's better." Marshal said it almost gently and then his voice shook as he continued. "I'm sorry, Hardwick. I'm sorry for everybody. I'm even sorry for myself." He took a breath and seemed trying to form a sentence. Finally, he managed: "If we are the men I think we are—we are all dead men!"

Hardwick's nerves jumped. He had to deal with this situation psychologically. Doc Marshal, his old friend, must have cracked up. He tried to relax and say in a calm voice: "Now look, Doc, put down that blaster and let's start from the beginning."

Marshal smiled grayly. "There is no beginning now—this is the end." He tightened his grip on the weapon. "So don't think you can talk me into putting this thing down. This is the finish for all of us. I've talked it over with Wassel, told him what I'd analyzed and he agrees. Right, Wassel?"

It was the look on Wassel's face and the utterly hopeless way that he nodded that gave Hardwick his first grave doubt. Wassel's eyes held a message. A dreadful message. What had they discovered to pull the backbone out of men such as they? What had they decided?

Hardwick thought darkly. Let Marshal talk all he wanted to, but the first unwary instant—he—Hardwick, would get that blaster and then he would see. But he mast be swift, as Doc was an expert with a blaster.

Marshal went on: "Hardwick, during your brief assumption of Senior Command, it is my opinion you did your best. I'm sure the men feel the same. You were under a tremendous strain. No one could ask a man for more. You did all right."

Hardwick's heart missed three beats. What did Doc mean by saying: did and were? That was as if his command was past tense! What did Doc mean?

"Explain yourself," he burst out. "This is mutiny!

Doc Marshal shook his head. "It is far more than mere mutiny. But I am putting the responsibility solely on my own head. And my main responsibility is seeing to it that you all either kill yourselves"—he looked around the suddenly hushed circle—"or I'll kill all of you—to a man!"

Hardwick could hear his own mind repeating that astounding message word for word—over and over—like a recording tape. It didn't make sense. The engines were working again—"

Words tumbled out of Wassel. "Don't you see? The rabbits!" His voice shrilled. "Just like the rabbits and guinea pigs in Doc's laboratory."

Doc Marshal's tired voice cut in: "Like my rabbits." He paused as if he had to mentally lift a great weight. Then: "Hardwick, I have a laboratory full of animals back there. I breed them for laboratory purposes. Experiments, toxins, cultures, vitamins. Things we humans breed for our own selfish purposes. I don't keep the male rabbits with the female rabbits. The rabbits don't know who built their pens. Or why. They don't know how food magically appears or from where. They don't know how they are healed. Time to them is surely different from time to us. They don't know how one rabbit is miracutously transported from one pen to another. It must be rabbit heaven for a healthy male when he is to put into a pen full of—"

"STOP IT!" Hardwick was astounded to realize it had been his own voice that had blurted that command. His entire being retreated from the realization that was trying to get a foothold in his brain. He said dully, "All those humanoids out there are nothing more than—" He couldn't finish. "Then why don't we get out of here?"

As if off in a distance he could hear the other men clamoring. Angrily.

Marshal blanketed the noise. "Wait—my original statement was that if we are the men I think we are—me are all dead men!" He went on swiftly. "The human race—our civilization could never accept the knowledge we now have. Think what a devastating realization it would be to our civilization to know it was nothing but a race of—wild rabbits that hadn't been discovered. Humans could never face the fact that a race existed so far superior to them that they were nothing but animals used in experiments."

Wassel broke in: "After all, it's not so unthinkable that... higher life forms might need... higher life forms than rabbits to breed their own cultures necessary to protect themselves against"—he shrugged wearily:—"something deadly to them?"

Doc Marshal said, "If you were raising white rabbits and discovered that unaccountably some... black rabbits had somehow wandered rate the pens... what would you do?" He didn't wait for an answer. "At first you would make certain they didn't get away. Then you would remove a few specimens and examine—dissect a few—analyze their food supply—and then what would you do?

"Try to scare them back to where they came from." Hardwick said it listlessly. "Try to catch the rest of the bunch."

"Exactly," said Marshal. "When we got back to the ship I knew that that was what is expected of us."

"The engines were working again," said Wassel.

Marshal's image faded into focus on Hardwick's spinning brain. The blaster was steady and Marshal went on: "Whatever is out there, found out what it wanted to know. Now it wants us to go back where we came from. Catch the rest of the bunch perhaps—we don't know. We can't hope to explain or beg. It wouldn't even recognize us as thinking creatures to its way of reasoning. Us, our civilization, this ship, is probably kid's stuff. But there is one thing it probably doesn't know and that is man's—our civilization's eternal willingness to"—the voice faltered, for an instant, then steadied—"sacrifice everything—life itself, for the preservation of the race. It was inevitable, as our race expanded that sooner or later we would stick our necks out too far. Run into something so utterly far beyond our own development that it couldn't be handled in ordinary ways. This is it. But I think we can handle it."

The engineer cracked immediately like a strip of metal bent too far. His voice babbled and pleaded and cursed. "Let's get out of here."

It began to infect the other men. Hardwick could feel it. He felt strangely distant, but he could feel the growing mob instinct. The wild desire to get away from something it couldn't understand. The room was a bedlam of shouting voices. If Marshal was right—this then was death for all of them. And him. Perhaps Marshal was being too hasty. Overwrought. Perhaps he had missed something. But if Marshal was right, then he was right one thousand percent. They had to die rather than return and take the chance of whatever was out there discovering their unthinkably distant civilization. Hardwick had a smothering sensation. Even a civilization as powerful as this unknown thing that hung over them couldn't hope to find their home planet in the uncounted billions of suns unless they led the way home. Or could it?

Abruptly he found himself thinking that Marshal was right. But no—he must get that blaster and convince Marshal to wait until—he didn't know what. He snapped alert as the engineer roared:

"Why kill ourselves? I ain't gonna kill myself and you ain't gonna kill me! So what do you think of that? I say let's get out of here." His body was tensing visibly.

Marshal's face became a mask of pain as he looked at the engineer. "If the thing sees we don't leave or thinks we are trying to give it the slip, who knows what it could do? Who knows what it could learn from our brain channels if we forced it? If it already hasn't." He swung the blaster. "I'm sorry—believe me." And shot him.

IN that instant, Hardwick leaped for the blaster—and in that floating split second, as his body hurtled through the air, he knew he was too late.

He saw Marshal's distended eyes and the flaring mouth of the blaster swing toward him as in a dream. Time seemed to stop and he was suspended-in midair. The muzzle flared. Bright.

The intolerable blow smashed him. His mind filled with swirling blackness spotted with spinning flashes of red pain. Dimly he heard Marshal say, "How do the rest of you men want it? It's got to be done."

Then he must have fainted for when he felt himself coming back and up as from a great distance all was quiet except for Marshal saying, "—am sorry about Hardwick. There was no other way."

Hardwick struggled against the weakness. He must let Marshal know. His throat managed to whisper, "Right... Doc... it's all right—" and then Hardwick felt his mind going over the edge of darkness and he knew Doc Marshal was right. As his mind slipped down and down it thought bitterly—so this is death—blackness. And the thoughts and consciousness that had been Hardwick glimmered faintly and went out

Marshal's stooping figure straightened up from Hardwick's lifeless body. He looked at Wassel. "I liked Hardwick." His voice choked. "And now that leaves you and me—"

The figures of the two men suddenly flickered and the walls of the spaceship wavered as a thick milky whiteness swirled around and—

BLOODSON'S frightened eyes stared at the now fuzzy and jumbled three-dimensional images, and then at the two silent gray-faced men in the pneumatic chairs.

"Marshal," he croaked. "Wassel—you fools. Why did you try... how did you two men bring back that entire ship all by—"

"Withdrawing!" cut in the alien thought. "Enough. Suggest permitting culture to breed unmolested. useless for our purposes. Individual initiative and instinct of racial preservation too highly developed. Retention of knowledge of our existence forbidden. Suggest disinfecting local area. Withdrawing."

Terror-stricken, Bloodson watched one of the gray-clad figures collapse like a deflated balloon and the other figure rise from the chair withdrawing a strange looking instrument.

"No—" gasped Bloodson. "No—" And then he sagged in his exquisite chair waiting for he knew not what.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.