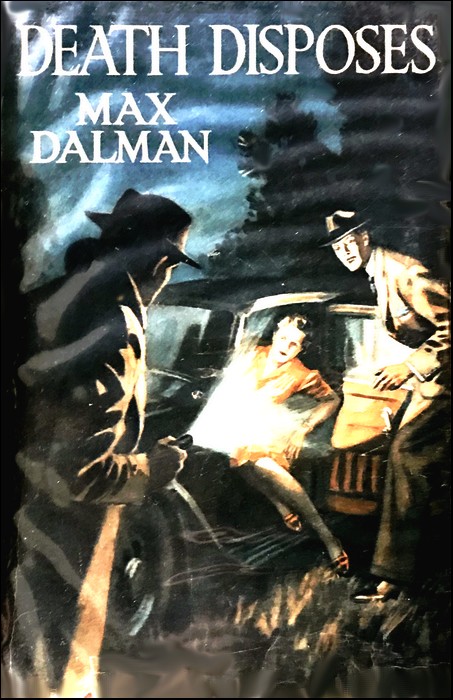

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Death Disposes," Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1945

"Death Disposes" is a classic whodunit from the golden age of detective fiction.

James Henstone, a bitter and manipulative invalid, delights in tormenting his household. He announces a new will that favors his nephew's cousin, Francis, but with a cruel twist: Francis loses his job at Henstone's firm, making it impossible to marry his beloved Kathleen until Henstone dies.

When Henstone is poisoned, his cryptic final words suggest deeper schemes and secrets than anyone suspected.

The mystery unfolds around Broughton House, with a cast of resentful relatives, suspicious servants, and hidden motives. The investigation is led by Superintendent Cary and Inspector McCleod, whose partnership adds a refreshing dynamic to the genre.

RAISING himself a little in his invalid chair, James Henstone felt again in the breast pocket of his coat. Under his fingers the long envelope crackled reassuringly, and a queer smile overspread his face. It was not a pleasant smile; but then, Henstone was not a pleasant man. Those inclined to take a charitable view might excuse his warped nature on the ground of the long illness which had kept him helpless from the time when an unexpected legacy had first made him a rich man. Those who knew him better would have said that he had always been naturally cruel, and that money had merely given him more power to gratify his taste. He himself was accustomed to say that he liked to study the emotional reactions of mankind; and the long document in his pocket was calculated to provoke quite a number of reactions.

That was why he smiled. It was a weapon capable of causing trouble to at least three people; and that two of the three were his only near relatives rather added to his enjoyment than otherwise. He took the paper from his pocket and eyed it for a moment while he still smiled. Then, reaching up, he pressed one of the three bell-pushes on the wall beside him, and leaned back, fondling the envelope in his hands.

The response was prompt. Only a minute or two later the door opened silently, and a young man entered, carrying a tray. Between him and the invalid there was sufficient resemblance to suggest their relationship of uncle and nephew, but there the likeness ended. Not only was Mark Henstone as fine a specimen physically as his uncle was a complete wreck; but the similarities of their features seemed rather to accentuate the difference in the impressions their faces conveyed. Strangely enough, it was in the expression of the young and healthy man that a close observer would have detected the most signs of suffering. There was a curiously impassive look about it, as though years of self-imposed restraint had brought him to the state in which internal emotions produced no corresponding outward change; and even the dark, deeply-set eyes scarcely varied from their look of insensate brooding.

Without speaking, he crossed the room and placed the tray on the wheeled table beside the window. His uncle glanced at it and frowned slightly. It contained only a medicine glass, a jug of water, and two bottles, one of them a warning blue, and bearing in red the words "The Linament—POISON." The other was completely filled with a pearly, almost colourless, fluid, and was the dose which, however undesirably, had been the means of keeping the invalid alive for a number of years.

James Henstone eyed his nephew with a look of patient reproof as he turned to face the chair.

"My dear Mark," he complained, "have you forgotten that Dr. Wilton changed my medicine this morning? The next dose is in an hour's time, Mark, as you should be aware.... Are you trying to kill me, Mark?"

The young man made no answer beyond a slight inclination of the head. He merely turned and picked up the tray again from the table. Henstone made an irritable motion with his hand.

"Leave it," he commanded. "I wanted to talk to you."

Mark replaced the tray. He stood waiting, with something of the impassivity in his manner of a well-trained servant. The older man eyed him with an expression of curiosity for a moment before he spoke.

"I wonder, Mark, if you have ever wanted to kill me?" he said reflectively. "I do not say 'whether you have wished me dead'—because, my dear boy, I am quite assured that that is your normal state of mind... But have you, I wonder, ever toyed with the idea of doing just that little bit necessary to ensure my permanent removal? And, if so, what stopped you?"

He paused; but his nephew gave no sign.

"Fear, perhaps? The percentage of murderers who escape conviction in this country is not, of course, reassuring; and, as my heir, suspicion might fall on you.... And yet, to kill a man in my condition is so simple that the question of murder might never arise. Natural death—accident—suicide—how easily any of them might be contrived... More probably, like your silly mother, you hold opinions about divine justice and right—"

Mark's face had twitched almost imperceptibly at the last words; but the older man had noticed it. He smiled a little in satisfaction and went on.

"Yes, Mark, your mother had odd notions. She believed, up to the time of her death, in a beneficent providence and the final triumph of right—even on this imperfect earth. Well, she is now in heaven—a region, I must say, about which I feel the gravest doubts. Apart from that, what good did it do to her? She lived miserably and died young—"

Mark Henstone shifted his position slightly. He took a half step forward, and his knuckles whitened. Trifling though the movement was, it seemed to frighten the invalid. He changed the subject.

"As you know, Mark, your mother preferred your father to me. Under the circumstances, I think it was rather generous of me to assume the burden of your education.... I have brought you up to serve me. No doubt your education has been lacking in breadth and has given you few practical qualifications.... But there. It is too late to speak of that now, unfortunate though it may prove. You are thirty-one, I think, Mark? A little late in life to make a start in modern conditions from something rather less than scratch. I wonder, Mark, if you are under any illusions as to your chances of obtaining any reasonable employment?"

His nephew spoke for the first time.

"None," he said, without visible emotion. "You have, of course, your health and brawn... Otherwise, any hope of a comparatively comfortable existence depends entirely on retaining your employment here for the brief span left to me, and then, if I have made no will, of inheriting my money and living happily ever after. I am afraid, Mark, that you would not have shed many tears at my funeral!"

Mark made no comment. With a sudden gesture, Henstone held up the envelope.

"Mark," he said, "I have bad news for you... I have made my will."

He waited for a moment as if to note the effect of the announcement upon the young man. Once again he was disappointed. With a wave of irritation he noted that there was not the slightest apparent change of expression in the other's face.

"Yes, Mark," he resumed, "this is my will—or to be more exact, the rough draft of what is to be my will. It may not have escaped your attention that Mr. Bembridge called yesterday? In his capacity of solicitor, Mark. We discussed matters quite fully, and you can have no hope of upsetting its provisions... And, by this will, Mark, you get—" He paused, like one relishing the pleasure of prolonging the suspense. "You get, Mark—nothing at all," he concluded.

His nephew merely nodded a little wearily as though giving his assent to some trifling proposition.

"Nothing at all, Mark.... Everything goes, conditionally, to your dear cousin, Francis Carlton.... He will get your money—as well as your girl. Doesn't that please you?"

He waited again, as if expecting some outburst or appeal but none came. His nephew merely glanced for a moment at the envelope; then his eyes returned to the invalid's face.

"That was all you wanted?" he asked.

James Henstone laughed, but there was a distinct edge of annoyance in his voice as he replied.

"Really, Mark, you are a disappointment to me! Where you acquired that Sphinx-like command of your features I cannot even conjecture. Your mother, if anything, was exceptionally emotional. I remember when she came to me after your father's death—" Once again his nephew moved slightly, and he broke off. "No, Mark, that is not quite all. As I said, I expect Bembridge to call with the will for my signature at half-past eleven. See that everything is ready. Warn Martha and Miss Vernon that they will be required as witnesses." He laughed. "That, though perhaps they will not realize it, means that they do not benefit any more than you do, Mark! You understand?"

"Yes," Mark replied simply. "You don't want anything more?"

"My dear Mark!" There was a pained note in the voice. "You are becoming forgetful.... You have not yet poured out my medicine."

"You said that you would not be taking it until eleven."

"I also said that you could pour it out. Carefully, my dear boy.... A little too much might produce deplorable results to one in my delicate state of health... And perhaps, Mark, you will rub my wrist—"

His nephew moved across the room and picked up the blue poison bottle. Carrying it in his hand he returned to the chair, drew the cork and poured out a little into his palm. Impersonally, as though he were dealing with a piece of wood, he rubbed the arm which James Henstone extended to him, wiped his hands carefully upon his handkerchief, and replaced the bottle on the tray. He bent over it for a moment. Though he could see nothing but his nephew's broad back, Henstone watched every movement with half-closed eyes. He heard the drawing of the cork; the clink of the bottle against the glass; the gurgle of the liquid. There was a pause. The liquid gurgled again; then there was the trickle of water from the glass. Mark moved round, as if to wheel the table over to the chair; but the invalid stopped him.

"Leave it, Mark—leave it! The light through the glass—charming, is it not? What does one of our modern poets say about lovely things? 'The sunlight through a glass of marmalade'—"

"That is all?" Mark interrupted, turning a stony face towards him.

"Except, Mark, that Francis Carlton is to come here as soon as he arrives. It will be interesting to see how he receives the great news.... Less stoically, I think, than you have done, Mark. And, who knows? Perhaps with no greater pleasure... Yes, Mark. That is all. Thank you."

As the door closed, Henstone smiled to himself. Familiar as he was with his nephew's inscrutability, he had not expected from him any much greater reaction than he had obtained. And yet, unless he was very much mistaken, Mark's feelings about what he had just heard must have been intense. In character, his nephew bore a distinct resemblance to his dead mother, however well he might disguise it, and it was for that very reason, that James Henstone, who had never forgiven an injury real or imagined in his life, took an especial pleasure in torturing him. But Francis Carlton, his next victim, had not Mark's self-control, and might be expected to give more positive results.

He smiled again, and leaning back, let his eyes rest on the sparkling diamond of light focused in the water jug. It was a fact that he got from it a genuine aesthetic pleasure, scarcely less than he did sadistically from the mental torment of other people. Then his eyes shifted to the glass, and he frowned a little.

A knock sounded at the door. He lifted himself a little in anticipation.

"Come in!" he commanded.

Francis Carlton entered. Though about the same age as his cousin, he was, in most respects as different from him as could well be imagined. The slight, boyish figure, and the brisk, light step with which he entered the room marked the contrast offered by the vivacious features and alert bearing. He smiled cheerfully at his uncle.

"You sent for me, sir?" he asked. "I hope you're better to-day?"

Henstone eyed him benignly. There was a definite satisfaction for him in the obvious high spirits of his nephew—or rather, in the prospect of the shock he was shortly to administer to them. He pointed to a chair.

"Yes, my boy.... Sit down. I want to talk to you.... And how is Kathleen this morning?"

"Oh—" His nephew flushed. "Very well. Asked after you, sir.... I just happened to call there on my way—"

"I had supposed so... One of the things which commends me to you, Francis, is that your thoughts are so easy to read. You are very different in that respect from Mark. And, by the way, what sort of terms are you on with your cousin?"

The young man frowned and shifted unhappily in his chair.

"Oh, well—" he said doubtfully. "I suppose you know how it is, Uncle.... But it wasn't my fault. Or Kathleen's, of course. He simply misunderstood her feelings towards him. She was never really in love with him—"

"Exactly. But Mark thought she was. And he still takes it to heart? I am afraid that he broods too much over these things. He might be a nasty enemy. And, if anything happened to me—" He broke off. "You and Kathleen had, I believe, some intention of getting married in the near future?"

"You see, it's positively forced upon us, sir," Francis explained a little hesitantly. "Her family doesn't exactly approve of me—in fact, she's left them. She's no money of her own. The best thing to do seems to be to get things settled."

"Settled?" Henstone repeated slowly. "But how, Francis?... It was about your prospects that I wished to speak when I sent for you this morning. As things are, Francis, you hold a position—a sufficiently lucrative position—in my firm."

"You've been most generous, sir—" his nephew began. "Yes, I'm pretty sure we can manage on that. It might be a pinch at first, but we shouldn't mind—"

Henstone held up his hand. "Let me speak," he said. "I was going to say that, though you have received a salary from the firm, up to date you have had no expectations under my will. In fact, there has been no will. Upon my death, Francis, you would be very reliant upon the generosity of your second cousin, Mark—who might, or might not, feel disposed to continue you in your present post."

"Mark feels very bitter, sir." A shadow crossed the young man's face. "I hope he wouldn't take advantage— I don't know. We've never understood each other very well."

Henstone shook his head. "Mark has, I am afraid, a brooding nature. He is not a person to forget a fancied wrong easily.... You would not trust him?"

"I don't know, sir.... I don't like to say anything—"

"To say anything against him? No. But I can see you have doubts. And it is for that reason I have decided to change the position and to make some provision for your future."

The young man looked at him eagerly. His lips opened, but Henstone continued before he could speak.

"Yes. I have decided to change everything. I have made my will."

He saw the quick flash of hope in the other's eyes, and suppressed a smile. He knew that it would not have been the right kind of smile, all the less so because his nephew at that moment reminded him strongly of his late brother-in-law, whom he had hated. But it was a part of his pleasure to prolong the agony. His eyes wandered round the room for an instant, and rested on the medicine glass. He went off at a tangent.

"Francis, my boy, I wish that you would pour a little more water into that glass.... Mark, I am afraid, is getting very neglectful. Or perhaps he wishes an old man to die. A little more water, Francis."

Like a man in a dream Carlton moved over to the table and shifted the medicine bottle to one side to reach the handle of the jug.

"Yes, Francis... Under my will, I leave you—everything."

There was a crash as the medicine bottle overturned. The young man faced him, white with the shock from the suddenness of the announcement.

"Everything!" he gasped.

"All my property, real and personal... You will be a rich man, Francis—when I am dead."

"Sir," Francis stammered. He seemed to be trying to find words to express his thanks. Then another thought seemed to occur to him. "But, sir—Mark—"

"Your cousin can, no doubt, rely upon your generosity. The roles will be reversed, Francis. He will have to come cap in hand to you—not you to him.... No, Francis. It is useless to protest. My mind is completely made up. My whole fortune goes to you."

Perhaps the young man realized the uselessness of argument. At least he did not press the point.

"I don't—I don't know how to thank you, sir—" he began.

"That is unnecessary... There is just another point, Francis. In view of what I am doing for you in the future, I do not feel able to retain your services in the firm. You have, of course, no contract. You will leave at the end of next week."

On the part of Francis Carlton at least, Henstone could not complain of any lack of emotion. There was utter dismay on his face.

"But, sir," he protested at last. "There's Kathleen—"

"That, of course, is unfortunate... But no doubt it is merely a postponement. A change would do you good, my dear boy. And sometimes I am inclined to agree with the old saying about hasty marriages—"

"But—but we'd arranged to get married in a fortnight," Francis stammered the words desperately. Previously he had heard of his relative's capriciousness; but he had never experienced it. It was still incredible. "You—you can't mean it, sir," he pleaded. "You don't understand—"

"My dear Francis, my mind is made up. Under my will, you will inherit everything... Who knows? It may not be long. I am a sick man, Francis, a sick man... And, I must say, Francis, that I should have expected a little more gratitude... But, in the meantime, it will do you good to lead a less sheltered life. Newley is coming this morning. I shall give him instructions to dismiss you. Your marriage must wait."

"Sir," Carlton begged. "I don't mind about the money... I'd gladly give it up if— Don't you see, sir, that I've got to have some money now, just to carry on, until—"

"Until I die? And I may live for years?" Henstone raised his eyebrows. "Really, Francis, you might seem a little less regretful that I still retain my precarious hold upon life. And besides, I might die to-night! The speculation will provide you with a little excitement, Francis!"

There was a moment's silence. His nephew was no longer looking at him. He was staring towards the window, with a queer, strained expression on his face.

"That, I think, is all, Francis," Henstone said after a pause. "I am tired... You may leave me... What is that envelope you are carrying? Something for me?"

The young man looked at it for a second dazedly; then handed it over without a word.

"Ah. The proofs from the photographers... Thank you.... And, Francis, you have still not done as I requested. A little more water in the medicine, please."

Francis obeyed like an automaton, seeming to fumble with the jug and glass as though he had not complete control over his hands. It was a minute before he turned to the old man with a final desperate appeal.

"But, sir, if you knew just how much it means to me at this time—"

"That is enough, Francis. The matter is settled." Henstone frowned wearily. "You are tiring me.... Tell Higson that Mr. Newley is to come to me as soon as he arrives."

With a very different step from that with which he had entered the young man moved towards the door. Henstone had closed his eyes; but he heard him pause for an instant on the threshold. Then the door closed behind him.

Henstone smiled and opened the flap of the envelope in his hand. It was among his peculiarities that he liked to contemplate his own face, even in a mirror, and photographs were an obsession. He looked at each of them, studying them feature by feature, and he was still busy when the door opened on his third visitor. This time it was a man of nearly his own age. His black hair was shot with grey, but his eyes were bright and keen. He seemed to take in the whole room at a glance as he moved towards the chair where the invalid lay.

"You wanted me, Mr. Henstone?" he asked. There was no trace in his manner of either fear or subservience; if anything there was a trace of contempt, as if he thought his employer rather less than his equal. Henstone did not resent it. He smiled blandly in welcome.

"Yes, my dear Newley," he said. "Sit down.... Oh, if you would please put these on the table for me—?"

Newley took the photographs and obeyed, shrugging his shoulders as he saw what they were. He seated himself comfortably and lit a cigarette.

"Well?" he asked.

"Newley," Henstone closed his eyes wearily. "Newley, you're to fire Francis Carlton at the end of this week."

The manager's jaw dropped slightly. Used as he was to his employer's eccentricities, this was unexpected.

"Why?" he demanded bluntly. "He's doing pretty well."

Henstone's lips tightened. "Sack him at once!" he snapped. "You heard me say so. Your business is to do as you're told."

"If I did, you wouldn't have a business," Newley answered coolly. "Oh. Very well."

"A little experiment, Newley," Henstone smiled. "I feel the need of a mental stimulant from time to time—something to show that I am still a power for good or evil.... You know, there's a certain piquancy in living with relations who most fervently wish one dead!"

Newley made no comment. His bright eyes studied the other as if he was a curious and rather objectionable insect.

"To-day," Henstone said after a long pause, still leaning back with closed eyes, "I have made my will—"

"You told me yesterday—"

"It disinherits my nephew and gives everything to Francis. To keep the balance even, I am sacking Francis—who wants to get married. And they both wish me dead!" He looked up and smiled. "Both."

Newley shrugged. "That's not my affair," he said. "I'll sack Carlton.... Now, about those figures. You said you didn't quite understand—"

"I'm tired.... You'd better write them down.... Leave them—"

His voice trailed away into silence and his eyes closed again wearily. Newley glanced at him without alarm. It was a peculiarity of his employer's condition that he was liable to doze off from time to time, generally for a few minutes after any particular excitement. With a shrug of his shoulders, the manager produced a note-book and began to write. Henstone was still sleeping five minutes later when he left.

PRECISELY at two minutes to eleven, Celia Vernon typed the final words of her last letter and added it to the finished pile. Gathering the sheets together she moved towards the door with the unhurried speed of a person who has exactly enough time. She had been James Henstone's secretary for only a few days, but it had been quite long enough for her to learn that when her employer specified eleven o'clock he expected her to be knocking on the door precisely when the clock was striking. And though not particularly attached either to James Henstone or the job, she had for the present sufficient reason to endure them.

The room where the invalid generally reclined in the day-time lay at the opposite end of the long house. To reach it one needed just over a minute from the office; but this time she was interrupted. Higson, the butler, hurried up to her as she was on the point of crossing the main entrance hall.

"Excuse me, miss." There was a suggestion of disturbance in his manner which was quite unlike him. "Perhaps you could help me... Miss Bramley is here, and insists on seeing Mr. Henstone at once. I'm afraid, miss, that—"

Celia glanced at the clock. It was just on the hour.

"Well? Can't she?" she demanded.

"Mr. Henstone would be seriously annoyed, miss, if I admitted her without instructions... And Mr. Carlton this morning, miss... He seemed very upset when he went out. I'm afraid that there may have been some unpleasantness."

Celia's lips pursed into an unladylike whistle. Her sympathies were very strongly with the butler who, she had gathered, was expected to know by instinct what his employer did or did not want at any given moment. And, since she always listened to gossip on principle, though she was not well posted on details, she had received from the housekeeper a very fair idea of the situation which existed between the relatives. Undoubtedly it was a case for tact and caution.

"Trouble, you think?" she asked.

"I'm afraid so, miss... The young lady seems very agitated—"

The hall clock struck. Celia made up her mind.

"Ask her to wait a moment. I'm due with Mr. Henstone now. I can mention it to him and see what he says."

"Thank you, miss." The butler was obviously relieved at having shifted responsibility. "I'll explain to her—"

"There's no one with him now?"

"No, miss. Mr. Newley came out a few minutes ago. I think he is telephoning, miss."

"That's all right." Celia glanced down the hall. "By the way, where is she?"

The butler also turned and looked. Cautiously, if without strict attention to good manners, he had left the visitor on the doorstep. At the far end of the entrance lobby the front door stood open, but there was no sign of anyone.

"Perhaps she's gone, miss." His tone implied that that was too much to hope for. "But from what she said to me—"

"She couldn't have slipped in anyhow?"

"Impossible, miss. I was just coming to you, miss—"

Celia was suddenly aware that time was flying. Even Kathleen Bramley might not be regarded as an adequate excuse for unpunctuality.

"Go and look... I must dash along."

It was several minutes past the proper time. She tore down the passage, reached the door a little breathlessly and knocked. In the room, someone was moving; but there was no answer. He could not be asleep. She knocked again, waited a moment, then put her ear to the woodwork and listened. The sound had stopped. In desperation she gripped the handle and turned it. The door did not yield, even when she exerted all her strength. It was evidently locked. More than a little puzzled, she tried the handle again as uselessly as before. She turned and looked over her shoulder.

Higson was standing at the far end of the passage waiting. Either he had found the missing visitor or he had given her up. She made a gesture beckoning him; then hurried forward to meet him.

"Higson, the door's locked!" she burst out. "I've knocked, and there's no answer, although I heard someone walking about—"

"But Mr. Henstone can't walk, miss."

"No... I might have been mistaken about that... But he might be ill?"

"It's very queer, miss... The door, miss. He'd never lock that—"

"Of course it's queer." Celia was getting more than a little impatient. "But what are we to do?"

It was precisely the question that Higson did not want to answer. For there was just a chance that Mr. Henstone for once in his life had locked the door, and refused to answer out of the perversity which was his chief characteristic. If that were so, it was unwise to disturb him. But if not—

"Your visitor—" Celia suddenly broke in on his thoughts.

"She's gone, miss—"

"She's not. She's there—

Celia pointed. Kathleen Bramley was just at the end of the passage. Her face was very pale, and her agitation was obvious. Celia glanced down the passage, then back at the butler before advancing to intercept her.

"Good morning," she said briskly. "I'm Mr. Henstone's secretary. Miss Bramley, isn't it? I understand that you wanted to see him... You have no appointment?"

"No— I—" Kathleen Bramley faltered. "Not—not exactly. But I've got to see him. I must see him at once... It's terribly important I must!"

Celia suppressed a sigh. Secretaries, who exist largely to serve as a soft but immovable cushion between the world and busy men, know that almost all interviews are important to those who seek them. And in the back of her mind was the worry of the locked door.

"You couldn't come later?" she suggested. "Perhaps I could arrange an appointment—"

"I've got to see him. Now. Every minute's important—"

"Well, I'll do my best." Celia's smile was forced. "If you wouldn't mind waiting—"

She ushered the girl into the first room that came handy, saw her safely seated and hurried out. Glancing over her shoulder she noticed that the visitor had already risen and was pacing to and fro before the window. She could not worry about that. Higson was where she had left him. Evidently in a crisis he was one of those helpless men who wait to be told what to do.

"Higson, we've got to do something.... Mr. Henstone may be ill. If not, why doesn't he answer? He was expecting me at eleven. It's ten past now."

"He might be asleep, miss... He does doze off now and then."

"With the door locked?"

"Never, miss.... You're sure it was locked?"

"I tried it twice.... Might have stuck. You'd better try yourself."

The butler followed her without enthusiasm. He wished to take as little part in the proceedings as possible. This time, Celia scarcely troubled to give the merest perfunctory rap on the woodwork before she turned the handle without waiting for an answer; then she pushed with all her strength. The door opened instantly and she almost fell headlong.

"What—? I could have sworn—"

The words died on her lips. Higson, waiting prudently in the background ready to retire at the first sarcastic words, saw her astonishment give place to a look of horror. Every vestige of colour had left her face.

"Oh! What—? He's dying!"

Before the butler could move she had darted into the room and was bending over the chair where the sick man lay. He caught a glimpse of Henstone's livid face and glazing eyes, and heard his gasping breath. But he was still in the doorway when the girl turned to him urgently.

"Higson! Get a doctor. At once! Get Mr. Mark. Hurry!"

The butler hesitated only a moment before he started off up the corridor at an undignified run. He snatched the receiver and snapped the number of Henstone's own doctor. It seemed an age before anyone replied.

"Dr. Wilton? This is Mr. Henstone's butler speaking.... He's very ill, sir. Dying perhaps... Thank you, sir."

Only a minute or two had elapsed since the secretary had called him. Slamming back the receiver, he hesitated a moment. In all probability the library was the likeliest place to find Mark Henstone. He was just moving across towards it when the door opened and the young man himself came out.

"Mr. Mark!" In his agitation he failed to modulate his voice to its usual discreet tone. "Your uncle, sir! He's ill—dying, sir! Quick, sir... I rang for the doctor."

But Mark Henstone did not stir. He looked like a ghost.

"My uncle? What—?"

"I don't know, sir. We went in and there he was. Hurry, sir!"

Mark Henstone suddenly came to life. Without further questions he was racing towards Henstone's room. Higson, already breathless, caught him up only when he halted in the doorway, staring into the room.

The first glance was enough to show him that he had come too late. James Henstone was lying very still. His head had fallen awkwardly to one side, and his face was already assuming the waxen look of death. Evidently half-fainting, Celia Vernon had sunk into a chair beside him. With one hand she was covering her eyes; in the other, she still held precariously a half-filled glass of water. Mark sprang forward, and in a moment was bending over the dead man. The butler followed more slowly. He gently took the glass of water from the girl's hand and placed it on the tray, giving a single look at the still form in the chair before he turned soothingly to the secretary.

"Lie back a minute, miss.... You'll feel better soon."

"He—he died," she said weakly. "Almost as soon as you went. He died.... I've—I've never seen anyone die—"

"Yes, miss," Higson comforted her. "Don't worry, miss."

Mark had been standing beside the chair with his head bent. He turned as the girl spoke again.

"He—he was breathing queerly. I tried to give him some water. He spoke a few words—"

"He spoke, Miss Vernon?" Mark looked at her keenly, turning from the dead man. "You heard—"

"He said: 'Doctor... poison... medicine.' Then he stopped. I thought he was dying then. But he half sat up... Then he said: 'Mark... the girl... Murdered'."

"He said that?" Mark's face was as white as paper. "You're sure?"

"Yes... He was breathing dreadfully, but he—he smiled." A shudder shook her. "And then: 'Money—diddled—old will—Broughton House—strip paper—wall.' And then he was dead."

Mark stood staring down at her. There was a sound of voices outside. Newley and Bembridge hurried in.

"He's—he's dead," Mark said in a curious voice. He seemed to be defending himself against an unspoken accusation. "When we got here—"

Newley glanced at him without answering and hurried over. He took one wrist between his fingers and bent down listening. Then rose slowly.

"He's dead," he repeated, and there seemed to be an accusation in his eyes as he looked at Mark. "Who found him?"

"Miss Vernon was here when he died, sir," Higson answered.

Newley's gaze fixed itself upon the girl compellingly.

"He said—he said he was poisoned. By the medicine—"

She stopped abruptly. Her senses were coming back to her and she realized that what followed was practically an accusation of the young man before her.

"Yes? Yes, Miss—Miss Vernon?" Newley prompted sharply. "What else? It may be very important—"

"He asked for his nephew—"

"You mean he spoke his name?" Some intuition seemed to tell the manager of the fact which she was seeking to disguise. "What did he say? 'Mark'?"

"Yes," Celia admitted. "He spoke of a will—"

She broke off at the look of horror which showed not only on the face of Newley, but on that of the lawyer. Both had turned, and were looking at Mark without speaking. There was the sound of a car in the drive outside. Newley drew a deep breath.

"That'll be the doctor... Bring him here at once, Higson." He turned to Mark as the butler went out. "You've sent for the police?"

It was almost a command, and the young man evidently sensed the implication behind it. He winced, and a flush slowly spread over his face.

"The police?" he echoed. "No.... But—but my uncle's been ill for years... Is it necessary—"

"I'm afraid you'll find it is, Mr. Henstone." There was a grim undertone in the manager's voice and he looked at the young man sternly. "After what Miss Vernon has just said—and after what Mr. Henstone said to me this morning."

"What my uncle said to you?"

Mark Henstone's face had resumed its expressionless mask, and his voice was well controlled, though it trembled a little with some suppressed emotion. He met the manager's accusing eyes squarely.

"Yes," Newley rejoined. "Your uncle told me he was about to make a will. And its provisions. He implied—"

"Well, I don't think I should shrink from any investigation if I were you."

"Do I understand that you're accusing me," Mark spoke quite quietly, "of murdering my uncle?"

"He's taken his medicine." Newley pointed to the table. "It was already poured out when I came in. Who poured it?"

"I did.... But if you'll look, he's hardly taken any of it—"

"But—but he had!" Celia burst out. "That is only water—I tried to give him some. But—but before that the glass was empty."

"Empty.... Evidently your uncle took his medicine—at the right time. He died just afterwards. And—"

The appearance of the doctor in the doorway made him break off. He took in the little group at a glance, and saw, too, perhaps, that there was something in the air.

"Sorry to hear this," he said soothingly. "Sorry to hear this. Shouldn't have thought it. Still, an invalid for years—"

"Dr. Wilton, I've told Mr. Mark Henstone that I think he should send for the police," Newley broke in.

"The police?" The doctor raised his eyebrows. "Now, why? I have been attending him and know the state of his health. Nothing wrong?"

He looked from one to the other. Newley was on the point of answering when he was interrupted. Kathleen Bramley had entered the room unnoticed. Now she stepped forward, pointing a trembling hand at Mark.

"He—he did it!" she burst out. "It wasn't Francis! It couldn't have been—"

"Did what, my dear young lady?" Wilton glanced at her through his thick glasses. "Really, there is no suggestion—"

"I'm afraid there is, doctor," Newley said quietly. "You've not examined Mr. Henstone yet. Just look here... Do you think death is natural?"

The dead man's glassy eyes were staring full at them. To Celia they seemed to be horribly big and open. Dr. Wilton bent down with an exclamation.

"You see?" Newley demanded. "The pupils—"

Wilton drew a deep breath. Without answering the manager, he stretched out his hand towards the blue bottle on the table, uncorked it, and smelt it dubiously. Then he nodded.

"I'm afraid," he said slowly, "there's some mistake... Yes... We must inform the Coroner at once."

"Then—then there'll be an inquest?" Mark asked, and his voice trembled a little. "There's something wrong?"

The doctor nodded. "There's something wrong," he said slowly. "The cause of your uncle's death was not his illness.... It was belladonna... I'm afraid, Mark, there's no doubt he was poisoned."

FROM the beginning it had been with mixed feelings that Superintendent Cary had viewed the death of James Henstone. A possible murder trial was sufficiently rare in the County to offer a certain thrill; but on the other hand, he could see himself faced with the unpleasant possibility of having to charge with murder a young man who, he believed, was incapable of any such thing. By the time he received the intimation that the expense of outside aid was to be incurred, he had carried the preliminary inquiries far enough to be worried for quite another reason, and it was with a certain relief that he welcomed the Scotland Yard detective in the room where Henstone had died.

Inspector McCleod was frankly puzzled. From the brief account of the case he had received, it seemed sheer absurdity that he should be there at all; and his thoughts found expression almost at once.

"If I may say so," he said, "I don't quite understand what I'm doing here.... Isn't there a clear case against Mark?"

Superintendent Cary smiled. It was what he had thought himself some twenty-four hours previously.

"The case being—?" he inquired blandly.

"Well—they were on bad terms. That very morning James seems to have said enough to provoke most people, and finally tells his nephew that he's going to disinherit him, Mark has the opportunity when he pours out the medicine. He knows about the linament. There's an obvious temptation. He probably knows the doctor too, and the chances of getting a certificate.... There's at least a prima facie case. Probably it can be confirmed in certain points—"

"It can... Mark's evidence admits most of that, of course. He's been remarkably frank.... In any case, we can prove the doctor had warned him about the linament; that his fingerprints were on the glass and the two bottles; that James had told him about the will. And yet—"

"What's wrong with it, then?"

Cary sighed. "Nothing," he said. "It's as good a case as it ever was, if not better. But it's like the ghost story in Kipling—a beauty if only one had stopped investigating soon enough. It was the confirmatory evidence that dished us."

McCleod raised his eyebrows and looked a question.

"Here," Cary selected a number of photographs and held them out to him, with two or three sheets containing the inked impressions of fingerprints, "you'd better look at these."

"There seem to be a good many of them?"

"That's it," Cary said grimly. "There are.... Of course we tested the bottles and so on. Of course we found Mark's fingerprints on them. Only we found a good deal more—as you can see."

McCleod had been examining the photograph, stopping from time to time to compare it with the impressions.

"Carlton's," he said after a pause.

"Yes. He's snag Number One... You see, he was in the room between the time the medicine was poured out and the time Henstone took it. He knew about the linament. After Henstone had told him he was sacked he poured water into the medicine. He admits that. Only"—he paused significantly—"only, he doesn't admit touching the linament bottle—and his prints prove he did."

McCleod frowned. "He denied it?"

"Very heatedly.... That's not all. Of course, at first we didn't think much about Carlton, because he so obviously loses if the will isn't signed. I thought there was something queer when he was speaking—but it was the Bramley girl who gave the show away. He went to see her after his visit here, and she let slip two things about the conversation. The first, that Carlton thought that the will had been signed; the second, that there was some mention of the medicine in their conversation."

"Ah," McCleod said thoughtfully. "Then—"

"It was that, I think, and not just to plead with Henstone before Newley came which brought her here. She wanted to see, before eleven o'clock, that the medicine was all right—and stop Henstone from taking it, if it wasn't. Only she was refused admission."

"That's rather conjectural, isn't it? Though it might be worth questioning her a little more fully about it."

"Which, at the moment, we can't do.... My interview with her ended in her having hysterics. Now she's temporarily unfit to see anyone. Got a doctor's certificate and so on. So she's got plenty of time to think up a good lie."

"So the position is this," McCleod said. "You've a good case against Mark. But you've an even better one against Carlton?"

"Yes. And whoever we charge, the defence is going to say: 'Oh, but the evidence is purely circumstantial. Why there's just as good a case against so-and-so'... In fact, to prove one of them guilty we've almost got to prove the other innocent."

"Which might be hard."

"It will.... And that's not all. Look at that photo."

McCleod obeyed. "It looks a mess," he said.

"It is. That's the poison bottle. Now, we expect to find Mark's, and they're there. Carlton's ought not to be there, but they are. The doctor took charge of it when he arrived, and so far as we can tell no one touched it. Those are his prints there.... The point is, whose are these?"

He pointed to a large, rough-looking line pattern, marked by a diagonal scar, apparently a thumb print, and to a fingerprint on the other side.

"Theoretically—you see the thumb overlaps Carlton's a little—the only two people who could have made them are Newley and Henstone himself. They're not a bit like either. Obviously they're a man's. But they're not Bembridge's, or Higson's."

"In fact, some time between Carlton's departure and the discovery of the body a completely unknown man somehow touched the bottle."

"Yes. That's not all, though.... Look at the glass. Those are Mark's—you can just make out a bit; those are Henstone's; those Miss Vernon's; those are Higson's. And that's all there ought to be.... Then, whose are those?"

"A woman's."

"Yes. But no woman ought to have been there. And she came some time before Miss Vernon." He paused. "Now, how about charging Mark or Carlton?"

"Of course, it's impossible.... You've no idea— Have you tried Miss Bramley?"

"That's just what we haven't. She threw her little fit before I could get on to that.... Well, after that, I got down to it pretty thoroughly, treating it as a completely open case, and just trying to find anyone who could have done it. First, of course, there's Newley. He doesn't seem to have a motive. There might be one connected with the business, and I'm having that gone into thoroughly. He doesn't seem to have touched anything—but any real murderer knows about prints these days. Henstone was asleep, so he could have done it. But there's no earthly case against him."

"Unless you get a motive. I see that."

"Higson. No motive; no prints. But he could have done it. His evidence pretty well makes certain that no one other than the ones mentioned came along the passage. It doesn't prove he didn't slip along either after Carlton or after Newley—"

"Just a minute.... If his evidence proves that, how did the two unknowns get in—the man and the woman?"

Cary jerked a thumb towards the french window. "We thought at first it was a closed shop business," he said. "That looks as though it's locked, doesn't it? Only the bolts weren't engaged. So you can just push the two doors open, in spite of the lock.... And anyone could have got in."

"Hardly. Unless Henstone was expecting them or knew them. He'd have given the alarm? Or when he was asleep."

"Yes. There's another point of course. This method of committing the crime really assumes a knowledge of household routine. So we can more or less confine our attention to people who knew it... Apart from those we've had, that would mean the staff. They're all accounted for. The only other two we've found so far are Bembridge and the doctor.... There's nothing against Bembridge at all. And the only point one can quarrel with so far as the doctor is concerned is that he seemed a little too ready to give a certificate."

"That's in Newley's favour. If he'd done it, why insist it was a murder?"

"And Miss Bramley's. She accused Mark too.... Well, there it is, and a very nice little mess."

"Miss Vernon," McCleod said thoughtfully. "You've not mentioned her."

"Didn't I? Well, there's not much to say. It's hard to see how she could have had a motive, having only been there a few days—"

"Unless she had one when she came?"

"She was engaged through an agency in quite a normal way. And there's nothing queer about her, except that she said the door was locked one minute, and the next it wasn't."

"Which was probably one of the mysterious visitors?"

"Yes.... Oh, there's one other thing. She did seem to gloss over the mention of Mark in Henstone's dying words. Made out that he was calling for his nephew, when in fact the actual words suggest an accusation."

"Of course. They're a distinct point against Mark. That is, they show that Henstone believed it was he... They raise a few problems too. Where's this place—Broughton House?"

"We've not found it yet. Of course, the spelling is conjectural... It might be Browton, or anything."

"And 'old will'... I thought that Henstone had never made one."

"It certainly seems as though he hadn't. What he said to Bembridge was: 'This is the first time I've ever put pen to paper on a thing of this kind. I hope there's nothing in the popular idea it means approaching death.'"

McCleod nodded his head slowly and reflected.

"I suppose," he said after quite a long pause, "you're sure that 'will' hasn't a capital letter?"

"Good lord!" Cary's jaw dropped. "You mean it might be a man's name?"

"Obviously. And perhaps the first unknown. It's worth looking into—among other things. The puzzle is, where to start."

"I thought," Cary suggested, "that the county police might start by trying to find this Broughton House place. Also we might interrogate people in the neighbourhood to see if we can trace either of the two strangers.... I expect our lads could do that better than you."

"I should be glad if you would.... As for me, I'd like to have a few words with all the main people a bit later. But first of all, I'd better wade through this."

He indicated a little ruefully the sheaf of reports and photographs.

"I'll leave you to it then," Cary said, rising. "Ask the sergeant if you want me.... Good hunting."

With the departure of the Superintendent, McCleod settled down to a task which the extreme conscientiousness of the local police had made a somewhat lengthy one. There were photographs of the body, the tray, the fingerprints, and various aspects of the room; there were interviews with everyone in the vicinity—a good many of them merely examples of misplaced zeal. McCleod worked with practised rapidity, making a note from time to time in the open book beside him. He was a long way from having finished when a discreet knock sounded on the door, and he was so immersed in his work that he looked up uncomprehendingly as the butler entered.

"Lunch is served—" Higson began and hesitated, perhaps uncertain as to a detective's position in the social hierarchy. "Lunch is served, sir," he repeated after a pause, "if you require it. Mr. Mark gave instructions—"

"What?" McCleod queried absently. "Oh. Lunch? Good idea. You're John Higson, the butler?"

There was distinct reserve in the bow which gave assent.

"Just been reading your statement, Mr. Higson.... Very clear on most points. It must have been a bit of a shock to you, wasn't it?"

A well-trained servant is one of the least responsive of persons when it comes to an attempt at luring him into conversation. Higson showed no sign of rising to the bait.

"A terrible affair, sir," he agreed soberly.

"You've been here some time, haven't you?"

"Just over six years, sir."

"A good place, I imagine, or you wouldn't have stayed?"

Apparently the butler had reconciled himself to the inquisition, though his manner was still cautious as he replied.

"The wages are good, sir, and the quarters very comfortable."

McCleod smiled knowingly. "From the way you put it, I gather there have been disadvantages. No doubt Mr. Henstone could be a little difficult at times?"

Higson hesitated. "Well, sir, Mr. Henstone was an invalid," he admitted.

"But I understood Mr. Mark dealt with him almost entirely?"

"That is true, sir, so far as little comforts were concerned. But, of course, not in waiting on him, or managing the staff—"

"But you and Mr. Mark were practically the only two people in the house who had much personal contact with him?"

"Yes, sir... Of course, he would see the housekeeper from time to time, and mention—mention anything that occurred to him. In fact, once a week, sir."

McCleod nodded. "I gather he kept quite a close eye on things," he suggested.

"Well, sir, he was interested in details." Higson paused. "More than I have been accustomed to, sir. But that was always his way, sir, with everyone—even with Mr. Mark or Mr. Newley. Not being able to deal with things himself, he required very exact accounts from everyone.

"Ah," McCleod said thoughtfully. "I wonder you stood it so long," he added rather bluntly.

"Well, sir—I liked Mr. Mark. And Mr. Henstone was an invalid—"

"Meaning just what?" McCleod asked. "That you could excuse him or that things might be better when he died?"

The butler hesitated but McCleod did not press the point. "You've noticed no change in him recently?" he asked. "He's not been worried or depressed?"

"On the contrary, sir. For the past few days he had been in exceptionally good spirits."

McCleod thought. "I don't like to say it," he said untruthfully, "but I rather understand that his manner was at times inclined to make people quarrel with him?"

"Not Mr. Mark, sir." The reply came a little unexpectedly. "He and Mr. Newley, sir, were the two people with whom there was never any disagreement... I am sure, sir, that Mr. Mark could not have been more dutiful if he had been Mr. Henstone's own son, sir—"

McCleod rose to his feet. "No doubt," he said. "Yes, I think lunch would be a good idea.... Just a moment. I'd better scribble a note for the sergeant."

Higson waited patiently, at least to all outward appearances. Glancing up unexpectedly in the middle of his writing, it seemed to the Inspector that there was a suggestion of disquiet behind his professional mask; but that, no doubt could be explained by his obvious loyalty to Mark.

"I shall probably have to ask your help quite often, I'm afraid," he said as he folded the sheet. "It's often most important in a case like this to know people's relationships with each other and I imagine you could tell me as much as most people."

The butler only inclined his head in assent, and led the way. Lunch, apparently, was served for the Scotland Yard man's especial benefit, though there was another place laid, and it was a lunch which, in view of his early departure from Town, McCleod would normally have dealt with faithfully. Instead, there was an unusually worried frown on his face as he consumed the food almost automatically, and it was still there when the Superintendent entered, obviously with the intention of joining him.

"Had a good morning?" he asked cheerfully.

"Been wading through your reports," McCleod answered. "I haven't seen anyone yet, except Higson... There are one or two I'd like to, though. Miss Bramley, Mark, Carlton, of course—"

"Afraid Miss Bramley's off the list for the moment... In bed with a nervous breakdown.... Oh, I had a doctor's certificate all right. I suppose it's just the effect I had on her!"

"Ah," McCleod said thoughtfully. "A pity." He looked round. "What did you yourself make of Higson?" he asked in a low voice.

"Why, he's all right, surely?" Cary asked in surprise. "I thought his evidence was very clear."

"It was," McCleod admitted. "Perhaps it's nothing.... Only I've a persistent impression I've seen him somewhere before."

"Seen him before? Where?"

"That's the annoying thing... I can't quite place it," McCleod said slowly. "But I've a sort of impression it was in the dock!"

SO far as Mark Henstone was concerned, there had been nothing particularly alarming about his interview with the Inspector. He had steeled himself for it, almost expecting that it would end in the production of a warrant and his immediate removal to gaol. In fact, it had seemed almost perfunctory. Of course, as McCleod had pointed out, he had already made a statement to Cary which the Scotland Yard man had studied. McCleod's own questions seemed to be concerned with ridiculous points of detail about the position of objects in the room; and since these were obviously recorded in the official photograph of the room, he could make nothing of them. Perhaps they were merely a kind of memory test; perhaps they concealed some deep trap which he had not detected. Somehow there was something a little alarming in the very blandness of his interviewer, and the avoidance of all the awkward points.

It was a long time that night before he could get to sleep. He found himself going over the interview in his mind again and again, and as he did so the wonder recurred to his mind why he had not already been arrested. Once, in the state between sleeping and waking, the horrible doubt crept into his mind that perhaps he had actually done the murder without knowing it. For, however calm he might have seemed, he himself knew that during certain moments of that interview he had been in a blind rage which hardly permitted him to control his actions.

Who was guilty? The question recurred maddeningly. In spite of the ill-feeling between them, he could not believe it was Carlton. That seemed to leave only Newley, and of all the people in the world, Newley was one of the few who would actually lose by his uncle's death. Who else could there be? For the twentieth time he had given it up and turned over in bed when he heard something that made him sit up suddenly.

What it was, he did not know. It was not quite dark in the room. A little moonlight from the dull semi-circle in the misty sky shone through the window, revealing at least the outlines of the furniture. Though he did not quite know why, he did not reach for the bedside switch. But he was almost sure that there was no one in the room. For two or three minutes he sat there listening, and there was not so much as the creak of old woodwork. Then, when he was on the point of lying down again, the sound came again, with an unexpectedness which made him jump.

"Tap!"

This time there was no doubt. It certainly came from the window, exactly as though someone had thrown a small pebble against the pane. For a moment he hesitated. Presumably someone outside was trying to attract his attention; but there was something so queer in the midnight summons that he felt an uncomfortable chill down his spine.

"Tap!"

The repetition decided him. In a moment he had slipped out of bed and crossed the room. Flinging the casement open, he peered out into the half darkness. His room was on the first floor, and with the low ceilings of the old house the distance to the ground was not great. Below him, a light patch showed the lawn, and he could even distinguish the outlines of the flower-beds; but there was no sign of any visitor. He leaned out a little further for a better view. Then something flew past his head, falling with a thud on the floor behind him.

He had ducked instinctively. For the moment, he had the wild idea that it was a bullet. But there had been no sound of a shot. Another pebble? The sound had not been sharp enough. With another vain scrutiny of the shadows outside, he gave the window up. Going down on his hands and knees, he started to grope for the missile, and over against the opposite wall he found it.

After all, it was a pebble; but not only that. There was paper wrapped round it, tied, apparently, with a piece of rag which came off as he pulled at it. A message, obviously. For a moment he hesitated; then made his way across to where his coat hung and found a box of matches. Bending low so as not to be visible through the window, and shielding the light as well as he could he struck one, and read the few lines the crumpled sheet contained.

"I am a friend who can tell you something to your advantage," the scrawled print began. "I must talk to you. Meet me at once on the terrace. Light cigarette at window for 'yes'. Your safety depends on it."

The match went out, but he did not strike another. There had been only two or three words more, and he had a guess at what they were. For a moment he waited, hopelessly mystified by the whole affair; half suspecting some kind of trap, and half tempted to take any risk if only as a means of putting an end to his own doubts. Quite suddenly he made up his mind. He had to know what it meant. Stepping back towards the window so that he would be in complete view of anyone watching from below, he felt for his case, and went through the motions of lighting one as he had been instructed.

There was no answering signal. Apparently the sender of the message was unwilling to reveal his whereabouts to anyone who might be looking out, small though the chance might be. Or perhaps he was waiting for the agreement with his proposal to be translated into action. The best way of finding out was to go. Slipping on dressing-gown and shoes, Mark opened the door silently and stepped out into the passage.

There was no special need for caution. His bedroom, since his uncle's death was the only one occupied at this side of the house. The only difficulty might be the staircase. Higson, he knew by experience, was an abnormally light sleeper; there was a strong probability that the least accidental noise would wake him. Then he remembered a window at the far end of the passage. An outhouse roof below had made it perfectly practicable for him as a boy, and there was no reason why it should not serve him now. He retraced his steps towards it.

It was merely a question of lowering himself a few feet from the window-sill, and though the tiles were slippery with dew and creaked ominously under his weight he crawled along safely, and reached without mishap the point where a water-butt made a convenient step to the ground. He paused for a moment to listen. The night was utterly still; the house behind absolutely dark and undisturbed.

His unorthodox exit had brought him to the back of the house. The sender of the message would, presumably, be in front. He started to make his way round to the terrace, expecting at any moment some dark figure to emerge from the shadows. But he reached the corner without a sign of anyone, and stood for a moment shivering in the cool air as he looked about him.

The patch of shadow cast by the house obscured the whole pathway along the foot of the wall. If anyone were waiting there, Mark decided, he would have to go along the terrace in order to see him. Abruptly the folly of his hasty action came to him. Discovery would certainly add to the suspicions the police already entertained. There was always the possibility that the message was intended merely as a decoy so that he could be attacked. But why should anyone want to attack him. He decided to settle things one way or another. Moving with the greatest caution, and ready for anything, he started forward.

More than half-way along, he came to a sudden halt. From the far end, in the other wing of the house, he had caught a single glimpse of a light. It was not bright, hardly more than a glow, and it vanished almost instantly. The thought crossed his mind that it might be a signal from the man whom he was to meet. Then he changed his mind. The light seemed to come from inside the house. Then the matter was put beyond all doubt. The light came again, this time shining steadily, and he caught his breath in a little gasp. The glow undeniably came from a window—the window of the room where his uncle had died.

He shivered a little as he stood there, and the shiver was not entirely due to his inadequate costume. There was something a little unnerving in the glow of light coming from the one place where it seemed completely impossible. He knew that the police had locked and sealed the door of that room. No one could be there. Then he saw something else. For a moment the light glinted on the white hair of a man's head at the edge of the window, as though its owner were cautiously peering inside.

Suddenly the light vanished. From the house came a woman's scream. A dead silence lasted for half a minute; then turmoil seemed to break loose.

Running feet sounded on the flags, coming towards him. A darker patch moved in the shadow. He dived for it. As he did so, the toe of his loose slipper caught a projecting stone and he fell headlong, half stunning himself. Someone ran by him as he lay; then from the house came an indescribable din.

For a moment he could not place it at all. It was a brazen, persistent clamour, as though a whole tribe of cymbal players had gone mad. Then he recognized it with a slight shock. It was a gong—no more than the gong which on ordinary occasions signalled dinner-time. But now it was beaten wildly, evidently as an alarm.

He jumped to his feet. Someone was running in the drive below. As he set off in pursuit, he was aware of the house lights blazing up one after another and of the front door opening. Someone came running behind him, but he did not trouble to look round. All at once he was conscious of a figure very near him. In that instant a pair of arms gripped him, and he and his assailant crashed together.

From the beginning he had no chance. His opponent had fallen uppermost, and Mark was winded. Besides, the other was as strong as he was, and had science. After an absurdly brief struggle he was lying on his back in the drive, with someone kneeling on his chest. He heard the man's heavy breathing. The gong's clamour had stopped, and the night seemed unnaturally still.

"Who—who's that?" he panted. "What—?"

A light flashed quite near him, swept the gravel for a moment, and finally focused upon him. He heard a voice from behind it.

"What's this?... Oh, you, Brooks... What—"

"Got one of 'em, sir!" his captor announced triumphantly. "I cackled him as he bolted—"

"Let's see." The second man stepped forward and the torch shone full on Mark's face. "Good Lord! It's Mr. Mark—"

A wave of anger swept over the young man, perhaps more at the helplessness of his position than anything else.

"Let me up, you fools!" he snapped. "It's an idiotic mistake! You've let them get away!"

The man with the torch hesitated. "Right, Brooks," he said, and the pressure on Mark's chest was removed. He scrambled to his feet, sore and shaken. "Not a sound of 'em," the man with the torch was saying, and now he recognized the voice as that of the detective-sergeant. "They've got away... While we were messing about here... What the devil was that noise inside?"

"I'm sorry, sir—" Brooks apologized.

"You couldn't help it." He turned to Mark, speaking in a voice which was respectful enough, but had a distinct note of command. "Would you please come up to the house, sir? Perhaps we can find out there what's happened."

Mark followed without any answer but a grunt. His right leg was distinctly painful, and he had the feeling that they had muddled things badly. A challenge rang out as they neared the door.

"Who's that?"

The sergeant's torch flashed. It revealed the pyjama-clad figure of Higson, still retaining a certain dignity, in spite of his costume and the poker in his hand. He stood blinking in the light, but with a defensive attitude a little to one side of the entrance.

"Police— Oh. It's you, is it? You'd better come in... They got away."

A crowd of excited servants in all stages of undress filled the hall. Mark left the police and Higson to deal with them. He was feeling horribly puzzled and confused, and a cold certainty was growing in his mind that his part in the night's happenings would somehow be turned into evidence against him. He made up his mind to say nothing of the mysterious visitor and the note. He was trying to work out a plausible and consistent story omitting this vital fact when the sergeant at last returned, followed by Higson and Celia Vernon, both very white and shaken.

"Well, sir. Perhaps you could tell us what happened?"

"That's just what I can't," Mark rejoined. "I couldn't sleep. I got out to get a cigarette, and happened to look out of the window. I thought I saw a man prowling about in the garden, and I decided I'd better investigate. So I let myself drop from the passage window, and came round—"

"You didn't rouse the house, sir?" the sergeant prompted dubiously.

"No. Thought my best chance was to go quietly and nab him... There wasn't a sign of him until I got to the front. Then I saw a light in my uncle's room—the room where he died."

"What, sir?"

This time he had certainly interested the sergeant. He did some quick thinking, and decided to cut out all mention of the white head at the window. In all probability, that was the man who had sent him the note.

"There's no doubt that's where it was," he affirmed. "I started along the terrace towards it, and it went out. Someone ran past me, and I made a grab, but tripped—"

"Just a minute, sir," the sergeant apologized. "He moved over to the door, and seemed to be holding a whispered conversation with someone just outside. There was the sound of retreating footsteps, and he re-entered the room. "And then, sir?" he asked as if there had been no interruption.

"I heard someone running in the drive, and I gave chase. Then the noise started in the house... I suppose your man got me? How on earth did you happen to be on the spot at the critical moment?"

"Just luck, sir," the sergeant evaded. In fact, he had spent the best part of the night in making certain that Mark, among others, should not obey any impulse to disappear. "You didn't see anyone, sir?"

"Not plainly," Mark said a little hesitantly. It was his first actual lie. "Not to see anything recognizable, I mean—"

"You'd some idea, though, sir?" The sergeant noticed his doubt.

"No, really... None."

The sergeant looked at him for a moment; then turned to Higson.

"And you?" he asked.

"I was awakened by a noise downstairs.... I am a very light sleeper, as Mr. Mark knows, sir." Mark nodded. "I went down, and as I was on the stairs, saw a gleam of light along the passage—"

"From Mr. Henstone's room?" the sergeant demanded.

"I'm almost sure it was, though it was only for a minute. Well, I knew that room was locked, and anyone inside it must have forced an entrance—I'd previously spoken to Mr. Henstone, sir, about the window. I was wondering what to do, when I heard a slight noise behind me. Then the gong started. I ran out, hoping to catch whoever was in the room."

The door opened to admit Brooks, who simply shook his head in a hopeless way. The sergeant frowned and thought for a moment; then he turned to the secretary. "And you, miss?" he asked with a trace of resignation in his voice.

"I couldn't sleep either. She was the most self-possessed of the three, and the only one who looked passably presentable. In fact, it occurred to Mark for the first time that she was actually quite pretty. "I got out of bed to open the window, and saw the light below—"

"From Mr. Henstone's window, miss?"

"I'm sure it was... That's why I thought I'd better see if things were all right. I crept downstairs—"

"You didn't give the alarm, miss?" the sergeant asked dubiously.

"Well—it might not have been anything."

The sergeant sighed. "Yes, miss?"

"I saw the light in the passage, but I didn't know what to do. You see, it might have been the police. On the other hand, if the door was locked and I tried it, whoever was there might have got out. I thought I'd better get some help. I was going back, and someone moved right in front of me—"

"Mr. Higson, miss?"

"I suppose it was... I thought it was the burglar. I daren't move. The only thing to do seemed to be to rouse the house. The gong was just near me—"

"Then it was you who sounded it, miss?"

"Yes."

"Just why, miss?" The sergeant sounded puzzled but patient. "I should have thought you'd have called out—"

"I thought whoever was ahead would grab me before I could make anyone hear. The gong was an inspiration. I felt sure it would wake people."

For a moment words seemed to fail the sergeant. He looked from one to the other.

"Well, miss," he said heavily. "It did."

CALLED out of his bed in the small hours, McCleod had already put in a good morning's work by breakfast-time, and he was just on the point of finishing that meal when Cary entered. The Superintendent had been up as long as the Inspector himself, and as he poured himself out a cup of coffee was plainly not in the best of tempers.

"Any luck?" McCleod asked, feeling for his pipe.

"Nothing... And I've just had a sweet little interview with the Chief. Must be suffering from liver or something. Can't understand how it could happen while we were actually investigating the case—inefficiency in the police force—doesn't think that Superintendents ought to sleep. Oh, and old Bembridge got on the phone.... Didn't like the way we were watching his client Mark or something. I pointed out that what had happened proved that there was need to watch, and he said it didn't seem to have made much difference."

"Perhaps it didn't," McCleod admitted ruefully. "It's a pity, certainly, that the man watching was at the other side of the house.... Then you've not located any strangers?"

"No one we can lay hands on.... A white-haired old boy who looked like a tramp was about here yesterday, but he seems to have vanished into thin air. I can't find that he lodged anywhere.... Any luck here?"

"Not much... First of all, unless I'm mistaken, there were two burglars, not one."

"What?"

"Seems fairly certain. Number One was a hob-nailed chap, who seems to have executed a kind of step dance under Mark's bedroom window, then walked along the terrace to have a look at Number Two. His little footsteps are pretty plain... Number Two was more professional. He wore rubbers, and seems to have known all about how to work the french window. Though what he did inside the room I can't say. He didn't leave any prints."

"They came together," Cary suggested. "Hob-nails did sentry-go outside, while Rubbers did the burgling."

"They came separately, and from different directions," the Inspector corrected him. "There are enough tracks to show that. And I've an idea that Rubbers wouldn't have been a bit pleased if he'd known that anyone was peeping in on him... Now, what Rubbers wanted is fairly obvious. He must have intended either to have taken something away from that room or to have put something there—"

"To have put something there?"

"He might have wanted to plant a bit of evidence. If he did, I can't find anything. Nor does anything seem to be missing. Of course, I couldn't look in the safe or the desk."

"Presumably he couldn't, either," Cary suggested. "So far as the safe's concerned, only Henstone had the combination. We've sent for a man to open it. So far as concerns the desk, it's got a pretty good lock—because I thought of opening it myself—"

"It's not been forced?"

"No signs of it.... You said you'd bring the keys?"

Cary felt in his pocket, and threw the bunch on the table.

"We'd better look into that next," he suggested. "It's a pity we couldn't do it before."

"Of course. We can't be sure that something's not missing—or been put in.... Though I went over the locks with a magnifying-glass, and I'm pretty sure he hadn't time to do it."

"Anything else?"

McCleod felt in his pocket, and placed on the breakfast table four small pebbles and a piece of rag. Cary eyed them without enthusiasm.

"What's that?" he asked. "Where did you get them?"

"Two on the terrace—otherwise stoneless. One on the window of Mark's room—on the sill outside, that is. One in Mark's room, with the rag."

"Mark?" Cary frowned at them. "What are they for, anyhow?"

"I think they mean that, last night at least, Mark departed from the strict path of truth. If he didn't sleep, it was because someone chucked pebbles at his window. If he went out, it was because someone threw a message in, tied with the rag, asking him to go out. I'd like a word with him, later." He thought for a moment. "Oh, the butler is notoriously a very light sleeper. I don't know about Miss Vernon. Perhaps that is the idiotic way in which she would behave. Nothing else, I think."

Cary gulped down a last cup of coffee. In contrast to McCleod, he had made a poor breakfast. He took out a pipe, eyed it distastefully before replacing it, and finally lit a cigarette.

"And generally if there's one time I enjoy a pipe, it's after breakfast," he said mournfully. "Suppose we have a look at the desk?"

McCleod led the way. The night's adventures had apparently made no impression upon Higson, who greeted them as they passed through the hall.

"That chap's a bit too much always on the spot," Cary growled as soon as they were out of earshot. "You can't move a step in the damn place without his seeing you.... Get any news about him?"

"Oh. I meant to have told you. Yes. Did six months when I was a bobby in London. I got him them.... Now, I've an idea he recognized me when I first saw him. But I'm pretty sure he doesn't know that I've spotted him."

"What for?"

"Larceny... Of course, there's nothing we can charge him with. He served his time, and if he made good afterwards, good luck to him.... Only, if Henstone found out anything, it might have been a motive.... You've got the key?"

Cary unlocked the door and they entered. So far as one could tell, the room was exactly as they had left it the previous day, except that a box had been placed on the strip of lino under the french window. McCleod lifted it, to reveal an indistinct muddy patch.

"That's Rubbers's only trade-mark," he said. "Crepe sole. Fairly normal size. Pretty hard to identify... No other trace at all."

Cary stood looking round. For a moment his eyes settled gloomily on the safe; then they switched to the desk which formed the immediate objective.

"Handy bit of work, isn't it?" said McCleod. "You see, it will swivel right out, so that he could get at it without moving. He got things very nicely fixed for himself on the whole. I won't say he didn't like to bother anyone—but he didn't like to rely on anyone by all accounts."

"And he certainly didn't trust anyone.... Well, let's have a look."

He produced the keys, and unlocked in turn the two rows of drawers.

"You take the right side, and I'll take the left," McCleod suggested. "Of course, we can't go through this lot properly now. If we can just get a rough idea, and sort out anything that looks at all possible—"

It was an illuminating collection which showed the dead man in anything but a favourable light. All the documents in it were purely personal—letters from relations, copies of letters to relations, a few, very few, from friends, and a good deal of information which could only be classed as libellous about the people concerned. It had apparently been the habit of Henstone to collect dossiers about the various people with whom he had to deal, in which were recorded in particular all the facts, or pieces of gossip, which could conceivably react to their discredit. Cary looked up with a disgusted face.

"Did you ever see anything like it?" he asked. "Keeping all this stuff—"

"Yes... I mean, I have seen stuff like it," McCleod answered. "In a blackmailer's little library."

"You don't mean that Henstone—"

"We've no evidence that he did.... No, I think all this is quite in keeping with his character. Not having many good impulses himself, he liked to know the worst about other people... We'll put them aside. Might come in useful—"

"Here's something," Cary said after a minute. He held out a book labelled "Diary". "Now, if he really kept that up to date—"