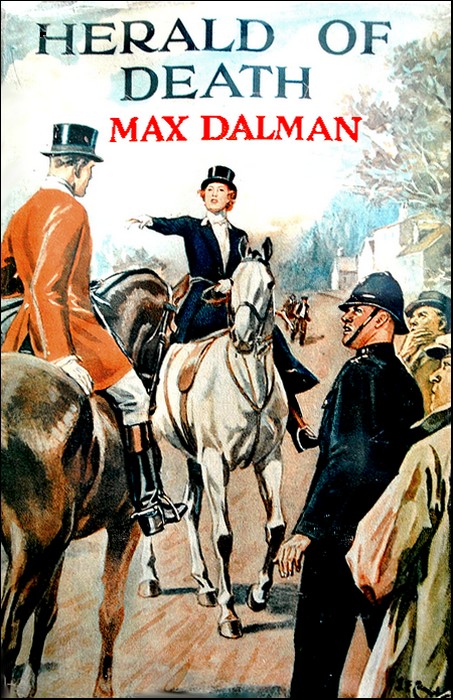

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Herald of Death"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1943

Set in the English countryside, "Herald of Death" begins with a chilling twist: an anonymous note warns of a murder before it happens. The victim, Richard Marney, is fatally stabbed with a silver dagger during a fox hunt. Suspicion falls on Hugh Egmont, who harbors jealousy over Richard's closeness to their cousin Joan.

Enter Inspector Lyly. The Scotland Yard detective faces a tangled web of clues, red herrings, and eerie reports of something supernatural roaming the lanes. His investigation is further complicated by Mrs. Constance Handley, a local mystery novelist with a knack for meddling.

WITH a sigh Constable Retters pushed aside the letter he had just read and reached for his cup. It was not often that he could enjoy the luxury of the morning mail at the breakfast table; for it reached the police station at a quarter to eleven, an hour by which even the representative of law and order in a village of some five hundred inhabitants should long since have been abroad. But that day he had every excuse both for lateness and for depression. He had been up all night in fruitless watch for poachers at the Grange; only to hear from the milkman that they had raided Sir John Marney's coverts and got away clear.

Certainly the post brought him no comfort, so far as he had dealt with it. Of all things he hated women's quarrels most, more particularly about pets or children. He sighed again as he put down his cup; then caught his wife's inquiring eye.

"It's Miss Miller," he vouchsafed. "Her old cat."

"She's an old cat herself," his wife rejoined. "Someone poisoned it?"

"It's had a fight." Retters glanced at the letter. "Terribly mauled, she says... Savagely attacked without provocation by a tabby belonging to Mrs. Handley in her own asparagus patch. She's confined to the house—"

His wife sniffed. "Who?" she asked.

"The cat, I think... Yes—at least, 'her tail had to be bound up.'... She wants me to see about it."

"Wants you to sit on the doorstep and shoo it off, I suppose?... Mrs. Handley may write, but she is a lady."

Retters nodded, and buttered a last slice of bread. "Comes of a good family," he said. "Blood tells."

His wife laughed. "How about the cat, then? Miss Miller's is pure Persian, and the tabby's a rat-tailed mongrel... What's the other?"

Retters eyed it gloomily. The address was roughly printed in block capitals and from that he augured the worst. It looked like an anonymous letter, probably abusive, or revealing some fictitious crime which would occasion endless bother without result. He wiped his fingers on his handkerchief and ripped the flap. His wife's eyes were on him as he read. She saw his jaw drop, and his eyebrows rose.

"Good Lord!" he said blankly.

He finished the sheet without further comment, and started to read it again, frowning as he did so.

"Well, John William?" his wife demanded. "What is it? Not struck dumb, are you?"

"Pretty near!" Retters responded. "Darned if I know what to make of it... Must be from a lunatic. It doesn't mean anything that I can see."

His wife peered vainly over his shoulders. Her glasses were upstairs and the half-dozen lines of print were the merest dark blurs.

"Read it out, then," she commanded. "Maybe if you can't see it there may be some sense in it."

Retters ignored the slight. He cleared his throat, and frowned more fiercely.

"'They found in the morning, but did not kill'—that's how it begins," he said. "'Death ends the run where the stream flows. Gules upon gules, and argent on azure. The sitting lion looks for its cub in vain.' That's all. No signature, of course... Pretty daft, eh?"

His wife sniffed. She did not like to agree, but could not deny it.

"Ghouls?" she said, and wrinkled her forehead. "Those that rob the graves? It was on the films."

"That's spelt different," Retters corrected. "G-u-l-e-s, this is. It means, well—it means—"

He broke off, wrestling with the feeling that he had met the word somewhere before; but the memory eluded him.

"About the hunt, is it?" his wife suggested. "Some of those anti-blood sports people? There was a meet at the Hall to-day... But what's that about the lion?"

"It's a lot of nonsense, anyway," her husband decided; but he gave another uneasy glance at the sheet. "Some fool trying to be clever. Or he's a bit touched."

"Not Little Jim?" His wife shook her head. "He's the only half-baked one here—really half-baked... No, it wouldn't be him. It's an educated kind of lunatic, that's plain enough."

"And they're common," Retters said sourly, and glanced at the clock. He folded the letter carefully and rose to his feet, buttoning his coat. "Better see about this darned cat, I suppose. You know what the old girl is. She'll write and complain... But gules... Now, I wonder what 'gules' are?"

He was still wondering as he started up the one long street the village boasted. The letter might be nonsense, but he was a man with a conscience, and, moreover, with ambitions. Every rural problem which came his way he sifted with a thoroughness which rather annoyed the local inhabitants and certainly amused his superiors, and this was out of the ordinary. Somehow the mysterious word lingered in his mind with a sinister significance. He was almost sure it had something to do with Shakespeare; but his acquaintance with the classics had ceased when he left school. Obviously Mr. Judkin, the local schoolmaster, was the proper authority to consult; but only the previous week he had reported him for riding a cycle without a lamp and ill-feeling still remained. There was the vicar. He played with the idea for a moment and dismissed it.

He had nearly reached the post office before he met anyone; and when he did the meeting was scarcely to his taste. Unless he was very much mistaken, Joe Wallis had been a member of the poaching party who had successfully evaded him the night before, and a forbidding frown gathered on his face. Ordinarily, the poacher would have greeted him with a triumphant grin, or a look of apprehension, according to the degree of security he felt; but to-day his manner was puzzling. He looked as though he was going to speak, seemed to think better of it and went on, and there was something in his face Retters did not understand. He turned to look back at him, and detected the poacher in the same act.

"Morning, John."

This time Retters nodded in response. Sergeant Ker, late of the Royal Engineers, was one of the few people in the village in whom he could confide, and the problem of the letter recurred to his mind.

"Fine morning, Sergeant," he replied. "Seen the hunt?"

"Out Barden way, and going well." Ker grinned. "But the Cliff will puzzle most of 'em. Heading that way, they were."

"The Cliff?" Retters echoed. He was well enough acquainted with the district to know the almost legendary fame of the difficult jump the name referred to. "Not many try that, I should think."

He glanced longingly over the hedge in the direction of which the sergeant had spoken. Had his official position permitted it, he would have enjoyed a day following hounds; as it was, all he could do was to intervene when humane enthusiasts attempted to interrupt it, as had happened on several occasions recently. Then the letter came into his mind, and he frowned.

Ker noted the expression. "Busy?" he asked.

"Cat fight," Retters said gloomily. "Miss Miller and Mrs. Handley."

The sergeant guffawed. "Two-legged, or four?"

"Both, I reckon." Retters allowed himself a rueful smile. "But that's not what's bothering me. Sergeant, what does 'gules' mean?"

"Sort of wild men?" Ker hazarded. "In one of those comics?"

Retters shook his head. The word had some more high-brow meaning.

"If my boy was here, he'd know," Ker asserted proudly. "I heard from him yesterday—"

The constable groaned in spirit. Paternal pride was a failing of the sergeant's. The clatter of a horse's hoofs behind offered an escape, and he turned to look.

"Hullo, it's young Mr. Egmont. Missed the hunt, has he? Looks fed up about it, too."

Ker nodded assent. There was no doubt the young man was not in the best of moods. There was a savage scowl on his face, and he was riding at a pace which the tarmacadam underfoot made inconsiderate if not reckless.

"Proper mad, I'd say," the sergeant decided. "His father's bad temper, he's got... A perfect terror the old man could be when his blood was up. Finest shot round here, though. And Mr. Hugh takes after him in that as well."

Retters mentally agreed. He remembered old Henry Egmont well enough, and had even had experience of his irascibility on first coming to the village; and judging by his present expression the son had undoubtedly inherited the less amiable side of his father's character. He saw the two men standing there and rode towards them, pulling the horse to a halt viciously and cursing as it registered a protest by attempting to rear.

"The hunt?" he snapped. "Seen it?"

"Gone Barden way, sir... Wonder you didn't see it if you've ridden from the Grange? You must have crossed the route, sir... I was saying to Retters not many would face the Cliff. Mr. Richard, maybe, now that you're out of it."

The young man's frown deepened. Both men knew why. Probably it was no secret to anyone in the village that Hugh Egmont had only two things in common with Richard Marney, a love of hard riding and an admiration for the latter's cousin. Neither, as things had turned out, had proved conducive to friendship. The knowledge that besides missing the meet he had also missed a chance to excel in front of Joan Marney could scarcely be expected to relieve his irritation.

"The Cliff?" he said. "Any chance of catching them?"

"Not a chance, sir—unless he doubles... A good scent, too, from the way they were going... You're late, sir!"

Egmont shot him a savage look. No one else in the village would have ventured to ask the question in the young man's present mood, but Ker was a privileged veteran.

"Yes," he said briefly, and turned his horse as if to go on. Then he seemed to think better of it. To the surprise of both men he actually volunteered an explanation. "Got a message saying the meet was cancelled. A job for you, Retters. Find the hoaxer!"

"A hoax, sir?" Retters pricked up his ears. "How was that?"

"Never mind. I wasn't serious... Look here, Retters, I don't want you poking your nose into this. I'll deal with it myself all right."

Retters was inclined to resent the tone; but he forbore to say so. And he was curious; but something in Egmont's face warned him that any curiosity was not likely to be gratified. The young man raised himself in his stirrups to look over the hedge, The hill on which the village stood commanded a view for miles over the rolling agricultural country which surrounded it, dotted here and there with copses already yellowing with the approach of autumn. His gaze was concentrated on the dark line which marked the Cliff, but there was no sign of what he sought. In the clear morning air every detail was visible right away to the golden folds of the downs on the horizon, and he studied the landscape carefully. It was a minute or two before he was rewarded. A scarlet dot, followed by a scattered line of red showed between two of the scattered clumps of woodland and disappeared again. He grunted and his jaw tightened a little. Then he subsided into the saddle.

"No good," he said. "Miles away. Well—" He broke off, and his face was not pleasant to look at. "Miss Marney there?" he demanded after a pause.

There was an eagerness in his voice which did not escape the sergeant. With a trace of malice he answered the question in a way which was likely to be very unpalatable to the man who asked it.

"And her cousins, sir. Mr. Maurice and Mr. Richard—"

He stopped. The effect of his words had been greater than he had intended. Egmont seemed to whiten with anger, and his hand clenched on the riding-crop. Ker hastened to pass over the indiscretion.

"You had the poachers your way last night, sir?" he asked.

It was half a minute before the young man answered. "Yes," he said in a strained voice and laughed abruptly. "You were on a wild-goose chase again, Retters, I hear."

"Well, sir, we can't be right every time." Retters was distinctly nettled. Simply because Egmont had seemed to want to keep it to himself, he returned to the subject of the false message. "A hoax, you said, sir?" he asked again, "That's queer—?"

"What the devil d'you mean?" Egmont snapped; then seemed to repent his outburst. "Queer? Yes. Damned queer—as someone will find."

With a boldness which was almost inspired, Retters's hand went to his tunic pocket.

"I mean, sir, it was queer, because I've had a sort of a hoax myself this morning. About the hunt, too."

"Oh?" Egmont said discouragingly; then his interest quickened. "You say about the hunt?"

"That is, I suppose it is, sir... I had a letter, but I can't rightly tell what it does mean. It sounds like a—like someone a bit unbalanced, sir."

Temporarily Egmont's temper seemed to have subsided. There was a trace of amused interest in his manner as he accepted the letter which the constable held out.

"Let's look," he said. "A mystery, eh?"

"Anyway, it's queer, sir... There's one bit that worries me. Maybe you can remember, sir—"

"Anonymous, is it? And printed. Quite in Mrs. Handley's line—Poison Pen stuff."

Retters smiled a polite assent; but his eyes were fixed on the speaker eagerly. He was not quite sure that he liked having his own particular puzzle classed with the rather lurid detective stories written by the owner of the rat-tailed mongrel; though he read her works with interest and not without a wish that reality could more resemble fiction. Egmont frowned at the paper.

"Pretty fair balderdash, isn't it?" he commented. "Writer must be off his head... What's your trouble?"

"'Gules,' sir... Shakespeare, isn't it?"

Apparently it was Egmont's turn to rack his memory. At the university he had been more prominent on the river than in the lecture-room, but a hazy recollection persisted. His face cleared.

"Got it!" he said. "'Now is he total gules.'"

"That's it, sir!" Retters in turn recognized the line. "But what does it mean, sir?"

"Bloody—in that bit. It's heraldry. Gules is red. Argent is silver... It's not me you want. Mr. Charles Marney, now. Or old Norton at the post office. He's a whale on that stuff, isn't he? But red on red? And silver on blue? That's neither sense nor heraldry. And this sitting lion stuff—"

He broke off suddenly. A queer look came on his face, and he looked again at the sheet. His lips moved as he studied it with a curious eagerness. But he handed it back without a word, and the frown returned to his face.

Retters had missed nothing. He was fairly sure that the young man had understood more than he said, and both his professional and his natural feelings prompted him to find out what it was.

Egmont's manner was forbidding, but he risked a question.

"Yes, sir? The sitting lion—"

Egmont shook his head. "Lot of damned nonsense," he said. "I'd burn it, Retters."

"You're sure you can't help, sir?" Retters insisted. With peculiar care he folded the paper and returned it to his pocket. "It might mean nothing, of course. But when this letter business starts you never know where it leads, sir."

"Sorry. I can't." His tone dismissed the subject. "Heard from your boy, Sergeant? I hear—"

He broke off, looking up the street over their heads, and his face brightened. Ker glanced over his shoulder.

"Why, it's Miss Joan!" he exclaimed. "You don't think she's had a message—?"

But the policeman had noted the mud-stained habit and the slight limp of the horse.

"She's come a cropper somewhere," he said. "Wonder if she tried the Cliff herself? She's spirit enough—"

Perhaps the same thought had occurred to Egmont. He had not stayed to listen, but started forward to meet her, and the smile on his face found an answer on the girl's as they met. Ker looked admiringly at the wind-blown hair and flushed cheeks. If she had fallen, she did not seem to be much hurt.

"Not much doubt how things stand there?" he suggested. "He's gone on her all right. And she doesn't exactly hate him either."

"Don't know." Retters objected. "I'd say her cousin was the favourite if you ask me. Playing the two of them, she is, and neither is the kind to stand it. There'll be trouble yet, you mark my words... But I wonder what got him about that letter?"

Ker had lost interest in that mystery. He was watching the two as they turned and came towards them. The girl was shaking her head and laughing; but Egmont's own smile had vanished. He looked anxious.

"I leave that to you and Dick," she was saying as they came within earshot. "It was a mere rabbit-hole, and I fell soft at that... I expect Dick tried it alone."

Her tone was provocative, and obviously it had its effect. Egmont was scowling at his horse's ears, and did not see the mischievous look she directed at him.

"I'd have been there," he growled. "But for that... I can guess who it was."

Two bright spots of colour flamed in her cheeks and her eyes flashed warningly.

"Dick didn't, if you mean that!" she said hotly. "There's no need to be mean and ungenerous, Hugh."

"Look here, Joan," Egmont raised his head suddenly, "I can't stand this—"

The rest of his words were inaudible to the two listeners; but from her defiant glance they could guess the retort her lips formed.

Ker turned to the policeman and shook his head.

"It looks as though—" he began; but he was interrupted.

"Retters!" The shout came from behind them. "Hi, Retters! Here, man!"

At the urgency in the call the policeman turned sharply. A little group of men had emerged all at once from the farm lane beside the shop. As he looked they broke into a run. Retters recognized the man who had shouted; then at the sight of his pale face he himself started to hurry towards them.

"What's up, Mr. Nicholson?" he demanded. "Something wrong?"

For a moment the farmer made no reply. He was out of breath, but also he seemed as though he was searching for words.

"It—it's a bad business, Retters," he said at last. "It's Mr. Richard Marney—"

The constable heard the girl behind him give a little cry of alarm.

"He's hurt?" he asked.

"Dead," Nicholson said soberly, and again hesitated. "Dead when Joe found him."

"The Cliff? He fell?"

Nicholson took a deep breath and shook his head.

"No," he said with an effort. "Worse than that... It's a job for you, Retters... He didn't die of any fall, that's certain—"

He stopped. Incredible as it seemed a suspicion of the truth dawned upon the constable's mind.

"Lord! You don't mean—?"

"Stabbed," Nicholson said, and for a moment his glance wandered to the young man who sat rigidly on his horse staring down at them. "It's murder all right... With a silver dagger—"

"Murder?" Retters echoed. "Good God! Mr. Richard—?"

"You—it was you! You did it!"

As the girl's cry interrupted him, all eyes turned towards her. White-faced and trembling she was staring at Egmont, one hand outstretched accusingly. Retters saw the young man wince; then his jaw set grimly.

"You—you hated him! You were jealous—because, because—"

Sergeant Ker jumped forward just in time to catch the fainting girl as she slid senseless to the ground.

TO an ignorant observer, it might have appeared that local legend had exaggerated the perils of the sharp declivity known locally as the Cliff. It was no more than the steep side of a little valley carved out by a stream scarcely larger than a brook which trickled through a ragged copse to join the river a half a mile away. But for a rider the combination of drop, stream and brushwood was dangerous enough. Midway, a few footholds had been cut to allow a pedestrian to scramble down fairly easily to the stepping-stones below, and just beyond lay the only point in its five hundred yards of length where even the most courageous rider might hope to achieve a crossing.

Stories had gathered round it. There was, indeed, an apocryphal tale of a famous highwayman saving himself from pursuit by making the jump; but there were more recent and definite instances of people taking the leap. Six had been known to do it successfully, and two without success; but Egmont and Marney had shared the distinction of being the only two men living who had tried it, and a year before Marney had paid for his boldness with a broken collar-bone. Perhaps the foxes knew of its difficulty; for they headed in that direction with a perverse frequency which suggested they did not enjoy being hunted half so much as is sometimes suggested. Then the less-dashing members of the hunt had to make a considerable detour by way of the road and bridge; while normally the fox sought cover in the thick undergrowth covering the flat and the more gentle slope on the other side.

From the village the footpath crossing the valley was not the nearest route to the spot where Marney's body had been found; but it was the way Retters chose. From a telephone conversation with his superiors, he had gathered that his hour as a detective in a murder case was likely to be a brief one; his orders were "Occupy till I come"; and his task no more glorious than to see that as little as possible was disturbed. For solo investigation, he had exactly the short time which must elapse before the arrival of the Chief Inspector from the neighbouring town, and he was determined to make the most of it. The footpath would bring him to the point from which Marney had made his leap, and from there onwards he would be following the track of the murdered man.

To the disappointment of an over-numerous body of volunteers, he halted the whole party just short of the descent, advancing himself with only Nicholson as guide and Sergeant Ker as an unofficial deputy. In the soft ground the tracks of the hunt were plainly visible, and Retters thought that they might be important.

"It's plain enough what happened here," Ker suggested. "The fox was running parallel with the valley; then it turned along the path to cross and the hounds followed. There's where one man jumped—that would be Mr. Richard. The others would ride straight on, cross by the bridge, and strike over the fields to catch up."

Nicholson looked dubious. "Don't know," he said. "Looks as though some of them came to the edge all right."

"That'd be just to see if Marney made it. If he did, they'd go on."

"Must have done from where we found him," Nicholson rejoined. "Besides, if anything had happened they'd have stopped."

Retters himself was saying nothing, but his eyes were busy. On the whole he agreed with the sergeant's reading of the situation; but one could not be quite sure that only one horse had jumped. Once across the stream, however, he felt more confident. Only one horse seemed to have landed, slipping a little in the mud but otherwise apparently in safety. There was certainly no sign of a fall. Beyond the stream the prints of the hoofs plunged straight into the trees, swerving to rejoin the path a little farther on.

"Can't see how they could see him, unless they were right on his heels," Ker suggested. "The trees are thick enough to cover him right away."

Retters nodded agreement. The undergrowth was thick, and there were still enough leaves to hide even a horse and rider almost instantly. But unfortunately, many leaves had fallen. The traces of the horse were still barely visible, but only as indistinct marks in the brown carpet which covered the pathway, and farther on, as the ground hardened, even these vanished.

"Much farther?" he demanded.

"About fifty yards beyond the lane here—where it narrows again. Just round the bend."

They had reached a point where a wide, unmetalled track joined the pathway on the left, turning with it for twenty yards or so before continuing on the other side towards the village. In his eagerness, Retters only glanced casually along it; but in his present mood he was missing nothing. He stopped abruptly, staring down at a muddy patch of earth which some chance current of wind had swept clear of the leaves.

"What's up?" Ker demanded. "H'm. Another horse, eh?"

"Yes. Turned into the path from the lane here... Couldn't be Marney's. And the shoes are different. I wonder—?"

Unfortunately he was compelled to go on wondering. The brown carpet recommenced; here and there a few vague marks showed the passage of the riders, but that was all. He halted again when they reached the point where the track turned off to the right and studied the ground anxiously. He was disappointed. At least without proceeding along it, there was no way of telling whether the second rider had turned off or not.

"Queer, eh?" Nicholson voiced his own suspicions. "Now, if you were stabbing a man on horseback, you'd need to be on horseback yourself, wouldn't you? How'd you reach—especially if he wouldn't stop? And I don't reckon anything would stop Mr. Richard."

Retters frowned. In his mind there was more than a suspicion to whom the tracks might belong; but he was certainly not going to show his hand at that stage.

"Might have been one of the members of the hunt?" he suggested. "That track turns off just the other side of the bridge."

"Might have been. Though I'd swear they'd cut across to catch up. Who'd go out of his way like that with hounds right ahead?"

Retters made no answer. Secretly he agreed. There was a growing belief in his mind that perhaps the mystery might be solved a good deal more easily than he had thought; but the fact failed to cheer him half so much as he would have supposed. He kept his eyes fixed on the ground as they advanced again, hoping for a definite glimpse of a double or single track which might settle things one way or the other, but he was unlucky. The path had narrowed, leaving barely room for a single horse to pass; but even apart from the denseness of the copse the low moss-grown banks on either side showed that no one could have left it. They were nearing the bend beyond which Nicholson had said the body was lying when his patience had its reward, though in an unexpected form. A gleam of something bright caught his eye, and he stooped eagerly.

"Hullo! Got something?"

Ker and the farmer peered over his shoulder. It was the silver top of a metal flask, bright and untarnished in spite of the dampness of the ground on which it had rested. Obviously it had not been there long. Holding it carefully by one edge in case of finger-prints, he examined it. It was silver and of expensive make, but without any special marks which might lead to its identification. So far as he could tell without testing it, there were no prints from the fingers of whoever had unscrewed it. Then he sniffed and raised it to his nose. The odour of brandy was distinctly discernible. Without comment he wrapped it carefully in his handkerchief and stowed it in his pocket, marking with a twig the place where it had been lying.

"Marney's, d'you think?" Ker's curiosity was not to be restrained. "How did it come off? It couldn't jerk unfastened. And he wouldn't drink brandy on horseback like that."

Retters preserved a massive silence, but Nicholson hazarded a suggestion.

"After he was wounded?" he suggested. "But there's no blood."

"More likely the murderer's. If he were doing a job like that he might need some Dutch courage... Maybe he'll have the flask?"

It was exactly what Retters himself was wondering about. With the discovery of the flask top, he felt he had secured a tangible piece of evidence, and his qualms subsided. After all, he reflected as they started forward again, personal considerations had no place in police work. His immediate task was to find the murderer, or as much evidence as he could, regardless of whom it might affect.

"There he is!"

Ker's voice broke in on his thoughts. They had rounded the bend, and just ahead under a rather larger tree a patch of scarlet showed vividly against the brown. At the first glance it was obvious that his precaution in keeping back the villagers had failed. There were other routes to the place, and the mysterious bush-telegraph which spreads news over an entire countryside without obvious agency had already collected a group of some half-dozen people. They were standing talking at a respectful distance from the body, and as Retters's eyes took in the members of it he was conscious of a certain surprise. The presence of the three labourers and the gamekeeper was natural enough. They could easily have heard at the farm, or have been passing. But as he hurried forward he found himself wondering exactly what had brought Dr. Ashby, the retired professor who lived at the other end of the village. And the sight of the sixth figure filled him with a mixture of emotions, not the least of which was chagrin. He had reconciled himself to having his thunder stolen soon enough; now it seemed as though it had already vanished. For the woman who stood a little apart from the rest was the popular detective novelist, Mrs. Constance Handley. Obviously she had taken charge, and judging by the way she turned towards them as they came up it appeared as though she was quite prepared to take charge of them as well.

"I'm glad you've come, Retters." Her face was a little paler than usual, but its expression of refined calm had not changed. "I came to see what I could do. I kept them back from—from it as much as I could, but I'm afraid a good many people must have trodden here."

The policeman noted the slight tremor in her voice with a grim amusement. It seemed as though the authoress found a difference between reality and fiction; for in her novels her treatment of corpses was technically cold-blooded and exhaustive. Looking down at the ground near the body he was forced to agree with her. Apparently every separate person who had arrived on the scene had felt bound to satisfy himself that life was extinct, and the tracks, though poorly marked, were only too numerous. He sighed mentally.

"Thank you, ma'am... Which way did you come here?"

She gave him a quick glance. There had been no suspicion in his mind as he asked the question; but evidently she suspected some hidden intention.

"I set off this morning to follow the hunt in my car," she said precisely. "I pulled up to ask a labourer if he'd seen it. He told me what had happened. I left the car on the road and came along Thievesdale to see if I could be of any assistance. Mr. Richard Marney was already dead. This man"—she indicated one of the labourers—"This man and the gamekeeper were already here... If I can help? Perhaps fetch a doctor, or telephone?"

"I have already done so, ma'am." He spoke a little stiffly, a little annoyed at having so obvious a part of his duty pointed out to him. "The inspector and surgeon will be along directly. Excuse me, ma'am."

Feeling for his notebook he moved over to the body. Certainly Richard Marney was dead. He was lying face downwards, with head and shoulders a little raised by the bank on which he had fallen, only his feet sprawling across the path. Beside his hand lay a hunting-crop, and a couple of yards away the hat which had rolled from his head, leaving the curly brown hair bare. For a moment he could not see the wound. Then a gleam of silver under the left armpit caught his eye, and the soaked patch of darker red upon the hunting pink.

It was the dagger which first focused his attention. Even from the hilt and the inch or two of steel exposed it was plain it was no ordinary knife. The thin, sharp blade was made for nothing but stabbing. Nicholson had been right in calling it a dagger, and certainly it was. No weapon one would have expected anyone to be carrying in an English countryside. With poor success he tried to remember his anatomy. In all probability, he thought, it had missed the heart, but had severed an artery. There was a good deal of blood. Suddenly a startling thought flashed across his mind. He raised his head with an involuntary exclamation.

"Good Lord! G—!"

Constance Handley eyed him curiously. Obviously it must be something very extraordinary which had dragged the words from the stolid constable. The next moment his face had again assumed the official blankness which he liked to affect. His face was a little red, but that might be because he was bending over the body feeling carefully for the flask of which the top reposed in his pocket. He did not find it.

"What is it, Retters?" Curiosity evidently overcame the novelist. "It is murder, isn't it?"

"That's for the doctor to say, ma'am. He'll be here soon with the inspector—"

"They're coming now." Ker pointed to the group of men hurrying along the path, and Retters's heart sank. "Now, we'll see."

What Retters saw in the next ten minutes was not precisely pleasant. Like his subordinate, Chief Inspector Boreman was in the position of being clothed in a little authority which was all too brief. In the absence of Superintendent Leyland on holiday, he was acting head of the entire county force, vice a Chief Constable who was only too pleased to delegate his responsibilities as far as possible. He had seen Retters fumbling over the body, and that in itself would have annoyed him. The constable's account of his previous activities reduced him to a profound state of irritation, Retters should have paved the way for him, leaving his superior to make the discoveries of the flask-top and tracks. He listened very grimly to Retters's report, once or twice cutting him short, and openly sneering at his mention of the anonymous letter, and accepted the flask-top without comment. Over the group of onlookers he swept an eagle eye.

"Who're these?" he demanded. "What do they know about it?"

The constable flushed. "Well, sir, I've only just arrived—" he began, and thereby gave Boreman his opening.

"Exactly. You've been wasting time doing everyone's job but your own. I told you to come straight here... Wait there. I'll have a word or two to say to you afterwards."

Obediently, but with a feeling of injustice, Retters retired to the spot indicated. Unfortunately, it was almost out of earshot of the inspector, who, while the doctor was making his examination, apparently intended to re-examine even the witnesses Retters himself had interrogated. He watched the process gloomily. There, at least he felt confident, the Chief Inspector could elicit no more than he had himself discovered. It had been a labourer called Rowles who had found the body, going along the path to repair a fence. At first he had thought it an accident but, going nearer, had seen the dagger. He had touched the body. It was dead, but still warm. The time would be about half-past ten. He had gone back to the farm and told Nicholson, who had gone back with him, accompanied by a dealer with whom he had been talking at the time. Rowles had stayed with the body while the others went for the police. None of them had seen any suspicious stranger in the vicinity.

As for those they had found by the body, it was hard to see what they could know about it. But rather to his surprise, Boreman seemed to be talking at some length to one of the labourers, a little rat-faced man named Withers. And, like the constable, he was obviously puzzled by the presence of Ashby and Mrs. Handley. Towards the professor his manner was a polite kind of bullying which at least once seemed to sting the victim to a weak anger; but though he left Mrs. Handley until last with a rudeness which was probably deliberate, one glance at her was enough to show him that bullying was not likely to succeed. Instead, he dismissed her very shortly and turned to the doctor who had just finished his preliminary examination.

"Well, Doctor?" he asked briskly. "What can you tell us?"

Dr. Hendyng frowned. Boreman's manner irritated him, and, knowing the Marney family intimately, the tragedy had come as a shock from which he had scarcely recovered.

"It's a bad business, Inspector," he said soberly. "He's been dead perhaps an hour and a half or two hours. Perhaps more—"

"Two hours, eh? That would be about right—"

"I should say that the wound made by the dagger was the cause of death. The blade appears to have missed the heart but pierced the artery. He would bleed to death. His clothes are full of blood."

"Murder, eh?" Boreman said, almost with relish. "No doubt of that?"

"I don't think the wound could have been self-inflicted—unless he fell on the dagger somehow." Hendyng eyed him with distaste. "The direction of the blade is downward. There do not appear to be any bruises or other signs of a struggle. But, of course, I cannot say until I have examined the body properly."

Boreman nodded his satisfaction. "That's what I thought," he said. "Don't think there'll be much trouble about this, Doctor... We can move the body?"

"As soon as possible. I've finished for the present."

There was an alert cheerfulness about the inspector's manner as he turned to the sergeant.

"Leave a man here, Smithson. There's a stretcher coming.... Better clear all these people off. And watch out for reporters... See the ground isn't disturbed. You never know—"

He was turning to Retters when a thought seemed to strike him.

"Where's his horse?" he demanded of the world in general. "Anyone seen it?"

There was a brief silence which signified a negative.

"It would follow the hounds on its own, Inspector," Mrs. Handley suggested. "I expect some of the other members have caught it by now."

"Maybe, madam," Boreman assented curtly, and turned to the constable. "Now, Retters. These tracks—"

Accompanied by the two plain-clothes men, they set off down the path in silence. Mentally, Retters was criticizing his superior's procedure. The body should certainly have been photographed before it was moved. What could he have got from Withers? And why had Ashby been angry. And of course the letter was important. It must be. No mere coincidence could account for its arrival on that particular morning. Even in the spot where the flask-top had been found Boreman displayed only a casual interest; but his eyes brightened as he saw the tracks.

"Ah, these are plain enough... Shouldn't have much trouble in identifying those. A few inquiries among local hunters, eh, Johnstone?"

The plain-clothes man was actually less optimistic. He was picturing someone, probably himself, going round collecting some dozens of horse-shoe prints. Even with the knowledge of their owners it would be no picnic.

"There'll be a good many horses round about, sir," he ventured.

Boreman laughed. "But if I can tell you the right stable?" he suggested. "How then?"

Incautiously, Retters felt bound to make a suggestion. "But he might never have gone so far along the path, sir," he suggested. "He might have turned off down the other lane—leading to the village, sir—"

Boreman glared at him. Exactly what withering reproof he would have delivered remained unspoken. There was the thud of horse's hoofs, and the next minute a rider appeared round the bend. He was going recklessly and almost ran right into the group of detectives before he could pull up.

"What the devil—?" Boreman snapped as the horse plunged on the very edge of the muddy patch containing the vital tracks. "Keep off there! Mind, sir?... Who're you?"

Egmont did not trouble to answer the question. He was very pale, and his eyes were fixed with a peculiar intensity on the inspector.

"It's true then?" he said, "Marney's been murdered?"

Boreman eyed him. Perhaps memory came to his aid, for he did not trouble to repeat the question.

"It's true enough, sir," he said slowly. "You've something to tell us about it?"

"I? Nothing. Wasn't even at the hunt. Haven't seen him to-day—" Egmont spoke with a nervous hurriedness. "Good God, Inspector—"

"I'd like a word with you just the same, sir... Johnstone will hold your horse... You ought to be more careful, sir. You might have—"

As he administered the reproof, his eyes sought the precious tracks. Then his jaw dropped momentarily. He stared for a moment at the muddy patch and there was a new light in his eye as he turned to the young man who had just dismounted.

"It's Mr. Egmont, isn't it?" he asked. "Yes. If you'd just step over here, sir—"

He led the way carefully away from the patch of mud to the other side of the path. None of the three men watching needed to ask why. Egmont's horse had stepped on the edge of the soft ground, and even at a glance it was obvious that the tracks corresponded.

JOAN MARNEY had only the dimmest idea of precisely what had happened from the time she recovered consciousness in the cottage to which she had been taken. Her one thought had been to get home. Egmont had been waiting as she stepped outside in a sort of dreadful dream. She had not heard what he said. But there was no need for her to reply. Evidently the way she had recoiled from him was enough, and the one thing she remembered clearly was the look on his face as she rode away.

One horrible idea dominated her. Really, it was she herself who had killed Dick. She had been perfectly aware of the rivalry between the two men. Whether she had loved either or both of them she did not know to that moment. She had enjoyed their company; she had derived a mischievous amusement from their jealousy of each other, without intending any conscious cruelty, and hardly aware of the depth of the passions she might be arousing. And now— Her cousin's death seemed utterly incredible; and it was still more incredible that Hugh Egmont should be his murderer. And yet in her mind there was a doubt. Unwillingly, she was building up against a case rather better than that which was giving Inspector Boreman a good deal of satisfaction almost at the same moment.

Everyone knew the violence of Egmont's temper. Once before they had nearly come to blows. And that morning Hugh had been particularly exasperated. He had believed that it had been her cousin who had sent the false message about the cancellation of the meet. She knew him too well not to know what effect this last offence was likely to have on him. It could so easily have been the last straw, if he had met Marney that morning; and he could have done. Like Hugh and her cousin, she had hunted all over the country and knew it like the palm of her hand. Hugh had told her that he first knew that the message was false by seeing the hunt set off. On his road to the village be could at several points have seen the line which it followed; he could have guessed it was heading for the Cliff, and he must have known that only her cousin could take the jump. He could have cut across, gained the other side, and waited...

And there was the dagger. But that thought she put violently away from her. That was the one thing she must not think about. It was only too likely the police would question her, and she shuddered at the thought of the ordeal. But for the most part she could tell them nothing which was not common knowledge. She could even make Egmont's position better by minimizing the degree of feeling which existed. But they must not find out about the dagger, nor even from the expression on her face guess for a moment that she knew.

In the very doorway of the house she hesitated. Her coming home had been merely instinctive; for she had little hope of finding either help or comfort there. The death of her mother years before had left her existence in her own home curiously lonely. It had once been said of Charles Marney that he had inherited the brains of the family; but the loss of his wife had interrupted what might have been a brilliant career. He had been content to go to seed in the Dower House which was the allotted portion of stray members of the family, mildly interested in antiquarian matters, fascinated by the hope of finding an infallible betting system, annually growing more and more hopelessly insolvent. Towards his daughter he preserved a remote kindliness; towards the world in general an unshakable politeness. But for the rather irritated and contemptuous help given by his brother he would long since have been bankrupt, and it was hard to imagine any crisis to which he would rise successfully. And of the whole family he had been friendly only with his dead nephew, whose cause he had supported against Egmont to that slight degree in which he permitted himself to intervene. And yet she must talk to someone. She pushed the door open and walked in.

There seemed something strange in the very peacefulness of the dark hall. Everything was exactly the same as it had been when she left only a few hours ago; and yet in that time her whole world had changed. Surely they must have heard? The appearance of a servant from the direction of the kitchen provided an answer to the question. In the girl's plain, rather stupid face there was no hint of agitation. She steeled herself to a false calmness.

"My father's in the study, Jane?" The question was an unnecessary one. At that hour Charles Marney was always in the study, multiplying, dividing, adding and subtracting on his system with an assiduity worthy of a better cause. But the maid's answer was surprising.

"Oh yes, miss. He came back half an hour ago... He's there with Sir John, miss."

For a moment Joan stared at her. That her father should have gone out at all during the morning was sufficiently extraordinary to provoke surprise; and then the second part of the news came home to her. Her uncle was there. And from the mere fact of his presence he could know nothing of what had happened. Instead of pouring out her troubles to her father, she was faced with the ordeal of breaking the news of Dick's death to Sir John.

For a full minute she stood there, trying to summon her resolution. Suddenly she was conscious of the maid's eyes upon her.

"Thank you, Jane," she said in what she hoped was a natural voice. "That—that was all I wanted."

But the girl did not immediately accept her dismissal. She eyed her mistress anxiously.

"You're all right, miss?" she asked. "You look sort of white—"

"Quite—thank you, Jane."

Aware that the girl's eyes were still upon her she crossed the hall steadily and turned into the corridor leading to the study. The Dower House was an architectural puzzle. Since it was first built, it had grown and shrunk at irregular intervals, now expanding according to the needs of the occupants, now being allowed to fall into ruin. In its small maze of doors and passages, the room which her father had chosen for his study lay at the extreme far corner from the entrance. She moved slowly up the passage, wondering what she was going to do; but she reached the end before she found an answer.

The study itself was queerly shaped, a long projection from the middle of its main rectangle giving it the shape of a squat letter T, and it was into this that the door gave entrance. Hesitating for a moment on the threshold, she turned the handle and entered.

At the first glance there seemed to be no one there. Her father's desk, under the big window directly in front, was empty. She advanced a pace or two into the room; then the murmur of voices reached her. It came from the right-hand branch of the T, where she knew was situated the safe containing nothing more valuable than the records of her father's losses; but in his eyes the key to immense potential wealth, given a little more capital.

At the sound she stopped. It was not that one of the voices was loud and angry. That she could almost have expected; for a visit from Sir John to his brother had come to mean almost invariably that he was called to Charles Marney's financial rescue; and during such interviews her father was politely deprecating, while her uncle blustered. But now that the prospect of facing her uncle with the news was so imminent, her nerve failed her. For a minute she stood there, hidden from their sight by the projecting wall, and trying to summon her courage.

"Damn it, Charles, it's too much. I've done all I mean to!" Her uncle's voice was raised angrily. "It's getting worse! There's that Grilney bill. And now this. There's a limit to anything. If it weren't for the family—"

"Grilney's paid." Her father's cultured voice just reached her. "You don't understand, John, I made a slight mistake—just an error of calculation—"

His brother interrupted him. "Grilney paid?" he demanded. "Where did the money come from?"

There was a perceptible pause. "He is paid," her father said hesitantly. "I got the money—"

"Lenders?"

"No."

"Then I'll know where before I stir a hand in this." The older man's voice was grim. "You'd none coming in. And I'm damned if you won it on your system."

The contempt in the last words, or perhaps the slight upon the one thing really dear to his heart, stung Charles Marney to a protest.

"Really, John, this tone is hardly necessary. I haven't asked your help—this time."

"No. And I'll not give it, except on the condition, you know... You can smash for all I care. The Marneys were never gamblers, thank God. And as for letting Dick marry blood of yours—"

"John!"

For the first time Charles Marney's gentle voice was raised sharply, but his brother did not heed.

"Let her leave my boy alone, and marry that young fool Egmont. He'd be a good match—"

Abruptly it was forced upon Joan that she was eavesdropping. A flush came on her cheek. A momentary anger nerved her to step forward into the front part of the room.

Both men turned at the sound of her footsteps on the parquet floor. They were standing near the open safe at the far end, and even at that moment she was struck by the contrast between them. The baronet's more coarsely featured face was red with anger and he was breathing heavily. One hand was still clenched in an emphatic gesture. On the pale, refined face of his younger brother there was a look of unwonted resolve, but he stood as easily as though nothing had happened. The two stood staring at her for a moment; then it was her father who spoke,

"Joan, dear, you're early." His voice was perfectly calm. "There's nothing wrong?"

Before she could answer, his brother burst in.

"She's been listening, damn it! And I hope she heard. There's been enough fooling about. One of these days there'll be the devil to pay if—"

He broke off. Angry as he was, the expression on her face seemed to strike home. She struggled to speak, but no words came. The sight of Dick's father alone might have robbed her of words. Under the circumstances she could only stare mutely at her father. Her hand went to her throat. Charles Marney stepped quickly forward.

"Joan, you're ill?... There's something wrong?"

She nodded dumbly. Then a single word escaped her lips.

"Dick—"

A sob choked her utterance. But the name alone had been enough for her uncle. Suddenly he had paled. He took a hesitating step forward, and his voice shook as he spoke.

"Dick? There's nothing wrong with Dick? He's all right?... Joan! He's all right?... He's hurt?"

She could only shake her head. There was a moment's silence. John Marney stared at her with a look of pathetic appeal, and his lips trembled.

"You mean—you mean—my boy Dick—?"

There was no need for her to speak. He swayed slightly where he stood. Gently his brother took his arm and led him to a chair. He sank into it unresistingly and raised a hand to his eyes. With a quick glance at him Charles stepped across to a side table on which stood a bottle and siphon. His own face as he lifted the bottle was strangely impassive. In the silence they could hear the trickle of the liquid as he poured it, punctuated by the baronet's quick breathing.

"The Cliff. It would be the Cliff." John spoke suddenly a curiously gentle voice. "They headed that way. Saw 'em start, and half guessed that he'd try it. He never wanted for pluck... Jack first. And now Dick—"

His voice trailed away. Charles moved over to his side and extended the tumbler. His brother made no move to take it, staring straight before him with eyes which saw nothing.

"John. Drink this." Charles spoke for the first time since the truth had dawned upon them. You mustn't give way. There's Mary to think of. And Maurice."

His brother looked at him dully for a moment.

"Maurice," he said at last, "Maurice is a good lad. He's always done the right thing by me and the estate. It'll be in good hands. But Dick—Dick—" With an effort he overcame the working of his face. "Yes. You're right. Mustn't give way... Give me that."

He swallowed the neat spirit at a gulp. "Died like his grandfather... Did he speak? He didn't suffer?"

His eyes sought Joan's. With a rush speech came to her as her self-control gave way.

"You—you don't understand... It wasn't that. He didn't fall. He'd jumped the Cliff—was all right... He was murdered!"

"Murdered?"

John Marney half rose to his feet as he spoke. Charles put a hand gently on his arm, but he shook it off.

"Murdered?" he repeated. "You say murdered?"

"He—he was stabbed—the other side of the stream—"

"Then—then it was—! And, by God, you come here to tell me! After what you've done—"

His hand shot up as though he was going to strike her. He took a single pace forward. Then even as his brother gripped his shoulder to restrain him he seemed to collapse. The upraised arm fell to his side, and he stood swaying slightly. The next moment he subsided in a limp heap to the ground.

"Joan!" Her father's voice roused her to action. "A doctor... Quickly. Send a servant—cold water and cloths. Hurry!"

He was already on his knees beside the unconscious baronet, loosening his collar and tie and raising the head. John Marney's face was purple and he was breathing stertorously. Joan stared in fascinated horror.

"Quick, Joan... It's a stroke—"

The words seemed to break the spell which had held her motionless. She had turned in an instant, running for the door. The long passage seemed endless, and she felt as though an hour had passed before she reached the hall. With a sigh of relief she saw the solitary manservant dignified by the name of butler just emerging from the dining room, and in a few hurried words told him what was needed. She was barely coherent, but Wilson had grown old in service and no emergency appalled him.

"A cold compress, miss. Yes. I'll go at once... Don't you worry, Miss Joan... The doctor—?"

"I'll telephone. Go—go at once—"

But telephoning proved more difficult than she had thought. In the whirl of her thoughts she could not remember Hendyng's number, and had to search the directory, only to be informed on getting through at last that the doctor was out. The servant to whom she was speaking could make nothing of her message, and she had to repeat it three times. Nearly ten minutes must have elapsed before she retraced her steps to the study. Outside the doorway she stopped, with a dreadful foreboding in her heart. All at once the door opened. Her father stepped out and, as he saw her, raised a finger to his lips. Then he saw the question in her eyes and spoke, closing the door behind him as he did so.

"Still unconscious... But I think—I think he will be all right. He's strong—" He broke off. A slight frown puckered his brows. "Joan, I wanted to speak to you, before—before—" He hesitated for a moment, and left the sentence unfinished. "Now, my dear, will you try and tell me what happened?"

After all, it was little enough that she could tell him. She only knew the little which she had heard from Nicholson, and a few odd remarks half-consciously absorbed in the cottage. He listened in silence, without a sign of emotion on his face. For some reason, his very impassivity frightened her; for he had been fond of Dick. As she finished he inclined his head slowly.

"Yes," he said and paused. "Of course, the police would be called in. Of course. They'll search—"

She could only stare at him in bewilderment as he broke off. The words were so different from what she had expected.

"They've not seen you yet? No. But, especially if they think Egmont is guilty, they will. Naturally. To try to get out of you just how—"

He broke off again. A queer sense of horror was growing in her mind. It seemed to her as though the shock must have affected her father's brain. He stood for a moment looking at her, and all at once his gaze seemed to have become curiously intent.

"Joan, you were there? While your uncle and I were talking. You heard—you heard something?"

She nodded dumbly.

"About the money? What John was saying—about my paying the Grilney loan? You did. Yes."

"I—I couldn't help it. I didn't mean to listen, Daddy... But I couldn't bring myself to—to tell—"

She broke off, burying her face in her hands as though to shut out the scene which she had just witnessed. Charles Marney's arm went about her sympathetically.

"Of course not, Joan dear. I quite understand... But I just wondered. You know that I've had some troubles about money. I have not the least objection to your hearing. Only—"

Again he broke off and seemed to be at a loss for words. She looked up into his face. In it she could see nothing but kindness, and yet her uneasiness persisted. There was something wrong. She stood waiting. He drew a deep breath, and seemed to nerve himself to something.

"Only—when the police come, perhaps dear, you'd better not tell them—about the money."

"But—but that's nothing to do with—with what has happened? Why should I? It—it hasn't, Daddy?"

"Of course not, dear. Only—I thought I'd better warn you. I don't mean about the debts. They'll find that out. But about paying the Grilney loan."

THERE was the trace of a smile on Superintendent Leyland's lips as he leaned back in the chair and looked at the man in the chair opposite. The smile was at the thought of the Chief Constable's reception of the representative Scotland Yard had seen fit to send them. Then the smile faded. He drew deeply at his pipe and glanced at the detective inquiringly.

"Well," he said. "You've got the dope, so far as we know it. What d'you think?"

Inspector Lyly hesitated. "I think," he said slowly, "that the chief inspector is a little precipitate in wanting to arrest Egmont. That constable seems a good man thrown away. You ought to import him into your local C. I.D."

"Retters? Yes. I thought of that myself... As for Boreman, it wasn't so much the murder that brought me back from holiday as that the chief said Boreman had solved it. It's discretion that he lacks. Now, a policeman may be as clever as you like, but unless he wants trouble he's got to be careful too... What do you make of the case?"

Lyly smiled, and his eyebrows rose. "There isn't one," he said. "There's the bare bones of what might be one. That's all."

"Why?"

"Too many loopholes for any judge and jury... There was a motive, certainly. The two men were jealous, and that morning Egmont felt particularly aggrieved because he thought Marney had hoaxed him. You may say he might have wanted to kill Marney. But did he?... Well, there was opportunity of a kind. Egmont was on or near the spot somewhere about the time the crime was committed. And he seems to have been the only person about on horseback who was. Bearing in mind the nature of the wound that is important. But, really, that's all."

"Boreman thinks it's enough."

"I don't agree. There's the dagger. Up to date we've failed completely to show that Egmont possessed, or had access to, any such weapon. Still less have we shown he was carrying it. You see, according to his account, he only knew that the hunt was on when he saw it meet. But he didn't know where it was going. Are we to suppose that he normally carried that dagger? Or that that particular morning he put it in his pocket just in case he met Marney?"

"That's possible, isn't it?"

"Theoretically, perhaps it is. But, however angry he might be, I don't see Egmont going about the job that way—at least from the character he's given. Then, there's his behaviour after he's supposed to have committed the murder. He doesn't follow the hunt or go back home. Either would have been more sensible than going into the village and chatting to the policeman. And neither Ker nor Retters thought he looked like a man who'd just committed a murder. Finally, there's the letter."

"Ah." The superintendent looked up with a sudden interest. "I wonder what you make of that?"

"Precious little... But I don't think we can dismiss it as the chief inspector does as a silly hoax without bearing on the crime."

"Boreman's a perfect ass when he gets a bee in his bonnet," Leyland commented without malice. "He'd ignore anything."

"But even he could scarcely ignore the coincidences between what the writer foretold and what happened. There's that allusion to the hunt. And death certainly ended Marney's run pretty near 'where the stream flows.' The 'gules on gules' might be the blood on his red coat. The argent might be the silver hilted dagger—though I don't get the azure exactly."

"Might mean Marney was a blue-blooded aristocrat." Leyland grinned at his joke but sobered quickly. "Aren't you overlooking something? Retters had the idea that the letter did mean something to Egmont."

"He may have been right. I'm just coming to that. Well, the letter-writer seems to have known that someone was going to be killed while dressed for hunting near the stream. And he also knew that that person was Marney. That's what bothered Egmont. He saw the reference."

Leyland opened his eyes a little wider and stared. "It's more than I do," he admitted. "That sitting lion stuff, you mean?"

"You showed it me yourself. That letter from Maurice Marney! What's the crest?"

Leyland turned over the papers. "Why, good Lord! It's a lion," he exclaimed. "You mean—?"

"It's more than a lion. In the ghastly jargon of heraldry, it's a lion sejant guardant—sitting and looking. If old Marney's regarded as the lion, Dick was the cub—or one of them. It's pretty clear the writer knew just what was going to happen."

"Good Lord!" Leyland drew the sheet towards him from where it lay on the desk at his side and studied it for a moment or two in silence. Then he nodded. "Yes," he said unwillingly. "It fits all right... But he slipped up once... The hunt did kill—a young fox, out by Barden village."

"We'll allow him a margin of error on the hunt form. But the rest's all right. Now, when was that letter posted?"

Leyland glanced at the envelope. "Half-past seven the night before," he said slowly. "But then—"

"But then, no one could possibly know that the hunt would head for the Cliff at all. It all depended on the fox. And if the hunt went anywhere else, the murderer couldn't count on Marney being separated from the rest."

"I don't get you."

"It was just because the hunt went to the Cliff, and Marney was the only man who would dare take that jump that the murderer had his opportunity. But who would know it would?"

Leyland thought for a long time, frowning down at the letter as though seeking inspiration from it.

"No one," he said at last. "No one could tell which way the fox would head. No one but a blasted prophet."

"That's what is peculiarly interesting about the letter. Was it written before the murder, by a murderer with second sight? Or was it written after—and faked?"

"Faked? How could it have been?"

"I don't know, yet. But it's a thing to look into... Now, Egmont might have noticed the sitting lion stuff, and the reference to young Marney, and as he was cordially engaged in hating him at that moment it might take him aback a little. But had he any opportunity of getting that letter delivered to Retters?"

Leyland considered. "I don't see that he could," he said. "He hadn't been in the village before that morning. Someone would certainly have seen him. That village sees everything."

"Yes. And that's in his favour—if the letter was faked. But there is an objection even to that. That's why I wanted a word with the Master—"

"The Hon. Toby?" Leyland grinned. "He'll he here soon. Most upset, I gather. Thinks it's a reflection on the hunt. Stabbing people doesn't happen in the best huntin' circles—particularly when there's a fox about. It's positively irreverent!"

Lyly smiled politely. "Well, what do we know about the letter?" he continued. "Paper and so on... You've looked into that?"

"Retters did. Whatever Boreman thought, he was sure the letter had something to do with it. They're both common—paper and envelope. So's the ink. You can't tell a thing from the printed character. But"—he paused significantly—"but Retters did find out that you can buy that kind of stationery at the village post office."

"At the post office... Yes." Lyly's brow wrinkled. "Well, until you can prove either that Egmont had the dagger, or that he could have written the letter, your case is a bit thin. It's quite possible you will prove it. A dagger like that is uncommon enough. You might find where he bought it—"

"We're trying to... But it's foreign work. The odds are it was a souvenir brought from abroad or something like that."

"Very likely... Egmont may very well be guilty. But he's not likely to bolt. If he does he gives the game away. And in the meantime it's our business to make dead sure before we do anything. Even to the point of considering other possible suspects."

Leyland shook his head. "There aren't any," he said with regret. "Barring Egmont, Marney doesn't seem to have had an enemy in the world."

"So far as we know... But it needn't be an enemy who kills you. I mean, the murderer may be inspired by other motives than hate... Isn't there something there about that Professor chap—Ashby?"

"Ashby? Yes." The superintendent turned over the pages of his notes. "But he's no good. It was just that Boreman happened to be a bit fed up at finding so many of them about when he got there and put 'em all through it—more to make himself objectionable than anything else. He didn't like the way Ashby answered. But that's all. Even he didn't suspect him."

"All the same, if you'd just go through it again?"

Leyland grunted. "He just happened to be there... No, no one had told him about the murder. He came round the corner and saw the body there. He was very shocked. No, he did not know Marney well. He had not been going anywhere in particular—just for a walk. No, he was not in the habit of walking. He suffered from corns. No—very emphatically, this. He seemed quite peeved at the idea—he had not been following the hunt. Abominable cruelty—shouldn't be permitted in a civilized country. Served Marney right if he got himself killed while hunting... That's about the sum of it. An old crank, that's all."

"And, apparently, an enthusiast of sorts... Pretty lame, isn't it?"

"That's nothing. If you'd ever seen Boreman dealing with a witness he didn't like, you wouldn't wonder if a donnish old bird of Ashby's sort got a bit rattled."

"Still, he's unexplained. We'll bear him in mind, anyhow. The others were all right? Those who were on the scene? So far as we can tell. Mrs. Handley—well, it was natural enough for her to pop along. Ever read any of her stuff?"

"Pretty gory. Oh, there was Withers. He was the man who put Boreman on to Egmont. Told him about the feud between him and Marney. I don't know what you make of that?"

"Nothing, perhaps. Or it might show a grudge against Egmont—though that's hardly a reason for murder... And no one suspicious seen about the place?"

"Strangers? You're thinking of the dagger... Well, almost certainly it's Italian. But young Marney had never been to Italy, and had no connexion with the place so far as we know." He laughed. "That's what Retters might think—that it was the Camorra, or Mafia or something. He had an idea almost as good."

Lyly looked his enquiry.

"About the dagger." Leyland grinned. "Got it from a Doctor Thorndyke story, I believe. He's a great reader. You see, one difficulty is that Marney wasn't likely to dismount under the circumstances, and unless anyone was on horseback or about the same level it's hard to see how the wound could have been inflicted in that position. But there are only the tracks of Egmont's horse, and he doesn't believe Egmont did it. He suggests that the dagger was shot."

"From a gun?" Lyly eyed the weapon where it lay on the desk. He remembered the story well enough. But there the dagger had had a hilt without a guard, capable of fitting into the bore of the chassepot from which it had been fired. Here there could be no question of that. A cross-piece where the hilt joined the blade made it impossible." He shook his head. "No gun would take it."

"Retters suggested a cross-bow! I suppose it might be done, but—!"

Lyly frowned at the weapon thoughtfully; then reached over and picked it up, weighing it carefully in his hand.

"It might," he said. "But there's another thing. It might have been thrown."

"Thrown? To go in like that?"

"You'd be surprised how hard an expert can throw. Though I'd hardly expect an expert here. Or the murderer might have been up a tree when he stabbed. I don't think we're entitled to assume he was riding. But we're getting too theoretical. The question is, what is the next thing to do?"

"Well," Leyland said with a certain amount of complacency. "We're trying to find out about the dagger. We're trying to check Egmont's time-table—I mean, to show definitely if he rode that way before or after the hunt passed. We're working on the fake call—or trying to find out if there was one—"

"You mean telling Egmont the meet was cancelled? Yes. That might be important."

"And we can follow up your suggestion of the letter. Then, there's the heraldry stuff. We're trying to make a list of people who would know enough to use it. That rules out the ordinary villager, you see... All that's pretty concrete... You were talking about other motives. See any for Marney?"

"Don't know him well enough... There's revenge?"

"Never hurt anyone in his life that we can hear of."

"Fear? But I suppose no one had any reason to be afraid of him?"

"No sign of it."

"Gain? And that's as common as any."

"But who would gain by his death? He'd no money himself. Old Marney made him an allowance, and would have made him a bigger one when he married. Of course, I suppose there'll be a bit more for Maurice Marney—his elder brother—but there's plenty of cash, and he'll hardly notice it. No, I don't see how that could work."

"About the Marney family. If you could just make it plain which is which—"

"Well, of course, Sir John is the Baronet—head of the house, and possessor of the cash. He had two sons, Maurice, and Dick—Dick being very much younger. About fifteen years. There was a girl between who died as a baby. Maurice married, and had one son. His wife died at the birth. The boy, Jack Marney, was killed a year ago—"

"Killed?"

"Car accident at Oxford... Charles is the baronet's younger brother. Invents betting systems that are going to make his fortune, and is always hard up. But he's a gentleman, anyway."

"Meaning his brother isn't?"

"Well—in a different way. Sir John can be a bit of a boor—or could. The poor old boy can't last long, I'm told."

"Leaving only Maurice, Charles and Joan?"

"There's Lady Marney. But nobody minds about her."

"There's no family trouble?"

"No. Very affectionate, I should say. Periodic blow-ups between John and Charles over finance—but they're used to that. The baronet always stumps up all right. Nothing really wrong."

Lyly sat for a minute in silence. "I'd like to see the Honourable," he said at last. "And then, if you don't mind, I'll just wander about a bit on my own. Get familiar with the ground. They don't know me there yet as a detective. I might hear more."

"Just as you like," Leyland assented and smiled. "No, you don't exactly look—"

A knock on the door interrupted him, and the sergeant entered. Leyland looked across at him.

"He's come?" he asked.

"Yes, sir... He's brought two gentlemen with him, sir. Major Rothersleigh and Mr. Maurice Marney, sir."

Leyland's eyebrows rose a little. "Show 'em all in, Sergeant," he said. "He can bring the whole hunt if he likes—barring the hounds... You'd better bring another chair."

The door closed behind him. Lyly looked at the superintendent curiously.

"Why the deputation?" he asked.

"Moral support, maybe. He's shy. But a decent lad, in his own way. Bit of an ass, perhaps—"

The potted biography was interrupted by the entrance of its subject. So far as it had gone, Lyly judged, it was accurate enough. The Hon. Toby Wilmot had taken on the mastership when his father was finally incapacitated by gout, and it was the one thing which he had taken seriously. It might well have been said of him that "hunting he loved, but love he laughed to scorn," except that he would have done nothing so rude. Up to date, he had merely evaded with embarrassed adroitness the wiles of dowagers who sought him for their daughters, and avoided almost by instinct any close contact with the daughters themselves. Amiability itself, he quarrelled with no one; with unlimited money, his expenditure except on horses was a model of moderation. His great aim was to keep the peace, see to the efficient stopping of earths and removal of wire, and live like his fathers before him. In the district he was universally liked, even by those who, like the superintendent, thought him a much bigger fool than was actually the case.

His two companions were readily identifiable. Rothersleigh could have been nothing but a major, even if a family resemblance had not indicated the dead man's brother. Lyly eyed Maurice Marney curiously. He had seen the corpse, and in features the likeness between the two was unmistakable. But this was a much older man, and one who had seen trouble. Lyly judged him to be in the early forties. His hair was greying slightly at the temples; his expression gave the idea of strength and purposefulness. One could have imagined him a hard man when he was convinced of the justice of his case; he would spare no one else any more than he would himself in what he judged to be his duty.

Wilmot smiled amiably at the superintendent as he effected an introduction.

"Thought you wouldn't mind, Superintendent," he said with a trace of apology. "Major Rothersleigh—you've met Mr. Marney? Of course... Brought them along, you know. Thought they might help. The fact is, the major thought you ought to know—I'm not sure, myself, mind you. But that can wait, if you like... You had a few things you wanted to ask, you said?"

"The inspector here has." Leyland indicated him, and Wilmot's face showed surprise. "Just about the hunting, you know, and so on."

"You see, sir, I don't know the country—not this part," Lyly said. "And there are one or two points that I'd like to be clearer about. Could you tell me exactly what happened that day? In the hunting, I mean."

"Well," the Hon. Toby rubbed his chin gravely. "We found right away, a hot scent. Didn't have a scrap of bother, and weren't at fault once right till we reached the Cliff. Then the fox turned to cross. They often do, you know. I saw Marney, and he was obviously going to have a shot at it. I and two or three others watched him take off and land safely. Dashed clever bit of work. It's a bit beyond my form. The rest of us hurried along for the bridge. The hounds were a good way ahead by the time we saw them, going well, and we'd a job to catch them. So we went along, going strong till we'd nearly reached Barden. Then we had to cast round a bit, but picked up the scent again and got going. We killed about a couple of miles farther on. A dashed good run; at least, I thought so, until I heard this."

"You didn't miss Mr. Richard Marney?"

"Hadn't time you know... Had to keep an eye on the hounds. Right at the end I thought about him and reckoned his horse might have strained itself. But a few minutes later his horse came along. He wasn't on it. I was a bit worried then. But it was too late to go back or anything... Of course, I couldn't guess what had happened. It's not what you'd expect, hunting—"

Lyly suppressed a smile at the last comment. "You did kill, then?"

"Well, yes," Wilmot said dubiously. "We killed a fox. But I'd not swear it was the same one."

The inspector nodded. "And the run took the course you'd expect?" he asked. "I suppose you can tell pretty well which way foxes are likely to head from a given covert? Creatures of habit, like the rest of us?"

"I wouldn't say that. You'd find one would go one way, and one another... Yes. It was pretty well what you might expect. They often go that way... I don't know if I'm telling you the right things?"

He looked anxiously at Lyly, who nodded.

"Oh, quite, sir... The run was normal, then—"

"It was a dashed sight better than usual, that's all. Nothing happened out of the ordinary—that I saw, I mean."

The mere idea seemed to worry him. Lyly looked across at the superintendent; but Leyland, who was thoroughly at sea, had nothing to add in the way of questions about the run. He looked instead at Major Rothersleigh.

"The major had something to tell us?" he suggested.