RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

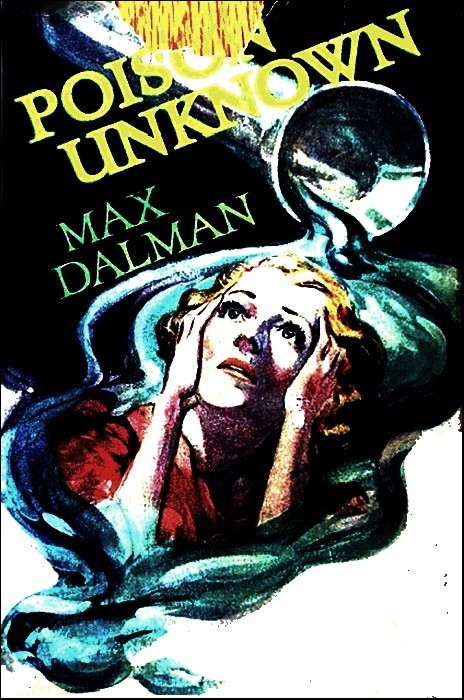

"Poison Unknown"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1939

"Poison Unknown" is a vintage murder mystery set in the scientific world of Great Britain in the 1930's.

Professor Charles Roseland, head of the Juliot Research Centre, a small institute for newly-qualified scientists, is found dead in his laboratory after a weekend trip to London. His death appears natural, but investigators uncover hints of espionage and a secret project involving an experimental poison gas.

Inspector McCleod of Scotland Yard leads the inquiry, but Roseland’s daughter Sylvia and her fiancé Paul Danton also take matters into their own hands when Paul becomes a suspect.

FROM the rack on the bench before him Paul Danton selected a test tube and held it up to the light. If his theories were justified by experiment, the two or three inches of colourless fluid which it contained would be enough to poison every member of the Juliot Research Institute. As he stood there looking at it the thought came to him, and with it the reflection that it might be worse employed. They would die instantly, painlessly, in a way no man had died before, and no man in the world would recognise such symptoms as appeared except himself. He let his mind play with the idea. Eighteen months of forced association with distasteful colleagues had come near to transforming dislike into hatred; and only a little while ago, while on the threshold of what would probably be the great success of his life, he had realised the probability that another would take the credit for the work he had done.

His firm, almost ascetic face was grim as he changed the tube to his left hand and picked up a short glass rod. He dipped it into the liquid and withdrew it. Upon the tip a single transparent drop gleamed in the sunlight streaming through the windows, to all appearance as harmless as water. But, as a careless movement allowed it to drip on to the hand holding the tube, he moved over to the sink. In spite of a contempt for poisons bred by familiarity, he rinsed his hands once, and a second time, before picking up the tube again.

For a few seconds he eyed it in a kind of fascination. Then, with the rod, he gently scratched the inner surface of the glass below the level of the fluid. Abruptly, as if by miracle, a little blur of crystals materialised. All at once the contents changed to a white, encrusted mass. His expression was unaltered; the uplifted hand did not tremble, but he drew a single deep breath.

Tests had still to be made, but he was already sure. The few grammes of crystal represented an alkaloid which, to human knowledge, had never existed in its pure state, if at all: a new and powerful drug, of immense potentialities and dangers. Experiments had still to be made, chemically and on living animals; but half his work was done. He prodded the stuff once or twice tentatively. Then his face darkened.

"The old swine!" he muttered. "Serve him right if—"

He had spoken the last words audibly. All at once, with a guilty start, he turned his head, with the feeling that someone was watching him. The room was empty. Then, through the open door, he fancied he heard something. It was the sound of a furtive movement on the cement floor outside. He waited, but it was not repeated. For half a minute nothing happened. His momentary tenseness had relaxed when at last he heard the tread of footsteps approaching along the corridor. Something familiar in them made him stiffen again. He looked at the tube, gripping it fiercely. The steps were very near. On a sudden impulse he smashed the tube violently into the waste box at his feet. Appalled by his own action, he stared for a moment at the twinkling points of broken glass before he looked up to meet the eyes of the man in the doorway. It was a complete stranger.

In the first shock of surprise, Danton stood there stupidly. His first coherent thought was that it must be a traveller—a traveller of that cultured, learned type which deals with the more complicated scientific requisites. The next instant, without knowing why, he had changed his mind. The man was neatly, accurately dressed in an unobtrusive suit of dark grey. His rather plump, hairless face expressed nothing but a mild benevolence mingled with apology. There was nothing in the least remarkable about his appearance, except the unusually keen blue eyes which were turned on Danton in a look of inquiry.

"Pardon me," he said. "I was looking for Professor Roseland. Could you direct me?"

There was a distinct pause before Danton answered, and he obviously found difficulty in speaking. With a manifest effort he attempted to assume a more amiable expression than that which must have first greeted the stranger. His eyes dropped for a moment to the waste box, and he swallowed uneasily.

"I don't know," he said at last. "I doubt if you can see him. The Professor— Had you an appointment?"

"In a manner of speaking." A disarming smile came with the words. "He was good enough to suggest that I might drop in—"

"Oh." Still Danton hesitated. "He's been away. Probably he's not back yet—"

"He might have spoken of me? My name is Smith—John Smith?"

He waited, as though expecting some comment or a return introduction, but Danton did not gratify him. He stood eyeing the man with uncompromising coldness; but the stranger smiled again.

"I think I have the pleasure of addressing Mr. Danton?"

Danton frowned. "That's my name. But I'm afraid—"

"I saw it on the door. I am sorry to interrupt you—if you are busy?" He stopped, and there might have been a hidden significance in the words, but Danton said nothing. "I had already tried one room in vain—Mr. Hope's, I think? Er—Professor Roseland?"

"The attendant might know." The young man's manner was brusque to the point of rudeness. "Or ask at the house. He may be away still."

He half turned away, but Smith failed to take the hint. Inclining his head slightly in acknowledgement, he advanced a couple of steps into the room, peering at the bottles and apparatus on the bench.

"Research?" he asked. "Fascinating work, isn't it? But exasperating.... One never knows if months have been wasted—and if one succeeds, someone else may get the glory."

Danton started a little, perhaps in surprise at the echo of his own thoughts of a moment before. He faced the man again, with suspicion in his eyes.

"If you succeed?" he said stiffly. "I don't understand."

"Oh, I mean that, while you are working here, someone in—Germany, say, or America, may anticipate you. After all, there is a good deal of luck in it, isn't there?"

Danton's nod of assent had the bare civility given to a bore whom one is trying to discourage; but Smith seemed to be impervious to discourtesy. He moved a little nearer, reading the names on the bottles standing on the bench. As if accidentally, Danton himself shifted his position so that he came between the stranger and his apparatus.

"Ah, the alkaloids?" It was almost a statement. "Might I ask which group?"

"You're a chemist yourself?"

Surprise forced the question from Danton against his will. Mr. Smith, he thought, must be a chemist, and a chemist of some ability, if, from so cursory an examination of the materials used he could tell the nature of the experiments. Instinctively his outstretched arm covered the open note-book on the bench beside him. Smith noted the action, and smiled deprecatingly.

"You might say that I was a chemist once," he explained. "Before the war... Since—" He shrugged his shoulders, with a suggestion of something foreign in the gesture. "Now, I interest myself only in the work of others."

"I see." Danton's chilling brevity made it sufficiently clear that he had no intention of allowing the stranger to interest himself further in his own experiments. Manifestly he wanted to be rid of him; but Smith would not go. "The Professor probably isn't back," he said after a slight hesitation. "I should call later and ask at the lodge. You might—"

He broke off to look towards the door. Smith turned to follow the direction of his glance. Another young man was on the point of entering. From the overalls which he wore he was evidently a student; but in all other respects he presented a marked contrast to Danton. Well built, and evidently once athletic; but a little tending to fatness; rather excessively hearty in manner; slightly clumsy in movement, and almost too fresh-complexioned, he resembled an amiable, overgrown schoolboy. He did not immediately see Smith standing to one side of the door.

"I say, Danton," he broke out at once, "how about just toddling out for— Oh, sorry! Didn't know you'd anyone here—"

"Not at all." Smith intervened before Danton could speak. "I was only asking Mr. Danton where I could find Professor Roseland. He was kind enough to suggest inquiring at the lodge—"

The slightest possible suggestion of sarcasm in the last sentence nettled Danton.

"I don't expect he's back—" he began. "You see, Hope—"

"Oh, yes, he is!" Hope rejoined cheerfully. "At least, the indicator says 'In'. Have you tried his room?"

"No," Danton snapped. Hope's evident desire to be helpful seemed to accentuate his own discourtesy. "Probably the attendant—"

"Couche isn't at the lodge—I've just come in," Hope interrupted. Danton's manner puzzled him. He turned to the stranger. "I'll take you along there to see, if you like, Mr...?"

"Smith is my name—John Smith. It would be very good of you, Mr. Hope. I believe that I looked into your room a few minutes ago, but you were out...?"

"Oh, I'm not one of the early birds. I just dropped in to see the place hadn't been burnt down, and I'm just popping out again. It's no trouble... See you later, Danton."

Smith had followed his new guide into the corridor before Danton seemed to make up his mind. He crossed the room quickly, and hurried after them.

"I'll just come along, I think," he said. "I'd like a word with Roseland—if he's there."

Smith gave a quick glance at him; then his eyes seemed to stray back to the laboratory. Danton saw the look; his hand went to his pocket. He closed the door.

"I'll just lock up," he said. "That fool Couche might start clearing up."

Hope raised his eyebrows slightly as the key clicked. His own laboratory was always open to anyone who chose to come along, and that Danton should be so careful was outside his experience. He sensed an antagonism between his two companions, and his cheerful nature seemed to be embarrassed by it. They went along the corridor in silence almost until they reached the entrance hall. Smith ventured to break it.

"There are a number of students here?" he asked conversationally. He looked at Danton, evidently expecting the answer from him. "I was not aware—"

"Four."

The monosyllable was discouraging enough; but Hope stepped into the breach.

"Four of us and Seymour," he expanded. "He's the demonstrator—a cut above the likes of us!" He grinned. "Turn left here. That's the lodge—where Couche ought to be but isn't if ever you want him—"

"Couche?"

"The attendant, porter, odd-jobs-man and the rest. He's a regular Pooh-Bah. And it's my belief he has the power of making himself invisible whenever one wants him in any of his capacities.... Hullo! What the devil—?"

This time, at least, the attendant failed to live up to the reputation Hope had given him; for as they turned the corner he was plainly to be seen. It was the unexpectedness of his attitude which had caused Hope's exclamation. He was stooping down beside the door leading to the Professor's laboratory, apparently engaged in trying to peer through the keyhole. A girl was standing beside him, and though he could not remember ever having seen her, there was something which conveyed to Danton an odd suggestion of familiarity. He was racking his memory to place the slight, almost boyish figure and the shock of unruly brown hair when Hope enlightened him.

"Why, that's old Roseland's daughter! What on earth—?"

Before he had finished the question, Danton had hurried forward. The attendant was still intent upon the keyhole when he reached the door.

"What's the matter, Couche?" he demanded. "Anything wrong?"

Couche started. Evidently he had been too much occupied to hear their approach. Red in the face, and more than a little embarrassed, he straightened himself and faced them.

"I don't know, sir," he said hesitantly. "You see, Mr. Danton, sir, the young lady—Miss Roseland—will have it that the Professor has come back and must be here, and if he's here he must be in his room. But the door's locked, and we've knocked and there's no answer. So I looked through the keyhole—"

The girl interrupted him. "You see, Mr.—Mr. Danton, my father was definitely coming back before this morning," she explained, and there was a note of anxiety in her voice. "And we know that, as a matter of fact, he has come back, because the suitcase he took with him for the week-end is in the house. But we can't find him anywhere and no one has seen him. So my uncle, Dr. Boynley, suggested that he might have come back some time very early this morning and have come here—"

She broke off, leaving the sentence unfinished. Danton considered.

"I don't expect there's anything to worry about, Miss Roseland," he said. "If Professor Roseland came back late, he mightn't have wanted to disturb you. And, if he came in here, it's quite possible that he's gone out into the town or somewhere."

"The indicator said 'In'," Smith supplied in a soft, detached voice. "But then, perhaps he wouldn't change it?"

"Then it'd be the first time since I've known him, sir," Couche broke in eagerly. He was obviously torn between the two conflicting views of the situation. "Besides, sir, if he isn't here, his hat is!"

"His hat?"

"On the floor, sir. You can just see it through the keyhole. By the bench there."

He stood aside to make room, and Danton, with obvious reluctance, obediently bent down. Only a small section of the room was visible, and of the Professor himself there was no sign; but undeniably the shapeless piece of felt was the covering which normally adorned the head of Professor Roseland, and if the Professor had another hat, Danton had never seen it. He was frowning a little as he stood up.

"But, even so—" he began.

"Hang it all, Danton, it looks fishy!" Hope intervened. "The old boy—Professor Roseland, I mean—wouldn't buzz off anywhere without his hat, would he?"

Reluctant to be convinced, Danton could find no immediate explanation. He stood staring at the door without answering.

"You see, some of daddy's experiments are dangerous—poison gases and things," Sylvia Roseland broke the silence. "Isn't it possible that he—that something—something went wrong? That he just looked in here to see how some experiment was going, and that—that—?"

"I suppose it's—possible," Danton admitted. "But you must remember he's used to dealing with dangerous substances. Personally, I don't see that there's much to worry about—"

"But—but he might be there! He might be dying—or hurt! Only think, if he were in there, and we were too late—"

"That certainly would be pretty ghastly, Danton," Hope protested. "Isn't there a key or something—just to make sure? After all, if he's not there, there's no harm done."

Danton shrugged his shoulders slightly and looked at Couche.

"Well, sir, there is a key," the attendant said hesitantly. "My pass-key, that is.... But I'd strict orders, sir, never to go in if the door was locked, or unless he gave permission... I don't see that I can risk it, sir."

"But you must!" The girl's agitation seemed to have increased following Danton's grudging admission of the possibility of accident. She looked from one to the other appealingly. "We've got to see! We must hurry! If anything were wrong—"

"Very well. You'd better get it, Couche." Danton gave way apparently in spite of his own disagreement. "You can say Miss Roseland and I insisted."

"But, sir—"

"Get it. Sharp!"

As the attendant started towards the lodge, Danton turned to the girl.

"I think you're fancying things," he said bluntly. "No doubt there's some perfectly simple explanation. And, really, it isn't very often that scientists poison themselves—"

"Perhaps I'm being stupid." Unsuccessfully the girl attempted to smile. "But I couldn't help wondering... You work here, don't you? I've heard Francis mention your name."

"Francis?" Danton asked blankly.

"Francis Seymour—we're engaged, you know. He's a demonstrator or something here, isn't he?"

"Seymour? Yes." Somehow Danton felt at a loss for anything more to say. It had never occurred to him that she might be engaged at all, and that the man should be someone like Seymour, who seemed to have scarcely an ambition or an idea outside his work, rather staggered him. "I didn't know," he said lamely.

"Oh, it's not been announced very long. We were engaged two months ago—privately. I've been working in London—" Abruptly remembering, she broke off and glanced at the door. "Where is Couche?" she demanded impatiently, and then added almost to herself: "But I don't see what could have happened. Only Couche said something about a new poison gas—"

"Poison gas?" Danton's brow wrinkled. "First I'd heard of it... But then, probably I shouldn't. How would Couche get to know?"

"I don't know. He didn't say—Mr. Hope, did he say anything to you?"

"Me? Good Lord, no! I've hardly spoken to him for a week, except when he ticked me off for—"

But with his denial the girl had lost interest in the rest of what he was saying. For the first time she seemed to notice Smith.

"This gentleman—?"

"Oh, this is Mr.—Mr. Smith. He wanted to see the Professor. I understand that he had an appointment—"

"Not an appointment." Smith bowed acknowledgement of the introduction before making the correction. "But the Professor said that he would be pleased to see me if I happened to be in the neighbourhood, and mentioned that he would be returning to-day. He was attending the Pharmacological Conference in London this week-end, I believe?"

"Yes. He went on Friday evening. He was to have been back to-day.... Oh, we must do something. Where is—? Ah!"

Her face lightened as she looked past them up the passage. Danton turned to see Couche coming towards them, jingling a ring of keys, but obviously dubious. But he had not returned alone. Seymour was with him, and the big demonstrator had evidently hurried there immediately upon his arrival. He wore a "Teddy-bear" coat which added bulk even to his large frame, and there was a suit-case in his hand. He was frowning, and his face was pale.

"Francis!" Sylvia Roseland hurried to meet him. "I'm so glad you've come..."

"Sylvia darling! What is it? Couche says—"

He looked from the girl to Danton, who shrugged his shoulders.

"Miss Roseland thinks that the Professor may have had an accident in his laboratory," he explained. "The door's locked."

"An accident? Why should he?" Seymour screwed up his eyes according to his habit when faced with a difficult problem. "But what's this about poison gas? I've heard nothing—"

"Nor have I. Probably imagination."

"It isn't, sir!" Couche broke out indignantly. "I tell you I saw the—"

He stopped abruptly, as though on the verge of a disclosure which, on second thoughts, he decided not to make. Seymour eyed him and frowned.

"Francis, we must see!" the girl urged. "Make him unlock the door!"

"Well." Seymour had the air of having comprehended the situation and made his decision. "Open it, Couche... Here, give me the key."

He took it from the reluctant hand of the attendant, who still muttered something about the Professor's orders, and inserted it into the lock. Then he hesitated. Deliberately he knocked three times on the wood and listened. Sylvia stood beside him breathing quickly, with her hand at her throat. With a click the key turned, and Seymour pushed the door open just far enough to put his head inside. Then the key dropped from his hand, tinkling on to the cement floor. With an exclamation he thrust the door open and dashed into the room.

"Good God! What—?"

The others were at his heels, but in the first moment the big form of the demonstrator prevented their seeing what had made him exclaim. He turned to call over his shoulder.

"Sylvia! Wait— Don't come in!"

In the same instant they saw. The body of Professor Roseland lay on its back in the narrow space between the bench and the wall, sprawling awkwardly with fixed, sightless eyes staring at the ceiling. At the first glance the attitude of the limbs and the ghastly pallor of the face told their own story.

"Daddy! Daddy!"

Disregarding Seymour's warning, Sylvia Roseland pushed past Hope and Danton and threw herself on her knees beside the body; but as she stretched out her arms Seymour gently pushed her back.

"Sylvia! Don't! He may not be—"

For a moment she knelt there, gazing down at the waxen face with horrified eyes. Even to her it must have been obvious that there was no ground for the hope which the demonstrator's words had seemed to suggest. Professor Roseland had evidently been dead for some hours. He was still in his overcoat; the hat which had been visible through the keyhole appeared to have rolled from his head as he fell. Beside his outstretched left hand scattered splinters of broken glass suggested that he had been holding something when he collapsed; the cork of a large flask or bottle was still clutched in the right.

There was a moment's silence in the room. Then the girl seemed to apprehend the truth. With a convulsive sob she rose to her feet, covering her face in her hands. Bending down, Seymour stretched out his hand and felt the thin, wrinkled wrist. He looked at the other three men and nodded.

"Dead," he said unnecessarily in a subdued voice. "Dead some time. I don't know how long—"

"Allow me."

All of them turned at the polite voice. Smith, whose very existence they had forgotten, pushed between Hope and the attendant and came forward. Seymour stared at him as though he saw him for the first time.

"Who—who's this?"

"Mr. John Smith," Danton answered expressionlessly. "He wanted to see the Professor..."

"Perhaps I could help?"

Smith seemed to take permission for granted. He had squeezed himself into the narrow space beside the demonstrator, and was already beginning his examination, with a deftness of touch which suggested the professional before Seymour found anything to say.

"You're a doctor?" he demanded.

"I hold a medical degree," Smith replied without looking up. "Ah!"

His finger shot out abruptly, pointing to the side of the head. In the sparse, iron-grey hair, there was visible the dark stain of congealed blood. Hope gave a startled exclamation as Smith bent forward gently parting the matted locks to look at the wound.

"Lord! Murdered?"

Smith gave no sign of having heard. He finished what he was doing; then stood up, glanced at his wrist watch, and turned to Seymour.

"It is now half-past ten," he said precisely. "Professor Roseland has been dead for at least forty-eight hours—probably more... The cause of death, from a superficial view, would seem to have been heart failure—"

"Heart failure? Oh." There was almost as much disappointment as relief in Hope's voice. Smith looked slowly up at him, and he flushed. "I mean to say—"

"Heart failure," Smith repeated quietly. "But the question remains how it was induced. Many poisons, Mr. Hope, simulate—"

"That's nonsense!" Danton snapped sharply. "The wound—the blood on his head...?"

Smith pointed towards the wall just beside the window. On the rounded end of an iron support which jutted out some eighteen inches into the room, there was a dark smear against the white freshness of the paint. Looking closely, it was possible even to see a grey hair embedded in it.

"Perhaps he struck his head in falling," Smith said. "The head wound is slight—not much more than a scratch. It would not have caused death in a normal man—hardly unconsciousness. It was inflicted about the time of death... I can only repeat that, either Professor Roseland fell and, having a weak heart, died of shock, or—"

"Or?" The girl had been standing in silence, her hands clutched to her breast. "Or what?... You can't mean—"

"Or—the cause of death was something not at once apparent," Smith replied.

"I don't see..." Seymour put his hand to his forehead and paused. "Had he a weak heart? I didn't know... He never said anything—"

"Almost certainly his heart was weak. He probably died almost as he struck the bar. Of course, the blow on the head might have caused the heart failure, except that, bearing the position of the bracket in mind, he could only hit it by lying down. Perhaps he fainted. If not..."

He looked again at the body. His glance seemed to rest for a moment on the smashed fragments of glass beside it; then switched to the rows of bottles on the bench above.

"You think he was poisoned? That's ridiculous!" Danton broke out as he saw the look. "Why—"

Seymour drew a deep breath. "You mean—he might have poisoned himself?" he asked. "Or—or someone else—? Murder!"

Smith smiled slightly. "Or, taking a less sinister view, death might have been due to natural causes not apparent on a casual examination," he pointed out.

"Murder, sir? You said murder?" Couche, who had so far remained hovering in the background, started forward suddenly. "He was hit on the head, sir?"

"Don't!" Sylvia Roseland swayed a little. "It couldn't be—"

Smith shook his head at the attendant. "Or he hit his head," he suggested.

"Then, sir, they got him! He was warned, sir! He'd been threatened—"

"Warned? Who?" Seymour demanded. "What are you talking about?"

Couche looked from the demonstrator to the girl, half opened his mouth to speak, and appeared to think better of it. His face assumed an expression of mulish obstinacy.

"I know what I know, sir," he said. "I'll tell it at the right time—"

Smith raised his eyebrows. His face showed only mild surprise, but he looked at the attendant keenly.

"Murder?" he said, and turned to Seymour. "In any case, you'd better get a doctor—his own for choice. And, if you think—that Mr. Couche's theory has a basis of truth, the police!"

"Police?" Seymour echoed helplessly. "But—"

"The police—at once—if it's murder." Smith looked from one to the other of the horrified faces around him. "It might be a wise precaution to lock the room? And nothing should be touched until they come."

IN the next quarter of an hour, Seymour had given as fine an exhibition of misplaced energy as could well have been wished. He possessed that type of mind which, though careful and logical in the one subject which it comprehends, tends in any crisis of another kind to jump to rash conclusions and take extravagant measures. From the time Smith and Couche had spoken, it never seemed to cross his mind that Roseland's death could be anything but murder. He had rung up the doctor; he had rung up the police. He had anxiously shepherded them all out of the laboratory and assembled them in the library next door but one, and he had not only routed out another student, Wiedermann, from one of the upstairs laboratories, but had telephoned to the rooms of Thursden, the last of the four, to complete his bag. Once Danton had been moved to make a suggestion.

"Wouldn't it be better to wait until the doctor has been?" he asked, not without a trace of contempt. "It's quite possible that, if he's been attending Roseland and this wound is as slight as Mr. Smith says, he'd give a certificate without further trouble... After all, it won't be very enjoyable to the family to have even the suspicion of foul play raised unnecessarily."

"We've got to take precautions," Seymour insisted, with the air of a schoolmaster who resents an impertinence. "Really, Mr. Danton, I am in charge, and must act as I think fit."

Danton said no more. He duly followed the others into the library, and they settled themselves down uncomfortably to wait for the arrival of doctor or police. It was an ordeal to which each member of the party reacted in his or her own way. The demonstrator, with the air of a man who has done everything possible, had seated himself at the head of one of the two long tables, and only an occasional screwing up of the eyes indicated that he was experiencing any emotion other than self-satisfaction. With the girl who sat beside him it was different. White-faced and tense, she leant forward a little in her chair, staring at the opposite wall, with a handkerchief crushed to a tight ball in one hand of which the knuckles showed white. Couche and Smith, at the foot of the table, made an oddly assorted pair. The attendant's lips were moving as though he was rehearsing an imaginary dialogue with the police; Smith was less moved than anyone. His face was absolutely expressionless, and he scarcely altered his position, except once to produce a pocket-book and scribble a few lines in it.

By a common impulse the three students had gathered at the other table, as far away from the demonstrator as possible. Danton sat a little apart, in a mood between gloomy preoccupation with his own thoughts and impatience at what he evidently thought was the demonstrator's officiousness. Hope and the thin, saturnine Wiedermann, were whispering together, and Wiedermann at least seemed to find reason for amusement.

"Old Seymour is enjoying himself!" he sneered. "Quite the little Sherlock, isn't he? Wonder he bothered to send for the police until he'd provided a ready-made solution off his own bat."

"Oh well, I suppose he feels the responsibility," was the more charitable opinion of Hope. "After all, now that old Roseland's popped off he's acting head, I suppose. Don't believe he likes it any more than I would."

"He suffers from the desperate carefulness of inefficiency? Maybe you're right. Funny to think of him in a business like this."

"He's a good chemist—" Hope began defensively, if a little obscurely.

"Oh, he's all right on his subject—or manages to make people think he is. Apart from that he's an ass... I say, the girl's a peach, isn't she? Fancy her falling for Seymour!"

Danton caught the words and looked round distastefully. To Wiedermann, most girls who were passably good-looking were among the more interesting objects in the world. It was one of several reasons why Danton disliked him, and at that time it grated particularly on nerves which were more than a little on edge. Wiedermann saw the look and grinned.

"Well, she looks pretty bad," Hope rejoined. "She doesn't like this if Seymour does.... Looks as though she'd faint at any moment."

Danton glanced across. Hope's diagnosis was undoubtedly justified, and he felt a wave of irritation at the stupidity of the demonstrator in subjecting her to the unnecessary ordeal. Of course, it was Seymour's business, both as her fiancé and as the person temporarily in charge; but then, Seymour had not the type of mind which could appreciate the feelings of a girl waiting like that when her father had just been found dead. She was certainly on the point of collapse. He heard Wiedermann chuckle about something, and guessed that his notice of the girl had been observed; but instead of putting him off it decided him. He rose to his feet and stepped across to Seymour.

"Look here, Mr. Seymour, it may be all right keeping the rest of us hanging about here," he said. "But Miss Roseland has had all she can stand. You'll be having her faint any minute. And anyway, there's no sense in keeping her here. She can't tell the police any more about the finding of the body than we can; and she's been away, so that she probably doesn't know much about his home life. You'd do better to get her uncle—Dr. Boynley—and take her home. The housekeeper could look after her."

Surprise and anger were blended in Seymour's face. He swallowed before he spoke, in what was evidently meant to be a tone of crushing authority.

"Really, Mr. Danton!" he protested. "I can appreciate your chivalrous motives, of course, but I am perfectly capable of looking after Miss Roseland. She is perfectly—perfectly—"

He had glanced towards Sylvia Roseland as he spoke, and for the first time seemed to see her distress. A spasm of something like anguish passed over his face, and his voice as he spoke again was full of anxiety.

"Sylvia!" he cried. "Sylvia! Are you all right?"

The girl did not seem to have heard what they had been saying, but Seymour's words roused her. She made a pathetic attempt at a smile and sat upright.

"I—I'm quite well, Francis," she faltered. "It's nothing... But this waiting—"

"Mr. Danton was suggesting that it would be better if you went back to the house." Seymour gave a quick glance at the student and looked away. "No doubt you are feeling the strain. Mrs. Robertson could take care of you—"

"But—but you'll need me..." In spite of her protestation there was gratitude in her eyes as she glanced from Danton to her fiancĂ©, and Seymour evidently saw it. He bit his lip. "The police will be here—"

"The police won't need you yet. And there isn't much that you can tell them—as Mr. Danton has pointed out." There was an edge on Seymour's voice as he spoke the last words. It seemed as though he was determined to give Danton the credit, much as he hated the intervention of another man. "Your uncle, Dr. Boynley, could no doubt tell them anything which was immediately necessary—"

"I—I don't know." She hesitated, apparently not unaware of the conflicting emotions which animated Seymour. "I—I don't feel—"

Seymour rose to his feet and held out his arm. "I'll... take you home at once," he said firmly. "I should have thought... Couche! Here a minute!"

The attendant started nervously; then rose to his feet and came over to them. Danton was conscious of curious glances from Hope and Wiedermann.

"I'm taking Miss Roseland back to the house," Seymour said in a low voice. "The door of Professor Roseland's laboratory is locked... If the doctor or police should arrive, tell them that I shall be back immediately. You'd better go to the lodge and wait for them."

"Yes, sir. I see, sir."

Ignoring Danton and the others, Seymour guided the girl out of the room. After looking round a little blankly, Couche followed them. The closing of the door was the signal for a relief from the tension which they had all felt.

"Danton, I'm surprised at you!" Wiedermann grinned meaningly. "Cutting Seymour out like that. Thought you didn't go in for—"

Danton's temper, already sorely tried, suddenly broke out. He took a threatening step forward.

"Shut up!" he snapped. "I've had enough of that—"

Hope had risen hurriedly and came between them. But Wiedermann evidently saw the danger signal and did not feel like provoking a conflict. Though there was a sneer in his voice, his next words were apologetic.

"Sorry, old man! Didn't know you were feeling like that."

Danton's anger subsided as suddenly as it had flared out. He felt that he was making a fool of himself and flushed.

"If you must know all about it," he said stiffly, "I simply suggested to Seymour that the girl looked like fainting, and that it would be better if she went home."

"And she took your advice? I noticed that."

Hope, fearful that hostilities were threatening again, stepped in placatingly.

"And the best thing she could do. There was no sense in her staying. A lot of damned nonsense, this idea of Seymour's. If we weren't all students here—"

He broke off as he recalled that there was still a fourth person in the room who had no claim to the title, and as he glanced across at Smith the thought flashed across his mind that the man had an extraordinary capacity for fading out of one's notice. He was sitting as before at the table, and scarcely seemed to have moved; though his eyes were upon them. Hope felt called upon to offer an explanation.

"I'm afraid you must think us a lot of asses," he said frankly. "This affair has set us on edge rather—with the waiting here—"

"If the demonstrator is convinced that a murder has taken place, his precautions are reasonable," Smith rejoined; but from the tone of his voice it was impossible to tell what he thought. "Locking the laboratory door, even at this late hour, might prevent the removal of evidence—or, for that matter, the planting of misleading evidence. And keeping everyone here under his eye until the police arrive might prevent the murderer from making his escape—"

"Good Lord! I never thought of that!" Hope exclaimed blankly. "You mean that he suspects us?"

Smith inclined his head slightly.

"What about him?" Wiedermann asked. "Who's watching him now? I don't see why he isn't in it, too."

"Perhaps the police may share your view," Smith assented courteously; then he smiled. "They may even suspect me!"

Danton looked at him quickly. It had seemed to him that there was a curious intonation in the stranger's voice as he mentioned the last possibility; but his face was blandly unreadable.

"All the same—" Hope began and stopped. The eyes of all four of them were on the door as its opening interrupted the conversation.

The elderly man who entered glanced round the room, and fastened upon Smith as the best source of information.

"What's this about murder?" he demanded. "Mr. Seymour left a message—"

"Mr. Seymour has just gone out, Doctor—?"

"O'Connor. Yes. The attendant told me... Perhaps you can explain?"

"I regret to say that Professor Roseland was found dead in his laboratory a short time ago. There were dubious circumstances about the death, and, in particular, the attendant appeared to be convinced that there was foul play. My own view, which I communicated to Mr. Seymour, was that the Professor had had a heart attack; but Mr. Seymour appears to have adopted the more lurid explanation."

"Heart attack? It's very likely—" The doctor broke off and hesitated. "Of course, I don't know the circumstances," he added in a different tone.

"Professor Roseland suffered from his heart, no doubt?" Smith asked. "You, as his doctor, may be able to give a certificate and set all doubts at rest—"

"Unfortunately, Professor Roseland would never let me examine him." O'Connor frowned. "I knew him as a friend, not as a patient. Though I had warned him—"

"At least you diagnosed a weak heart—" Smith began, but the doctor interrupted him,

"I diagnosed nothing. I merely told him that there were certain indications of it, and advised him to see someone... I don't mind saying that, as it turns out, it's a pity I didn't insist. Matters will have to take their course."

"And consequently, Mr. Seymour's precautions, however excessive—"

"I don't think they're excessive at all," O'Connor snapped. "It's better to be on the safe side than to have everything messed up if anything is wrong."

"But Mr. Seymour—" Danton began, and broke off as the man about whom he was on the point of speaking appeared in the doorway. He hurried forward, followed by a white-haired old man whom three at least of them recognised as Roseland's brother-in-law.

"Glad to see you, doctor," Seymour said nervously. "I hope you can set our minds at rest... This is Dr. Boynley. He tells me—"

"Dr. Boynley and I have already met," O'Connor broke in. "Perhaps he can tell us if the Professor had consulted a physician at all?"

"Not to my knowledge—no, I think not!" Boynley said slowly. "On the other hand, I believe that he was aware that he suffered from heart trouble—"

"Excuse me. You're not a doctor of medicine, I think?"

"Of Letters... Should I say, of Letters only, Doctor?" Boynley gave a wintry smile; and then became grave again. "This has been a great shock, Doctor... If you could reassure us—"

"I hope my examination may do so... The body, I understand, is locked in the Professor's laboratory?"

Seymour felt in his pocket and held out a key. The doctor took it, and turned to leave. As Seymour made as if to accompany him he waved him back.

"If you don't mind," he said, "I'd prefer to be alone... Besides, the police— They're coming now."

If Seymour wished to occupy the centre of the stage, he was fated to be disappointed. Superintendent Carbis had heard of the death of Professor Roseland almost with gratitude; for he had, at the time, been engaged upon a complicated and dubious road case in comparison with which anything would have been a welcome relief. He was not disposed to believe Seymour's excitable message: at the most he expected a sudden death requiring an inquest, or possibly a suicide; but he needed the change. Dr. O'Connor and he had worked amicably together on previous occasions, and it was to the doctor he turned as he entered.

"Morning, Doctor," he greeted him. "You got here before me, I see.... This is a sad affair—all the more to you as a friend of his. Perhaps you could tell me how things stand? I had a message from Mr. Seymour, but—" For the first time he looked at the demonstrator. "Good morning, sir. I'd like to have a word soon with you and the others."

"Good morning, Superintendent," Seymour answered stiffly. "Of course, we are at your service."

The demonstrator was plainly nettled at Carbis's neglect; but the superintendent did not notice it.

"Well, Doctor?"

"I've not made my examination yet," O'Connor said slowly. "But, incidentally, I'd like a word with you in private, Superintendent."

Carbis raised his eyebrows a little in an expression of surprise; then he nodded and looked at Seymour.

"Is there anywhere we could go?" he asked. "If the case is serious, you see, sir, we shall have to take statements."

"There's what the Professor called the office," Seymour suggested. "That is next door to the laboratory—has a door opening from it, in fact. The same key unlocks both doors to the corridor. I have already given it to Dr. O'Connor. The door is the first on the right up the corridor—"

"That will do splendidly... Now, Doctor, I'm at your service."

O'Connor, who had already visited the laboratory on previous occasions, led the way in silence. It was not until he had ushered the superintendent into the little bare room and closed the door behind them that he spoke.

"What do you make of it, Carbis?"

The superintendent hesitated. "That's just what I was asking you," he rejoined. "On the face of it. I'd say it was a case of fools rushing in... From what Seymour said, the murder idea is as flimsy as it could well be. If this man Smith knows anything about medicine, it seems as clear as daylight that Roseland had a heart attack and fell, and I wouldn't give twopence for what the attendant says. So I'm really waiting for you."

The doctor nodded agreement; then he hesitated for a moment.

"Ordinarily, that's just how I should feel myself," he said slowly. "But as it happens... The fact is, this has made me remember a conversation I had with Roseland about nine months ago—when I warned him about his heart, in fact. Perhaps I oughtn't to pay attention to it, because at the time he was quite obviously joking: but it sticks in my mind.... I don't recall the exact words. The substance was that, if ever we found him dead I oughtn't to jump to conclusions about heart failure, as there were plenty of poisons in the laboratory which might give that effect... Of course, it might be coincidence. But, as things are, I'm not sorry that Seymour made such a fuss, even if it's all nonsense."

Carbis pursed his lips as if to whistle. "That's a fact, is it?" he asked. "About the poisons, I mean? You couldn't detect them?"

"I wouldn't say that. You might easily miss them if you had no reason to suspect they were there and didn't do a post-mortem. But, as a matter of fact, practically all poisons leave symptoms that can be found."

"So, if there's a post-mortem, that settles that?"

"Yes. And though this man Couche may be talking nonsense, he gives sufficient reason to have one. I just wanted to give you the tip not to be too sure of 'natural causes'... And now I'll get busy."

He crossed over to the door leading into the laboratory, but it was necessary to use the key again. He looked at Carbis.

"This was locked, too," he said. "That may be important."

Carbis nodded without enthusiasm; for the grounds for suspecting murder seemed to him to be of the flimsiest. He followed the doctor inside. Then a thought struck him.

"Will you have to move the corpse at all?" he asked. "If so, and we're treating this as a possible murder, we ought to photograph it."

"Hardly at all for the present." O'Connor bent down. "He couldn't be lying better if he tried!"

For a minute or two Carbis watched him; then made a rather idle tour of the room. Unfamiliar as he was with the various mysteries of a laboratory, he felt slightly at sea; but so far as he could see at a casual glance, there was nothing very much wrong. If the doctor's verdict favoured murder, he would have to conduct a thorough search; but for the present he was inclined to wait upon events.

"Think I'll just have a word with that attendant, Doctor," he said. "We may as well find out why he's so free with his accusations."

O'Connor only grunted in answer, and Carbis left him to his task. He was on the point of leaving the office by the door through which they had entered when the sight of the telephone made him change his mind. He had left the sergeant at the lodge in the place of Couche, and the private exchange would save time and trouble. Instead of returning to the library, he rang through and gave instructions, and in the interval before Couche arrived made a cursory examination of that room as well. It seemed to be as undisturbed as the laboratory, and he had tired of it even before a knock sounded on the door. He opened it.

"Come in," he invited. "Sit down, will you?"

He indicated one of the three chairs which the room contained, and himself dropped into another. He eyed the attendant closely before he spoke again. The man was obviously nervous, but there was a self-important look about him as well.

"Your name's Couche, isn't it? You're attendant here?"

"Yes, sir."

"Mr. Seymour tells me that on learning of Professor Roseland's death, you expressed the opinion that he had been murdered. Why was that?"

"Well, sir, it's like this." Couche was evidently a little embarrassed. "I clean up the laboratory every day, after the gentlemen have finished, or before they come next morning, sir. And some of them were pretty untidy, always leaving their things about and blaming me if I threw away anything that was wanted. The Professor was as bad as any of them, sir. So I got into the way of always looking at any odd bits of paper that there was any doubt about, sir."

"I see," Carbis assented a little impatiently. He was not greatly interested in Couche's excuses. "Well?"

"Well, sir, I know that Professor Roseland was in danger, sir. It said so on the letter—one I found a bit of, I mean, sir. I can remember the very words. "We have reason to believe that the discovery may be of interest to them, and I wish to warn you to observe all precautions, as they are completely unscrupulous."

He paused, apparently for effect. Carbis frowned.

"Who d'you mean—'we' and 'they'?" he asked. "And what discovery?"

"It was a Government letter, sir; there was a crown on top. Of course, sir, it was the Professor's new gas—"

"What gas?" Carbis demanded, but he sat a little straighter.

"Poison gas, sir. Ten times as deadly—the letter said—as any in use. They'd tested it. He was to go and see them this week-end. He was selling it to them—"

"You didn't keep the letter?"

"No, sir. Of course, I left it with the other papers."

"There was no address at the top?"

"No, sir. It had been torn off... And later on there was a reference to enemy agents, and I knew that meant spies, sir."

Carbis made no comment. He got up, paced the width of the room and back, and stopped again before the attendant.

"Did the letter say anything more?"

"Not that I remember, sir."

Carbis thought. "Right. That's all just now... I'll take a statement later... And, look here, don't go talking all over the shop about this."

"No, sir."

The superintendent was frowning as the door closed. He stood thinking for a moment, made a pace towards the door, and then saw the telephone. He crossed towards it and lifted the receiver.

"That you, Sergeant?" he asked as a voice from the lodge replied. "Get me the Chief Constable—quickly."

INSPECTOR MCCLEOD paced the wooden platform of the little station with an impatience which he made no effort to hide. On one side, over the roofs of the old town, the golden slopes of the Downs rose in a swelling curve; but if his eyes turned continuously in that direction it was not that he admired the scenery. His thoughts were on the cement monstrosity which constituted a last blot half-way up the hillside, beyond even the red tentacles of the housing estates; and he was wondering just how soon an unpunctual train would allow him to go there.

A signal clattered hopefully and he looked up. The train was just rounding the distant curve, and he moved to a strategic position near the exit. As it steamed into the station, he scanned the windows carefully. A glimpse of a waving arm rewarded him and he hurried forward.

"Got your stuff, Ambrose?" he greeted the large man who was struggling in the carriage doorway with a miscellaneous assortment of baggage. "You have—obviously! We ought to have hired a pantechnicon. Give me that tripod—it's light! Train's late."

"Yes, sir."

"I've been here since noon.... My word, you're loaded to the eyes!"

"Yes, sir." Ambrose somehow deposited himself and baggage on the platform and breathed a sigh of relief. He looked round the station gloomily, noting the absence of porters. "I wasn't sure what we'd need, sir—"

"That's right. Only as we're going to walk—"

"Walk, sir?

There was something like despair in his voice, and McCleod took pity on him.

"Yes. You'd better park most of this stuff somewhere. We're just going up to the Institute now, for a preliminary look round... See that white place up there—looking like a bit of the Wembley exhibition that's lost its way? That's the Institute. That is where we're going to do our stuff—or, as I'm more inclined to think, hunt for mares' nests."

"You don't think there's anything in it, sir? I only saw what was in the papers. They gave heart failure as the cause of death. And it seems probable enough."

"It does. Though there are points... Put that stuff away, and I'll explain as we go. That's why we're walking."

Two minutes later Ambrose returned, having abandoned the heavy baggage and looking accordingly more cheerful. McCleod said nothing until they had passed the barrier and, crossing the main road, had struck a footpath which led through the fields to one side of the town.

"Spotted this way just now," he said. "It's nice and quiet. Now, I'll tell you all about it."

Sergeant Ambrose waited in respectful silence while his superior apparently marshalled his thoughts.

"Professor Charles Roseland," McCleod began after a pause, "is the head—was the head—of the Juliot Research Institute. It's spelt with an 'o', and has no connection with Romeo.... The place was founded under a bequest about ten years ago with the intention of bridging the undoubted gap between the time a brilliant young scientist leaves college, and the time when he can hope to get any kind of university appointment. Unfortunately, it hasn't functioned too well that way, but we'll go into that later. It provides places for a professor, a demonstrator, and four students—"

"I've got their names, sir. Demonstrator, Francis Seymour. Students, Paul Danton, Richard Thursden, Dermot Hope and Gaspar Wiedermann."

"Correct. Well, besides the professorship, the bequest allowed a house for the Professor, attached to the laboratory and with a private door into it, Professor Roseland lived there with his brother-in-law, a retired classical don called Boynley, a housekeeper, Mrs. Robertson, two servants, and the demonstrator, who seems to have been a kind of paying guest. His daughter, Sylvia Roseland, had been studying science in London, and I gather was just on the point of returning to the paternal bosom to help the Professor in his work when he died."

"The wife, sir?"

"Died some years ago. On Friday night, at about seven-thirty, Roseland said good-bye to his brother-in-law and went off to attend some kind of scientific beano in London. His intention was to catch the train to London, stay the week-end there, and come back early on Monday morning. He had a case with him and was wearing his hat and coat. Seymour, the demonstrator, was going to the same show, but he left by the earlier train—"

"Which seems to rule him out, sir?"

"If he went. And there's no reason why he shouldn't have done. We'll check it up... As a matter of actual fact, Seymour seems to have had the least opportunity of anyone. I gather that he'd got a friend with him all the afternoon—an old rowing Blue—and they went off and made whoopee. That wouldn't leave him half an hour all told... Anyway, it seems clear that Roseland never caught that train. He must have gone into the laboratory and died there soon after saying good-bye to Boynley. He was found there on Monday morning."

"And no one had gone into the laboratory all that time, sir?"

"Apparently not. The place more or less closes down at week-ends. The room was locked, and the caretaker had strict instructions not to unlock it without permission. Well, this morning he was overdue, and about ten o'clock Miss Roseland seems to have suggested that he might very well have gone straight to the laboratory on arrival and forgotten all about a detail like breakfast. So she went along to the door leading from the house to the laboratory and nearly fell over his week-end case which was in the passage. Failing to get an answer, she went round to the laboratory, found the attendant, and finally, helped by Seymour and Danton, and accompanied by a man called Smith—who just seems to have blown in for no apparent reason—she got into the room and found her father dead."

"The case, sir? How long had it been there?"

"That's a question. You see, that passage is more or less a dead end, and pretty dark. No one uses it who isn't going to the laboratory, and no one has been found yet who went along it from Friday night until Monday morning. The housekeeper thinks she'd have noticed it, but she's short-sighted, and probably wouldn't. So it might have been put there at any time, or Roseland himself might have left it there."

"But does it matter—"

"We don't know yet. The medical evidence, so far as one can tell before a post-mortem, seems reasonably clear—that Roseland, who had a weak heart, fainted, hit his head, and died a natural death. Then the laboratory attendant steps in. As soon as he knows what's happened, he starts talking about murder and foreign spies and poison gas—a most extraordinary rigmarole which, according to the accounts I've received from the local police, simply makes no sense whatsoever."

"Well, sir, people often do that."

"Yes. But there's a certain amount of plausibility about it in this case. During the war, Roseland was actually engaged on Government work. Quite a lot of those dons were in one way or another. And he seems to have liked to talk about it anyhow. It's quite possible that, on the quiet, he had made some discovery."

"But the spies?"

"Couche's account is circumstantial. Apparently he invariably reads all stray letters that he sees lying about. On two occasions he has seen letters from a Government department referring to the new gas; one warning him to observe secrecy and take precautions against enemy agents; the other fixing an appointment in London for this week-end. Of course, if there's anything in all that, the Pharmacological Conference would come in handy as a blind... I've not seen Couche myself yet—or, for that matter, most of them."

"It should be possible to verify that, sir."

"It should. No doubt it will be, ultimately. Only, if it's anything to do with official secrets, the higher military authorities can be particularly sticky, even with the police, and the Secret Service sometimes likes to be secret about nothing in particular. There may be quite a lot of red tape to unroll.... Anyway, that's the main reason why the local police rather precipitately decided that it was a matter outside their province and called on the C.I.D."

"The main reason? There are others, sir?"

"The other isn't so much a reason as a state of mind. Having once got the murder idea into their heads, or at any rate, having once decided that murder was possible, it seems to have occurred to them that all kinds of people in the immediate neighbourhood had motive, opportunity and means. You see, though they call it pharmacological research, which might mean anything as harmless as a dose of dandelion, as a matter of fact every one in that Institute is working upon some particularly subtle poison. It's no use asking me exactly what, at the moment, because I don't profess to understand the language. I tried to get an idea from Seymour what Professor Roseland's pet subject was, and he murmured something about the 'synthesis of the derivatives of apomorphine', which I've not digested yet. But, roughly speaking, Seymour was dealing with some South American arrow poison—"

"Curare, sir."

"No—less pronounceable. Danton seems to have been trying to make an entirely new alkaloid, improving on Nature. Hope was dealing with aconite, Wiedermann with arsenic, and Thursden with something that sounds like stropanthus—or is it sporanthus? Besides which, they'd all got access to any kind of poison they wanted, and knowledge enough to make it if it wasn't there. Under the circumstances, it looked to the police as though it was simply absurd for a man really to die of a weak heart without any help from someone or other. You can see the attitude. What, they ask, is the use of all these young men who don't like Roseland having all this poison and letting the old boy die naturally? I don't say that it's sound, but there it is."

"Then Professor Roseland wasn't popular?"

"Quite the reverse. If any of them did bump him off, he got what he deserved. From what I hear, he was a scientific thief. He had been quite a good scientist, though he seems to have fallen off. Of recent years, though, he's enhanced his reputation simply by using the brains of the students at the Institute. It's a condition of their studentships that only the Professor can publish results. When he'd finished publishing any work done there, apparently one gathers that Professor Roseland had done everything, but that Mr. So-and-so, whose name is mentioned at the end somewhere, washed out the beakers and handed things to him. It may not be a good motive for murder, but it's the kind of thing which could quite easily get a man's goat."

"No doubt, sir. But it's hardly connected with the spy business, is it?"

"That's one trouble—it isn't. Because it's really not very probable that any of the students were connected with the 'agents of a foreign power' that Couche made so much of. Though it's possible... Well, once having started the ball rolling, murderers grew thicker than blackberries. There was Boynley, who'd had some kind of quarrel with Roseland. Even Couche managed to be a suspect."

"The other man—Smith? The man who was there when they found him?"

"So far as I can see, he doesn't come in at all, except that he was there when they found him. The superintendent says that he produced a letter from Roseland asking him to drop in some time and talk about old times, and that's what he did. But he chose the most inconvenient time possible, just when they found Rosalind dead. Apparently he had rung up on the Friday night, and had been told that Roseland had gone away."

"Then he was here on the Friday?"

"I believe so. But that scarcely makes him guilty of murder... In fact, we've still got to show that there's been a murder, and the odds are against it. Consider the possibilities. First, accidental death of two kinds. It may have been mere heart failure, for Roseland's heart was certainly weak. Or, less probably, it might have been that Roseland made a mistake in some experiment he was making and killed himself. The one thing that lends colour to that is the broken glass at his side. I'm told the bits would make a sort of large jar thing of the kind one might keep a gas in. But I don't believe it myself. The next is suicide. There's no discernible motive, and I imagine one can rule that, out. The third is murder."

"But the fact seems to be, sir, that there's no evidence of murder at all except the talk of this man Couche and the imagination of the local police."

"Helped by the Press. Because though you saw the first account which made it accidental death, I don't mind betting that by now there are papers selling on the London streets hinting at something much more exciting. You see, with so eminent a man as Roseland, the papers are bound to print a fair amount. And with Couche going about hinting at spies and poison gases and so on for the newspaper men to get hold of, and the certainty that he'll say the same stuff at the inquest if he gets a chance, I don't see that the police could very well have avoided making as full an investigation as possible—not unless they wanted to run the risk of getting hauled over the coals pretty thoroughly. No, I don't believe I blame the police. I'd have done the same myself in their place."

"Well, sir, assuming that it was murder, isn't it a question of who had the means and opportunity?"

"If it's a case of a 'subtle Oriental poison'—and they're so rare that I've never met one—all the members of the Institute become suspect automatically, because they represent an accumulation of knowledge about poisons it would be hard to find in a single building anywhere else. And, if it was a poison, it seems pretty clear that it was one of them—unless it was Couche, who might have picked up the knowledge somehow."

"There's the daughter?"

"Admittedly she's a scientist, but she seems to have been fond of her father. Also she wasn't anywhere near the place, if the doctor's estimate is correct. And she hadn't been for weeks. So she hardly matters. I decline to believe that Boynley or the housekeeper or the servants did it in that way... But there's the other possibility. I mean, that he wasn't murdered by poison at all, but that he was simply hit on the head and died of it. It might even be manslaughter—he was pushed over in some sort of quarrel and hit his head. And either of those last two allow anyone to have the means who has the opportunity. All that's necessary is to get into the place."

"There are just the two doors, sir. Were they locked?"

"Actually there are three doors. There's a mysterious sort of basement entrance through the fire-hole; there's the ordinary front door, and the door from the house. All of them would be locked at that time of night, unless the Professor had left the house door open. But all the students and the demonstrator have keys—and, of course, so has Couche. So that's no great help, except so far as it may rule out an outsider."

"On the other hand, sir, if we can't find any trace of poison, it might suggest that it was an outsider. I mean, with such poisons at their disposal, would any of them, planning a deliberate murder, have used such a crude method, or wouldn't poison have been used and an attempt made to make it seem natural death? It seems the obvious thing to do."

"Yes, perhaps. But some people are strangely blind to their opportunities. Still, if we decide that it was murder, we'll have to extract alibis from all of them." He sighed and, as the path turned sharply to the right to join the carriage road to the Institute, pointed to the buildings which were now plainly visible ahead. "Anyhow, there's the place. The lower part to the left is the Professor's house. Ugly, isn't it?"

But Sergeant Ambrose was studying it from a point of view which had nothing to do with the æsthetic. Owing to the slope of the hill, the front walls were considerably higher than those at the back, and such windows as were visible were at a height from the ground which made entry by means of them impossible except with the help of a ladder. A flight of steps led up to the front door, but there was no window within reach.

"If anyone got in, except by the doors, sir," he remarked, "it must have been at the back."

"True. Only, as a matter of fact, the Professor's laboratory is at the back, and the windows there are quite near the ground, I believe. The superintendent said he was having those examined. As I say, we're hunting for mares' nests very hard in this case. So we might find anything. One can never tell what— Hullo!"

The cause of his exclamation was apparently the harmless-looking man who was coming down the carriage-way towards them. The inspector was staring at him as though he could not believe his eyes; but the sergeant could see nothing about the newcomer which seemed to warrant any such attention. He might have been anything; perhaps he was most like some kind of professional man. McCleod seemed to make up his mind and advanced into the road to intercept the stranger.

"Good afternoon," he said. "Mr. Robinson, isn't it?"

The man to whom he spoke stopped, raised his eyebrows slightly, and looked from McCleod to Ambrose. Then he smiled forgivingly.

"Pardon me," he said. "Smith is my name—John Smith."

"It wasn't in 1917," McCleod said bluntly. "I don't expect you remember me—"

"Why, if it isn't Sergeant McCleod—I beg your pardon, I read somewhere that you had been promoted, Inspector." He smiled again. "This is a pleasant meeting—though I suppose we must both regret the event which caused it. No doubt I am right in thinking that it is Professor Roseland's death which brings you?"

McCleod said nothing. He was, as a matter of fact, already regretting that he had said so much. It would certainly have been better to allow Smith to think that he had not been recognised.

"An old acquaintance of mine, Inspector. Our friendship, if I may call it so, dates from the time when we first met and you were a sergeant... And I, of course, was Robinson then. Yes, it was Robinson. That was a pseudonym. I really am Smith. You can look me up!"

"But you really were Robinson!" McCleod rejoined, and stopped himself. "I suppose you'll be staying here for a few days?" he asked casually.

"At the Crown Hotel... I had already informed the superintendent of my intention, Inspector. But I should be delighted if you would look me up. No doubt, in any case, you would like to see me officially. But not now, I imagine?"

"No," McCleod said tonelessly. "Not now."

"In that case, you will excuse me? No doubt you yourself are busy at the moment... Good afternoon."

McCleod did not reply to the salutation. He stood staring after the other's receding back, and Ambrose could make nothing of the expression on his face. At last, without a word, he turned and began to climb the hill. They had gone several yards before he spoke at all. Then it was brief and pointed.

"Blast!" he said fervently.

"You knew him, sir?"

"Oh, no! We were perfect strangers! You must have seen that!"

Ambrose relapsed into an abashed silence. They were nearing the Institute gates before McCleod spoke again.

"There may be something in Couche's tale," he said, half to himself. "It's queer. Here's Mr. Smith-Robinson... And Roseland did Government work in the war—"

"But how did you meet Robinson, sir?" Ambrose ventured rashly.

McCleod smiled mirthlessly. "I tried to get him shot," he said. "And, damn it! I failed!"

NEVER very cheerful at the best of times, the face of Superintendent Carbis seemed gloomier than ever when he met them at the door of the Institute. He acknowledged McCleod's introduction to Ambrose almost absently, and there was plainly a good deal on his mind.

"What's wrong, Superintendent?" McCleod asked. "You're not looking very happy. Found anything?"

"Wrong?" Carbis eyed him sadly. "Well, I don't know. Yes, we've found several things—too many if anything!"

"That's surely a fault on the right side?" McCleod smiled. "Just what?"

"You'd better see for yourself. I'll take you along to Roseland's room in a minute. Maybe you'd better get a general idea of the place first?"

He led them to a point in the entrance hall from which they could look along both the downstairs corridors, near a flight of steps which evidently led to the first floor.

"You see," he said, "the laboratories themselves are grouped in the shape of a capital 'L' with the house sticking on to the shorter side. Both upstairs and down there's one long corridor and one shorter one. In fact, barring outbuildings, it's just like an 'L'."

"I see," McCleod said patiently. "Like an 'L'."

"That's what I said... Downstairs along the shorter corridor there's the library, a place called the office, and Roseland's laboratory, with the door leading to the house. Above these are Seymour's room and a lab, used by no one in particular. On the longer corridor there are Hope's and Danton's rooms, with a storeroom and a cloakroom, and above Thursden's and Wiedermann's with another storeroom and a cupboard."

"Seems to be plenty of storage room," McCleod murmured. "A handy little place."

The superintendent ignored his levity.

"The door to the right of the entrance leads to the lodge. The telephone exchange is there, and Couche ought to sit there when he's nothing else to do—which, according to him, is never. He seems to be more overworked than a policeman. The basement rooms run right under the building, but half of them aren't used for anything. Couche has a workshop in one, and another is for coals and heating apparatus. That's the general lay-out."

McCleod nodded. "How about locking up?" he asked. "Is the entrance door locked by day?"

"No. With luck or a little assurance, anyone could come in. One would just look at the indicator, see who was out, and, if anyone inquired at all, say you were looking for him. That would be easy."

"I suppose the students lock their rooms?"

"Sometimes, sometimes not. It's all very haphazard, in view of the fact that there's enough stuff to poison a town here. Some of that's supposed to be locked up, but generally isn't."

"But I gather Roseland's door is generally locked?"

"No. It's locked sometimes, and, when it's locked, Couche has been warned to keep out. But you may take it from me that there's no real locking up here in the daytime."

McCleod frowned. "Then anyone could get in while it was open, hide in one of those store-cupboards, say, and be there at night?"

"Exactly. That's one of the depressing things I've found out. Though, actually, it's not so important as it seems.... The place is only locked up at half-past six, and even so all the students and staff have keys."

"So, what at first looked like a closed shop is actually as open as the day?"

"In the day—yes." Carbis sighed, and his gloom increased. "Thanks to the infernally casual way they have of doing things. But one thing we've found in the laboratory has some bearing on this question. You'd better come along and see."

He was leading the way along the passage when the sound of voices from the lodge made him turn to look. The policeman on duty there was arguing with a supercilious-looking young man who had just entered, and who seemed to be trying to push his way past with scant ceremony. Carbis and McCleod barred his way as he succeeded.

"Just a minute, sir!" McCleod requested politely, and no one could have sworn to the faintest possible emphasis on the "sir" which made the young man scowl. "Might I ask what—?"

"What's this? First that fool on the door, and now— If you must know, I was sent for. I had a message from Mr. Seymour—"

"You'll be Mr. Thursden?" Carbis asked. He did not add that the description which had aided his identification had been "a swelled-headed young swine". "Mr. Seymour said he'd sent you word."

"Of course." Thursden looked from one to the other insolently. "I suppose you're policemen? But what's all this about? My landlady says Professor Roseland was murdered. That's absurd!"

"I see, sir," McCleod assented. "But Professor Roseland died suddenly. That's got to be investigated... You were rather late in hearing, sir."

"I've been away," Thursden vouchsafed. "I have just got back."

"To London, sir?"

Thursden stared. "Yes—if you're interested," he said.

McCleod's air was wonderfully humble. "I was wondering if you had perhaps attended the Pharmacological Conference? I believe that Professor Roseland and Mr. Seymour were going there?"

"Conference? Good Lord, no!" Thursden grinned, then again became dignified. "I know nothing about it—or them. I have nothing to say at the moment."

The inspector's eyebrows twitched, but he maintained his attitude of meekness. "Not at the moment? I see," he agreed sweetly. "But I'd be glad if you'd stay available for a little while.... There may be questions we want to ask."

"I was going to stay here until tea-time. That should be sufficient for you."

A slow smile spread over McCleod's face as Thursden turned away without another word and strode towards the stairs. He looked round to meet the furious gaze of the superintendent.

"The young pup!" Carbis exploded. "Just for that, I hope you rub it into him good and hard—even if you can't hang him."

"The Lord has certainly given him a good conceit of himself!" McCleod smiled. "Carbis, I'm surprised at you! You wouldn't have me be rough with him—if he can spare me a moment later?"

Carbis grunted. "That's one alibi, apparently," he said. "And it's one I'll test to the last minute!"

"Yes. And alibis for the staff and students may be important; for it looks as if—assuming there's been a murder—either the students or a friend of Roseland's was involved. If he didn't always lock the door of his laboratory, he certainly did on that particular day. Probably he let the murderer in himself."

"Don't know... That's one of the things we've found. You'd better come along and see."

Following the superintendent up the passage, McCleod noted that the windows on the inner side of the "L" to which Carbis had likened the building could be ruled out as a means of entrance. They were of the type which do not open, except for a six-inch ventilator at the top, and if any unauthorised person had got in otherwise than through the doors, it must be by way of the windows in the laboratories themselves. Carbis stopped before the last door in the corridor and opened it.

"Here," he said.

From a high stool where he had been unsuccessfully trying to make himself comfortable a plain-clothes detective slid to the ground as they entered. He was not the only occupant of the room. Rather to McCleod's surprise, Seymour was standing by the window, looking acutely uncomfortable, and obviously trying not to look at the body which still lay sprawling beside the bench. His face must have betrayed his thoughts, for Carbis hastened to explain.

"Thought that we'd better have someone on hand who knew about all this stuff," he said, waving a hand towards the rows of bottles and apparatus. "You see, it's not impossible that they might have had something to do with it, especially if Couche is speaking the truth. Mr. Seymour was good enough to come and help us. And he's in charge here, anyway."

"Yes, of course." McCleod's assent lacked enthusiasm. "Nothing has been touched here, I suppose?"

"The doctor may have had to shift the body a bit in making his examination, but I don't think so. What d'you think, Mr. Seymour?"

"Pardon?" Seymour turned hastily from looking out of the window. "What do I think?"

"Would you say that the body was lying as it was when you first saw it?"

Seymour looked obediently and quickly averted his eyes.

"Yes," he said nervously. "Oh, yes. I should say that it was."

It might have been pity for the demonstrator or another motive which made McCleod turn to the superintendent.

"I think it would be best if we asked Mr. Seymour any questions which occur to us immediately and get it over," he suggested. "We won't detain him any longer than we have to. No doubt this business has meant a lot of trouble for him and he has plenty to do."

Seymour nodded unhappily. Moving towards the bench, McCleod studied it for a moment, looking from the apparatus upon it to the dead body on the floor and back again.

"I suppose that we must assume something like this," he suggested. "Professor Roseland was going to this conference affair in London. Before he set off to catch the train, he may have thought of something he had to do in here—either he wanted to look at an experiment which was proceeding, or he came to get something. We can't tell whether he did what he intended or not, but for some reason he was standing in front of this bench when he died. The point is this, Mr. Seymour. Can you tell us, from the bottles and apparatus on the bench, what the Professor might have been doing?"