RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

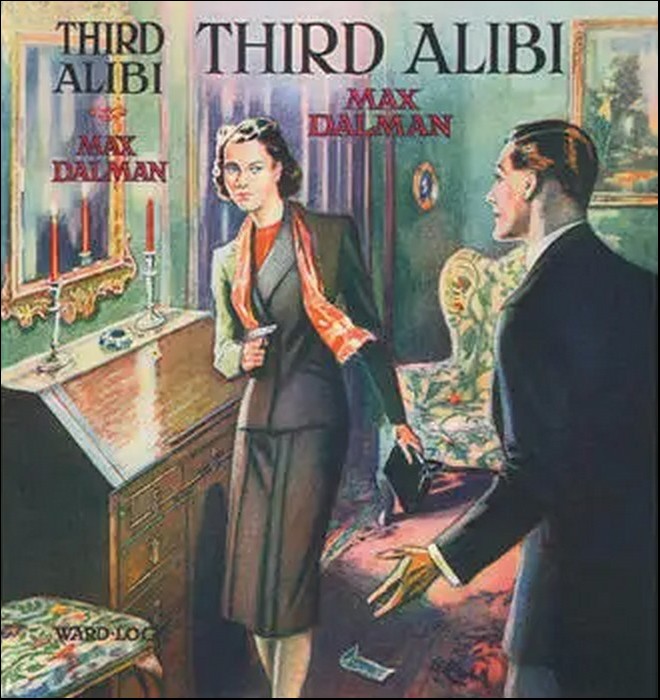

"Third Alibi"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1943

When Timothy Wynne, late Oxford student, made an after-dinner wager with fellow-student George Petworth, that he would break into his uncle's mansion, he little bargained for the series of hair-raising adventures that were in store for him, involving a most sensational murder and the eventual breaking of the three alibis of the murderer.

WITH a last desperate effort Timothy Wynne pulled himself up, hung dubiously on the verge for a moment, then with a heartfelt sigh of relief gained the ledge. Perched precariously in the darkness on a stone hardly more than a foot wide, he wiped from his face the perspiration which was not wholly due to the effort of climbing, and had time to consider the situation.

At any rate, he had got up. So much was certain, and it was all to the good. But it was equally clear that he could never get down the same way. Adjusting his position on the narrow foothold, he gingerly explored the damage to the wrenched arm which, only a few minutes back, had nearly made him fall. It was not broken. In all probability it was not even dislocated; but it was undoubtedly twisted, badly enough, he decided, to render it useless for the time being. If he had just managed to reach the ledge with both arms, he could certainly never achieve the descent with one. For a moment he felt depressed at the thought. It might complicate matters. Then his natural spirits reasserted themselves, and he grinned in the darkness. Luck was still with him. He had more than a chance yet of being one up on George, and incidentally, of being five pounds richer.

"If you go in, you're sure to win..." He quoted to himself from his favourite author. "Though there isn't a lady... And can I get in?"

It had been a good dinner. The White Hart had risen nobly to an unforeseen occasion; and that was the reason for his presence there. George's mixture of drinks had been indiscreet and indiscriminate. No doubt that had made the man argumentative. Admittedly Timothy himself could not recall the precise stages by which the conversation had passed from Church Disestablishment to cat-burglars; but his own sobriety was adequately proved by his scaling the nastiest wall he had ever encountered. Still, that was not the real point of the bet. George had not denied he could climb; it had been in what he alleged to be the higher qualities of housebreaking technique and nerve that he had thought Timothy deficient. That part was still to come, and the sooner it was over the better.

He turned carefully on the sill and, with his one good hand, started to investigate. The window should be open, or at least unlatched. But, judging by the rest of the information George had given him, it would not have been remarkable if it had been secured with bars and steel shutters. At least there were none on the outside. His fingers encountered the cold, damp surface of the panes; then just above the frame of the upper sash. He nodded approvingly. This time George had not failed him. Pulling himself to his feet, not without an unpleasant recollection of the flagstones forty feet below, he felt the edge of the woodwork and got an arm inside.

The lower sash came up with scarcely a sound. He was glad of that; for with a single arm the scramble through the upper opening would have been troublesome and risky. Though George had said his uncle's house ought to contain only an aged retainer of poor sight and defective hearing, even he might be aroused by a heavy fall or a smashed pane; and, since violence was ruled out by the terms of the bet, detection even by the sexagenarian would be fatal. Now it was simple enough. Lowering himself to the sill again, he inserted a leg, groped with it for a second or two in search of obstacles, then followed it with the other and slipped inside.

It was black in the room; not merely dark as it had been on the wall outside. There was an inkiness that seemed stifling. He could just make out the shape of the window, and nothing more. And, as he stood there, he felt a vague feeling of disquiet. Of course it was all right. If he were discovered, it was all a joke. But for a minute or two he stood there uncertainly, straining his eyes uselessly in the gloom and listening without result for sounds which did not exist.

Then the thought that he was actually justifying George's jibes spurred him to action. The first thing was to find the door. He started forward rather over-optimistically, and at the second step tripped over what seemed to be a folded carpet and nearly went headlong. That sobered him. He remembered the torch which he had borrowed from the landlord before setting out. The chances involved in showing a light and stumbling about in the dark seemed about even. Extracting the torch from his pocket, he covered the bulb with his fingers and let a mere pinpoint of light flash round the room.

There was the door. He seemed to be in some kind of lumber-room. George had been wrong again; for it should have been a servant's bedroom temporarily untenanted. Memorising the positions of the more relevant obstacles, he switched off the torch, dodged stealthily across the room and found his objective. Not without distrust he groped for the handle and turned it. The door yielded, and the next moment he was in the passage.

Just for an instant he risked another flash. The passage was according to schedule; he caught a glimpse of banisters at the end. He started down it quite confidently, secure in the knowledge that the aged guardian of the house slept on the next floor and in a different wing. In spite of the pain of his arm he felt quite cheerful again. An appropriate song from Gilbert came to his mind, and he hummed it under his breath.

"With catlike tread upon our way we steal..."

Along the passage all was straight sailing; the staircase was another matter. He was painfully aware that his tread as he descended was anything but feline; it far more resembled a herd of elephants thundering through the jungle. Every step creaked; the banisters seemed to be threatening collapse, and it was with a great feeling of relief that he gained the bottom.

Just in front another staircase led off to the ground floor. Two passages led from the landing, one on each side but at right angles to each other. So much another brief flash of his torch told him and it was satisfactory. George's bedroom lay at the extreme end of the left branch, and should be easy to find; but now he would have to go warily. The caretaker servant slept in the other wing, and was probably in his room. He should be asleep, if the noise of Timothy's descent had not roused him trembling from a dream of earthquakes. At least it would be unsafe to use the torch until he was in the room itself. Reaching the corner, he shone the beam once along to assure himself that the way was clear; stood for a moment listening, and was on the very point of going forward when he turned again with a start, and something very like a gasp.

Some little distance along the other passage a door opened suddenly, casting a yellow glow of light against the opposite wall. Outlined against it, a vast shadow stood threateningly, apparently on the point of emerging. Then the sound of running water came to him. It was reassuring. Probably the aged guardian of the house had been performing his ablutions. Perhaps he had forgotten the soap. At least with the splashing it seemed unlikely he could have heard anything, or that he would wander far in searching the house. But the next second his hopes were dashed. A grave, deferential voice reached him.

"Certainly, sir. I will see that they are dealt with.... I do not think there will be any stain, sir."

To Timothy the words had somehow a horribly sinister ring. No doubt it was nervous strain that made a ghastly vision of blood and murder flash across his eyes. How were they to be dealt with? What sort of stain? Even the splashing took on an ominous significance. He heard a mumbling, indistinguishable voice from inside the room; a respectful, inaudible reply; then the shadow enlarged suddenly.

In a flash Timothy was round the corner of the passage. Just what was happening he did not know; but even in that moment two things were plain. There were at least two persons in the house, and they were awake and active. He heard measured steps approaching, and peered round the corner, temporarily regardless of the risk in his extreme curiosity.

The man coming down the passage was only silhouetted against the glow from the door. Timothy could not see his face, but he seemed to be in evening dress, and something black was draped over his left arm. With his mind still running on sensational lines, Timothy wondered what it could be. But a more urgent question was where he was going. If it was down the stairs, all might be well; if along the passage, it was hard to see how Timothy could possibly avoid detection. The door from which the light came shut suddenly, leaving the passage momentarily in darkness. Then the glare of a pocket-lamp made Timothy back hurriedly. He half turned, with the idea of making a dash for it and perhaps gaining George's room before the other turned the corner. The footsteps stopped. A door opened and shut, and the light vanished.

There were cold drops of perspiration on Timothy's brow. It was at least a respite. The man in evening dress had gone into one of the other rooms. It gave him his chance. In an instant he had turned and was making his way through a gloom which was doubly intense after the light at a pace in which caution was perhaps sacrificed to speed; but at all costs he must gain the room at the end before anyone emerged.

The wall at the far end brought him up suddenly, with a painful blow on his nose. He scarcely regarded that. The door should be right beside it. His fingers touched the woodwork, found the handle, and turned it. Next second he was inside, and for the moment safe. He stood listening for an instant. There was not a sound. He was aware that he was breathing quickly, and that his heart was thumping. George had been right. Certainly the job needed nerve. A fleeting doubt as to how he was to get out again crossed his mind; but the great thing was that he had got there. The next step was obvious. He had merely to pick up some trifle as a guarantee of good faith and then he would be free to consider the problem of his getaway. Opening the door a crack, he peered out. Everything was quiet. He closed it again gently. A light should be safe enough. His finger pressed the switch, and he shone the beam round.

It was a large room, obviously one of the biggest in the half-farm, half-manor house that the place seemed to be. And at the first glimpse Timothy was conscious of a certain surprise. It was not in the least like any room he would have expected George to have. The furniture was severe, almost Spartan in its simplicity; but it must also have been terribly expensive. An atmosphere of extreme neatness characterised every detail of the arrangements, and there was not a sign of the comfortable disorder which had marked George's rooms at Oxford. The light of the torch shone for a moment on a large engraving over the mantelpiece, and he was aware of a slight shock. Unless he was very much mistaken it was a portrait of Wordsworth, whom of all poets George hated most.

He felt a sudden doubt. Had he got the right room? At least he had faithfully followed instructions. Possibly the furniture, even the pictures, were dictated by George's uncle; though even the retired Indian Civil servant could scarcely have been expected to have such tastes. But he could not afford to loiter. The great thing was to grab something and go. A small ash-tray on the bedside table caught his eye, and he moved across to it. It was of small intrinsic value, but distinctive enough. He had decided it would do, and was in the act of pocketing it when the click of the door lock reached him.

Timothy ducked hastily. He was barely in time. Certainly he would not have been if the newcomer had not taken an unconscionable time in opening the door. It was as though at the first click he had merely tried it; for there was quite a long pause. Then the handle turned again, and he had the impression that the door was open. But by that time his torch was out, and he was crouching down beside the bed, hidden at least from anyone who merely glanced in casually.

Now that the moment had come he was conscious of an excitement which was not unpleasant. Slowly bewilderment succeeded it. What was happening? There was no sound of anyone entering; there was not a glimmer of light. For more than a minute there was a silence in which he could hear his own breathing. At last a light footstep sounded on the threshold, the door closed softly, and he knew that he was no longer alone.

A whole scries of questions raced through his mind. Who was it? What did he want? Why was there all this stealthy business? Why was there no light? Then a match flared, held high as though the newcomer were surveying the room. Timothy was half tempted to peer over the bed; but that would have invited detection at once. By bending down he could perhaps get a view of the other's feet under the edge of the counterpane, and he acted on the idea. Then he gave a gasp which might well have been audible. It was a woman!

He had barely time to ascertain so much before the match went out, and it was only as he waited in the darkness that he supplemented the fact with the impression that she had had a pair of particularly graceful ankles. There was no leisure to dwell on that. He caught a sound of gentle movement, as though she was crossing the room. Then a match flared again, this time beside the desk near the far window. The hand which held it was just out of sight; but from the fact that the light increased, increased again, and then remained steady he guessed that she had lit the pair of candles that stood on the desk. There was a jingle of keys; a lock snapped back, and a drawer was opened. At the risk of exposing himself to view, Timothy edged forward a little to a position from which he could see.

His guess about the ankles had been right. Moreover, so far as one could judge from a back view, the rest was according to sample. There was grace in every line of the figure which knelt beside the open drawer, and the candles gleamed on the glossy black hair. Once as she turned to hold a paper up to the light he had a view of a half-profile which was quite consistent with the rest. Then she bent to her task again.

Just what she was doing was a mystery. She seemed to be searching systematically, taking drawer by drawer, and as soon as she had finished one side she turned to the next. There was something very odd about it. Although she was hatless she seemed to have just come in from outside; for she wore a grey tweed costume, with a scarf hanging loosely at the neck, and there was mud on the brown brogue shoes.

Her search was proceeding methodically, but with obvious haste, and she seemed to be in no doubt what she wanted. But for some time her diligence was unrewarded. It was in the last drawer that she seemed to be successful at last. She stood up, extracting from an envelope a small wad of papers which she scrutinised under the light. Then, as she stooped to close and relock the drawer, Timothy realised his own danger.

He was no less visible to her than she to him. She had only to turn and she must see him immediately. And then? Timothy was not sure. He was too puzzled about the whole business. But a bright idea flashed across his mind. It was just possible that he might be able to back under the bed before she looked around. He slid one leg sideways and backwards, and then disaster came. His shoe slipped from the edge of the carpet, and scraped noisily along the boards.

She turned in a flash. Apparently she had been stuffing the papers into her handbag, and in her haste one of them fluttered unnoticed to the ground. He heard her gasp. For half a minute she stood staring at him as though she had been turned to stone.

Timothy rose to his feet. Any further crouching was not only useless but undignified. He smiled in apology.

"I say," he began placatingly, "I'm fearfully sorry... It's quite all right."

The last words died on his lips. She made a quick movement as though to push the papers into her bag. For the first time in his life he found himself looking into the muzzle of a small automatic which had somehow appeared in her hand.

For a moment he could only gape at it. Then he took a pace forward and smiled.

"It's really all right—"

"Don't move!"

On another occasion the voice might have been charming; and she was certainly a pretty girl. But the command was backed by a threatening movement of the gun, and Timothy was conscious of a slight nervousness. It was a small enough pistol, it was true, but quite a small bullet could kill one. And there was a deadly earnestness in her manner.

"Who are you? What are you doing here?"

Timothy was only too glad to explain. "My name's Wynne—Timothy Wynne. It's quite all right my being here, though I expect I scared you. George said I could—that is, he said I couldn't. A bet, you know—"

The explanation did not seem to enlighten her.

"George?" she echoed bewilderingly. "A bet?"

"George Petworth, you know—the nephew of old Petworth. He bet I couldn't cat-burgle the house and get away with something from his room. Must be some mistake, you know. He said the house was empty."

"George Petworth?" She echoed the name, and all at once seemed to understand. "You thought this was his house? That this is his room?"

"Great Scott!" Timothy's jaw dropped. "You don't mean—?"

Abruptly it struck him as funny. He laughed. But the girl did not reciprocate. There was a worried frown on her face.

"I mean that you're in the wrong house—if you're speaking the truth—?"

"Oh, it's true enough. George himself will verify it. You could get him on the phone at the White Hart. I say, I'm fearfully sorry. Then this isn't Three Gables at all?"

She drew a deep breath, and the hand which held the gun dropped to her side.

"No," she said slowly. "It isn't Three Gables. Then—then you mean that it's all a joke? You were burgling for a bet?"

Timothy nodded. "Which, incidentally, I've lost," he said ruefully. "I'm not allowed to escape if you let me. And, anyhow, I haven't burgled George's room. I'd an idea something was up—"

It seemed as though an idea occurred to her suddenly. She glanced down momentarily at her handbag; then looked up, and there was a new alarm in her eyes.

"You must go!" There was an urgency in the words which startled him. "You must get out—quickly. Before anyone finds you. Anyone else— You must not be found—"

"I suppose it might be a bit awkward." Timothy considered the point. "But, dash it! I could explain. I'm perfectly respectable really, and surely they'd understand it was a mistake—?"

She shook her head. "You must go. You are really in danger. I can't explain—but please—"

The last word conquered Timothy. He bowed with mock solemnity.

"Just as you say, lady..."

"Please," she pleaded again. "You must go at once. Hurry!"

"The trouble is, I can't," Timothy rejoined. "You see, I came in by an attic window, but I've twisted my arm. I can't get out again. And being as it were a stranger to the house—"

Her eyes were brown, he decided; dark, certainly, though the inadequate light of the candles made it hard to decide. They met his with a look of desperate appeal.

"There's a room—at the bottom of the stairs. On the left. The window is open. You can get out that way. If you're careful—" She broke off. "And don't—don't say you've been here!"

"Not a whisper." Timothy grinned reassuringly. "A window? Lead me to it!"

"I—I—" She hesitated. Apparently she took his last words literally. "We—we mustn't go together," she said. "If I go first—see if the way is clear— You will put out the candles, and wait—wait three minutes. If you don't hear anything—"

"Just as you like," Timothy assented cheerfully.

She was already moving towards the door. Then she was gone.

Timothy stared after her foolishly. What it was all about he could not see in the least. Watch in hand, he set himself to wait the appointed time. The first minute had almost ticked away when a sudden thought struck him.

"By George!" he said softly. "She's the real thing! And she's got away under my nose!"

Suspicion grew to a certainty. The girl had had no more right there than he had himself. In a sense even less. For she was a genuine burglar. She had come there to steal; she had rifled the desk under his nose—and got away.

Everything pointed towards it. At the thought he started for the door; then reconsidered it. He would stick to the agreement. Instead, he turned towards the candles, suddenly aware of the increased caution needed now that jest had turned into earnest. If he were found there now, and if things were actually missing, would anyone believe him? At the best he would have to give the girl away, and he felt an obstinate determination to do nothing of the kind. There was absolutely no time to waste.

She had seemed pretty confident—as witness her opening of the door with the candles lit. Presumably she had good reason for believing no one was likely to come that way. And yet—

He was in the very act of pinching the second candle when he saw the slip of paper. As the darkness came, he stooped and felt for it. Just what it was he could see later; it did not seem to be money. He stuffed it into his pocket, crossed the room towards the door, and opened it.

For a minute he stood on the threshold listening. There was no light or movement. Somewhere in the depths of the house the mellow bell of a grandfather's clock chimed the half-hour. Then all was quiet again. He was on the point of starting down the passage when a new sound made him pause.

Somewhere in the gloom ahead a door had slammed. It might have been quite accidental; but he half expected to hear the sound of a challenge—perhaps the girl's cry for help—the pursuit. But all was silent. Probably it had been the merest accident. He waited long enough to assure himself that nothing was happening, then set off noiselessly towards the stairs.

His experiences coming down from above had filled him with a distrust for staircases; but the one to the ground floor seemed to be an exception. There was hardly a creak as he descended, and the thick pile of the carpet deadened his footsteps perfectly. As he turned the corner a faint glow of light revealed the passage at the bottom; but everything was quiet enough. Very circumspectly he peered round the edge of the wall. The light came from a door which stood ajar some distance along, and the smell of cigar smoke drifted to him.

The door of which the girl had spoken was right beside him. If she had been right about the window, getting out would be simplicity itself. Then he glanced up quickly at a sound overhead. Someone was coming down the stairs. There was no time for hesitation. A couple of paces brought him to the door. He turned the handle quickly, and slipped inside.

Or rather, he had started to. He had expected the darkness of an unoccupied room; instead he stood blinking in a light which seemed positively dazzling. But blinded as he was by it, he could see well enough to make out the shape of the man who sat at the desk right in front of him.

Evidently the game was up. His retreat was cut off in all directions. There was nothing for it but to give in. If he tried to run it would only make things worse. He stepped into the room and started to stammer an apology.

"I'm sorry to—to burst in like this. The fact is—"

Suddenly he was aware of the complete motionlessness of the man at the desk. Was he asleep? His eyes were getting accustomed to the light. He must be asleep, or—? Surely the attitude was awkward? There was something wrong. He started forward, and as he did so his foot kicked against something hard. He glanced down. It was a small automatic pistol.

"Good God!"

He almost jumped across the room to the desk. The man in the chair made no movement. And the reason was plain. In the very centre of his forehead was a small, bluish hole, from which trickled a tiny stream of blood. Timothy bent over the desk in a kind of stunned horror. There was not a sign of life or movement. Then he jumped around. Behind him the half-open door was pushed wide.

"Bowmore! I say Bowmore—"

Timothy backed guiltily from the desk as the speaker entered.

FOR something like half a minute the newcomer stood staring from Timothy to the dead man. The expression on his face was less of fear or horror than of sheer amazement. He was a well-built man, fairly advanced in middle age, and the tan of his face contrasted strongly with the hair which was already whitening round the temples. But for the faultless evening dress, and an expression of superciliousness, almost arrogance, about his grey eyes, one might have placed him as a prosperous farmer or dealer; certainly he was a man used to living out of doors. So much Timothy noticed even in spite of the shock which held him motionless. For a moment he could only return the other's stare. With an effort he managed to speak.

"I say—" he hesitated, and to his own ears the tone sounded false and unnatural. "You don't think—? I can explain—"

The other made no answer in words. With a quick but unhurried movement he stepped forward and stooped. The next instant for the second time that night Timothy was looking into the muzzle of a gun. While he gazed at it stupidly it crossed his mind that in all probability it was the same one. Timothy broke an oppressive silence.

"Look here—" he began in a desperate attempt at explanation.

"Stay there," his captor interrupted briskly. "I think," he added it as though it was an afterthought, "perhaps you had better put up your hands?"

Timothy obeyed, not without some little pain. There seemed nothing else for it. If excuses had been difficult to find before to the legitimate occupants of the house, it was a thousand times worse now. The man behind the gun stood eyeing him speculatively, as though himself at a loss what to do. Then, still keeping Timothy covered, he stepped back towards the wall, felt for and pressed the bell.

"You can explain?" he said at last. The voice was that of a cultured man, and there was something sardonic in its tone. "If I might advise you, I should reserve explanations... Your presence here at all—"

He shrugged his shoulders and broke off. Footsteps were approaching along the passage, the measured, unexcited footsteps of someone who had no suspicion of the tableau inside the room. Timothy felt trapped. He had a wild, idiotic impulse to brave the gun and make a bolt for it. Then it was too late.

"Whitley." The man with the gun did not turn or take his eyes off Timothy. "I'm afraid Mr. Manningtree has been shot. If you would call the police—"

"Good—good God! Fareham—!"

The eyebrows of Timothy's captor rose slightly. For a single instant he glanced at the new arrival who was standing in horrified amazement in the doorway; then his eyes returned to Timothy.

"Oh, it's you, Bowmore," he said without emotion. "Perhaps you would be good enough—"

"But what—what happened? He didn't— It wasn't—suicide?"

The man addressed as Fareham lowered his eyes for a moment towards the still figure in the chair.

"No," he said deliberately. "It wasn't suicide. Nor, I should imagine, accident. But this young gentleman says that he can explain everything."

In spite of the threat of the gun Timothy lowered his arms, and faced the two men. Like Fareham, the man called Bowmore was in evening dress; but he wore it awkwardly, like a man not too used to it, and even more in his voice and carriage than in the highly coloured face there was something that suggested the self-made man. In contrast to the emotionless calm of Fareham, his eyes were almost starting from his head, and there was a whitish look about his lips.

"Look here," Timothy began again, "I don't know anything about—about this. I found him like that when I came in. I meant I could explain how I came to be here at all."

Fareham had not lowered the gun; but he had made no gesture when Timothy moved.

"Yes?" he prompted courteously. "You can explain that?"

"It was a joke—a silly bet," Timothy began; but the arrival of the servant whom the bell had summoned interrupted him.

"Whitley," Fareham repeated in almost the identical tone and words, "Mr. Manningtree has been shot. If you would call the police—"

Timothy heard the butler gasp. In spite of the seriousness of the situation the thought crossed his mind that it was a scene to shake even the best-trained servant.

"Yes—yes, sir," Whitley managed to reply with an effort, and his voice only shook a little. "The police, sir—"

"See that none of the servants leaves the house," Fareham went on equably. "And if you have a key to this room—"

"It—it's in the door, sir," Whitley said, and extracted it from the inner side of the keyhole. "No one is to leave, sir?"

"Or communicate in any way with outside. You need not tell them what has happened. The police first."

Still without looking away from Timothy, he extended his hand for the key. With a scared glance at the dead man in the chair the butler went out. For a moment there was a pause, in which they could hear his footsteps receding down the passage.

"And now, Bowmore," Fareham suggested. "If you'd go first. Then you, Mr.— I haven't the pleasure of knowing your name?"

"Wynne," Timothy managed to say, and wondered whether he should have done so. "I say—"

"Wynne? Not the Herefordshire—" Fareham seemed to realise it was no time for genealogical discussions. He broke off. "If you would go next, Mr. Wynne. I will come last."

He did not say "with the gun," but he conveyed it with a slight motion of the weapon.

"But—but, Fareham—we can't leave him!" Bowmore protested.

"It's exactly what we should do. We must leave things as little disturbed as possible."

"But—but is he dead? You're sure—?"

"I should say that there was no doubt of it. Perhaps Mr. Wynne can tell us?"

"Yes," Timothy answered before he thought. "That is, I'm almost sure. I was just looking—"

Fareham inclined his head. "The position of the wound leaves no doubt," he said calmly. "And now— To the lounge, I think, Bowmore."

Bowmore turned helplessly to lead the procession, not without a nervous glance back. The key clicked in the lock behind them. Again Timothy had the impulse to run for it. There was something in Fareham's emotionless attitude which was horribly unnerving. But the gun was just behind, and he had no doubt that its holder would use it without compunction. Besides, they had his name. It would only make things worse.

Almost at the top of the passage Bowmore turned into a doorway on the right. It was a long, low room, comfortably furnished in excellent taste; though here the conversion of the old farmhouse was more apparent. Two doors gave out of it, besides the one by which they had entered, and at one time it had obviously been two smaller and separate rooms.

Fareham closed the door behind them and glanced around.

"Doune?" he asked. "I thought he was here?"

"He said something about seeing Royton," Bowmore answered. "In the office. Shall I get him?"

"Better get both. My daughter is upstairs, of course. There is no need to disturb her at the moment."

As Bowmore went out by one of the two doors at the far end of the room, Fareham motioned Timothy to a chair.

"The police will be here shortly, Mr. Wynne," he said, and moved towards a table near the fireplace. The gun was still in his hand, but he seemed to have lost some of his watchfulness. "You might be well advised to say nothing until they arrive. Still, if you care to explain—"

Timothy hesitated. After all, he had nothing to hide. It was hard to see how he could make things worse. And he felt the need of talking to someone.

"It—it sounds pretty silly," he began lamely. "I hardly know how to start."

"You'd like a drink?" Fareham had been busying himself with the glasses. "Soda?"

Timothy shook his head, but accepted the neat whisky and gulped it. That seemed to make things better.

"It was just as I said," he plunged after an uncomfortable pause. "You see—there was a dinner—a sort of anniversary celebration—"

"An anniversary?" Fareham queried politely.

"Of a kind." Timothy grinned sheepishly. "It's just four years since I was sent down from Oxford for climbing the Martyrs' Memorial. You see, it sort of ran in the family. I happened to meet a few friends down here—chaps who'd been there at the time. So we celebrated."

"Naturally," Fareham assented gravely.

"I don't quite know how it came up," Timothy confessed. "But we were having a discussion on cat-burgling. George said I should never have made a cat-burglar. Somehow it ended in a bet. I was to burgle his uncle's house—not really burgle, you know, but just break in and take something to show I'd been there. So I did. You see, I thought this was his uncle's. Perhaps George got the directions a bit mixed—"

"George?" Fareham inquired.

"The man I made the bet with. That's George Petworth."

"Our neighbours?" Fareham inclined his head. "Perhaps, as you say, he got the directions mixed. Or perhaps—"

He did not go into the other possibility, but looked at Timothy as if to encourage him to proceed.

"You mean—" A sudden light flashed on Timothy. "You think it might all have been some silly joke on his part? That he meant to send me here?"

"It might even have been that. Yes, Mr. Wynne?"

"So I got in. Through an upper window. Wrenched my arm a bit and went to the bedroom George said was his—at the end of the passage—"

"The left branch?" Fareham frowned as Timothy nodded assent. "That was Manningtree's own room," he explained, and thought for a moment. "And you took something as evidence?"

"Oh, yes. This."

Timothy produced the ash-tray from his pocket. But something else came with it. It was the slip of paper which he had retrieved from the floor where the girl had dropped it. It brought him up all of a sudden. What was he to say? The girl had been there in Manningtree's room, searching in Manningtree's drawers. She had held him up with a gun—probably the very gun which Fareham was holding at that moment. Then he half jumped to his feet. The door slamming—just when she had gone downstairs. It had not been the door at all. It had been— Fareham's quiet voice broke in on his thoughts.

"Ah, the ash-tray?" he said. "Yes. I recognise it. And this?"

He stooped and retrieved the folded slip of paper. He opened it, and his eyebrows rose.

"And this," he repeated with decision, and this time it was a statement.

"And that," Timothy admitted, "I picked up off the floor. What is it?"

Fareham flipped it open with his finger and extended it. Then Timothy saw that it was a cheque. The bend of one end of the paper hid the amount, but at the righthand bottom corner he could see the signature, C. Manningtree.

"A cheque," Fareham explained unnecessarily. "A cancelled cheque. You found that too—in the bedroom?"

Timothy nodded. He hoped that his face did not show his feelings for he was thinking furiously. The girl had taken from the drawer a little bundle of slips like that. And there had been the gun, and her leaving so hastily just at that minute and the shot. But she could not have done it. Presumably she was Fareham's daughter. Abruptly he decided, without quite knowing why, to say nothing about her. All at once he was aware that Fareham's eyes were upon him.

"Yes, Mr. Wynne," he said softly. "You picked that up on the floor of the bedroom. There's nothing wrong?"

Timothy shook his head. "It was just before I went out," he said with an effort. "Then I came downstairs. You see, I'd hoped to be able to find some way of leaving the house. But there didn't seem to be any. I saw the light under Mr.—Mr. Manningtree's door, and I thought I'd give it up as a bad job. I went in to tell him. And he was sitting there and didn't answer. I saw the gun on the floor. Then I went round to see—and you came in."

"The gun?" Fareham frowned at it. "No doubt I should have left it there for the police. As it is— Here they come."

Timothy followed the direction of his glance towards the top end of the room. Bowmore had re-entered, followed by a young, bespectacled man of impeccably neat appearance to whom Timothy took a dislike on sight. Presumably, he thought, that must be Doune; but Bowmore's first words undeceived him.

"Royton says that Doune never came," he said with a trace of bewilderment in his voice. "He hasn't seen him at all."

He glanced at the bespectacled young man for confirmation. Royton nodded.

"That is so, Mr. Fareham," he said, and his voice exactly fitted his manner. "I have been alone in the office for the past hour. Is anything wrong?"

Fareham glanced quickly at Bowmore, who shook his head. It seemed that he had not told the young man the news, and Timothy found himself wondering why. But Fareham gave an imperceptible nod of approval. Royton looked curiously at Timothy; then glanced around the room.

"Mr. Manningtree?" he asked. "I was to go to him after you had seen him, sir. He's in his study?"

"Yes," Fareham agreed. "He's in his study. But I'm afraid you can't see him just now, Mr. Royton. You see—" He broke off, and his eyes were on the other's face.

"But Mr. Manningtree said—" Royton began with a trace of doggedness in his voice. "He particularly wanted to see me, sir—after Mr. Bowmore had gone."

"He can't see you, Royton," Fareham said quite calmly; then added in a tone which did not change in the least, "You see, he's been shot."

"Shot?" Royton's face was not well equipped for showing the more violent emotions. He merely blinked at the first blunt statement; then his eyes almost popped from his head, and his mouth opened in a way which vaguely suggested a codfish. "You mean—you don't mean he's dead? Not—not murdered?"

His voice rose on the last word. Fareham's steady eyes were fixed on him curiously. He nodded.

"Yes," he assented. "We've sent for the police."

"Then—then he was right!" Royton almost squeaked. "He said—he said—the letters—"

Fareham's eyebrows rose perceptibly. "He told you?" he demanded. "He expected—something?"

"He did, I'm sure he did. But I never believed— It was just after Doune left—" He broke off abruptly and drew a deep breath. Something of his normal precise air came back to him. "But—but we'd better not discuss it, had we?" he said after a pause. "The police—"

"A very proper view," Fareham assented. "But, by the way, where is Doune?"

He glanced at Bowmore, who coloured as though he had been accused of something.

"I left him here," he said. "I mean in the card-room." He jerked his head towards the second door: "When I was going to see Manningtree—after the wine was spilt—"

"That would be about twenty-past eleven?" Fareham suggested. "And your appointment was for half-past? It is now a quarter to twelve—"

It seemed to Timothy as though for some reason Bowmore did not relish this analysis of the position.

"He was there then," he said firmly. "Just pouring himself out some more port—though he'd had enough already. He said he was going to see Royton in the office about something."

"He did not come, sir," Royton said firmly. "I have been there all the time—"

"You're sure he's not in the card-room?" Fareham suggested. "He might have fallen asleep."

There was a suggestion of contempt in the last words. Timothy had risen to his feet. He caught Fareham's eye.

"Perhaps you would come with us, Mr.—Mr. Wynne," he suggested. "We had better keep together for the present."

That, Timothy thought, was a delicate way of putting it. He preceded Fareham obediently up the room, leaving Royton and Bowmore to bring up the rear.

Fareham halted in the doorway and looked around. "He's not here," he said, and there was a puzzled note in his voice. "But I don't quite see— What's that?"

A sharp click had broken in on his words. Then the curtains hiding the long French window at the far end of the room billowed suddenly as the casement opened. A young man staggered into the room and stood blinking foolishly in the light. He had obviously been drinking, and he stared stupidly at the group in the doorway. Timothy was conscious of a dim suspicion that he had seen him somewhere before.

"Doune!" Fareham said sharply. "You've been out?"

Doune scowled angrily; but he hesitated before he answered.

"How the hell should I come in if I hadn't?" he demanded a little thickly. "Why shouldn't I?"

"Why not, indeed?" Fareham echoed; then his voice changed. "You don't know any reason?" he asked sharply. "Sure?"

"I don't know what the devil you're blithering about!" Doune retorted fiercely. Timothy judged that his temper was never of the best and he had certainly drunk more than was good for him. "And let me tell you, I'll not be spied upon! If anyone tries to follow me—"

"I don't follow you in the least," Fareham interposed suavely. "You mean someone was following you outside? I can assure you that none of us have left the house. You saw someone?"

"There was someone out there just now." Doune lurched towards the window and pointed. "Over there—"

The four of them peered over his shoulders. The moon was just rising, and it was possible to distinguish the far side of the lawn where the black mass of the shrubbery bounded it.

"What were you doing over there?" Fareham asked suddenly. "I have a—"

"There!" Timothy pushed past them excitedly. "Did you see—"

Before anyone could stop him he had jumped through the window and was running across the grass. Behind him he heard Fareham's voice raised threateningly.

"Come back! Stop! Stop! Or—"

Whatever the unspoken threat might have been, Timothy did not heed it. It was only when he was half-way across the lawn that he remembered the gun in Fareham's hand. In his mind there had been no thought of escape. Obviously that would be worse than useless. But just for an instant on the edge of the shrubbery he had had a glimpse of something moving, and the merest impulse had taken him in pursuit. As he ran a thought flashed across his mind. It might be the girl. And if it were—? He did not know what to do. There was a dim idea in his mind that somehow he might hold off the pursuit long enough for her to escape. He could hear the feet of the others thudding behind him. Then, in front, he heard something else, the crackle of the bushes as though someone were pushing through. There was no light to pick or choose a way. He plunged into the shrubbery anyhow, struggled through a mass of small twigs and branches, and unexpectedly found himself on an open pathway.

In his excitement he seemed to have overrun the mark. The unknown, whoever it might be, was still struggling in the trees. Timothy turned and started up the path in the direction of the sound. For a moment the noise ceased. He could hear the others shouting on the lawn. All at once, almost on top of him a dark figure emerged from the shadows. He closed in a flying tackle, and both went headlong.

Certainly it was not the girl. He had seen so much before he leaped, and in any case he would certainly have known it. His opponent was a man very much of his own size and weight, and in spite of the surprise of Timothy's attack, he fought back fiercely. Timothy got home one blow on the other's nose, only to receive himself one just as good under the ear. He felt his grip weakening.

Then lights were flashing upon them, and he was seized by the shoulders and dragged back.

Someone shone a torch in his face. He saw that he was in the grip of a burly man who was a complete stranger to him. Then the glimpse of a uniform explained what had happened. The police had arrived.

"That's Wynne," Fareham's voice announced. "And the other?"

His late opponent had risen to a sitting position. He was mopping at his face with his handkerchief, and the blood from the wounded nose made him hard to identify. With a sudden start Timothy realised who it was.

"Good heavens!" He peered down at the other's face. "George! It's you?"

His friend looked up savagely. "You?" he said. "You here? What—? You damned fool!"

NINE o'clock was just striking when Inspector Richard Hayle stepped out of the French window on to the terrace and reached for his pipe. Although he had contrived to maintain an outward calm and an official woodenness of feature he had been feeling his responsibilities acutely. Murders in that part were rare; since his recent promotion there had been none at all. Now he had suddenly found himself in charge of one, and, with the Superintendent confined to his bed with influenza, there was a fair chance that he would remain so.

Everything depended on the Chief Constable. Colonel Chedder was a man of impulse. He might decide to hand the case immediately to Scotland Yard; he might equally well sneer at Londoners in general and praise the county police. The first impression was all-important, and that was why Hayle had worked all night without a break. At that moment, with the Chief Constable due to arrive any moment from his interrupted holiday, he could only pray he had done enough.

It was true there was no arrest in sight. He might have detained Timothy Wynne as an obvious suspect, and the one person whose mere presence was unauthorised and extraordinary. But the more he had gone into things, the less he was inclined to think of the appearance of the young man as anything but an accident, and it was a comforting thought that perhaps the murderer would find it even more embarrassing than the police. For the present, unless the impulsive colonel ordered his arrest out of hand, Timothy was released on parole; with the possibility of a charge of housebreaking at least if he misbehaved.

Lighting his pipe the Inspector strolled down the path towards the end of the garden. From there he could command a view of the drive by which the Chief Constable must approach, and of most of the rest of the surrounding country. He had never been to the house before, and he found comfort in excusing himself for his brief respite by the need for getting an idea of the locality. From the lower wall, where the land fell away sharply by way of two or three rough fields to the tangled valley bottom where the stream ran, he could command a view of everything which at that moment appeared to have any relevance to the murder.

Directly opposite was Three Gables. Situated on different sides of the V-shaped indentation in the hills, the two houses were approached by drives which sidled up the hillside, leaving at right angles the lane from the village which, after proceeding for another hundred yards, faded imperceptibly and without apparent reason into the grassy track leading to the disused china-clay pit at the head of the valley. Except for the squat tower of the village church, which just contrived to peer over the trees hiding the village, there was not another house in sight.

But there were signs where one might have been. A gash of raw earth in the brown of the hillside and the harsh red of new bricks indicated the foundations of an extensive building. Hayle had already heard about that. It was where Manningtree had intended to build his new house, and he had chosen the site well. As it was, it would probably never be built. Hayle found the thought depressing. Perhaps his own weariness made him see in it a commentary on the vanity of human wishes. Probably Manningtree had all his life wanted a house in just such a spot; and now he was dead.

His eyes were still on the place where the house might have been when his attention was attracted by something on the hillside immediately above it. It came from a clump of bushes part-way up the slope, and at first glimpse he almost dismissed it as the twinkling of the sunlight on a piece of broken glass. Quite suddenly he noticed something peculiar. There was a regularity about the twinkles. The pin point of light came and went among the bushes at fixed intervals. Obviously it was deliberate. It came across his mind that someone was signalling, probably with a small mirror, and he began to read the flashes so far as his very limited knowledge of the morse code allowed.

"Dot-dot-dot... Dot-dot-dot... Dot-dot-dot..."

"S—S—S—" he translated mentally as the sign was repeated. "S—S—S—"

For two or three minutes there was nothing else. It occurred to him that he might have misread it. "S.O.S." was, he knew, a call for help. Had he misunderstood the second group as dots instead of dashes? A minute later the repetition of the sign put the matter beyond doubt. It was simply the repetition of three S signs.

It might be some code. He could remember only about half the morse alphabet, and yet it might be vital to know the message. In the following pause, he felt for a pencil and paper to take down whatever might be flashed, thankful that whoever was sending it was doing so slowly enough for the veriest amateur to follow without trouble. Abruptly he wondered to whom the message was being sent. To someone in the house? He looked back. A screen of bushes hid everything except for the roof. He remembered that even from the terrace one could not see the site of Manningtree's house; but one might from the upper windows. He looked back hurriedly, just in time to catch the end of the next signal.

"Dot-dot-dot—"

But this time it seemed as though there had been an answer to the calling signal. A succession of other letters followed. Some of them he knew, and some he did not; but he duly noted them. Then again came the "S.S.S." and here it must have been a signature. No more flashes came. Apparently the message had ended.

For some time he kept his eyes fixed on the clump of bushes. Whoever it was who had signalled would presumably be leaving. But there was no sign of it. From where he stood, it seemed to be a bare, green hillside; but the very colour gave him the clue to what had probably happened. The moor grass was brown; the green was bracken. What at that distance seemed a space devoid of cover was probably covered by the fronds three or four feet deep. It would have been easy enough for anyone to have crept away unobserved. After a while he gave it up.

Only momentarily the idea occurred to him of trying to give chase. But that would be hopeless. He would have to appear in full view on the bare slope below the garden; he could never get anywhere near without giving the alarm. Instead, he turned his attention to the message.

There was little enough he could decipher. First the three S signs. Then two dots. That was "I" and apparently used as a word by itself. "Four dots—H... dot-dash—A; then a sign he did not know; then a solitary dot. But jotting down those which were intelligible he achieved a kind of result.

"S.S.S... I... HA-E... THEM... E-E-EN... S.S.S."

He frowned down at the notebook. Of course he could easily get the other letters interpreted; but it should be possible to make something of that in any case. The sound of a car coming up the hill made his thoughts break off abruptly. That would be the Chief Constable, and for the next half hour or so he must concentrate on making himself as brisk, capable and competent as he could. Shutting the book, he started to hurry back up the path. He had nearly reached the top when it came to him quite suddenly.

"By George!" he exclaimed under his breath. "S.S.S... I have them... Eleven... S.S.S.!"

He had not a doubt that that was the correct reading. What it meant was another matter. Who was the message intended for? Did the sender know what had happened? Had it anything to do with the case? For the moment he had to leave those questions unanswered. The car was just drawing up at the door when he reached the drive.

Luck was on Hayle's side. It was true that Colonel Chedder had been roused from his bed in the small hours, and his tone at that time had augured the worst. But he had had to drive some distance. After an hour or two of irritation, the early morning air had produced its effect, and by good fortune the Colonel had been able to get breakfast en route. He jumped quite lightly from the car, for a man of his build, and beamed with a cheerfulness which was almost indecent on the Inspector as he hurried up.

"Morning, Hayle. Lovely morning. Everything all right? Got him yet? It's that young Wynne, I suppose?"

That was just what the Inspector had feared he might suppose; but he did not venture a contradiction.

"Well, sir," he said. "I've not arrested him yet. The fact is, sir, I think there may be complications. I might explain—"

"Complications, h'm? The Colonel frowned. "Clear case, I should have thought. Manningtree catches the young fool—holds him up. There's a struggle. Wynne gets the gun, loses his head and shoots him. Eh?"

"That's certainly possible, sir. But there are objections. Perhaps if you could see the room—"

"View the body first, eh? Good plan. Right. Lead on—"

On Hayle's instructions, not even the body had been moved until the Chief Constable's arrival; or at least, no more than had been necessary for the doctor to make a preliminary examination. But the Colonel was not depressed by it; if anything he eyed it with pleased interest.

"Queer thing," he commented. "Rank outsider, that chap. Started life in a chip-shop. But judging by the look of him you'd think he came of a decent family. Whereas old Fareham, whose ancestors came over with William the Conqueror, looks like a horse-dealer."

However heartless it might be, there was justice in the remark. Perhaps death had added dignity to Manningtree's face; but even in life it must have been finely featured and of a type which most people would associate with aristocracy. But Hayle was not interested in natural contradictions at that moment.

"You knew them then, sir?" he asked.

"Manningtree? Hardly. Made of cash—nothing else about him. Hardly knew which fork to eat with. Always trying to suck up to people. I suppose that's how he picked on Fareham. Quite the other way there. Blood without money."

The Colonel was obviously pleased with his epigram. Hayle nodded.

"I understood so, sir. That's how Fareham came to let the house to him. You see, Manningtree was going to build a house of his own just up the valley. They'd started the foundations. He wanted to be here to supervise—"

"Heard about that. Who are all this other crowd—Beaumont or whatever his name is?"

"I understand he's a business acquaintance, sir. He'd come down to discuss some kind of a deal. Royton was the secretary, and Doune was a sort of protégé of Manningtree's, training for the business. You see, he'd no son—"

"No. Separated from his wife. I saw her once. A bit loud, but a dashed good-looking woman for her age... That can wait. Look round here first, eh? Everything as it was?"

"Except the gun, sir. Fareham picked that up when he captured Wynne. I chalked a mark on the floor—here—to show where it seems to have been."

"Dashed silly thing to do. Ought to have known better."

"Perhaps, sir. But I suppose he thought he'd surprised a murderer on the scene of his crime—and Wynne's six foot, and pretty hefty. I don't blame him—"

The Colonel was not listening. He was frowning fiercely around the room.

"Not suicide, eh?" he demanded.

"Out of the question, sir. For one thing, the gun couldn't have fallen that distance away. Then there's no mark of burning on the skin. The doctor said that the shot must have been fired from about five or six feet at least. The bullet entered the forehead quite straight, and death must have been instantaneous."

"Five or six feet? From somewhere near the door, then."

"Perhaps, sir. But Dr. Gibson wouldn't say definitely. His point was that the man's head might have been at any angle, and turned in any direction. The impact of the bullet might throw it back against the chair. We can't quite say, sir."

"Gibson's a fool. Pretty obvious I should say. Looks bad for young Wynne. Might be manslaughter, though?"

"That's a question, sir. If it were, it's hard to see how it happened. You see, supposing there had been some kind of a struggle, would it be reasonable for Manningtree to have sat down at his desk again as though nothing had happened? He'd have jumped up when Wynne came in anyhow; but he certainly wouldn't have been sitting like that if Wynne had snatched the gun from him."

"H'm... No. Maybe not. But it's Manningtree's gun?"

"I'm trying to establish that. It has his initials on it, but no one seems to have known he had one. Of course, we can probably trace it."

"Where is it?"

"I've got it locked up in the card-room, sir. If we went along there afterwards, I could explain the position better."

"Right." Chedder glanced around the room again. "Nothing else to see here?"

"Nothing, sir. No one seems to have left a trace. There's only one thing. You'll see the window was open. That may be important."

Colonel Chedder was by no means a fool. He glanced at Hayle sharply.

"Doune, eh?" he demanded. "You've got your eye on him?"

"Among others, sir. Certainly his conduct's a bit queer."

"Better tell me all about it. Nothing more here? Come along."

Either Fareham or Fareham's butler had had the good sense to provide a tray containing whisky and soda in the card-room. It was two hours before the Colonel's normal time, but he helped himself. The occasion was exceptional. He looked at Hayle.

"Drink, Inspector?" he asked.

"No, thank you, sir."

"Smoke if you care to. Now, let's talk it over comfortably."

Hayle obediently seated himself in the armchair his superior indicated and produced his notebook, and a small sheaf of reports which he handed over.

"Well, sir, these are what I've got so far," he began a little hesitantly. "You know the general position. Fareham had let this house to Manningtree furnished—except for a few things of his own Manningtree brought along. He and his daughter were staying on until Manningtree was a little settled. The housekeeper who had been hired wasn't available, and Miss Fareham was still in charge of the house. The servants were the same, except for a sort of chauffeur fellow who lodges at the cottage down below. Fareham and his daughter were leaving at the end of next week."

Colonel Chedder nodded. "That's plain enough. Right," he said.

"Bowmore came down the day before yesterday—Wednesday, that is. Exactly what his business was, I can't quite make out. Royton knows nothing of it. He says that Manningtree was considering buying some shares. Doune came on the Thursday night for a long weekend. I understand that that was to fix up the place he was to occupy in Manningtree's business. You see, until lately he'd been acting as a sort of secretary. Royton has only been with him a month. Without counting the servants, that accounts for everyone in the house."

"Servants trustworthy?"

"I understand they've been with Mr. Fareham for some time, sir. Besides, since Manningtree's only been here a fortnight, it isn't likely any of them would have any motive."

The Chief Constable shook his head in reproof. "Can't be sure," he said. "Doesn't do."

"I'm not overlooking them, sir. Though most of them have alibis. Perhaps I'd better just explain in detail what happened that night. Dinner seems to have been as usual. Almost immediately afterwards Miss Fareham went to bed with a headache."

"H'm? Nothing wrong with that? Why shouldn't she?"

"No reason, sir. But it was unusual. She wasn't subject to headaches. On the particular night of the murder she had one, went to bed and wasn't seen again until her father went up to see her."

"No alibi, eh?"

"No, sir. Afterwards the four of them—Manningtree, Fareham, Doune and Bowmore—sat down to a game of bridge. Royton went to the office to work."

"Work, eh? Pretty late?"

"That seems to have been fairly normal. When Mr. Manningtree had anything special on, he didn't spare himself or anyone else. But even when things were busiest, he'd take an hour off for a game of bridge—though he preferred whist—"

Chedder snorted. "Whist, eh? He would."

"At half-past ten Manningtree himself went to the study to work. He'd fixed an appointment with Bowmore for half-past eleven. And, I think, that was a little odd, sir. Bowmore's been there two days and they've hardly had a word together so far as one can make out. Then on the night Manningtree's killed, they are just going to discuss business at half-past eleven at night."

The Chief Constable frowned and nodded assent.

"The other three settled down to a game of dummy. Doune was winning; but he was drinking heavily. The game ends when he manages to knock a decanter of port over. Most of it went on Fareham's trousers and he went up to change them."

There seemed to be something significant in Hayle's pause, but the Colonel failed to grasp it.

"Nothing wrong with that?" he suggested. "Sensible thing to do."

"Perhaps. On the other hand, it was so late that Fareham might reasonably have decided to go to bed. But he does change his trousers. The butler takes the others to clean them, and generally looks after things. That was just after a quarter-past eleven."

"If Whitley was there, Fareham had an alibi?"

"I'm not sure how complete, sir. I'm going into it. Doune says he's going to see Royton. And in the ordinary way he can't stand Royton. In any case he doesn't go. Apparently he wanders out into the garden for half an hour, and comes back after everything is over saying people are spying on him. His explanation is that he wasn't feeling well and thought the fresh air would buck him up."

"Just as likely to bowl him right over."

"Yes, sir. But he's no alibi. The window was open. He might have shot Manningtree through the window. And at last we come to Bowmore. When he left Doune, he said he was going to see Manningtree. That was at about twenty-five minutes past. But though it wouldn't take him two minutes to get to the study, he only arrives after Fareham has held up Wynne—or at about twenty-five minutes to twelve. What was he doing in the interval?"

"If he'd not been to the study—" Chedder began hazily.

"The point is, sir, he might have been, shot Manningtree and come back. Both Wynne and the butler heard the shot at about half-past eleven—though both of them thought it was a door slamming."

"No one else? That's odd."

"It is in a way. They were upstairs, and I suspect the sound came through the window. And in the end, sir, none of them had an alibi except Fareham, and all had acted strangely."

"H'm... Four. Five counting the girl. And that's your list of suspects? If you've ruled out Wynne—"

"I haven't, sir. I've ruled out his shooting Manningtree accidentally. He might have some motive we don't know of."

"Good God!" the Colonel said rather heavily.

"And still less have I ruled out George Petworth," Hayle said grimly. "Because he might have engineered Wynne's mistake to suit himself."

"He guessed Wynne had made a mistake and came to look."

"That's what he says this morning... But he didn't last night. He gave no intelligible explanation at all, except that he'd made a mistake."

Colonel Chedder considered. "Plenty of choice, eh?" he said at last. "It's a question of pinning it down to one of 'em... You'll have plenty to do, Hayle."

Hayle flushed a little. "Then you weren't thinking of calling in the Yard, sir?" he asked. "Last night you mentioned—"

"Yard? What do we want with them? You feel equal to it, eh?"

"I hope so, sir."

"Got all the men you want? Right. Then you'd better carry on. Got any line to work on?"

"I think so, sir." Hayle had suddenly remembered the morse message. He hesitated for a moment; then decided not to reveal it just then. "In fact, there's plenty, sir—"

Colonel Chedder rose. "I'll have a look round myself," he said firmly. "No. You needn't come. I'd just like to have a chat with one or two of 'em. Nothing like seeing them yourself... See you later—"

It was with mixed feelings that Hayle watched his departure. It was true that he had gained his main point and was to be left in charge. On the other hand, he had scarcely counted on the active co-operation of the Chief Constable, and rather dreaded the effect that his superior's over-blunt questions and elephantine diplomacy might have on any suspect. With a sigh he moved towards the French window and went out into the garden.

He had walked to the end of the terrace before he had quite satisfied himself that from no point upon it could one see the clump of bushes from which he had seen the signals an hour earlier. That seemed to leave only the upper windows. There were three which were likely, and one possible—Doune's, Fareham's and his daughter's. So far as he could see, any of them might have been on the look-out. He would have to try to find out where they were at the time. But the possibility made things even worse. It was the bathroom window, and as such available to anyone.

Stepping back into the shade of a laurestinus bush on the terrace edge, he scrutinised the front of the house. Of the three, Fareham's perhaps provided the best view.

Suddenly he was aware of someone coming towards him along the terrace. Mere instinct made him back into the bush, and he peered through the branches carefully. It was Doune. He was walking quickly, like a man with some definite object in view, glancing back from time to time as though to see if anyone was following. He disappeared down the steps at the far end, and Hayle heard the clicking of a gate latch.

He glanced at his watch. It was a quarter to eleven, and the Chief Constable had said an hour. Probably he would be quite happy for even longer. He hesitated. Not to be available when the Colonel wanted him might easily ruin everything. Suddenly an idea flashed through his mind. Eleven! It had not referred to "them" whatever they might have been. It had been an appointment for that time; and Doune was going to keep it at that moment.

Hayle did not hesitate. Waiting for a minute until his quarry should have a fair start, he was on the very point of following when the sound of footsteps on the pavement made him turn quickly. Someone else was coming along the terrace, and this time there was no mistaking the light, quick footsteps. It was a woman. He parted the boughs cautiously and looked through. Winifred Fareham was hurrying towards him.

ON the whole, Timothy was inclined to regard the events of the night in a philosophic spirit. His apprehension by the police and his conditional release appeared in retrospect to be stimulating rather than otherwise. The Inspector had been quite decent. He had not even been disposed to raise the question of housebreaking, much less to query Timothy's version of what had happened in Manningtree's room. So that, on being told he was free to go but must remain available, Timothy had adjourned quite cheerfully to the inn, wired for the rest of his luggage, and after an early breakfast gone to bed.

Except for the stiffness of his left arm, he was completely himself again when he awoke four hours later. It was a beautiful morning, sunny and just pleasantly warm; and having ascertained from the landlord that there had been no messages or inquiries for him, he ordered a pint of beer, and sat on the verandah sipping it while he considered his further action.

Two things rankled. First, there was George's inexplicable conduct. Admittedly he had been hit on the nose; but that had been an error, and might have happened to anyone. It was no reason for behaving like a bear with a sore head, utterly refusing conversation, and, when he was released some time before Timothy, disappearing without a word to say where he was going. If anything, Timothy felt that the grievance had been on his side. It had been George's idiotic direction which had caused him to be involved in the affair at all. Thinking it over, Timothy felt that George owed him an explanation, and he was determined to get one.

Then there was the girl. The more he thought about her, the more puzzled he became. Presumably she was the daughter of whom Fareham had spoken. In that case his first impression had been wrong, and her presence in the house legitimate. Even so, what was she doing in Manningtree's bedroom, ransacking Manningtree's drawers? What did she want with the cheques, and how had she come to be carrying the gun?

Timothy frowned at his beer mug. There might be some reasonable story to account for all that, but what lingered in his mind unpleasantly was her treatment of himself. Pretending to help him get away, she had deliberately sent him into danger.

Timothy thought that over; then without very much reason rejected it utterly. Whatever she might be, the girl was not a murderess. Unless she had been utterly desperate, she could not have killed Manningtree. Except by accident? In any case he must see her. The question was just how?

He thought it over carefully. Again the answer seemed to be that he must see George. George was a neighbour of the Farehams. He probably knew her, and could arrange some kind of an interview. In that case, the first thing to do was to find him. Since he was not at the inn, in all probability he had gone to his uncle's. At least he would go there first. He finished his beer and was on the point of starting when another thought struck him.

Perhaps Inspector Hayle had not been so guileless as he had looked. It was a common police dodge to release people and have them watched. Someone might be shadowing him, at that moment. He looked around the verandah. There were three other guests on it when he arrived, and he had paid little enough attention to them. One was a pretty, quiet-looking girl with brown hair and pleasant blue eyes who sat knitting just to the left of the doorway. She seemed harmless enough. And yet, even as he decided that she was, she looked up covertly, dropping her eyes quickly as they met his. She had been watching him. But then, she was certainly not a police woman. Probably everyone in the inn was curious about him for that matter.

He turned his attention to the other two, and as he did so he was aware that their eyes dropped hastily. They were not merely looking at him but were talking about him. He was sure of that. And in any case, he was not favourably impressed. The man was thin, dark, delicate-looking and very pale—rather a weed, in fact, Timothy decided. And he was certainly nervous. He seemed to have difficulty in keeping still.

The woman might have been pale too. One had no chance to judge. She was pretty enough, though heavily made up; but of a type which had always scared Timothy thoroughly. There was a confidence in her manner which was almost boldness. And just when he had decided that, whatever she might have been, she too could hardly be a police spy, she looked up quite deliberately, smiled at him and then rose to her feet.

Timothy felt completely taken aback. He sat and stared at her as she crossed the verandah towards him.

"Good morning." She smiled quite pleasantly as he rose to his feet. "Haven't I met you before? I'm afraid I've forgotten your name. I'm so stupid that way—"

"Wynne," Timothy supplied automatically; then floundered. "I don't think I remember—"

"Wynne?" She echoed the name, and the faintest pucker of a frown appeared. "Didn't I meet you at Oxford?"

The words decided Timothy, but in a way she could not have expected. For a moment he had actually thought he might have met her somewhere; but not at Oxford. His existence there had been riotous occasionally, but strictly celibate. The idea that he could conceivably have met anyone of that type there was absurd. She was trying to scrape an acquaintance with him.

"I don't think—" he began, paused, then plunged rudely. "No. I'm sure there's some mistake."

"Oh, I'm so sorry." Her words were apologetic, though she had raised her eyebrows a little at his tone. For a moment a calculating look showed on her face; then she smiled frankly. "You're quite right," she confessed. "We haven't met before... The truth is I was curious."

Timothy could think of nothing to say. He simply stared.

"Oh?" he said at last

"It was you—wasn't it? Up at the house last night? Everyone is saying so. I wondered. Is it true? Cha—Mr. Manningtree. He—he's dead?"

Just what the emotion was which made her last words falter Timothy could not decide. Her eyes were fixed upon his face, and it seemed to him that they burned with a fierce eagerness.

"I think I'd better not say anything," Timothy managed to say after a long pause. "The police—"

"But it is true? It's really true that he's dead?"

"Well, I suppose I can say that," Timothy admitted hesitantly. "He's dead."

Her expression changed suddenly. All at once her face was an enigmatic mask. Then she smiled.

"I suppose you think my asking is perfectly dreadful," she said sweetly. "But I couldn't help it. Thank you so much."

Timothy had no words to answer as she turned away. All at once he was aware that the quiet-looking girl had been an interested spectator, and probably a listener. He flushed furiously, and it was more with the idea of escape than of anything else that he turned blindly and hurried through the door. In the reception hall he paused for a moment and wiped the perspiration from his brow. He had made an ass of himself, no doubt; but it had all been so unexpected. That woman— He was suddenly aware that the landlord was approaching, carrying a large book in his hand.

"Excuse me, sir," he apologised. "If you wouldn't mind signing the register... With the police about like this—"

Timothy obeyed without a word. Then above his own signature he noticed the two fresh entries—one dated that morning, and one the day before. Automatically he read them.

"Mr. and Mrs. Mayence, Mary Cunningham."

He handed the book back. The landlord blotted it carefully, and closed it.

"Going out, sir?" he asked respectfully. "You'll want lunch?"

"Just for a walk... Yes." Timothy hesitated. "Mr. Petworth's house. Just where is that?"

"Up the lane a little piece—just by the church... Well, sir, it's almost opposite Mr. Fareham's—where—"

"Thank you," Timothy said curtly, and went out.

There was little enough of the village. Only the hotel, relying on the holiday traffic to the little cove below, was of any size. Otherwise three shops, a post office, the church and a Methodist chapel seemed to comprise the principal buildings, and there was not a great deal besides. But it seemed to Timothy that the whole place was one big stare. He did not know if any detective was watching him as he turned up the lane; but everyone else was.

His spirits revived as he walked up the narrow road beside the stream. The village might be curious enough to stare; it was polite enough not to follow. And it seemed as though Hayle had neglected the elementary precaution of having him shadowed. He satisfied himself on that point in the first quarter of a mile, and that very fact reassured him. By daylight the walk seemed shorter than it had done the previous night. It was only a brief time before he came in sight of the twin white gates facing each other across the road.

Last night, however the mistake had arisen, he had taken the one to the left. The one to the right must actually lead to Three Gables. And there, presumably, there would only be the ancient butler of whom George had spoken. Everything seemed plain sailing. And then, from the opening of the gate leading to Fareham's house, a tall helmeted figure stepped out into the road. It was a policeman.

Timothy drew back instinctively. There was nothing wrong about his going to see George. Of course the policeman had been put there to keep away possible sightseers. But he would certainly see that Timothy went to Three Gables, and report it. When he came to think it over, Timothy was not too keen on that. There was no saying what construction might be placed on the visit. If it could be avoided it would be all to the good. And suddenly he remembered a point on the road a little way back where a gap in the wall had led to what had seemed as though it might be a short cut. At the time he had thought about taking it. Now he decided to do so. Choosing a time when the policeman's back was turned, he started to retrace his steps, and in half a dozen strides was safely out of sight.

The gap was a bare thirty yards away. And yet, if he were seen going that way, it would look worse than if he boldly walked past the policeman. He seated himself on the wall of one of the bridges crossing the river and felt for a cigarette while he thought things over. He was in the very act of striking the match when he saw someone emerge into the roadway, glance up and down the lane, then scurry across into the bushes which fringed the other side. He let the match drop unheeded in his surprise. It was George.

His first thought was to shout. But the policeman would hear. He might come to investigate. The only course was to follow and overtake him; though at the pace George had been setting that might take some doing. In a moment he had started down the lane towards the point at which his friend had vanished.