RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

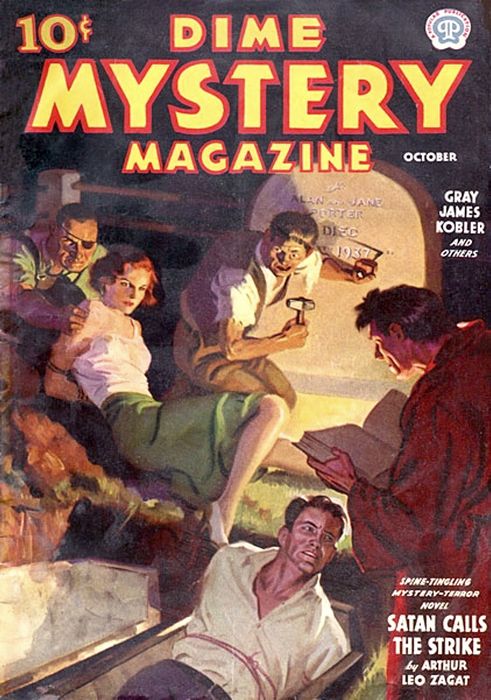

Dime Mystery Magazine, October 1937 with "Children of Murder"

A Novel of a Terror that Drove a City Mad.

All New York was in a seething turmoil. Terror reigned supreme while hundreds of men and women died horribly, and bands of shrieking, predatory children raced, maddened, through the streets.... A masterful story, vividly told, which—we warn you—will haunt you in your sleep!

IT was by mere accident that Jessica and I happened to be in New York on the very day that the Terror struck. As everyone knows who survived the ordeal, or followed its dreadful course in the headlines of the world, the first tragedy occurred on the afternoon of June 26th.

On the morning of that day, all unknowing, we had stepped off the Chicago flier, eager to catch our first glimpse of the great and fascinating metropolis that is the Mecca of all Midwestern honeymooners. Jessica Tarrant had become Mrs. Rodney White only three days before, and I was still slightly intoxicated with the idea.

James Tarrant, Jessica's uncle, had met us at the train, and whisked us to his magnificent duplex apartment on Park Avenue. It had been at his urgent suggestion that we had come. He seemed preoccupied and rather harried, however, for a man of so much wealth. He fidgeted uneasily all through lunch, then excused himself hurriedly.

"An important appointment," he mumbled into his liqueur. "You children run along now and see the town. We'll do things right this evening, though. Dinner at the Colony, a show, and a midnight snack at the French Casino." He shook hands with me cordially—a tall, stooped man with quick, nervous movements and a worried look. He was still active in his business; something to do with the manufacture of chemicals, I knew vaguely. Then he was gone, leaving us to our own resources.

Jessica thrust her arm gaily through mine. "Let's go slumming, Rod," she suggested enthusiastically. "I've heard so much of the East Side, of the ghettos of New York. I'd rather see swarms of people, strange, exotic folk, even smell the smells of crowded sidewalks, than visit a lot of stodgy monuments and museums."

I, being very much in love, and newly married, naturally assented.

WE took the subway down to Grand Street, walked east through a maze of narrow, crowded streets. I had never seen so many people together in one place in all my life. They jammed the sidewalks, they flowed into the gutters, they hung out of windows in the shabby tenements; they gesticulated, they chattered, they bargained with hucksters; and everywhere under foot, dodging death in front of honking cars, were dirty-faced children.

Jessica almost danced as she walked. "I adore children," she said fervently.

"So do I," I muttered, wrinkling my nose in some disgust. "But not these smudgy little brats with their weazened faces and all-knowing eyes. And as for smells, darling, I hope you've had your All. Let's get out of here."

But Jessica, bright-eyed, breathless, was pulling me by the hand. "Look at that perfectly quaint little street," she exclaimed. "Come on, Rod. We've got to explore it. It might be a street in Europe."

We were nearing the East River now, and the street she had pointed out twisted crookedly between tall, leprous-looking tenements down to the dull gray waters beyond. The sunlight never penetrated its murky depths, and even the people who sat hunched on the stone stoops or who walked with slow, slouching steps along the narrow sidewalk seemed of a different race than the loud-chattering gesticulators we had just left. An overpowering smell of decay, of stagnant bilge, literally smote me in the face.

"Better get gas masks, then," I grumbled, but I followed nevertheless. Far better had I yielded to my first instinctive revulsion and insisted that we turn back!

The street was quiet, listless. Men slouched by, thin coat collars lifted over ragged, collarless shirts, though the day was hot. Shrivelled women stared after us with hostile eyes, resenting our presence. Even the children, swarthy, foreign in look and attitude, moved with stealthy tread and scuttered away at the sound of our feet.

"Now look, Jessica," I began, "Don't you think this interest of yours in how the other half lives is rather morbid? These people—"

I cut short abruptly. The half-formed word hung frozen on my lips, died in a swift tightening of muscles and paralyzed breath.

Directly in front of us a man had screamed.

I had heard men, and animals too, scream in the agony of death before. But never had I heard such terrible, high-pitched, tortured sounds issue from an human throat.

I had noted him casually in the semi-gloom. A derelict, manifestly—a homeless bit of the flotsam that washes eternally in the slums of big cities. The frayed collar of his coat sawed at his unshorn hair, his nose and eyes alike were bleared with rheum, his feet flapped in toeless shoes. He shambled toward us, ready with his beggar's anticipatory whine.

Then he had screamed.

His hands flew suddenly to his throat, then beat down upon his body with furious blows. He leaped high in the air, writhed and twisted in horrible convulsions. And all the while the shrieks of agony flowed unendingly from his pallid lips.

"Good God!" I jerked out, and ran toward him.

But all at once the tortured man's body seemed to burst into flame. In a single second he blazed up like a pitch-pine torch. Clothes, flesh, bones wreathed in a billow of fire and smoke. A single moment his convulsed countenance turned to us through the licking glare, then it too exploded into a seething furnace.

Suddenly, he was down, a blackened smoking corpse, faceless, hairless, the clothes burned from his twitching body, the flesh seared from his bones.

IT had all happened so instantaneously that I had made only a few steps toward him when the end came. A split second's horrible silence; then the street awoke. Shouts, cries, the screams of women, the shrill whistle of a policeman.

I stared as one benumbed, heedless of the pounding feet behind us, even of Jessica's tense pull on my coat sleeve.

"It's impossible!" I moaned. "There was no one near him. Nothing hit him. Yet he burned to death as though he were inside a blazing furnace. How could—"

I became aware of the crowding people, their horrified, yet almost gloating faces. A policeman pushed his way importantly through the fast-growing mob. Then the thing that lay motionless on the stone sidewalk struck him. "Holy cats!" he gasped. "Wh—what happened? Who saw it?"

I started forward, only to be jerked back by Jessica's hand. She was pale, sick. "Don't go," she husked. "You can't do the poor fellow any good, and we'll be pestered by the police and reporters for weeks.' "

"But it's my duty as a good citizen to tell what I know," I protested.

"You know nothing," she answered slowly. A curious fixed look had come into her eyes, hiding the horror, the sickness, that had filled them before. I followed her gaze.

On the opposite side of the street a little boy lounged nonchalantly against a stoop, his hands in his pockets. He had not joined the pushing, morbid mob that milled around the charred remnants of what had once been a man. His features were pinched and smudgy, his appearance that of a typical gamin. But his large eyes were intense on the scene, greedy, glowing with an unholy luster. He could not have been more than ten.

So fierce was his absorption that at first he did not notice our glances in his direction. But suddenly he looked up, saw us. The glitter died in his gaze; a look, half fear, half sullen defiance, took its place. He averted his eyes, hunched his shoulders, started to shuffle rapidly down the street, hands still deep in trousers pockets.

"Filthy little beast!" I muttered venomously. "Did you notice how he gloated on the sight of that horrible body? If I had my way—"

But Jessica was tugging sharply at me. "Quick, Rod," she whispered. "Let's follow that child."

I stared, laughed disagreeably. "Surely you don't want to adopt the little dear?" I said with fine sarcasm. I knew my wife's penchant for children—any child! She adored them all.

Jessica ignored my sarcasm. The boy had disappeared around a corner. She literally pulled me along. Her hand trembled, her face was white and drawn. "I don't know what it is, Rod," she panted."1 never felt this way about a child before. But there was something loathsomely evil in that little boy's face. I shivered as I looked at him."

"More swell reasons why we should chase after him," I grumbled. My nerves were jangled from that which still lay on the ground behind us.

"Don't you understand?" Jessica's voice sounded choked. "That boy was there, leaning against the stoop, watching that poor man before he died so hideously. And he never moved, or cried out, or showed fear all during the catastrophe; just stood there and—and gloated. It's not natural."

"Damn right it isn't!" I said, startled. Instinctively I hastened my pace. We swung around the corner, left the crowd still milling ever the gruesome body. An ambulance clanged madly, more policemen were hurrying up.

HALF way down the block, we saw the little boy. He was walking swiftly, head bent, looking neither to the right nor to the left, hands still deep in his pockets. Beyond lay the river, turgid, sullen even under the impact of dancing sunlight. A tug steamed slowly, tracing a black smudge against the sky. A truck rumbled by.

It was I who set the pace now, to follow that youngster wherever he was going. Strange thoughts whirled in my brain. Doubtless I was a bit unhinged by what I had seen. It was ridiculous to associate a little boy of ten with the horrible tragedy we had witnessed. It was incredible too. But we held to the trail.

The boy had not seen us, had not looked back once. His movements were swift, purposeful. We turned the corner into River Street to see him dodging among strolling sailors, hustling longshoremen, heavily laden drays, huge boxes that encumbered the sidewalks.

Dingy freighters lay at ancient piers, taking on freight, unloading. The air drooped with heavy odor of sea, decaying fish, ripe bananas and tangy spices from Oriental ports. Lascars with dark, savage faces and bright tinsel earrings swaggered by. Filipinos mingled with Cockney sailors from a British tramp. Warehouses gave way to ship chandlers' shops, dingy with ancient ropes and rusty binnacle lights; saloons foul with stale whiskey slops alternated with one-night clip joints; a deserted seamen's chapel was mocked by chattering apes and parakeets in a neighboring pet shop.

But the boy dodged on, and we followed. The street grew fouler and dingier, the legitimate bustle of the sea disappeared, to give way to more furtive buildings, to men shuffling along to strange destinations. Jessica gripped my arm.

"Perhaps we'd better turn back," she whispered. "After all, it was only a silly notion of mine."

I am a stubborn man, I must confess. I should have listened to her, should have dropped this seemingly profitless chase. We would have both been saved an infinitude of nightmare horror and suffering that still etch deep into our bodies and souls. But I just gritted my teeth and played the hunch my wife had first had, and which now I had taken over. The memory of that unfortunate derelict, blazing suddenly like a torch, had tinged my brain with a certain madness.

Then I stopped short with an exclamation, gripped my wife's hand unbelievingly. One moment the boy had been shuffling close to the wall of some particularly evil-looking houses not two hundred feet ahead; the next, he had disappeared. I had not seen him duck into any doorway, and the afternoon sun made a dingy brightness of the tawdry street. But vanish he had; and he did not reappear.

I swore in bewilderment. Jessica was frankly trembling now. "Rod, darling," she implored. "I've had enough. Let's go back, before it is too late."

"Too late for what?" I growled. "I'd hate to have it said that Rodney White got scared of a ten year old street urchin. You started this; now I'll finish it." Brutal talk to the girl one had just married and loved insanely, but the poison that was soon to envelop all New York was evidently already sapping my emotions, my reason.

I hurried openly to the place where I had last seen the gamin. Jessica, lips tight, cheeks drained of color, was at my side. I stood staring blankly at the tight-crowding walls. There was no alleyway through which he might have suddenly dived. Two warehouses stared back at me, tight-boarded, deserted, faceless against the sun.

But between them, squatting low like a nondescript beast, was a little shop. It looked equally dark and deserted, its solid wooden door chained and padlocked. Its solitary window was grimy with accumulated dirt; nothing stirred within its darkling depths.

Then a shaft of vagrant sunlight pierced the filth. I started back, heard in a horror-stricken haze Jessica's faint cry. A head was grinning out at us through the filthy window; a head of snarling evil and unutterable hate. Dead black hair plastered over swart, distorted features, and the eyes that glowered at us were wide and queerly drawn at the edges.

Next to it was another head, peering out at us with twisted mockery. A face even more incredible than the first. So tiny it could only have been that of a nine-months babe, yet infinitely old in its expression of savage malice and yellowed fangs. A fuzz of back mustache stubbled its retracted upper lip.

"Rod, darling," Jessica moaned. "They're watching us. They're moving; coming out after us! Let's get away. I'm terribly scared!"

Stiff legged, feeling my own lips snarl back like those grinning heads, I strode to the window, wiped vainly with my hand at the encrusted grime. I cupped my eyes, peered in.

My wife's fingers plucked at me; I disregarded her. Then suddenly I turned, grinning wanly. "They're not alive," I said. The sweat poured from my forehead. I had been more afraid than I would care to admit. "They're human heads, all right, but they're dead."

"Dead?" echoed Jessica in alarm.

"They've been dead a long time," I hastened to add. "One is doubtless that of a Papuan—a head hunter's trophy. The other that of a South American Indian. You've heard of how the tribes in the Amazon manage to shrink the heads of their slain enemies to the size of a tiny doll."

My wife shuddered. "But what are they doing in that window?" she asked.

I frowned at the dirty glass. "A curio shop of sorts, I suppose," I muttered. "Rather ghastly, I admit, but there's no accounting for tastes—and especially the tastes of sailors."

I jumped almost a foot at Jessica's sudden clutch at my arm. My nerves just then were not too steady. A voice had spoken—from nowhere. A thin, quavering voice, freighted with a queer jangling palsy.

"Will you be pleased to enter?" it said. "I have rare and curious things to show you."

WE both seemed rooted to the ground as the wooden door of the shop, padlock and all, swung silently open. A stale, dank odor rushed out into the street. Then a light sputtered into being, a candle held high over a figure's head, framing him in a halo of yellow illumination, making the darkness behind more thick and impenetrable than before.

He was bowed and gnarled with age, and a long black robe shrouded his spare form, flowed down to the floor itself. On his bald forehead rested a pointed hat, high-crowned. From beneath its brim, a few wisps of muddy grey hair straggled to his shoulders. But his face was uncannily like that of the doll-sized mask which rested in the window. Wrinkled parchment, bony nose, yellowed front teeth, eyes that veiled their cunning in a horrible attempt at a smile of invitation.

"Will you be pleased to enter?" he repeated.

Jessica bit her pallid lips, answered unsteadily. "No—that is—"

I felt my jaw ridge into hard knots. I made a sudden decision. "We'd be glad to," I said loudly. I pretended not to hear my wife's little exclamation, nor feel her restraining hand. I wanted to see what was inside that shop which held human heads within its grimy windows.

The old man smirked and bowed. "Of course," he quavered, and cast a sidelong glance at Jessica. "I have things of much interest—especially to such a young and pretty lady."

Cold air stirred down my spine. Already I regretted my decision, would have given worlds to have withdrawn it. But stubborn pride led me in; pride and the knowledge that I was more than a match for this palsied creature in outlandish costume.

The candle thrust its feeble light uneasily around a crowded den. Vaguely it pricked out half-visible things on the tiers of shelves, things that pressed Jessica closer to my side. I felt her trembling violently. Out of the corner of my eye I had noted that the door had swung noiselessly shut behind us. The conviction grew on me that it had locked; that we were trapped. The window through which we had peered at the gruesome trophies of the headhunters was shielded by a high, stout panel. The interior of the strange little shop was wholly cut off from the outside street.

The old shopkeeper chuckled with wheezing breath as he lowered a lantern from the ceiling by its swinging chain, turned up its charred wick, rimmed it with flame from the light of his candle.

"I have many pretty things," he cackled, "many pretty things that your wife must desire. Look!"

We stared around the dust-covered shelves. The dust lay thick upon everything. As though nothing had been touched, nothing moved, for many years. My body stiffened; I heard Jessica's breath come and go very fast.

It was a strange shop we had blundered into; a damnable shop!

There were more of the hideous human heads grinning down at us along those shelves. An Iron Maiden stood upright against the farther wall, open on its pivot, disclosing the grim serried spikes that long ago had pierced with slow-increasing pressure the unfortunate victims within. Their tips were a musty red. Somehow I knew that it was blood. A stout rope dangled from a smoky beam.

"That," he said with queer pride, "is the rope that hung Captain Kidd." Then he pointed to a knife-like edge in a slot. "And that," he whispered, "is the very guillotine that sliced off a thousand pretty heads in Paris." His gaze returned slowly to Jessica. "You, my dear, have just the slenderness and grace of neck for my plaything."

I HAD had enough of it. My hair had bristled at the sight of the other trophies on those rows of shelves. Goblets filled with a thick, syrupy red liquid that looked horribly like blood; instruments of torture, garroting bows, wicked Malay krises, able to disembowel a man at one cruel thrust, devil masks of the Congo, turnscrews to squeeze the victim's brains into a pulp, stuffed bushmasters and cobras with beady, glittering eyes, most poisonous of snakes.

The old man himself was like one of his withered, dust-covered trophies. His snake-like eyes had not removed from Jessica's shrinking form. "Would you care to buy?" he asked insinuatingly. "I have something special for the lady. The very ring that Borgia used to poison her friends. Perhaps—"

"No; we don't care to buy," I answered angrily. The old man with his high-crowned hat and long black robe was obviously mad; his brain turned by long immersion in this airless shop with its sinister trophies. It was ridiculous to believe that he had the hangman's rope used on Captain Kidd or the Borgian ring that had long since disappeared from history. It was just a curio shop, leaning toward the macabre. Doubtless the trophies were fakes, and just as obviously they had not been disturbed for years.

Yet I could not restrain a certain uneasy prickling of my skin. I would be glad when we would emerge once more into the open street, into the sunshine. But being stubborn, I held like a hunting dog to my point. Warily my eyes searched every nook and cranny of that evil shop. No sign of the boy, no sign of any exit other than the outside door.

"What," I demanded suddenly, "has happened to the little boy who came in here some minutes ago?"

Jessica gasped once. Then there was silence. The queer shopkeeper had tensed within his robe. His eyes, deep-socketed, blazed with hellish fires. The very walls seemed waiting for the answer to my imprudent question.

Then he turned, slowly, pivoting. A mask of blankness had fallen on his lank features. "Boy? What boy?" he mumbled. "I have seen no boy."

I knew that he lied; yet I was glad. I had the feeling that I had stepped unwittingly into a hellish brew—and Jessica was with me. I wanted to get out as fast as possible.

"Okay, my mistake!" I said with false heartiness. "He must have ducked around the corner." I grinned. "He looked from a distance like the son of a friend of mine." A lame explanation, I realized; but it was the best I could do on the spur of the moment. "Now," I went on cheerfully, "we'll be going."

The shopkeeper made no move. His eyes burned on my wife. "No one," he whispered dryly, "leaves the store of old Jem until he buys."

"That's what you think," I retorted with a creditable amount of sarcasm, and strode to the door. I reached for a knob. There was none. I dug my fingers furiously into the crack between door and jamb, tugged. The door did not budge.

I whirled on the old man, fists clenched, heart pounding with anger. "Now listen to me." I snarled. "We're not buying any of your filthy wares; and furthermore, I'm giving you three seconds to open this door, or—"

He had not stirred. His hands were concealed in the folds of his robe. Jessica saw something move, cried out sharply. "We'll buy, Rod—anything! Tell him we'll buy!"

Instead, I bunched my muscles for the forward drive. Yet somehow I had a sickening realization that I would never reach him alive—that we were both completely at his mercy.

The old man cocked his baldish head suddenly to one side. He seemed to be listening to voices inaudible to us. Without knowing why I did it, I halted in my tracks. The perspiration streamed down my face. I heard no sound, no voice. To whom was he listening?

Slowly he nodded his head, as if in reluctant confirmation. His nut-withered face wreathed into an evil smile. His skinny hands emerged into the open.

"Yes, yes," he chuckled to himself, "that will be better—much better!"

He rubbed his hands together until the dry skin crackled, while I stood in open-mouthed amazement. Jessica huddled against me. I could feel the loud thudding of her heart through her sheer silk dress.

Slowly Jem lurched forward. "Yes, yes," he repeated. "It will be better thus." His bony finger stabbed at the smooth panel of the door. It swung silently open. The fetid, musty air of the shop whooshed out into the street. Sunlight blazed. Never in all my life had sunshine and a dirty, debris-strewn street filled me with such delight.

I grasped my wife by the arm, hurried out.

Jem made no move to stop us. But behind, just before the barrier swung once more into tight seclusion, I heard his wheezing chuckle. "Later, you will buy!"

BREATHING deeply, we walked as fast as we could. Somehow we dared not look back. "What a horrible old man; what a dreadful shop!" Jessica shuddered.

I said nothing. What had he meant by that last remark? Was he playing with us as a cat does with a mouse, knowing full well he could place his sharp claws on us again? Almost angrily I tried to shake off my uneasy forebodings, to convince myself that Jem was merely a harmless old madman, whose brains had become addled from the grim curios in which he trafficked. For the nonce, I quite forgot the frightful immolation we had witnessed, the little child we had followed.

We were reminded of them soon enough, however. The afternoon sun had westered below the Jersey flats, and we were too shaken to linger long in the streets that fronted the river. I hailed a cruising cab, told him to drive fast for Park Avenue and Tarrant's apartment.

But there, in the great dropped living room with its wrought-iron balustrades and costly furniture, we found company. Men I had never seen before, talking in strained, rasped voices, huddled together in the center of the room as if they feared to stand apart, to show themselves alone.

Their talk hushed suddenly as we came in. Fear was obvious in their haggard eyes, in the way they jerked back from our abrupt entrance. But James Tarrant's voice rose loudly—to loudly, I thought. "It's all right. That's only my niece and her husband. Just married, you know. Came to visit New York. Ha—ha!"

His laughter was forced. He seemed more stooped than in the morning; the corners of his mouth twitched; there were new wrinkles around his eyes. He hurried forward to greet us. "Thank God you're all right!" he husked. "I was worried—" He pecked at Jessica's cheek, shook my hand.

For the moment I was staggered. "How did you know—" I started unthinkingly, stopped.

"Know?" He threw out his hand with a gesture as if to ward off something. "Why, everyone knows. The city's already crazy with terror. That's why these gentlemen are here."

In spite of my shock, of my own sick fear, I was a bit scornful. The town I came from boasted only a few thousand people, but they wouldn't go haywire because of what I had witnessed, gruesome enough though it was. "You mean New York City's scared to death because a single man dies—"

A gentleman withdrew himself from the huddled group. He was striking in appearance. His tall, spare form was carefully encased in correct frock coat, grey striped pants, patent leather shoes. A monocle glittered in his eye. Behind it stared a glacial, supercilious coldness. His face was abrupt and angular, his manner that of one born to command.

"A single death?" he echoed in the precise English employed by cultured foreigners. "My dear sir, my dear young man where have you been all afternoon? Already a hundred men and women have flamed unaccountably to a terrible death, and the list mounts every minute!"

I FELT the cold trickle of fear in my veins. Jessica gave a little moan. "A hundred?" I gasped. "I thought there had been only one—on Cliff Street."

My wife's uncle introduced us with a certain futile distraction. "Count Lockhorst, this is my niece, Jessica, and her husband, Rodney White."

"The chap on Cliff Street was the first to be struck down," said another man quietly. He was dressed in a plain blue sack suit that could not conceal his bulging shoulders. His face seemed carved out of a solid block of granite, and his eyes were gimlets. "Since then, all over the city, over a hundred more have burned to cinders, on open streets, in full view of thousands."

"It's about time that your men put a stop to it. Inspector Byrnes," a paunchy, heavily-jowled man said violently. "Why don't the police do something about it? We're paying taxes for protection. Why, by tomorrow, there won't be a soul that'll dare to venture out into the streets." Inspector John Byrnes turned slowly to the last speaker. He surveyed him with a certain studied contempt. "We can't put a stop to something that we know absolutely nothing about. It's a fantastic situation. People burning to a crisp suddenly, without rhyme or reason, in full view. We've already checked with scientists, including Mr. Tarrant's factory superintendent, Philip Jaeger. That's why I came here this evening. They all agree it's impossible for human flesh to burn like that, no matter what chemical or combustible might be used. Isn't that so, Mr. Jaeger?"

A short, grey-haired man nodded uneasily. "That's right, Inspector. We've been manufacturing chemicals for years, especially of the combustible type, and there's nothing in my experience that could produce such an effect. Besides, the victims would have to be drenched with liquid, and from your descriptions, there wasn't a chance of that."

"So you see, my dear Ambrose Twombly," Inspector Byrnes told his critic with soft emphasis, "we are helpless thus far. Even if you do pay taxes for our support, which I doubt."

"What do you mean by that crack?" Twombly blustered. "I'm a reputable broker. You can ask Mr. Tarrant. He asked me here to discuss a new flotation of stock for his business."

"Our records," mused Byrnes as if to himself, "have a file on a certain Ambrose Twombly who is a cheap confidence man, a grift artist who followed the circuses and raked in the yokels' small change. That wouldn't be you by any chance?" The paunchy man paled, rallied. "Sir," he puffed, "that is libelous. I'll take it up with your superiors at once."

"They'll be very much interested," murmured Byrnes.

"Here! Here!" protested Tarrant. "You mustn't insult my guests. We have business to attend to. Count Lockhorst is in New York on a mission from his government to negotiate a contract with me for a large supply of chemicals. Now if you'll excuse us, Inspector—"

Byrnes did not move. His keen eyes probed thoughtfully around the taut circle of men, came to rest on myself and Jessica.

"There is one further point," the Inspector said suddenly. "We've checked eye-witness accounts of every burning so far. Except one. No one actually saw the first man burn to death—in Cliff Street. But a woman happened to look out of a window, just before it happened. She claims there was a couple walking in the street, close to the spot. No one else was there, but the unknown bum. But when the police arrived, the couple had vanished. She thinks she might identify that young man and young woman if she saw them again. They were well dressed, and obviously not of the neighborhood." He swerved quickly on us. "Do you," he asked pointedly, "know anything about them?"

Jessica turned pale as snow, swayed unsteadily against me. "No! no!" she said faintly. "How should we?"

I TOOK a deep breath. I cursed myself for having betrayed ourselves by my unfortunate earlier remark. Inspector Byrnes was obviously not a foeman to be despised. "Yes, I do," I said steadily. "In fact, Inspector, we were the couple."

A faint stir ran through the men. A slight shrinking, as it were, as though somehow we had been responsible.

"Ah!" the policeman said softly, with a satisfied nod. "I thought it might have been you. Now tell me about it."

I did so, as rapidly as possible. I even told the story of our wild-goose chase of the little gamin, of our experiences in old Jem's grisly shop. As I talked on, I noted a certain stiffening on the part of Philip Jaeger, the mill superintendent; a queer ghastly pallor that overspread his face.

Another man entered quietly just as I finished. He spoke in a whisper to Tarrant. He was youngish looking, with coarse, straight black hair, and a wiry, muscular body.

"Good God!" ejaculated my wife's uncle, and fell back. "Listen to this, Inspector. This is Bayard Dickson, my assistant superintendent under Jaeger. He just told me—"

Byrnes waived him aside. His probing glance made holes through me. "What you say, White, about old Jem is of course nonsense. We know him well in the department. Mad as a hatter, but a harmless old coot. Prides himself on being a hypnotist, too. He's been in that shop of his for over twenty years, pottering around those silly curios he has. The sailors and longshoremen laugh at him; he hasn't sold one in years. As for children, he hates them. The kids in the neighborhood follow him and throw stones. No, you're all wrong there, White. You two just allowed the grisly atmosphere to get on your nerves, especially after what you had been through. But as for the little boy—"

He walked swiftly to the table phone, lifted it, spoke into the receiver: "Spring 7-3100, please!"

Police Headquarters!

Then: "Hello, Tim, get me Clancy, pronto. Hello, Clancy; yeah, this is Byrnes. Got the files on these fire-deaths before you? Good! Now listen—" His voice lowered, became inaudible. Then he stopped and listened in turn. When he finally pronged the receiver and turned to face us, his eyes were hard and his jaw set.

"In every case, except one," he announced. "some witness deposed that there was a child on the scene. Little boys, little girls. Ages approximately from eight to twelve. No older, no younger! And now you've completed the file on Cliff Street." Bayard Dickson said slowly into the stunned silence. "I was just telling Mr. Tarrant. On my way over here, I saw a woman burst into flames and fall screaming to the sidewalk, just outside this door."

A sigh of horror rose from the men. Philip Jaeger's voice was broken with terror. "It's coming closer—to us."

Byrnes jerked out of his seat. "Was there any child present Mr. Dickson?"

The man wrinkled his forehead, tried to think. "I don't exactly—" he started; then: 'That's right; I remember now. Leaning against the wall of the next house, about thirty feet away, was a youngster. I thought she seemed too calm and self-possessed about it. It wasn't natural."

"She?" gulped Twombly. He hadn't spoken since Byrnes had faced him down.

Dickson nodded. "It was a little girl—about nine, I should judge."

Byrnes cursed, went swiftly for the door. For a big man he could travel fast. "If only I can catch the little brat," he flung over his shoulder, and was gone before we realized it.

BUT even in the depths of my horror, I knew he would never lay hands on her. I am as sane and skeptically unsuperstitious a man as you could find. But that youngster we had seen had something malign, utterly evil about his weazened face that made him seem not quite human; a changeling in childish form. And now all these others!

It might be sheer coincidence that they were present at the scene of every horror, but I didn't believe it. I knew that Jessica for all her love of children did not believe it; and worse still, I was certain that New York tomorrow would not believe it.

In the middle of our sickish silence I heard Count Lockhorst say with thoughtful intonation, "This reminds me of certain episodes that occurred in the remote mountains of my own country. But there the peasants, superstitious folk, attributed the plague to a witch."

"What happened finally?" Jessica asked timidly.

He fixed her with his precise glance through the staring monocle. "They burnt the witch, my dear lady, and the plague was over!"

Twombly's loud, vulgar voice interjected. "Bunk!" he declared vigorously. "This is America, God's country; not backwoods Europe! I'll tell you what it's all about."

We swerved to him. He had recovered his assurance, now that Byrnes had left; his jowls wagged pendulously.

"What?" asked Jaeger faintly. Twombly took out a big cigar, lit it, puffed violently. "It's just a blackmail stunt, that's what it is," he declared with confidence. "Some wise guy's trying to scare New York out of its wits; then he's gonna try and collect from the big shots for protection." He whirled on my wife's uncle, shot out a fat finger. "Like you, for instance, Mr. Tarrant."

Tarrant shrank back. "Me?" he spluttered. "Why, it's—it's nonsense!"

But the broker—or confidence man—jiggled his cigar vigorously. "Yes, sir, that's what it is. Mark my words! Me—I've seen it before." He had forgotten his pose, had reverted to the argot and manner of his former life.

Dickson said with scorn. "Your explanation, Mr. Twombly, of course explains—everything. Just how this—uh—trick is worked by your mythical blackmailer—for example."

Twombly sawed at his collar, as if it had suddenly become too hot. "I—I don't know how he works it—but mark my words—it's a racket all right." His little eyes darted around the room. "Gotta be going," he muttered. "It's late—an appointment." He sidled toward the door.

"I'll go with you," Dickson announced. "In spite of everything, Mr. Tarrant's plant must be kept going."

It seemed to me he cast a faint glance of contempt toward his superior, Philip Jaeger. The latter was a greenish-yellow, but he said nothing. My wife's uncle took a deep breath, looked at Jessica and myself.

"If you'll excuse us three," he hinted, "we have business."

WE took the hint, left Tarrant, Count Lockhorst, and Jaeger in the library, climbed slowly to our room on the second floor of the duplex. Jessica was paler than I had ever seen her. "Rod, darling!" she said suddenly.

I paused at the window which overlooked the street. I was making sure the fastenings were tight. In the distance, far down the side street, I had caught the red reflection of flame somewhere, heard the faint echo of a scream. "Yes, Jessica," I said very loudly to hide that horror-fraught sound, blocked the window with my body to conceal the telltale glare.

"I think," she remarked quietly, "we've been marked for destruction."

"Eh, what's that?" I exclaimed startled. All evening the same thought had been etching into my vitals.

"We've seen too much; know too much," she persisted. "Everyone downstairs heard us pin the blame on little children; they heard us accuse old Jem. Tomorrow all New York will know about it as well."

"Dickson didn't hear," I protested.

"I saw him," she answered. "I saw the door open slightly just as you started to talk. Then it didn't move another inch until you had finished. When you were through, Dickson came in. He had been listening outside all the while. Why?"

I couldn't answer that one; couldn't answer anything. "As for old Jem," I evaded, "Inspector Byrnes gave him a clean bill of health."

"Do you believe it?"

"No!" I answered heavily, and went to bed. But close to my hand I placed the stout poker from the fireplace.

Nothing happened that night.

But in the morning hell had broken loose.

We were awakened by loud voices below, by the tramp of feet, of banging doors. Hastily we dressed, went down. Tarrant was in the breakfast room, his orange juice untasted before him, his coffee getting cold. His face was ashen-grey, his eyes staring. Seated with him at the table were the same men who had been there the night before. Only Count Lockhorst seemed calm. He was sipping coffee with manifest enjoyment.

"Great Heavens, Uncle!" Jessica slipped from me, ran to him in alarm. "What has happened?"

"Happened?" he gulped, and almost choked. "First look at this."

He thrust a newspaper into her hand. I read the headlines hastily. They were easy to read, yet the tremendous type blurred and danced before my eyes. The ink was still wet, as though the edition had been rushed off the press at breakneck speed.

"The Terror Spreads!" it screamed. "New York Scene of Indescribable Horror! At Time of Going to Press Over 500 People Have Perished in Flaming Holocausts. More Dead Each Minute. Police Baffled; Scientists at Loss. Extra-Special. Human Torches Attributed Somehow to Children. Suggested by Jessica White, Niece of James Tarrant, Wealthy Manufacturer. It has been discovered...

I read no more. A sick feeling overcame me, left me weak in the knees.

"What damn fool," I demanded harshly, "was responsible for coupling my wife's name with that story?" I looked pointedly, with clenched hands, at Inspector Byrnes.

He shook his head in the negative. There was fine lines of worry beneath his eyes I had not noticed there the night before. "If you mean me, White," he said, "you're mistaken. I wasn't responsible for the leak. But there's more news. Mr. Tarrant, show him."

My wife's uncle thrust out a trembling hand. "Look at this, Rodney," he quavered. "I found it under the door early this morning."

I took the sheet of paper. It was of common texture, impossible to trace. The writing had been crudely printed in childish letters. Childish! I felt the warm perspiration trickle slowly down my back as I read.

You are next; you and your niece, Jessica White. You have witnessed my power; it is only a foretaste. Do you wish yourself and your niece to become flaming torches? If not, place a red card in the window overlooking Park Avenue. Get $100,000 in cash, small bills, unmarked. You will receive instructions what to do. It will do you no good to go to the police; that will only hasten matters.

"AND a half a dozen other men of wealth received the same kind of communication this morning," Byrnes added.

"Blackmail!" Ambrose Twombly boomed. "Just what I had expected. Just exactly as I told you."

"Oh, you did?" The Inspector narrowed his eyes.

Twombly drew in his horns hastily. "Sure, Mr. Byrnes," he said placatingly. "Don't it look to you like that kind of a racket? First you scare the living daylights out of a whole city; then you concentrate on the fellows who can pay for their scares."

Byrnes nodded thoughtfully. "It begins to look that way," he murmured.

But I was in no mood for useless chatter. The hideous menace that enveloped New York had now definitely narrowed its net to Jessica. The monster had shown his power; now he intended to strike. My heart skipped a beat; stopped. "What do you intend doing about this, Mr. Tarrant?" I asked unsteadily.

All eyes turned to the old man. He was haggard, shrunken into himself. "Do?" he echoed. "What can I do but pay? It's my life, and Jessica's."

I started to breathe again. Jaeger was mumbling to himself. "Of course, that's sensible."

Even Byrnes nodded. "I hate to say it, being a policeman. But we're helpless—as yet."

Bayard Dickson, however, jerked forward. "Do you realize what that means?" he snapped. "That's about every cent of cash you have, Mr. Tarrant. We were going to use it to put through our contract with Count Lockhorst's government."

The Count set down his empty cup. His monocle held motionless in his left eye. "My government will insist on deliveries according to the terms," he said evenly.

Dickson turned on him with a snarl. "If Mr. Tarrant pays this blackmail the whole deal is off then," he cried.

"What would you do in my place?" the old manufacturer quavered.

The assistant superintendent's face was a hard, set mask. "Fight them," he gritted. "This contract's your only chance to pull you out of a tight hole. Mr. Jaeger knows that as well as I. There's no proof that this blackmailer actually has anything to do with this mess. Perhaps he's only horning in." His voice sharpened. "Doesn't it strike you as funny that he should know exactly how much free cash you have?"

Byrnes narrowed his gaze. "Good point, that!" he murmured.

I spoke then. "My wife's life is involved. How about it, Tarrant?"

He nodded wearily. "You're right, Rodney. We can't take chances. The contract must drop."

Count Lockhorst rose, adjusted his frock coat, bowed with clicking heels. "In that case," he smiled thinly, "I shall leave you. My government requires those chemicals at once. There are other manufacturers. Good day!"

The red card flaunted its message in the window according to instructions. And over the city, in half a dozen other homes of wealthy men, the same sinister oblong appeared. I never knew exactly what Tarrant had to do to turn over the money. All I know is that it was done. For, that evening, he seemed to breathe easier; there was a little color in his cheeks, and he even cracked a very poor joke.

But my fears for Jessica were not allayed. What Dickson had said stuck in my craw. She knew too much; so did I, for that matter. But I wasn't worrying about myself.

NOR did the terror that swept New York abate. By evening of that day no more newspapers appeared. The staffs had deserted en masse. During the day hundreds more had flamed to hideous, screaming deaths, always in the open streets, always in full view of scores of horrified, helpless people. There started a mass migration, the greatest in the history of the city. Men and women fought frantically to get out of town. The railroads were jammed, every automobile road was filled with struggling, fighting, tearing humanity. People died unnoted in the crush; no one was any longer human; all instincts were submerged except the solitary one of self-preservation. The Flaming Death was on every one's pallid lips; a single outcry created a new stampede.

The children suffered especially!

Inspector Byrnes had sent out strict orders to his men to seize any child found near the scene of a human torch, to bring him in for questioning. It was easier said than done.

No one knew where the next blow would fall. Always there was a mad rush away from the ghastly spot, and by the time the police appeared, only the crisped body of the tortured victim remained.

But once a daring policeman happened to be present. Sure enough he saw the inevitable child, a little boy of mine, gloating in a nearby hallway. He grabbed at him. The story was later told by a wild-eyed, shaking onlooker. The child had squirmed under the big hand. Suddenly the officer loosed his hold, staggered back with a great outcry. The next moment he was a mass of soaring flames. There were two screaming, burning pyres instead of one.

After that, even the bravest of men steered clear of every little boy or little girl who happened to be seen in the streets.

On the third day the fearful tragedy grew in dimensions. Parental love—the most powerful and most altruistic of all human emotions—gave way to the prevalent madness. It was now definitely established that somehow, in some inexplicable fashion, these mere tots were involved in the grisly horror that had invaded New York. Mothers who would have died for their offspring, fathers whose whole ambitions had been wrapped up in the future of their young, now looked at them askance. No one knew whose child might be the next to bring torture and flaming death to his elders.

Suspicion grew to panic, panic to utter madness.

Who started it, no one ever knew. But the cry arose, spread. "All children are accursed!" The parents succumbed to the horror. In unleashed fear, with blind cruelty, they thrust their erstwhile beloved ones out into the streets, barred doors and windows behind them, cowered and trembled in the semi-darkness.

The bewildered youngsters cried and wailed on innumerable doorsteps, pleading heart-brokenly for admission; their tiny minds clouded with primeval terrors. But the shivering parents hardened their hearts and threw missiles at them from the safety of upper windows, bade them begone.

Huddled, frightened, not knowing which way to turn, the tots sought the safety of their own kind. Little groups grew in size, merged to form great bands. They roamed the streets, crying, begging those adults whom starvation or fear still forced to hurry through the streets, for food, for shelter. But strong men fled at their approach, panic emptied the streets as they toiled wearily along.

Little boys, little girls, innocents, cast out, driven by the demons of superstitious terror, of universal panic!

It was heartrending to watch them from our vantage point on the upper floor. Their wails grew weaker and weaker as sun and hunger and thirst took their toll. Yet no one dared help. How could they, when it was not known whether some of the true fiends had not insinuated themselves into the wandering groups of innocents, awaiting their opportunity?

EVEN Inspector Byrnes, on that third day, shook his head wearily. He had come to get from Tarrant the story, once more, of how the blackmail money had been paid over, seeking a clue. There was none. "It sure tears my heart out, Mrs. White," he said gruffly to Jessica, "but what can we do? Not one of my men would touch any youngster with a ten foot pole."

Jessica was decidedly thinner now. The dreadful terrors of the past three days had taken their toll. Yet she had steadfastly refused my pleas to quit town. "I can't leave Uncle Jim alone," she averred, "especially after the servants have deserted in a panic. He needs me, poor old man." But her cheeks grew hollow and her eyes clouded with gnawing fear. Now they flamed angrily at Byrnes' words. "Big husky men," she exclaimed, "afraid of those little darlings, watching them suffer and die without lifting a hand!"

A great band had just swung around Eighty-seventh Street into Park Avenue.

They filled the sidewalk from end to end, spilled out into the street. They staggered wearily along, dragging their sore feet, their voices hoarse from begging an alienated, heartless world to take pity on them.

"I can't stand it any longer," Jessica cried suddenly, and fled for the stairs.

"Here," I shouted in alarm. "Where are you going?"

But she was already in the butler's pantry on the ground floor, rummaging.

"By God!" swore Byrnes with a certain admiration, "she's going to feed them."

My muscles released from their first paralysis. I raced after her, taking the winding steps two at a time. For three days I had held her in the house, guarding her sleeplessly against the inevitable attack. Of all New York, a deep instinct had warned me that the hidden monster who had unleashed this madness, had marked her for destruction. Myself as well, perhaps. And now she was voluntarily delivering herself into the hands of those who lurked outside, waiting, waiting....

"Jessica!" I cried frantically. "Wait! Don't go—"

She may have heard; she may not. But the bang of the front door was a triphammer crashing on my heart. I whirled, catapulted after her.

She was out in the street, calling on the milling band—there must have been over three hundred in it—waving in her slender hands loaves of bread, a huge round cheese. They stared at her a moment like shy wild beasts; then, with a clamor of hoarse little voices, they swarmed around her, tearing at the bread with greedy paws, clambering over her central figure for the luscious cheese she still held aloft.

Even as I raced for her, wild anxiety hammering in every vein, I noticed one little girl. She was in, but not a part of, the childish horde. Her sallow lips were not tear-streaked; there was an air of malicious stealth in the way she sidled through the hungry, maddened waifs toward my wife. I had seen that same rapt, gloating expression on the little boy in Cliff Street. Her left hand was invisible, bulging in the pocket of a thin jacket that she wore.

Horror exploded in my brain. Already the little girl had pushed her way through the outer throng of squirming children, was coming closer to my wife.

With a shout of warning I hurled forward. Yet even as I sprang, I knew that I would be too late; that never could I reach that little fiend before she had done her loathsome work.

I HIT that screaming horde like a battering ram. I tossed the squalling youngsters to the right and left. The little ones cowered, then screamed and clawed at my hurtling body with vicious little hands and feet. They had become creatures of the wild; reversions to the beasts.

Jessica turned a startled face in my direction. But even as she turned, her eyes widened, filled with a terrible fear. She had seen the child, had surmised the full horror from her evil-twisted little countenance. In desperation I took off in a low, smashing dive. The squalling horde of little folk gave way with high-pitched pipings of terror. Jessica was backed up against the wall of the next apartment house, pinned in by swirling, screaming children, unable to move.

Somehow my clutching fingers caught at the thin jacket of the little devil just as her fist bulged in its pocket. I jerked savagely. The jacket ripped.

Someone screeched, a high, queer animal scream. Madness, terror, stampeded those children. In seconds I had clambered to my feet, alone in an echoing street, staring stupidly at the fragment of cloth in my hand.

The girl from whom I had torn it was gone; all children were gone. Only the diminishing rush of little feet, of thinning screeches came to my ears. Had I said all were gone? I was mistaken. Before my very eyes an unrecognizable little form was twitching on the ground, its body still enveloped in the hungry fires. My wild jerk had swerved the aim of Satan's imp, had brought horrible death to an unknown waif while Jessica had been saved.

Jessica!

I started, shrieked out the name. The canyon walls engulfed my cry, sent it back muffled, mocking. Jessica was gone too! While I had staggered to my feet, while the children had stampeded, Jessica had vanished.

I raced into the adjoining hall. It was ornate, elaborate, in keeping with the expensive apartments above. But it was empty. Whoever had lurked in its corridors, waiting just this chance, had had plenty of time to seek his lair with his prey.

My feet beat a desperate tattoo out into the street again. There Inspector Byrnes, eyes narrowed, caught up with me. A gun glinted in his hand. His gaze shuddered away from the poor little motionless body. "Where's your wife?" he gasped.

"They got her," I said dully. "They were waiting for her to come out. Perhaps they even led those children to parade past, to lure her out."

He swore, slowly, with feeling. "By damn! She must still be in this building, then. I'll get a squad, search every room, every cranny. I'll get her back for you." With that he spun on his heel, raced back to Tarrant's duplex, to phone.

I watched him go with ashes in my heart. Already, I knew, the monster had whisked her away. There were half a dozen exits on different blocks. I started to run after the Inspector, to tell him so; thought better of it. A wild thought wormed its way into my brain. After all, what did I know about Byrnes? Why had he taken such an interest in the case of James Tarrant? Other men, of more wealth, had been threatened, yet he was always around when trouble started. I was pretty close to insanity just then.

Then my thoughts grew even madder. Tarrant had insisted we come to New York. Why? He had not seen Jessica for years; ever since he left the Midwest. And among the people with whom he had surrounded himself there was not one whom I could trust.

I hunched my shoulders, mumbled to myself. My hands were outspread claws; madness gnawed at my mind. I would find Jessica alone; kill the one responsible for her abduction with bare hands. I started on a shambling run. Old Jem's—the black-robed shopkeeper's—where human heads adorned grimy windows and nameless instruments of torture gathered dust on shelves—that was my destination.

HOW I got there I never knew. My brain was a welter of insanity; my feet moved of their own volition. There were no subways running, no taxis. The streets were empty, left to the Horror that stalked with sudden flaring death.

Suddenly my senses returned. I found myself leaning against a tight-shut warehouse wall, gasping for breath; tired—very tired. But just in front of me was a grimy window, hiding within its depths macabre secrets.

And Jessica?

I lurched forward with a cry. I was just an unthinking animal seeking the mate who had been reft from it. I had no other thought, no saving caution. So it happened that I did not notice the figure who had been dogging my staggering footsteps this past several minutes; I did not see him slink closer and closed.

The door of the shop was blankly dark. I lifted knuckles, pounded savagely. "Open up, damn you! Give me back Jessica!"

But even as my knuckles bruised, I heard the pad of approaching feet. Instinctively I half turned. The man was almost on top of me. He stiffened at my sudden swerve, lurched to a halt almost at my side. His right hand was hidden in his coat pocket.

I sucked breath sharply, lifted my fist. A flame of fury overcame me. It was Ambrose Twombly, fat, paunchy, panting. His shifty eyes widened with alarm. "Look out behind you," he screamed.

I laughed horribly, started to spring. That trick was old as the hills.

Then the back of my head exploded into a million rushing stars. As the night of oblivion folded around me, it seemed that Twombly was running as fast as his fat legs could carry him! It seemed also that I heard the screech of tires, and a loud report, as if a tire had blown out....

"OKAY, White! You're all right now!" The voice sounded familiar, ripped through the pain that blasted at my head. I opened my eyes, looked blearily around.

I was lying propped up against the tight-shut and padlocked door of old Jem's shop. Inspector Byrnes was staring down at me, grinning. The gun in his hand was still smoking. A police prowl car stood at the curb, its engine running. Two blue-coated men were lifting a limp body into the seat.

"Wh-what happened?" I gasped.

"Saved your life, I suppose," Byrnes grinned with satisfaction. "But better still, I split the case wide open, got the man responsible for the Terror. There'll be no more human torches; no more blackmail!"

I sat up abruptly, heedless of the clotted blood on my head.

"Who was it?" I gulped.

"Ambrose Twombly!" Byrnes said with satisfaction, and jerked his thumb toward the limp form in the car. "I suspected him right away, from his old record. A cheap grifter gone haywire, trying for big business. I had my handwriting experts check up on the blackmail notes. We had samples of his writing in our files. The printing gave him away. For he had a queer habit of always printing his capitals instead of writing them in script. They tallied exactly. I was waiting for the last confirmation when your wife ran out on us. When I got back to phone, Twombly too was gone. He had skipped just as I suspected."

The Inspector's smile widened. "I sent out an alarm, then thought of you as well. I remembered your obsession about poor old Jem, hustled down here with a couple of men. Got here just in time to find you lying dead to the world on the ground, and Twombly running like hell. I yelled for him to stop; he pulled a gun, and I let him have it. He confessed writing the notes and collecting the money just before he died. Everything's washed up."

I struggled dizzily to my feet, shook my head. That smack on the base of my skull had not helped me collect my thoughts. Yet I felt a vast, overpowering relief. New York freed from the madness that had overwhelmed it for days; life once more normal, Jessica....

"Jessica!" I cried weakly. "I forgot my wife! Where is she?"

Byrnes clapped me jovially on the shoulder. "Don't worry about her," he assured. "As long as we got the Master Mind, she'll come through okay. No doubt my men have already found her. I left orders for them to fine-comb the neighborhood."

BY this time my brain had cleared.

There were certain discrepancies. That blow had knocked me out, for instance. Twombly had not hit me; he couldn't have. And Twombly had been in Tarrant's house while Jessica had been seized. He couldn't have gotten out fast enough to do the trick. Furthermore....

"Did Twombly confess to the torch murders, and how they were done?" I demanded sharply.

The smile wiped off the Inspector's face.

"N-no," he admitted slowly. "Can't say as he did. He died just as he confessed to sending the letters and where he hid the swag. But it musta been him, all right. Who else—?"

"Remember what Dickson, Tarrant's assistant superintendent, said?" I broke in excitedly. "That the blackmail stunt might have been a mere horning in by someone who saw a chance to take advantage of the Horror? That would fit Twombly right enough; a cheap con man who saw plenty of money ahead in the universal fear. He hadn't brains enough to start the thing himself. What did he know about this mysterious principle entrusted to devils in the guise of little children, that causes human flesh to bum like gasoline-soaked rags?"

Byrnes shifted uneasily. "He must have!" he declared without conviction. "Who else—"

"Old Jem!" I said emphatically. "We trailed that first kid here. And Jessica is in there now!"

Brynes lost his hesitancy, laughed out loud. "There you go again, blaming poor old Jem. He's a harmless moron, I tell you; couldn't plan a stunt like this."

"Nevertheless," I retorted stubbornly, "I want his place searched."

Precious minutes went in argument over that. Byrnes yielded.

The place was dark within, musty; as if it hadn't been used for years. The policeman searched around half-heartedly, obviously a bit leery of the gruesome trophies that filled the shop. But there was no sign of Jem; no sign of any exit or hiding place.

We were out in the street again. I was baffled, beside myself with helpless futility. Somewhere Jessica was captive, under torture, dead perhaps....

The policemen clambered into the prowl car, shoved the dead Twombly callously aside. "Better come with us, White," Byrnes advised. "I'll bet your wife's on her way to headquarters right now."

I jumped on the running board. "Okay!" I said loudly, "I think you're right. I made a mistake about this place."

"That's the ticket," Byrnes agreed heartily, as the car picked up speed and skidded around a corner. "But get in; we'll crowd a bit."

I jumped off just then, landing stiff-legged on the street. "Hey! What the—" yelled the inspector, leaning out, red-faced.

But I waved my hand and ducked into a little alley, kept on going. I had a plan, and the police didn't fit into it.

I raced through to the other end, whirled a corner, found myself again on River Street, on the farther side. I slid into a hall, settled myself down to watch.

IT seemed like hours; it must have been only minutes. A few men hurried by, scared, ready to run at a shadow. A policeman walked warily in the middle of the street, gun hand close to his holster. Then again silence, while the broken door sagged cavernously into Jem's curio shop.

I was just giving up all hope when a boy of about twelve came furtively down the street. He was older than the others I had seen, and his face was sharp with premature evil. I huddled into the shadows just in time. He had glanced swiftly up and down the deserted street. No one in sight. Then I saw him hesitate, puzzled, at the broken door.

He looked both ways again, bent, and—I rubbed my eyes. He had vanished; even as the first boy had vanished.

Fear pumped my heart; my skin was ridged with cold. Yet I sidled along the walls of the warehouse until I reached the very spot where the boy had disappeared. It was a little to the left of the door, directly under the grimy window.

Recklessly, crazily, on hands and knees, I pawed along the solid panel of the store front. I had to solve the mystery; it was my last chance to save Jessica from the horrors that awaited her.

My thumb caught on a little bulge, pressed. Blackness yawned suddenly before me. A sliding panel had opened. With a fierce exultation I lowered myself into the cavity. There was another whir. The panel had slid shut behind me. But as it did, a dim light glowed. A hooded electric light actuated by the closing mechanism.

It revealed a passageway leading deeply down. I took it, panting with anticipation. On and on; then suddenly it slanted upward. I crept slowly up the grade, making no noise. For a new light glowed directly ahead—baleful red through a narrow slit.

I knew where I was. The tunnel had gone directly under Jem's shop, had burrowed its way into the abandoned warehouse to the left. I clenched my teeth. I was approaching the very lair of the Terror that had gripped New York!

A door barred my way. The red flame streamed through a narrow opening. I crouched as I heard voices. One was harsh with rage, unrecognizable.

"That damned fool Twombly almost wrecked the whole scheme," it snarled. "A two-bit crook, trying to chisel in on things he didn't understand. You sure the cops got him, Jem?"

"Positive, Master," quavered another voice. Unmistakable, that one! "I saw the police shoot him down. He crumpled fast.

But I had to duck inside and take the secret passage behind the false shelves, and leave that feller, Rodney White, outside."

The first voice swore. "You make a mess of things, Jem. Your idiot mind can't think of more than one thing at a time. You should have dragged him in."

"Yes, Master," whined the half-wit. "But maybe everything's just as well. White is dead, no doubt, from that smack on the head. And Twombly will be a swell fall guy. The dumb cops will be sure he was the Master Mind in back of everything. And since we've accomplished our purpose, and intended anyway to call a halt, they'll be doubly sure it was Twombly. I've demonstrated to your satisfaction that I spoke the truth, haven't I, Your Excellency?"

I started, almost gave myself away. The new voice that filtered through was precise, calm, impeccable. Count Lockhorst!

"I think I may safely say you have succeeded," the foreign agent admitted. "Your invention will prove of incalculable value to my country. Think of it—London, Paris, every great city on the Continent, in the grip of the Flaming Death. Thousands of children, hypnotized by a tool like Jem, lured into his net, carrying the tiny mechanism through populous streets. A touch on the spring, and those strange rays you call the Z-Ray impacts invisibly on the proposed victim, fuses all organic matter, including the living cells of the body, to incandescence. Why, within a month, all Europe will be at the mercy of my country."

THE first man laughed disagreeably.

"You wouldn't believe me before." Count Lockhorst said coldly, "A million dollars is not turned over to an inventor simply on faith."

"Well, give it to me now."

"Just a moment. There is this young woman. She knows too much. What will you do with her?"

"Leave her to me. She butted into something, and she'll take the consequences."

I heard Jessica's wild scream.

I had been crouching against the door, my brain churning with horror as the brutal plot unfolded. My muscles moved of their own accord. In a red haze I jerked the door aside, catapulted in.

Two men whirled at my smashing entrance. Count Lockhorst, tall, carefully dressed, monocle firmly fixed in eye. He was opening a small leather bag. I caught a glimpse of green bundles of money. Jem, in his outlandish robe and high-crowned hat, bobbed with jaw agape.

But the third man had his back to me. Something glinted in his outstretched hand. A shining tube, no bigger than a penny whistle. At the anterior end it swelled to a metal bulb. He aimed it directly at my wife.

She was stripped to the waist, bound helpless to a chair. Her clothes hung in tatters about her, displaying her lovely rounded breasts, the white glamor of her legs. Her eyes clung in stark terror to the tiny weapon.

I saw the bulb compress just as I lashed forward. Jem screamed idiot warning; Count Lockhorst's hand fell away from the bag, caught at his pocket. I struck the Master full tilt, knocked the little tube from his grasp, sent him hurtling against the wall.

"Rod, darling!" sobbed Jessica hysterically. "I knew you would come."

But behind me a gun crashed. I felt a stab of pain across my side where the bullet had plowed. White-hot agony it was. I flopped to the floor with a groan.

"This unlooked-for intrusion makes it perfect," Count Lockhorst said coldly. "He is the last one who could possibly trace us. Get him, Jem!"

But the man I had hit wobbled to his feet. His face was a snarling mask of hate. He lurched toward me. "I'll torture him bit by bit," he howled. Jem rubbed his withered hands with glee. "Let me help, Master," he chuckled.

I groaned, rolled convulsively. It was not all acting. The sight of the Master Mind, the inventor, the monster who had staged horror in New York as a mere demonstration, had the effect of a stunning blow.

He was Bayard Dickson, Assistant Superintendent in Tarrant's factory!

HE came toward me with licking lips and gloating face. I groaned louder, rolled again, kicked surreptitiously at the devilish tube where it had fallen unregarded. I uttered a desperate, silent prayer. If only the spring had caught; if only I could aim it right!

Dickson was almost upon me when a wild scream filled the small, pine-boarded room into which I had penetrated. Old Jem leaped high into the air, beat at himself with clawing hands. Then suddenly he was enveloped in flame; inextinguishable, leaping. The others swerved at his tortured cry.

In that moment's respite I hurtled to my feet, slammed a swift right to Dickson's jaw, lashed out with furious hate at the foreign agent who had spoken calmly of devastating Europe. They both went down with sodden thumps.

There was no time to lose. Jessica's despairing cries smote my ears. Jem had flung himself in tortured blindness against the flimsy panels. They gave, and immediately flames flicked up, exploded into roaring blaze. In seconds the warehouse was a seething inferno. I learned afterwards there had been cans of alcohol stored on the outer floor.

I raced to my wife, tore at her bonds, lifted her fainting body in a frenzy of haste, staggered into the tunnel just as the walls of the torture chamber collapsed on the three men within.

I beat the flames to the street by bare seconds, fell into Byrne's brawny arms. Behind, the gaunt warehouse was shooting fire to the sky. "The children!" I gasped. "They're inside!"

The Inspector squinted, shook his head. "They've burnt to a crisp by now," he said soberly. "And maybe they're better off, after what they went through."

I looked back, shuddered. Jessica, covered with a patrolman's coat, squeezed my hand. "They're all destroyed, Rod," she said, "invention and all. Thank God the world is free from such a nightmare possibility."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.