RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

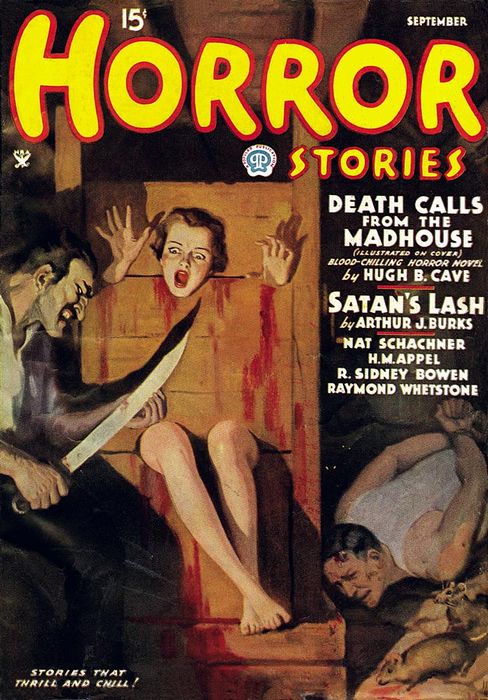

Horror Stories, September 1935, with "City Of The Scarlet Plague"

Into a dismal city where grey-cowled creatures of plague left scarlet-spotted bodies in the gloom of night, came the tramp. He was a railroad bum, hungry and broken—a ready dupe for the terrible purpose of the pest-monsters who decoyed him into the house of Dorothy Burgess....

I DID not know the name of the city through whose deserted streets I slouched hopelessly that grim autumn evening. It was eerie enough in all conscience, what with the dark, sullen tide whose farther shore was hidden in rain-spattered fog, and the dilapidated, crazily leering warehouses that flanked the waterfront street on whose broken flagstones my weary feet tapped out sounds like thunderclaps.

The fine, sifting drizzle seeped through my threadbare coat, turned up at the throat to hide my collarless condition, as if it were so much tissue paper. I shivered with cold and with hunger. For two days I had been immured in the depths of a freight car, without food or drink, trying to beat my way West where perhaps new life awaited me. Once I had had money and friends and a girl I thought I loved, but now—Well, to be honest, I don't blame the brakemen who thrust me off the moving train by the light of their lanterns, to the accompaniment of many oaths.

I had no idea where I was, within hundreds of miles. It was night, and what seemed a fair sized city stretched away from the glistening tracks and the turgid, strong-running river. I had stumbled to my feet among the railway cinders where they'd thrown me, and had wandered, shivering, down the nearest street. I think even then a premonition of what hung like a miasmic cloud over this unknown town must have penetrated my being. For, though the street lamps glimmered in frozen haloes of grey fog-smoke through the slanting rain, no lights sprayed cheerful illumination from the eyeless houses, no human forms paced hurriedly along the streets, no automobiles hissed with wet tires over asphalt.

For the moment it stopped me short; I mean the vast, stealthy silence that blanketed the town. Strange, crazy phrases pieced themselves together in my mind. A city of the dead! A town whose soul had ebbed away in fear. A place of desolation and unspeakable things! I laughed a bit shakily, and the unexpected sound was like ghastly mockery in that deathly stillness. It is because I am weak and feverish that I have these silly thoughts, I said to myself. Every city looks strange and somehow ominous at night; every town inhabited by respectable, hardworking people clothes itself in sleep and blessed quiet during the hours when the earth's pulse is low.

Respectability! I laughed bitterly. I was an outcast—outside the pale. The mist swirled around me, freezing me to the marrow. I could not stand here forever or I would die before morning.... Hunching my shoulders forward, I went down the waterfront street, seeking an open door in those musty fronts where I could shelter myself against the rawness and the wet—and I was hungrier than I had ever been before.

But all doors were barred and sullen against intrusion. I stumbled on, still seeking. Then it was for the first time that I knew I was being followed. I had just paced hopelessly past the flare of the fourth street lamp, when the long oval of wet-gleaming flagstone in front of me became obscured with grey shadow. My eyes clung to it even as my feet missed a beat, and then resumed their slow shuffle forward.

It was a fantastic shadow, blurred at the edges with irradiating globules of rain, grotesque in its foreshortening, hunched over like an evil dwarf with high peaked hat and horrible similitude of groping, clawing hands. It stopped when I did, and flowed on with even pace when I moved again. Then the flare of the street lamp was gone, and the shadow elongated suddenly and merged into the engulfing blackness of the dim-seen pavement.

Yet I knew that the Thing or being had not departed. It was still behind me, following stealthily, inexorably. I laughed suddenly aloud. What had I to be afraid of? To all outward seeming a bum, flotsam of the waterfront, anonymous spawn of the city—what had I to fear from skulking creatures of the night?

NEVERTHELESS my ears strained ever backward. The slow shuffle of my feet was strangely loud, my sharpened senses caught each almost imperceptible hiss of the droplets as they fell, yet not once did I hear the slightest whisper of the Thing behind. I twitched my head suddenly backward. Nothing! Unless perhaps that thicker shadow which seemed to merge with the lowering wall. Nothing! Yet my heart, hitherto a feeble pumping of starved blood, pounded suddenly like a trip-hammer.

I did not look back again. Instead I hurried gasping toward the next street lamp. Light! I must have light! A faint wind ruffled the tattered garment that I wore, a strange, burning sensation pricked sharply at my spine.

I whirled around with a smothered cry, fists balled in fierce anger. Hunger and cold had sapped my strength somewhat, but I still could give a fair account of myself. If the pursuing prowler thought.... My hands unclenched, dropped helplessly to my side. There was no one there. Only the dark, interminable street, misted with drizzle and grey fog.

I shook my head in bewilderment, and I stared wildly around. Blackness yawned out from the open maw of a warehouse not ten feet from where I stood, yet no power on earth could have compelled me to enter that strangely opened door. Fear clutched my vitals. I spun on my heel and ran as hard as I could toward the haven of the lamp. My feet were strangely light, so was my head. The cold had suddenly disappeared from my bones. Molten fire seemed to flow in my veins. A giddiness pervaded my being.

White radiance flowed around me, dispersing the clutching shadows of the night. I grasped at the dingy green lamp-stanchion as though it were a sentient thing which could protect me from nightmare terrors, and in so doing, my wabbly feet collided with something soft and yielding.

For one dreadful moment I stood there, frozen, rigid against the chill, dripping post, afraid to look down, afraid of what I should see. Yet the knowledge clamored through my veins, seared with blinding horror in my brain. That clammy, sprawled obstruction over which I had stumbled was.... With the last expiring effort of my will I forced my weighted eyelids downward.

The man stared back at me with wide-open, sightless eyes. The rain beat senselessly upon his tortured face; a thin, grimy hand tore in the last desperation of death at a blue-mottled throat as if he had literally choked for a saving breath of air. And on his forehead, set in terrible stigmata, were a row of round vermilion spots, red as new-spilled blood, scarlet as the fires of hell.

I lurched away from there in frantic haste. The glow of the street lamp had suddenly become evil, inimical, as it laved the limp, dead body at its base. I started to run again. The strange, silent street seemed suddenly alive with shadows that gibbered and mowed at me. I wanted more than anything in my whole life to get out of this town with its ghastly, scarlet-spotted bodies, and silent, deathly leering warehouses. The fever burned in my veins and the wet flagstones echoed under my pounding feet.

So it was that I did not hear the swift approach of other feet, until the steel-hard hand gripped my shoulder through the thinness of my coat and whirled me around like a top. I cried out in sudden fear and jerked away with a ripping movement. Primeval sounds growled in my ridged throat; without knowing what I did, I bared my snarling teeth as if I were a cornered animal.

"Where the devil are ye running like that?" a gruff voice rasped at me out of the darkness. Then the man moved forward, threateningly, something long and straight uplifting in his hand.

BUT I had seen the glint of metal on the dark blue of his coat, the peaked hat that shadowed his grim, white-staring face, and the sight left me weak and limp with flooding relief. I forgot that, to the stern eyes of the law, I seemed but a homeless wanderer, a slouching bum of the streets; I forgot that my headlong flight from the unmoving thing that lay at the base of the street lamp might give rise to certain uncomfortable suspicions.... I knew only that this blessedly solid, flesh-and-blood policeman would protect me from the crawling shadows that had paced me, that had ebbed silently away at the approach of this embodiment of the forces of law and public safety.

I clutched the down-lunging arm with a fierce, hysterical gesture. "Thank God, officer, you came!" I whispered in a high, cracked voice.

He shook my restraining hand off angrily, held his club poised as if to let it descend on my unprotected head.

"None o' that," he grunted. "Come on, give an account o' yourself, or—" He prodded me around toward the light with the ashen stick.

"There've been things following me down the street," I insisted. "Shadows, people, I don't know what. But there's a dead man back there at the post—and that's why I ran."

The policeman whirled on teetering heels. The nightstick fell from his hand to dangle at the full length of its retaining thong. His face in the glimmer of light was a pale, set mask.

"Oh my God!" he groaned. "Another one, an' on my beat!"

I moved forward a bit. "Come, I'll show yon," I said.

Perhaps it was the molten lava that seethed through my body that made me brave, assured. As I moved, the far-off lamp sent its feeble glow beating around me.

The cop swung back on me. Fear had set its pallid mark upon him. "Not for a million bucks!" he mouthed, and stopped short as if he had been shot. His eyes jerked wide on my face, and in the dark glimmer of their depths I saw the unholy dread of a man who has come face to face with death itself. His beefy jaw dropped with a dislocating snap, the muscles of his cheeks sagged into flabby folds, he jerked his arm over his head as he stumbled back as if to ward off a blow. Thick sounds spewed meaninglessly from his trembling lips.

"For Heaven's sake, man, buck up!" I said scathingly. "You're a hell of a policeman." The fever that roared in my veins had burnt away all knowledge of my present plight. Once more I was that Gilbert Lawton to whom uniformed men saluted respectful greeting as he passed, and at the sight of whose credentials motorcycle cops put their little books away with hasty apologies.

But the officer kept backing away. His eyes were fixed desperately upon my features. Then, with a strangled shriek, he turned and ran down the block, headlong, as if pursued by demons. In a matter of seconds he had rounded a corner, and all sounds ceased. Once more I was alone, and ominous silence shrouded the city, while the heavy fog-mist spattered unheeding against my face, to beat in a frozen nimbus of light upon the motionless huddle up the street.

For a long instant I stared after the plunging back of the fleeing man. What had changed him suddenly into a cowering wretch? What had he seen in my face that sent him stumbling and shivering away from me as if.... as if....

The exaltation of fever dropped away from me. I shivered uncontrollably. Ice crystals formed in my blood, froze the marrow of my bones. My body was suddenly too heavy for my legs. My thoughts whirled round and round in a clogging nightmare. What—had it been that—he had seen?

A strange sensation prickled my skin. I looked up quickly. Then I screamed and shrank upon myself. The darkly silent street seemed alive with shadows. They flowed out of obscure holes in the flanking walls, they moved in shrouded greyness and on whispering feet.

Closer, closer, silent as the grave that had spawned them, terrible as the fog that bore them in its womb, the shadows came—on and on, with deliberate, inexorable tread. I knew now why the city was an abode of death; I knew now what had changed the cop into a shivering wretch. The memory of that still figure with the dreadful scarlet stigmata burned like hot irons in my brain. Death flowed in the street, whispered in the grey obscurity of those enwrapping shrouds. Death that touched, and sent his victim into the gaping jaws of Hell.

SOMEHOW the fear that exploded my skull forced my leaden feet to action. Behind me the long, misty street was bare of shadows, of hooded figures. I turned and ran blindly, gasping, sobbing, feeling the nightmare drag of my limbs, agonized with the knowledge that my stumbling efforts were futile.

A burning cold enveloped my body. My bones dissolved with frozen fire. My lungs heaved with racking pains. The nape of my neck ridged against the expected grip of grave-cold fingers. My steps slowed to a stumbling walk; my wracked body could do no more.

On and on I staggered, slowly, haltingly. Behind me came no sound. Nothing but the scraping shuffle of my own feet. Hope gushed then in a warm flood through my frozen bosom. Had I escaped the strange creatures of the night? Had they abandoned me as too obscure a wretch for their inscrutable purpose?

I looked feverishly back over my shoulder. My head froze into position like that of a twisted doll. Behind me, not ten paces away, moved the shadows. Grey formless blobs, etched out of night and mist and drizzle, holding even step with me, unhurried, terrible in their timeless patience.

Then, for the moment, the ecstasy of ultimate terror lifted me to a certain wild recklessness. I stopped defiantly in my tracks, and shook my feeble fist at them, and mouthed strange oaths. Damn them, whatever they were, creatures of earth or of hell! They were playing with me, inhaling my gasping terror with greedy sibilance, prolonging my agony before the final lunge. Let them come now and get it over with. I was tired of life, of the pain that gnawed with increasing fires at the pit of my stomach. I would not be made into a hunted animal for their cruel sport. I told them so, with the shrillness of delirium; I told them that and much more. My shoutings echoed up and down the street with ghastly mockeries, and rolled futilely back to my very feet.

For the shadowy Things paid me no seeming heed. They came on with worm-like flow; dim, clawing hands emerged from grey mantles, extended toward me in hideous travesty of priests' benedictions. In seconds more those elongated points would touch me.

I backed away quickly. They followed. Then I saw the glint of something long and sharp. With a moan of utter fear I turned and ran again. Wild, uncontrolled horror lashed me on with scorpion whips, whispered frightful things into my ear. Rather I should push my fevered body to the bursting point of heart and lungs and limbs than permit them to wreak their hideous will on me.

I did not hear them, but I knew they were there, keeping step with me, chuckling with unhuman laughter at my feeble efforts to escape.

Ah! Thank Heavens! The long, interminable block was ending. Directly ahead glowed a corner light, marking a cross street. To the right, it led deeper into the city. To the left—and my thudding heart slammed against my ribs—was the dark, strong-running river. A fantastic plan shaped itself even as I forced myself to renewed speed. A swift turn, a sudden dive into the murky, all-embracing waters. Perhaps there I could escape, perhaps I could strike across the tide for the distant, hidden shore, and rid myself once and for all of the doom that enveloped this night-shadowed city. Pneumonia! Drowning! What did they matter against—?

I turned the corner on unsteady legs and clutched at the wet brick wall with a little cry. In front, cutting me off from the rain-glistening water, were looming shapes. Grey forms that came toward me with arms extended and long, steely points in their shapeless hands.

I stopped short, doubled on my tracks. The way I had come was barred. I glanced wildly around. Grim shadows disassociated themselves from the gloomy walls on the third side, and pressed toward me. I uttered a hopeless groan. Despair enveloped me in a moveless casket. I was trapped, surrounded, by these muffled shadows. There was no escape. Soon they would be upon me. What—what fate awaited me?

With an oath I lunged forward. Delirium gave me strength. My fists balled. I would.... The ranks seemed to widen a bit. Then it was that I noticed for the first time the cross street that led into the heart of the city. It stretched straight and firm, spaced lights making a dim glow in the bellying fog—and it seemed empty and bare. With a mutter of thanksgiving I swerved suddenly in my lunge and catapulted for the haven of seeming safety.

I did not know then! Oh God, I did not know!

Behind me drifted a low, rasping chuckle, like ridged waters in the wake of a speeding launch, but I did not pause to consider its dreadful implications. All my burning energies were engrossed on that lane of emptiness. My body, geared to feverish speed, flung along in an ecstasy of hope....

IT was a street of private houses, row on solid row, of dark grey stone and built to repel an army, buttressed with massive, oaken doors. Not a light gleamed anywhere; heavy green shutters were tight clasped against the lonely street. If any one dwelt in their thick-walled depths, if any one heard the clatter of my headlong flight, he made no sign. I was an outcast, a friendless being, abandoned without mercy to the strange creatures who roamed the night.

Then I halted, and groaned aloud the torment of my spirit. It was all over. I had thrust my head into a diabolic trap. From behind the high stoops that fronted each house, new shadows arose and blocked my path.

Shrouded beings in front, shrouded figures behind. Even as I paused, shrinking from expectant contact, they ebbed sideways in a semi-circle. The semi-circle contracted about me with imperceptible tread. The needle points gleamed with hellish luster. Closer, closer!

With a wild shriek I spun and pounded up the stone stoop that loomed invitingly before me. There was no other way for me to go. It was the instinct of terror rather than reason that urged me on. The door was grim and blank; before I could bring help, even if help were there, the creatures would be upon me.

God! Even then I did not know!

I reached the top step, flung my weakened, fire-stabbed body against the heavy oak panels, beat with my feeble fist upon its hard, unyielding wood. "Help! Help!" I shouted to the unseen, unknown inhabitants of that barred and fortress-like house, knowing even as I cried that it was too late!

My blows, my cries, brought no response. The noise muted itself on blank wood, was smothered in the thick fog like a lost voice crying hopelessly in the wilderness. I sagged suddenly, wearily, bracing myself to the silent shapes that should be almost upon me.

My fever-blurred eyes blinked down the stoop in uncomprehending astonishment. For the grey creatures had not moved. They formed a semi-circle in tight enclosure of the stoop, thereby barring all egress from my eyrie, yet they made no forward step to seize me.

Their hooded, shapeless heads bent forward, their hands were hidden within their shrouds. Like a pack of grey wolves they were, encircled around their prey, knowing that he could not escape—waiting, tongues expectant.... for what?

Then I knew what I had done. That arc of silent shadows, terribly expectant, gloating behind their masking hoods, waiting.... waiting.... Good God! I had been herded like a bleating, panic-blinded sheep, herded to the very spot they had marked for me from the beginning!

With feeble defiance I rose to hurl myself down into that waiting horde, flailing with both fists until I died. That way at least was cleanly; not....

The door pushed cautiously open in back of me. I was weak, I was burning with strange fever, so I fell, cutting the back of my head against the sharp edge of the railing. Even as I dropped, limp and semi-conscious, my blurred vision roamed over the rain-misted street. Somehow it seemed to me that the expectant circle of Things had disappeared, had merged into the darker shadows of the farther walls, as if—and the thought was like a hammer blow on my skull—their mission had been accomplished, as if they had done the dreadful deed they had determined upon.

Voices drifted to me in muted rumbling. A harsh, angry voice strangely strained: "Get away from there, I tell you. It's a trick! Quick, before—"

"But I heard someone calling for help, Father. We can't allow a human being to die on our very doorstep because we are afraid."

Was I dreaming or had I really heard the girl's voice? Once I had believed in women, with their soft, gentle-seeming ways and helpless, adoring looks; but bitterly had I repented. Was this another of those, a lovely shell enclosing corruption and death? I remembered the demoniac shadows that had forced me hither like hapless flotsam, and a cold sweat drenched my ague-stricken body. Dread, dread of the harsh, strained voice, of the softer, pity-quivering girl, engulfed me. I made agonized effort to arise, and fell back with a dull thud.

"Father, do you hear that?" Once more sounded the lovely voice of a woman with which Hell's demons know so well to clothe themselves. "You must find out...!"

"Very well," the man grumbled, "but if it's one of those—!" The door edge jammed into my shrinking flesh. As in a haze I saw the blue steel of a gun barrel protrude cautiously above me. Smoldering, hostile eyes peered down at me—eyes socketed in a mask so hideous, so like a carved gargoyle that I shrieked and tried desperately to squirm away.

FOR a breathless second the twisted features leered at my thrashing form. Then those twin orbs, aglow with strange fires, widened into—fear, was it? Terror, even? The man made short, explosive ejaculation. The nightmare face disappeared, and the door slammed inward.

A small, shapely foot thrust into the narrowing space. There came to me the sound of a struggle, of the girl's panting voice: "We can not abandon him like that. Suppose he is a tramp...!"

A tramp! Scum of the earth! I had forgotten what I seemed. I laughed, and the laugh strangled with bitterness. This girl with the lovely voice, this woman who acknowledged that twisted gargoyle as father, this demon on whose doorstep her brother creatures had thrust me, how dared she...?

The grey shadows ebbed away from the shrouding walls of the opposite side. On noiseless feet they flowed forward, swiftly, in terrible, silent rush for the stoop on which I lay, helpless and writhing, before the door that was still held partly open behind me.

My heart stopped beating. My blood thickened with horror. I saw the whole damnable trick now. I had been bait, human bait. The girl, no matter what her father was, was the prey these grey, mysterious creatures sought after. The trap had been sprung. And now....

Already they were half way across the street, swarming like evil embodiments of the fog. In three seconds....

Somehow the tight constriction that held my throat as in a vise, loosened. My voice sounded dreadful and strange in my own ears as I shrieked: "Close the door, quick! They're coming!"

I tried to roll away, to send my aching body crashing down the stoop, catapulting like a thunderbolt into the silent figures that already were masses of grey against the grey stone steps. There was a quick, sharp, answering cry from within, the sound of sudden, gasping struggle, and a white hand thrust out, gripped my shoulder.

Up the steep stone steps the grey horde came, like water flowing uphill, silent as the grave, shapeless as death itself. I struggled to break that grasp. I was doomed, but the girl.... Her grip tightened. My poor body, gaunt from privation and fever, scraped against the sill. My head bumped hollowly, yet I felt no pain. I saw a brown hand, skinny and clawed like a vulture, reach for me. I swear it could have caught my lolling head; there was ample time. Yet, inextricably confused with the thunder in my ears, I thought I heard a swift sibilant whisper, and the hand retracted. The Things in shrouds froze where they were, drifted down the stairs again.

Then I was wholly within the dark of the entrance hall. The oak door crashed solidly into position; there was the quick slide of heavy iron bolts into place. Was it delusion or had I actually heard, just before the barrier slammed shut, the gloating, satisfied chuckle that rose like a foul miasma from the hooded Things of the night?

I tried to struggle to my feet, but my limbs seemed paralyzed. My skin was a hollow husk, buoyed up by a blazing furnace within. I had no bones, no flesh; all had been dissolved into molten agony. My throat was parched, and my brain a fiery torment.

Just then the darkness flared into light. It hurt my clouded eyes; I blinked upward. The man stood directly over me, gun snouting downward. I blinked again to rid myself of nightmare frenzy, but it did no good. He did not change.

His tall, lean form was the form of a man in vigorous middle age, hard and spare and fit. But his face—dear God, his face! Incredibly old, incredibly twisted, and incredibly evil. It snarled at me with lopsided mouth, it leered at me with cracked, leprous skin crisscrossed with a thousand streaks of red. Deep hollows, filled with scar tissue, gouged his forehead.

I thrust my head weakly to one side to avoid the dreadful vision. And then I saw the girl, pressed tight against the door, listening for sounds from without its thickness. Her face was very lovely and very pale, her red lips were slightly apart as the panting breath expelled from her lungs.

The man's harsh burble of words brought my head around again, startled the girl away from the door. All his body was curved away from me in frozen repulsion; his eyes, twin holes of hell, burned on my forehead with ghastly, leaping fear.

"Dorothy!" he screamed to the girl, "get away! He has it! He has it!"

Had what? A mantle of ice quenched the flames in my body. First the policeman had jittered away from me as though I were a thing accursed, and now this travesty, this monstrosity who had once been a man, cowered and shrieked horrible warnings.

ALMOST mechanically my hand crept up to my forehead, to the place where his loathing gaze was rivetted. It fell away with a thud. I knew now what it was. I lay as one numbed—beyond life, beyond death. I had felt the five round lumps, raised in swelling mounds on my skin. Without a mirror I knew their color—vermilion, red as new-spilled blood, scarlet as the fires of hell. The room rocked and swelled around me. I saw once again the body at the base of the lamp post, hand clutched at throat in frozen agony; once more I remembered the sharp stab of pain in my spine. It was all too clear now.

The girl's voice penetrated my frenzy, dissipated the fiery mist that hazed my reason. It was low and very steady.

"It's too late, Father! I touched him!"

"No! No!" I cried with the desperation of despair. "It is not too late. Throw me out into the street, where I belong. You shan't get the plague from me. Get away from the door."

Where I found the strength I do not know, but I crawled on hands and knees, blind with pain, yet exalted with fear for the girl called Dorothy.

"Let him go," the man croaked.

But the girl did not stir from her position. She barred my path, watching my writhing progress with eyes that were brave and pitiful. Only the alabaster whiteness of her face showed her inward suffering.

"It is too late," she repeated. "One touch is sufficient to transmit the plague. You know that, Father." Her hand went up to her throat, her dark blue eyes widened. Then she smiled wanly. "We must get a doctor at once for this poor fellow, for—myself!"

The man's fists clenched until the blood ran from his palms. His gargoyle face was even more hideous in its anguish.

"Dorothy," he whispered brokenly. "No doctor can do you any good." His hands opened and fell limply to his side. "If only I had the formula, if only—" He raised his hands suddenly like a grotesque prophet. "Damn Soloway!" he screamed furiously. "God damn him and blast him to hell!"

"S-sh, father," the girl rebuked him quietly. "That won't help us; won't help all those poor people. Please get a doctor. Perhaps—perhaps—"

But the man did not hear. He pounced upon me, swung me up in arms that were incredibly strong, tossed me like a sack of meal upon a couch in the stately, high-ceiled living room. His eyes glared at me with ineradicable hatred for the doom I had brought upon his house.

"Doctors!" he snorted. "What do they know of this?" He swung on his daughter, his distorted face working with strangled emotion. "I'm going back to the lab, Dorothy, and by God, I'll find the proper proportions this time. I must—I must!"

He flung up the curving stairs that led to the second story of the house. "You'll see—" his voice floated down. Then a door banged shut, and there was silence.

Silence, in which I could hear every shuddering drop of blood in my veins. The girl looked at me a moment with pity in her deep shadowed eyes, then she moved swiftly and steadily to the phone that nested in its cradle on the little stand near the hall.

"I—I'll have a doctor for you soon," she whispered over her shoulder. "Just as soon as I can locate one. We—we are strangers in this town." For the first time this dreadful evening there was a quiver, the hint of a sob in her voice.

Pulsing with pain, wracked with spasms though I was, I watched her slender litheness as she leafed through the telephone directory, seeking at random the name of a doctor. For myself I did not care any more; I was doomed to a hideous death. But to this brave girl, unaccountably the daughter of that hideous distortion who had fled mouthing and raging up the stairs, I had brought, all unknowing, leprous foulness. It was that thought which made me writhe with new agonies and groanings of spirit as her moving finger halted on a name.

She dialled rapidly—and the clicks of the instrument fell into the silence of the room like pebbles in a fathomless pool. Silence again. Then: "Hello," she said, "is this Doctor Hinsdale? Yes...? Will you please come at once to 433 Meadow Street? An emergency case.... Yes, please hurry!"

She dropped the phone hastily into its cradle, as if to cut off too awkward questions. Her hand gripped the table, as she swayed unsteadily. Her face was alabaster white, and her eyes were frozen prayers. Then she saw me lift myself imploringly on my elbow and a wan smile veiled the nakedness of her fear.

"I—I couldn't help it," I said with difficulty. "Forgive me; I didn't—know I had the plague. The grey shadows—those creatures of hell—pursued me, forced me here. If I had known—" I fell back again in a haze of agony.

The girl tensed like a strung bow. "You were forced here?" she repeated dully. Then horror came into her pallid face, pried her red lips open in a choking moan. "God help us now!" she whispered. "There is no further hope for us—for anyone."

The anguish in her voice, her bearing, stripped the torture from my skull, mad? me oblivious to everything but the desperate need of this girl.

"Dorothy!" I cried from my couch, not knowing any other name for her. "Who are they? Perhaps I am as good as dead, but in the few moments left me, if I can help—"

She looked swiftly at me with new expression in her eyes, at the sight of which my heart bounded. God forgive me, a fool who was soon to die hideously. Then she dropped her gaze with a hopeless gesture. I misunderstood it.

"Look!" I cried. "I am not a bum, in spite of appearance. I'm Gil Lawton of New York. I—"

IT was not pride; it was not boasting. But I had been fairly prominent in my day, and that last smash-up of mine had given welcome headlines to the avid newspapers. That was why I had slouched off into the shadows, trying desperately to lose myself.

She had heard of me. I could see it in the quick flutter of her long lids, the sudden lighting of her fear-shadowed gaze.

"I'm Dorothy Burgess," she said, "and my father—upstairs—is Andrew Burgess. You can't help us," she went on with a shudder, "no one can. My—my father wasn't always like what you see. He was a biologist, a scientist. We were in northern India—Nepal—when the red plague broke out. Its symptoms were five red swellings on the forehead, and its end a—"

She choked off abruptly. Even with the constant pain that blasted through my gaunt frame I smiled bitterly. She need not be so careful of my feelings; I had already seen the end result.

"My father refused to flee the country. He was there on a museum expedition, to obtain specimens of certain rare plants that grew only in the mountain fastnesses of Nepal, with his assistant,"—for the moment her lovely face contorted with hate—"Enoch Soloway. My father threw himself feverishly into the work of discovering a cure for this dreadful disease. Day and night he toiled, while the plague devastated the country, made corpse-strewn deserts where once there had been populous villages. At last he found it—a complicated combination of the distilled essences of certain very rare and almost unknown native plants. He tried it out; it worked—miraculously. Recovery was almost instantaneous."

I listened eagerly. Hope flared in me. If that were the case...!

Dorothy Burgess went on tonelessly. "He was mad with joy. He distilled and combined for days, made up a substantial supply of the healing drug. Then—" Again there was that look of hatred on her lovely face.

"Then what?" I prompted. But I knew before she spoke, and I felt suddenly like a lost wretch on the desert whose pool of water has proved but a mocking mirage.

"Soloway disappeared one night, and with him went the supply of antidote, our cultures of the deadly plague bacteria, and the notebook containing all of father's researches and data. The next morning poor dad was down with the red plague. His assistant must have deliberately inoculated him while he slept."

The girl's gaze shuddered away from the tell-tale spots on my forehead, brooded with remembered pain into vacancy.

"Father went through hell," she said brokenly. "But somehow Solo way had overlooked a tiny specimen sample. It was not a full dose. It saved father's life, but it left him—as you see."

I forgot my own irrevocable doom at the sight of this girl who had suffered so much, and who now, because of me, was soon to writhe in frightful torture.

"But why," I remonstrated, "didn't your father make more of the antidote?"

She smiled wanly. "Its efficacy depends on certain exact and complicated proportions. A drop of one essence more or less robs it of all curative powers. The first distillation had been pure accident. And Soloway had taken the work sheets. Oh, don't think he didn't try," she cried. "But it was no use. Even now," she gestured hopelessly toward the upper floor, "he's still at it. There is something else, though.... Why had Soloway absconded? To gain the glory of the discovery for himself? No! For the plague went on until it burnt out for lack of victims. He never published; never proclaimed the cure.

"Father sensed the dreadful purpose in Soloway's twisted mind. As soon as he was well again, we tried to trace him. A rumor here, a vague report there. For months we hunted, and finally followed him to this mid-western city. Just as we came, the plague broke out. We knew then we were right. But somehow he must have discovered our presence. Things happened; strange attacks from which we escaped only by the mercy of God. So we fled secretly to this house, and barricaded ourselves in. Now," she ended with a catch in her voice, "we've been found again."

THE breath was whistling in my throat, my limbs seemed no longer part of me; my skin crackled and scraped over aching flesh. But I raised myself gasping and mouthing. The damnable beast! A city lay helpless and dying at his whim. Only the Burgesses stood in the way of complete success. So he had evoked the aid of grey creatures from hell itself; they had used me as the loathsome instrument of their fiendish plan. I had brought the plague within the house, had infected that brave, lovely girl. Her father, Andrew Burgess, was no doubt immune as a result of his previous attack. I tried to speak, but the words strangled in my throat. Thick, incredible sounds spewed forth. I fell back with a thud.

The girl started forward in alarm. Then a bell jangled, and its sound ripped through the room like a thunderclap. I was on the verge of delirium. I saw as in a fiery mist the girl move toward the door, something glinting in her hand. It must have been a gun. I heard muttered conversation, after which the front door swung carefully open, closed quickly. Bolts rattled home.

But there was a man with the girl now—a short, stocky man who carried a black professional bag. I heard his sharp exclamation as the girl, Dorothy, whispered to him.

"My dear young lady," he protested. "Why didn't you tell me? If I had known, I would never—"

I laughed out loud. At least I thought I laughed, but it sounded more like the gurgling snort of a bull whose throat has been cut. He was afraid, this doctor, afraid of the plague. I had it, the girl would soon break out, but the healer of men was afraid for his own precious skin.

The man started violently at the weird sound I made, and approached me cautiously. His face was sallow with fear, and his jet black Vandyke and dark, bushy eyebrows jutted in bold contrast to the pallor of his skin. His eyes widened at the sight of the dreadful stigmata on my forehead. It was only with an effort that he controlled his shuddering movements. Professional decision came back to him.

"It's pretty hopeless, I'm afraid," he said crisply. "No one yet has been known to recover. That is—" He stopped, opened his bag. "At least I can ease him for a while—maybe...." His stubby, powerful hand came out with a shining syringe. He bared my arm without touching my skin, and jabbed.

"A heroic remedy," I heard the doctor saying. "Strychnine! Poor devil, he was on the point of death anyway. It'll keep him alive a few more hours perhaps. As for you, my dear, you touched him. Within the next three hours you will show signs of the disease. I know of no way to stop it." He paused, grimaced and shrugged his shoulders. "I too—I'm afraid—! Well," he went on briskly, "that's my job. But I'll have to quarantine all of us in here. I'll call my nurse, get her over to help."

He went to the phone, clapped the receiver to his ear, and dialled. A puzzled expression moved shadow-like over his face. He dialled again. A long wait, then he dropped the phone, sucked his breath in sharply.

"The phone is dead," he remarked evenly.

I was awake now, fully aware of everything going on about me. The pains were gone, and I was strangely light. I felt buoyed up, floating. But that simple remark crashed into my consciousness with sickening force. The phone had been all right when Dorothy phoned Dr. Hinsdale; now it was dead. Some time in between it had been cut....

Outside, lurked the grey, shrouded Things, mocking our agony, chuckling over the rapidly approaching completion of their dreadful task. Inside were a handful of the dying, infected and maimed, cut off from the outer world, waiting helplessly for the next move of the plague-carrying hell-hounds of the night.

We stared at each other in a kind of horror. I groped unsteadily to my feet. Blood whistled through my heart, pumping with the temporary drive of the stimulant in my veins. Somehow I knew that within the next few minutes...

Upstairs there was a terrific crash, as of tables overturned. Glass shattered. A gun racketed. The voice of Andrew Burgess, high, piercing, unrecognizable with mingled rage and terror. The thud of a falling body. Then silence, sullen, ominous, more frightful than any noise.

DOROTHY screamed and darted for the stairs. But I was ahead of her, taking them three at a time, buoyed to artificial vigor by the drug in my system. I clenched my fists as I raced down the long, dim hall at the head of the stairs. The devilish plot had somehow been completed. It had started with my infection, with the simple, yet infinitely cunning way in which I had been introduced into the house, and now....

I went headlong into the monstrous being who, one with the shadows, was slipping stealthily along the wall. The breath slammed out of my nostrils as I smacked into him. I staggered back, bruised and puffing, still a hollow shell of my former self.

The grim shape straightened, hesitated in the shielding murk. Then I leaped, snarling in my throat like a ravening beast. I was dying, but this—this dim-seen creature would not live to gloat over his victory. Andrew Burgess was dead, I was sure of that, and his daughter—

As I catapulted forward, the marauder swerved. His face caught a glint of the filtering light from the lower floor. The roar of rage died in my throat. Involuntarily I checked my stride. Cold sweat broke out over my lunging body. The face that leered at me seemed no human countenance. One ear was gone, as if ripped from its roots. The lips were forced back from dead-white gums in a hideous, perpetual grimace. The nose was a swollen polyp, bulbous with raw flesh.

The monster moved its hand. Great God in Heaven! It was the shrivelled claw of a fleshless corpse—and its scaly talons clutched a bar.

I screamed and lashed out weakly. The creature snarled malignantly as my fist sank into its stomach. The bar lifted, crashed down. I ducked, but not enough. It glanced off the side of my skull, and I went down, writhing with pain and renewed agonies.

I heard Dorothy's scream: "Mr. Lawton—Gil!" Then she was kneeling at my side, her dark blue eyes pools of fear.

"Don't come near me," I panted, half mad with the fever that burned again in my blood—and with helpless rage. "Tell Hinsdale he went down that way—before he escapes."

"Who?" demanded the doctor. He came bustling up behind Dorothy.

I lifted myself with infinite effort, held myself with spread hands against the wall. The girl had drawn back, remembering, seeing the scarlet plague writ large on my forehead.

I shuddered. "I don't know," I muttered vaguely. "A monster, a creature out of hell, a thing unspeakable. He hit me and ran down the hall."

The doctor was braver than I had thought. Without a word he scurried down the dim recesses, came back grim and quiet.

"There's a stairway that angles down in the rear. It's pitch black. Perhaps—"

"Father!" Dorothy shrieked suddenly. "What's happened to him?"

She turned and ran back to the door on the right. The doctor was at her heels, his black beard wagging. I followed slowly, staggering, barely able to keep myself upright. There was no answer to the poundings of her slim hands. Hinsdale put his shoulder to the door, went catapulting in. We followed.

THE room was acrid with gun-smoke.

I saw that it was fitted up like a laboratory; that a table lay sprawled on its side, and that oily chemicals were flowing sluggishly across the floor.

Dr. Hinsdale ripped out an angry oath and darted toward the table. He was brought to a spraddling halt by Dorothy's scream. She had seen the sprawled, unmoving figure of Andrew Burgess.

Hinsdale jerked around, knelt swiftly at the side of the silent man. His face was pale with some terrible fear. He worked feverishly and silently. Burgess stirred under his ministrations, sat up slowly. Blood streamed from a gash in his scalp. Hinsdale took a deep breath. The color flooded slowly back into his cheeks.

"That was a close call," he remarked. The gargoylish face of the scientist did not seem to take him aback.

Burgess looked vacantly around a moment, as though he did not recognize us or his surroundings. Then he jerked to his feet, panting, glaring madly at the window.

"I saw him," he mouthed. "Out there, outside the window, peering in at me. Like a monstrous toad. I ran for my gun. By the time I got it he had smashed the glass and jumped into the room. I fired and missed. Then something hit me and everything went black."

"Who was it?" Dr. Hinsdale snapped.

Burgess looked fearfully around before he answered.

"Enoch Soloway!"

The name of course meant nothing to the doctor, but Dorothy gave a little gasp and sank weakly into a chair. I stood rigid, pulses beating like trip-hammers all over my body. Then I rushed to the window, looked out through the splintered frame.

A broad stone ledge extended out some twelve inches. The adjoining house was dark and shuttered, and an eight-foot well lay between. But a very active and very desperate man could have jumped from the roof, across the intervening gap, and landed precariously on the ledge.

FOR a long moment the smoke-clouded room was a tomb of despair. Burgess had sat down again. The blood trickled unheeded down his cheek; his twisted face was dark with torment. Dorothy was rigid as stone, and her eyes were masks of fear. The doctor stared from one to the other, as if puzzled, then down at the spatter of oils that widened slowly over the floor.

The acrid odor of mingled chemicals and gun-smoke hit my nostrils. The effects of the strychnine were wearing off. My throat was hurting, I had difficulty with my breathing. I knew what that meant. I remembered the dead man who had torn at his throat before he died. I could feel the grim progress of the plague as it enfolded me. Within an hour or two I would be dead.

Strange how the thought affected me. The thing that was me would blank out of existence, as though it had never been. That did not bother me nearly as much as the thought of Dorothy.... The plague was upon her. How could she escape it? I searched her smooth white forehead a thousandth time for the telltale stigmata. Still no signs. A wild hope thrilled through me. Was it possible—? Then I thought of Enoch Soloway lurking somewhere in the house and the burning fever in my veins was suddenly ice. The plague was inside. Dorothy could not escape; no one could escape.

I might be nearly dead—yes. But before I went I would take Soloway with me, give the girl her last chance for life. I clenched my teeth till the blood ran from pierced lips, and groping blindly away from the wall, staggered toward the door. Dorothy jerked out of her stupor, crying: "Mr. Lawton—Gil—where are you going?"

"After Soloway," I croaked. My throat was hurting like hell, tightening, as though clutching fingers throttled me. I had only a short time left.

Dr. Hinsdale sprang suddenly to the door, blocking my path. "You fool," he ripped out, "you'll die before you reach the bottom step." His eyes roamed around the room from under bushy black brows. He frowned. "I don't quite understand, but this Soloway seems to be dangerous. So I suppose," he shrugged his shoulders and his eyes glinted, "it's up tome."

Then he was gone, slipping like a cat out of the door before he could be stopped. I heard his swift movements as he went down the black pool of those back stairs.

I groped my way over to the window, taking care to keep as far away from Dorothy as possible. "He is a brave man," I said.

My throat was closing up. I could feel dull knives hacking at my larynx. Soon I wouldn't be able to talk. For the thousandth and first time I fastened desperate eyes on the girl. Good God! It wasn't so; it must be delirium, it must be the haze that still clouded the room! Everything whirled around me. I stumbled forward, mouthing sounds that ripped my throat to shreds.

Burgess sprang to his feet in alarm. Dorothy's eyes widened on me. "Great Heavens, Gil! What's the matter?"

With a tremendous effort I forced the words out: "The spots! The spots!"

Burgess leaped for his daughter in one bound. His eyes devoured her forehead, and hell flamed in them with unhuman fires. He staggered back, clutching his own temples. A great sob racked his frame.

The girl swung fearfully from one to the other. The five round spots, large as dimes, still only faintly red, were unmistakable now. The plague was upon her!

"What—?" she commenced, when she was interrupted by a scuffling noise, followed by a frightful scream. The scream reared itself into the frozen air, and choked off abruptly.

Paralysis gripped us all. That had been Dr. Hinsdale! He had found Enoch Soloway, and must have died—horribly. Even now the misshapen monster was gloating over his victim, was crouching down in the Stygian lair of the cellar, waiting....

GOOD God! What could we do? Burgess was back in his chair, watching me with sudden childish merriment. His twisted countenance lit up with gruesome glee. Meaningless sounds babbled from his lips, and his hands plucked spasmodically at the hem of his coat. I stared at him in horror. The man had gone mad; his mind was a shattered, ruining wreck.

Dorothy's hand explored her forehead fearfully, dropped with a little thud to her side. Then she slumped over, limp and moveless. I was the only one left, and I was a hollow, plague-rotten husk. I gritted my teeth and went for the door. This time, I swore, I would....

I fell back from the gloomy well of the hall, stumbling in my haste. The cry that rasped my swollen throat was unuttered. My teeth chattered with frozen madness. It was too late.

The shadow creatures were in the house!

They flowed into the room, shapeless and grey, their hidden feet whispering over the bare floor. They slipped along the walls, forcing me back with the horror of their coming. Two placed themselves at either side of Burgess. He plucked unceasingly at his coat and paid them no attention. Two others guarded the unconscious girl. I felt the window sill pressing against the small of my back. I could go no further. For one wild instant I thought of precipitating myself through the jagged glass, and bring swift surcease of pain to my throbbing body. Then I stiffened as another figure paced into the room. His feet made hollow, thumping sounds, loud as fate in the eerie stillness.

He, too, was enswathed in shapeless shroud and hood of grey, but five dreadful discs made bloody scarlet splotches across the broad expanse of forehead. I stared at him, and felt my reason slipping. Was this in truth the plague itself, walking the earth with attendant train of hell-born creatures, spreading the foul contagion of its breath over a helpless humanity?

Then I threw back my head and laughed wildly, terribly. "I know who you are," I gasped and choked. "You are Enoch Soloway!"

The vermilion-spotted figure turned to me. The others did not move. He seemed to measure me carefully.

"So you know," he said finally, in a deep, muffled snarl. "Then you must also know—"

"That you are about to die!" I screamed, and sprang forward. I had been crafty, pretending limp movelessness, husbanding my failing strength for this last wild leap. Let me but get my hands on the throat underneath that coarse grey stuff and no force on earth could have torn me loose.

But he had been prepared. Two grey-clad Things sprang like lightning to my side, gripped my flailing arms with steel-hard sinews. They bore me back, struggling and cursing, sent me crashing to the floor. I lay there, a huddled, unmoving mass, gagging with pain and violent retchings.

"I would kill you now," said the masked figure, "but it is not worth while. Within half an hour the plague will have taken you. It is not a pleasant death."

I glared up at him, choking, feeling already the unutterable agonies of the damned, but unable to say a word.

"Enough of such scum," the shrouded being went on contemptuously. "We have more important work on hand. Wake up the girl. She must know what's going on."

A grey shadow leaned over, slapped the limp girl's pallid face. The color flared into her corpse-white cheeks; she lolled her head from side to side. Her eyes opened, widened on the dreadful Things that surrounded her. Her hand flew to her throat; her lips parted with unshed screams.

The masked figure that was Soloway chuckled gruesomely. "The plague has set its stamp on your pretty white forehead, I see. That is well." He swerved on the still babbling man. "Now, Burgess," he sneered, "I have a proposition to make. You always were a fool—boasting about true science and filthy rot like that. You could have made millions out of your antidote, but no, you wouldn't do it. You'd give it free to suffering humanity. Suffering humanity, bah! I was smarter than you. Let humanity suffer, and make them pay through the nose to get better." He laughed horribly in the mufflings of his hood, while I writhed on the floor in helpless torture.

"I chose this city with care," he went on. "It's a rich mill town—plenty of men here who roll in money. I gathered a group who weren't too squeamish; I gave them cultures of the plague germs to scatter broadcast. Hundreds have died, are dying. When I thought the time ripe, I caused the wealthy to be inoculated, the fools with money. Then I sent them messages—that only I had the antidote. A half million apiece for their lives.... It was cheap. The first one will pay in the morning—the others as soon as they see it works with him."

He hesitated, then ground out. "I—somehow—smashed the original flask containing the antidote. But I had your notes. I sent emissaries out to get the drugs. I compounded them in the exact proportions, but—" and again he snarled in baffled rage—"a piece had got torn out of the last sheet of your notes. The very last ingredient."

He took a step forward, towered like an evil demon over the silent, twisted man. "You know what it is. You can't make the stuff without the figures; I have it all made up but for that one chemical. What is it?"

Burgess had his head down. He did not answer. His hand plucked ceaselessly.

The plague-master chuckled evilly. "So you won't tell me, eh? Then listen to me. Look at your daughter, the daughter you love. She has the plague; it is stamped on her forehead. In a few hours she dies. You've seen how they die; I don't have to tell you. Give me the name of that last ingredient and I'll cure her—do you understand me, you fool?"

"Don't tell him, Father," Dorothy screamed suddenly. "It's a trick. He'll never let us out alive if you do."

BURGESS slowly lifted his head. His scarred features were more hideous than ever. Then he opened his twisted lips and laughed. Yes, laughed, long and loud and horribly. The sound slashed through my flesh like knives, sent the maggots of terror leaping in my brain. Burgess was mad, wholly, irrecoverably insane.

"Father!" Dorothy shrieked, and writhed unavailingly in the grip of the grey-clad men who held her.

The hooded master of the plague stared down at him one dreadful instant. Then he ground out a fierce oath and swerved on the girl.

"You know it," he spat. "You were in your father's confidence. Tell me, or you die."

The girl faced him unafraid. The color flamed in her cheeks, matching the red of those awful splotches on her head. "I won't," she breathed. "I know I'll die. I know all of us will. It doesn't matter. But your horrible racket is gone. It won't work any more. No one will pay if you can't cure. I know what is in your filthy mind. You won't stop with this town if you get the antidote; you'll do the same thing over and over again."

The man towered over her, hit her across the face. Red marks, like those of claws, leaped where he had struck. I cried out weakly, but could not move.

The girl did not move under that cruel blow. "I won't tell," she said very low.

"I'll torture your pretty body until you'll beg for the plague to work faster," he threatened.

"That won't make any difference in the least," she declared. And there was that in her unconquerable eyes that must have convinced him she was telling the truth.

"Very well," he chuckled suddenly. "You love your father, don't you?"

Fear leaped into her defiant eyes. "What do you mean?" she quivered.

"Just this," he grinned confidently. He seemed sure of himself now. "He may have gone crazy, the doddering fool, so he can't tell me himself, but he's not insane enough not to feel pain. I'm going to torture him until his shrieks ring in your ears, until you are writhing with his clamors for mercy."

"You won't—you can't—" she started frantically.

"Oh, won't I?" he sneered. He snapped out something. At once the two grey creatures who stood guard over the slumped madman grasped him by the Arms. In a trice they had him securely lashed to the chair with ropes they had taken from under their shrouds. The deranged scientist looked up at them vacantly, twitched and slumped unknowing into his former position. He did not seem aware of his surroundings.

The girl strained against her captors in wild fear. "You beast, what are you going to do to him?"

"You'll see in a moment," he retorted triumphantly. "Unless you tell me what I want to know."

"God!" I raged. "Give me but a moment of my old-time vigor, then I could die gladly, willingly." But I lay where I was, writhing like a broken worm, unable to lift myself from the floor, a horror-stricken, helpless witness of all that went on.

The girl shivered. Her face was pale as death; the red spots of hell leaped out startlingly from her marble forehead. A violent struggle racked her slender frame.

"Well?"

"I—I can't," she whispered through dry lips. "Forgive me, father."

The figure who was Soloway howled with baffled rage. "Give it to him, then."

Swift as lightning, a grey demon whipped from under his shroud a huge, curving pair of pincers. At the sight of them Dorothy shrieked quickly: "Stop! I'll—"

But it was too late. The pincers flashed upward and clamped with a cruel snap on the right ear of Andrew Burgess. There was a hideous, crunching, rending sound, and the lobe of ear ripped off in a single bloody gout. Dark blood gushed in a torrent from the raw wound.

THE insane man jerked under the torment, his twisted mouth opened and a bloodcurdling scream of anguish racketed through the room. The girl struggled violently with her guards, her face a mask of dreadful agony; her shrieks mingled with the toneless, unending cries of her tortured father.

"Stop! Stop! I'll tell. Oh God!"

The vermilion-spotted figure said in satisfied tones: "I thought you would.

Quick, what is it, before—" He made a significant gesture with his arm.

The beads of agony stood out on the girl's cheeks. Burgess's toneless cries died down. The terrible vacancy of his madness settled once more on his features.

"It—it's—"

"Don't tell, Dorothy," I cried suddenly. Somehow that last frightful torture had broken through the obstruction in my throat. Waves of shuddering nausea rippled through my frame. With a last grinding effort I had heaved myself erect. I moved forward brokenly, arms outspread.

But I had seen something, and it was that which had given me strength for even this that I was doing.

From the dim recesses of the hall a shapeless, broken thing was crawling. Head down, inching its tortuous way along like a gigantic slug on whose soft body some one had set a crushing heel. But I knew! It could only be Dr. Hinsdale, left for dead in the bowels of the cellar, returning from the grave to avenge his wrongs. In his outsprawled left hand a gun was clutched—the gun of Andrew Burgess—the gun I had looked for in vain.

It was this that had forced me erect with all my dying strength. I must engage the attention of these fiends, keep them away from that slow-creeping death, pushed on by a will as indomitable as my own. I shouted again: "Don't tell!" and staggered toward the hell creature with the dreadful stigmata.

He whirled at my shout; so did the others. Dorothy shrank into her chair. "Gil!" she shrieked. "They'll kill you, too."

Somehow that anguished cry sent the blood roaring through my bursting flesh, lent me the semblance of my old strength.

I leaped. The plague-master howled horribly. He shrank away from my coming. I must have seemed a frightful enough sight. But before I could reach him, the grey men were upon me, kicking, crashing at me with their fists, beating me back again. I struggled, I fought, I struck out with blows that were mere feather puffs. I was borne back remorselessly, bleeding, stunned, sent crashing to the ground.

The plague-master advanced. "So you wouldn't die in peace, eh?" he ground out. "We'll give you a taste of the pincers, too."

Steel flashed before my aching eyes. The girl's voice rose in strained horror. "I'll tell you; only leave him alone!"

"The bargain applies only to your father," he snarled. "Not to this damned butter-in."

Closer, closer, came the rending pincers, as the crawling, broken figure lifted itself over the threshold. I saw it raise the gun in a hand that shivered with ague. My gaze froze to it. "God, steady his hand!" I prayed. The pincers clamped on my ear, started to pull. A fiery agony beat in my skull. The figure that was Soloway hunched over me, drinking in with whistling breath the sight of my twitching torture.

The gun sagged to the floor, as if it were too heavy a burden, wabbled upward again. I felt cartilage giving. I shrieked.

Then all pain was forgotten. The gun hand had stiffened; the round bore snouted directly at the bending back of the figure with the scarlet stigmata. All my soul leaped into my eyes, willing him on, willing that finger to squeezing pressure.

The man Soloway must have seen the direction of my stare. He whirled around on cat feet. The gun was dead-centered on him now. He howled with fear and jerked forward. As he did, the gun spouted flame; the thunder of its explosion smashed through the room. The masked man gave a great convulsive leap, came down with a dreadful thud to the floor.

I must have fainted then. But the last thing I saw, or thought I saw, was the man from the dead rear a hideous head.

WHEN I woke it was to the sobbing murmur of my name. Dorothy, her face wet with tears, the vermilion signs of the plague startlingly distinct on her forehead, was chafing my gelid hands. I felt a queer rushing ecstasy. "I love you, Dorothy," I said brokenly. We were both soon to die; why then should I mask my feelings?

She flushed and nodded her head. She must have felt the way I did. For a moment we clung desperately to each other. Then I said: "What happened?"

She shivered. "I don't exactly know. But those dreadful Things ran as if they had seen a ghost. Father," her voice quivered, "is dead. Poor man, he is better off. As soon as I saw I couldn't do anything for him, I ran to you."

I lifted myself weakly. "We shall both be with him soon, Dorothy," I said.

Then I saw the huddled grey shroud with its row of bright red discs. I laughed harshly. "Soloway went first, but we won't meet him, I'm sure of that."

I tottered over to that sinister figure, twitched at the hood. It came off in my grasp. I staggered back with a great cry.

Dorothy ran toward me. "Gil, what's the matter?"

I could only point voicelessly. Staring up at us, dirty brown even in death, black beard torn awry, bushy eyebrows loose from their moorings, was the distorted, hate-snarling features of Dr. Hinsdale!

Dorothy gasped. "Hinsdale! That's not his name. I recognize him now. That's Sailendra Mir! The native doctor who used to do odd jobs for father!"

"Then who," I demanded in bewilderment, "is the other—the man who killed him?"

I had only minutes to live, yet I felt I could not die properly unless I knew. I forced myself over to the other creature, the man who still lay, face downward, the gun fallen from his nerveless fingers.

I turned him over, and received an even greater shock. It was the hideous, deformed monster who had smashed me down in the hall, who had tried to kill Andrew Burgess. My head was swimming with disease and utter confoundment. I could never unravel this.

But Dorothy moaned: "Oh! oh! This is Enoch Soloway. My God, what happened to his face, to his hand?"

The misshapen thing that had once been a man stirred. Like a corpse whispering back to life. He opened his eyes, stared with the shadow of approaching death at the girl. "Forgive me, Dorothy," he said slowly and painfully. "I am dying. It is better so. I deserve it. But I swear," he moaned, trying to raise himself, "I never intended—what happened. I—was jealous of your father; I wanted the—glory. I ran away with the antidote, and—everything. I wanted to publish, and claim I had found it. But Sailendra Mir must have seen me. He followed me, waited till I got to America."

He slumped down again upon the floor, but continued: "Then his men made me prisoner. Only last night, I heard him boast of what he was doing. I managed to slip my chains; I crawled into the room. Before they could stop me I had smashed the bottle of antidote and grabbed for your father's notes. It was all on a table before them when they were holding a conference."

The dying man took a deep breath, went on: "But he was too quick. He snatched the papers back; only a little piece stuck in my fingers. I chewed it, swallowed. It held the name of the last ingredient. He was crazy with rage; he tortured me with hideous tortures, but I wouldn't tell him. Then he flung me back in my cell. Outside I heard them talk. Somehow they had found out you had come to this town. They were going to compel you to tell them." He stopped; his head sagged.

"Go on," I urged breathlessly.

"I broke my chains again when they were gone. I must have been crazy with pain, for I staggered here, instead of going to the police. I found them prowling outside. Somehow I managed to get to the roof of the neighboring house and jumped. But Burgess saw me. There was no time for explanations. He had a gun. I hit him, took the gun, ran into the hall and into you. I got away and raced down to the cellar. Then I heard steps. Suddenly a flash blinded me, and before I could shoot, I went down. It was Mir. I recognized him in spite of his disguise, as I fell."

I nodded. The whole business was getting plainer. That scream we heard had been Mir's way of throwing us off the track. He had thought Soloway dead, had raced back to let his henchmen in the front door, and had donned his gruesome robe.

"But—but how," Dorothy asked, helplessly, "did he come as the doctor? How did he know whom I called? I took a name at random."

"Simple," I said. "The whole thing was planned. I, a nameless tramp, was the decoy. He had your wire tapped, answered your call, heard you mention the name. Then he cut the wires to make sure you couldn't call again."

SOLOWAY fell back. The blue of death was spreading over his features. Soon, I thought with sudden anguish, we would follow. I didn't want to die now, not after I knew that Dorothy loved me.

"Fool!" I shouted suddenly to myself. I clawed down to the stricken man. "What was the name of the missing ingredient?" I cried. My heard was thumping with a wild hope. Then it sank. The stricken man did not seem to hear. He lay motionless, dead.

I shook him, I cried, I raged. Life had beckoned and then vanished. It was incredible, horrible.

Then suddenly I recollected. The pseudo-doctor's bag! I raced for it; I stormed through its contents. There was the colorless flask, filled with a clear liquid. The antidote—minus the one precious ingredient. I held it up, almost let it drop in despair. Dorothy cried out sharply. "Gil, for God's sake, don't! The last thing mentioned on father's notes was potassium sulphate. I remember that. We have—have it here!"

She was running toward the glass shelf, toward a stoppered bottle. Then she stopped, turned tragic face to me. "But the exact amount," she whispered. "That—I don't know."

There was no time to experiment. Life was slipping fast. I could not stand the fire in my throat much longer. My hopeless eyes fell on the syringe. Strychnine!

The stuff that had pumped life momentarily into me.

It was the last chance. I grabbed it, wabbled unsteadily back to the dead-seeming man. No spark of life was on his monstrous countenance. Dully, without hope, I squirted the contents into his arm.

Nothing! It was all over. I rose wearily. God! If only—

Dorothy's sharp cry jerked me around. "Gil—his eyelids! I saw them flicker!"

I was on my knees again, shaking him frantically. His lips moved soundlessly; his eyes opened.

I cried: "How much potassium sulphate? How much?"

He stared upward with the look of one already dead; then his lips moved. I bent down, caught the faintest of whispers: "One per cent." A shudder rippled over his body. His eyes were open, but he did not see. This time he was irrecoverably dead.

But now it did not matter. It is not necessary to tell how we measured the precious dose with shaking hands, how carefully we added it to the liquid, how, with shuddering prayers, we drank.

It is enough that we are alive today, happy in our new home in this midwestern city from which our antidote cleared away the last vestiges of the plague that had spread horror for one long, nightmarish week. It is enough that once more I face the world, boldly, confidently, with a substantial sum of money in the bank, subscribed by a grateful people, whose lives we saved with the completed formula.

And we, that is, my wife and I, have made it a fixed, unalterable rule never to discuss the soul-grinding terrors of that night at Meadow Street. But often, at night, I cannot stop myself from reliving each dreadful moment. But then I hear my wife's calm breathing, and a blessed peace steals into my soul, and I sleep.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.