RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

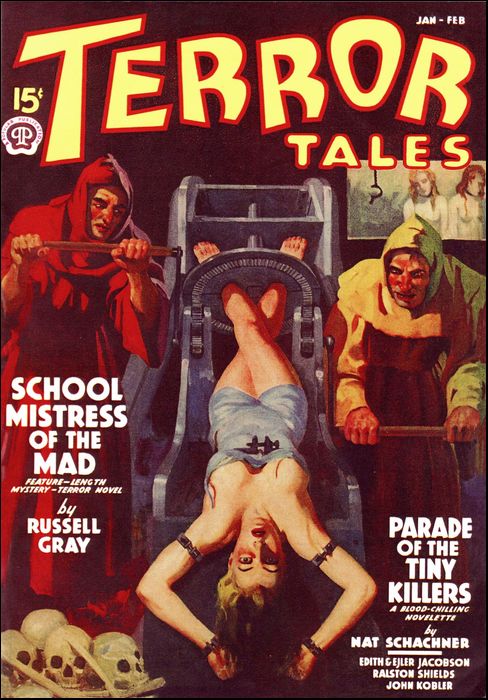

Terror Tales, Jan/Feb 1939, with "Parade of the Tiny Killers"

Was Valentine Frazer, the man the whole town laughed at the year before, responsible for the plague that turned Centerville into a shambles of blood and horror? Or was it true that the curse of death had been placed on that evil stone idol Frazer had stolen from the temple in darkest Africa—the idol that came to hideous life and crushed women to a pulp in its basalt arms?...

IT was the strangest parade Centerville had ever seen. Even before it started, there had been a few voices raised in protest; partly because of distrust of the man in whose honor it was being given, and partly because of an intangible uneasiness over rumors that had been set afloat, no one knew how.

Nevertheless, the parade was already under way.

I stood at the corner of Lincoln and Grand watching it, with a protective arm around Peggy Whitman to shield her from the pressing crowds. The sidewalks were black with people, and the perspiring police, few in number, were hard put to it to keep them from spilling over onto the line of march. Lincoln Avenue was bedecked with flags. The stores flaunted streamers and gay bunting. Clerks and stenographers leaned from the windows of adjacent office buildings in a gay holiday mood. It should have been a great homecoming for Valentine Frazer, to make up for the mockery and laughter that had greeted him on his former return from the unknown sectors of Africa.

But it wasn't.

I said to Peggy, as the first escort of mounted police pranced their horses slowly up Lincoln Avenue. "Listen to the crowd go wild, darling. They're making up for their former disbelief. Frazer's brought the goods back with him this time—the new race of pigmies he discovered, the strange idol they worship, and everything that he claimed he had seen."

She did not answer; but within the tight circle of my arm I felt her slim form grow rigid. I stared down at her lovely face. Her clear grey eyes, the piquant curve of her chin, her curly crop of sunny hair, always did things to my insides. I still could hardly believe that Peggy Whitman, ace feature writer of the Daily Argus, and most desirable of Centerville's younger set, had agreed to marry a struggling young lawyer like myself, Jerry Doane by name.

Just now, however, her eyes were troubled, and her cheeks, in spite of a hot July sun, were queerly pale. I felt my fist clenching unconsciously and my jaw growing rigid.

"Look, sweet," I said. "You really don't believe that Frazer threatened you because of those articles you wrote last year making fun of his claims?"

She kept her eyes carefully averted from me; watched the parade. The civic organizations were marching past. As yet, Valentine Frazer and his weird trophies had not started from the carefully guarded pier down at the Basin.

"Morgan Green way told me Frazer swore he'd make everyone suffer who had laughed at him."

"Morgan Greenway," I replied angrily, "is an ass, and a rival explorer to boot. He's jealous that Frazer found this idol-worshipping tribe in a territory that he himself was supposed to have covered thoroughly several years before. It was because of his denials that you wrote those articles linking Frazer with Dr. Cook and all the other fake explorers." I patted her hand comfortingly. "Anyhow, honey, I'll take care of Frazer if he starts anything with you."

Peggy smiled back at me wanly. "I know you would, Jerry," she said, with the sublime confidence of a girl in love, "if Frazer's threats were ordinary ones. But you've heard the rumors about those awful pigmies, and that idol he carted back with him."

"Publicity stuff!" I told her. "A swell build-up by Jimmy Rean for his circus. He's paying Frazer heavy to exhibit the tribe and their idol, you know."

YET, in spite of my blustering talk, I couldn't help feeling uneasy. I had spoken only that morning to Dwight Ewing, curator of the Centerville Museum, about those horrifying rumors that were floating about town. He had not laughed. In fact, he had turned pale. A haunted expression came into his face. "I've heard about them, Mr. Doane," he said seriously, "and they're no laughing matter. There had been talk for many years among anthropologists and explorers about a strange tribe of pigmies who lurked in the fastnesses of the Devil-Devil Mountains in the heart of the Tanganyika Territory. Queer tales of their hideous practices, of the strange idol they worship that walks like a man and kills like a devil. Even the fierce Zulus never dared penetrate their territory. And those few white men who went in never came out, or were found, hideously crippled, hopelessly insane, babbling of little captured children who were changed before their eyes into age-old pigmies, wolfing human flesh in honor of their terrible idol." Ewing had stopped short with a conscience-stricken air. "Don't let this go any further, Mr. Doane," he said earnestly. "You know how easily a panic can start.

I hadn't really believed these stories myself. That was why when Frazer came to me last year with his wild tale of what he had seen, and asked that the Museum back an expedition for him into the land of the pigmies, I refused." The curator smiled a bit bitterly. "Of course there were other reasons for refusing. Our funds are pretty scanty; until today, no one in Centerville would be aroused to an anthropological research. My own salary is barely above the starvation level. In any event, Frazer got pretty sore—he took Greenway's taunts and Miss Whitman's satiric articles in bad part. And he called me names. Where he got his funds from, or how he managed to persuade or force these pigmies to return with him to the United States, I do not know. There was supposed to be a curse upon their idol, that would blast whole nations if it was ever removed from its temple."

The crowd around me surged forward eagerly. I barely managed to hold Peggy from being swept into the street. Necks craned down the wide thoroughfare.

"Here they come!" someone in the crowd shouted.

The doors of the covered pier had been thrown open. A number of long, sleek Packards, with open tonneaus, moved slowly through. The mob that surged around the Basin let out a roar of welcome.

Then the roar died.

"What happened?" gasped Peggy. She tried to stand on tiptoe, to look over the heads of those around us. I am rather tall, so I could see pretty easily.

I gripped the girl's arm. "I think," I said rapidly, "we had better get out of this. It's too hot and crowded to watch a silly parade."

Peggy twisted within my hand. Her grey eyes looked steadily up at mine. "Jerry Doane," she said, "I am not a fool. You forget I'm a pretty good reporter. What is happening down there that suddenly caused the crowd to stop cheering?"

"I don't know," I admitted. "It's too far to see exactly. But the people on the sidewalks seem to be crowding back, to be scattering into the side streets. Even the police are going."

IT was true—and unbelievable. I had never seen a parade crowd act like this before. There were four automobiles in the feature cavalcade. One that housed Valentine Frazer, the triumphant explorer, half submerged in flowers and floral wreaths. The second with a single motionless figure propped up on the back seat; its features a mere frozen blur from where I stood. Then two cars, side by side, crowded with dark little creatures, mere bobbing dolls in the distance.

As the four autos moved up Lincoln Avenue, something strange was happening. A wave of cheers rolled out before them from the crowded spectators. But the greetings died abruptly as the procession came abreast. Even this far away I could detect the sudden shift in psychology, could almost hear the swift, short intakes of breath of the onlookers. The cheers froze on their lips; those who had pressed closer to the street line for a better view were the first to shrink back.

They had passed Anderson Park by now; were only two blocks away from where we stood. The figures in the autos were quite visible and distinct in every lineament. A red-faced man next me started to cheer: "Hurray for Frazer!" Some others in the rear took up the cry.

Then it died.

The red-faced man jerked his head forward. The color fled from his jowls. "My God!" he said hoarsely. A young woman in the very forefront, with a child clutched tight in her arms, began to push backward. Her lips twitched with a strange fear. "Let me out!" she implored. "Let me out!"

Valentine Frazer was abreast of us now. He lolled in the back seat of his car, half submerged by floral wreaths. He was a tall, bony man with piercing black eyes. His skin, drawn tight over high cheek bones, was burnt by tropic suns to a dirty brown. His thin, straight lips were a bloodless gash.

But there was no answering welcome in his gaze to the first scattered cheers. His sunken eyes surveyed the swaying mob with curious little prickling fires; his lips seemed to press tighter with the memory of former wrongs. Frazer was not the man to forget the derision with which he had been greeted once before.

Slowly his head turned toward where we stood. His eyes flicked over me with a stiffening frown, fixed upon the girl who stood at my side. The banked fires flared. The black pupils seemed to distend.

"Oh!" Peggy exclaimed faintly. "I—I think, Jerry, we'd better go."

I felt the corded muscles swell under my jaw. "Hero or no hero," I growled, "I'll knock his head off if he looks at you like that."

But already his car had moved slowly ahead, and the next came into line. I stared, and forgot Valentine Frazer and his sullen hate; forgot everything but the strange sense of overwhelming horror that rooted my limbs.

Up ahead, the bands were still playing brisk march tunes, but here they seemed curiously far away. We had descended abruptly into the pit, into a savage world where Evil ruled and unbridled lust and obscene passions held full sway.

A burly policeman stopped his interminable shoving at the spilling crowd. His eyes popped. "Mother of God!" he ejaculated.

The idol was propped up between cushions. In size it was about that of a man, and it sat with long black arms motionless on black knees. It was carved from black basalt, and its hard, polished surface seemed to quench the burning rays of the July sun. The head was a gargoyle of ugliness. Red ochre and white clay daubed its frozen face into a fantastic grimace. A leer of the abysmal brute hovered around its motionless lips.

It was hideous enough in all conscience, but mere ugliness would not have been sufficient to cast that blighting pall upon those who stared at it aghast. Its head was turned askew, so that to my heated imagination its slitted eyes seemed to bore directly into me. I felt a strange impact; my will seemed to flee, my limbs turn to flowing water.

THEN it was over. Life rebounded in my veins. That terrible look had been withdrawn. Was it madness on my part, though, or the dizzying heat of standing in the sun, that made those sunken basalt eyes seem to move in a slow arc and come to rest upon the loveliness of the girl I loved?

She was beautiful enough even to attract the gaze of an idol of stone. The sheer thinness of her dress molded her breasts into delectable roundness, and the whiteness of her uncovered throat made ardent the casual glance.

But I could have sworn the basalt eyes had moved; I could have sworn that a strange, fierce lust had colored those black, recessive depths. Peggy cowered against me. I could feel the softness of her body shaking with terror.

"It—it's staring at me as if it were alive!" she whispered brokenly. "Terry, I'm afraid!"

I firmed my grip on her, shook off the strange dread that had encompassed my own limbs. "Nonsense!" I said loudly. "It's an illusion—a trick of the sun and shadows. How can a thing of stone be alive?"

The procession halted suddenly. Up ahead there was a traffic intersection. The car that held the idol had come to a stop a little beyond us. The two remaining cars had stopped as well. Each swarmed with half a dozen tiny folk.

Once, at a World's Fair, there had been on exhibition a whole village of the pigmy people of Africa. I had examined them with interest; but that was all. They were human beings; small in size, it is true, but with human lineaments and friendly enough.

But these pigmies whom Frazer had brought to Centerville were different. No human beings could have sent that vivid horror pulsating through my body. I flatter myself that I am a sane, common-sense young man, with steady enough nerves. A lawyer can't afford to be subject to delusions.

Yet somehow, these tiny creatures, not more than three or four feet in height, inspired me with unutterable loathing. It was not merely the pitchy darkness of their skins, nor the twisted savagery of their faces. It was something else. Their eyes, for example. They glared at us with incredible hate; but they were not black, as are those of all negro tribes. Instead, there were blue, and slate grey, and brown flecked with yellow; as if they were the incongruous eyes of white men, startlingly set in alien masks.

White men, did I say? Boys rather, young lads in their teens. It was that last touch which added sheer horror. Aged and twisted with centuries though they seemed, underneath I sensed a queer childish agony—a desperation of young white souls helpless against the obscene molds into which they had been cast.

How long we stood that way I do not know. How long the procession paused I have no present knowledge. Paralysis had gripped the crowd, held it motionless in the contemplation of those baleful figures.

Someone brushed past me; squirmed out into the roadway like an eel. Unknowing, my eyes followed him. It was a little boy, not over ten, his sharp young face glowing with the thrill of a parade, of sights never before witnessed.

I recognized the lad. He was Billy Saunders, the only child of poor old Widow Saunders. Everyone in town knew her, and the boy who was all that remained to her of hope and joy in the world.

"Billy," I called sharply. "Come back!"

But the little fellow did not hear me. He wanted to see the strange idol and the pigmy folk. Poor lad! His mother would never be able to raise the dollar admission to view them at close range the following evening in Rean's Circus.

He raced out into the road, right up to the auto in which the basalt idol sat stiffly. He clambered onto the running board, heedless of the hoarse shout of Coogan, the cop; of my own sudden cry.

"The little imp!" I grunted; dropped Peggy's arm, and started out after him.

My foot had not cleared the curb when the boy screamed. It was an ear-piercing scream, such as a young calf makes when the butcher's knife is laid to its throat. His twitching young form jerked back off the running board, fell to the hard pavement in a huddled sprawl.

But even as I raced for him, and Peggy's cry rose above the startled yells of the mob, two things happened.

The traffic light ahead had changed to green, and the procession started forward again.

And little Billy Saunders had sprung to his feet, was running wildly down the block as fast as little feet could carry him, his childish treble echoing a frightened refrain. "It's alive! It's alive!"

AT six that evening a group of us sat tensely in Mayor Lovett's office. George Lovett was uncomfortable. His eyes never lifted from the burnt-out cigarette in his flabby fingers.

"Mr. Mayor," snapped Morgan Greenway, the explorer, glaring across the table at his rival with vindictive eyes, "you've got to stop Frazer's show. And what's more, you'll give orders to have those fake pigmies of his rounded up and placed where they'll do no more harm."

An animal-like snarl came from between Frazer's tight-held lips. He started up.

But burly Jimmy Rean, who sat next to him, thrust him back in his chair with a flick of his huge hand. His broad red face did not change its expression. A thick black cigar bobbed between his lips as he spoke. "Mr. Greenway is jealous because he didn't find the pigmy tribe," he said. "I don't blame him for that. But when he tries to ruin my circus, that's another matter. I've got a contract with Mr. Frazer to show his natives and that idol of theirs tomorrow night. The Big Tent is a sellout. If the Mayor of Centerville or any blue-nosed busybody like Greenway tries to stop us, or passes cracks again about fakes, there'll be trouble pronto."

George Lovett looked at me miserably. I acted as counsel for the town on occasion.

I cleared my throat; tried not to look at Peggy. She was sitting at the farther end of the table, her notebook open before her. She was covering the conference for the Daily Argus. But she had been curiously listless throughout the proceedings. The open page was still bare of pothooks. Ever since the parade there had been a strange dread clouding her eyes.

"I'm afraid Mr. Rean is right," I said. "There is no real evidence connecting Frazer's pigmies with the death of Billy Saunders, the disappearance of the other two little boys, or the horrible mutilation of that girl who was found in Jones' Alley. If you stopped the circus, you'd be subject to heavy damages, Mr. Mayor."

Greenway flung violently to his feet. "All right," he shouted. "Let Frazer and his gang continue their reign of terror. No evidence, hey? Didn't Billy Saunders yell things about the idol as he ran screaming down the street? Didn't they find him dead, without a mark on him, two hours later in the vacant lot near the Basin?"

His pale eyes gleamed: his sallow skin burned with a hectic flush. "Mark my words. Before this night's over you'll have such a shambles in Centerville that you'll go down on your knees and pray God to forgive you for not having taken my advice. That idol has a curse on it. Frazer stole it from the Devil-Devil Mountains. It will bring a plague of deaths wherever it is. But he never found its pigmy worshippers."

He spun on the explorer, shook his fist at him. "Those pigmies of yours are boys:—white boys whom you kidnapped, and changed into evil changelings with certain witch-doctors' drugs that you found in Africa. You're working a racket. Rean backed your expedition in return for an agreement to exploit your finds. You couldn't get the pigmies, so you're manufacturing them. But they've broken loose—the drugs have twisted those poor little children into fiends. They're killing on their own now. And you need more victims to take the place of those who escaped. That's why two more boys disappeared today."

He spun on his heel, darted out of the office before anyone could speak. Behind him there was a moment's silence. Peggy swayed forward; almost slumped over her notebook. Her face was the color of ashes.

A RED mist swam before my eyes. My heart missed a beat; then pounded furiously. I remembered Billy Saunders' frightful scream as he almost touched the idol. I remembered the strange sensation I had when I first saw those pigmies. There had been two deaths in the last five hours, and two boys of ten missing. Ten! The same age as Billy! The same heights as Frazer's little folk!

Dwight Ewing, Curator of the Museum, broke the hushed spell that had followed Greenway's outburst. He was a medium-built man, with the contemplative eyes of a scholar, pince-nez, and a little grey goatee. He was a well-known archaeologist, and had been himself to Africa on expeditions for the Museum.

He took off his glasses, surveyed Frazer with precise deliberation. "Those are—uh—rather serious charges, Mr. Frazer," he said. "What have you to say about them?"

Valentine Frazer came slowly to his feet. I had noticed earlier a frightened look in his eyes. But now it was veiled under a hell of fury. "Damn you all," he snarled. "You and Greenway and the rest of them are trying to blast my reputation. It wasn't enough that you made a mockery of me the first time I came back from Tanganyika; you're trying to ruin me again. I'll—"

Jimmy Rean lifted from his chair. For a big man he moved fast. His hand shot out, caught the raging explorer in a grip of steel. "Shut up, you fool!" he said in even tones. He faced the rest of us. "We'll do our talking in court." he announced. "Greenway will pay through the nose for what he said; so will anyone else who spreads his nonsense." He glanced meaningly at Ewing, stared past me with calm insolence at Peggy.

I jumped up. "You leave Miss Whitman out of this, do you hear?" I said heatedly.

Rean looked at me with assumed surprise. "I haven't even mentioned her name," he countered. "But naturally, if she would be thinking of writing any more little articles, like those of last year—"

He left an implied threat hanging in the air. He opened the door of the Mayor's office with one hand, propelled Frazer before him with the other.

A cold wind gushed through me. I had an eerie feeling that there would be no courtroom trials; that some of us who had been in the Mayor's office were doomed to die before another night had passed. But even this strange psychic warning of mine did not begin to encompass the full horrible truth....

I took Peggy in my car to the Argus Building. She insisted on that against all my pleas. As we parked in front of the clanking newspaper plant, I tried again. I held her tight in my arms, smelling the subtle perfume of her warm body, feeling the delicious softness of her bosom pressed against my heart.

"Darling," I begged. "Please let me take you home; let me drive you over to Winchester, out of this altogether. If you write up what you heard in Lovett's office, your life will be in terrible danger." I shuddered. "Remember what that Talley girl looked like when they found her this afternoon."

She clung to me with a sort of desperation, but her voice was steady. "I am a reporter, Jerry. The Argus depends on me for its spot news. It is my duty to write the story."

"But—" I started to argue.

She disengaged herself gently from my arms. "Suppose," she said, "you were defending a client. Suppose you were threatened with death if you went on with the case. What would you do?"

I opened the door of the car. My hand shook with ague, "You're right, sweet, as always," I said dully. "But tomorrow morning I'm calling for you early."

I LIVE on the outskirts of Centerville, not far from the Basin. An arm of the sea comes up almost to my door, and at night I can hear the splash of the waves and smell the good salt air. But tonight I lay in a sleep of drugged exhaustion, hearing nothing, feeling nothing. Mrs. Hanson, my housekeeper, had taken the night off to visit some relatives. I was alone.

A faint, insistent burr pervaded my consciousness. I rolled in bed, tried to shake it off. But it grew louder, louder, until I awoke with a start, hands clenched, trembling in every limb.

Someone had his finger on the door bell and was holding it there. Voices shouted my name loudly, urgently; peremptory knuckles slammed against the door. They made enough noise to wake the dead. I bounded out of bed, all sleep fled from my eyes. Somehow, sickeningly, I knew what was the matter. Slipping on a bathrobe, slippers, I ran to the door, turned the lock. Men tumbled in, their faces white in the moonlight, guns glinting in their hands.

"What the hell—" I started.

"Get into your clothes quick, Doane," gasped Jimmy Rean, the circus man. His big red fist cradled a sawed-off shotgun; his florid complexion was pasty white. "We're forming a posse."

I felt little things crawl under my skin. I gripped the door jamb for support. "Is it Peggy?" I managed.

Other faces tumbled behind him, each in the grip of an awful fear. Men I knew—Mayor Lovett, Greenway, Dwight Ewing, Hal Martin the garage man, Sam Smith who ran the haberdashery, others. But not Valentine Frazer!

Ewing pushed forward. His little grey goatee was askew. His eyes blinked rapidly behind his glasses, as though trying to hold back unmanly tears. The big Colt in his slender fingers shook.

"Who knows, man!" he exclaimed. "It's not only one girl; it's everybody."

Hal Martin's face was a thing of stone. "They got my Paula—"

The flat unemotionalism of his voice was more terrible than any grief.

"Damn 'em!" screamed Sam suddenly. "Little Jacky is gone! If those devils—" Then he began to sob; great dry sobs that tore at the throat.

I was flinging clothes upon myself. I barely heard them. It was selfish, I admit, but a great fear was churning my insides. Peggy, the girl I loved more than life, than honor, than the whole darn universe together, had gone home alone last night; was alone in the old Whitman house across the flats. Her parents had gone to Winchester for the week-end, and Mamie, their servant, never stayed in Saturday nights.

"But who—what?" I gasped as I laced my shoes, ran to my dresser, and pulled out the police automatic I kept for emergencies.

Rean groaned. "I take everything back that I said. It's Frazer's pigmies. I thought I had them locked in safe for the night in our pay car. But my watchman, making his rounds at midnight, found the door smashed open, and all those little devils gone."

Greenway's sallow countenance flared with a curious triumph. "And tell them the rest, Rean; that your great Valentine Frazer has gone with them," he rasped.

"I wouldn't be too ready to blame Frazer," Ewing broke in mildly. "Perhaps they killed him first. You never can tell what he did to them to force them to leave their native land and come here to be shown off like freaks."

"Why don't you tell him everything?" said Hal Martin dully. Only his eyes showed the terrible madness that lay underneath his frozen mask. "It wasn't no pigmies got my Paula. I saw him bending over her body." He swallowed air in a huge gulp. "It was that—that idol—a-walking like a man. I saw him clear as day."

"NOW look here," Ewing said. "Your excitement must have blurred your vision. After all, we're intelligent people. We're not superstitious savages in the heart of Africa. An idol, a thing of stone, no matter how cunningly carved to resemble a living creature, cannot walk; cannot rip open a human body the way your Paula was."

Greenway whirled on the circus man. "Did you check up on that idol before you raised the alarm, Rean?" Again, in all my patient horror, I noted that strained eagerness in his voice.

The big man bent his head. He seemed crushed. "Yes/' he admitted with a certain husky effort. "We had the stone image in our strong room. We found the door smashed out—and it was made of steel—as though a battering ram had struck it." He raised his head with a frightened look. "There was something else I didn't tell any of you before. The door to the pay car was smashed in—not out, the same way."

A half-hysterical laugh tore from my lips, though God knows I did not feel like laughing. They stared at me in amazement. "This is too much," I cried. "Ewing is right. We're not savages with darkened minds to believe such truck. Those obscene little devils are responsible for this; and Frazer is—"

I stopped short. We were out on the porch now. I flung the door shut behind me, and ran down the steps.

A girl had screamed, once; a sharp cry of unutterable fear. Even as we stood, frozen in our tracks, she screamed again. This time there was madness in it; agony beyond all endurance.

As though our heads were animated by a single jerking cord, they swung in the direction of that awful cry.

The marsh grass grew thick along the edge of the Flats. It was tall, coarse grass, high enough to conceal a man in its rank vegetation. But directly in front of the waving fronds, barely a hundred yards from where we stood, I saw something that chilled the marrow in my bones.

A ghastly black image stood like a Colossus in the sodden ground, its stony feet widespread, its red and white painted face of basalt glimmering in the moonlight. Lust seemed to dart from those carven eyes, to pulse like a flame through the lava-hardness of its countenance.

Its black, jointed arms were wide, stiff. Within their crushing grasp, struggling furiously, beating with small, bruised fists against the stony chest, was a girl! Capering around the idol and its prey, clapping its hands in obscene glee, venting unintelligible cries, danced a little creature out of hell. A pigmy, not over three and a half feet tall, its weazened, sooty face screwed up into an infernal mask, its lank, black hair falling in coarse strings around its childish head.

"Peggy!" I cried out in a great voice.

The girl's head turned feebly at my cry. The white moonlight etched the awful terror in her eyes, the bloody streak across her cheek.

"Jerry!" she screamed. "Help! I'm being crushed! It's stone! It's—"

But already I had jackknifed from the porch, was slamming forward as fast as terrorized limbs could carry me. I forgot the gun in my hand; couldn't have used it even if I remembered it. How could I avoid hitting Peggy, whose cries were growing fainter, whose struggles were becoming feebler?

Behind me, however, I heard two shots in rapid succession. I swear I heard the sharp spang of a bullet upon the stony surface of the idol's thigh. The graven image did not even stagger. He swung around, faced me as I ran. To my crazed senses it seemed that a hideous grin distorted his craven lips, his ochre-splashed head of basalt.

The pigmy, however, as the second bullet cracked, screeched horribly. Pie stopped his capering dance, jerked howling into the tall grass that swallowed up his puny form as though it were a crawling insect.

Not fifty yards separated me from the idol and Peggy. Her cries had ceased; she hung limp and unmoving within those terrible arms. I put on extra speed. "I'm coming, Peggy!" I yelled.

The idol surveyed me deliberately; its stony face terrible in its frozen immobility. Then, without hurry, in ponderous fashion, it turned, stalked into the marsh grass, still holding the girl against its rigid bosom.

I pulled up my gun as I ran; sent a stream of steel-tipped pellets flaming into the night. I heard the dull, plunking sounds as they hit. It was such a sound as comes when bullets flatten themselves against hard rock.

But the idol moved on without a stagger, straight into the tangle of weeds. Just as I slammed to the place where he had stood a few moments before, he had vanished. Not even the waving of the high tops of the grass betrayed where he had gone.

FEET pounded behind me. The posse ran up to where I was, came to a halt on the very edge of the marsh. "God!" moaned Rean, his thick lips twitching. "I was sure you hit him several times."

"I did," I answered. "The slugs took no effect."

Sam Smith's eyes burned with a savage light. "I got that little devil, though," he chuckled wildly. "He can't travel far with a thirty-eight in his guts. I'll blast everyone of 'em down until I find my—my boy."

I started into the grass.

"Hey! Where're you going, Doane?" Greenway cried in alarm.

"After that thing of stone," I said, "and Peggy. Follow me, men."

Greenway shrank back. "Not me," he muttered. "Not for a million bucks. It's come to life, just as the curse said it would. It'll make mincemeat of us all."

"Me, neither!" shrilled Mayor Lovett, his round little eyes protruding.

"Then I'm going alone," I called back.

Peggy was in the power of a monstrous thing, and those cowards would let her die the way the other girls had died. I had seen the body of Jane Talley. She had been crushed out of all recognition to a human being. Every bone in her slender form had been broken almost to powder, as though it had been squeezed in a terrible vise. Only her head had remained intact.

I slogged on, grimly, desperately, through oozing ground and black muck, seeking that which I dreaded to find.

Through the muffling grass I heard Rean's bull roar. "We're cowards, lads, and we know it. Only Jerry Doane has the guts to go in after him. The least we can do is to scatter along the edge of the swamp, in case the idol ducks out. I'll take the left hand side; Mr. Mayor, you take the right. Split up into two parties."

Then all voices died; and I was alone in a sea of vegetation that towered high above my head. Despair gripped my vitals; despair, and a dreadful fear. My own life no longer mattered, but I must find Peggy before I died.

It was dark in there. The thin rays of the moon barely filtered through the tangle. My feet sucked in deeper and deeper; the stench of rotting vegetation and crushed salt filled my nostrils. But still I went doggedly ahead; seeking, seeking, hearing no sounds but the distant lap of waves; all sense of direction lost.

Then I stumbled over something yielding. My heart raced; died to a chilled whisper. Wildly I parted the heavy grass, stared down at the form that lay face up in the black ooze.

My first sensation was one of overwhelming relief. It was not Peggy. My second was one of savage gladness. The body was tiny, and the black muck half-covered its face. Then I stooped quickly, a new and more gruesome fear displacing all else. With the sleeve of my coat I wiped desperately at those little features.

I cried out then and answering yells sounded close at hand. Without knowing it, I had stumbled in a circle through the tall marsh grass; had come to a point close to where I had entered.

"Good Heavens!" shouted Ewing, as he thrashed to my side. Then he stared down at my find. "The pigmy that Sam Smith shot," he said, startled.

I shook my head as the other members of the posse pushed their way through. "No," I said. "It is not the pigmy."

Just then Sam stumbled heavily in. "I knew I killed the damned little beast," he crowed. "He'll never catch any other little boys to—"

I tried to get between him and the body; but he was too quick for me. A sudden hush fell upon the crowding men. It was a terrible thing.

There, lying in the swamp ooze, his face barely cleansed by my sleeve, was little Jacky Smith, Sam's only child. A round bullet hole showed dark in his chest, the edges discolored with muck and black water.

The flame of triumph ebbed slowly from Sam's face. A bewildered expression took its place.

Then, with a frightful cry, he fell on his knees in the mud, flung his arms passionately around the poor little body. "Jacky! Jacky! It can't be you! It can't—"

He jerked to his feet, still cradling his son. He glared around at us with mounting madness in his eyes. "You saw me, fellows," he mumbled pathetically. "You saw me shoot the pigmy. I didn't shoot Jacky. God, I couldn't have!"

We averted our eyes; a strange dread throbbed in our veins. We couldn't look at the father.

He searched our blanched faces, seeking some justification; something to take the edge off the verdict. Then, suddenly, he screamed. I'll never forget that scream as long as I live.

"Jacky!" he screeched. "It was you all the time. The idol changed you! Yet I tried, and tried..." Something burst in his voice. "I killed you! I killed my own son!"

I sprang for him, but it was too late. His eyes held the glare of utter madness in them. With a great final shriek he plunged away, deep into the swamp, toward the flats where the tide was creeping in, swirling around sucking mud and treacherous bars; the body of his dead son hugged close to his chest.

I started to follow; but Ewing caught my arm. "Let him go," he said softly. "It's better that way. He'd never recover from this thing as long as he lived."

WE plodded back to firm ground, to the open meadow. Mud caked our hands and clothes; water squished from our shoes at every step.

"The tale was true then," Greenway whispered. "I never really believed it. A stone idol that walks like a man; white boys that are changed by some dreadful process into obscene pigmies, to regain their proper form only in death."

"We've got to find Frazer," snarled Dwight Ewing. "He's behind all this. I defended him before, but after what we saw—" It was hard to recognize the soft-spoken scholar and famous archaeologist in this wild man with bloodshot eyes, glasses gone, his clothes a sodden wreck from the marsh gumbo into which he had evidently fallen.

A murmur arose among the others; it swelled to a roar. "That's right," they yelled, brandishing their guns. "Get Frazer! Lynch him! He brought them here. Come on, fellows!"

Led by Rean and Greenway, they ran toward the road, toward their cars that were parked on the side. Like madmen they tumbled in; starters turned over, exhausts blasted, and they roared off toward town, toward the circus grounds where Frazer had been installed for the night by his backer, Jimmy Rean.

I did not follow. Peggy had been taken from me. Somewhere, within the swamp, or on the tidal flats, she lay dead, her dear body crushed beyond recognition. Perhaps she would never be found.

I had to avenge her; I had to protect those other girls and the little boys from the fate that had overtaken Peggy and Jacky and a dozen other victims.

The posse, with true mob psychology, had fled in relief from the incredible; was seeking some human fiend upon which to glut its vengeance. Instinctively, however, I knew that the answers lay somewhere in the swamp, or perhaps...

I had seen what seemed to be the supernatural. I had seen an idol of stone walk like a man, seize its prey with stiff, hard gestures. I had seen a pigmy from the depths of Africa turn incredibly into a little boy whom I had known all his life in Centerville. I had seen girls crushed to death as no mortal arms could have done; yet still I disbelieved all the testimony of my senses, sought for some other explanation for these horrors.

Frazer? He was obvious, of course. He had brought the strange pigmies and their terrible idol back with him from Africa. He hated Centerville, in spite of his present accolade; and he had threatened Peggy for the articles she had written in derision the year before.

Greenway? He was a fanatic, capable of anything. His professional pride had been hurt by Frazer's discoveries in territory he had claimed as his own. Certainly he detested Frazer; would do anything to discredit him.

Jimmy Rean? Seemingly he was doomed to lose a lot by what was taking place. But who knew? Suppose he was double-crossing Frazer, making him the goat to force him out of a share in the profits. Later on, when things blew over, the tribe and the idol would be worth a fortune to a canny showman. No tent, no matter how big, could begin to accommodate the hordes of morbid curiosity-seekers.

Even Dwight Ewing, Curator of the Museum, and Mayor Lovett, did not avoid my suspicion. The former had been in Africa himself, knew the legends of the Devil-Devil Mountains; the latter had been under a cloud for some time. There was talk of an investigation into certain city contracts. If the peoples minds could be distracted....

I whirled suddenly in my tracks. Some sixth sense had sent its prickling warning down my spine. But I was too late.

I had not seen the little men writhe snake-like through the coarse grass of the swamp. I had not seen them lift with a sudden rush until they were upon me. Knives glittered in their weazened hands, a strange madness blazed in their eyes.

I shot once, but the bullet went wild. A knife point jabbed my elbow, diverted my aim. Then I went down under a horde of flailing bodies, like a giant Gulliver among Lilliputians. I tried to fight back, but there was amazing strength in them, and their knives cut and slashed until I felt no more.

WATER filled my lungs; it clogged my mouth and nostrils with saline bitterness. Instinctively I kicked out with hands and feet. The darkness in my brain lightened; I felt myself rush upward; then I was gasping and choking and spewing out great mouthfuls of ocean.

I thanked God that I was a good swimmer, or I would have died then and there.

I was weak from a dozen knife cuts; much blood had gushed from my battered body before I had been thrown into the bay for dead. The tide had turned, was going out to sea again like a millrace.

Yet I managed to keep afloat until the cold green water revived me and I knew what I was doing. I shook the spray out of my eyes, tried to get my bearings. The moon had set, and only the stars gave me feeble light. I took hasty stock.

The tide was running strong, and the nearer shore was at least a mile away. I'd never be able, in my weakened condition, to buck the terrible current. That meant I'd be swept out to sea. Which meant—

In the darkness I heard the hurried sound of oarlocks. Hope flared in me again. I opened my mouth to shout for help; gulped back the unuttered words, and submerged shallowly to keep from view.

The rowboat had silhouetted a moment against the feeble starshine; and in it, rowing like mad, their faces distorted by the shadows, were Jimmy Rean and Valentine Frazer!

Even as I dived, I noted also the rope that trailed in the water from the stern of the boat. It was my last chance for life—though my own life meant but little to me with Peggy dead—and to penetrate the secret of the horror that had invaded Centerville.

For now suspicion had flared to certainty in my brain. Jimmy Rean had pretended to go with the posse to seek out Frazer as the instigator of the reign of terror; yet here he was, in the company of Frazer, hurrying to some unknown destination together.

With a last supreme effort I caught at the dangling end; held tight though it seemed more than I could do. I dared not lift my head above the waves, except to gulp in occasional hasty drafts of air.

They rowed ahead in great haste, bucking the tide, hitting out on an angle toward the farther shore. I tried to listen to their low speech, but the whip of the waves, the creaking of the oarlocks, and the need I had to keep submerged, made the words an indistinguishable drone.

After ten minutes of being dragged along like a captured fish, something dark and somber loomed ahead. The boat swerved, made for it.

For the first time I realized' where the precious pair were heading. Something that was not the chill of the water froze the blood in my veins. Almost I cut loose to take my chances with wind and tide; then courage came to me; and I gripped all the more desperately.

Fort Armstrong had long been abandoned by the government—and forgotten by us in the town. It stood on a low island at the outlet of the bay, inhabited for years only by gulls and crying curlews that sounded like lost souls in torment. The bastions were half-disintegrated by the ceaseless waves, and the guns that once had frowned from the embrasures lay on their sides, rusted and useless.

During the Civil War the fort had been used to house prisoners of war, and every fisherman, every longshoreman in Centerville, devoutly believed that the bloody ghosts of the men who had died in its dungeons still walked the battlements. No reward could induce one of them to land upon the accursed island. The less superstitious in town also gave the sinister fort a wide berth; it was rumored that smugglers made the ruins a base for their forays.

Just as the boat swung high on a wave, I let go. Swimming desperately, I managed to fling myself on shore, exhausted, spent, in time to see the two men beach their boat, lift it out of reach of the surf, and disappear stealthily into the night.

I lay on the sand a few moments, panting, catching my wind, and giving them a chance to get out of earshot. Then I rose silently, and followed them. I had no doubt but that here, in the fetid dungeons of the old fort, I would find the secret lair of the pigmies and their idol.

The scum-covered wall of the battlements came to within a few feet of the water. Warily I followed its looming granite to the left—where Rean and Frazer had vanished into the darkness. About fifty feet on, an embrasure yawned. I came to it. As I did, two figures, their height exaggerated in the blanketing dark, rose suddenly above me. I flung up my hand in time to break the blow that was aimed at my skull. But its crushing force battered me to earth, left me dazed and unable to move. A hoarse chuckle filtered through my whirling senses. I had walked straight into a trap. They had seen me follow; had waited here for me to come up. Then they had jumped me.

FOUL-SMELLING water trickled down my back. A noise of drums and barbarous singing enveloped me. My head seemed slashed with many knives. Slowly awareness came to me. Then full consciousness flooded every fiber of my aching being as my eyes opened on the incredible scene.

I was sagging, half upright, my swollen limbs encircled with rusty leg irons and green-verdigrised handcuffs of an older day. They held me against the damp slime of a dungeon wall, deep within the bowels of the earth. I was a chained and helpless prisoner where generations before, men had died without hope, without mercy.

But I had no time for thought of myself. All my horrified senses were concentrated on what was taking place before me. Light flared in the rock-hewn chamber; light from a fire of bleached jetsam that sputtered and cast eerie shadows on the walls.

Around the fire, leaping and gesticulating in wild dance, were the pigmies from the Devil-Devil Mountains. They looked more like demons than like human beings. Their savage, distorted countenances were daubed with plastered mud. Their tiny bodies, naked except for a filthy breech-cloth, were startlingly childish in every immature line. But more than everything else, their eyes held me—blue and brown and greyish yellow—the eyes of white men, or boys!

My eyes lifted past them; my heart shuddered to a halt. Against the farther wall, enshrined in strange shadows, was the idol. It sat stiff-legged on a fallen rock, its black basaltic arms outstretched in sinister anticipation. Its stony eyes leered at me with a strange contemplation; its polished body shone in the leaping glare of the fire.

Something died in me then. Somehow I had held a tiny doubt about that idol. I had refused to permit the truth to penetrate my brain, for fear that I might go mad. But now. at close range, there could be no mistake. This obscene creature whom the pigmies worshipped, whose stony arms crushed tender flesh to death within their grinding power, was no mere clever mask, donned by a human monster. It was in truth a creature of stone, a hideous image carved out of primordial rock, a basilisk infused with an obscene life of its own.

On either side of the awful thing, frightened, trembling in every pitiful limb, were two little boys. White boys; youngsters whom I knew. Bobby Green and Lonny Thomas. Boys who had vanished from their beds that night, and left no trace of their going to their frantic parents.

Their little cheeks were stained with tears, their childish voices were lifted in shrill cries for mercy. But each was held in the grip of a pigmy, and their cries were drowned by the drums of the dancing devils.

Even as I tried to part my own puffed lips, to cry out, their captors swung suddenly on them. Shiny needles flashed in their weazened little hands. The steel plunged into the shuddering arms of their victims. At once the blubbering tears ceased; the two little boys grew rigid; a change crept over their pudgy cheeks, swept horribly into their eyes.

Was it my imagination, or the trick of the reddish blaze, or did I actually see a swift transformation, a cunning savagery that transmuted their countenances, that made them obscene companions of the leaping pigmies who shouted and gesticulated with uncontrollable glee?

It all happened so fast that my brain, racked with grief and the sheer terror of it all, had no chance to grasp the thing entire before the two new-seeming pigmies were dragged brutally from the chamber, into a fetid passageway that led God knew where.

Still numbed with what I had seen, still too dazed to do more than sag limply in my rusted irons, I barely realized what had happened, or the sudden hush that had fallen on the circling little beasts.

Then I was galvanized upright; a great wind cleared away the mists that had befouled my mind; a gasp of utter incredulity leaped from my stiffened lips.

Through the same passageway into which the little boys had been dragged, there now emerged two figures. One was all in black, its features hooded with a muffling cowl of red. But the other, half-led, half-pulled along the cruel stones, was—Peggy Whitman!

PEGGY'S tender feet scraped over the pointed rocks, and blood made an indelible trail behind. Her sunny hair fell in a cloud around her terrified face. Her limbs writhed in the iron grip of the shrouded creature.

"Please!" she gasped. "Haven't you glutted your vengeance enough on me? Please let me go. I swear I'll never say another word about your expeditions. I'll—" She saw me then, and her eyes widened.

"Jerry!" she screamed; even as I gasped out her name. "Help! Save me!"

But her captor dragged her roughly into the center of the leaping pigmies, close to the fire, close to the still-motionless figure of the idol.

"Your lover can't save you!" he jeered within the hollow of his hood. "No one can save the bride of Nba! Long has he waited for such a sweet morsel of flesh as you. See how eagerly he awaits his blushing bride; how he rises to consummate the ecstasy of his union with you. If I didn't fear his wrath, and the fury of his worshipers who expect eternal good luck from your marriage, I'd keep you for myself."

There was no mistaking the lust that gleamed through the slits that hid his eyes. There was no mistaking the sudden silence that fell upon the Devil-Devil tribe. I, myself, in spite of the horrible fate that awaited us both, felt a hot flush rise through my body at the luscious charms of the girl I loved.

The red flames played eagerly over every inch of her shrinking form, revealing every sweet secret to savage lust. Her perfect breasts, tender and soft; the smooth shapeliness of her thighs; the white gleam of each rounded curve; were enough to seduce the saintliest anchorite.

Then the silence was suddenly broken. The idol, its basalt face terrible in daubed white and ochre, lumbered stiffly to its feet. To the ponderous accompaniment of stone on stone, it clanked with queer, stiff-legged strides toward the fainting girl. Its sculptured arms reached out to seize its bride!

I yelled; I cursed; I hurled myself at the irons that held me fast to the slimy wall. No one paid any attention to me. The black pigmies had prostrated themselves with unintelligible cries upon the ground at the sight of their god, Nba, who walked like a man. The masked figure chuckled hoarsely.

He caught up the frantic girl in his arms, swung her struggling body aloft, deposited it within the crook of those terrible extended hands.

The elbows flexed. A frightful scream broke from the girl's lips. There was a sickening sound of flesh crunching against hard stone. This was the ghastly marriage—the crushing of soft flesh and tender bones against the stony bosom of the god!

Madness seized upon me at that cry; insanity gave me a strength beyond my own. I leaped forward against handcuffs and leg irons. I did not even feel the cruel bite that seared flesh from the bone. I crashed again in berserk rage.

The irons were old, and eaten through by the rust of years. The granite wall was corroded by the ceaseless drip of foul sea water. Something gave.

With a wild yell that rivalled the savagery of a lion's roar I catapulted forward. The pigmies scrambled to their feet with startled cries. The masked man whirled in alarm.

I smashed through the burning driftwood, scattering the blazing embers, leaped for that thing of black stone that was crushing with horrible strength the life out of the girl I loved.

I hit his body with every ounce of muscle and momentum.

Grinding pains ripped through every fiber of my being. Great lights exploded in my skull. My flesh collided with terrific force against unyielding hardness.

I fell back, moaning sharply with the fierce agony of that crash. My shoulder, where I had hit the basalt idol, snapped with a sickening wrench.

But the god, Nba, had not even staggered at my terrible attack.

THE next instant the pigmies, maddened at my sacrilegious assault upon the god they worshipped, had flung themselves upon me. Knives flashed in their hands. I groaned, tried feebly to defend myself.

I felt them cut deep into my flesh; bestial faces glared into my own; childish black arms raised to drive home the finishing blow. Above the roar and tumult I heard the savage voice of the shrouded man, urging them on to the kill; I heard the wilder and wilder shrieks of Peggy as those terrible arms crushed her closer and closer in the bridal embrace.

A keen blade had searched my side with a slashing thrust; dimly above me I saw a hate-distorted face, deadly steel that was poised at my heart. I tried to avoid the shining death, but a horde of small figures pinned me down, helpless. Suddenly it came!

Then the chamber suddenly echoed with crashing sound. The pigmy screeched, fell sideways. The lethal weapon clattered from his hand.

I heaved upward at the respite, scattering the howling little demons as though they were chaff. The red-hooded figure snarled out terrible oaths; his hand whipped underneath his black robe. But I was upon him like a thunderbolt. My fist caught square on his hidden face. With a strangled cry he fell, face forward, into the glowing bed of embers. His garments burst into flame.

I saw only faintly the men who had come through the passageway that led to the outer island; I barely heard the guns that cracked again and again. I saw only the idol, Nba, slowly crushing the girl I loved within his arms.

I snatched up a heavy iron bar that lay near the wall. Whirling it, I darted for him.

Above the wild uproar that filled the chamber, the screams of the scattering pigmies, the howls of the hooded man as he tried feebly to crawl out of the fiery bed into which I had cast him, the smack of bullets, I heard the strange, unintelligible sound that issued from the god.

His basalt hands dropped to his side. Peggy fell with a dull thud to the ground. We whirled ungainly, ran stiff-legged toward the passageway. I threw the iron bar. It caught him in the small of the back. He staggered a bit; but he ran on. A steel slug smashed into his thigh; yet it did not stop him.

I did not follow. I caught Peggy up in my arms, mumbling endearing words. She opened her pain-swept eyes, smiled. "Thank you, Jerry." Then she fainted.

Two men raced over to me, smoking guns still in their hands. The last pigmy lay twitching on the floor. The rest had fled for safety after their god.

"Lucky we got here in time," growled Jimmy Rean, his eyes popping. "I had the devil's own job sneaking Frazer away from the mob that was howling for his blood. These little devils, after they broke out, had tied him up and thrown him into an abandoned shed on the circus lot. Lucky he knew their language. He heard enough of their jabbering to track them down here with me."

Valentine Frazer grinned sheepishly. "I should never have trusted them. They came back to the United States with me willingly enough. They seemed pretty docile—without the drugs they used in their native mountains to hop themselves up with when they started their blasphemous idol-worship."

"But who then was responsible?" I managed to gasp.

Rean's face hardened. He walked over to the still smoking figure of the hooded man, ripped away the red mask. Underneath, blackened with fire, but still alive, was the once scholarly features of Dwight Ewing, Curator of the Museum and famous archaeologist!

HE stared up at us with insane eyes.

"I hate you all," he mouthed with difficulty. "I hate every smug citizen of Centerville. They gave me an empty post of honor, but they paid me starvation wages. I watched the rest of you wallow in the luxuries you did not need; while I, by far your mental superior, had to count every penny. I wanted to lead expeditions to Africa, to achieve fame and fortune; but not a one of you would back me. Instead, you backed Frazer, and he stole from me the glories that were rightfully my own."

His breathed wheezed. He was dying fast. His voice was becoming fainter. "When Frazer brought back the Devil-Devil tribe, I saw my chance for revenge against him, against you all; and also to get the money you had denied me all my life. I knew the pigmy language; on a former trip I had obtained a supply of the drug that they required to whip them up to their sacrificial rites. Frazer had refused it to them.

"I sneaked into their cabin down at the boat, and made a deal with them. In return for the precious drug, they were to do my bidding. I had them create a reign of terror; I had their god, Nba, kill young girls in terrible fashion; I had them kidnap the small sons of the rich men in town. I threatened to turn them into pigmies if large sums were not paid over at once. The fact that this particular tribe has eyes like those of the white race lent itself to my scheme. I killed Billy Saunders because I thought he had discovered the secret of Nba. After Sam Smith found his son in the swamp, every other father in town would have given me everything he had to avoid a similar fate for his own child."

"But wasn't it Sam's youngster that he shot?"

A horrible grin puffed up Ewing's scorched countenance. "He actually shot one of the pigmies. But Jacky had made a break for it earlier in the night, and to stop him I had to kill him. While pretending to search the swamp, I dragged out the dead body of the pigmy, dumped it into the sea, and replaced it with that of Jacky where I knew you would stumble over it. Actually, all I did was inject some of the drug into the boys I still held captive to make them temporarily mad. Its effect wears off in a few days."

His grin widened. It was a dreadful grin. "Nba!" he started, "Nba was—"

Bright blood bubbled to his lips. His burnt countenance glared up at us; fell back. He would speak no more.

"I think," said Frazer slowly, "that the idol was hollow. I think that the pigmy witch-doctor, whom I had along, knew the secret of its mechanism. He could have inserted himself into the hollow stone, and worked its stone hands and legs by means of levers. Back in Tanganyika he was a power among the superstitious savages; he alone controlled the god that walked like a man. Obviously he and Ewing were accomplices."

It may have been so. There is no way of telling. For those of the pigmies who escaped had fallen into the sea, and were drowned. The swift tide carried their bodies far out. Only a few were ever recovered.

But Nba, the idol of stone, disappeared completely. Had he fallen into the sea, he should have sunk into the shallow offshore surf. But no amount of dredging or dragging of the bottom ever brought his obscene form to light.

YEARS after, a returned explorer from Tanganyika mentioned something about a basalt idol that walked like a man, and was worshipped as a god in the recesses of the mountains. He had seen it once, and barely escaped with his life.

His description of it tallied exactly with that of the stone monster that had been in Centerville in that terrible time of which Peggy and I, now happily married, never speak.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.