RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

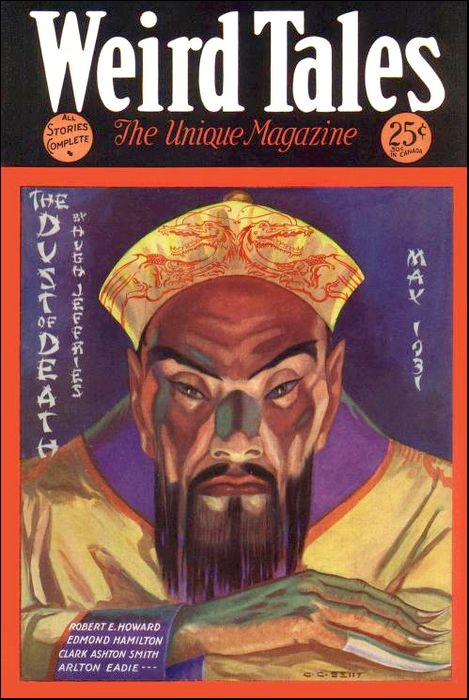

Weird Tales, Apr/May 1931, with "The Dead-Alive"

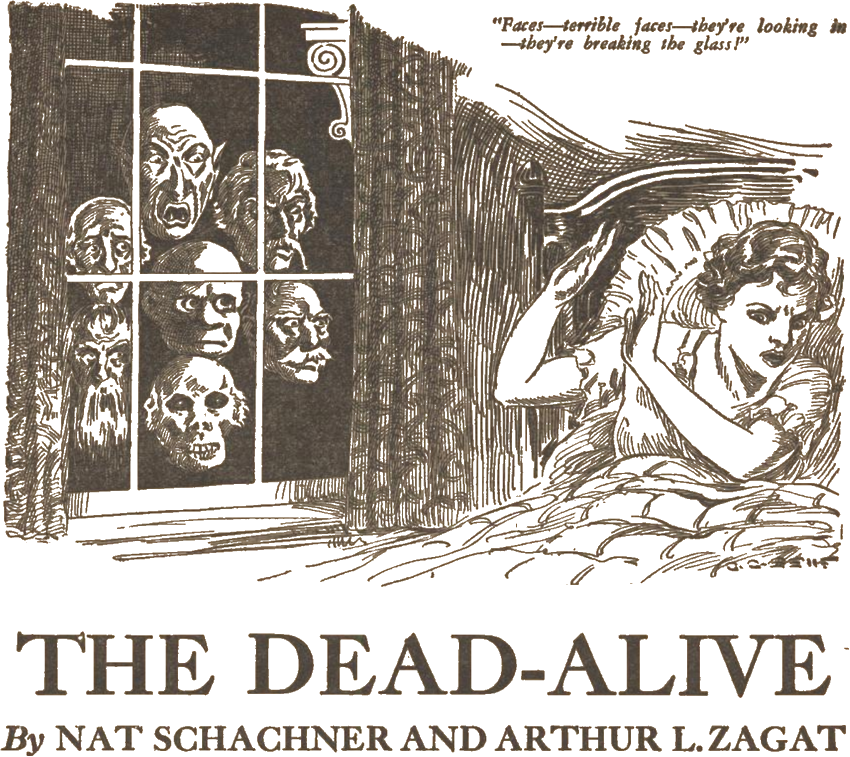

A shivery, blood-chilling, goose-flesh story of violated

graveyards and cadavers that walked in the night.

ON A brilliant, sunshiny day in May of 1935, the unspeakable, unnameable crime had been committed! Carelessly, gayly the world moved in its accustomed grooves; men performed their routine tasks restlessly, haunted by visions of deep crystal pools overshadowed by rustling birches, the graceful arching leap of a speckled trout, the singing whine of line over reel; young lovers walked with a certain elate springiness, the wine of life flooding their veins. Not yet did mankind realize the import, the vileness of that deed. Soon, too soon, would a pall of horror overshadow the burgeoning earth.

On a like brilliant, sunshiny day in June of 1935, sat at his desk Hartley—to his friends, Buck—Saunders, erstwhile idol of football enthusiasts, All-American back—Princeton, 1934; now bond salesman for the conservative investment house of Clarke, Lambert & Co. But there was no spring or summer in his soul; he stared through the open window at the panorama of river traffic with blank, unseeing eyes. What mattered to him at this time sunshine and laughter, high-pressure salesmanship and the busy hum of men?

Only yesterday—ages ago it seemed—he had buried his father, his gentle, understanding father, stricken suddenly. Heart failure, the doctors said. Tragically he had seen the lifeless form to its final abode—a cemetery in the Westchester hills.

By sheer force of will, he came down to the office this day, seeking surcease of sorrow in humdrum tasks. The staff had been properly sympathetic; but once he was at his desk, neatly labeled in brass with his formal name, the mass of papers awaiting him seemed devoid of meaning, of any content. So he shoved them aside, and stared listlessly into nothingness.

The telephone jangled. He ignored it. It rang louder, more insistently. Annoyed, Buck removed the receiver and placed it to his ear.

"Mr. Saunders?" It was the switchboard operator.

"Yes, what is it?" he asked impatiently.

"I have a call for you. Just a moment."

There was a little delay in making the connection. He was sorely tempted to hang up. Then he heard a brusk masculine voice.

"Mr. Hartley Saunders?" it queried.

"Well, what of it?" Damn these fools. Why couldn't they leave him alone!

"Police Headquarters speaking. Your father, John Saunders, was buried yesterday at Mountville Cemetery?"

A stab of pain shot through him at the matter-of-fact statement.

"Yes. Why do you ask?"

"This is Detective Sergeant Riley. We have some important information we'd like to check up with you. Come down here to see me at once."

"But what is it all about—can't you tell me now?"

"Sorry, but that's impossible. I can't explain over the phone. Will expect you in half an hour. Good-bye."

Buck started to remonstrate, when he discovered that the line was dead.

Gone now was his apathy. His mind was keen and alert as ever. What did Police Headquarters know of his father's death and burial, and why this peremptory summons? A hundred hypotheses formed and faded in his whirling thoughts, and all were rejected as fantastic. There was only one thing to do: follow directions and see this Riley. Mechanically he put on his hat, muttered an unintelligible explanation to his chief, and fled out of the door.

A TAXI hurried over at his uplifted finger, the door slammed behind him, and he was speeding downtown.

The ride seemed interminable, but it was only twenty minutes before he was deposited in front of the formidable-looking building. He gave his name and errand to the stout policeman lolling at the front desk. Evidently he was expected, for almost immediately he was ushered into the presence of Detective Sergeant Riley.

The big, strong-jawed Irishman, iron-gray at the temples, leaned back in his chair and surveyed him thoughtfully a while. Buck grew restless under the protracted scrutiny and was about to demand an explanation, when the detective commenced abruptly.

"You're Hartley Saunders. Your father was buried in Mountville yesterday." He seemed to be ticking off invisible points.

Buck flinched, but nodded assent.

"This morning," Riley continued, "his grave was found open, the lid of the casket pried off, and his body removed. It has vanished without leaving a trace." Buck jumped to his feet with an exclamation.

"What! my father's body gone? But where—what happened——" he gasped for words.

Not unkindly, the big detective motioned him back to his seat.

"That is just what we are trying to find out," he explained. "We have nothing to go on as yet. Let me give you the facts. Early this morning we received a call for assistance from the local police. I was assigned to the job. I wasn't exactly tickled about going—but I went. Orders are orders.

"When I reached the cemetery, I found a county detective in charge. It was no ordinary case of body-snatching, you must understand. The freshly made grave had been opened, the dirt was scattered all over the other graves, not in mounds, as you'd expect if dug up by a spade, but as if"—he hesitated for a moment—"as if it had come up in handfuls and been strewn about. The casket cover was violently wrenched open; yet we could find no marks on the wood, as would surely appear if crowbars or any mechanical implements were used to pry it up."

Buck Saunders was listening with growing horror, yet he remarked the queer emphasis the detective placed on the word "mechanical".

Riley continued his story. "The body was removed—clean vanished. There was a watchman on the grounds. They found him early this morning, walking about aimlessly, making queer, unintelligible noises. The police questioned him, but it was no use. The man was mad, stark gibbering mad. Only a few words could be understood in his moanings. Something about corpses that walked—ghosts. He died this noon, still raving!"

The big detective paused, and looked at his visitor strangely. Buck sat stricken, unable to speak. His poor father, thus to be denied peace even in his grave!

With elaborate casualness the policeman threw his bombshell. "And I forgot to tell you—there were no spade-marks down the sides of the grave, but we did find the marks of fingers dug deep into the earthen walls."

Incredulously, Buck grasped the full horror of this simple statement. "Do you mean that men dug up my father's body, using only their fingers as tools?"

Gravely the detective nodded his head. "Impossible as it sounds, that seems the only logical conclusion from all the evidence. Yet if the grave-robbers were only men, why did the watchman go mad? There were no marks of violence on him—he had not been attacked. And what was that cryptic reference to dead men who walk? No—something happened last night—that watchman saw something so unbelievably horrible that it twisted his brain into madness. What it is we don't know yet, but we're going to find out," he concluded grimly.

Buck's face had grown hard and stern during the recital of this weird tale. Grim determination showed itself. "And I—I am going to run down these grave-robbers, these ghouls, whatever they prove themselves to be—men or fiends out of Hell!"

Riley nodded in understanding. "There is another thing, Mr. Saunders. We have been keeping it under cover—the newspapers know nothing about it yet, but this is not the only case. Within the past two weeks, there have been reports of similar outrages in a dozen cemeteries widely scattered over southern and eastern New York. In every instance the clues were the same—no spade or lever was used, and in each case clutching fingers had dug deep into the soil."

Buck arose; the very marrow in his bones seemed frozen; the iron had entered his soul. He extended his hand. "Thank you very much for telling me all this. I've no doubt you will do your utmost to run down these fiends. But I shall not rest from this day on, until the guilty are brought to justice."

The brawny officer took his hand. "Never fear, we'll get them. But you, my lad, careful is the word. Don't try anything rash. You're up against something uncanny—horrible. Look out it doesn't get you."

"Don't worry; I can take care of myself," responded Buck grimly. Looking at his six feet of brawn and muscle, hardened on many a football field, the steely blue eyes and the firm line of his jaw, Riley was forced to confess that this confident young man would prove a formidable antagonist for any one.

BACK to the office Buck rode. His plans were formulated. A tangled excuse and he readily obtained leave of absence, his superior shaking his head sadly at the retreating figure. Once home he equipped himself with flashlight and automatic, and took an evening train to Mountville. As night fell dark and mysterious over the cemetery, white marble glimmering ghostly, he took his station, determined to watch the whole night through.

Morning found him still watching, soaked with the gray mists of early dawn, cramped with crouching, reeling from fatigue—but the vigil was fruitless. Mysterious sounds and noises there had been a-plenty, but the marauders had not returned.

Night after night Buck kept his lonely vigil, but in vain, Whatever it was that had ravaged the grave, it had no evident intention of returning.

Chilled and racked with the weariness of tense, sleepless watches, soul steeped in bitter anguish, Saunders was forced to admit defeat. Reluctantly he returned to the city. Perhaps, he thought, the police had been able to discover something in his absence. Eagerly he phoned Riley.

"No, my lad," boomed the hearty Irish voice, "we're as far from a solution as when we started. Farther; for reports of body-snatchings are coming in now thick and fast, from all over the state. Hundreds of them. All the same way. Must be a large group working. We've found out this though: in every single instance the stolen corpse had been freshly buried! No decayed bodies are taken. We've sent out secret instructions to have guards detailed to each cemetery immediately after a funeral. Didn't see anything, did you? No? Mighty lucky for you, I'm thinking. Don't try it again—there's something very horrible about it all. It'll break into the newspapers any day now—can't keep it away from them much longer. Good-bye."

And sure enough, next morning horror flaunted and screamed in huge headlines across the front page.

The fashionable Kenesco Cemetery was the milieu of a frightful crime. Two funeral processions had converged on that famous burial-ground the day before—one, that of an internationally famous financier; the other, of a beautiful society girl, the season's debutante, carried off untimely in the first blush of youth and happiness. Everything had gone according to schedule. The great concourse of friends and mourning relatives, the banked masses of floral tributes, the intoning of solemn rituals, the careful lowering of expensive bronze caskets, the tamping down of the all-embracing earth, the orderly dispersal of those who had gathered in anguish or curiosity. The earthly drama was over.

Alas, not yet! As evening cast its lengthening shadows over the wilderness of marble, two heavily armed state troopers, picked men, proven in many a desperate encounter, took their station in the shelter of a huge mausoleum on a knoll overlooking the graves. Their instructions were direct and succinct: "If any man, or beast, or thing, approaches the graves, shoot, and shoot to kill."

At two in the morning, a belated commuter hurrying home along a road past the great cemetery heard a shot crash through the blackness of the night. As he paused, affrighted, three others followed in quick succession. Silence. Then the sound of terrific struggle, and a piercing scream split the air. As it rose, it choked and strangled into a gurgling rattle. The commuter's blood froze in his veins; his feet were rooted to the spot. Then came another sound—an unearthly moaning, wailing, that rose and fell in a gamut of mortal agony. Like the unutterable cries of a lost soul in deadly torment, he described it afterward.

He paused not in his going. Deadly fear gave wings to his speed, nor did he slacken till he threw himself into bed, fully clothed, there to cower and tremble under blankets the balance of the night.

That morning, the sergeant of the troop, making his rounds, came upon a frightful scene. The two fresh graves were yawning wide, the bodies had disappeared! Near by, on the ground, lay the crumpled figure of a trooper. Eyes protruding half out of their sockets, mouth twisted in a final desperate scream, there wag that upon his face that caused the sergeant, hardened veteran of the World War, to shudder and avert his gaze. That face, those eyes, had witnessed unutterable, unspeakable horrors. Near him lay his heavy service revolver, three shells exploded. About his neck were the deep red grooves of clawing fingers.

The other trooper was gone. An hour later he was found miles away, running and stumbling across a woodland patch, gun still clutched in hand, one cartridge fired—mad, stark mad., No human sounds came from his tortured throat, only rasping, frightful screams. He died at noon in a strait jacket, still screaming.

Impressions had been taken of every metallic object on the strangled trooper's uniform for possible finger prints, the account read. The experts were working on them now.

Buck read along with renewed horror. His youthful pleasant face set in hard lines of determination. A cold purposeful light steeled his eyes. "By Heaven, I shall run this down if it takes my life," he swore to himself. Job, vocation, livelihood—all were forgotten.

THAT afternoon he saw Riley at headquarters. The detective greeted him cordially. To him Buck stated his determination, and begged to be allowed to assist.

Riley looked at him quizzically; then his gaze sobered. "Boy, you don't know what you want to let yourself in for," he said gravely. "I've handled many crimes in my day, but this is something different. There are forces at work here that I'm afraid even to think of. It's going to be dangerous—damned dangerous."

"Are you afraid?" Buck shot at him. The big man stiffened. "No one yet has dared say to Tim Riley's face that he's afraid, and don't you be the first one," he warned.

"No offense, sergeant, but I'm not afraid either. I think I can help on this—and I want to work with you. I can handle a gun pretty well, too. What do you say?"

Thoughtfully the policeman surveyed the eager figure before him, the stamped determination of it, the snapped set of the jaws. Then: "It's a little irregular, but I'll chance it. You're welcome to help."

Silently the two men shook hands.

"Now," commenced Riley, as they resumed their seats, "now that you're my unofficial assistant, I'll tell you of something that's absolutely unbelievable—so unbelievable that I don't credit it myself. Listen to this. You must have read in the newspapers that impressions were taken for finger prints on the dead body."

Buck nodded.

"Well," the detective seemed to be choosing his words, "our finger print expert reports that he found a well-defined thumb print on the button of the trooper's blouse."

Excitedly Buck leaned forward. At last something definite, something tangible to work on.

"He also reported," continued Riley slowly, "that he checked it on our records, and he found its mate. It is the thumb print of Tony the Mug, gangster, thug, murderer. We have his complete record on file."

An exclamation of joy burst from Buck. The mystery was solved. Find Tony the Mug, break up his gang, and the nightmares would cease. But there was no answering look of elation in the Irishman's eye. Instead, a strange pall of nameless horror seemed to settle on him.

Unheeding, Buck asked, "You've sent out orders to search for and arrest him, of course?"

"No, I have not," the detective answered slowly.

"But why not?" came the surprised reply. Then, and then only, did he look up and see the strangeness—almost the dread—on Riley's face.

"Because," the policeman had great difficulty in enunciating the words, "because—Tony the Mug—was electrocuted for murder at Auburn Prison two weeks ago!"

With incredulous horror Buck jumped to his feet. "But—but," he gasped, his heart pounded madly, "that is impossible—it can not be—my God, it must not be!"

The detective agreed, soberly. "Yet there are the facts."

Buck's brain whirled with horror. Vehemently he sought an outlet, a solution. Yes, yes, he had it! Aloud he sobbed his relief from the unutterable implication of those terrible facts.

Riley looked at him inquiringly.

"Of course, it's obvious," the words came tumbling. "This Tony was not killed by the current, only shocked into unconsciousness. Then when his relatives took away the 'dead' body, they were able to resuscitate him. There have been cases like that. And now he is robbing graves. That's it." The sweat dried on his forehead at his own easy explanation.

"Yes," agreed Riley, in a curious, flat tone. "I've heard of those cases. But there is no question that Tony is dead. The prison doctor pronounced him so. His body lay for a day, and since no one claimed it, he was buried in the prison cemetery the following day. Besides"—he leaned forward—"Tony the Mug's grave was opened two nights later, and his body removed."

"God," Buck felt weak, "what are we up against?"

"I don't know as yet, but I'll find out soon," was the grim rejoinder. He swung around, and spoke abruptly. "I'm going out tonight to watch a little cemetery I have in mind—Hopeville—it hasn't been disturbed yet. I've an idea an attempt will be made on it tonight. The larger ones have each a company of ten troopers on guard."

Buck arose. "I'll go with you."

Riley eyed him keenly. "Very well, meet me here at nine-thirty sharp. I'll have the police car waiting and we'll drive out."

PROMPTLY at nine-thirty Buck presented himself at headquarters. Riley was obviously waiting for him.

"All right, lad, let's go. Here, take this." He opened the drawer of his desk, and brought out a regulation police automatic. "Slip this in your pocket—you may need it. And these flashlights, too, one for each of us."

Buck took the proffered weapon and flashlight, and they started for the door. "Hold on a minute, my boy, until I get something else." A sudden thought had occurred to the detective and he turned back. He opened a wardrobe, and took out—a cavalry saber!

He met Saunders' surprised questioning stare somewhat sheepishly. "Just a relic of my cavalry adventures in the World War," he explained. "Had enlisted in that arm of the service for the duration of the war—knew how to handle horses pretty well. They gave me this pretty little toy and some spurs, then shipped me across. There we were bundled into a troop train—huit chevaux, quarante hommes—and rode standing up to the front. That sign on the cattle car was the only smell of a horse I had. All through the war I was a bloody doughboy—unhorsed."

Buck laughed. "And you've been on your legs ever since. But why the paraphernalia tonight? We're not attending a lodge meeting."

The big Irishman was good-humored. "All right, my lad, have your little joke. But something tells me—just another hunch—that this old saber may see more service tonight than it did in France. Remember those troopers up at Kenesco fired four shots—and hurt no one. They were dead shots, too."

Out into the anteroom they walked, the detective swinging the heavy weapon like a cane. The idling policemen stared in surprise; then as they moved toward the outer door, Buck distinctly heard the sound of snickering behind him. He stole a glance sideways at his companion and was mightily amused to see a brick-red slowly suffusing neck and countenance, but no other sign that he too had heard. Out they clanked into the street, Riley shutting the door behind him with a bang.

Hastily the detective gained the waiting car at the curb, and deposited his ungainly weapon with a sigh of relief. Buck seated himself at his side. Silently the car slipped into gear, and they were off. Up Fifth Avenue, through the Concourse, left turn to the Bronx River Parkway, on to White Plains they sped. There they turned right, branched off on a dirt road, and followed the twisting ribbon through the night toward Hopeville. A full two hours' drive. Not much was spoken by the two men—they were too busy with their own thoughts.

With scream of brakes and skid of tires, the car came to an abrupt halt under the pitchy darkness of a huge oak. "Here we are," whispered Riley. He switched out the lights. The night was black—there was no moon. Buck heard him fumbling; then a light leaped into being, and a glowing circle stabbed the darkness.

They got out somewhat stiffly, the policeman taking the cavalry saber. Over on the left glimmered faintly white headstones. They were at the cemetery. Two circles of light dancing irregularly on the broken ground, the two men cautiously picked their way through the marble wilderness until they reached a slight rise on which was built a granite mausoleum.

"Switch off your light," Riley whispered, snapping his off; "we park here for the night. There's a man buried yesterday in the grave in front of us."

Buck hastened to obey, and blackness unrelieved wrapt them about with an almost physical impact. Saunders glanced at his wrist. The faint luminescence of his radium wrist watch showed eleven-thirty.

"Keep your gun ready at hand, lad, but don't be in any hurry to shoot, no matter what you see or hear. Wait till I give the word, and for God's sake, no noise." He could hear the ex-cavalryman's sword softly deposited on the ground. They crouched, waiting, they knew not for what.

THE minutes dragged by. Now the moon was rising, a huge brass bowl climbing up the eastern horizon. A dull coppery illumination tinged the ground and gravestones uncannily—a weird half-light almost impenetrable to mortal eye. Nervously, Buck glanced at his watch again. One minute to midnight! His heart was thumping madly; ghosts of the outraged dead clustered and formed threateningly; faint gibberings and rustlings were conjured up by his heated imagination.

A hand gripped his wrist. Buck started violently, a cry of fear smothered in his throat. "Sssh!" came Riley's tense whisper; "do you hear it?"

Buck strained his ears. Sure enough, up from the road came the faint tramp, tramp of feet. Nearer and nearer, louder now—the steady ordered thump of feet marching in unison, like soldiers on parade; mechanical though, slow, spaced, lift, eternity of waiting, down on the ground, like a slow-motion picture of the old German goose-step. Buck felt his flesh prickle, and shudders coursed wildly up and down his spine.

Riley was whispering fiercely. "Get your gun ready, they're coming. Down low, so they can't see us. Don't move till I give the word." Saunders heard him pick up the saber. Down they crouched, waiting.

The noise of marching moved toward than like a wave, nearer, ever nearer. God! thought Bock, are they coming for us? Panic seized him, human flesh could not bear that frightful thump-thump. Just as he was on the verge of screaming, his finger tightened on the trigger in spite of warning, the horrible sound ceased. They had stopped, not thirty feet away.

Buck strained to pierce that weird unearthly light. Dimly to be descried were five figures—men, thank God!" wavering shadows, hardly visible. They clustered about the freshly made grave.

Then, to Buck's unutterable horror, the shadows stooped suddenly and clawed at the ground. Up into the air flew great handfuls of earth. With incredible speed the digging continued, the air was thick with flying dirt, pebbles fell rattling. Already the ghostly figures were half immersed in the opening grave.

Loudly, fiercely, Riley's voice shattered the night. "Hands up, you there, don't move an inch. We've got you covered."

Up went Buck's pistol, ready to shoot. Incredibly, there was no response. The silent figures kept on digging, clawing the earth, unmindful of the threat. It was ominous in its implications.

The detective's flashlight pierced the gloom, the wide circle of light played on those forms. Even as the glare enfolded them, the figures straightened, and as one being, slowly turned their heads toward the crouching pair.

"Merciful Mary, Mother of Saints!" burst a hoarse cry from the Irishman. Buck tried to scream, but couldn't. Never, to his dying day, would he forget that nightmare sight!

Ghastly gray were those faces—the corpse-like pallor of those who have passed beyond the bourne. Lank hair that lay damp on pallid foreheads. Cheeks that were oddly sunken, gray skin that stretched unpleasantly tight over protruding cheekbones; hands that hung loosely, ending in bony claw-fingers that twitched incessantly. An indefinable air of decay and corruption enveloped them. But most horrible of all—their eyes. Great fixed pupils that stared unwinking at the dazzling beams—stared at the pair, through them, and beyond them. The eyes of somnambulists, that betrayed no warm emotion, no human feeling, only the frightful stare of blankness—as though, Buck thought in terror, as though there were no minds behind them. He could see no eyelids, only the fixed unwinking eyes.

Even as they watched, paralyzed with fright, the dread figures galvanized into movement. Up went their right legs uniformly, down they came together, and slowly they advanced—on the crouching pair. Buck could hear Riley mumbling some old forgotten prayer. The pace grew faster—they broke into a trot, still the legs rising and falling together.

"Shoot!" screamed Tim Riley; "shoot before these banshees get us!"

Two pistols cracked simultaneously. With not a pause, the nightmares came on. Again and again the guns spoke. The bullets must have found their marks, but steadily, uninterruptedly the figures advanced. Buck felt his reason giving way under the horror.

"I knew it!" yelled the terrified detective; "they're not human, they're banshees! Run for your life." Up he caught his saber, and commenced to run. Saunders did not hesitate—he was right alongside, running as he had never run before.

On they sped, stumbling, tripping, crashing into gravestones, until their breathing came in great whistling sobs, Riley holding on to his great sword with desperate effort.

Buck glanced fearfully behind. The Things were running in unison, but one figure had pulled ahead, not twenty yards behind. "For God's sake, drop that damned sword, and run. It's right behind us," he gasped.

Too spent for words, the detective could only shake his head violently in the negative. Another hundred yards they ran, and fell. Again Saunders looked over his shoulder. The hideous Thing was only ten yards behind, and running stiffly, mechanically. He drew his gun, whirled and shot. Still it came on. Gasping with sudden fury, Riley turned, "Damn you," he screamed; "man, ghost or banshee, I run no farther. Come on if you want cold steel."

The Gray Thing rushed toward him. The big Irishman sidestepped swiftly, and swung the saber high. Down it descended with frightful force, caught the figure full on the shoulder. Such was the force of the blow that it sheared through shoulder and arm, and the arm fell thudding to the ground. The creature's momentum carried it on a while; then it wheeled and started back. The moonlight shone brightly on the gaping shoulder. The flesh was pallid gray, and not a drop of blood oozed from the wound. Back it ran, unmindful of its arm!

The men stared aghast. With a great yell, Riley whirled his sword and threw it at the advancing figure with all his strength. It caught the Thing full on the face, and knocked it to the ground.

The moment's respite was enough. Like a flash, the two men ran down the slope to the road, on wings of terror. Even as they gained the car, they saw five figures, one without an arm, descending the slope after them.

With trembling fingers Riley turned the switch, clashed into high, and the car was roaring drunkenly down the road—back to humankind and sanity.

FOR a week Buck lay delirious—in the throes of a violent brain fever. When he finally came to, weak but normal in pulse and mind, he found Tim Riley seated at his bedside.

"Well, lad, I sure am glad to see you out of it. You had a rough time, all right."

"And you, old-timer, how do you feel?"

"O.K. now. Was laid up for two days, but snapped out of it. I'm too tough to knuckle under long."

"What's been happening, Tim, while I've been lying here?" inquired Buck weakly.

"Here, you, go back to sleep," responded the detective gruffly. "You're not well yet by a long shot. See you in a couple of days and tell you all the news." With that Riley left abruptly.

True to his promise, the detective called two days later. Buck was up now, feeling as strong as ever, and rearing to go. Only that fool nurse of his insisted on his staying in, and refused steadily to get him any papers.

After the first cordial salutations, they sat down comfortably to talk. Only now did Buck see the drawn, haggard look on the policeman's face.

"Tell me what's been happening," urged Saunders.

"Hell's broken loose," Riley replied, slowly. "And when I say Hell, I mean it literally. Those damned banshees"—he crossed himself devoutly, this son of old Erin—"are no longer haunting graves. They're swarming over the whole countryside. People are scared to death. When it comes dark, every one locks himself up tight; they don't dare go out. Last Wednesday a child of twelve disappeared near Schoharie; she hasn't been found yet. The next night a woman was found dead on the highway, a little out of West Point. She was strangled—hideously. Then it spread down through Jersey and over into Westchester. Men have been frightened out of their wits, meeting one of them suddenly on a dark road. They have been shot at, but bullets don't hurt them. We know that." He shuddered. "I don't know where it's going to end, but if they aren't shipped back to Hell soon——" The pause was significant.

Buck had been listening in rapt attention. "They nearly did for me, Tim. But just wait until I get back on my legs again. I've got something glimmering in my mind."

The detective arose. "O.K., lad, just you rest up first," he said soothingly. "Then we'll dope something out together. Meanwhile troops are patrolling all the main roads. So long, and take good care of yourself."

BUCK watched the burly form disappear through the doorway, then fell back exhausted. He was weaker than he thought.

He was dozing off when the door flew open and a girl darted into the room.

"Buck, darling, what has happened to you?" she cried.

"Ruth—you here!" the sick man sat up in astonishment. "Where on earth did you come from? I thought you were out on the coast with your folks."

"I was," she declared airily, "but I became fed up with the eternal sunshine and the Native Sons, so I decided to come back East—and here I am."

Buck gazed tenderly at his fiancée, Ruth Forsythe. Dark, vivacious, black eyes dancing, features finely modelled, adorably pursed mouth, she was a sight to make any normal male's heart beat a bit faster. There flashed into Saunders' mind the memory of that day, when, asked to choose between himself and Jim Carruthers, brilliant classmate of his at college, both desperately in love with Ruth, she had unhesitatingly turned to him, and kissed him full on the mouth. Nor could he forget the distorted features of Jim, as he saw the girl he loved in his rival's arms. Muttering an imprecation, he had seized his hat, clapped it violently on his head, and departed like a storm out of the house—and out of sight. From that day on, no one had seen him again. That was six months ago. What a pity, too! The man was a brilliant biologist; his professors had envisioned a marvelous career for him.

"Why do you look at me so strangely, dearest?" asked Ruth, somewhat startled.

Buck came to himself with a start. "Nothing, darling. Just thinking of old times, and so tickled to see you again."

"But, darling," she seated herself at his side, all anxiety, "what has happened to you? The nurse tells me you staggered in early one morning talking incoherently and took to bed at once with high fever. Tell me all about it."

So Buck, one arm comfortably around the girl, told her all about it, omitting nothing from the desecration of his father's grave to his last desperate adventure.

As he proceeded, Ruth's eyes widened with the horror of it all, and her arms tightened about him. "Oh you poor, poor boy," she crooned, "how glad I am you are alive! No wonder you almost went mad from it." She shuddered at the thought.

"Now you just lie down and rest," she urged; "you're still very weak. "I'll go home, unpack, and be here first thing in the morning to be with you."

"But," Buck objected, "your house is closed—there is no one on the place."

"I have the keys. And I'm not afraid to sleep alone."

"No, you must not go—I'm afraid for you. It's country where you are; there are no houses close by. Those terrible Things are filtering down through Westchester, too."

Laughingly, Ruth answered his protestations. It was all nonsense! The morning paper gave the nearest reported visitation some thirty miles north, so there was nothing to be alarmed about. Besides, it was just for the night, drop some clothes, pick up some others, and come back to town.

So Buck was overborne against his will. He saw her go, and presentiment of evil clamored at his heart. He called after her to return, not to go, but it was too late—she was gone.

Night came. The nurse entered, took his temperature, counted his pulse, did the numerous little things appropriate to a sickroom, and withdrew.

The hall clock struck ten, but Buck could not sleep. Anxiety for Ruth tormented him. Why had he let her go? The hour of midnight chimed, and still he was awake. He was cursing himself for a fool.

Hardly had the last note faded on the air, when the sharp ringing of the telephone took up the refrain. Half sick with apprehension, Saunders was out of bed in a jiffy, snatched up a dressing-gown, and ran to answer.

With hand that trembled, he picked up the receiver. "Hulloa!"

Ruth's voice came to him, taut, desperate in its urgency.

"Buck, Buck, something's at my window. Faces—terrible faces, they're looking in—they're breaking the glass. Oh my God, Buck, do something! Save me!" Her voice rose to a scream!

Frantically he answered. "Quick, hang up, call police at once. I'll phone too, and come right away."

At the other end he heard a sob of relief. "Buck—at the other window, I see Jim. Jim Carruthers. He's breaking in. He'll save me—save me! I'm going to him. Good-bye."

Buck was almost crazy with anguish. He heard the receiver drop, heard footsteps, heard a call, then a scream of terror, a scream that choked and was still.

In frantic haste he dressed. His heart pounded and hammered; his brain reeled. "God," he prayed, "what have they done to my darling, my own, my Ruth? If anything happened, I'll tear them to pieces with my hands. Devils, banshees or men!"

In one minute he was dashing out of the darkened silent house. In another minute he had run his car out of the garage, swung about on the road to Tilton Heights, where the Forsythes had their home; and throttle wide open, he roared into the night.

The speedometer showed fifty miles, sixty, sixty-five. "Hurry, hurry!" beat his heart. "Faster, faster," raced the blood in his veins. Grimly he held the car to the road, as it careened over the lonely concrete. It was fifteen miles. "Let me get there in time," he prayed.

Jim—what was Jim doing out there? He had disappeared months ago. He had loved Ruth once. Why was he breaking through one window, and the Things through another. Why had Ruth's call turned to a scream?

A blinding illumination lit up everything in Buck's mind. That was it! Jim Carruthers, Jim—was responsible for it all! These horrors—they were connected in some way with Jim. He had abducted Ruth. A fury of rage swept over Buck. The damned beast, the cowardly hound! He'd make him pay; he'd find that scoundrel even if he hid himself in the bowels of the earth.

WITH screaming brakes the car slithered to a stop. It was the Forsythe's house. Before the car stopped rolling, Saunders was out of it, flashlight in hand, and up the wide stone steps. Furiously he pounded on the door. There was no answer. With all his strength he heaved against it, but it was too sturdy to break down. Abandoning the front, Buck ran around the side of the house, frantic with despair. What he saw brought him to a dead halt—heartsick. Two of the casement windows giving on the living-room were shattered, shards of broken glass were scattered over the green lawn, and the turf under the window was trampled as though with many feet.

In a moment he was pulling himself through the jagged pane, unmindful of the sharp edges that lacerated and tore his flesh. The flashlight lit up a scene of destruction; fragments of shattered vases covered the rumpled rugs, the telephone dragged on the floor, the receiver off. In plain language the room told its story of a struggle and abduction. A faint noise seemed to emanate from somewhere—a buzzing that was ominous in the dead silence of that desolation. Instantly Buck was on the alert, gun drawn, and flashing wide arcs over the room. Nothing appeared, but the buzz continued. As the telephone swam into the circle of light, Saunders found the explanation. Central was trying to signal that the receiver was off the hook.

Cautiously, thoroughly, Buck searched through the house. Ruth was gone. Like a vacant shell, bereft of life, of more than life—empty, resonant, mourning its lost soul, seemed the old mansion.

Back to the ground underneath the broken windows went the tortured lover. He picked up the trail of trampled grass, followed it down to the road, where it vanished into the stony macadam. Buck felt the anguish of utter helplessness sweep over him. What could be done now?—how discover the whereabouts of his beloved? As he thought of Ruth struggling in the arms of those foul monsters; of Jim Carruthers, so unaccountably entangled in the ravelled skein of events, a groan burst from him, that gave way to the flame of a desperate resolve. Find Carruthers, and he would find Ruth. Find Carruthers, and the mystery of the terrible Things would be solved. He was sure of it. But—how find his former classmate?

Once more he returned to the trampled areas beneath the windows. Methodically, painstakingly, he searched the ground, foot by foot, in the gleam of the flashlight. Fruitless—all in vain. He was giving up—turning away heavy-hearted, when the swing of his hand brought an outer strip into the area of illumination. Ha! what was that?

The excited searcher pounced upon it. A crumpled dirty piece of paper. Carefully, tremblingly he smoothed it. A torn segment of a map—a map of New York State. One of those maps that are given away at filling-stations. Buck grew tense; on it was blue-pencilled a small circle. What did the circle enclose? He strained to read the name of the town. Birdkill, in the Catskills. A small village, evidently. He had never heard of it before.

A fierce exultation surged through his veins. At last—a definite clue. Evidently dropped by one of the ravishers, possibly Carruthers, it bespoke only one thing! There was the hiding-place; the focus of the evil that was invading the land!

Buck's features tightened into grim hard lines. He was going up there—alone, to combat this menace, to rescue his loved one.

AS dusk was falling, Buck alighted at the little town of Birdkill, high in the Catskills. Through some quirk of fortune this sleepy little village had escaped the annual throng of vacation-seekers from the great city. Its ten or fifteen frame houses, its Eagle Hotel, its general store and post-office, preserved the rural atmosphere of a century ago. The whole region about partook of this atmosphere.

A few well-tended farms, a concrete road or two, a cheap automobile and a good radio set in every home, these were all of modernity to be found in the vicinage.

Directed by one of the little group engaged in the nocturnal thrill of seeing the train come in, Buck found the village hotel. The accommodations offered were quite satisfactory, though primitive. In its furnishings, the room was immaculately clean. Warned by the clangor of a hand-wielded bell, Buck took a hurried wash-up in the great china bowl, and descended to "supper."

Having disposed of the heaping platters of plain but wholesome food set before him, Saunders accompanied his few fellow guests to the "piazza," and ensconced himself in one of its wooden rockers. He found himself between the village postmaster and the station agent, bachelors both. Luck favored him. The two best sources of information for miles around were his neighbors.

"First trip to Birdkill?" Postmaster Simpson essayed the first step in the investigation undergone by every newcomer. Buck expected this and had his story ready.

"Why, yes. I've been working pretty hard on some new radio patents, and decided to take a vacation. Wanted to get away from the usual summer resort, with its pesky girls and flash sports. Heard that you folks up here didn't like any of that sort of nonsense, so I came up. Looks like just what I wanted. You don't get many strangers around here, do you?"

"Nope. Two, three drummers; 'sabout all. Mostly we keep ourselves to ourselves. Queer duck came through here 'bout six months ago', though. Fellow 'bout your age, too. Got off Number Four one morning, and had the confoundest mess o' boxes put off the baggage car——"

The station agent interrupted. "Ten big wood cases, twenty small boxes, three big trunks. They was all marked 'fragile,' too. A body'd think they was full of eggs, the way he fussed. Wanted to know if they'd be safe till next morning. 'Sif anybody wanted to touch his old boxes. They was danged heavy too. And not a crack in 'em anywhere that a body could look through."

"Didn't stop here mor'n a half-hour." Simpson took up the tale. "Hired him a flivver from Jenkins' livery stable, hauled out a map he had, then shot off up Black Mountain. Couldn't make out what he wanted up there. Nothing but woods, and the old mill. Nobody lives there. Ain't been anybody up that way since Old Man Thompson died and the mill at the falls shut down.

"He came back next day, and got him a flivver truck at Jenkins'. Smith here, and Tom Durkin's boy helped him load his boxes. But he wouldn't take any one along to help him unload. Ned Durkin told him he wouldn't charge nuthing: just wanted the ride. But the stranger cussed and swore. Said he didn't want any—any——"

"Interlopers," supplied the railroad man.

"That's the word," Simpson continued. "Didn't want any o' them. 'Spose he meant he could wrassle them cases himself. Waal, anyways, he drove off up to Black Mountain again. Brought the truck back the next day. Since then no one's seen hide nor hair o' him."

The station agent could repress himself no longer. That his brother gossip should enjoy the retailing of the most thrilling episode in the history of the town was unbearable. He burst out—abandoning his usual slow drawl for a rapidity of utterance which effectually shut Simpson off.

"Nope. Nobody's seen him. Couple of us took a walk up the mountain Sunday after he got here. Land around the falls was posted: 'Private Property. Keep off, this means you.' We didn't pay no 'tention, them signs is usually to scare hoboes. We went right on in. Hadn't gone more'n ten feet when we heard a shot. John swears he felt the bullet part his hair. You kin bet we run. The constable said a man had a right to shoot to keep trespassers off'n his land. But that gink better not come to town when John's around!"

Buck could hardly conceal his excitement. Surely this tale of the mysterious stranger confirmed the tattered map that had brought him to Birdkill. But he dared not give the gossips a hint of his suspicions. If the mysterious stranger were indeed Jim, Ruth was up there with him. Perhaps she was still unharmed. The organization of a posse, a mass attack, might precipitate whatever danger threatened her. He must move carefully.

"Certainly a strange story," he said, as indifferently as he could. "But there may be some reasonable explanation. Maybe the stranger is just some one like me, out for a rest away from people. As long as he doesn't bother you, I'd leave him alone. How's radio reception around here?"

"That's another funny thing. For about three weeks no one around here's been able to get anything but static on his set. Before that we could get New York, Schenectady, an' even distance like Chicago clear as a bell. No one kin make it out."

Another link in the chain of clues! "Well, well, you don't say! That's right in my line. I'll have to look into it while I'm up here. Well, I'm for bed. See you tomorrow!"

Once in his room, Buck threw himself across the bed. At last he was hot on the trail. He must carefully plan his course. This was no ordinary criminal with whom he had to deal. Weird things were happening up there on Black Mountain. A scientific genius perverting his knowledge to evil ends. An unscrupulous monster was wielding a mastery of unknown forces. One misstep, and all would be lost. For himself, Buck was not perturbed. But Ruth, laughing-eyed Ruth, what of her? A groan escaped the anguished man.

This wouldn't do. He must plan calmly, thoroughly. Well, the first thing to do was to find out just what was going on up there. Only way to do that was to go and see. By Jove, he'd start right now! Buck sprang up, then stopped short. Wait a minute. Mustn't go off at half-cock. Suppose he got into trouble up there. Was shot, or captured. Who'd know all that he'd found out? Must get somebody else. Who? None of these yokels. He'd have to get Riley!

"But Riley, in spite of his brains and guts, is a policeman. He'd want to bring up a mess of police, or state troopers. Got to avoid that at all costs." Buck was thinking aloud now.

"But I can't trust any one else. I'll chance it. I think I can make him see reason. Now to get him. Can't phone or telegraph. Don't want these hicks spreading tales all over town. Wait, there's a midnight to New York, and a six o'clock back. That's it. I'll run down and be back in the morning."

FOUR o'clock. The stertorous snores of Detective Sergeant Riley shook the house. Suddenly the shrill alarm of the door-bell cut through his dreams. Instantly he was wide awake. "What the—must be a riot call. Those Reds, I guess." By this time his door was opened. "Buck Saunders, by all that's holy! Got something? Found her? Quick, man!"

"Nothing definite yet, Tim. But plenty's going to happen in the next twenty-four hours or I miss my bet. May I come in?"

"Surest thing you know. Come into the kitchen, if you don't mind. We can talk there without disturbing the family. Just a minute while I tell the missis there's nothing to get excited about. I get these early morning calls once in a while, and the old lady's always thinking I'm being called out to be murdered."

Riley was gone but a moment.

"Now spit it out, young fellow. And it'd better be good to excuse your getting me out of bed at this hour."

"It's good, all right. It's the break at last. Tim, I think I've found the headquarters of the gang we're after! I haven't got an awful lot yet, but something tells me I'm on the right trail at last."

"Come on, come on! I'm busting with curiosity now."

"Wait. Before I tell you anything I want you to promise me that you'll let me run things, or that you will forget everything I tell you."

"I thought you were assisting me. Now you want to be boss. That's what comes of letting a civilian in on police work."

"Listen, Tim, you know me well enough by this time to know that I wouldn't ask this unless there was good reason. Do you promise?"

"All right, all right. I'll promise." Concisely Saunders told him the entire story. Riley listened with growing excitement.

"By Jove, that does sound like the real thing! Your clues are mighty slim, but I've got the same feeling you have. Well, we'll get the troopers and surround that place on the mountain, then go in and find out what's up!"

"No, Tim, that's just what we won't do. If I'm right, Ruth's in there. Any display of force, and Jim will take it out on her. I knew that's what you would want to do; that's why I exacted that promise from you."

"What then?"

"I'm going in there alone. I need your help. If I lose out, somebody else must carry on. This horror must be stopped. But Ruth comes first with me! I want you to come up there alone with me, and then we'll work it out together."

"But the regulations——"

"Blast the regulations. Tim, if you're the man I think you are, you'll forget that you're an officer of the law and do what I ask. I know I'm asking you to risk your job. I'm asking more. I'm asking you to risk your life. What about it? Are you man enough to do it?"

No one with a drop of Irish blood in him could resist that challenge. Riley stretched out his huge paw.

"You win, Buck. I'm with you."

The two shook hands on that.

"Now, listen," Saunders spoke, tensely. "I'm going right back. But we can't do anything till dark, he's evidently on guard. So you leave on the six p. m. Here's the plan as far as I've gone." Saunders went on for a few moments.

"Got that? All right. I've got to go now. See you tonight."

The door closed on his retreating form.

BACK at Birdkill, Buck spent the day familiarizing himself with the scene of the coming expedition. A dirt road, meandering westward from the hamlet, passed among three or four small farms, then plunged into the darkness of a thick wood. Almost immediately it began to climb up the steep slope of Black Mountain. Now paralleling the road, now wandering far afield, a sizable stream ran rapidly on its way to the Hudson and the sea.

Having ventured past the last farm, Buck found that the road gave little sign of recent use. True, there were deep-worn ruts, but these were remnants of the days when there was a busy flour mill at the falls above. He had learned that this enterprise had been abandoned years before. All that remained, he was told, was the dilapidated structure and an almost demolished water-wheel.

Saunders' walk ended when he saw the first of the warning signs the mysterious stranger had posted. Buck had no desire to arouse his quarry's suspicions, to place him on guard. The information he had thus far obtained would be sufficient till night came to veil his movements.

The afternoon of waiting, back in Birdkill, dragged on interminably. Horrible thoughts of the weird figures attacking the countryside, of the anguish Ruth must be undergoing, crawled like maggots through Buck's brain. This idle waiting was unbearable.

At last dark fell. Eight o'clock, and Buck heard the clangor of the arriving train. Thank God that's on time! Let's see, Tim dropped off at North Valley, five minutes back. Cross-country it should take him twenty-five to get here. A quarter of an hour more, then we can get busy.

Fifteen minutes passed by. Buck, waiting impatiently at his open window, heard at last the thump-thump of the heavy-footed detective echoing in the deserted street. A dark figure paused uncertainly below.

"All right, Tim, be right down," Saunders called in a low tone. One last look at his revolver, then Buck was out in the street.

Here in the sleeping street of the little village, Tim's garb, revealed in the dim light of a half moon, was incongruous indeed. From the heavy-soled shoes of the patrolman to the brown derby perched precariously on the back of his head, the detective was redolent of the great city.

In spite of his excitement Saunders grinned broadly.

"Hello, Tim. Glad you're here at last. Let's get out on the road before we wake the hicks!"

The purlieus of the town were soon passed. The two paused.

"Well, what's the lay, Buck?"

"We're going up that mountain. The old mill is about half-way up. Then we'll see what's next."

"Say, what's the matter with the lights? Power-house break down?"

Saunders laughed. "I'm afraid they don't light their roads as well as we do on Fifth Avenue, Tim. No, we'll have to depend on old Luna up there, and our flashlights."

"Well, I suppose what's gotta gotta, but I'd sure like to see a couple of lamp posts. Got your gat?"

"Here it is."

"Throw out those cartridges and take these. I've been working at them all day."

"What on earth have you got there?"

"Silver bullets."

"Silver bullets! What's the idea?"

"Can't kill banshees with lead. That's been our trouble all along. Just remembered today what my grandfather told me. Only thing that's any good is silver bullets."

Saunders smiled covertly. The weird happenings of the past six months were arousing all the old superstitions imbedded deep in his companion's Irish nature. But it would be tactless to mock him.

"All right, if it'll make you feel any better. But let's get going."

The two walked on. Deep silence reigned beneath the trees. Only the far-off shrilling of the crickets broke the silence. It was very dark here in the woods. Barely enough moonlight filtered through the ever-arching trees to show the path. The peace of nature's night gave no hint of the dread not far off.

"Hush, what's that?" A sudden whisper came from Riley.

Ahead there was a faint humming sound, mingled with the rush of waters.

"Sounds like a dynamo," Buck said at last. "Shouldn't wonder. The disturbances of the radio sets around here speak of some electrical operations at the old mill. We'll see."

At long last Saunders spoke again. "We're almost there, Tim. I don't want to go along the road any farther. They're probably watching that. We'll get over to the creek. It's only twenty feet to the right of that dead tree. If we follow the stream it will lead us to the mill. That's safer, I think."

They plunged into the forest. A moment, and the glint of moonlight on the waters showed them the stream.

"Quiet now. Try to make no sound. We're mighty close."

Progress was more difficult now, but at last the overpowering hum told Buck and Tim they were near their goal. The adventurers were crawling now. Miraculously, no sudden crash resulted from Riley's awkward attempts at woodmanship.

Suddenly, they came to a clearing and halted. Clear in the moonlight now they could see the looming structure of the old mill. The great wheel, repaired, was turning rapidly in the stream from which a wooden flume rose up the mountainside where once the waters fell free. The air vibrated with the hum of machinery in rapid revolution. No light came from the building. Far off in the valley a church clock struck twelve.

"What now?" Tim breathed.

"Wait a few minutes, and watch. Perhaps we'll see something."

They waited. No sign of life about the place. Only the eternal turning of the wheel, the roaring of the waters, the hum of machinery.

SUDDENLY Riley gripped Buck's arm.

Tremblingly he pointed to the road, where it emerged from the trees. Movement, figures could be perceived there. The shadowed forms became more distinct. Two men, their automatic movements betraying their kinship to the ghouls of the cemetery at Hopeville. Between them they bore a third. No—it was a body. The trailing arms, the lolling head, spoke unmistakably of lifelessness.

A door in the black wall of the mill opened. A sword of light cut through the darkness, illumined the road, the awesome group. No mistake now. These were indeed the same terrible figures whose apparition had seared the souls of the two who watched from the shadows. The figures entered the door. It shut. Darkness again.

The tender gentleness of the summer night was gone. An ominous horror brooded over the scene. God was shut out from this place!

"No doubt now!" Saunders muttered. "This is what we've been searching for. And Ruth—Ruth is in that devil's den!" A sob burst from him.

"Hush, boy. Don't lose your head now. You've done great work so far. Pull yourself together. Look!"

Again the door had opened. In the yellow light which streamed forth, one, two, three of the dread figures appeared. They stood there uncertainly for a moment. One reeled backward, as if drawn by some irresistible force. The others ran out, swiftly, but still with that queerly mechanical gait. They disappeared among the trees.

Another form appeared in the oblong of light. More human this. He peered out into the night. Then, with a gesture of despair he vanished within. The door shut.

Saunders could scarcely contain himself for excitement. "That's Carruthers, that's Jim Carruthers. Tim, I've got to get in there!"

"Softly, lad, softly. How are you going to do it? There isn't an opening in that place as far as I can see. Only that door, and that's sure to be well guarded. Better let me get the troopers and we'll smash in."

"No, a thousand times no! Can't you get it in your head that Ruth's in there? We can't risk it. I tell you, I'm going in. There must be some way. Perhaps on the other side of the mill. You stay here and wait. I'll prospect around. If I'm not back in an hour, go ahead with your plan. But don't follow me in unless you get help. If these ghouls get the two of us, it'll be all over."

"Well, I've promised. So go ahead. But for God's sake take care of yourself, boy!"

"Now remember. Do nothing for an hour. If I'm not back by then, you're released from your promise."

"Good luck, Buck."

SLOWLY, carefully, silently, Saunders crept to the base of the House of Horrors. Inch by inch he dragged himself along till he had turned the corner. Ah, there was a vertical slit of light! A door? A window? Perhaps only a crack. But at the very least he could peer into this lair of evil.

Even more painstakingly slow were his movements now. Only the faint scrape of his clothing against the side of the mill marked his progress. At last he had inched his way to the beckoning streak of light.

Only a forgotten crack between two planks! Carefully Buck raised himself till he could look within.

A gasp of horror escaped him.

On a long metal slab, hung by chains of insulators from the ceiling, lay the naked body of a dead man. The glassy eyes.

the gray pallor, the limpness of every limb left no doubt that the soul had departed from that form. The breast was still.

Suspended above the slab was a spiral copper coil, beneath, another. From one to the other, through the body, a cylinder of blue flame seemed to flow. It vibrated with a blinding glare. A strong scent of ozone came to the watcher's nostrils. He heard the roaring crackle of the electric arc.

Buck could see little else of the room. Yes. Just within the field of his vision the edge of a large switchboard. A hand, grasping the knob of a rheostat, the pointer slowly moving.

Horrible enough was this scene, but more terrible what followed; for even as Saunders watched, the dead body moved. The fingers of the left hand, hanging flaccid over the edge of the slab, clenched. A leg was drawn up, jerkily. The head turned from side to side. The cylindrical arc grew more intense. Its roar was deafening.

The whole form was now instinct with movement. It shuddered as if in agony. Wave after wave of tremor passed over it. A horrible grin distorted its features. It sat up!

The pointer of the rheostat moved back. The blue flame lessened.

The form swung its legs from the slab. It rose, but stood motionless. The arc was gone, but a beam of green light from the direction of the partly seen switchboard gave it a spectral hue. The green light grew in intensity. The figure walked, with the hideous mechanical movements already so dreadfully familiar. The dead was alive!

But no. The unseeing eyes still stared glassily, unblinkingly. Eyes of a dead man, no returning soul looked forth from them. This was not a being wrested from Nirvana. This was still a dead body, invested with a gruesome semblance of life by some obscene force!

As the full horror of what he witnessed crashed into Buck's consciousness, he felt himself seized from behind. Cold, clammy cold, fingers encircled his throat. Bony legs clamped themselves about his. He was borne backward to the ground. The fingers pressed tighter. He could not breathe. He tore at the dead hands gripping him, strove desperately to free himself. But the Thing attacking him had superhuman strength. Buck labored for breath. Those fingers pressed even tighter. His lungs were bursting, an iron band constricted his forehead, great globes of light appeared and burst in his brain. He knew no more.

Endless intersecting circles of colored light danced through the blackness of space. Whirling, ever whirling, they reeled dizzily about. Two eyes, two great dead eyes stare unblinkingly, one green, one blue. The bed is hard, very hard. His head hurts so! Buck awoke.

A candle sputtered beside him. He was lying on the floor of a cave. A dark, black cave. Water dripped unceasingly from the roof. How did he get here?

He remembered. Shudder after shudder shook his throbbing body. This was a nightmare, all the dread events of the past weeks. Oh why couldn't he awaken?

No, it was real, too real. He was a captive. At the mercy of the fiend incarnate who had loosed the horrors of Hell on the world. And Ruth, he could never save her now!

How his throat hurt, and his head! Could he escape? He was alone, perhaps unobserved. He sat up. Eagerly he looked about. There was the entrance. A great stone blocked it.

Buck rose. He staggered. He was weak, very weak. But his strength was returning rapidly. He made his way, painfully, to the hole which marked the exit from his rocky prison. With all the force he could muster he tried to move the barrier. To no avail. Even were he in full command of his not inconsiderable strength, this would be an impossible task. He slumped to the floor again, bowed his head on his knees, and groaned in his despair. Fatigue swept over him like a flood. He slept.

Again Saunders awoke. Some one was in the cave! He opened his eyes. Jim! Jim Carruthers stood there, gazing down at him, smiling sardonically. A gleaming revolver was held menacingly in his hand.

"Hello, Buck," a mocking tone belied the welcoming words; "glad you've dropped in for a little visit. Haven't seen you for ages."

BUCK sprang to his feet, made as if to leap for Carruthers. An ominous motion of the weapon halted him.

"What have you done with Ruth? You fiend, you devil!" a stream of vituperation came from Saunders' lips. All his pent-up agony, all his despair, all his helplessness, came forth in lurid denunciation. "If you've laid a finger on her I'll tear you limb from limb, and all your devil's tricks won't save you!"

"Why, Buck, your language astonishes me. Surely that's not the way to talk to an old friend. As for Ruth, she's safe. A little uncomfortable, perhaps, but that can't be helped. You're just in time to wish us joy, for she has graciously consented to marry me."

"You lie, you monster! She'd never marry you. Not while I live!"

"Oh, if that's the only obstacle, it will be removed very soon. You don't think I'm letting you go back with all that you've found out. You'd be dead now if I hadn't wanted to talk with you first. I've got a lot of pride in my achievements, and it will tickle me to explain them to some one who can appreciate their greatness. I can tell you my secrets freely—you'll never repeat them. I can use that splendid body of yours too. You've really done me a favor by walking in here. Thanks, old man!

"A little while ago you were trying hard to get out of this cave. Good thing for you, you failed. Come take a look at my pets."

Carruthers turned. In his free hand was an electric torch. Its beam sprang out and illumined the cave's entrance. The stone was gone; the opening gaped, black, menacing. Saunders, still trembling with rage, moved to it, his captor close behind him.

The sound of many people came to his ears. A fetid stench assailed his nostrils. Something dreadful was out there! Suddenly, the beam from Carruthers' flashlight sprang out again. It flashed here and there about the huge cavern the light revealed. Hundreds upon hundreds, nay, thousands of the dead-alive were moving about in the darkness. The natural cavity stretched out beyond his vision, yet so great was that throng that each could move freely for only three paces. Here in the bowels of the earth a veritable sea of dull gray faces, lusterless eyes. When this horde was let loose, what terror would stalk the earth!

"Nice fellows, these creations of mine," Carruthers gloated. "When I've perfected my process, they'll be harmless enough. But now, you've come into contact with one or two of them already. I don't think you relished the experience. What do you think would happen if you should walk out there?"

Saunders turned pale at the thought.

"I had that stone put there to protect you, not to keep you in. Now, you've been very curious about my proceedings. Let's get back in the cave and I'll tell you all about it. Won't do you much good, but I've got to talk to somebody. Ruth doesn't know enough about science to understand the greatness of my achievement. And I have nobody else, but those." A wave of his hand indicated the Things in the outer cavern. "Well, will you listen?"

Buck, striving hard to maintain his equanimity, shrugged his shoulders. "I don't suppose I can help myself."

The two went back into the small cave. The candle sputtered. Black shadows loomed menacingly on wall and roof. From without came the unceasing murmur of the foul creations. Then began the weirdest tale ever told.

"When we were at college together, you fellows called me 'the grind'. While you were booting the skin of a dead hog about, or engaging in other invigorating but useless sports, I busied myself in laboratory or library. You were having a good time, I was preparing for life. Now, while the rest of you are out selling bonds to your friends, I am on the way to control a means of cheap labor that will set the world free from toil. One more problem to solve, only one more, and I shall be ready to announce my accomplishment to the world.

"The most expensive item in industry is the cost of labor, and its unreliability. From the smallest farm to the greatest factory this is true. The greatest geniuses of our times have devoted their ingenuity to the devising of metal machines to replace human labor. In the meantime the best, the most ingenious, the most adaptable of machines has been wastefully discarded—the human body. By the millions, by the tens of millions we cast this perfect machine into the earth to molder and decay, while we spend millions to produce devices not half as efficient." His tone had become didactic. He was a scientist, lecturing to his class.

"This error I set out to rectify. All that was needed was a means to revivify the human body after the vital principle, the so-called soul, had departed. I knew that this very revivification would halt the process of decay.

"Long years of work, of hope aroused, of terrible disappointment. At last I solved the secret. Here is how I did it.[1]

[1] That no attempt to reproduce Carruthers' process may be made, his exposition of it has been expunged from the narrative. Suffice it to say that the misguided genius obtained his startling results by a development of the well-known phenomenon of galvanization combined with an ingenious adaptation of sinusoidal electric currents of extremely high voltage, but minute amperage. Remote control was maintained by the beam projection of short wave vibrations. A detailed description of the process, together with blueprints of the necessary apparatus, have been deposited in the secret archives of the War Department, to be utilized only in a national emergency of the most desperate nature.—THE AUTHORS.

"As I have already mentioned, I have only one more problem to solve. It has been necessary for me to use fresh bodies, in which the processes of decay have not yet commenced. Inexplicably, some remnant of volition seems to linger in the nervous systems. Every now and then one of my subjects rebels, throws off the influence of my control devices and strikes out for himself. The result has been the series of so-called outrages which have aroused the community. Of course I regret these. But incidents such as these are the inevitable accompaniment of scientific progress."

Buck's soul revolted in protest at this callous reference to the horrors which had struck terror into the countryside. "The man is mad!" was his first thought. But no, those were not a madman's eyes. This was merely the cold calculation of the scientist, brushing aside as insignificant everything but matters essential to his work.

"My principal perturbation," Carruthers went on, "over these happenings was that they might lead investigation to this place. But, luckily, thus far my subjects have broken out only when at a distance. Evidently the power of my control beams is weakened by intervening space. Tonight, for the first time, two subjects revolted in my very laboratory, and ran out into the woods.

"When I shall have solved this last problem, I shall publish my results. Then I shall be prepared to rent out to farmers and to industry laborers who will not tire, require no food, demand no wages. Can you realize what a Utopia the world will become when this happens?"

"Utopia—a veritable Hell, you mean!" The amazed listener could no longer contain himself.

"Ah, there speaks the primitive, the worshipper of the human body. I suppose I shall have to contend with a lot of that sort of sentimental drivel. But when the benefits of my great scheme shall be realized, that sort of prating will be forgotten.

"That cavern out there is my warehouse. The old mill is my factory, my raw material comes from the cemeteries of the world. You are witnessing the birth of a new industry."

Saunders was trembling now with rage. The man's coldly callous attitude toward the unspeakable thing he was doing sent his hot blood into a boil. If he could but catch this fiend unawares, get his hands about that throat! He would risk it. But no, that menacing horde out there. Ruth at the mercy of those monsters, called from the grave! Craft might accomplish what force could not.

"Truly a great plan," he said, as calmly as he could, "but of course it takes a little while to get used to the idea. But I can't understand why you brought Ruth here. What have you in mind?"

"This work of mine will take years. I must have a son to carry it on. Long ago I selected Ruth as my fit mate. My brain, her marvelous body—what a combination that will make! She could not understand. She preferred you, a brainless playboy. So I took her, as I take the bodies I need in my work. She still fights me off, still dreams that you will rescue her. When I show her your dead body she will give up that foolish hope, and yield to me. Meantime, she is locked in the old office of the mill, as comfortable as she will let me make her.

"As for you, you have served your purpose now. I needed some partly intelligent individual to tell my story to. Now I shall rid myself of your impudent interference in my plans. In a little while you shall be dead. And I shall have another unit to store in my warehouse yonder."

"You're very pleasant."

"Pleasant or no, that's my last word. Don't fear, your death will be an easy one. I want an absolutely uninjured corpse for a test I have in mind. Don't try to go out. Only I, and their own kind, can pass safely through that cavern. Good-bye."

A mocking gesture of the revolver in his hand, and Carruthers was gone.

"MY GOD! What hope have I now?" Buck was talking aloud in his horror and despair. "That cold scientific machine will carry out his threats. Only a miracle can save me. Perhaps, perhaps God will help me. No one else can."

Encompassed by such dread things as his reeling brain could only partly conceive, Buck reverted to the simple faith of his childhood. He knelt there on the damp rock, covered his eyes with his hands, and sent his soul out into the infinite in prayer.

A sound startled him. He looked up.

Bending over a tank of gas in the corner was one of the dead-alive. That was to be the manner of his demise. Poison gas. The gray hand closed about the valve, the form straightened.

A shriek burst from Saunders. "Father!"

By some strange twirling of the Wheel of Chance it was the body of his own father that was to take the agonized lad's life. What climactic irony had brought this to pass?

"Father!" Again the agonized shriek burst forth. "It's I. Hartley! Your son! Don't! Don't turn on the gas! Father!"

What is this? A gleam as of some dim intelligence lights the lack-luster eyes. The hand drops from the valve. The pale features work convulsively. Two arms go out, as in entreaty. The form drops to the ground. Is still!

By some strange alchemy of nature, the revivified body of Buck's parent had felt the call of its own. Kinship had broken the strength of the weird power which had held this poor corpse in its thrall. The crowning crime had defeated its own ends. The miracle for which Buck had prayed had come to pass! For the present, at least, he was saved.

Trembling, exhausted by the ordeal, Buck lay on the hard rock. He could not mourn the father whose body lay so close; rather he was glad that that body was at last at rest. His thoughts turned again to the dear girl whose agonized cry for help had brought him here.

"How to get through that cavern, through that mob of dreadful Things? How to get to the mill and Ruth? I must think, think fast. Wait a moment. What was that he said? 'Only I, and their own kind, can pass safely through that cavern!' Perhaps, perhaps I can simulate them, fool them. It's a terrible chance, but I must take it."

Saunders went to the mouth of his cave and peered cautiously out. Day must have come. Far off he could see a faint glimmer of daylight. A faint illumination dimly lit the crowd of dead-alive, seething with the noise of many waters. He shuddered.

Back in the cave again, he practised for a moment the flaccid posture, the mechanical walk, of Carruthers' slaves. Then, gathering his courage with tremendous effort, he ventured forth.

Would the subterfuge work? Would "he succeed in working his way to that distant light? Or were these dread Things waiting till retreat was impossible before they leaped on him? The tension was terrific. Hands of iron constricted his heart. Cold beads of moisture stood out on his brow. Why not try a desperate dash? No. Before he could run ten paces these gray forms would be upon him, would overwhelm him, rend him, screaming, into little bits. He forced himself to down that nigh irresistible impulse, to jerk slowly forward in the very gait of the dead-alive.

Years passed, it seemed. Ever nearer grew that patch of light. Ever tenser the shuddering fear of the horrors about him. Once a cold hand brushed his. He stood stock-still. The hair at the base of his neck bristled in ancestral fear. But the form passed on.

At last he reached the threshold of the door from which the light came—passed over it—fell fainting on the floor. He was through!

A MOMENT Buck lay, his senses reeling with unutterable relief. Then he pulled himself together. His task was but half accomplished. He looked about him.

He was evidently in the basement of the old mill, the walls were foundation stones. High up on one side a window gave entrance to the blessed sunshine. At the end was a rickety staircase. From somewhere above came the familiar hum of machinery.

"Locked in the old mill office. That's where he said she was. Well, that's somewhere above. Perhaps near the head of those stairs. Here goes."

Testing each step, Buck silently crept upward—to what new horrors? Scarcely a creak of the old wood gave token of his passage. At last he reached the top, pressed cautiously on the trap-door there. It gave at his touch; thanks be it was not barred. Slowly, slowly, he raised it, listening intently the while. No sound came to alarm him. Now the opening was large enough to admit his head. He peered about.

Directly ahead of him was a door. Old and faded, he could still decipher the letters, "Office." So near was his goal! And the key was in the door! Again he listened. Only the hum of the generators somewhere behind.

Even more cautiously than before he raised the trap a little. He could squeeze through the opening now. At last, he was through. Softly he crept to the office door, reached up, slowly turned that providential key. Slowly, slowly he turned the knob, pushed open the door, slid into the room, closed the opening behind. Then only he dared to breathe, to look about.

The room was dark, the one window boarded. But through a chink in the boarding one only beam of light streamed through the dusty air. Buck's eye followed it. See, the ray rests on a face, a well-remembered face. Ruth lies sleeping there!

Saunders tiptoed lightly to the rude bed on which his sweetheart lay. Gently he pressed his palm against those sweet lips, swiftly bent and kissed her brow. The eyes flew open, stared in fright, then lit up with unutterable gladness.

"Quiet, dear. Not a sound!" Buck whispered, then removed his silencing hand.