RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

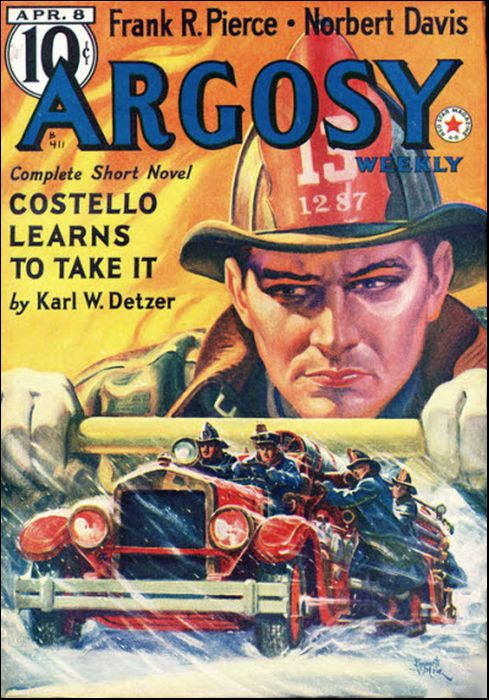

Argosy, 8 April 1939, with "Test for a Tatar"

The steppes were fierce and desolate, and he who would bestride them had to learn the lonely way of the tiger. So, in all the Caucasus were was but one fit to rule the Mongol horde.

SUBOTAI reined in his quivering, white-nosed stallion to survey the gurtai, or closing-in point of the great hunt. The scene sent the wild Mongol blood racing through his veins. As far as the eye could reach, the high flat plateau of the Gobi was alive with plunging, snorting horses, ridden by the fierce Yakka warriors who followed Temujin, eldest born of Yesukai the Valiant. Yesukai, who was Khan of the Great Mongols, master of forty thousand tents, whom his own son had offended.

Within the sweep of a great circle, hemmed in on all sides by the eager huntsmen, leaped and twisted and snarled the trapped animals of the waste spaces. Foxes, deer, cruel tusked boars, great shaggy bears and slinking, snarling tigers weaved in extricable confusion, for once forgetting their native enmities in the face of the common peril—man.

"Ho!" shouted Subotai exultantly as he strung an arrow to his bow, "there will be a sufficiency of meat in the yurts this long winter. But why doesn't Temujin signal?"

He glanced impatiently to the tall, youthful chieftain, sitting easily the saddle of a powerful bay. The wide-set greenish eyes gleamed coldly from a white-yellow mask.

Close to him, mounted on a slighter horse, nervous with vitality of the steppes, was Targoutai, lord of the Taidjuts, hereditary feudal foes of the Yakka Mongols. A saturnine, spare individual, older than either Temujin or Subotai, with deep-set slanting eyes that held more than a hint of cruelty, he had joined this hunt of the Mongols unexpectedly.

The wild cymbals clanged their brazen clamor, frantic wolves howled, and a tawny tiger crouched almost in front of them, tail lashing, and spitting horribly. Then Temujin raised his gloved hand in the long-awaited signal. Instantly the hunters froze. The young chief rode forward alone, short sword in hand, straight for the struggling mass of animals. By the inexorable law of the Gobi it was his right to kill the first of them.

Subotai sucked in his breath. For, disdainful of lesser game, Temujin had slipped from his horse, and, armed only with his naked sword, was calmly approaching the great tawny tiger. The crouching animal tensed, his tail stiffened, he gathered himself for a mighty spring. A sudden hush, half of dread, half of fierce exultation for their fearless chieftain, fell upon the crowding warriors. Only Targoutai smiled, sardonically.

The tiger sprang, a streaking yellow dash in the air. Temujin raised the broad edge of his weapon, sidestepped to avoid the hurtling thunderbolt. His foot caught in a twisted root, and the next instant he was sprawling headlong, directly under the claws of the snarling beast.

A great cry of horror rose from the Mongols as they spurred forward to the rescue. Only Targoutai remained where he was, his face a deadly mask. He slipped an arrow to his bow, and waited.

But Subotai, whose bow was already strung, launched the whistling arrow just as the tiger lifted a huge paw to rend the fallen man. True the shining arrow sped, it caught the beast full in its tusked mouth with such force that the iron tip emerged from the back of the muscled neck. The tiger dropped heavily on Temujin, rolled over, and lay motionless.

AN INSTANT later, another shaft sped through the keen air, imbedded itself in the furred underside of the dead animal, inches away from the prone body of the chieftain.

Startled, Subotai turned, just in time to see the Taidjut, with black rage on his face, slinging his bow swiftly over his shoulder. For a moment Subotai did not understand; then realization leaped on him like a live thing. If his own shot had not dropped the tiger, that second would have gone home in Temujin's body. He spurred for Targoutai.

But a swirl of shouting horsemen, riding madly to the aid of their leader, cut him off, forced him along. A dozen eager hands pulled the tawny carcass away, raised Temujin to his feet. He stood there, bruised and bloody, but otherwise unhurt. There were no signs of fear in his calm proud face or in the cold unhurried voice.

"I am not hurt. It is but a trifle. Yet who was it loosed his keen arrow in such good stead?"

Subotai pressed forward to claim the honor, but he was forestalled. To his incredulous amazement, he heard the slightly sardonic, mock-humble voice of Targoutai. "It was I, oh Temujin, who most unworthily proved the instrument of your salvation."

A dozen voices took up the tale. "Aye, most noble lord, we ourselves saw the swiftness of his arrow."

For the moment Subotai was stunned, speechless at the effrontery of the man. Then he opened his mouth to protest. But Temujin was already speaking, and to interrupt the great Khan's eldest born was death.

"It is well, oh Targoutai. You rode into our ordu an enemy, and claimed our hospitality. It was granted, and you have repaid it. Henceforth we are friends, blood brothers. At the feast tonight you shall sit on my right hand."

The Taidjut bowed. "So be it. Blood brothers we shall be."

Only Subotai caught the subtle emphasis. He tried to thrust forward to expose the traitor. But not for nothing had the elders of his tribe named him admiringly, "The Gray One." He was young, it was true, and valiant, but the sheathed, brooding eyes set in the sun-bronzed face betrayed an unwonted deliberate intelligence within.

He checked himself. No one had seen his arrow; all had witnessed the bow in Targoutai's hands. What more natural than to believe him the savior? Should Subotai now step forth and denounce the Taidjut chieftain, all would think him envious, desirous of glory. The second arrow might prove his undoing, and its message of death for Temujin leader, rebound on his own head. And then—even if he were believed, and Targoutai slain with slow tortures, as by the law he must be, Targoutai's powerful Taidjut clans would catapult upon all their camps seeking vengeance. So he refrained, and held his peace.

Temujin raised his hand again in signal for the final slaughter of the trapped animals. The Yakkas threw their horses into the squirming mass, the blood lust in their twanging bows and dipping swords. Only Subotai held aloof, a thoughtful frown puckering his wide spaced forehead....

THE interior of the black felt yurt was crowded with many men. The air was hazy with the great smoky fire that blazed on the stone hearth. The long, rough-board table groaned under steaming carcasses of deer, roasted whole, grinning boars' heads, and savory shanks of mutton. Above all, in great profusion were the massive bowls of kumiss, mare's milk fermented and well beaten in leather bags, specially treated until it grew doubly strong.

At the head of the board sat Temujin, flushed of face, his proud calm broken by numerous draughts of the grayish white curdled drink. On his right hand was Targoutai, flushed and boisterous, loudly protesting his friendship for the Yakka, raising the bowl to his thin lips, and urging it tipsily on his "blood brother," Temujin.

The sheepskin-clad, leather-jacketed warriors were all far gone in drink, the kumiss passed from hand to hand with increasing rapidity. Already the hands that plunged greedily into the smoking flesh were fumbling as they helplessly tried to convey the torn chunks to their mouths.

Except Subotai the Gray One. Seated a little down the table on the side of Targoutai, his eyes, half closed in seeming listlessness, were alert to every little move. Not for an instant did they quit the drunken figures at the head. So that he was the only one who detected, or thought to, the crafty glance of the Taidjut chieftain, his disguised sippings at the bowl while he seeming to quaff deeply, the solicitude with which he forced more and more upon the Yakka chieftain.

Targoutai was not drunk. He was playing a part—a subtle, crafty one. Why? The Gray One slouched a little further back on the bene a, and waited to see the purpose that lay crouched like a tiger behind the cover of Targoutai's feigning.

It was not long in coming. By now the warrior nomads were glassy-eyed from their potations. The empty boasts grew louder and more vainglorious. Soon the bragging would give way to bitter quarrels. Targoutai's small cruel eyes darted around the smoking yurt, seemed satisfied with what they saw.

"Oh, Temujin," he hiccoughed boisterously on the eldest born's shoulder, "we are friends, blood brothers, are we not?"

The other swayed unsteadily. "Aye, that we are, and the man who dare say otherwise shall taste the bite of my sword." He clapped a trembling hand to his weapon. Subotai felt growing puzzlement. He had followed Temujin for many moons, yet never before had he seen him so manifestly drunk. The hard-headed young Mongol had sent many an older man under the table, and risen himself, ready for a wild ride across the steppes.

But the Taidjut's face held only ill-concealed triumph. "These Yakka clansmen of yours," he insisted with a large careless wave, "are friends, are they not?"

"Friends?" echoed Temujin with drunken merriment. "Why, they would follow me to the death!"

The thickened utterance pierced the loyalties of the kumiss-stupefied nomads. They seized their lacquered shields, sprang to their feet, and clashed their weapons as they clamored, "To the death, to the death, for the son of Yesukai the Valiant!" Subotai slumped still further on the bench, the very picture of one besotted. But his mind was restless, probing. Yesukai, the dread Chief, was fifty miles away, taking his ease in the tented ordu, surrounded by his wives. All the warriors had gone on this hunt; the debauch in the surrounding yurts would last far into the night. This seeming aimless talk of the Taidjut. was leading purposely to something. What?

Targoutai sprang to his feet as one suddenly inspired. "Aye, hat is it—to the death! You, men of the Yakka Mongols, let us swear an oath together—a great, binding oath. We are all friends, and we are true to the noble Temujin. Swear that we shall follow him in all things till death do us part. In all things, do you hear?"

FOR a moment Subotai could have sworn he saw a keen, cold, calculating look in the young lord's eyes, but if so, it was quickly sheathed. Temujin heaved himself to his feet, and cried. "My blood brother, Targoutai, has spoken. I find it good. Who will take the oath with him?" He swayed as he stood, his lower lip hung pendulous, yet his eyes flashed terribly.

The nomads, flushed with the fumes of the powerful kumiss, caught the mad contagion. "We will, we will," they shouted, and made a huge noise with pounding swords. "Till death do rive us we shall follow you, oh Temujin."

"In all things," cried Targoutai above the clamor.

"In all things," they echoed. And by many a strange and sacred oath they bound themselves.

Then the carousers sank back in their places, and gorged on the half-raw flesh, and drank the deeper. But the Gray One's eyes never quitted the two at the head of the table.

Targoutai was leaning forward, his thin lips at the ear of the young chieftain. He was whispering, insidiously, urgently.

Gone was all pretense of drunkenness. The dark face had resumed its cold mask; there was an eager devil glint in the deep-set eyes. Subotai strained to hear, but only a faint murmur came to him.

Temujin hearkened, and as he heard, it seemed to the careful watcher that the stupid look of intoxication dropped from the yellowed features, that the sea-green eyes were weighing, pondering in their close-kept counsel.

A moment Subotai caught a glimpse of unfathomable things, of flaming desire, then the lids drooped heavily to shield from prying eyes.

The tempter whispered on. But still there was no response. A look of despair, of thwarted rage, darted across Targoutai's face, but he urged on doggedly. At last, staring at the impenetrable mask before him, he sank back, exhausted with his futile efforts.

Then, and then only, did Temujin turn to him. "It shall be done as you say."

Subotai was tense with the strain of trying to piece together what was going on. The tones were irrevocable. A momentous decision had been made, the Gray One knew.

Targoutai's eyes gleamed with sudden satisfaction. He sprang to his feet, as though afraid lest Temujin should change his mind.

"Ho, men of the Yakka Mongols! We have all sworn a great oath tonight. Now it shall be put to the test. Temujin commands it!"

The young chief favored him with an oblique glance, and quietly rose. A sudden hush fell in the smoke-filled yurt, hands paused halfway to sodden mouths, the bowls remained suspended in midair. Subotai leaned forward.

Now the mystery would be explained. That it would be of ill omen, he was certain.

But he was to be disappointed. Temujin spoke, as always, in terse cryptic phrases. "Friends, comrades who have taken the blood oath, mount your horses and follow me."

The sodden nomads stared uncomprehendingly. There was no sign of movement.

The haughty face of Temujin took on a deeper tinge. When next he spoke, his voice was smooth with deadly menace.

"Have you not heard, oh swearers of the oath?"

The hearers stirred uneasily, and staggered to their feet. For a blood oath was not to be taken lightly; it was a very sacred thing to these wild children of the steppes. All other ties, of family, of loyalty even, were as mere threads to the iron bonds of this.

WITHOUT waiting further, Temujin strode from the yurt, and Targoutai after him. The great black tent spewed forth its disordered horde. The fleet horses of the Gobi were tethered nearby, under the watchful eyes of striplings.

Temujin sprang lightly to the back of his bay, and sat, a motionless statue in the bright cold moonlight. There was a confusion of bucking, plunging horses and shouting, swearing men, but soon all were mounted. Once in their saddles, even the most drunken held his seat easily, such was their superb horsemanship. Subotai soothed his white-nosed stallion with a practiced hand, and one bound swung him into the saddle.

"Let each man take with him a second mount," clear and cold came the next command.

In silence he was obeyed. Among the tribes it was customary always in raids, on the warpath, or on long hard marches, to gallop with an extra horse, whose reins were fastened to the saddle pommel. So that if the ridden horse should founder, or become winded, there was a fresh mount at hand to change to.

"Ride!" Temujin swerved about, and was off with a thunder of flying hoofs. The Taidjut was riding like the wind, almost abreast. The band of fifty Yakkas swung in behind, and the hard steely ground rang with the wild gallop. The great Gobi was mysterious in the white frosty light. Great blue shadows raced with giant strides across the interminable plain; the brittle winter stalks crunched beneath the spurning hoofs.

Subotai raced along, his two horses breasting the keen air in their stride. What devil's plan had the treacherous Taidjut cunningly instilled in Temujin's mind? Surely nothing that would end well. Yet the young chieftain was no fool, and he had readily assented.

This wild journey of theirs in the dead of night—it had all the earmarks of a raid. But on whom? The nearest ordu, some twenty miles away, was their own; the next was the abiding place of Yesukai. the Great Khan. AH about were their own tribesmen; the nearest enemy was over a hundred miles away, and they were the Taidjuts. Surely Targoutai was not leading an attack on his own people.

The Gray One spurred his horses to the utmost, and soon he drew alongside the leaders. Targoutai turned a threatening glance.

"Who are you that dares intrude upon his lord?" he demanded abruptly.

"I am Subotai, of the Yakka Mongols, who never yet took the dust of a Taidjut, except when pursuing," the Gray One retorted hotly. The saturnine mask twisted into hideous rage at the deadly insult. His hand moved swiftly to the quiver. Subotai watched him like a hawk, fingers resting lightly on the pommel of his sword, ready to swerve his horses directly for his enemy.

Temujin seemed not to have heard the angry colloquy, nor seen the threatening gestures, yet, with face ever fronting the pathless night, his low crisp voice came floating back to them.

"Cease your brawling. The first to lift a weapon dies." There was a strange note of finality, of inevitability, to everything the eldest born said and did. A great commander and leader of men was in the making. Without a word the two parted, yet not without a look of deadly venom from Targoutai.

On they galloped in silence, the wind streaming through their hair. Subotai noted that they were approaching their own ordu. Already in the distance could be seen the dim dome shapes that were the black wattled yurts where slept the numerous wives and children of the nomad company. A little jest, perhaps, to come swooping on the silent tent village, and frighten the sleeping wives: out of their wits?

He smiled grimly. No wife of his, nor child, would be disturbed by the drunken clamor. Though importuned enough by clansmen with marriageable daughters, he had not taken to himself the customary wives. A trip to far Cathay was in his dreams before wedlock would claim him.

Immersed in his thoughts, he had fallen a little behind when the lance of Temujin rose in the air, the signal to halt. The band froze in its tracks with the facility of born horsemen.

Subotai was in the rear, screened from the vision of the leaders. Hardly knowing what he did, and never after able to explain just why he did it, he shifted silently from the Thunderer, the beautiful white-nosed stallion, to his second mount. In all the world there was no horse so fleet, so sinewed, so responsive to the merest touch, as the Thunderer. As some men treasure women, as others hoard their gold and precious jewels, so did Subotai regard the stallion.

The Yakkas grouped before the leader, dark centaurs etched before the moonlight.

Temujin spoke, short hard words.

"You have sworn the blood oath—to follow me in all things. Now I shall test you. Let each man change to his led horse, and slay, even as I do, the horse he rode."

SO SAYING, he vaulted easily from his mount into the saddle of the other animal, cast loose the reins. With one swift motion he strung an arrow to his bow, and sped the whizzing shaft. It pierced the gallant bay, that all men knew to be his favorite charger. The wounded animal whinnied piteously, and fell.

A sudden sigh went up from the stricken ranks. As if by magic, the fumes of the fermented kumiss cleared from sodden brains. The shock of what they had just seen sobered every mother's son of them.

For be it known that a good horse was the dearest possession of these Mongols of the steppes; to slay one was the veriest sacrilege. And always they rode their favorites on the first march.

Truly clever was Temujin, or rather, Targoutai the Outlander. First by a great oath he bound them, and now they must do as he did.

Even as they hesitated, the Taidjut shouted on them all to watch him as he kept the oath. Swiftly he changed horses, drew his long bow, and shot the animal.

Still there was hesitation.

Temujin rode at the nearest man. As he spurred close, the short broadsword flashed in his hands, and the next instant the head of the luckless Mongol was rolling on the frozen steppe.

That convinced the doubters that the blood oath was inviolable. With great scramblings and heavings they made haste to change before the dread sword could fall again; and the frosty night air resounded with the twang of many arrows, and the piteous neighings of dying steeds.

The Gray One grunted softly as he shifted back to the Thunderer, and loosed unhurriedly the shaft that sucked the lifeblood of his second mount.

Targoutai's keen eyes fixed themselves on Subotai.

"Holla!" he clamored, "you have bemocked your oath. Look, oh Temujin, he has not slain his Thunderer, his favorite steed, as you commanded, but a mere worthless bag of bones. The penalty is death."

The chieftain's glance was terrible as it bent upon the culprit.

"Nay, Lord Temujin, I did but follow your very example, even as I had sworn," the Gray One answered softly. "I shifted to the horse I led when your command was given, and slew the one I rode. Through some mischance it seems I was not mounted on the Thunderer then."

"The merest chicanery!" The Taidjut was beside himself with rage.

There was a glint of something like approval in the stern eyes of the eldest born as he gazed upon the unbowed Gray One.

"Peace," he said slowly to the frothing Taidjut, "he did but follow me in every detail. Ride!"

Away galloped the cavalcade, each man deep in his sorrow, and fearful whither this wild adventure was taking him. They thundered down upon their native ordu, amid a clamor of barking, yelping dogs. From every black felt yurt rushed scantily clad, disheveled women and wailing, frightened children. Sleep was heavy on their eyelids as they roused to this sudden invasion.

The screams of fright gave way to soft welcoming cries as the wives recognized their masters back so soon from the great hunt. The men were already slipping from their horses, eager for the arms of their loved ones, when the sharp tones of their leader brought every one back to his saddle.

"Back, every one of you. Let no man stir until I give the word. There is a second test. On the blood oath you swore."

A shiver of dread went through the Mongols.

"Where is Bourtai, my favorite wife?" rang out Temujin's voice.

"Here, beloved lord," came a soft reply, as a young maiden, not over sixteen summers, beautiful as the dawn, lithe and supple as a gazelle, attempted to throw her rounded arms about him.

He stared at her strangely a while, bent suddenly to kiss her lightly on the forehead, then swerved a little distance away.

"Now, men of the Yakka Mongols," he said, his voice as even and steady as ever, "remember the blood oath. Follow me in every thing even as I am about to do."

The men watched in sickening anticipation. Carefully, slowly, Temujin fitted a keen arrow to the string, took steady aim, and shot.

The whizzing shaft sped surely to its mark. Slowly, very slowly, Bourtai sank to the ground, the yet quivering arrow deep imbedded in her rounded breast. A little moan, and she lay very still.

A GREAT cry of horror broke from the onlookers. Bourtai, fairest and most beautiful of maids, passionately beloved of Temujin, slain, and by his own hand, with cold deliberation! It was incredible.

Instantly there was a wailing from the women of the ordu. With wild gestures and streaming hair they lamented the evil fate of the young girl. The men drew apart, with stern shaded eyes and low muttering.

Temujin sat grimly on his horse a moment, staring at the pitiful body, then he roused himself. Once more he spoke to his men, without emphasis.

"You have seen what I have done. Do you each likewise, in accordance with your oath, slay the favorite wife of your bosom."

An angry growl was his only answer. Darkly desperate the men sat their horses, hands suggestively close to their swords. Was there a leader among them who could make them forget their oath, their very loyalty? Then indeed would Temujin have fallen, trampled in their wrath.

The women of the ordu did not wait on hearing the cruel command. They raised piteous cries and tore their hair, pleading for life with anguished voices.

Temujin's face was inscrutable. As though he heard them not, nor heeded the threatening gestures of his followers, he spoke again, this time with the cold menace of a panther ready for the spring.

"The blood oath has not yet been fulfilled. My patience is short."

Still was there hesitation and black looks. Wrath and fear struggled for mastery.

One, hardier than the rest, burst from the huddled ranks.

"Foul tyrant, think you I'll slay my dear one at your behest, oath or no oath? You shall be the first to fall."

With that he spurred for his leader, bright sword flashing in the moonlight. Swift as he was, Temujin was swifter. No one had seen him pluck an arrow from his quiver, nor draw the bow to its full extent, yet in the instant the rash Mongol halted in his headlong rush, threw wide his hands, and slid heavily from his horse, an arrow in his heart.

When the amazed men looked again, Temujin's bow was once more strung, the iron tipped shaft taut for another victim.

"Who next would disobey his oath?" Cold and unhurried was the voice.

The Yakkas reflected. A blood oath was a sacred thing, and must be heeded, even to this bitter end.

Under the inscrutable gaze of their chieftain, under the cruel sardonic leer of Targoutai, they went heavily about their dreadful tasks. The mysterious night resounded with unavailing prayers and sudden screams.

Only Subotai held aloof, heartsick. The Taidjut saw him standing with averted eyes, and flaring ha red leaped within him. His voice rose strident.

"See, oh Temujin," he cried, "once more this Subotai scorns your dread command, and his oath."

The Gray One turned to his leader. "Nay, you know I am your loyal follower, in spite of the foul mouth of this outlander. Where is my favorite wife, or any wife, for me to slay?"

Temujin nodded. "It is true, Targoutai, he has not married."

The other was beside himself with fury at seeing the hated one escape so easily.

"It is not right that he should evade his oath a second time. Let him then slay his female next of kin."

Subotai spoke softly, yet with an acid edge. "I have not seen Targoutai plunge his sword into his wife."

Taken aback, the Taidjut stammered. "B-but, she is not here."

"Then let us ride quickly to her, and myself shall go with you, to see you do the deed. And since you have complaints against me, why I shall do much to satisfy you. Betroth me this night to your youngest daughter, and you shall see whether I hold back my weapon in fulfillment of the oath."

Temujin nodded grimly. "Well and wisely spoken. How say you, Targoutai?" Targoutai paled beneath the dark yellow of his skin, and muttered unintelligibly. The chieftain smiled a thin-lipped smile, then dismissed it as a jest. There was much to be done this night.

"Ride!" The call rang out, and once more the little troop swept over the vast plateau with a fury of pounding hooves. The tented village became a black smudge in the rear, a stricken thing that hugged to its shattered bosom the poor maimed dead.

STEEL-HARD were the hearts of the riders; a lump that dragged them down within. Bitterly they regretted the oath they had taken in drunken carousal. What next would the terrible Temujin demand of them? Yet, what did it matter now! They had slain their treasured horse and treasured wife. The Mongols had no greater possessions.

Oh truly clever was Temujin—or Targoutai! Thus thought the Gray One, as his foam-flecked Thunderer carried him along. Clear in his mind he saw the plan—and admiration leaped in his pulses at the simplicity of the scheme. Temujin would gain—yet what did the haughty Taidjut hope to win? That part was clouded yet. He must watch carefully.

The broad Gobi was a thing of sinister shadows and ghostly clamors. The Yakka Mongols were afraid, and rode in a solid phalanx for comfort. The demons that rose from Lake Baikul were known to plucky unlucky stragglers from the saddle in the dark of the night.

Twice they shifted from horse to horse, and still they rose. The dawn was leaping in little flames over the reed-bordered, demon-haunted Lake Baikul when they came in sight of the many domed ordu of Yesukai the Valiant, Great Khan of the Mongols, father of Temujin. The Kerulon gleamed silvery beyond.

Without slackening, they lashed their weary horses in a last furious burst of speed. Right before the richly ornamented kibitka, or tent cart of Yesukai, the band came to a slithering halt.

Already there was a stir in the yurts, as men waked at the unwonted noise. A movement was heard within the kibitka, as of some one seizing weapons. No fool was Yesukai!

Loud rose the clear voice of the young chieftain.

"Come out, oh my father Yesukai—it is Temujin, your eldest born, come to bow before your just wrath, and expiate his shortcomings."

The felt flap, bright with threaded gold, was thrown back. A huge form filled the gap; Yesukai the Great Khan. As he saw the clustered band, suspicion gleamed in the bold black eyes, the swarthy bearded face clouded with anger. His right hand gripped a naked sword.

Temujin was some twenty paces away from his fierce sire, the Yakka riders in a mass behind him. Targoutai, craftily smiling, rested his horse, a little to one side, somewhat hidden by a neighboring yurt. Subotai recked not the scene in front of him. All his eyes were fastened on the Taidjut, no little move escaped him.

He saw the tall outlander loose his bow, and slip it stealthily into his hand. A great light burst upon the Gray One—now he knew what Targoutai had schemed. With a soft little chuckle he too dropped the bow off his shoulder into the crook of his arm, swung the quiver of arrows around for easy handling, and waited.

The aroused Khan took a step forward. When he spoke, it was in passion.

"You dare to mock me with subtle words, ungrateful whelp whom I disown? You shall pay for your temerity." He called. "Ho, men of the Yakkas, seize this—"

He spoke no more. For Temujin, with the swiftness of a gazelle in flight, had sped his whizzing arrow, and caught him broad in the chest.

"Comrades of the blood oath, follow me in this as you have sworn."

Half a hundred arrows sped on their appointed paths, for the reckless tribesmen were as dead men, and the Great Khan lived. Stuck all over like a porcupine, Yesukai the Valiant staggered and died.

But Subotai had eyes for none of this. He was watching the Taidjut like a hawk. Targoutai, deeming himself unobserved, aflame with the fires of glutted hate, drew bow to ear, to loose the deadly shaft—at Temujin.

SWIFT as he was. there was one swifter.

Like lightning sped the iron-tipped arrow from the distended bow of Subotai. It clove the air with the swiftness of a gazelle in flight, and caught the treacherous one full between the eyes. The bow dropped useless from his hand and he pitched forward to the ground, a thing of dust and corruption. Still chuckling softly, the Gray-One shouldered his bow once more.

Temujin was speaking, a new note of power in his voice.

"Hear me, ye men of the Yakka Mongols. Yesukai, your Khan, is dead, slain for his many tyrannies. I, his eldest born, am Khan." He paused. "Hereafter shall ye term me Genghis Khan, and I shall lead ye to many victories to the ends of the earth. Let all do obeisance to me, or die!"

By now the black tents had disgorged their load of frightened tribesmen. The oath-bound band, arrows strung, struck terror into the boldest.

A quavering voice, another and another, until all shouted as one. "Long live Genghis Khan, our new Overlord! We are your clansmen!" And swiftly they did obeisance.

Genghis, with inscrutable face, turned. "Now, oh Targoutai, prepare to accept thy reward for thy cunning scheme."

But Targoutai's ears were stuffed, and could not hear. Instead, Subotai rode forward. "He cannot heed your summons, for I have slain him," he said boldly.

The Great Khan's brows were black with thunder. "Who gave you the power of life and death over my followers?"

"It was to save my lord's life," he answered. "From the first I knew this Taidjut chief meant you no good. I it was who saved you from the tiger at the gurtai, when he would have slain you; yet he stepped forth to claim the credit. I did not speak then, for I wished to pierce his subtle schemings.

"Even now, as you loosed your arrow at Yesukai, he aimed at you. I slew him just in time. He thought at one fell blow to rid him of two powerful enemies, then to escape to his own tribe, who no doubt have been forewarned, and are hovering near at hand.

"With our Yakkas in confusion, it were an easy task for the horde to strike and break our overlordship forever."

The brow of Genghis Khan cleared, then he laughed a great laugh.

"Not for naught have they called you the Gray One, oh Subotai."

Then he grew stern again. "I knew him all along for a traitor. I heeded the cunning scheme he whispered to me, for it fell in with mine own plans. I thought to slay him with the slow death at the end.

"But I did not foresee the final stroke he plotted, and in this, you have been wiser than I."

Thus became Genghis Khan, long years the Scourge of God, the Master of Thrones and Crowns. And the greatest of his generals, the most trusted of his counselors, was Subotai, the Gray One.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.