RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

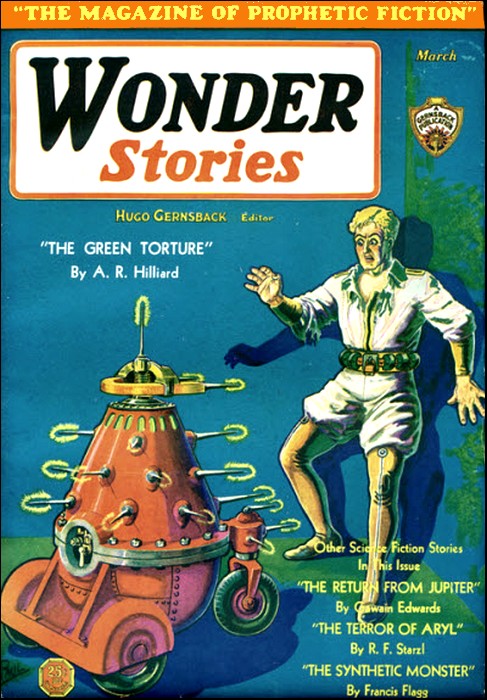

Wonder Stories, March 1931, with "Back To 20,000 A.D."

TO those readers who read "In 20,000 A.D." the present sequel must be very welcome for it not only carries on the great adventures of that fateful time of the distant future but also introduces newer and more amazing experiences.

When we look back over the history of the human race, say for the past 18,000 years, and then project it ahead for 18,000 years more we can get a good index of the unbelievable changes that will occur to us before the year 20,000.

We know that the tendency is for the race to become more and more intellectual and less emotional; and for it to consciously rather than unconsciously evolve, as we control our environment more and more. Arthur Brisbane once said that the man of the future will be a cold calculating chess player who will be almost all brain and little body; and he will have to be carried around on air cushions to avoid even the most delicate of shocks to his nervous system. Our authors go several steps further than Mr. Brisbane in their prophecies and give us pictures of a future world that are almost unmatched for their imaginativeness!

"REMEMBER Tom Jenkins and the story of the Vanishing Wood?"[1]

[1] "In 20,000 A.D." September 1930 WONDER STORIES.

"Will I ever forget it? Say, I still dream about the Jed. That naked, gigantic brain, encased in its quartz ball, floating high in the air and ruling a world by the sheer power of its superhuman intelligence!"

We were in Sid's laboratory. A place that always fascinated me with its queerly twisted shapes of glass, its gleaming coils of wire, its softly purring motors. I don't know anything about those things—I'm just a reporter hammering out murders, and investigations, and stick-ups at so much per column inch.

Often enough, in the years we have palled together, Sid has tried to drum into my head something of the matters that absorb his life but he always has thrown up his hands in despair. Over at the University, where they call him Professor Chapin, my chum is considered a brilliant teacher, and his students in physical chemistry idolize him—but he hasn't been able to teach me a thing.

A 'phone call from him had routed me out that morning. He was very mysterious about it, just said that I must get up to his place at once, he had something important to show me. He had hung up on my impatient questions, so there was nothing left for me to do but get into my clothes and chase uptown.

"Yes," I continued, "I remember Tom Jenkins very well. But did you drag me up here at this unearthly hour to ask me that?"

Sid grinned. "It's past eleven. To anyone but a night-owl reporter this is the middle of the day. But I won't hold you in suspense any longer. I've got a letter from Jenkins. Here it is." He tossed me a grimy sheet of rough gray paper. The pencilled scrawl bulked large across it, childish, unformed, just the sort of hand one would expect Tom Jenkins to write—if he could write at all.

"Deer Perfesser," the letter began, "i take my pen in hand to rite you about something I got to tell you. I hop this finds you in good health and mister Dunn the same. Ma has had a touch of the rumatics this fall and the gray mare has the founders but others wys we are all o.k.

"i am in grate trubble and i dont no wat to do. charlee is heer not charlee jons the blaksmith but charlee from the cuntry wat i told you about and wat mister Dunn wrote the piece about, i got him hid but i dont no wat to do with him. wil you come out heer and advis me wat to do.

"i hop this find you in as good helth as it leeves me and reman your frend Thomas Jenkins."

I gave vent to a long whistle as I finished the unpolished screed. "Charlie—here!" I exclaimed, "what does the man mean?"

"I should imagine just what he says." Sid was bending over a metal tank of some kind, doing something to what ever was immersed in the greasy fluid it contained.

"But—but it's incredible. Why, Charlie won't be born for 18000 years yet. Besides, he was killed by the Jed during the rebellion." That was jumbled enough, but what would you say if you were talking about someone from thousands of years in the future?

"No less incredible than Jenkins' story. And you believed that. After all, Tom came back from 20,000 A.D.—what's to prevent Charlie from travelling in time in the same manner? Remember, the farmer lad didn't see him die. We just assumed that he had."

That was just like my chum. You couldn't feaze him. But my poor brain was spinning like a top. One thing I knew, however. Hell and high water wouldn't prevent me from going out to Blaymont and finding out what it was all about. "When do we start?"

"Just as soon as I finish this test I'm running."

"How long will that be?"

Sid glanced at his wrist watch. "About forty-seven minutes." About forty-seven minutes. You can't beat those scientists!

"What's the matter with finishing it when you get back?"

"Pipe down, young fella me lad. If I stop now it'll take me just three weeks to get back to the point I've reached. Jenkins and Charlie, and the Vanishing Wood will just have to wait three quarters of an hour longer."

Sid was wiser than he knew. Had he stopped the test then, it would have been far longer than three weeks before he could write finis to that experiment.

THE sleepy Long Island town hadn't changed an iota since, six months before, we had walked up the road to the little farmhouse. That had been in the early spring of '32. Now it was fall and, while the day had been warm, the sharp morning chill made me wish I had worn a coat. Sid didn't seem to mind it, as he strode along, though he weighs a hundred and forty pounds to my two hundred and ten.

Tom himself opened the door, and his honest face lit up when he saw us. I thought his great paw would crack the bones in my hand when he grasped it. "Gosh, I'm glad you've come," he burst out, "I'm near looney with worriment."

"What's it all about, Tom? Is it straight what you wrote me?" Sid drove right to the point.

Jenkins' grin of greeting gave way to a worried, almost furtive look. "Straight, as God is my witness. Charlie's here. I got him hid out in the Vanishing Wood." He glanced back over his shoulder. "But say, I don't want maw to hear. I'll take you to him, and tell you about it on the way."

THE strong reek of kerosene came to my nostrils as Tom fumbled with a lantern. Then we were walking across the fields, the bobbing circle of light making the darkness a solid black wall pressing close about us.

"You see, it was like this," Toni began. "I been down to the store for some 'east for ma, and takes the short cut that goes along the edge of the Vanishing Wood. I ain't afraid of goin' near it any more. I know I'm safe so long 's I don't set foot inside it. I was hoppin' right along, 'cause I wanted to get home before dark when sudden like I heard somethin' moving right inside the Wood. 'That's queer,' says I to myself, 'there ain't no creatures ever goes in there.' I stopped, and peered in where I heard the noises. They'd stopped, too, an' I couldn't see nothin'. I was just about going' on when I heard a voice, callin' kind of low. 'Tom,' it says, 'Tom, come here.'

"Well, you coulda knocked me over with a feather. For I knew that voice! I started shakin' all over. 'It can't be,' I thinks, tryin' to hold myself from shakin'. 'He's dead. The Jed melted him.'

"But the voice comes again. 'Tom, help me!' And now I was sure it was Charlie's voice, Charlie that I'd seen last in the City of Mothers just before Karet led the crowd of Robots to fight the Jed. I don't take no stock in ghosts or such, but after what happened to me the last time, I ain't takin' no chances. So I hollered, 'Come out here in the light and let me see who you are.'

"The rustlin' came again, and then I seen somethin' big movin' behind the trees and brush. Then who should step out but old Charlie hisself!

"He just showed hisself for a minute, 'n jumped back. But he looks so scared, and so yearnin' like I forgot to be scared myself and I go right in after him. Sure enough, there he is, the old Charlie. He's all scratched and tore by the brambles, and he's thin and worn looking, but there ain't no mistake about who it is.

"He grabs me round with all four of his arms, and he hangs onto me like a big baby what's lost. 'Tom, Tom,' he says, almost cryin', 'how glad I am I found you.'

We came to a tumble-down stone fence, and scrambled over it while Tom held the lantern high. Not far ahead, a blacker bulk in the darkness showed the wood for which we were aiming. Jenkins took up the story again.

"After I got him calmed down a bit I find out what's happened. It seems he and three or four other of the mistakes[2] had kind o' guessed what was going to happen when the Jed started talkin'. So they wriggled out of the crowd quick just like I did and beat it into the Vanishing Wood. Seems like the power of the Jed somehow couldn't get in there. And the Masters dassent go in after 'em 'cause it's forbidden for thousands and thousands of years. Charlie and his friends were scared to death too, but they all thought there couldn't nothing worse happen to 'em in there than what they seen happen to Karet and the Robots.

[2] The "mistakes" were those of the slave class in the world of 20.000 A.D. who had been accidentally endowed with intelligence during the manipulation of their eggs before birth.

"One o' the bunch had a box o' the little white pills they use for food, and there's a spring in the wood. So there ain't no danger o' their starving right away. But they don't dare poke their noses out, and what they've got won't last very long, so they're worryin' consid'rable. They all kind o' look up to Charlie and make him the boss, and he feels it's up to him to find some way o' gettin' out o' the mess.

"He remembers me, and what I had told him of how I come to his time. So, one day he gets up his courage and jumps into the queer twisted place I told you's in the middle o' the Wood.

"WHEN the twistin' an' the turnin' is over he finds hisself on the ground. Just like me, he thought nothing'd happened, but he calls to the rest o' his gang and they don't answer. Then he goes to the edge of the wood and sees the cows and mares in old Man Brown's meadow. That gives him a terrible scare, he's never seen nothin' like' em before. I disremember've told you there ain't no animals left in 20,000 A.D."

We shook our heads. He hadn't told us that. Tom continued:

"So he dassn't come out. 'Bout 'n hour later he heard somethin' coming along, and when he looks out, who should it be but me.

We had reached the edge of the copse. Round us in the lush meadow I could hear the countless small scutterings and pipings of the country night. But there, among the tall trunks of the age-old trees, was silence, dead silence. Not even the sound of a vagrant breeze whispering in the foliage. Tom had halted, and I drew nearer to my companions for comfort. The lantern light made a ring of safety about us.

"Well, sirs, I knowed that I couldn't bring him out and show him around. Just think what would've happened if the folks round here saw a black man twelve foot high, with four arms, four eyes, and big flaps where his ears ought to be. They'd uv shot him, or gone looney, or something. I tell you, I was stumped.

"But after a while I thought of you. You'd know what to do. So I told Charlie to be calm and patient, and I'd bring some wise men out to see him. Meantime I brought him out bedclothes and somethin' to eat. It was funny to see him at his victuals. He ain't never had nothin' but them white pills, and he ain't got no teeth. So I had to cut up everything very small for him like they do for a baby. He couldn't understand why he had to eat such a lot, and I had an awful time explainin' to him.

"He's just a little ways in here. Let's go in now."

We plunged into the thicket. The interlacing foliage overhead blotted out the quiet stars. We seemed to have passed from reality, to be moving, dreamlike, in a timeless, spaceless land. Sid muttered something under his breath, I could not quite catch it.

The waving lantern light picked out a bulk, a huge form, lying motionless on the ground. The sense of unreality deepened.

The actuality of this visitor from a hundred and eighty centuries in the future transcended my wildest imaginings. Jenkins' description had been accurate enough, but somehow, the conception had not quite struck home. Writing of him, I had persisted in visualizing something akin to the individuals I knew. A freak, but nothing quite as far beyond experience, as different, as this. Yet there was something oddly human about him.

The blackness of him struck me first—a dull blackness that swallowed light. And his size! Twelve feet runs glibly from our tongues, but try to conceive a man twelve feet tall. A six-footer is well above the ordinary run, seven makes a giant. But twelve feet!

Details became clearer in the dancing glow. An extra pair of arms sprawled out from the hips. Huge shell-like structures on each side of the head—ear flaps that could trap the slightest sound. A peculiar excrescence over the closed eyes, like a pair of spectacles. Feet that were hoofs! A torn jerkin and loose fitting shorts of yellow material covered him from neck to knees.

Tom leaned over and shook the sleeping figure gently. "Charlie, Charlie, wake up!" The eyes opened, panicky fear stared out.

"Charlie, it's Tom, don't be scared."

THE mountain heaved up to a sitting posture. Now that he was awake, and the black face was mobile with emotion, I could think of him as an intelligent being. Gradually the queerness wore away.

"Charlie, these here's the wise men I told you about. This is Perfesser Chapin, and that's Mr. Dunn. They're friends, Charlie, do you understand? They're friends, and they've come to help you."

The black looked at us estimatingly. Seated on the ground as he was, his head was on a level with my shoulder. Then a really intriguing smile came over his countenance. He said something, in a harsh guttural voice. The words were familiar, but I couldn't quite catch the meaning. These people of the future spoke an English that had been distorted by long years of evolution.

"He says he's glad to meet you, and he wants to thank you for coming."

"Yes, I understood," Sid broke in. "If he speaks slowly I shan't need an interpreter." I too, found the black's language easily intelligible after a few minutes intent listening.

"One thing is certain," Sid said, after Charlie had outlined the situation to us, in confirmation of Tom's tale, "we cannot bring the Robots into our world. Our story of their origin would be disbelieved. They would be treated as freaks, made the subjects of scientific study, or public amusement. I can see only misery and unhappiness for them."

"You're right, old man," I replied, "That's no solution. And yet, they cannot exist for long in their present circumstances. Either the Jed and the Masters will find a way to destroy them, or they will starve to death when their present food supply runs out."

In that queer, distorted English of his, Charlie broke in. Eloquently he pleaded with us not to abandon him and his comrades to the mercy of the Jed. A strange sympathy moved me, I could read its reflection in the countenance of my friend. Suddenly, an idea struck me. "Sid," I burst out, "why can't we go back with him? I'm sure we'll be able to work something out when we see the lay of the land."

"I was hoping for that." Sid's eyes glowed in the dim light. "That's just what I want to do. But I didn't suggest it. I was afraid my scientific curiosity, my desire to see the world as it will be in 20,000 A.D., was clouding my judgment. What do you say, shall we go?"

"Go it is!" A great surge of excitement flooded me. Adventure, undreamed of adventure, called to me. Charlie caught the drift of our talk, and his face, too, beamed with joy. But Tom was aghast.

"Go there!" he exclaimed. "Why, ain't I told you enough about it? I wouldn't go back there for all the money in the world."

"Oh, go on, Tom," I chaffed him. "You know you're just kidding us. I'll bet we can't make you stay home. You're just a-raring to go. I can see it in your eyes."

The lad was actually shaking with fear. He was white. "Who me? Gee Godfrey Whizzikers! Me go back! Not after I saw what the Jed done. No sir! Not me."

"You can stay home and tend to your 'taters," I soothed him.

The arrangements were quickly made. Charlie was to remain hidden. We should return to the city, make our preparations, and come back to Blaymont the following afternoon. Then—the Great Adventure.

And so, the next afternoon, we came to the edge of the Vanishing Wood. Tom was with us, muttering dark forebodings, making last efforts to dissuade us. Strapped on my back, and on Sid's, were great packs. We had a store of food, and certain instruments that my chum had insisted on carting along. There were other things, too. I shall not bore you with a detailed inventory. Strapped to my waist was the holster of a .38 automatic, relic of army days. And Sid tottered under the weight of an elephant gun that he had raked up from somewhere.

Charlie met us, towering darkly. All four of his arms were waving with excitement.

We shook hands with Tom, said goodbye to 1931 and the world we knew. Then we turned, and followed the Robot.

A few steps between the towering arboreal giants, and we came to a little clearing. Even as I looked beyond, the story of Tom's adventure flashed back to me.

For across that little clearing the trees were queer. No longer did they soar straight upward toward the life-giving sun. They were twisted, strangely distorted, oddly bent as though gnarled with fear. And, though there was no wind, their leaves were quivering.

On each side of a path the trees leaned away, curved in weird, uncanny twistings. And the path broadened as it dove deeper among the knotted trunks, so that I appeared to be looking into the small end of a funnel. The path broadened. I could see its other end—or could I? For there was nothing there!

NOTHING. Not a vast spread of sky such as one sees ahead when mounting a long straight slope whose crest hides the horizon, not a far spreading desert expanse. Simply, terrifyingly, nothing.

I glanced at Sid. His usually smiling face was grim, his lips pressed in a tight line, his eyes glowing like black fire in the whiteness of his visage. "Come on, Ned," he muttered, forcing the words between clenched teeth. He moved forward. I forced my leaden feet to follow.

The huge form of Charlie entered the path—and vanished! A moment before he had loomed there, his head brushing the lowermost limb of a forest giant. Now—he was gone—as if he had never been!

Sid stopped across the margin of the clearing, blinked into non-existence. I gasped, a deathly fear at my heart. I was sorely tempted to turn and run for it. Then I too plunged into the fateful path.

A vortex of unknown, unknowable forces seized me irresistibly. I whirled down the funnelled path, the trees on each side writhing in fantastic, giddy dance. Suddenly, there was no up, no down, no Space, no Time. Even the parts of my body seemed to have lost relation one to the other, so that my head might well have been at my waist, my arms at neck or knees, for all I knew.

Path, trees, sky, sun disappeared in a vast blazing nothingness, a white nothingness through which I slid. Thought itself vanished, and consciousness was but a coruscating burst of white hot sparks that met, and whirled apart, and met again and flared asunder in a chaotic flashing kaleidoscope of whiteness. Eternally I heaved and fell.

Then—I was lying flat on my back, in the little clearing. And there were Sid and Charlie sitting up, blinking in dazed bewilderment.

"Are you all right, Ned?", my chum asked, anxiously.

"Fine. But what's it all about? Here we are, right where we started from."

Sid grinned. "Yes—we're where we started from, but we're not when we started from. Not by some score thousand years."

"Why—what do you mean?"

"Just that we're in the year of our Lord Twenty Thousand and Thirty-two, or thereabouts."

I stared at my chum for a moment uncomprehendingly, then I remembered. Of course! We had travelled in space not at all, but in Time! Again I remembered Jenkins' story. He too had thought to find his old familiar world just beyond those trees through which we had come.

Charlie was on his feet. "Wait, till I return."

In a minute he was back, and with him eight others, eight gigantic blacks with the same four waving arms, the same hoofed feet, the same peculiar excrescences over their eyes. Now, at last, I began to really feel that I had reached into some other time. For peculiarly enough, where before Charlie had been an abnormality, a freak, out of place we knew, now he and his comrades seemed to belong, and we were the interlopers. That feeling stayed with me as long as we remained in the world of 20,000 A.D.

The Robots had erected for themselves a little hut near the margin of the wood, and they made us comfortable in it. Here we rested, and talked, while the light faded, and the shadowy dimness of the grove deepened into darkness. At last I said: "Sid, I want to take a look outside, I want to see what sort of place we have landed in."

My pal nodded. "I'm just as anxious as you. What do you think, Charlie, is it safe?"

"We often scout around the edges. It is safe as long as you don't go too far to be able to get back quickly at any sign of danger.

I parted the leafy curtain, and peered out. Bright moonlight flooded a fairy scene. For mile upon mile a flat plain stretched, a vast formal garden that might have been fashioned for some king of kings. Hedge-bordered paths of softly glowing gravel curved between banks of flowers, of gorgeous flowers whose like I had never seen. Supernally sweet fragrance was wafted to me on a gentle breeze. Soft fountains plashed in quiet symphony. And a myriad dancing sparks of light shuttled and weaved among the swaying blossoms.

One of the paths skirted the wood, its pebbles glowing iridescent in the moonlight. It curved in a great circle, and in the very centre of the circle stood a luminous form of glowing light that was a statue.

VAGUE and misty as it was, the sculptured monument drew me to it with a yearning to see more of it. I slipped out, heedless of Sid's clutching hand, of his low cry of warning. I slid soundlessly across the soft carpet of sod, and the cold light and the sweet odors embraced me in a flooded aching beauty. I drew close to the soft shining statue, and now I could see it plainly.

In heroic proportion, the form of a man towered there, a man such as I, yet somehow different. A long grey beard flowed down over flowing robes, and the face radiated a wisdom such as never had sage of our time attained. Wisdom, and goodness, and something else, something inexpressibly divine.

Almost it seemed alive, that figure. I could feel those kindly eyes bend their wise gaze on me, welcome me. Why—they were moving! A deep voice thrilled me to the core with its slow accents. But it was a tired voice—one that had probably spoken this message through the ages to countless others that stood before it.

"I am Arkon, the Wise. I it was who devised the means by which first Man shook the dust of Earth from off his feet and voyaged through space to other stars.

"When the great Revolt of the Machines swept over the Earth, and the doom of Mankind seemed sealed, I gathered a small company, and set off for outer space, seeking a new home for the race. Nothing more has ever been heard from me, nor from the brave band of adventurers who departed with me in the ship I had devised.

"That the memory of a wise and brave and good man might be preserved forever, the Jed in his wisdom decreed that this image of me be created, and Tarom fashioned me."

"Marvellous mechanism, isn't it?" It was Sid, at my side. I hadn't noticed that he too had slipped from the covert. "And yet simple enough," he continued. "There must be a beam of light projected from somewhere, that the spectator interrupts. It's focussed on a photo-electric cell, and the cutting off of the light causes a change in the potential of the current that starts the Speaking mechanism."

That's Sid for you!

A faint whirring drew my attention. Far in the distance I could make out a speck, floating about ten feet above the ground. Rapidly it drew nearer—a tiny boat-shaped object, approximately the size of a small canoe. Above the gunwale I could dimly descry a domed head. A Master! Doubtless sent by the Jed to intercept us.

I whirled, calling to my chum, who was busily examining the monument. "Sid, quick, back to the wood!"

We barely made it in time. As we dove into the underbrush the Master had landed, was extending a tube in a tentacled hand. A thin flame spurted through the night, spattered harmlessly against the edge of the Wood, not three feet from where we crouched. The Wood was inviolate! The Master stood there, and, though his face was like nothing in my experience, I could read in it a surge of baffled rage.

Tom's description had been accurate. Of the strange being's five feet of height, fully half was a great head, egg-shaped, hairless. I could see the staring, lidless eyes, with the pouches above that held an additional lens for close vision. The triangular breathing orifice with its pulsating membrane was clearly defined in the moonlight. And the puckered dot below that was the toothless mouth.

The torso was squat, cylindrical, and the stemlike legs ended in huge splayed hoofs like the Robots'. But the most striking features of the queer creature were its arms and hands. Not more than a half-inch thick were those arms, and they writhed and weaved like two elongated earthworms. At the ends they split into five thinner tentacles, waving fingers. Like the earthworms they resembled, those strange limbs could be extended, for five or six feet, or retracted so that they were but inches long. I shuddered. This, then, was the supreme evolution of man!

SUDDENLY, the creature was looking upward, interest, curiosity, astonishment growing momentarily more vivid on his countenance. I followed the direction of his gaze. Far, far above, I could see a fleck against the lucent blue-black of the sky. Swiftly it fell, ever nearer and nearer, till it grew into a sphere, glinting metallically. A burst of flame flared from it, died away. The speed of the descent checked. The metal sphere drifted downward, settled softly on the grass.

I felt Sid's hand clutching my arm, but I couldn't tear my eyes from that ten-foot ball. The Master was staring at it in a manner that told me it was as alien to his knowledge as to mine. What was it, where had it come from? Palpably fashioned by intelligent hands, could it be a space ship, a wanderer from some other star?

A portion of the sphere's surface swung open, a sector of the shell a foot thick. Something moved within. Then—a man stepped out! Of all the astonishing, impossible things! From this craft from another planet, into an Earth peopled by four-armed black creatures twelve feet tall, and balloon-headed individuals with tentacular limbs, came a being as like man of 1931 as these other creatures were different! No eery shape, no fantastic, unimaginable nightmare form, could have astonished as half as much as the appearance of this tall, gray bearded old man, whose human countenance radiated benignant wisdom.

He moved with infinite grace, this man, as he turned toward the Master. But the calm dignity of his face gave way to startled surprise, for the Jed's subject was aiming the venomous ray tube at him. Another instant, and swift death would claim him.

Another instant—but in that instant my gun had somehow leaped into my hand, had barked, and the Master sprawled unconscious on the ground.

We were out in the open, Sid and I, shouting. "This way, into the wood for your life, hurry." The stranger turned toward us, bewilderment in his eyes. Hut he seemed to sense our friendliness, instinctively to realize the urgent peril of his situation. For he sped unquestioningly for the shelter of the thicket.

Sid was shouting now, all pretence at caution gone. "Charlie, come here quick!"

A huge thrashing in the wood showed that his calls had been heard and obeyed. He snapped staccato commands. "Ned, into the wood with the Master." He stooped and snatched up the ray tube where it had fallen. "Charlie, have your friends get that ball in. And you help me with the air boat."

I slung the Master across my shoulder, ran for cover. Sid and Charlie, the flier on their shoulders, followed on the run. There was need for haste. A buzzing as of a swarm of angry bees warned of the swift approach of a bevy of Masters. From the corner of my eye I saw the huge sphere heave up to the shoulders of the giant Robots. That great mass was as nothing to their strength. Quickly as it takes to tell we were all back in sanctuary with our burdens. And none too soon. For outside a dozen aircraft had landed, there was a vast waving of tube-wielding tentacles. Shrill screams of baffled rage filled the air.

Was it some superstitious dread, still living in the consciousness of these supermen, some atavistic taboo that held them back from the margin of our refuge? Hundreds of centuries of inflexible law raised a barrier between them and us. I saw them stand there, not daring to set foot across the line that marked the edge of the Vanishing Wood. There was nothing to prevent their rushing across that line. If they did, we were lost. Our puny weapons could avail us little against their death-dealing rays. But, though they pressed close, they did not come.

POTENT indeed must have been the fear of the Jed that had forced Charlie and his companions to bring themselves to seek refuge here.

Once indeed, I thought they had conquered their fear. There was a concerted surge toward the grove. I raised my gun, prepared to sell my life dearly. But, just as another step would have told the foremost that his terror was groundless, he checked himself. The others halted too. We were saved.

Suddenly, as though some telepathic command had reached them, all leaped into their craft. The buzzing sounded again, the air-boats lifted, they were gone.

The newcomer was speaking, his deep well-modulated voice strangely familiar. He too, spoke an English, changed, but intelligible with careful listening. A different dialect from that of the Robots, but the root was the same, the language in which I write.

"Apparently I must voice my gratitude for a daring rescue," he said. "Strange that I should be so attacked at the moment of landing, and by so extraordinary a people. Or are they descendants of the Machines? I had expected to find great changes on Earth, but nothing like what I have already seen. Are you remnants of some few who escaped the great revolt? My mind is bewildered."

All this was incomprehensible to me, but my scientist friend appeared to understand. I noted that his face was lit with a glow of discovery, of wonder.

"As for what we have done, that is nothing," he replied to the stranger. "We are overjoyed that a most extraordinary chain of circumstances placed us in a position to aid you. But, before I explain, may I ask who you are, and whence you come?"

The other bowed his head, gravely. "I am Arkon the Thirty-Fifth, and I come from Neptune on a voyage of exploration, to determine if Earth is yet ready for the return home of my people."

Now the amazing truth flashed on me. Arkon the Thirty-Fifth! Arkon, the original of the image that had just spoken to me, must be this man's ancestor. I knew why this voice was so familiar, why his lineaments had seemed not quite strange.

We were again in the hut. Sid had just finished the narrative of the astounding events that had brought us here. Difficult indeed had it proved to convince Arkon of the truth of our story. But, somehow, he had accepted it. Now, he was telling us of the strange Odyssey of a little band of adventurers, somewhat of whose tale we had already guessed.

"My ancestor, the first Arkon, had just completed the final testing of a vessel he had designed to navigate space and visit other worlds, when the insurrection of the Machines broke forth. They swept all before them, and he became convinced that the race of man was doomed. Despairing, he gathered together a dozen people, men and women, and embarked for outer space, to seek a new home for mankind.

"For a long time the little band wandered through the void. They essayed a landing on Mars, but found conditions impossible for living there. Finally, just as all hope was gone, they reached Neptune. There they discovered an intelligent race of reptilian origin, and were enabled, through the genius of Arkon, to make known their needs. An agreement was entered into, by virtue of which the Earth people were granted a small area to settle in.

"Adjustment to the changed circumstances was difficult, but my ancestor had chosen his companions well, and the band survived. They made an abiding place for themselves, but never did they feel that they had found a home. Always a yearning for Earth gnawed at them, a longing to return to their native planet.

"A thousand years passed. Children were born, grew old, and died. But ever the old traditions of the beautiful Earth from which their fathers had been driven were kept alive, and the thoughts of each member of the little community turned over to a return. But, for many reasons, the attempt was never made.

"A year ago, however, notice was served on us that the time of our sojourn on Neptune was drawing to a close. The Neptunians were proliferating rapidly, the planet was growing overcrowded, and every bit of surface was needed for their own race. We were given two years to determine on our course. At the expiration of that time, we must leave, or be killed.

"The leadership of the Earth people had remained a hereditary obligation of the eldest male descendant of Arkon the First. I am the present ruler. We had always carefully preserved the plans of the first space ship, and I ordered sufficient duplicates to be built to carry all our people. I called a Council, and the general view was that, if possible, we should return to Earth.

"But we had no knowledge of what had eventuated on our home planet. Had the Machines conquered, as was thought? Had they found a way to reproduce themselves and overrun the Earth, so that we should be repelled, or massacred? Or had they rusted out, leaving the world a barren, unpeopled waste? Or had mankind triumphed in the end, so that we would be welcomed back by our own people? These, and many other questions must be answered before our nation could choose the goal for our exodus.

"SO I decided to scout ahead in a small model of our space ships, to span the illimitable spaces separating us from Earth, and, venturing alone, to determine the feasibility of our homecoming.

"I came. And my heart is sore within me. From what I have already seen, and from what you tell me, Earth holds no promise of peace for my people. Mankind triumphed over the Machines, indeed. But better had the race died than evolved into the ruthless, cruel, inhuman monsters that now people the world.

"We who, on an alien world, have kept alive the literature, the art, the religion, the dreams of a Golden Age, can find no peace, no home here in a world dominated by a naked brain, administered by soulless minds who know no pity, no love, no purpose save the ruthless attainment of their own desires. Even the beauty of that garden out there is a heritage from the age in which Arkon the First lived and dreamed.

"These Masters are the descendants of a little group of so-called supermen who, isolated in a group of their own high in the Appalachians, experimented with artificial methods of propagation, with intensive intellectual development, with all sorts of scientific interference with the natural evolution of the race. I have read their story in one of our old chronicles. But they were left severely alone by the rest of mankind.

"Apparently they seized their opportunity during the great insurrection, and made themselves dominant over the Earth. With their infernal concoctions they subjugated what remained of the rest of humanity, and made of them imbecile slaves. They even changed their very form, their color, and produced such poor creatures as these." He indicated Charlie and his friends. "What hope would we have to be left in peace should we return?

"No. Better that we wander again through space, and drag out the weary years of our exile in such wandering, than return here... I must go and carry back the sad tidings to my people."

He bowed his head as he finished. I was inexpressibly moved by the tale he told.

I felt conveyed to me the age long nostalgia of the exiles for their homeland; the daring of this man, speeding through the far reaches of space, all alone, buoyed up by the hope that he would find that at last it was possible for his people to return, and now his terrible disappointment. A thought began to flicker within me but, before it had taken form, Sid voiced it.

"Do not return as yet, Arkon. Perhaps we shall find a way to defeat the Jed and his cohorts and reconquer Earth for your people, and for these downtrodden Robots. My, friend and I came to this time for that very purpose, we intend to make a try at it. Perhaps your knowledge added to ours will bring success."

A faint hope kindled itself in the noble countenance of the man from Neptune, even. as he replied: "But how can you dream of such a thing? You tell me that this Jed has immeasurable knowledge, immeasurable power. His subjects are many, we are but a handful. I fear that you are carried away by an enthusiasm unjustified by logic."

I was proud of my friend as he answered. "It is true the task is a well nigh impossible one. It is true that the odds are tremendously against it. But—in the long history of the Earth impossible tasks have more than once been accomplished by determined men. Let us make up our minds that the thing can be done, and by God, it will be done!"

Arkon rose, his face glowing. He stretched out his hand to Sid. "I'm with you. We'll do it!"

And so we three, so oddly assorted, devoted ourselves to the conquest of a world.

BY tacit consent, leadership was given over to Sid. He drove straight at the essentials.

"In order to make any plans, we must gather as much information as possible. At present we know very little about the people we are to combat. Jenkins' observations on his previous adventure here furnish the bulk of our knowledge. That is very little. His lack of education, his ignorance of science, prevented him from learning more than the most superficial things. The Robots' knowledge of their world is also little better than nebulous. From neither of these can we obtain the facts we must have.

"However, due to our recent adventure, we are possessed of two further means for gaining information. We have captured a Master. Ned's bullet, by great good fortune, merely stunned him. And we have one of the enemy's flying machines. Trust me to find a way to make use of it."

"Suppose we have the Master brought in," I suggested, eager to make a start.

"Very well." Sid nodded to Charlie, who all this time had been listening silently to our talk. In a moment he had hauled our prisoner in.

"What is your name?" Sid began the interrogation.

The Master stood defiant, not saying a single word. An ugly furrow across the top of his great balloon head showed where my bullet had creased him.

My chum took from his pocket the tiny tube, no larger than a fountain pen, that we knew could project a deadly ray.

"Look here. I have this, I shall not hesitate to use it if you cross me. The only thing that keeps you alive is our idea that you can be of use to us. Make up your mind quickly." I didn't realize that my old friend could look so menacing, that his voice could be so cold, so deadly threatening. "What is your name?" he asked again.

"Tarom," came the low answer.

"Your position or function in the state?"

"I am of the Guard of the Jed."

"Why did you make such an unprovoked attack on this man?" pointing to Arkon.

"Since the advent of the Primitive[3] the Jed has ordered that all beings like him are to be summarily killed without question."

[3] The designation for Tom Jenkins on his first visit. See "In 20,000 A.D."

"What is the Jed's reason for that?"

"The Jed orders, he does not explain."

"What means of offense and defense have you?"

"We Masters have our ray tubes, they are sufficient. We have only the Robots to fear, combat among ourselves is strictly forbidden. The Jed has other weapons. What they are, I do not know. I only know that when a Master refuses implicit obedience to the Jed he dies within the instant, and his body vanishes without trace."

"How does the Jed communicate his orders to you?"

"By telepathy—we hear a voice speaking in our inner being and know it is his."

"Can you hear it now?"

"No. Jed's power does not extend into this Wood; long have we known that."

We stood pondering, a trifle careless, I'm afraid. For the Master straightened suddenly, and before any one could stop him, was dashing madly through the wood. We rushed after him, reached the edge just in time to see him darting across the great level sward. Heedless of everything but rage at myself for having let him escape so easily, I was about to dash after him, when Sid's arm caught me. "Don't be a fool, Ned," he cried, "once out of this sanctuary and you are a dead man."

In a rage I raised my revolver, aimed after the fleeing figure. A grave voice spoke quietly! It was Arkon. "Nay, we desire no blood on our hands unless it be absolutely unavoidable."

Ashamed, I lowered the gun. "But our chance for gaining knowledge of how to combat the Jed is gone."

"Then we must discover other means."

I pondered the remark. Still smarting under what I deemed my laxity in permitting our prisoner to escape, I cast about for some other plan, something I could do to efface the stigma. Now ordinarily, I am not a very brave man. I am not one of your roaring swashbucklers who love the bright side of danger and the tang of overwhelming odds. So that it must have been a slight touch of madness that caused me to propose the rash adventure I did.

"I have it," I cried excitedly, "the air boat we captured."

"Well, what about it?" Sid asked.

"Why man, don't you see it? The alarm has been given and shortly there'll be an impenetrable guard thrown about this place so we'll never have, a chance to break through. And even if we did, what could we do, knowing nothing at all of what we'd meet. Charlie and the Robots can't help us much. So before the Jed's guards get here again, I'm going to get out of here—in the Master's aircraft."

I WAS carried away by my own enthusiasm.

"Don't you see. It's night now. I can scout around, get the lay of the land, find out things."

Arkon looked at me with a smiling wonder that made me feel quite heroic. Charlie was positively worshipful. There is nothing more heady to a naturally timorous man than the wine of admiration. I felt equal to incredible feats.

It was Sid who pricked the bubble of my vainglory. Possibly he knew me too well.

"Most chivalric, this idea of yours, Ned," he said half-ironically, "but you've forgotten one little fact that would end your scouting disastrously."

"What is that?"

"Don't you remember what Tom told us? That the Jed is able somehow, not merely to communicate his thoughts to others, but also at will to tune in on what passes through anyone's mind within his sphere of influence. How far do you think you could get before he would know it?" Charlie nodded his great black head vigorously in assent.

My whole bright scheme collapsed into nothingness. Of course it was foolhardy. And being what I am, who can say that there wasn't just a bit of relief about my disappointment.

Then Arkon spoke, gravely, unhurriedly. Never in all the desperate adventures we were to live through together, did I see him flurried, his noble demeanor ruffled, or his voice deviate from its even music.

"It is a remarkable coincidence that I have with me the means to combat in at least this one thing the subjugator of our race. Know that the reptilian denizens of Neptune, our outcast home, also possess this strange power. For a generation the thoughts of our people were an open book to our neighbors, a source of infinite embarrassment. It was Arkon the Twelfth who toiled unremittingly until he discovered the remedy. He invented a thought screen that, when worn, effectually shields the wearer from intrusion into his private thoughts. Since then, all my people wear the golden band, and once more their secrets are inviolate. I have one with me in the space ship."

The cold light of the confirmed scientist glowed in Sid's eyes, a light somewhat clouded by a skeptical reserve. "Impossible," he burst forth, "how can you shield or hide thought emanations by mere metallic bands?"

Arkon smiled benignly. "Nothing is impossible, oh visitor from an earlier age. Man long ago discarded that outworn word from his speech. But come with me to the space flier and I will show you."

Sid pressed behind him eagerly but, truth to tell, I lagged a bit. Now I would have to go through with my quixotic attempt, conceived in a moment of enthusiasm. Recovered sanity warned me of the inevitable perils ahead.

We entered into the interior of the tiny flier from another world. The walls were of the same strange metal that glowed with a soft radiance. Unusual looking instruments were clustered on the concavity, instruments that meant nothing to me. But Sid examined everything with a sort of covetous eagerness, as though he would pluck out of their very inwards the secret of interplanetary flight.

Arkon picked up a thin metallic band, and handed it to Sid. I stared at it in awe. It was open at one end, two small metal filaments marked the terminals. On the other side of the circlet was a little protuberance, from which numerous fine wires ran along the graved surface to the filaments. Arkon explained.

"If I remember my primeval history correctly, in your day you had learned that thought is merely a series of high frequency electrical vibrations emanating from the neurons imbedded in the brain tissue. Like all vibrations, they are carried through the ether, away from the point of origin, but, since they are very feeble in intensity, they do not progress more than a few feet before they are so faint that the most delicate ammeters would not register their presence. Evidently, however, the Jed and the Neptunians have discovered a method of amplifying and directing these faint waves so as to send and receive the signal with undiminished intensity.

"With these fundamentals in mind, Arkon the Twelfth set to work, and this was the result. Imbedded in the little knob at the back of the circlet is a very minute transmitter that generates and broadcasts waves of a period exactly corresponding to the thought vibrations.

"The current flows along the tiny wires, bridges the gap between the electrodes and set up a field of force that completely encircles the head of the wearer."

"I understand all that, and I get what you're driving at," Sid broke in, "you are attempting to set up an interference so that the artificially generated waves are just half a wave length behind the natural thought vibrations, the crests of one fitting exactly in the troughs of the other, so as to create a blanketing effect."

"Exactly," Arkon beamed, a bit surprised. "I had not realized that your time was so far advanced scientifically."

"You flatter us reporters," I interrupted, "it's still Greek to me, even though Sid seems to understand.""

BUT my chum plunged on heedless of praise or interruptions.

"All very pretty, but how do you modulate the wavelengths of your transmitter so that it emits waves of exactly the opposite phase."

Arkon smiled approvingly. "There is a very delicate micrometer screw near the base of the protuberance." We examined it more closely. Sure enough it was there. He continued. "Each half turn of that screw shifts the period of vibration by half a wave length. So that is merely a matter of experimental individual adjustment for each wearer."

"But how can you tell when it is properly set," I asked.

"Put it on, and I'll show you," the earthman from Neptune replied. I did so, the flexible band encircled my forehead, with the knob in front, the electrodes in the rear.

"Now turn the micrometer screw until you notice something unusual."

My clumsy fingers found the little mechanism, twisted it slowly. Nothing happened. I was beginning to fear it was some Neptunian jest, when suddenly my usually halting thought processes clarified. Instead of vague chaotic tags and shreds of thought flitting through my mind, consecutive ideas came to me, clear cut, sharp edged, crystalline.

I stopped short with an exclamation of surprise. Never before had I felt my brain so keen, so brilliant.

"Ah, I can see you have found the proper vibration series," said Arkon, who had been watching me closely.

"What is it, how did you know when to stop?" clamored Sid, bursting with curiosity.

I described my sensations, Arkon nodding his head the while. "That is so. Your thought vibrations are now completely shielded from the fest of the world. You see, by forming a wall of neutralization, the waves of thought pressing behind are thrown back upon themselves, and they reinforce and amplify so that the sensations, the ideas they represent, are made more vigorous, more intense."

I was ready to shout with joy at my new found keenness of mind. "Look out Sid," I warned him jokingly, "from now on I'm the brains of this outfit. You're just my dumb assistant."

"Take off your disguise, I know you," he mocked back.

It was Charlie who brought us back to a sense of reality. He had been listening to us uncomprehendingly, with a touch of impatience. Now he pushed forward, timidly.

"Look, Masters, (that was the only salutation of respect he knew) the night is almost half over. If anything is to be done, there is no time to lose."

"Righto," I exclaimed, "I'm off."

"Here, where are you going?" exclaimed Sid in alarm.

"For the air boat of course."

"Nonsense, I won't let you go alone. I'll go too."

"There is only one thought-shield," came the grave voice of Arkon.

"Then I'm elected," said Sid, and he tried to grab the circlet off my head. I ducked just in time.

"Not a chance. I'm a reporter, don't forget. I have a natural nose for news, for prying into things. Besides, as the scientist of this party, your place is here, to concoct schemes in conjunction with our noble friend."

We argued back and forth, but the more Sid pleaded the more stubborn I became.

I would go, and no one else. Finally he saw how obdurate I was, and gave in.

I hastened to the boat before he could change his mind. I examined the controls. I'm a rather fair amateur pilot of aircraft and it did not take me long to get the hang of the contraption. I was all set.

With a final squeeze of the hand that spoke volumes, Sid stepped back. There was a queer catch in his voice as he bade me Godspeed. The darned cold blooded scientific cuss—I never knew he could show emotion!

I waved with a cheeriness I did not feel, pressed the proper button. A haze of blue light, and, the craft lifted softly off the ground, straight up through the trees.

AT about a hundred feet elevation, I pressed another button. The soft blue glow turned to a purplish red, and the canoe shaped car darted swiftly over the plain. In a few seconds the Vanishing Wood was far behind.

To keep myself from dwelling nervously on what awaited me, I examined the mechanism of my captured craft a bit more closely. There was no motor, no propeller, none of the manifold equipment so necessary in our day for propulsion through space. Only a small oblong box in what might be termed the prow, to which the control buttons were attached. Not a whir, not a murmur, to disturb the even tenor of our flight.

I puzzled it over a bit. Then the answer dawned on me. Even in the year 1930 A.D. people were talking of the possibilities of broadcasting power, to be picked up and utilized by factories, automobiles, aircraft, and what not. Of course, that was it. Some central station sent out power, we tuned in, so to speak, and behold, we moved along on the crest of waves.

Now that I had satisfactorily disposed of that problem, and was unreasonably elated at my unsuspected scientific knowledge—fool that I was, I forgot to credit the thought-shield on my forehead—I glanced over the side of my vehicle. The park-line character of the land continued. But off to the west, and rapidly looming larger with the speed of my flight, lay a great cluster of buildings, the vast city of the Jed.

My heart beat faster. I was approaching my goal. It was utterly unlike what New York would look like, viewed from a distance. Instead of angular monstrosities, of jumbled canyons of oblong boxes upended, here were rounded domes and undulating curves, gleaming rose and blue in the bright moonlight. Inevitably I was reminded of the many domes of the Alhambra, of the Taj Mahal.

But my aesthetic wonderment abruptly ceased. For, straining my eyes, I saw a cluster of dark specks stream out from the magic city, and hurtle directly for me. It took but a moment to guess what they were. Air boats like my own, manned by Masters, planning to give me a warm reception.

I could have turned tail and fled back to the Wood and safety. Afterwards I wondered at myself for not having done so. But at the moment the thought did not even occur to me. I was out on a mission, and I must accomplish it. I had my revolver with me, of course, but, that would be small protection against the ray-tubes of the Masters!

I took the only course possible. I swerved, and shot off at an angle. The distant specks turned and darted across my line of flight. I pressed the button all the way in; I was racing at maximum speed now. If only I could beat them to the point of intersection, I could then swerve around the city, and take my chances on losing my pursuers.

It was a race! Faster and faster we shot along, the aircraft of the Masters gaining handily. Already I could see the great bloated heads peering over the edges. Ray tubes glinted evilly in the moonlight, all pointed ominously at me. I measured the distance between us. It was no go. One boat at the head of the procession, would either crash into me or be right on my tail in short order.

I drew my revolver, grimly determined to sell my life as dearly as possible. Faint flashes darted from the ray-tubes. The streaks of light burnt along, stopped short yards away from my hurrying craft. That gave me some measure of comfort. My automatic could shoot further than their weapons. There were six bullets. Six bullets must mean six billets. Even in my great danger, I played on that little phrase.

The first air car was almost on top of me. I twisted the steering knob, angled off. He followed. I could see the Master crouched low. His ray projector pointed, the flame leaped the gap, sheared off the rim of my boat as cleanly as though cut with a knife. It whiffed into nothingness. I shuddered at the thought of what the damned ray would do to me if it connected. Then a surge of rage swept through me. The dirty murderer!

I raised my revolver, sighted carefully, and let him have it. It caught him square on the bulging, leathery forehead, just as he was coming up to take another shot at me. The whole head collapsed like a pricked balloon—evidently there was not much bony structure—and the body dropped out of sight. Their craft, left suddenly to its own devices, plunged erratically about until it crashed headlong to the ground.

THE other Masters, beholding the swift demise of their leader, held back. They were not aching for a dose of this unknown weapon of mine. "You fellows may be far ahead of us in knowledge and all that, but you've lost some of the guts and stamina of your ancestors," I thought savagely.

It was funny? really this assumption on my part of all the courageous instincts of my age. But I didn't stop to philosophize. Instead, I turned swiftly about the great city, and though the Masters put up a halfhearted pursuit, I soon distanced them. They trailed out of sight.

"Now what!" I said to myself, as I careened past innumerable gleaming domes. The east was paling, sure precursor of the dawn. It wouldn't do to be found wandering about in the daytime. I'd pass out of the picture in a hurry. I'd have to land somewhere, hide the boat, and lay low until night again, when I could prowl around. But nary a forest, nary a grove of trees, broke the monotony of the great parkland. The city, of course, was out of the question.

Wondering what to do, whether it wouldn't be wise to turn back, the question was suddenly answered for me, neatly and effectually. The air boat slackened speed suddenly, coasted a while, began to drop. Frantically I worked at my controls—they were all properly set. The craft went into a tail spin. Strangely enough I was calm, unworried. I realized what had happened. That infernally clever Jed had called back his Masters, then calmly cut off the power. I was the only one left in the air, so naturally my boat quit me. Just as I had worked out the whole thing to my satisfaction, I crashed.

When I came to, I was lying in a mass of wreckage, bruised, battered, but otherwise all right. I scrambled from under, thanking the Providence that protects fools and drunkards for my miraculous escape.

I looked about me in the dim dawn-light. There was no time to be lost. The Masters would be out after me again in force. Straight ahead loomed a huge structure, glowing with a shimmering golden light. A great central tower, domed on top as were all their buildings, rose boldly into the air. A massive battlemented wall, some twenty feet in height, swept in an endless arc. Some hundreds of yards from where I stood, was an opening, a thin slash in the great stone escarpment. Dimly to be seen in front of it, guarding the entrance, was a giant black figure, huger even than Charlie. A Robot!

How could that be, I wondered! Hadn't Tom and Charlie both assured me that all the Robots had been slain in the great revolt, except those few who had escaped to the Vanishing Wood? Again my brain was working with unwonted clarity—due, as I've said before, to the thought-shield.

Of course! The Mothers were still alive, the ova were still to be had. The Jed had created a new race of Robots, larger, possibly without any brains at all to succumb to the temptation of a new rebellion. As for their quick growth, it was merely a matter of activation that should be simple to the vast brain that was Jed.

But this train of thought put a new idea into my head. I had wondered at the vague familiarity of this imposing structure. Now I had it. It was the City of the Mothers that Tom had so crudely, yet effectively, described to us.

A fantastic scheme presented itself. Tom, I remembered, had hidden away in its vast interior. Why could I not do likewise? But there was the Robot guard at the gate. What about him? He was too immense for me to tackle physically. I should have stood no more chance than an insect underfoot. I could shoot him of course. But the idea was repugnant, the poor dumb creature had never done me any harm.

I studied the situation, while they gray dawn grew ever paler in the east. Soon I would be visible to all and sundry, utterly helpless. There was no other means of escape except into the City of Mothers, and there, barring my path, was the unsuspecting Robot.

Not only my own life, but the safety of my friends, the salvation of the earth-people on Neptune, the rescue of this strange future earth from unspeakable tyranny, depended on my next move. I hesitated no longer. The automatic was in my hand. A sharp report. The poor Robot staggered, then, like a gigantic tree laid low by the woodsman's axe, crashed majestically to earth.

IT was the first and last time in my life that I shot a human being in cold blood, yet under the circumstances, what else could I do? Even at this late date, I suffer a twinge of conscience when I think of it.

Then, forgetting all but the desperate need for haste, I ran as fast as I could to the now unguarded gate. I sped past the queerly contorted body, not daring to look at my handiwork, in through the vaulted arch, intricately worked in a frieze of mosaic.

Straight ahead was the great tower, the home of the Mothers! Without an instant's hesitation, I made for it, passed through the ornate entrance, found myself in a lofty hall. Fortunately it was deserted at that early hour, or my adventure would have ended then and there.

At the farther end was the great shaft I was looking for. There it was, just as Tom had described it, a circular well, stretching up interminably, lit by a soft glow from somewhere, the walls of smooth shining alabaster. I examined the rounded wall carefully. Imbedded in the gleaming whiteness was a small round button, of green jade. I pressed it!

Though I knew what to expect, the suddenness with which I was lifted up into the air was breathtaking. It was an eerie sensation—that of rushing perpendicularly through space. Up, ever up, I winged, the smooth walls rushing past me in giddy flight.

I came to a sudden stop, floated dizzily in thin air. Involuntarily I moved my legs, was surprised to find myself walking on nothing, toward the solid marble flooring that surrounded the open wall. I lunged for it, and did not pause to draw breath until I felt blessed solidity under foot.

Again I was in luck. The great rotunda was bare of living beings. The walls gleamed golden from innumerable coruscating pinpoints of illumination. Possibly some radio-active material imbedded in the marble slabs.

I gazed at it with a gasp of admiration. Over the great concave surface were painted murals, of a magnificence of conception, a sure draughtsmanship, a delicacy of execution, that would put our own noblest artists, yes, even Michelangelo's titanic vision in Saint Peter's at Rome, to shame.

Here was spread before my dazzled eyes in heavenly blues, yellows and greens, the whole evolution of birth from the earliest primeval forms. Here were depicted vast flowing amoebas in the throes of binary fission. Then in ordered array came the method of spore formation, the budding of great tentacled hydras, the first hermaphroditic sexual reproduction of writhing earth worms, and up through more and more complex forms, until I saw, with a shock of recognition, the faultless forms of a man and woman of my own era, painted as no painter we know could have envisioned their perfection.

From that point on, all was strange to me. The tale of men and women in love grew ever more complicated, while, alas, the glorious form degenerated into bulging foreheads and hideously foreshortened limbs, as our modern civilization went on relentlessly to its coldly logical end. Then there was no more differentiation in the pictures, neuter looking beings made their appearance. Man had found a way to reproduce without sex. It saddened me, that thought! All of love, all of the romance and generous warmth of life had passed out of a world to cerebral, too intellectual, to waste its time in such youthful illusions.

The painted representations of Masters and Robots completed the panorama, the end and aim of all our striving.

But even as I stared, something happened. As though at an invisible signal, the great paintings broke into seeming life. The pictures glowed and began to move. Dumfounded I watched, thinking I was the victim of a strange hallucination. For each individual picture quivered and changed. Before my very eyes, the amoeba thrust out its pseudopodia, attenuated itself, grew slender in the waist, and broke up into two forms, each complete, that swam about on the golden walls looking for food.

The human male and female approached each other with lovely gestures. The Master gesticulated, and the Robot humbly obeyed. The whole vast scene of life was moving and living on the great surface of the rotunda.

HOW I wished Sid was here to explain the seeming miracle. Long afterwards, when I talked it over with him, he suggested that the rotunda might have been composed of innumerable thin sections, each bearing a consecutive painting, that were slid into position over each other with the speed of a motion picture mechanism. It may be so, but somehow it leaves me unconvinced.

I would have watched the enthralling, ever shifting drama forever, had not a grating noise brought me to a realization of my whereabouts. Senses once more on the alert, I shifted my errant gaze down to earth again. A door at the farthermost end was opening.

I looked wildly about for shelter. Some ten paces to the right was a door, leading—where? It was no time for idle speculation. I had to chance it. I sprang for it, pulled it open, darted in, and closed it softly behind me.

I was in a great, cerulean-hued room, luxuriously appointed beyond my wildest imaginings. The floor was covered with shimmering silken rugs, the walls were hung with rare tapestries depicting unending lovely vistas. Divans, damask covered in strange geometric patterns, were scattered about in profusion. At the farther end a fountain gleamed.

The leaping water sprayed in a million broken sparkles of iridescence back into a rose-colored marble pool. Gilded birds with bright plumage flew circling overhead, and from their blue tipped beaks issued forth entrancing melodies. Something about the regularity of their flight, the unceasing flood of melody caused me to examine a bit closer. They were mechanisms, in the very similitude of life, actuated—I know not how! A bower of delight, a Mohammedans dream of Paradise! Only the houris were lacking.

But were they? For even as the comparison occurred to me, a figure arose from a divan half hidden by the plashing fountain. I stared frankly—bereft of words, of all desire for speech for the first time in my life. My heated imagination had conjured up a veritable houri.

Tall and stately she was, overtopping me by inches, and I am no dwarf exactly. A human creature, compact of fire and ice, a glorious being whose warm features, melting blue eyes, hair of burnished gold, made me search desperately in my memory for the felicitous phrases of the poets. But there were none to do her justice—for the very good reason that nothing like this ravishing being had ever existed in the world I knew.

There was alarm, consternation, in the great blue eyes; the full quivering lips were opening to cry out, to give the alarm. The gun was in my hand, but though my life might pay the forfeit, I did not dream of shooting. Instead I essayed a stage whisper into which I threw every bit of imploring accent I could. "Don't shout,—please don't. I won't hurt you. I'll be killed if you betray me."

The beautiful creature stopped short, her eyes wide with surprise. She spoke, in the soft, slurred musical speech that once was English, her voice shaming the liquid gold of the birds that whirred in unceasing flight above us.

"Who are you, oh being that resembles me so closely, and yet are so strangely different; and what do you here in the City of the Mothers, where it is death to penetrate?"

"I am a human being like yourself, come from another age, when the earth was peopled with beings like ourselves."

An eager, puzzled look appeared in those limpid eyes. "Say you so! I do not understand what you mean by talking about another age, but are there really others who possess our forms and lineaments, others beside the few who are the Mothers? Others who are not dumb brute Robots, ugly misshapen Masters, or like unto the Jed."

A shudder of repulsion shook her, then a sudden passion went through her like a flame. "Oh human whom it is good to look upon,"—I believe I had the grace to blush—"oh unknown from I know not where, have you no thought, no pity, for the pitiful state of us Mothers—mere animal breeders for a populous earth, compelled to watch the callous Masters with foul chemicals, evoke out of the flesh of our flesh, the bone of our bone, monstrosities like themselves, or Robot beasts of burden, while we yearn for the sight of babes with rosy tinted limbs, to press and cuddle against our hearts."

She ended in a storm of passionate weeping. "It is cruel, inhuman, what they have done to us. Many a time I have peeped out into the great rotunda, and devoured hungrily the glowing shifting pictures of life and love in the past. How I trembled with strange emotions, how I yearned to be a part of that I saw. But it is not to be, for I am but a prisoner, bound here inexorably by Jed's decree—a Mother!"

EVERY fiber of my being responded to that pitiful lament—how I longed to draw that golden head upon my shoulder, to soothe that normal instinct of womanhood. But the memory of my mission, my own present danger, forbade.

"I have told you I have come from the past—the very past portrayed outside—where women there are—like you, though not so beautiful, and men like myself; where women are free to live as they deem best, where there is love and not cold chemical solutions, where babes are borne by their mothers, and are cherished and protected by them."

Her face lit up with a rapturous hope. She clasped her hands beseechingly. "What you speak of sounds incredible—but your very presence here is even more incredible, so I must believe you. If it indeed be so, take me away from here, take me with you. I too must be free, free from this wretched bondage. But take heed of the Jed, lest he—."

Her panting voice trailed off into silence. A look of horror, of panic fear, suffused the beautiful countenance. A moan burst from her. "The Jed—he has heard!"

I did not understand. Alarmed at the sudden change that had come over her, the broken phrases, I was hurrying to her side, when I too was brought up short.

A voice was speaking—a deep vibrant voice that flooded me with its tones. I whirled around to meet its owner, but there was no one. I looked vainly about in all directions. There was something curious about that voice. For all its clarity, its vibrant resonance, it seemed to lack body. It was soundless! It was something that echoed from within me. That was why I could not place it.

Realization came flooding. It was the Jed speaking—speaking to me in the innermost depths of my own brain—communication by telepathy. Even though Tom had prepared me for just this, the actual hearing of this strange inner voice sent queer shivers tingling up and down my spine. But as I listened to the ominous message, I was overcome by a deathly dread.

The cold, inhuman voice was saying. "Visitor from an age when the earth was a place of primitive savages, not far risen from the ape, do you think to escape the all-seeing, the all-knowing Jed? Once before a denizen of your times appeared among us. He was treated courteously, though he was a Primitive, but he chose to involve himself in Karet's puny revolt. Karet is dead, and so are most of his dupes. Some few eluded me in the Wood where Time and Space are warped. The Primitive was among them.

"Now you and another appear. You have aided and attempted to protect the fugitive Robots from my just wrath. You have killed a Master with a toy. You have slain a Robot at the gate of the City of the Mothers.

The cold voice grew inexorable. "You have achieved the distinction of arousing my anger. I shall crush you like a loathsome insect. Even as you are able to hear my commands, I am watching you, who deem yourself secure in your hiding place. I read your thoughts as easily as you hear mine. I know exactly where you are!"

A cold sweat burst from my pores, while the Mother stared at me affrighted. I ran toward the other end of the room, panic-stricken, seeking an outlet, somewhere to hide from the infinite brain that was Jed.

Once more the cold tones, faintly tinged with mockery, echoed within me. I paused in my aimless flight.

"I know every move you are making. It is useless for you to attempt it. There is no place on the earth, or deep within its bowels, that I cannot follow and pluck you out. Even now my guard is hurrying to your place of concealment, to seize and bring you before me. It shall go hard with you then.

"Yet, because I am merciful, because you are a poor blind primitive whose mind is still groping childishly, I shall grant you a last chance. Come out into the open, before the guard reaches you, give yourself up voluntarily, and I shall graciously permit you and your comrade to depart in the Wood to your own time. But the rebellious Robots and the earth-man from Neptune must be delivered over to me. I have spoken!"

MY knees were wobbly as the dread tones ceased their strange echoing within me. The woman had seized my arm, was urging me with passionate whispers.

"Quickly, give yourself up before they come. The Jed will do as he says. He does not break his word. You will be killed otherwise.

In this hour of danger I was sorely tempted to heed her, to abandon this quixotic atttempt to be a participant in a world and time not my own, that should not exist for me except as an unimaginable future. My own familiar world, the accustomed sights and sounds were suddenly overpoweringly dear across the wide waste of time. No doubt I had succumbed, issued forth to surrender myself, had not the Jed seen fit to tack on conditions.

I thought of Charlie, the poor Robot accidentally encumbered with intelligence, the others of his group, more vague in my memory, and then came the vision of that noble earthman and all his fellows, doomed to die here and on the Neptune that wished no more of them. All this would happen because of wretched fear for my own safety. I knew instinctively the right course to adopt, but as you may have remarked by this time, I am by nature not exactly brave, so I hesitated.

The beautiful woman was in a frenzy of alarm. She was scanning my features, stupid in their indecision. Very likely she sensed the struggle taking place within me. There was anguish in her tones.

"Stranger from another time, obey the Jed and save yourself. You cannot hope to defy his might. Go back to your own fair world and live the happiness denied to me." A sob interrupted. "It is I—Eona, who beg you. I would not see you die!"

The passion, the pleading of the lovely girl decided me. My path was clear. Yet strangely enough, the appeal of this flushed goddess, had forced a decision on me directly contrary to what she had desired.

I would not leave the others to a horrible fate. I could not leave Eona (how liquid it was on my tongue). I must chance the wrath of Jed. I would fight on to the last breath. Which grandiloquent effusions I promptly translated into suitable words.

"No," I said, striking an attitude. "I cannot, shall not, surrender to the Jed. I cannot give up those who have become my comrades, I cannot leave this far time to groan under his tyranny. I shall fight him, if necessary, single handed."

At this late date, I blush to record this bombast, so foreign to my timid nature, but I doubtless had fallen a victim at the time of a species of auto-hypnosis, and—the spell of bright, approving eyes. For, in spite of Eona's concern, I detected a gleam of admiration. And that would have been sufficient to have changed a rabbit into a raging lion.

But even as I spoke, I was afraid, desperately so. Already I heard in my heated imagination the stealthy approach of the guard. And so I changed my tune abruptly. "However, I must hide from them. Is there no place?"

The Mother shook her head vehemently. "There is a passage which leads down to the bottom of the tower. But what good is it? The Jed can read your thoughts wherever you are, and so compel you to disclose your hiding place."

Then it came upon me in a blinding flash. I struck myself on the forehead.

"Fool, stupid fool that I am. No wonder Sid always insisted I was not quite bright. To think that I almost let myself be taken in by a clever dodge."

Eona stared at me uncomprehendingly. "I do not understand you, but I know that if you do not hurry to do something soon, it will be too lute."

"Not at all," I said calmly, unhurriedly, masking the intense quivering relief within. Then I explained. "You see I had completely forgotten until your chance remark that I was wearing this." I tapped the thin gold circlet on my head. In a few words I explained its function. "So you see," I continued, "the Jed couldn't possibly know where I am by reading my thoughts.

"But I have to hand it to him for infernal cleverness. He knew I was about, that the thoughts he willed could reach me. The vibrations of his mind having a different frequency from the tuned blanketing of the thought-shield, have no difficulty in penetrating the protecting radiations. He tried to scare me into giving myself up, and I must admit, he almost did. That was why he pretended to have become suddenly afflicted with a strain of mercy."

I shook my fist vaguely. "You are clever, Jed, but I, Ned Dunn, am just a bit too much for you."

VAINGLORY goeth before a fall. Hardly had I uttered this silliness, when the sound of many feet outside in the rotunda brought me to my senses.