RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

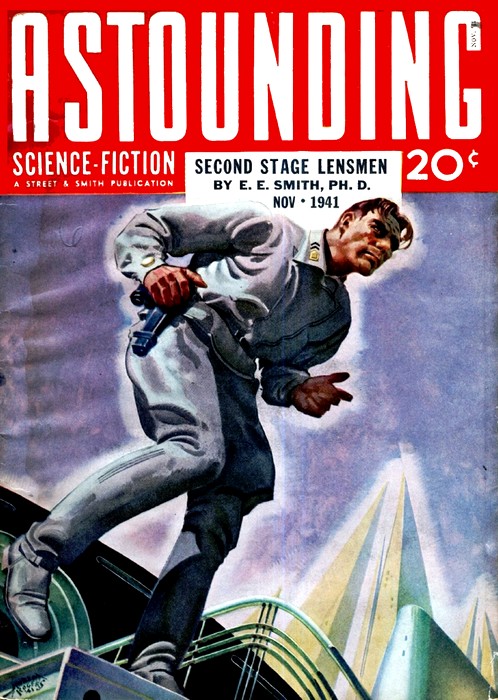

Astounding Science Fiction, November 1941,

with "Beyond All Weapons"

An absolute dictator with absolutely all weapons, can

be defeated only by a being who is—beyond all weapons!

WHEN the knocking on the door came I was prepared for it. For more than two months I had been steeling myself against just what was going to happen. In a way, I even welcomed the sound of it. It was finality—or just the beginning. The way I felt just then it didn't matter much any more either way. It's no easy thing lying half awake each night, in that dreadful in-between state that is neither sleep nor clarity, scheming, planning, nerving oneself against the inevitable knock that must come and yet unaccountably did not come, and getting up in the morning to find oneself drenched with sweat and so exhausted to present a cheerful face to one's wife and child.

The knocking increased. It was peremptory, authoritative, battering in its impatience.

"Damn them!" I thought bitterly. "Can't they wait a moment? They'll be waking Helen and the baby if they keep up that infernal racket. If only I can slip away, quietly."

It was the thought of these two that made me shiver suddenly, though it was a warm June night and the big lucite window was wide open behind the mesh of insect-killing current. I wanted to spare them; especially Helen. The baby was barely ten months old. I had a sealed letter all prepared, next my bed in a secret compartment of my night table. I hated partings. I hated tears—especially when they appeared in Helen's eyes. They made me all soft inside, and then I mightn't be able to go through with what I had to do.

Swiftly, yet quietly, I jerked my feet out of bed, pressed the tiny, fluorescent glow that spotted my clothes. Every night I had placed them into position so that I could pour into them in minimum time.

The knocking increased.

I pressed another button. It illuminated a small oblong on the outside door for the benefit of impatient visitors. "Wait, please!" it read. "I am coming."

But these were no ordinary visitors, and it was too much to expect them to understand and be gentlemen. The members of the dreaded Deseco were not picked for their gentlemanly qualities.

I swore softly, snatched the sealed letter from its compartment, inserted it under Helen's pillow, raced feverishly into my clothes. Tie still awry, I hesitated a moment. Within the small circle of illumination, Helen's face etched itself into my memory. For all I knew I might never see her again. The chances were all against it.

She was still asleep, thank God! The knocking had Ceased. In the silence I could hear her regular breathing, note the warm texture of her face, the long, silken lashes that. I loved locked tight in peaceful slumber. One bare arm was thrown carelessly across the thin coverlet, as if seeking my presence next her. In the next room, asleep under the sheet in his specially built crib, was the baby. John, Jr. Jacky! I felt an almost irresistible desire to tiptoe in and take a final look. I restrained myself. There was no time. The Deseco was not used to waiting.

I took a deep breath. My eye moved rapidly around the room, to imprint on my mind every slightest detail. It took in the open window. For a single moment my resolution wavered. If I should dart suddenly through; slither through the shrubbery, and—

I laughed bitterly, silently. The Deseco. were not fools. The house was watched on all sides. Out there, in the garden, lurked agents, waiting to shoot me down—with night cameras. Shot while attempting to escape—with pictures to prove it. It had been done before. I moved soft-soled toward the outer door.

"John! John Martin!"

I whirled.

Helen was out of bed, a night-robe thrust over her slim form, her eyes broken with anguish.

"Helen!" I exclaimed. "I thought you were asleep."

"I pretended," she sobbed. "I tried to be brave; not to make it more difficult for you." She came to me, and my arms went hungrily around her. "But I couldn't, my dear. They... they have come for you?"

I kissed her, not trusting myself to speak. I tried to tear myself away. But she clung to me, and her cheek was wet against mine. "He had no right," she sobbed, "the Master had no right to get you into this."

"The Master is always right," I said sternly. "Hush, darling' ! And please let me go. They won't wait—"

AS if in answer a thin red line ran rapidly around the resistant medium of the door. There was a faint, sparking sound; then the door fell neatly inward, making a dull, metallic sound on the fibroid flooring. Three men stepped inside. Two were similarly attired in green uniforms with thin-lined circles of red on their sleeves to denote their status as Circle Guards. Their faces were wooden and blank of all expression, and their stiffly outthrust hands held the new vicious little short-wave guns.

The third man, slightly to the fore, was in civilian attire. His face was bland and smooth and his eyes had a kind, even merry look. A man to be passed over in a crowd, a man such as might be found in any office, stratosphere liner, moving walk or nodding with a satisfied air over a, foam-capped beaker of rich, Polarian beer.

But I knew better. I knew him for what he was—a member of the Deseco—abrupt abbreviation for Department of Secret Co-ordination. I myself was about to be coordinated.

"John Martin," he said.

"Yes," I answered, pretending surprise. "Why does the Deseco break into my house like this? What have I done?"

I could feel Helen's trembling against me.

I must say this for him—the agent was courteous. They always were courteous, damn them! It was one of their rules—to be courteous in public. It cost them nothing and made a good impression on people. How could such kind-looking, soft-spoken people be guilty of the nameless crimes that were surreptitiously charged to them? They must be the malicious tales of agitators, such as our dear Director has always warned us about. It would serve such scandal-mongers right if we reported them.

Our dear Director! When you look into his eyes on the stereo-screen, as indeed is inevitable when you come to the assemblage halls every Sunday at ten in the morning in accordance with the summons, you get such a warm feeling about him. His eyes are so lustrous and full of infinite kindness that they send prickles of contentment up and down your spine. I swear to you, George, and to you, Adolph, that he looked directly at me all the time he was speaking. What? He was looking at you, George? What nonsense! As for you, Adolph, you always were rather vain. I tell you both he directed his words at me, and me alone! I can hardly wait for next Sunday. And please, Adolph, and please, George, don't get delusions about yourselves hereafter.

"The Deseco," said the agent courteously, addressing his remarks to my wife, "regret they were forced to use the cutting flame on the door. But there was a delay in opening. I shall suggest in my report that a new door be installed for you, madame." He bowed. "As for you, John Martin"—he turned to me—"I regret exceedingly I cannot answer your question. You will please come along."

I had no choice. Those frozen Circle Guards had me covered; and outside there were more of them lurking in the shadows.

I said: "Very well, sir." And kissed my wife. Her lips strained against mine. I whispered to her: "There's a letter under your pillow. It tells you what to do, in case—"

Her eyes dilated, yet she nodded bravely. She understood. In case I never came back, I had meant, and left unuttered. Men who were arrested by the Deseco very rarely came back.

She was a brave girl. We both had known when we decided to follow the Master that things might turn out this way. We had agreed, nevertheless, after a long searching and discussion of possibilities, to take the grim chance. We owed it to ourselves as human beings; to little Jacky, sleeping peacefully in his crib with the innocence of the newborn. If life under the Director was intolerable for us, who at least had known something of the blessed preceding years of freedom, what would it prove for him?

It was the thought of Jacky growing up in that stilling, hypnotic climate, perhaps even yielding his mentality and assent to the constant, skillful hypnosis, that had decided us when news of the incredible Master had drifted to us on the surreptitious wings of furtive side whisperings. I had brought the tidings to Helen, and we had decided. Even now I wasn't sorry, with the great test confronting me.

"Well?" said the agent impatiently.

"I'm coming," I answered quietly. Another hurried embrace and I gently disengaged myself from Helen's frozen form. My last sight of her was one of fierce-held immobility, her dark eyes wide on me with repressed anguish; then we were out in the warm, June breeze and I was thrust into a swift aerocar, armed with impenetrable vibrations.

The agent dropped into the seat next to me. The two Circle Guards entered behind, their guns watchful. A pressure of the foot and the cat-soared swiftly and swooped eastward.

"Where are we going?" I asked.

"It is not my business to answer you," he said seriously, "but I shall tell you. We are going to our great Director himself."

With automatic precision his left hand came up and pressed hard against his heart—or what passed for a heart, among the Deseco.

"Live the Director!"

Behind me I heard the swift similar slapping of hands on hearts, and the simultaneous cry: "Live the Director!"

Then silence again and the soft rush of the aerocar.

IT should have sounded funny, but it wasn't. Nothing connected with the Director could be considered funny. And I was too stunned by the information to think of anything else.

Evidently I was an unusual ease. Ordinary victims of the Deseco—once numbered by the thousands, but now reduced to a mere trickle as the hypnosis spread—were usually whisked to Deseco quarters, where nameless things happened of which only mere wisps of rumors filtered through. Hardly ever did one return; and when he did, he never spoke—not even to wife, to father or to son. But the Director was as one aloof, apart. Torture was a thing remote, and the bloody cries of groveling men. He sighed when he spoke of the Deseco—which was not often; some there still were who had failed to see the light. They were sick, perhaps; deluded, certainly. The Deseco chided and admonished, as a father would; they operated, as a surgeon would. But soon there would be no need—

My wits returned, and my brain churned furiously. I hadn't expected this. In my wildest dreams I hadn't figured on reaching the Director in person. The most approachable of men, seemingly; in fact, no one, not even his closest advisers, ever came to physical closeness. Always there was an impenetrable screen between—one that permitted sight and sound to pass with utmost readiness, yet forbade all other contacts.

I had expected, in my preparations, to be taken before the grim officials of the Deseco. I had planned each move in detail, as I would a board of chessmen. There had always been the chance that some violent sweep would send my pawns and castles tumbling into ruin, but I had been ready to face that chance.

Now, by some freak, my plans were ruined. Why had the Director sent for me? Did that mean that he was afraid? Or merely curious? Would my end come swiftly? Or with lingering, long-drawn suffering?

I tried to think things out. Through the slight vibration shimmer I stared out and down at the sliding city. Within the car was silence. The agent had regretted his momentary burst of loquaciousness, and sat frowning at my side. Behind me the immobile Guards never wavered in their aim, alert for any sign of break. Not that there was anything I could do. The car was hermetically sealed; our flight skimmed the towers of Megalon by a good five hundred feet.

It was a beautiful night. I drank it in with the greedy gulps of a man who knows that he might never drink again. The city lay bathed in a glow of lapping fluorescent light. The towers pierced the glow like phosphorescent needles, clothed in counter-currents of shimmering color. Wide boulevards radiated to suburban peripheries from the central mass of the generating plant. Parks, museums, big amphitheaters and libraries clustered in the center. Then came the glass and steel upflings of the living quarters; and beyond, on the circumference, the silent miles of the technical plants.

Libraries! Museums! Broadcasters! Amphitheaters! All the elaborate apparatus for the mind; for wisdom and learning. But what books could now be read? What televised programs seen and heard? What art remained in the museums? What speaking, breathing pageants in the huge, receding tiers?

There had been no purge, no spectacular burnings of books and paintings. Oh, no! Nothing as crude and vulgar as that. Earlier, more primitive dictators might heap bonfires and declaim in ranting tones. Not the Director! There was reorganization. That was the word! Nothing was prohibited; but things disappeared. Quietly; without fuss or comment. Books that once were classics.

History—Gibbon and Beard and James Harvey Robinson; philosophy—Spinoza and Dewey and Locke; drama—Shakespeare, why, I didn't know, and Shaw and O'Neill; economics—Adam Smith and Sumner; novels went out en masse—one could never tell what passage in Dickens or Hugo or Thomas Mann might excite vestigial longings.

It wasn't that the shelves of the libraries or the plays for the stage were empty.

Not at all! Plato and Hobbes and Aristotle and Pareto remained. Hegel, too, and the later Burke and the later Wordsworth. All who preached absolutism and a rigid discipline. And the gaps were filled with a rush of new yes-sayers, self-deluded converts and plain lick-spittles. I, who had been brought up on the iconoclasts and the seekers after truth, felt violent disgust every time I picked up a volume with the deadly monotonous red circle emblazoned on the cover in token of official approval.

The city fled behind, and the machine suburbs. Rolling park land succeeded, stocked with ever-new mutation-contrived species of plant and animal. Then, in the distance, high on a mountaintop, the severe straight lines of the aerie of the Director.

Nothing elaborate; nothing ornate. The Director was too smart to go in for lavish ostentation. People commented approvingly on his Spartan tastes, his eschewing of all luxury. They didn't realize that the exercise of power, the prompt obedience of an entire planet, made all other embodiments of sybaritism pale to nothingness in the nostrils of men like the Director.

WE circled three times overhead, giving each time a code recognition signal, while search rays sought out our innermost vitals and a concealed armament stood ready to blast us out of existence in case we didn't pass the tests.

At length suspicion died. The protective screen that had forced us into automatic circling opened slightly, and we slid down a narrow tunnel of vibrations to a landing stage where our seals were opened and grim, silent men in neutral gray took us over without a word.

The agent who had arrested me gulped, started to say something and changed his mind. There was something in the atmosphere that forbade words. Even to an agent of the Deseco.

He slid back into the aerocar, two badly frightened Circle Guards with him; the seals were set and he soared away. The screen parted briefly, closed again; and he was gone.

I was left alone—in the hands of the super-dreaded, legendary Pretorians—the personal men of the Director!

Not a word was spoken. The Pretoria's were not given to useless chatter. They were more like automatons than men. The will of the Director was their will; his life their life. Hypnosis could go no further.

The interior of the mountain retreat of the Director was a vast, honeycombed fortress. Swift-moving corridors, sudden upsurging platforms and down-dropping reversals, photoscanners and vibration screens, and Pretorians everywhere—silent, efficient, permitting our passage only on proper signal.

At last I was thrust into a chamber of flooding light, where my eyes blinked and blinded under a swirl of search rays. My skin prickled under the heating waves. I felt horribly naked and alone, as indeed I was. The rays probed like questing fingers, penetrating even the frail flesh and the convolutions of the brain to pluck out whatever secrets I might possess. Gasping and shuddering like a swimmer under overwhelming waves, I nevertheless maintained sufficient control to hold myself rigid against the light hypnosis. I mustn't give way, I said to myself and clenched my teeth. It was so easy to surrender, to allow one's mind to drift along the patterned surge, to open one's thoughts like petals to the kindly probings of the Director. That way lay warmth and the luxury of surrender. Every fiber of my being cried for surcease. Why must I continue to fight? Why not yield and regain blissful consciousness? After all, what did stubborn individualism bring one except angular cacophonies and harsh dissonances? It was so hard to be alone and breast the constant buffetings of the tide; so easy to feel the comforting mold of uniformity, to let the Director decide. He was all-wise; all-knowing; all—

I snapped my head with deliberate violence; so hard that I felt the neck muscles wrench and rebound like released rubber bands, I cried out with pain; but the sharpness of the spasm, the brutal agony I had inflicted upon myself cleared away the hypnotic mists, brought my mind back to wary awareness. I had won—momentarily.

As if the unseen watcher knew that the rays had failed to do their work, the probing light died suddenly away. I blinked. The dazzlement fled from my eyes. I could see again.

THE Director sat in front of me, observing me with thoughtful, inscrutable gaze. He sat behind a simple desk, in a room that was indistinguishable from a thousand offices in Megalon where modest executives plied their modest affairs. His dress was as simple and unornamented—an olive-green military blouse and strapped trousers of a similar hue. Only the two tiny golden circles on the collar differentiated him from the meanest soldier in his command.

The Director did not go in for ostentation or vulgar display.

For the moment a sudden surge leaped through me. He was alone, not ten feet away. How simple it would be to leap the intervening distance, to strangle him with bare hands, and rid the earth of him once and for all. It would be so easy. He was slight of frame and not very athletic. I towered over him by at least four inches and I had kept in trim with swimming, tennis and mountain climbing. Instinctively I flexed for the forward drive. It would be so easy.

Then I caught myself. I was a fool! I had forgotten. Between the Director, observing me quietly with candid-seeming eyes and a curious smile, and myself there was a barrier. A mesh of invisible vibrations, impervious to any force known to man, behind which he was as safe as though he had been three thousand miles away.

He said: "That is better, John Martin. Three steps closer and you would have been annihilated. Which would have been a pity."

He was telling the truth, conversationally, without heat or bluster or anger. Which made him all the more terrible. I felt a light perspiration break out all over me.

"Mr. Director," I said, forcing my voice to steadiness, "an agent of the Deseco broke into my home and brought me here. I have no knowledge of any wrongdoing."

Mr. Director! He had no other name. If he had, it had been lost in the mists that, surrounded his early origin. Since he had come to power there had been no other title.

"Wrongdoing?" he countered. His pale, ascetic face seemed almost kindly. "Did the agent say anything like that?"

"No, but—"

"If he did, he exceeded his orders. I asked you here from friendly motives."

I laughed bitterly to myself, but allowed no hint of it to show on my face.

He leaned forward a trifle. "You do not appear to be an ordinary man, John Martin," he said. "I have been taking a warm interest in your career. Hm-m-m!" He rattled off the facts of my life as if he were reading from a dossier in the files of the Deseco. "Born in 1995 of the Barbaric Era of a family of six—two brothers and four sisters. Father and mother now dead; two sisters dead; the brother killed in the Change. You made a name for yourself in the field of Psycho-History and taught at the University of Megalon. You suffered a bad accident while scaling Mount McKinley by a new and supposedly inaccessible ascent. You were laid up for more than a year. This was during the Change."

He drummed thoughtfully on the desk with his womanish fingers. "Thereby you avoided declaring yourself, as practically everyone else did. We did not bother then with hospital eases. We were, I must admit, not as efficient in our methods during the Change as we might have been. Your brother, however, did declare himself. He was stubborn and rooted in the Barbaric Era."

I said nothing. Not even a muscle twitched. Poor Bill! They had come for him and shot him—in front of his wife and Alice, our sister. Alice had snatched up a gun and been shot down in turn. Jane, his wife, had merely fainted. Two months later, she died, her mind mercifully darkened against the tragedy.

"When you recovered," pursued the Director, "you were permitted to retain your position at the University. You took the oath of the New Era; you've attended the weekly Assemblies and done everything that has been outwardly required of all good and loyal citizens. You married, and you have a child. Therein you have partially fulfilled your duties, though not sufficiently to meet with proper approval. Good citizens who have been married, as you have, for five years, should have had at least three young citizens for the State."

Still I said nothing. Helen and I had decided at first to bring no slaves into the world. But the forces of human nature and human instincts are sometimes too strong for austere determinations. Marriage without children is only partially complete.

The Director puckered his brow. "Your teaching was closely observed. Purely as a matter of routine, John Martin. There are reports from your president, from your colleagues, from students in your classes."

"Has there been any charge laid against me for false teachings?" I inquired. I knew I had not been brought here to answer any such charge. The Director wouldn't have bothered himself with any routine affair like that. There were other methods. And I had been very careful in class and in my private speech at the University. I was well aware of the honeycomb of espionage. But I thought it wiser to betray no awareness of the real reason for my arrest.

"No-o," he admitted. "Your teaching was correct; you followed the accepted syllabus concerning the Barbaric Era, the Change, and the New Era. Yet the reports show a certain doubt. Nothing to justify summary action. An insufficient enthusiasm, perhaps; a faint irony and shadings of the voice in the wrong places. But these were subjective qualities. The reporters might have erred through excess of natural zeal. At least until a month ago."

I stiffened. Here it was coming. "I am not aware of any change then," I said carefully.

His smile was suddenly no longer pleasant. "It will do you no good to pretend, John Martin," he said harshly. "You are not as stupid as the other dupes. The others have spoken. All who have been brought before me. They yielded readily to the light treatment. They opened their minds and their thoughts. They told me everything they knew." His fingers made loud sounds on the desk. "But you have resisted. You closed yourself. You lead me to suspect that you have sat through the Assemblies in similar stubborn resistance. You pretended submission when secretly you were rebellious. You know, of course, what happens to men who are stubborn."

"I have seen specimens of your handiwork," I admitted.

He glanced at me sharply, but my face betrayed nothing.

"Then think well before you persist." His words jerked out at me. "Who is this man who calls himself the Master? Where is he now? Tell me?"

I HAD been thinking well and swiftly all during this strange interview. My plans had been upset by my failure to be taken before the Deseco. I had to shift them suddenly, and quickly, to meet this unexpected situation. I had known for some time that others had been arrested; but I hadn't known they had been taken to the Director. None of them had returned.

I denied nothing. All I said was: "It didn't help the others any that they spoke."

He smiled. He was close to victory. "You needn't fear about that, John Martin. If you speak well and truly, you shall go free. I shall realize that you were misled by a cunning scoundrel and impostor. Why, we shall permit you to retain your position at the University. Perhaps, if you show the proper frame of mind, you might even find a Rectorship open."

So the Director was offering me a bribe? The Rectorship! There were only six of these in the world. Rulers of the educational systems; one for each continent. Wielders of vast powers under him.

That meant two things. First, that the Director was seriously perturbed. The unknown presence of the Master was an irritant. The secret propaganda was effective then; more effective than he would be prepared to admit. I had been wondering about that. There had been so little chance of finding out. Second, that the other disciples whom he had captured had been able to disclose practically nothing. But then, how could they have told much, even if they had wished? I took a deep breath and decided on my proper course.

"Let's get down to brass tacks," I said boldly. "The others told you nothing, because they knew nothing. The Master knows whom to trust. He is beyond your vengeance or the vengeance of the Deseco. He laughs at your puny hypnotic powers, based as they are on ordinary, everyday scientific principles."

The Director's eyes were dangerous. But I plunged on recklessly. "Yes, mass hypnotism—that has been your secret weapon. You may have deluded most of the world, but you forget I studied psycho-history in what you are pleased to call the Barbaric Era. Earlier dictators than you fumbled around with the idea of mass hypnosis. There was a man named Hitler back in the 1930s and '40s who used it with some crude success. But he didn't know anything about the scientific end of it. He employed no hypnosis rays or skillful projections to break into the unconscious and the subliminal thresholds. He relied on a raucous voice and emotional reiterations. You have been far cleverer. Your Sunday Assemblies renew your contacts with all the earth, re-bathing the poor dupes in hypnosis rays and sliding afresh the projectional suggestions of your voice and mind into theirs."

For a moment I stood silent then, rather aghast at myself. Had I overplayed my hand? Had I, by my provocative boldness, brought the Director to such a pitch of rage that he would annihilate me where I stood? That he had the necessary weapons within range of those tight, white-knuckled fingers I had no doubt. And his face betrayed, through its swift suffusion, just such a murderous impulse.

But I hadn't overrated him. He was at least as clever and as brilliant in improvisations as I had given him credit for. He had to be. Otherwise he couldn't have attained the heights he had. Hie was no fanatical madman, as some of the earlier local dictators had been; and even they, in their madness, had perforce shown flashes of genius. He had learned from their mistakes and eventual defeats; he had evolved a new and highly intellectualized technique.

But I don't mind saying that I felt considerably relieved when be suddenly relaxed and even smiled. It's one thing to work out a theoretical analysis of a given. psychological situation; and another to have it work in practice. Especially when failure meant torture and violent death.

"John Martin," he said approvingly, "you are a brave man and you have a stubborn mind. You never, in fact, yielded to the hypnosis?"

"No."

"And you admit that you know the identity of this charlatan called the Master, though the others did not?"

"Yes."

He leaned back in his chair and smiled with a benevolence I did not trust.

"Good!" he said. "We understand each other. I need make no pretenses to you. This so-called Master is trying to stir up trouble. Not that he can really do anything. All that it amounts to is a lot of whispering and rumor mongering. Here and there some weak-minded individual might succumb; and then I'd regretfully have to dispense with him. The Earth I planned has no place for doubters and malcontents."

"No," I said.

A shade of suspicion crossed his face; vanished. "Exactly. It's really his poor dupes I'm thinking of. Otherwise I wouldn't pay the slightest attention to the whole thing. It's ridiculous—this nonsense about a superman; a Master from another planet. No reasonable man would think twice about such a stupid charlatan. But it pains me to have to eliminate those whom he has enmeshed with his lying promises. Therefore I wish to get rid of him once and for all."

"I don't doubt it," I said.

Again suspicion flitted over his countenance. Perhaps he detected a certain delicate irony in my agreements.

"You are the only one who knows his true identity?"

"I wouldn't say that," I replied carefully. "There may be others. Very likely there are. I don't know. And as to his true identity—that also is hard to say about someone who is obviously not a human Earthman."

THE Director controlled himself. My respect for him grew. He did not yield easily to clouding emotions and was, therefore, all the more dangerous. He even essayed an indulgent laugh.

"Come now, John Martin"—he smiled—"surely you don't expect me to believe this poppycock about a man from Saturn come to Earth with superhuman powers to set things right. And I know you're too intelligent to believe it, either. That may be all right for the common herd, but not for us. Confess the truth. He's an ordinary human being—some scientist, perhaps, who managed to escape the Change—who thinks he's clever enough to overthrow me with such silly nonsense. Any fakir, with a little simple apparatus, can manage to impress a certain number of the feebleminded. But as for overcoming me—"

"You're wrong, Mr. Director," I told him earnestly. "You're terribly wrong. As you say, I'm not one to be taken in easily. But I've seen the Master. I've seen him more than once. And I believe. It is impossible not to believe, once you have met him face to face. He is not of this Earth. Whether he actually came from Saturn, or from another planet, I have only his word. But that he came from another world, is without question. I have seen him do things—"

I checked myself. I was saying too much.

The Director looked eager. "What, for example?"

"I cannot tell you," I answered doggedly. "It is not my secret to divulge. Besides, he has promised to divulge himself openly."

"Ah! And when is that great day?"

"On the Fourth of July." I had no qualms about mentioning the date. It had been bruited about in whispers. The Director must have known about it. The Deseco, as I think I've already remarked, are pretty efficient.

In fact, he didn't seem at all surprised. He grinned; but I thought I detected a faint shade of anxiety under the grin. "The Fourth of July, eh? What a coincidence! A man from Saturn utilizing a date like that—all men are created free and equal—bah!" He wrinkled his nose in disgust. "Confess now. Doesn't that alone show his human origin?"

I shook my head. "Not at all. He knows human history better than I do; and I'm supposed to be something of a specialist in it. He told me things that had happened; for example—But, well, never mind. The point is he's going to take over the Earth on that day. He's going to take it over no matter what precautions are made against him; no matter what weapons are employed to defend your power. And once he has taken it, he intends to liberate mankind; free them from dictatorship and tyranny. On Saturn, he says, those things went out many thousands and millions of years ago."

"And, of course," sneered the Director, "I'll stand by idly and watch him do it."

"You won't," I said. "But it won't matter what you do. You'll be dead."

A spasm must have run through him; but I couldn't note a sign. Whatever his faults, the Director was no coward.

He tapped the desk thoughtfully. "Well, well! And why should this superman wait until the Fourth of July? Why not act at once?"

I had thought of that myself. "I don't know," I admitted. "One just doesn't ask questions of the Master. One—"

The Director nodded. "With all your intelligence, John Martin," he told me, "that represents the difference between you and me. I'm not afraid to ask questions; to penetrate mumbo jumbos. Tell me where to find him, and I'll ask him plenty of questions."

"I'm sorry I can't tell you that."

He frowned. "You know and you won't tell?"

I hesitated a fraction of an instant. "I didn't mean that," I then said hastily. "I... I don't know. Whenever he wants me, he comes to me—unexpectedly. I never know when it's going to happen."

"You lie, John Martin. You know his hide-out."

"I've told you the truth." I tried to put the ring of sincerity in the denial, but I could see I didn't convince him.

"Would torture help your memory?" he suggested softly.

I checked a certain shivering. I looked him straight in the face. "It would not," I declared.

"I didn't think it would," he admitted. I know your breed. You'd go to your death without a quiver. But suppose your wife—" My inner ague increased. I had been dreading that possibility. The Director would stop at nothing to waylay the Master. I had an agonized mental picture of Helen in the grip of the Deseco. Yet I managed calmly: "That wouldn't help, either, Mr. Director. Nor could the torture wrest it from her. She doesn't know where he is."

"I know she doesn't," he agreed unexpectedly.

I showed surprise. "You know that?" I cried.

"You're really not as intelligent as you think yourself," he said with a sarcastic smile. "You're not much of a conspirator, leaving notes around for your wife. I can't think much of your Master if he has to rely upon such tools as you."

"But... but—" I spluttered. "The Deseco never does a botched job. There was more than one agent. When you left, under guard, the others watcher! through their spy instruments. They saw your wife take the letter from under the pillow. They broke in immediately and took it away from her."

I said "Damn!" fervently. Luckily the note contained nothing really incriminating, In fact, I remembered I had written something to the effect that now I was caught, I was willing to admit that I should have taken her advice and had no dealing with the Master. I asked her forgiveness for the trouble I had brought upon her and to forget me as well as a being she had never seen or really believed in.

I straightened. "That note," I said harshly, "was designed to make my wife feel better. Whatever I had done I had done against her pleadings. But don't think it states the truth, I'm not sorry, nor will I ever be, no matter what happens. Even if I die today, and my whole family succumbs to your gentle ministrations, it won't make the slightest difference. On July 4th the Master takes over; and you will die."

A FAINT line creased his brows; smoothed out. He considered me, standing there flushed and defiant. I would have given anything to have been able to read what was going on behind that smooth facade. My life hung precariously in the balance. The lives of Helen and Jacky. More than that, even.

There was a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. Had I gambled and lost? Had I misread the super-clever mentality of the Director? Would the co-ordinates of my carefully plotted fight for life go crashing?

The moments moved on in interminable array. They turned into minutes, and the minutes into hours. Time blurred and stood still. The palms of my hands sweated; I had been holding my breath for uncounted days. The silence was insupportable.

Then the words of the Director, soft though they were in fact, crashed like resounding thunder about my ears. I tried desperately to clear them, to bring them from a noisy jumble to ordered meaning.

"You are a sick man," he was saying with a half-regretful sigh. "I should turn you over to the Deseco for proper... ah... manipulation. But I won't."

I dared not try to fathom what he intended. Perhaps he was playing with me as a cat with a mouse. I held my breath.

He shook his head. "No, John Martin. I have decided. Your Master is harmless. So are you. You are flies buzzing on the flanks of a mountain. I shall no longer compromise my dignity by paying the slightest attention to either of you. You are free, John Martin."

A sweat broke out all over me. I didn't believe it. He was still playing with me; lifting me into hope so that he could dash me down from a greater height.

"You mean I am free to... to go?" I gasped.

His smile was cordial. "Without any strings or limitations. You may even return to the University. That should give you an idea of my apprehensions concerning your mountebank man from Saturn or his vain threat about the Fourth of July."

He pressed a button. As if by magic a Pretorian appeared at my side. The Director's smile was broad, carefree.

"Take John Martin back to Megalon," he said gently. "And turn him loose. I shall hold you responsible for any harm that may come to him on the way."

The Pretorian saluted, hand slapping smartly against his chest. "Live the Director!" Then his face froze into a mask again.

"Well, what are you waiting for?" demanded the Director of me. "Have you lost your wits?"

I was indeed as one bereft of sense. My knees trembled. It was still difficult to believe. I had gambled, and I had won—so far, at any rate. I had pitted my psychologic analysis against torture and death, and fact had followed theory. The Director was a very clever man. Had he been less clever—or more clever—I would be now on my way to the private chambers of the Deseco; not to freedom.

I found my voice and tried to keep it steady. "You are kind, Mr. Director."

"Kind?" He dismissed it with contemptuous gesture. "Not at all. Indifferent, rather. Indifferent to the blustering of charlatans. On the Fourth of July, John Martin, I shall go fishing."

He disappeared suddenly. The intervening vibrations solidified into a wall. It was an effective gesture of dismissal.

The Pretorian said: "Come!"

They wasted no words.

I WENT along, my brain a seething caldron of thoughts and emotions. I had faced death and been reprieved. Yet suspicion still lurked and held my breath to shallow, gusty drafts until the night air greeted us again and we had taken off—the Pretorian and I—in a fast aerocar.

Even then, it was only when I saw the eternal glow of Megalon lifting over the horizon that I felt I. was in fact temporarily free. For the first time the bands about my heart and chest loosened, and the blood began to circulate properly again.

I began to plan, fiercely, rapidly. I had won the first round: but there would be others.

The Pretorian cleared his throat. It had an unusual, hesitating sound. It was the third time he bad cleared it thus. In my preoccupation I had not given it the proper attention before.

I looked at him in surprise.

There was a curiously anxious expression on his face. As though he wanted to speak, and was fumbling for words. It was very strange. He seemed suddenly human; not a Pretorian at all.

"Yes?" I said.

He took courage from that. "Is... is it true you have seen this being they call the Master?"

"Yes."

"Is he... is he really as superhuman as they claim he is?"

"Yes," I said.

There is an art in monosyllables. The Pretorian looked hastily at the spy unit in the rushing aerocar. It was closed. Nevertheless he sidled closer to me on the seat; whispered.

"You are the first man I have met who has actually seen him. We were talking about it on guard last night. My comrade claims to know a man who knows someone else who has seen the Master. Is it true he is a hundred feet tall and can kill just by looking at you?"

"I am sorry," I said carefully. "I am not allowed to say."

The Pretorian nodded, as if he understood how it was. He considered another moment.

"What's going to happen on the fourth of next month?"

"I don't know."

"But they say—"

"They say lots of things. The Master didn't tell me. I am only a human; not one of his own kind. I only hope it isn't going to be too terrible."

Air exhaled from the Pretorian's chest. A pallor came upon his face. He didn't say anything more the rest of the journey.

Except as we landed, and before the seal closed on him again, he thrust his head out suddenly. "Does he know who believes in him and who doesn't?"

"I don't know," I told him honestly. "Thoughts are secret things; but actions are not."

"Ah-h-h!" he said. And I left him there while I hurried to the house to meet those whom I had never thought to meet again.

Dawn was just breaking and the house was enveloped in a mantle of filigree mist. In the distance Megalon glowed like a great jewel and the sun made a red ribbon of fire along the still-dark mountains from which I had just returned.

But the house was dark and silent, and I suffered a thousand deaths before the scanner approved of me and let me in.

"Helen!" I cried into the dark. "I'm back! Helen!"

I heard the muffled sound of sobbing; then a quick swish of fabric and an incredulous voice: "John! Is it... can it—"

"It is—and it can," I cried as lightly as I could with my throat tight and dry. "I've returned. See, didn't I tell you?"

The light went on with a rush, and Helen was straining to me as though she wished to interpenetrate my being.

"It's all right," I said, patting her head. "So far, at any rate. Things worked out even better than I had dared hope."

Arm tight around her, I went in to see Jacky. In the misty half light he stirred, blinked and returned to his dreams. We kissed him and went back to the main chamber. Helen was breathless with questions. I told her what was fit for her to know. It was far better, I had determined at the beginning of this complicated business, that she did not know too much.

"But I don't understand," she said with a mixture of flooding relief and utter bewilderment. "The Director himself! And he permitted you to go?"

"The Director is a very clever man," I said softly. "I am just a tool, a worthless creature. It's the Master he wants. He pretended to mock; but he's scared. I could see it in every move he made; in the very lack of fear he was careful to display. Suppose he killed me. That wouldn't bring him a step closer to the elimination of the real danger."

"The Master?"

"Yes. In his mind there's a conflict raging. His reason tells him the Master's some Earthman, pretending to superhuman powers. But his imagination is uneasy. Suppose a Saturnian had come to Earth? Like a prudent man the Director is determined, no matter how, to get rid of this possible menace. He's got his spies and the Deseco searching every cranny in the world. And the search has failed. That frightens him just a little more. The Fourth of July is less than a month away. The Deseco reports a growing uneasiness among the people, especially around Megalon. And the rumors are spreading. Fast, the way all rumors spread. He must scotch the thing at once; otherwise there's no telling what might happen. And the way to scotch it is to produce the Master—a chained prisoner."

"But you, darling! What is your place in this?"

I laughed grimly. "I'm the decoy. He knows I've seen the Master. He expects me to meet him again. I'm to lead the Deseco to the head and front of the agitation. Even now agents are lurking outside. In a moment or two their spy instruments are going to be set up. When that happens, dear, we talk trivialities; and keep on talking them."

Helen was icy cold. Her face was drawn with fear. "John, darling, you mustn't go in with this. Let the Master find other men to help him. I couldn't stand another night like this one. If he's so powerful, he can free the Earth without your help or anyone else's."

"God helps those who help themselves!" I said laconically. And, without transition, I went gayly on. "I'm tired, sweet. Let's get to bed. I want to get up early tomorrow morning. I want to see President Gorham of the University to arrange for a leave of absence. Would you believe it, darling, that I fooled the Director completely? He thinks the Master comes to me. As if the Master would deign do such a thing! I'm going to him."

Helen looked at me frozen-eyed. Words quivered on her lips. I squeezed them off with sudden pressure on her arm and a significant side glance at the tiny detector I had installed inside the timepiece on the wall. The minute hand was glowing a faint red. Only one who was looking for it could note the shift in color.

My wife is all right! Desperate as was her fear and wonder, she understood. The detector had picked up the vibrations of spy instruments. We were under surveillance. "I wish you'd not talk that way," she said with just the right troubled note in her voice. "You ought to be thankful to our great Director for giving you a second chance. I hate your Master, whoever he is. Don't have anything more to do with him."

"Keep your nose out of my affairs," I said roughly. "You're as bad as the other stupid fools who kowtow to the Director. In less than a month everyone who doesn't believe will be dead. The Master himself has said so. Now get to bed."

I turned out the light.

Everything was working swell!

PRESIDENT VIRGIL GORHAM, of the University, expressed no surprise at my request for an indefinite leave of absence. I wanted to make some investigations necessitating the use of manuscript material scattered all over the world, I told him. In fact, he was effusive in his desire to accede to my request. I could start at once, he declared. Nothing must stand in the way of such a laudable bit of research.

I kept a straight face. I knew that the agents of the Deseco had already been to see him. No obstacle was to be placed in my path. I was the decoy, the stool pigeon, who was to lead them to the Master.

On the way home, a young instructor in biology fell in step with me. We spoke of inconsequential things as we crossed the campus. There were students swarming all over the place. But instead of quitting me at the edge of the field he kept on walking alongside. He was a nice young fellow and, as I had had occasion to find out, somewhat cautiously liberal in his tone. I had even seen him stifle a bored yawn during one of the compulsory Sunday Assemblies.

We came to an open stretch of park. It was deserted. Young Kent came closer to me. "Say, Martin," he said casually, "have you been hearing all this nonsense about a man from Saturn?"

"A little," I said noncommittally.

He thrust me a swift side glance; then stared directly ahead. "It's a lot of nonsense, isn't it?"

"Maybe yes; maybe no," I said.

"Hm-m-m! I agree with you. I mean—it's hard to believe there's even life on Saturn; much less a super-race who could send a representative to interfere in Earth's affairs."

I kept silence.

"Hm-m-m!" He thrust me that quick look again. He seemed baffled; yet he was brimming over. I knew he'd say more.

"Funny thing, though," he added.

"What is?"

"Of course it's nonsense, but I met a man yesterday who claimed to have seen the Master with his own eves."

"Who?"

"Well, it was Giles." Giles was the man-of-all-work in the biology labs. He had the strength of three men, but he wasn't very bright.

"Yes." Kent seemed a bit resentful. "Curious that a superman like the Master should choose to reveal himself to a fellow like Giles."

"A Saturnian may have different standards from ours," I pointed out. "But was Giles sure he saw him?"

"Absolutely. He was bubbling with it; had to tell someone. I suppose he thought I was safe. Asked me particularly not to mention if to a soul; didn't want the Deseco to pounce on him."

I refrained from what would have been an obvious remark.

"Yes, sir, Giles saw him yesterday evening, down near the river," Kent went on. "The Master just materialized out of thin air, he claims." The young instructor laughed indulgently. "Of course, Giles is the kind of chap that would think that. Naturally, it must really be a type of space travel; the type the Saturnian used to get to Earth."

"Naturally," I echoed.

"Anyway, Giles said you could tell he wasn't from Earth. He was twice as tall as a man and his clothes were a shining, flexible metal. They had quite a conversation. According to Giles, the Master had decided to wait until next month before using his super-weapon, so as to give people a chance to show by their actions that they didn't want the Director themselves. He explained the weapon to Giles, but of course Giles wouldn't retain much of the explanation. Something about its being selective. It kills all those whose minds show they aren't fit for freedom; and—"

Kent broke off hurriedly. He looked at me. It was evident he thought he had said too much. He essayed an uncertain laugh. "Naturally it's all poppycock. Even if there were such a man from Saturn, he'll never be able to overthrow our noble Director."

"Well," I said judicially, "I don't know—"

We had come to the path that led to my house; and I turned in, leaving Kent gaping after me.

I felt satisfied inside. For, curiously enough, I had spoken to Giles only yesterday afternoon.

THE Deseco stuck to me like burs. Wherever I went, an inconspicuous agent trailed me. On the stratosphere liner to Great London, the waiter in Parisan, the polite hotel manager in Tomsk, the yellow man who jostled me in the streets of Sinopolis and muttered: "Sorry!"

Everywhere I went I was watched. Night and day. I didn't mind. I took sudden, unnecessary trips. Such as the one out into the Gobi. The swift run to Australia. The doubling back into the Congo and what was left of the old jungle. I wanted to see how efficient the Deseco was.

The Deseco was efficient. How they did it, I don't know. But a chubby tourist materialized in tire Australian bush. A lean Tatar rode an old-fashioned horse over the stony Gobi. A black man hired himself to me to tote my traveling bag in the Congo.

Yet I never led them to the Master. Every time I left some place in a hurry, they were sure this was the time. That trail's end was in sight I encouraged the belief. I looked behind me furtively, as if to spot possible shadowers; and never, of course, realized that the pretty woman who chatted and flirted with me was the one I should fear.

Oh, I had a swell time!

I covered the world. My aimless peregrinations had definite purpose. In most places I found that news of the Master had preceded me. I listened, and dropped hints. I sowed rumors. I had heard so and so from a man, I said. I described the man from Saturn in artful phrases. I spoke vaguely of the Fourth of July. I even told the pretty woman agent about it. She was eager to know more; if she, too, could meet the deliverer. I dodged her with clumsy evasions.

I attended the Sunday Assemblies wherever I happened to be, as was indeed compulsory. The Director, three-dimensional, spoke softly, soothingly. The hypnosis rays pervaded the auditoriums. His eyes were serene, and persuasive. The drugged words slid into the minds of the people.

But I noted something increasing as a June of Sundays moved to a close. A certain restlessness among the dupes. A stiffening of resistance to the hypnotic sway. A counter-irritant to what had enveloped them so long. Whisperings, in spite of the sudden appearance of the Circle Guards. Resentful faces when a too-loud whisperer was pounced upon and dragged away.

The rumors fled before me. Where they hadn't come as yet, they swelled behind me. Strange, the speed with which rumors travel. Sometimes I wonder if they aren't as fast as light. Certainly they move with a celerity exceeding that any stratosphere liner.

Down in Patagonia, as I stepped from the liner, I stepped simultaneously into an excited, gesticulating crowd. It was the first I had seen like that. Circle Guards were as excited as any ordinary citizen. Even the agent of the Deseco, designated to meet me as I got off, was as flushed and gesticulating as the rest. Don't ask me how I knew he was a Deseco agent. Call it an intuition based on a long background of psycho-historical study. Call it what you wish. But I rarely make a mistake in sizing up a man.

I pushed deliberately toward him. This was unusual. Neither Deseco nor Circle Guards ordinarily permitted excited mobs. Mobs set up a hypnosis of their own.

"What's going on?" I asked him.

He stared at me. His face was flushed and his breathing came in shallow bursts. There was a glitter in his eyes. To my trained glance it was evident that there had been a terrible wrench to his conscious ego—a wrench that had destroyed some deep-seated pattern which had hitherto filled his mind.

"Haven't you heard?" he cried.

"Heard what?"

"The Master... the Master's just come to Patagonia. I saw him with my own eyes." He flung around to the rapidly growing mob for confirmation. "Didn't I, friends?"

An excited clamor of agreement boiled around us.

"The Master?" I echoed in surprise. "Yesterday I was in Bombay. They said he was there." Someone yelled out: "He goes like the wind. He's no ordinary human being. Not even the Director can stand against him."

I buttonholed the agent. "What'd he look like?" I persisted.

"He's a giant—about fifty feet tall. He has a red beard and his eyes burn with blue flames. His hands are long and slim, and they have only three fingers. On the middle finger he wears a ring. As the ring flashes upon you it fills you with unutterable peace. Not like the drugged sensation you get when that damned Director rays you. He's a brutal tyrant, is the Director. To hell with him. Friends, I was a Deseco agent, and I know. I could tell you stories—"

An ugly roar arose. "Down with the Director! Kill him! The Master says so. By July 4th we must know who's for the Master and who's against."

I STEPPED hastily aside. Just how fast did rumor travel? Only yesterday, in Bombay, I had described the Master to a Hindu merchant in the market place. A fat, puffy merchant who had listened impassively to my description, and made no reply. It was a test on my part; a deliberate, scientific test.

For I had not really described the Master. I had concocted a new description—bizarre, incredible. One that I had never heard before. And here it had met me in distant Patagonia, faster-traveling than the plane that had carried me. Of course, it might have come by radio; but it was hardly possible. For the Director had strict control of every means of communication, and even the mention of the Master's name meant sudden death.

I had stepped aside just in time. The friendly, commonplace salesman who had played bridge with me on the liner pushed purposefully through the crowd. His face was no longer friendly; it was set in a terrible mold. He walked straight toward the renegade agent of the Deseco, hand in pocket.

"Shut your mouth, you fool!" he snapped. "And come with me." The agent whirled on him. His eyes dilated. His finger pointed accusingly. "Look at him!" he screamed. "I know him. He's the Deseco man from India. He's a minion of the Director. He—"

I didn't see anything emanate from the newly arrived agent's pocket. Short-wave vibrations are invisible. But the renegade screamed suddenly and fell writhing to the ground.

The Indian agent didn't even look at him. His voice rose coldly. "Circle Guards! Arrest these swine. Take them all to Headquarters."

But the Circle Guards did not move. They stood stony still. The crowd, however, did move. And they moved with a speed that shocked me with its ferocity. An animal snarl moaned from their lips. They fell upon the astounded agent in a pack. He killed three; and then he was down—a screaming, mangled mess of blood and flesh around which the mob growled and swarmed.

I felt suddenly sick, and turned away. It had been terrible. It was revolution!

FROM that day on I prudently decided to vanish. It was no longer healthy to play tiddlywinks with the Deseco. Things were moving too fast. By this time the Director would have wearied of my wild-goose chases. He would know that I had no intention of leading his minions to the Master. Being a very clever man, he would do something about me, and do it fast.

This business in Patagonia, therefore, was my opportunity. Both the agent who had followed me and the agent who was to take over had died. Even a super-efficient organization couldn't cope right away with such a situation. Especially when revolt had begun.

Not that the revolt was anything more than a beginning. There were still plenty of Circle Guards and Deseco men who did the Director's bidding. By the end of the day they had converged on the troubled tip of South America. A thousand rioters died on the spot; ten thousand more were hustled away into the unknown. Quiet reigned!

But it was no longer the obedient quiet of several months ago. It was the superimposed quiet of an unmasked and brutal dictatorship. The long, hypnotic spell was broken. The survivors went as before to the Assemblies, but they went sullenly, resisting in the depths of their minds, ready for another spark to touch them off.

The spark of the Master!

The man from Saturn!

He who was about to liberate the world from the suddenly loathsome reign of the Director!

I had taken advantage of the turmoil and the snapped threads of the Deseco to shift feverishly into disguise. In the matter of disguise I had long before determined that the bolder it was the better its chance of success.

Therefore I became a Deseco agent, with credentials which I had managed to filch from the pockets of the Patagonian who had died. A few indelible marks to change the contours of my face completed the job. Nothing elaborate. Elaborate disguises usually defeat themselves in the end.

Thus armed, I flew boldly back to Megalon on a small, slow-moving air freighter. There was nothing more I could do. And I wanted now to be dead in the eyes of the Director; one of those blasted to bits in the Patagonian riot.

I had done the Master's work as best I could. I had dropped foci of infection all over the world. These foci had spread and coalesced with incredible speed. Men appeared now in great cities, in remote mountain districts. They, too, were disciples of the Master. They, too, had seen the super-liberator, so they proclaimed; and they exhorted their fellows to rise against the Director.

The deadline was July 4th. On that fateful day the sheep would be separated from the goats. The Master would act; but the people must act first. Otherwise the Master would decide they were slaves, with the mentality of slaves. He would cleanse the Earth of Director and slaves alike. The new order of things would be only for the strong, the worthy, those capable of self-sufficient freedom.

The agitation was no longer in whispers. It spread -like a prairie fire; it raced before the wind. I heard about it in my secret retreat close to the strongholds of the Director, and was glad. The Master had many disciples now. I was but one among thousands. With me were Helen and little Jacky. With infinite care I had smuggled them out of our home right under the very spy instruments of the Deseco. I took no chances on a sudden stroke of vengeance by the Director.

Not that he didn't have many other things on his mind. He wasn't taking all this lying down. When he realized that his hypnosis waves were meeting with strong counter-hypnoses, like a sensible man he shifted tactics.

Bands of highly trained Circle Guards, mechanized and mobile, made swift forays to the worst points of infection. Thousands died in the cold, methodical destruction of cities. Thousands more lingered in concentration camps. Millions fled screaming from the approach of the units. Terror, bloody and unabashed, roamed like a wild beast over the Earth.

I HEARD of all this in my well-concealed mountain retreat and felt a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. Was the Master then not as mighty as I had conceived him to be? Or was the Director more ruthlessly clever than even I had thought?

It was the first day of July.

Within three days there would be a final showdown. Either the Master would triumph, or the world would sink back into the slavery it had known; indeed, a far worse, far more brutal slavery than before.

Within three days!

I moved restlessly about the rather elaborate underground shelter I had been careful to prepare well in advance. In my holidays I had prepared it, deepening and widening some natural caves I had discovered in my mountain-climbing jaunts. It was ideally situated.

The spur of the mountain range into whose flank it penetrated commanded a double view. To the south, well within unassisted vision, hung the stronghold of the Director. Many a time, during those last few days, I had crawled cautiously from the well-hidden entrance to my retreat and lay motionless among the leafy underbrush, studying those grim walls, the gray, straight upthrust of them. Behind them, silent though they seemed in the dancing haze of July, I knew there was feverish activity. The mounting of great engines of destruction, the triple reinforcement of the already impenetrable protective screens against the well-advertised advent of the Master.

No human forces, no waves of desperate men with weapons in their hands, could possibly avail against those defenses.

But against the Master? I did not know. He had new weapons of offense—I knew that much. Weapons which human beings as yet had used haltingly and with a certain crude success. Terrible weapons—irresistible, I hoped.

I stared across the intervening valley and reflected that no defenses, no matter how perfect, were any better than the men who handled them. It was true that the Director had gathered against the coming menace his most trusted Pretorians and the best of Deseco and Circle Guards alike. But I remembered the Pretorian who had escorted me back from that fateful interview with the Director; I remembered the Patagonian agent and the Guards who had surrounded him; and I took some comfort from my thoughts.

And the Director himself. Superbly clever as he was, it was hard for human flesh and human brains, no matter how steeled, to await the onslaught of an unknown, hitherto invisible antagonist. Especially when the date of his coming had been announced on a thousand thousand tongues. Especially when the Weapons at his command were likewise unknown, yet proclaimed in advance as superhuman and irresistible.

Adolf Hitler, back in 1940, had first evolved this particular technique of demoralizing nations on the defensive. His technique had been crude, fumbling; yet even so it had proved terribly effective.

To the north, spreading wide over the level plain, glowed the great city of Megalon, capital of the world. Ten million people inhabited its huge towers and airy apartment blocks. Ten million people who stirred restlessly under the promise of the Master and stared with hate-filled eyes toward the heights where the Director was.

LITTLE JACKY gurgled and played contentedly inside the cavern. He toddled on fat legs through the series of chambers, crowing with delight, and making those queer sounds which Helen and I were sure were meaningful words. I permitted him the run of the place, except for one end chamber which I had sealed off, not permitting even Helen to enter. In there were weapons, I explained, dangerous for children and untrained women to handle.

Helen was worried. She tried to carry on bravely, but the strain was telling.

"We can't stay here forever," she said.

"No," I admitted. "But after the Fourth—"

She broke down then. "I'm tired of hearing about the Fourth of July," she cried. "I don't believe in it; I don't believe anything's going to happen. The Master! The Master! That's all I hear wherever I turn. I'm beginning to think this superman from Saturn is a myth. I don't believe he even exists!"

"Helen!"

She saw the shock written plainly in my face. I was trembling; frightened, even.

Instantly she was remorseful. "I... I'm sorry, darling. I know you've seen him yourself. It... it's just my nerves, I suppose."

I patted her warm-glinting hair; kissed her. "Others have seen him, too," I said. "Thousands by this time. All over the world. They all agree—"

For a moment her mood reasserted itself. "They don't agree, darling. Every time I hear about him I get a different version. First he was -like a man, 3 little taller and a little more majestic. That's the way he appeared to you that day on the mountainside, didn't he?"

"Yes."

"But now he's as huge as a building; he is clothed in shining metal; he is clothed only in the wonder of his beard: his color is red; his color is the blue of the sky; he has three-fingered hands; he has no human limbs." She buried her head on my shoulder. "How can one believe such ridiculously variable accounts? If you hadn't seen him with your own eyes, my dear—"

I held her tight. "All eyewitness accounts are like that," I told her earnestly. "As the wife of a man who has devoted most of his life to the application of psychology to historical data you ought to realize that. And especially when the thing they see is so startling and novel. The wonder is that the accounts don't vary even more than they do. I'll grant you even," I added, "that some of those who are the loudest witnesses saw nothing. There are induced visions, familiar to every practicing psychologist. Oh, the people who have seen them are honest enough. They actually think they have seen what they describe. But the visions are merely the projected hysterias of their emotionally insecure minds, generated by the universal belief."

"I suppose so," she said at length. "Very likely that accounts for the most preposterous descriptions."

I was limp and shivering for some hours after that. But I gradually calmed down. After all, Helen had always been that rara avis among women—an intellectual skeptic.

THE NIGHT of July 3rd was a restless one for me. I didn't even try to sleep. Luckily, Helen was pretty much exhausted and she slept deeply, so I didn't disturb her. She didn't hear the comings and going of my restless feet.

July 4th dawned warm and breathless. Even within the deep-delved caverns it was hot. Outside, the sun rose in a burning ball and the air sweltered and swooned. A heavy silence hung over all nature, as though the Earth was holding its breath against the advent of the Master, come to fulfill his promise of liberation to the oppressed peoples of this world.

We stared out at the peaceful scene—Helen and I.

"Where is he?" my wife demanded. Her voice had a queer, choked sound.

"I don't know," I admitted. "It's early yet. Perhaps—"

Again I turned my eyes toward Megalon. I couldn't understand it. Had human nature changed overnight? Was psychology no longer a science? Could it be possible that—

A noise like a gathering wind came from Megalon. A noise as of millions of scuffling feet and millions of angry voices.

"Ah!" I said.

"What is that?" cried Helen, whirling toward the plain.

But even as she spoke the noise became a clamor, and the clamor a tremendous roar. The floodgates opened. Like a storm-lashed sea the people came running, surging out from the great city, spreading like undiked waters over the huge flat plain. Thousands of them, millions of them, tens of millions! More than had ever dwelt in Megalon; more than had ever dwelt in all the central area. Men from all the nations, men from the distant continents, men with weapons in their hands and a rapt fanaticism on their faces.

I smiled then and felt a great contentment course through my veins. Psychology was still a science! All through the darkness of the night they must have gathered, hurrying to Megalon by stratosphere and land and sea, come to witness the smashing of the Director by the terrible might of the man from Saturn.

Bands of Circle Guards swooped down upon them in great warplanes; other bands unlimbered their deadly field weapons. Huge swaths scythed through the people's ranks; but on they came with eager clamor and a blood lust in their voices. The Guards made a stand; the planes swooped low. But the people were not to be denied. Weapons blazed and the ground shook. Deadly vibrations crossed and recrossed. Then the ranks closed up and flowed on triumphantly. The Circle Guards were no more.

"The... the Master must be leading them!" Helen cried breathlessly. "They're going to storm the Center."

I did not answer. My eyes were turned anxiously toward the stronghold of the Director. Behind those grim straight walls what was happening? Their sullen, watchful silence mocked me.

On and on raced the gathered nations of Earth. It was frightening, superb. Man by himself is a puny animal, naked and helpless in his shivering aloneness. But joined with his fellow men, swarming in multitudes, moving in resistless tide, he is a terrible creature before whom the very mountains shake and the paths of the heavens split to give him passage.

They foamed past the spur from whose slope we watched and boiled on toward the mountain wall on which perched the stronghold of the Director. It was breathless, awe-inspiring; but—

AGAIN my eyes clung to the silent heights. There were millions on millions of men to the attack; but I knew the defensive weapons of the Director. The sweat started on my face, ran in rivulets down my body. If only I had eyes that could penetrate stone and mesh vibrations! If only I could penetrate within those walls and see for myself the Director and his Pretorians! Were they—

As if in answer, a terrific scream made the former multitudinous noises sound like deathly quiet. The attackers had boiled up against the mountain base. They started to clamber up the stony paths. There was a blast of flame; a crackling, roaring sheet that swept aloft like a solid wall to the very heavens. Within that fiery blast uncounted thousand crisped and flashed to blazing extinction.

I clenched my hands until the blood spurted from nail-scored palms. The Director had acted! The Pretorians were loyal!

Helen shaded her eyes with upflung hand to keep away the awful sight. "The poor, poor people!" she sobbed. "Where is the Master? Where is his boasted power?"

But I had fled; fled into the interior of the caverns, sobbing myself with breathless hurry. Yes, where was the Master? He had to appear! Had to, I told myself with fierce repetition. Yet even if he did, could he turn the tide? Were both Director and his cohorts impervious to the peculiar might of the Master?

I came out again in a little while. I found Helen moaning and shuddering with horror, yet unable to tear here eyes away from the shambles below. Oh, the people were brave enough. They yelled and shouted and surged forward again and again at the mighty defenses that enveloped the stronghold. Their weapons blazed and crackled and spat a deadly hail. They flung their bodies into the invisible wall of vibrations, as if to exhaust its gigantic energies with the holocaust of their flesh and blood, and permit the clambering millions behind to pour through the gap.

But the thousands died, and the screen remained intact. High above, secure behind that terrible defense, the Director appeared calmly on the wall. His form was dwarfed by distance, yet to my heated imagination it seemed I could detect a derisive smile upon his face. He was afraid neither of the peoples of Earth nor the man from Saturn. If there were a man from Saturn!

Already the fanatic multitudes were falling back in despair. A huge wail burst from them. Where was the Master? Had he led them on to this, only to desert them?

Little pulses hammered all over me. Yes, where was he? He should have come by now. Had anything gone wrong?

Then I sucked in a deep, gasping breath.

"Look!" I shouted insanely, as if my voice could beat down the million-throated clamor and penetrate their bewildered brains. "Look!" I yelled. "The Master! He has come! He has come!"

They saw him almost as soon as I did. A sudden hush fell upon that torn and bleeding multitude.

Even the vibration wall died into invisible quietude. All nature seemed to stop and watch.

He walked in the air, high above the frozen people, level with the grim gray walls of the Center. He was clothed in light and misty radiance. He was gigantic and terrible. His face was a blur of awful anger. His moving feet churned the impalpable air into a spectrum of flashing colors. His arm was outstretched in accusation as he walked, slowly and steadily, toward the Director!

Helen was shivering against me. I myself was in a fever, so that I could hardly see.

"The Master!"

"The man from Saturn!"

"He has come!"

Scattered cries rose from the more daring. The cries coalesced and swelled into a single earth-shaking roar.

"The Master!"

Then there was silence again. Even the wounded and the dying stopped their moaning and turned desperate eyes against his progress.

I dared not look. Yet I had to. I forced my eyes around, focused my dancing vision on the Center.

THE director was a brave man. I must say that for him. He stood erect upon the wall, facing the awful thing that walked the impalpable air toward him. He called out in stentorian tones, so that his voice drifted over the intervening distance and I could hear.

"Man or devil or being from another planet, it doesn't matter. He cannot penetrate the screen. He's flesh and blood. Shoot him down, men; shoot him down!"

The Pretorians had come thronging to the wall at the sight of the Master. They stared and stared and their, bodies were huddled. I managed somehow to pluck the tiny spy visor from my pocket. It wobbled in my hand as I trained it upon them. Somehow I steadied its jittery arc.

The Pretorians were frightened. Their eyes bulged and their mouths were agape.

The Director turned on them with hushing contempt. "Fools!" he cried. "He's flesh and blood, the same as you! Even if he seems to walk on the air. A simple scientific attachment could manage that. You fly in planes and great liners, don't you? Come to your senses. Use your weapons. Annihilate him!"

But the Pretorians shrank away. The sight of that gigantic figure moving with inexorable slowness toward them unsettled their reason. For months they had heard of him, whispered among themselves, wondered. And now he was here. They wore paralyzed.

The Director cursed them. He ran toward the nearest snouting gun. He swung its yawning orifice directly upon the approaching Master. He touched a button.

I held my breath. There are two types of weapons like that. One uses explosive tetratoluol; the other disintegrating vibrations. Which was this?

There was a blast and scream of sound. The mountain enveloped in thundering flame. The moving figure submerged in smoke and exploding missiles. I released my breath.

The smoke cleared; the flames died away; the whining fragments rained to earth.

And the Master moved calmly forward. Intact, unharmed, impervious to that hell of shot and sound.

A tremendous cry burst from the plain. An answering, despairing cry broke from the Pretorians.

The Director looked staggered for a moment. Then he spun on his heel, rushed toward a second weapon. "Fool that I am! Tricked; betrayed! I should have known! But now I know—"

He heaved furiously at the great gun on its floating mount. He trained it on the still-advancing figure. I felt my heart stop suddenly. Was this the other type—the vibrator?

His hand moved toward the button, and I sobbed aloud. I cowered against what was going to happen.

Helen cried sharply: "What's the matter, John?"

On the walls of the stronghold the Pretorians sprang into life again. Fear flamed in their eyes; fear of the wrath of the Master; quick, leaping hatred for the Director whom they had served in blind obedience. Their short-wave projectors came up. They made no sound; they flashed no danger signal. But the Director crumpled suddenly, his finger stabbing wildly for the button. It missed contact. He fell in a sodden heap.

Release came to the Pretorians then. They flung down their weapons and cried out imploringly to the inexorably nearing Master. They scattered like frightened sheep. Some ran to turn off the current that activated the screen; others fell in a frenzy of demolition upon the still-pointing armament. Others beckoned to the multitude beneath in token that they had joined themselves with the people. Some fell on their knees and begged forgiveness.

The thing had happened so fast that the swarming plain was still stunned and motionless. I threw down the spy visor, thrust my hand against my side in a convulsive gesture. Helen was stammering incoherent words.