RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, February 1937, with "Beyond Which Limits"

THE small two-seater gyrocopter slid swiftly down from the 10,000-foot level until its altitude was 8,000 feet, then it threw out its vanes from their jointed recession within the smooth skin of its streamlined hull. The great blades caught at the resistant atmosphere, whirled in rapid revolution. The plane decelerated smoothly, until it hung, almost motionless, over the great mesa fifteen hundred feet beneath. Lights blinked, in the universal code, from the captive balloon that swayed gently in the thin breeze, and before whose aluminum bulk the gyrocopter had come to a quivering halt.

The girl in the pilot seat leaned forward, eyes intent on the winking lights, translating as they flickered on and off with an assurance born of long practice.

"We're still in time," she told her companion, "but it was a close call. The air director says there's only one parking space left on the whole mesa, and we'd better hurry if we want to grab that. Look, there are three more latecomers up in the air, trying to beat me to it. Swell chance!"

She laughed, pressed a button on her right. A green light uncovered, glowed Steadily a moment, then darkened. It was a warning signal to the belated planes; the signal of preemption, meaning "Stand clear! It's all mine!" Then she pressed another button.

The whirling vanes slowed their mad pace. The motionless gyrocopter dropped down smoothly, perpendicularly toward the mesa.

The sun was setting in a blaze of glory over the parched mountains that rimmed the desert landscape of New Mexico. The plateau was a vast, deserted bowl, except for the mesa that gauntly reared its level table top a full two thousand feet above the cactus-dotted floor.

Even as the sun went down with an almost audible hiss of extinction, and darkness descended with the suddenness of the desert, lights twinkled into being on the mesa top. Myriad lights—lights that rimmed in noble outline the great dome of the newly erected International Astronomical Observatory, that picked out the huddle of smaller enringing buildings which housed subsidiary instruments, that swung in spider tentacles through the plane parking area, and swarmed in clusters over the outdoor amphitheater. In the still, mountain air the concerted whisper of eager, thronging humanity came up sharp and clear to the silently dropping gyrocopter.

Lorna Page stared through the porthole at the uprushing sight. "It's beautiful," she whispered, with a little catch of breath.

The young man in the cushioned seat next her seemed wrapped in thought; he did not even trouble to follow her glance. And, from the furrows on his forehead, it was obvious that his thoughts were not pleasant.

She repeated her admiration, a bit louder, more violently. He started, stared, said absent-mindedly: "Oh, the mesa! Yes, very beautiful! Very beautiful!" And he relapsed into his former troubled silence.

THEY were coming close, now. A single luminous space in the crowded rows of parked planes showed barely room enough for the gyrocopter to squeeze into. Lorna jockeyed her craft skillfully over the spot, whirled the vanes a trifle faster to slow down the speed of their fall, and dropped, with not an inch to spare, into the oblong markings. Then she leaned forward and cut off the motor. But she made no further move to get out.

Instead, she turned steady eyes on her companion. There was a strange, appraising quality in her glance. "Jim Weldon," she said quietly, "I know it's been a blow to you. It was most unfair of the International Commission to pick Norvell Sands for the post of honor tonight at the inauguration ceremonies, instead of you. This wonderful new telescope of the observatory is the child of your brain; without your invention of the photo-electric mosaic it would never have been possible; yet they chose Norvell Sands. It was a rotten shame, but"—and her voice became a bit breathless—"I—I didn't think, Jim darling, you'd take it so hard. I—I thought it——"

Jim had not been attending rightly to the beginning of what was obviously a set speech on the girl's part. It had pained her to see the man she adored sulking and acting the part of a poor sport. How else could she decipher his gloomy brow, his preoccupied air, his few words since she had picked him up, protesting, at the Croydon Observatory and hurtled the intervening six hundred miles to get him here in time?

Jim sat up, stared blankly at the girl. "Eh, what's that?" he grunted. Then Lorna's hurried implications smote him, and he thrust back his head and laughed. Somehow his laughter struck a false note. "Don't be silly, darling," he answered. "I never even thought of that end of it. Why should I? Sands is a considerably older man than I; he heads the 200-inch telescope at Palomar, the No. 1 Lens that was set up in 1938; while my 200-inch telescope at Croydon was not erected until 1947. I think the commission made an excellent choice."

Lorna was obviously bewildered. "Then why, my dear, have you been——" She stammered and stopped. It is difficult to tell one's sweetheart that he has been sulking.

Jim grinned, trying surreptitiously to keep the worry out of his voice. "Sulking?" He helped her out. "Forget it, sweet. You should know better." But, in spite of himself, his face clouded. There was almost fright in his look as he stared through the side port at the great, graceful loom of the observatory as it etched its bulk against the velvet blackness of the desert. Yet how could he tell Lorna, any one, of his vague, inchoate fears, hardly formulated even to himself.

THOSE last photographic plates from his own monstrous lens, for example, which, fortunately, he had privately developed and then stared at with incredulous eyes. He had tried out for the first time his experimental "mosaic" on the great telescope, had directed the huge mirror, without quite knowing why, on the Black Hole in Cygnus.

That Black Hole, in the early days of astronomy, had been envisaged as an actual hole in the sky. Sir William Herschel had exclaimed of a similar one, "Hier ist wahrhaftig ein Loch im Himmel!" Here is actually a hole in Heaven!

But modern astronomers had come to believe that these black vacancies were merely vast, dark nebular masses, whose invisible substances screened from earth's view forever the teeming stars behind. Jim Weldon had accepted that view, nor had the 200-inch Croydon disturbed his acceptance. That is, not until that strange, terrible photograph with the photo-electric mosaic!

The thin, evanescent layer of silver that clouded the film was close to the borders of visibility, so faint, so nebulous, that Jim strained his eyes to piece out the gaps in what he thought he saw. Strained—and at the same time prayed vehemently that he could see no more. It was a frightening sensation. The skin on his body prickled as though he had been staring at things too horrible to contemplate.

In vain, he told himself that he was being a fool; that all there was on the photographic plate was a mere formless breath of vague cloudiness; that he was a scientist, not a hysteric given to imaginative conjurings. He stormed at himself; but, for all his logic, all his finely drawn scientific training, certain deep-rooted instincts—the instinct of the Neanderthaler in the presence of the spirit-peopled dark—swept all else away.

The 200-inch telescopes had not lived up to earlier expectations. They had, of course, in the sense that the universe had immeasurably expanded before their questing eyes. But the knowable universe of space time had proven considerably larger than had been anticipated. The huge mirrors, gathering the light of one billion, two hundred million light years, had revealed but new outlying universes, new nebular galaxies. There had been no end anywhere, no matter which portion of the heavens had been swept.

The experimental mosaic invented by Jim Weldon had increased the depth of vision to two and a half billion light years; but, except for this single spot in Cygnus, it had not mattered.

All Jim's training shrieked against what he felt he must do. Almost like an automaton, yielding to forces beyond his control, he had deliberately shattered the curious photographic plate into a thousand shards, had carefully dismantled the mosaic and packed it away. To the later questionings of his subordinates, he had made plausible answer to the effect that it had not worked quite as he expected. But from that time on the staff and Lorna Page had noticed a change in him.

He was crazy, he told himself; he had overworked and needed a rest. After all—he would think during the long, sleepless nights—what was it that he had' actually seen? Nothing, nothing that a saner, more normal person wouldn't have laughed at. He knew, without telling, what Norvell Sands would have said, after a brief examination of the plate. "My boy," he would have boomed, "what you have there is merely confirmatory proof of what is already well established. The so-called Black Hole in Cygnus is a masking dark nebula. The better resolution of your experimental mosaic has merely gathered the faint reflections of light from the neighboring stars, and deposited them on the plate."

Even now, still seated in the gyrocopter on the International Mesa, aware of the probing look of the girl he loved, uneasily aware that the seconds were hurrying by to a denouement that he dreaded, he could hear in his imagination the sudden, gusty laugh of Sands at his hesitantly expressed fears.

"Shapes out there?" echoed that ghostly laughter. "I'm surprised at you, Jim Weldon. You, of all people, one of the clearest headed young men we have, to give way to jittery nerves! What possible shapes could there be in Cygnus, or anywhere else? Have you ever watched the clouds on a summer's day? Haven't you ever seen castles and horses and giants and sea serpents and Heaven knows what? Surely you realize that——"

The invisible wrestling came to an abrupt halt. "Well?" demanded Lorna. "Are we going to sit here all night, and miss the ceremonies?"

Jim jerked to an awareness of his surroundings. "Sorry, darling," he muttered. "Let's get going."

He swung the door open, jumped lithely out. Lorna followed with easy grace. He took her arm. and they walked in silence toward the huge outdoor amphitheater. He could feel her body, ordinarily pliable toward his, now rigid and distant. She was hurt, disappointed in him. He grimaced to himself in the dark. How could she understand what he himself did not? How could he tell her that the directorship of the international had first been offered to him, and that he had turned it down, without going into explanations which would have sounded utterly incredible? Now he was sorry for his refusal. Once in charge, he might have been able to devise ways and means——

THEY found seats just in time. The great concrete bowl was packed with thousands of expectant people. They had come from the ends of the earth for this epoch-making occasion. The flower of world science—astronomers, physicists, chemists, biologists, the presidents of three republics, the dictators of six nations, a solitary king from a solitary monarchy, statesmen, economists, famous authors, captains of industry—all were present. As well as such a horde of anonymous John Citizens who had been able to beg, borrow or steal the necessary metal disks of admittance. For once, all rivalries, racial and political divisions, were obliterated. They had come to pay tribute to the mightiest achievement of modem science, of man's aspirations toward the unknowable.

Fellow scientists rose eagerly before Jim's youthful figure, before the trim loveliness of the girl on his arm, as they passed down the aisle to their seats. He returned their warm greetings with short, preoccupied nods, so utterly unlike himself. Lorna's inward thoughts were a torment. Had she misread this seeming stranger at her side? Was he but a marble idol she had set up for worship in the secret recesses of her heart, with feet now, for the first time, exposed of vulgar clay? But nothing of that struggle showed in her pale, composed face. And the murmurs of the general populace were as much for her as for the youthful scientist of world reputation, whose much advertised mosaic was for the first time being used in connection with the tremendous instrument they had come to see unveiled.

Jim had been offered a seat on the dais in the center of the field, together with all the other guests of honor. But a strange reluctance had impelled him to refuse, to seek the anonymity of the common grand stand. In fact, it had been that same unaccountable reluctance which had made them late, which had yielded only to the pained look in Lorna's eyes when he bad flatly announced that he would not come.

There was a sudden stir, a craning of necks, a wind of expectancy. The ceremonies were about to begin.

Jim Weldon was never to forget that scene. The soft, velvety blackness of the desert night, the stars overhead like limpid, bright-glowing flowers, the motionless traffic balloon with its single red warning light, the maze of interlacing lights, the illuminated purity of the great observatory, the banked masses of people, the platform of honor in the center of the stadium, and the crowding dignitaries who sat self-consciously and importantly thereon.

The President of the United States arose slowly. A hush fell on the assemblage. He was a tall, spare man, with gaunt cheeks and a kindly, slightly weary smile. He spoke without notes, and the amplifiers carried his voice clearly and distinctly to the topmost row of seats. It was, he observed, an epochal occasion. They were gathered to do honor to man's most idealistic achievement. Wars had torn the world; there had been certain occurrences of late better left unmentioned—here the dictators looked a bit fiercely uncomfortable in their glittering military uniforms—but for the first time in many years the nations had united in a common cause, had poured out lavishly of funds and brains in a common enterprise from which no Earthly territories could be gained, no new markets be tapped, no new colonies of overabundant populations be planted.

He paused; the hush deepened. Instead, he went on in his slightly weary voice, only the cause of pure truth was being forwarded, the restless reaching of man for the stars. It was confidently expected that the age-old dreams of the great scientists would finally be realized. In minutes now the great telescope would be battering at the gates of space time, would seek to wrest from the hitherto impenetrable heavens themselves the secrets they had long withheld. He therefore took great pleasure in welcoming the peoples of the earth on this momentous occasion. Then he sat down to thunderous applause.

THERE were other speakers—too many of them, in fact. Speeches from the dictators, each of whom seemed slightly regretful that he had been inveigled into spending money on a telescope, of all things, to be installed, of all things, in a nation not their own, when such money might much more profitably have gone into big guns, submarines, and the new experimental rocket bombers. But they managed to be fulsomely pompous, betraying their true thoughts only in veiled allusions. The solitary king was an utterly charming, politically ineffectual young man, half friendly, half cynical.

Then came an interminable string of must addresses—— the financial giants who had contributed, scientists, politicians, who could not be slighted. The audience grew restless under the torrent of words. The platform dignitaries struggled with boredom and politely withheld their yawns. The massed spectators were not as well-mannered. They scuffed their feet, chattered, muttered discontentedly. They had come to see the telescope, to watch. Norvell Sands peer into the eyepiece and report to them immediately that which had never been witnessed by the eye of man before.

A purely theatrical effect, it was true. Sands had protested against such futile dramatization. He was not, he argued, a Hollywood star or a President of the United States, that it was necessary for him to strike a pose for the public eye and the public prints. Astronomical work was not performed as a publicity stunt; it was essentially tedious routine and a strictly private communion. But necessarily, though with an ill grace, he had had to yield to the insistent demands of the news casters and the vox populi.

The president felt the growing tension, and, at one bold stroke, lopped off a half dozen waiting speakers—who were nervously glancing at their set manuscripts—and rose to announce the final addition to the plethora of words, the erstwhile director of the Palomar Observatory, the newly chosen director of the International Observatory—he might add, unanimously so chosen. Jim Weldon, tense in his seat, grinned wanly. Not even Sands himself knew that he, Jim Weldon, had turned down the coveted position.

Norvell Sands arose to a thunder of sound. Thank Heaven!—breathed the audience. It would soon be over. Then they could settle back and watch the telescope in action. Three quarters of them, and that included a goodly number on the platform, had only the vaguest thoughts as to what would happen. But they were sure it would be something dramatic.

Sands was an elderly man with a long and honorable, if slightly academic and uninspired, career behind him. He had none of Jim Weldon's youthful zest and brilliant intuitions, but he was a solid man, with both feet firmly, and unimaginatively, planted on the ground, even though his eyes peered up occasionally at the stars.

The heavens to him were a mathematico-physico-chemical problem to be solved; the unknowable was that which, as yet, he had not been able to reduce to an exact equation. The glamour, the romance, the mystery of the universe were not for him. He snorted derisively at some of the brilliant, semi-poetic conjectures of young Jim Weldon. "Bring me facts!" he would boom genially. "I don't give a tinker's dam for supposings; I want stuff my instruments can measure, my equations decipher."

Nevertheless, a sound astronomer, with no such nonsense about him as instinctive shrinkings from a faint, almost undecipherable film over the Black Hole of Cygnus.

Lorna Page leaned forward to listen, clenching her hands to ease the inward hurt. Jim should have been up there in Sands' place, should be now taking the plaudits of the world. Yet perhaps, she told herself with a growing panic, the commission had been right. Even now, Jim sat at her side, his brow wrinkled, his lips bitterly tight. He, too, was staring at Sands. She misread that glance utterly. To her, it was the expression of a hurt vanity, of a jealous pettiness that only short weeks ago she would have thought inconceivable in Jim Weldon. But Sands was already speaking.

IT turned out, in the beginning, to be a rather dry, monotonous lecture on the newly installed telescope. It was, he declared, 300 inches in diameter, a 50 per cent physical mark up on existing instruments. The mirror bad taken 6 years to pour, cool and grind. It was of pure, fused quartz, with not the slightest bubble in all its vast expanse. Ordinarily, he continued, this in itself would have been a tremendous advance. For, theoretically, the limits of vision with such a mirror would widen nearly two billion, seven hundred thousand light years, perilously close to the latest calculations as to the radius of the universe of space time.

He paused, and, suddenly, his voice kindled with a new warmth, an emotion that jerked slightly nodding heads awake. "That, in itself, is an achievement," he declared. "But there is something else about our instrument, something so novel, so revolutionary, that we ourselves are not aware of its ultimate complications. I refer to a certain attachment which, until now, has been kept a strict secret at the modest insistence of the inventor himself, but which I believe should now be broadcast to the world:"

Jim jerked forward, as if to catch the speaker's eye, to shut off what was coming, but he was a mere dot in a sea of faces.

"I refer," said Sands, "to the photoelectric mosaic, and to James Weldon, the brilliant young director of Croydon, its inventor. To him must go the glory of whatever new discoveries we may be able to make; and, in all humbleness, and with due deference to the wisdom of the commission, it is my belief that Weldon should now be occupying this platform in place of myself."

The audience craned and swayed with emotion. No one thought of sleeping any more. Those few in the immediate neighborhood of Jim turned their heads, tried to catch his eye, to smile approval of Sands' generous gesture.

But Jim shrank back in a vain attempt to escape notice. He didn't want recognition; he didn't want glory. He wanted only to dismantle his mosaic, to forget that he had ever invented it. Lorna was breathing rapidly. She was torn between conflicting emotions: exaltation at this public avowal of Jim's brilliant achievements, and the sinking sensation that Norvell Sands was showing himself the better man by the magnanimity, the self-effacement of that very avowal. But Sands was still talking, and she strained forward to drink in every word.

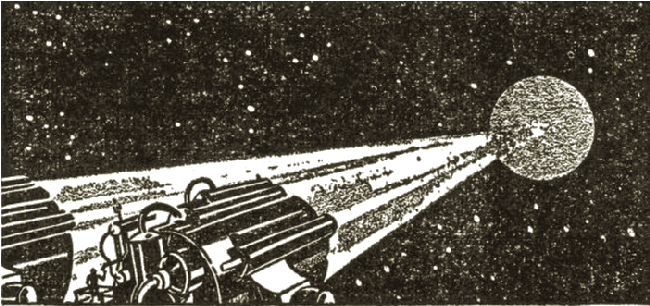

"The principle of the photo-electric mosaic," he said, "had been faintly adumbrated as far back as 1933, by Dr. Zworykin; but seemingly insuperable difficulties had halted any practical attempt to put his ideas into operation. James Weldon has succeeded, and succeeded amazingly. He has concentrated in his instrument the light-gathering properties of literally billions of infinitesimal photo-electric cells.

"He took a sheet of an electronegative alloy of his own contriving and, by a most ingenious process, deposited upon it ultramicroscopic globules of silver, each so tiny that its diameter is less than a single wave length of light. Silver is, of course, electropositive. Accordingly, when a beam of light falls upon this mosaic, a small electrical charge is built up on each of the countless little globules of deposited silver. Condensers store up these charges, which are directly proportional to the intensity of the original light beam, and the silver globule pattern thus formed represents an electrical image of the source of illumination.

"An electronic scanning beam, so narrow it covers only a single one of the ultramicroscopic silver beads at a time, sweeps at tremendous speed over the mosaic. This has the effect of discharging the silver-alloy photo-electric cells one by one, and releasing, simultaneously, the condenser charges. A current passes from the condenser, is stepped up and amplified enormously in like fashion, as in radio communication, and a visual image is reproduced in the form of light waves by another electronic beam and fluorescent screen. This magnification alone had been set at ten thousand times.

"Think of it! Add this increase to the original magnification of the powerful 300-inch mirror on which the light from the distant stars has fallen, and you have a total magnification which runs to an incredible figure."

HE paused dramatically, and his eye kindled. "Ladies and gentlemen," he declared slowly to a now intent audience, "I believe that with Weldon's invention attached to the international telescope, we are about to solve the last, the hitherto immutable secret of the universe. We shall penetrate far beyond the most sanguine limits set upon the radius of curvature of space time. Once and for all the moot question of Einsteinian curvature will be laid to rest. Either we shall see completely around the universe, and view ourselves, so to speak, from the rear, or"—and now his voice lowered to a dramatic whisper in the straining hush—"we shall view the viewless, discover what lies beyond the confines of that space time."

Once more he raised his voice. "And for this, we must thank Jim Weldon." He looked around the crowded amphitheater, seeking. "He is here to-night. He had begged off from the list of speakers. But I am going to ask him to say a few words to you. Jim Weldon, will you be good enough?"

The great stadium rocked with the thump of clapping hands. Jim huddled lower in his seat, desperately. "No!" he muttered half to himself. "I won't speak; I refuse——"

All about him men started up, crowded toward him. "Speech! Speech!" they yelled excitedly.

Lorna faced him with flaming, bitter eyes. "James Weldon," she blazed, "you've acted a petty part long enough. Either you get up on your legs and say something gracious in response to Sands' marvelous gesture, or I'll never speak to you again." She was surprised at the tears that blurred her vision, tried to tell herself they were tears of rage, not of scalding disappointment.

Jim stared at her incredulously. His mouth went suddenly hard, his eyes grim with new-found purpose. So that was it, eh? Even Lorna had turned against him, thought him capable of petty jealousy. Very well then, let her think so, let all the world think so. He'd give them good cause for such a belief. After what he was about to say, he'd be a pariah, a man to be avoided by his fellows. O.K., then. But he'd not permit that horror which he had dimly sensed, to color the thought, the activities, the dreams of the world for uncounted generations to come.

He rose slowly to his feet. A cheer sprang up, swiftly died. He made a splendid figure—young, lithe, with well-set jaw and grim, steady eye. The directional amplifiers swung to where he stood, ready to pick up his words, and lift them out over the thousands. Lorna gazed at him raptly; perhaps now he would redeem himself somewhat in her eyes.

But his first words fell like a bombshell.

"Norvell Sands has overestimated my talents and my modesty," he announced quietly. "I made a mistake when I made my photo-electric mosaic. I see that now. It was based on wrong calculations. Accordingly, I have decided to request its return."

There was a stunned silence; then a low, uneasy mutter. It took time for his abrupt declaration to penetrate.

Sands concealed his startlement in an indulgent laugh. "My colleague is carrying modesty to a fault," he explained. "We have tested his mosaic with laboratory tests, and found that it exceeded even the theoretical claims for it. Of course——"

"You do not seem to understand," Jim interrupted. There was steel in his voice. "Whether good, bad or indifferent, the mosaic is my invention, and I elect to withdraw it from use."

The mutter merged in a gathering growl. Lorna plucked vainly at his sleeve. "Jim! Have you gone mad?" An angry flush mounted in Sands' pinched cheeks, but he controlled himself with an effort.

"I still don't understand," he protested placatingly. "There must be some other reason than the one you've just given for your rather astonishing decision. What is it?"

Jim set his teeth. How could he tell them of the haunting nightmares that had overcome him since he had stared vainly at the photographic plate of Cygnus, and tried to trace in its vague nebulosities things that should never have been traced? In the steady light of the arcs above the International Mesa, in the firm outlines of stadium and spectators' upturned countenances, he realized that perhaps he was a little mad.

They—if he tried to put into words what had been merely an emotional response—would think him wholly mad, would lock him up in an asylum, or, worse still, pass him by with significant gesture and pitying look. Better that he pursue the course on which he had suddenly determined, no matter what the cost to himself.

"I'm sorry," he said stubbornly. "I can give no other reason. But I must insist upon the return of my mosaic, now."

THE growl became an uproar. The amphitheater seethed with ugly sounds. Lorna's shocked cry was a torment to his ears. But he stood erect, facing them all, inflexible.

Then the amplifiers swung back to Sands. The old astronomer's voice thundered out, blasting down all opposition. "It is too late to retract your gift. Your deed of gift, properly signed and witnessed, reposes in the coffers of the observatory. It is legal, binding." His voice trembled, broke. "You are ill, Jim Weldon. You have overworked. That is the only way I can account for your astonishing attitude."

Already a half dozen men of the government police were efficiently at Jim's side, eyes inquiring on the President of the United States for further orders. Jim grinned wryly. He had done what he could. He had spoken out too late. Jail or the madhouse beckoned if he persisted, and it would do no good. He made a gesture of renunciation. "On your own heads be it," he whispered to himself, and sank into his seat. Lorna was crying softly. The police, at a nod from the president, withdrew. The incident was closed.

Already the spectators had quit their benches, were streaming over the flat mesa toward the huge observatory, where the next act in the ceremonial would take place. The unveiling of the great telescope, the first peep into the unknown by Norvell Sands.

Jim's hand went out toward the girl at his side. "Lorna!" he implored.

She shivered away from him, her face tear-stained. "Don't touch me, Jim Weldon," she flashed. "I—I hate you."

He grinned mirthlessly. He had lost everything—his job, the esteem of his friends, the girl he loved. And for what? A stupid, unscientific intuition, a strange horror that had overwhelmed him as if he had been the veriest untutored savage. No doubt they were right—he had suffered a nervous breakdown.

"Lorna, listen to me!" he began again.

"No!" she answered in muffled tones. "Go away."

He did. The great bowl was almost empty; the speakers' stand completely so. They were all at the observatory, waiting the final touches. He strode across the field with long, swift strides. He, too, would watch. He had been a crazy fool; he had imagined things too terrible even for the faintest hint; soon they would prove him wrong. So be it!

Behind him he heard a faint, startled cry—his name being called. He did not slacken his pace.

He bored unnoticed through the jostling, neck-craning crowds, worked his way to a position in front, just as the domed cylinder swung open on oiled bearings to disclose the interior of the observatory. A murmur of admiration arose from the thousands.

Before them, in all its splendor, stood revealed the giant telescope. Its crisscross of open girders extended almost a hundred feet into the night sky. In the trough of the huge steel base was the enormous 300-inch mirror, polished to perfection, glittering in the faint darkness like a lambent jewel.

Halfway up the bridge-like girders was an oblong screen, tilted at an angle, so as not to interfere with the original passage of light, yet able to catch its rebound from the parabolic mirror. It, too, sparkled with its myriad invisible globules of silver. This was the famous mosaic. Jutting from the other side was the eyepiece, almost lost in a bewildering maze of machinery. Light steel stairs spiraled up to a platform convenient to the eyepiece. On this open space stood Norvell Sands, a lonely, dramatic figure against the immensity of the instrument that man's genius had contrived, and man's machines had fashioned. He raised his hand.

AT the signal, the lights of the vast mesa winked out. Only a single, indirect glow bathed his figure, silhouetted it to the tense multitude. The desert stars blinked down wonderingly at the spectacle. The velvet back drop of night seemed never more mysterious. There was not a sound.

Jim's eyes crept up the pointing instrument, stared past its orifice into space. A little cry burst through clenched teeth; involuntarily, he jerked forward. By some incredible fatality, the giant telescope was focused directly on—the Black Hole of Cygnus! Coincidence? With a groan, he realized that he had tried to warn Sands, with careful hints, away from that very spot. He had only succeeded in calling attention to the alleged dark nebula.

A brawny spectator in front shoved back angrily at his lunge; another cried "Shush!"

A hand plucked at him from behind. "Jim!"

The faint, timidly sounded name brought him pivoting around, all else forgotten.

"Lorna!"

In the dark her face was pale, but determined. "I'm sorry," she murmured agitatedly. "My conduct was inexcusable. Whatever you've done, whatever you are, I—I love you, darling!"

Then, unaccountably, she was weeping quietly in his arms, heedless of the jostling crowd, while his heart bounded with a great gladness.

"Lorna!" he whispered, stroking her hair. "I'm not what you think. Some day I'll explain. I may be crazy, but I——"

The vast concourse said "Ah!" in simultaneous exclamation. Jim looked up, startled. Norvell Sands had plucked away the enveloping cloth with a dramatic gesture, had affixed his eye to the eyepiece.

Jim's blood seemed to freeze. His nerveless arms fell limply away from the girl. He could not exhale the bursting air in his lungs. God grant he had been wrong, crazy, anything! His own reputation did not matter. But Sands must not see, could not see, what he had imagined he had seen.

Then his blood started to flow again, his arms prickled back to life, and the suffocation left his chest. Sands had been staring intently into the eyepiece for almost thirty seconds, and nothing had happened. He laughed shamefacedly. "Now, darling, I can tell you a rather silly story——" he started, and was interrupted.

Norvell Sands had shuddered violently, torn himself loose, as if by a supreme effort, from the eyepiece. A piercing scream ripped from his lips. He staggered on the platform like a drunken man, groping for support. His face turned blindly out into the night.

Never, in all Jim's experience, had he seen a face like that. It was twisted, contorted in an agony of hopeless horror. It was the gray, terrible mask of one who had looked into the unutterable depths of Hell. It was the countenance of one whose reason hung on a single, snapping thread.

For one blasting moment the crowd was paralyzed. Then a shout rose in the thick silence. "I knew it!" And Jim was hurtling forward, pounding for the spiral stairs, to catch Norvell Sands before, in his madness, he might look again.

But Sands had heard his cry, looked up with blind, stricken eyes that seemed to clear. He screamed again—it sounded this time like the death cry of a mortally wounded animal—then he had bounded over to the tool box at the rim of the platform, thrust open the wooden cover, was rummaging feverishly in its capacious depths.

Before the horrified spectators could sense what he was doing, two heavy wrenches appeared in his hands. Before Jim could get to him, he had hurled them, one straight for the photo-electric mosaic, the other down into the depths, a direct hit on the huge mirror. There were two sharp, crashing sounds, the splinter of glass. The mighty telescope, monument to man's genius, product of years of unremitting toil, was irrevocably ruined in a single, shattering instant!

By the time Jim had reached the platform, Norvell Sands was a hopeless, senile idiot, mouthing queer, thick sounds, chuckling ceaselessly, horribly. He made no resistance as they led him away——

AFTER the excitement had subsided, and the mesa was bare of all frightened onlookers, except for a little group of grim, harassed men gathered around Jim Weldon, he explained. There had been, he said glibly, a fatal flaw in the conception of his mosaic. The gathered photo-electric effect, instead of scanning in parallel, normal rays, had concentrated to a single, dazzling point. Magnified as it was to almost unbelievable proportions, small wonder that the single beam had seared like a white-hot sword into poor Sands' skull, blinding him, driving him in that moment's agony to dreadful madness. In that madness, he had destroyed the instrument that had brought him low.

He had tried, Jim went on hurriedly, to recall the mosaic as soon as he had discovered the flaw in his calculations; with what result, they were well aware. He satisfied them with the explanation.

But Lorna was not as easily satisfied. As the gyrocopter winged away from that scene of horror and disaster, she turned abruptly to him. "Now tell me the truth," she said quietly.

He was startled. "But I did," he protested.

She shook her head. "I know better. That mosaic of yours was perfect. Your calculations were correct. They had been tested out. I want the truth."

Jim looked suddenly haggard. He shivered. He wanted to forget, once and for all. There would be no more mosaics; he would see to that. Let them build another 300-inch reflector; 400 inch even. Without the mosaic, the mystery of what Sands saw, what he, Jim Weldon, had almost seen, would never be revealed to mortal man. It was true that the sun and its attendant planets were heading directly for the constellation Cygnus, but long before they could reach the incredible thing that lay beyond, an eternity of years would have passed. Earth itself would be but a lost memory in infinitude.

He took a deep breath. "I'll tell you this much—and no more," he told her gravely. "The mosaic did work. As a result, poor Sands saw out into infinity for a distance of over twenty billion light years. Our own universe has a radius of not over five or six billion light years."

He looked up at the moveless constellation of Cygnus, continued with a shudder. "The Black Hole of Cygnus is actually what Herschel had first believed—a funnel of emptiness giving out on a starless space time—and beyond. Norvell Sands saw beyond—out into the void where the universe of familiar things does not exist, where space and time have no meaning, where the impossible itself may be a commonplace. He saw something out there—and the sight drove him mad."

Lorna looked at him again. Her eyes were steady. "What was it he saw, Jim darling?" she queried bravely.

"I—I do not know," he lied, and did not lie. For he had only imagined he had seen, and the adumbration of that thought had almost wrecked his brain. He faced her squarely. "Lorna, let us understand each other," he said. "We shall be very happy together. But never again, as you value my sanity, or your own, must you question me on that point."

She saw that within his eyes which caused her to answer at once: "I promise, darling!" And she kept her word.

Norvell Sands never recovered his reason. He died not long after, confined to a straight-jacket, screaming unutterable things, which were rightly put down as the tragic ravings of a madman. Yet even the attendants, inured as they were to such things, blanched and made haste to cover his poor, tortured face with the muffling shroud.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.