RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, December 1937,

with "City Of The Rocket Horde"

A hundred feet below the metal floor glistened.

Three Musketeers of Three Ages—

A sequel to "Past, Present and Future!"

THREE MEN, heirs of different ages, clad in different habits, united only in a common bond of aloofness, stood motionless on the crest of the ridge, staring at that which lay in the mighty valley beneath them.

For six months since their escape from the neutron-walled city of Hispan they had struggled doggedly over a dead world, forcing their way through trackless forests, ripped by brambles, stung by venomous insects, wading innumerable streams, freezing in the snows of mountain tops, stewing in steamy swamps and jungles. Faces always to the south, steadily, grimly, the last faint hope slipping quietly beneath their aching feet.

Sam Ward, American, erstwhile member of the twentieth century, led the way. He alone of the trio knew the jungle, its savage ways and secrets; he alone knew the geography of the vast continent into which they pushed, a continent that had once been mapped as South America.

Kleon, the Greek, young and cleanly limbed as a god, plodded along steadily in his Macedonian armor, gripping his javelin and short, broad-edged sword with an ever fiercer grip. He had marched with Alexander into Asia; would he now complain of this new and more terrifying wilderness?

Beltan, Olgarch of Hispan, tawny of hair and smiling of mein, suffered the most. His purple garment of woven threads, caught up at the waist, was not adapted to jungle traveling. Nor was Beltan himself, for that matter. Within the immured Levels of Hispan there had been no tearing branches, no blazing sun, no sucking mire. Even the knowledge of these things had been vague and but a legend of ancient days; to be broken only by the strange apparition of these two sleepers from mythical and disparate times—his comrades now.

Yet he made no complaint, nor was he sorry. A sense of freedom, of individuality unknown before, pervaded him and soothed aching muscles and torn flesh. He had been an Olgarch of the ninety-eighth century, the apex of a delicately balanced, if restricted civilization, far superior to the others in knowledge and power. Yet from their very first appearance he had envied these primitives, themselves separated by two thousand years of time—their gusto, their independence, their purposefulness.

As the days slipped into weeks and the weeks into months on their endless trek, Sam Ward had grown more and more uneasy. He had found for them the game that slunk in the jungles, strange animals dimly resembling the ones he had known, yet altered much by environment and eight thousand years of man-free evolution. Sometimes he brought them down with crashing bullets from his Colt forty-five, sometimes Beltan unleashed his blue electric bolts, but more often they relied on the primitive javelin of Kleon. Both bullets and bolts were irreplaceable, and who knew when they might have desperate need of them?

Beltan had grimaced at first at the strange taste of meat, bloodied with stricken life, cooked over fires started by the convex glass of Sam's wrist watch or by husbanded matches he had found in his khaki pockets; for the Olgarch was accustomed to synthetic pellets of food. Nevertheless he held his peace and ate with the others.

SAM steered south as well as he could. It was simple enough through the narrow neck of what had once been Central America—the moveless oceans on either side charted the way; but, once plunged into the vast southern continent, it was a different matter.

His first great shock came as they lunged blindly through what he calculated must have been the Panama Canal. No vestige remained of that mighty engineering gash, no sign that it had ever existed. His second came as they skirted the northwestern coast of the continent, where Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, should have been. There was only jungle, vast, interminable.

Despair seized him then. In all their hundreds of miles of weary wandering not once had they come across the sign or spoor of a human being, or of human work in any form. Earth seemed in truth a dead planet, swept clean of humankind, of human civilization.

He called a council of war. "It seems," he told them dully, "that the legends were correct. Earth is sterile, shorn of mankind, except for the single neutron-enclosed city of Hispan. The cataclysm—comet, runaway planet, or whatever it was—did its work thoroughly. We cannot go on forever in a hopeless quest. The problem now is—what shall we do?"

Kleon leaned on his javelin, wiped the sweat from his fair brow. "If only we had some women," he said speculatively, "we might re-colonize the earth. Even so did my Athenian comrades on the shores of the Euxine and beyond the Pillars of Hercules."

Sam grinned without mirth. "But there are no women," he retorted. "Only three damn fool males whose very processes of thought are different. What do you say, Beltan?"

The Olgarch was deadly tired. His aristocratic face was pale and drawn with unaccustomed hardship. But there was no droop to his proud head, no halt to his careless smile. "I say," he replied calmly, "go ahead. I regret nothing; not even if the world is as sterile as our tales have told. Freedom, death itself is preferable to the purposeless, stifling luxuries of Hispan. You, Kleon, spoke once of Odysseus sailing beyond the bath of all the stars; you, Sam Ward, enlivened the way with stories of men who breasted the frozen wastes in search of the unexplored. Shall we three, at this far later date, be less indomitable than those men of an earlier day?"

Sam Ward's smile widened. The chill that had invaded his being, fled. These were men after his own heart. Three against the gods; three against a desolate planet! Three men, diverse in thought and time, yet animated by the basic courage that had originally brought mankind up from the brute.

They ate in silence the strange webfooted animal that looked like a small deer and tasted like wild duck. They stared at the great flooding river that made an impassable barrier to the east—it must be the Orinoco, Sam decided. Then they tightened their belts and started once more, this time to the southwest. On the Pacific coast, perhaps...

For weeks they climbed painfully the mighty surge of the Andes; up, ever up, to the very roof of the world. And nowhere a sign that human beings had been; nowhere a sign that they had ever existed.

Then, suddenly, they had crested the final ridge, and the sun, curiously tilted to the north, threw long lances of flame into the circular bowl of the valley beneath, disclosed a staggering sight.

THE DEPRESSION, three thousand feet deep, was as smooth as a ballroom floor. Within the mighty round of the upthrusting ramparts it extended, geometrically circular, wrinkleless, shining with a hard bright luster of its own.

"Why, it's artificial!" Sam gasped. "The product of man's handiwork, of a race of engineers beyond all twentieth century conceptions."

"Of course it is," commented Beltan with a little frown. "Only—what has happened to the people who leveled the valley, and coated it with that strange substance?"

"Dead!" Kleon asserted. He picked up a massive rock, heaved it out over the perpendicular cliff on which they stood. "See!"

Breathless, they watched its downward flight. Seconds of tremendous acceleration, of rushing sound into the yawning abyss. Then it struck, bounded high into the air, bounced again and again like a rubber ball on elastic ice.

Moments later came the waves of impact; Bell-like tones, lambent with a ringing hardness. But not the slightest spatter or chipping of the lucent substance, not a dent in its surface; though the falling stone had weighed goodly pounds and the energy of impact had been terrific.

Beltan's eyes widened. "Stellene crystals!" he avowed with a certain admiration, "A crystallized alloy of a dozen different metals. Our technicians in Hispan have barely achieved laboratory samples as yet. Harder than anything on earth except our neutron packs, and infinitely more workable. The race that built that surface was well advanced."

But Sam stared with a growing despair. "Nevertheless they are dead and gone, as Kleon says. They——"

The Greek fell back. The keen javelin wabbled in his hand as he pointed it down. "By Zeus and Poseidon!" he stammered. "The valley is moving—up toward us!"

Sam Ward leaned cautiously over the edge, grunting his amazement. Even the Olgarch gripped his electro-blaster with whitened knuckles.

There was no question about it now. At first the movement had been almost imperceptible, visible only to Kleon's eagle eyes. But now it was accelerating.

The whole valley floor, five miles in diameter, was ascending swiftly, smoothly.

Out of the earth it came, cylindrical, shining, lifting upward to the three crouching men on the edge of the encircling mountains. Like an unimaginably huge piston, sleek and glistening, spurting out of the sleeve of the enveloping jacket.

It swallowed up the intervening space; it obliterated the tremendous valley beneath; it rose to engulf the frowning ramparts of the Andes. Barely a hundred feet below the paralyzed adventurers the vast hard piston came to a noiseless, gliding halt. The sun beat upon its crystalline surface, disclosed nothing. Featureless, unstirring, it reflected the searching rays.

"By the nine darts of Phoebus," Kleon swore, "this needs investigation. Wait for me, my friends, while I go and see——"

Sam's sinewy fingers darted out, caught at his armored shoulder just in time. "Just a moment!" he whispered, "There is something moving."

There was!

THE HITHERTO quiescent surface seemed to blow up into a maze of gigantic bubbles. Great hemispheres, iridescent, rising swiftly, thinning out to sheer transparency.

"I never knew that stellene crystals could do that—" Beltan started, and stopped.

For, with little soundless puffs, the glittering surfaces exploded, and a single mighty shout went crashing through the mountains.

"Harg!"

A hundred thousand men stood stiffly on the inner surface of the lifted valley, in concentric groups of a hundred each, their blond, fanatic faces uptilted to the sun, their left arms raised at similar angles, palms wide, thumbs out; right hands gripping perpendicular lances of tubular metal, tipped by bulbs of stellene crystal.

Again the mighty shout went rocketing and reverberating through the jagged hills.

"Harg!"

"Another city," said the Olgarch. his face working strangely, "and alive! Then the legends were wrong, promulgated by our ancestors to keep us intact within the impregnable walls of Hispan. But what manner of civilization is this——"

"Don't let them see you," Sam rasped. "We had better wait——"

"By Ares, God of War!" grunted Kleon. "They are soldiers, and of a discipline beyond Alexander's phalanx. With men like that——"

The three men crouched behind a jutting rock, peeped down upon the amazing scene. Sam Ward's face was furrowed with unpleasant thought; they had found what they had sought—another city, survivor of the ancient cataclysm, and peopled by human beings—but he did not like what he saw.

The soldiers were gaudily, fantastically accoutered. Dazzling green were they uniforms, faced with brilliant yellows. Fierce blond faces, cast in similar mold, surmounted by peaked helmets of gold, from which long plumes waved in martial sweep. Blond hair cascaded from underneath the helmets, and waxed mustachios swept upward to glistening points.

One countenance was like another, aflame with like ecstatic frenzy. A third time the great cry lanced out from a hundred thousand throats, while red spurts of sizzling flame crashed from the uplifted stellene tips.

"Harg!"

The concussion knocked the three men from different ages flat on their faces, blasted and thundered around the cupping mountains. The atmosphere blazed with disintegrating atoms; flamed with released energy. A vagrant bolt from a stellene tube licked at the overhang behind which they crouched. A moment it glowed cherry red, then it billowed out into a ruin of flaring gases.

Sam blinked, choked, and shoved his comrades back to safety with flailing arms. Six inches closer, and their saga would have ended—abruptly.

THE GREEK, face blackened with the smoke of disintegration, leaped to his feet. Rage twisted his features. He dropped his javelin, tugged at his Macedonian sword. "By Heracles," he howled, "if they wish war——"

The Olgarch's sensitive hand clamped on his shoulder. Smudged with flying dirt though his features were, he had not lost his aristocratic calm.

"They do not even know you exist, my Kleon," he said with a wry smile. "It was a stray blast that almost snuffed out our lives. Besides, your primitive weapon is but a mockery to those stellene-tipped lances." He nodded. "Yes, even my electro-blaster has not their range of destruction." Sam lifted himself up, felt tenderly of his bruised face. His grin was a painful sight. "And as for my puny Colt," he said sourly, "it's wholly outclassed. These babies have weapons, and manpower, and—worst of all—a driving fanaticism. But what does it mean?"

Beltan edged cautiously to the precipice again. "Look!" he cried. "They have gone mad! They are dancing and twisting in senseless fashion."

Sam was at his side in an instant; then he grinned in spite of his unease. "In my day, Beltan," he observed, "those evolutions, on a smaller, tamer scale, were considered the height of good sense. They are army maneuvers."

It was a fantastic sight! A hundred thousand gaudily uniformed men, lifting right legs simultaneously in stiff-kneed formation, thrusting stellene tubes straight out before them at exact angles, widening their dense-packed clusters in concentric circles, interpenetrating their ranks like opposing ripples in a pond, wheeling into the most complicated patterns, shouting hoarsely their interminable cry:

"Harg!"

As they wove and interwove, they danced stiff little steps, swayed first to the right, then to the left—-for all the world, thought Sam, like posturing penguins—their plumes streaming in the wind of their own contriving, their faces set in a single pattern, harsh, fanatical, intent.

Suddenly they fell away, ebbed from the center, lifted their tubular lances high, raised a shout that made all former ones sound like a futile whisper: "Harg! Hanso!"

"Look at that!" whispered Kleon. Within the central space another bubble grew swiftly, higher, wider, glowing with rainbow hues, until its curve was almost abreast of the astounded comrades. Then it shimmered into quiescence, a sheer, transparent dome blown of molecular-thin stellene.

Within its shifting hues a two-stepped dais appeared. On the higher step stood a man—short, dark, sallow-skinned, black hair cropped close to bullet head, clean shaven. On the lower step two others flanked him, likewise short of stature, mouse-colored, with bristling toothbrush mustaches on their upper lips. All three were clad in dark gray uniforms, unrelieved. But on the tunic of the upraised figure three red circles interlocked like the links of a chain.

Alike their countenances were sharp, dynamic; alike their arms lifted in an answering salute; alike their jaws jutted their aggressive surge and their eyes bulged with fanatic lights, but it was the solitary apex of the triangle who cried out in a high-pitched voice:

"Harg!"

"That," observed Sam with frowning concentration, "must be Hanso, Leader, Duce. Fuehrer, Kingfish, or what have you of this latter-day Totalitarian State."

"Eh. what's that?" the Olgarch asked blankly.

Kleon looked bewildered. "You use words, Sam Ward, that hold no meaning."

"Skip it," he growled, "and listen."

Hanso was speaking, head thrust back in studied pose. His voice soared, filled the vast inclosure with clear-cut, rushing sound through some strange amplifying power of the stellene bubble in which he was enclosed.

"Soldiers of Harg," he orated, "the state is proud of you; I, Hanso, am proud of you. A thousand times have I seen you march and countermarch in intricate evolutions, yet never have I seen you perform with such skill, such precision, such magnificent gusto as you have done to-day. Nay, I shall go further. Never in the long history of Harg, in all the combined eras of former Hansos, has there been such a marvelous massing of warriors, invincible in their mighty array, armed at all points with devotion to their glorious city, ready as you are to die, if need be, that the State may live!"

English was his speech, slurred and rotund, stressing the vowels and pronouncing those usually silent; yet intelligible alike to Sam Ward, man of the twentieth century, Beltan, Olgarch of the ninety-eighth era, and even to Kleon, Greek of Alexander's time, because he had donned the inducto-learner in Hispan.

THE MAN paused, and fanaticism swept like a flame over the upturned faces before him. Hysterically they crashed out: "Harg! Hanso!"

"Eight thousand years have made little difference," Sam muttered cryptically.

"I don't understand this at all," Beltan said in some bewilderment. "Soldiers—a hundred thousand of them—armed with terrible weapons—obedient to Hanso's will, trained for what? What enemy have they to fear? We have found no other city in all our wanderings. Only Hispan exists, and of that they know nothing, I am sure."

Sam stared down with narrowed eyes. "It is a logical development," he said slowly, "of forces already at work back in our own time. Originally, no doubt, when the cities drew away from each other and formed bitterly nationalistic states of their own, the fascist city of Harg glorified militarism for a triple purpose; conquest, repression of discontent at home, and as a solution for unemployment.

"When the alleged cataclysm of your legend, or the inevitable result of long-continued isolation, brought forgetfulness to Hispan and Harg alike that other states and peoples existed on earth, the vast soldiery nevertheless remained. The thought of conquest was eradicated, but the other purposes of an army remained. Doubtless discontent was suppressed by insistent propaganda; but, with the march of science and technological improvements, unemployment increased. The army remained; if anything, had to be expanded."

"But what a waste!" Beltan protested. "In Hispan we require no army. Nor have we any problem of surplus population. Surely Harg is sufficiently advanced to control its birth rate according to its needs."

"The soldier's trade," interposed Kleon haughtily, "is the noblest trade of all. The mere practice with weapons—man's weapons, that is, like the sword, the shield and javelin, and not such cowardly things as kill at a distance—the ordered evolutions, the discipline to mind and body, the inurement to hardships, make the man something higher than the slinking beast. The god-like Plato himself placed the warrior class next only to the philosophers in his ideal State."

"Behold ten thousand years of evolution," Sam grinned affectionately at the handsome Greek. "A complete cycle that returns on itself. In Hispan Kleon felt kinship to the Olgarchs; and here before this strange city of Harg he makes his apologia for the totalitarian State. I think there is Spartan blood in his veins as well as the more subtle Athenian."

Kleon scowled angrily. He took this jesting in ill part. But the Olgarch stayed the gathering storm with his exclamation. "See, my friends. Something else is about to take place."

Hanso's voice resounded in the amplifying crystal. "And now," he thundered, "for the last, the ultimate maneuver. Take off, brave soldiers of Harg. Soar and wheel like birds in the sky; prepare against the Day!"

The three watchers gasped.

Around each motionless soldier an elongated bubble grew, lifting paper thinness from the stellene surface, rising rapidly, enfolding him in a sausage-like transparency. A hundred thousand airy bubbles, swaying gently in the wind, each with green and yellow-uniformed warrior enclosed, armed with stellene weapon, and filled with oxygen from a generating pack strapped to his back.

A moment they swayed, held only to the surface by a taper of molecular stellene. Then, at a signal from Hanso, thin streamers of fire licked out from tiny capsules of fuel attached like spurs to each man's boots. The tapers burst with little pops. The mountains filled with soft roaring sounds. The flames lengthened, shifted from red to blue dazzlements.

A hundred thousand elongated bubbles, and a hundred thousand men, catapulted upward to the sky, high above the looming Andes, straight into the sun that was directly overhead. Higher, higher, until they were but remote specks in the blue, and the heavens seemed to be aflame with meteor trails.

"Good God!" Sam ejaculated. "Individual rockets! Things that we were just beginning to play with in our time."

Kleon knew no fear, yet he fell back. "Icarus come to life again!" he breathed.

Only Beltan maintained a faintly contemptuous calm. "Crude affairs," he observed. "Hispan discarded rockets a thousand years ago., We tap earth's electro-magnetic fields for our power."

Sam squinted upward. "Nevertheless," he muttered, "a terrible weapon in the hands of a totalitarian state. Yet to what end? Obviously Harg believes itself the only city remaining on earth. Why then this martial upkeep; these senseless, complicated maneuvers?"

He interrupted himself excitedly. "I have it," he cried. "A Fascist state exists only for dreams of conquest. Only so can the leaders justify themselves, their ruthless control, to the mass of their people. But Earth seems sterile. Perhaps a hasty expedition has so reported. By a stroke of genius Hanso and his predecessors have turned their subjects' attention to the skies. Beyond lie other worlds. Mars, Venus, the satellites of Jupiter! In my day we thought them inhabited. Very likely they are. What greater fillip to enthusiasm, to present contentment, than to raise their eyes to the heavens, to show them illimitable vistas of glorious conquest?"

Already the rocketing army was but a mere tracery of darting fires. It had burst the bounds of earth's atmosphere, had catapulted into outer space.

"An insane ambition," Beltan said. "Even should Harg succeed in reaching Mars, what benefit would such an alien conquest be?"

Sam grinned. "I could answer that by asking you what benefit the workers of your Hispan derive from their lives."

The Olgarch shook his head. "I preferred to share your hardships," he remarked quietly, "rather than remain."

Kleon, the Greek, cried impatiently: "Neither of you understand. I marched with Alexander into Asia to bring the blessings of Greek civilization to the barbarians. When we reached India there were tears in his eyes. He had achieved the ocean, the limits of the world. He sighed for more worlds to conquer. Had he but known——"

Down from the heavens they came, swooping with furious acceleration. It was spectacular; it was awe-inspiring. The sky seemed to be ablaze with cometary fires.

THEN the bubbles took shape and form. Glittering transparencies, each with its green and yellow occupant, stellene-tipped tube extended before him in triumph. A mighty armada such as old Earth had never before witnessed in millions of years of distorted evolution.

They grew on the sight. The three men stood motionless, shielding their eyes from the blinding vision. So intent were they on the fiery rain they did not realize that they had incautiously moved closer to the precipitous overhang; that they were erect and exposed to the view of the uplifted surface of Harg, not a hundred feet beneath.

Hanso saw them; so did his silent compeers. Astonishment darkened his sallow face. His eyes bulged even more than before. His foot moved over banked buttons. It pressed. At once a thin, keen whistle shrilled through the air, penetrated the throbbing roar of a hundred thousand shooting rockets.

Sam jumped at the sound, cried: "Duck for cover!" But it was too late.

Already battalions had swerved, were plummeting straight for them like hawks on their prey. In a trice they were enringed by settling stellene bubbles, through whose sheerness blond, fanatic faces stared at them, and bulb-tipped tubes pointed threateningly.

Kleon lifted his gleaming shield involuntarily, held his javelin ready-for the strike. Sam Ward's hand leaped for his bolstered gun. But Beltan made no move for the electro-blaster that dangled at his side. His voice rose in warning; calm, unperturbed.

"We would be dead men before we could kill even one of them. It is wiser to let them take us to their master, Hanso."

Sam groaned, and took his hand from gun butt. The Olgarch was talking sense. Only Kleon lowered his javelin with resentful gesture. It was not in his nature to surrender tamely.

"Bring them to me," floated up the sharp, high-pitched voice of Hanso.

The stellene tubes thrust strangely through the enveloping bubbles, prodded the three captives roughly toward the edge. Sam swore in sheer amazement. The transparent coverings seemed to offer no resistance to the passage, yet when he accidentally stumbled against a soldier, the outer surface was hard as stone to touch.

"That," murmured Beltan, "seems to be a property of the stellene alloy. Our technicians found that out even in their tiny samples. It is a uni-way crystal. The molecules lie in polar planes. On one side they form an impenetrable lattice of diamond-hard surface, but on the other their planes diverge so as to admit exit—but no entrance."

"I get it," Sam nodded. "Something like the rat traps or lobster traps of my time. It is easy to get in, but impossible to get out."

Kleon staggered suddenly back. "By Zeus and Poseidon, do these fellows wish to cast us over the cliff?"

They had been prodded to the very edge, and the icy tubes were relentless in the small of their backs. Beltan smiled his slow, calm smile. "Do not fear, friend Kleon," he told him. "Allow yourself to drop to the surface of Harg. You will not be harmed."

Suiting action to words, he stepped over, whizzed out of sight. Sam shivered, followed. The Greek gaped, called on his gods, and leaped bravely.

It was a sickening drop. Yet even as they seemed about to smash upon the hard, bright surface, Hanso pressed another button. Waves of force swirled up to meet them, cushioned their fall to a gentle, feathery descent. They stood upright, unharmed, before the gigantic bubble that housed Hanso and his two associates, while all around them, immobile once more, their space-protective stellene shells removed, clustered the huge army of Harg.

The eyes of Hanso glittered upon them. "Who are you three," he demanded, "similar in some respects to the men of Harg, yet strangely different, even from each other? How have you come across the outer wastes where no being has come since time immemorial?" He leaned forward slightly as he spoke, and a strained eagerness showed in his sharpened features.

"It is a long story," Sam started slowly, fumbling for delay. He did not like that sense of strain, of eager waiting for his answer. But Beltan added quietly, "And a strange one, Hanso. I am Beltan, an Olgarch of Hispan, a city to the north. We, too, had thought ourselves the sole survivors of the human race since the cataclysm of the twenty-seventh century. My comrades are sleepers from forgotten times. Kleon, he in the once glittering armor, now rusted over with the steam of many jungles, was born ten thousand years ago. Somehow he found the secret of arrested animation, immured himself for transport into the future. This other, Sam Ward, whose tongue was the root of yours and mine as well, lived in the twentieth century. By accident he stumbled on the secret place of Kleon, himself succumbed to the radium-impregnated gases. He slept on with the other.

"Digging in the foundation of Hispan, we found the sleepers. We had thought the outer world a sterile waste, inimical to human life. They thought differently. By their unwonted freedom of tongue in our carefully balanced city, they forfeited their lives. I, myself, was weary of inanity, of monotonous nothingness. I cast my lot with them, and we escaped. For months we have wandered, coming to believe the legends correct—that Hispan alone existed on all the earth. Now we have come to your city of Harg. There are no others."

SAM RELAXED. He had tried by surreptitious means to stop the Olgarch in his narration; and he had failed. Now he understood his seeming blundering. Hanso was no fool. No possible evasions would have held from him the knowledge that there was another existing civilization on the face of the Earth. By his obvious frankness in disclosing the whereabouts of the neutron-enclosed city of Hispan, Beltan had cleverly given the ring of truth to his last assertion. And, in fact, as far as the wanderers knew, there was no other city.

A shadow clouded Hanso's face. His eyes turned to his associates. "You have heard. Vardu, and you, Balan. These men have unfolded a strange tale."

Balan, to the left, was the slighter of the two. He glanced meaningly at Hanso. "There is at least this city of Hispan to be investigated, High Magnificence."

"It will prove of little avail," Beltan interposed calmly. "Hispan has been at peace for thousands of years; it has no soldier class. Nor does it require one. Its neutron walls protect it from even your mightiest weapons."

Hanso's eyes flicked out on his motionless warriors, their ominous array.

"That remains to be seen," he murmured.

Vardu, to his right, was taller, swarthy, grim of visage. His mustache bristled coarsely. "I think," he said reflectively, "since there is a Hispan where we knew of none, there may be other cities." A shrewd smile flitted over his countenance. "Perhaps they are not as well shielded from attack as the city described by this stranger."

"There are no others," Sam burst in positively.

"How do you know?" snapped Vardu. "Granted that you tell the truth, have you covered all of earth in your wanderings?"

"No, but——"

"Enough," decided Hanso. "We shall discuss these things later. In the meantime provision must be made for our guests within the city of Harg. Balan, that will be your task."

"Does that mean we are your prisoners?" Kleon demanded boldly.

Hanso's eyes glinted with little lights. "Our guests, I said—until we determine otherwise."

Balan moved out toward them. He passed through the thin-blown stellene as if it did not exist. Yet behind him, as he emerged, the transparent wall seemed intact, undisturbed.

"Come!" he said, and led them toward an open area. Even as they stood motionless at his command, Sam noted the fine circular line in the otherwise smooth surface around them. Balan pressed with his foot.

Swiftly, smoothly, the circle descended into the depths; above, the roof swirled unbroken into place. They were in a hollow shaft, dropping downward with breathtaking velocity. Down into the very heart of the many-tiered city of Harg. But the walls were opaque, disclosing nothing of the crowded life that lay beyond. The milky substance blurred with the speed of their descent.

Sam glanced surreptitiously at their guide. Balan had seemed to him the most human-looking one of the three, even as Vardu appeared the one most to be feared, though he was subordinate to Hanso. Balan caught his glance, smiled. It was not a pleasant smile, yet it was not too forbidding.

Encouraged, Sam asked questions. "It was an amazing sight to us," he observed, "to see Harg emerge suddenly from the flat level of the valley. In the time from which I come, no such feat would have been possible to all the resources of our science."

BALAN looked pleased. He was not immune to flattery. "The scientists of Harg are the best in the universe," he admitted. "They are under my control, even as the warriors belong to Vardu, and the providers to Gama, whom you have not seen. Of course, His Magnificence, Hanso, is the All-High. But the method by which Harg is lifted into the mountains, and retracted again into the bowels of the earth, is simple enough. It was evolved in the distant past, before the smash-up, when Harg was still a city-state enringed by hostile nations intent on changing our beneficent institutions. We were small then, and lacking in manpower. It was necessary to hide from the overpowering armies of our enemies, to escape destruction. This was in the rule of the first Hanso. Our scientists labored long on the problem, with that undeviating devotion which has always been Harg's boast.

"They solved it by burrowing underground, by building our city afresh within the bowels of the earth in the form of a tall, many-tiered cylinder. At first the structure was crude, but later, with the discovery of stellene, and its many wonderful properties, the city was rebuilt entirely of that material. Thereby we escaped the notice of our enemies, and prospered mightily under the beneficent guidance of a line of Hansos and the blessings of our ordered state, where each man and each woman knows exactly what he or she must contribute to the general total, and labors willingly and gladly to that end."

"But you haven't answered my question about how Harg is raised and lowered," Sam protested.

"Oh, that!" said Balan. "That is very simple. Purely a matter of hydraulics. We rest upon a huge cylinder that taps an underground lake. When we wish to rise into the outer air, pressure upon the lake forces the water into the cylinder, is multiplied by the surface area of the piston within, and lifts us up the outer walls. When we wish to descend, we permit the water to return to the lake."

Sam nodded. "We, too, had hydraulic elevators based upon the same principle in our day," he observed. "But the total weight of your underground city runs to millions of tons. That requires an initial pressure of enormous proportions. Where do you get your power from?"

"We tap the inner fires of earth," Balan explained. "A bore runs almost twenty miles down, contacts a pocket of lava. A lock arrangement permits this to rise swiftly to the lake. The water converts instantly to steam, expands with unimaginable pressure. On withdrawal of the lava, it cools, condenses, and turns to water again."

"I would like, if possible," said Beltan suddenly, "to see those whom you call the providers. No doubt they correspond to the workers of Hispan. We have only three classes in all—the olgarchs, the technicians, corresponding to your scientists, and the workers. You have four, if we count the four rulers, you named as a class."

"There are more than four of us," Balan corrected. "I mentioned only the highest overseers. But there are about five hundred in all, whose function in the state is to oversee and supervise, to the tiniest degree, every activity, every movement, every thought even. This is to make certain that no one, warrior, provider, scientist, or hetera, disturbs the smooth efficiency of our organic entity."

"The Fascists of our day would have died of envy if they had known of Harg," Sam muttered. "They but blundered toward what is here in full flower."

But Kleon, weary of these metaphysical discussions, had pricked up his ears at a name to which the Hargian overseer had casually alluded.

"Hetera!" he exclaimed. "That has a familiar ring! What or who are they?"

BALAN scowled. His erstwhile good nature evaporated. He bit his tongue in manifest vexation, as though he had unwittingly let something slip. "You are mistaken, stranger who have slept for ten thousand years, I mentioned no such creatures."

"But you did," the Greek countered with reckless insistence. "Now in my day the Heterse were——"

"I am not interested in your silly tales," the overseer said savagely. "Your wits have been woolgathering during your lengthy torpor."

The Greek flushed. He jerked for his javelin. Balan grinned sourly, plucked at an inconspicuous button on his gray tunic.

The Olgarch thrust himself between them with hasty words, while Sam, cursing the trigger-like imprudence of the Greek, streaked for his gun.

"Kleon!" said Beltan with stern impatience, "you are a fool! Friend Balan is quite right. He never mentioned that outlandish word whose very sound I have already forgotten."

"But—" the other protested in bewilderment. "I was certain——"

The Olgarch turned swiftly to the Hargian. "I repeat," he said silkily, "if it be not forbidden, I would like to see your civilization. It seems even superior to that of Hispan, my native city."

Slowly Balan dropped his fingers from the button. His dark passion faded under the subtle flattery; he even smiled. Sam breathed easily again. Once more Beltan had shown quick-wittedness. "Your tongue," he growled low to Kleon, "will still get us into trouble."

"Of course," bragged the Hargian. "Our state is perfect; it would be impossible for any other to surpass perfection." He hesitated a moment. "There is no reason," he decided at last, "why you may not see parts of Harg." He grinned unpleasantly. "There is small chance in any event that Hanso will permit you to leave us soon."

THEY HAD BRAKED soundlessly to a halt at the very bottom of the shaft, three thousand feet within the bowels of the earth. Sam could hear the surge of subterranean fires, the thin hiss of steam, the muted rush of falling water.

"The maneuvers are over," Balan explained, "and the city is dropping back into the earth. Just in case," he added significantly, "there are others of your kind scouting over the mountains. They could pass a thousand times and never know that Harg lies hidden in this valley. Now I shall first take you to the section of the providers."

He touched the second inconspicuous button on his tunic. It glowed redly. A section of the enclosing wall leaped into eerie life with answering glow, then faded into glassy transparency. They walked through, and the opaqueness merged into position behind them. But even as Sam stared sharply around, his thoughts were troubled. He was mulling over the hints which these overseers, the apex of the power pyramid for this totalitarian state, had dropped. They had been preparing for the Day! Those hundred thousand fanatical warriors in their gaudy uniforms, with their rocket shells, and terrible stellene weapons, were not training for mere show. Before their arrival, that martial lust for conquest had been directed toward outer space, toward the distant planets; but now that they knew that at least one city existed on Earth, now that the shrewder Vardu suspected others as well, Harg would not rest content. The very nature of a Fascist regime forbade peaceful relations with neighboring states. And the three wanderers, the only three in all the world who might spread warning of impending attack to possible unsuspecting civilizations, were helpless prisoners. Sam had no illusions about their status. The term guest employed by Hanso was wholly ironic.

The section of the providers filled all the lower tiers. They tended the hydraulic pistons, the apparatus of the lava locks; they dug through shafts into the surrounding rock for the precious metals and minerals required for their economy; they looked like huge blond gnomes before the blazing atom crushers; they tilled the lush beds of dissociated food stuffs.

"Matrices, really," Balan explained. "What looks like soil are carefully prepared beds of essential elements." He pointed to huge parabaloid reflectors overhead, from which multicolored rays beat steadily upon the artificial soil. "We no longer have to eat the coarse bulk that nature provides in animal and plant stuffs in order to gain the tiny residuum of required essences. Here they are grown at will, activated by the special intensities of the reflectors. The thirty-two different types of vitamins, the seventy-five hormones, chloresterols, sugars, purified proteins, hemoglobins, are crystallized in their essential states. The diets are rigidly worked out by our scientists. Each dweller in Harg receives the exact amount, the exact proportions suitable for his body economy—no more, no less. That is efficiency."

THE PROVIDERS did not lift their heads from their tasks at the intrusion of the strangers. Curiosity was obviously not permitted them, nor cessation from work. They were giants, a uniform six-foot, three inches in height, powerful of body, knotted with muscles. Not a one of them but could crush Sam or Beltan or Kleon in contemptuous hug. But their broad blond faces were vacuous to a degree; their eyes without luster. Men and women worked side by side, dressed alike, performed the same strenuous tasks.

"They seem to work without ceasing," Beltan observed. "Yet they are brawnier and stronger by far than the workers of Hispan. What is there to prevent them from revolting against their overseers?" He pointed to the few small, dark, quick-eyed men who strolled leisurely through their innumerable ranks, pausing only to give an occasional sharp command which was received with eager subservience.

Balan looked surprised. "Revolt?" he echoed. "There never has been any. There couldn't be. Each member of Harg knows his exact status in the unitary organism of the state; any change is unthinkable. Besides, they are all bred—workers, scientists, warriors, yes, even ourselves as overseers—for their especial niche. There is no guesswork."

"You mean birth control?" Sam asked.

The Hargian smiled. "Pre-birth control," he retorted. "But you shall see that later in the laboratories of the scientists. But don't think that there is any repression. We need none. Everyone is content. For example, the providers are in three shifts—a working shift, a sleeping shift, and a playing shift. I'll show you how they play."

He led them by swift elevator to another tier. This was a huge playing field, extending over the entire round of the underground city. It swarmed with shouting, shrieking providers, nude except for a loin cloth about their middles.

There were running tracks, gymnastic apparatus of intricate design, what seemed to be a football field except that there were hundreds on each side, and the ball was an illuminated sphere that floated in the air like a balloon. The players swung overhead on flying rings, kicked at the ball with their feet, pushed it along with wriggling bodies toward the goal, piled up in inextricable masses high in the air, from which the lighted globe would suddenly emerge with violent propulsion; they fell in droves to the padded floor beneath, and swarmed up ladders again to seek new grips on the hurtling rings.

"Wow!" breathed Sam, as he watched the semi-naked players fall with bone-jarring thumps, heard the savage crack of brawny fists on intervening skulls, saw the blood stream from sweaty, pulsing bodies. "And we used to think ordinary football rough going! But don't they get maimed or killed?"

"Often," Balan said indifferently. "It does not matter. We can always incubate more. And it hardens them, makes them immune to the wasting labor of the mine shafts, the blazing heat of the atom crushers. They love it."

One of the players flew suddenly out of the overhead melee, dropped with a sickening thud to the ground. Blood covered the battered face, a leg was twisted underneath. Then the wounded player lifted himself painfully, crawled away, the right leg dragging uselessly behind. But the game did not stop its furious pace, nor was any attention paid to the sufferer.

SAM jerked forward with a little oath. He had seen certain indications on the half-nude body. "Why, that's a woman," he gasped, "and her leg is broken."

Balan shrugged. "What of it?" he said. "The providers work and play alike, women and men. There is no love, no mating. They are sterile. As for the one who is hurt, she will crawl to the medical tier. If her wounds heal properly, she returns to her tasks; if not, she is liquidated."

"Liquidated?" Sam stood with clenched hands, seeking to still the anger that invaded him. "You mean killed."

"We prefer the former word," the overseer answered. "Each individual in Harg lives only for the greater glory of the whole; once his usefulness is over, he must give way for newer and more vigorous units."

"A horrible philosophy," Sam said slowly.

"Why do you call it horrible?" Kleon asked in surprise. His eyes had glittered approvingly on the brawny, muscular bodies of the contestants, on the rude sports they played. To one side two providers were wrestling. Huge, equally matched. Straining and panting, they clasped each other round the waist, sought to gain the final stranglehold. Suddenly, one shifted his hold, caught the other in a combination head-lock and flying mare. There was a little snapping sound; then the victim whirled high into the air, went crashing to the floor. He remained there, limp, unmoving. But the victor stood proudly erect, seeking praise from the onlookers, displaying the sweaty contours of a nude form.

The victor was a woman!

"At least," continued the Greek with animation, "they develop sound bodies, if not exactly sound minds. Our gymnasia, our Olympic Festivals, our Delian Games, witnessed similar scenes. Men and women competing together, forgetful of their sex in the hard rush of bodies. The Spartans were even more rigorous. Maimings and deaths were not unknown."

"I think we have seen enough of this," the Olgarch said with a certain calm distaste. "In Hispan we do not go in for feats of strength. We think them relics of more primitive eras." Besides, he had noted the withheld anger of Sam, wished to get him away before there was a dangerous explosion. "May we go to the laboratories of the scientists?"

The overseer stared at them superciliously, said: "Very well!"

The section of scientists extended over a dozen tiers. Laboratory on laboratory, each devoted to specified problems. In one, research was proceeding on the efficiency of atomic disintegration; in the next, new uses were being sought for the all-pervading stellene crystals; in the third, red flares of destruction licked interminably between the poles of humming diskoids of revolution; in still another, rocket reactions were carefully studied in test chambers. And everywhere was giant apparatus, bewildering in intricacy, overpowering in size and function, that left Sam gasping. Though he knew something of twentieth century science, this was beyond his depth. As for Kleon, he stared around with a certain disdainful hauteur, as though these things were beneath a Greek trained to arms, to philosophy, and to the surges of the poetic spirit.

Only Beltan was keenly interested, asked clear-cut, intelligent questions of the tending scientists. They were somewhat of a shock to Sam. Slight, pale, spindly-legged, with bulging foreheads and long, delicately adjusted fingers, they bent to their work with undeviating absorption. They answered Beltan with short monosyllables; only sprang to profound attention when Balan, their head overseer, addressed them with curt commands.

Slowly a picture took shape and form in Sam's mind from the maze of experiments. "Your science is tremendously advanced," he admitted, "but it seems entirely on the practical side. I see no theoretic experiments, no attempt to solve the fundamentals of life, of matter, for the sake of pure knowledge."

The Hargian laughed scornfully. "Pure knowledge?" he echoed. "Moonshine, dreamy stuff unworthy of our state. Of what benefit would it be to Harg to discover, for example, that the universe is expanding or contracting? It does not affect our lives, or the future of Harg, one way or another. It never will. We restrict our science to the immediately practical, to the things that will make Harg mightier, more glorious, more efficient. That is the only purpose of science."

"But the things of the spirit," Sam protested. "The desire for the ultimate truth!"

"There is no ultimate truth," Balan retorted rudely, "except the single truth of Harg! All other lesser truths must conform themselves to that one overwhelming fact."

"Here too," Beltan interrupted quietly, as he always did when Sam or Kleon showed argumentativeness, "I see that men and women alike are scientists. I even noted the same among the warriors. Are they also sexless?"

"Certainly. Sex would prove a disturbing factor in the ordered regime of the state. There would be incalculable interruptions, passions, losses of energy. So we sterilize them at birth. It would be much better if we could evolve a wholly neuter gender in the incubating eggs. It would tend toward greater efficiency, would avoid those small periodic weaknesses that come even to our sterilized classes, and curtail their production. So far we have not succeeded; but the work is going on, and I have hopes of an early solution."

"But if you did succeed," Sam argued, "how would you continue to reproduce, to replenish the race?"

BALAN SMILED. "I did not say," he replied with a smug grin, "that the overseers are sterile." Then he stopped short, and shunted them hastily into the final laboratory, "Here," he said, "are the incubators, where the fertilized eggs are molded by properly regulated strengths of cosmic rays to breed the types we desire. Thus there is never a surplus of any class. Births are nicely adjusted to deaths. Or," he added significantly, "we can increase at will the numbers of a particular type—the warrior class, for instance. Adult growth under our forcing machines is achieved within a week."

"Meaning Hispan?" Beltan asked quietly.

"Meaning Hispan, or the planets, or any other state that may exist," Balan retorted unpleasantly.

"I would like to see these forcing machines." Sam moved quickly.

He had heard enough to cause his jaw to harden, his eyes to grow grim and taut. His hand lurked close to his gun. An idea had sprung full-born in his brain. If he could get to those devilish machines, wreck them somehow, he might retard sufficiently the obvious plans of Harg. By their presence he and his comrades had directed attention of this perfected corporative state to the possibility of other civilizations on a supposedly uninhabited earth. The conviction had grown in him that Hispan and Harg were not all; there must be others, unsuspecting, more in line with the evolutionary ideas of the twentieth century. They would be conquered with ruthless force, warped to slavery. He must prevent it, even at the sacrifice of his own life. Perhaps, in the resultant confusion, Beltan and Kleon might effect their escape, give warning.

But even as he moved, a side panel grew transparent, emitted a taller, darker figure. Sinewy fingers dosed around the second tunic button.

"Stay where you are," said a voice.

Sam froze in his tracks. So did the others. Whatever the lethal qualities of the rays that round disk could emit, they realized the power would be sufficient to blast them all out of existence before they could lift a finger.

"That is better," remarked Vardu, overseer of the warriors. His saturnine features turned icily on Balan. "Why were these creatures of an inferior order not confined in the prison chamber, in accordance with the commands of Hanso?" he demanded.

The overseer of the scientists paled.

"But His Magnificence merely said—" he started to protest.

"You do not understand the orders of Hanso," Vardu interrupted brusquely. "It is not the first time."

"Yes, Vardu," Balan said obediently. A sullen hate lurked in the corners of his eyes. Sam, alert for any break, noted the elements of discord between the Hargian Chiefs, noted also that Vardu was the more arrogant, the more powerful.

"Good!" said the taller one. "We understand each other now. Hanso gives commands; I interpret them. Since that is clear, take these alien spies to—"

Through the still open panel another figure emerged. A woman, resplendent in all the trappings of her sex, voluptuous, beautiful.

The sight of her seared through Sam, set his pulses leaping. Dimly he heard Kleon's whispered: "The Goddess Aphrodite!" Even the Olgarch, proudly reserved, gave a queer little gasp.

Her limbs were the hue of rose-petals, warmly curved. A shimmering garment of sheerest thread flowed over her molded form, accentuated rather than concealed the beauty of her body. Her bright golden hair was caught up in a net in which precious jewels glittered like fireflies. Her eyes were wells of blue allure.

SHE moved with a studied grace; her red lips pouted. She had not seen the strangers. "I heard your voices, Vardu and Balan," she said languidly, "raised in quarrel. Since the wall that hems us in was fortunately open, I came to see——"

Vardu recovered himself first. Black anger struggled with a certain leaping boldness in his gaze. "Alanie!" he rasped. "You know you are forbidden to leave your quarters. Go back——"

Alanie surveyed him with an insolent detachment. "I overheard you say to Balan," she said softly, "that the great Hanso gives commands, but that you interpret them. Perhaps Hanso might be interested to hear of that arrangement."

Balan took a sudden step forward. "Why, isn't that so?" he snarled. "Then Vardu——"

"Shut up!" the overseer of the warriors said furiously. He turned on the woman in a cold rage. "You wouldn't dare, Alanie."

"Oh, wouldn't I?" she laughed. "And perhaps I wouldn't mention certain advances which you proposed to me. I, Hanso's mate."

Vardu collapsed. All his arrogance left him; fear crawled in his eyes.

"Alanie! You have mistaken; it is not so."

Her voice cracked out like a whiplash. "Then say no more of my disobedience of the law. I am tired of my immurement with the Hetera. They bore me with their vapid chatter, their aimless waiting for condescending visits. I wish to wander, to see things——"

She turned petulantly, and her eyes widened. She had seen the strangers, themselves transfixed with her beauty. The pulses still hammered in Sam's veins. Hetera! Alanie! Now be understood the meaning of much that had puzzled him. In this state of the future the masses were ruthlessly divested of sex, of all the physical, mental and spiritual overtones that accompany that mighty manifestation of nature. Sex, they had been told, was only a disturbance, an impediment to efficiency.

But hidden from the gaze of Harg was the harem of the overseers—beautiful women, voluptuous beyond belief, ministering to the pleasure and delight of the rulers. Sam knew now the origin of the ova under the cosmic ray machines and in the forcing chambers of the scientists. Even in the twentieth century there had been talk of the possibility of incubation.

Alanie's gaze swept curiously over Sam, lingered a moment on the Olgarch, then fastened with avid fixity on the classic, golden features of the Greek.

"Who are these men?" she asked softly. "And what especially is the name of this one with the face of a superman?" Balan's sallow countenance lit up with a certain triumph at the helpless fury of the chief of the warriors.

"They are aliens to Harg, oh, Alanie!" he volunteered. "They came from that outside world which we had always thought barren of human life. They are named Sam Ward, Beltan, and he of whom you ask especially is Kleon, of ten thousand years ago."

"Kleon!" she rolled the name on her tongue, stared at him with speculative eyes. "I have not seen his like before. He is indeed—a man."

No doubt of that, Sam thought. Compared to the sexless masses of Harg, to the sallow-faced, bulging-eyed masters. Then he glanced warily at his comrade, and received a shock.

KLEON had forgotten him, had forgotten Beltan, had forgotten everything but the beauty of the woman before him. His soul was in his eyes, and his eyes were fixed with a burning intensity upon Alanie.

A sudden fear clutched at Sam's heart. "Kleon!" he rasped. "Be careful! Remember all our hardships together!" Beltan strode swiftly to his side. His tawny hair was an aureole. His careless face was rigid with concern, "Have you lost your wits, oh, Greek? Are you in truth a primitive without reason? Can't you see—?"

But Kleon paid no heed. His glance locked with that of the woman. "Alanie!" he murmured. "You are indeed beautiful."

She smiled a slow, tantalizing smile. Her eyes clung hungrily to his lithe, straight form, his face as cleanly carved as a medallion. "Come with me, Kleon," she whispered.

Vardu crashed forward. "Alanie, are you mad?" he snarled. "You know this is against the law! You know the penalty of disobedience! Get back to quarters before——"

She looked him full in the face, mockingly. "You forget, mighty Vardu," she said with ironic emphasis, "His Magnificence. If I but whispered to him the things I knew——"

His face became an inscrutable mask. "Very well, Alanie. As you wish. Take this alien with you; I shall not hinder you."

"That is better," she laughed. "Now we understand each other. Come, my Kleon."

He went with her, shield and javelin dangling from left hand, sword slapping at his legs. Through the open panel they went, disappeared behind its swift opalescence. Not once did he look back at his comrades, or betray an awareness of their existence.

Beltan's lips were set in a painful smile; sodden despair overwhelmed Sam. He had come to love the Greek; now he had deserted them without a qualm; deserted them for a Hetera, a plaything, a woman of Harg!

Dully he turned at Vardu's harsh command, dully he permitted himself to be herded with the Olgarch into the communications shaft again. The whispered muttering of Vardu and Balan made but little impression—they seemed to have come to some private agreement between themselves—even the swift clouding of the confining walls was an unimportant thing. Kleon had deserted them—that was the sole fact!

But Vardu's sardonic voice ripped him out of his maze. "Everything works into our hands, Balan," he chuckled. "Now that we have joined forces, it will be an easy matter... Do you hurry and inform Hanso of the treachery of Alanie with this primitive stranger. I shall await him in a hidden niche close to the quarters of the Hetera.

"In his fury he will slay them both. Her mouth will be forever stilled. But at the very moment I shall loose on him the needle ray that makes a gaping wound somewhat like that of the javelin in the Greek's hand. I can claim thereafter to the overseers that they slew each other simultaneously. Meanwhile, after your warning to Hanso, you will return and put these others to the death. And I shall marshal my warriors, inform the overseers that the aliens had admitted before they died that there were many other cities over the Earth whose conquest merely awaited the presence of our armies. In their enthusiasm they will forget to question; we shall become Magnificences together; and Harg shall gain new provinces, new slaves."

THEN they were gone, and Sam whirled on Beltan within the confines of the narrow prison cell.

"Did you hear their fiendish scheme?"

Beltan stood quietly by his side. "There is nothing we can do, Sam Ward," he said patiently. "We are helpless within these stellene walls, even though they have overlooked our weapons. Not even my electro-blaster can pierce their substance. Though it hurts me to say so, for I loved him well, Kleon has brought this upon us all."

Sam flung away in anger. "He could not help himself," he exclaimed. "The emotion of love, of overpowering desire, no doubt was bred out of Hispan in the long course of centuries. And no doubt the lack of it helped contribute to the general flatness and tameness of your existence."

The Olgarch brooded on that. "Perhaps you are right, Sam Ward," he said finally. "I have unjustly accused poor Kleon!" Then he smiled. "After all, perhaps he is better off than we. At least he will have had a lovely woman in his arms before he dies; while we—we shall die without that subtle consolation."

But Sam's face was flattened to a transparent strip—a window-like projection, inset within the darker translucency of the all-pervading stellene. Their prison gave on a huge, upward slanting passageway, obviously the chief connecting thoroughfare of Harg, for the transportation of larger masses than the vertical shafts could accommodate.

There seemed an unusual commotion. Giant providers, blond of hair and muscular of body, hurried by in endless streams, bowed under the weight of strange mechanisms, of packed equipment. Warriors marched along with echoing tread, in companies and battalions, right foot up, left foot down, lackluster faces turned each to an exact angle, obeying an invisible will, terrible in their colorless uniformity. Each held erect the stellene weapon that blazed red destruction at a touch.

The great passageway trembled with their march; interior galleries spewed their contents to join the upward moving stream.

"It looks like a vast migration," Beltan commented.

But Sam shook with an indefinable fear. "It is more than that," he declared hoarsely. "It means that the plans of Vardu and his dupe Balan have been successful. It means that Kleon is slain; that Hanso has fallen into the trap. It means that Vardu has assumed control, and has mobilized all of Harg for the Earth-conquest by means of which he seeks to justify his seizure of power to the overseers."

The Olgarch shrugged. But the pain in his eyes belied the lightness of his voice. "If Kleon is dead, so shall we be very soon. As for Earth, we know only of Hispan. And Hispan is impregnable behind its neutron walls."

"Perhaps!" retorted Sam. "Though we do not know the full power of destruction inherent in those stellene rods. But I am convinced there are other civilizations scattered over Earth, hidden, unknown as yet to each other. It is incredible that alone of all man's strivings, his idealism, these two twisted, vicious cities should remain. There must be others, different, more worthy, more in consonance with the trend of upward progress."

"Evolution does not necessarily mean progress," the Olgarch said quietly. "It only requires change—and that may be for the worse. But what can we do to stop the hordes of Harg?"

"Escape! Give warning!"

Beltan smiled. "Easier said than done."

"We escaped from Hispan," Sam said grimly.

"You forget I helped you. Here we have no outside aid."

The American relapsed into gloomy silence. Pie turned his face once more to the dreadful monotony of those inexhaustible hordes on the march, thousands, millions it seemed, steadily streaming to the exterior, spewing out to conquer an unknown planet.

He clenched his hands in helpless wrath. Kleon was lost to them; and now the earth, that had beckoned with strange mysteries, as well. Their own lives were forfeit. Yet there was nothing they could do. Beltan was right. The stellene walls were impenetrable.

THERE WAS a sudden break in the endless lines. A gap in the solid ranks. Balan, overseer of the scientists, strode heavily down the path. A smug, self-satisfied air wreathed his sallow face. His tiny mustache bristled with importance. The warriors, the providers, flattened obsequiously against the walls at his approach. He was of the mighty.

He halted before their prison cell, tugged at the top disk on his gray tunic. It glowed cherry red. Swiftly Sam's hand leaped for his gun; like lightning the Olgarch raised his small electroblaster.

"The fool," whispered Sam through taut lips, "doesn't he know we have weapons? This is our chance, as he enters..."

The prisoning wall glowed, turned transparent. It shimmered into hazy dissolution. Seemingly unaware, Balan stepped through to his fate.

"Now!" rasped Sam. Two diverse weapons of destruction lifted, aimed at the oncoming man. Fingers pressed on...

Sam Ward tried to cry out, couldn't. His finger had tightened—and had frozen in that position. A cold wave surrounded him; made him rigid, immovable. In the grip of a strange paralysis he heard Balan's mocking laugh; saw his hand release the glowing button. The strange light died. By his side Beltan stood as one welded to the floor, the electro-blaster still pointed futilely.

"YOU MUST think me dumb indeed," Balan jeered. "You forget that the science of Harg is the mightiest in the universe. Every word, every whisper from this cell was transmitted by the ether vibrations of the encompassing crystals to a tiny receiver concealed beneath my tunic. I knew of your weapons, was prepared for them with a tight paralysis beam." His brow darkened. "So you think me the dupe of Vardu, eh? You are mistaken. It is true that he thought so too, tried to use me with fair words. But I have not forgotten his former arrogance, nor my hatred for him. It is he who will prove the catspaw. Once everything is accomplished, he will die—unexpectedly; and I shall take over the rule of all Harg." His bulging eyes flamed. "Yes, even the overlordship of Earth, of all the Universe."

His thin hand stole to the second button. Sam shrieked his will against immobile muscles, against locked jaws. Death stared him in the face; sudden, irrevocable.

But the paralysis held. Rigid, eyes fixed in an unblinking stare, he saw the, button twist——

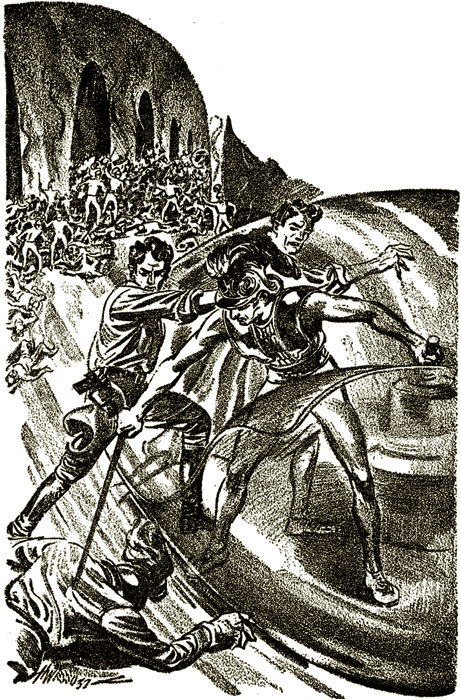

A faint whine whispered up the passageway. It grew to a thunderous roar. Red flame blasted in a long streak, outlined a hurtling, slender vehicle. At reckless speed it came, propelled by jetting rockets.

It speared through the crowded men of Harg like a flaming sword through melting butter; it left death and destruction in its wake. The huge providers, the fierce warriors, howled and flung themselves into the side passages, fleeing the Juggernaut that crushed and blasted out their lives. In seconds the thoroughfare was clear, except for crisped, unrecognizable bodies, the flare and Stench of burning flesh.

A god seemed to ride the fiery steed, a golden-haired god whose face was aflame with battle madness. The rocket vessel catapulted to a halt before the startled overseer. Even as Balan whirled, fingers clutching at the lethal disk, something long and glittering whizzed through the air. The keen point caught him full in the chest. He swerved, staggered, and fell headlong. Bright blood gushed from the gaping hole.

Sam felt swift power flood his limbs once again. "Kleon!" he shouted.

The Greek bent over the hull of his strange vessel, plucked up his javelin in a single motion, grinned. "Hurry, you two," he yelled. "In beside me. Vardu is on my trail."

"But—but—" Sam sputtered. "We thought——"

"Get in," snapped Kleon. "There is no time for explanations."

Beltan vaulted, pulled himself inside. Sam sprang up—just in time. For already the warriors were streaming out again from the merging passages, the deadly stellene rods lifting in their hands. And far behind came an ominous, whispering whine. Vardu was in pursuit.

Far behind came an ominous, whispering whine. Vardu was in pursuit.

Sam's Colt barked again and again, and each time a raised tube clattered to the ground, a giant figure crumpled behind it. Behan's blaster cut wide swaths of blue destruction as he pumped electro-bolts into the swarming hordes. Kleon, a grinning god, once more in his element, whooped his Macedonian war song, hacked with cheerful strokes at the arms that tried to pull them down.

Then he stabbed at the panelled control board. With a roar of jetting rockets, the vessel gathered power, hurled like a thunderbolt up the broad passageway. Once again. The warriors scrambled for safety, or were cut down like bowling pins.

SAM looked backward. A faint speck showed far in the distance.

"Vardu is following us," he said.

"He'll never catch us," the Greek retorted cheerfully. "This boat of mine is the fastest one in Harg. Alanie told me so; showed me how to work it."

The Olgarch glanced at him strangely. "We thought," he said, "you had succumbed to her charms, deserted us."

Kleon stared. "The friendship of man for man is more enduring than love for a woman," he answered sternly.

"Why then——"

"It was our chance for escape. I pretended infatuation, made Alanie show me the secret niche of Hanso's private rocket ship. She even was willing to join us. She hates Hanso."

"But Hanso was to kill you, and Vardu to kill Hanso," exclaimed Sam.

The Greek smiled carelessly, manipulated the hurtling vehicle like a veteran rocket pilot. "Alanie saw him come through the secret entrance," he said. "I swung at her warning cry. It was too late to reach for my javelin, or pluck out my sword. So I lunged instead, caught him at the waist. At the same time, Vardu stepped in, needle ray blasting. It smacked Hanso in the back of his skull. He sagged in my arms. I saw Vardu lifting the tube again. I flung the dead Hargian squarely at him. Vardu went down, stunned.

"I wanted to finish him, but the Hetera were shrieking like madwomen, and I could hear the thump of running men. I raced for the rocket ship, called on Alanie to follow me. But she just stood and smiled up at me. 'Go, my Kleon,' she whispered. 'I'll stay and delay pursuit. You'll be better off without me.' Before I could do anything, she had raced to the panel, pressed a disk. A wall rose to shut me off from the quarters, another opened into this passageway. The rest you know."

"Good kid," breathed Sam. "I didn't know she had it in her."

Ahead was daylight, and the slanting rays of the evening sun.

The car leaped through the opening into the valley of the ancient Andes like a meteor in reverse. Up, up it snouted, cleared the frowning ramparts, hurtled high into the reddening sunset.

"Where do we go now?" demanded Kleon.

"North!" said Sam, eyes taut with what he had seen in Harg. "To give warning! Hispan is safe from onslaught. The stellene disintegration will not affect its neutron ramparts. But farther north, in what was once my nation, there may be cities, peoples, insufficiently guarded against the fascist hordes of Harg. Perhaps," he added a bit wistfully, "I may even find a people, a culture, more like what we of the twentieth century had dreamed of for this year of 9737."

The Olgarch looked at him with a sidelong glance, but made no comment. Instead, he remarked with a little chuckle, "I am inclined to think that our friend Kleon rather regrets Alanie."

The young Greek shook his head with quiet dignity. There was pain in his voice, longing in his eyes. "She was very beautiful!" he whispered half to himself.

But Sam's eyes were only ahead, straining over the tumbling mountains, searching the shoreless Pacific, seeking in vain some sign in all that tangled wilderness of human habitation, of human striving.

They sped on, ever steadily north. Once more three men, heirs of diverse times, united in past adventures and the grim prospects of future perils!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.