RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

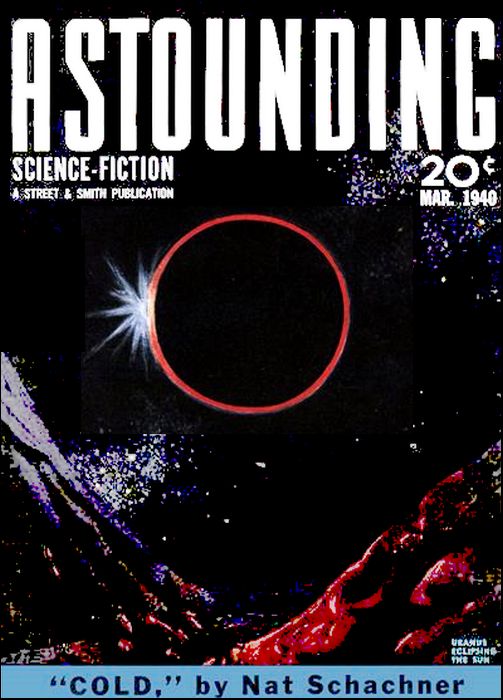

Astounding Science Fiction, March 1940, with "Cold"

Cold—and lack of power—threatened two worlds, and five

men who must be the arbiters, whether they willed it or not—

THERE were five of us on Ariel when the trouble Started, not counting the Venusian troglos, who don't count anyway. They're squat and bowlegged, with gnarled, powerful limbs and faces the general color and texture of old roots, and they do all the dirty work of the System. They are especially good at mining and digging and they can handle a machine when it requires only a single, repetitious operation. But of brains or initiative they haven't a vestige. Fill up their bellies with pullca meal and give them a mouthful of the narcotic bassa leaf to chew on while they're working, and they're perfectly happy and submissive, no matter where they are.

Of the five who counted—so to speak—three were Earthmen and two were Martians. It had been a delicate problem, in a way, picking us five for the job. The allied governments of Earth and Mars had sweated blood before the personnel had been finally chosen. Diplomacy had to get in some pretty dirty licks, there were governmental conferences on Earth, then on Mars, then a big powwow on neutral Venus, and finally the five names were agreed upon.

Don't get me wrong, though. The wrangling didn't take place over Jimmy Vare, yours truly, of Earth. The Mining Explorations Council of Earth picked me because I had been lucky enough to be the first guy to uncover the armorium deposits on Ariel. Nor was there any dispute about big Bill Snead, who knows how to handle a crew of troglos like nobody's business. The two Martians were also the private concern of their own government. Sar-xltumph—or noises to that effect—was the ultimate authority on heavy elements, and they don't come any heavier than armorium. Ango, with a similar hyphenated string of unpronounceable syllables, made the fourth. He was a crackajack at fashioning new machinery and new methods to meet the almost insuperable obstacles of interplanetary mining.

So far, so good! No trouble at all in making the selections. But it was the fifth who caused all the diplomatic squabblings. Who should he be—an Earthman or a Martian? And if so, why?

For look at the set-up! Ten years ago, when I was a wild, scatterbrained youngster with a yen for shoving a spaceship where no one else had been fool enough to go before, I had come to Ariel. And, with the luck that is somehow the birthright of all fools, I had found an outcropping of armorium, chipped off a few samples and brought them back with me to Earth for analysis.

Now, no one had ever seen armorium before in the flesh. It was a new element—they placed it as No. 99 in the atomic scale eventually—and it sure was heavy. But that wasn't all. The bigwig scientists of both planets got busy on the stuff, and discovered some remarkable properties. Its electrons were packed so tight that nothing could budge even the thinnest beaten plate—no acids, no alkalies, not the most powerful explosive or bombardment ray known to the System. Nothing, that is, except a certain limited range of very soft X rays. The first guy who turned on the juice, just out of scientific curiosity, went up with a bang. So did his lab and most of the town in which it was located. Luckily he had tried out his X rays on a bit of armorium about the size of a pea. If he had turned that particular wave length on an honest-to-goodness hunk he might have blown all Earth to smithereens.

For more cautious experimenters discovered an astounding fact. Armorium, impervious to every mighty agent known to the planets, collapsed into pure energy when a soft ray, of the order of 10-8 cm. wave length, was focused on it. Here was atomic energy with a vengeance. Sure, there had been atomic energy before, but its release required tremendous machinery, millions of volts of power, and an energy output that barely topped the intake. Here, with a tiny X-ray generator worth only a few bucks and a modest electric current, energy was to be had for the asking. And it could be controlled, as investigators found out after a few more tragedies. A shift of a few millimicrons either way in the wave lengths of the X rays, and the speed of disintegration could be hastened or retarded as desired.

No wonder both Earth and Mars went haywire! With unlimited power on tap, with a heavy metal besides that otherwise could withstand the full impact of a planetary collision, all civilization had to be revamped. Within a few years armorium was an integral part of industry and science, of cultural patterns and human life. Take away armorium, and the two worlds would be in the position that Earth, let us say, back in the ninetieth and earlier part of the twentieth century, would have been without coal and iron. Sunk! Through! Washed-up!

NOW maybe you can understand why the composition of the five-man Board of Supervisors who handled all operations on Ariel was so all-fired important. Why didn't Earth claim sole title, inasmuch as I, an Earthman, had discovered the stuff? Because a neat little clause in the Earth-Mars treaty of relations took care of that. A couple of centuries ago, when the first expeditions landed on Jupiter's moons, there had been plenty of trouble. Claims and counterclaims. Dogfights, and finally a bang-up war. When the smoke of disintegration dusted off the interplanetary ways, the sane men of both worlds got together. Thereafter, all new discoveries, colonies, planets, et cetera, were to be joint property and jointly administered by five-man boards, two and two and the fifth by agreement.

It worked out swell. The Jupiter moons, the Saturnian satellites. No trouble at all. Then I had to go and light out for Uranus. Still no trouble, except for diplomatic finagling. For they finally agreed on the fifth man. Even the Martians, who naturally wanted a majority, agreed they couldn't have picked a better chap.

Enos Abbey is old in years and in honors, but his spirit shines like a halo around his white hair and wrinkled face. He's respected and loved as much on Mars as on Earth. He's a scientist of the first rank, an administrator second to none, and everyone is his brother—even the troglos. By this you'll suspect that I like Abbey—and you could double and redouble that. But then, I'm not alone in my enthusiasms.

WE got along swell on Ariel during the years. Don't get any wrong ideas, though, that Ariel is the last word in summer resorts. It isn't. Imagine a huge hunk of slag just out of the smelters, jagged, splintered, brittle with razor-sharp edges where molten bubbles of metal have cooled and exploded, and you'll have a fair, if incomplete, picture.

No air, no water, no vegetation, no heat. Especially no heat. I thought I had known what cold was before I came to Ariel, but my ideas underwent a prompt and unpleasant revision. As the innermost satellite of Uranus, it's muchly distant from the Sun. In fact, the Sun is just another star out there—a mere point of light. Of course, it's far more brilliant—the light is about that of three thousand full moons as seen from Earth—so there's plenty of light.

But the temperature! An even two hundred and sixty-five below zero, Fahrenheit; except when Uranus eclipses the Sun, as it does regularly, when it drops another fifty degrees or so. It gets you finally, that cold. Even the spacesuits, heated with interior electric units, can't keep it out when you slog over the God-forsaken landscape long enough. We usually stayed put in our diggings in Sterile Valley, where we kept our labs, our living quarters and general storehouses. The mines themselves were about a mile distant, on the spur of what we called the Everlasting Mountains. That name was my poor idea of irony, for the troglos, in space-armor, were digging them away at a tremendous clip. The armorium deposits outcropped on the spur, but every test we made showed that they angled deep down into the bowels of the little planet.

So everybody was happy. Earth, Mars, with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of the precious metal on tap, the troglos, their wide mouths and ample bellies taken care of—and us five supervisors.

We got along swell. Big Bill Snead, a blond giant with a slow, good-natured smile and an easygoing disposition, got along with everybody. Sar and Ango—we never tried to pronounce the second parts of their respective handles—were high-type Martians, and that means plenty. For the Martian nobles, as bred through a million Martian years, had refined into pure armorium. Tall, slender, with a slightly greenish cast to their narrow, elongated heads, with large, expressive eyes of a startling yellow, they were aristocrats in every graceful move, in every convolution of their intricate thought. Enos Abbey, as I have said, could go out on the Martian desert and bring back the terrible steel-fanged xlars fawning at his feet. As for myself, I manage pretty well as long as no one tries to take a poke at my homely phiz.

We took turns on shifts. There were the mines to be watched, blasting operations to supervise, cargo boats to be loaded and supplies unshipped, televisor communication with the home planets to be kept in working order. But every thirty-six Earth horn's we all got together. The thin twilight of day changed to a Stygian black, imperfectly relieved by a million sharp, icy stars and a dim, vast, mottled Uranus.

Then, while the troglos snored in their shelters at the mines, we let off accumulated steam in the underground chambers at Sterile Valley. It was warm there, we had a good library, canned music, certain creature comforts painfully accumulated over the years—and we talked. We talked, in fact, interminably: sometimes forgetting most necessary shuteye.

You might think that was strange—five shut-in men finding things to say to each other after years of enforced, lonely comradeship, broken only by semiannual cargo ships. But we did. And never a quarrel, never even high words. We pretty much thought alike, but each had some facet he could illuminate for the others out of the recesses of well-stocked, nimble minds.

We talked about the daily routine, naturally; scientific problems and engineering difficulties involved. The eternal cold was also a topic, though we played it down by mutual consent after the second year. The troglos were always good for some anecdote—none of us quite considered them as human; except Abbey, of course. But we talked most of the things that mankind has pondered over and never solved for thousands of years on Earth, and millions of years on Mars. The meaning of life, philosophy, the extent of the Universe, first causes, final dissolutions, space and time, history, the whys and wherefores, and the mysteries of comradeship.

Sar was especially eloquent on the last topic. He was a shade more vital, more vibrant than his fellow-Martian, Ango. Ango said less, but when he spoke there was meat in his words.

We had drifted in one by one to the big central dugout, each making sure as a matter of instinctive routine that the air locks were closed tight behind us; and shrugging out of our unwieldy spacesuits with a sigh of tired anticipation. The thirty-six-hour cycle was just ending, the troglos were snoring in the mines, dreaming of more bassa leaves and their mouths drooling in the process, and the deep excavations had settled into frozen quietude.

I stretched my long limbs luxuriously in the cozy warmth of the diggings, thawing out after a more than usually tedious job of prospecting in the icy canyons the other side of the Everlasting Range. It was the shift that no one liked—the cold burned into your bones, the savage landscape dipped in eternal twilight, the silence and the loneliness got you. Of course, we never uncovered any more deposits of the precious armorium, though iron and nickel were pretty plentiful—and some gold.

Yet the home governments had insisted. Though we were pretty certain that the lode we were working went deep and solid, the politicians back home were jittery. Suppose the stuff suddenly gave out. The civilization so carefully built on the foundation of armorium would collapse over night. There was no substitute.

ANYWAY, I wasn't worrying about that at the moment. I had dutifully done my trick, and ten hours of time to call my own stretched ahead. I should have gone to sleep; so should the others. But you have no idea what the camaraderie of good, strong, loyal men means to one who has been cooped up on a savagely untamed, desert ball on the outskirts of the Universe for almost a decade. We craved each other's society like strong drink; we swore fealty to each other over and over—Earthmen and Martians alike—and we cupped our friendship with careful hands, fearful even to waste a drop.

Sar was holding forth as I allowed the grateful warmth to seep into my tired bones. Big Bill Snead sprawled in a chair, grinning lazily, reacting to the flow of words as a cat does when its fur is properly scratched. Ango, his slender, elongated head cocked to one side, seemed to be reserving judgment.

Sar said: "Look you, man is a reasoning being. It took him a long time to reach that point, but we've reached it. In the old days—I admit it for Mars as well as for Earth—the emotions ruled. Brute emotions, like hate, envy, greed, jealousy, lust for power. Of course they cloaked it with fine words, with rationalizations, but that did not matter."

"And today, those emotions have vanished?" Ango wanted to know.

"Of course they have. The last war anywhere on the planets took place more than two centuries ago. The worlds are organized on a rational, sensible basis. Earth and Mars are ruled separately, but they co-operate amicably, without argument. Our very presence on Ariel is a symbol of that unity. I'm a Martian by birth, so is Ango; Bill Snead and Jimmy Vare are Earthmen, not to speak of Enos Abbey; but does that mean a thing to us? Do I think of any planetary distinction when we're together? Do any of you others?"

"Hear! Hear!" Snead murmured approvingly.

I rubbed my hands together with a sigh of content, and sank into a chair. "Where's Abbey, by the way?" I asked.

"Over at the mines," Snead told me. He lit up a pipe and puffed.

"Shouldn't he be back by now? It only takes fifteen minutes on the trail, and it's half an hour past closing time."

"You know Abbey. He mothers those troglos like a brood hen. I'll bet he's bedding them down, and tucking them in so's they won't catch cold. But Sar's right, Jimmy. That thing called patriotism is a thing of the past. We're all just men together, regardless of where we've been born or raised."

"I suppose so," I answered vaguely. My mind was on Abbey. He was an old man, and the trail from the mines was treacherous. Suppose he had slipped. Suppose—

"You suppose so!" echoed Sar indignantly. "Why, you blithering idiot, look at me. Could you even dream of hating me, of blasting me down with a needle ray just because I'm a Martian and you're an Earthman?"

I jarred out of my abstraction. "You old son," I told him affectionately. "I'd cut off my own right arm first. You're more to me than a blood brother. Sure, patriotism is the bunk, an outmoded irrationality."

"There you are, Ango," Sar said with a gratified air. "What did I tell you about those primitive emotions?"

But Ango only grunted. For just then the thin whoosh of the outer air lock could be heard. I sprang forward eagerly. I had been silly to worry about old Abbey.

He came in now, closing the lock softly behind him. He stood there a moment, motionless in his space-armor, his face blurred behind the steamy mist that had already condensed on the outer surface of the glassite helmet.

I started to help him out of the clumsy equipment. One did little services for Abbey without a second thought. "I was getting worried about you," I said, as his soft white hair emerged in a cloud. "Thought you'd fallen somewhere and hurt yourself." I zipped him out of the baggy suit and he walked slowly forward to the visor set. His face had a curiously set look upon it, and he did not answer me. In fact, he hadn't said a word since he entered.

THE CONVERSATION died, the words of greeting stumbled and fell by the wayside. Sar stopped in mid-oratorical stride and looked funny. Ango cocked his head a little farther to the side. Snead sat up straight in his chair and stared.

This wasn't like Abbey at all. He usually came in, quick and birdlike for all his years, a warm, individual greeting for everyone who had preceded him, a beautiful smile irradiating the whole diggings with his personality.

"Hey, what's the matter?" Snead yelled. "One of your troglos get the pip?"

"Shut up, Bill," I grunted. "You know what Enos thinks of them."

But the old man did not seem to have heard. His long, wrinkled fingers, still deft and quick as those of a surgeon, rested on the visor keys. His face had not relaxed in the slightest; his baby-blue eyes seemed to pierce the rounded walls of the subterranean quarters and fix on something far out in the Universe.

I took a quick step forward, laid my hand gently on his arms. "What is it, Enos?" I asked. "What has happened?"

He stiffened under my touch; then he turned slowly and faced us. You could have heard a feather drop. Everyone was silent; suddenly serious.

He took a deep breath. There were no preliminaries, no leading up to the news.

"It's the armorium lode," he said. "The troglos have come to the end of it in the No. 3 shaft."

Just that! Nothing more! But if Ariel had suddenly exploded under our feet and catapulted us all into space, we couldn't have been more aghast. No blueprints had to be drawn for any of us. We had lived with the mine for almost ten years; had lived, slept, breathed, with the thought of it in our minds. We knew every inch of it, every blessed outcropping. And we knew what that meant.

Ango was the first to recover himself. He always was. "Are you certain?" he asked, sort of dull and low.

"That's why I'm late," said Abbey. "I didn't believe it myself. When the troglos came chattering up to the office, I went down personally. I found that the drills were embedded in gneiss and lava. The armorium lode ended abruptly, as though it had been cut off. Still I didn't believe. I got the troglos back to work. The drills bit deeper. Perhaps another formation had been forced through the main lode by an ancient eruption. We went down one hundred feet, working like mad." He stared at us with those soft blue eyes of his. "We hit nothing but lava and gneiss, the bedrock of the planet."

"But our instruments showed that the No. 3 lode went down for miles and miles," I protested.

"The instruments were wrong; or, rather, we interpreted what they told us wrongly. What happened was this: The gneiss and lava are mixed in the exact proportions that will give an electrical reaction similar to that of the armorium ore. It was one chance in a million."

Snead came heavily to his feet. "Then... then," he stammered, "that leaves only the No. 1 and No. 2 shafts. About ten thousand tons more of armorium to be dug out. We know exactly where they end." Abbey nodded. We had worked out the figures about a month before, but they hadn't worried us any. That damned No. 3 vein was supposed to be practically inexhaustible.

"At the present rate of consumption in the System," I reflected aloud, "that means about a three-year supply—"

Sar shrugged his slender shoulders. He even essayed a smile. "In three years," he remarked optimistically, "we'll find other veins."

But, even as he said it, the smile died. He knew, as well as we, that there weren't any other veins. Nowhere in the entire System. Don't think that the mining councils had sat back on their haunches while we worked Ariel. On every planet, on every satellite, on every measly little asteroid, the search had gone forward since that first discovery of mine ten years before. And everywhere they had drawn a blank.

No, sir, this particular vein was unique in the Universe; a sport, a freak in the cooling processes of a barren little world; a quadrillion-to-one shot.

Abbey turned to me. "Any luck today?"

I spread my hands with an eloquent gesture. Not any luck today, not yesterday, not tomorrow, not ever. I was sufficient of a geologist to read the signs. We'd been practically all over the little twilight planet. There was only one tapping of armorium and that was now soon to go dry!

There was silence again. Every man was busy with his own thoughts.

And the more he thought the less he liked it. Three years' supply of the essential element at the most. Three years for an interplanetary civilization to reorient itself, to shift from a culture based on armorium to one based on primitive molecular power. A turning back of the clock.

"They'll never be able to do it," Ango said quietly. "The worlds are geared to quick, easy energy. Everything depends on it."

"They'll have to," I retorted.

"Of course," nodded Sar, regaining his resiliency. "The best brains of both planets will get to work on the common problem. In three years' time they'll find a new source of energy."

I was skeptical, but I kept quiet. After all, miracles have happened before.

Abbey opened the visor unit, sent out the first long dash that was our code signal to Earth.

"Going to tell the folks back home?" asked Ango.

"Naturally. They'll have to get started on their plans at once."

NOW it takes some three hours for a signal to travel from Ariel to Earth—or Mars, for that matter—and three more hours for a response. So you can readily see that communication is lengthy, tedious and fraught with considerable difficulties. Therefore I will sort of telescope the conversations that took place, though in fact they extended over a period of several Earth days; and we went about our regular routine during the interval, leaving Enos Abbey in complete charge of the visor.

John Horner, congressional leader of Earth, is a man of few words. All he said was: "I'll convene Congress at once, and call you back." Then, as a sort of afterthought: "Don't notify Mars until you hear from me. This is an order."

But by the time the "order" winged its weary way through space, Abbey had already put through the call for Mars.

We were still around when that cryptic command came through. I could see old Abbey stiffen; Sar and Ango looked surprised.

"Now, what did Horner mean by that?" demanded Sar.

Abbey's baby-blue eyes were gentle. "Maybe he wants to break the shock of the news himself."

Ango leaned forward. "What will you say to Titl when his signal comes?" he asked very quietly. Titl was council head of Mars.

It was Abbey's turn to look surprised. "Say?" he echoed. "Why, just what I said to Horner. Tell him the truth."

I could feel the relaxing of a certain tension then in both Sar and Ango. It was a curious sort of feeling, something I hadn't noticed around Ariel since we holed up together. I was angry. Angry with Horner for that stupid order, angry with myself for being angry. I was all mixed up.

We threshed the thing out, and finally agreed Horner had meant nothing by it.

Then the Martian response came through. Titl was even more cryptic than Horner. "Council will go into immediate session to consider what's to be done. Leave Earth to us."

"Now, what did he mean by that?" countered Bill Snead, his lazy, smiling eyes developing a certain glint.

"The same thing that Horner did," I shoved in hastily. "He thought he was the first one to be notified, and he could relay the news to Horner much faster than we could."

"Yeah, I suppose so," he admitted reluctantly.

But I wasn't satisfied. I didn't like it, but I kept my dislike to myself. Perhaps I was just jumpy, imagining things. It was infuriating—this business of six-or-more-hour intervals between answers. It gave one the impression of a slowed-up visor screen where the machinery went haywire and the guy at the bat is starting a swing at the ball and never getting there.

We kept on working right along. Life had to go on, and the precious armorium became now infinitely more precious. We each dropped into fixed grooves, instead of shifting around as before. Each man took the job he was best at, and stuck to it. I myself suggested that I put in full time at further explorations. It was rotten work, tramping over jagged lava flows that cut even our steel-shod shoes to ribbons in short order, toiling over precipitous crags and descending into eerie gorges, always in dim twilight and sometimes in a blackness one could never conceive of back on Earth. Uranus was a brooding, monstrous disk overhead, tinged with apple-green—a world as fantastic as its tiny satellite, a mystery-shrouded planet whose core could never be pierced. Thousands of miles of gaseous, liquid and solid methane, ammonia and carbon dioxide overlaid that core.

Yet I stuck to it feverishly. The stakes were infinitely greater now. I fine-combed the tumbled landscape, bending over ungainly in my space-suit, flashing my hand-beam over the sullen rocks, checking with the sensitive reaction-instrument that hung from my neck like a locket, seeking always some sign that armorium might be buried beneath. Backbreaking, ungrateful labor, with the outer cold always boring through my heating units; yet I didn't mind. It sort of kept me busy and my thoughts from brooding.

Three years' supply! Two worlds in desperate need! It would have been far better if I had never discovered the damned stuff! Thoughts that were like squirrels chasing their tails interminably within the narrow confines of a cage.

On the fifth day we met in the central chamber. It was the first time all of us were present at the same time. But each man had secretly figured out for himself that communications from the home planet were about due. We had heard nothing further since the response to Abbey's first report and the silence was maddening. So we drifted in, each pretending he was dog-tired and needed a rest.

I wasn't pretending, either. I could barely zip myself out of my suit. I had put in ten solid hours in the region of the Hell Hole—the name we put to it speaks for itself—and I could hardly stand. Sar was at my side immediately, offering assistance and a cup of hot coffee. I gulped down the steamy liquid and almost scalded my stomach, but I felt better then.

"Thanks, old boy. Any news?" I added casually.

He shook his head. "Not a thing. The home planets must be putting their heads together."

"They'd better," I said wearily. "I've searched and searched, and it's no go."

Old Enos surveyed us all. There was affection in that glance, clean understanding. Then his eyes deepened.

"Promise me," he said abruptly, "that no matter what happens, you'll all remain just what you are now—comrades, friends through thick and thin."

Big Bill was sprawled in his chair. "Why... hell... sure. There's nothing could tear us apart. We've been through too much together, the good with the bad. We know each other inside out. But what's the idea, Abbey?"

The old man went inscrutable on us. "Nothing in particular, Bill. But how about you others?"

We all spoke at once—a confused chorus that made a queer din of agreement. It sounded funny, in a way, grown men like us making pledges of eternal friendship, but it warmed my heart and made me feel aglow all over. Good men and true, the kind you could rely on forever and ever. Nothing could break up this gang. From what I saw written on the others' faces, I knew they felt the same as I did. A love fest.

Old Abbey smiled as though in relief. His smile was beautiful to see. It was like a benediction gathering us all in.

THEN the visor set sounded off. The signal isn't particularly noisy—we only turn it on full blast when the last man quits the diggings—but we jumped as if a Jenkins bomb had smacked us.

Abbey was standing near the unit, so he thrust it open. The screen glowed. A picture formed on it. The Congress of Earth, with John Horner seated in the leader's chair. It was impressive-looking. The great world chamber situated on an artificial island in the Caribbean, with its white tiers of seats extending interminably up to accommodate the tourist hordes that usually attended the sessions of Congress. But this time the vast hall was almost empty. The visitors' seats were clean and bare. Congress was in secret session—the utter seriousness of the moment was unmistakably imprinted on each and every face of the three hundred delegates. John Horner faced us unseeingly. You can't have two-way vision when the electromagnetic waves that carry the vision take three hours each way to hurtle the gulf between you.

Horner was a heavy-set, florid man with bushy eyebrows and a face that masked his thoughts. Yet just now he was obviously excited. His fingers drummed on the tinted stellite desk at which he sat, and his eyebrows moved in individual spasms.

"Casing Enos Abbey, William Snead and James Vare on Ariel." His voice was steady enough. He repeated our names. "This message is private and confidential. Please see to it that no one else is present. I am waiting five minutes. By that time you are to be alone." He repeated that three times carefully, then he stopped and waited. The congressmen sat rigid in their seats, making no sound, waiting.

We looked at each other and stirred uneasily. No one seemed to want to speak; but curious green flushes tinged the cheeks of both Sar and Ango.

Then Ango rose. "Come, Sar," he said steadily, "it is time for us to go."

We all spoke at once then—the three Earthmen. I remember shouting inanely that they were to stay if I had to knock them down in the process.

Bill Snead snarled: "Sit down, you chumps!"

But old Abbey's voice muted our sudden clamor. "It is a pity," he observed, "that we can't explain our position to Horner and Congress right now. He evidently misunderstands our status on Ariel. We have no secrets from each other. Whatever Earth wishes to tell us, must be told to all."

"Attaboy!" exclaimed Bill.

I made approving noises.

Sar and Ango stared at us, then at each other. The flush died in their cheeks. "Thank you!" said Ango softly, and sat down. So did Sar.

We all breathed easier, then turned to the motionless visor. I never knew five minutes could last so long. Talk about the relativity of time! I could have lived a couple of busy lifetimes in that interval while the beam-chronometer flashed off the seconds. No one said a word, we just sat there and waited.

Then Horner started to talk. He seemed to be staring straight at us—though we knew he couldn't see us, yet. "I assume," he said, "that only you three men of Earth are present. You will understand why this is vital as I go along. Your news, I need not tell you, was of the utmost importance. The System has relied upon your assurances that there would be a sufficient supply of the element, armorium, to last for many hundreds of years. The planets have acted accordingly; in particular, our own Earth."

He cleared his throat, and we fidgeted in a dead silence. We didn't want to miss a word.

"Now we find you have been mistaken. Now we are told there is only sufficient to carry the System through about three years. But Earth cannot shift back to primitive power methods in that short time. It would be disastrous; there would be starvation, suffering of the worst kind." He looked carefully at his fingernails. "There might even be a world revolution. People might think that Congress and myself had mishandled the situation."

A low susurrus of agreement made a wind through the delegates, and died.

"I never did like Horner," grunted Bill. "Thinking of his own hide, instead of making plans."

One would think that Horner had heard him. For he was saying: 'Therefore, after lengthy secret sessions, we have come to certain conclusions. In the first place, it is obvious from your report that the flame for your miscalculation of the armorium deposits must lie directly with the two Martians on your board."

"What!" Sar bounded from his chair, his face jerking with anger. "He dares—"

Ango pulled him down. "Take it easy, my friend. Let us hear what further he has to say."

As for the rest of us, we sat there stunned, while Horner's voice rolled on.

"They misled you three Earthmen as well as ourselves," he continued smoothly. "No doubt they kept their home planet well advised, while we were completely in the dark. As a result, we have authentic information that Mars has secretly laid in a stock of armorium to last them for many years. They plan to force us back to primitive conditions, and then sweep down upon us with their hordes and eliminate us as a rival power."

"That's a lie!" screamed Sar, his mouth working.

"Of course it is, son," soothed Abbey. His eyes held pain, as though he had known in advance just what would happen.

The visor droned on. "Therefore," said Horner, "to safeguard our homeland, to protect ourselves against the machinations of these vile barbarians of Mars, Congress has decided on decisive steps. Even as I speak to you, a well-armed, well-equipped battle fleet is taking off from the rocket port of New York. It has secret orders to proceed full speed ahead for Ariel. In the meantime we command you as loyal, patriotic sons of Earth to co-operate with us. The future of our world depends on your efforts.

"You are to seize the two traitor Martians on Ariel, imprison them securely so that they may not warn Mars in time. Another thing. If, as we have information, the Martians are racing a fleet to seize the planet, you are to hold them off until we arrive to destroy the enemy. You have certain weapons of defense that were installed as a protection against possible pirates. Use them."

Horner's face became grim, tense. "Remember, Earth expects every loyal son to do his duty. That is all." The screen died. I heard myself saying dully: "My God! Have they gone crazy? This means war."

ANGO came slowly to his feet. His greenish face was almost white. His slender nostrils were expanded. He stared at us pleadingly. "You heard what your leader said. Do you believe that about us?"

Big Bill Snead's ordinarily good-natured face was a stormy thundercloud. "Hell, we know different. Horner's trying to propagandize us into something smelly. He's nuts if he thinks he can do it."

Sar was quivering like a racehorse after a swift, climactic finish. "But your Earth is sending a battle fleet," he cried. "They'll seize the mines, and then smash our Mars. It's... it's—"

"Don't say any more, son," Enos-Abbey broke in softly. "You will regret it later. This is no time for calling names. We must put our heads together and decide what to do." His arm brought the two Martians, who had drawn a little apart, into our midst. "All of us!"

Ango shot him a grateful glance. His mouth opened to say something, when the signal burred again. "Ah!" he breathed. "They have changed their minds. They will countermand their instructions."

Abbey turned on the screen. "Here's where everything goes to pot," I muttered.

It was not Horner. It was Titl, head of the Council of Mars. He was alone in his private office high above the Great Central Desert. Fantastic murals, depicting the strang flora and fauna of the Red Planet intertwined in mortal combat, flamed on the walls. Personally I could never see how any sane being could work in the midst of such nightmares, but the Martians didn't mind.

He stared out through the depths of his own screen unseeing at us. He seemed to be attempting to probe the secrets of our dugout, over a billion miles away on Ariel. He was taller even than Sar and Ango, and his general color was a deeper green. His eyes had a certain cold, piercing quality, and his lips were tight-compressed.

"Calling Sar-xltumph and Angoqdwirk." How any mortal tongue could rattle off those tongue-twisters of names I never could understand. "This is private, for them alone. If you are present, please ask the others to leave. If only an Earthman is present, be good enough to call them at once and then permit us to be left alone. I shall wait ten minutes."

"Holy cats!" Snead ejaculated. He bowed ironically to the screen, then to Sar and Ango. "He's pulling the same gag as Horner. Shall we go and leave you to your tête-à-tête?"

"Don't be a fool!" Sar growled. "He has nothing to say to us that you can't hear. You are to stay." Old Abbey sighed. "I expected you to say that."

Then we relapsed into silence again, sneaking each other sidelong glances. But our faces were eloquent of the turbulent thoughts within. This business was getting on our nerves. First Horner, now Titl. I braced myself for the shock when the ten minutes were up.

Sure enough, it came. I won't repeat everything Titl said to what he thought were the private ears of Sar and Ango. It was close enough to Horner's spiel to be its first cousin.

The burden of it was that us three Earthmen had pulled the wool over the eyes of the poor, trusting Martians; that Earth knew what was what all along and had finagled vast stores of armorium into their possession; that not content with such outrageous stuff, they were now sending a fleet to grab whatever was left, and then proceed to wipe Mars out of the System. But Mars was wise, and was jumping the gun. Even now a great Martian battle line of swift cruisers had taken off to get to Ariel first. It was the duty of Sar and Ango as faithful, patriotic Martians to jump us blankety-blank Earth scum unawares, so we couldn't pull any more dirty tricks. Then they were to put the defenses in order and hold off the enemy fleet until the brave Martian boys came galloping through space—blah—blah—blah!

Then he faded out in a burst of fervid hokum.

Sar and Ango just sat there gulping. Their vocal muscles seemed paralyzed.

I said: "Humph! This is where we came in before. Horner and Titl; Earth and Mars; six of one and half a dozen of the other."

"Did you boys believe all that twaddle?" Bill purred.

Sar shook himself. His large, yellow eyes blazed like an electric caldron. "Titl has gone crazy," he husked. "Patriotism! Love of home! Honor! Blah! He's just as bad as your Horner. They're both cloaking short-sighted, selfish grabs with high-sounding words."

Old Abbey positively beamed. "I'm glad you're all taking it this way. I was very much worried this past week, since we sent the news. I don't mind confessing now that I expected something like this."

"You did?" I yelled. "Then why didn't you let us in on it?"

He shook his head, and it looked like a soft snow going into action. "I was hoping against hope, I was hoping that the politicians back home would forget their little localisms and outmoded methods and do what we five have been doing. Work shoulder to shoulder to solve this problem which confronts them for the common good."

Bill Snead sprawled deeper into his chair. His hands were in his pockets. "How much time have we before the rival fleets come tearing over here to take us apart?"

They all looked at me. I had served, when not more than a kid, on an old battle-ax, hunting smugglers among the asteroids; and ever since I've been supposed to be an authority on space navies.

"Well," I said judicially, "that depends. The cargo boats take anywhere from three to four weeks when the planets are in conjunction with us, several months when we're in opposition. Unfortunately we're pretty well in a line now. But they're tubs. The battle cruisers and space destroyers use the new Hutchins drive, and they literally burn up the ether waves. I'd say about ten days for the Martian crowd and another day for the Earth bunch—that is, if they took off simultaneously."

"Which they did," nodded Ango.

"Ten days' breathing time," said old Abbey. He was thinking aloud. "Ten days in which to decide what to do."

"Do?" retorted Bill. "There's nothing to decide. We tell 'em both to go plumb to Pluto. Were in charge of Ariel, and by the great horn planet, we intend to remain in charge. What armorium's left is an interplanetary trust, to be mined and divided for the benefit of all. No one planet is going to hog the supply."

"Bill is absolutely right," Ango chimed in. "Here on Ariel we are neither Martians nor Earthmen; we are citizens of the System. And, fortunately, our defenses are excellent. They were made to withstand for months the shock of any attack from space."

WE WERE all on our feet then, shouting, pommeling each other like a bunch of kids. We were exalted out of ourselves, and we told the world about it. We were brothers, cosmopolitans, broad-minded guys. None of that provincial patriotism stuff for us. A Martian or an Earthman—what difference did that make? White skin or greenish? Ancestry or habitat? That was the kind of tosh that bred wars and devastating hatreds. That way lay the brute and the savage. We were too damned civilized to be taken in by a lot of propaganda hooey.

We exhausted ourselves finally to meet old Abbey's mild, but critical, eye. We sat down again, feeling a bit ashamed, but defiant just the same. That was the way we felt, and we had to blow off steam.

"I am proud of you all," said the old man. "You've reacted just the way I had hoped you would. But mere words and backslappings aren't enough."

"O.K.," I growled. "You take charge, and tell us what we're to do."

Everyone said: "Yes, that's right. Let good old Enos take over."

"All right," he said briskly. "If you wish it so. The first thing we have to do is to put our defenses in order." His smile was rueful. "We've not paid much attention to them these last few years. There was no need. But they were installed by the soundest engineers in the System, and I think they'll hold indefinitely. There's the impermo-screen of triple vibrations that will make a shell of force around the entire planet, and is impenetrable to any weapon so far evolved. We have our space howitzers and needle rays, too, but we're not going to use them. After all, we don't want to kill men like us; we're strictly on the defensive."

"That's the ticket," I exclaimed.

He smiled. "Then we'll notify our respective home governments of our joint decision, and try to persuade them to call off this outmoded, barbarous war and get together like sensible men. And thirdly—and I think we'll find this the most difficult job of all—we've got to keep going just as though nothing had happened. The mines have to be run, cargoes made ready against the day of peace, and the troglos kept busy and satisfied."

"Them!" I said with a certain contempt. "The whole Universe could bust up as long as they get their daily quota of bassa leaves and they can dream about their native hunting grounds."

"You misjudge them," Abbey retorted with considerable heat. "They are human beings just as much as we are, with the same divine spark as we think we have. Their present degraded condition is our own fault. The first explorers who landed on Venus traded the vile bassa for their mineral wealth; and the rotten traffic's been kept up deliberately ever since in order to assure Earth and Mars of an obedient, servile labor supply."

It was the first time I had seen Enos Abbey so excited; so I said nothing. But everyone knew that the troglos were just one step removed from the animals, and there were those who even questioned whether it was a step up or a step down.

WE GOT to work at once on a carefully mapped campaign. We overhauled our defensive equipment. It was in a pretty bad state. But several days of hard, intensive work put it into usable shape again. I'll never forget the thrill we got when we first tried it out. The underground caverns where the power was developed shook with shuddering vibrations, and high above the airless planet—about twenty miles, in fact—the screen gradually formed. It was a beautiful sight. Every color of the rainbow was in it, flashing and gyrating like gigantic northern lights back home. Yet it was so thin and transparent that the stars of space peered through with hardly a jot of their steady beams shorn. The giant Uranus seemed a vast, dim, oblate ball swathed in shimmering gauze.

"It hardly looks as though it could withstand a peashooter, much less a Jenkins bomb," observed Sar doubtfully.

"Don't worry," Abbey said with confidence. "The impermo-screen has been tested repeatedly. It's a uni-way affair. We can shoot out against invaders, but they can't penetrate it from the outside."

"But we won't try," observed Ango. "We're acting only in self-defense."

Then we talked turkey with the home politicians. No use contacting the fleets. They'd take orders only from their respective governments. And, anyway, our visor beams were not geared for their code wave lengths.

Just as we had expected, both Horner and Titl were at first incredulous, then furious. But we had hoped to break them down, and convince them of the error of their ways; especially after we told them about the impermo-screens.

Evidently we had misjudged them. Each was convinced of the probity of his course, and that the other was a scoundrel. They blistered us with rage, with contempt, with epithets. That is, Horner directed his fire at the three of us Earthmen, and Till worked on Sar and Ango. Then they switched to appeals and exhortations. They painted us pictures of conditions on our planets—of the men and women and children, the common, ordinary, everyday, decent people whose happiness and very lives were bound up in a continuance of the status quo. Once our armorium supplies are exhausted—and their voices really quivered with emotion, there was no fake about it—everything collapses. We go back to the brute. Your own people, those whom you loved, relatives whom you left behind, will suffer. Picture the dislocation when our subatomic energy fails, when we have to fall back upon outmoded sources that can't supply a tenth of what our world now requires for daily life. The strong will trample the weak; ruthless men will arise and seize power; millions will die.

I confess that I felt a bit squirmy when Horner painted us his picture. I remembered with a shock that I had a sister somewhere in the city of Iowa. She had been a tousled kid when I hit the spaceways, but the pictures she used to send me showed a gracious, lovely woman now. And she had two youngsters, one of whom was named after me.

I saw Bill Snead slowly clenching and unclenching his huge fists. It hit him, too. His folks back home were pretty old, and they depended a lot on the slice of pay that he sent them regularly.

It was just the same when Titl took the floor. Sar and Ango stared down at the floor. They also had relatives along the Martian canals. Titl pulled a fast one. He brought the whole bunch of them to the visorscreen, and they begged and implored their far-off sons not to let them down. I growled a bit under my breath. That wasn't sporting. After all, old Horner hadn't done anything like that. Of course, he had told us about what would happen. And it was true—every word of it. No one could deny the facts. But to pull cheap propaganda the way Titl did——

I caught myself short, bit my lip. Steady, old boy, I warned myself. It's not Sar's fault or Ango's. We're all friends out here, swell guys together.

ABBEY asked pertinent questions of Horner and of Titl. Of course, a lot of the effect was lost because it took over six hours to get answers. The result was we practically forgot what was asked when the answers came through.

"Suppose," demanded Abbey, "you get a monopoly of the remaining supply of armorium? Suppose you win the war and crush the other planet? At the best there would be a six-year store for you singly, instead of three. Won't the same terrible things happen at the end of that period? Whereas if you get together—"

We perked up eagerly at that; and nodded to each other wisely. Good old Abbey! He put his finger on it, all right. We even looked at each other again frankly, smiling.

But damned if Horner didn't have the pat. answer! He shook his head sorrowfully. "We thought of that ourselves," he told Abbey. "Before we took any steps, we put it up to the council of technicians. They reported to us that, given six years and working at top speed, we might possibly change over to the old atomic output system without a too disastrous dislocation of world economy. In three years, however, that would be impossible. Those extra years spell the difference between collapse and success."

Titl, of course, rather lamely said something to the same effect. But he was smart enough to forget to point out that since there were much fewer inhabitants on Mars than on Earth, the change over could be made much more swiftly.

I said as much to Sar and Ango. And they almost bit my head off!

Sar's face was distorted; he foamed. "You talk like a blithering idiot," he howled. "You forget that the natural resources of Mars, as the older, longer civilized planet, are much smaller than yours."

"So you think you fellows are more civilized than we are," I began with cold dignity.

"Sar didn't mean that." Ango put his oar in. "But it's true about the natural resources; and in any event, suppose our population is smaller? Don't you think they'll suffer just the same?"

"Meaning, I suppose," Bill said sarcastically, "that when one Martian suffers, it adds up to the sufferings of two Earthmen."

We were all on our feet by this time, glowering away like a bunch of Kilkenny cats. Then Enos Abbey poured oil on the waters.

"Quarreling won't help matters," he said quietly. "You're acting in exactly the same fashion that the poor, propaganda-infected people of the home planets are acting. The four of you are men of sense, of understanding. Have you forgotten so soon the vows we took, the camaraderie of ten years?"

He went on in that vein for some time, and we gradually cooled down. I thought to myself: "Good Lord! but you're an idiot, going off half-cocked at good old Sar and good old Ango."

We started to feel pretty much ashamed of ourselves after a while, and we shook hands sheepishly all around finally, and swore we'd never get hot under the collar again.

Abbey sort of smiled benediction, but I noticed a strained expression under the smile. As though he were afraid of us!

WORK went on—mining, exploration, and all that. Four days had passed since war had been declared; four days while the converging fleets raced along the spaceways toward us.

I kept thinking of that all the time while I stumbled, lonely and aimless, over the bleak terrain. It was merely by instinct, by the routine habits of long usage, that I kept poking with my metal-sheathed rod at the crusted lava and took endless readings on the reaction-meter. I was positive there wasn't another deposit of armorium anywhere in the Universe. So I had plenty of time to think.

Suppose we did hold off the fleets. There'd be a dogfight out there in space just the same as soon as the two caught up with each other. I pictured that fight. Great Jenkins bombs ripping out the guts of beautiful cruisers, spilling their human contents like bloated insects into the empty frigidity of space. I had seen a man once fall through an air lock whose slide had become unfastened, and the thought of what he looked like still made me sick. Earthmen—the pick of the planet, husky, smiling, comrades of other days—going to destruction under the vicious fire of Martians.

And back home! I closed my eyes and almost went catapulting down into a gorge that went practically into the bowels of the planet. I saw our big cities, teeming with millions, laid waste under the swooping assault of the enemy. Little children, innocents, of our own race! Their reproachful eyes began to haunt me; I saw them everywhere; in the twilight-purple mountains, in the cold mockery of the stars, in the slow wheeling of Uranus.

I swore savagely at myself within my helmet. I took myself in hand. "You'll go nuts," I lectured myself, "if you keep this up. We're doing the right thing. Sar and Ango—"

I stopped short. Yes, Sar and Ango. Suppose they decided they were Martians first. Suppose, under their friendly, open countenances, they were plotting. It would be easy enough, when their fleet came hurtling along, for them to open the screen.

In spite of my heating units, the cold made tissue paper of my armor. I trembled all over. A blinding light struck me. By the long tail of the comet! I saw it all now. Those two babies had already fixed things, were even now laughing at us up their sleeves. No wonder they had agreed so quickly when I suggested I'd take the exploration shift, and that big Bill Snead would go to the mines!

It fitted in so beautifully. Ango was in charge of the all-important impermo-screen, and Sar had to do with the storage of the mined armorium. The two vital spots where they could betray us! Sure, Enos Abbey was permanently in our quarters, sort of supervising. But he was an old man, they could jump him without any trouble.

I wheeled around instinctively. The shadows of the Everlasting Mountains were ominously black around me. I thought I saw something move among them. My heart began to pound. Suppose one of those damned Martians was even now trying to sneak up on me. The airless waste would bring no sound.

With a curse I thrust up my metal-tipped rod. We carried no weapons—there had been no need of them on Ariel. There was no question about it now, someone was hurrying over the narrow trail from the mines, coming lickety-split, a wavering wraith in the gloom.

"Stop where you are!" I cried, holding the rod threateningly, and sprayed my beam. There were tiny communication units in our helmets.

The figure had poised with ungainly arms outspread as if to hurl itself on me. Then the light splashed all over it, and a voice, filled with relief, buzzed in my ears.

"Jupiter, but you gave me a scare, Jimmy."

I lowered my rod with an equal grunt of relief. "Not saying what you did to me, Bill. For the moment I thought you were one of the Martians."

"Yeah?" Through the glassite helmet I noticed how deadly serious Bill's ordinarily good-natured face was. "So you've got the idea, too?"

"What do you mean?"

"Well, up there at the mine, I got to sorta thinking. About the war and good old Earth, I mean. Then I began to notice the funny looks Sar would slide at me when he thought I wasn't watching, every time he'd drop into the mine. He'd talk to the troglos, and break off suddenly when I'd come within earshot. I looked him straight in the eye, just to show him he wasn't pulling the wool over me. About half an hour ago, he makes some lame excuse and hotfoots it for our quarters."

"He did?" I exclaimed.

"Yeah! And the more I thought of it, the less I liked it. What if those two birds've been playing us for suckers, with all that hooey about us being citizens of the System? What if they've decided to betray us to the Martians? After all, they're Martians."

"They are Martians," I said slowly.

He caught my padded arm with his flexible mitt. Urgency peered out at me. "They're back there—the two of them—alone with Abbey. The old man couldn't do a thing against them. They could—"

I wasted no more words. "Come on, Bill," I ground out.

WE WENT hotfoot over the dim trail, our steel-shod shoes jarring the jagged terrain into little sparkles of fire. We burst into headquarters gasping and running little rivulets of sweat. We barely thought of closing the air lock behind us as we ripped through.

Old Enos Abbey seemed backed against the wall. Standing close to him, taut and grim, were the two Martians. They whirled as we came catapulting.

Enos cried out: "What's the matter? What are you two boys doing here?"

I gripped my rod firmly, pulling off my helmet with my free hand. "Have they started anything?" I cried.

Sar and Ango exchanged quick glances. They edged toward the bin where some assorted metal bars were stacked. Sar said bitterly to his partner: "You see, Ango. You wouldn't believe me. These Earthmen thought to catch us unawares. It's lucky I came."

"Well, I'll be blasted!" I puffed. The colossal assurance of him flabbergasted me. "You were the first to sneak away from your post. We only came to make sure you weren't pulling any fast ones."

Bill growled, and Ango snarled. We stood there, all set to mix it.

Old Enos stared sort of aghast.

"Stop it!" he thundered. I never saw those mild blue eyes of his shoot fire before, but they did now. "Are you all crazy? First Sar and Ango come with a fantastic story about how they're afraid you two are plotting to turn over Ariel to the Earth fleet. Then you two barge in, intimating the same nonsense about them. Are you all the same men who only a few short days ago vowed eternal confidence in each other? Is the cold of this planet freezing common sense and common friendship, too?"

I did not relax my hold on the rod. "We played square!" I snapped. "But they're Martians, and I would not put it beyond them to play along with their own kind."

Ango was a dirty-green. "Sar was right. All Earthmen are alike," he snarled back. "Except Abbey, of course." He bowed in his direction. "But the rest of you let narrow patriotism and provincial hates becloud whatever civilized faculties you may have once possessed."

Bill Snead took a step forward. "Why, you... you—"

Well, it took Abbey a long time to bring us to a point where we wouldn't scrap it out right then and there. We finally agreed to a coldly sullen truce. We even stumbled out some apologies for what we had said about each other. But all the palaver in the Universe couldn't make me trust those Martians any more. Abbey was right; the cold of Ariel had frozen any friendship. It was all right for Enos Abbey—poor, trusting soul—to take their protestations at face value. I knew better. And so did Bill. He whispered as much to me. And that went double, I suppose, for what those birds thought about us. I could see it in their faces.

After a deal of discussing back and forth, we finally reached a modus vivendi. I was to go to the mines with Sar, and Bill was to stay with Ango at the impermo-screen. That way we'd be paired off all the time—Earthman with Martian—so we could watch each other for any sign of treachery. Old Enos didn't count. Bill and I naturally knew he was all right, and the Martians seemed to trust him, too. Abbey was that sort of a guy. Suspicion just couldn't cling to him.

He tried his best to argue us out of it, but it was no go. Finally he quit, but he looked pretty sick over the situation. He just moped around and looked at us with sad, reproachful eyes.

Bill whispered to me: "Don't you worry about headquarters, Jimmy. I can handle Ango any day in the week."

"And Sar won't be able to pull a thing," I promised.

But before we started for the mines—Sar and I—Ango said loudly: "Let's get this straight. As far as headquarters are concerned I trust Enos Abbey to see to it that nothing untoward happens. But out there at the mines, there'll be the two of you." He looked at me peculiarly. "I want it definitely known that both of you—Sar and Vare—are to return here for the sleep period together." He emphasized the last word.

Before I could say anything, Bill cut in. "That's O.K. with us. Either both come, or neither. If I catch sight of just one coming up that trail alone I'm turning the needle gun on him."

"Regardless of who that one is?" Ango demanded pointedly.

"Regardless."

IT WASN'T pleasant. The days passed, all of us keyed up to the breaking point, watching for the least untoward move. At the mines, where I went Sar was right at my side. When he went to talk to a troglo, I stuck to him like a bur. It was funny that we didn't once think how all this was affecting the troglos. The squat, deformed Venusians blinked at us with their great, staring eyes and chattered to each other in that guttural jargon that no human being has ever been able to decipher. But then, neither one of us considered them as fellow creatures, or that it mattered much what they thought.

So we kept circling warily around each other all the time, and spoke only when it was absolutely necessary. We sure were formal with each other. Naturally the work suffered. The troglos lazed along, doing minimum, and their chattering increased.

Sar got sore. He said to me with cold formality on the seventh day. "The troglos require a lesson, Mr. Vare. I suggest we cut off their supply of bassa leaves."

That was about the worst punishment we could hand out to the Venusians. Take away their food supply, and they wouldn't mind as much. "Suits me," I growled.

The days became a nightmare. None of us relaxed a moment, especially as the time grew near for the fleets to arrive. We didn't even have the consolation of knowing what was going on back in the home planets. Old Abbey kept the visor-screens resolutely closed. "You men are close enough to each other's throats now," he said, "without getting madder because of something that happened on Earth or on Mars."

But he forgot we had imaginations. I brooded about it. I saw all Earth a shambles; my sister dead and the two little boys with their brains dashed out. At such times I had to clench my teeth to keep from strangling Sar. I'd glare at him, and he'd glare at me with added interest.

The troglos went about their work sullenly. We had told them they'd be without the bassa for a week, pending good behavior. They muttered a good deal among themselves, but we didn't care as long as they kept on working. Besides, our minds were elsewhere. And each sleep period we trudged back together, silent, making sure that we were abreast as we came up the trail toward headquarters.

The tenth day came. The tension became almost insupportable. Already our electro-scanners had caught sight of the hurtling space fleets. They were coming up fast, angling toward Ariel at a terrific clip. About a hundred million miles separated them, and the Earth fleet had a slight lead.

Bill Snead forgot himself and let out a whoop when Abbey told us the startling news. If looks could kill, then the glares that he got from Sar and Ango would have stretched him out flat.

"Remember our oaths," Abbey appealed to us desperately. "We keep them both out, no matter what happens."

"You just heard Snead," muttered Ango. "What guarantee have we that when the Earth fleet pulls in—"

Old Abbey straightened his stooped shoulders. "I'm taking care of the impermo-screen alone," he snapped. "You and Bill are to remain in the common chamber. Do you trust me?"

"Sure!" declared Bill heartily.

Ango hesitated. "Yes," he said at last.

"All right, then. The first fleet will make contact in about five hours, Mars in about six. I'll be ready for them both. Meanwhile, get along on your jobs, Sar and Jimmy. You're late."

I didn't want to go, but one could not disobey Abbey that flatly. Sar trudged moodily along, keeping even pace with me. Not a word passed.

URANUS was a big, very thin crescent now, and the tiny Sun was close to the rim of the giant planet. There would be an eclipse shortly. What did that matter, though? In a few hours hell would break loose.

As we turned the last spur over the Everlasting Mountains, which hid the mines from us, I was suddenly aroused from my abstraction.

Three shafts had been dug into the lava facing. The tunnels slanted into the bowels of the mountain gradually, following the lodes. For a part of the way they were open borings; at each, about a hundred feet or so down, air locks had been installed, so that the troglos could work without spacesuits.

We were late, and by this time the troglos should have been going strong. There should have been little cars of ore trundling out of the depths to the smelters we had installed close by. Smoke should have been pouring out of the stacks and congealing into frozen particles immediately on hitting the airless cold.

But nothing stirred. Everything was dark and quiet in the shadowed twilight. Not a sign of a troglo anywhere, not a sign of life.

I quickened my pace. "Damn those troglos," I growled. "You can't trust them a moment. I'll bet they're still snoring away."

"They're sore because we took away the bassa leaves," said Sar.

"They'll be still sorer when I get hold of them," I snapped, and lunged forward.

In the semidarkness I did not see the thin metal wire that had been strung taut across the trail. It caught my shin, and I went over with a crash. My helmet struck sharp lava. Stars flashed all around me. Luckily glassite is tough; but the jar stunned me momentarily.

In my daze I managed one thought. What a swell chance this was for Sar to jump me!

Then I heard exultant screams, barbarous shouts in strange gibberish.

I twisted my head and stared upward. My heart stopped beating.

No. 3 shaft, which had been unused ever since the vein ran out unexpectedly, opened up on a ten-foot rise just above us. Out of its mouth swarmed the troglos, squat in their space armor, shoving before them an enormous rock.

Their broad, root-colored faces were triumphant behind their glassite helmets. Their thick lips smacked resoundingly within my receiver. The huge slab of gneiss poised over the rim. Behind it a dozen troglos heaved. It tottered.

I stared upward in horror. The rocking mass looked like a mountain to me. Even in the lessened gravity of Ariel it must have weighed at least a ton. When it fell, it would make a direct hit. I'd be squashed into a mess of mangled flesh and bone.

I tried to rise, to fling myself out of the way. But that cursed wire they had placed as a trap had twisted my ankle. And I lay in a shallow trough, so that I'd never make it.

Funny how many thoughts can race through a chap's mind when death breathes down his neck. Little incidents of my boyhood; a green, smiling field back on Earth; rage at Sar for having inveigled me into depriving the troglos of their precious bassa; a sick sensation that now Mars would triumph.

The rock began to fall, soundlessly, but all the more terrible in its silent rush. I closed my eyes. The bravest man in the Universe couldn't face death like that with his eyes open.

My shoulders wrenched violently. My spine twisted until it almost snapped. I felt myself whirling over and over like a spinning toy. The breath whooshed out of my body.

Then there was a terrific concussion. As though an earthquake had ripped through the little planet. And complete silence!

I WAS AFRAID to open my eyes. What had happened? Why was I not dead? Why didn't I hear the yells of the troglos any more?

Gritting my teeth, I forced my leaden lids open. I lay sprawled close to the edge of the trail, flung about a dozen feet from where I had first fallen.

The great rock had made a direct hit, all right. The stretched wire was ground deep into the sharp-crusted lava underneath. It still teetered back and forth on its unstable stance. A hundred pieces, of all shapes and sizes, ripped off by the terrific crash, lay on every side. And above, staring down at me with wide eyes of disappointment, were the troglos.

The sight of them drove every other thought from my mind. The dirty little beasts! Who'd ever have given them credit for such cunning hate? I jerked erect, heedless of the pain that went through my ankle like a hot surgical knife, unmindful of the fact that my body was a mass of aches all over. I'd show those damned Venusians!

Furiously my mittened hand went to an outside pocket in the space-suit. I brought out a small, dun-colored sphere, twisted the little screw that held it safe. I drew back my arm to fling it.

The troglos screeched in fear. Or rather, I saw their mouths open; the communication set in my helmet had been smashed by my fall. They knew what I had. They had seen it in action many times in the mine.

The sphere contained penta-nitrotoluol, the most powerful explosive known in the System. There was enough inside to tear down several hundred cubic meters of the most recalcitrant lava or gneiss.

They turned tail and ran like the fleet agrus of their native land back into the depths of the shaft. I could have caught them all in one great holocaust, but somehow my arm stayed poised to let them escape. After all, from their point of view, we had been brutal tyrants, treating them as something not quite as good as an Earth horse or a Martian dino.

I let them go, the fear of their native gods in their hearts; but I couldn't permit them to come out again after they regained their courage and take another crack at me. So I waited until I was sure they had scampered through the lock into the main body of the shaft; then I let fly.

The explosive did a good job. It blew in the whole face of the spur, burying the entrance under several solid feet of tumbling rock. That would keep the Venusians jailed until we decided what we'd do with them.

Then, as I turned painfully on my ankle, I thought for the first time of Sar. I found the Martian lying motionless and white a little way back on the trail. A flying fragment had pinned him down by the leg. Even as I heaved remorsefully to free him, I was crying out: "Sar, you old son, forgive me! You saved my life at the cost of your own. You shoved me out of the way, and paid for it. What a blithering idiot I've been! What damn fools we've all been!"

He opened his eyes then, and smiled weakly at me. He couldn't hear a word I was saying; his own set was smashed as well as mine; but his pain-twisted smile showed me that he knew that I understood.

"You're alive!" I whooped joyously. "Can you get up? We've got important business together back at headquarters."

He rolled his head slowly to one side. His hand pointed down at his right leg. I looked, and knew what had happened. Within the flexible material of the spacesuit the leg was crushed or broken. He wouldn't be able to walk; he'd have to be carried—and gently.

In despair I hobbled around him, leaning heavily on my metal-tipped rod as a staff to ease the pain of my ankle. It was a mile of nasty going on the trail, and I couldn't lift him, even in that lessened gravity, without having my own leg crumple under me.

Sar made signs to me. I could see he was suffering; his face was pale underneath the glassite. But I was to go to headquarters and warn them of the uprising, so the others could take whatever measures might be necessary.

"All right, old fellow," I said heartily, though I knew he couldn't hear. "You just stay put and I'll have them back in a jiffy with the rocket car, and you'll be packed to camp as though you were in bed."

We only used the rocket car for long trips over Ariel, rarely for this short run. It accelerated too fast, and there were landing difficulties. "And don't worry about the troglos," I added. "They're safely holed up."

He grinned at me affectionately; then he fainted.

I STARTED back over the tortuous, jagged trail. It was terrible going. My ankle must have been swollen to triple its normal size; and though I leaned heavily on the rod, every step was exquisite torture.

The shadows had deepened suddenly, and a weird purplish gloom settled over the fantastic terrain. I looked up. The tiny Sun was just going into eclipse behind the gigantic shoulder of Uranus. We had seen plenty of eclipses out here, but the sight of one always sent definite tingling along my spine. It was awe-inspiring. The quick drop in temperature—about sixty degrees in as many seconds, as the light cut off. The already glacial cold took on an added terror; the heating unit in my spacesuit required immediate stepping up.

Shivering and cursing my luck I stumbled wearily along. Within an hour or two the rival fleets would swoop down upon us. God knew what would be the upshot. And Sar was lying out there on the trail, helpless, alone, slowly freezing in the frightful cold. I was more than halfway down the trail; otherwise I'd have turned back to help him switch on more heat. An eclipse lasted several hours. But it was better now to press on and get help.

It was a nightmare journey. The weight of my lamed foot became more and more unbearable; every step sent waves of pain over me. But I kept on. At last I saw the low lift of the observation dome over headquarters. It was built of viscex sheathing, proof against radiation and stray meteors. In its rounded sides two thick quartz windows peered, with small, round slides through which needle guns could be thrust and sealed in instantly against escape of air by liquid sealing cement.

I forgot my dragging foot and raced forward with renewed vigor. In a few moments now the rocket car would go whooshing to the rescue:

Only quick action saved my life. I saw the sudden thrust of a needle gun out through the quartz, the pale-green, bitter face of Ango behind it. I dropped as though I had been shot behind a ragged outthrust of splintered lava. The next instant a needle of brilliant light passed directly through the spot where I had stood.

Cold realization flooded me. In my haste, in the warming knowledge that when the test had come Sar had been a true pal and comrade, and not an enemy Martian, I had forgotten that the others, locked up in the main camp, still distrusted each other, and us; that a pact had been entered into. I had come back alone, without Sar. To Ango that meant but one thing; that I had slain his fellow Martian, and that there would be two against one to destroy him also.

I shoved my head out from behind the shelter, and gesticulated frantically. In a momentary glimpse I caught sight of Bill Snead, his good-natured face lean with horror at my single presence, distorted with inner struggle. I knew Bill. He had agreed to kill either of us if we came back alone; he would live up to his word, no matter what it cost him.

Then I ducked back frantically. The needle gun loosed its long lance of death. The rock in front of me began to sizzle.

I cursed. Time was pressing. Sar lay dying up there on the trail; sooner or later the troglos would dig their way out; and space war would break out in mot too many minutes.

Yet every time I flicked my head out to try and make them understand what had taken place, that damned needle gun smacked at me. Ango was determined, and a good marksman.

At last I gave up, and started working frantically to fix my communications set. It took tall doing. I had to wriggle my hands free of their incasing sleeves and work with stiffened fingers in the cramped confines of the spacesuit. Luckily it was only a matter of a loose wire, but tightening took almost half an hour.

Then I started to talk, frantically, in hot haste. Ango wouldn't believe me. He thought it was a ruse on my part to gain admission so that between Bill and myself we could overcome him. But Bill finally got hold of Enos Abbey and brought him up from his vigil at the screen. Perhaps he believed me; perhaps he didn't. Pie looked pretty sick over it. Anyway, he decided that the matter should be investigated, and prevailed on Ango to stop taking pot shots at me.

But he wouldn't let me inside. Ango was taking no chances until he saw Sar.

"Get out the rocket car," I cried. "You can come back with me, Ango. That's fair enough."

"Oh, no, it isn't," he retorted. "The fleets are due any minute now; you'd have Snead in control of the screen. Enos Abbey will go with you; I stay here with Snead."

AND THAT'S the way it went. We overshot the mine several times. You just start the car and it hits a hundred-miles-an-hour clip in the first second. But after much maneuvering we managed to land on a little plateau just before the mine.

We hurried out—at least Abbey hurried; I could only hobble. We found Sar still in a faint; but Abbey, after a practiced look, said: "He'll be all right. It's shock, chiefly, and the cold." For an old man he was pretty strong. He lifted the Martian carefully on his shoulder and placed him in the warm interior of the car.

Then he turned and waved to me impatiently. "Hurry, Jimmy. We've got to get back. There's no time to lose."

But I had painfully scrambled up among the shattered rocks where I had tossed my explosive charge. I wanted to make sure that the troglos couldn't get out until we wanted to let them out. I was feeling pretty humble about them anyway. Abbey, mildest and kindest of men, had blistered me for what we had done. So my conscience was bothering me.

I heard Abbey's hail, but I didn't stir. Nothing in the Universe could have stirred me just then. The pentanitro-toluol had ripped off a great gash in the overhanging spur. And there, shining softly back at me in the eerie purplish light of the eclipse, ran a thick vein of phosphorescent armorium ore!

The old man came back impatiently. "What's the matter with you, Jimmy?" he said. "Are you star-struck? Sar needs attention, and I'm worried about what Bill and Ango will do while we're gone."

I just stood there, like a fool, pointing.

He took a quick glance, then he, too, became rigid. "Armorium!" he gasped. "The lost lode! Then our calculations were correct. It's just that there had been an upthrust of gneiss that split the lode. Only, instead of splitting it clean, as normally happens, it twisted it completely to one side."

He grabbed my arm. He was shaking, and it wasn't from the cold.

"Do you realize what this means?" he said hoarsely. "There's enough armorium down there to last for centuries."

I nodded dumbly. I couldn't talk, I was so filled up inside. There'd be no war, civilization could go on. Everything was all right again.

Then alarm seized me. "Hey!" I cried. "What about those war fleets?"

"Leave them to me," Abbey declared confidently. "I'll—"