RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

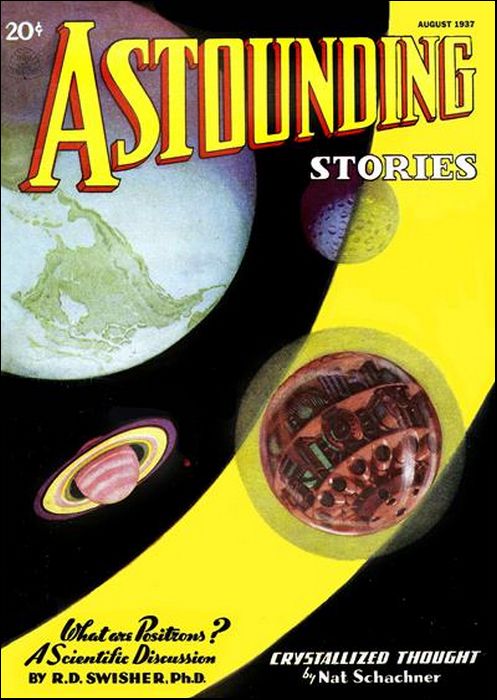

Astounding Stories, August 1937, with "Crystallized Thought"

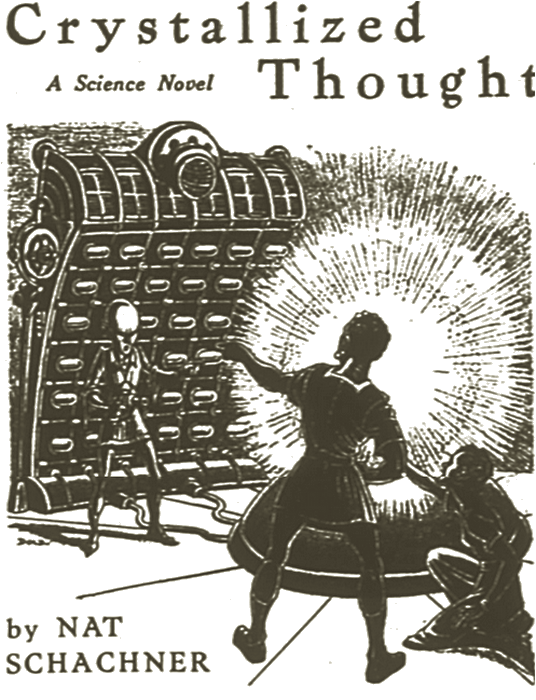

"Alive?" the Martian scorned. Earthman, you

are gazing at immortality—eternal power!"

WEBB FOSTER was the greatest scientist in all the solar system. This, at least, had been the consensus of opinion at the last assemblage of the planets. Webb, however, had protested the accolade and offered Ku-mer of Mars in nomination for the coveted honor. But Ku-mer received only two votes—his own and that of Webb Foster. Whereupon, with Martian blandness, he had retired from the conclave and left an undisputed field to his generous rival.

Webb Foster was sincerely sorry for him. He knew the proud sensitivity of the Martians, beneath their outward armor of indifference, and he tried to find Ku-mer after the members of the quinquennial meeting had scattered to their respective space ships. But Ku-mer was not to be found. He had vanished.

Whereupon Webb, with a shrug of his shoulders, and slightly flattered withal, returned to his space laboratory. This was famous throughout the system, and the fruit of years of contriving. Webb Foster required absolute isolation and profound peace for his researches into the origin of all things, into the fine structure of space and time and matter. These desiderata could no longer be had on Earth, his native planet.

Earth was a vast garden city with a population of ten billion humans. From pole to pole swift-moving platforms made an intricate network of intercommunication; underground, express monocars whined through vacuum tunnels; overhead, glistening planes darted along aerial traffic lanes; while from a thousand rocket ports great space liners took off for Mars, Venus, the Moon, and far-off Callisto, capital of the Jovian hegemony. A scientist, brooding on the very fundamentals, the ground plan of the universe, could find no peace on Earth.

So Webb Foster had built his space laboratory. It took five years and the unremitting labor of a thousand men. But when it was finished, the planets marveled, and his fellow scientists ached with possessive longing.

It was a great crystal sphere, a thousand feet in diameter. The material was plani-glass, a transparent composition of Webb's invention. Its tensile strength was that of fine-wrought steel, but its lightness greater than that of aluminium. In its normal state it transmitted all the beating waves of space without let or hindrance; when polarized, however, only the wave lengths of light could slide along the latticed crystals. Neither electricity, magnetism, X rays nor cosmic rays could force their lethal energies through the impenetrable barrier. A special repulsor screen, such as the space ships used, diverted plunging meteors from their destructive paths.

Within the vast concavity Webb Foster set up his laboratory. All the normal apparatus was there: huge dynamos powered by solar radiation, giant electrostatic balls, flaring electron tubes high as a building, mass spectrographs, a powerful photo-electric mosaic telescope, delicate immersion baths.

But besides this regular equipment were machines that Webb himself had fashioned: infinitely sensitive wave traps that tapped subspace itself, positron segregators, where those flash-vanishing ephemera of nature could be held indefinitely; strange spiral whirligigs in whose light-approaching speeds time itself seemed to have lost its forward march—and a myriad other complexes of ultra-science.

Nor did Webb forget the more material bodily comforts. At the very center of his space laboratory he placed his living quarters, wherein he studied and ate and slept and had his controls, like an alert spider at the core of his web. In his storage compartments there was always a sufficient supply of dehydrated food for three years of wandering, a thousand-gallon tank of water, and air-purifying machines whereby the atmosphere could be indefinitely renewed and kept clean and wholesome.

WHEN the great globe was completed, and stocked with all its multitudinous machines, twenty rocket tugs towed it from its Earth hangar out into space, set it upon a previously calculated orbit a million miles beyond the Moon, gave it the necessary orbital impetus, and set it free. Whereupon the space laboratory became a second satellite to Earth, revolving majestically around the parent globe in uninhibited gravitational flight, rotating slowly on its own axis to generate an artificial gravitational field within.

There, in the depths of space, flashing like a minor planet, the space laboratory went its way, using no power in its interminable orbit, granting to its master that isolation, that abstraction from mundane noise and crowding which no longer existed on any of the inhabited worlds. Yet, when he willed, a pulsing signal would bring a stubby, grimy cargo liner with the requisite supplies, or a space lock would open and eject a small, fast space cruiser piloted by himself. Nor was the great sphere itself devoid of directive motion. Jet-orifices studded its shining surface like crater pits, and sufficiently respectable speeds could be built up from the rocket-fuel tanks to take the giant laboratory even to the closer stars, if necessary.

Now Webb Foster returned with a sigh of relief. He jockeyed his tiny space cruiser into the silent lock, heard the convex panel hiss into position behind him, waited the required period until warmed air flooded the erstwhile vacuum inside, and stepped out eagerly. Already the conclave of the scientists was dismissed from his mind. Ku-mer's disappointment became a wavering mist. This was home—and there was much work still to be done, important researches temporarily interrupted by the meeting.

As the inner slide opened, a great face thrust itself suddenly into his own—a giant face, black as a starless night, grimacing with delight. A cavernous mouth yawned and a bull voice roared, "Welcome, master!"

Most Earthmen would have been taken aback and more than a little afraid of the monstrous apparition. But Webb looked up without surprise, and even considerable pleasure, at the giant, and answered cordially, "Hello, Stet! It's good to see your homely face again."

The giant grinned toothlessly. He towered over Webb a good three feet, and Webb himself was tall for an Earthman. Yet, though his bulk was ponderous, he moved with strange, cat-like swiftness, and the muscles rippled over his ebon form.

He was a Titan, a member of the troglodyte race who inhabited that largest satellite of Saturn under conditions of cold and airlessness that would have proven fatal to any other people in the solar system. It was a savage, desolate world, from which the space voyagers usually veered away with cautious haste; a world liable to erupt these giant Titans from their unseen burrows to obliterate a venturesome expedition.

Yet Webb Foster had visited Titan in search of radio-active elements beyond the Earth tables, and found evanium, No. 95 in the list—and also Stet! Stet was engaged in a desperate losing battle with a horde of his fellow tribesmen. Webb discovered later he had violated one of the obscure taboos of the planet. A few well-placed bursts of penetron shells had scattered the howling savages to their burrows, and Stet, more dead than alive, was hauled incontinently into the space laboratory. Webb nursed the poor Titan back to health and found himself with a devoted servant, an unshakable, loyal dog on his hands. And he learned civilized methods with surprising rapidity, became exceedingly deft with the machines and a tower of superbly functioning strength to Webb in more ways than one.

The problem of a name bothered Webb for a while. The Titan's native appellation was altogether unpronounceable to an Earth-bound tongue. Finally, he called him Stet—a word culled from a long-dead language—because of his quality of standability, so to speak. If Webb ordered him to hold a certain stasis, a certain given state of things until further orders, he had the comforting assurance that that situation, in Stet's hands, would partake of the timeless, would be abstracted from the general flux of normal events, until Webb gave countermanding orders.

WEBB let his eyes roam lovingly over the maze of apparatus—each machine stripped, lean, shining with hidden power; his nostrils twitched the pure artificial air like an ancient war horse snuffing battle. This was life; this was ecstasy. Already he was swinging down the slanting catwalk toward the central den, Stet lumbering behind. "Anything new?" he demanded over his shoulder.

The giant rolled his white-rimmed eyes. "Nothing, master." Then he screwed up his face. "That is—leastwise, Stet don't know. Been some funny flashes a-spurting from the Balto Dome, and they's been things fumbling round this old space lab."

Webb halted sharply. "What things?" he demanded.

The Titan scratched his shaggy pate. "Stet don't know," he confessed. "He saw jerky marks on the detector panel, heard signals in the amplificators——"

"Amplifiers, Stet!"

"Yes, master—amplificators. But Stet couldn't see nothing nowhere. Finally, the fumblings give up and go away." Webb frowned, thought swiftly. Balto Dome was the chief mining area on the farther side of the Moon—that is, the side eternally turned from the Earth. The Moon had been colonized for five centuries. It was the treasure chest of an exhausted Earth, the rich storehouse of precious metals and chemicals which had long since vanished from the parent body. A fleet of cargo boats trafficked regularly between planet and satellite, laden one way with heavy ore and returning with food, clothing, machinery and the essentials of life.

The first colonists had built great domes on the Moon's surface, within which all operations took place, and ventured out on the airless surface only for exploration, clad in flexible space suits. In the beginning the Moon had housed scattered mining communities of men only—then women followed their men; families were born, and the amenities of life crept into the pioneering crudities of the domes. A century before, the Moon had taken on itself dominion status, with its own ruler and a compact of amicable association with Earth. The parent planet had consented.

Unexplained flashes from Balto Dome? Could there be trouble down there? Webb stared at the mosaic analyzer of the telescope. The Moon seemed normal, quiescent. But Balto Dome was invisible; it was already around the irregular terminator. Fumbling—unseen vibrations on the surface of his retreat? Impossible! His instruments were sufficiently sensitive to have picked up even the light emission of a single atom, once it penetrated his repulsor screens. Furthermore, not even a penetron shell could have forced its way through the field so as to impinge on the plani-glass, and upon the detectors.

"Stet!" he said suddenly. "You're sure you made no mistake?"

"Yes, master."

Webb shrugged his shoulders and forgot about it. Wherein he made a serious error. For Stet had been trained to accurate perception, even though the theory of the instruments was far beyond his savage mind. Furthermore, the Titans possessed several senses beyond those of the other denizens of the solar system—senses still not fully explained. They knew certain things intuitively which even the finest of instruments could not detect.

DAYS PASSED—that is, days ticked off by an Earth chronometer. The great space lab swung around the Earth like a stone in a gigantic sling.

The Moon bared its arid surface, passed slowly through its first phase, as larger and lesser satellite went into conjunction. Balto Dome heaved into view again. Its smooth bubble of ferro crystal was blankly dark. The Sun was an incandescent, burning glass, a molten fury of light; yet, close to its blinding rim, stars gleamed with serene, pure gestures. The planets moved in normal paths; the nebula made filmy veils against a jet-black profundity.

Yet Webb saw nothing of this. The plani-glass was polarized, so that only the filtered light of a shorn Sun entered. The repulsor screens were on full power. He was isolated from the universe. He was furiously at work, concentrated on a certain research, mathematical in its nature. He lived in a welter of integrals and vectors and tensors. He invented his own terminology. He was seeking the fundamental formula, the set of equations that would hold the universe within its symbols. He barely slept; he barely ate. Only Stet's hovering ministrations reminded him of these necessities.

The days wore on and on. And the giant Titan grew more and more uneasy. There seemed no end to this particular phase of his master's concentration. Stet swung with his queer gait to the outer detector screen, gaped at the tiny intermittent flash which showed that outer-space signals were vainly seeking entrance, returned to the central cell to peep in hopefully at Webb. But Webb never once raised his head. And again Stet retired, grumbling, rolling his eyes. His orders were strict.

On the third Earth day the signal grew more insistent. It was a continual flash. That, to Stet's mind, meant something most urgent, unprecedented. Some one was making desperate efforts to contact Webb Foster. With a scowl of determination, the Titan retreated to the inner cell. He tapped gently. No answer. He tapped again, harder. Webb raised his head angrily. A beautiful equation had been forming in his mind; this interruption had scattered the essential elements.

"Haven't I told you time and again not to interrupt me?" he exploded.

The giant ducked his head submissively. "Yes, master."

"Then what in Pluto do you mean by——"

"Some one making signal."

"Let them!"

"But they been making signal for three jumps," Stet insisted. A "jump" was his term for an Earth day. "They must want master very bad."

Webb grumbled, arose unwillingly. Why in Pluto had he built this space lab if not to get privacy? He looked regretfully at his calculations. But already the tag end of the equation had fled from his clutching brain. He might as well find out who wanted him with such vehemence.

HE WENT up the catwalk, stood frowning before the detector screen. The signal was a mute, persistent flash. Still grumbling, Webb thrust open the polarizing unit. At once the little flicker of light became an angry buzz. Webb looked startled, plugged in. That particular pitch described only one thing—the tight, restricted band of the Planetary Council—the rulers of the solar system. Only in cases of the utmost emergency was it ever used.

An angry, yet much harried face sprang into view on the visor screen. Hyatt Forbes, Earth representative! He was a bald old man with thin lips, a bold, decisive, nose and eyes that were diamond drills. But just now there was mingled fear and relief in their depths.

"Thank Heaven you're still alive, Foster!" he gasped. "By this time I thought they had you, too.". Then anger overwhelmed relief. "Why the devil didn't you answer our call before this?" Webb looked slowly around the encircling screens. One by one, other faces swam into view—faces of diverse nativity, of different shapes and characters. The lords of the solar system—the all-powerfuls—the Planetary Council: Ansel Pardee, director of the Moon—browned to brick darkness by the unimpeded ultra-violet of the Sun, a rock-hewn, determined man, vigorous, abrupt, fit descendant of the early Moon pioneers from Earth; Zog, tribal head of Venus, a pale-green creature with slitted, lidless eyes, pouched cheeks in which a species of gills extracted oxygen from the water-drenched atmosphere of his planet; Ixar, scientist of Mars, ocher-red, impassive member of an ancient race, infinitely indifferent to life, habituated to a dying world of desert sand; Qys, lord of the Jupiter planets, who ruled the circling swarm from his capital, Callisto—bleached skin and saucer eyes, to catch tired light, betrayed the distance of the Sun from his domains. Interior volcanic fires warmed his four habitable worlds.

And on all the faces shone similar emotions: anger, fear, uneasy, wary suspicion!

Webb took his time in reply—deliberately. When he spoke, his words were cold. "You know, Forbes, that I resent intrusions on my privacy. It disturbs my work. As it is——"

"Hah!" grunted Qys of Callisto angrily. "Perhaps he had a reason for hiding from our sight. I told you——"

"Please say no more," Ixar of Mars interrupted with quiet gesture. "Webb Foster is right. He is a scientist. That is sufficient explanation."

"So were the others," Ansel Pardee, Moon director, interrupted brutally. "We're warning him for his own good."

"And for the good of the system," Zog of Venus squeaked softly.

Webb Foster waited for them to cease their rapid-fire ejaculations. He did not fear them, though they were all-powerful in the planets. He was Webb Foster, premier scientist of all the worlds, accustomed to going his solitary way. But his curiosity was aroused.

"What," he demanded, "is the meaning of all this?"

Hyatt Forbes' baldish brow was furrowed with trouble. "It started with the ending of the assemblage of the scientists," he explained.

"They all left with me," said Webb. "I saw them off in their space ships, heading for their respective planets."

"That is so." Forbes nodded. "But a half dozen never got there."

"Lost?"

"That might account for Koos of Venus, and Larsen of the Moon. They flew their own ships. But An-gok of Mars and Yb of Io went on the regular space liners. They vanished in midspace, without a trace."

"And that isn't all," declared Pardee abruptly. He seemed the angriest of the council. "Since then a hundred more—the best scientists of the system—have disappeared. Four days ago I lost Jim Blake, my No. 1 Engineer, right out of the Balto Dome! I haven't been able to get a lick of work out of the rest of them since. They're scared to death."

"THE BALTO DOME?" Webb exclaimed involuntarily. That was where Stet had claimed he had seen unauthorized flashes four days ago.

"So that surprises you, Webb Foster?" Qys of Callisto grunted softly, his white skin twitching, his eyes rounder than ever.

"You will please desist from such comments," Forbes declared sharply. "The council has already discussed that phase of the matter and come to a final decision."

"Ah!" Webb's eyes glittered; his lips tightened. "So I have been the subject of a council decision, have I?" he said slowly. "In other words, I am under suspicion."

"Not at all," Ixar of Mars murmured quietly. "It means only that our nerves are rasped; that, as scientist after scientist, the keenest minds of the system, vanished into nothingness, in spite of all protection, of all guards, suspicion was bound to flare up." He smiled the slow Martian smile. "We've even accused each other."

"Of what?"

"Of seeking to disrupt the council, of attempting to establish a personal dictatorship over all the planets. That is why the brains of the system are being removed—to make the path easier for the final attack."

"Do you believe that?"

The Martian's eyes slid around the circle of his co-rulers in the visor screen. "No, I do not. For none of the planets have been spared. It is my theory—and Zog of Venus and Forbes of Earth agree with me—that the danger lies from beyond the system. These men have vanished in spite of all safeguards. They have been plucked from the midst of the most sensitive warning instruments, without any vibration recording itself. This science is not of our planets. It must come from beyond. I fear"—and he paused to "let his words sink in—"that this is but a preliminary invasion of beings from outer space—beings invisible to our senses and instruments, beings possessed of a science mightier than any of our contriving. We are in a serious danger."

Webb grinned wryly. He thought again of the disregarded warning the faithful Stet had given him—of strange tumblings along the plani-glass. Had the invaders thought that he, Webb Foster, was inside? Yet that did not sound right. For Stet had seen and heard the fumblings, the gropings, on the detector screens. Whereas Ixar had just said A startling theory flashed across his mind. Perhaps the instruments had shown nothing; perhaps it was the mysterious extra-sensory equipment of the Titan which had apperceived the disturbance, and attributed it to the screens. Good Lord! In that case——

He swung around the circle of the visor screens. "Thank you for the warning," he told them grimly. "I shad! take the necessary precautions."

"We wish you to do more, Webb Foster," retorted Forbes. "You are the only one left in the solar system that can help us. We want you to trace this terrible business to its source. If what Ixar says is correct—and I think it is—we stand on the brink of some dreadful doom."

"I am merely a scientist," Webb pointed out. "You have your space patrols, your interplanetary guard. That is their job."

Forbes made a gesture of helplessness. "They've tried their best. Even now they're covering all the planetary spaceways, conducting a systematic search. And while they are searching, more men are being plucked from ships, from special underground chambers. They are being made a mock of; their formidable weapons are useless. Only your brains stand between us and disaster. If you should fail——"

"Thank you for an unmerited compliment," Webb interposed coldly. He knew he was still an object of suspicion. He could read the truth in the eye of Pardee of the Moon and Qys of the Jovian satellites. "There are others that are competent, or better, than I. I am extremely busy just now. Why not ask Ku-mer of Mars to try his powers?"

He caught the swift, blinking glances that flashed among them and wondered. Ixar took it upon himself to answer.

"Ku-mer," he said with quiet weariness, "was the first of the scientists to disappear."

Webb digested that. If Ku-mer, with all his vast resources, had been taken, then—— He looked longingly back to his inner cell. He had been on the verge of that ultimate, universe-shaking equation. Now it would be lost—perhaps forever.

"Very well," he said. "I shall do what I can. But," and he cut short their buzz of approval, "I must be permitted my own methods, without supervision and without hindrance. And the first of my requests is that no hint be permitted to leak out of this conference."

"Agreed," Forbes said hastily—too hastily, Webb thought. For he saw the scowl on Pardee's face, the fierce suspicion in the huge eyes of Qys.

"Do you wish," asked Ixar with delicate intonation, "a patrol of ships around your laboratory?"

"Not a one," he retorted firmly. "I want, above all, to be left alone."

WEBB FOSTER completed his preparations. They were simple. Nothing untoward showed on the surface of his plani-sphere. It is true that he polarized the surface, so as only to permit light vibrations to come through, but that was always done when he was at work. In the depths of his cell, however, he did this and that. Then he went calmly to sleep, a tiny pressure button concealed in his right fist. But first he ordered Stet to watch before the detector panel.

The huge black Titan goggled at him foolishly. "Master not going to make search like big council say?" he asked in hurt tones.

Webb laughed at his injured countenance. "No, Stet, I am not. As a matter of fact, I am going to let the invisible kidnappers come for me. I would rather meet them on my own terms." The giant grinned understandingly. "You make yourself bait, eh, master?"

"Exactly. Now get to your post and remember your instructions."

The next few hours were difficult to bear. Webb pretended to be asleep, his eyes closed, his breathing relaxed, his right hand sprawling in a natural fist. Unknowing who the enemy was, how he would strike, or what his powers, he was determined to avoid all suspicion of preparedness. But, most of all, he relied on the extra-sensory perceptions of Stet. He was certain that his instruments would not register the coming of the stealthy invaders, but he was just as certain that the Titan's strange intuitions would feel their presence and give him warning in time.

Webb had never known space to be so quiet before. And airless space is at all times the very acme of silence. No air currents stirred or whispered with dry leaves; no distant water murmured plangent tales; no insects hummed their strident song; no plants swelled with sap and expanded with little crinkles of sound. He was alone in the universe. Stet, watchful before the panels, might have been on distant Betelgeuse.

Webb was a brave man, but this endless waiting for the unknown was an unbearable strain. He wanted to open his eyes, to move his cramped limbs, to scream out. He did not.

Then, suddenly, a cold wind seemed to stir over his heated forehead. It was Stet's voice, whispering along the thin wire next his ear, its resonance damped so that it was inaudible a foot away. "Master! I hear fumblings! I see a light on the screen! Master!"

Webb set his teeth, counted ten slowly. It was the hardest work he had ever done in his life. Then he pressed his button. Bathed in a sweat, he opened his eyes.

The cell was diffused in a strange, unEarthly luminance. It was color, and it was not color; it was light, and yet it was darkness also. Webb had, by contacting certain concealed transformers of his own invention, brought all space waves, from the infinitesimal cosmic rays up to the mile-long Hertzian pulses, within the range of visible light.

The familiar central cell seemed something strange, remote. He seemed in a different universe. He saw through the dural walls, pierced the mazy dance of molecular vibration. But there was nothing else. His aching fingers, ready to press the button a second time—to create an impenetrable space warp around whatever it was that had come for him—relaxed. He uttered an oath. Stet had been premature—or mistaken!

SWIFTLY he launched himself out of the chamber, up the catwalk toward the detector panel. The ebon Titan stood before the darkened screen, his eyes rolling fiercely, his gleaming skin bunched with moving muscles, his great hands flexing and unflexing as though they were already winding joyfully around an enemy throat.

"See, master!" he rumbled hoarsely. "He make signal on detector; he make noises fumbling around. Stet go get him."

Webb stared. The screen was a blank quiescence; the infinitely sensitive instruments showed no tiniest sign of disturbance. Nor, strain his ears as he might, could he hear the slightest sound. Yet obviously Stet saw and heard.

"Where do they come from?" Webb demanded quickly. He had had too many evidences of Stet's perceptivity to doubt him now.

The Titan strained, cocked quivering ears. "Outside Lock No. 1," he declared. "Where ship is."

Webb tightened his grip on the little, innocuous-seeming button, heaved with left hand at the flame gun in his belt. "All right, Stet; we're going for him." The giant rumbled joyfully, jerked after him, stopped short with a grunt of despair. His black countenance puckered into woeful lines. "He gone now, master! He 'fraid!"

Webb believed him. and was himself afraid. For if the uncanny invader had retreated, it was only because he had known what Webb was about to do, had penetrated vibration screens and walls and space to know what Webb held in his hand, and what its powers were. How could one hope to fight an entity, invisible, all-seeing, to whom screens and thoughts alike were as a sieve?

Nevertheless, he raced up the swinging catwalk, hurled himself at the beleaguered lock, sprayed his deep-ray flash through the panels. Nothing untoward was there; nothing seemed disturbed. Grimly, Webb flung back to the control board, took the last desperate chance. He ripped wide the polarization, opened the plani-sphere to all space. He swung powerful search rays in great arcs—the space laboratory lay in the night shadow of the Earth—and watched with slitted eyes.

Suddenly, he exhaled breath explosively. Straight between them and the Moon, a tiny, two-seater space flier swerved and tumbled in mad anxiety to avoid the betraying glare. "There it is," Webb shouted. Yet even as he cried out, doubt assailed him. The flier to which his search ray clung with a bull-dog grip was no strange, other-worldish vessel. Earth was the site of its fashioning, and its handling was clumsy, inexpert.

Nevertheless, his lean hand darted for the switch that controlled the snouting penetron guns; his voice clipped into the microphone on the universal speech band. "Stop where you are," he ordered, "or I'll blast you out of space."

The tiny flier shuddered, rolled, quivered to a fumbling motion, parallel to his own. Alert, bright-eyed, Webb lashed out further orders. "Now come closer, slowly, carefully, with your magnetic grapple out, and attach to Lock No. 1. You'll find a signal light gleaming. But remember, make no false move. It will be your last, if you do."

Inexpertly, the little ship wavered forward, along the clinging search beam, obedient to Webb's instructions. Yet he permitted himself no relaxation, no absence of precautions. There was something puzzling about the flier.

The grapples flung out; there was a slight shock, and the strange little vessel clung like a leech to the elephantine form of the planisphere.

"Watch it closely," Webb told Stet. "At the slightest suspicious move blast on the repulsor screen."

"Maybe then shoot with big guns?" the Titan suggested hopefully.

Webb shook his head. "No. It will be enough to fling it clear. I'll decide then on the next step."

Flame gun in hand, Webb swung up the walk, slid open the inner lock, trained his weapon on the outer door while the air rushed in. Then he moved forward cautiously, past his own auxiliary cruiser, sent the outer panel whirring into its recess.

"All right, now," he spoke softly into a wall microphone. "Open up and come in, hands high."

At the most, he figured, there could be three occupants of the two-seater. His gun was ready. It spurted searing flame in a wide angle. He would have the jump.

Slowly, the other panel, of dull dural, slid wide. Webb braced himself.

HE CRIED OUT sharply in surprise. The flame gun almost fell from lax fingers. Through the gleaming chamber, from the depths of the other ship, came—a girl!

Webb swore foolishly. "Who, in the name of Plato——"

She swayed, stumbled toward him. "Thank Heaven it's you, Webb Foster!" she cried. "I thought at first it was—they!"

She was beautiful, and there was terror in her dark eyes. Her slender figure was graceful in the jaunty green garb of the Moon, and the clear, golden tan of her expressive countenance betrayed her origin.

Suspicion fled from Webb. His gun jerked back to his belt. "Take it easy," he commanded gently. "What were you doing out there in space, and who are they?"

She came closer to him. The terror seemed to slide out of her eyes. "I was on my way to Earth. I took off from the Balto Dome. About ten degrees out, a swarm of ships suddenly materialized. They were dead-black, strange, like nothing in the solar system. They tried to surround me. I—I remembered the queer rumors that are going about, and I turned and fled. They followed me. I was sure I was lost, when suddenly your search beam caught me—and they disappeared as suddenly as they had come. I am very grateful to you, Webb Foster."

Webb surveyed her keenly. She was enough to send any man's pulses pounding heavily. Her dark lashes flickered. She was, he decided coldly, lying. She was pretending terror, and she was watching him from under those maddening lashes to see how he swallowed her story. The tale of the black ships was a clumsy concoction. She barely knew the rudiments of handling a space flier; certainly she could never have given the slip to those against whom she was fighting. Furthermore, she was millions of miles out of her course, if her story were true.

Suspicion flared again. Was she perhaps the bait, attractive enough in all conscience, for the hidden entities who struck with impunity? What connection was there between her and the attempted invasion of only minutes before?

Nevertheless, he betrayed no outward sign of his unease. The game was obviously deeper than he thought. He would pretend to believe her story. "You're safe enough now," he said gently, "uh——"

"Loris Rham," she answered promptly. The name came very pat. It was not her own, he decided.

"Suppose," he suggested, "I escort you back to the Moon. Your parents will——"

Her eyes widened. There was real pain in them. "I—I have no parents," she whispered. Then terror flooded her eyes—false terror. "Oh-h, I'd be afraid. Those horrible ships must be waiting out there. We'd never have a chance."

Webb grinned tightly to himself. She was playing a game. She had made her point—to get inside his space laboratory, and she intended to remain. Why?

"Very well," he answered dryly. "I'll have Stet, my man, make you comfortable." The jetty Titan lumbered forward, grinning horribly from ear to ear.

He was famous throughout the system, but few had ever seen him face to face. The girl took a short, backward step, stiffened, smiled brightly. "I'd love it," she said.

Webb, watching like a hawk, approved silently. She was no coward, as she had pretended. Stet, faithful, loyal, was not exactly a vision of beauty when first encountered.

But Stet was looking elsewhere. His eyes glittered on the built-in visor screen. "Master!" he rumbled. "Another ship—coming fast."

The girl whirled with a little exclamation of dismay. Webb pivoted like a cat. Had he misjudged her? Had there been truth——

The search beam picked out a blood-red flier. It slipped through space at a hundred miles a second, overhauling the ponderous plani-sphere as if it were motionless in the void. It was Martian speed craft, the fastest things in the system. There were only a few of them.

Stet moved with incredible lightness to the nearest penetron gun. The yawning orifice swung on noiseless gimbals, trained dead center on the approaching vessel.

"Wait!" Webb called out sharply.

The girl was dismayed, without doubt; but it was surprise rather than fear that clouded her eyes. And she had spoken of black ships, many of them—not a solitary red Martian flier.

THEN his communication signal buzzed. He set it, waited warily. A voice leaped across the void—the voice of Ku-mer!

Webb Foster tightened his grip on himself. Was he dreaming? Ku-mer had vanished, the prey of the invisible invaders. Yet there was no doubt about his voice, and Webb now recognized the ship. The Martian scientist had taken off from Earth in that very flier.

"Webb Foster! Webb Foster!" Ku-mer's voice was hurried, anxious, quite unlike his usual bland repression.

"Speaking!"

"Good! I am in time then! You are in terrible danger, Webb Foster. I was afraid it had already struck. Make way for contact."

"Grapple on Space Lock No. 2," Webb heard himself say mechanically. There was much to be explained. He pressed appropriate buttons, flung out of the chamber, hurried along the swaying side platform to. the other lock. Stet was with him. But only as the slides opened, and Ku-mer, second only to Webb Foster among the scientists of the planets, tottered in, weak and gasping, did the Earthman remember. The girl who called herself Loris Rham had disappeared while his attention was fastened on Ku-mer's ship!

Ku-mer was ocher-red, like all Martians. Among that race of scientists, inheritors of an ancient civilization, lie was by universal consent the greatest. His hairless head bulged with profound thought and his eyes were wearied with the philosophic weariness of the Martians. Alongside Stet, even before Webb, he was puny, weak of limb. The Martians were not a strong race physically.

"Where, in the name of Pluto, Ku-mer," Webb demanded, "have you been?"

The Martian tottered, would have fallen had not Stet reached out a trunk-like arm, held him upright.

"I've been," he moaned, "to the ends of the system. I've been beyond Pluto, beyond the zone of comets, to a black globe known as Gar-Mando. Invisible creatures captured me on my way home to Mars, dragged my ship through the void with a speed beyond that of light. I beheld the dull black orb; I shrieked at the sight of what I saw writhing and heaving on its fearful surface; I lashed out in utter despair with all the fury of my rocket blasts. Something snapped; I wrenched free. I fled weary days back to the system, with every ounce of power cramming the jets, to give warning."

"It is too late," said Webb. "Already they have struck, again and again. You were not the only one, Ku-mer, to be seized; though you were the only one to return."

The Martian cried out, gripped the Earthman's hand. "No one else can hope to combat this horror which is invading our peaceful planets, but you—Webb Foster—you and this great space laboratory of yours. I know you have weapons, inventions, which you have guarded from disclosure. You alone can save the planets from utter, dire destruction. I tell you I saw them—have sensed dimly the mighty science of these denizens of outer space."

"You flatter me unduly." Webb smiled wryly.

"I do not," retorted the Martian. "The Conclave of Scientists has acclaimed you the greatest of us all."

Webb searched the ocher face for signs, found nothing but tremulous anxiety. "How about your own work?" he asked.

Ku-mer grimaced. "I work merely with the processes of thought with the physiology of the brain—stupid, useless research in the presence of this horror. But you—— It is fortunate you were not already taken."

"They tried," Webb assured him dryly, "twice. The second time was only half an hour ago."

The Martian's wizened face twisted in alarm. "Then there is no time to be lost," he urged. "We must not wait for anything. We must strike before they are able to strike again."

WEBB stared at him with veiled eyes. But his thoughts were active. "Yes," he muttered absently. "It is time."

The great Titan scowled, bent his huge black head, grunted something in his master's ear. Webb did not seem to hear. His eyes were fixed quizzically on an inconspicuous, shiny disk in the palm of his hand. In its gleaming depths was mirrored a scene. The central cell of the plani-sphere. The girl Loris Rham was moving swiftly but stealthily about its narrow confines, peering in slide cavities, poking in all possible corners, riffling feverishly among the sheets on which Webb had been jotting his world-embracing equations. How could she know that Webb Foster saw every move she made in the miniature visor screen he held in the palm of his hand?

He decided it was time to call a halt to her searchings. There were many things in that particular cell it was not good for snoopers to discover. He went rapidly down the catwalk, Stet at his heels, Ku-mer, puzzled, in the rear. The Martian had not seen their surreptitious glances at the little disk.

Webb Foster thrust open the panel suddenly. "I hope," he said suavely, "you have not had the misfortune to discover what you are searching for."

The girl whirled with a startled cry. The sheets dropped from her slender fingers. Her hand went to her throat. A tiny pulse throbbed with maddening beat in the warm hollow of her smooth, golden-tanned skin.

"Oh-h!" she said faintly. "I don't know what you mean. I—I was just a trifle ill; my nerves—— I thought I'd come here and lie down a while."

Ku-mer bowed formally. "This is indeed an unexpected pleasure," he murmured, "to find Susan Blake here. I know your father very well; his is an exceptional mind."

Webb stared. Susan Blake! The daughter of Jim Blake, the Moon engineer who had vanished with the rest. He had known, of course, that Loris Rham was a glib pseudonym, but he had not known who she really was. Webb Foster had been a good deal of a hermit. absorbed in his scientific adventurings; otherwise he would have recognized Susan Blake. She was the toast of the planets.

He rolled the two names speculatively on his tongue. "Loris Rham! Susan Blake! Very pretty names," he murmured.

The girl flushed, then lifted her head proudly. "Yes, I am Susan Blake. I used another name until I found out I mean, I came to you for help, Webb Foster. My father has been taken. I am all alone. I wanted you to find him."

The frail Martian made clucking sounds of sympathy. "Tsk—Tsk! Those devils caught Jim Blake? Too bad! He had a keen mind—a very superior brain."

The girl caught her throat again. Pain widened her eyes, "Had? Oh Lord, no! He is still alive!" Frantically, she clutched at Webb; imploringly her lashes quivered up at him. "Say you will help me find him. Please!"

Something stirred in Webb Foster's blood, something from which he had thought himself utterly immune. But his brain was a cold, intellectual instrument, standing a little apart, surveying him with sardonic amusement. It was the old, old game—as old as Earth itself, as ancient as primordial slime! Very well; let her think that she had fooled him. Was Jim Blake, by any chance, concerned in this business? He had heard tales of Blake! he was hard, ruthless, as most of the Moon colonists were.

Aloud he said, "We are going to find him now, Susan Blake." But there was a queer grimness in his tone that made her start, and caused the blood to ebb from her cheeks. He grinned sardonically. She understood what he meant.

LIFE in the space laboratory became a tangled web of suspicion, fear and electric danger. Webb, following Ku-mer's careful instructions, sent the great orb hurtling from its path around Earth and Moon, catapulted it like a shining comet over the spaceways toward the outer limits of the system. The void was curiously empty. The great rocket ships, the lumbering cargo liners, were cowering in the planetary ports, afraid to risk the terrors of the invisible invaders.

Only the police cruisers darted like summer midges in vain search, poking angry noses among the asteroids, within the waste places of the huger planets. They stared curiously at the rushing might of the space laboratory. It seemed a tremendous portent, a planetoid trailing mile-long blasts of blazing gases. They signaled for it to stop; they even sent warning shells in its wake. For the Planetary Council had faithfully obeyed Webb Foster's request; it had permitted no word of his mission to leak out.

But the shells fell short of the planisphere's tremendous velocity, or, meeting it at an angle, exploded harmlessly against the repulsor screen. Pursuit soon fell behind, and hard-bitten patrol captains swore and burned the ether waves to ground bases querying Webb Foster's loyalty to the system. They did not know of Ku-mer's presence within the hurtling portent; they certainly did not dream that Susan Blake was on board. Only Ansel Pardee, director of the Moon, had any inkling of Susan's mission, and, hearing of the planisphere's sudden flight to outer space, his brow darkened and his heart turned to ashes.

Within the space laboratory, Webb Foster turned a puzzled frown on Ku-mer. "About how far out is this black planet called Gar-Mando?"

"Six billion miles."

Webb looked at him queerly. "Our top speed," he remarked, "is five hundred miles a second. At that rate it will take us one hundred and forty days. How," he asked, "did you escape your invisible captors and return within three days?"

Ku-mer's face was bland, inscrutable. He had recovered his former poise, his Martian impenetrability. "I learned much during the period of my captivity. You forget, Webb Foster, that my particular field is the study of thought. Through constant practice I have enabled myself to attune my mind to the thought vibrations of others—even of alien entities. I learned something of their mighty science—especially of the secret of their locomotion. If you will forgive my short absence, I shall take the necessary measures——"

HE BOWED, glided from the living cells. Webb watched him thoughtfully as his frail, weak body mounted the swinging catwalk, disappeared into the lock where his little flier reposed securely. In fifteen minutes he was back. "Look at your speed indicators," he said softly.

Webb started. The wire-thin pencils of light were sweeping forward, arcing over to unbelievable slants. Already they were rushing through space at a velocity of two thousand miles a second, and acceleration was building up steadily.

"At twenty-five thousand miles per second," said Ku-mer, "we shall reach the black planet within three days."

"You mean——" exploded Webb.

"Within half an hour we shall achieve that speed."

He was as good as his word. Webb Foster stared with knitted brows into the electro-mosaics. It was incredible. The universe was a rushing wind streaming past the fury of their flight.

Qys, in his fastness on Callisto, swore unpronounceable oaths and sent tight-band code messages to his fellow members of the council. He was certain now that Webb Foster had betrayed them. Ansel Pardee, on the Moon, heard the warning and groaned. Susan Blake was being carried farther and farther away. He had not received the slightest inkling from her since she had started on her mission. Had Foster discovered her true identity—what her purpose was?

Within the hurtling plani-sphere Webb remarked casually to Ku-mer, "Just how did you manage it? My power loads show no perceptible increase."

The Martian scientist veiled his eyes. "How," he returned pointedly, "do you, my friend, achieve your effect of polarization?"

"Check!" Webb grinned, and asked no more. Ku-mer was joining forces with him to combat the alien invasion, but he was betraying none of the scientific secrets he had discovered.

The girl, Susan Blake, was a problem. Webb had given her privacy and living quarters in the farther cell of the central unit, and every sleep period he thoughtfully sealed her in.

She seemed gay, artificially so. She made it a special point to be with Webb whenever possible. She watched his every operation with veiled lashes, behind which the Earthman was sure a keen brain was probing. And she made no further mention of her father. He was disturbed—more than he cared to admit. He knew she was a spy; yet her mere presence, the utter feminine charm of her slender body, the heady wine of her long, slow looks, did things to his insides. He scolded himself for this sentimental weakness.

Yet his brain did not function when she was concerned as icily as it did with an essential problem in physics. He was following a fixed plan of action—or, rather, of inaction. This was to drift on the course of events, to do nothing positive, to permit all things to be done to him—and to watch for the main chance. Thus far the girl had come, Ku-mer had joined forces and was directing him to the incredible habitat of the invaders, and there had been certain tentative attempts to get at him.

He had no illusions; he knew he was in terrible danger; he felt that somewhere, within easy striking distance, the mysterious attackers were keeping pace with him, holding off for unknown purposes of their own. A slow grin spread over his face. Ku-mer had delved into the thought processes of his captors. Could it be possible that even now he was reading the depths of Webb's own thoughts?

THE GREAT SPHERE flamed beyond the last outposts of possible life. Saturn, with its whirling rings, lay far behind. Green-tinged Uranus, sad-eyed Neptune, and the sepulcher that was Pluto. Beyond lay shoreless space—unless, as Ku-mer had promised, the alien orb called Gar-Mando barred the path.

Within the space laboratory the tension grew. Susan Blake grew hollow-eyed and feverish, her last pretense at gayety gone. Webb caught her several times prowling among his possessions, and accepted gracefully her quick-witted responses. Once, he watched her stealthily entering the lock in which Ku-mer's vessel lay, saw her in his tiny visor screen, fumbling vainly at the sealed controls. The Martian held the secrets of his space ship well. With a grim smile Webb turned the little disk toward the sleeping scientist. He lay quietly in his bunk, unstirring; but Webb had an uneasy suspicion that underneath those motionless lids Ku-mer knew of the girl's prowlings, knew that Webb Foster was awake and watching.

Thoughtfully, Webb flicked off the disk, left Susan Blake to her vain spyings. Ostentatiously, he rolled over, as if restless in sleep, contacted a hidden wall panel. Invisible current flowed in a hollow shield around him. The tiny radiations of his mind beat outward, were circumscribed within the guarded area. Now he could think things out, without fear of disclosure. The Martian was his ally, but it was wise to withhold certain thoughts, certain plans——

"You're certain about the existence of the black planet?" Webb asked Ku-mer queerly. He had set and refined the various detectors of his rushing laboratory, but nothing quivered from the vastnesses ahead. Already the Sun was a pale, lifeless star behind, Earth and Mars forgotten dreams, and even Neptune a tiny speck.

The Martian's face betrayed no emotion. "Quite!" he murmured. "It is now only twenty million miles ahead."

"Then why," Webb demanded, "is there no sign of it as yet?"

"I did not tell you," Ku-mer said quietly, "but it is wholly invisible and self-contained—that is, until you approach within a million miles of its surface. The entities from beyond the universe have a mighty science of their own. They have bent light around themselves in a closed circuit. The radius of that circuit is a million miles."

Susan Blake flashed up with something of her old spirit. "You seem to know a good deal about these strange beings, Ku-mer."

The Martian scientist transfixed her with his regard. "I think I told you, my dear Moon lady, I possess some poor accomplishments in the probing of mind processes."

Webb tightened his lips. He seemed to sense a subtle threat in those velvet tones. Had Ku-mer penetrated the secret spying of the girl? Did he know exactly what she was after?

Susan shrank suddenly away, grew pale. Her eyes were wide. "I—I am afraid," she faltered. "We are heading into terrible danger. I want to go home."

"You are about five billion miles too late in your desire," Webb cut in sharply. "You should have thought of that earlier. Your little Earth flier, even if you were much more expert than you are, could never make it."

The girl took a deep breath. "I think," she said steadily, "I would like to try it."

"No!" The single syllable was explosive, curtly commanding. Webb looked at the Martian in some surprise. Ku-mer smiled blandly. "I mean," he amended, "that you are much safer here. Once beyond the confines of Webb Foster's laboratory, you will be caught. No doubt they are lurking, keeping pace with us. Only the mighty science of the greatest scientist in the system is holding them at bay."

Little puckers furrowed Webb's forehead. The Martian was mocking him. He was showing his hand at last. That meant only one thing: that——

Webb Foster took a step forward.

"You had better slacken your speed if you do not wish to crash," Ku-mer said conversationally. "We have arrived at Gar-Mando!"

WEBB whirled. There was no need to watch the detectors, nor stare into the electro-mosaic. Directly ahead, through the transparency of the plani-glass, light flared in a molten flame, died almost immediately—as though they had crashed through some strange barrier. And directly ahead, black as a starless night, lay the outer planet of Gar-Mando!

Its size was not great—its diameter was under a thousand miles—but its Stygian surface raised the hackles on Webb's flesh. The Martian had spoken truly. There were things upon it that were not good for mortal eyes to see—things that heaved and billowed in long, sinuous undulations, things that reared monstrous heads from an endless ocean of black, sticky liquid, and gaped with mile-wide maws at the rushing planisphere. Behind him Webb heard Susan's gasp and Stet's native grunt. They startled him into action. He sprang to the controls, jerked the throttles of his cushioning rockets wide, blasted the repulsor screens on full power.

Nothing happened!

No power surged in the great tubes; no red slashes of flame roared from the rocket vents; the evanium lumps on which he depended for sub-atomic energy were cold and lifeless in the central disruptors. A crash was inevitable!

But even as the girl screamed and hid her face, their headlong fall to the terrible, unknown planet broke abruptly. An irresistible current caught the great space laboratory in its grip, swung it in a long, dizzying spiral to the heaving surface.

Stet, his black countenance ludicrously twisted, rolled howling along the cat-walk. Susan Blake stumbled into Webb's arms, clung to him a moment in a tremblor of fear. Even in the lightning flash of events, Webb felt the supple warmth of her body, the strange intoxication of her beauty. His arms tightened. A moment she clung, then jerked free with a smothered cry. Was it fear, contempt, loathing, or——

Webb had no chance to know. For, from the farther side of the heaving planet, little space ships, black as the world that spawned them, came swiftly into sight. Ku-mer, miraculously erect, saw them come, turned to the panting Earth scientist with a little smile.

Webb Foster saw that smile and understood everything.

"So it was you, Ku-mer, all the time," he snarled, and dived for the flat little button that had been jerked from his hand.

"Don't move, Webb Foster," the Martian said calmly. The Earthman paused in mid-flight. In Ku-mer's fragile, red-veined hand a weapon pointed—a short-range blaster, sufficient to spatter them all into flying fragments, to smash Webb's finely balanced apparatus into irretrievable ruin.

The girl saw the threatening weapon and gave a choked cry. Stet, uncannily on his feet again, tensed his huge body for a smashing dive. A bull-throated roar vented from his throat.

"Stop it," Webb spoke sharply. The giant face screwed up in hideous protest, relaxed his quivering frame. Thereby Webb lost his chance of escape. For Stet would have died, but in the dying, his blasted flesh would have crashed into the puny Martian, thrust him off balance. And Webb Foster would have been master of the situation, have had the opportunity to put into play all the subtle defenses he had contrived for just such an emergency. Yet, even with that knowledge, the Earthman could not permit the sacrifice of his faithful Titan.

IN ANOTHER MINUTE the interior of the great plani-sphere swarmed with the henchmen of Ku-mer—the scum of the planets—men of the several worlds, outlaws from the decrees of the council, desperadoes carefully gathered from the spaceways, ready to slit a throat or scuttle a luckless freighter with the utmost nonchalance. They were perfect tools for the sinister, deep-laid purposes of the Martian.

In utter silence, Webb permitted his arms to be pinioned. Stet shook off the first of his attackers like an elephant surrounded by snapping dogs, but a word from Webb brought him to scowling, unwilling submission. The girl was not bound.

She stood a little apart, slightly breathless, her color heightened. If there was fear in her, it did not show; if there was triumph, it, too, was veiled by long, curving lashes.

The sphere swerved, sped not more than fifty miles above the black planet, parallel to its heaving depths. Clinging to the sphere, guiding it on its flight, were the black ships of Gar-Mando.

Webb's thoughts were divided: horror at the abysmal creatures whose nightmare forms swirled in the slimy seas beneath; bitterness at the way in which he had walked into the neat trap set by Ku-mer—and wonder about Susan Blake. In the beginning he had deemed her the emissary of the invisible invaders—for he had placed no credence in the fantastic idea of entities from beyond the system. It had been a toss-up whether she had come from Ansel Pardee of the Moon, or had allied herself with Qys, lord of the Jupiter Planets, in a sudden bid for power.

Then Ku-mer had injected himself into the picture.

With the knowledge of the girl's true identity, the whereabouts of her vanished father, Jim Blake, grew to certain proportions. Nor had the Martian himself been free from suspicion of collusion. But now——

"You had been preparing this coup a long time, Ku-mer," Webb said aloud.

The Martian bowed blandly. "Ever since," he admitted, "my researches into the essential nature of thought brought certain fascinating possibilities to light." Webb looked puzzled. "Thought?" he echoed. "What has that to do with your present thrust for power, your kidnaping of all those who might have been able to oppose your will?"

Ku-mer smiled thinly. "Soon you shall see," he promised.

But there was that in the words which stirred uneasy sensations up and down Webb's spine.

They were flying steadily, scudding the surface. So low did they skim that hideous monsters reared themselves from the tarry seas, snapped with mile-wide jaws at the hurtling sphere—jaws that could almost gulp its bulk entire between serried, crunching fangs.

SUSAN BLAKE broke her long silence. She faced the Martian steadily. "I made a mistake," she said in low tones. "I thought Webb Foster was in back of all this; now I find it is you. What have you done with my father?" Ku-mer surveyed her quizzically. "You are but a transparent child, Susan Blake," he said softly. "It is true you came to spy on the Earthman, but you suspected me almost at once. Do not imagine I did not know that you were vainly trying to penetrate the sealed secrets of my flier. It suited me to let you fumble on and on."

"Oh-h-h!" The girl stared at him wide-eyed. Anguish was in her voice; her studied pose destroyed. "Answer me!" she cried. "Where is my father?"

Ku-mer smiled. It was not a pleasant smile. "Have comfort, child. You shall see him soon. He is on Gar-Mando."

She gulped and swayed. "Thank Heaven!" she whispered. "He is alive."

"Alive?" queried the Martian. "More than. that. He is immortal!"

Webb Foster again felt that nameless shiver pass over his body. Ku-mer's words were cryptic, but they held sinister undertones.

All further speech, however, came to an end. For, in the distance, a huge island heaved into view. It was the only land Webb had seen in all their tong flight around the strange black planet. And as land it was almost as forbidding, almost as dreadful, as the pitchy sea from which it reared its gaunt, steep flanks. Almost two miles high it jutted forth, a vast mountain massif, its sides perpendicular rock, black, unscalable, against whose smooth thrust the frightful monsters flung themselves and subsided with angry hissings, lashing the sticky liquid to a viscous, dirty foam.

On board the plani-sphere Ku-mer's henchmen sprang to their tasks under the Martian's soft-spoken commands. The black-beetle fliers quivered with sourceless power, swerved their gigantic tow aloft, braked its swift motion.

Gently, like a floating feather, they dropped to the surface of the island. It was curiously barren—a solid ledge of rock, smooth as a lava flow, its surface interrupted only by a set of buildings, low in height, sketchy in design, and obviously hastily constructed—typical pioneer buildings, for eating and sleeping, such as might be found on those of the asteroids where mining operations were in progress.

But two of the sprawling structures could not be classified so easily. One held Webb's straining eyes only momentarily. This was evidently Ku-mer's laboratory, the place in which he labored at his subtle psychological science. But the other!

It was small enough, and simple enough—in fact, a mere transparent dome, a semi-bubble set on the arid rock. Yet within its clear rotundity something sparkled and glittered. So sparkling, so glittering, that the great light dazzled Webb with its intensity, blinded him at first. It might have been a huge diamond, so pure and lambent were its rays; yet there was something else about it, even at that distance——

"What, in the name of Pluto, is it?" he gasped.

Ku-mer followed his captive's stare, and his own eyes flamed with light.

"That," he said in a hushed voice, "is my masterpiece, the fruit of years of ceaseless toil, the means by which I, Ku-mer, shall gain control of all the solar system." He turned slowly to the Earthman. "And you, my dear Webb Foster, whom the scientists chose as the greatest of them all, will add the final touch to my masterpiece, the final fillip necessary to consummate my plans."

THE COLD WIND of a strange premonition shuddered over Webb. "You know very well, Ku-mer." he rasped, "that I placed you in nomination for the honor."

For once the Martian's impenetrable surface cracked. His ocher face was a snarling mask. "That, Webb Foster," he mouthed, "was the ultimate insult. You knew quite well they would not vote for me. You pretended a magnanimous gesture—for me, the greatest scientist who ever lived. For that you shall pay; for that the whole system shall pay."

Suddenly, his face smoothed out; he was once more his usual, inscrutable self. "Forgive me, Webb Foster, for this silly outburst. It is unbecoming to me—the supergenius of the universe. In fact, I shall take pride in displaying to you my tremendous discovery. You are probably the only one in all the planets who can understand it. I attempted explanations with the others. The explanations left them sadly befuddled. Regretfully, I was compelled to cut them short."

The great space laboratory rocked gently on its unstable base. At a word from their Martian leader, the outlaws hustled Stet. out upon the bleak surface. Bound as he was, it took ten of them to force his great bulk along. Roughly, they pushed him into one of the buildings.

A smirking Venusian approached Susan. She flung his scaly green paw away with a shuddering gesture. "Don't you dare touch me!" she cried.

Ku-mer spoke sharply, and the Venusian shrank as if he had felt the lash.

Webb, tense against his bonds, relaxed. Whatever else might happen, the girl at least was safe from physical indignities. Ku-mer himself was notably ascetic, and the Martians were proud of their racial purity.

"You will not be harmed," Ku-mer assured her. "I have no need for women. Their brains are not—— But proceed through the lock, if you please. And you, too, Webb Foster." He gestured significantly with his blaster. "I shall be watching you; so shall my men. And remember, there is no escape from Gar-Mando."

Webb, stumbling through the narrow port, could well believe it. In all the Stygian planet there was but this solitary bit of land. All else was inky ocean, swarming with a nightmare life. A wan light beat on sea and land—a diffused glow inherent in phosphorescent air. Above, the bowl of sky was gray, finite. Light swung round and round in endless circles.

"A mere matter of magnetic deviations, controlled from my laboratory," the Martian murmured. "Gar-Mando was open to the solitudes of space before I came. I deemed it wiser to roof it in with invisibility."

"How did you discover this outpost of the system?" Webb inquired. "No one had ever suspected its existence."

"A certain pirate from the Moon blundered upon it unwittingly while fleeing an especially rigorous space-patrol pursuit. He recognized its possibilities, utilized it as a base for long forays upon the Jupiter satellites.

"Three years ago he was foolish enough to come to Mars for an interlude. He drank too much. I heard him. He sobered up—but I found means to make him talk. His followers decided to enlist under my banner. It took me a year to make the trip both ways, but I was enabled to establish the first transliteration of my matured theories." He smiled thinly. "The material was inadequate—chiefly members of my band who unaccountably disappeared—but it gave me my first start. Since then, through the kindness of the system's best brains, I have considerably improved my work." The smile tightened. "You, my friend, will have the glory of adding the final touch to my masterpiece."

WEBB stiffened, said nothing. There was something horrible in the offing, something related to that dazzling entity within the farther dome. He stumbled on.

Susan Blake was at his side. Her dark head inclined to him; her eyes implored his own.

"I—am terribly sorry, Webb Foster," she whispered swiftly. "It is all my fault. I—I allowed Ansel Pardee to infect me with his own suspicions of yourself. My father's vanishment left me frantic, eager for revenge. Pardee outlined the scheme. He thought it might work." She made a hopeless gesture. "Instead, I ruined your plans, brought you to this horrible place. Forgive me. My father——

"Do not blame yourself." Webb told her gently. "I knew you had come as a spy. I let you go on, thinking to find the truth between you and Ku-mer. I permitted him to catch me off guard."

The Martian and his men herded them through a panel in the bubble dome. Webb blinked his eyes. It was almost impossible to gaze steadily into the heart of the great shining orb before him.

"What do you make of it, Webb Foster T Ku-mer asked ironically.

Webb stared from under narrowed lids. It was an incredible thing. As sight grew clearer, he beheld its fine structure. It was not a single crystal, as he had first believed; it was a conglomerate of separate crystalline forms, each a perfect octahedron; and they moved in swift, circling orbits within the outer round of racing crystals that held them all within circumscribed limits. The surfaces of revolution were each distinct, like the layers of an onion, but the paths described were not haphazard. They formed an inner symmetry, obeying laws of their own, weaving an intricate, yet orderly pattern in their flight.

Webb stared, and as he stared, the hair stirred on his head. For these were crystals such as he had never seen before. Each glowed with a strange, pulsing sheen; each moved and stirred within its depths with a warm, singing flame; each seemed a flashing eye that stared back at him and changed its hue with subtle, infinite shades of feeling. The Earthman felt strange, impalpable fingers plucking at his brain, stirring forgotten neuron paths, sending ghostly images into his innermost thoughts.

"What do you make of it?" Ku-mer repeated.

"Why, it seems alive!" Webb gasped.

"Alive?" the Martian scorned. "Earthman, you are gazing at immortality—eternal power!"

WEBB FOSTER was shaken to his depths. Those invisible fingers were still probing his mind, mercilessly, coldly, draining him. A dreadful suspicion grew upon him, vague, inchoate. But it was Susan Blake who, with the swift, mysterious intuition of womankind, discovered the incredible truth.

Her eyes were fastened on the shining race of tiny crystals with a strange intensity; her lips were parted with panting breath; her cheeks had paled to colorless tissue. She staggered, swayed. "Father!" she cried in toneless accents. "Where are you?"

"By the three rings of Saturn!" Webb gasped. Little shards of suspicion were fast falling into an unbelievable pattern.

"Ah!" Ku-mer breathed. "So you are both beginning to understand. The girl by mere intuition; you, by an effort of the imagination."

The Earthman was overwhelmed. Though his eyes smarted with pain, he could not withdraw his gaze from the shifting maze. "Good Lord! Do you mean that Jim Blake is—somehow—in that pulsing orb?"

"Not only Jim Blake, but a hundred others as well—the scientific brains of the solar system, the men who have—er—vanished. I have made them immortal, eternal, and. in return, they are yielding up to me all their knowledge, all their thought processes."

"But it's impossible!" Webb blurted out. His head was spinning. "How could you have transmuted them?" They had been his friends, co-workers, most of them, and now they were a single conglomerate of tinkling crystals.

Susan Blake, with a little sigh, quietly collapsed in a faint.

The Martian's face twisted with scorn. "I am disappointed in you, Webb Foster," he said contemptuously. "Perhaps you will not prove as valuable an addition as I had thought. You still do not grasp the beauty of my work. I was not interested in these men as individuals.

It was as thinking machines that I wanted them.

"For twenty years I labored on my theories. Thought, I knew, was the lever by which life had elevated itself above the brute dance of atoms and electrons. Thought is all-powerful, a subtle, shining weapon with which to mold the universe to one's own desire. But evolution had stumbled. It had imbedded this magnificent instrument in a mold of sordid flesh, of slimy tissues and clotting blood wherein it is lost, scattered, fumbling darkly, subject to ills and pressures and pains not of its own.

"For thousands of years the beings of the various planets bewailed this condition, but deemed it inevitable and inherent in the very structure of thought. For thought, they told each other gravely, was but an electrical disturbance, an interplay of potentials between protoplasmic tissues in the brain. Destroy the brain, and the neurons of which it is composed, and thought dies with it, vanishes into nothingness."

"But the scientists of all the planets long ago proved that to be so," Webb protested.

"The scientists," Ku-mer snapped, "were a pack of fools. I am the first real psychologist. You are a physicist, yet you parrot such nonsense. The fundamental base of all your work is the great law of conservation—that nothing ever vanishes. Matter may change to energy, energy to matter, and both may shift their external forms, but the sum total is always constant, always the same. You must realize that."

"That is true," Webb admitted doubtfully. In spite of the dangerous situation in which he was, in spite of Susan's sprawled, motionless body, he was listening intently.

"Why then," the Martian continued triumphantly, "should thought, the highest, most complicated form of all in the entire universe, be the single thing to flash into being and flash out again without a trace? Thought, I insisted, must be permanent, durable. Then it couldn't be merely a matter of evanescent potentials. I went to work. For ten years I labored in my Martian laboratory. I used innumerable animals—the aakvelds of Mars, the mice and guinea pigs of Earth, the ytors of Venus." His smile was bland. "Yes, I used more advanced subjects—men of the planets of no particular importance, men whom no one missed.

"IT TOOK YEARS of heartbreaking toil, of innumerable initial failures. I removed the brains from the living creatures, kept them alive in saline solutions. There I subjected them to every conceivable type of stimulus. Finally, by using an electrical current of weak voltage but tremendous amperage, I found certain shining crystals oozing out of the tissues, moving to the cathodes. I purified these by fractional distillations, and tested them in a fever of anxiety. I implanted those I had obtained from Earthmen into the brains of mice, and behold, the mice spoke the language of Earth, displayed all the grades of intelligence that men of Earth possess.

"I had isolated the pure principle of thought; I had proven it to lie a crystalline structure, of an atomic weight below that of hydrogen. It is the fundamental element of the universe, the substratum underlying all things. Long ago, certain metaphysicians declared the universe to be composed of thought; I have shown their mystical conceptions to be true."

Webb steadied himself with an effort. One part of his brain—the coldly scientific—knew this to be the greatest discovery of all time; the other part—the warmly human—realized the awful implications of what Ku-mer had done. Horror grew on him as he watched the whirling sphere of crystals. Each crystal was elemental thought; each crystal represented the painful evolution of uncounted aeons, each crystal was the life-in-death of a great scientist, of an erstwhile living, breathing human being!

"You have done a fiendish thing, Ku-mer," he said quietly. "You have perverted a truly great achievement to devilish ends. In your lust for power you have forgotten the suffering, the torment of these men whom you have cold-bloodedly dissected. You have forgotten that they had friends, families"—his glance flickered painfully to the still unconscious girl—"daughters. What can you gain to justify this horror?"

"You disappoint me," the Martian said regretfully. "There had been a time when I, too, believed in Webb Foster's greatness. Now I see you are but a fumbler, a mouther of stale emotions and cloudy phrases. What were these men? Mere mortal beings, alive for a few futile years, then condemned to rot eternally, their thoughts a moldering, scattered part of them. I have taken their minds, purified them of all dross, given them immortality, power, splendor. What happier fate could they desire? What more blessed state could you wish?"

Webb knew what he meant. For a fleeting moment he shrank, appalled, from the idea that he, too, was destined to be but an endlessly circling swarm of crystals within the shining sphere. Then he stiffened. "Thought," he answered quietly, "divorced from its human concomitants, emotions, desires, fumblings if you will, must prove a terrible instalment. Eventually, it must destroy its possessor."

"You speak nonsense," Ku-mer cried angrily. "I have found the means to control it, to force it to my will. See!" He darted to an instrument set in the curving wall of the dome. It consisted of a tessellated pattern, a gigantic checkerboard, each square of which was a vacuum tube. From it, wires trailed to the turntable on which the sphere of crystallized thought spun and whirled. Above the pattern bulged a complex of grids and transformers terminating in a mesh-type speaker. To one side, a delicate microphone was set into the apparatus.

THE MARTIAN stood before the microphone. "This," he stated, "is my control board, my method of communication with the fused pure thought of a hundred great minds. Already, through them, I have achieved a power plant which taps the stresses and strains of space itself for unlimited energy; I have bent light waves in complete circles around this planet, myself and my space ship, and utilized the resultant invisibility to capture more of the brains that I required.

"Had it not been for the extra-sensory equipment of your Titan, I would have seized both you and your space laboratory without the deception to which I was forced to stoop. Through the combined intensity of these minds, and yours, I shall gain the power I require to force all the solar system to my will. I shall become its sole ruler, its giver of laws. I shall be supreme!"

"Nevertheless, I still say," Webb declared stubbornly, "that the thought you have removed from its natural context will eventually destroy you."

Ku-mer laughed without mirth. "You are wrong, my friend. Watch, and I shall show you how it works." He spoke quietly into the microphone. "Give me the fundamental equation that expresses the universe entire."

Webb started, jerked against his bonds. This had been the problem on which all his energies had been concentrated at the beginning of this strange adventure.

Little wheels commenced turning within the apparatus. Lights flashed on and off. The sphere of crystallized thought took on a deeper hue. Its speed of inner rotation increased. The singing sound grew in volume. It became a chant, a mighty melody that filled the dome and fled beyond the phosphorescent air. It beat against the black, dismal cliffs; it lashed over the turbulent, monster-haunted flood of Gar-Mando; it sent the hideous creatures scuttling into the depths. The whizzing crystals spun on individual axes; they pulsed and glowed with a myriad rainbow hues, flashed with unbearable flame.

The distilled thoughts of the hundred mightiest minds in the universe were concentrating on the problem proposed.

Ku-mer's voice cut through the din. He was smiling a self-satisfied smile. "I have asked them the final question, the most difficult of all. Yet I know they will solve it. With this equation, all things will become self-evident. The universe will be an open book. Travel to the distant stars, entry into superdimensions, control of elemental forces, the secrets of time and space themselves will be within my grasp. I shall become a superman, a god!" The feeble Martian body shook with the passion of his desire. His eyes glittered with devouring anticipation.

The shimmering sphere increased its pace. It rolled itself in a fury of concentration. Then there was a soundless burst of flame; the colors ebbed and faded; the tremendous speed slackened. Ku-mer rubbed his hands in an ecstasy of impatience. "Now I shall know—the ultimate he whispered.

A voice issued from the speaker. It was passionless, unhuman, the transformation of vibratory thought through the tessellated tubes into mechanical sound. In spite of himself, Webb strained to listen.

"We have merged our entities in the solution of this problem; we have concentrated our energies as never before. We do not know the answer."

KU-MER breathed convulsively. His red-veined fingers were clenched. "You—essences of pure intellect—the product of a hundred mighty minds—cannot solve the problem?"

"We cannot."

Ku-mer made a gesture of despair. "Is it then impossible of solution?"

"No. There is an answer."

Ku-mer's voice was choked. Webb Foster, in spite of himself, was a taut bowstring, waiting. "Where may I find it?" the Martian asked hoarsely.

"From one who is still alive—still cloaked in encompassing flesh."

"Give me his name."

There was a moment's hesitation. The sphere flared up, died down again.