RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, June 1937, with "Earthspin"

ON AUGUST 16, 1955, the emperor of a certain small but heavily populated and even more heavily armed country delivered his ultimatum to a startled world. "We must," quoth he, "have room to expand. Our national boundaries have long since ceased to be sufficient; our land has been ravaged by alternate floods and droughts until it is no longer capable of supporting our people. Too long have we been confined and hemmed in by the jealous nations. We are virile; we are fertile; we do not intend to stand such envious discrimination any longer. We demand colonies in which to grow and breathe; we demand our place in the sun."

And, immediately, the saber rattled in its scabbard, the green-clad troops prepared for war; tanks lumbered into formation; great battle planes hid the sun with their numbers; grim, gaunt cruisers got up steam. Impending war hung like a thundercloud over all the earth.

The United States and other great nations called a hasty conference. Diplomats hid uneasy thoughts under long-practiced, inscrutable masks; foreign secretaries looked harried; chiefs of staffs planned campaigns, shook impatient heads and planned them over again.

There was a quick hush when the American Secretary of State rose to have his say. All during the heated morning session he had kept silence, while the others wrangled and argued. Now he was going to speak. Elliot Dodd was a man of few words.

"We must be realistic," he said quietly. "This is no time to discuss ethics, matters of abstract rights and wrongs. A situation confronts us; it must be met. The emperor has delivered an ultimatum. He is prepared to back it up with the only language he knows: force, war! What are we going to do about it?"

"Crush him!" interjected a gold-laced general. He made a significant gesture with two fat fingers. "Like that!" Dodd let his calm eye drift over the tense assemblage. "Yes," he said, "I take it that we could do it. And perhaps that may be the only ultimate solution. But has the worthy general, the rest of you, counted the cost? The emperor has prepared long and secretly; most of us have simply drifted in the matter of armaments. His scientists are among the best in the world, and all their energies are devoted to his service.

"We could win—yes—but in the process millions of men will have died; famine and disease will have ravaged the world, and civilization have returned to the dark ages. Perhaps it might be wise to meet him halfway, to yield some of our surplus colonies to the settlement of his overabundant people."

Britain's foreign minister shook his head hastily. "Britain, for one, has none that it could possibly give up without grave consequences," he declared.

"Nor has France!"

"Italy, my friends, has but too few as it is."

The quick disclaimers of other nations spread around the council table. It was an excellent plan, they all agreed, but not for themselves. Their colonies were sacrosanct, were special cases.

Dodd smiled wearily. He had not expected success. "It seems then," he began—and stopped. The door of the council chamber slid smoothly open. A startled attendant peered in, announced: "His excellency, Count William!"

MARK ALDEN jerked his head up with the others. His keen glance, veiled to hide his hammering thoughts, swept the gaudy resplendence of the intruder. Mark sat unobtrusively next to Elliot Dodd, his official position that of secretary to the American secretary of state. Actually, he was the eyes and ears of the American government, the delicate probe on which it relied to discover the skeleton facts that lay enswathed under the clouds of diplomatic verbiage.

"Had the emperor become impatient?" Mark wondered. "Had he sent his notorious minister of propaganda to throw down the gauge of battle to the assembled nations?" Outwardly, Mark relaxed in his chair, with sleepy-seeming languor, waited for the dynamite to explode.

But Count William had come with no dynamite. His bull neck was supple, his smile was ingratiating, his voice obviously tempered from its natural bellow. "You have not come to a decision as yet?" he asked softly.

"We have not," Dodd retorted with some acerbity. "This unseemly haste is——"

The count spread his fat fingers placatingly. "The emperor," he said with smooth unction, "is anxious for peace with his neighbors. He has felt that you might have difficulties; he has therefore sent me to iron them out, to moderate his just demands so that all may be friendly and neighborly again." Mark tensed every faculty, though he seemed to lounge with careless indifference. What new deviltry was the emperor up to now? A similar suspicion stirred uneasily through the others. They had witnessed his tactics too long to be taken in again by words.

"Come to the point," Dodd snapped. William clicked his heels, bowed. His voice had never been so oily before. "The emperor realizes that there would be a natural reluctance on the part of your great nations to yield your inhabited colonies, with their populations and natural resources. He therefore proposes an alternative—one that he is certain you will be glad to meet."

The assembled delegates braced themselves for the blow. But when it came it left them gasping, bewildered with mingled incredulity and relief.

"He asks but the barren, uninhabited continent of Antarctica," the count declared surprisingly, "that sterile region of snow and ice where no human being has lived and where it has long been taken for granted that none could ever exist. He asks but that, and a modest additional area of fifty thousand square miles circumscribing the other pole, an even more barren and dismal territory. Surely these are but small exchanges for his just demands."

Even Dodd, the eternally calm, stammered a bit in answer. "But in Heaven's name, Count William, what does he wish with these dismal regions?"

William surveyed them with a queer glitter in his eyes. Only Mark, trained to pierce the very wrappings of the soul, noticed that glitter. "Our countrymen," he explained, "are a virile, hardy race. They are not afraid to brave icy blasts and inhospitable conditions. They require but room to expand, space in which to develop their innate genius. On the continent of Antarctica are almost 4,000,000 square miles."

Sensation reigned. Had the emperor gone mad? Well, if he had, so much the better. Those nations which held vague claims to the frozen wastes were content—nay, eager—to yield their pretensions, and thus avoid a world war in which the victors would be equally ruined with the vanquished. The ethereal waves, the cables, burned with code messages to the home governments. Swift consents burned their way back again.

The documents were formally signed; to the emperor was given formal title to all the continent of Antarctica, to the tiny area of the north pole, involving but a sea of ice and some glacier-covered islands, besides the northernmost tip of Greenland. The diplomats rubbed their hands in glee. They had done an excellent piece of work, they felt. The emperor had gone suddenly mad and they had taken advantage of his condition. They held a great banquet; they toasted Count William and his absent emperor.

William accepted their protestations at face value—or so it seemed—and departed for his native country, the useless document carefully sealed in his portfolio.

BUT one man could not get rid of a sense of strange unease. As the fast cruiser swept over the turbulent Atlantic, bearing the American mission home, Dodd rallied his young companion. "Why the long face and cloudy looks, Mark?" he demanded. "We've saved the world from a disastrous war and given the emperor a barren empire. Surely, that is cause enough for rejoicing."

"I'm not so certain we would not have done better to defy the emperor and have the war," Mark answered slowly.

The secretary of state looked at him quickly. It was obvious that Mark Alden was not joking. "What do you mean?" he exclaimed. Long and intimate acquaintance with his young friend had given him a wholesome respect for the processes of his mind, the lightning-like intuitions of his brain.

"Hasn't it struck you as queer," Mark evaded, "that he asked for a few frozen miles at the north pole, as well as the vast area around the southern antipodes? Granted that his countrymen can render habitable the vastnesses of Antarctica, why his manifest desire for the paltry waste at the opposite end of the earth?"

Dodd was startled. "Why—why——" he stammered, and could go no further. In the tremendous anxiety to seal the bargain, no one of the assembled diplomats had thought of that angle. Yet now that it was mentioned, it was strange. Then he laughed. "It's the. general consensus of opinion that he has gone crazy," he declared.

But Mark, remembering that queer gleam of triumph in William's eyes when the last document was signed, was not so sure of it. Yet, since he had nothing definite to go on, he said no more. The matter dropped.

SIX MONTHS passed. The world relaxed; the troops were demobilized; the great battle planes stood moodily in their hangars. Civilization went about its proper business: the pursuit of happiness, of private wealth, of love. The emperor no longer rattled the scabbard; he was strangely meek and complacent. Mark Alden watched with wary eyes, but could see nothing wrong. In the evenings, he discussed the puzzling situation with his closest friend, but they could arrive at no solution.

This friend was Fred Kingsley, already, at thirty, the only scientist in the world to cope on an even basis with Dr. Paul Crusard, of the emperor's realm. He was a great geologist, a physicist of note, a delver into the puzzling realm of electromagnetic phenomena.

The two friends were wholly dissimilar in characteristics, and therefore all the closer bound to each other. Mark Alden was tall, inscrutable, his slight slouch concealing steel-strung muscles and tremendous strength, his veiled, sleepy eyes covering a razor-edged brain. He was the most valuable man in the secret service, but not even Fred Kingsley knew that his best friend was anything else but what he appeared, officially, to be.

Kingsley, on the other hand, was the complete scientist. Of medium height, energetic, absorbed in his studies, content to take the rest of the world at it's face value, he tried to laugh away Mark's hinted fears.

"It is possible, of course," he decided, "to make Antarctica semi-inhabitable. I know that Crusard has long been studying the terrain. He found some volcanic areas, whose heat might be tapped. There are doubtless veins of coal, strata of iron, under the eternal ice. But it would cost fabulous sums to colonize even to a degree, and the colonists would always live on the ragged edge of disaster. As for the North Polar Region, that is wholly incapable of sustaining the smallest colony."

Yet, to the vast astonishment of a skeptical world, the emperor proceeded with his plans. Great transports steamed toward the frozen seas, convoyed by formidable battleships. Surprised observers reported that they were laden to the brim with colonists—thousands of them; that freighters were packed high with cargoes of food, of lumber, of steel girders, with huge boxes that obviously held immense pieces of machinery.

They sailed in secrecy, and the piers bristled with guards. Planes hovered by night and by day over the steadily steaming flotilla, as if to cover them from even aerial observation. Yet Mark received reports. He studied them, frowned.

The colonists were men exclusively, and Dr. Paul Crusard had sailed with them. Mark wrinkled his brows, saw Dodd confidentially. Was the colonization but a mask for a surprise attack on the American coast? This was something that Elliot Dodd could envisage. Quiet orders issued. The American fleet sailed for maneuvers in coastal waters; the coast defenses were reenforced.

But the emperor's vast array surged ever south, far out on the Atlantic, steamed past South America, past Cape Horn, into the regions of eternal mist and drifting icebergs, into Ross Sea, and heaved anchor on the very verge of the ice wall that marked the boundary of the frozen continent.

Then the long night swallowed them up.

Another convoy followed, and another. The world rocked and buzzed. The emperor was going through with his insane plans. And to the north, a smaller fleet set sail. It headed toward Iceland, forced its tortuous way through ice-clogged passages into the Arctic Ocean, made landing in a fjord of northern Greenland, just within the granted territory. Then that, too, was heard from no more.

THE world buzzed, and mocked. The emperor, obviously quite mad, had embarked thousands of his best men, had scattered his war fleet to the veritable ends of the earth. He was no longer to be feared. Elliot Dodd thought so, too, and Fred Kingsley as well. But Mark began to wear a harried look. He could not fathom it quite, but he was under no illusions. The emperor was not mad. He was playing a deep game.

Then, early one morning, Mark Alden ushered a bluff, weather-beaten whaling captain into the presence of Elliot Dodd. At least, that was what the man seemed, with his sailor's jacket and jaunty cap, his thick boots and grizzled hair.

"This," he introduced, "is Earl Wesley, one of my cleverest operatives. Tell Mr. Dodd your story."

Wesley spoke with clipped words. "It's nothing much. Pursuant to Mr. Alden's instructions, I took a plane to Buenos Aires and chartered a ship for a whaling cruise. I had no difficulty in picking up a crew; the port's full of sailors on their uppers. It was all very legitimate. Then we sailed south, around Cape Horn, whaling. We even caught two big fellows, cut them up, tried out and barreled the oil.

"Then we coasted the continental barrier, sailing toward the west. I kept a sharp lookout. Several times we narrowly missed the emperor's patrolling warships. Twice I heard the roar of overhead planes. But they didn't see us in the ice fog. Then we entered Ross Sea. We hid by day in ice-clogged channels, slipped along by night. I was following your instructions, Mr. Alden, to the letter.

"On the last day I started out before dawn. As the sun glinted over the towering ice pack, I steamed boldly into Little America, where Byrd had made his base years ago. I carried the Argentinian flag at my mast."

He hesitated, and something in the man's air snapped Dodd to keen attention. "Well?" he demanded. "What next?"

"I wouldn't have believed it," replied the operative slowly, "if I hadn't seen it with my own eyes. There, cut out of the ice wall, was a real city—with piers and great warehouses and unloading cranes and ships at anchor. New York Harbor itself couldn't have been busier. Fur-clad men heaved and shouted as they took off cargoes. Half a mile inland, there was an airport, cut smooth as a ballroom floor in the solid ice. Even while I watched through my telescope, I saw great cargo planes take off, head inland over the wild ranges, others come roaring in to land."

He grunted, scowled apologetically. "That was all I had a chance to see. Half a dozen destroyers came scooting from anchor at the sight of me. They hove me to with a shot that almost took away my bowsprit. They meant business, those babies. And they laid down a smoke screen that completely cut off any further view of the port."

"Go on," Mark urged as Wesley stopped again.

Wesley grinned painfully. "I thought sure I was a goner. For they were mad—and I mean mad! It was touch and go whether they shot my whole crew out of hand. 'We were spies,' they told me, 'and they had a very efficient method for handling spies.' I played dumb; my crew didn't have to play at it. I was a Svenska seadog, I told them. Luckily, I could speak the language. I had been blown off my course; my compass had been broken—I did that just before they boarded me—and I didn't even know where I was. Then I showed them my barrels of oil, the smelly remains of the last whale.

"It was a toss-up. A kid captain of one of the destroyers took pity finally, decided the issue. Two warships escorted me all the way to Tierra del Fuego, with hideous threats as to what would happen if I ever again poked my nose into Antarctic waters."

Mark turned somberly to Dodd. "That's the story, Elliot. And I had another operative try as a sealer through Baffin Bay in the north toward Etah. He never got there. Just out of Canadian waters a pocket cruiser chased him back with a couple of very business-like shells. And they weren't blanks, either. Now what do you think of the set-up?"

For a moment a shadow flitted over the official's face. Then he smiled. "Nothing at all, Mark," he retorted.

"Those are just examples of the emperor's pleasant little ways. He never did like to be snooped on. I can see no reason for alarm."

BUT Mark Alden could, and did. And, being a man of energy, he decided to do something about it—unofficially, of course. He asked for an indefinite leave of absence.

Dodd looked at him queerly. "Don't try anything foolish," he warned with sudden anxiety. He thought very highly of Mark. But Mark avowed very gravely that he intended nothing foolish—after all, the word had controversial meanings—that it was simply a vacation he was taking. So that perforce, albeit reluctantly, Dodd granted the request.

Mark's next steps were swift and decisive. He held a lengthy conference with his friend, Fred Kingsley. He hated to do this, but he wasn't sufficient of a scientist for what lay ahead. Kingsley was essential, even though the chances of coming back alive were exceedingly slim. But Kingsley, after the first skeptical explosion, fell in with a readiness that caused Mark considerable qualms of conscience. Mark was used to desperate emprise and the air of danger; but the soft-lapped, unwarlike scientist——

They set out from Washington, secretly, at dawn, in a trimotored, high-speed pursuit plane, with a guaranteed flying radius of ten thousand miles. In the cockpit was a miscellaneous cargo: certain delicate scientific instruments, a heavy cache of food, warm furs for subarctic temperatures, skis for ice traveling, rifles, automatics—and a number of atomite bombs, each of which could have pulverized the Empire State Building to impalpable dust.

They flew south. "The real heart of the mystery lies in Antarctica," Mark decided. "The North Pole Station is the subsidiary one." And Fred, thinking of Dr. Paul Crusard, agreed.

They reached Rio de Janeiro without adventure. Once, from the ten-thousand-foot level, they saw far beneath, on the broad flanks of the Atlantic, a convoy steaming slowly south—more men, more equipment, sent by the emperor to his mysterious Antarctic colony.

At Rio they refueled, again sped southward along the coast. A landing at Buenos Aires, then on to Gallegos, port of last resort at the tip of savage Patagonia.

Here they aroused some unwanted curiosity, but they were just two American adventurers, with pseudonymous passports, who hinted of prospecting for gold on Tierra del Fuego. The mixed population of the frontier outpost shrugged collective shoulders, sold them gasoline at outrageous prices, and went back to their foggy existence.

Then south again, this time at fifteen thousand feet altitude, with a muffler on the propeller, to dampen the roar. It was essential that the emperor's scout boats should not know of their presence near the prohibited territory.

Huge icebergs drifted like ghostly toys far beneath; fog and snow and screaming gales took them in the bit and tossed them a hundred miles off course; bleak, skeleton islands appeared in dazzling sunshine and disappeared in driving snow. Then, straight ahead, like a knife-edge cutting the gray, turbulent sea, Antarctica reared itself—a huge wall of winding ice, tossing itself ever southward in tier on tier of frozen mountain ranges.

Mark was piloting. Fred Kingsley knew nothing of planes. They wore their furs now, and the cabin was electrically heated. Outside, the temperature was fifty below, on the Fahrenheit scale. It was a glorious sight, that contorted upthrust of fathomless ice, gleaming with mysterious fires, under the slanting rays of the broad, red sun. But to Mark, crouched over his controls, the wild beauty held a sinister mystery. The feeling had grown on him, had become an obsession, that the fate of the world was being forged within the fastnesses of the ice continent; that on his—and Kingsley's—shoulders rested the intolerable burden of averting that fate.

HIS plan of campaign, up to a certain point, was mapped. He did not head for Ross Sea. Instead, he cut over the ridged Graham Islands, swung high along Wendell Sea, and zoomed across Hearst Land and the grim mountain range that made a jumbled escarpment of the interior. He intended coming around on the emperor's base in Little America by the back door. After that——He shrugged his shoulders.

They would have to trust to his nimbleness of resource and Fred's scientific knowledge.

He made a wide detour. No human eye had even seen this part of the interior. They lunged over unmapped mountain ranges, whose saw-tooth pinnacles meant instant death if their motors stalled for a moment; they leaped over fathomless gorges whose depths penetrated the hard, iron skeleton of the continent; they tossed and groaned in every strut at sudden blasts of icy air. Fred watched at the telescope.

In all that wide waste there was no sign of human being or human handiwork. So far they were safe. The low sun skirted the horizon. An eerie twilight fell on the land.

"How far are we inland?" Mark queried.

Fred Kingsley made hasty calculations. "About two hundred miles," he reported.

"Safe enough from casual planes," Mark decided. "We'll level off due west. Ross Sea is about eight hundred miles from here; we can make it in less than three hours."

Obediently, the plane swung to the stick. The sky was ablaze now—a shimmering, frozen dance of color and torment.

Fred sucked his breath sharply. "The southern lights!" he exclaimed. "The Aurora Australis, counterpart of the Aurora Borealis. I've never seen them so magnificent."

But Mark had no eye for their wild beauty. His eyes narrowed with thought; his mouth was grim and hard. "Tell me, Fred," he cut across his companion's admiration with brutal abruptness, "hasn't the aurora something to do with sun spots?"

Kingsley looked surprised. "There is a connection," he admitted, "though the exact tie-up is still vague. All we know is that the sun spots are vast pools of electrical disturbance, that the auroras are also electrical phenomena, and that they ebb and flow together in an approximate cycle of eleven years."

Mark seemed to have difficulty with his utterance. "And when is the next period of maximum disturbance?" he asked.

Fred thought a moment, then vented an exclamation. "Why, it's just about now! End of spring, summer of 1956. I remember, too, there were predictions that the sun-spot area would be of unprecedented proportions this cycle. No wonder the aurora is so blinding. But why do you ask?"

Mark bent over his controls, said nothing. Slowly, a startling thought was shaping in his mind——

AN hour later, Kingsley exclaimed again. His eye had been constantly glued to the telescope, was sweeping the frozen wastes beneath.

"Look! Over there!"

They peered through the dancing, steel-hard colors. A plane was winging far to the west, pointing south, directly toward the pole. Seconds later the roar of its unmuffled propeller throbbed faintly in their ears. Then the glinting rainbow tints swallowed it up.

Mark's brow went black as a thundercloud. He ground out an oath, swung his stick hard. Like a willing race horse, the plane caromed sharply, fled southwest in pursuit of the stranger.

"For Heaven's sake, Mark," Kingsley yelled, "are you mad? That way is the pole—and destruction. Our way is Ross Sea, just in back of Little America. Heaven knows we've discussed what we were going to do often enough."

"Plans are changed," Mark said through his teeth. "We're following that plane."

"Whereto?"

"To the south pole!"

He vouchsafed no further information, and Fred Kingsley asked for none. He had learned to trust implicitly in the swiftness of Mark's intuitions. For several hours they followed the invisible trail. The southern lights faded into a dull, drab twilight that shaded the unknown continent in mysterious gloom. They flew high and with the muffler dampened. But the trail resounded in their delicate amplifiers, and they held to it like a bloodhound on the scent. Their quarry had no reason to cut the roar of its propellers, to sense the pursuit.

A frozen moon swung in a narrow arc, flooded a landscape as strange as that of its own lifeless surface. Once they caught another sound in their amplifiers—another plane heading north—heading toward Ross Sea from the south pole! They skimmed perilously close to a fantastic mountain range to avoid being seen, looked at each other with bloodless faces.

Then, suddenly, in the waning light of the moon, from an altitude of twelve thousand feet, within the ramparts of ice-barbed mountains, an incredible scene burst upon the startled pair. So suddenly that Mark, in his astonishment, almost lost control of the plane.

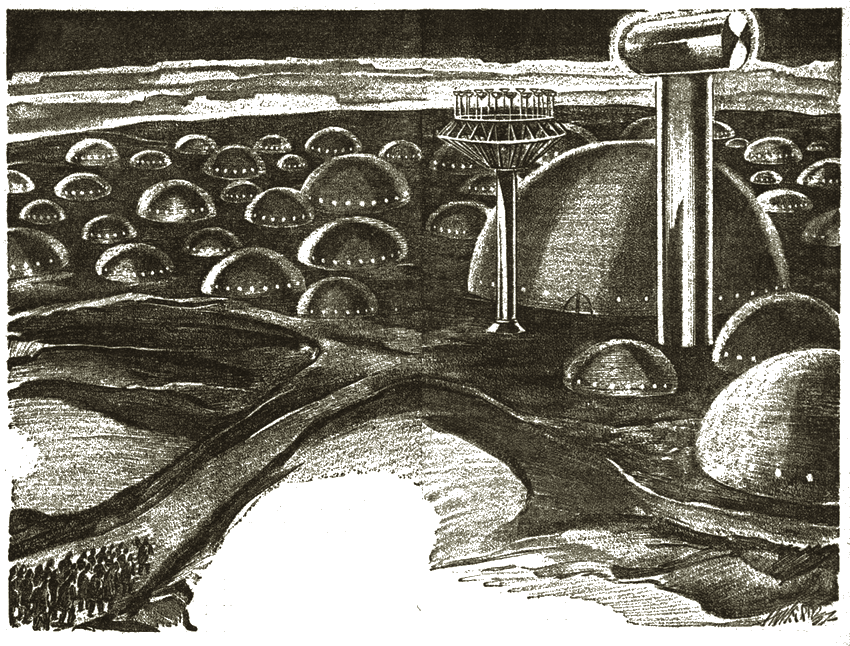

Far ahead a plateau loomed. Its surface was dark and bare. Around it, in an enringing circle, stretched the interminable white of crevassed ice. But the gaunt uplift of land, naked, for the first time in all history, to the revealing moon, was a festoon of twinkling lights. Lights that were stationary and lights that darted to and fro with exceeding swiftness.

The desolation seemed to swarm with life and activity. Through their powerful glasses they could pick out a veritable city of beehive huts, of larger buildings. The faint clank of machinery vibrated through the amplifiers. Red flames blasted into the night, died down again. The air shook with sullen roars, as of subterranean blasting.

"They've done it," Kingsley's voice was cracked with excitement. "I did not believe it possible. They've blasted off the ice and snow and reached hard ground. They've discovered the coal and iron veins that Scott and Byrd reported, have built smelters and furnaces. They are recreating a civilization—industrially as advanced as Pittsburgh or Essen—at the very apex of the world. This is Crusard's doing."

But Mark was not listening. His face was pale and grim. "Quick," he rasped, "sight your instruments and get me the exact location of that plateau. Every second's delay is dangerous. If they should discover us——"

Kingsley worked with feverish haste. Then he lifted his head, and there was a strange look in his eyes.

"That colony," he answered slowly, "is at Longitude O, Latitude 90. It has been constructed directly at the south pole!"

MARK made a precarious landing between two scowling hummocks of ice about ten miles from the polar colony.

He had jockeyed for half an hour trying to find just such a spot, off the direct line to Ross Sea, and well-hidden from observation. So skillful was he that the uneven, steel-hard snow crumpled their landing gear only slightly. No other damage. The plane could take off again if need be. And they had not been seen!

They worked now with feverish rapidity. All was again according to plan. Great furs lapped their bodies against the intense cold; huge parkas almost covered their faces. Their beards had already grown to an unshaved stubble. Mark roared with laughter when he looked at Kingsley; the scientist grinned back at him. Not even their closest friends could have penetrated the disguise. They were, by all outward appearances, subjects of the emperor.

They hauled the plane into a little gully, powdered it over with snow so that it would not be visible from above, strapped on skis, secreted in their voluminous furs a small supply of food—and automatics. The rest, perforce, must be left behind, including the deadly cargo of bombs. If, after their spying, they could win back to the plane with the knowledge they had achieved——

They clasped hands a moment, then strode clumsily over the rugged terrain without another word.

It was difficult, tedious work struggling over the fissured ice and snow. Octane thermometers strapped to their furs recorded sixty-two below zero. Their breath froze into powdered icicles as it left their lips. It was too cold even to speak. But they forged steadily ahead, toward the mysterious city which had been located directly at the pole.

No one saw them approach over the desolate wastes; no one suspected that human beings were plodding through the semi-twilight. The noise and clank of heavy machinery, the bustle of ceaseless industry, grew louder as they neared. Directly ahead, the ice-free plateau reared itself above the savage, encircling wilderness, ablaze with argon lamps which turned night into busy day.

Mark stumbled, disappeared with a strangled cry. One moment he had been fifty feet from the rim which had marked the dividing line between earth and ice; the next, the prehistoric glacier beneath his feet had seemed to vanish in a blast of rushing, particle-filled wind, and he had fallen into nothingness.

THERE was a crash, a roaring sound. His thrashing body collided with solid ground; his teeth rattled like castanets; his bones groaned with the terrific impact.

He sat up with a little moan, to see Kingsley sprawled at his side, lifting his head with an expression of stunned surprise.

"What—what happened?" the scientist gasped.

The fog cleared from Mark's brain. He stared, gulped unbelievingly. They lay on uncovered earth—earth that had been hidden by an eternal blanket since the world began—earth frozen to steel-hardness, yet which, even as they heaved themselves unsteadily erect, was already softening into the dry, fertile loam of a Kansas prairie.

They were bruised and badly shaken, but otherwise unhurt. The thick furs had padded the twenty-foot drop. But Mark was worse shaken in his mind. For, in back of them, the way they had come on painful skis, there was already two hundred feet of similarly uncovered ground. And, even as they watched, wondering if they were mad, the area was increasing. Something invisible was biting huge, remorseless chunks out of the wall of snow and ice, swirling it through a haze of dancing particles into nothingness, and passing on with gigantic strides.

For a dazed thirty seconds they stood, staring. In that short space of time Antarctica had ebbed away from them to a distance of half a mile. Something trickled down Mark's face. Mechanically, he brushed at it with fur-mittened hand. The trickle became a flood. It was perspiration! In even greater bewilderment he glared at the octane recorder on his wrist. The colored fluid was surging upward, reaching an incredible figure. It read sixty-four degrees above zero; whereas only a minute before it had hung lifeless at sixty-two below.

Kingsley was already shedding his heavy furs with feverish haste. Mark hastened to follow suit. He was stifling. In seconds the swathing garments made dripping huddles on the bare earth, and the two men, stripped to the drab, gray working clothes of the emperor's subjects, which they had worn underneath, mopped perspiring brows. Already a new landscape enveloped them as far as they could see—a terrain of brown, luxuriant soil. Far to the rear a saw-toothed mountain range still raised its ice-glistening pinnacles in defiant majesty.

Amazement, comprehension, struggled on Kingsley's face. "This is Crusard's doing." His voice was a cracked whisper. "He has harnessed incredible forces, put them to work. He has——"

Mark Alden's hand darted out, pulled the scientist violently into a little gully. "Down, if you value your life!" he said harshly.

They flung themselves to the ground just in time. From the direction of the polar city monstrous machines were lumbering straight toward them with thundering sound—gigantic tanks, lurching along on caterpillar treads. From their forward poops huge, funnel-like structures swung back and forth in wide arcs. From the openings a blue radiance crackled and streamed, paled to invisibility a hundred yards in front. A fleet of giants, radiating from the mysterious city like spokes of a wheel, advancing with great strides over the territory newly wrested from the long dominion of the polar blasts, hurtling on to newer and mightier conquests.

The two men flattened themselves in their scanty hiding place, barely breathed as the tanks moved on. One of the metal monsters passed them by, a scant few yards away, its blue swath slicing bare inches from their unprotected bodies. Then it was past them, vanishing with diminishing roar on its triumphant march to the distant boundaries of Antarctica.

THE shadow of remembered death was in their eyes as they arose. But the shadow gave way to a scientific glare in Kingsley's countenance. His voice was rapt, almost devout with awe. "Those were high-tension electromagnetic fields," he said. "I've never seen their like before. They must have a potential of at least a hundred million volts. They've created such tremendous fields of force that the molecules of ice and snow upon which they were trained became polarized into innumerable tiny, north-and-south-pointing magnets. The molecular adhesions which held them bound together were violently disrupted, and the solid ice sublimated at once into gaseous, molecular ice. The liquid water stage was eliminated entirely.

"With machines like that. Crusard will be able to clear the whole vast continent of Antarctica of its overlaid ice pack within days, and without the fear of whelming floods of water. It's stupendous! But where did he get the power?"

Mark said softly, though his face was bleak, "I think I know the answer to that one. But don't ask me now. Wait!"

Far to the north, in the direction in which the funnel-swinging tanks had disappeared, came a dull, booming sound. Through the eerie twilight, their startled eyes saw a descending rain of burning, smoking embers. Then there was silence again over the wastes.

"Good Heavens, what was that?" Kingsley stammered.

"That," replied Mark even more softly than before, "was our plane. The electromagnetic beams exploded our atomite bombs. I think one of the tanks went up with it."

They stared at each other. All their plans had been as suddenly blasted as their plane. They were two solitary men, stranded on the vast Antarctic continent, alone in the heart of a mysterious, alien territory, without means of retreat, without possibility of escape, yielded up to the tender mercies of the emperor's men. They had nothing more than their clothes, small packets of food, and puny automatics. Before them, around them, for thousands of miles, stretched danger, mystery, and a ruthless enemy armed with new and incredible weapons.

Kingsley shivered a bit. It was getting cold again. The temperature was dropping steadily. Without a word he picked up his discarded furs, donned them carefully, meticulously. Mark did the same, watching his companion with a grim, yet affectionate smile. He had made no mistake in picking Fred Kingsley as his companion on this desperate adventure. The easy-going scientist was pure steel beneath.

"What do we do now?" Kingsley asked.

"Do?" echoed Mark. "We go to the city."

"Forward, then."

The twilight deepened into night as they plodded on—the night of the pole, six long, weary months of unrelieved darkness, of bitter blasts. But already the Aurora Australis had unfurled its banners again. The sky, the earth, even the great humming city that loomed ahead, were rivers of dancing fires, of sheeted colors that ebbed and flowed and crackled with supernal splendors. They had never seen such an aurora before. It was appalling in its magnificent glory. Kingsley wrinkled his forehead. He was beginning to put two and two together. But he said nothing, and Mark, glowing in the radiant bath as in a witches' brew, was blank of all expression.

THEY proceeded warily as the city neared. It reared itself on a long, sloping elevation to a height of some hundred feet. The tanks had disappeared on their mighty errand. They could see figures moving about, silhouetted against the argon beams, iridescent with the flicker of the southern lights.

The figures were dressed as themselves, in great, shapeless furs, surmounted by peaked parkas. It was again sixty below; within hours it would fall to seventy and even eighty. Mark had been as meticulous in his choice of garments as in his disguise.

Straight ahead, a gang was marching, clumsy in furs, obedient to the barked orders of their leader. A shift, either on the way to work, or retiring to their bunks. The two men crouched behind a little ridge, waiting for them to pass. The light was confusing, playing fantastic tricks on the eyes. But this was an unexpected break for the intruders.

As the column swung along, over the already rehardened ground, Mark whispered quickly, "Now's our chance!"

They arose quietly, slipped even more quietly in the rear, unobtrusively melted into the last straggling ranks. All the men's heads were bent, shielding faces against the bitter air, while the hoar frost of their breaths made white smoke around. So that no one saw them join, or thought anything amiss in these two figures, clad like themselves.

No one spoke; the cold was a physical impact on the opened mouth. Only the leader grunted brief commands through half-closed lips. They swung sharply, plodded toward the very center of the city, toward a curious dome-like mound of gray, light-quenching substance.

"Asbestos," Mark decided. "The perfect insulator against heat and cold." His eyes moved warily about, trying to comprehend the fantastic scene. All about were similar mounds, though of lesser size. Within them, no doubt, and burrowing underground, the colonists lived, guarded against polar blasts, and heated by understandable scientific means. A city of gigantic beehives!

Within those perfectly insulated mounds, and burrowing

underground, the colonists lived, guarded against polar blasts,

and heated by scientific means. A city of gigantic beehives!

There were others, too, larger in size, from which the dull vibration of machinery emanated. But none approached, in tremendous area, the central dome. And none had flanking it the two tall towers of dissimilar shape that guarded that great central dome. Mark cast stealthy glances at them. They were awe-inspiring, incredible in their structure.

The one on the left was of shining metal, some two hundred feet in height. It mushroomed out at the top into a complex grid of heavy steel, crisscrossing bars, from each of which sprouted a veritable forest of horizontal, cup-shaped rotors, spinning on tall, ball-bearing stalks of steel. There seemed no machinery to make them spin, no wind to shift their massive weights; yet round and round they went at incredible speed.

"There," grunted Kingsley suddenly, "is the answer—the source of the tremendous electromagnetic fields. Crusard has tapped the hurtling energy of the solar disturbances, of which the southern lights are themselves but a manifestation." Then he frowned. "But why directly at the south pole?" he queried himself. "Surely Crusard knew what every schoolboy knows—that his field-tapping rotors would have absorbed even more power at the magnetic pole, the true focus of the sun's streams of free electrons.

"And," he kept on whispering to his companion as they trudged steadily along, "even granting the freeing of Antarctica from snow and ice, he could not possibly affect the temperatures permanently, even with all the power in the world, so as to render the continent inhabitable."

The strain on Mark's face deepened. "Crusard is no fool," he answered quietly. "The very objections you raise, and of which there is no doubt he is well aware, point to a deeper and more sinister meaning in the choice of the geographical south pole as against the magnetic. Fred, this is no mere colonization scheme; this is a plot that involves incredible consequences to the world."

"But how?" Kingsley asked, still bewildered.

Mark did not answer directly. He lifted his eyes to the second tower. "What do you make of that other structure?" he demanded.

It was a tall steel shaft, almost five hundred feet in height, some fifty feet in diameter, its exterior smooth and blank. But at the very top a horizontal shaft of similar diameter was laid across, for all the world like a right-angled T square. Its length was about one hundred feet in all. Kingsley shook his head. "I don't know," he confessed. "It might be anything; it all depends on what it houses in its interior."

"Looks to me like a handlebar," Mark muttered, "a grip for some supergiant."

"No talking, you men," shouted the leader suddenly. "Save your breath for your work. You'll need it."

The two Americans bent their heads lower, moved on in silence. Fortunately, they spoke the emperor's language with native facility.

THE central dome loomed gigantic before them. A door swung wide; they tramped through, and it closed instantly behind them. The interior was a complex of mighty machinery. Overhead was a web of transmission cables, thick as a man's body. Dynamos, tall as buildings, hummed with energy.

The curving walls were paneled tubes, lambent with racing blue flames, sizzling with electric bolts of incredible voltage. Sluicing from these were storage batteries of novel design, huger than any even Kingsley had ever seen. Great bar magnets, coiled around with fine steel wires, swung overhead on frictionless pivots, weaved a swift, yet ordered dance in relation to each other, to achieve maximum power. Every instrument, every engine, that man had yet invented, and many that Crusard and his associates had devised in the strict secrecy of the emperor's laboratories, were compact in the vast interior.

But mightier than all else, twin machines that dwarfed even the fifty-foot dynamos, were the two shining balls that poised on groaning gimbals in the very center of the dome—two metal globes, shimmering with an iridescence that bespoke ceaseless, incredible power within, each one hundred and fifty feet in diameter.

Kingsley almost betrayed himself with his sudden start, his stifled exclamation. His nearest neighbor turned suspiciously, his dark face malign. Mark pressed close to his friend, dug him surreptitiously in the ribs, bent to unlace his fur boots. They were all doing that. It was warm inside, and the men were rapidly divesting themselves of polar garments, arranging them neatly on labeled hooks.

The scientist recovered himself, bent swiftly also. But thoughts buzzed round and round in his head. Those were electrostatic machines, of a size and capacity that made mere toys of the famous De Graaf affairs in America. His brain spun as he tried to calculate the total power of the pair; it seemed impossible to fill them all with sufficient energy. Yet obviously, from the lambent sparkling on their surfaces, from his quick glance at the recording dials, they were close to saturation. The great cables that snaked around the interior, plunging through orifices downward into the bowels of the earth, lifting outward through the heavy asbestos walls, gave him an inkling as to the sources of that mighty store of energy.

He had seen the outside rotors, the ingenious devices for tapping the shimmering dance of the aurora, the flow of electromagnetism that emanated from the sun itself. But what came up from the depths of the earth? Could it be——

Of course! He saw it all now.

Crusard, in that earlier survey of the polar regions, years before, had incautiously avowed to the scientific world that he had found subterranean volcanoes on the continent. The earth's own magnetism, the mighty sun's electron streams, the surge of boiling lava—here was power beyond all human conceptions.

To what purpose? Still the frozen blasts would render the continent valueless for human habitation. And why not at the magnetic pole, the logical site? Why the colony at the limited north pole? Why the second tower with its horizontal crossbar that Mark had likened to a handle for some giant? Why? Why? Why?

Questions that Mark had said must be answered to save the earth from a doom beyond all imagining. The questions rolled and reverberated in Kingsley's mind, and found no answer. As in a dream, he took off his furs, followed mechanical suit with the others, hung them on the nearest hook.

A BURLY figure, furs limp on brawny arm, rumbled a guttural oath at him. "Dumbhead!" he snarled. "That's my hook. Take your filthy stuff off you——" His eyes narrowed. "Say!" he roared, so loudly that the group stopped their undressing, brought the leader up on the run. "Who are you? You ain't in our shift?"

Mark stiffened, edged surreptitiously away.

A panic swept over Kingsley. He had betrayed himself. And Mark Alden, his friend, the man who had brought him into this peril, was obviously abandoning him. Then he steadied. Mark was right. More than mere friendship depended on this. The fate of the world was involved. If Mark, in the resulting confusion, could hide——

He essayed indignation, mumbled the guttural tongue to spluttering incoherence. "Stupid ass!" he hissed. "Of course I'm not; my leader told me to report to this shift. Shut your big mouth!"

But the sergeant was already upon him. exploding in a torrent of questions.

"Here, you, what's all the row about?"

The burly one said, submissively, "This here fellow tried to take my hook. He ain't from our shift."

The sergeant was short and pompous. He turned on Kingsley. "Who are you? What's your name?"

"Frederick Storm."

"Your former shift?"

Blindly, the scientist plunged. "No. 10."

"Your sergeant's name?"

Kingsley fumbled with the button of his packet. He was caught, trapped. If he could only get to the automatic in the inside pocket in time. Mark Alden had vanished quietly into the wilderness of machines.

"Hurry up," snapped the sergeant.

"I don't remember."

"Oh, you don't, eh?" Like a flash, a heavy revolver was covering the American. "Grab him, men. We'll find out fast enough who he is."

Despair settled on the scientist. They sprang upon him with a will; rough hands pawed over his clothes. The automatic came out, the packet of food.

"So!" said the sergeant malignantly. He examined the weapon. It was of American workmanship. "So!" he repeated with a certain vicious satisfaction. "A spy, ha! Dr. Crusard will be most interested."

"IN what, pray, will I be interested?" a cold voice asked.

The men fell away, groveled. The sergeant, a moment before so pompous, authoritative, deflated like a pricked balloon. Dr. Paul Crusard was the emperor's right arm, his visible representative in Antarctica. "We just caught a spy, excellency," the sergeant stammered.

"So!" remarked Crusard. turning critical glance on Kingsley. The latter said nothing. He had met Crusard at various scientific conventions in the old days; they had even collaborated on a bit of research. But he trusted in the security of his disguise.

Crusard was tall and angular. His face was a thin, bearded mask; his forehead was a glistening expanse of intellectuality. But his eyes were glacial and merciless.

"So!" he repeated. "This alleged spy says nothing. Very, very wise—not like the usual run who play that fascinating game."

He walked slowly up to the American, a slight smile on his face, as if inwardly amused. He spoke conversationally. "You must know', my dear fellow, that we've been expecting you."

Still Kingsley did not move a muscle of his face. He stood quietly, unafraid, now that disaster was already upon him.

"Yes, we lost a valuable ice-sublimation tank as a result of the explosion of your plane. You no doubt had atomite bombs on board. You intended, my friend, to bomb our poor little project out of existence. A most laudable ambition—from your point of view."

He reached up suddenly, pulled hard at the beard which the American had grown. The action was so unexpected, the pain so intense, that Kingsley involuntarily cried out—in round American curse words.

The first shade of disappointment on Crusard's face at the naturalness of the beard gave way to a broad smile. But his eyes were cold, merciless probes.

"That good, vigorous American voice! The one thing you couldn't disguise. Now, in truth, I may call you my friend—my esteemed colleague, in fact. Welcome to the new realm of our glorious emperor—Mr. Frederick Kingsley!" The American met his sarcastic glance with candid defiance. Mark Alden at least was still at large, overlooked in the focused attention on himself. "A rather pretty welcome, Crusard! You forget that our nations are at peace."

The tall scientist arched his eyebrows. "Peace?" he murmured. "There is no peace in nature. Everything is at war. And you forget, my friend, that you have come to spy. Even in so-called peace, there are certain penalties that relate to a spy."

Kingsley disregarded his veiled mockery. He came straight to the point. "You have done incredible things in this new land," he said. "They honor you as a scientist. Do they do equal honor to you as a man?"

Icy fire flashed in the gray eyes. Crusard clicked his heels. "In the service of the emperor all is honorable." Then he unbent, smiled. "What, in fact, do you know?"

"Enough to realize that what you intend bodes some harm to the rest of the world," Kingsley shot back.

"A very sensible deduction," Crusard approved. His eyes narrowed with cynical amusement. "But the exact means?"

"That was what I had come here to find out," was the bold reply.

"You shall," Crusard decided unexpectedly. "It will be a pleasure to disclose my dearest life work to the only other man in the world who can truly grasp its full meaning and majesty. In fact, you shall be a spectator to the mightiest engineering feat in all the universe. You alone of all the outer nations will have that honor."

Kingsley knew very well what Crusard meant by his invitation. But no sign of that inner knowledge appeared on his face. With equally polite mockery he demanded, "When will the unveiling of your masterpiece commence?"

"Within a week! By that time the continent will have been cleared of all its ice. Already the emperor is winging south with a huge fleet of battle planes; already the seas are dark with the ships and convoys of our nation, transporting a million select colonists, with all supplies, to the new land. When they arrive, and are safe in port, we shall begin."

Veiled words, through which a horrible premonition came to Kingsley. "Don't you fear disaster to the rest of your people—those who have been left behind?" he asked steadily.

"Our country is mountainous," Crusard answered cryptically, "and our people have received their orders. When all subsides, they will be transported here as well. And now, my dear colleague," he continued, "you must be confined until all is in readiness. Farewell!"

FOR a week Kingsley paced his tiny cell in the bowels of the earth, seeing only the speechless guard who thrust his food through the bars, hearing only the dull echo of his steps, the buzzing round of his thoughts.

Crusard had played with him as a cat with a mouse. He had told him nothing, had hinted of dreadful things. Try as hard as he would, Kingsley could not fathom what portended, what dreadful fate was about to overtake the world. He ground his teeth in helpless anger. He was immured like a beast, his own life forfeit.

But Mark was free! He clung to that desperately for a few days; then that faint hope also vanished. If Mark were still alive, he would somehow have managed to get word to him in his cell.

The days passed. The solid rock quivered and groaned with the increased beat of subterranean travails; the guard's dour countenance grew more and more exultant.

Then, on the seventh day, came a mighty burst of sound that penetrated even his fastness—a roar of human voices.

The emperor had arrived!

On the eighth day two guards came, instead of one. They unlocked the steel door. With pistols they prodded Kingsley along the steep passageways, back to the central dome.

It was transformed. The banners of the emperor festooned the rounded arch, fluttered from all the girders. A great dais had been erected at one end. It was crowded with officials, preened like pompous parakeets in lace and ribbons. But they paled to drab insignificance compared to the grossly fat, stubby individual who reared on a solitary chair of state above them all. Diamonds, rubies, lustrous pearls, emeralds, star sapphires, iridescent opals weighted his uniform to a dazzling splendor. Yet they only accentuated the coarseness of his quivering jowls, the sordid cunning of his shifty eyes. The emperor!

Directly in front, before Kingsley's blinking eyes, was a gigantic televisor screen, gray with quiescence. He darted a swift glance at the recording dials. The giant orbs were saturated with mighty power; every superstorage battery brimmed with leashed energy. All was in readiness.

PAUL CRUSARD, bleak and intellectual as ever, seemed the least strained of all the multitude. He welcomed his captive with an ironic bow, waved him to a seat in front of the televisor. But the guards, pistols drawn, flanked him alertly. "Be seated, my friend," he remarked. "As a scientist you will thrill to what you are about to witness."

"And as a man, and an American?" Kingsley countered.

Crusard shrugged his angular shoulders mockingly, moved to the panel board with its wilderness of switches and snaking cables.

He turned to the emperor, made humble obeisance. "Before I begin, excellency, it is my intention to explain in detail the procedure, the methods I employ."

An annoyed look passed over the gross face, wiped away. After all, even the emperor could not afford to slight Dr. Paul Crusard, the engine of his anticipated triumph.

"Very well, doctor," he said ungraciously, "but be brief."

Crusard bit his thin lips. "I shall." he replied. "Three years ago, at your gracious behest, I began my experiments, investigated this vast territory of Antarctica. Our nation, superior in talents, in energy, in racial purity to all the world, was yet hemmed in a paltry several hundred thousand square miles of unfertile soil, of arid mountains, by the envious nations of the earth. We were dependent for coal, for iron, for the very food we ate, upon the sneering will of inferior races. This was not to be borne; our fertile people knocked at our frontiers in vain.

"Here, on the continent of Antarctica, however, was a vast, uninhabited territory, of almost four million square miles.

I found unlimited coal, unlimited iron, great reservoirs of oil beneath the frozen surface. By a trick worthy of the mighty intellect of our noble emperor, the nations, all unsuspecting, gave us title to this regal realm.

"Already, with the use of superelectromagnetic beams, I have sublimated the ice cap to molecular, gaseous condition. Even now these ice molecules, drifting over the tropics, have precipitated into heavy rains and torrential storms, puzzling the stupid scientists of the world. For this is normally the dry season.

"The uncovered soil of our new continent is incredibly fertile. For a million, million years it has lain fallow, while the accumulated debris, the filtering dust and life germs of the glaciers, have dripped down to seemingly eternal rest. Our fifty million people can double, nay treble, and still have further room for expansion."

The emperor shifted impatiently in his seat. "Come to the point, Dr. Crusard," he snapped.

A slow brick-red mantled the sallow forehead of the scientist. This should have been his supreme moment, and the emperor was deliberately putting him into his subordinate place. Yet he bowed humbly and proceeded.

"But the greatest of all problems remained. Hardy as we are, we could not hope to reach the fruition to which we are entitled in a region where, for ten months of the year, the thermometer hovers at seventy to eighty below zero, Fahrenheit. We must, therefore, make for our new land a warm and smiling climate, where all the grains, all the fruits, all the vegetables, even those of tropic climes, may grow with unexampled, lush fertility."

He paused, waved his bony arm around the great rotunda. "I have solved that problem! More, in the doing, I have solved others as well. No longer will the other nations of the world constitute a threat to our supremacy by reason of brute numbers, brute resources. They shall vanish from the earth, like the mastodon and the dinosaur, whose bodies were mighty but whose brains were too dull for the struggle for existence; or, if some remnants remain, they shall be too weak, too exhausted, too preoccupied with the ceaseless battle against inimical elements, to be anything else but our subjects, our lowly slaves."

A HOWL of cheers rocked the girdered dome. On every face was gloating, the lust for domination. Kingsley felt suddenly sick at heart. He was beginning to understand, to piece the dreadful picture entire.

"We shall," Crusard went on dramatically, "reverse the earth itself upon its axis, make that area equator which is now the poles, make that region polar which is now the tropics." He smiled cunningly. "But the twisting of the globe shall not be complete. We shall stop short of a full half turn. In other words, Antarctica, our future home, shall lie partly in the temperate and partly in the tropical zones, a garden flowering under the benign rays of the sun, while the northern hemisphere, the regions of our rivals, our despicable enemies, will revert to the ice age, and be buried under huge, remorseless glaciers."

Now the storm of wild cheers burst all bounds. Glutted hate, satisfied vengeance was marked on every countenance. Kingsley jerked from his chair, was thrust down with backhanded sweeps, by his vigilant guards. Lord! What manner of beasts were these, what manner of twisted brain was Crusard's, to conceive such an awful fate for billions of innocent human beings! Now, for the first time, he knew why the geographic poles had been chosen for the seat of the world-twisting experiment, instead of the magnetic poles.

There was a self-satisfied air on Crusard's countenance as he droned on. "To perform this operation, I have harnessed the mighty electrical forces of the sun, of the earth's own vast store of magnetic energy, of the volcanic surge of subterranean lava. I have built them up, leashed these tremendous phenomena in apparatus of my own contriving. Now I am ready to let them loose. The result will be simpler than the complicated methods employed. Suffice it to say, that as I pull the master switch, and simultaneously therewith, Garth Sankar, my subordinate, pulls a like switch at the north pole, incalculable electromagnetic force beams will surge into the T towers, will crash out into space through the carefully focused cross tubes—but in equal and opposite directions. Here, at the south pole, the force beam is directed toward the constellation Hercules; at the north pole, toward the sun itself."

His eyes swung sardonically toward Kingsley, panting with helpless rage in his prisoning chair. "The principle is simple," he went on softly. "Newton's law of action and reaction. As the electromagnetic beams leap out, they kick back with an equal and opposite intensity. By special transformers, I have amplified the kick-back, braced it against the solid earth as at the fulcrum of a lever. The earth, urged in opposite directions by the applied beams at its poles, will turn on its center as on a pivot, until we have swung to a new equator, and the equator itself will become a meridian of longitude."

He turned, faced the emperor. "We are ready!"

The fat, bespangled man leaned forward. "Proceed!" he ordered.

The visor screens leaped into life. An asbestos-inlaid dome, twin to that in which they were, swam into being. A short, dark-haired man stared out at Crusard. Crusard nodded.

"Contact!"

"Contact!"

KNIFE edges sliced into copper grooves simultaneously. At once the great building shook and rumbled with an earthquake roar; the ground rocked and vibrated underneath. With a howl, as of a thousand crashing, lightning bolts, the great electrostatic orbs spun on their gimbals, blazed with blinding sheets of flame. Rivers of blue fire raced through the wall vacuum tubes; the overhead magnets whirled in rotation so swift that they were but blurs of motion. The lifeless air crackled with electrostatic potentials; lambent sparks sang their frictional songs around the assemblage; each man's hair reared and stiffened upright like the locks of the Gorgon. The emperor paled, fell back cowering in his chair. The high officials on the dais clung paralyzed to their seats, hoarse cries smothered in their throats, fear explicit on every face.

But Crusard, over whom little fox fires danced and played, retained his preternatural calm. His somber eyes were fixed upon a subsidiary screen, on which a representation of the orbed earth appeared, spinning on its axis.

Kingsley, stunned, astounded, blasted by the din of sound, the overpowering glare of unleashed energies, followed his gaze. It was incredible, impossible, even with the limitless forces at Crusard's control, that he could fulfill his boast, and turn the vast, inertial earth as on a pivot.

But there, on the screen, even as he stared with unbelieving eyes, the pictured globe trembled, swayed gently to one side. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, yet with remorseless steadiness, its motion magnified by swinging pointers, the rooted planet turned from its immemorial poles, turned toward new axes and a new rotation. Slow the inexorable sway appeared on the screen, but Kingsley knew that they were toppling at the rate of a thousand miles an hour. Within less than six hours the required turn would have been completed, and an incredible new era commenced!

Crusard's calm voice, amplified by loud-speakers, raised above the howling tumult. "There is nothing to fear," he said. "Antarctica is bottomed on the rocky substratum of the earth. I have calculated the strains. It will resist the shift of direction. So, too, will our native rocky land." He smiled thinly. "I cannot say as much for all the rest of the world. But while we wait, let us solace ourselves with the sight of those nations of the earth who once dared oppose our righteous mission."

The great televisor lighted again. In spite of his nausea, in spite of his horror, Kingsley could not help but look.

LONDON, ENGLAND! The Tower, the House of Parliament, Nelson's great statue in Trafalgar Square, appeared like dark oases in a beating, howling storm of rain. Above the clouds, the sun rocked steadily toward the south, dropping lower and lower on the horizon. Even as they watched, the rain turned to snow, to sheeted lumps of hurtling ice. The conglomerate masses crashed upon the buildings, buried them under tons of frozen water. A hurricane sprang up, howled upon the defenseless land with incredible fury.

The populace, like swarms of terrified ants, ran helter-skelter about the streets, shrieking and crying upon the remorseless heavens. The pelting ice crushed them to earth; the wild storm sucked them high, dashed them to ground again; the buildings toppled and buried them in vast debris, the mingled snow and ice reared in frozen drifts and stifled their lamentable plaints. The English Channel, the North Sea, inertial against the positive pull, reared up in a mighty tide one hundred feet in height, crashed with resounding fury upon the lowlands of England, transformed them in the twinkling of an eye to an inland sea of raging, tossing waters.

"One enemy is obliterated," Crusard spoke as if he were on a lecture platform. "Here, on Antarctica, we are protected from the worst effects. The shift of position drains the winds and ice molecules away from us, toward the old equatorial belt, and we possess a mean elevation of three thousand to four thousand feet above sea level. Now let us turn to France."

Paris! Kingsley stared with dull despair. He had spent his youth in that gay city. Now it was a frozen blanket of featureless ice, from which the gaunt skeleton of the Eiffel Tower emerged like a prehistoric monster mourning its ancient dead.

Again the scene shifted. The emperor's realm. Here, too, the wintry blasts howled and roared, and the snow was falling thickly. But they had been prepared against the day. High in the mountains, in vast caves pre-hollowed for their use, the population held vigilance. Thousands of cargo planes made serried ranks in special shelters, waiting for the storm to subside, to transport the people to their new land.

New York! Kingsley groaned and clenched his palms until the blood ran unheeded. Farther south than the great European capitals, the full fury of the change had not as yet reached that cosmopolitan city. But it was pitiful enough. A gale of a hundred miles an hour lashed the devoted city, the Rockaways were under water; the snow was already a foot deep in Manhattan; the Empire State Building, the Chrysler, the Woolworth, rocked and groaned under the fierce torsional twists of the earth's change of direction. The American government, acting with decisiveness, was evacuating the terrified people of the seaboards, carrying them inland.

China! Here was tragedy stark and naked. China, up the plateau of the Gobi, up to the rampart of the Great Khingan, was no more. Its low, teeming fields, its spawning millions, were buried under a limitless flood of yellow waters——

Already the luminous pointer hovered near the forty-five-degree angle, the angle which, according to Crusard's calculations, would make Antarctica into a temperate and semi-tropic clime, and bury Europe and North America in eternal ice.

Fred Kingsley sat in a daze. His brain was numb with mingled hate and despair. Twice he had shrieked out wild denunciation; twice the guards had thrust him down with savage shoves and alert revolvers. There was nothing he could do now. Earth and all its fair civilizations were destroyed. Mark Alden was entirely obliterated from his mind. In the crash of a planet, what meant a single individual?

"And now," he heard Crusard through the agony in his brain, "we have almost reached the goal. It is necessary, therefore, to reverse the process, to apply our force in the opposite direction, so that the turning earth may be braked to a stop at the very point we desire."

Again the great televisor shimmered with the picture of the North Polar Station. Garth Sankar stared inquiringly from the screen.

"Reverse your force beam until further notice," Crusard ordered.

The short, dark man nodded briefly.

His hand reached for the master switch.

"Contact!"

"Contact!"

The earth cried out in shuddering torment at the tremendous strain. The machines howled and pounded with even mightier tensions. The great dome rocked and groaned. But the pointers of light on the subsidiary screen slowed down their forward march, approaching the forty-five-degree angle as an infinite limit.

"In half an hour," Crusard announced, "the earth will have stabilized on its new axis, and the era of our undisputed supremacy commenced."

In half an hour, the thought drummed in Kingsley's skull, the earth would be wholly prostrate, the prey of these mad lusters after power, and he could do nothing to prevent it.

The din was frightful, the temblors more violent. All eyes were focused on the telltale representation of the spinning globe.

A GUARD issued from the subterranean passage, walked swiftly across the heaving floor. No one noticed him. He was bearded and dark; his clothes were the drab gray of the soldier. A sergeant's chevrons were on his sleeve.

He approached Kingsley's guards with an air of command. "Here, you men," he ordered roughly. "You're wanted below on the last level. There's a break in the lava controls. All hell's beginning to break loose. Report to Captain Gorm at once. I'll take care of your prisoner."

The guards saluted, stared doubtfully. "But Dr. Crusard himself told us to watch this spy," one of them protested.

The sergeant's face grew black with anger. "Swine! Do you dare disobey an officer? Do you wish me to interrupt the great doctor in his work because you do not understand? Even now, while we stand gabbling, the lava is pouring through, will blow us all to hell if the leak is not fixed. Captain Gorm has ordered me to send him every man I could find to build new barricades. Begone, before I shoot you down like dogs!"

The soldiers wilted before the wrath of the sergeant. With muttered apologies they slunk off, eager to be away before he made good his threat. Kingsley, dead to all else but the terrible drama on the screen, felt a sharp dig in his ribs, a sharper voice in his ears.

"Quick, Fred, start for the tunnel—not too fast, not too slow. We want no notice."

He stifled the sudden exclamation in his throat. Obediently, he arose, walked on steady feet, though his brain was throbbing, toward the opening that led to interlacing, intricate passageways. Behind him, alert, automatic a steady sheen against his ribs, walked the sergeant.

No one saw them go, or seeing, paid any heed to a commonplace shifting of a captive. And Crusard's back was to them, eyes intent on the controls.

Once within the welcome obscurity of the tunnel, the scientist cried out in strangled, incredulous tones. "Mark Alden! How—when?"

Mark's voice cut through like a knife thrust. "No time for explanation now. I've been hiding, slinking along miles of underground corridors, listening, getting the lay of the land. I had to kill a sergeant who got suspicious. I took his chevrons. But there's no time to lose. Your disappearance will be discovered soon, and there'll be a man hunt. We've got to make the most of our short liberty. Have you found out the mechanism of what Crusard is doing?"

"Yes."

"Good. What can we do to stop him?"

"Nothing!" Kingsley's words were dull, round pebbles falling into bottomless pools. "Nothing at all. Unless we can capture the dome, gain control of all the mechanisms."

"Stop talking nonsense, man," Mark rasped impatiently. "There are a thousand armed men in there, with fifty thousand more at call. Think! Think hard! I took you along because you're the scientist. I'm not. Every second is precious."

Kingsley thought hard, thought with an intensity that started beads of perspiration on his brow. Mark crouched beside him, sweeping the corridor with anxious glances, finger taut on trigger.

A light dawned on the scientist. "There is a way," he jerked out, "a million-to-one chance. Do you know where the televisor controls are housed?"

"Yes."

"Swell! Take me there as fast as possible."

"Follow me."

MARK dived down an intersecting tunnel, Kingsley directly on his heels. Barely had they merged in the sheltering darkness when heavy boots pounded up the main passageway. Two trembling soldiers, headed by a scowling officer with the insignia of a captain on his shoulders, were rushing to report the fraud that had been committed on them.

Mark, unknowing, sped through the maze without a single pause, a single hesitation. He had used his skulking liberty to advantage. The ground rumbled and rocked beneath them as the earth slowly braked to a halt. In a minute more stability would be achieved, and the orders sped on the tight-beam ether channel to the north pole to cut off the power.

Mark stopped abruptly, raised his hand for caution. Before them was a door, transparent, of heavy, shatterproof glass. On the other side, the tunnel widened into a chamber. Visor screens made profusion in the interior; a hundred thick cables penetrated the walls in all directions, came to jointure on a plugger panel. Two men were inside. One sat before the board, making rapid connections, disconnecting other lines. The other lounged at his side, a gun peeping out of his holster.

"In another minute it will be too late," Kingsley whispered in anguish. "We've got to get in before then, or else——"

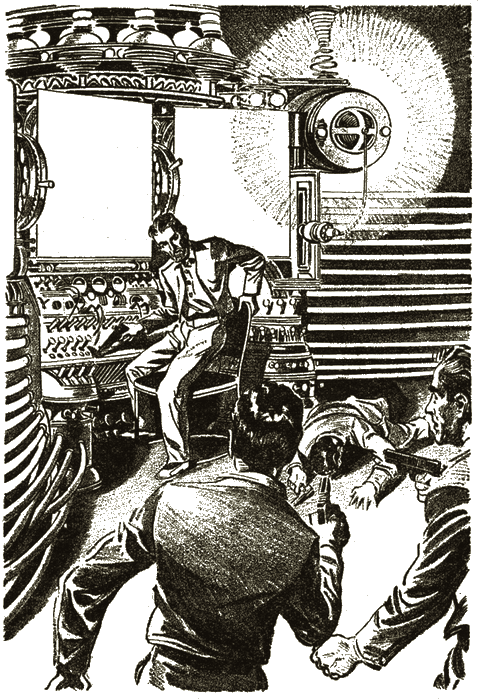

Mark tensed, hunched his powerful shoulders, crashed headlong into the door. The glass starred with cracks, but did not splinter. Yet the lock, already weakened by the strain of unimaginable forces, ripped, gave way. The door fell inward with a terrific crash. Mark catapulted headlong into the room. Fred Kingsley was right behind him.

The guard whirled at the racket. His gun whipped out of its holster. Mark shot him through the heart. He fell without a cry. The visor-screen operator turned ashen face, reached desperately for a plug to spread the warning. Mark shot him, too. He slumped down in his chair, his nerveless fingers slipping from the warning signal.

The visor-screen operator turned ashen face, reached

desperately for a plug to spread the warning. But...

"O.K.," Mark said grimly. "Strut your stuff, Fred. They'll be down upon us shortly. I'll guard the entrance while you work."

Kingsley shoved the dead man callously from the chair, flung himself into it. Precious seconds passed while he familiarized himself with the controls, with the code of the various stations on the chart that hung above the board. Already signals were buzzing impatiently, as Crusard in the central dome clamored for connections.

Then the scientist set to work, racing against time. He snatched up a huge cutting shears from the chest of repair tools next to the board, snipped all cables but the single one that connected with the outside world beyond Antarctica. Then, just as deliberately, he crashed the visor screens. Only the solitary outlet of radio was left, without television. He plugged that in, on a special beam, hunched over in an agony of waiting.

Mark, straining ears to catch a certain far-off uproar, faint above the creaking and groaning of earth itself, said without turning his watchful gaze, "Time's almost up, old man. I hear them coming."

THEN a voice spoke out of the amplifier. "I hear your signal, south pole, but I don't see you on the screen."

It was the voice of Garth Sankar, keeper of the North Polar Station.

Kingsley spoke, and Mark jerked his head back in surprise. He could have sworn that he had heard Dr. Paul Crusard in the room. The scientist's tones were calm, slightly nasal, supercilious. "There has been a break in our apparatus, Garth Sankar," Kingsley imitated. "The earth convulsions have been more intense than I anticipated. Only, this single radio line is left for communication, and I expect it to snap any moment. Listen to me carefully, and follow orders.

"There has been trouble. We have been attacked by the combined aerial fleets of the world. They have cut our power. We are insulated, fighting desperately. On you depends the future of our people. Set your force beam with an automatic stop for nine hours, sixteen minutes exactly from now. Never mind why; there is no time for explanations. Put all your men on the battle planes, hasten south to our aid as fast as you can travel. Hurry!"

"But I don't understand," said Sankar's humble, yet worried voice.

"Hurry! Hurry!" Kingsley interrupted in sudden, assumed anguish.

"The enemy is here; they are——" He reached over, snipped the last remaining cable.

"They are here," Mark told him calmly. The chamber reverberated with gunfire. Down the long corridor were shouting, running men.

Mark fired again. The leaders stumbled, fell. The rest pressed on. Life would soon be over, but Kingsley spent his last moments in smashing the panel board, detector tubes, grids, in a veritable orgy of destruction. It would take days to repair the damage, and in that time——

Mark flung a last bullet into the close-pressed, shooting mob, whirled on his friend. "Come on; we're going places!"

"Where to, and how?"

"To short-circuit the T tower. Get through the door in back of you." Kingsley swung around. He hadn't seen the inconspicuous exit. He made for it—just in time. Steel slugs sang their song of death and destruction all around them. Mark refilled his clip as he ran. Howls of rage followed them—howls and swift pursuit.

But Mark, at each turn, flung deadly lead at the foremost, and gained additional breathing space. The wrenching, earth-ripping quakes had ceased. The silence of the elements was more ominous than the loudest roar.

Mark's face was grim as he sped through devious paths. "Crusard has cut the power," he panted.

"I figured on that." Kingsley labored for breath. "I gave Sankar double time to make up for it."

"Crusard can rig up an emergency radio to countermand your orders."

"Let him. By the time he establishes communication, no one will be there. Sankar and all his men will be flying here to help repel a mythical invasion. The only thing that worries me is that Crusard will reverse his power here, and neutralize the force beam at the north pole."

"That's why," Mark interjected, "we're going for the T tower."

They saved their breath for the grim business of running. They had outdistanced pursuit, but the gap was not wide. And Crusard would have brains enough to rush troops outside to all the exits.

Then light dawned ahead. Not the artificial light of the passages, not the dim twilight of the polar sky, but hot, blinding, dazzling sunshine. The sunshine of Florida, the blazing brightness of the sands of Nice. They emerged on a scene of tropic splendor. The south pole was unrecognizable.

A huge sun rode high in the heavens, the once steel-hard earth was soft and crumbly underfoot. The heat was intense.