RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, June 1936, with "Ecce Homo"

BEHOLD THE MAN! Ecce Homo! The heir of all the ages, the sum total to which the driving evolutionary force that had infected the first formless blob of protoplasm with the strange disease known as life had inevitably led—El, superman of the millennial century!

El lay snugly encased in his bath of nutrient liquid. He was perfection, the ultimate! The long, slow climb from the amoeba was over. All the strange, queer, primitive forms that had inhabited the Earth for millions of years had existed only that El might eventually be achieved.

It was for him that life had spawned and struggled; it was for him that a hundred thousand types had been tested and cast away as wanting by a carelessly profuse nature; it was for him that ape-like forms deserted their trees and used prehensile thumbs for grasping tools and weapons instead of branches; it was for him that the savage grew into a society, the society into a primitive civilization.

It was with him in mind that man toiled and pioneered and invented and fought, climbing through the slow, inevitable ages toward the godlike. El, physically immortal, mentally omniscient!

Long before, unimaginable centuries of time, Earth had been inclosed in a crystal shell, even as El. No wandering meteor could pierce its infinite hardness, no inimical radiation from the explosions of extra-galactic space could penetrate its exterior. Air and water and warmth no longer seeped in irremediable waste into the outer void; weather was a function under strict control. Coal, oil, tides were long forgotten. The almost infinite power of the atom furnished warmth, food, motive force, everything.

El was a geometric round, a membranous sac immersed within the nutrient liquid of the sphere. Nothing else! But his constant attendant, Jem, was a man, normal in form and limbs, not much dissimilar from the primitive creatures who had inhabited Earth as far back as the twentieth century.

Jem and his kind had been bred carefully for static, non-evolving qualities. It all dated from that vast upheaval in the eighty-ninth century, after the cataclysm. The survivors of mankind had divided into two classes. The Masters forged ahead, under the leadership of one Jones. He had discovered the secret of controlled mutations. Drosophila flies, exalted to the nth degree, so to speak. Methods of shifting genes, those tiny units of heredity within the nuclear material of the cell; methods of chemical activation of desirable genes and eradication of those that seemed unnecessary.

OF course, the initial efforts of Jones were halting, somewhat fumbling. But the race he evolved, with accentuated minds and specific talents, improved and reimproved, until—behold! El and his kind came into being.

There were only a few of these. Naturally! Jones had a certain fierce contempt for the vast body and generality of mankind. It was a pity, thought he, that the cataclysm had not eradicated the unwanted commoners. But, being a biologist, and not a man of war, he devoted himself to his super-race, his aristocracy of Masters, rather than to the completion of the task of destruction.

As for the others, the progenitors of Jem, they were at first permitted to spawn in the teeming disorder of an elder day. Gradually, however, as the Masters grew separate and apart, and the gulf widened between them, it was inevitable for the normal, primitive type of humans to become subject and subordinate, to be given the menial tasks of life.

As even these were eventually taken over in toto by the ever-increasing complexity of the machines, and the manual, laborious work of earlier times became a dim anachronism, the usefulness of the Attendants grew less and less.

Then it was that the Masters of the hundred thousandth century took them in hand—though even then, the term "hand" had become purely a metaphor, a figure of speech, related to nothing physical in the structure of the Masters.

The Attendants were ruthlessly exterminated as lower forms of life whose presence disturbed and cluttered up the surface of the Earth. All, that is, except for a certain number, thereafter carefully to be bred by a proper manipulation of the genes for loyalty, submissiveness, for fanatical devotion to the Masters. Not, it must be understood, to the body of Masters as a whole—the supermen were too fiercely individualistic for such low-grade, communal conceptions—but for lifelong attachment to a single Master, and that one alone.

But to return to El, in that unimaginable century of the future whose very number was staggering. The ideal had been reached, the end of all the Masters' artificial evolution. Beyond him there was—nothing!

He was a round, membranous sac—the perfect geometric figure. He had no arms or legs or other vestigial organs. They were useless. Translation in space, the satisfaction of all physical needs, the regulation of a well-patterned world, were all infinitely better accomplished by the vast complex of machinery, automatic, robot-like, self-starting, self-regenerative. Nor had he heart or lungs Of the muddled, intricate mess of viscera and skeletal framework of an earlier era.

Consciousness, thought, awareness, intellectualization and brooding on the few remaining unsolved problems of the universe—what else was required? So that, in the interests of symmetry and a beautiful, ordered efficiency, El and his brethren were evolved.

Without arteries to harden, bones to grow brittle, hearts to wear out, stomachs to ulcerate under the pressure of crude, natural foods, small wonder that he was immortal! A huge, convoluted brain, enclosed in an indestructible sac, in turn inclosed in a bath of nutrient ichor, which oozed by osmotic processes through the sac, and fed, regenerated and cleansed the pulsing brain within.

But, alas! Nature, outwitted, artificialized, twisted into a seemly order by this race of supermen, had exacted a profound revenge! For perfection, the too-perfect, had never been contemplated by a universe of rawness, of cruelty, of alternate birth and destruction, of fumbling trial and error, of blasting nova and lifeless suns, of relativity and expanding, out-rushing nebulae.

El and his mates had achieved! There was no longer anything left for them to seek. The physical, the external, had been conquered, utterly subdued. They alone survived in a world whose every aspect was predictable, controlled. All other forms of life were extinct, destroyed as unnecessary, wasteful—except for the Attendants.

IN an earlier time the Masters had thrilled to the conquest of other planets, but that had also died in the achievement. With their mighty machines, the supermen soon transformed cinder-burned Mercury and frozen-gas Pluto to exact replicas of the Earth. They tired of the game in the course of ages. Even the far off, beckoning stars held no further lure. With their machines they could have hurled themselves across the intervening space, but to what profit? To recreate but another Earth, similar in every respect to the home they had quitted.

So they abandoned the planets and returned to Earth. There were not many of them—so there was ample space for all, for the individual solitude they craved. Slowly, one by one, the few remaining intellectual problems were solved. There was nothing more. Evolution had ceased; growth had become a stagnant pool.

Appalling boredom! Profound quiescence! The weight of passivity grew insupportable. The machines required no attending, the devotion of the Attendants was almost the only fillip left to life. A fierce possessiveness waxed in the highly convoluted Masters, an overmastering delight, ludicrously primitive, for the constant little ministrations of these static replicas of primordial time.

Had there been a spirit of covetousness, too, of desire for the Attendants of their fellows as well as their own, all might yet have been well. For this would have produced dissatisfaction, biologic urges, envies, annihilations, war—and perfection would have exploded with a loud, resounding crash. Life would have been recreated on a lower plane, raw, cruel no doubt, but with the upward path a shining incentive before them.

But, unfortunately, the Masters were supermen, complete. They looked not with envy upon the Attendants of their fellows; they had sufficiency in their single slave. Not that their services were required; the machines could have performed the little tasks far better. But the Attendants had become a fixed tradition, and the Masters looked upon change as something brutal, primitive, from which their delicate convolutions shrank with fastidious repugnance.

The need for change had died. Processes slowed, ceased. So slowly, so imperceptibly, that one by one the Masters passed into oblivion without any one, not even the hovering Attendant, quite knowing that he had died.

Their deaths were nothing organic, had nothing to do with disease. They represented merely a cessation of energy changes, a degradation into a waveless, motionless state of inertia.

EL observed the slow attrition of his fellows with what was at first indifferent torpor. What did it matter? What did anything matter? Being or nonbeing; it was all the same. He lay in his bath, feeding automatically, soaking in with a vast quiescence the physical impressions of the universe.

He had no eyes for seeing, no ears for hearing. Instead, every quiver of a molecule in the material scheme of things; every shift of state of an electron in its orbit, sent its pulsing waves through empty space and barrier matter alike to impinge on the delicate convolutions of the brain.

The hidden round of the Antipodes, the masked, invisible nebulae of the outer darkness, disclosed their secrets to his receptive neurons equally with the physical texture of Jem, hovering interminably before his crystal containment.

El yawned—that is, if a yawn had been possible. A settled boredom was upon him. Jem, the hundredth in descent of a long, remote-stretching line of descendants, no longer amused him.

Jem fed him deftly. It was almost his only function. For this he had been reared; for this he lived, until his specific span of mortal years was ended. Five hundred years an Attendant lived, and died to the expected second.

Jem soon finished his task, then humbly fed himself with a cruder, more bulky food out of a special container in the carrier machine. He was tall, youthful-looking, virile, handsome by the standards of an earlier age. He had been bred for physique and regularity. As the machine rose and flew swiftly away he squatted before his master, in patient, perpetual expectation of new commands.

El's gaze—a crude term, expressing really the patterned interior reception of energized states—flicked over him indifferently. He was tired of that perpetual attitude. He was tired of everything, even the ichor that nourished him. His gaze drifted past him, over the smooth, hard expanse of Earth, a vitreous, even floor on which no tree or tesselated patch of grass broke the monotonous stretching, past the cities of the machines, seeking for the nonce the quiescent spheres of his fellows.

Round and through the Earth he bored, seeking. Something sharpened within him, quivered—a strangely new sensation, the first almost in uncounted years. The process had been so slow, so imperceptible, that, though the perception of it had naturally impinged on him as it progressed, awareness of its totality, of its meaning, had completely eluded him. Now for the first time he saw what had happened through the sluggish centuries, saw it with a realization that ripped through his quiescence like a flash of atomic disintegration.

THE race of Masters had died out—they and their respective Attendants! On all the Earth, in all the universe, only two remained: El, and—at the Antipodes—Om! His similar sphere glowed in the eternal rays; it cradled in its hemispherical base even as El's did. And, squatting before its majestic orb, was an Attendant, a female, tall and straight even as Jem, but with slimmer limbs, more delicate face.

El and Om, sole remnants of the race of perfect beings! The rest had ceased to be, quietly and willfully, seeing no good reason to continue an interminable sameness of existence. One by one, each in his respective sphere, until the machines, finding the ichor untouched and the Attendants gone or sprawled in moveless death, removed the master—a bulge of brain sac in a clouded fluid—for swift incineration in the disruptor tubes.

A quiver coursed through El's involved convolutions. Thought shimmered and played with lightning swiftness. Strange stirrings moved, and had their being within his depths. Neurons darkened with chemical change, long-disused synaptic paths channelized and broke contacts with breath-taking rapidity. For the first time in misty eons El felt the surge of new ideas, of the strange and novel rise of fierce, urgent emotions of which he had had formerly only an intellectual, apathetic awareness.

It was a tremendous sensation. The gray, pulpy matter of his being actually shook within its sac, like a storm-swept sea. It was agonizing, delicious in its very tortured unaccustomedness. Life suddenly blurred and misted at the edges, evolved before him with incalculable forces. He almost sang and exulted. A faint buzz of electric friction actually exuded through the sphere. Life had a purpose, meaning, direction, once more. He tested his emotions and found them good.

What were they? What had caused this sudden snapping of the self-sufficient, moveless perfection of an ageless time? What strange, illimitable forces had been brought into play? The answer is exceedingly strange.

It was the sight of Om, his fellow and equal; it was the sight of An, his attendant. From the tiny dislocation of a single atom a new universe is sometimes born; another destroyed. El knew the majestic march of cause and effect, but for the nonce he possessed not his former wisdom to probe them deeply and without distortion. Certain emotions had been born in him full grown, and they clouded his ordered faculties, hid the future. Which was excellent; which was the very essence of life!

"Jem!" he said to his attendant, "come closer. We are going to visit Om." Now it must not be considered that El had a mouth, a larynx for the formation of sounds. His speech was a mechanical contrivance, activated by the electric surge of his brain. For himself, for the rare conversings with his equals, mere willing was sufficient.

Jem was startled. It was on the most infrequent occasions that the master spoke to him, and then only on little matters of really inconsequential attendance. But this was staggering. Never, in his memory, had El stirred from his timeless, moveless condition on his cradling base.

"Om?" he queried vaguely, puckering up his brows with unaccustomed thought. He did not know Om; had never seen him. His eyes were the eyes—a little sharper focused, perhaps—of the man of the eightieth century. He could not see around the earth, some twelve thousand miles away.

"Yes, Om!" his master repeated with a touch of impatience—a wholly new quality. "Obey my orders, fool."

AS in a dream, and because obedience was a matter of inherited genes, Jem moved forward, close to the sphere. A strange force caught at him, sucked him sprawling to the crystal convex.

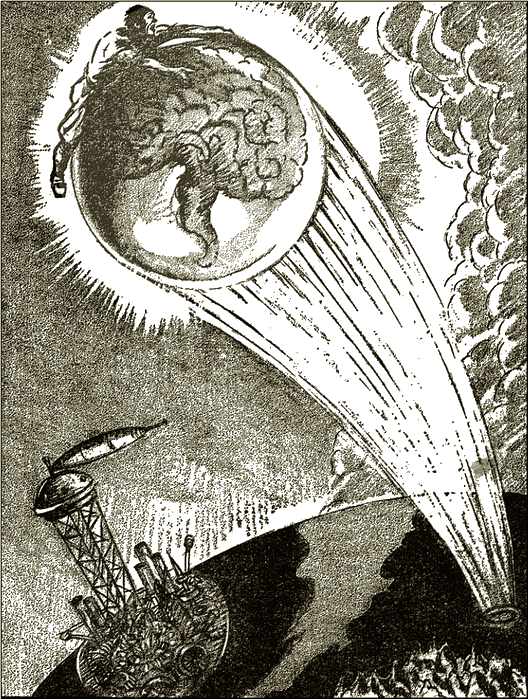

Then, suddenly, the orb with its immersed perfection, rose into the quiet stillness, fled with whistling, blasting speed through resistant air, over whirring, ever-functioning cities of the machines, over huge, wide monotonies where nothing stirred, nothing moved. Earth was a vast graveyard, devoid of life, of all things but the soulless, unknowing machines.

The orb fled with blasting speed through resistant

air, over the ever-functioning cities of the machines...

The wind howled and tried to pluck Jem from his eerie perch; the breath labored and gasped in his lungs as they rushed along. In a thrill of strange new terror he cried out to his master to slow his awful speed, to return to his familiar base and renew the ordered quiescence of his former being.

But El paid no heed. For one thing, the novel wishes of his attendant were weightless, insubordinate even; for another, a fierce impatience glowed within him, a sparkling, crackling turbulence that surprised, even as it elated him.

Like a plummeting meteor the sphere plunged to Earth beside Om, settled without a jar. A carrier machine came swiftly forward deposited a hemispherical base on the ground, and went off in noiseless flight. El lifted, dropped into the base, settled into seeming quiescence.

The force of supermagnetism that had held Jem gasping to the incasement of his master, vanished as suddenly as it had sprung into being. Jem tottered back, loose, befuddled, his brain, unused to cataclysms of this order, seething with new impressions. The sight of Om was not in itself disturbing. He was like unto his master, indistinguishable as star with star. But An!

He had seen only one other Attendant before in all his life—a male who had wandered masterless into the restricted horizon of his vision, and toppled dead on the hard, smooth surface. But this creature, who had cried out sharply at the terror of their whistling approach and had been silent ever since, staggered him!

He sensed that she was like unto himself, yet somehow subtly unlike. She was slimmer, more delicate, for one thing. Strange sensations welled through him; sensations he had never experienced before.

She was watching him also, a little apart, with sidelong glances, that pretended to be unaware of his presence, yet embraced him completely. They did things to his internal economy. Delicious thrills coursed over him, set him tingling.

An irresistible urge swept him closer; to touch her, to feel for himself this new miracle. Never before had he forgotten, like this, even for an instant, his consuming absorption in his master. She must have sensed his parlous state, for as he moved, she darted swiftly, gracefully, to the other side of Om's encasing sphere, as if for protection. Jem stopped, bewildered, like males in all the ages, at this rebirth of feminine coquetry.

Om knew that El had arrived. It was an invasion on his privacy, a thing that had been scrupulously respected for an hundred thousand years. But he did not resent it. Resentment had no place in the perfect end product of evolution. What did it matter anyway? The mere physical transposition of a fellow being did nothing to color existence with novelty for him. Had he wished discourse with El, he could easily have held it at twelve thousand intervening miles.

But what profit would there have been in discourse? El knew nothing he did not know; both were perfection, holding already in wearied embrace all the knowledge, all the inner contemplations, of a known and patent universe. So he said nothing, did nothing, to evidence an awareness of El's presence. In fact, it had already retreated into the recesses of his consciousness.

FOR a long while there was silence, profound, immutable. The attendants had squatted once more before their respective masters, seemingly engrossed in their tasks, seemingly unaware of each other.

El waited a decent interval. Inwardly he seethed with impatience, with eagerness to put into effect his carefully mapped out plan.

"Om!" he permitted the thought to emanate.

"What do you wish, El?" The query came back without any sign of interest, or real desire to be informed.

"You and I are the last of our race."

"Yes, I know." Om betrayed no excitement. It was a mere affirmation of an unimportant fact.

"Our fellows died," pursued El craftily, "because there was no reason for further existence."

"That is true," responded the other indifferently.

"Why do we not do the same?" inquired El. "I am wearied of continued, interminable sameness. An eternity of dead monotony appalls me."

"The universe will not last forever," Om pointed out.

"It will last for frightening eons," El declared.

"We shall cease to be, even as our fellows, before that, no doubt," said Om and withdrew his thoughts.

But El was not discouraged. "Why should we wait?" he asked. "Let us seek the ultimate extinction now, at once."

"It would be senseless effort."

"Not at all," El persisted. "Do you realize what it would mean? The deliberate destruction of our own entities. The lopping off of immortality with a single, sharp and speedy stroke. The one thing that none of our kind has ever experienced. Something new at last, something novel in the long, wearisome history of the race. The one thing we have sought in vain in a too-obvious universe. The thrill of suicide, the notable defiance of ourselves.

"Come, let us join in this last mighty gesture. With one stroke we wipe out life in toto, leave an infinite space time to the sterile movements of insensate electrons, protons, mere puckers in the texture of the all. What say you?"

Om stirred. His brain sac quivered in its nutrient bath. El had insinuated something new in his concepts. Suicide, self-annihilation, the elimination by their act of life itself! They twain, alone and solitary on the pinnacle of perfection, achieving at one irreversible stroke the superpinnacle of a superperfection. Beyond them nothing—nothingness! Now and for all eternity! A magnificent conception!

El waited with strained anxiety for the answer. Had his arguments, born of his newly acquired state, won over the calm, broodless indifference of his fellow solitary?

"Very well," said Om at last. "It is no doubt the best way for us to end. How shall we accomplish this ultimate act?"

A surge of exultation swept over El. He had won! But carefully he veiled his thoughts in a closed electrical orbit. Only the answer he willed emerged.

"Very simply. Do not exert yourself. I shall take care of the matter myself. I shall call the machines."

Not for thousands of years had it been deemed necessary to call the machines. They were self-energizing, self-reproductive, geared for all possible required tasks. But now, in obedience to the short-wave impingement of El's will on key units in the city of the machines, two great metal monsters, with pointed noses like ancient torpedoes, rose swiftly from the towers, sped like hurtling asteroids along beam channels direct for the waiting, immovable spheres.

Om watched their rushing progress with calm indifference. In seconds there would be a crash, and then——

"Their paths include the orbit of our attendants, no doubt," he suggested. "They, too, are life, though of an inferior order."

"Naturally," assented El craftily. "I have already plotted the courses." His mechanical voice rasped suddenly. "Jem, stand over to that side—there—do not move."

Om gave like directions to An.

THE two attendants moved submissively to the appointed spot their masters had ordered. Male and female, closer together than two attendants ever had been before, aware of their nearness, feeling a subtle, exotic interplay of forces. Jem saw the hurtling giants of destruction, saw them without fear, without thought of avoidance. It had been El's command. An felt a swift tremor, a surge of something within her she could not understand—yet she made no move.

Silently the masters and their attendants waited. The swift metallic engines came on with a swoosh of screaming air; nearer, nearer. Om's repose was intellectual, controlled. Annihilation, existence—neither mattered. But El concealed his processes in an impenetrable orbit of interlocking waves, waiting for the supreme moment.

Closer! Closer! The great torpedoes—tons of glistening metal—roared directly for the crystal spheres. An cried out sharply. There was a rending, splintering sound. Quartz shattered into a million jagged shards, nutrient ichor spattered geyser-like into the ambient air; a brain sac punctured like thinnest film. Om—a huge, twisted convolution of gray, spongy matter—spread fan-like in a rain of tiny, writhing blobs. Om was dead, annihilated before An's horrified eyes. Her master, the nexus of her being, was no more!

The second machine, abreast of its mate, smashed toward El. Almost at the instant of impact, so close to the fragile crystal incasement that barely a millimicron separated thrusting nose and shimmering quartz, El exerted all his mighty powers to the utmost.

A wave of meshed vibrations leaped out from his quivering brain to meet the invader, an impenetrable force wall against which stellite hardness smashed and fused into a flaming, futile disintegration.

A paean of triumph sang inaudibly in the gray jelly of El. Life sang through him—life triumphant, supernal, irresistible. He had achieved his goal. Om was dead, even as he had cunningly planned, unknowing to the end that he had been outwitted.

El looked out on the universe and saw that it was good. He was the last of his race, the solitary perfection in a world that held no other. What a glorious vista! No longer was eternity a frightening prospect. An endless time was not too long in which to contemplate the mastery of an entire universe, in which to brood on himself—the absolute, the unique, the single splendor!

No wonder his fellows had willfully ceased to exist. They were end products, but the all-embracing egoism from which the spark of life enkindles was not theirs. There were others—even as they. A dead level, a stupid equality of perfection. At one leap he had spanned the gulf, thrust himself into a glorious new state. There was no other El in all infinity. He was the ultimate, the unsurpassable!

JEM sat quietly before his master. Dim, unaccustomed thoughts struggled in his brain, yet without present effect. His task was implicit obedience, adoration. But An—the girl! She had cried out at the sight of her master's immolation. She had seen with wide eyes and affrighted mind the trick that had been played. Anger stirred; a new, a frightening sensation.

El viewed the chaos of her thoughts, read them easily, without effort. He could have killed her easily. According to tradition she should die—a Masterless Attendant. But he had broken with tradition, had placed himself beyond those subtle, binding cords. With this new state had come new emotions. Vanity had been one, possessiveness another. He wished her for himself; he desired more than a single Attendant.

He envisioned other possibilities. For vast ages Attendants had been reproduced by solitary parthenogenesis. Now he would mate this pair, as in the long dim past. There would be variations, complexities. He would rear a horde of Attendants—subordinate forms of life, lowly, submissive—with which to amuse his eternal contemplation. It was good!

"An!" his thoughts filtered through the mechanical enunciator with metallic sound, "your master, Om, has ceased his being. I am your master now. It is my will that you and Jem, my attendant, mate for the propagation of a new race."

Jem stared. He did not quite understand, but vague racial instincts stirred within him. He glanced quickly at An and the sight was pleasing. Her face, so delicate and different from his own, was queerly the color of the distant Sun as it fell unheeded below the horizon.

She did not look at him; could not, somehow. Her heart was thumping; a sense of shame, unfelt before, pervaded her being. Shame, and this new novelty of flaming anger. Then she did a monstrous thing—a thing unthinkable. She rebelled.

"El!" she flared at the moveless brain sac in the crystal sphere, "I will not. I am not your attendant. My master is dead, done to extinction by some incomprehensible treachery of yours. I shall die—it is my duty, my necessity—but I shall not obey your commands."

El could have slain her then and there for her defiance. But he did not wish that. He had plans, bound up inextricably with this new confusion of emotions that coursed through him with novel thrills.

"You shall neither die nor disobey," he said coldly. "Jem," he proceeded, "behold, she is your mate. Go to her!"

Jem was shocked. How dared this strange girl—this being whose nearness made him feel warm all over—defy the mighty master? He moved slowly toward her, obedient to the command of El.

An faced him bravely. Her face was the deep-red of copper, her eyes held strange scorn. "Jem," she said, "come no nearer. I hate you, I despise you. You are not a man; you are an attendant, an obedient automaton to the will of your master."

Jem stopped, dazed, bewildered. The whip of this young girl's scorn cut and wounded. Yet she seemed infinitely desirable, though she hated him. Why? He was only obeying the command of his master, as was right and just. While she——

Still he did not speak. Speech was painful, slow to him. He had not had much occasion to use it. Neither did he advance.

El received the vibrations of his confusion. He saw no rebellion therein; only such stupidity as was normal to an Attendant. El, too, had lost something, though he did not realize it. Perfection had become a little less than perfect. Life in a ferment, fraught with vigorous emotions, could not be static. So that he did not read aright the tortuous neuron paths that were forming in Jem's brain.

ANGER, rage, stimulating, electric, yet clouding to an all-awareness, raced through El. An Attendant, a crawling form of life, had defied him! An, a slim and delicate thing. The metallic syllables of his speech comported oddly with the words. "Jem!" he cried. "I order you—seize this rebel. She is yours. On pain of annihilation I insist upon your obedience. Do not dare aught else."

He had lost his head—to use an ancient phrase. The poison toxins of anger, of mad, unthinking rage, darkened the gray of his convolutions. Thereby he forfeited his dignity, his power.

Jem heard and wondered. He saw the girl. An. There was a new look in her eyes. A look of fear, of helpless, imploring appeal. A feminine appeal. Racial instincts stirred again. He felt protective, masculine. He felt all-powerful in the light of those eyes. Overwhelming rage swept over him. But rage was an emotion suited to his primitive body, its appendages and muscles. What was degradation to a Master was a source of strength to an Attendant. Red madness seethed against the one who had made this girl to hate him, to dread his approach.

Without quite knowing what he did, he bent suddenly. A strut of the machine which El had fused lay on the ground. It was a short bar, incredibly hard and compact. He swept it up into his hand, hurled it with all his strength. The distance was short, the movement exceedingly fast. Yet to El—who could stop a hundred ton missile in midflight, who could, with the exertion of his own inner powers, swing the Earth out of its orbit and send it hurtling to the farthest galaxy—this was child's play.

But El was no longer El! He was a new being, overwhelmed with envy, with passion, with covetousness, with vanity, with rage. In that vital second he was literally blinded—unable to think coherently. Later he would have understood, would have taken measures to regain his old clarity. But it was too late.

The short, thick bar crashed through the quartz, clawed the liquid nutrient, punctured the membranous sac. El gushed forth, an oozing, tangled mass of pulpy brain, to mingle in horrible flow with amber liquid and jagged needles of shattered quartz. El was dead.

Jem stared stupidly, hardly grasping what he had done in that instant of ancient emotion. His master was dead; he was a Masterless Attendant! He had slain with his puny hands the mighty one, the all knowing! The world rocked and reeled before him, the ceaseless vita rays darkened on his vision. A low moan escaped his tortured lips. What had he done? What would happen to him now?

HE was brought to his senses by the sound of some one calling him, by the touch of soft fingers on his arms. "Jem! Jem!" Unaccountably it was An. "I am proud of you! You are wonderful! You have killed the mighty El unaided. I—I love you!"

He opened his eyes, incredulous. What was that? What had she said? She approved—more than that—thought him wonderful! She loved him! Words that had come from remote ancestors, that had been lost for incredible centuries. His chest swelled; he stared with a certain condescension at the adoring girl. He even strutted a bit. "Pooh! It was nothing!" he said. "I could do it again. I am stronger than a Master."

Deep down within him he knew, of course, that El had been the last of his race, yet he actually believed in his newfound strength. Especially in the reflected light of An's eyes. He took her arm masterfully, drew her to him. She did not resist.

But then, in the transports of that first kiss, he suddenly shivered. They were alone—the two of them—alone in an alien universe. No Masters, no other Attendants, only the strange, impersonal machines! He drew back. "What shall we do now, An?" he asked timidly.

"Do?" she echoed with the guile of the serpent, and the wisdom of all women. "Why, dearest, you are a man, and you will provide. There are the machines—you will force them to their wonted tasks. You shall be their master, instead of El and Om and the others who ceased before them."

"I had intended that all along," Jem said hastily. He believed it, too. He bent toward her, whispered something. She flushed as she slipped her arm in his.

"A new race!" she breathed in awe. "A race of men and women like ourselves to people this Earth again, to strive, to conquer, to seek new knowledge always." Her eyes brooded on the infinite with tender gaze, this mother of a new and upward-groping life.

Slowly they walked toward the city of the machines.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.