RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

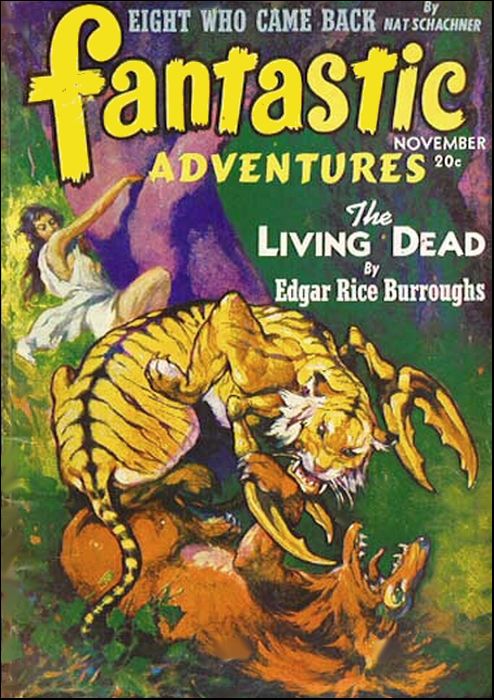

Fantastic Adventures, November 1941, with "Eight Who Came Back"

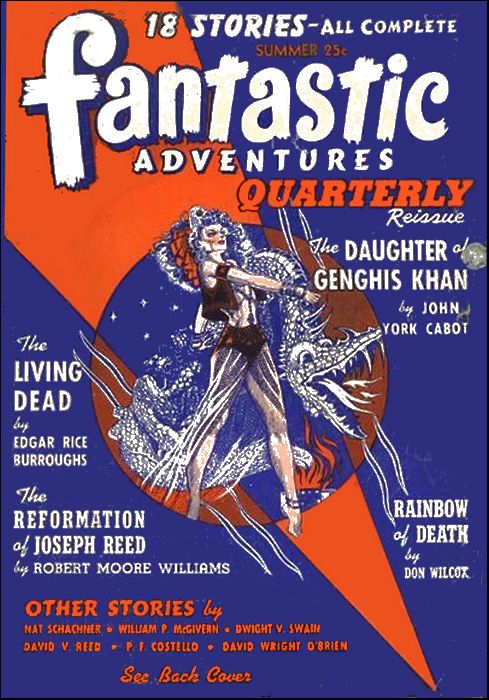

Fantastic Adventures Quarterly, Summer 1942, with "Eight Who Came Back"

They had a plan to remake the Earth, these

eight great men. So they came to life again...

GENE WESTCOTT tried to laugh at himself, as he stood irresolute on the hillside. It was only a dream, he argued that had brought him out into the night like any superstitious rustic. The whole thing was silly. He'd better get back to bed before he caught cold.

"You're a fool," he said.

Yet he went on, in spite of himself. The road led upward over windswept meadows that smelled of pine and fragrant grass. A sleepy cow stared at him and swished her tail. A brown whippoorwill set up its fierce, monotonous clamor from the blackberry tangle.

At the top of the hill Gene paused again. It was his last chance to go back; to return to sanity and a dismissal of his dream as the result of something he had eaten. Doc Lesser would certainly have diagnosed it that way, and laughed at him with the salty chuckle of a man who didn't believe anything that he couldn't measure with his instruments.

The moon was beginning to set behind the wooded plateau to which he had come. To the left was Jared Jones' corn field, odorous with recent plowing. To the right the ground fell away sharply into a ravine. But directly ahead lay the trees—tall, gray-eyed beeches mixed with gaunt hemlocks and clumps of oak. The moonlight swept them with a silver brush and drifted through the undergrowth in broken glitters.

Within the wood Gene knew of a clearing—almost circular, where nothing grew. Not even a stone disturbed the hardpacked earth. Gene had seen it only once, when he had rambled through the hills with Glenda at his side. They had pushed through casually, absorbed in conversation, and had barely given it a passing glance. But these three nights Gene had seen it again, in his dream; so plainly that he could have described every tree, every leaf that rimmed it in.

He hesitated—then the call came again. Stiff legged, Gene walked into the wood.

He came at them suddenly. The moonlight lay in long bands across the clearing. Liquid silver filled it like a bowl. Eight figures stood inside, motionless, waiting.

The white light clothed them in shimmering hues; a frosty mist lifted from the ground and whispered along the insubstantial solidities of their forms. Their faces were silver masks in the waning moon.

"I have come as you demanded," Gene said. "What do you want of me?" He wondered at himself as he spoke. There was fear in him, but not surprise. Perhaps he was still dreaming. In dreams no one is ever surprised by what he sees.

The eight wheeled at his approach. Their burning eyes probed him like keen-tipped lancets. Their countenances were awful with the majesty of those long dead.

"You have taken your time, youngster," one spoke up suddenly. "We have called you for three nights. You have delayed us with your stubbornness."

GENE looked at the speaker. He was a short, squat man with a stomach that protruded like a rounded pot. Yet he was not ludicrous; the piercing blackness of his deep-sunk eyes, his coarse, high cheekbones and the lank straightness of his hair clothed him with strange dignity. It did not require the pale gesture of a hand thrust deep within an ancient waistcoat to tell Gene who he was.

"Speak up, lad," Napoleon repeated in a tone of irritation. "We have work to do and the time is short."

Gene took a deep breath. He felt cold all over, though the night was warm.

"I did not come at first, because I did not believe the vision," he said as steadily as he could.

A figure who stood a little apart stirred. He too was short, and his face was lined with ugliness. His tipped, broad-flaring nostrils, his shaggy brows and thick, protruding lips gave him the appearance of a goatish satyr. Yet when he smiled, his aspect took on an aspect of nobility.

"You are a sceptic, my son," he nodded approvingly. "It is the first step on the path to truth."

"We are not here to quibble about the sophistry of words, Socrates," laughed a bald-headed man with hawk-like features and arrogant eyes. "Let us leave that to Greek slaves and the philosophers. The mists of time have yielded us up for a purpose. Let us cross our Rubicon now, and seize the chance that offers us."

He moved toward Gene, but a ruddy-featured man with a pointed, reddish beard got quietly in his way. Silken hose and plum-colored breeches encased his limbs, and the huge ruff that rimmed his head was immaculately starched.

"Hold, Julius Caesar!" he commanded. "You men of action are forever too abrupt. That was why you gushed out your life-blood with a score of daggers plucking at your flesh. We have strutted once on the sounding stage of this puny earth. Do we really wish to return and repeat the comedy that has already been acted? Let us consider—"

"Bah!" a young man clad in bronze armor and with the classic features of a Greek statue interrupted scornfully. "What does a barbarian poet from a foggy little island on the rim of the world know about such matters? In my time I conquered all possible worlds. Now there are new ones that unfold. Argue your womanish verse with Socrates, if you like, friend Shakespeare; but let those who are men and trust to their swords proceed with action."

"Hear! Hear!" clamored a huge-thewed man with careless, open face and a shock of leonine, yellow hair. "Alexander is right. To the devil with words! When do we start?"

They swayed toward Gene—incredible figures from an incredible past. He stared from one to the other of the crowding wraiths, clenching his hands with desperate tension. He recognized them all—those who had spoken and those who had not. Shadows of those who had rocked the earth with their tread—four who had drenched the nations with the blood of their conquests —Alexander the Great, arrogant Caesar, subtly planning Napoleon, and he who had spoken last, huge of body and simple of mind—Richard the Lion-Hearted.

Four others stood with them—four who had moved the earth with the power of thought and the force of words—squat-faced Socrates, Shakespeare of the mighty line; next him a little mockery of a man, pinching snuff with fastidious gesture and raising Voltairean eyebrows; and, a little to one side, a tall, grave, somber man with trim, brown beard and soberer ruff than Shakespeare—Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam.

GENE WESTCOTT faced them boldly. If they were but the insubstantial fabric of his own mind, they must soon vanish and leave him comfortably asleep in bed; if they were not—and every fiber in his being cried out that they were not—then he must act the man in their mighty presence.

"You have called, and I have come," he told them steadily. "But not because I wished it. You have no right to be on earth; your bones have long since turned to dust."

Shakespeare grinned.

"I see you have read my plays," he observed. "That particular line was a poor one, and had to do with friend Caesar. In fact, the only reason that Sir Francis persuaded me to return with him was the prospect of writing new plays that are worthier of my genius." His smile darkened. "I had ample time to con them whole in the vastnesses from which we come."

Gene said:

"You are dead! It is not possible for you to return. The laws of the universe forbid it."

Voltaire took another pinch of snuff.

"It is true we are dead," he admitted in a dry, matter-of-fact tone. "But in another sense we are still alive. Our spirits loved this earth too much ever to be quit of it. The bodies have moldered, but the essence of us remained—pure thought, pure will, pure brute power, if you wish," he added with a disdainful glance at the great, blond head of Richard Coeur-de-Lion. "As long as there are men who remember us on earth, we wander on, a company of those who dared in the past and are ready to dare again if the opportunity should arise."

"You mean," Gene whispered, afraid, "the opportunity has come?"

The weazened little man nodded. "Yes. We have found a method of returning to the world of men. We are tired of being wanderers in the wastelands of infinity." He grimaced. "It is not pleasant out there."

"Voltaire was always too earthy to be happy out there," interposed Socrates, screwing up his goat-like face. "So were the men of arms. I however was content; and would have remained so if only the ideas of truth and beauty had marched on in this world of yours. But you have gone astray. Brute emotions have taken the place of luminous reason; morbid cruelties the clean sway of sanity. The Greek ideal of a sound mind in a sound body no longer holds. Madmen rule and philosophers languish in concentration camps. It is time to call a halt."

Napoleon grunted.

"It is time to march," he corrected. "Perfidious Albion and the Prussian beast think to betray my beloved France. I shall put an end to that." Gene felt himself shivering. If these eight phantoms were real, then incalculable things were in the cards. They spoke of changing the world to fit their hearts' desires. But already they quarreled; their aims were wholly divergent. What terrible catastrophes might result, once they were loosed upon the living?

Four were soldiers, and spoke of bloody conquests. Good Lord, there was enough of that on earth today! Four were men of thought and intellect. Yet each age must build its own philosophies and systems of life. Gene, who observed the race of man with a sharpened eye and dissected them with merciless precision for the benefit of crowded theaters, knew that. To force the system of an alien age upon the present must lead only to disaster, no matter how well-intentioned and large-souled the promulgators might be. Then a shaft of hope pierced his breast.

"HOW," he asked craftily, "can you return? You are not alive, in spite of these ancient forms of yours you have somehow managed to reassume. After all, you are only dreams, mere memories."

"True!" Shakespeare chuckled, wagging his trim, pointed beard. "We are such stuff as dreams are made of; the insubstantial fabric of the mind. But Sir Francis Bacon—whom silly folk have credited with my lines[*] has found a way. I do not pretend to know the manner of it—I am but a poet, not a wonder-maker. He claims that the subtleties of our immortal thought and will may, by appropriate measures, penetrate gross interstices of mortal flesh and, clad in the lusty habiliments of living creatures, direct them to our will."

[*] Many historians and students of Shakespeare's works have contended that it was his contemporary, Sir Francis Bacon, who really wrote the famous plays. But this opinion has been discredited, and it is generally acknowledged, that although Bacon did write several things, he never wrote a play. He was the world's most prolific scientist, outside of Leonardo Da Vinci, and interested in the most varied of subjects. —Ed.

Bacon smiled somberly.

"Will Shakespeare," he observed, "is not content with pithy speech. He speaks in phrases beyond all compass. The matter is simple. The atoms of our being are infinitely subtle. The corporeal spaces of your fleshly bodies are gross in comparison. By proper means, discovered in the centuries I have pondered the problem, we can interpenetrate your forms, take possession of your earthly minds, and in your shape remake the world."

For a moment Gene stood stiff and silent. Then he forced himself to ask the question he dreaded above all others.

"Where," he demanded, "are you going to obtain your sheathing bodies? Whose individualities are to be dispossessed?"

Richard of England thrust back his shaggy mane and roared with bull-throated laughter.

"You for one, and the good people of that thriving town which nestles yonder in the hills. They seem of sturdy, muscular stock, and of a fair mien." His blue eyes narrowed speculatively on Gene. "Forsooth, you look a likely lad. Clean of limb and well-thewed, withal." His glance challenged the others. "I lay claim to him; do you hear?"

Alexander flung forward, his brow black with anger.

"By Zeus, you barbarian Northerners take much upon yourselves. He is mine; I spoke for him first."

"Nay!" said Shakespeare. "His mind is too subtle and complicated to house your venturesome spirits. The lad is a fellow-craftsman, though much degenerated from the vasty days. His matter limps prosily and his manner is inept. Natheless I claim him for the poor thing that he is."

Napoleon's eyes shot flames.

"I was an Emperor with millions at my slightest beck. Who else in all this company has better right to make a choice?"

Uproar followed. Voices rose angrily. Faces distorted; they shook fists at each other. Voltaire stepped nimbly aside; his sharp, satiric features mocking them all.

"You had better go, young man," he advised, "before they come to their incorporeal senses, and seek to invade you in a body. Myself, I seek no male exterior. I would prefer—strictly as an experiment, you understand—the dainty lineaments of a maid of one-and-twenty. It should prove a most delectable sensation."

Sound advice, thought Gene, and put thought into action. He jerked quickly back into the woods, sped through underbrush and leafy lanes back to the upland pastures; raced down the long slope with sobbing, panting breath.

The moon had sunk beneath the upper rim; the stars made the stony hills into shadowed humps. The noise of quarreling shapes died suddenly, swallowed up in the echoes of his own flight. The cool dawn-breeze fanned his fevered cheeks, pumped air into his gasping lungs. He slackened his head-long pace; tried to grip his whirling senses. He flung a fearful look back over his shoulder.

There was nothing; nothing but the solemn hill and the capping woods. No sign of the incredible array that had called him from his sleep; no sign that they had ever existed. Down beneath, in the valley, the lights gleamed placidly. Nothing else showed. Stonehill was still asleep.

But that backward look was his undoing. He sprawled and went headlong over a jagged rock. His head jarred with a sickening thud. Sparks blazed suddenly; were swallowed up in bottomless gray.

WARMTH clad his motionless form with its healing power; a great twittering of birds penetrated his senses. He stirred, opened lead-heavy eyes.

Awareness flowed slowly into him. He sat up with a groan, stared incredulously about him. His limbs were cramped and his head ached. His clothes were drenched with the night-dew.

The sun was already high in the heavens, and the mist was lifting over the top of the plateau. Cow bells tinkled in the distance: a cloud of dust rolled rapidly along the highway beneath. A steady clanking came from the lumber mill; the nine-forty from Boston hooted along the rails. The chapel bell of the College clanged class-change. Stonehill stirred with its daily life; while he—

Gene blinked; swore deeply yet softly. This was the first time he had ever walked in his sleep. He felt his head. There was a sizeable lump on his forehead. The dream was still vivid upon him; but its edges were blurred. Now, in the clear light of the sun, he recognized it for what it was—an extraordinary nightmare induced by the cold lobster and ham he had snatched from the refrigerator on his late return from the city. Pressure on the nerves that surrounded the stomach, he could hear Doc Lesser saying with a wise shake of his head, transmitted to the delicate fabric of the brain and giving rise to the damndest things.

Ruefully Gene brushed the beaded moisture from his clothes and stumbled stiffly down the hill. His vision certainly classed among the damndest things!

Yet an uneasy feeling persisted as he swung along the chief business street of the little town. He kept to the shadowed side, hugging the trees, watching with half-fearful eyes every one who passed. Thank God they all seemed normal, going leisurely about their daily affairs. Josh Wiley, his lank body bent almost double over the broom, gave a last deft sweep to send the accumulated cigarette butts whirling into the gutter, spat reflectively after them, and turned back into the store. Miss Lucy Hawley fluttered down the street, market basket dangling from her thin elbow.

Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, as long as Gene could remember, Miss Lucy opened the front door of their cavernous house on the dot of ten; on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays Miss Kate did the same. On Sundays both rested.

An ancient Ford chugged loudly along. Doc Lesser leaned out, waved his hand in greeting to Gene, and rattled on. His jovial, rubicund face had not changed in the slightest. Everything was familiar; everything moved according to the unalterable habits of Stonehill.

Something nightmarish lifted from Gene's chest. In spite of his rationalizations, a strange fear had lurked in the odd corners of his being. Suppose he had actually seen those mighty apparitions! But now he was positive. He had eaten in haste and late at night. He had walked in his sleep along the hillside and had smacked his head into unconsciousness. That was all!

HE turned a corner into a quiet back street, and found his house half-hidden among broad-leaved maples. He went up the porch on tiptoe, seeking stealthy entrance. But as he pushed the door open, Mrs. Burdock confronted him, dust cloth in hand, disapproval written all over her angular face.

"Good Heavens, Mr. Westcott," she pursed her lips angrily, "but you gave me a turn. Here I waited and waited with your breakfast, but you never came down. I knocked a couple of times, but there was no answer. Finally I got scared and peeked in; and there you were gone, your bed rumpled and the sheets half on the floor. Where've you been?"

Gene tried to edge past his housekeeper. She had been with him for five years, ever since he had moved to this little New England town to seek the peace and quiet he required for his writing. The drama was a severe mistress; but not as severe as Mrs. Burdock. Spare, angular, unlovely, she watched over his habits with an eagle eye.

"Couldn't sleep," he muttered. "Went out for a long walk."

"Oh!" she gasped. "Look at your clothes; they're a sight. And your head!"

"Fell into a swamp," he said hastily, and escaped to his room. He bathed, shaved and changed to fresh clothes. The lump on his head was going down; he felt better; and the vision of the preceding night seemed infinitely remote. He'd have to watch his diet from now on. Perhaps a little session with Doc Lesser would help.

His typewriter stared at him accusingly. Down in New York Sam Harrow was putting on his latest show. It was scheduled to open in a week; but there were some last minute changes to be made in the lines. He had driven down yesterday to see the rehearsal, and had driven back the same day. It had been a grueling four-hundred-mile trip. That too had helped bring on his last and worst nightmare.

After a breakfast of orange juice, bacon and eggs, marmalade and coffee, he shooed the head-shaking Mrs. Burdock out of the room, and sat down before the typewriter. But the blank paper he inserted into the roller was no blanker than his thoughts. His fingers poised above the keys; and stayed that way.

After half an hour, he said with deep feeling:

"Damn!"

Then he got up. He was still too jittery, he told himself. Which was quite natural, considering that he had walked in his sleep, and had lain out on the hillside the greater part of the night, unconscious. His brain heeded clearing. Perhaps another walk might do the trick.

Yet even as he slipped out the back way, to avoid his faithful housekeeper's accusing glance, he knew exactly where he was going. He was going to walk along the road to Glenda Gordon's. He wanted to see her. Now this was not an unusual desire on his part, but he ordinarily managed to suppress it during working hours. This was different. The queer feeling, a hangover from his strange nocturnal experience, persisted in the back of his head. He would not rest easy until he had seen Glenda.

TEN minutes later he was knocking at the door of Glenda's cottage. It seemed to him that his heart was knocking quite as loudly. He had been in a measure responsible for her coming to Stonehill. She was a rather important artist—at twenty-two her water-colors hung prominently in museums and private collections, and the Whitney Museum had given her the final éclat of a one-man (or one-girl, to be exact) show. She had designed the settings for Gene's last play, and they had become intimate. She came out one week-end to visit him at Stonehill, fell in love with the little New England town and its college campus; and promptly rented a house in which to paint.

He knocked again. The vacant echoes disturbed him. Why was there no answer? Then he heard someone shuffling inside, and the door flung open. Mrs. Crane, plump and motherly, peered out. She looked scared.

"Oh, it's you, Mr. Westcott!" she gasped. "I—I thought—"

"Where's Glenda?"

The scared look deepened.

"I don't know, sir. She slipped out of the house about six this morning, just as I was getting up to start the stove going. She had a queer, set look about her. It was like a mocking grin that had frozen into place. I ain't never seen her like that before. I called after her, but she didn't seem to hear me. She just went on down to the brook at a right smart clip, and disappeared among the willows there. She ain't been back." The housekeeper began to whimper. "You—you don't think anything happened to her?"

Something stiffened and went cold inside of Gene. The jangling bells of his own experience beat disordered tunes in his head. Yet he said with an effort at casualness:

"Nonsense! She must have gone for a long walk. Very likely she's hunting a scene for her next landscape. She'll be back all right."

Mrs. Crane wiped her eyes with her apron.

"She ain't never been away so long. And if you had seen that look on her face—

But Gene was already gone. The memory of Voltaire's phantom rose to torture him. What had that spirit of mockery avowed? A preference for the dainty lineaments of a maid of one-and-twenty. Gene groaned and broke into a run. Suppose it had not been a mere nightmare, induced by an inner upset! Suppose, in spite of reason, in spite of science, the dead had found a way to return!

He crossed the brook by the rickety wooden bridge, raced through the willows and up the fields that stretched beyond.

"Glenda!" he called again and again. "Where are you?"

But only the crickets answered him with senseless chirrupings; and a catbird mimicked his call. He flung himself up the hill, fighting back the terror that assailed him. This was the twentieth century; not the sixteenth. The departed great of former ages could never return. They were dead; science proclaimed the irrevocability of their departure; religion itself made no provision for their return to earth.

YET the fear that gripped him increased as he cut across the pastures to the top of the hill. He did not know what he would find; he did not stop to think of the danger to himself. With what weapons could one fight those who were already dead? Only one thought hammered in his skull. He must find Glenda! He crashed into the little clearing, breathing heavily.

It was bare! There was no sign of the girl or of the life-like phantoms who had peopled it the night before. A wild hope flashed through him. Then it had been in fact a dream. The hope flared—and died. There, on the ground, lay a sodden handkerchief. He picked it up. It bore his monogram. He had been here. It was all true!

He turned and started down the hill again. He did not know that he was running; that his feet had stumbled unawares on the dirt road that wound over the hills. Something rattled and coughed behind him; it caught up to him in a whirlwind of dust.

"Hey!" shouted Doc Lesser's familiar voice. "Where're you running like that, you young idiot? Hop in and I'll get you into town in jig time."

Gene stopped short with a sob of relief. Doc Lesser's genial ruddiness, wagging goatee and twinkling blue eyes under a frosty patch of hair were like balm to his soul. Here was sanity; here was a man who could help.

He flung on the running board, climbed into the bumping seat.

"Thank God I met you, Doc," he said. "I—"

The doctor did not hear him. The rattletrap car was making plenty of noise on the rutted road.

"Just came down from Sabrina Jones," he yelled above the racket. "She got herself a nice, healthy boy. Hardly needed me at all." He chuckled. "I just sorta put my okay on it, that's all."

Gene gripped his shoulder so that the car almost plunged into a ditch.

"Listen, Doc," he said grimly. "I know you'll think I'm crazy; but I've seen eight dead men face to face—Socrates, Caesar, Shakespeare, Napoleon, Alexander and Voltaire, Richard of England and Bacon. Eight of the greatest men of all time. They've got Glenda and they're after seven more. Then they're going to conquer the world."

Doc Lesser braked the car to a slithering halt and shut off the ignition. Then he turned warily toward Gene. His genial blue eyes were deep with concern.

"Now look, Gene," he said soothingly. "You writer chaps sit on your rear-ends too much. You get notions. It's all right putting them into books for other nitwits to read; but it's darn dangerous going around and—"

"I'm not suffering from a nervous breakdown," retorted Gene, "if that's what you're getting at. I wish to God I were! I tell you I've seen them. I know it's incredible; I know it's easier to call me crazy. But if you'll listen—"

Doc Lesser was a keen judge of men and a sportsman. He listened. Nor did he interrupt. Nor did he argue when Gene had finished.

All he said was:

"Hmm! We've got to find Glenda. A bunch like that sounds dangerous."

Gene gestured despairingly.

"That means you don't believe a word I say. You think I ran into some gang—all dressed up to scare the pants off suckers like myself."

"Well—" Lesser surveyed him with a bright smile.

"Isn't that a more reasonable theory?"

"Start the car," Gene said. "We're going into town."

THE two men sat in silence as they bumped along. There was nothing more they could say to each other. But Gene was conscious of Doc Lesser's sidelong glances.

They were nearing the town. The lumber mill thrust its sprawling bulk along the stream, getting its power from the swift current. About fifty men tended its whirling saws and stacked the cut boards in gigantic piles.

"Hello!" the doctor said suddenly. "There's Tim Foley. His wife's been ailing some this past week. Mind if I stop and find out how she is?"

Gene grinned tightly. He knew what was in Lesser's mind. He was scared of him and his hallucinations. He wanted Foley's help.

Tim Foley stood at the side of the road, watching their approach. He was mill foreman, and a giant of a man, with flame-red hair and pale blue eyes that glowed with battle lust on Saturday nights when he had a few drinks tucked under his belt. Otherwise he was good-natured enough, and ruled his burly crew as much with his merry tongue as with his fists.

"Must be twelve!" Gene thought. "The mill isn't working."

Lesser pulled alongside.

"Hi there, Tim!" he greeted the foreman. There was relief in his voice. "How's the missus feeling?"

The foreman did not answer at first. Slowly he pulled his gaze down from somewhere over their heads. There was a cold, arrogant look in his eyes. Gene turned rigid. Where, and on whom, had he recently seen just such a glance?

Tim Foley ordinarily spoke with a comfortable brogue, but there was no sign of it now. His English had broadened; the consonants were slurred and the vowels stressed; even those that in modern speech were considered silent. There was a strange turn of phrase and lilt of tone that brought Gene sharply forward in his seat.

"You are an impertinent knave," said Tim. "You would do well to curb your tongue in humbleness when you address me." He studied the aghast doctor a moment with cold scorn. Then he turned and swaggered arrogantly back to the silent mill.

"We-e-ell, I'll be damned!" Lesser ejaculated. "What's got into Tim?" Then his jovial face hardened and he fumbled for the latch. "If that crazy Irish galoot think's he's putting something over on me—"

Gene gripped him by the collar.

"Start the car, Doc," he whispered fiercely, "and let's get the hell away from here fast."

Lesser had forgotten about Gene's strange hallucination.

"Let me go!" he snorted. "Tim's just trying to be funny; but after I get through with him—"

"You fool!" groaned Gene. "That isn't Tim any more. That's Richard the First of England. They've started already. We're too late."

"Eh, what's that?" The doctor stopped his struggles, stared at Gene with slack mouth. "You're crazy!" But his hand trembled as it sought the ignition key. The car snapped into motion and went snarling down the road.

"I'm getting you to bed first with a good sedative," he mumbled. "Then I'll come back to talk to that hulking lummox—"

THE main street was strangely deserted. The normal number of midday cars were parked at right angles to the curb. But no one lounged on the flagstoned walks; the grain and feed store of Wait Carey, usually buzzing with the talk of a dozen farmers, was dark and empty. Tony's Diner swung agape in the breeze, vacant of laughter and the odorous tang of frying hamburgers; even the usual complement of prowling cats and lazy, ear-twitching dogs had vanished.

"Where the hell's everybody?" demanded Lesser. The piston-explosions of the Ford echoed down the empty street. The sweat beaded on his forehead; the knuckles on the steering wheel were white with strain. "Ah, there's Josh Wiley. I'll bank on his normality. He's too dumb to go haywire like you highstrung chaps. Hi, Josh!"

The storekeeper was coming purposefully down the wooden steps of his establishment. His slouching lankness was a little more erect than ordinary, the skin tight on bony forehead. He stopped short at the hail, then came slowly over to the curb where Doc Lesser had swung his car.

He disregarded Lesser. He stared at Gene with curiously penetrative eyes. He seemed strangely transfigured. There was authority in his bearing; a leaping intelligence in the bony contours of his face.

"Young man," he greeted, "you eluded us once, much to the hurt of gentle Will, who thought he found in you a fellow fashioner of idle plays. I place no such store on the outward form. It is but a machine to be used as we may direct. But since friend Shakespeare still seeks the fleshly tenement of your body—

This time Doc Lesser required no prompting. The ancient car catapulted forward with a jerk that almost ripped the engine apart.

"That," husked Gene, "was Sir Francis Bacon. He found the way to lead them back to earth. Now do you believe?"

"Crazy! Crazy as loons, all of you!" But there was no conviction in Lesser's voice. His ruddy cheeks were pale as though he had seen a ghost.

The short hairs at the nape of Gene's neck began to bristle. His flesh ridged and became hard. A little breeze stirred across his body. He was shivering violently.

"Stop the car, Doc," he chattered. "There's some one in here with us."

Lesser jammed on the brakes. "Now look here," he started angrily. "This nonsense has gone far enough. Get out of here and—"

The breeze became a wind; it whirled and coagulated into formless darkness.

Gene struck out desperately with his fists. He heard Lesser's grunt of pain. The palpable mist folded around him. Something was seeking entrance. Muscles corded, lungs exploding with withheld breath, he fought back against the unseen presence. The blackness thickened.

"Good Lord, Gene!" Lesser cried. "What's happened?" Then he gave a grunt and was still.

Gene's knuckles cracked sharply against the windshield. He gritted his teeth with a Sob and shoved every ounce of his will into the battle against the clinging mist.

"No! No!" his mind shrieked its negation. His pores oozed sweat with the fury of the invisible conflict; every muscle strained in repulsion against the invader.

SUDDENLY the weight was lifted.

The strange shadow-stuff seemed to ebb away from him. Darkness gave way to sunlight. The narrow confines of the Ford, the long, deserted street, the line of stores and garages, recovered recognizable outlines. Gene's breath exhaled in a shuddering sob. He sank limply back into the seat. His body had no strength; his mind was drained of all reserves. But a queer exultation upheld him. He had won! He had repelled the questing spirit of the mighty Shakespeare himself. He had kept his integrity in the face of the strangest invasion ever attempted against mortal man. And since he had succeeded, that meant that the eight who had returned were not as powerful as he had feared. In that case—

The Ford was going again. In the overwhelming absorption of his struggle he had not felt the initial jerk. Weak and still shaken, he turned to his companion.

"You sure kept your head, Doc," he said approvingly. "I thought you'd be scared to death. Let's get out of Stonehill as fast as we can. After what just happened—"

Lesser's face seemed curiously in a shadow. His little goatee had stopped its usual wagging. He began to chuckle, melodiously, softly.

Gene peered at him quickly. Something was wrong. That was not the genial Doc's ordinary laughter. If, in fact, there was anything to laugh at just now.

"Now, lad," said the man at the wheel, swinging into College Boulevard that led to the broad campus of Stonehill College, "don't thee bother thy weary pate about the destination of this monstrous chariot. As for fear, the ruddy particles that once were wont to visit my heart had never known the meaning of that term."

"Have you gone crazy, Doc?" Gene demanded. "Or is it a joke? If it is, this is no time for it. The world's about to go to pot, and you spout a wretched combination of what you think is Elizabethan English and an Irish brogue that Tim himself would have been ashamed of. Snap out of it and get back on the main highway again. We've got to seek help."

Lesser jerked around angrily. The car almost climbed up the curb as he did.

"Careful, lad, with your tongue," he warned. "How dare you compare the purity of my English speech with the thick jargon of Irish trotters of the bogs? I had been unduly courteous with you, though the harsh, clipped syllables to which you have perverted our noble tongue has ere this offended mine ear. Peace, and you would not offend me to your own hurt."

Hot retort was on Gene's tongue, and died into a little gurgle of sound. He had seen Lesser full-face, and he had remembered something. The jovial doctor's features were subtly changed. His grizzled beard had a tinge of ruddier color. The contours of his cheeks had shaped themselves into a narrower mold. His eyes gleamed half with anger, half with speculative amusement. And Gene remembered. Back in college a lecturer on the Elizabethan age had told them: the lines of Shakespeare, delivered at the Globe, would sound to modern ears like a travesty of the speech of County Cork. Shakespeare!

GENE shrank away with a startled gasp. His hand reached behind him for the lever that opened the door. A sudden twist, and he would catapult from the speeding Ford to the road. He'd rather take his chance on a lamed foot or a broken arm than remain a captive to this thing of dread who had taken on poor Lesser's physical body.

"Stay where you are," said Shakespeare quietly.

Gene's fingers froze on the lever. They seemed paralyzed into inaction. He could not move a single muscle.

"That is better, my young friend," Shakespeare approved with a soft chuckle. "I would not do you hurt wittingly. For, after all, you too have fashioned from the vasty depths the forms of human beings all compact, and strutted them across the well-lit stage for fools to gape at. I would not say you have done it properly, but then that is the fault of your age, not yours. The dull ears of the groundlings must be tickled with duller prose; they would not understand the surge and thunder of my verse, nor the sweep of Kit Marlowe's mighty line. Poor Kit! I never found him in my spacious wanderings. He owed me a stoop of sack on a wager I had won. There was a certain wench—"

"What are you going to do with me?" Gene asked, prying his stiffened lips open with a desperate effort.

Shakespeare looked at him and laughed.

"Nothing, lad," he answered in kindly fashion. "I said I liked you. I had thought to clothe my incorporeal spirit in your lithe flesh, but then I saw the ruddy features and wagging beard of the man of medicine." He stroked the pointed beard with much satisfaction. "I had been lost without this silken texture on my face. I find the juices of my mind flow more freely when I caress it with gentle fingers."

"Then let me go."

"Nay, lad, that I cannot. You have seen our company entire; you know us in the parts we have adopted to strut the stage of this your life. Until our plans are fully laid, you must go along with us. You shall not suffer, that I warrant you."

The Ford lurched into the shade-bordered street where the faculty houses stood in a modest row. Shakespeare screwed up his face.

"How stop you this earth-shaking steed, lad? It goeth of itself, with much muttering, but it doth not cease when I command."

Gene reached over, turned off the ignition, pulled the hand brake. The car groaned to a jerking halt in front of the house of Dr. George Alsop, who taught philosophy at Stonehill. Shakespeare breathed a sigh of relief.

"I leave these iron monsters to Sir Francis, who hath a way with them. Hereafter I ride only the good steed Pegasus." He leaped from the car, beckoned to Gene. "Come!"

Something tugged at Gene's mind and also at the muscles of his body. Without volition of his own he followed the bard of Avon into the neat little frame house in which George Alsop lived a bachelor life.

Inside the living room two figures rose. A dry voice greeted them. "It is time you came, Will. But where is Sir Francis? I expected a little woolgathering from a romantic poet; but not from one who pretends to be a scientist."

"Glenda!" Gene cried out terribly, and leaped toward the girl who had just spoken with the dry, sharp voice of Voltaire.

SOMETHING seemed to stop him in mid-rush, and bring his quivering body to an abrupt halt. Glenda Gordon looked at him quizzically. She was a slim wisp of a girl, with curly brown hair and glinting gray eyes. Her features had been subtly curved and mobile; but now something strange informed them, and brought ironic intelligence to her eyes and a sharp, caustic expression of disdainful mockery to her lips.

She shook her head.

"Behold, it is the young man again who came to us on the hill. He refuses to stay out of our path. Can it be he affects the tender passion for the young lady whose form I have taken?"

The other figure moved into the light. George Alsop was a big, placid man with sandy eyebrows and a rather baldish head. His clothes were always baggy, and his tie invariably askew. He too had changed. His face had broadened slightly, his nostrils tilted with an inquiring gesture, and a strange, transfigured ugliness gave him a goatish appearance. Even such had Socrates shown the night before on the hilltop.

"It is Shakespeare's fault, and the fault of the romantic poets of his trade," he murmured. "After all, what is love between man and woman? A subordinate urge for procreation that has nothing to do with the mind, or with the great inquiries of philosophy. But the silly poets have glorified it—"

"Spare me your preachments, my Socrates," Shakespeare interrupted. "Meseems my poet's frenzy is more practical than your eternal prating after truth. While we stand here and dally with words, I doubt not that our warrior friends are even now in motion."

"The warriors think always with their feet," grinned Voltaire. "They march, while we but talk. But somehow, our idle words get wings and speed before to win the victory. Now if the venerable Bacon were come—"

Socrates turned to the door.

"This time the poet is right and the sceptic has erred. Look down that tree-shaded vista. Here come the men of blood and iron with recruits whom they gathered on the way."

Somehow Gene managed to turn his head. Slowly the use of his limbs was returning. And with it, came despair and a strange helplessness. Glenda stood before him in the flesh, but she was a stranger. So was Alsop; so were these other men whom he had known these past five years.

And now, coming down the street, marching with soldierly tread, was a solid phalanx.

THE forefront were four men. Tim Foley transformed into Richard the Lion-Hearted, Rufe Greene, the good-looking young clerk in Henkel's drug store, metamorphized into the god-like Alexander. Harvey Wiggs, the lawyer, whom the judges of the County Court held contemptuous of their dignity, and subtly changed his cynical arrogance into the very mold of Julius Caesar. And a little to one side, half aloof from the others, strode a little, fat-bellied man. Lucius Halliday taught mathematics in the high school, but his passion was chess. He played it as a general plans his campaign. Every pawn was a regiment sent into battle; every castle was a fortress well-taken. No wonder that Napoleon Bonaparte found congenial entrance into his body.

Behind them came men of Stonehill, moving in grim silence, faces blank with outward compulsion. The hulking mill crew; brawny farmers and workers from the factory. Simple, sturdy folk whom Gene had known for years; solid New Englanders whose speech was chary and who believed only what they saw and not much of that.

Shakespeare frowned.

"They have stolen a march. But no matter, when Sir Francis comes, we shall gain our own cohorts."

A long, lank figure moved around the corner of the house, swung his bony legs up the porch.

"I hear my name," said Josh Wiley.

"I was only a little delayed."

"A man of science should not suffer delay," Voltaire retorted. "Does the sun delay in the sky; or earth in its diurnal rotation?"

The marching men came to a halt in front of Alsop's house. The four in front wheeled and came directly up the path, and through the open door into room. The troop that had followed stood in the street, at attention, immovable, with expressionless faces.

Socrates met them with gentle reproof.

"This was not in our plan. Was it not agreed that we should first take counsel after we clothed ourselves in earthly bodies?"

Richard thrust back his red-thatched head and roared.

"Counsel? Talk is for women. A man strikes first, and thinks, if think he must, when he is old and full of rheums."

Julius Caesar smiled a superior grin.

"Richard of England puts it a bit baldly. I have ever found that a sudden march is worth ten deliberations in a tent."

"Had I listened to such as you, Socrates," cried Alexander, "I would have remained in Macedonia and died a petty king."

Napoleon turned his dark, inscrutable eyes upon his fellows. A strange smile wove over his dark features; but he said nothing. To Gene, sick with a feeling of utter impotence in their presence, seemingly unnoted by the rest, it appeared that this sudden foray by the four generals was not a rash impulse, but a crafty, carefully considered piece of strategy on Napoleon's part.

Something snapped in him. Perhaps it was their inattention that released him partly from their grip; perhaps it was the impact of his straining will.

"NOW look here," he interposed suddenly, with bold determination. "You do not know what you are about. You are trying to conquer a world that belongs to the living, simply because you are tired of the infinity in which your restless spirits have wandered. But that is impossible. You are flying in the face of natural laws. It is true that you have managed to dispossess the living from the bodies you have seized; you may even succeed temporarily in your mad scheme. But sooner or later the immutable laws of the universe will defeat you. Don't you understand? You have died in obedience to an inexorable plan. You did your work, and yielded up your places to others. You cannot return."

He turned to the form of Glenda with an appealing gesture. Perhaps her spirit, submerged under the acid mockery of Voltaire, might rise to his plea and cast out the invader.

But the girl only nodded approvingly.

"An excellent analysis," she replied, "even though the premises are false. Our four friends, the men of arms, naturally would not understand. They never were very good on logic. But those on the intellectual side, I doubt not, have followed your statement closely. Nevertheless, as I have said, your premises are false. There are no such immutable laws as you suppose. I had my doubts about them in life; after my wanderings in the interstices of time and space, my doubts became convictions.

"There are no laws that the power of disembodied thought cannot amend. Ideas, as Socrates will tell you, are the only immortality. All else is pure illusion and show. The living are but the molds of our former thoughts. You are responsive to our influence; we shaped the courses your lives must follow. Isn't that your modern doctrine of heredity?"

"Yes, but—" Gene stared.

She waved a slender hand.

"Don't interrupt, young man," she said with quiet laughter. "That was but a rhetorical question, requiring no answer. As long as you followed our paths, I at least was content in my limbo. I never thought to interfere, nor did my friends; though I confess Alexander was always moaning about the new worlds he had failed to conquer in life, simply because he had not known of their existence.

"But now, your world of living has cut loose from the past. Madness has taken the place of reason; vicious cruelty has supplanted kindliness, hate tolerance, and bestial passions the loftiness of the soul. It is time to call a halt. If we do not intervene, earth will perish in a sputter of flame and horror; mankind will be wiped clean."

"That is true," Shakespeare agreed. "Yet there is a more selfish reason for our conduct. We stay on only long as our thoughts, our ideas, inhere in the hearts and memories of the living. Once those memories are erased, once there are no longer men and women to cherish them in their bosoms, we vanish into echoing nothingness."

"There are many such," Bacon said somberly. "I saw them drift into smoke in that void from which we came. Brains as mighty as any of us; men of Ur and Chaldee and of Knossos. You no longer remember them; and they went." Then his dark eyes flashed. "But that didn't matter. I never cared much for personal immortality. It was the race that mattered. Once I wrote a little thing I called Atlantis. I thought to shadow forth the future of this earth. I find I was mistaken. So I have returned to set the times aright."

RICHARD started up.

"Words!" he shouted wrathfully. "All words! A buffet on the head is worth a million of them. Why don't we start?"

"Stick to your buffets then, and do not talk," Napoleon said dryly. "We'll call on you fast enough when they are needed. I told you I would plan our strategy." His sunken eyes stared at the others. "Four of us are soldiers; four are men of thought. Now mind you, I have a high regard for ideas—when they are linked with action. But too often the processes of thought cripple action." He clapped Shakespeare in friendly fashion on the back. "I think you once remarked on that in a play called—let me see—what was its name?"

"Hamlet," said Shakespeare, offended.

"Of course! It slipped my mind. We have reached an impasse. You seek to remodel this world to your Utopian desires by sweet reason and exhortations."

Caesar smiled sarcastically.

"I should have tried my poets on Vercingetorix and the Teuton hordes. It would have proved a pleasant sight."

"Exactly," Napoleon agreed. "We soldiers are first and last realists. Men do not follow ideas; they follow force. If we are to gain control of the living, we must do it by showing ourselves the stronger. We have not spent our time in eternity in vain." He waved his short, plump hand toward the street. "Those are the first fruits. Their minds are tuned to ours. They will follow us to the death, because we deftly planted certain slogans in their brains. They are no longer men; they are soldiers submissive to our will."

Socrates went to the door; looked out; and returned. A sceptical smile wreathed his ugly countenance.

"You have picked your subjects with practiced skill," he observed gently.

"They are men of muscle; diggers of the soil, artisans of the mill; men unaccustomed to the shining weapons of the mind. No wonder they follow you to the wars like dogs after their master."

"All men are like that," asserted Alexander. "Philosophers are few; the men of brutish instinct many."

Socrates shook his head.

"Nay, that is no longer so. Truth must have slowly made its way during the centuries. In the days when I paced the tree-lined walks of Athens with Plato and a few precious disciples, you may have been right. We were then a slim handful in a world of blood and deeds. But today, look around you. We have returned to a land where education and the things of the spirit are universal. I myself am clad in the form of a living man who taught philosophy, not to twos and threes, as I was won't to do; but to hundreds and hundreds. Every hamlet has its school; every town its university. There is peace and plenty."

NAPOLEON frowned.

"I wondered why we came back to America. None of us belong here. In Europe, where was once our home, there is no such peace or plenty."

"I had method in my madness," Bacon said. "I realized before I opened the path that we would disagree. In Europe there was too much timber for your fire. Here in America we have more chance to prove our point." He smiled shrewdly. "That in itself is but an instance of the superiority of thought to force."

"Hmmm!" Napoleon seemed wrapped in thought. Then he spoke with a frank, open countenance. "Perhaps you are right. If you are, I am willing to yield, and follow you on the way to Utopia." To Gene it appeared that he was sneering. "I have a sporting proposition to make to you."

Voltaire looked distrustful.

"Beware Napoleon when he bears gifts," he murmured.

"There are no catches. You yourselves will be the judges. Here in this little American town into which Bacon was good enough to dump us there is a university. Socrates has just expatiated on the blessings of culture. He has actually found the form of a philosopher to wrap around him. There are hundreds of students within these tree-lined walks; dozens of professional promulgators of the uses of thought. Here, if anywhere, are there living subjects fit for your plans. Certainly these ardent searchers after truth must bow before your superior wisdom, and swear to follow you to the intellectual ends of the earth. Certainly they have nothing but contempt for crude violence, for the compulsion of man's free spirit. Certainly they would cry us out of their councils."

Glenda reached in a non-existent pocket for a non-existent pinch of snuff. Her lovely face screwed up in sharp, suspicious lines.

"He protests too much," she shook her head. "I mislike it."

"Commend your proposition to our ears," Shakespeare demanded.

Napoleon looked slowly around the circle. Gene strained to listen. Somehow he knew that the crafty Corsican was fixing up a scheme.

"It is quite simple," he said. "Let us all appear among these students. Let us state our respective cases to them. Choose you among yourselves your most persuasive speaker. We shall do the same. We agree in advance to exercise no compulsion such as inheres to us from our stay across the border. If the students hearken to you, we yield the earth to you. If they follow us, then we take over. Is it a bargain?"

"It's a trap," Gene burst out. "Don't listen to his smooth plans. I saw him wink before to Caesar. When he was alive, he gained as much with plottings as on the field of battle."

"Why do we permit this paltry human to be present at our councils?" Napoleon's dark face suffused with anger. "Richard! This is your task." The giant Tim Foley clenched a huge fist; lurched forward.

"This is better," he growled. "I am tired of palaver. When he but feels the weight of my hand—"

Shakespeare interposed himself deftly.

"Keep your massive brawn to yourself, friend Richard," he said. "He is a likely lad; one of my own craft. Had he a beard, I would have been one with him, instead of this paunchy doctor who resembles Falstaff more than myself. Beshrew me if I do not admire his independent spirit, even to our very fronts. He shall come to no harm, do you hear?"

The luster died from Richard's eye. "Have your way, Will," he muttered, discomfited. "I never was one to bandy words with you. Yet I would have felt better if I could have knocked him down."

ANGER flared through Gene at his words. He forgot where he was, and the strange company he was in.

"You had better keep a civil tongue in your head, Tim Foley, or Richard, or whoever the devil you are," he exploded. "Big as you are, don't try to start anything."

But no one seemed to pay any attention now to the solitary mortal in their midst. Bacon brushed him back with an annoyed gesture as though he were a troublesome insect; then turned his somber eyes on Napoleon.

"We accept your challenge, Napoleon," he said quietly.

The Emperor nodded. His dark face displayed no emotion.

"Very good. Let Socrates, in the form of Dr. George Alsop, member of the Faculty, arrange the meeting."

Gene felt himself caught up in their swift procession to the door. His outburst had drained him of human emotion. He was only a helpless pawn in the game that these immortals were playing against each other; suffered to remain a witness merely through the fleeting kindliness of Shakespeare for a fellow craftsman.

In the wide, shaded street a commotion had arisen. The group of men who had followed the compulsion of the conquerors stood stolidly as they had been left. They neither spoke to each other nor looked to the right or left. They seemed like robots that had run down and awaited the electric spark of their masters.

But from the direction of the College young men were running. The last reverberation of the chapel bell was swinging away on the air. It was two: forty-five, the last regular class for the day.

Fresh, clean-cut young fellows, wholesome with health and alert intelligence upon their faces. The College standards were high, and the student body was picked with great care.

In seconds the strangely immobile group was surrounded by a jostling, curious horde.

"What's the parade about?" yelled a Freshman.

"Can't you fellows talk?"

"Speak up! What do you want on our grounds?"

But no one answered. Not a single mill-hand turned his blank stare on the growing mob. Questions gave way to jeers; jeers to catcalls. A big football player growled:

"All right, fellows. They're trying to be funny. Let's get them off the grounds, and back where they belong."

There was a concerted rush.

Richard the First lifted his voice in a huge, joyous shout. The red hair of Tim Foley seemed to bristle; battle lust inflamed his eyes.

"At them, men," he yelled. "For God and St. George!"

His thundering tones seemed to release a spring. The brawny workers and farmers awoke to sudden life. They wheeled in a disciplined mass and met the disordered rush of students with swift charge and methodically flailing fists. They fought like machines rather than like men.

There was something terrifying to Gene in the way they surged forward, resistless, heads low, slugging with either hand. He tried to fling off the porch to stop the madness, but iron bands seemed to constrain his muscles and hold him helpless.

Fuming, furious, he saw with terrible clarity what the victory of the returned conquerors would mean. Mass hypnosis, robot-like followers sweeping the world with irresistible efficiency, compelling all mankind to the dictatorial will of these four who even in death had not lost the lust for domination.

THE college men, taken unaware by the strange fury of the attack, fought gallantly but futilely. Their ranks scattered, a dozen went down under piston-like fists; and the rest broke and fled toward the campus.

Richard rubbed his hands gleefully.

"Methinks my own Crusaders could not have done better than these strong villains. It was, fair sirs, such a sight as I had ne'er expected to see again."

"And you won't any more," Napoleon turned on him, black as thunder.

"You're a ninny. You may have the heart of a lion, Richard, but your brain is that of an ass."

The big man looked hurt.

"What have I done wrong, Napoleon?"

"Everything," Caesar spoke up. "What good is it for Napoleon to lay his careful strategy and for myself to plan swift, crushing attacks in overwhelming force when you start some silly child's play that may spoil everything. Even Alexander would have more sense than that."

The Greek started.

"Now look here, Caesar," he declared heatedly. "I didn't need ten Roman legions to overawe a single wretched tribe. My victories were always over overwhelming odds."

"Stop it!" Napoleon raised stentorian voice. "You're quarreling like a pack of fools. Haven't the centuries taught you wisdom? Look at Socrates watching us with placid benevolence; and Voltaire grinning as though to egg us on. If we divide, they win; don't you understand?"

Caesar subsided.

"You're right," he said sulkily. "Yet Alexander shouldn't say things like that about me. He knows they're not true." Shakespeare hummed a little tune. "Mortal or immortal; the tongues of men beshrew their minds," he sang. Bacon looked grim.

"Enough of idle chatter. We have made a bargain and it must be kept. Socrates, do you proceed with the plan we laid before this business of fists and brawls. King Richard, do you march your men in here for hiding until the thing be settled."

They worked fast then, and with a will. Gene, still locked in that strange compulsion of his limbs, though his mind was free, could only watch and seek feverishly some avenue of escape.

Once he begged Glenda, as she passed, to let him go; but the spirit of Voltaire peeped mockingly out of her eyes.

"You are but an oaf," he grinned, "to wish to leave our presence. Where else could you observe so well the fact that, alive or dead, simple as good Richard or wise as Socrates, the race of man pollutes the universe." Then she passed on.

Shakespeare brushed his fervent plea aside.

"Thou art an ungrateful wretch," he frowned, intent on other things. "Would you follow the men of arms rather than the men of wisdom? Go to, or I shall repent my kindness."

Socrates, in the shape of Alsop, had gone ahead. With him went Glenda. By the time the mill-hands had been herded in the house, and the others had strolled like any group of casual visitors down to the campus, past the gray-stone buildings to the chapel, the college had been assembled for their coming.

HOW Alsop had accomplished it, Gene was never to know. What manner of persuasion was employed neither he, nor those who obeyed his will, could remember in the slightest after the event.

But when they appeared on the platform, a sea of faces stretched before them. The front benches were filled with the members of the Faculty, headed by the full-faced, white-bearded Dr. Hutchinson, President of the College. Behind them sat the entire student body, from the youngest freshman to the most dignified senior. No one had escaped the net.

They stared curiously at the cluster of men and the single girl who had taken their places on the platform. Not a sound escaped their lips. An uncanny silence hovered over all. Warm red light, religiously subdued, streamed through the stained-glass windows from the westering sun, and cast an eerie glow upon their faces. Their minds seemed free, yet strangely constrained to listen without surprise. Even as Gene's own mind had been from that first meeting on top of the hill, now so curiously remote.

Dr. George Alsop faced them first. They knew him, yet somehow they knew as well that he was Socrates, come from the wastes of time to talk to them. The goatish expression that had overlaid his face consorted oddly with his big, loose frame and baggy clothes. The hush deepened.

"In Athens," he said, "I had but a mere dozen disciples, gathered together to examine life and beauty and truth. The rest ran after the sophist Protagoras and his kind, or wasted their days in pleasures. Now, in this place, more than half a thousand pursue the ways of reason; yet you are only a company of those who, all over earth, hunger for knowledge and the life of the mind."

Bacon nodded sagely; but Glenda, Gene noticed, looked satiric.

"I died," continued Socrates, "as all men must. Yet I did not die. Even in life I knew that thought was eternal. In the universe of Ideas I met kindred spirits; those who had gone before and those who came afterward. I also met those who had differed on earth and remained unchanged in infinity. What we were in the flesh, we were as disembodied thought."

Caesar nudged Alexander and whispered something in his ear. The Greek smiled for the first time since Gene had met him.

"We watched the earth," the philosopher went on. "We saw birth, life and passing death. We observed wars and famines and the steady growth of knowledge. When Francis Bacon joined our ranks, he spoke of an ideal commonwealth soon to come. When Shakespeare drifted in our midst, we knew that the sweet uses of poetry had found their supreme master. With Voltaire came that skeptical disillusion which is the mark of civilized intellect. There were others who followed—each with the report of new conquests of the mind—each optimistic of the steady growth of truth."

Richard shifted his huge body and looked sulky. His name had not been mentioned. But Napoleon sat inscrutable, surveying the chapel with dark, emotionless eyes.

SOCRATES leaned forward, and an urgency came into his tones.

"But things soon changed. War and slaughter swept the fair earth, on a scale far beyond the bloodlettings even of my friend, Bonaparte. Insane hatreds blossomed like rank weeds, choked off all tolerance and truth. The contagion spread; is spreading now even faster. Unless it is stopped, this earth which is ours as well as yours; for which we lived and died, will revert to the brute and leave us vanish into the limbo of forgotten things. For we exist only as long as our memories are green in the minds of those who are our inheritors.

"Some few of us decided this must not be. Bacon pondered the problem and resolved the answer. We returned."

He glanced sadly at the four conquerors.

"We made a mistake," he avowed. "We brought back with us those who tried on a limited scale during life what the madmen who rule your world today are doing in whirlwinds of blood and tears. Therefore we must seek your aid in what we intend. I am Socrates, the humblest seeker after truth. You may have half-forgotten me. But here are Francis Bacon, who took all knowledge for his province, Shakespeare, the loftiest spirit of any age, and Voltaire, whose keen wit and healthy laughter swept away the accumulated frauds of centuries. It is fitting that he appear before you in the fresh young garb of a girl. His is an ageless spirit.

"Follow them, I beg you; and the world is yours to remake and reshape to your hearts' desire. You, the inheritors of their mighty brains, the students of their lustrous wisdom, are their disciples. It is a Crusade—not such a Crusade as Richard blunderingly followed—but a shining adventure after an ordered commonwealth of earth, with tolerance, learning, wisdom and graciousness the four pillars of support; a world where philosophers will be kings, and kings philosophers."

He stopped abruptly, and Gene, listening with thudding heart and shining eyes, felt a great surge within him. His doubts were resolved, his fears for the incalculable disruption that this return of the ancient spirits might bring. Socrates was right. They had found the solution to the ills of the world. No one who valued the things of the mind, who had ever received in the slightest the illumination of their thoughts, could resist their bright appeal. Surety these young men and old, nurtured in an atmosphere of the intellect, must rise as one to thunder their approval.

He glanced down at the seated figures. Something stirred—something moved over their faces. Their frozen features relaxed, they turned to look at each other, seeking confirmation in their fellows of what they dimly felt in the recesses of their own minds. Gene jumped impetuously to his feet. It needed only the exhortation of one of their own kind to stir them.

"LOOK at me, men of Stonehill," he cried out. "I am Eugene Westcott, a living, breathing human being such as yourselves. Up till now I was afraid of these beings from the dead, but now I am convinced that Socrates and his companions can make the world a better place. Join them; follow them to the ends of the earth. But beware of Napoleon, of Caesar and Alexander, of Richard the Lion-Hearted. They would lead you to the conquests they had left unfinished while alive; they will cheat you—"

Glenda put a firm, slim hand on the excited dramatist, tugged him back to his seat just as Richard started up with a crash that flung his chair across the platform.

"You fool!" she whispered—or rather Voltaire did, "they'll eliminate you as easily as though you were a crawling insect. Do not interfere if you value your life."

Napoleon said quietly.

"Sit down, Richard." The big, redheaded foreman hesitated, growled, and picked up his chair. Napoleon got up slowly. Most of the faculty and many of the students of Stonehill College knew Lucius Halliday. As teacher in the village high school he ranked comparatively low; certainty not as high as Alsop, who had just finished speaking.

He was under average height, and his paunch made him look even shorter. His sallow skin and lank black hair resembled slightly the texture of the Emperor of the French. His sunken eyes helped the illusion. But, staring at him, held by that strange physical compulsion which nevertheless left their minds unhampered, the students knew that it was Napoleon Bonaparte who stood before them, even as it had been Socrates a minute before. The stir subsided; the blankness of their faces shifted into position like masks.

Napoleon looked down upon them.

His pudgy hand crept up into his vest in a studied, well-remembered gesture. He smiled.

"My children," he said, "Socrates has made a speech. I do not intend to do so. He was always a well-meaning sort of a fellow, but curiously muddled, the same as all theorists. He has his place, and so have Shakespeare and the rest of them. But when this world of ours ever wanted anything done, it called on us, the plain men, the doers, the soldiers. Aristotle and Socrates talked Greek culture, but it was my friend, the great Alexander, who spread that culture over the world. Virgil wrote his nice little poems, but it was the mighty Caesar who built Rome so that it endured for four hundred years. The medieval philosophers disputed about how many angels could dance on the head of a pin, but it was Richard, well-named the Lion-Hearted, who overcame the infidel and saved civilization."

Richard grinned self-consciously at this slightly inaccurate description of his conquests.

"As for myself," said the wily Napoleon, "it doesn't become me to talk. But let me ask my friend, Voltaire—he whose spirit of eternal mockery is aptly clad in the lovely garments of a girl—who was it that did more to break down the fetishes and narrow nationalisms of Europe than my humble self?"

Specious arguments, thought Gene; yet subtly plausible. Of course, if one tried to analyze...

"TODAY you are confronted with a situation," the Corsican went on conversationally. "I agree with friend Socrates. Madmen are in control. Men who aren't fit to shine the shoes of such a man as Caesar." He turned with an enigmatic smile to the four silent exponents of the intellect. "Not even of these worthy people. But they have the power. They tell you what to do; what to think as well. How did they get this power? By force; by the weight of arms, or the threat of them.

"Where are your so-called philosophers today? You have them. Perhaps not as splendid as Socrates and Voltaire and Bacon and Shakespeare; but good enough in their way. Let me see. I think I know some of their names. Einstein, Thomas Mann, Wells, Millikan, Rolland, Santayana—why, you have any number of them! But what have they done?

"Talked, wrote, waged war with words." He was openly contemptuous now. "The result? Nothing. Those who aren't in exile or fleeing for their lives will soon be. Words are all right in their place, but not against machine guns and bombs and raiding planes. You need to fight fire with fire."

His voice raised gradually until it was a thunder of sound. His eyes flamed. His sallow countenance became transfigured. "Fire with fire!" he repeated. "We are four doers. We showed when we lived what we could do. We can sweep these puny upstarts from the earth in a single campaign. Are you men or are you women like Voltaire? Will you follow the talkers or the doers? If you wish to save civilization, to unite all earth in a single mighty state, follow us. In thunder and in smoke, in battle flame and in the clash of arms, we, the soldiers, shall conquer for you. Arouse, my children! Strike now, while it is yet time! Strike for victory!"

His arms spread suddenly wide in a superb gesture.

At once the chapel was in pandemonium. Students and Faculty alike jumped from their seats, cheered, shouted, stamped and whistled. The venerable President danced in the aisles like a madman, his white hair disheveled, screaming, "Victory!" over and over again.

On all their faces a single emotion showed. A mob emotion. They clenched their fists and shook them in the air. A measured chant rose from their lips, grew in volume until it shook the building.

"Victory! Victory! Lead us to victory!"

SOMETHING snapped in Gene. He had listened to Napoleon in enforced silence. He had been confident of the outcome. Surely this picked group of civilized human beings would not hesitate. They had been taught to reverence men like Bacon and Shakespeare; they had studied in their histories the splendid lies of the conquerors and detected the miseries that lay underneath. They were trained to dissociate reason from emotion, logic from oratory.

Yet as the Corsican builded up, Gene felt uneasy. He caught the rapt gleam in the eyes of the auditors; he felt something stir in his own blood and make his breath come in short, quick gasps. After all, wasn't it true? Words hadn't stopped the dictators. Force was the only thing they respected. Very well, then, meet force with force. Fire with fire. A very good phrase. This was a job for men of action. Kill, slay, wipe them out! His breathing grew shallower and faster. It fell into a rhythm with the concerted breathing of half a thousand others. Napoleon's words swayed and danced in his ears, beating out the time.

Victory! Strike for victory!

The thrilling phrases exploded like a bomb in his mind. He jumped up with the others. He screamed and pounded in unison with them.

"Lead us to victory!" he chanted.

"Mes enfants!" thundered Napoleon.

"Follow me; follow Caesar and Alexander and Richard! We go to conquer the world."

He was no longer a short, fat man. He had swollen to gigantic-seeming proportions. He stalked off the platform, marched down the central aisle. Caesar, smiling with inner thought, was at his side. Alexander, impetuous and fiery, trod on their heels. Richard lumbered after, bewildered, but caught up in the current of his leader's speech.

"God and St. George!" His bull voice outdistanced them all.

Behind them, tumbling, jostling, eager to be the first, swept the mob of students and instructors. On their uplifted faces and in their furious eyes was stamped indelibly the lust for battle, for blood and carnage and glory. The gentle little Professor of Aesthetics shoved against the captain of the football team; the Professor of Greek straightarmed the Associate in History out of his way.

Out through the door they went, their shouts resounding across the spacious campus. Not a one remained behind.

No one, that is, except four rigid, silent figures on the platform. Socrates and Bacon and Shakespeare and Voltaire. Four of the mightiest spirits that had ever lived; the precious heritages of the realm of thought. Four, and a single human being to keep them unwilling company.

GENE WESTCOTT had started up with the rest. In a blaze of emotion he tried to follow as the captains marched through the chapel.

But a soft, white hand laid gently on his arm. He threw it off impatiently; then a tiny sliver of sanity caused him to turn. His blurred eyes beheld Glenda; his overheated brain felt the small, cool words drop into it like tiny pebbles.

Somehow the satiric mockery was gone from her eyes; the Strange quirk that twisted her lips. This was Glenda Gordon, a human being like himself. He had sat with her, and dined with her, and taken long, magical rambles. He had loved her!

"Gene!" said Glenda softly. "Do not follow the mob. Remain with us; with me." Her full lips quivered. "Voltaire is saddened by this sight. Yet he had not expected anything else from the race of humans. He will depart soon with the others. I shall be free. But if you join the shouting mob, then nothing will matter—for me."

Gene stared at the girl. Martial music throbbed in his ears; his veins raced with the sound of slogans. But slowly the delirium dropped from him. His pounding blood slowed; his brain gradually cleared.

"Good God!" he groaned. "What was I about to do?"

Voltaire peeped once more from Glenda's eyes. They were half-mocking, half sad.

"What everyone else has done," he observed. "I for one should have known better; if the others did not. Man is still an animal, subject to emotions rather than the cool breath of reason. Earth is not worth saving."

Bacon got to his feet. He seemed tired.

"It never was," he said. "We have failed. We were poor fools who meditated in the infinite void." He smiled mirthlessly. "We always meditated in a void. We forgot what happened to us when we were alive. We thought mankind was ripe for our return. We have learned our lesson."

"A lesson we should have conned before we started," said Voltaire, the irrepressible. "There is more of irony in it than I ever dared put into the covers of Candide. In this best of all possible worlds not even a single human being succumbed to the irresistible compulsions of truth, of beauty, of the sublimities of philosophy." He looked maliciously at Gene, who reddened. "Not even our young dramatist whom Shakespeare favored. He too wished to follow the captains of war, the apostles of force, the exponents of blood and iron."

"We weren't free to choose," Gene answered weakly.

Socrates sat where he was, his eyes filled with infinite melancholy.

"The soul of man is always free," he declared. "The seeming compulsions that we, timeless in our death, had laid upon you were but the outer representations of your inner, hidden selves. You yielded to that which best expressed your desires." He smiled ruefully. "We, who called ourselves philosophers, poets, scientists, considered that you were ripe, after centuries of sowing, for the harvest of wisdom and truth. We find instead that man's nature has not changed since Alexander and before."

GENE turned his head away in shame. He was as guilty as the rest. Long shadows slanted across the chapel. The light that filtered through the stained medallions was dimly red. Outside, dusk was falling. Silence reigned again. The captains and the shouting had departed, seeking new fields, new hordes to lead to battle.

He had a sudden vision of innumerable towns along the way, adding their quotas to the whelming flood. Then Boston and New York, Chicago and San Francisco. Ships and planes to speed across the ocean. London, Berlin, Paris; Moscow, Tokyo, Rome. He turned back, shivering.

"They are gone!" he whispered. "You, timeless as they, have failed. We, flesh and blood, must fail as well. Neither bullets nor ideas can stop them. What shall we do?"

"We have made our bargain," said Shakespeare, stroking his beard. "They go on to triumph and the seizure of a living world. We," he grinned, "go back to the vasty deeps to meditate upon the mutability of all things."

"Once before," murmured Socrates, "I drank the hemlock. It was a bitter draught to start, but pleasant enough at the lees. I do not shrink from it now."

Gene faced them in a glow of indignation.

"I was ashamed of myself before for having yielded to Napoleon's mummery," he said steadily, "but I am no longer. I am only an ordinary human being, still alive. I haven't your genius, your marvelous intellects. Nor have I the benefit of release from the hamperings of the flesh, of century-long meditations. Yet I refuse to despair as easily as you do.