RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

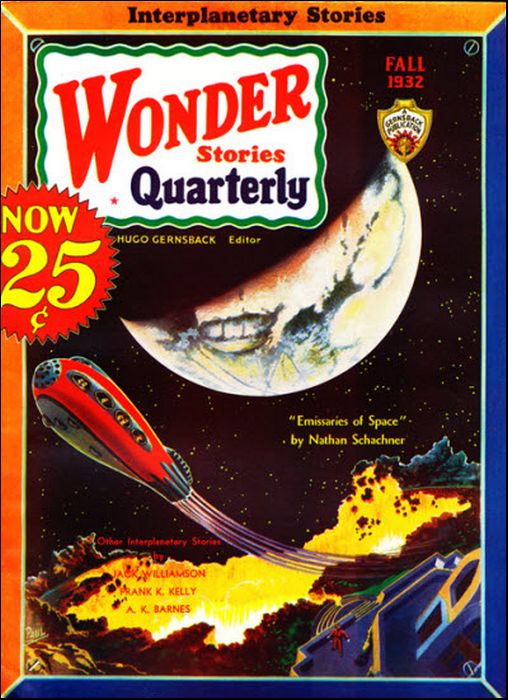

Wonder Stories Quarterly, Fall 1932, with "Emissaries of Space"

We who look calmly up at the blue of the sky, perhaps still think, as the ancients did, that we are the center of the Universe, secure in our place, and masters of the world. We still have not learned what astronomy teaches us, that we are inhabitants of a speck of cosmic dust, at the mercy of all sorts of universal influences.

But not all of these influences need necessarily be harmful; nor need we worry about an invasion of some twelve-legged, six-eyed monsters, as some writers believe. On the other hand, we earthly microbes might find ourselves made the beneficiaries of the vast knowledge of creatures beyond our knowledge or understanding. But suppose in return for that knowledge they were to demand a heavy payment. Would we make it and lose our freedom? This most unusual story, by the author of "Exiles of the Moon" answers the question in 50,000 gripping words.

JOHN BOLING, legs apart, large bony hands clasped tightly behind his back, stared out of his sixtieth story office window in the Empire State Building at the outrageous panorama of New York.

It was sundown. The sun, a molten glow behind the cliffs of Weehawken, dazzled against the westerly sides of the lean, triumphant towers of the city. Twilight had already come to the narrowed canyons a thousand feet below. The broad expanse of the Hudson purpled with dusk. The city winked suddenly into a million lights. It was the daily miracle of New York!

Boling, his massive, sculptured head pressed close to the glass of the window, was no poet, yet his deep-set eyes burned with strange lights as they fixed on the black swarms of electro-motors that crawled, bug-like, along the gorge far below. His eye swept over the sprouting towers, in which, like rocketing lights, tiny elevators accelerated upward. They turned eastward, to the giant electric generating stations that lined the East River, and then west, beyond the Hudson, to the stiff, skeleton-like transmission towers that stalked with outstretched limbs across the Jersey meadows.

A single word came to him from the metropolis, a word that grew in repetitious thunder until it surged through every quivering fiber of his body, beat in moaning crashes against his brain.

"Power!... Power!... POWER!"

He thrust open the window with almost brutal strength, leaned half out in his ecstasy.

"Mine, all mine," he exulted. "Power of generator and dynamo, power of my atomic motor, power over New York and America, over Europe and Asia, power over billions of people, soon to be mine, all mine!"

His ox-like shoulders trembled with excess of emotion, his bony hands clenched and unclenched convulsively. So absorbed was he in the passion of the moment that he did not hear the soft opening of the office door behind him nor the even softer closing.

"The conference will start in ten minutes, sir. I have arranged to have them ushered into the directors' room as they arrive."

The quiet, unassuming voice impacted on Boling's rapt ecstasy like a gush of cold water. He jerked around with hot, resentful eyes that softened almost immediately as they rested on the slight, slim figure of the young man before him. Thick-lensed glasses covered mild blue, nearsighted eyes, and almost obscured thin, ascetic features. A very ordinary-looking young man, one who would merge indistinguishably in even the smallest gathering; an almost violent antithesis to his bold, masterful, domineering employer, John Boling.

Yet Boling knew Philip Haynes too well to be impressed by externals. Haynes had been his assistant for six months, had helped him immeasurably in the successful completion of the atomic motor. Boling readily and generously acknowledged, in private, that without Haynes' brilliant scientific knowledge, the motor would still have been merely an inchoate, dazzling vision. After all, Boling was no scientist. He was eminently a business man, a practical man of affairs, an engineer and power magnate.

"Very well, Haynes," he said. "I am ready for them."

His assistant's face was anxious.

"Do you think they'll back you, Mr. Boling? They promised to come to a final decision tonight, you know."

Boling laughed shortly.

"I'm not worrying. They'll have to," he said confidently. He stabbed out with a long bony finger. "Look. We've been having conference after conference for months now. They've gone over the proposition with a fine tooth comb. Cummings, the engineer of the outfit, has tested the motor time and again. It was successful, wasn't it?"

Haynes' face lit up with a flame of enthusiasm.

"Of course," he cried. "It's revolutionary; the greatest invention that has ever been given to the human race. The disruption of the atom; the utilization of its terrific power. Why, it's almost magical. I've checked it myself mercilessly. Every time I've sent a thousand kilowatts into its transformers and rectifiers, ten thousand registered at the output meters. Ten for one. It's amazing."

Boling smiled grimly. "They'll back me all right. It's to their own selfish interests."

"How about Janus?" Haynes ventured.

Boling's face clouded. "That sanctimonious, psalm-singing preacher! You're right; he may object. His oil interests will be ruined by the motor. He'll cover the fact with pious phrases. I'm sorry I called him into the deal." Then his shoulders squared, his rock-like jaw jutted. He pounded hairy fist into flat palm. "If he gets in my way, I'll wreck him, leave him out in the cold with the rest of the swine. This plan of mine is going through, come hell and high water. Power, that's what the atomic motor means. Power to wreck or save the world. And, by God, I mean to use it!" He was shouting now, his face an angry red.

Haynes looked at him with slightly shocked, yet understanding eyes. He knew the history of the man, the reason for his almost megalomaniac outbursts. John Boling had been a self-made man. Born in poverty and squalor, by the force of his indomitable ambition he had earned his way through engineering school, blasted his way from are obscure engineer in a great utility corporation to the general managership.

It was the heyday of American prosperity, back in the fabulous years of the third decade of the twentieth century. It was the age of mergers too. Boling had taken full advantage of the trend. By a series of bold, yet skilful maneuvers that left his competitors gasping, he had rocketed to a commanding position in a gigantic national combine of power and utility companies. It is true he was like a juggler perched precariously on top of a rocking, staggering pyramid of sweaty humans, yet had the late Coolidge and early Hoover prosperity continued, he would have cemented and consolidated his position into Gibraltar-like firmness.

Unfortunately prosperity took a nose dive that catastrophic day in October of 1929, and Boling found himself topping thin air, with the units of his laboriously assembled structure collapsing underneath him like a pack of cards. Even then, with proper financial assistance from the banking fraternity, he might have pulled through. But those gentry were as panic-stricken as any mob; they pulled in their horns and their loans with tragic, yet ludicrous haste. Besides, they had no special love for Boling. He was a domineering, browbeating individual, and had stepped on very tender corns too many times.

So the great combine collapsed, and Boling went with it. At forty-seven he had found his empire snatched from him, himself offered a subordinate position in an obscure utility by the smug bankers who had ruined him.

He rejected it savagely, and started a second time, at forty-eight, the long and bitter climb from obscurity to eminence. For power was what Boling wanted, loved, needed, with all the fervor of a practical man. He set for himself a frightful task. For years he struggled and labored, earning no more than the merest pittance, greying with age, the hard lines around his heavy mouth etching deeper and deeper. Yet his indomitable ambition, his avid, almost pathetic lust for power, for the seats of the mighty, the thrill of governance, kept him alive. Seven long years of hardship and labor as an engineering consultant; fruitless, discouraging.

For the world was staggering in the throes of the worst depression it had ever seen. Seven long lean years in which the peoples of the world felt the ever-growing pinch of starvation and despair. Countless millions were unemployed, few factories belched cheering smoke, machinery rusted from disuse, ships swung idly and rotting at their anchorages. The pulse of the world beat low; government doles of food were giving out; it required only a tiny spark to touch off the dry tinder of revolt. Communist Russia was no better off than capitalist France; agrarian India than industrialized America. All were seething in the same pot.

To cap the climax for suffering humanity, the year 1936 had brought in its wake a mysterious, far-reaching plague. It had been a year of unparalleled electric storms; the earth was swept time and again in a vast deluge of electrical phenomena and bucketing rains. Even more literally than the poet ever dreamed of, "the lightnings flashed from pole to pole."

But stranger still, at the end of each electrical disturbance, after the heavens had ceased spouting fire, hundreds of thousands of men, of every race and nation, lay down simultaneously, stricken with the same symptoms. A strange, queer, baffling mental malady, that left its victims blank-faced, staring, gibbering idiots, mouthing strange sounds that had no counterpart in any earthly language. And only men were stricken, men in the prime of life, between the ages of eighteen and fifty-five.

Philologists had carefully studied these strange, incoherent ravings, seeking for some basic root, but had confessed their bafflement. The language, if language it were, stemmed from no earthly root-stock.

As for the disease itself, manifestly a product of the weird electrical disturbances, there was no cure. It simply ran its course. In most cases the victims recovered, professing to know nothing of what had occurred during their strange malady, except that they had all experienced a sensation of intense pressure in their brains, as though outside forces were trying to break into their consciousnesses, trying to take possession of their minds. Of the unknown language, they remembered nothing.

A small proportion, yet considerable in point of actual numbers, remained permanent imbeciles; their weaker capacities bursting irremediably under the strain of whatever had impacted on their brains. The medical profession, psychiatrists, alienists, scientists of various persuasions, could make nothing of it. They shrugged shoulders, and hoped for no return of the inducing electrical storms.

Boling had been a victim of the very last mental epidemic, some six months before. Haynes knew this; knew that during his convalescence, the idea of the atomic motor had sprung full born into Boling's brain. It was curious. Boling was not an inventor, had never possessed the imaginative faculty requisite to true genius. More, he knew little of the physics of the atom, of the research that had gone into the problem of breaking it up. That was "pure" physics, and Boling was a practical man, with a practical man's ideas on abstruse science.

Immediately upon his recovery, Boling had called upon Haynes for assistance. Haynes was a brilliant young physicist, making a name for himself in the realm of "atomic physics.

Haynes listened, and became wildly enthusiastic. His trained mind saw at once under the halting phrases with which Boling expressed his conceptions that here was the answer to the tapping of the atom's energy which had proved heretofore an insoluble problem.

Even as he worked, swiftly and feverishly, night and day, in the little laboratory they had rigged up on the Jersey flats, converting the idea into tangible form, curiosity gnawed at him. Doling obviously am not know the meanings even of half the phrases he used to express the highly complex formulations of the atomic motor; he spoke as a man who had learned his piece by rote.

"Tell me," Haynes asked frankly one day, "how do you account for the fact that, without possessing the proper mathematical and scientific foundation, you were able to invent the atomic motor?"

Boling smiled secretively. "I believe I've told you before. It came to me at the end of my—er—illness. Something was boring into me, trying to get it, so it seemed. The pain was frightful. Suddenly there was a flash as of light inside my mind, and my brain seemed to expand immeasurably. It was as though whatever had tried to get in, had succeeded. In one lightning-like instant the whole universe seemed to be unfolded to me; everything, every problem that has ever puzzled humanity, stood stripped to ridiculous simplicity."

He paused and frowned. His words came slowly, as though he were trying to explain the whole inexplicable affair to his own satisfaction.

"Then the universe crashed into darkness. When I came to, they told me I had been ill, but that I was over it. I tried to remember. But everything was vague and shifting except for one thing. The idea of the atomic motor rose before me with startling clearness; every part properly coordinated with every other part, just as I have given it to you."

Haynes had looked at him suspiciously. Was the man trying to pull the wool over his eyes? But no, Boling seemed absolutely in earnest.

"I see you don't believe me," he said.

Haynes shrugged his shoulders and let it go at that. There was one thing that struck him with peculiar force, though. There had been no electrical storms with their concomitant train of mysterious mental maladies since Boling's convalescence. Where lay the connection?

The motor had been finally completed, a great shining mechanism of curious coils, transformers and rectifiers. Together they had bombarded the gases in the test chamber with the lightning energy of high potential currents. Before their very eyes, the atoms had disrupted into a vast flaming surge of high speed electrons. The meters jerked violently, telling the story. Ten for one. Ten units of energy for every one inserted.

Haynes' task was finished. It was Boling's turn now; the ruthless man of business, the practical man He acted immediately, the thrill of domination coursing through his veins like a heady wine.

He chose with careful deliberation eleven men, men of standing and of influence, men with money and a reputation for bold dealing, men diverse in character and profession, yet all equally ambitious. To them he had unfolded his plans with guarded reserve.

It was nothing more or less than the establishment of a world-wide industrial empire with the atomic motor as the basis, and themselves as a Council of Dictators in control. Eventually, he hinted subtly, political domination would follow. He proposed a hundred million dollar investment with which to commence their onslaught on the industrial world.

Naturally, they had been startled, incredulous, even scoffing. But his earnestness, his reputation for sanity and shrewdness, his offer to submit the most elaborate proofs, had conquered their initial distrust.

For a month of days he had gathered these moneyed men, leaders of industry, into his Jersey laboratory, shown them the magic of his motor. Cummings, himself an eminent engineer, checked the equipment from every angle, searching for hidden power sources. Boling smiled grimly and let him search. No one could duplicate the process. Certain alloys, certain thread-like filaments, were of a composition known only to himself and Haynes.

Cummings had at last been convinced, and the group had returned to New York, fascinated with the vistas of power compacted to their hands, yet hesitant at the full implications of the scheme. A week of discussion, almost of wrangling, until Boling had boldly thrown down the gauntlet.

"This is your last chance," he declared. "We shall hold one further conference, and no more. Either you play along with me, or I'll seek another group of more daring men."

This was the deciding conference. Boling would know his fate at their hands within the next hour. He felt strangely calm.

Haynes, watching him, marvelled at his control. He himself felt his heart pounding thickly. It seemed to him as though the destiny of the world depended upon the next few minutes.

The door opened softly. A mouse-like secretary thrust her brown bobbed head into the room.

"The gentlemen are ready for you," she said.

Boling nodded, walked with steady tread through the door held respectfully open for him. Haynes followed, a sheaf of notes and data pressed tight under his right arm.

THE men rose from around the long shiny conference table upon his entrance. The thick-piled carpet muffled his footfalls. Little murmurs of greeting rose like puffs of wind as he shook each man's hand with a quick firm grip.

For the last time he appraised these men who held his destiny, and the destiny of the world, in the hollow of their hands.

Morse Cummings, short, compact, self-contained, world famous engineer and financier. All life to him was a matter of engineering problems. The atomic motor to him was purely a wonderful maker of profit. He was not interested in its human implications.

Henry Burbridge, coldly patrician, inscrutable, surveying the world with faint disdain out of cool gray eyes. He was a firm believer in oligarchies; the thought of a few men, himself included, ruling the world, was what attracted him to the scheme. There was no nonsense with him about democracies, the right of the people to govern themselves, however badly. His money came from railroads and transportation.

Major General Robert Woods, a slight, weazened man, bird-like in features, eyes that were bright and beady, yet without a doubt the most famous warrior of modern times. Veteran of many wars, a brilliant campaigner, who possessed the faculty in this machine age of making his men glad, even eager to die for him. A most essential component in the subtle web that Boling was weaving.

Josiah Biggs, eminent corporation lawyer and skilled in driving teams of horses through tiny inconspicuous loopholes in the law, paunchy, florid, prone to wave a black-ribboned pince-nez with large deliberate gesture when speaking; Benjamin Faulkner, New England woolen manufacturer, nervous, excitable; Lanier Stoddard, a sallow dark little man with Italian features and close-clipped black mustache. He was a fanatic on the subject of Nordic supremacy, the big blonde brute was his beau ideal of the superman. There were also Vincent, Scupps, the publisher, Provost, Harwood, chosen for the money at their command, but otherwise colorless.

All these men Boling greeted with quick staccato phrases, but when he came to the last man, his bold black eyes narrowed beneath bushy gray brows, his handshake was frankly interrogative. This was the man he regretted having included in his plans, the man who might yet prove the stumbling block.

William Janus took his hand with white limp grip. His tall slender frame was garbed in sombre black; his dress affected the clerical touch. A soft black felt hat dangled forgotten from his left hand. His thin bloodless features were cast in a pious, sanctimonious mold, his pale blue eyes looked eternally down a long narrow nose. A most irritating contrast to the full-blooded gusty vitality of Boling.

He had inherited vast oil interests from a hard-hitting father, interests that would be ruined by the introduction of the atomic motor. A faithful contributor to the Anti-Saloon League, the Anti-Nicotine League, the Anti-Life League, in short, to anything that sought to smother the natural appetites of man.

Boling took his seat at the head of the long shiny table, Haynes dropping unobtrusively into a chair to his left.

"Shall we begin, gentlemen?" he asked briefly.

Murmurs of assent came to him from the tensed figures.

After a quick look down the long polished table, noting with curious irrelevance the reflected faces staring up at him, Boling rose to his feet.

"Gentlemen," he said forcefully, "the issue is perfectly clear, and must be decided, one way or the other, this evening. There must not be, there cannot be, any further delays. You have seen the atomic motor, you know what it can do. The terrific power of the disrupted atom is ours for the handling. There need be no further worry about exhaustion of natural resources. Coal may give out," he nodded to Burbridge, "oil wells may peter out," he turned to Janus, "water courses may eventually dry up, but the atomic motor will continue to extract incredible energy from the inexhaustible elements. The day my machine appears on the market, every other source of energy will become antiquated, obsolete, fit for the scrap heap."

He paused and looked up and down the long table at the diverse upturned faces.

"So far we are agreed. You are all willing to pool your finances to back the marketing of the motor, to make money out of its exploitation. But," and his voice took on a deeper, harsher note, "that is not enough. I want more power for myself," his balled fist crashed startingly into open palm, "and for you."

To Haynes, sitting nervously, there seemed a curious hesitancy over the last part of the phrase.

General Woods glanced up sharply.

"Just what do you mean by that?" he asked.

"This. We shall organize ourselves in a Power Council. Biggs will take care of that end of it. We shall not sell or lease our motor. We shall permit the various industries to use it only in return for controlling interests. If they refuse, we start competitive factories, and with our infinitely more efficient motor, drive the recalcitrants out of business, buy them up for junk."

"To what end?" Burbridge inquired, faint interest showing in his cold aloof eyes.

Boling smiled strangely. He enunciated his words slowly, distinctly, as though savoring their import.

"That we may eventually obtain control of the entire world, to be held tight in the hands of a group of a dozen determined men, to wit, ourselves. Political divisions, racial demarcations, will mean nothing to us. The earth will be one vast province, a single unit, and we its dictators, responsible to no one but ourselves."

There was a faint stir of consternation, an audible sucking in of breaths. Only Burbridge leaned forward, nodding his aristocratic head. And General Woods, tapping the table with a rubber-tipped pencil, darted his bright, bird-like eyes eagerly from face to face.

It was Biggs who broke the stunned silence.

"You understand, Boling," he said slowly, "that what you propose may not be quite—er—legal."

Boling brushed the objection aside with an impatient hairy hand. "Legality has nothing to do with it. Once we come into power we shall make our own laws, as the governing classes have done from time immemorial. It will be your duty to frame the new legal code."

There were faint murmurs of approval from Burbridge and Stoddard. Janus sat quietly, his pale clerical face reflecting nothing of his thoughts.

Faulkner stood up self-consciously. "While I am wholeheartedly in favor of utilizing the atomic motor," he said quickly, "I question the wisdom of destroying the industrial system as it now exists. I for one am afraid of setting ourselves up as men on horseback. It smacks of Bolshevism, of Mussolini, of everything repugnant to our cherished American traditions. Why can't we, say, back this thing as a purely commercial enterprise, rent out our motors, reap the profits? They should be enormous. Why must we overthrow the entire structure of things?"

Vehement nods from the colorless men of money.

Boling growled angrily in his throat, like an enraged bear. Before he could speak, though, Biggs was talking.

"You forget," he said gently to Faulkner, "that once these motors are leased out to the nations of the world, there is nothing to prevent them from forgetting about their legal obligations to us in the way of royalties."

The roar burst full-throated from Boling. His face was red, and he pounded the highly polished table.

"Stuff and nonsense. I am not going to evade the issue by such subtleties as Biggs proposes. Let any one refuse to pay, and I can stop the operation of their motors instantly by certain short wave radio signals at my control. Let us face the issue squarely.

"The world is in the throes of a horrible depression. Millions are starving. Revolution is staring us in the face. Our present leaders are politicians, without vision and without imagination. They are incompetent imbeciles, unfit to rule. They must be thrown out.

"If we give them the motor, we help maintain them in power, help perpetuate the present imbecilic system. The motor will revolutionize industry. Unless properly guided by determined men, it may prove a curse, mean chaos, the ruin of civilization.

"No. For better or for worse, we must grasp the opportunity. Let us organize the world, seize the power, administer it wisely for the benefit of all humanity, and—sit in the seats of the mighty."

Applause from four of the men greeted Boling as he concluded his impassioned address. Haynes sat on the edge of his seat, his weak eyes shining. This was why he followed Boling. A strong coherent organization of the world, an equitable distribution of the material resources to all the people, so that misery and starvation and selfish strivings be forever at an end. The atomic motor with its vast reservoirs of power, coupled with the benevolent dictatorship of bold, determined men; to what heights couldn't mankind rise? True, a dictatorship was distasteful. Haynes had an old fashioned faith in the ability of a free people to govern themselves. But one step at a time.

"That means social revolution," Biggs interposed again. "Perhaps war."

"We will be ready for that," Boling responded. "We shall start recruiting an army, well paid, professional, immediately. I rely upon the pressure you gentlemen can bring to bear upon the American government to line up its forces on our side. Besides, the people are sick of the demagogues and quacks who now lead them. They are ready to turn to new leaders. Their empty bellies are our most potent allies. As for armed clashes, I'm sure General Woods is competent to handle that."

"Assuredly," Woods spoke calmly without rising. "Gentlemen, John Boling is absolutely right. I move we vote him our immediate approval."

At once the meeting broke up into angry, heated groups. There were two well defined camps. The colorless men of money, with Biggs and Faulkner, held for moderation, for purely financial projects. The thought of dictatorship left them aghast. But it was that very thought that attracted the other group; Burbridge, Cummings, Stoddard and Woods.

Only Janus held aloof, sitting quietly through all the tumult with flabby hands folded in front of him, pale thin lips compressed, face emotionless.

A broadening line of impatience traced itself across Boling's brow. The meeting was getting out of control. It was time for a bold stroke. He glanced across at Haynes, who nodded slightly. He pounded the table.

"Gentlemen," he cried. "We are not getting anywhere. You are acting like a high school debating society, not like potential rulers of the world. I, for one, am willing to leave the final decision to William Janus. He has not indicated his sentiments at all so far. Let him decide for all of us."

The wrangling ceased at once; the hot, weary men seized upon the way out. They shouted vociferous approval.

Boling looked at the silent oil man with something of alarm. He had not intended saying what he did. Janus, the man he feared most, to be the arbiter of his destinies. It was savagely ironical. Yet the words had forced themselves out of his mouth without any volition on his part. It was as though someone else had spoken through him, and he were only a mechanical mouthpiece. Haynes was staring at him aghast. Had Boling gone suddenly crazy?

It was too late now to back out. Janus had risen ghostlike to his feet. Very quietly he adjusted the black tie from under his clerical collar. There was a sudden hush. Then he spoke. His voice had a singsong monotonous note, his manner was that of the pulpit.

It was, he said in part, Divine Providence that governed all his actions. He had always considered himself an unworthy trustee in the administration of his oil interests. He had humbly striven to justify the ways of God to man.

At this point their were little sceptical smiles. Haynes was indignant; he remembered only too well the savage suppression of strikes on the Janus' properties, all in the name of God.

He could trace, he continued unctuously, the finger of God in the discovery of the atomic motor. It could never have been invented without Providential aid.

Boling started visibly, and Haynes looked up with sudden interest. The pious fanatic had unwittingly brought back to him something he had almost forgotten. The strange electrical storms, the mysterious maladies in their wake, the startling revelation of the secret of the motor to Boling while seemingly delirious. Was it possible that with his unctuous phrases the oil man spoke wiser than he knew?

Then startlingly. "If God has deigned to choose us, unworthy wretches that we are, as the humble vehicles of His designs, it would be presumptuous of us to refuse. We are His appointed trustees, the atomic motor is the weapon forged to our hands, and it is our bounden duty to accept the responsibility thrust upon us, and in all humility strive to establish God's kingdom upon earth."

He sat down, and placidly folded his hands in front of him. The men stared at him, his pious phrases had jarred. Burbridge and Woods were smiling cynically. But there was no mistaking the purport of his speech. The Janus interests held certain powerful controls over the colorless men of money, Biggs received a substantial part of his substantial income as their chief counsel. The others were weary of wrangling. The oracle had spoken, and they were content. In that instant the Power Council was born!

When, an hour later, Boling and Haynes emerged to the street below, it was quite dark. The city seemed bathed in an electric haze. Waves of heat, almost tangible, swept down to the canyoned avenues, Haynes felt a curious electric tingling at the nape of his neck. Boling looked haggard, weary.

"That was a stroke of genius on your part," Haynes said, "calling upon Janus to cast the deciding vote. I thought you had gone suddenly mad at the time, but the event justified itself."

Boling turned a worn face to him. The ruddy vitality was drained; there was a strange look to him. He raised a trembling hand to a perspiration-dripping forehead.

"Mad!" he echoed vaguely. "Yes, I must have been. I had no intention of saying what I did. I was going to lay down the law to them, when something snapped in my brain. The next thing I knew I was speaking mechanically; it was not I, it was a superior force using me as an instrument."

He stopped suddenly, heedless of crowded Fifth Avenue, or of the people who paused to stare curiously, and gripped Haynes' arm.

"Do you know, it was exactly the same sensation I had when I was ill; when the thought of the atomic motor flashed into my mind."

He shook his startled assistant viciously, his voice contained almost a hysterical note.

"What does it mean, Haynes, what does it mean? Can it be true I am mad, or going mad?"

Haynes strove to soothe the trembling man, irritably aware of the passersby.

"Of course not," he said as calmly as he could. "It is just the way genius acts. Ideas come in lightning-like flashes. Let us walk. The air will do you good."

Boling walked at his side up Fifth Avenue, seemingly reassured. But Haynes felt uncomfortable. It was a strange affair, come to think of it. And Janus' pious phrases, nonsensical as they were, had touched off hidden misgivings. But Haynes shook his slightly stooped shoulders, as though to rid himself of a gathering load of superstition, and talked matter-of-factly of their plans, the tremendous problems confronting them.

The air was getting more and more sultry. An immovable force seemed to press down upon the city, deadening even the raucous sounds of slow-moving traffic. Sheet lightning glared intermittently, masking out the bright street lights of Fifth Avenue. Thunder rolled with an ominous sound. Haynes looked upward uneasily. High overhead, framed between the tall structures, blobs of cloud were forming. Long jagged streamers of flame crashed from one to the other. The blobs moved swiftly toward each other, coalesced into a blinding flare.

Haynes hurried his pace, his brow furrowed uneasily. Another of the electrical disturbances was brewing. It had been over six months since the last one. Was there going to be a recurrence of waves of insanity? All traffic had ceased. People were scurrying wildly for shelter. Haynes felt an immense hand plucking at his brain. He cast a sideward glance at his companion. Boling's face was ghastly in the blue electric flares. He put a weak trembling hand to a damp perspiring brow.

"I—I don't feel very well, Haynes," he said weakly. "Something wrong; just as I felt before my illness." He looked apprehensively about him, as though in the deepening haze, in the now blazing skies, he might discover the cause of his indisposition.

They were at the door of Boling's hotel.

"Shall I help you up," asked Haynes anxiously.

"No, I'll be all right. Just need a little rest." Boling held himself upright as though with an effort.

"Shall I see you tomorrow?"

"Of course. We must get to work. There is a good deal to be done. This will pass."

Haynes watched a frightened doorman help him heavily to the elevator, and continued thoughtfully on his way through deserted Forty-Second Street to Grand Central Terminal. He was worried over the queer illness of Boling. Strange that that strong man should be suddenly weakened, strange that it should come now when an electrical disturbance was impending. People crowded and shoved him on the subway platform. They were like hunted animals, intent on getting safely to their lairs. Memories of former storms showed in their fear-stricken countenances; each feared for his own sanity in the inevitable wave of madness to follow.

But Haynes did not heed the buffeting. The whole affair was a jigsaw puzzle, in which he held only scattered non-fitting pieces. The key ones were missing.

The train was rushing through dark tunnels toward Long Island, when suddenly an interminable pressure seemed to have been lifted from Haynes' dulled and aching consciousness. He looked around him in surprise. Everywhere he saw men breathing freely, as though they too had been freed from a nightmare weight. A buzz of conversation arose. Only then did he realize the utter silence that had enveloped them before.

Looking about him more carefully, he noted, as always, with a slight shock, the haggard thin faces, the threadbare clothes, the lifeless dejection of his fellow travelers. Seven long years of unrelieved industrial depression lay like a blight over the world. Politicians, industrialists, financiers, fought for power, bickered selfishly among themselves, heedless of the sullen despair, the slow starvation of their fellow beings.

Never was the need more urgent for a strong dictatorial hand to sweep aside all futile factions, to organize humanity and life itself. The atomic motor, with its illimitable power, was the potent weapon.

Haynes felt that John Boling was the man for the gigantic task of cleaning the Augean stable. True, he was no humanitarian, no philanthropist. Haynes in his deepest heart recognized Boling for the implacable tyrant, the ruthless seeker for power, that he was. But better a tyranny in which everyone was fed and clothed, in which life was organized once more, than the slow decay and dry rot of the present Time enough to consider social changes; freedom, democracy; after men had food in their bellies.

His mild near-sighted eyes glowed strangely behind their thick lenses, his weak-seeming mouth tightened in hard lines. Casual acquaintances might have been surprised at the metamorphosis of their inconspicuous friend.

THE cars were emptying quickly, and Haynes moved forward toward the door. The next station was his. As he stepped out on the platform, he noted with surprise that the sky was cloudless and clear, that is, as clear as it ever could be in smoke-filled New York. Tiny stars pricked the dusty blue. The tremendous electrical disturbance had passed over without a sign.

Three blocks to the left, and he stepped with eager anticipation into the little self-service elevator that carried him to the floor of his apartment.

Philip, Jr., his small two year-old son, greeted him with loud incoherent cries and outstretched chubby arms. Jane, his wife, her ordinarily bright face a little worn, lifted warm lips to his caress.

"I was getting worried," she said. "It is so late."

"Couldn't help it, dear. There was quite a fight for awhile."

"Did it end well?"

"Yes. Boling won out. They all agreed to his terms. A hundred million is being banked tomorrow to the order of Power Council, Inc. Boling will have control of the funds. They're leaving a good deal to his discretion. We commence work at once."

Jane looked thoughtful. "You're sure, Phil, the motor will really work? It seems so unbelievable." She blushed a little as her husband laughed. "Of course I don't understand such matters very well, and you've tested it carefully. But I'm a woman, and look at the practical side. Boling was the last man in the world to have invented something so revolutionary. Don't you see. I have an uneasy feeling that he might be tricking you all."

Haynes shook his head negatively. "You know I am no novice in scientific matters. The plans were theoretically sound, and they worked in practice. If there were a trick, I would have discovered it, and so would Cummings. It's true. Boling has discovered a source of limitless energy."

"And that will mean a new deal for the poor starving millions?" Jane asked hopefully.

Her husband's thin hands, long, sensitive and eager, gripped slowly on the edge of the table.

"It must," he breathed inaudibly. "We will overturn the whole industrial world. Boling and his group will become dictators. There will be a limitless supply of good things of the earth for everybody."

"And Boling—?" Jane asked with curious hesitation. "Yes, I know," Haynes answered her unspoken thought. "He will rule with an iron hand—tyrannically! He will brook no opposition. But what he has to offer is worth the price. The peoples of the world must be fed and kept alive. Afterwards, well, we shall see..."

"I'm afraid, Phil," she said later, worriedly, as they prepared for sleep. "I'm afraid it won't be as easy as all that. Once Boling and his crew gain control, there'll be no chance for freedom. The earth will stifle into slavery."

"Nonsense, dear," he retorted confidently. "Civilization has progressed too far for real old-fashioned tyranny. Either Boling will change for the better, or the people will rise in revolt, and overthrow him."

But far into the night, after Jane had dropped into slumber, he lay awake, wide-eyed. Jane's premonitions had made him more uneasy than he cared to admit. He had never told her of Boling's confession as to the source of his ideas. It might have worried her. Nor had he told her tonight of Boling's inspired calling upon Janus for the final decision, nor of the strange electrical disturbance in New York, and Boling's curious illness. For the first time it seemed to him that Boling might be only a mere automaton!, a conducting vessel through which strange forces were seeking to mold their will upon the world. A terrifying conception—and impossible one! Yet—how else explain the curious concatenation of events? The electrical storms, the frightful mental disorders in their wake.

Haynes felt suddenly small in the presence of dark immensities. Were these supernormal forces benevolent, or evil in their intent? Or were they merely working out their own vast incomprehensible plans, unrecking, unheeding of effects upon the tiny creatures called men?

Then he laughed aloud, and the laugh sounded hollow to his ears in the dark. Jane stirred restlessly at the sound. Fine thoughts for a scientist to be thinking in the dead of night. The strain of the day had proven too much for him. He turned over and deliberately tried to sleep. But his slumber was fitful. Sudden, inexplicable waves of dread passed through him; for deep and remote in his mind were forebodings that would not pass away.

The weeks that followed, in that long, hot summer, were breathless ones for Boling and Haynes. Haynes marveled at the sheer organizing genius of the man as Boling laid the groundwork for the introduction of the atomic motor. With skill, with blunt mastery, with promises and threats, Boling went about winning to his support the men of influence, the political factors requisite for his incipient empire.

To the other members of the Council were delegated the arduous tasks of organization. Cryptic advertisements in the newspapers, secret proselytizing among desperate members of the various American Legion posts, above all, the magical lure of General Woods' name, attracted hordes of bold, reckless men, skilled in the use of arms, ready to face the devil himself in return for three squares a day and a place to sleep. They were scattered into small units, unknowing of the existence of the others, kept in the dark as to the real purpose of their employment, and not caring a damn.

Haynes saw a battalion drilling secretly in the scrub pines of Long Island. A reckless hard bitten crew, who handled their weapons smartly and with obscene jestings. Their commander, strangely enough, was a Frenchman, a veteran of the World War. Colonel Alphonse Colette was rotund, fiercely mustachioed, strutted like a pouter pigeon, yet Woods assured Haynes that he was an efficient officer and an excellent drill master, though lacking in imagination, and too vain for his own good.

Biggs proselytized among his own gentry, the legal profession and the bench. Cummings supervised the construction of an enormous factory on the Jersey flats, and began work on a number of monster motors, ready for distribution at the proper time.

Janus and Harwood, a newspaper publisher, turned out skilful propaganda by the tons. Janus organized the churches. The coming of a Messiah was hinted at. Already the world sensed with strange excitement the preparation for portentous changes. It was ripe for the plucking. Anything was better than what the people had.

The new Empire was almost ready to disclose itself, slip quietly into place of the old.

Haynes himself led a nightmare life. He rushed around the country in fast planes, arranging huge contracts for the purchase of materials for the motors, representing Boling in all financial transactions, keeping him informed as to the activities of the directors.

The hot summer of 1937 yellowed into autumn and then into an abnormally warm winter before Boling announced that the Power Council was ready to act. There had been innumerable private meetings before. In spite of the rush of affairs, certain discords had developed among the members of the Council, quarrels that related mainly to future allocations of power between them. Boling had surveyed them in scornful disgust.

"Like a pack of children," he shouted savagely. "If you keep on quarreling there will be no power to divide. Wait until we get it. There will be enough for all. And remember," he pounded, "I'll brook no interference with my plans. The man or men who get in the way will be crushed."

Already he was unsheathing his claws. The strange illness that had overtaken him the evening of the final decisive meeting had left him the next morning when Haynes had called. He seemed younger, more vigorous than ever, more lustily domineering. The Power Council subsided at his bellow, all, that is, except Janus—pale, self-contained, sanctimonious as ever. He sat through the stormy sessions with faintly smiling face, his long fingers pressed gently together in front of him.

"That's the only man I'm a little afraid of," Boling acknowledged to Haynes in a moment of frankness.

Haynes was returning to New York from Chicago by cabin plane, when the Power Council went into action. The radio newspaper droned in the luxurious cabin.

"Utility stocks and bonds continue persistent decline. Mysterious short selling of stocks forces values to new lows." Then followed uneasy statements from banks and insurance companies—large holders of utility securities, loud cries for government investigation.

Suddenly Haynes sat bolt upright. The newscaster was speaking with a tremor of excitement in his voice.

"Startling developments. Organization known as Power Council claimed to be back of short selling. Possessed of unlimited funds. Claim to have new motor, powered by the disruption of the atom, that will make all other sources of power obsolete. If this is so, and we have it on unimpeachable authority—(Haynes smiled grimly. The unimpeachable authority was Janus) then the bottom will drop out of the market. It is rumored that the Power Council is already in conference with the President to avoid chaos. More developments as we get them. Radio-News signing off."

Haynes' heart pounded. It was the beginning. Swift depression of stocks by throwing all the funds at their command into short selling at a time when the skilfully worded announcement of the atomic motor had all investors panicky as to the future of their holdings. Already, quietly and unostentatiously, the Power Council was picking up selected stocks at panic prices, buying control of key industries.

"A very pretty piece of work, sir."

The words came in so pat with Haynes' own thoughts that he nodded absently. Then realization flooded him, and he turned abruptly. The passenger on his left had spoken them. He found himself staring into a pair of shrewd, estimating black eyes, surmounted by a sloping forehead from which the straight, shiny black hair was carefully brushed back. Pinched thin nose and thin tight lips lent a secretive, cunning air to the man.

"Just what do you mean by that, sir?" Haynes demanded.

The man chuckled thinly.

"Oh, it was easy to see what you were thinking about as the newscaster told his little piece. You are Philip Haynes, are you not?"

"I am Haynes, though I confess I am in the dark as to how you know my name. But I still don't understand your remark."

The man nodded with a self-satisfied smirk. "You are quite right to pretend ignorance. It is part of the game. Very few know as yet that you are a member of the Power Council."

Haynes sat bolt upright, astounded. The secret had been a closely guarded one, yet here was a total stranger blandly telling him about it.

"You are mistaken," he said coldly.

The man edged nearer.

"You needn't be afraid of my knowledge," he said eagerly. "I came upon it quite by accident. You see, Provost, one of the members, is my first cousin. My name is Ferdinand; Karl Ferdinand."

"So he told you, eh?" Haynes burst out indignantly.

"Oh no. I happened across some papers in his study one day, and being curious, I read them."

Haynes stared at the man in blank astonishment.

"You mean," he said in a low voice, "you read the secret papers of your cousin without his knowledge?"

"Why not?" Ferdinand answered blandly. "They were interesting."

Haynes was overwhelmed. Not so much at the disclosure of their secrets; they were practically in the open now; as at the tremendous effrontery of the man. With violently conceived dislike he turned rudely to the right and stared out of the cabin window at the Pennsylvania landscape beneath.

But Ferdinand was not so easily to be cast off.

"Listen, Mr. Haynes," the voice said eagerly in his ear. "I think the Power Council has the right idea. Take control of the entire earth and run it to suit themselves. No nonsense about elections and representative government and all that truck. It's just what the rabble needs."

Haynes faced about and said frostily. "You seem to have an intimate knowledge of the plans of this Power Council."

"Of course," Ferdinand smirked. "My cousin kept full notes on all proceedings."

Haynes surveyed him up and down with as much contempt as his nearsighted eyes could bring to focus through the thick-lensed glasses. His lip curled.

"I make it a point never to speak to eavesdroppers and snoopers."

"Come now," Ferdinand protested, "I only did what any normal curious man would have done under the circumstances. Get me straight. I'm not seeking to put my information to use—that is—if I can help it. But I want a job with the Power Council. I'm a technician, an engineer. I've been out of work for years." There was hatred in his eyes. "I've lived on the scraps, the bones, that my esteemed cousin, the millionaire Provost, was condescending enough to throw me. I've had enough of that. I'm ambitious. I want a job, a good job, with a future. I can help the Power Council, and it can help me."

Haynes looked at him curiously.

"Why don't you go to Provost then?"

The black eyes were malignant. "Never," he burst out violently. "He'd give me a slave's job, where I could never raise my head without having it scotched. It pleases his vanity to have me dependent upon him." Ferdinand's hands were twisting uncontrollably. "No, I want power, just the same as you gentry of the Power Council. Power, and by God, I'm going to have it!"

He stopped abruptly, his face a drawn mask. It seemed to Haynes as though he were looking into a volcanic hell of twisted desires.

"I can't do a thing for you," Haynes said decisively. "In the first place I know nothing of your mythical Power Council, and in the second place, even if I did, I don't think you're the kind of man I would trust with anything."

Ferdinand's face contorted with rage. "You refuse my services? Very well then. Remember, I know things."

"If there is such an organization as this Council," Haynes pointed out deliberately, "no doubt they would know how to handle men who threaten them with exposure."

Ferdinand collapsed like a pricked balloon. Terror was writ large on his sharp-pointed features.

"I was only joking," he literally grovelled. "I don't know a thing, really I don't, Mr. Haynes. There's no such organization as a Power Council, ha! ha! I can keep my mouth shut. You'll be sure to tell them that, won't you?"

"Why, the man's an arrant coward," Haynes thought with contempt. He did not even reply to Ferdinand's whining pleas, but rose from his seat, crossed over to the other aisle, somewhat in front, and reseated himself. For the balance of the trip, he kept his eyes on the terrain below. Ferdinand kept discreetly to the rear.

In the bustle of leaving the plane at the landing field near New York he forgot completely about the man Karl Ferdinand.

The announcer completed his short introductory remarks and stepped aside to permit Boling to face the microphone. The atmosphere in the spacious broadcasting hall was tense. Even Boling, massively self-confident, held the sheaf of notes with a hand that trembled slightly.

Immediately behind him sat Haynes, face flushed, nervously twisting a button on his coat. To the right was Janus, pale, composed as ever; on the left, General Woods, twisting his head with little bird-like gestures. Two hard-looking men lounged against the door of the studio, responsively alert to the slightest gesture from the general. Three officials of the National Broadcasting Company hovered discreetly in the background, in their demeanor anxiety and concern. It was a crucial moment for the entire nation, for the world!

Boling began his speech into the microphone in clear, deliberate tones, bending over his notes, emphasizing his points with a forward thrust of his massive, sculptured head.

"I am speaking," he said, "at the request of the President of the United States. The times are crucial. Panic and despair hold the country in their grip; our major industries are bankrupt; the suffering of the people becomes daily more intense; the forces of law and order are weakening. Crime stalks the streets of our cities openly; desperate starving men are looting and rioting.

"I shall be quite frank," Boling went on. "Within the past three months the Council has purchased controlling interests in the largest power and utility companies of the country. We have taken over bankrupt banks and manufacturing companies. We now in large measure control American industrial life.

"We intend offering no excuse for what we have done. To the starving hopeless millions of this nation I say that you have been dominated for years by selfish, shortsighted, incompetent men in control of great industries. Most of them have been displaced in the last three months, and deservedly so. The process will continue until all are ousted, until a new industrial order has been established in America. And in control of that order, rigid control, mark you, will be the Power Council."

He was talking straight from the shoulder, and the nation hung breathless on his words.

"The men of the Council," he went on, "are able, intelligent, strong. They will not misuse their power. You, the starving people, shall benefit. Already one hundred thousand men have been employed in our factories to manufacture the atomic motor. This motor will supplant all present electric generating equipment. Power in infinite abundance will shortly begin to flow to factories, farms and homes, to give new life to our nation.

"Food, clothing, shelter, yes, the luxuries that yesterday were only for the very rich, will soon be within the reach of all. I can promise this nation, and I am also addressing myself to all the world, that we are on the verge of a new epoch, an epoch in which material wealth will flow in unparalleled abundance. And because the atomic motor produces such extravagant power, the human race will at last be released from the curse of excessive toil that has been its heritage since Adam's time. We have calculated that not more than two or three hours of pleasant labor per day will be required from every able-bodied man. In return for these blessings, the Power Council demands one thing..."

The door of the studio opened softly and closed even more softly behind a well-dressed man in spats and tan overcoat. He walked with noiseless tread over the felt-deadened floor, right hand hidden loosely in overcoat pocket. The hard-faced guards at the door watched him uncertainly, looked to Woods for orders. But none were forthcoming. The general was intent on Boling's dramatic words, as were the others. And the man looked like an important personage, an official of sorts.

Suddenly, as Boling prepared to drive home his final, most important point, the man sprang with the agility of a cat, thrust him violently away from the microphone, whirled, and covered the startled beholders with a flatnosed automatic. Boling staggered backwards, found himself staring directly into the little round bore.

"John Boling," he rasped.

Boling had recovered his stance. "I am Boling," he said quietly. "What do you want?"

The man levelled his weapon. "Dog, traitor!" he screamed. "You ruined me; as you ruined thousands of others, as you intend to ruin the nation in your mad pursuit of power."

Boling raised his hand. "Wait a moment," he said sternly.

"Wait... wait..." the intruder screamed again. "You'll wait in hell..." The carpeted silence was broken by a sharp dead roar that died away as quickly as it had sounded. No echo returned to fill the empty silence as the wisps of smoke hung around the still levelled gun.

Boling staggered backward, clutching his left arm. The tense immobility was broken. Haynes and Woods rushed forward simultaneously. Janus kept on sitting, pale, imperturbable.

The weapon thrust forward again. The well-dressed man's face was fiendish to look at. Two reports sounded in rapid succession. The man opened his mouth wide. A look of ludicrous astonishment gleamed in his eyes, then they clouded. He screamed once, horribly, the revolver dropped from suddenly nerveless fingers, and he pitched heavily to the floor. A widening pool of red stained the green and gold of the carpet.

The two hard-faced men came coolly forward, spinning their automatics suggestively.

"Sorry, General," one of them said apologetically, "but we couldn't get a bead on him at first. Mr. Boling was on a line with him."

"Good work, men," Woods nodded crisply. "Tell Colonel Colette you rate corporal's stripes."

"Thankee, sir." The men saluted smartly and returned to their post of vigilance.

Haynes had rushed over to support Boling, who had gone white. A thin trickle of blood oozed through the sleeve of his coat.

"It—it's nothing," he gasped, "only a scratch. Hurry, help me to the microphone, I—I must complete the message."

With Haynes supporting him, Boling again faced the disk. His voice was weak at first, but gained strength as he went along.

"I regret the unfortunate interruption. A crazed fool tried to shoot me, and missed. I must conclude my address. I have told you what the Power Council has to grant. In return it demands one thing. Non-interference in its activities from politicians, demagogues, governments. Let us be hampered in our work, and the atomic motor will be withdrawn, its secret destroyed. The world will then be plunged back into the chaos, from which we have extricated it. That is all."

BOLING'S arm was neatly bound. The wound, the doctor in attendance at the studio hospital said, was not serious. The room was full of people with tense drawn faces.

One of the broadcasting officials glanced out of the window, withdrew his head hastily. His face was white.

"Good Lord," he said. "There's a mob outside; thousands of people. I don't think it's safe to leave just now." Boling grunted. "Pm ready to leave. Will you help me, Haynes?"

With his assistant holding him carefully by the uninjured arm, flanked on either side by Woods and Janus, and the two soldiers of the Power Council watchfully bringing up the rear, Boling proceeded steadily to the elevator, and was whisked swiftly to the ornate lobby of the building.

The heavy bronze doors of the entrance were barred. A squad of police guarded the interior, nightsticks grasped firmly.

A police sergeant came over to Boling.

"I don't think it wise to go out now, sir," he said respectfully. "This mob seems to be in a pretty ugly temper."

"What do they want?" Boling asked shortly.

"You, I'm afraid. They've got weapons, too."

"Rubbish," Boling snorted. He turned to his associates. "I'm going out."

Janus said sanctimoniously. "It is God's will."

Woods laid a restraining arm on him. "Wait. I'll radio for reinforcements. Colette will send some combat units along on the double-quick. They'll handle the mob."

"Do you think I'm going to be cooped up all my life behind bayoneted guns?" Boling demanded violently. He threw out his arm in an imperious gesture. "Open the doors."

The sergeant shrugged his shoulders and obeyed. The police drew their guns. The two soldiers thrust themselves in the fore. Slowly the heavy bronze gates swung open. A violent agitation, like the wind through a cornfield, swept the crowd. Countless thousands were tight-wedged. A deep murmur that rose in menacing volume and died abruptly into deathly silence as Boling and his associates presented themselves.

In the center of a close-packed phalanx, Boling, erect and unafraid, marched forward to meet the ominously silent throng. Like a living wall, tattered hungry people stretched in waves up and down the avenue.

Boling thrust himself from behind his thin curtain of defenders, put up his unwounded arm as though to clear a path through the mob.

"Boling!" someone shouted.

"Boling!" another took up the cry.

"Boling... Boling..." it echoed and reechoed through the crowded street.

Haynes squared his stooped shoulders. A surge of feral emotion swept his slight frame. He would go down fighting. Woods barked commands to his men. The sergeant said something under his breath.

Then suddenly, astoundingly, the people went mad. A thunderous wave, of "Hurrahs" rose crashing from the packed streets, a storm of whistling and cheering. A lane formed as if by magic, a lane through which Boling marched with fixed smile. His defenders, sheepish, astonished, made haste to thrust their weapons back into hidden holsters.

"Boling... Boling...!" The cheers ran up and down the crush of humanity, wedged solidly in the broad avenue. Hands reached out to touch him reverently as he passed, uplifted faces, etched with suffering and malnutrition, streamed with tears, invoked him as another god. It was a tremendous drama of mass-emotion. From skyscraper windows, black with bobbing heads, a snow of ticker tape drifted to the street level.

"Please get me a taxi," Boling turned a drawn, pallid face to the now smiling Haynes. "I feel weak."

Taking his arm again, Haynes piloted him through the joy-crazed crowd. It took two blocks of a seething sea of humanity before a parked cab could be found.

Boling's face was yellow, his brow damp.

"Climb in. Hurry!" he whispered. The driver slammed the door shut, kicked his engine into roaring life. It literally pushed its way through the shouting, hysterical people, fled down a side street, pursued by running hundreds.

Two hours later Haynes reached his Long Island home.

He had left Boling at his hotel, limp, barely conscious, in charge of a physician. Jane met him at the door with a hysterical sob of relief.

"Phil... you're all right... you are, aren't you?" She clung to him, running her hands up and down his arms as if to assure herself that it really was her husband.

"Why certainly, darling," he laughed. "Nothing has happened to me. See, I'm all right."

He led her gently into the living room, petted and soothed her until her convulsive shudders gradually subsided. Then she relaxed into his arms.

"I was listening to Boling's speech over the radio. I heard an interruption, threats, screams, and the sound of shots. I became hysterical, I suppose. I didn't know if anything had happened to you..."

"You weren't worried about Boling then?" he smiled down at her.

"No." She sat up determinedly. "Somehow I had a feeling that the world might be better off if he were dead. I don't trust him, Phil."

Haynes shook his head negatively.

"I think you are misjudging the man," he said slowly. "In any event the people are solidly in back of him." He recounted the scenes at the studio and in the street. "Today," he concluded solemnly, "Boling is in fact the uncrowned ruler of America. When we reached the hotel, the President himself was on the wire. He assured Boling that there would be no government interference with the Power Council."

"Why doesn't he abdicate at once and be done with it?" Jane asked indignantly.

Haynes smiled wryly. "He might as well," he agreed. "The country was on the edge of revolt. The people will not starve any longer. The President knows that Boling is the only man who can save the situation. He hopes that with Boling, he can retain at least nominal power." He sighed. "It's all working out as Boling planned."

"Then Boling was not sincere in his speech about abundance for everyone?"

"Absolutely," Haynes said positively. "He meant every word of it. But he also meant the rest; about ruling without interference. The President knows it too. From now on, the government will be a farce. It will take orders from the Power Council."

The telephone rang shrilly. Jane answered it. Her face clouded.

"It's Boling's doctor," she told her husband. "He must speak to you at once."

Haynes picked up the receiver quickly. "This is Haynes, doctor."

"Mr. Boling requests that you come to the hotel immediately." The doctor's voice sounded ominous.

"Why, what's wrong?" Haynes gasped.

"I can't tell yet. Mr. Boling is in a serious condition. He complains of voices and strange visions. I think you had better come right over."

Haynes placed the phone down dully.

"Boling wants me," he said to Jane. He patted her shoulder. "No, I can't stop to explain. An emergency of sorts. Don't worry about me."

The blue of the late spring afternoon had faded to a leaden hue. Angry red tinged the borders of great bellying clouds, the air was thick with uncanny prickling electric currents. As he hastened to the station, Haynes felt the little hairs on his body quivering upright under strong electric tension.

Almost instinctively his overwrought faculties connected Boling's new attack with the strange breathless atmosphere. It was ominous. Something horrible was impending, he was sure of that. He had a strange certainty that this cosmic dream, in which Boling and he and all the other gesticulating futile earth figures were mere marionettes, was fast approaching its climax.

He tried to laugh himself out of it, to clear his mind of the heavy overbearing weight it seemed to be staggering under, to tell himself that the atmospheric phenomena were merely the usual presage to a thunderstorm, that Boling's illness, this time, was due to his wound, exhaustion,—but he knew better. The passengers in the subway were all nervous, furtive, jumpy, as if they too sensed unutterable things.

The doctor met him in the anteroom of Boling's suite.

"How is he?" Haynes asked quickly.

"Better now."

"What was the matter?"

The doctor shook his head helplessly. "I don't know," he said frankly. "At first I thought it was fever induced by the bullet wound, but he ran no temperature." He looked around as though fearful of being overheard. He lowered his voice. "It struck me as being a similar condition to that which was epidemic after the electrical storms, except that this time he did not rave. He sat perfectly quiet, rigid, as in a trance, listening, answering something outside of himself in gasping monosyllables. He seemed to be struggling too, the veins on his forehead were corded and knotted, but he could not move."

"What were his words?" Haynes asked in quick anxiety.

"Just one word, repeated over and over. No!"

"Thank God!" The exclamation burst involuntarily from Haynes.

The doctor looked at him strangely. "Hmmmm. Maybe you're right. But you had better go in. He's very weak now, but lucid. And he's been asking for you."

He found Boling sprawled in an easy chair near the window, staring with tight drawn, haggard face out at the street. Haynes was shocked at the evidence of suffering depicted on the massive features, the limp trembling of the hairy hand offered to him.

"It's come; it's come at last," Boling whispered in fear-strained voice, his deep-set eyes burning as though they had looked into Hell.

"What's come?" Haynes asked with an attempt at lightness, yet with a horrible premonition that he knew.

"The price to be paid for the atomic motor."

Haynes started.

The words were tumbling from Boling now, as though he sought surcease from his agonies in speech. The floodgates of long months of repression had burst open.

"I did not tell you the whole truth about the motor, Haynes. I did not dare. You, everyone, would have thought me mad. It is true the idea came to me in my delirium. But there was more to it. I knew it was implanted in my mind deliberately; that I was chosen for some reason as the vehicle of communication with mankind. They had been seeking through thousands of minds for one that was suitable, and mine," his voice rose almost to a scream, "mine had to be the one."

"Who they?" Haynes hardly recognized the sound of his own voice, it was so harsh with strain.

Boling looked at him furtively!

"You'll believe me?" he implored.

"Yes."

"The Emissaries! he whispered. "I know them in my illness, if you can call it seeing. They came from God knows where out in interstellar space. Formless beings not human in our earthly sense of the word at all. In fact I got the impression that they were vortices of pure thought, electrical whorls in the ether, as unimaginably above mere human beings in evolution and in intelligence as we are above the lowest forms of bacteria. And even they, it seemed to me vaguely, were but messengers, Emissaries of some greater power existent in the depths of interstellar space whose bidding they do."

He shuddered and went on, while Haynes listened with mouth agape and brain racing wildly.

"They bored into my brain and communicated as by some mental telephone their commands. Tremendous vistas opened up to me. I saw these strange interstellar beings sweeping from world to world, from sun to sun, from universe to universe, in obedience to some vast overlord, hidden eternally in a space-time outside all the universes, proceeding methodically in accordance with some vast incomprehensible plan whose scope, it was imparted to me, my earth-bound brain could never hope to encompass."

Boling paused, and stared vacantly into space. To Haynes, rapt and silent, it seemed as though he had gone into a trance. This was not the customary speech of Boling, the practical man, who scorned the use of any but the plainest and most vigorous Anglo-Saxon words to convey a plain and vigorous meaning.

At length Boling shook himself awake with a start, and proceeded as though he had not ceased talking.

"Then," he said, "the idea of the motor was implanted in my brain. I was to invent it give it to the world in furtherance of their plan."

Haynes leaned forward. He was beginning to see the light.

"Did they demand that you form a dictatorship on earth and take over all power?" he asked eagerly.

Boling looked at him doubtfully. "No-o-o," he said "That was my own idea. Hell, man!" he burst out violently, "it was only fair that I get power in return for such an immeasurable benefit to the world."

Haynes nodded, satisfied. These Emissaries, these beings from interstellar space, had been uncanny in choosing their vehicle. Boling was ripe to their plans, whatever they were, without realizing in most part that he was only a vehicle.

"They came to you again today?"

"Yes." There was a crease in Boling's forehead.

"What did they want?"

Indecision spread over his face. "I wish I knew," he said worriedly. "They told me, all right, but it was something my mind rejected. I refused. When I awoke, not even the vaguest memory was left, except that I struggled with them, and they went away."

He brightened, and something of the old confidence came back to the man.

"I think I licked them that time. We'll keep the motor and not pay the price, whatever it is." He rose and shook a fist at the unseeing air. It was the old Boling again. "I'll never give in!" he cried.

Haynes shook his head pityingly. He held no illusions.

Boling strode to the window, stared out. Suddenly he fell back, eyes dilated, finger pointing.

"Look," he whispered.

Haynes was at the window in two jumps. Outside, barely clearing the roofs of the building, swirled a whirlpool of vapor. The rest of the sky was cleared, as though all the heavy clouds that had covered the heavens had been sucked into an unimaginable vortex. Even as they stared the vapor condensed and grew black. Its center, a rapidly rotating focus, flared into blue-white brilliance. Then the whole mass revolved more and more rapidly until the blaze of blinding light had formed a vast ball.

Tiny figures gesticulated upward from the street below, then broke into scurrying flight. Perspiration made little balls on Boling's forehead. "For God's sake!" he said, and with an uncontrollable movement ripped down the shade, fell shaking into his chair.

"What is it?" Haynes gasped.

"The Emissaries!"

Boling bent over suddenly, put hairy hands to head, and remained rigid. Little moaning noises burst from him, then strange incoherent sounds. He was struggling visibly, shouting defiance. Then a loud "No!" burst from him.

Haynes himself felt a sudden compressing force in his head, as though unbearable weights were being placed within. Sibilant whispers darted back and forth, every nerve cell seemed torn to shreds by thrusting fingers. A succession of startling confused images passed through his mind. He sat down dizzily.

Then, as suddenly as it had commenced, it was over. The pressure relaxed, Haynes felt as if the invisible forces had been removed. He opened his eyes in relief, saw Boling relaxing, limp, in his chair.

Haynes got up with an effort, thrust open the shade. The sky was an unclouded blue, not a vestige remained of the uncanny ball of flame.

Boling passed a weak hand over his forehead. Then triumphantly:

"I've beaten them again. They wanted me to do something, I can't remember what, but I know I refused. And they went away, defeated."

Haynes said: "I'm afraid. They're infinitely more powerful than you, than all of us. When they are ready to make final demands, you'll have to give in. I tell you I'm afraid." He burst out passionately. "For God's sake, Boling, let's destroy the atomic motor, free ourselves of obligation, lest something infinitely worse befall the world."

Boling stared at him. He had regained his abounding assurance; the seeming victory had been like a heady wine.

"You're talking nonsense, man," he said sharply. "Give up the motor, that means salvation to mankind, that means power to ourselves and our descendants! Ridiculous! I've worked hard to gain my present position, and neither Heaven nor Hell shall take it away from me. Twice I've beaten the Emissaries and I'll do it again."

And that was that. Haynes knew the stubbornness of the man. But his fears grew with the passage of the days. What price was being demanded, that even Boling in his subconsciousness was fighting against? For he saw with blinding clarity that it would have to be paid, whether Boling willed it or not.

These beings from outside the universe, what did they wish from insignificant earth, what vast plan were they enmeshed in? He sighed. Time alone would tell. But he went back to work with a heavy heart. No longer did the atomic motor seem like an open sesame to a bright particular future for the human race. Immeasurable outside forces had intervened. One thing Haynes felt dimly. These strange vortices of thought, these denizens of space, were neither good nor evil in our accepted sense of the words.

To quote Nietzsche, they were "beyond good and evil." There would be no petty malice, nor spirit of revenge, nor deliberate destruction, in their handling of tiny earth, but at the same time the terms justice, mercy, pity, kindness, would have no place in their concepts. They would prove inexorable, undeviating, in the working out of their cosmic plans, regardless of what it meant to the strutting inhabitants of earth or the little speck of dust on which they lived.

A WEEK later Boling requested that Haynes leave immediately for Europe to tie up the great Continental industries with the Power Council.

The man was once more his vital, domineering self. There had been no further visitations from the Emissaries. The Power Council's grip on America had tightened to an absolute dictatorship. The President took orders with pathetic eagerness, grateful to be left with the shadow of office. Congress had been disbanded, together with the State's Legislatures. Only purely local governments were left with a modicum of authority. Woods was Commander-in-Chief of the American forces, as well as of the highly trained, ruthless private army of the Council. Biggs was Attorney General and Supreme Court rolled into one.

Those industries that refused to come under the control of the Power Council were relentlessly harried out of existence. Rival establishments sprang into being, powered by the atomic motor. Their products were undersold at far below cost, raw materials were refused them, governmental restrictions hampered them at every turn, until they were forced to bow to the inevitable.

"They are eating out of our hands," Boling said satirically.

"But you don't expect the opposition to take it lying down," Haynes protested, "There are still powerful interests here and abroad that will fight us to the last ditch."

Boling's answer was characteristic. When the newspapers screamed defiance, he had the President declare a state of emergency, and clamped down with strict censorship. When recalcitrant industrialists incited open armed revolt, Woods struck hard with his private army. Swift, stern retribution, ruthless hunting down of the rebels, wholesale executions, made the army of the Power Council a thing of dread. There were no loose ends when they mopped up a job.

Yet what was more than anything else responsible for Boling's rocketing into power was the enthusiastic acquiescence of the people. He made good on his promises. In the Council's factories, the atomic motor made labor easy. Products flowed in unending abundance; rigorous distribution made certain that every employee had not only the necessities, but a good deal of the luxuries of life.

The people wallowed in unaccustomed abundance. For long years they had starved and suffered, now they could eat and drink to bursting without thought of the morrow.