RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, March 1936, with "Entropy"

Then, unmistakably, hoar frost caked in filigree

patterns, exuded steamy vapors into the June atmosphere.

A gripping science novel which concerns the timelessness of force.

IT WAS a small but select audience that gathered in Jerry Sloan's laboratory that late June afternoon. They filed in with murmured words of greeting and swift, appraising looks at the young man who had maintained with unseemly positiveness that all their lives of laborious research had been along radically erroneous lines.

He stood up well under their cold scrutiny, however. His keen, alert face showed no signs of his inward perturbation; his gray eyes twinkled gravely at the veiled hostility with which these world-famous physicists shook his hand.

"Whew!" Jerry whispered to the girl who stood a little to one side and just a trifle to the rear, as became a laboratory assistant in the presence of her chief and betters. "Did you see the glare with which old Marlin favored me?"

"You can't blame him, can you?" she retorted. "He's just solidified liquid helium, and proved by intricate mathematical formulas that he has approached within several thousandths of a degree of absolute zero. He has also announced that it is impossible to achieve lower temperatures. Then you come along and tell him he's all wrong. That it not only is possible, but that you can do it. Furthermore, you add insult to injury by questioning the whole expansion-contraction, ammonia-liquid oxygen cycle as the proper method for getting extremely low temperatures. After all, Marlin and the others are only human."

Kay Ballard was an extremely pretty girl, thereby disproving once and for all the ridiculous old maxim that brains and beauty do not mix. Behind her impish smile and warm, dancing eyes was a cool, steady mind which by native brilliance and adequate training had proved of invaluable assistance to Jerry Sloan. Not that he didn't appreciate also the impish smile aforesaid, the dancing eyes and the peach blow of smooth-textured skin. Quite the contrary. As a matter of fact—but that is neither here nor there for the moment.

"I suppose not," Jerry admitted. Little creases of worry had suddenly appeared on his forehead, and a harassed look on his face. The last of the invited guests had entered the laboratory, and they were alone in the anteroom. "That's what will make it all the worse if the experiment fizzles. I should have waited another month, made all my preliminary tests first."

"It can't fail," Kay assured him encouragingly. "We've gone over the mathematics of it time and again. It's air-tight."

Then, with fine feminine in-consecutiveness, she burst out indignantly, "It's all the fault of that old buzzard, Edna Wiggins. She had no right to force you on with a public announcement just because the endowment year was up."

"She's paying the expenses," Jerry reminded her softly, "and she can call the tune. Besides, Marlin has made her jittery about me. Maybe I'm only a four-flusher."

Kay shook her brown bob defiantly. "A lot she knows about science," she declared. "It's the publicity she's after. Mrs. Wiggins, widow of the late beer baron, the eminent bootlegger, patroness and endower of the arts and sciences. She's afraid now she's backed the wrong horse. The old buzzard!"

"Sssh!" Jerry warned. "Here she comes now." He raised his voice. "Good afternoon, Mrs. Wiggins. We were waiting for you."

A HIGHLY uniformed chauffeur had preceded her, stood with heels clicked and hands stiffly at attention. She waddled in, fat, indeterminate of age, dressed lavishly and expensively, yet in extremely bad taste. Kay's unflattering characterization was apt, Jerry thought, as he forced cordiality into his voice. In spite of the gross breadth of her body, her face was startlingly hollow and leathery, with sac-like pouches hanging from her scrawny neck and a fierce, predatory nose overshadowing all her features.

"Good!" Her thinnish head was like a pendulum bobbing on her enormous bulk; her voice was hoarse and mannish. "That means I won't be wasting my time. I've an appointment with my beautician at six sharp."

Her beady, glittering eye passed disapprovingly over the trim youthfulness of Kay—she had argued vehemently with Jerry on the question of young lady lab assistants, but on that point Jerry had been adamant—and pierced her unhappy protégé with hostile regard.

"I've spent a hell of a lot of money on this idea of yours, young man," she went on inelegantly, "and I expect results to-day. Show those fellows you invited that you've got the goods, and I'll stake you to a cool million. The Edna Wiggins Foundation, hey? But if you can't——"

"I wanna go to the movies. I don't wanna stay in this stupid old place." The little boy, about eight, whom she had towed in, half hidden behind her billowing form, darted from behind, beat at her with small, angry fists. His sullen face was distorted with anger.

"There, there, mama's precious," his mother cooed. "Mr. Sloan's going to show you something just as nice as the movies."

But mama's precious kept on howling. "I don't like him and his silly experiments. I wanna see a movie. That's fun."

Jerry and Kay exchanged glances. The young physicist shrugged. Under his breath he swore. If ever there was a spoiled brat whose neck he'd like to wring, it was young Egbert Wiggins. His doting mother dragged him everywhere, and several times there had been near catastrophes in the laboratory because of his darling little ways.

For the moment Jerry was tempted to throw the whole thing up, tell the great Edna Wiggins a few plain, unvarnished truths, but that would mean the end of his work, the end of all his scientific dreams. So he ground his teeth, put on his best smile, and ushered his benefactress and her still-squalling brat into the main laboratory where the assembled physicists were inspecting the complicated apparatus with intense, albeit somewhat skeptical interest.

Kay brought up the rear, shaking her shapely fist with a certain vicious intensity at the unsuspecting backs of mother and son.

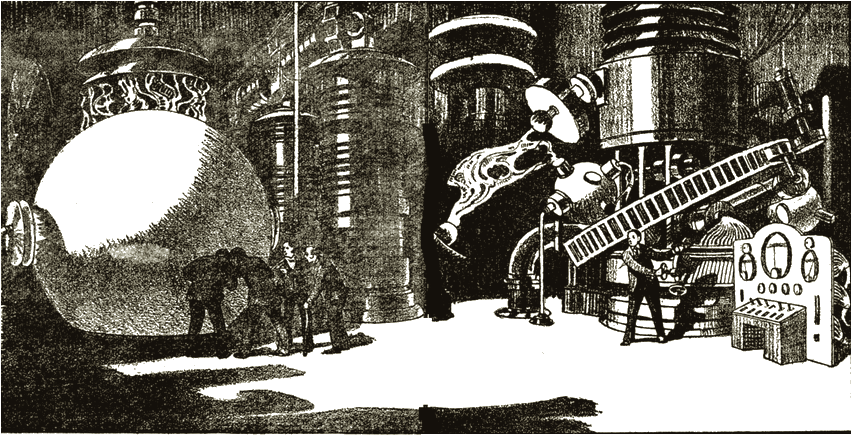

The apparatus was well worth close attention. In the very center of the great room, poised in a cup-like depression within the floor, was a hollow crystal ball of some fifteen feet in diameter. Its transparent substance held a bluish tinge. Within, slightly magnified and irradiated by the distorting medium of the crystal, were various articles: An iron bar; a chair of carved wood; a small glass tank filled with water; a loaf of bread; a smoked ham, suspended by cord from a hook embedded in the crystal wall; a cage with a tiny white mouse; another with a frightened, fluttering canary.

Thrusting with somber solidity at the sphere from either side were two huge magnets, composed of the new nickel-chrome steel that possesses remarkable magnetic powers. Coils of infinitely fine strands of copper wire wound around their bar lengths, and connected by thick cables with the panel switchboard on the farther wall.

Around the sphere, hemming it in at equidistances of five feet each, were what seemed to be gigantic parabolic reflectors, suspended from the ceiling or supported by floor stands with flexible jointed stems. Even underneath, through the transparency of the sphere where it poised in the hollow, could be seen a reflector pointing upward from the cellar.

"We're ready to begin," Jerry declared, taking his position near the switch panel.

The assembled audience stirred, leaned forward. Every man was a famous scientist; most of them were specialists in low temperatures. Except for Marlin, whose published article Sloan had contradicted, the rest were open to conviction.

Mrs. Wiggins had waddled to a seat in the front row, somewhat annoyed that these men of science had not done more than utter perfunctory words of greeting at her entrance. She compressed her fat lips, glared belligerently. She had been a fool to mess around with cold-blooded brutes like these, who didn't appreciate her hard-earned money or the graciousness with which she lavished it on them. Now if they had been artists and poets——

The boy, Egbert, wandered unnoticed in the rear of the laboratory, touching strange machines with possessive fingers.

"THIS apparatus," said Jerry, "represents an entirely different method of solving the problem of extremely low temperatures; yes, of absolute zero itself. I grant you that the expansion and contraction method and the employment of liquid oxygen has been remarkably successful; so successful in fact that my good friend, Professor Marlin, has attained the astounding low of only a few thousandths of a degree above the absolute in solidifying the inert gas, helium."

Marlin's hatchet face, hitherto flint-like in its unreceptiveness, relaxed slowly. A faint smile of gratification flickered over his countenance. Jerry grinned to himself and went on:

"But, by the very nature of the process, as Professor Marlin has truly indicated, it is impossible to go any farther. Yet it is in that small few thousandths of a degree that science is tremendously interested. For solid helium, just like liquid oxygen, exhibits all the normal, usual properties of matter."

"And why shouldn't it?" some one asked.

"Because of the very nature of heat and cold," Jerry retorted. "Theoretically cold is merely the absence of heat. And heat is merely a form of energy; the energy of matter in motion. Increase the speed of molecular vibrations within any material body, and you increase the heat of that body. Decrease their speed, and by the same token their energy emanations are lessened, and the body becomes 'cold.' Theoretically again, the absolute zero is achieved when the molecules cease all vibration, when they remain quiescent, possessing potential rather than kinetic energy."

"Elementary, young man!" Marlin snorted. "We all know that. We also know it is impossible to reach this absolute."

His compeers nodded. Mrs. Wiggins simply glowered. She didn't quite understand all this talk, but she sensed that the assembled great men did not think much of her protégé—as she described Jerry Sloan to friends and reporters. Her jaw set ominously. A solid hundred thousand bucks wasted, and instead of respectful publicity for herself, the result might prove a boomerang. She caught Kay's eye and glowered indignantly at the girl. How could anything turn out properly with a hussy like that on the job?

Kay glowered back with interest. "Old buzzard!" she mouthed, half audibly. The epithet was cleansing for her soul. She knew, with sudden fierce fear, that Jerry's life work depended on the next few minutes.

But Jerry Sloan went on easily, outwardly unperturbed. "By the old methods, Professor Marlin, you are, of course, right," he pointed out. "I've attacked the problem from its logical angle. Absence of molecular motion means absence of heat. Therefore, the thing to do is to stop the molecules in their paths, bring them to a halt. I've done that!"

NOW he had his sensation. The scientists half rose from their chairs, expostulating, arguing. "Impossible! Incredible !" rose from all sides.

"Not at all, gentlemen," Jerry said quietly. "Look at this apparatus of mine. The crystal sphere is made of tourmaline. Now tourmaline possesses a very peculiar property. It can polarize light; that is, transmit light waves which vibrate only along a particular plane. That means, of course, that the tourmaline molecules lie along parallel axes and vibrate in definite planes. Those supermagnets will force them into the positions I require."

Jerry pointed up at the reflectors. "Those are not reflectors, of course. They are the focuses of very powerful streams of impulses, of extremely minute wave lengths and alternating with a rapidity that I have been able to synchronize exactly with the period-of vibration of the tourmaline molecules. Their polarization, naturally, simplifies the problem. Their movements are not haphazard as in ordinary bodies, and can be accurately determined."

"But I still don't see what you're driving at," Marlin exploded.

"I haven't finished," Jerry said patiently. "I time my impulses to lock in with the vibrational periods of the tourmaline. Trough of impulse against recession of molecule; crest of wave against progression. In other words, I am damping the vibrations, providing push-pull resistance, interposing perfect interference. The result is obvious. The molecules are slowed up; their kinetic energy, instead of being dissipated, as heat, is locked up within their bosoms as positional energy; in other words, potential static energy. When they come to an absolute halt, we then have absolute zero."

Professor Marlin permitted himself a bleak smile as he looked around the circle of his confrères.

"The theory of what Mr. Sloan is trying to do is simple enough, my friends. But"—he paused impressively to allow that to sink in—"putting it into practice is quite another matter. Ha! ha!"

Kay colored furiously. "The old fool!" she gritted between her pretty little teeth. "What does he know——Jerry, show him; show them all!"

But the others had not joined the booming mockery. Perhaps this young fellow had something. So they just sat and waited.

"In another minute you will see the practice also," he told Marlin evenly. "All right, Miss Ballard."

The girl moved to the magnets, threw a switch. Nothing happened, yet every one knew that tremendous magnetic stresses were exercising polar attractions on the crystals.

"Why is that queer array of objects inside the globe?" queried Dakin, authority on gas pressures.

"Simply to get the effects of low temperatures on as wide a variety of materials as possible," Jerry explained. "Now I'm going to turn on the juice." He moved a lever slightly over a rheostat arrangement. A soft, blue light glowed in gigantic, concentric tubes; the atmosphere was suddenly filled with the pungent odor of ozone as the reflectors glowed with brilliant pin points of flame all over their shiny parabolic surfaces.

Thousands of volts of invisible radiation, oscillating with unimaginable rapidity, hurtled from the reflectors and lashed with incredible force upon the crystal globe and all its contents.

A TENSE silence held them all in thrall as they leaned forward to see what was happening. Even Mrs. Wiggins stared with goggling eyes, vaguely impressed by the blue, lambent fires and the soft roaring of the machines. She forgot her son was there. The others had forgotten him long ago.

Egbert, however, was bored with the display. His sallow face was set in sullen lines. He wanted to go to the movies. He looked surreptitiously around. No one was watching him. His hand groped along an expensive galvanometer, pulled. Wires ripped away. An evil glee invaded his being. This was fun! Softly, he moved along the rear of the laboratory, pushing levers, jerking wires, twisting knobs, ruining thousands of dollars' worth of equipment.

Meanwhile the physicists sat back in their seats, disappointed. Nothing seemed to have happened. "Well?" queried Marlin, faint triumph in his voice.

Jerry smiled. "Look at the bolometer," he suggested.

A thermo-couple, attached inconspicuously within the interior of the globe, registered electrically on an ammeter displayed on the panel board. By means of an ingenious contrivance invented by the young physicist, the current flow was converted into direct temperature readings.

The needle pointed boldly to two degrees Centigrade, only a trifle above freezing point. Yet the room temperature was almost twenty-seven degrees.

Marlin snorted skeptically. "Bah! What does that prove? Your high voltage alone, by ionization, by absorption of heat in expansion, could be responsible for a slight drop in temperature. I've solidified helium and you show me the freezing point of water!"

Jerry grinned engagingly. "I've only started. I'm doing this step by step. Watch!" Again he moved the lever—another notch.

The canary within the tourmaline ball stiffened. The bright-eyed mouse shivered. A vague film breathed like a giant's breath over the clear transparency of the sphere. It spread rapidly, thickened, obscuring everything within. Then, unmistakably, hoar frost caked in filigree patterns, exuded steamy vapors into the June atmosphere of the laboratory. As one man they craned toward the bolometer.

The needle quivered at minus forty degrees Centigrade and was swinging farther to the left with little spasmodic jerks. A long suspiration lifted from the absorbed physicists. This was becoming interesting; decidedly so!

"Show our guests what is happening inside, Miss Ballard," Jerry said placidly.

Kay nodded, picked up a flat knife from a table and diligently scraped at the smooth surface of the icy coating. It flaked away in long, solid crystals until a sufficient area was cleared to give an unobstructed view into the interior.

Both the mouse and the canary were rigid and immovable in their respective cages. The tank of water was a naked cake of ice; the glass container lay in a thousand shards around it, shattered by the expansive thrust of the congealing water.

The bolometer now read minus one hundred and twenty degrees Centigrade.

"Good Lord, man!" Dakin exclaimed suddenly. "You're getting there." Murmurs of assent drifted upward from the others. All except Marlin, who remained stubbornly aloof. But Jerry, outwardly placid in his moment of triumph, was becoming increasingly anxious. His careful, preliminary experiments had been abruptly cut off by Mrs. Wiggins' idiotic insistence on immediate publicity. He had never tried it out beyond the boiling point of liquid air. What would happen after that?

The needle was accelerating on its downward grade. The room was perceptibly chilling. Wallace, the frail-looking chemist, shivered. The hard coating of frost was glassy now, transparent. It was too cold even to cast off steam or vapors. Within the sphere a colorless fluid condensed in a fine drizzle, rolled in a little puddle at the bottom concavity.

Startled eyes swerved to the bolometer. It stood at minus one hundred and ninety-five.

"Yes, gentlemen," Jerry remarked. "That is liquid air you see. The gaseous atmosphere is completely gone. Fortunately the tourmaline is thick enough to resist the outside pressure created by the vacuum within."

Kay stood close to the globe, exultant. It was cold, but she did not mind. The fierce glow of the electron tubes, the sparkle of the reflectors as they hurled their synchronized beats upon the globe, were no stronger or brighter than the happiness in her heart. Jerry had shown them, had stifled their sneers. Already the needle wagged closer and closer to the absolute zero. Minus two hundred and seventy, just below the liquefying point of helium.

NO ONE moved; no one stirred. The whine of the machines rose in the frozen air; they sat with lips parted. Minus two hundred and seventy-one! Minus two hundred and seventy-two! Almost two hundred and seventy-three, the absolutely zero of all temperature! The needle slowed, quivered, held fast. That last few thousandths of a degree, magnified on the scale to perceptible dimensions, seemed an insurmountable barrier.

Marlin's voice was explosive with relief. "A very excellent machine, Mr. Sloan. A very fine method of achieving low temperatures. But—my thesis is still unshaken. You cannot gain the absolute zero. By the very nature of things you cannot. You have proved my point."

Kay flushed. "But he can, Mr. Marlin," she cried out. "Look! The rheostat lever is over only part of the way. The last notch represents full power, perfect synchronization. Go on, Jerry. Show them!"

Jerry Sloan shook his head. "No," he stated in flat tones. "I haven't tested that phase yet. I don't know what might happen. Within a month I'll know more about it."

"I'll tell you now," chuckled Marlin. "Nothing; absolutely nothing. You've reached the last outpost, the same as I did. Your method is new and ingenious, but it adds nothing to the sum total of knowledge."

Mrs. Wiggins woke with a start at that. This was something she could understand. Professor Marlin was internationally known; he had just said young Sloan's experiment meant nothing.

She rose wrathfully from her seat. Her voice was shrill, excited. "So this is what I spent a hundred thousand on! An experiment that means nothing. You worked on my good nature, on my generosity, with lies, lies! You're a fraud, a cheat!"

Jerry flushed. His hands clenched, unclenched. If only she were a man! "Now listen to me, Mrs. Wiggins," he said miserably. "I didn't promise miracles. I wouldn't be a scientist if I did. But I have discovered something extremely important. It's just that I must have time to make certain that nothing goes haywire; that——"

The bootlegger's widow threw her fat arms wildly toward the others. "Listen to him!" she shrilled. "He wants time. Time! Always he tells me that magic word—time! On account of that I spent a hundred thousand; on account of that he wants still more. Show me now!" she clamored. "Or I'll take every bit of stuff out of here. I'll sell it, get what I can to make up my losses."

Her make-up was streaked; her eyes glared. She was beyond reason. Jerry gritted his teeth, started for her. "You wouldn't dare do that," he said very low.

"Oh, I wouldn't!" she exclaimed, appealing to the hushed physicists. "Listen to him. A beggar that I made into a scientist. He robbed me of a hundred thousand and he tells me I don't dare!"

The men shuffled uneasily, embarrassed at this strange woman's stranger outburst. They avoided each other's eyes, avoided especially the tense figure of Jerry Sloan. Even Marlin was abashed. Dakin started to expostulate mildly, found the woman's torrent of words too much for him, and muttered vaguely something about an important appointment he must keep. He really must be going. Really! No one heard him.

Kay gripped the edge of the table with white-knuckled hands. "You old buzzard!" she cried. "You and your filthy money! You ought to thank God you were able to give it to Mr. Sloan for his work. That's the only way you'll ever be remembered."

The frantic woman swung her ponderous form around. "Buzzard!" she wailed. "She called me a buzzard! Me, Edna Wiggins, worth ten million cold plunks. That hussy called me——Oh! Oh!"

Kay was angry clear through. She had cleansed her soul, made up for all the petty insults, the little tyrannies of a year's politeness. But she was also frightened. By her outburst she had sealed Jerry's fate irrevocably. That vindictive old woman would never forgive; would put her threat into merciless action. Kay quivered almost against the frozen surface of the sphere. The cold pierced her marrow, chilled her flesh, but she did not feel it.

JERRY, white with rage, left the panel board, strode purposefully in the direction of the woman whose filthy money had financed him. He'd be damned if he'd let her get away with that; and he'd be triple damned if he'd be pushed into an experiment of which he had no present way of telling what the results might be.

Mrs. Wiggins was on the verge of a spectacular faint, and the men, great scientists though they were, knew nothing of feminine tantrums. They were alarmed, crowded around her with fumbling assistance.

So it was that no one saw Egbert Wiggins. That young scion of beer and millions was not interested in his mother's tantrums. He had seen plenty of those before. But he had successfully ripped away all the wires he could find in the rear of the room, had had a swell time pushing buttons, swinging knife edges. Nothing had happened, though. Therein he was vaguely disappointed. Nothing spectacular, nothing that would focus attention on himself. He loved that!

His too-sophisticated eyes swung around the room for new worlds to conquer. They lighted up suddenly. That lever now—how temptingly it rested in its notch. He made his way stealthily toward it, gloating in anticipation.

Jerry, grim and hard of jaw, was pushing his way through the clustered scientists, toward the shrieking woman in their midst. Kay, aghast at what she had done, shrank even closer to the great sphere.

"Now you listen to me," Jerry commenced, biting his words sharply.

Young Egbert pounced upon the lever with triumphant haste. His small, grubby fingers tightened, swung hard toward the right. As far as it would go. The great tubes flared into blinding blue streaks; the soft whine crescendoed to a howling roar. The reflectors blazed with crackling energy. A million volts seared and crashed into the ice-covered sphere. Within, liquid air was solid air; a tiny globule of helium became nodules of frozen gas. The ham fell with a splintering thud as the tortured cord, brittle beyond all imagining, snapped in two.

The boy, frightened at the blaze and the noise, howled and scurried for dear life to the farthest end of the laboratory.

Kay swung around, cried out in fear. The frosted crystal was opening, dissolving before her very eyes. Inside, mouse, canary, chair, bread, ham, water, became vague, indistinct, shifting from hard solidity to a nebulous tenuosity, behind which the machines and walls of the laboratory wavered and grew momentarily clearer.

The girl's desperate eyes swerved to the bolometer. The needle was tight against absolute zero. Then, suddenly, as thermo-couple misted into nothingness within the globe, the needle sprang back to twenty-five degrees Centigrade. Room temperature!

The next instant it happened!

Kay felt the sudden tug, heard the howling noise that enveloped her. With a great cry she threw herself backward. But it was too late——

THE NOISE, the increased flare, the wail of Egbert, Kay's scream hard on its heels, caught the milling group, pushed them around in gasping astonishment. Jerry, halfway through the group, pivoted, saw the incredible event just as it happened. With a snarling oath he lunged forward, bowling the physicists out of his way, fear like a great hand clutching his heart.

The huge swoosh of air caught him as it did the others. It roared like an express train pounding along steel rails; it swirled with cyclone force; it scattered heavy instruments like chaff in its path; it knocked men right and left like ninepins; it picked Jerry off his feet, smashed him into a heavy chair, sent him stunned and bleeding to the floor.

In that second of screaming madness he saw everything to the last startling, crazy detail. The great tourmaline sphere had opened into nothingness. The interior was a phantom, tenuous outline, a vague blur of ghostly matter. The walls of the laboratory were solid behind. Kay's body, slender, resilient, was curved like a bow, convex toward the sphere, as if she were being pushed by irresistible forces. Terror and strain were on her face; her lips were parted in a dreadful cry.

Then, even as Jerry smashed headlong into the chair, he saw the girl catapult toward the misty globe, pass without a stagger, without a jar, through what had been inches-thick tourmaline walls, clear into the center of the nebulosity.

They saw the girl catapult toward the misty globe, pass

with-

out a jar, through what had been inches-thick tourmaline—

While Jerry sprawled and slithered in frantic attempt to heave himself erect against the rush of air, his horror-struck eyes held on those of the girl. There was surprise, something else within their depths. Her mouth moved as if she were shouting, but no sounds came. Then her eyes widened, and her body, exposed to the still-rushing waves of force, seemingly suspended on nothingness, began to blur. The sphere was gone, vanished; so were the objects Jerry had placed within.

Then Kay Ballard, too, was gone, vanished, like a clap of thunder, like lightning that had blinded with dazzling flare and become utter night again. The cyclone died down as suddenly as it had come; the confused cries of the men, the toneless shrieks of Mrs. Wiggins no longer faked hysteria, the half-frightened, half-gloating wailing of young Egbert, muted into hushed silence.

Jerry was already pounding across the room, hurling the lever back to zero position. A million volts seared and died; the tubes went dark and the reflectors quenched their light. Then he whirled, dived for the place where the tourmaline sphere had been, where Kay had stood, incredibly within its closed interior.

The wild frenzy of his rush carried him over the smooth expanse of floor; his sudden, frantic leap cleared not an instant too soon the pit in which the globe had rested. His hands extended in vain to brace himself against solidity, against a mass that must be there.

He crashed through thin air, went staggering with the momentum of his body toward the huddled group of men. Edna Wiggins had fainted in earnest, but no one paid her any attention. Young Egbert thought it time for him to be going. He quietly eased himself out of the room, raced for the waiting limousine, and stampeded the highly uniformed chauffeur into instant flight for the Park Avenue penthouse that was more Renaissance palace than home.

"My Lord!" said Dakin over and over again. It was incredible, impossible! Not a minute before there had been a solid, substantial globe, a girl of extraordinary charm and beauty; and now—there was only the stark emptiness of the floor, the huge magnets thrusting at nothingness, the gigantic reflectors enringing a sphere from which all substance had fled.

Clamor rose again; shoutings, confused questions bordering close on panic.

"For Heaven's sake, man," screamed Marlin, "what have you done?"

But Jerry was beyond hearing. Grim-faced, desperately, he was swinging from machine to machine, reversing levers, shifting processes, slamming waves of heat into the silent space, trying with every resource known to science to undo that which had been unwittingly done. The sweat poured in little streams from his body; the temperature of the room grew to furnace-heat, but nothing happened. Both tourmaline sphere and Kay Ballard were irretrievably gone!

IT was Dakin, kindly and spare of build, who forced him to quit his frantic efforts. He led Jerry gently to a chair, saying: "Don't take on so, Sloan. It wasn't your fault. You had refused to be stampeded into an experiment which you hadn't checked in advance. It was that young imp of Mrs. Wiggins' who was responsible for the tragedy. Pull yourself together, man. We'll have to think this thing out clearly."

Jerry stared with haggard, hopeless eyes at the mocking sphere of vacancy. "I should have known," he cried fiercely. "I should have been prepared. Kay! Kay!"

There was danger of madness in the terrible agony of this young man, thought Dakin. Evidently he had been deeply in love with his very personable young assistant. Poor girl! What a dreadful fate! To disintegrate and vanish like a puff of smoke before their very eyes. Dakin shuddered, pulled himself together. And, being wise in the ways of human nature, he adroitly turned the subject.

"But, my dear Sloan," he protested, "what did actually happen?"

Jerry swung on them all, taut, bitter. "Don't you see?" he cried. "I should have known; all of you should have sensed what was coming. I succeeded, only too well. I stopped the swiftly moving molecules in their tracks.

I stopped the swifter atoms themselves, the very electrons, in their orbits. Motion died, and absolute zero of temperature was a reality, perhaps for the first time in the history of the material universe."

"But why," submitted Marlin in hushed bewilderment, "did everything—uh—vanish?" He had lost his arrogance completely.

"A very elementary proposition," Jerry said with fierce contempt. "When motion ceases, matter—visible matter—must die with it. What are the solid-seeming substances we see? An extension of extremely rapid movement. Nothing else. The diameter of the average molecule is two one-hundred-millionths of an inch. Tremendously below our range of vision. We see them in the mass only by the extension of their speeds. And the electrons themselves within the atoms have also stopped. Their diameters are 4x10-13 centimeters. Inconceivably tiny. Stop their motion and matter, as we know it, vanishes. The interior volume of an atom is a vast globe of emptiness. Jeans has represented it as several wasps buzzing around in the tremendous void of a Waterloo Railroad Station in London. You see the wasps while they fly. Search for them when they hang motionless on walls or ceiling, and the task is futile."

His eyes clung desperately, hopelessly, to that void within the circumscription of the reflectors. "She is in there," he said, pointing, "even now. Yet for all we can do, she might just as well be outside the universe, in another space, another time."

Bellew, a small, dapper man, whose specialty was thermodynamics, spoke up. "You applied heat to the area. The energizing waves should have been absorbed by the moveless electrons, kicked them back into vibration. In other words, we should have seen the—ah—vanished substances, even though"—a faint tremor passed over him—"they might not be—ah—exactly in the same form in which they vanished."

Jerry shook his head tragically. "Millions of volts went into stopping them, into locking up their energy of motion. Each electron, each proton, is a closed cycle of potential energy. I tried reversing the process. I increased the voltage. The impulses should have done what you say. But they haven't. Either the closed cycle is a stable state which no power we possess can change, just like a spring-lock door which requires only a slight shove to close, but once closed cannot be opened again without huge exertions of force—or else——"

He sprang violently from his chair; it went crashing. His eyes flamed. "By Heavens, I think I've got it. What I had said before at random. Our space time is an attribute of matter. Without matter our universe fades and becomes insubstantial. But matter is also an attribute of energy, which is motion. The electrons, protons, what not, lost their kinetic energy. They no longer exist. Or rather, the space time in which they were wrapped, the space time with which we are familiar, has ceased to exist with relation to the tourmaline sphere, and—and—" He bogged at the mention of Kay's name. It stuck in his throat. The others carefully averted their eyes at his grief. With an effort he stumbled on:

"Perhaps they—she—are in an entirely different order of space time, a new universe, occupying that space, yet infinitely remote. Perhaps, even, they exist in that strange dimension, live, move and have their being, just as——"

His lean jaw tightened into hard knots; his face grew grim with an intense resolve. He was speaking to himself now, softly, as if the hushed men in the room did not exist.

Edna Wiggins was coming to, making huge moans, but no one even flicked an eyelid in her direction. All eyes were fixed with unbearable intensity on the young physicist whose loved one had vanished into thin air.

"Of course," Jerry whispered to himself, "they are a vacuum in our universe. That was why the air rushed in with such force. She is still there, and I—I am going after her."

Dakin put his hand timidly on the young man's shoulder. "You don't know what you're saying. Perhaps a little sleep——"

Jerry laughed harshly. "I am not crazy, if that's what you mean."

"But how——"

"The same way Kay went," he answered promptly. "I'll build another sphere, repeat exactly what has happened by accident to-day. I—I think I can bring both of us back to this spacetime existence. If not—" He shrugged, and fell silent.

They stared at him in awe, these scientists, practical, efficient men, not given to sentiment or display of emotion. "Greater love hath no man than this that——"

Bellew broke the insupportable silence with a matter-of-fact objection. "Granting even your theory, Sloan, granting even you can find the sphere in that other universe, Miss Ballard is dead, irretrievably so. No human body, no life as we know it, could survive the intense cold to which she has been subjected. A man frozen to death remains dead, no matter what is done to restore the energy of his component molecules."

"That is only because the process of freezing was long continued," Jerry responded. "The organic molecules had time to change chemically into other forms, shift their mutual positions. That is not the case here. The whole damnable affair took only a second. Every molecule, every atom, every electron, was stopped in its tracks. There could not have been any relative change of position, of form."

They argued it out until voices were hoarse, and tempers exacerbated, but nothing could be done with Jerry. It was suicide; it was worse, they said, until finally they had to give in to his dogged, stubborn determination.

Mrs. Wiggins, wide awake now, and thoroughly cowed at the disaster her darling child had brought upon them all, hysterically agreed to furnish the sums necessary to repeat the experiment. Provided, of course, there would be no prosecution of her precious brat, no damage suits, to which Jerry agreed. As if, he raged, all the money in the world could compensate for Kay Ballard.

A WEEK passed. A week of driving furious energy. Jerry Sloan was already a man wrapped away from the world, of things as they are. He neither slept nor ate nor seemingly tired. Workmen scurried with frightened celerity at the harsh whiplash of his voice; the laboratory seethed like a spouting volcano. Jerry was a monomaniac, a man possessed of a single, driving idea. Faster, faster, forging on with insane energy. His cheeks hollowed; his eyes fixed on far-off things.

The image of Kay Ballard never left his haunted vision—that last terrible scene as, with outthrust, imploring arms and look of startled surprise, she faded from the universe of familiar things.

Jerry held on to that desperately. She must be alive—if life it could be called—in a new dimension, a new existence, waiting for him to follow and resale. He permitted himself no other thought, else he would have gone mad.

Edna Wiggins stayed discreetly out of sight. Young Egbert was shipped to an expensive private school in California—as far away as possible. Nightly, Mrs. Wiggins dreamed that the police were coming for her darling brat to drag him into durance vile, and she woke in sweaty fear. Thus it was that she signed checks for Jerry's work with feverish haste, not stopping to argue or quibble over vouchers.

Forbes Dakin stuck loyally by Jerry. He assisted, advised, expostulated that the hollow-eyed young man get sleep, take nourishment; subtly he tried to dissuade him from his crazy venture. To Dakin, as well as to the others, it was deliberate suicide. But Jerry was deaf to all entreaties. Kay was out there, in the infinite, calling to him, waiting with the growing fear that he would never come. It drove him on to even more tremendous labors.

Finally, a new tourmaline sphere rested in the floor hollow within the circumscription of magnets and parabolic reflectors. Inside its clear depths hung a ham; a white mouse gibbered and squeaked; a canary ruffled its frightened feathers; a chair stood in the accustomed place; water filled a tank; bread; iron; everything was exactly and meticulously the duplicate of that first ill-fated sphere. Jerry had tried to reproduce to the minutest detail the material equipment, the sequence of events.

"The timing, the power we are to use, even that last quick jerk of the lever, must follow exactly what happened before," he told Dakin, who had consented, albeit reluctantly, to set the switches and the rheostats. "With similar forces and similar masses, the chances of my finding Kay are so much more likely."

Dakin nodded wearily. He was frightened, now that the zero hour had come, but it was too late for him to back out. One look at Jerry's burning eyes and grim, set face showed that.

Dakin took his place at the panel board. Jerry stood near the magnet switch, even as Kay had done. The routine was carefully gone through. He sent the juice surging through the magnets, waited for polarization for five exact minutes.

Then Dakin set the rheostat lever in the first notch. The blue lights glowed again in the concentric tubes; the atmosphere was filled once more with the pungency of ozone. The reflectors dazzled as the initial voltage hurtled upon the doomed sphere. When the bolometer registered two degrees Centigrade, Dakin set the lever up another notch. It had all been carefully rehearsed.

Frost thickened on the crystalline surface; the little animals within stiffened with cold. The needle swung steadily to the left, retracing exactly what had once before occurred. Over, over, while the two men watched with bated breath. Minus two hundred and seventy-two degrees, slower, then the needle quivered and stuck. The temperature at which helium solidifies!

For ten minutes they waited, ten long minutes that seemed eternity. It represented the interval during which Jerry had argued with Mrs. Wiggins before young Egbert had taken their destinies into his own grubby fingers.

Jerry swung around, cowered almost against the frozen surface of the globe, even as he remembered Kay had done. Eight minutes, nine minutes, ten, while his heart pounded with suffocating thunders and his breath was a tight constriction in his throat. Suddenly he nodded. Dakin shivered, implored him with anguished eyes. It was still not too late to back out. But Jerry shook his head frantically. The precious seconds were slipping. With a groan Dakin threw the lever violently over to the last notch.

A blinding flash, a surging roar; a million volts battered into the sphere. The ice-covered surface opened, melted into hazy nothingness. Jerry threw himself around even as Kay had done. The events of a whole lifetime rushed through his brain, like those of a drowning man, of some one falling through space. For a single, tiny moment fear overwhelmed him, fear of that dreadful unknown into which he was voluntarily casting himself. Almost he sprang backward, out of the range of those fearful, beating impulses. Then, as in a dream, he saw the features of Kay shimmering before him. He gritted his teeth, held firm.

Then came the blast, as the air rushed into the vacuum of the halted atoms. It caught him, hurled him headlong, straight for the center of the misty globe. A great cry tore involuntarily from his throat as he swept, without a stagger, into the swirling interior.

He was curiously light. He floated in a current of illimitable forces. Red-hot pincers seemed to tear his flesh and bones apart. Up above, all around him, lights wavered and danced. The room was a roaring haze. Through swirling currents he saw Dakin, mouth open, eyes filled with terrible fear, darting frantically for the lever, thrusting it back to zero.

Jerry found himself suddenly smiling. The gesture was a duplication of his own former movements, and like it would be too late. But there was no doubt that poor Dakin was scared, would give anything now to undo that to which he had been an accessory.

Suddenly a cry of surprise tore from Jerry's lips. The tearing, ripping sensations had ceased. A sense of well-being invaded him. The crystalline sphere, the chair, the caged animals, hitherto vague, insubstantial, ghostly, were swimming back to solidity, to hard, tangible surfaces. But the great laboratory, the magnets, the pounding, flaming reflectors, the walls with their panels and shiny surfaces, Dakin himself, misted and fled from his senses like the tenuous wisps of a waking dream.

"Dakin! Dakin!" he shouted. "What's happening to you? Where are—" A soundless explosion scattered his amazed senses into oblivion. He knew no more——

OUTSIDE, Forbes Dakin stared aghast at the emptiness where the tourmaline sphere had stood only a second before. It had vanished; so had its occupant. Young Jerry Sloan had catapulted into a new order of things, had commenced his tremendous journey beyond space and time itself in search of his vanished sweetheart. Or else he was dead—he and Kay Ballard—utterly, irretrievably dead, as no human beings had ever been before.

With a sharp cry Dakin rushed out of the laboratory, ran hatless and coat-less through the long shadows of that June afternoon as if pursued by scourging furies. A white-haired, gentle man, panic in his eyes, oblivious to the curious stares of passers-by. A policeman caught at him as he fled.

"Here, what's the trouble?"

But the elderly physicist babbled unmeaning words, thrust off the grip of the law with a sudden twist, and was gone on his aimless race. The policeman looked after him doubtfully, shook his head, muttered to himself about old men drinking more than they could stand, and resumed his slow, majestic circuit——

It had been Jerry's strict orders that the laboratory be left untouched, exactly as it was on the momentous occasion when he first started his search for Kay. Otherwise, should they ever be able to return, disaster might ensue if they materialized within the solid confines of other objects.

These instructions were meticulously obeyed. Dakin, recovered from his senseless flight and mightily ashamed of himself, sealed the house just as it was. All doors were carefully locked but one. To that he held the key. No one else was permitted to enter.

Every day, promptly at five in the afternoon, the elderly physicist unlocked that single door, entered the laboratory, and sat in a chair well removed from the depression in the floor, until six o'clock. Then, with a sigh, he arose, took a last, lingering look at that vacant, unmoving space, at the silent magnets and the dull reflectors, set his hat on his head, let himself out of the house, carefully locked the door with a double lock, and departed to his own bachelor quarters.

Every day for a month Forbes Dakin repeated this undeviating ritual. He was a methodical man, and he had no family to expostulate with him. Strange feelings tugged at his withered heart. He had learned to love Jerry as a son during that frantic week of preparation. And now Jerry was gone, as was that slim and lovely girl who had been his assistant, and never again would he see either of them. Heaven knows what manner of thoughts went through the old man's head as he sat there, an hour each day, day in and day out, staring into that emptiness where spheres and warm flesh-and-blood humans alike, had vanished into—what?

At the end of the month Dakin felt his hopes slipping. Not that he had really expected anything else. Other matters intervened. Work that must be done. So he cut down his visits to twice a week, then to once a week.

A YEAR passed. The dust silted through tightly closed windows and doors, and made a thin carpet over apparatus and undisturbed floors and furniture. On the first of every month the old man let himself in, hopelessly stared with aged eyes at the tragic area, and let himself out again softly, quietly, as if he were afraid to awaken the sleeping echoes.

The years rolled on. The tumult, the noise of the astounding disappearances had died in the world. Edna Wiggins, more mountainous than ever and mumbling toothlessly, had other worries. Egbert had been expelled from college, had forged her name to certain checks. It required all her influence to keep him out of jail.

The very names of Kay Ballard and Jerry Sloan were forgotten. Only in Forbes Dakin's heart were they still enshrined, and until the year of his death, he made his monthly pilgrimage to the tomb-like house with religious fidelity.

Then he died. In his will were instructions. Never was the house to be torn down, or disturbed in any way. Once a year tins of food were carefully to be replaced within the laboratory; once a year trustees were to air the place and seek for evidences of the departed. Telephone connections were to be left intact, in case——

The instructions were carried out faithfully, albeit with many shrugs. Dakin had left ample funds for that purpose, and the trustees were well paid for their simple duties.

The years became decades, the decades centuries. The city grew to a marvelous thing of soaring colors and brilliant facades. The telephone gave way to television. Rockets pierced the stratosphere, made their initial flights to the moon. Interplanetary communication became an established fact; mankind grew in knowledge and power. New and impossible inventions became commonplace. With one exception—the secret that Jerry Sloan had possessed, the secret that had been his doom and the doom of that ancient girl he loved.

The house remained. A dingy, timeworn structure of indestructible stone. Generations of trustees remembered but one clause of that age-old will. The building must never be destroyed, must never be disturbed.

That grew into a tradition more immutable than the laws of the Medes and the Persians. All else was forgotten. The house became a monument, a shrine to departed generations. It was sealed beyond all possibility of entry. Fantastic legends grew around it. Within its foul and musty interior, huge machines slowly rusted and rotted away, ready to shatter at the slightest touch. The moveless dust lay thick on everything.

Then, three thousand years later, war flared. War between the planets. A Venusian fleet slashed out of space, dropped explosive spores upon the ancient city of Earth. There was a tremendous puff, and city and lofty towers of strange, new metals and millions of swarming mankind disintegrated into mile-high columns of flaming dust. The laboratory of Jerry Sloan was no more!

JERRY felt curiously free and light. Just when it was that he awakened from his trance-like state he did not know. His eyes were open, and his brain functioned with a strange new headiness. When he moved, it was without effort, without that feeling of straining muscles, of resistance within the body that is so normal and taken for granted in an Earthly existence. He might have been awake for seconds only, or it might have been for unimaginable centuries; he had no manner of deciding. The time sense was curiously lacking.

He stared around him. He was within a great, hollow sphere, whose bluish tinge made transparency a matter of definite angles of vision. Two cages hung from near-by supports. A bright-eyed mouse examined him with intense curiosity, while a canary preened itself, cocked its pert little head and trilled with carefree forgetfulness of all but the immediate present—the here-now of time and space.

Jerry's eyes traveled farther around the curving walls of his globe. He knew these things, recognized them for what they were, yet his brain, smoothly functioning though it was, had not yet adjusted present with past and future. There was a tank of water near by, its liquid surface smooth and rippleless. A loaf of golden, crusty bread looked hungrily inviting on a chair, and a great ham lay on the crystal floor, with a broken cord trailing from its brown rotundity.

Jerry blinked at it, and uttered a startled cry. That homely reminder of Earth coordinated hitherto disjointed processes within him. He remembered now. The tourmaline sphere opening up before him like a mirage; the great swish of air that hurled him into the vacuum; the last, bitter sight of Dakin frantically reversing the lever; the swift blurring of the outside world, and the final blast of oblivion.

"Kay!" The name flung itself against the confining walls, boomed hollowly in his ears. She should be here, next him, with her dancing eyes and impish smile, welcoming him to this new existence, maintaining with precious dignity that she had not been afraid, that she had known he would follow to rescue her.

But Kay was not within the sphere. A frantic fear 'drove him senselessly around the small confines, made him stumble into the chair and send it crashing, and the loaf of bread skittering almost into the tank of water. That brought him to a full awareness of his situation. Bread and water and ham! Who knew how infinitely precious they might prove before this insane adventure was over?

He rescued the loaf of bread, and sat down to consider the situation carefully. Something had gone singularly astray with his calculations. Up to a certain point they had been perfect. The globe and all its contents, including himself, had materialized in this strange new universe, even as he had suspected. Matter carried its own space time along. When motion died, the universe changed; the old wrappers disappeared and the new ones took their place. Life evidently continued, different no doubt, though as yet he had no means of detecting any particular changes.

But something else had happened. By placing the second sphere exactly in the situs of the vanished one, by reproducing with painful fidelity every detail of the initial catastrophe, he had hoped and expected that they would materialize in the new space time simultaneously and co-existently. In which case the two spheres would have coalesced and he, Jerry Sloan, would have found Kay at his side.

Yet Kay was not here. That was a self-evident fact. It was that cursed time intervals of a week on Earth. He had not dreamed it would matter here, but it did. Either that, or there was movement in this universe, a movement that had carried the other globe far out of his reach. He arose excitedly. What a fool he had been! Of course there had been movement. He had forgotten completely that he had not, could never, in the nature of things, have reproduced what had once taken place. That week of Earth time had been fatal. A second would have been as bad.

For the Earth was not still. It rotated on its axis; it whirled around the Sun; it was carried in the sweep of the solar system across the galactic Milky Way; it partook of the unimaginable speed of the expanding universe. And they were no longer subject to Earth laws, to gravitational pulls. A week apart! He laughed harshly. Millions of miles in the space of the old! What incomprehensible infinities in the space of the new!

Very slowly he drew from his pocket a tiny mechanism. It glittered mockingly in his hand. On that he had pinned his hopes of releasing the stored potential energy, of vibrating themselves back again into the universe of material things. Now it was a worse than useless thing.

Kay was goodness knows where, and even if she were at his side, they would never dare return. Rematerialization might find them in the frightening void between the planets; it might catapult them into the blazing maw of the Sun itself; or even, for all he knew, on the ragged edges of some extra-galactic nebula.

JERRY lifted his hand in impotent fury to dash the mockery of that mechanism to the shattering hardness of the tourmaline. A sudden access of sanity held his arm, and he replaced it carefully in his pocket. He sat down again, watching the unthinking animals. He envied them their timeless complacence. Life just now was pleasant; what mattered the future? For himself, he saw it all too clearly.

He had food and drink enough, with stringent rationing, for a week, or even two, of Earth time. But the air supply! That was vital! If he breathed as deeply and as rapidly as he had on Earth, a hasty calculation showed that he had not sufficient for twenty-four hours. His eyes clung speculatively to the animals. They were using up his precious supply. Now if—He shook his head determinedly. He would not do it. It was not their fault they were here. Besides, what difference did it make? An hour more or less. Eternity would last just as long.

Suppose he sat quite still, conserving his energy! That would give added minutes. With a muttered oath Jerry was on his feet. He would not cling to life like that. He stared at the enveloping crystal for the hundredth time. And for the hundredth time a bluish-gray blankness met his eye. Impenetrable, soft, with a curious luminescense of its own that shed a concentrated light within the sphere.

Without quite knowing why he did it, Jerry flung himself flat along the concave of the globe. There was a kind of gravitational force inside the sphere. But there was no up or down. He could walk indifferently on what might be considered ceiling and what might be floor. Movable articles drifted steadily, inexorably, toward each other, requiring force to separate. As if, Jerry thought with a shiver, the globe represented a closed gravitational system, a solitary blob of matter in a universe of emptiness.

Sprawled out, face pressed close to the polarizing crystal, he squinted sharply through the shifting transparency. Nothing! With a groan of despair he turned his face as he lifted. His gaze made an acute angle of incidence with the tourmaline. His body stiffened; an exclamation ripped from his lips. He had seen something.

Unwittingly he had glanced along the particular plane through which the polarized light traveled unobstructed.

Outside was a strange universe, an incredible one. There were no dimensions, or if there were, Jerry's Earth-bound senses were unable to dissociate them. It was like a gigantic cinema, where near and far flashed over the selfsame screen.

Strange, flattened shapes whirled and blurred with unimaginable rapidity. Weird distortions of startling colors blinked into view and blanked out again with abrupt finality. Orbs stretched like rubber bands to gigantic proportions and contracted with infinite speed to mere pin points of flame. A picture show, a phantasmagoria, a kaleidoscope of tumbling, constantly rearranging figures, strangely insubstantial, while all around stretched the gray luminescense of a space without height or depth or thickness, a space that was void and without form.

For a long time Jerry stared in breathless attention, his plight forgotten, everything but that weird show. Then suddenly the answers came to him. That which colored and formed a back drop for the hyperspace, the supertime into which he had been thrown, was the universe of his former being. Those shifting shadows were the projections of solid, three-dimensional suns and planets and galaxies and nebulae upon his present space and time. A magnificent peep show at which he was the sole and involuntary spectator. Somewhere in that fleeting exhibition was the Sun; somewhere among the most inconspicuous dots that flicked on and off like defective bulbs was the Earth, its nations, its endlessly striving people, its loves and sorrows and hopes and despairs.

He laughed aloud at that. It seemed so futile, so insignificant. What, for instance, was Forbes Dakin doing at this particular moment; what was Marlin, Edna Wiggins doing? Incongruously, the expression "Old buzzard!" formed on his lips. It brought a pang to him. Memories of Kay Ballard flooded him with unbearable longing.

A new fear was welling in him, a fear that would not down. The inconceivable speed with which those flattened shapes formed and re-formed, and dizzyingly blurred. What did that mean? Suddenly he knew, and with it the terrifying answer to his idle questioning.

Dakin and Marlin and Mrs. Wiggins were dead; had been dead for unimaginable ages. Perhaps the Earth itself was already a cold and lifeless ball, swinging around a crusted, darkling Sun. He was witnessing the birth and death of suns and planets and galaxies; each blanking was a death, each reappearance a blaze of new nebular matter. That accounted for the ceaseless blur. A thousand centuries of slow and ordered growth telescoped themselves into a second of breathing.

He remembered now. He was in an alien universe, a universe in which the electrons and protons and neutrons of his being had engulfed themselves upon the stoppage of their swift vibrations. Time here was adjusted to that moveless quiescence, or, what seemed more likely, the infinitely slow residual motion of mutual attractions and repulsions. This time sensation was normal to him now. The time of that other universe from which he had been thrown was now abnormal. An exhalation here meant aeons there.

Grimly he considered that. Even if he could return, even if he found, by some wild coincidence, the exact spot he had quitted, billions and trillions of years would have elapsed. The old familiar patterns had vanished into the limbo of forgotten time; he would be more an alien even than he was here. He took a deep breath, twisted slightly, and saw something that was utterly incredible.

So near he might have reached it with his hand had the crystal walls not intervened, so far away that aeons of endless flight might elapse before contact could be made, was a sphere. A tourmaline sphere, sharp and clear and transparent, moveless in the queer, flat void.

Jerry's heart stopped, then pounded with trip-hammer blows. Within its crystal round, sitting on the chair, chin cupped in slender hand, staring with eyes that no longer danced upon the circumscribing walls, was Kay Ballard! The cage doors were opened. The white mouse, brother to one he held imprisoned, gamboled sportively about her feet; the canary nibbled with greedy beak at the bread.

"KAY!" Jerry shouted insanely. It was more than incredible; it was impossible. She had reached this hyperspace a week before him, yet she was still alive. The food had not been touched; the air was still breathable. But of course! A week of Earth time meant so minute a fraction of a second in this sluggish eternity that to all intents and purposes they had reached here simultaneously.

"Kay!" he shouted again, and beat with hammering fists upon the crystal.

She did not raise her head. How could she hear? Sound required matter through which to journey. Who knew what strange stuff made up this hyperspace? Who knew what unimaginable distances separated the two spheres?

Time ceased to have all meaning for Jerry now. He shouted; he beat at the solid tourmaline; he flung himself along the concave surface, seeking somehow to attract the girl's attention. But still she sat and stared into dull and dreary nothingness, while the mouse and canary played unheeded about the globe.

The distorted projections of that other universe blurred with increasing speed; they vanished and did not reappear. One by one the misty lights flickered and went out. But Jerry did not see, or seeing, paid no attention. All his mind, all his soul was concentrated on that tourmaline orb, on the seated girl within. Nothing else mattered.

Then—it might have been minutes later, it might have been hours—Kay got up, ate sparingly of the bread, fed bits to canary and mouse, drank of the water. Listlessly she moved over the crystal, until her head stiffened, and her eyes jerked full on the prone figure of Jerry. Her startled look slid along the plane of polarized light. Her arms extended in involuntary appeal.

There they were, two human beings, each enshrined in a sphere of shining crystal, separated by unimaginable barriers, alone in the vastnesses of a space time of their own contriving. It was agony to see each other, to gesture, to beckon, and approach no nearer.

Yet, gradually, a measure of comfort grew on them. Somehow they evolved a system of code signals, semaphoring with angular positions of their arms, such as were employed by armies and navies in pre-radio days. They conversed, haltingly, it was true, but with unquenchable longing.

The hours passed unheeded. The air was staling slowly, yet at first they did not notice. Then Jerry heard a faint "cheep." The canary's beak was wide, gasping for air. Its bright beady eyes implored the man to help it in its strange predicament. Slowly its feathers ruffled and it toppled, to lie a moveless, rumpled ball. The young man realized now what it meant. The atmosphere within the ball was foul and heavy. His eyes burned and his head ached. He signaled frantically to Kay.

"Are you all right?"

She pressed close to her prisoning glass and smiled bravely. "Quite, my dear."

But it was obvious she was in distress. They took counsel. Movement to be reduced to a minimum, breathing to be shallowed as much as possible. But it was plain they could not survive more than an hour. And then——

"If only," Kay signaled in anguish, "we were together, tight in each other's arms. It would not matter so much, going out like this."

"I know," Jerry answered wearily. He stared with grim, desperate eyes at the iron bar. He did not intend suffering the agonies of the damned from slow, horrible strangulation. A crashing blow with that heavy bar on the tourmaline, a jagged hole, and the swift rush of foul air into the space vacuum without would bring merciful release.

He told Kay of that. The girl's face was pale, but composed. "It's the only way," she agreed. She was breathing heavily now, and a blue tinge was creeping around her delicate nostrils.

Slowly, inexorably, they lifted their respective bars of iron. Slowly, like automatons, they turned to each other. Separated in life by incredible barriers, perhaps in death they might once more be united. Who knew?

"Afraid?" Jerry whispered. A mirthless smile twitched over his suffering face. She could not hear, of course.

But she must have sensed what he said, for her head shook in brave negation. Her free hand lifted, went to her lips. A kiss wafted across the hyper space time for the first time in all its unthinkable existence.

Together they lifted the bars. Great pulses pounded in Jerry's temples. His eyes smarted and his lungs labored like bellows. He poised for the final signal that meant release from torture. He must hurry! Soon they would be too weak to bring the iron bars crashing. His left hand upraised. A twist of the wrist to the left, and Kay would know——

He started the irrevocable movement, held it frozen half way, then reversed with frantic, pounding gesture.

Things had been happening in their universe. Things that in their absorption in each other they had not noticed, or noting, failed to understand.

One by one the phantom projections had misted and faded, and none had come to take their place. The backdrop, the flat distortions, shimmered and disappeared, as if a master showman was tiring of his show, and slowly but inexorably was turning out his lights.

The strange, luminous gray of the ultrauniverse spread, gobbled up the blurring shapes. The colored flares were few in number now, and weakly flickering. But they seemed closer. The backdrop of eternal night closed in, was moving forward, shifting to the front of the stage, before the footlights, and advancing even as it faded and became a wraith out into the orchestral pit itself.

A wan, orange glimmer surged over the tourmaline spheres, infolded them in a haze of swift vibration that shimmered and danced like fireflies on a night in June. Jerry cried out, dropped his bar. It drifted softly, like a feather, to the crystal. Then all else blotted out in the strange new glow, but not before he had seen Kay whirl and stare with frightened eyes out into the engulfing space.

Suddenly he, too, was staring, forgetful of foul air, of nauseous headache. Something was outside his sphere. A blur of movement that shifted and gyrated with terrific speed. Formless, whizzing, yet somehow the thought hammered in Jerry's oxygen-starved brain that there was something strangely human about its queer vibrations. At times it seemed that a face, distorted, twisted out of all imagining, peered in at him. But the vision was so instantaneous, so utterly fleeting, that Jerry laid it to the poisoned air that clogged his veins, the close approach of delirium.

Yet he withheld that final blow. Instinct warned him to wait, even to the last gasp of suffocation. Within the echoing, semidarkened recesses of his brain he seemed to hear a voice, urging him to make no move. There were seconds when the eerie, formless blur disappeared, but it always returned. The intervals grew longer, the elongated face showed actually for split seconds of time. Certain tiny sounds tinkled in the tourmaline, as if——

JERRY lay within the sphere, half delirious. The air was a fetid, noisome effluvium, which his lungs gulped and rejected. His throat was a fiery constriction, and darkness was filming his eyes. Perhaps that was why the orange glow seemed to become fainter and fainter, and the strange, superhuman face without steadied for seconds at a time, and the tinkling noises grew in intensity and duration.

He was drifting, drifting. The light was dying, but rocket flares exploded in his head. Death stole slowly over him. There was a sudden grinding noise, a surge of something cold and biting, and consciousness left him——

Memories of childhood struggled bewilderedly through Jerry as he opened his eyes. Surely that noble, well-proportioned being with the benignant, superhuman features who bent over him was of angelic descent. Even such had he seen depicted in the genius-intoxicated drawings of that strange madman and ecstatic visionary of the eighteenth century, William Blake.

Something spoke within Jerry. It was not sound; it was not a voice; it was a series of thoughts incredibly impacting on his brain.

"Do not be alarmed," they soothed. "You are quite all right now. Breathe deeply."

Jerry obeyed the inner voice. It was good to draw into his tortured lungs the clean, sweet air.

"But who are you," he cried, "and how did you get inside the sphere?" The man smiled. It illumined and transfigured his mobile features, made him almost god-like in countenance. "Strange sounds issue from your lips, O being from another universe who yet resembles so closely our own kind. I do not understand them. They are harsh and discordant. But your thoughts impact on mine and I understand those. There is a tradition," he mused, and the sentence pictures somehow arranged themselves in proper patterns to Jerry, "that in the misty, incredible antiquity of our own race it was necessary for primitive beings to make noises with their lips for communication."

"Then you have mastered telepathic conversation," Jerry said in awed tones. He still spoke; it would take him a long time to achieve the disciplined ordering of thoughts that came so easily to his mentor.

The man nodded. "For uncounted aeons now. But to answer your questions: I am Horgo, of the outpost galaxy, Andromede. A hundred thousand light journeys ago two spheres of strange design emerged with infinite slowness, out of the formless void into which we were hurtling. Our instruments detected them first, as the faintest of faint impingements of ether stresses on delicate dials. My great great ancestor, and Lika's, too, famous scientists of that early time, discovered them.

"Yet the spheres could not be seen, for the ether particles held no vibration. A new, other-universe form of matter. They tried their mightiest forces, compounded of the last expiring gasps of stellar laboratories, to break them down, to penetrate their invisible, albeit rigidly impenetrable sheaths, without result.

"My ancestor was a great scientist, I have said, far in advance of his time. Even then the universe was dying. The expanding effect of that first great explosion of primal central matter was losing momentum, in accordance with the inexorable laws of thermodynamics. Matter was dissipating into waves of energy; waves of energy were spreading and thinning out as the universe expanded and created new space-time units on its far-flung outposts. Already the more central galaxies were dark and slowly vanishing. A moveless heat-death was holding them in thrall. Already the race of man had moved from the tiny galaxy it had inhabited since the farthermost reaches of time to the island universe of Oria. Then that, too, faded into the matterless, waveless uniformity of the heat-death."

Horgo stared out of the crystalline sphere at the gray waste with sad, weary eyes. The orange glow had gone; the flickering distortions were gone, nothing remained but gray, motionless nothingness. His thought processes slid into Jerry's brain again.

"From galaxy to galaxy we pushed, ever outward, until we reached Andromede, the last outpost. Here the race was forced to halt. Beyond was neither space nor time. Yet, still the primal energy was strongest here, the universe still expanding, and creating new units of space and time as it rushed outward. But this could not keep up forever. My ancestor realized that. His instruments showed the slowing up, the enormous dissipation of energy into rippleless waves. With a flash of genius he realized that these spheres, impenetrable to all their science, held perhaps the secret of a conservation of energy, of a self-contained system, that contradicted or defied the laws of thermodynamics."

JERRY had been hearkening to those inner thought patterns with growing amazement. Oria! Andromede! Good night! Those were the nebular galaxies he had known as Orion and Andromeda. Then he was back in his own universe, and Horgo, this superhuman, was perhaps the last mighty representative of his own race, left far behind in the dim reaches of Earth. His brain whirled. They had returned, been swallowed by the ceaseless expansion, but unimaginable billions of years into the future, when the universe had degraded into that moveless heat-death bath of which even in his primitive day certain scientists had spoken.

Horgo's face lighted. He had read Jerry's spinning thoughts. "Yes," he sent his patterns across, "we must be members of the same race. The extremities of time have met. The first primitive form and the very last. For nowhere else in the universe did we men who first had sprung from the tiny speck called Erd ever find life like ours. But to continue:

"My ancestor was short-lived. In those days lives did not extend beyond a thousand light journeys. Nor were his instruments as advanced as they were later to become. He labored mightily to break through those invisible spheres of locked-in energy. He did not succeed. His sons took up the task. They failed, too, but they managed to invent an infra-camera which photographed by a negative process. The lacunae in the ceaseless flow of wave impulses that permeate the entire universe registered on the disks by their very lack of energy.

"So it was that you and your sister sphere first became visible. Judge of their surprise to find two beings in their hollow shells, rudimentary, it is true, but nevertheless somewhat similar to themselves. Unfortunately the pair seemed dead. They neither moved nor budged from their unnatural, rigid positions. A state of death or cataleptic trance at best. A lifetime of observation showed no change. But they did not give up their task, and took thousands on thousands of negative photographs of the spheres."

Jerry shivered as he considered what that meant. Thousands of time units of the order of light years had flashed by in the outer universe while he, inside the sphere, had not yet completed the simplest gesture. And Kay! The memory of her jerked him into awareness. He caught Horgo's arm in a grip of steel. His voice clanged harshly. "The girl in the other crystal globe! She is dying while we are doing nothing. You must rescue her at once." Horgo winced at the crude concussions of sound. It was evident that uncouth noises had been obliterated from the dying universe along with speech. "You need not blast at me with frightful clamor," he observed mildly. "Think the thoughts you wish and I shall understand. But have no fear for the girl. Lika has entered her orb and even now is ministering to her wants. Her thoughts are a steady flow in my brain." Jerry dropped Horgo's hand. Joy tingled in his veins. As long as Kay was alive——

"Thank you," he started to say, caught himself, and thought it.

Horgo smiled approvingly. "That is better. To return to my narrative: It was in the next generation that the accumulated photographs showed that you were not dead. Your positions had changed, though to no great extent. That heartened the workers. They had discovered the secret of lengthening their lives to fifty thousand light journeys, though it was left to Lika and myself to find the true secret of immortality.

"An immortality"—he smiled sadly—"that seemed profitless and horrifying. For the universe was fast dying. It was only by the most tremendous exertions that we were able to concentrate sufficient of the feeble energy flow of almost vanished matter to keep ourselves intact, to keep our apparatus functioning. Soon that, too, would be gone. Yet ever, before our very eyes, were the visible signs that some one had discovered the secret of immuring energy in potential form. For we realized by now that you were alive, that your infinitely slow movements were the product of the infinitely slow corresponding motions of your constituent ether units.

"So we redoubled our efforts. Your spheres gradually grew to a hazy type of visibility, as our ether units slowed wearily down. If only we could break through before the moveless sea of thermal death sapped the last supply of our energies!

"The few who survived with us succumbed, one by one, fading slowly from view as their protons and electrons dissipated in a slow disintegration. We alone were left, Lika and I. Soon we, too, would fade into nothingness. Then, by a lucky accident, Lika stumbled on the solution. We staked every available source of energy on a last mighty effort. We floated in a sphere of force of our own contriving. The waveless, featureless universe nibbled sluggishly at its outer shell, contracting it slowly, but perceptibly, about us.

"With bated breath we threw the beams upon the spheres. With delight we saw them grow in clarity, saw them open along the beam path. The mighty concentrated forces, the essence of the universe, thrust aside the static unbreakability of your units, held them open long enough for us to push ourselves along the path and enter with the supplies we needed. Then the beams flickered and were spent, and the universe-resistant spheres swung back into place."