RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Despite optimistic predictions that the future will bring a veritable Utopia for all people, it is quite possible that a very different state of affairs might occur.

We know that in the past powerful men have seized control of cities and nations and have used their inhabitants for their own selfish schemes of power. And today we have eminent students of our modern civilization asserting that powerful industrial groups are working toward an economic enslavement of the masses of the people. If that comes true, the world of the future may indeed be a terrible place for the billions of workers.

Whether this will come true or not, we have no means of knowing; but we must admit that it is a possibility, and that possibility has been used by our authors as the basis of what we must term "a marvelous story." The theme of the authors—the enslavement of the people of the earth and their struggles for freedom—is not accepted by the publishers; but we allow our authors to present it to our readers. For this is not only an exciting, a gripping and a stimulating story, but it is a terrific challenge to every living person!

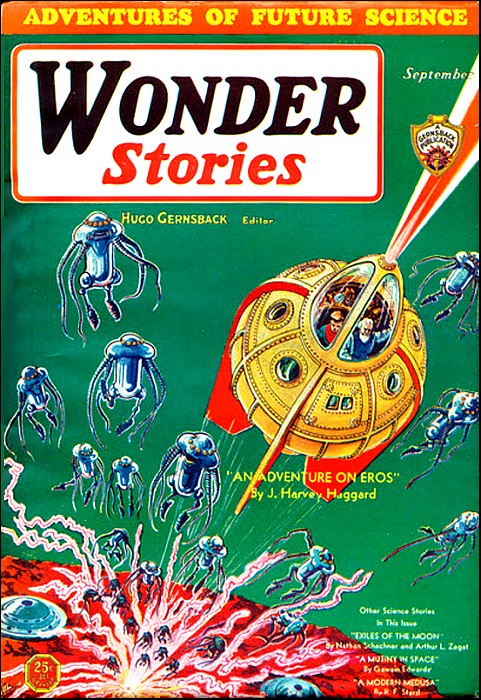

Wonder Stories, September 1931, with part 1 of "Exiles of the Moon"

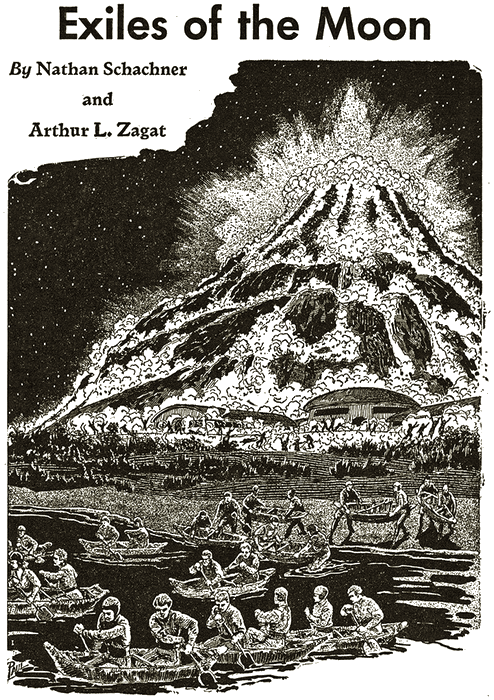

The advancing tide had reached, engulfed the buildings. A great

mountain of green flame loomed, a vast pile of billowing light.

GARRY PARKER, rocket pilot of the flier Ventura, glanced at the chart suspended above the gleaming controls. The light dot quivered, moved slowly toward the red hairline that indicated the end of his trick. It would take the great liner but five minutes to speed the two hundred and fifty miles remaining, then he would be through for this trip. The altimeter showed twenty-five miles up. Right to the dot! A perfect voyage!

Time to check speed for the change-over.

Garry twisted the dial that would send out a furious blast from the bow tube. Careful now. The new nascent hydrogen in the fuel mixture was the very devil. Just a little too much and the Ventura's nose would be driven down; she would dive before the wings and the gyrocopters could be thrown out, and the huge liner would become a flaming meteor, falling faster and faster till she plunged, hissing, with her thousand passengers into the watery depths below. Wonderful stuff, though, the new mixture! It had cut ten minutes from the Berlin-New York schedule—an even hour it took now.

The position light was almost touching the red line. Parker spoke aloud, though there was no one else in the control-cabin. "On the mark, sir."

Another voice sounded; from nowhere, it seemed. "Very good, mister! Change over!" It was the voice of the Ventura's captain from thousands of miles of space from a cubbyhole in Paris, at Western Hemisphere Transportation Headquarters. Another new development this, taking the captain off the ships. It worried Parker sometimes—he felt in his bones that other, greater changes were coming in the operation of the airlines.

The door behind Garry opened and closed. Dick Thomas was at his side, the wings on the breast of his gray-green uniform indicating that he was the plane pilot. A brief shoulder touch of greeting, and Dick had slid into his seat beside Parker's.

Swiftly the two went through the familiar routine of the changeover. As Garry twirled the dials shutting off all rocket tubes, Dick thrust home the levers that swung out the wings and sent aloft the whirling gyrocopter vanes. Outside, they knew, the Ventura was no longer a smooth skinned, stream lined projectile ripping through the near vacuum of the stratosphere, but a huge airplane, ready with its great span of multiple airfoils to bite into the sustaining atmosphere below as it zoomed down to the waiting airport. A faint vibration could be felt as the Preston-Diesels took over the task of propulsion from gas tubes at Dick's touch on a button.

"Change-over complete, sir," Garry reported to his distant chief.

"Very good, mister," the concealed speaker brought the acknowledgement.

"Plane Pilot Thomas, in control, sir!" Dick took up the routine.

"Make it so, Mister. Rocket Pilot Garry Parker, C12574, relieved. Plane Pilot Richard Thomas, C46890, in control, Ship Ventura." The captain could be heard relaying the reports to the chief dispatcher's desk.

"Good landings Dick," Garry voiced the phrase that the etiquette of the air-lines prescribed for a rocket pilot on being relieved. Similarly, when the change-over form a plane to a rocket-ship had come at the start of the journey, Dick had given up control with the words, "Straight flight, Garry." Tradition had it that omission of these ritualistic phrases would bring sure disaster. Superstition, of course, but those who go up into the air in ships have ever been superstitious.

PARKER passed through the door leading into the pilot's rest room, his broad shoulders brushing against the sills. He could relax now, this was his last trip of the day. Almost automatic as these star liners were, it was still a tremendous strain to sit at the controls of a huge shell that was zipping through space at a mile a second. A mile a second, that was the speed the new fuel gave them. And only ten years ago, in 2240, when he was beginning his training, thirty miles a minute was considered the uttermost limit.

Well, now that both the oxygen and the hydrogen were in a nascent state, there couldn't be any further advance. Only the dreamers whose wanderlust called them to the moon and the stars would want greater speed. Seven miles a second it would take to get out of the earth's attraction. No use thinking along those lines. Have to stick to old Earth awhile.

"Garry!" A soft voice thrilled behind him. He whirled.

"Naomi!"

A girl had come into the severe, bare room. A girl of the Aristocrats, her bearing, the soft flowing draperies that accentuated the. lithe grace of her figure, proclaimed that. Long centuries of breeding, of refinement, in the piquant face, in the very gesture of the arms thrown out to him. Character, too, in the frank gaze of her black eyes, in the firm line of her lips, the determined curve of her little chin. The saving grace of humor in the tip-tilted nose, the little twist of mischief tugging at the corners of her mouth. A stride, and his lips were covering hers in a long hungry kiss.

"Naomi, it's good to see you. But what are you doing in here? You know communication between passengers and the pilots is absolutely forbidden."

"Forbidden to me, Naomi of the Fentons! You forget that I am the daughter of Henry of the Fentons, America's member of the World Council of Five. A Fenton is above the Law!" For a moment the hauteur of her caste rendered her less lovely in Garry's eyes, then—"No, nothing is forbidden to me, save to marry the man I love." The ghost of a sob tarnished the silver of her voice.

"But, dear, that's just it. If your father learned that you came in here to talk to me, he'd suspect something. And, I'm afraid you'd suffer for it."

"Oh don't worry about father, I've told you that I always have twisted him about my little finger. The only thing I fear is what he might do to you, and I'm quite sure that he'd never dream that I would fall in love with a Worker."

"Besides, darling," pain showed in Garry's voice, "I have no right to let you keep on loving me. Granted that we might find some way to avoid the strict Caste Law forbidding any union between an Aristocrat and a Worker, I cannot drag you down to my caste. That's what it would mean, you know—" he went on hastily as he saw protest trembling for utterance on the girl's lips. "Our whole social organization rests on the conception that the Aristocrats and the Workers are races apart. You know, as well as I, that the one Law that even the Council cannot change is that which says that a Worker can never rise to the Aristocracy."

"Yes, I know," he went on, forestalling the defence of her class that he saw rising to the girl's lips. "I know the old cant, that the Aristocrats are the only class fit to rule, that they are trustees of the Machines and all they produce, administering the World's goods for benefit of Patrician and Worker alike. Fine words! Specious theories! But how have they worked out?

"This might have been a wonderful place to live in, this Earth of ours. With the development of the Machines hours of labor should have been cut to a minimum, leisure, and culture, all the finer things of life might have been and should have been, the heritage of all. But your class, under the bland pretext of paternalism, have arrogated to themselves the benefits of scientific progress, and have made of us, the Workers, veritable slaves to the Machines we tend. They sit at the banquet table, and expect us to be content with the broken meats they fling us. We crowd around the doorway, gazing at the least, barred forever from entering by the flaming sword of the Caste Law."

"For our good, you say. For our good you give us creature comfort, but kill our minds with the denial of ambition, opportunity, reward, all that to a thinking man makes life worth while! And if we tire, if our gorge at the measured routine of our lives rises in our throats and chokes us, so that we refuse to work in the ordered fashion, you shake your heads sadly, and with tongue in cheek, say to us: 'Very well. You do not care for the way Society is ordered, then get you gone and make your own Society.' And you send us, great hordes of us, to the Idlers' Colonies in the tropical deserts or the arctic ice fields. 'Make your own world here,' you say to us, 'we shall not interfere.' No, you do not interfere with the cold that freezes us, the heat that burns us, the starvation that laughs at the puny efforts that our unused hands make to feed us.

"But what am I saying," he interrupted himself, "you are not responsible for all this. You, as well as I, are a victim of a system we have had no part in making.

"You would forget your caste, and, for the love of me, become a woman of the Workers. What do you know of the life of a Worker's wife? Housed in great barracks, watched, and spied upon, and guarded. Every moment of her life charted and catalogued by inexorable regulation. So many hours for culture, so many hours of exercise and amusement, rigidly delimited in kind and degree. For her good, your Councils say. Yes, for her good they take her children from her after five short years, lose them in the great vocational schools, to be trained to the common mould, fashioned into cogs in the great World Machine. No, Naomi darling! I cannot, dare not, permit you to share that lot with me."

THE girl stood straight before him, her eyes burned into his.

"Garry," she asked, "do you love me?"

"With every fibre of my being, that is why—"

"That is all I want to know. Then what you say means nothing to me. I love you. That is all I know, all I want to know. When you call me, I shall be ready. Ready to go with you, to be your wife, to endure the Worker's lot, or worse, if only it be at your side."

"Do you mean that, Naomi?"

"Must I get down on my knees and beg you to marry me?"

"No use in my arguing further." Garry's voice rang with joy. "We'll find a way." His arms went out, the girl nestled close within them. A moment they clung, then, gently, she pushed him away. "But, Garry dear, I'm forgetting what I came in here to tell you."

Parker interrupted, engrossed in his own thoughts. "Listen, Naomi," his voice dropped low, "I hadn't meant to speak of it so soon. There's something on foot among us Workers, plans that are still only being whispered among a few. Discontent is spreading. There may be a flare-up soon. Conditions may change. Let us wait—six months—a year—and our problem may be solved."

Naomi shook her head. "That's it, we can't wait. That's the news I have for you. Father called me in yesterday, and told me that he had decided that I am to marry in a week."

"What!"

"In a week. And guess whom."

Garry's eyes were blazing, his knuckles showed white, so tightly were his fists clenched. "Who?" he burst out.

"Sadakuchi. Sadakuchi of the Samurai."

"No!" he grained, "Not the Asiatic!"

"Yes, the Asiatic."

"But how could your father bring himself to propose such a thing."

Wearily she explained. "Reasons of state. I've become a pawn in the great game of world politics that so absorbs father. You see, just at present there is a deadlock on the Council of Five. Father and George of the Windsors, the European, against the African and the Australasian. Hokusai of the Samurai, the Asiatic representative, holds the balance. So far he has allied himself to neither side. But his son, Sadakuchi, Chief of the World Police, has decided he wants me. And so Hokusai has delivered his ultimatum. Father is in the seventh heaven of delight. To him it means the fruition of his labors of years, control of the Council and of the world. I wasn't even consulted."

"It's hellish!"

"You see, my dear, life isn't all peaches and cream even of a woman of the Aristocrats. So we have just a week."

"He can't have you." Parker snapped out. "That's up to you. Just a week."

The deep note of a gong startled the couple. "That's the landing signal, Naomi, we're over the airport. You must leave me now, or we'll surely be discovered. I'm off duty for six days. We'll work something out. Can you get away tonight?"

"I'll try. The usual place, at ten?"

"Right. Meantime I'll be thinking hard. Go now, dear."

A swift kiss, and he was alone again in the rest room.

Garry turned toward a port hole, his brain in a whirl. He, a Worker, had dared to raise his eyes to an Aristocrat of the Aristocrats, a daughter of a World Councilman, and she had deigned to stoop to him, to love him. A surge of defiance swept through his blood. In spite of the Law, in spite of the Council itself, he would take his mate. Sadakuchi, indeed. His fingers tightened as if he felt a yellow throat within their grip.

He slid open the metal shutter of the port. The Ventura was hovering above the landing field." A mile below he could see the great jaws of her cradle slowly opening to receive her. To the west, frothing upward in a vast leaping tide of steel and stone, spread the miracle of New York.

GARRY thrilled again to that sight, as he had thrilled hundreds of times before. From a myriad soaring pinnacles the rays of the setting sun flashed in brilliant coruscation. A brilliant haze overhung the city, through which swarms of black midges that were man-bearing planes soared and sped. In graceful arcs white marble bridges curved, spanning half-mile deep chasms, man-made, in whose depths artificial suns fought their day-long battle with the shadows.

Already, in the mid-height zone, where no longer the level beams of sunlight penetrated, and the street-lamps' radiance could not reach, a million lighted windows spread, a wide-flung firmament of stars. In a hundred mile circle the glittering metropolis blanketed the earth with beauty, from where the broad Atlantic heaved its green expanse, to the far north and west, where, in thin silver threads, once mighty rivers disappeared beneath the city's steel and stone, to seek the sea in dark tunnels far below.

Again the deep-toned gong vibrated through the craft. The field drifted upward, slowly at first, then faster and faster, till the Ventura was dropping like a plummet. It seemed as though in a moment the huge ship would crash thunderously into the ground. Then a screech as the gyrocopters bit into the heavier air, a shudder as the great fabric felt the upward tug. And the liner settled, soft as thistledown, into its berth.

A moment's glimpse only, Garry had of his sweetheart, across the bustling field, as she slipped lightly into the seat of a scarlet Arrow runabout, the black WC emblazoned on its nose. Potent symbol that, opening all traffic lanes, voiding all rules of the air! Straight upward the two-seater shot, a frantic green police gyrocopter clearing the way through the crowding traffic with its piercing siren.

"Hey, Garry, wake up! Think you'd never seen a landing field before, the way you're standing there gaping. Come on, let's check out. I've got a dame waiting for me." Dick Thomas' hearty slap on the back brought the tall pilot back from his chaotic thoughts.

"All right, Dick, get a car."

Thomas focussed the violet beam of a hand flash on a plate gleaming from the door of a low structure a hundred yards away. The barrier swung open. The 'eye' of a three-wheeled Hammond scooter caught the guiding ray, came skimming across the concrete tarmac toward the waiting couple.

Once a quick jerk of Dick's hand swerved it out of the path of a lumbering freight conveyor. The vivid curses of the operator came thinly through the tumult of the port, to be ignored by the plane pilot. The objurgations of this groundling were beneath the notice of a flier.

"HOP in, Garry." Parker folded his length into the narrow confines of the little machine, switched off the teleradio control. Under Thomas' skilful hand the Hammond weaved its way through the bustling traffic of the busy terminal. "There goes the 6:15 to Tokyo." Dick remarked to the silent, moody Parker. "Manton has just been transferred to her. I'm glad he's got his step-up at last."

"What happened to Reynolds?" Garry roused himself.

"Idlers' Colony!" came the succinct response.

"'Idlers' Colony', Reynolds!" Parker was startled. "Why, there was no harder working pilot than Reynolds, none more obedient. I can't imagine him insubordinate! How come?"

A bitter note crept into Thomas' voice. "Don't mean to tell me you don't know how those things happen, do you? The reclassification headquarters is a regular hotbed of whispering and intrigue. Couldn't help but being, with the methods they pursue. A complaint from any petty overseer or superintendent and a Worker is shipped off without a chance to be heard in his own defence. He doesn't even know who accused him, or the charge. They say a full quarter of those sent to Idlers' Colonies are perfectly good citizens, with no thought of doing anything but to obey orders.

"I don't know just what happened in Reynolds' case," he continued, "but there was talk that he was in line for promotion to district overseer, and that Kaden thought the job ought to come to him. Kaden, you know, is pretty thick with Layton into classification headquarters. Draw your own conclusions."

"So that's the way it works! Not only are we barred by the Caste Law from ever becoming members of the governing class, but in even the small ambitions left to us we must fear the malice of some petty official or the intrigue of some scheming bootlicker. That's your fine paternalistic government for you! I tell you, this world is organized for the Aristocracy, and for them alone. Fine words to the contrary notwithstanding, we Workers are slaves, downtrodden slaves, serving our masters, the Aristocrats, and living at their sufferance."

Dick paled. "Cut it out. You'll have us both hauled up for sedition. Man, suppose you were overheard!"

"Oh damn that. I'm sick of the whole thing. Suppose one of their spying listening beams did pick me up! I'd be sent to a Colony. At least there I'd be free within limits—"

"Yeah, free to starve to death. Me, I'm perfectly content right here. All I've got to do is obey orders and keep my mouth shut, and I can enjoy life. The Aristocrats can do all the managing—they're trained for that. My job is to start and land rocket ships."

"And you'll be starting and landing rocket ships all your life," Garry broke in. "That would be all right if it was your own will that kept you a pilot. But you have no hope of doing anything else. Don't you feel that there are certain human rights that are denied you, the right to live your own life in your own way, the right to strive to attain any position in society to which your inherent ability entitles you?"

"I think you're talking a lot of buncombe," Thomas growled. "The whole question was settled a hundred years ago, in the Worker's Rebellion. Haven't forgotten your history, have you?"

Parker shrugged. His fist clenched for a fleeting moment. "No," he said slowly, I haven't forgotten my history. The question was settled then, with poison gas, and searing electronic discharges, and the torn bodies of men and women."

"That was unfortunate, I'll grant you. But just look. The Aristocrats, after that victory, might have made us slaves. Instead—"

"Instead, they call us something else—wards, children, Workers! But names don't change truths. We're slaves just the same!" The Hammond hissed to a stop in front of the Airport Headquarters. The two pilots strolled up the broad ramp, entered the high domed lobby, and turned to the left, where a long row of ground glass disks, two inches in diameter, glowed yellowly in the marble wall.

Garry was all impatience now, to check in and be gone. A bare six days of leave lay before him. Six days in which to plan and bring to fruition a scheme to save Naomi from the unnatural marriage to which politics had doomed her. Six days in which to puzzle out a way to evade the Caste Law and take her for his bride.

Dick finished, stepped aside. Parker placed the ball of his right thumb on the disk his comrade had just quitted. A metallic voice sounded from the wall.

"C-One-two-five-seven-four. Checking in." The tall pilot waited for the next words, as a whirring behind the marble surface indicated the operation of. the selective mechanism as it sorted out his orders from the hundreds of encased records. He knew what they would be, of course—"Relieved for six days."

The disembodied voice began again its rasping, unhuman drone. "Garry Parker, pilot, C-one-two-five-seven-four, will report to Overseer Twelfth District for orders."

GARRY stared unbelievingly at the unresponsive disk. Orders! No time to think of his own huge problem, to plan with Naomi—. But wait. Perhaps it was just some minor task that might be completed in an hour or two. He whirled, and, without so much as a nodded good-bye to the startled Thomas, dashed across the lobby to the bronze door above which glowed the words: "Overseer, Twelfth District, Air Transportation Division."

He flung the door open. Within, seated at a desk whose surface was covered with serried push buttons, a grim faced official arched grizzled eyebrows at the unceremonious intrusion. Garry saluted scantily, gasp-out, "Parker, C12574, sir. Reporting for orders.

The overseer nodded coldly, then punched a number of the buttons before him. From a slit in the center of the desk a blue card appeared. The official glanced at it, then looked up.

"Parker." His voice was precise, formal. "You have been transferred to the Tokyo-San Francisco run, ship Ganymede. You will base at San Francisco airport. Report there at midnight for immediate duty." Garry caught at the desk-edge. "But—but I'm due for six days leave, sir."

His superior shrugged. "That can't be helped. Those are your orders."

"But I can't go—tonight. I have things to attend to, important matters."

"You can't go?" The overseer's voice, impersonal before, was now freezingly deliberate. "I have no record of any matters which would interfere with this assignment."

"But these are personal affairs."

"Personal affairs. You'll have to forget them. Orders cannot be changed for personal affairs of a Worker."

Garry's face was white with rage. This transfer would cut him off from Naomi, forever. His brain raced. In a week she would be married to Sadakuchi, and he soaring over the Pacific. "Orders cannot be changed for personal affairs of a Worker." A Worker was a pawn, a slave, a Machine! Something exploded behind his eyes. Then he was saying, very slowly: "I refuse to obey!"

Even then no change of expression showed in the grim face before him. The steely eyes flickered to the card, then back again to the inwardly trembling pilot. "I see a notation that you are suspect of harboring seditious notions. Since I have had nothing to complain of I asked that judgment be suspended. I find that I was wrong.

"You have refused duty. This makes your case one for summary disposal without reference to re-classification headquarters." Gary blanched, he knew what was coming. The overseer referred to a chart that he drew from a drawer. "You will report to Division ZZ at 10 A.M. Greenwich time, tomorrow. That is all." And he turned away.

Garry reeled from the room. This then, was the end.

Bad enough it had been before, aspiring to marry a Fenton. Only some wild, some unheard of plan could have brought him success. Now however, the thing had become impossible. Tomorrow, at this time, he would be broiling beneath a tropical sun, or shivering under the icy blasts of an arctic wind. And Naomi, in another world, thrust by the inexorable rule of her caste into unwilling union with the yellow Samurai. The glow of futile satisfaction that had warned him at his defiance of authority died away. Black despair welled up within him.

Mechanically his long legs carried him to the pneumatic tube station, blind instinct directed him to the proper aperture. A car had almost filled; he could barely wedge his broad shoulders into the remaining space. But the crowded discomfort made no impression on him. He did not notice the sealing of the entrance, the hiss of the admitted air, the twenty minute flight that took him for the last time to the C Division living area, a hundred miles away. Wearily, futilely, his dazed brain strove for some way to break the meshes of the net that had closed inexorably about him.

Afterwards Garry wondered how he managed to reach his cubicle in the bachelor dormitories on the Second Level without accident. One had to be alert to pass across the series of progressively speeding conveyor ribbons to reach the central path that spiralled upward two hundred feet, then shot at sixty miles an hour along the radial street. He dimly remembered stumbling, someone hauling him upright, a shouted objurgation from a Traffic Controlman. But it was only when he found himself in the familiar surroundings of the little room that he really came to himself. He threw himself heavily on the steel-framed cot, stared at the neat shelves that held the few paltry things that he might call his own. Tomorrow he would leave this room forever.

HE had small time, however, to lie there, to strive to find his bearings in the chaos his world had become. The call-disk over the entrance flashed three times, signal for the evening meal. No one ever had less desire for food, but absence from the dining hall would bring swift investigation, demand involved explanation. The iron routine of the Worker's life closed about him once more.

Once seated at the circular table with his fellows, the resiliency of youth asserted itself. The portions he seized from the steaming platters that passed slowly before him on the endless belt were large, his huge body demanded huge amounts of fuel. As he ate, he became aware of the buzz of conversation about him.

"I hear there's been more trouble in the Arctic Idlers' Colony," Thompson, a weazened tender of a solar power converter remarked at large.

"Oh, some of these guys what thinks they're as smart as the Aristocrats got to talking. They grabbed a ship, tied up the crew, and were all set to skip when the Arethusa, with Sadakuchi himself on board, came sailin' up. His ray guns made short work of them, you can bet."

"Damn fools. Don't know when they're well off. Even if the tramps don't want to work, what's the matter with loafing around up there. Just looking for trouble, that's all they are."

"Just heard of something new," someone else broke into the conversation. "Division ZZ special. Been operating about a month. About a thousand been directed to report there so far. No one has learned what Idlers' Colony they've been sent to, nor has any message ever gotten back from them."

"They say it's another new colonization scheme. You know, they've been getting a little worried about all the grumbling in the regular Idlers' Colonies.

"Worried, hell! The Aristocrats ain't worried about our grumbling. I'll bet when the truth comes out about this ZZ special business it'll be a damn sight worse than the old scheme."

"'S funny at that. I knew a few of the bunch that went. And every mother's son o' them were—well, you know, not exactly aces up with the Aristos." The man hesitated as if he could say much more, but was afraid.

The other nodded understandingly. "I get you. You think they were slated."

"Well, it might look that way," the first speaker admitted cautiously.

A freighter pilot spoke up. "Say, fellows, last trip in I carried a bunch of cows, delivered them to ZZ special headquarters."

"Cows! What's that?"

"Hey, don't you know your geometry? That's the animal they used to get meat from, and milk."

"G'wan. You're kidding me." The talk had moved to a group of striplings, youngsters just come up from the training schools. "That stuff is all made in the food factories, I've seen them myself, down in the Harlem district."

"That's only in the past thirty years." A grizzled veteran spoke up. "I can remember, when I was a kid, they had big fields down in South America where they grew all kinds of grain, and others where there were thousands and thousands of cows and other animals that they used to kill for food."

"Oh, Pop's at it again. Hey, bunch, gather round, Pop Foster's telling his fairy stories again."

Parker smiled cynically to himself. From his great age of twenty-five he looked compassionately at these skylarking youngsters of eighteen. They'd learn, soon enough.

THE white glow that lighted the room changed to red for an instant, then to white again. Three minutes to finish. The talk stopped as the eaters hurriedly completed their meals, and shoved their empty plates and soiled utensils on to the ceaselessly moving serving belt that carried them away to the washing machines. A green flash. "Meal over."

Back in his room, Garry pressed the 'time' button on the tiny communication disk strapped to his left upper-arm. "Eight-twenty-six," the metallic voice of the Central Chronometer Broadcast responded. "Time to get going," he muttered.

He stepped to the open doorway, peered up and down the corridor. No one about.

Swiftly he lifted a board in the floor, extracted a flat, cloth-wrapped package from the aperture, thrust it under his tunic.

It was the recreation hour, and the common street was crowded with Workers. On the stationary sidewalks, close against the building lines, couples strolled, in the tight-fitting clothing of their caste, each colored to indicate the wearer's occupation. The slow-moving ways that bordered the walks, were filled with younger men, their eyes gleaming with anticipation of the evening's pleasure. Parker made his way across these to the central express conveyor, more sparsely peopled with those who were hurrying some distance, to community amusement halls, or sports arenas.

The moving belt circled around an opening, a hundred feet across. From a spiral ascendor debouched a group of weary-faced, haggard workers in the factory drab, just released from toil on Level One, below. Garry glanced upward. Infinitely far above, a single star gleamed in a disk of black sky, darting its yellow beam down the half-mile shaft. Then the momentary vision was cut off by the roofing underside of the Level Three conveyors, five hundred feet above.

A blare of music reached the blonde pilot from the arched entrance of an amusement hall, where clustered hundreds sat, watching the televised representation of an entertainment being presented to the patricians in a terraced garden somewhere on the roof of the city, under the star sprinkled sky that was merely a legend to these watchers. Garry started to move outward, striding diagonally across the speed-graded belts, till he reached the stationary walk just opposite a dark aperture in the soaring concrete wall of the Northeast Workers' Gymnasium. A quick glance around showed that he was unobserved. He dived into the narrow passage.

A tunnel angled dimly off, low-ceiled, cluttered with forgotten lumber, broken lumps of discarded concrete blocks, debris of all kind. By what aberration of the building machines this curious passage had been left in the thick wall through which it wandered Garry did not know, nor did he care. It had stood him in good stead more than once, as it would serve him now.

With the ease of familiarity he made his way some distance in, till the last faint beams of outer light had been swallowed up in darkness. Then, working rapidly by feeling alone, he stripped off the pilot's uniform he wore, unwrapped the bundle he had taken with him, and donned the garments the cloth had covered. The silk rustled in the silence, for this was an Aristocrat's uniform, procured somehow by Naomi.

Without it their rendezvous would have been impossible, for the upper levels were prohibited to all Workers save those whose duties took them there. He pulled the close fitting satin helmet down over his blonde hair, inserting his communication disk in the ear-flap pocket, as the patricians wore theirs. Then he stuffed the clothing he had discarded into a hole in the wall, and turned to go.

A scuffling at the entrance halted him. Silhouetted against the light he saw three forms. Garry crouched against the wall. The men were coming in! He tried to halt his breathing, to melt into the very stone. Who were they? Police? No, too tall. Who then?

ONE passed him. The odor of an unwashed body came to his nostrils. The second was passing, tripped, cursing. His reaching hand plumped square into Parker's face. "Hey, what's this? Someone's here, fellows." A gruff voice. "Show a light, Tim."

A hand flash gleamed. Garry glimpsed three burly figures, haggard faces, eyes burning with a wolfish, bestial glare. Then the light was gone.

"A bloomin' Aristo. Well, wadda you think o' that." There was menace in the growling tones. "A nice little patrician, right in our parlor. Here's luck, guys!"

"Kill the dog, quick, before he has a chance to yell."

Parker opened his mouth to deny the impeachment. But a fist crashed into his teeth. "No you don't, you son of a "gun."

The pilot struck out, his fist crunched against tone. Someone grunted. Then Garry was in a whirl of fighting. Back to the wall, he protected himself as well as he could. A butting head crashed into the pilot's chin, drove his skull back against the stone. Shaking his head vigorously, he lashed out and his blows found their mark. Parker fought on, grimly silent, whilst his attackers made the darkness hideous with animal snarls. Garry's fists, his well-directed kicks, did terrible execution. First one, then another of his opponents retired momentarily, from the strife. But the unequal combat could have only one end.

The battling pilot felt hands clutch his feet, pull them out from under him. He was down, three heaving bodies on top of him. His arms, his legs, were pinioned to the ground. A knee ground into his laboring chest, an upraised knife gleamed bluely. "Good-bye, Naomi!" the unuttered farewell flashed through Garry's brain.

A new voice shouted, "Yoicks, hulloa! Up an' at 'em!" The knee suddenly lifted from him. He heard a smash, as of a body crashing against stone. The pinioning hands left his arms, his legs. He was on his feet. A fourth figure was there battling with two of his erstwhile attackers. The third lay, groaning, on the ground.

Parker plunged into the melee. But his aid was not needed. The newcomer was a whirlwind of explosive force. A sharp one-two sent one of the thugs reeling headlong against the wall. The third whirled, ran limping off into the darkness.

"Thanks, old man," Garry gasped. The stocky rescuer turned. Even in the dimness his hair was a red flame.

"That's all right. It was a bully good scrap while it lasted. But they nearly had you." The speaker paused suddenly, peered closer. "What the hell, an Aristo!" He turned on his heels, made as if to go without another word. Every line of his figure was eloquent of disgust.

"Hey—wait a minute. I'm no more an Aristocrat than you are."

The other turned back. "The devil you ain't! What are you trying to pull off on me!"

"No, that's straight. I'm not fooling you. Look—," he held out his identification disk. "The Aristos don't carry these, do they?"

"Then what's the idea of the masquerade."

"A little private matter."

"Oho! You're one of those bally asses that get mixed up with an Aristocrat dame. Flying high, my lad. Look out, that way lies trouble, and I mean trouble. But that, as you're about to say, is none of my business.

"Suppose we introduce ourselves. I'm Garry Parker, C Division. Or rather," a wry smile twisted his features. "I suppose it's ZZ division now."

"Oh, yeah? One o' the Won't-Workers, eh? Well, me lad, yours truly is in the same boat, or maybe a mite worse. Bill Purtell, at your service, called Purty by my friends, 'cause of my well known lack of beauty. And, in case you're inclined to get snooty, I'm entitled to stick ZZ special before my little 54687."

"ZZ special, eh. That's the new division I've been hearing about. Wish they'd assigned me to that. Anything would be better than the Idlers' Colonies."

"I'm not so sure. I'm not so sure," Purty drawled. "There's something that smells a lot off color about that ZZ special business."

"What makes you say that. I've heard that it's some kind of colonization scheme where conditions are bound to be a lot better than in those dam starvation camps."

"Yeah. I've heard a lot of guff too. But did it ever strike you that we've never gotten a single word back from the two groups that have gone off already? Whereas we are allowed to communicate freely with the old Colonies. I've done a bit of snooping around today, being, as it were, somewhat interested, and what I've heard somehow gives me the cold creeps."

"What did you find out?"

"Well, I got hold of one of the crew of the liner that took the first batch out. He told me that he knew some of the men and women in the gang, and every last one of them had been doing a lot too much talking about the rights of the Workers to equal opportunity, and things like that."

"Yes, I've just heard something like that myself."

"On the other hand," the red-headed rescuer continued, "this guy told me that just before they started, the Aristo in charge of the ZZ special made a speech to the colonists and the crew both. Even that sounds kind of funny to me. Our good, kind bosses aren't in the habit of making speeches to us Workers, explaining their orders. It's 'Go here. Go there. Do this. Do that,' with no whys nor wherefores volunteered. And we know better than to ask."

Garry thought grimly of his own experience. "That's true."

"This Aristocrat tells 'em that the Council has selected them because of their superior abilities to try a new stunt. The old Colonies have been just places where lazy Workers and insubordinate ones have been sent. But now they're going to found places where those who can't adjust themselves to this grand and glorious civilization can go back to conditions as they were centuries ago, before machines began to take over the work of man. They're going to give them the ancient tools; shovels, and ploughs, and hoes, and so on. And they're going to furnish 'em with seeds, and cows, and sheep. And then they're going to leave them to their own devices, to reproduce the ancient agricultural civilization. Said they'd been talking a lot about the good old days; here was a chance for them to see how they'd like the good old days. Now does that hokum sound reasonable to you?"

"Why not? It seems to me that it's a very good solution of what to do with the malcontents."

"Hell, the solution of that problem that would appeal most to the Aristocrats would be just to kill off every Worker that showed signs of doing some thinking for himself."

"Sounds simple. But I'm rather inclined to think that they'd be afraid to start that. After all, the Workers outnumber the Aristocrats, and, with all the Machines, are necessary to their welfare. Any such slaughter would be almost sure to start a revolution, meek and downtrodden as our people are. I don't say an uprising would be successful. Probably not. But things would be slightly uncomfortable for the upper class for a while."

Purtell looked at him strangely. "Yeah? Now I wonder if they aren't picking off the leaders this way?"

"Leaders of what?"

"Say, you don't happen to know Appak, do you?"

"Appak? Why, no." Gary's tone expressed his wonderment at this sudden change of subject. "Who's he."

"Never mind, if you don't know him." Then again that queer, speculative gaze. "Oh hell, you might as well know, the damage is done already, even if you are a spy. Not that I think you are," as Garry's eyes blazed, "you don't talk like one. Appak is the recognition signal of a world-wide Worker's organization that's been working undercover, trying to find some way of bettering conditions. We've hoped to avoid resorting to violence, but haven't gotten very far. I happen to be the leader of the Chemical Worker's section. Now you know why I'm so leery about this ZZ special proposition. I'm almost sure the Aristocrat police got in somehow and tumbled to my activities."

"Too damn bad. But maybe you're wrong. You'll know, anyway, what it's all about by this time tomorrow. Say, what do you think made these fellows jump me like that? I know they took me for an Aristocrat, but it's damned dangerous business murdering Aristos. Did they think they'd get away with it?"

"They were Gangmen, of course."

"Gangmen?" Garry's voice expressed his wonderment.

"Say, where have you been that you haven't heard of the Gangs. They're poor dubs that were ordered to the Idlers' Colonies, but didn't show up at ZZ. Crazy lunatics. They run off, hide in nooks and crannies like this, and pick off the Aristos whenever they get a chance."

"Do you mean to tell me that they're succeeding in a wild scheme such as that?"

"Hell no! Appak has tried to help them, but it's not much use. They last a couple of days. Then Sadakuchi's rats hunt them out, and—whiff—they're through. Ray-gunned on the spot. They're outlaws, you know."

"So that's it. Poor fellows. I'm sorry for them, even though they almost finished me. Might have been better for me at that. Well, I've got to get going. Thanks a lot, Purty. Sorry I never met you before. Not much chance of our ever seeing each other again. Good bye, and good luck. I hope you're all wrong in your notion about ZZ special."

"Me too, and many of them." With a jaunty wave of the hand, he was gone.

GARRY adjusted the disorder of his patrician costume, and emerged into the street again. Very different, now, was his progress. Before, he had been just one of the Worker mob, forced to jostle his way through the throng. Now, a path magically opened before him, cringing proletarians moved aside on every hand. A policeman saluted him snappily. One of the Lords of the Universe was honoring the lower region with his presence.

The disguised pilot reached an ascendor spiral, was carried rapidly upward. The broad sweep of Level Three spread before him the marble facades of the Aristocrat homes gleaming iridescent in the ever-changing pastel hues of colored lights. Then he was out in the open, under the eternal sky. He had arrived at Level Four, topmost layer of the many-strataed city, pleasure ground of the Master class.

In the distance, lofty pinnacles glowed silver in the light of a full moon that hung glorious against the gold-dusted velvet of a cloudless firmament. Here and there dots of light, green, and red, and blue, drifted slowly through the air; tiny gyrocopters bearing their patrician owners on pleasure bent. A soft, warm breeze fanned Garry's cheeks, fragrant with the sweet perfume of the vast garden in which he was.

Gravel paths, luminous seeming in their whiteness, wandered in graceful curves amid banked shrubbery and great beds of gorgeous blossoms. The scene was filled with beauty. Slow strolling couples, hand in hand, moved languorous along the winding ways.

A great silver shape soared through the sky, the broad surfaces of its far spreading metal wings flashing in the moonlight. "The ten o'clock to Frisco," Parker muttered, "wonder if Naomi managed to get away." Pat to the thought, a white shape, heavily veiled, came lissome toward him. "Garry, dear," the soft whisper thrilled him.

Near at hand was the welcome shelter of dark green shrubbery. The leaves rustled, as if in fond comment on the lovers' greeting.

At last, "Garry, I've been racking my brain ever since I left you. I've got a plan. Listen. Next Sunday—"

"Just a minute, sweetheart. Next Sunday's about a million years away as far as I'm concerned." Garry hesitated, then went bravely on, "I'll be five thousand miles away from here by then."

"Why, what do you mean?" The girl twisted out of his encircling arm, stood trembling, one white hand at her breast.

"I got my orders to go to an Idlers' Colony this evening."

"Oh, Garry. It isn't true, it can't be true!"

"Unfortunately, it can, and is. I'm afraid it's good-bye to all our planning."

"No, no! I won't let it happen!" The girl stamped an imperious foot. Accustomed from birth to the gratification of her slightest whim, she saw no reason why the great machine of world government could not be halted to suit her desires. "I'm going right to father and tell him that they're not to send you off."

A tender smile eased the tenseness of the man's drawn face. "And when he asks you why this sudden interest in a Worker, you'll tell him, what?"

"I'll tell him I love you, that I'm going to marry you."

"Upon which, of course, he'll snap his fingers in the Samurais' faces, scrap all his plans for world domination, and say, "Yes, my daughter. You shall marry this scum from the lower levels. What do we care for the Caste Law, for the very basis of the civilization we have so laboriously built up. Down with everything, Naomi of the Fentons loves a Worker!' Or will he just calmly have me whiffed out of existence?"

The girl's little fists clenched. "Oh, why wasn't I born a Worker. Then I could marry you, and go with you to the ends of the earth, and nobody would care!"

"Too bad you weren't," bitterly. "No, my dear, I'm afraid there's nothing we can do. If only I had a little time. Maybe—" the buoyancy of his scant years lifted him for a moment above the dark flood of disaster, "Maybe, after I get out there I'll find a way. There have been such things as escapes from the Colonies."

Naomi shook her head. "You forget, Garry, I'm to be married to Sadakuchi in a week."

"Hell! I guess we're licked, honey."

"No. Never!" A flood of passion shook the maid's slight body. "I'll move heaven and earth to save you! I'll do it, never fear."

"Never say die. That's the girl! But it's hopeless. It's good-bye, tonight. Let's forget our troubles. Look at the moon, how calmly she rides there, untroubled, mocking all our little worries." He was talking desperately, striving to quiet the trembling girl. "I've often wondered if man will ever reach her. You know, dear, we rocket pilots are well-trained in the science of the stars. And it's always tantalized me—the centuries—old longing of man to cast the dust of old earth off from his feet, and go adventuring out into uncharted space. I've read all the old books in the dusty archives of the Technological Library. Ancient names of men who spent their lives trying to find some way to strike off the chains that bind us to this little ball of ours.

"Oberth, and Pelterie, and Goddard, geniuses who dreamed nightly of far voyaging in those old days when man couldn't rise more than a half dozen miles above the surface. Our great rocket ships are the result of their labors, but one thing defeated them in their dreams. The lack of a fuel powerful enough to send the ships they planned out beyond the gravitational attraction of the Earth. Otherwise they had it all, down to the minutest detail of equipment, of navigation.

"I've read all their works, all the voluminous publications of the Associations founded to aid them, the American Interplanetary Society, the Deutscher Verein für Raumschiffahrt, the Société Astronomique de France. I've got all the data by heart, could guide a space ship out without a hitch. But in all the three hundred years of progress since they lived, and worked, and died, we have not yet solved that problem, a fuel that would take us to the moon."

"Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could do that," the girl murmured. "If we could step into a little rocket ship, right now, and fly away to the moon. We could be so happy there together, just you and I."

"I'm afraid you wouldn't like it much there, dear. It wouldn't be a very pleasant place to live. No atmosphere, no vegetation, just eternal pitted rocks and tortured shapes of lava. Boiling hot while the sun shines on the spot where you are, abysmally cold in the shadow of the two weeks' night. Nothing but a vast expanse of stony desert. Not a living thing to move across the landscape. A hell of loneliness."

"I don't care. Hell would be Heaven with you."

But all things have an end, even lovers' hours together. A red flash streaked across the sky—midnight.

"Good-bye, Naomi. God be with you."

"I won't say good-bye, Garry. Something tells me we'll see one another again, very soon."

"Good-bye, dear heart. Think of me sometimes." The man spoke calmly, coldly perhaps, but within him a seething inferno boiled and burned.

The green leaves rustled again. They parted.

NAOMI'S little Arrow whirred gently to rest on the broad roof of the domicile of Henry of the Fentons, in Division GI 2 D. To the dwellers in that luxurious home it never occurred that two thousand feet beneath them, in the same building, sweating Workers labored in torrid heat, forging beryllium-steel into grotesque forms that tomorrow would be assembled into graceful ships to rocket through the stratosphere.

The room she now entered was not large, but in the exquisite beauty of its furnishings it represented the very acme of the contribution Art and Science had made to the epicureanism of the world's masters. A soft glow, apparently sourceless, glinted from the graceful crystal flutings that segmented the irregularly curving walls in rhythmic symmetry. The spaces between were of opal; secret iridescent fires shimmering beneath the pearly sheen, while delicate traceries of gold and silver wandered in studied carelessness over the lambent surface.

The chamber was ceiled by a great sheet of transparent quartz, through which the panorama of the summer sky looked down in unmarred splendor. The floor was a deep green expanse, apparently fathomless, whose vast lucent depths seemed alive as changing shades of emerald and jade pulsed in unceasing shifting. This amazing carpeting was soft and yielding to the foot, so that one seemed to walk miraculously upon the surface of a calm, unruffled sea.

Naomi seemed a very nereid as she came softly into this ocean grotto. And the grizzled man, in the robes of a world councillor, who sat with closed eyes in a great chair of carved white coral that was none too large for his huge form might have been Neptune himself, save that the legendary beard was absent. Even in repose every line of his figure bespoke power and dominance.

The poise of his massive, leonine head, the deep graved lines that seamed his large-featured face, stamped him as one born to rule. No saving wrinkles of kindly humor touched the corners of his eyes. The mouth beneath his bulbous nose was harsh, and uncompromising. The thick fingers of his great hands were further thickened by the firmness of his grip on the chair arms.

No effete, decadent oligarch, Henry of the Fentons, but a fit descendant of the Henry Fenton who, three centuries ago, ruled a nation, secretly from behind a screen of gold.

The girl threw herself wearily on a couch cunningly fashioned in simulation of a matted clump of seaweed. For a moment she lay there quiescent, then seemed to gather herself for a mighty effort.

Father, are you asleep?"

Fenton's eyes opened, sought and found his daughter. Piercing eyes, whose black depths showed no softening for this only child. "No, Naomi, just thinking over the council meeting that has just ended.

Did everything go well?"

"Not at all. Na-jomba, the African, and Salisbury, the Australasian, still oppose my plan for execution of the malcontent Workers. They advance some weak-kneed humanitarian excuses, but I'm convinced that they're simply afraid of an uprising. As if the spineless slaves could find enough courage to dare defy any edict of the council! George of the Windsors was splendid, but Hokusai still holds aloof. Damn him, he won't come in with me until our Houses are united indissolubly by your marriage to Sadakuchi."

The girl shuddered, but said nothing.

I had to agree to a continuation of the namby-pamby ZZ special scheme that I was forced into two months ago. I tell you, those Africans and Australasians are degenerating. If this thing continues, the gulf between Aristocrats and Workers will be broken down, and this great civilization of ours will revert to the old chaotic conditions whose shibboleth was, " 'All men are created free and equal.' Bah!"

"What is this mysterious ZZ special business?"

"Something that decorative young ladies like you needn't trouble your heads about."

"But, father, I'm dying of curiosity about it," Naomi pouted. "You usually tell me everything—and you know I can keep a secret. Why all this hush-hush about just that?"

The councillor's face grew grim. "That will be enough of that. This matter happens to be particularly confidential, knowledge of its details is confined to the members of the Council and a few individuals necessary to the operation of the plan. There will be no more mention of it from you. Do you understand?"

"Yes father," meekly.

"Now, daughter, it's long past midnight. Off to bed with you."

"Just a minute. I want to ask a favor of you."

"Ask me tomorrow."

"Tomorrow will be too late. Please listen to me."

"Well, what is it?" testily.

"There's a group of Workers being sent to the Idlers' Colonies this morning."

"I have no doubt there is. That's true most mornings. That's just what I was telling those fools today. The Colonies are becoming overcrowded, additions are growing rapidly as more and more Workers refuse to obey orders, indulge in seditious utterances, or simply indulge in their own degenerate laziness. We'll soon find ourselves swamped—"

Naomi interrupted. "Please, father, I've heard that lecture so often. Mayn't I be spared it just this once? What I started to say is this. There's a rocket pilot booked to go, Garry Parker, C12574. Would you, just as a favor to me, have him taken off the list?"

This startled the great man. "Hello, what's this. What do you know about any Worker? Why this sudden interest in what's to become of one of them?"

The girl stammered in confusion as she sought frantically a plausible reason for her request. "Why—why, I d-don't know anything about him. Only—only that my maid Emma—that's it—Emma begged me to get you to do this."

"Your maid Emma—I never heard of anything so extraordinary in my life—your maid Emma dared to come to you with that! And you—a woman of the Fentons—instead of slapping her face for her insolence, actually relay her absurd plea to me. Are you getting chicken-hearted too? Come, come, forget that rot. Of course I'm not going to do any such thing. Forget about it."

Naomi was white faced, trembling. She had risen from her couch now, as her father had risen from his chair. She came closer to him, put a pleading hand on his arm. "Please, father, oh please don't say no. I'll never ask you to do anything for me again. Only say that you won't send Garry Parker away." An uncontrollable sob choked her.

The head of the House of Fenton grasped the now almost hysterical girl's shoulders, held her away from him as he stared searchingly into her eyes. His voice deepened to a bass rumble. "Naomi, you're lying to me. You couldn't be wrought up to this pitch of emotion over some Worker woman's paramour. There's something deeper than that behind this scene. Out with it, young lady."

The girl found some unsuspected well-spring of strength within her being. She whirled away from the hands that held her, then turned back to face the ruler of a hemisphere. Straight as a flame she stood there, defiant. There were no tears in her eyes, no sob in her vibrant voice.

"All right, then, if you must know the truth. I love him!"

The man stared uncomprehending at her. "You what!"

"I said I love him. And you shall not take him from me!"

THE father's countenance empurpled with rage. "You—my daughter—love a Worker! You—a Fenton—the betrothed of a World Councillor's son—what utter madness is this?" The deep-voiced accents came slowly, trembling with passion. "And you ask me to aid you in your lunacy. I wonder that you do not demand that I defy the Caste Law and permit you to marry him." He seemed on the verge of an apoplectic seizure, then the self-control with which a lifetime of domination had endowed him came to his aid. In a more natural voice he asked, calmly, "What did you say his number was?"

"C12574." Naomi searched the mask of her father's face for some sign of relenting, some intimation of the reason for this request. Henry picked up a communication disk carved from a single diamond. "Classification headquarters."

A pause. Then a voice. "Classification headquarters."

"This is Henry of the Fentons. Get this. Worker C12574 has been listed for ZZ division, this morning's shipment. He is to be changed to ZZ special. My personal order. I will telewrite you the confirmation in the morning."

The voice replied. "Very well, your Excellency. C12574 to be switched from ZZ to ZZ special. Thank you, sir."

"Right. See that there is no error." He put the disk down, and turned to Naomi, whose eyes were great black pools, liquid with unshed tear. "That's what we do with all malcontents, and Workers who have dangerous aspirations." There was a certain grim satisfaction in his tone. "Now, young lady, you will go to your rooms at once, and remain there until you send me word that you have come to your senses. Understand me. You are not to leave under any circumstances, nor communicate with anyone save your maid Emma, who will bring you food and tend to your needs."

"Father, what have you done to my Garry?"

The agonized voice would have moved a heart of stone, but the stern, parent was untouched. His only reply was a cold, "Go to your rooms."

The girl moved blindly toward the concealed entrance. As the panel opened at her approach, she turned back to her father, seemed about to speak, but swung again and went silently out.

Ordinarily a little thrill of pleasure, a glow of comfort warmed her as she entered her exquisite boudoir. But now the room blurred before her tear-filled eyes as she threw her throbbing body headlong on a couch, and great sobs shook her.

But Naomi was a Fenton. Vain repining, tearful acquiescence in adversity, were not in her nature. Very soon her sobs quieted. She rose, eyes blazing, little jaw set in firm determined lines. A dash of icy water removed all traces of the tearful interlude. A swift donning of a dark travelling robe. Then she turned to the entrance.

But the selective beam of the electric eye refused to swing open the portal. Already the orders of the master of the house had barred the door against her. The actuating mechanism that should have operated by the imprint of her image on a telephoto cell, remained dead. She stared uncomprehending for a moment, then a flush of anger suffused her cheeks. The little fists clenched. "Oh, despicable!" she exclaimed, "he's made me a prisoner, a prisoner in my own room!"

Well she knew the futility of battering furiously against the barrier. None but those for whom the mechanism was set could pass through. She seized her jewelled communication disk and, in a voice rendered almost unrecognizable by fury, called: "Father! Father!"

But the dead flatness of her voice against the tiny diaphragm told her that this device too was altered to enforce obedience to the edict her parent had but now pronounced. Her mind worked with the swiftness of desperation. Then, "Emma! Come here at once!"

IN his bare, stone-walled, stone-floored cubicle Garry Parker lay on his hard bed and stared into the darkness. Alone, now, with no one to comfort, no fellow Workers before whom to put on an air of uncaring fortitude, he gave himself up to the tortures of despair. No escape, no evasion of the inexorable decree that had smashed his life presented itself to him.

For a wild moment he played with the thought of refusing to present himself at ZZ, of joining one of the Gangs that roamed, rat-like, the dark passages of the city. But that was sheer madness. A day or two, perhaps a week, and the squat yellow Police would ferret him out, swift dissolution would dissipate every atom of his body in the searing agony of their hand ray-tubes. Garry was not yet ready to die. Perhaps his exile would have an early ending. No, the Gangs were not for him.

"Garry Parker, C12574! C12574! Garry Parker, C12574", a droning mechanical voice sounded in the blackness. He was being called on the disk.

"Garry Parker, C12574." He signified his attention.

"Classification Headquarters. Change of orders. Direction to report at Division ZZ, 10 A.M. Greenwich, cancelled. You will report at Division ZZ Special, 10 A.M. Greenwich this morning. Please acknowledge.

"I am to report at Division ZZ Special instead of Division ZZ, at 10 A.M., Greenwich, 5 A.M. local time. Garry Parker, C12574."

"Correct."

What was the meaning of this? Should he welcome this change, or dread it? Oh, of course. Naomi must have interceded in his behalf. Then that red-haired chap, Purty, was wrong in his pessimism. It must be something better than the Idlers' Colony. Good kid, Naomi. That was the toughest part of this whole business, leaving her.

GARRY sat on a pile of space suits, his back against the grotesque, goggle-eyed helmets. He turned to flaming-haired Bill Purtell, whose cheery "Hey fella, what are you doing in this galley?" had greeted him as he turned into the ZZ Special area, a half-hour before.

"Gosh, Purty, it's a long time since I had one of these things on. Last time was thrilling though. It was on the old Avalon, before they established separate levels for traffic in different directions. The Arcturus almost collided with us, just skimmed by, slicing a long sliver from our outer skin. You should have heard the air start rushing out. I was second relief on her then, my third trip out of training school, and I took a gang out to repair her.

"I tell you it was no fun, trying to keep one's hold on the slippery rounded surface of the old boat, even with the safety belts. She only made thirty miles a minute, but Lord knows that was fast enough to be ripped through the ether. We got her sealed up, though, with Alpha Insert, enough to finish the trip.[1] Her air was gone, and we had to put all the passengers and crew in space suits. The Old Man made a peach of a spiral landing, I remember. The Arcturus had put our landing wings out of commission.

[1] Alpha Insert is a compound possessing a remarkable affinity for metals of all kinds: its molecules hooked up in close union almost instantaneously, hardening to a toughness comparable with that of beryllium-steel itself.

"Great boat, that," he continued, musingly, "and great flying in the old days. This rotten hulk of a freighter reminds me of her. I didn't know there were any like her left."

Purtell extended his long, almost simian, arms in a luxurious stretch. "I've been parleying with one of the crew. Tells me that they got a couple dozen of 'em, freighting to the ZZ colonies. Thought I could dig some info out of him, but he didn't know anything about where we're booked for. Each one of these boats only makes one trip for ZZ Special, then goes back on its regular run. I don't care what you say, there's something not on the up and up about this. Otherwise why all the hocus-pocus, all the mystery?"

Before replying to his companion, Parker's eyes shifted from one to the other of the little groups of Workers in the huge cargo hold. About a thousand, he estimated, men and women. "You heard what the embarkation officer said. Some new islands have appeared in the Pacific, and have cooled off sufficiently for human occupancy. Fertile soil has been spread on them, and some shrubbery planted. The Council wants to determine if it would be possible to use them for a re-creation of the agricultural conditions of the past, and have selected some of the Workers to make the experiment. Seems fair enough."

"Not to me, big boy, not to me. That guy was altogether too glib in his speech." He shook his great head, that would have seemed too large for his short body were it not for the span of his great shoulders. Then a grin lit up the homely features. "Well, what's going to happen will happen. Meantime let's quit worrying."

But Garry could not let the subject drop. He indicated a group of some two hundred men and women, who, slumped in the center of the great hold, showed only blank faces, and black lustre eyes. "You don't mean to tell me that bunch are dangerous radicals."

Purtell grinned. "No. That occurred to me too, and I had a chat with one or two of them. They're the same dumb obedient slaves that most, of the rest of our class is. But, it's the same old story, it was to somebody's interest to get rid of them. That old grey-bearded guy," indicating with a jerk of his spatulate thumb, "had a young wife that the chief of his division kind of liked. This other dumb-looking moron was framed by one of the yellow cops who was caught off post. An' so on. No, young fella' me lad, you can't convince me that there isn't something smelly in all this." Garry shrugged. No use pursuing this line of talk.

"BY the way, Purty, I see by the yellow of your clothes that you were in the Chemical Division. What threw you out?"

"I was in the Bureau of Fuel Research. Nice easy job, too, just watching the photoelectric eye do titrations. Old stuff, but it was kind of fascinating to see the burettes shut off by themselves just as the indicator pink faded out into white at the end-point. Then they got this new nascent hydrogen all set. The big moguls decided that there was no further progress possible along those lines. If they'd asked me, I could have told them different."

Parker shot a startled look at the ginger-headed chemist. "Why, what do you mean. Are you kidding, or..."

"No, Pm not kidding," drawled Purty. "It's true enough that theoretically the greatest amount of power can be obtained from the combustion of the mixture we've got now. Unless some new elements were to be discovered, they give us the greatest output of energy per unit of weight. But," and now a certain earnestness invaded the ordinarily mocking face of the speaker.

I've got an idea that the speed of the reaction can be increased. That would give more power per unit of time. Understand? It wouldn't give more power for the same amount of fuel but would permit us to apply more power in a given time. And since what we're after is acceleration, swifter increase of speed, that's what we're looking for."

"Hey, that's right up my alley." Garry's face glowed with interest. "How do you think that could be accomplished?"

"By a catalyst."

"A catalyst?"

"Gee, don't you know what that is? The influencing of a chemical reaction between two substances by a third substance that itself remains unchanged. Why, the very oxygen in the air we are breathing right now owes its ease of production to catalytic action.

"I suppose you know it's obtained by the heating of a mixture of potassium chlorate and manganese dioxide in the generators between the inner and outer skin. The heat utilized is from the jacketing of the rocket tubes. If the manganese dioxide were not present, and potassium chlorate used alone, the heat required would be so great that this method would not be practical. Yet the manganese dioxide remains unchanged, and can be used over and over again."

"So you think that some similar substance can be found to speed up the reaction between the nascent oxygen and hydrogen sufficiently to double the rate of acceleration now possible?"

"Double, hell! It might multiply it ten times."

"Then interplanetary flight is by no means an impossibility!" Garry was off on his hobby again.

"I don't know what you're talking about."

"Look here—" And the two forgetting their situation, became engrossed in an intricate scientific discussion. Even a sudden overpowering ammoniacal aroma, brought by some wayward current from the other hold, in which mooed a herd of cattle, did not serve to recall them from their speculations.

Meanwhile the ships sped through the stratosphere toward its mysterious goal. In her control cabin the first officer scanned the Pacific with his televisor. A vast, tossing waste of waters, it had long ago been swept clear of navigation when the commerce of man had taken to the air. Here and there a green island, or a little sprinkling of islets, broke the monotony. Suddenly the mate turned to his chief with a puzzled frown.

"The visor seems to be out of gear, sir. There's a small area right at the point we are supposed to land that does not register; the screen just blanks out when I focus on it. I've never seen anything like it before."

The captain scratched a gray, disheveled head. "Yeah. That's in the orders too. 'You will note carefully,' says the Commodore, 'that th' point of arrival is subject to pecooliar conditions which render it a blind spot to raydio commoonication, both visual and aural'. All o' which means that there's one blessed spot on this here Earth o' ours safe from their snoopin' an' their pryin'. We're to take our bearin's from the Island o' Levis, that's ten miles nor nor' east o' Yedor Island."

"This is a queer trip, isn't it, captain? What do you think of it?"

A GREAT cloud of smoke issued from the time-blackened clay that was clenched between the yellowed fangs of the veteran airman. "I don't think nothin' of it. Man and boy for forty year I've flown th' air, an' I ain't thought nothin' about any one o' th' thousands an' thousands o' queer trips I've made. Low grade intelligence they got me rated. All I know is to obey orders. Well, mebbe my intelligence is low grade. But I take notice o' one thing. I trained hundreds o' youngsters like you in my time, nice young fella with high-grade intelligences what did a lot o' thinkin' about the trips. Ambitious—like you. All pepped up to get promoted up to one o' them express liners, with all the noo-fangled automatic devices.

"Well, they all got their promotions. Yeah, they got their nice shiny liners to run. But where are they now? Ninety-nine out o' a hundred got fed up, an' are in the Idlers' Colonies, rottin' away. An' poor old Cap Funston, who ain't got enough intelligence or ambition to get promoted, is still knockin' about, comfortable as a bug in a rug, runnin' a rusty old freighter that's too no-account to have any o' them noo-fangled doo-jiggers put on it." The ancient's bright eyes twinkled shrewdly as he rapped the dottle from his pipe against the metal edging of the televisor screen.

The young cadet-pilot concealed a superior smile. The old fossil really thought he was putting something over. Condemned to this superannuated scow whose top speed was a mere thirty miles a minute. Faugh. Not for him. Better one glorious year at the throttle of one of the super-liners, loosing at a touch of a finger the leashed power of the lightning, than a half century of dry rot. He wouldn't go off half-cock. By golly, he'd obey orders till he was in a position to give them himself.

His keen eyes roamed the instruments, searching for an opportunity to display his alertness. They lighted on the fuel gage.

"We're running awfully low in fuel, sir. Looks to me like we won't have enough for the return trip to New York."

Funston tugged at his beard. "Worryin' again, son. It don't pay. We only took enough for the out trip to leave capacity for an extry heavy cargo. There's plenty more on that Levis Island. We refuel there."

"But that will take at least forty-eight hours."

"In a hell of a rush to get back, ain't yuh. Now, I'm thinkin' o' asking permission to overhaul there. Got an idee that a couple o' the rocket-toobs is pitted." He glanced at the position-light, reached a gnarled hand for the mouthpiece of the communication system by which his craft was controlled. "Stand-by to change over," he snapped.

"Stand-by to change over," echoed the order through the spaces of the flier. The dungaree-clad crew leaped to the levers jutting from the walls. The sudden bustle reached the absorbed two, brought them back from the far reaches of interstellar space, whither they had soared on imagination's gossamer wings.

"Hello, sounds like we're getting to where we're going," grinned Purty.

"Sure does. Let's try to see what it's like." Garry shoved back the metal shield that covered a thick quartz porthole. Outside, as yet, could be seen nothing but the void of the stratosphere.

"Change-over. Hup!"

The men of the crew shoved their levers over. A vast groaning and shrieking clamored. The obsolescent turbines were protesting against being once more prodded into, life.

Purtell crowded his ungainly head close to Garry's. "Move over and give another fellow a look." All through the crowded hold there was a jostling and scuffling as eager Workers sought positions of observation. But many there were who remained apathetically quiet, beyond curiosity, beyond hope.

A VAST dark green expanse swam into sight, the curvature of the earth's surface distinctly apparent, as a great inverted bowl. The bright rays of the sun gleamed back from the tossing waters. As the ship zoomed lower, two minutes specks appeared in the vast emptiness, close together at first, then slowly separating as the heaving Pacific flattened out.

They grew into tiny islands. Garry glimpsed on one a group of low squat buildings, slowly moving dots that must be men, a towering aerial mast. Then the island circled out of his vision as the ship turned in a great arc. Below, rising rapidly toward him, he saw momentarily the other islet, a rocky waste, save near the shore where the green gleam of vegetation showed in. the sunlight. He saw a great black mountain—then the curve of the still descending hull cut off his view. Again there was nothing in sight but the slow rise and fall of a calm, far-spreading sea.

"Stand-by to go ashore!"

A babel of shouts, calling voices, conflicting orders, arose. A great hole opened in mid-deck, as a tremendous cargo sling shot rapidly downward with its human load. Again, and again, till the thousand men and women had been landed on a shelving, sandy beach. Then the cattle, paralyzed with fright, milling wildly as they were released from the great bucket.

Queer shaped implements that afterwards they learned from the instruction sheets fastened to the bundles were axes, spades, hoes, rakes, plows, tools of a primitive agriculture unearthed from some long forgotten stores, or fashioned anew from museum specimens. Cases of canned foods.

Swiftly the hovering rocket ship was emptied of its freight. A parting call came from the grizzled captain as the bucket clanged back into its berth. "Good-bye, good luck!" The silver shape, its vast wings glinting, soared majestically toward where blue line on the horizon showed the location of the other island. The outcasts of civilization were alone with their fate.

"Nice mess!"

Garry turned to the speaker, a tall, lean, saturnine individual whom he was later to know well as Dore Swithin. "Yes, isn't it."

"Hell of a note, I'll say. Dumping us here like this," freckle-faced Purty spoke up. "Look at that bunch o' dubs."

About half of the colonists had dropped, dumbly, among the jumbled piles of supplies, listless, brooding. The rest, younger folk in the main, were racing about, calling to one another, inspecting their new home with avid but unthinking interest. A group was dashing inland, intent on reaching a group of long, low structures, built of black stone, that bulked some hundred yards away. Others were crowding about a stream that cut through the grassy plain on which the beach bordered. None seemed disposed to take thought of the next step, of making provision against the coming night, the future.

Garry felt vaguely uncomfortable, chilled despite the heat of the tropic sun beating down. Something queer about this place. Was it that mountain, a towering mass of black stone, its base a bare half-mile away? Yes, it seemed somehow threatening. But that was not all. Something else. Something wrong about the meadows nearer at hand. He gazed at them. Lush green grass, low bushes, their leaves motionless in the windless air. No trees. Well, they'd hardly bother to bring trees here. The cattle were already scattered, grazing peacefully. Yet he could not rid himself of his nebulous discomfort.