RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

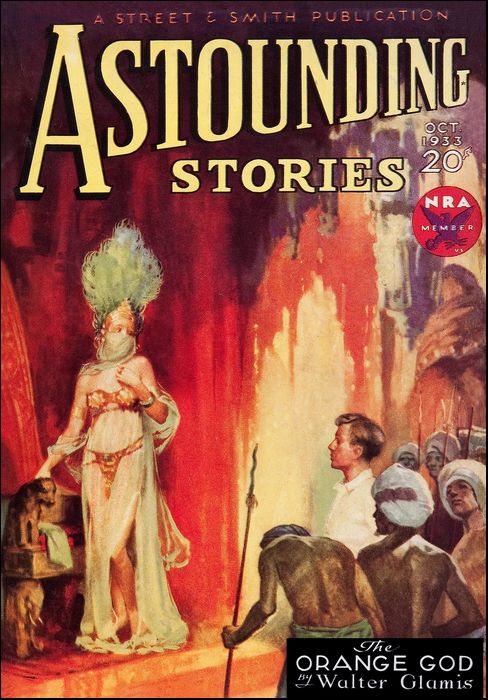

Astounding Stories, October 1933, with "Fire Imps of Vesuvius"

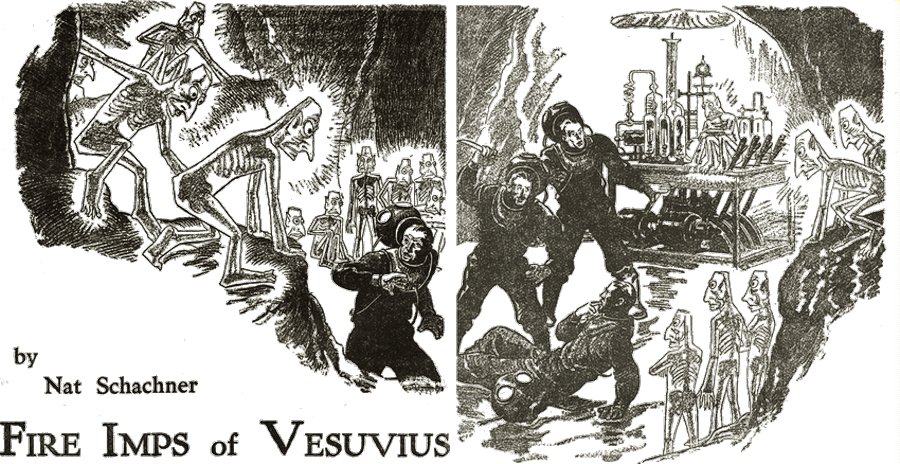

A piercing whistle rang from his lips—and the imps poured out.

These staring, fire-bodied things were the creatures of Vesuvius.

IT MUST have been four in the morning, when the dawn wind blows coldest, that Geoffrey Clive was awakened by the most terrific crash ever heard this side of hell. He sat bolt upright, the sleep dashed out of him, just in time to hear a second tremendous report that shook the bed with its concussion. The hotel heaved convulsively.

Geoff struggled to his feet and ran to the window, throwing wide the shutters. The harbor of Portici glowed blood-red in a strange unearthly glare; the sea whipped violently back and forth.

Vesuvius was in eruption!

Geoff snapped out of his daze and swore bitterly. He had not bargained on this when Carewe's urgent cablegram had brought him posthaste across the Atlantic. He was too late!

Professor Ernest Carewe, formerly noted vulcanologist at Harvard, had inspired young Geoffrey Clive with a vast enthusiasm for that fascinating subject. When Geoff had followed the normal course of college athletes and become a bond salesman, Professor Carewe had indicated his disappointment.

"A good vulcanologist joining the Philistines," he snorted.

"One must make a living," Geoff pointed out.

"You wait. One of these days I'll be leaving Harvard, and I'll take you with me."

Geoff grinned wistfully. There was nothing he wanted more. "I'll wait," he promised.

Six months later, Professor Carewe had been appointed assistant director of the Royal Observatory at Mount Vesuvius, the only foreigner to be so honored by the Italian government. Geoff's heart had turned somersaults when he read the news, but days passed, and months, and no word from Carewe.

Then came the bombshell. A cable from Carewe, cryptic, urgent.

"Drop everything and come at once," it read. "Need you badly stop terrible danger." The signature was E.C.

The cable seemed purposely vague; even the signature showed an attempt at concealment. Clive had not hesitated a moment. Carewe was no madman; if he called to his former pupil for help, there was reason for it. So Clive had caught the first boat to Naples, taken the train to Portici, arrived there too late to proceed with the electric up to Observatory Ridge.

Now he was too late, Geoff groaned to himself as he dressed in desperate haste. Carewe was trapped in the observatory, trapped by an eruption that seemingly he had anticipated. What did it mean? He hesitated, reached swiftly into his trunk for his automatic, thrust it into his coat pocket.

In thirty seconds he was out of his room, pushing his way through a struggling, wailing mass of scantily clad guests, abject fear stamped indelibly on every countenance.

Clive burst into a world of brimstone and destruction. The morning sky was a blaze of fire and thick black smoke. Huge cindrous rocks hurtled high overhead.

He was out in the open country soon. Straight ahead Vesuvius loomed, its flanks enswathed in dense, steamy clouds, its summit wreathed in flames. There were incessant rumblings and groanings, punctuated by terrific explosions. The ground trembled and heaved underneath; already, back in the city, buildings were crashing; the cries of the entrapped people reached all the way to Clive's ears.

Through the thick gloom, fetid with the smell of brimstone, he met villagers fleeing destruction, stumbling on their way to the coast. Geoff's heart ached within him, but, with teeth clenched, he forged steadily ahead. His job was to save Carewe.

He was halfway up the northwest side to Observatory Ridge, where the shallow valley through which the railway runs on a raised embankment makes a sweeping curve, when he heard a great hissing and splashing. He rounded the curve, and stopped short, despair welling in his heart.

A great river of fire confronted him, a gigantic serpent of molten stone, red within and hissing at every pore. It was moving down the valley, slowly but implacably, steaming, detonating, already lapping hungrily at the railway embankment.

Clive groaned. Had he come so far only to meet with death in its most fiery form? His eyes searched eagerly around. There, on a siding, stood a hand car, abandoned, forlorn. But what good was it! True, the twin steel rails were still inches above the lava flow, but in minutes they, too, would be covered.

It was madness to try to run that searing gantlet, but Clive, his mouth grim and hard, did not hesitate.

He ran to the hand car, was climbing on board, when he heard a whirring, roaring sound that seemed to come out of the sky. He stared upward in astonishment, his hand already on the handlebar.

An airplane was plunging through the steamy atmosphere in a long, twisting nose dive. It was heading directly for the crested lava. Geoff sucked his breath in sharply. But it banked as the left wing tip almost touched the fiery menace, and came crashing to the ground not twenty feet from Geoff. A helmeted figure pitched violently out, lay sprawled.

Clive looked at the narrowing path through which the rails went upward, looked again at the sprawled, silent figure of the aviator, and grinned wryly. "I am a fool," he grunted, and jumped off the car. He ran to the limp body, knelt in swift appraisal, to find life quite strong, heaved the man over his shoulder, sprinted back to the hand car.

In seconds he was at the handlebar again, took a deep breath as he viewed the fiery furnace ahead, bent low, and pumped furiously. The little car leaped forward like an unleashed steed, straight up the path of the shining steel rails. Already the first ripplings of lava were washing against the wooden ties. The hand car shot into it, Geoff pumping with all the strength of his muscular back. The heat struck him full in the face like a blast out of hell. His clothes seared in a dozen different places, the skin on his hands clung smoking to hot handlebars, but he did not relax his furious pumpings. The lava lapped over the rails, the ties burned from under, sagging the steel ribbons perilously. But a last desperate spurt shot the car out into the open again, past the blazing inferno, into a comparatively cool area of rock and smoking soil. Then, and then only, after first carefully setting the brake, did Clive collapse.

He came to a while later, to find the strange aviator bending over him and shaking him roughly.

"Get up," the man ordered harshly, in Italian. "What the devil are you doing here?"

Clive understood; he could converse in the other's language, after a fashion.

He sat up indignantly, forgetting his hurts, and stared at his discourteous inquisitor. The aviator's helmet was thrust back, disclosing dark, proud features.

"I might ask the same question of you," Clive said with heat. "It should be enough for you that I saved your life."

"You saved my life?" the aviator asked incredulously.

"I'm beginning to feel sorry I did," Clive retorted. "When your plane crashed, I pulled you through that pleasant little valley on the hand car."

The man stared back at the unbroken level of lava. The rails were gone now, completely engulfed. He passed a hand across his forehead.

"Ah, yes, I remember now. A bit of flying rock hit my wing; I lost control." He turned ungraciously to the American. "Thanks," he said. "But I must ask you again who you are and what you are doing up here."

"You're too damned inquisitive," Geoff said coldly, "but I am in too much of a hurry to quarrel now. If it means anything to you, my name is Geoffrey Clive. I am an American, and am going up to the observatory to rescue my friend, Professor Carewe."

The man's eyes flashed keen interest. "Ah, yes, Carewe; I've heard of him. He is assistant director, is he not?"

"Yes. And now that I have told you who and what I am, I would thank you to reciprocate." There was a dangerous edge to the irritated young man's voice.

"Ah, yes." Strong, even teeth flashed in a faint smile. "Tomasso Mercelli, chief of public safety. I, too, am going to the observatory."

The observatory was plainly visible now, a cluster of buildings on a steep, slanting ridge. To the northeast rose the crater, enswathed in flame-shot clouds, rumbling and belching.

"Let's get going, then," Clive said.

The hand car shot up the steep incline under Geoff's sturdy ministrations, through hissing steam and rain, ash and falling rocks, while Mercelli held on to the side of the bounding car to avoid being thrown off.

The run was short, not over a mile. They reached the end of the tracks: the terminus of the railway and the commencement of the funicular that took visitors by cable car to the true summit of Vesuvius. The observatory looked deserted.

CLIVE jumped off, dashed for the domed central building with great leaps, his heart pounding furiously. Was Carewe still alive? Could he explain what had happened? Where did Mercelli, who was right on his heels, fit into the picture? Questions that could only be answered if Carewe was alive.

He raced into the great central chamber, where the delicate seismograph instruments were embedded in solid rock.

"Professor Carewe!" he shouted.

The sole occupant of the vast room, a slight, elderly man, with thinning gray hair and heavy, bushy eyebrows from under which absurdly young and alert blue eyes sparkled, looked up from a sheaf of papers he was calmly examining. Vesuvius in eruption, the world blazing in ruin around him, meant only more accurate and exact observations on volcanic disturbances.

The blue eyes lit up with recognition. He placed the papers in his hands very carefully back on the desk, bent over to take another look at the violently jumping stylus of the seismograph chart, and straightened up.

"Geoffrey Clive—I expected you about this time," he said simply. "Come, we have work to do." All in a calm, very matter-of-fact tone, as though Geoff had walked in from the next room—as though nothing untoward had occurred.

Clive grinned in spite of himself. He knew the old professor's idiosyncrasies. "But what——" he started, when Mercelli stepped forward.

"Professor Carewe?"

"Yes," said the little man.

The government official clicked his heels and bowed. "It is with regret that I must inform you that you are under arrest."

Clive started violently, but Carewe said quietly: "Why?"

"It has reached our ears that you are the head of an anti-government plot, you and Emanuel Campanella, your coworker. You have by some devilish means brought Vesuvius to life."

"The source of your information is Fraschini, I suppose?" Carewe asked.

"Who else?" said Mercelli, drawing his gun and covering the little professor. "He is loyal; that is why he was made director. For a week now strange fires have dropped out of the sky, burning their way through roofs and walls, into the houses of the chiefs of the government. Last night a dozen high officials were found burned to death, warnings on asbestos boards beside their crisped bodies threatening all others with a like fate.

"At midnight, Director Fraschini phoned, fixing Vesuvius as the source of the plot and implicating you and Campanella as the ringleaders. He said he was going to stop it at the risk of his life. Then the call broke off suddenly. He phoned back. No answer, as though the wires had been cut. Soldiers are marching to surround the district. I came direct."

Passion darkened his countenance. "Where is Director Fraschini—and your co-conspirator, Campanella?"

Carewe said calmly: "They are both in the crater of Vesuvius."

Mercelli stiffened. "Dead?" he ejaculated.

"I didn't say that. Campanella disappeared last night at ten; Fraschini went out at midnight. They have not come back. There was little love lost between them. Campanella was anti-government; theoretically he was an anarchist. He used to expound his philosophy to me, but I never took him seriously. Fraschini—well, you know his loyalties."

"He was a devoted member of the party."

Carewe sighed. "Possibly! I preferred Campanella. But personal likings do not excuse the horrible things that have been done. Vesuvius in eruption, blotting out cities, causing untold suffering to thousands of innocent people; assassination by things of fire hurtling through the air—these are the workings of a depraved being. We must put a stop to them."

Mercelli said coldly: "You lie.

You and Campanella both have done this. You have killed Director Fraschini."

Carewe sighed again. "No one is so stupid as a bureaucrat. We shall all go into the crater, and stop it—if we can. Time presses; each moment we stand here talking vainly means possibly hundreds of more lives lost. Come." He made a movement.

Mercelli raised his revolver. "No!" he said. "Your trickery shall not help you. Your fellow conspirators are waiting there. You think to get away."

Carewe faced him steadily, not a tremor of fear on his serene countenance. But his left eyelid flickered significantly.

Clive, who had been listening in a daze of bewilderment, came to himself with a start. He left his feet in a long, vicious tackle. His shoulder caught the knees of the official. The gun exploded.

Mercelli crumpled under the terrific impact, hit the floor with a thud that left him curiously limp and unmoving. Geoff scrambled to his feet, to find the little professor dabbing at a scratched cheek with a handkerchief.

"Thanks," he said calmly, as if being shot at were an everyday occurrence. "Now we can start. I had to wait for you; I am not strong enough physically for what is ahead. It may be too late."

"How about this fool?" asked Clive. "We can't leave him unguarded. He's just stunned."

Carewe looked contemptuously at the by now groaning figure. "Thickheaded, like all officials. They see only the obvious. Tie him up, so he won't interfere."

Clive found lengths of good stout rope and trussed Mercelli securely to a chair. He stepped back and surveyed his job with satisfaction. "That will hold him for a while."

The professor led the way into a smaller chamber, obviously a storeroom. He rummaged among the piled effects until he found what he was after. He drew out two strange suits—for all the world like diving outfits, except that they were made of a flexible gray asbestos material. Then, while Clive watched curiously, he drew out two helmets, again like diving helmets, enormous, with tremendously thick glass windows for the eyes. The helmets were of the same asbestos-like material, except that they were rigid. Within, Clive glimpsed two tiny tanks, fastened at the top.

"What are we going to do with those things?" he ejaculated. "Go diving?"

Carewe smiled thinly. "Yes, volcano diving," he said. "They are my own invention. I completed a supply of them a month or so ago. These suits are fire-resistant; even the glass is specially prepared for that purpose. Within the helmets, you may have noted, I have oxygen tanks for breathing, as well as tiny sending and receiving units, so that the explorers can talk with each other. I tested them out recently and found them not more than comfortably warm in a bath of one thousand degrees Fahrenheit.

"I had intended exploring some of the old vents of the volcano. Campanella stole a march on me and found something down there that made him master of the volcano. I still don't know what it is he found." He shuddered, and his thin, scholarly face was grim. "But whatever it is, the result has been horrible."

They were clambering clumsily into their outfits as Geoff asked: "How do you know this Campanella is responsible?"

Carewe nodded. "I know. Campanella is a splendid vulcanologist, quite superior to Fraschini, the director, who is a surly, stupid sort of a lout. But Fraschini stood high in political circles, and accordingly, when the old director died, he stepped over Campanella's head, even though Campanella was the logical successor. It was known that Campanella was not exactly in sympathy with the government."

They had their helmets on, but Carewe kept on talking while clamping them into place. The communication units were functioning now.

"Campanella brooded over the slight," Carewe continued. "His normal anarchist leanings blazed into hot flame under the driving force of his personal indignity. He inveighed to me by the hour against all officialdom, seemed to regard himself as the appointed savior of his country. I tried to calm the man, but it was of no use.

"When I finished these suits, he slipped out one night with one. I saw him come back in the early morning. He was strangely exultant. 'I found old passages in the crater,' he whispered excitedly, 'and people down there!'

"I stared at the man, and told him in abrupt language that he was crazy. He was hurt at that, and withdrew into his shell. He stalked to his room, muttering.

"He avoided me after that; but I know he used to slip out of the observatory when he thought every one was sleeping. I saw him once at midnight, toiling up the path by the funicular, grotesquely clad in one of my asbestos suits. Last night I sat up purposely, saw him slip out. I kept on watching. To my surprise, at midnight, another figure crept out, similarly attired. I watched it until the mountain had swallowed it up. Then I ran to the director's room. He was not there. They never returned. Instead, Vesuvius broke loose."

Clive's head was in a whirl at the strange, fantastic recital. Campanella, embittered anarchist, in the depths of the volcano, unleashing horrible forces in his resentment; Fraschini trailing him, possibly lost, dead, in the fiery bowels; Mercelli, the chief of public safety, with the full weight of the Italian government behind him, bound helplessly in a chair; strange hurtling fires released on the world to work destruction—and, above all, old Vesuvius herself wreaking death and ruin on an innocent countryside because of man-made hates and contentions. He went grim at that. Could those two puny mortals control the mighty forces that had been loosed?

"We are ready now," Carewe was saying in his dry, calm voice.

The two men stepped out of the observatory. It was raining now; thick, weighted rain of the consistency of mud. The sky was dark and shot through with blinding lightning flashes.

Carewe's voice came to him. "We follow the funicular, to the level of the crater. Keep right behind me, or you'll get lost." The microphones were working perfectly.

It was a desperate, soul-racking climb, but finally, panting and weary, they reached the edge of the crater, and looked down.

TREMENDOUS, awful sight! The floor of the crater was a full thousand feet down, and partly covered with a lake of fire. Three huge vents spouted liquid magma. One wall was blown away, and a broad river of lava cascaded over. Fortunately, they were on the opposite wall, away from the area of eruption; otherwise they could not have lived an instant.

Geoff's heart sank. How could they ever find a practicable passage into the depths of that inferno! It seemed impossible for human beings to exist an instant down there. Campanella and Fraschini must have been burned to a crisp long since.

But Carewe was peering eagerly down into the abyss. Then he straightened suddenly. His voice came through the receiver with exultant clearness. "I've found the way! Come on," he cried, and without waiting, slid over the edge. Clive gritted his teeth, jumped unhesitatingly after.

They half slid, half fell down a steep declivity. Clive pawed desperately for support, envisioning with horrible clearness the lake of molten fire that awaited below, if his fall was not broken. The next moment he pounded into Carewe's asbestos-clad body, brought up sharply by a jutting ledge.

Carewe struggled to his feet. A smooth, round orifice, extending blackly downward, yawned in the side of the precipice. The professor shot into it, feet first. Geoff took a deep breath, heard a muffled shout.

Then he, too, lowered himself into the bore, into jet blackness, and let himself go.

He seemed to drop interminably through space; then his feet struck with a solid jar. It had not been more than six feet. An arm came out of the inky depths to steady him, a voice resounded exultantly in his helmet.

"This is the way, all right," Carewe was saying. "We'll find what we're after at the bottom of this tunnel."

"More than we bargain for, possibly," Geoff assented dryly.

He stared into the palpable blackness. His gaze riveted. "I seem to see a faint glow, or the reflection of a glow, miles away."

"Come on, then," Carewe said impatiently, and gripped his arm.

Together they stumbled along what seemed to be a steeply slanting runway, not over six feet in diameter. They resembled two moles, crawling through the secret bowels of the earth.

The faint reflected glow at the end of their path grew slightly brighter. The tunnel swerved slightly to the left. The explorers stopped short, with a simultaneous cry. The round walls of the tunnel glowed cherry-red for an unfathomable distance ahead.

Clive groaned. "That settles it. We can't go any farther. Those walls are red-hot rock. This vent leads straight down to the central fires."

Carewe shook his helmet grotesquely. "Nonsense. Campanella made it. If he did, so can we."

"But——" Geoff started to expostulate, but was cut short.

"I'm going to chance it. I think our suits will protect us, if the red-hot walls do not extend too far. You are at liberty to turn back."

Clive choked back the furious words. "Lead on," he said deliberately.

"Good boy," said the professor.

The tunnel was a little wider now; smooth, as though artificially hollowed. Without hesitation, the two adventurers pushed into the fiery path. This was indeed to be a test of their asbestos suits; if they failed, they would be crisped to ashes.

The round cylinder of walls glared dazzlingly into their eyes. Underfoot the stone was soft and sticky, almost molten, and dragged at their thick asbestos shoes with an evil, sucking sound.

The interior of their suits grew rapidly warm; their bodies dripped rivulets of perspiration. Even the oxygen they breathed became moist and steamy. Clive gasped and pushed on as rapidly as he could, literally dragging Carewe along with him. The professor, with his lesser stamina, was weakening fast. Yet, rapidly as they traveled, there seemed no end to the fiery walls.

Carewe sagged suddenly. His voice came faint. "I—I can't go any farther. Leave me here, and go back. Save yourself."

Clive laughed harshly through the streaming sweat. "Can't return. It's too late. It's forward for both of us."

He stopped, thrust Carewe's unwieldy bulk on his shoulder, and staggered on.

The glare from the white-hot walls dazzled him; the blood in his head was roaring and beating with great pulses. Every breath of hot oxygen into his lungs was a stabbing agony. The weight of the limp body on his straining shoulder dragged him down, but with clenched teeth and fixed, glaring eyes he struggled on. Would the inferno never end?

He was delirious now; he was sure of it. When a man began seeing devils, he was through. For in front of his wavering vision, right in the center of the fiery path, staring at him from unwinking, red, round eyes that bulged out of a red, wedged-shaped face, stood the figure of a tiny being, not over three feet tall. It seemed transparent, as though fashioned of tinted glass, and warmed with an inner glow of shifting waves of heat.

Geoff groaned and almost dropped his limp burden. The vision was too frightfully clear to be anything but the last stage of delirium. He could even see the pulsation of a vitreous heart in that glassy body, could follow the sharp outlines of coiled intestine, ending in a stomach-like sac.

Geoff awoke from his daze. The figure in the path had not stirred, but he did not care. "Out of my way, nightmare or devil out of hell!" he shouted insanely, and staggered forward. Instantly the creature moved backward, with a queer, shuffling glide. Clive laughed crazily, and weaved in pursuit. A strange chase in the burning depths of the volcano!

Suddenly the walls seemed to expand rapidly, rushing away from him with infinite velocity. The tormenting figure of the imp grinned owlishly at him; only somehow it had dissociated itself into a multitude of leering, grinning brother imps, squatting on their haunches in a huge semicircle about him. Then everything exploded in a great puff of billowing steam, and Clive sank, unconscious, Carewe limp beside him.

Clive opened his eyes wearily. His head was throbbing, the skin of his face felt parched and cracked. Water—cool, blessed water—his whole being craved for it with a fierce, torturing thirst. A deathly silence enveloped him. He was lying on his back in a huge cavern, smooth and round, with walls of a strange, vitreous, transparent substance, illumined by interior fires. The imps, hallucinations of a fevered brain, were gone!

"I knew it," Clive groaned, and twisted painfully in his bulky outfit. Then he blinked, and sat up with startling suddenness. Through the heavy glass of his helmet he saw Carewe, still outstretched on the vitreous floor. But a figure was bending over him, fumbling at the helmet clamps. A human figure, dressed in ordinary street clothes. He was not encased in an asbestos suit, though the transparent ground glowed with iridescent fires. Something gleamed in his right hand, as he fumbled and worked with his left. It looked to Geoff's startled eyes like the keen blade of a knife.

All thought of pain left him. He clambered to his feet as swiftly as he could, lurched over to the kneeling stranger.

The man looked up at him, startled. He evidently had thought him dead. He bounded upward; the weapon drew back as if for a driving thrust. Carewe rolled over, groaned, and sat up weakly. The scene seemed to penetrate his dazed brain, for with a little exclamation, he, too, staggered to his feet. The stranger glared at the ungainly figures, and crouched. Clive moved forward slowly, tense, waiting for a sudden move.

The professor shifted his head, cried out suddenly: "Fraschini!"

The name made reverberant clamor in Geoff's earphones. He stopped dead in his tracks, looked at the crouching, soundlessly snarling man. He, of course, had not heard the exclamation. Fraschini! That must be the director of the observatory, the man who had followed Campanella down into the bowels of the volcano. No enemy, this. But why had his knife been in his hand as he fumbled with the professor's helmet?

There was no time for coherent thought. Carewe had unfastened the front clamps of his helmet, thrust it back on its rear hinge, exposed his parched, seamed face. The skin looked slightly parboiled. "Signor Fraschini!" he cried. "We are friends. I am Carewe; this is an American friend. We came to help."

The man slowly straightened. He was of medium height, a thin, dark-skinned Neapolitan. His straight black hair slicked greasily back from a low, sloping forehead. His black eyes were narrow and slitted. They stared appraisingly at the two Americans, watchfully, deliberately.

Carewe's mittened hand was extended in greeting. Geoff was unfastening his helmet; evidently there was breathable air down in this marvelous glassy cavern, nor could the temperature be excessive.

Suddenly, just as Clive had thrown back his helmet, inhaled the warm, close, but not unpleasant atmosphere, Fraschini relaxed his guard. Clive had a feeling that the man had come to some decision. The director thrust his knife into a sheath dangling from under his coat; his face lit up with a surprised, effusive greeting.

"My esteemed colleague, the American!" he cried, and pumped the extended mittened hand with his bare one. "I did not recognize you. How in the name of all the blessed saints did you come down here?"

"By the same path that you and Campanella took," Carewe said gravely. "Vesuvius is in eruption; the whole country is devastated. I came for the same reason that you followed Campanella—to stop it, if I could."

Fraschini's eyes narrowed; his brow darkened perceptibly.

"Campanella, the traitor!" he spat. "It is true; I knew he was up to deviltry. I followed him secretly. I was too late; he got away; he is hiding somewhere in these innumerable chambers, his devilish work going on."

Clive watched the man with distaste. He did not like him. Yet he murmured polite greetings when the professor turned and introduced Geoff to the director.

"How do you account for this cavern, with its glowing transparent walls, and air?" Carewe asked.

The director shrugged his shoulders. "No doubt it was formed by a huge bubble of volcanic gases when Vesuvius was plastic. The tremendous heat vitrified the lava into transparency. Those flames we see must be the reflection of far-off fires in an active vent of the volcano. That is why it is not too hot in here. As for the atmosphere, there may be an opening somewhere into the outer world, through which the cold air is sucked as the heated air escapes."

"A very plausible scientific explanation," Carewe admitted; "yet somehow I have a feeling that this cavern is artificial, formed by thinking beings."

"Bah!" Fraschini scoffed.

Clive spoke suddenly. "What about the fire imps, director?"

Carewe looked at him in amazement. He had been unconscious when Geoff had seen, or thought he had seen, the weird little beings. But Fraschini's dark face went white; he took a short step backward. "You—you saw them!" he croaked.

"Yes."

The director looked fearfully around. The sweat oozed from his oily forehead. He burst out: "Those damn devils! Campanella has them trained; they do his bidding. Let us escape, before it is too late!"

Carewe was staring strangely. "The fire people; the crazy myth come true. Then Campanella has found the means to send them out of the volcano, through the air, to definite goals."

The director looked his astonishment. "What do you mean?"

Carewe explained. The warnings delivered to the government officials, the final wholesale destruction of the leaders when the threats had failed. It was the story Mercelli, the chief of public safety, had told.

"Then we must find him!" Fraschini shouted. "We must find and kill him!" There was no questioning the hate that gleamed from his slitted eyes. "I have been searching all day, through passage after passage, and found no trace."

Clive's brows contracted, but he said nothing.

"Let us work fast, then," said Carewe. "You will need your suit, Signor Fraschini. And we need water badly."

"I have my suit hidden in a crevice; I took it off when I found this place. It was more comfortable without it. As for water, I found a pool. I'll get some. Then we can start."

"We'll go with you," said Clive.

The man's eyes darkened. "No!" He spoke hastily. "It is but a little way." And before Geoff could answer, he was off across the great glassy cavern, trotting fast.

Clive watched him reach the wall, worm himself through a hole in the side, disappear from view.

After a perceptible interval, Fraschini was seen climbing out of the hole, clad in his asbestos suit, the helmet thrown back. He was carrying a soldier's canteen.

"Here, drink," he said, lifting the flat metal container, and tilting it. The Americans needed no second invitation; they drank eagerly. It was warm, stale, and heavily impregnated with sulphurous gases, but to the thirsting men no wine had ever tasted so ambrosial. "I took the precaution to carry a canteen down with me," Fraschini explained.

Surfeited, the Americans relaxed after the last drop had been drained.

"Now we go this way," the director said, after they had clamped the helmets into position and the communicating sets were working. He pointed to a wide, angled passageway that sloped into darkness from the farthermost rim of the cavern. Clive turned a longing glance at the little hole Fraschini had crawled into, but followed the other two obediently.

IN SILENCE they plunged into the gloomy passage, faintly glowing from the reflected light of the cavern. It led by devious twists and turns deeper and deeper into the bowels.

Suddenly the gloom lightened. There was a deep, reddish glow ahead. Fraschini stopped short, whispered: "He is there. We must be careful."

Clive smiled grimly to himself as very quietly they crept forward. The passageway curved abruptly into a larger cavern, smooth, glassy, lit up with internal fires, like the one they had previously quitted.

But what held their startled attention was the sight of a man, clad in an asbestos suit, the helmet tilted back, stooped over, intent upon something. Clive caught a profile view of a tall, tawny-haired Italian, with straight, firm nose and ruddy cheeks, of the type that Giorgione loved to paint. Then Geoff sucked his breath in sharply. For the man was bent over a series of levers connecting to a glinting, metallic platform, from which strange vitreous tubes rose in a forest of columns. They glowed with a bluish flare. On the platform stood a flame-tinted imp, his transparence showing clearly the beat and pulse of human-seeming organs, his wedge-shaped face upturned submissively to Campanella, as to a master. Directly above, in the curved-over ceiling of the cavern, was a hole. Liquid magma filled it from brim to brim; it raced along in swift current, upward, yet miraculously not spilling a single fiery drop into the chamber beneath.

Carewe gripped Clive's mittened hand hard. Here then was the arch-villain, the brilliant vulcanologist, who, to gratify his anti-government sentiments, was plunging countless thousands of innocent people into ruin and death. Geoff started forward in blazing anger. His one thought was to kill the author of all this misery. For all he knew, Vesuvius overhead was still belching forth its far-flung rocks; all of Italy rocking in the throes of tremendous earthquakes.

Fraschini's hand pulled him back. "Are you mad?" he whispered in a fierce, low voice. "We will all be killed if you give us away. Look what is there!"

Clive stopped short, and looked. He saw then what he had not noticed before—a horde of fire imps squatted against the farther wall, their vitreous, transparent bodies almost imperceptible against the vitreous wall. Their round, staring eyes were all concentrated on the man at the levers and their comrade on the platform.

Carewe whispered: "We must wait for our chance. What can he be doing?"

The three men crouched in the angle of the passageway, watched the proceedings with bated breath. Campanella straightened from his stooping position. He nodded to the queer little fire imp; pulled a lever. Instantly the vitreous columns glowed with fierce fires. The metallic platform sparkled with a thousand dancing flames. It quivered and shook in tremendous vibration. The flames leaped fiercer. Suddenly the imp shot straight upward, as though hurled from a catapult. With dizzying swiftness he hit the hole in the ceiling. His body disappeared into the flaming, flowing magma, was swallowed up in fire. The racing current quivered like a jelly for a moment, then smoothed out to a rippleless flow. The imp was gone, swallowed up.

Carewe's voice trembled in Clive's earphones. "God, what are we up against? That devil Campanella has subjugated the imps of hell and the forces of science to his will. That vent above must lead straight up to the mouth of the volcano. He has mastered somehow a directional force that sends those messengers of death on their appointed courses. Who knows what official is going to be stricken down with that thing of fire?"

Fraschini said nothing, but Clive could see a peculiar light in his narrowed eyes through the glass of the helmet. While they crouched there, unwilling spectators, three more of the imps were sent on their errands of doom. Then, seemingly, Campanella had enough. He shut down the tubes until they stood lifeless; his mouth moved in words that were soundless to the listeners. He was addressing the squatting, watching imps. They rose, as at a signal, melted imperceptibly into a farther passage.

Clive waited a minute. Then he whispered: "Now's our chance!"

Three shapeless, bulky figures ran clumsily out into the great cavern, straight for the tall, absorbed figure of the man. He did not seem to hear their approach until they were almost upon him. Then he looked up, startled. His fingers went to his mouth, but Geoff dived headlong, catching him around the knees, and brought him crashing to the ground. Fraschini and Carewe flung themselves upon the fallen figure. There was a moment's struggle. Then Carewe's voice, sharp, commanding: "No, don't!"

Clive gathered himself up in time to see Fraschini's knife descending in a flashing arc to Campanella's lolling head. Geoff reached out and caught the director's wrist in a grip of steel, twisted sharply.

Fraschini howled with pain as the blade clattered to the ground.

"Damn you," he cried furiously, "why did you do that?"

"We do not permit cold-blooded murder!"

Fraschini's face in the helmet was a mask of hate. "He deserved it! He is a criminal, a menace to the nation!"

Carewe snapped: "Very likely he is, but the law will take care of him. We are not executioners."

The wounded Italian groaned weakly. The three men threw back their helmets.

"Sit up," the professor said sharply. The man did so, rubbing his great tawny head with an asbestos-mittened hand. There was a long gash across his forehead, where he had hit the floor. The helmet had twisted off its hinge; it lay, battered and useless, on the ground.

Carewe observed his groaning colleague with more of sorrow than of anger in his bright blue eyes.

"Why did you do these horrible things?" he asked softly.

Campanella stared back defiantly, proudly. "For the sake of the people. I gave the officials fair warning before I acted. They have tyrannized over us too long. All government is tyranny. It is our duty to get rid of it, and make the people free."

Carewe looked at the seated man with a tinge of scorn, of loathing.

"Whatever your political views, you have gone too far. You pretend to love the people! Yet you loose the incalculable forces of Vesuvius to overwhelm thousands of innocents, to bring untold ruin and suffering to the very ones you claim to cherish. You are a monster, a beast, to be crushed without mercy." The little man's eyes flashed with passion.

Campanella raised his tawny head suddenly. "What is that you say?" he cried. "Vesuvius is in eruption?"

Carewe said coldly: "Do not pretend ignorance. The whole countryside down to the harbor—Portici, Torre del Greco, Torre Annunziata—are buried meters deep in lava, because of what you have done with the volcano."

The man's eyes opened with horror. "I—I have done this!" he gasped. "I swear to you I know nothing about it! Since yesterday I have been down here; my plans were carefully laid. It is true I have sent my messengers to destroy all bureaucrats—they deserved it—but to loose the terrible fires of Vesuvius—no! They are my people down there, the people I am laying down my life for! Would I wantonly destroy them?"

The passionate appeal made the Americans pause. Fraschini's coarse voice interposed.

"You can fool soft-hearted Americans with your lies," he jeered, "but I am too smart for you. Your own confession is enough. You deserve death, and I shall execute the sentence."

Fraschini's arm flashed up suddenly, knife in hand. Clive gathered himself for a desperate spring. Campanella merited death, no doubt, but he could not stand by and see him killed by lynch law. The blade was halfway down, when the mitten of Campanella's right hand slipped off. Quick as lightning, the bare fingers raised to his mouth. A shrill, piercing whistle echoed through the cavern.

The sudden movement, the unexpected sound, froze every one in his tracks. The knife poised in mid-thrust. A swift pattering came to the astounded men, a pattering that grew into roaring volume. From a dozen unseen corridors there poured a stream of fire imps, their red, transparent,. angular bodies glowing angrily, hundreds of them.

In seconds they had surrounded the little group of humans; a thick, compact circle, glowering, threatening. Though they were a dozen feet away, Clive could feel on his unprotected face the heat of their bodies. The knife fell from Fraschini's hand; his dark face oozed terror.

Campanella rose calmly to his feet., "The tables are turned, gentlemen. You forgot my good friends, the fire people." He turned and hissed something very rapidly. An imp on the outskirts of the throng scampered obediently to the platform and returned, forthwith, holding a coil of steel wire in his vitreous hands. Where he held it, it glowed red-hot. He tossed it to Campanella's feet from a distance.

Clive looked keenly about him. There was no chance for escape. The circle of glowering imps was solid; a fiery mass that would burn to a crisp any venturesome being who tried to force his way through.

Campanella picked up the steel wire, proceeded very deftly to tie up the three men. He talked all the while with the calm poise of a professor lecturing his class. His voice was easy, unhurried.

"Very convenient friends, these imps of mine. I found them on my first exploration, living down here in the bowels of the volcano, unknown to man. A strange race, evolved on different lines from any above. You will note their bodies; they are glassy, hot. The basis of their life substance seems to be silicon, rather than carbon; the heat of their bodies, their particular form of metabolism. Queer, that life down here should have molded itself on lava-like forms; but that shows the infinite adaptability of nature."

He bound Fraschini's arms with particular unction, disregarding the hate in the slitted eyes. "I made friends with them somehow, learned their language. Very simple, and very obvious, once you have the clue. I needed their help for what I intended. I had worked in secret for years on my machine to catapult material things long distances through the air. Originally I intended sending bombs by it, but that would have been too messy; might have killed innocent people."

Carewe snorted as he lay helpless. Campanella smiled queerly. "It is true. These people lent themselves much better to my scheme. They traveled along the beam, found their victim, destroyed him, and came back along the radio beam to their starting destination. They rather enjoyed it."

"What are you going to do with us?" Clive interrupted.

"Ah, that is a question," the man mused. "Fraschini I have no qualms about. He is a scoundrel. But you two have blundered in on me. I cannot let you go out into the world again to betray me."

He straightened up and hissed staccato sounds. The great circle of fire imps melted, moved with unobtrusive steps into the passageways from which they had previously erupted.

Campanella waited until the vast, rounded cavern was silent. "I'd rather not have them see me put you to death," he acknowledged, and strode over to the platform of the machine.

Geoff struggled unavailingly with his bonds. "Can you do anything?" he whispered to Carewe.

"Not a thing," the professor answered weakly.

Fraschini lay as if paralyzed, the fear of approaching death clammy on his forehead.

Campanella returned, holding a pencil-like steel rod in his hand. "A burning device to slit your throats," he said in what sounded like a regretful voice.

The tawny-haired man bent toward them. They were lying flat on their backs, near the entrance to the corridor from which they had wandered into this hell. Clive stared fascinated at the approaching, innocent-seeming rod. The tip was already glowing redly. It approached closer, was almost at his throat. He could feel the heat now, the bitterness of death welling within him.

Out of nowhere a dark body hurled past him, struck with vicious impact against the absorbed killer. He went down with a crash. The heating rod fell close to Clive's body. The two figures rolled over and over in a thrashing, struggling tangle of asbestos-clad arms and legs. But Clive was intent on something else.

Very carefully he rolled against the glowing point of the rod, so as to contact the tip with the steel wire that bound him. The wire glowed and snapped. Even through his asbestos suit he could feel the tremendous heat. Campanella and the strange asbestos-clad figure were still struggling in a heap. Fraschini's eyes were fastened on them, his tongue screaming thick utterances.

Clive rolled closer to the professor. "Quick," he whispered urgently. "Move over to the rod. Burn your wire. I've snapped mine already."

Carewe nodded, twisted himself around until he made contact. The wire melted and parted. Clive braced himself for a sudden surge to snap his bonds, when the stranger thrust Campanella violently to the ground, rose, a pistol in his hands. With his free hand, he opened his helmet, but the pistol never wavered from the group.

Clive burst out involuntarily: "Mercelli!"

It was the chief of public safety, whom they had left securely tied at the observatory!

THE MAN turned at the sound of his name, and his dark features lit up. "The Americans," he said with satisfaction. "I've made a complete haul, I see." He smiled ironically. "You are not expert at ropes. I had no trouble in untying myself. I found one of your suits, and followed, at a distance. I wanted to see what your game was. I found out. This time you shall not escape me, my friends."

The director literally whined in his eagerness. "Free me, signor. I am Fraschini, the director of the observatory."

Mercelli spun around, lifted his hand in salute. "I am indeed honored in being of assistance." He knelt warily, his pistol covering the others, and unbound him swiftly.

The director arose, stretched his cramped limbs. Carewe made a movement, but a quick, warning nudge from Clive stopped him. They lay quiescent, seemingly helpless in their bonds. Campanella lay where he had fallen, sullen, resigned.

Carewe said quietly to Fraschini: "You will tell this stupid official that my young friend and I are not conspirators. That we came here to help you and fight Campanella, the man responsible."

Fraschini towered over them. No longer was there terror in his eyes. Something subtler, infinitely more crafty.

"You must be mad to think I will not expose your treasonous plots," he sneered. He turned to Mercelli. "These two men, Campanella and the American, plotted to overthrow the government. The other man"—he pointed to Geoff—"I never saw before, but he is a companion of Carewe. I discovered the conspiracy, phoned headquarters at once. Then I followed them into the depths. They caught me, were going to kill me. While they were debating how pleasant my death should be, they quarreled. Campanella overcame the other two, and boasted that he was going to rule Italy alone as soon as he was rid of all of us."

Clive lay astounded at the smooth treachery of the man.

"He lies!" he cried.

Mercelli turned sardonic eyes upon the prostrate American. "I am certain he tells the truth!"

Geoff said nothing; little things weaved crazily through his brain.

What was Fraschini's reason for accusing them? Then the problem wove into a blinding white pattern.

"I've got it!" he declared triumphantly. "Fraschini is the real traitor, and is trying to cover his tracks! It is true Campanella has been sending the government leaders to their death; he admitted it. But it is Fraschini who has loosed the volcano. I remember now; the passage where he had his suit hidden, and didn't want us to follow him. Search that place, Signor Mercelli, and you will find the proof of all this."

The director's face twisted into insane rage. "You lie, you dog!" he screamed. Swift as light, his knife whipped out of his coat. For the first time, Mercelli's pistol wavered irresolutely; a frown deepened on his forehead as he glanced swiftly from accuser to accused.

Clive knew what was in Fraschini's mind; he intended to strike home before Mercelli could interfere, and silence the man who had said too much.

With a sharp, whispered "Now!" to Carewe, he heaved at his sundered bonds. They gave, and almost simultaneously he jerked upward and forward. Fraschini was lunging for him, glaring his hate. The professor was struggling weakly to his feet.

Mercelli started forward in protest, stopped as he saw the bonds fall from Clive; his pistol came up wildly. The cavern echoed with reverberations; the shot had missed. His finger was squeezing trigger again, but Geoff was off the ground in a crouching leap. Fraschini's knife was swooping downward, when a shrill, piercing whistle froze the wild melee to stone.

Forgotten for the moment in the storm of accusation and counteraccusation, Campanella had seized the opportunity to call upon his cohorts for aid.

Fraschini's rage turned to abject terror. "Mother of God," he screamed, "the fire imps!" He swerved from his forward rush in time to avoid Clive's hurtling impact, cast a look of frenzy over his shoulder, and darted, swift as a cat, for the passageway that led to the upper world.

Mercelli lowered his gun, bewildered at his colleague's sudden flight, saw Geoff whirl on his toes, raised it again.

"You fool," Geoff yelled, "run for your life! Look at them coming!"

Mercelli's head shot involuntarily around, saw the ancient vents disgorging their horde of the strange, glassy, red creatures. His jaw dropped, the gun fell nervelessly from his hand. Campanella pointed, not at the astounded trio, but at the tunnel into which Fraschini had darted. The imps swerved in strange discipline, came pattering across the glassy floor.

Clive snapped out of his daze. He jerked Car ewe's arm roughly, yelled in the astounded official's ear: "Run for it. Up that way. It's our only chance."

Like arrows from a bow, the three men shot into the tunnel mouth, barely a hundred feet in advance of the red horde. Campanella was shouting something, but what it was they could not hear.

Up, ever up, they sped, as fast as they could in their unwieldy suits, through the gloom-shrouded, twisting tunnel. It was getting hot; perforce they had to stop and clamp their helmets into position, glancing fearfully behind for sounds of the terrible fire imps. Only a faint patter came to them; they were some distance behind.

Without speech they panted up the tunnel, burst finally into the glowing larger cavern where they had first met Fraschini. Exclamations resounded simultaneously in the three helmets. At the farther end, where the path went upward to the outer world, they saw Fraschini, helmet clamped down, recoiling upon them. The mouth of the upper tunnel was blocked with the glowing bodies of fire imps. They had hurried around on a short cut to cut off the humans from safety. Below, the steady patter of feet grew louder and louder. They were trapped!

Fraschini wheeled around to race back, saw the figures of the three men at the mouth of the lower tunnel. A sharp cry of despair came to them in their earphones. Evidently he knew the game was up. He swerved, and darted headlong for the hole in the side wall where he had kept his asbestos suit.

Geoff shouted: "Quick, after him! Head him off! That's where he controls the volcano! He's going to do some mischief!" Geoff dashed ahead, Carewe right on his heels. Mercelli panted behind, sorely bewildered at the swift turn events had taken.

But they were too late. Fraschini was running like a frightened hare. They were fifty paces behind when he dived into the opening. Geoff reached the spot where he had disappeared, looked back a moment, to see Campanella running out of the lower tunnel, a horde of imps at his heels. Then he dived through. Bodies tumbled after him. They found themselves in a tortuous, narrow, dead-black passageway, through which they stumbled, and bumped, and cursed. Fraschini had the start on them, and knew the way.

At length they burst into dazzling light, into a small, irregularly shaped cavern. They stopped short in their tracks, astounded. There was no roof to the chamber, at least so far as they could see. Overhead, seemingly for unfathomable heights, great clouds of steam swirled and eddied, sucking upward, yet always renewed. At the farther end there was no wall, only a curtain of fire, smooth, unbroken, and rippleless. To one side stood an enormous block of black basalt, surmounted by a strange wedge-shaped idol of the same material. Directly at the base, in a thin slot in the stone, there angled outward a long polished rod, also of basalt. Fraschini was standing next the altar, his back to the flaming curtain of fire, his mittened hand resting on the lever. In his unwieldy asbestos suit, with its rounded helmet and unwinking, goggling eyes, he seemed like another idol or demon of the underworld. The flames cast strange shadows on the gleaming helmet.

Clive thrust forward.

"Stop!" Fraschini's voice rang desperately. "One move forward, and I'll blow the volcano and all of us to hell!"

Clive paused uncertainly. Carewe plucked at him. "For God's sake, don't move! The man is insane. He can do it, too." Mercelli stood rooted, speechless. He was out of his depths.

Fraschini heard the professor's whispered warning, gained in boldness. "You're right for once. I'm the boss here; and you'll do as I say. Fools, all of you! You, too, Mercelli! With this lever I control all Italy. Campanella played right into my hands. I followed him weeks ago, found this, and kept quiet. He was killing off the leaders. I loosed Vesuvius, to give the rest of them a taste of what I can do. When I have the nation thoroughly terrorized, I shall offer to stop the volcano, if they accept me as dictator."

Clive balanced on the balls of his feet, waiting like a hawk for the slightest relaxation of vigilance on Fraschini's part. To distract his attention, he asked, with an effort at casualness: "Just how does that lever work?"

Fraschini fell for the trap. "Simple. I found it here. Some old underground race must have built it, maybe the ancestors of the fire imps themselves. At the top of the slot it is neutral, has no effect. As you pull it farther down, it opens old vents deep down in the volcano. You'll note it's at the halfway mark now. That fiery curtain in the background is the result. It wasn't here when I started this. It was enough to cause the eruption. There is no doubt that if I pull the lever all the way down, it will open every old vent Vesuvius ever had, tap the vast reservoir of internal fires, maybe even the sea. That steam overhead looks as though water is already seeping in. In that case the volcano will go up in one great explosion, and take half of Italy with it—the greatest cataclysm ever seen!"

He did not notice Clive edging gradually forward. Geoff had made up his mind to risk all on one desperate rush, to thrust the director away from the lever. To gain his purpose, he taunted: "You wouldn't dare blow it up. It would be the end of you, too."

"Just try me and see!" the man retorted. "I can't get out, anyway, unless you fools make Campanella call off the imps. Tell him I'll blow him up with the rest of you."

"I'll do that," Clive agreed, and pretended to turn, swinging in a way to gain momentum for the last desperate jump.

"Oh, no, you don't!" Fraschini brought him up sharply, tightening his grip on the lever. Clive teetered on his toes, the other two behind him tensed to join the suicidal spring, when suddenly Geoff relaxed, with an exhalation of breath.

"That's better," jeered the director. "I thought you wouldn't like to go up in fire!"

But Clive had seen something. The rocky wall to the left of the curtain of fire and somewhat behind Fraschini, was bulging out. Greater and greater grew the bulge, until the thinning outer layer, heating to incandescence, resembled a gigantic, iridescent soap bubble. And like a soap bubble, it burst with a soundless plop.

Crowding fire people peered through the burst shell of rock, seemed about to throw themselves forward, when, as if in obedience to some signal from behind, they disappeared.

The three men were rigid in their tracks. Fraschini, with his eyes riveted on Clive, mistook their frozen astonishment for fear. His hand rested significantly on the lever.

"Just a little pressure, and up we go—all of us! Pleasant thought, isn't it?"

But they were not listening. For a figure crept slowly out of the glowing aperture the fire imps had made with their fire-hot bodies. A figure that had hardly anything human left about it. It was clad in an asbestos suit, but the head was uncovered. Clive shuddered. He could hear the gasps of his companion. For the head was charred and smoking, a grinning, seared mask. Only two eyes, bright and glaring, could be seen in that hideous caricature of a face.

Campanella! His helmet had been battered and twisted in that first fight of theirs, could not be affixed to the asbestos suit. Crawling bareheaded through the superheated passages, following his obedient fire people as they blasted a channel through solid rock, borne up by an indomitable will. His hands were curved in their mittens, as he crept soundlessly in back of the unsuspecting director.

The three men waited breathlessly, silent, immobile; while Fraschini, unsuspecting the creeping doom, kept up his grandiose declamations.

Campanella was almost directly in back of him now. Geoff could hear his heart pounding, could almost hear the heartbeats of his companions. Then the poor, burned caricature of a man straightened up and lunged forward with clutching hands.

Some intuition must have warned Fraschini. For he turned suddenly, saw the leaping apparition, screamed, and thrust up a warding hand. With the other he clamped down hard.

Geoff shouted in warning, shot desperately ahead to grab the lever, reverse it. But it was too late. The curtain of fire bellied forward in an awful, soundless gust; the mountain seemed to crash and tumble down upon them. The last thing he saw was Campanella pulling his enemy back into the flame, a look of terrible triumph on his fleshless face.

Geoff felt himself lifted upward, swirled into great steamy clouds. There was the feeling of racing motion, then the gusty masses changed to black, roaring oblivion.

IT WAS three days later, they told him, when he awoke, to find himself in a hospital bed in Naples. The spotless white beds on either side of him held Carewe and Mercelli, both badly burned, but not so seriously as Clive. That last jump of his had carried him almost into the curtain of fire.

"He blew up Vesuvius," Geoff groaned.

Carewe smiled weakly across to him. "Not quite," he corrected. "The lever didn't work as he thought. It blew up the chamber, all right; but as a matter of fact, so diverted the volcanic fires that Vesuvius stopped erupting. They tell me it is quiet as a ghost now."

Geoff drew a scalded arm across his forehead. "But how did we get out?"

"The chamber was a fumarole," Carewe explained. "That was why it was full of vapor. It opened to the outer crater. When the smash came, we were caught up in the blast of expanded steam, thrust up and out onto the summit. They found us there, unconscious, the soldiers who were searching for Mercelli."

Mercelli leaned over with difficulty, swathed as he was with bandages. He seemed oddly embarrassed.

"I'm sorry," he said, "for having acted the fool. But I never thought Fraschini was a traitor."

Carewe said kindly: "We know you only did what you conceived to be your duty." Then he added with subtle sarcasm: "Even government supporters have their weaker vessels; nor have they a monopoly on nobility."

Clive raised his weak voice. "I honor Campanella," he said. "A terrorist, true, an assassin, but for a cause he conceived great. When he found Fraschini ready to destroy half Italy, he sacrificed himself, and—what was harder still—his ideals, to prevent it. A man!"

Carewe nodded gravely. Even Mercelli's hand went, half unwillingly, to a characteristic salute.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.