RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

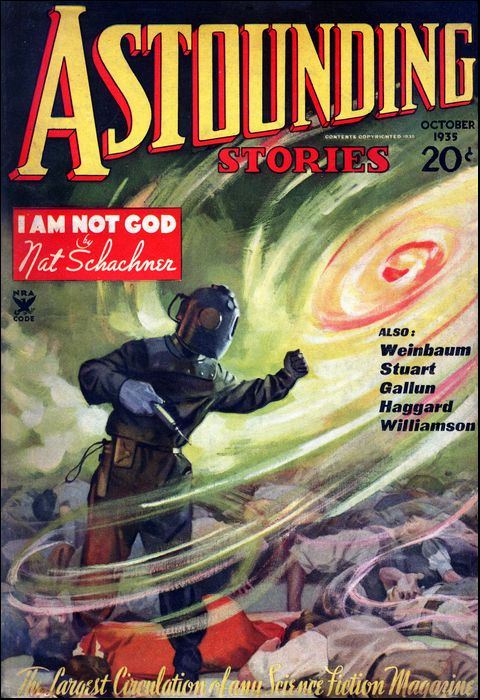

Astounding Stories, Oct 1935, with first part of "I Am Not God"

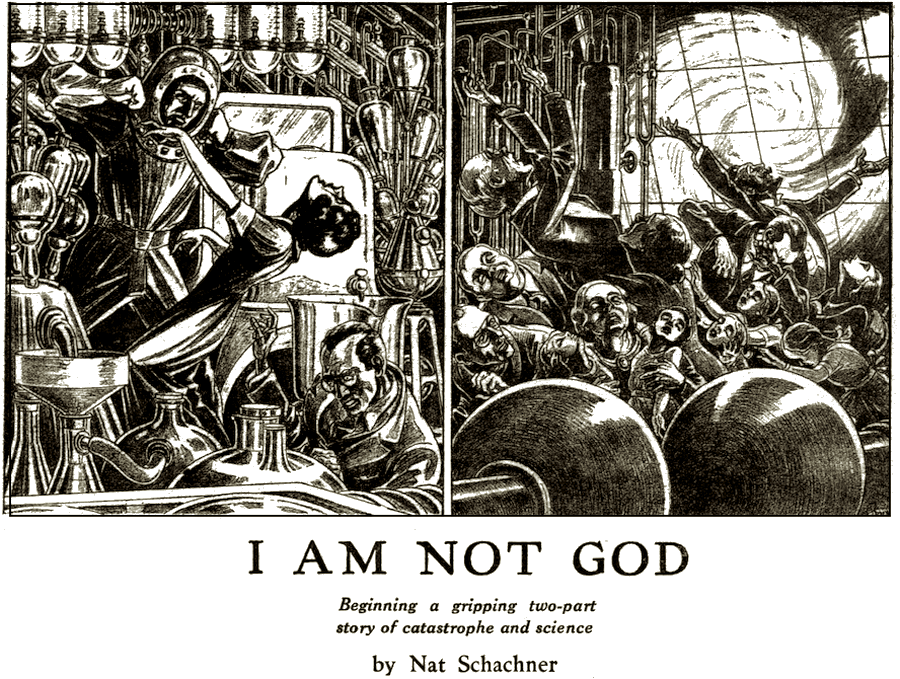

Deborah!She was trying to prevent him from loosening his helmet,

while all around him humanity was succumbing to the nebulat gas.

THE first appearance of the nebula was unexciting enough. It was small and inconspicuous, and but one of a dozen faint blotches of deposited silver on the exposed photographic plate of the new two-hundred-inch telescope. The astronomer in charge of the observatory checked the plate against the older ones in his possession, and found that this was a new nebula. But so were several others in that particular area—which was understandable enough, considering the increased light-gathering power of the recently installed instrument.

He therefore duly noted its position, jotted down that it was of the order of the twenty-fifth magnitude, gave it a catalogue number, G 113, and filed the plate away for further routine study. The discovery did not rate a line in the world's newspapers. But the scanty data appeared, in consort with other anonymous numbers, in the next issue of the Astrophysical Journal, a month and a half later.

It was there that Stephen Dodd first came across it. Ordinarily it would have meant very little to him also. But it happened that he was just then in the throes of a highly upsetting bit of research, and there was not a nebula in the entire universe, big, small or medium-sized, remote or near, in which he was not feverishly interested.

For the thousandth time his eyes clung to the tightly sealed flask that nestled with careful caution in its supporting cradle. Within it a greenish gas glimmered weirdly in the overhead illumination of the laboratory. For the thousandth time his eyes strayed, almost unwillingly, yet with fearful fascination, to the motionless, strangely stiff little body of the white mouse that lay unhearing, unseeing, within the oxygen chamber.

Steve Dodd shook his head savagely. Damn it! If only the mouse were dead, it would be understandable, normal. The green gas he had toiled over would then have been but another poison gas, lethal enough in all conscience—a deadly weapon to add to the arsenal of already over-sufficiently equipped nations—but nothing that did not fit into the established properties of familiar gases.

But that mouse lying there, still, motionless, was terrifying. For a month, ever since he had tried a minute spray of the new gas on its outer skin, it had not moved. Its heart had stopped beating, the most delicate tests betrayed no sign of breathing, of the normal processes of metabolism that continue without pause in a living body.

Yet the mouse was not dead. Its blood, skillfully withdrawn in hypodermic specimens, remained unclotted and fresh and bright-red in appearance. The organs showed no evidences of degeneration; the bacterial decay and loathsome putrescence that begin almost immediately on death were conspicuously absent. And, worst of all, its eyes, bright and beady in life, were still bright and beady and unfilmed. They seemed to follow Dodd with mute and hopeless pathos, as if imploring him to remove the weird catalepsy that had clogged its limbs.

Steve Dodd shook his head impatiently, in unconscious answer to that mute appeal. He had tried his best to bring life back to those tiny limbs with every device that modern science and medicine held available. Baths of pure oxygen, intravenous injections of digitalis, strychnine and adrenalin, electrical massage and short-wave treatments. Everything that his friend, Dr. George Cunningham, sworn to secrecy, could suggest.

But the mouse lay in its cataleptic trance, unmoving, unstirring, shriveling daily, wasting away to a thing of skeleton bones and loose, wrinkling skin, queerly alive, yet soon to die irretrievably.

Steve shivered, though the night was warm, and his glance went back to that strange, semi-luminescent green gas in the specially leaded glass container. That was another property about it which made it even more of a menace. Its remarkable penetrating powers! Ordinary glass was like a sieve to it, so were wood and stone and most of the metals.

Its first production had almost sent him, Stephen Dodd, into the place of the mouse. It was only the accidental intervention of a lead screen used in conjunction with his X-ray work that saved him. So the glass he now used was leaded, and he wore a special suit and helmet of fabric heavily impregnated with lead salts when he worked with the gas.

STEPHEN DODD was a chemist, and a very good one. He was internationally known for his work on the rare gases, and his laboratory was generously endowed by the Lauterbach Foundation. Yet he was not quite thirty, and possessed of decided views on a good many matters only remotely connected with the science to which he had devoted his life. Deborah Gardner, daughter of the famous astronomer, Samuel Gardner, who headed the observatory in the same university town, could vouch for that. Perhaps that was why, she thought tenderly to herself, Steve was the darling he was.

He had started his researches with the idea of duplicating nebulium—that strange, unknown gas which is found in most nebulae. Bowen of Pasadena had proved in 1927 that the three mysterious bright lines in the nebular spectrum—whose wave lengths are 5007, 4959 and 3727 Angstroms respectively—are due to multi-ionized oxygen and nitrogen under peculiar nebular conditions. But no investigator had been able to reproduce the mysterious lines in earth laboratories.

Dodd had thrown himself into the work with characteristic enthusiasm. For a year he had toiled ceaselessly, immured night after night in his laboratory with complicated apparatus and machines capable of generating giant electrical charges. Finally, using a modification of a De Graaff electrostatic machine, he had been able to superinduce multiple ionizations on a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen—in other words, plain, everyday air.

But, with success at his very door, the thing itself eluded him. For the spectral lines were slightly displaced. Allowing for all possible velocity shifts, they were still seven Angstroms each to the left of the corresponding line in the nebular spectra. It was infuriating. He had discovered a new type gas, but it was not nebulium, the gas he had set out to discover. At least, it was not the nebulium in any of the nebulae known to date.

THEREFORE he had called on Samuel Gardner, his good friend, and prospective father-in-law, to assist him—though not even to him had he disclosed the terrible properties of the pseudo-nebulium he had evolved. The secret of its manufacture must die with him; the very fact of its existence must remain undisclosed, unless somewhere in the universe it existed naturally.

Thus it was that Gardner good-naturedly analyzed the spectra of nebula after nebula, thinking young Steve a little bit crazy, but to be humored nevertheless.

Steve received the reports with a queer mixture of disappointment at repeated failures and relief that he would not be compelled to disclose what he had discovered. For nowhere in the universe were the nebulium lines anything but normal; nowhere was there evidence of the existence of pseudo-nebulium with its seven Angstrom units shift to the left.

Steve lifted the receiver mechanically, heard himself calling the observatory. After a decent interval, Gardner's quizzical drawl came lazily over the wire.

"Hello, Steve!" he complained, "this, is my busy night. If you've got any more fool nebulae for me, you'll have to count me out. I——"

"Listen, Gardner," Dodd pleaded, "this is the last batch. If you can't locate what I'm after to-night, I won't bother you any more." He had determined to give his scientific sense of fair play this final opportunity. To-night, after Gardner's usual report, he would destroy the flask with its dreadful contents, kill the mouse with weapons that left no doubt as to its demise, and forget all about it. Dr. Cunningham was close-mouthed, and besides, he did not know more than it had been necessary to tell him.

It was characteristic of Dodd not to have sought personal aggrandizement from the discovery, or to think even momentarily of the fabulous sums the war departments of the various nations of the earth would have paid him for the formula. He had very positive ideas on the subject of the nations of the earth and all their works. Even now, the mad race of armaments was nearing its inevitable close. The earth resounded with the rumble of mobilizations and the thunderous roar of tanks and motorized artillery moving everywhere up to the frontiers. Ultimatums were in the air and dates set for the vast explosion.

"Well," Gardner chuckled, "this once; but mind you——"

"Here they are," Dodd interrupted hastily. He read off the list from the item in the Astrophysical Journal. They were mostly fifteenth or twentieth magnitude nebulae. When he came to G 113 he hesitated. The twenty-fifth magnitude was a bit faint for Gardner's apparatus. For a moment he was going to leave it out—it was such an unimportant speck of gas somewhere in the far remotenesses of the universe. The fate of the world trembled on his indecision. Then he read it aloud.

"Now listen here, my boy," the astronomer expostulated patiently. "I can't get that magnitude. You know that. I have only a thirty-inch spectrograph, not a two-hundred-inch."

"Oh, well," Dodd responded indifferently. "If you can't locate it, you can't. And remember, my promise holds good. This is positively the last batch. If their spectra do not disclose the one I'm after, I'm through, washed up!"

IT was some three hours later, after 1 a.m., while Steve was dozing in his chair, fatigued from work and jumbled emotions, that the persistent ringing of the phone awoke him. He stared around, bewildered a moment, getting his bearings. Everything was quiet and very peaceful. The noise of the neighboring city had dulled to a stealthy murmur, the laboratory enfolded him in its illuminated quiescence, the green gas glowed steadily in its leaded flask, and the mouse was still stretched out, gaunt and unmoving, though still alive, in the oxygen chamber.

He shook the black mop of his hair out of his eyes, picked up the receiver. It was Gardner, his drawl forgotten, his voice muffled and queerly excited.

"Hello, Steve! Just finished the spectroscopic analysis of that list. Here they are." He bit them off rapidly, concisely, one after the other. Angstrom units of the three nebulium lines monotonously identical, as always. Then a perceptible pause. "About G 113 now, Steve. Sure you gave me the right coordinates?"

"Sure," Dodd answered sleepily. "But just a moment, I'll check it." He flung open the Journal to the right page, ran his finger down the list, then read aloud. "Right ascension—1 hour, 9 minutes; declination—plus 52.8."

"Humph!" Samuel Gardner muttered. "That's exactly what you gave me before, but——"

"Couldn't locate it, eh? Don't bother then. The magnitude is evidently too low for your instruments."

"You're right, Steve. I couldn't locate it, but there's another nebula, close enough by to be its twin. Listen to this! Right ascension—1 hour, 8 minutes; declination—plus 51.7."

"That's funny," Dodd said puzzled. "Must be the same one, but it's the first time I've known the Peters Observatory people to be caught in an error."

"That's not the only error," Gardner pursued, still with that queer tinge of excitement in his voice. "The nebula I have is of the order of the sixteenth magnitude, not the twenty-fifth."

This time Dodd was thoroughly awake. "But that's impossible," he protested. "A difference of nine magnitudes! Some one must have been drunk over there. I've a good mind to call them up right now and congratulate them on their staff. By heavens, I am. So long!"

"But wait," Gardner shouted, "I haven't told you——"

It was too late. Dodd had hung up and was already getting long distance. He was angry. If there was anything he prided himself on, it was meticulous accuracy, and here was the famous Peters Observatory——

Meanwhile Gardner was jingling the hook frantically, trying to get him back. But the operator was imperturbable. "The line is still busy, sir," she repeated sweetly, albeit a bit wearily, until Gardner swore and hung up in disgust. "The young idiot!" he muttered, and stared again with frowning intentness at the spectograph that lay before him, with its three bright lines plainly showing. Then he shrugged his scholarly-stooped shoulders. "Plenty of time in the morning to let him know, I suppose."

How could he know that every minute, every second even, was infinitely precious; that the continued existence of all life on this planet depended on those three innocent-seeming bright lines!

"Norman Kittredge?" Steve flung finally into the phone. The lengthy wait for a connection had brought his inexplicable anger to the boiling point.

A sleepy voice came through faintly. "Yes. Who are you?"

"Stephen Dodd, of East Haven. You're the fellow doing the plates for the new star map?"

"Dodd? Dodd?" the faint voice sounded puzzled. "Oh yes, the chemist. Sure, what about it?"

"Well, let me tell you something," Steve said carefully. Inwardly he was surprised at the irritation he felt. "You must have been drunk when you reported the coordinates for that new nebula, G 113."

There was a pregnant silence. Then Kittredge said furiously. "Now listen here, Dodd! If this is a joke, it's a damn fool thing. I don't know you personally, and I don't want to——"

"It's no joke," Steve retorted heatedly. "Look at that plate again, and check it against the figures in the Astrophysical Journal. Being out a degree or so in declination and a mere minute in right ascension may be not so bad—from your point of view; but when an astronomer of the Peters Observatory is out nine magnitudes, I'm giving him the benefit of the doubt when I tell him he was drunk."

Kittredge's voice was suddenly icy, carefully precise. "I'm going to make you eat those words, Dodd. I'm a fool for doing this; but I'm getting out that plate right now, and by heavens——"

The receiver crashed down on a faraway table. Steve waited, his irritated anger subsiding. He even grinned at himself. Wait until Kittredge got on again, meek and full of apologies.

"Hello!" It was Kittredge. "You still there?"

"Sure," Steve chuckled. "What's the story? Mislaid the plate?"

"No, Dodd," the astronomer answered coldly. "I have it right in front of me, and the Journal. If I was drunk then, I'm still drunk. The figures couldn't be more right. Now let me tell you what I think of you, young man." And for fifteen minutes he told him, steadily, continuously, without stopping for breath. It was an expert performance, and when Steve finally hung up, he was red all around the ears, his temples were wet, and his finger nails had dug red arcs into the palms of his hands.

"Whew!" he said to himself, almost admiringly. "That chap must have driven mules in his time." Then his thoughts swung to his future father-in-law. "Damn!" he muttered. "He got me into a peck of trouble. Must have been his idea of a joke. I'll get him before I forget all the neat phrases Kittredge used." And up went the phone again.

There was real relief in Gardner's voice. "I've been trying to get you, Steve——"

"Sure, it was a great joke, wasn't it?" Dodd interrupted. "Kittredge thought so, too. Wait till I tell you what he called me——"

"Joke?" Gardner echoed, astonished. "What do you mean?"

"Don't pretend. Those figures you gave me. The Journal had the right ones."

"Oh!" Gardner said slowly. Then: "Steve, I was not joking. Mine were correct, too."

"You mean——" Steve started aghast.

"I mean that within the past month and a half the nebula G 113 has moved that distance over the face of the heavens."

"Great heavens, man!" Steve exploded. "Then it must be right within the solar system."

"Not quite. You didn't give me a chance to tell you some very important things. The spectral lines of G 113 are all shifted heavily to the violet. I've calculated a velocity of fifteen thousand miles per second in the line of sight—an extra-galactic velocity. That means it's now somewhere within a few trillion miles of our system, where no nebula has ever been known to be, and coming toward us with fearful speed. I'll need another observation, a month from now, to be able to plot its course definitely."

Steve forgot his anger. He was immensely interested. But after all, this was more up Gardner's alley than his own. He had forgotten all about the fact that he had not been given the report on G 113's spectral lines.

"There is another thing," the astronomer continued. "You didn't give me a chance to tell you. The Angstrom units for the three lines. Let me read them to you: 500; 4952; 3720."

It took Steve a perceptible second to grasp what he had heard. Then his heart spun like a pinwheel within his breast. He could hardly breathe. "You don't know what you're saying." His voice sounded strangled. "It isn't so—you're playing a joke—it's——"

"My boy," the older man answered seriously, "the one thing I never jest about is my work. This is my life work, the air I breathe. Thanks to you I've discovered the closest nebula in the universe to us; with a velocity that is almost unbelievable, and showing the spectral lines of new elements. But how did you know? About the new elements, I mean. You've been mighty secretive, Steve, and I've humored you. But now——"

DODD stared with horrified eyes at the little flask with the green gas, at the mouse that was alive, yet shriveling slowly from day to day, and groaned. His scientific integrity demanded now that he publish the results of his work, no matter what the final outcome.

"I want you to come over to my laboratory right now," Steve said rapidly. "Now! At once! And bring all the data on G 113 with you. It—it's important as hell!"

He could hear Gardner taking a deep breath at the other end. "All right, my boy, if you say so. Be over in half an hour."

It was a fifteen-minute run by motor, but it was almost two-thirty when the doorbell rang. That hour's wait was the longest Steve had ever been compelled to undergo. He paced up and down the laboratory with quick, jerky steps, eying mouse and gas with alternate stabs, He was in a furious turmoil. Scientific integrity, tremendous discoveries, nations arming, horribly deadly weapon, consequences to humanity—phrases that spun round and round until they were empty of all content, of all meaning.

He jerked like a mechanical toy to the door when the buzzer sounded, flung it open with an impatient gesture. "Good heavens, Gardner," he cried impatiently, "it's about time——"

"Don't bawl dad out," a fresh young voice greeted him. "It wasn't his fault. I dropped in at the observatory just as he was leaving, and insisted on coming along. It took a bit of time to get rid of my friends."

Steve stared. "Deborah! What are you doing out this time of the night?"

"Emulating my elderly parent and the man who thinks he's going to be my husband," she retorted. "There was a party over at Jean's, and you were here, so I went on my own."

She was slim and petite, and the laughter glinted always in her eyes. Steve felt the tired lines around his mouth relax at the sight of her. "All right," he yielded a bit ungraciously. "If you're here, you're here. Though I would have preferred——"

The tall, slightly stooped, quizzical figure of Samuel Gardner followed his daughter in. Under his arm he held a leather portfolio.

"I told her the same thing, Steve," he groaned. "But you ought to know by this time——"

"He does," Deborah retorted. Her eyes roamed alertly around the laboratory, came to a dead stop on the glass tank in which the mouse lay silently. "This early morning conversation have anything to do with that little dead animal?"

"Plenty," Steve said in quiet desperation. "And he's not dead. Let me see those plates, please, and your data."

Gardner opened his portfolio without a word, spread them on the table. Steve studied the spectral lines against the standard comparison plate, checked rapidly through the calculations in deathly silence. Deborah sensed from the strained attitudes of the men that she had inadvertently muddled into something important, and she was levelheaded enough to make herself as unobtrusive as possible.

Steve finally raised his head. "It checks," he said wearily. Gardner stared at him. There should have been exultation, the thrill of some startling new discovery in his voice; instead, there was something akin to despair.

"If you wish to tell us," he started very quietly——

"Of course. I need your advice. Listen!" And for half an hour they listened while Steve poured out the story; father and daughter, engrossed, not seeing even the slow-shading dawn light over the quiet street outside.

"So you see," he concluded finally, "the dilemma I'm in. It isn't a question of fame and glory with me, heaven knows. I've synthesized a new air, a multi-ionized mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, and it's what I've called pseudo-nebulium. And lo and behold! Along comes a nebula, composed of that same deadly atmosphere, the only one of its kind in the universe. Scientists will want to know about those three lines, a shade of ionization under that of true nebulium. I hold the secret. What shall I do?"

"I say destroy it," Deborah answered promptly. Her eyes were wide on that motionless mouse. "Civilization is at a low enough ebb as it is. The world is preparing for a new era of slaughter. Put this new weapon in the hands of unprincipled men, and they will destroy humanity. You yourself say only lead will resist its penetrating powers. There isn't enough of the metal in existence to protect all humanity. Think, Steve, of millions of men, women and children, lying in a coma like that poor beast, shriveling away slowly, while nothing can be done to save them. A living death, far worse than actual annihilation."

Steve's eyes were grim. "You're right, Deborah," he said slowly. He moved quickly toward the fatal flask.

"Just a moment," Gardner's voice rang out. Steve swung around in surprise. Deborah cried desperately: "Father, don't let your scientific ardor run away with you. Don't you see what this particular discovery means?"

"I see everything, only too well. But Steve mustn't destroy that flask of gas, or the mouse. They both are infinitely valuable."

"Why?"

"I did not tell you, Steve," the astronomer said heavily, "because the data is still too fragmentary for accuracy. But now, under the circumstances, I must. At the terrific speed G 113 is traveling, its path through space may be considered for its relatively short distance from us as a straight line. From the two observations we already have, it looks very much as if"—he paused and took a deep breath—"as if it might pass very close to the solar system. But," he added hastily, "I'd need another observation, at least a month from now, to trace its course with real accuracy."

Deborah said, "Oh," very faintly. Lines etched themselves around Steve's eyes. He nodded, as if certain inchoate fears had been confirmed for him. "By close you mean of course a direct hit on our system," he said evenly.

"I didn't say that," Gardner answered quickly.

"You didn't have to." Again there was a deathly silence in the laboratory. The quiet dawn filtered slowly through the window, but no one noticed it.

It was Deborah who finally broke the unbearable weight of their thoughts.

"But father," she protested, "isn't it true that the earth has passed more than once right through cometary tails? I remember reading that in 1910 we were literally enveloped by Halley's comet."

Gardner lifted his head hopefully. "That's true," he murmured excitedly. "I had forgotten."

"And cyanogen is definitely known to exist in the spectra of comets," she continued quickly. "You wouldn't want a more deadly gas than that. Yet no one in the world died, or suffered the least inconvenience. Now comets' tails are rare enough—I understand that they are thousands of times less dense than our atmosphere at sea level, but I've also read that the density of the average nebula is considerably less even than that. It runs as low as ten to the minus seventeenth power that of the sun, or about a millionth of the best vacuum we can produce on earth. Isn't that so, dad?"

Gardner jerked his head in quick affirmative. His eyes glowed proudly on his daughter. "Quite right, Deborah. While G 113 seems more compact than the average nebula, yet I doubt if it is much more dense than the tail of a comet."

"Then," she burst out triumphantly, "what is there to worry about?"

"I used," observed Steve with strained deliberation, "a single drop in the form of an unbelievably fine spray on that mouse. It diffused through a five-gallon tank against air resistance. That is a pretty good approximation of a vacuum."

The hope died in Gardner's eyes. He squared his stooped shoulders. "There is only one thing to do, my boy. Publish our results. Warn the world. Furnish qualified scientists with the gas in the hope that they may find a neutralizing agent in time. And pray that my first rough calculations are inaccurate; that the nebula will swing outside the solar system."

THE late afternoon papers carried the headlines.

"FAMOUS ASTRONOMER AND NOTED

CHEMIST WARN OF LETHAL NEBULA.

PREDICT DOOM OF WORLD

UNLESS ANTIDOTE FOUND.

SCIENTIFIC BODIES MEET

HURRIEDLY TO EXAMINE PROOFS."

The cables took up the tale, the radio crackled frantically through the ether, until, by the second day, not a nook or cranny of the civilized world but knew of the Cassandra-like prediction.

By evening Steve's laboratory was a beleaguered fortress. The street outside was black with reporters, clamoring to the heavens for interviews. Sirens screamed as motorcycles cleared the way through heaving humanity for worried scientists, sceptical scientists, and just frankly curious scientists in search of data. The pronouncements of such a combination as Gardner and Dodd were not to be treated too cavalierly.

It was long past midnight before the clamor had subsided and the house cleared of visitors and barricaded against further intrusion. Steve was hoarse and his eyes bloodshot from much explaining; Gardner's shoulders sagged even more than usual. Only Deborah seemed as fresh and neat as if she had not been up for two days and a night.

The mouse had been studied from every angle, the flask with its deadly contents examined with respectful attention, and the spectra and astronomical data pored over with immense interest. The last was something definite. There was no question about the position and unusual velocity or of the pseudo-nebulium in its composition.

Only one thing did Steve refuse, politely but firmly, to disclose—the method for manufacturing the pseudo-nebulium. Inquisitive glances thrust surreptitiously toward his apparatus, toward the De Graaff machine, but Steve was not worried. The synthesis was a matter of complicated and laborious steps, and not to be fathomed by mere cursory glances.

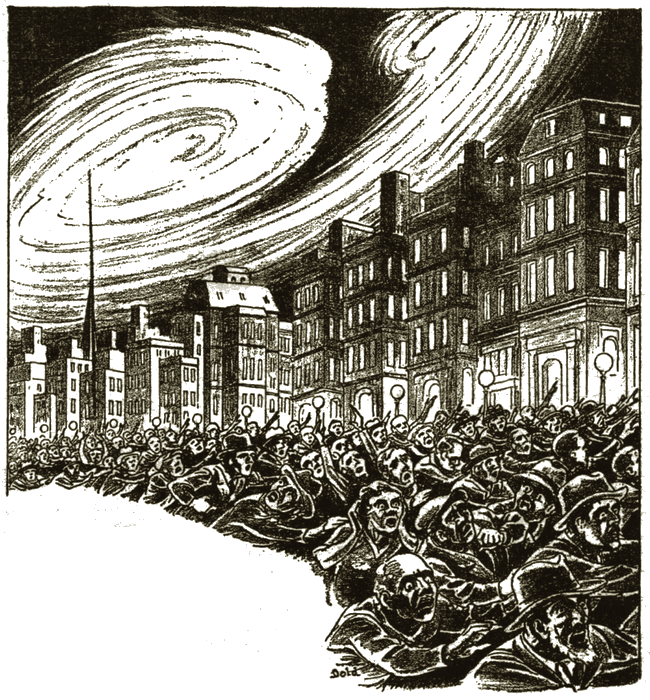

THE thing was a nine-day wonder. The newspapers played it up sensationally; the Sunday supplements spread themselves with faked, synthetic photographs of cities choking under the effects of thick-billowing nebular gases. The magazines printed long interviews with prominent scientists. Apprehension rustled over the earth. Men looked up to the heavens for almost the first time in their lives, seeking in vain the tiny blob of light that might mean their ultimate destruction. It was of course as yet invisible except to the lenses of powerful telescopes. Scientists, medical men, furnished with minute samples by Dodd, busied themselves with the effects of the gas on animals, while a ceaseless search for an antidote went on in a hundred laboratories. Thousands of mice and guinea pigs and rabbits were offered up to the cause.

And everywhere, the animals lapsed into their coma, and wasted away gradually, the living dead, oblivious of all attempts to bring them back to normal life. The scientists were of course interested in the new discoveries per se—the astronomers over the onrushing nebula with its speed that had been heretofore associated only with the great nebulae of the extra galactic universes; the physicists were agog over the multiple-ionized air; the biologists and medical men over the deadly effects on life forms.

But the man in the street was vitally interested in just one speculation, and justly so. Nothing else mattered to him. If the nebula were to sweep through the solar system, and plunge all humanity into the strange, wasting coma, what profit then the ardors of pure science?

For a few days then the world suffered a bad case of jitters. Even the preparations for war ceased. Then seeming sanity returned. The official announcements of international bodies of scientists were calculated to have a soothing effect. In the first place, the data on the onrushing nebula was as yet too scanty for a prediction of its course with anything like accuracy.

To this, Samuel Gardner promptly subscribed. He pointed out that he had avowed as much in his very first statement. Then, too, Deborah's initial arguments had been taken almost verbatim by the scientists of the world as their own. Granting even a direct hit, it was argued that, aside from certain possible aurora-like effects, the earth would not even know that the nebula was upon it. Concentrations were calculated, vacuums were learnedly discussed. Old files on Halley's comet and other earlier envelopments were resurrected and published to the world for its reassurance.

The excitement died. Men even began to laugh good-humoredly over the recent scare. Jokes sprang up like mushrooms, in which nebula and nervous scientists appeared in ridiculous lights. The reputations of Dodd and Gardner suffered irretrievably from their published warning. The rumor spread that they were notoriety seekers; that somehow they had intended to profit by throwing mankind into convulsive fear. Life flowed on an even keel again. The interrupted preparations for war renewed at an accelerated pace. The nebula was forgotten. Astronomers watched it carefully, of course, but that was their professional business.

But in a certain chancellery in Europe the matter was not permitted to drop so easily. The War Lord, resplendently military in Nile green, was in conference. Close-cropped heads bent over outspread maps.

The War Lord raised his head. There was an eager gleam in his feral eyes. "Good!" he jerked out in staccato fashion. He loved to clip his speech. It sounded so military. "The fatherland is ready. We will strike, there—and there—and there." His blunt finger passed rapidly from red-inked frontier to frontier. "Troops, tanks, planes, everything is prepared."

"Everything," echoed his councillors. The War Lord drummed rapidly with his fingers on the table. He frowned. "It will not be easy," he admitted, half to himself. "Our spies report the enemy is also prepared."

A swarthy man in the much-decorated uniform of a general said confidently: "It is not necessary to worry. Our troops are filled with patriotic ardor. They will be irresistible."

"Hmmm!" The leader seemed doubtful. He pressed a buzzer suddenly. An aide swung open the door, sprang to attention. "Show Bollman in."

A little man entered. His eyes were bright and birdlike, and his mien was humble in the presence of the dreaded War Lord.

The dictator fixed him with a cold, penetrating stare. He loved to see the scientist cringe before him. It inflated his ego; it soothed the involuntary feeling of inferiority he possessed in the presence of those who had brains.

"That gas the American discovered," he commented abruptly. "It works?" The little man bowed deeply. "It does. Even as the American, Dodd, has stated. One hundred monkeys, two thousand rabbits, two lions, a tiger and an elephant are in comas induced by one cubic centimeter of the gas which I sprayed into the sealed and leaded enclosure of the zoo. They dropped, highness, as if felled, and they have not moved since."

"And there is no cure?"

"None whatever. Our staffs have tried; all over the world the laboratories are busy, without result."

"And what use," pursued the War Lord, "could be made of this gas in war?"

For the first time the scientist permitted his head to lift. His voice held a confident ring. "A dozen bombs, filled with pseudo-nebulium, dropped from a single fast plane over the largest city in the world, would release enough gas to place every man, woman and child in the area into the coma. Hiding in the deepest cellars, behind the thickest walls, could not save them. Only lead is impenetrable to its influence, and lead chambers to house millions, are—well——" He smiled significantly.

THE dictator glanced sharply around the circle of his advisers. Suppressed excitement was in their eyes, excepting only those of the general. He was a firm believer in Massenmensch, in the massed attack of countless hordes of men backed up by heavy artillery. Gas and such were mere toys, fit only for impractical theorists.

There was a faint grin of triumph on the War Lord's face as he swung back to the respectful scientist. "Good!" he clipped. "Within ten days you are to have ready a sufficient supply of this gas to fill ten thousand bombs—leaden bombs." The fingers of his right hand ran rapidly over his left, as if he were ticking off the number. "London! Paris! New York!" Satisfaction creased his smug features. The world was already at his feet. He, that once had been the digger of ditches, was smarter than those who had sneered at him! He had brains enough to avail himself of even the nebulae in the heavens, while his enemies, with their snobbish superior culture——

The little scientist cringed. Alarm sprang into his bead-like eyes. His hands made helpless fluttering motions.

"B-but, highness," he stuttered.

The War Lord descended rapidly to earth. He frowned. "Well, Bollman, what is it?" he demanded ominously.

"We—we can't get that much of the gas," the scientist managed to gasp.

"Why not?"

"Because, highness, we do not know how to make it. We have tried, and tried, but it is so far impossible."

The face of the dictator suffused with red. A dangerous sign. He took a step forward. "The American has done it, has he not?" His tone was deadly.

The scientist went white. "Yes, highness," he breathed hard, "but he has not told how. And no one else in the world has duplicated his method. He gave samples to our laboratories, but there is only half a cubic centimeter left."

The War Lord seized the terrified little man, shook him until his teeth chattered. "Stupid ass!" he screamed. "What good are you? You can't find the secret, eh? An American, a pig of an American, is smarter than you are, is he? Go back to the laboratory, and make me that gas within ten days, do you hear?" He flung the scientist away from him, stood there in apoplectic fury.

Bollman fled to the door. "Yes, yes, highness," he choked. "Your will is law. It shall be done." And he was gone, stumbling in his eagerness to get away.

The dictator rubbed his hands, smiled. "There!" he bragged, sweeping his eyes arrogantly over the motionless figures of his councillors. "That is the way to do things."

There was a hasty murmur of approval. But the minister of propaganda, unofficially known as the "brains" of the War Lord, remarked dryly: "Science is a coy mistress. Not even for your highness does she disclose her secrets on mere command. The ten days will pass, and Bollman will feel the sharp edge of the ax on his neck, but you won't have the gas. There is another and a more practical way."

"What is that?" the dictator demanded uneasily. He hated the minister of propaganda, resented his calm superiority, but he needed him.

"Buy the process from the American. Offer him money. No American has ever refused money," he answered cynically. "It is their god!"

"You are right." The dictator clenched his fist, pounded the table. "That will be your job. Offer him a million, ten million! Kidnap him, if necessary. With that gas, gentlemen, we rule the world!"

Two weeks had passed since the first preliminary announcement. The tumult had died. The eyes of the world had swerved to the threatening situation in Europe. All pretense at concealment had been contemptuously cast aside. The nations were ready, eager, under the lash of skillful propaganda, to surge at each other's throats. Bollman was dead, executed secretly as a traitor to the fatherland. The ten-day grace period had expired, and the requisite process had not been forthcoming.

Then there were other matters to divert the attention of humanity. Important, all-absorbing matters. A beautiful woman had killed her lover in Paris. The scoundrel had expressed a desire to return to his deserted wife and three children. The trial was on. The jury craned and almost broke their necks to see the defendant's shapely, crossed legs. They grinned lewdly at the lawyer for the defense—a clever man—read certain very passionate letters with unctuous, sly meaning. The courtroom was wired for broadcasting so that every detail could be carried on the wings of modem inventive genius to the tiniest tot in the land.

In England it was Jubilee Year. The King and Queen, the Prince of Wales, and all the little princelings, showed themselves time and again to a never satiated nation. The tableaux were terrific, the crush almost as bad. The papers boasted of the number of loyal subjects who fainted or suffered severe injuries in the mighty throngs.

In Germany there was scandal. Some one had dared accuse the leader of having non-Aryan blood in his veins. More, he had documentary evidence to prove his thesis. The nation rocked to its foundations. But the matter was soon satisfactorily explained. It had been all a mistake. The documents related to a man who had despicably assumed the leader's name at birth, in expectation of this very vile attempt to besmirch the leader's purity. He had been protectively removed, so had the accuser, so had the documents. Everything was lovely again.

Russia had no scandals. They were not permitted. But they were in the throes of renaming every city, town and village in the country. This evoked violent discussions, accompanied by the interminable drinking of tea. Some doddering oldsters insisted that Lenin should be similarly honored. At length a compromise was reached. A tiny village of some sixty souls, including pigs, cows and chickens, was formally christened Leningrad, and every one was happy.

But in the United States there was the Irish Sweepstakes. By a stroke of genius the hospital authorities had tied it up with the chain-letter craze. Mail a ticket to the top of ten names on the list, cross him off and add your own at the bottom. Eventually, with the patient aid of the mail carriers, over a thousand tickets in the great lottery would return to you, increasing your chances of success just that much. The lottery officials chuckled and took in millions of dollars. Every one was in it, from bootblacks to captains of finance. There was no other topic of conversation. A president was elected almost without an engrossed nation, knowing that there had been an election. Not half of the people could tell you the new incumbent's name.

NATURALLY, a nebula somewhere in space, that could not even be seen, about which some fool prediction had been made, was pushed out of the way. It was as dead as last year's best seller.

There was one place, however, where it was still a matter of grave importance, even in the face of these world-shaking events. That was the laboratory of Stephen Dodd. Gardner had obtained a new set of observations. G 113 was the order of the tenth magnitude now and shifting its coordinates rapidly.

"I am afraid there is not much chance of its missing us," he told Deborah and Steve gravely. "It is still an approximation, but——"

He stopped. There was nothing more for him to say. Steve cast Deborah a quick glance. "When do you think the collision will take place?"

"If it does, it would be in about six weeks from now."

Deborah cried out: "Dad! Steve!"

Six weeks between them and possible annihilation. Six short weeks for love and laughter and the warmth of human relations!

Steve clenched his fists desperately. "The fools!" he groaned. "Six weeks between them and death, and they won't believe." He flung open the window. "Look at them now; going about their silly tasks as if all eternity were ahead of them."

The street was thick with traffic. Autos moved in a solid queue; pedestrians dotted the sidewalks, intent and hurrying; the human ant heap buzzed and swarmed.

"Don't blame them," Deborah said quietly. "It is not their fault. They're been told by the scientific societies that there is no cause for alarm; that you and dad are either mistaken or charlatans."

Steve swung away, paced the laboratory with hurried steps. "If only the entire world threw everything else aside, devoted all the resources of civilization to the problem, a safeguard, an antidote might be found in time, and manufactured in sufficient quantities to save at least a sizable portion of humanity. Even lead chambers——"

"Would be of small value," Gardner pointed out. "There is not that much lead in the world. And furthermore, one could not live indefinitely in lead. Lord knows how long earth's atmosphere will be permeated with the deadly gas!"

Steve stopped short in his pacings. His eyes glittered with feverish intensity. "At least," he cried, "we can make the attempt. We are men, not animals to await extinction with helpless fatalism."

"What would you do?" Deborah asked.

"This! Get together a choice group of scientists, those whom we can convince. Work night and day on an antidote, build ourselves a lead-lined house, capable of being hermetically sealed, equipped with oxygenation apparatus, stored with food. Perhaps——"

"That will cost money, lots of it," the practical astronomer interposed. "I have none; you've used up all your grant from the Lauterbach Foundation. In the face of the unfavorable publicity we've received, no man of wealth would dream of financing us."

Despair settled on Steve's face. "You're right, Gardner," he acknowledged heavily. They looked at each other, the two men and the girl, feeling the future of mankind to rest on their precarious shoulders—a mankind that heeded them not and had already forgotten their very existence.

The doorbell rang—sharp, impatient, ominous. Deborah moved quickly, opened the door. A dapper, dark-faced man stood a moment in the doorway, then entered with a courteous gesture. His clothes were expensive and of foreign cut; his face was saturnine and slightly alien. His quick, dark eyes flitted rapidly around the room. His black sleek hair was heavy with pomade and curled slightly up at the corners of his temples.

"Like Mephistopheles," Deborah thought.

"Pardon me, my dear lady," he bowed and smiled. His English was impeccable, yet tinged with alien intonations. "I wish to have the honor to address myself to Mr. Stephen Dodd."

Steve stepped forward. "I am he. What do you want?"

"Ah!" The man's eyes rested with some astonishment on his youthful, powerfully built figure. These Americans were a strange breed. This young man should be an army officer, not wasting his time in potterings around laboratories. He shrugged his shoulders slightly. He had a mission to perform.

"It is an honor, sir, to meet you." He smiled expansively. "My business, is unfortunately, of a delicate nature, and requires—you understand——"

"We have something to take care of in the lab," Deborah said sweetly. "Come, dad!" She linked her arm in his, steered him out. The man's eyes followed her admiringly. Ah, the American women were pretty! Then they came back, focused sharply on Steve.

"This, sir, is my business. I need not inquire if you are in need of money. All Americans are, are they not?" And he laughed heartily.

Steve felt a vague dislike for the man.

But his ears prickled. Money, had he said? And how he needed money right now!

"I could use some," he admitted cautiously.

"Good!" the man said with an air of satisfaction. "Sir, I am authorized to offer you the sum of one million dollars in cash, immediately."

For a moment the room swayed around Steve. One million dollars! Was the man mad or just a practical joker? With an amount like that, he could——

Steve snapped out of it. "What's the catch?" he demanded.

"Catch?" His visitor seemed puzzled, then he smiled. "Ah, I know. One of your very charming Americanisms. There is no catch—as you call it." He inserted his hand in his inner coat pocket, took out an embossed leather wallet, spread it open, and delicately removed a check. He smoothed it out before Steve's astonished eyes. It was for one million dollars, payable to Stephen Dodd, Esq., drawn on the City National Bank of East Haven, and certified. Steve recognized the certification as genuine. His own very modest account was with the same institution.

IN a daze he heard the smooth voice of the tempter. "It is yours, my dear sir, in return for one very small thing."

With an effort Steve controlled himself. "And that is——"

"The exclusive rights to the secret of the manufacture of pseudo-nebulium. That is all. Nothing else. Not even your services will be required. Quite a satisfactory arrangement, is it not?"

Steve's head cleared. He was instantly wary. "I don't know," he said coldly. "It depends. Whom do you represent?"

The man seemed surprised. "Does it matter? One million dollars is exactly the same amount whoever offers it to you."

"Perhaps," Steve fenced. "But I don't sell unless I know the buyer."

"Even if the amount were raised to two millions?" the emissary asked insinuatingly.

"Not even for ten millions."

The agent of the minister of propaganda felt the blood rush to his head. What manner of fool was this American? It was maddening. He had received positive instructions not to disclose his superiors, but one look at this most surprising imbecile convinced him that he was up against an insurmountable obstacle. Terror seeped through him. He knew what awaited him if he returned with his mission unfulfilled.

He took a desperate breath, clicked his heels smartly. "It is for his highness," he saluted as he spoke the dread name, "the War Lord!" He dropped his hand, opened his wallet again, and took out another check. The fabulous figure danced before Steve's eyes. It was for ten million dollars!

Ten million dollars! His life, the life of Deborah, of this smooth-smiling tempter who stood before him, of the entire world, nestled in the crinkling folds of that oblong stretch of paper. A vision swam before him of the magic ink changing, by a sort of fierce alchemy, into a swarm of laboratories, into a thousand doctors, chemists, biologists, working night and day, seeking, searching, for the antidote that must exist, somewhere, locked in the secret recesses of plants, of trees, of drugs, of strange combinations of chemicals. Six weeks! What a pitifully short time!

Then the vision faded. It was a dream, an illusion. The War Lord desired his process. It was to be an outright, exclusive sale. The corners of his mouth tightened. He knew what that meant. He knew the particular brand of idealism his highness affected.

Pseudo-nebulium was a frightful weapon of destruction, was it not? In the hands of the War Lord——

What did it matter which way the world went to destruction—the hellish way of bombs dropping from fast planes, or the way of impersonal forces? His shoulders straightened. His face was grim and hard. If the world must necessarily become a mausoleum for the human race, let it be without the intervention of man's bloody hands.

The agent read the look rightly. It was a refusal. But he misunderstood the cause. He said hastily: "Ten million is the maximum I am authorized to offer."

Steve fought to steady his voice. "A million would have been enough," he said in cold anger.

The emissary felt perspiration bead his dark smooth forehead. Had he overbid in his anxiety? Had he——

Steve stepped close to him, fists clenched, lips writhing contemptuously. "Go back," he lashed out, "to your master. Tell him the process is not for sale. I know to what despicable use he intends putting it. Tell him I'd rather see all humanity extinct under the nebula than give him even the fleeting satisfaction of strutting as the ruthless conqueror." The young scientist laughed harshly. "Tell him in six weeks time we'll all be dead because he and all the other fools like him refuse to believe our warnings. Now get out!"

The man moved back a step from this insane American. He was desperate. Already he felt the ax on his slender neck. "I'll raise it to twelve million," he cried.

Steve clenched his fists. "Get out!" he repeated.

The agent stared at those capable hands in fright, and backed hastily out through the door. It slammed behind him with a definitive crash. For an instant he stood rooted to the ground, heedless of curious passers-by, staring at the obdurate door that meant his very life. Then he smiled faintly. It was not a pleasant smile. He knew certain compatriots of his in this town, men who would do the bidding of the War Lord. He hailed a taxi and drove rapidly away.

Inside the laboratory, Steve was writing furiously at his desk. He barely raised his head at the entrance of Deborah and her father. Six weeks! Six weeks! The words patterned themselves over and over in his brain as he wrote. The letters piled high before him—five, ten, twenty. Desperate appeals to certain picked scientists, scattered over the world, with whom he was personally acquainted. The letters bristled with arguments and mathematical computations of the deadly penetrative power of pseudo-nebulium, and invited them to come posthaste with their families to East Haven, together with all the cash at their disposal.

And high overhead, still unseen to the naked eye, a vast cloud of tenuous gas, millions of miles in diameter, was rushing with terrific speed through the cold reaches of interstellar space; a colossus, intent on its victim—a certain small red sun and its attendant train of nine circling planets.

THREE weeks later, a handful of people gathered in the living room of Stephen Dodd's house. Only a few had responded to his appeal. There were Samuel Gardner and Deborah of course. Also Dr. George Cunningham, Steve's friend, a round, jolly medico with a bald, pink expanse of forehead. Dr. William Clay, tall and pale and thin-lipped, an authority on glandular secretions and hormones, with his stout, comfortable wife and two little children, a boy and a girl. Henry Claiborne, the biologist, known the world over for his work on the genes of inheritance and the mechanism of the cell.

His weak, near-sighted eyes were eternally adoring the platinum blonde, sinuously curved ex-chorus girl whom he had somehow married. But her calculating gaze, sheathed by long, mascaraed lashes, appraised the men in the little gathering with interest, and lingered longest on the clean-limbed body of their host. As for the women, she dismissed them with casual contempt, except for Deborah. Their glances measured each other, and Deborah turned away with a queer feeling of dislike for the exotic, empty-headed creature.

Then there was Herr Josef Kuntz, a meek little German scholar, manifestly under the thumb of his massive, mannish wife. They had four girls, with scrubbed, shining cheeks and thick flaxen hair neatly braided in pigtails down their backs. It was hard to believe that Herr Kuntz was a chemist whose researches on colloids were classic examples of the scientific method. Monsieur Armand Hanteaux, with his huge black beard and expressive shoulders, was obviously French. It was not so obvious that he had penetrated further into the innermost vitals of the atom than almost any other man then living. He was there alone. Marriage, he proclaimed with Gallic freedom, was an institution for fools. He, Armand Hanteaux, let other men wear the fetters, while he—and his bold black eyes rested admiringly on the seductive lines of Clara Claiborne.

There was only one other in the little company—Oscar Folch, a subject of the War Lord. Steve had heard of him vaguely as a chemical engineer in charge of munitions plants. The fifty invitations that had finally gone out had not included his name. But Folch had shown up with a black hand bag swinging from bony fingers—dark, reticent, a man of few words. He had explained shortly that he had heard of Steve's plan, that he approved, and had come uninvited. Steve had welcomed him politely. He did not connect the appearance of Folch with the visit of the emissary from the minister of propaganda several weeks before.

Of the fifty, no others had come. Most had not taken the trouble to answer; some had written curt, abrupt refusals, imitating that Dodd was a bit cracked, if not a charlatan. A few had been more courteous in their regrets.

Steve made them a little speech of welcome. They were, he told them, the sole hope of mankind. Their resources were limited, and the time perilously short. They were leaders in their respective fields, and perhaps, by unremitting cooperative labor, they might evolve an antidote, a defense against the onrushing nebula before it seeped into earth's atmosphere.

"And if we don't?" queried Dr. Clay dryly.

Steve shrugged his shoulders slightly. "Sauve qui peut," he quoted. "We must try to save ourselves then. At least humanity shall not become completely extinct. With ourselves as a nucleus, men and women and children, we'd have to rebuild a world."

Clay's little girl let out a frightened wail. The prospect did not seem to please her very much. Deborah flushed and held her level eyes steady. Mrs. Kuntz sniffed audibly. Her child-bearing days were over.

Dr. Cunningham groaned comically. "A swell future you're mapping out for us poor bachelors, Steve." But Hanteaux's eyes were hot and admiring on Clara Claiborne. She bridled and shot him a long seductive glance. Her husband glowered at her furiously. It was evidently not the first time she had given him cause for jealousy.

"We save ourselves then," Oscar Folch said thinly. "How?"

It was the first time he had spoken at the meeting, and his voice jarred unpleasantly on Steve. Was there more than a hint of mockery, perhaps, in that thin, creaking voice?

But nothing of that appeared in Steve's tones as he answered. "We'll lead-sheathe this house and seal it against the penetrating gas. We'll install air-conditioning apparatus, and store food supplies sufficient for a year. That will be your job, Folch, and yours, Hanteaux."

"I would prefer working with the pseudo-nebulium," Folch announced calmly.

The blood rushed to Steve's face. He clenched his hands angrily. Gardner saw the explosion coming, and hastened to intervene. "There is one thing we must all understand," he told Folch gravely. "The project can only be a success if there is the strictest discipline. Mr. Dodd is the leader. I cheerfully submit to his orders and so must every one else. It is the only way."

Folch glanced inscrutably around the circle and saw nods of approval everywhere. "Very well, then," he said suddenly, and relapsed into his former silence.

Hanteaux rumbled in his beard. "A praiseworthy idea, Monsieur Dodd.

That is, if the nebular gas does not make the earth's atmosphere permanently poisonous. But what you ask for is expensive. Have we perchance a Croesus in our midst?"

Steve frowned anxiously. He stared at the taut, intent faces about him. "I've figured the costs," he said slowly. "It will take about a hundred thousand dollars. I have exactly seventy-four hundred dollars, including all spare equipment that I've already sold. Gardner, how much have you?"

The astronomer blinked. "Nine thousand, which includes three months' salary I managed to persuade the board to advance."

"And you, Dr. Cunningham?"

The rotund doctor grinned. "Besides my stethoscope, and an inestimable education which cost my late venerated father some twenty thousand, I have exactly six hundred and twenty dollars and thirty-four cents."

Herr Kuntz looked bewildered. "I have maybe a few dollars yet. It cost all my savings to bring my family here." Hanteaux rumbled something about several thousand; Claiborne was the wealthiest, with ten thousand; Dr. Clay had a little less. Steve figured quickly. So far the total was about forty thousand, and there was only Folch to hear from. He turned inquiringly to the engineer from the realm of the War Lord.

Folch shook his head sardonically. "I have," he bowed precisely, "my traveling bag—nothing else."

A tense silence held them. Even Clara Claiborne felt the weight of the situation and stopped her ogling. Then Steve's jaw snapped tight. "That means the 'safety first' idea is out. We'll use every cent of it on the finding of an antidote. Time is short, gentlemen. We'll get to work at once."

Not for a moment did the idea enter his head that, with the elimination of those without funds, notably Herr Kuntz, his wife and four scrubbed children, Dr. George Cunningham, and the uninvited Oscar Folch, there would be sufficient funds to build a smaller retreat for the moneyed people. Deborah felt the thought flash through her mind, and dismissed it with a shudder. She was more proud of Steve than ever before. They would live or die together, all of them. Those poor little girls with their shining faces and serious, pigtailed expressions! But she saw the sudden, hard, calculating look on Clara's face as her blue eyes flitted over the moneyless ones. The feline beauty turned to her adoring husband. "Darling!" she gushed, "I don't see why——

"That's enough, Mrs. Claiborne," Deborah flared quickly, eyes sparkling with anger.

"But——" Clara started.

"You heard what Mr. Dodd said," Deborah repeated firmly. "His plan is final."

Henry Claiborne stared bewilderedly from his wife to Deborah, and back again. "I don't understand——" he protested.

But his wife did. She shot a look of unutterable hatred at her antagonist, bit her lip until the marks showed white against the carmine of her lipstick, then smiled sweetly at the nearsighted, blinking biologist.

"It is really nothing, Henry, darling," she cooed.

THEY started at once. Not an instant could be lost. There were only three weeks in which to discover the antidote. Steve divided the work with swift precision. He took sole charge of the manufacture of the pseudo-nebulium to be used in the experiments. A vague, uneasy feeling made him more secretive about the process than ever before. Not even to Gardner, his father-in-law-to-be, did he disclose it. He shut himself up in the special laboratory, and permitted no one to enter its precincts. Several times he caught Folch in close proximity to the door with its intricate lock, but always he had a sufficiently plausible excuse for his presence.

The two doctors, Clay and Cunningham, as well as the biologist, Claiborne, worked cooperatively and with feverish intensity on the effects of the gas on a hundred newly martyred mice. In the laboratory, Claiborne, his uxoriousness forgotten, was a totally different man. Quick, accurate in his movements, precise.

Herr Josef Kuntz also sloughed his meekness. Chemicals flowed under his expert fingers in unending combinations, each carefully ticketed, and immediately forwarded to the biologic lab for injection into the quiet, unmoving mice. The original mouse martyr was nothing but skin and bones. Claiborne was positive that the spark of life still flickered somewhere in that emaciated frame; Clay was just as positive it had vanished completely.

Oscar Folch, in his engineering capacity, built apparatus as it was required by the others. There was no question that he knew his job thoroughly. He rarely spoke, but his eyes darted ceaselessly and inscrutably over every nook and cranny of the three-story building in which they were housed. Without quite knowing why he did it, Steve, after meeting his dark, mocking gaze, invariably turned back to his manufacturing chamber to make sure that the door was locked.

Gardner remained at the observatory for constant vigil at the telescope, coming to Dodd's house only to sleep and report. There was no question about it now. G 113, the runaway nebula, had grown to the order of the fifth magnitude, and was faintly visible to the naked eye on moonless nights as a patch of wan light near Sagittarius. It was only some twenty billion miles away now. At the tremendous speed with which it was traveling—15,000 miles per second—it would take only another fifteen days to engulf the solar system.

The observations were sufficiently extensive by this time for accuracy. There would be a direct hit. Gardner's figures agreed with those of other astronomers. The observatories of the world were excited over the approaching nebula. But none of them felt any untoward alarm. They announced comfortably that aside from a certain luminescence in the heavens, there would be no other effects. Their calculations, again tallying with Gardner's, proved it to be more tenuous than a comet's tail. What was there to worry about, then? The gray-haired astronomer came in for a good deal of joshing from his associates; the newspapers made merry over the immured scientists and their families in Dodd's house. "Noah's Ark," it was dubbed, and the name stuck.

Yet even so, the onrushing nebula rated headlines in the papers. After all, it was the first to penetrate the solar system. Scientists prepared delicate apparatus to examine and probe the innermost secrets of the strange visitant. It would have received far more attention had not the War Lord, tired of waiting, commenced his long-heralded attack. Bombing planes smashed huge cities, sent long streams of refugees—those who survived—into panic-stricken flight. Heavy artillery thundered, great tanks lumbered like monstrous caterpillars over shell-torn landscapes, poison gas enveloped hundreds of miles in a dense, searing pall. Millions of men, grotesque in gas masks, hurled like gray ghosts through the poisoned atmosphere, locked in furious combat. Nation after nation tumbled into the maelstrom. All Europe, all Asia, was aflame with battle and sudden death. Only America as yet was aloof from the turmoil.

Naturally, the nebula, now grown to a silver disk of light, was unimportant. Steve groaned and harried his little group to even more furious efforts. Only a week remained, and nothing—absolutely nothing had been accomplished. Hanteaux forgot to stare boldly and lecherously at the quivering charms of Clara Claiborne. His great beard almost immersed itself in the whirring apparatus he had evolved and Folch had constructed. He was attempting an electrical approach to pseudo-nebulium, to see whether it could not be deionized into normal, innocuous air by tremendous surges of current. But the strange gas was unusually stable, and its multiple ionization resisted all his efforts. The women, under Deborah's leadership, purchased supplies, prepared meals, ran the house, assisted their menfolk in the laboratories.

Funds were running low. Equipment was expensive and ate rapidly into their modest account. Steve tried desperately to interest certain men of wealth, offering them dazzling visions of being the possible saviors of humanity, of saving themselves in any event. He was laughed at, and dismissed with mocking words. He was a charlatan—the papers had said so. He and his associates at Noah's Ark were crazy predicters of the end of the world—and besides, there were immense profits to be had in the sale of munitions and supplies to feed the holocaust on the other side.

STEVE returned wearily from a last fruitless appeal. It was night. The nebula was plainly visible now, a shimmering flash of light across the horizon. Four more days! He shuddered. He thought of Deborah, with her steady, tender eyes, and felt sick all over. There had not been any time for love making. And in a few days——

There were the others too; the rest of mankind. He stared with strange intensity after the people as they hurried about their petty affairs, as though he had never seen them before. He tried to vision them all, moveless, shriveling slowly, as the mice had done—were still doing. Then his mood changed. A fierce anger gnawed at his vitals. Half the world was engaged in insane slaughter, for no other purpose but to feed megalomaniac ambitions. They laughed at him and his warnings, refused the very small sums, the cooperation that might have saved them all from a dreadful fate.

They were not worth saving, he cried aloud. A man stopped a moment, looked at him curiously. Steve moved on hurriedly. He must be in a pretty bad fix, he thought, if he began talking to himself.

At the laboratory, they huddled around him. He did not have to speak. They saw from his face that he had met with no success. It had been his last hope. To-morrow it would be too late.

Without a word Deborah came to him and put her slender hand in his. "Never mind," she whispered. "You'll manage it somehow."

He squeezed her cool fingers, shook his head soberly. "I think I'm on the right track," he said. "It's only a guess, of course. But there are certain very rare and expensive chemicals that I need. We haven't money enough to buy them. Money!" He laughed bitterly. "Trash that will be less than meaningless in four days."

Dr. Cunningham said quietly. "What do you need?"

"Three grams of radium sulphate, half a kilo of metallic scandium, a tank of krypton, and two kilos of lutecium chloride. Almost fabulous stuff. Kungesser's the only place in this country that carries a supply. They quoted me, after much scurrying, eighty-five thousand dollars for the lot. Might as well ask for the moon."

Dr. Cunningham said even more quietly. "You'll have it by to-morrow morning." For once in his life the jolly grin was gone from his rotund countenance.

A babble rose hurriedly. Gardner expostulated. "But how in Heaven's name, George——"

Cunningham cut him short. "Never mind. I said to-morrow morning." Without another word he left the room. They heard the front door slam, and he was gone.

Steve shrugged his shoulders. "Poor George! The strain's been too much. In any event, to-morrow's too late. The reactions I've calculated will take four full days, and midnight is the deadline. After that each hour, each second even, will be just about that much after the nebula envelops us."

Folch smiled for the first time. It was not a pleasant smile. "I think," he remarked thinly, "I can provide you with what you need, with money enough for all the experimenting in the world, within half an hour."

They stared at him. Steve's head snapped up. "What's that?" he demanded.

Folch repeated carefully what he had said. "I can offer you up to ten million," he stated calmly.

There was a sensation. Memory struggled in the back of Steve's mind. That was the exact sum with which the agent of the War Lord had tempted him.

Anger flared in him, burned down. He eyed the spy grimly. "And all you want in return is the method for manufacturing pseudo-nebulium, isn't it?"

For the first time Folch betrayed emotion. He fell back, caught off balance. "Why, how did you know?"

Steve laughed harshly. "Your fellow spy offered me the same amount weeks ago. And I turned him down.

Now go back and tell your master——"

But Folch had recovered himself. "I don't know what you're talking about, Dodd," he stated evenly. "I received word from a friend of mine, a millionaire in my country, only a little while ago. He is willing to give me that sum, but naturally he drives a bargain. He wishes to manufacture the gas for certain reasons——"

"Your millionaire is the War Lord," Steve broke in furiously, "and I know his reasons quite well. His dreams of conquest aren't progressing as smoothly as he had thought. The use of pseudo-nebulium in sufficient quantities would make him absolute master of the world. But——"

Folch's eyes glinted dangerously. "You are a pack of fools," he flung out to the others, ignoring Steve. "According to Dodd you'll be dead, or what amounts to death, in four days. Nothing can save you now. What does it matter if my country gets the secret of pseudo-nebulium? What difference would it make to you, to any one else? But the money that will be paid you would buy those supplies Dodd thinks necessary to his antidote. That means you will all be saved, while the rest of the world, including my countrymen, would have passed under the influence of the gas."

He was sneering covertly now, making mock of their foolishness. Yet it was a specious argument, carefully calculated to win them over to his side.

Mrs. Kuntz nodded her masculine head vigorously. "Do you hear, Josef? It makes sense. Say something!"

Poor Kuntz said timidly, doubtfully, "Perhaps then he. is right. Maybe it would be best——"

Clara Claiborne moved between her husband and Hanteaux. Her perfume intoxicated the Frenchman, enwrapped her husband. Her lips were parted, and panic stared out of her baby eyes. It had taken her a long time to discover just what it was these others feared so greatly, and only that morning it had really penetrated. Since then she had been hysterical. She wanted to live with all the ardor of her selfish nature.

"Give him your silly old secret," she panted to Steve. "I don't want to die." Henry Claiborne turned his nearsighted eyes on his wife with a strange, puzzling look. He said nothing. But Hanteaux bowed gallantly to her. "It is already done, chérie," he murmured.

Steve clenched his hands. "The answer is no!" he snapped. "Not even for a minute would I turn the process over to your War Lord."

Dr. Clay compressed his thin lips. "You forget, my dear Dodd," he said precisely, "that we also have something to say concerning our lives. We have invested our energies and our money, and we may be considered as partners. I suggested we take a vote."

Steve took a step forward. "Why, you——" he started in a choked voice.

The atmosphere fairly crackled with electricity. Folch waited, a saturnine look on his dark face. Matters were playing into his hands. Then Gardner moved into the breach. It was high time.

"Just a moment, Steve," he interrupted. He faced the others. "You of course realize that Folch and his master do not believe that the nebular gas will have any effect on humanity?"

"Naturally not," Folch answered contemptuously, and stopped short, realizing he had said too much.

"Exactly," Gardner pursued evenly. "If they are right, then you have placed a weapon in the War Lord's hands that will make slaves of the rest of the world. Oscar Folch was sent here deliberately as a spy, to steal the secret, to buy it, if possible."

"But we believe," Dr. Clay clipped out. "I've worked too long with pseudo-nebulium to doubt its effects even in concentrations approaching a vacuum. Folch was correct, even though he thought he was mocking us. They'll die from the effects of the gas, whether they have possession of the process or not. While we at least could use the money to perfect the antidote on which Dodd bases his hopes. What's wrong with that?"

ONCE more Steve was himself. He could see how plausible the argument was to the others. "This!" he told Clay. "The formula I evolved is purely theoretical at present. From certain physical data Hanteaux has furnished me, from the knowledge I have of the properties of the rare elements I mentioned, it seems to me that they, in certain combinations, would remove the ionization from the gas and bring it to the condition of ordinary air. Claiborne's experiments have shown definitely that the peculiar catalepsy it induces is caused by the permanent fixation of the molecules within the blood stream. Once pseudo-nebulium turns to un-ionized air, it will bubble out, and the effect dissipated. But mind you, this is all theory. It may work; it may not. If it doesn't, nothing will matter; sale of the secret, or no sale. But if it does——"

"Then certainly we are saved," Hanteaux rumbled.

"Yes," Steve flashed back. "But you forget that unwittingly I told Folch, as well as the rest of you, what materials I required. The War Lord has scientists also, and with more resources than we have at their disposal. They will duplicate our work, make the antidote in enormous quantities, inject it into their people. The rest of the world will succumb; only the subjects of the War Lord will remain."

"And ourselves," Clay amended.

"How long could we survive against his hordes?" Steve flung at him. "Unless we bowed our necks and became the meanest of his slaves."

There was silence at that. Only Clara whimpered: "I want to live! I want to live!" Her husband quietly edged away from her, his forehead puckered with struggling thoughts. The others sensed the dilemma, thrashed it out in their own minds. Folch, glancing keenly from one to the other, saw that he had been beaten. He moved stealthily toward the door. But he could not resist a last attempt. "The offer will hold good," he announced, "for exactly three hours more. Until midnight. After that——"

Deborah cried out suddenly. "But he knows the formula for the antidote already, Steve."

A snarl of triumph writhed over the spy's dark features. "Fools! Of course I do. Go on with your silly Noah's Ark. I'll have both gas and antidote within a day. Good-by!"

He swung around and darted through the door. But already Steve had left his feet in a long slashing tackle. His outstretched hands caught at Folch's legs. The power of his driving body knocked the spy off balance, sent him crashing to the ground. Within seconds Steve had dragged the stunned, half-unconscious man within the house, and locked the door. Fortunately it was night, and no one had seen the struggle from the street.

Within seconds more Folch was trussed up and carried bodily to a room in the upper story, where he was left bound and helpless, a prisoner.

"That's that," Steve said grimly. "If humanity becomes extinct, at least the War Lord and his legions will not be left to inherit the earth. And now let's get back to our work. Perhaps we can find some other method of deionizing the gas."

Despair was on every face. It took an effort of will to return. Hope itself was hopeless. No one thought of Dr. Cunningham's wild promise.

It was dawn again. Lights had burned steadily in the house. They were working day and night now. Sleep was a matter of snatches. Steve, hollow-eyed, gaunt, groaned as he gulped the hot black coffee that Deborah had brought him. "You're killing yourself," she said anxiously. "You must get some sleep."

He laughed mirthlessly. "Look at those mice," he said. "We'll all sleep a long time soon enough."

"On the track of anything yet?"

"Not a thing," he answered wearily. "The other formula had at least theoretic possibilities. Now I'm just going blind. Hello, what's that?"

Downstairs there was a commotion, a babble of voices. Then hasty steps, clearing the stairs two at a time. Dr. Cunningham flung into the room, panting, his rosy cheeks white with exertion. Under his pudgy arms were bottles. Behind him stout Mrs. Clay staggered under the weight of a metal pressure tank.

"Good Lord, George!" Steve cried. "What the devil have you got there?" Cunningham deposited his bundles carefully on the table. One was a leaden tube. Then he straightened, gulped twice before he could catch his breath.

"Let's see now," he glowed in triumph. "The lead tube contains radium sulphate; over there is metallic scandium; here is lutecium chloride; and that tank Mrs. Clay helped me with holds krypton."

Steve caught hold of his shoulder, gripped him with fierce intensity. "How did you get them?"

Dr. Cunningham's blue eyes opened innocently. "Let go, Steve, you're hurting my shoulder." Dodd dropped his hand. "That's better. How did I get the stuff? Simple. I took it." He chuckled. "Took it when they weren't looking. I really was cut out for a burglar. That is a profession. It requires skill, daring, a certain athletic agility"—he winced at the thought of something, looked down mournfully at his trousers. There was a long rip down the left leg. "Yes, sir, I mustn't forget the art of tapping a watchman not too hard on the head, yet sufficient——

"You stole!" Deborah cried, horrified.

Cunningham turned to her with a hurt look. "Stole? No. Just borrowed what those idiots won't need in a few days anyway, unless Steve here——"

Steve shook his head with a groan. "It's too late, George. By four hours. Your larcenous venture almost saved the world against its will. Four little hours!"

Deborah flashed out at him. "Steve!" she spoke rapidly, "never mind the four hours. Get started. Work as you've never worked before. Let every one drop whatever they are doing, concentrate on this one thing. Parcel out the task so that even a hundredth of a second is not lost—day or night. Your reaction-time calculations may be wrong; the nebula may reach here a trifle late; its period of Alteration through earth's atmosphere may prove longer than you anticipate. Hurry!"

Steve sprang into action. His face lighted up, even though inwardly he knew all the data had been checked and rechecked. But feverish work would take their minds off the inevitable doom; hope would still flare. He crackled out orders. The huge house became an ordered bedlam of activity. Every one pitched in—men, women, and even the smallest child—in a gigantic race with time, with onrushing death.