RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, December 1936, with first part of "Infra-Universe"

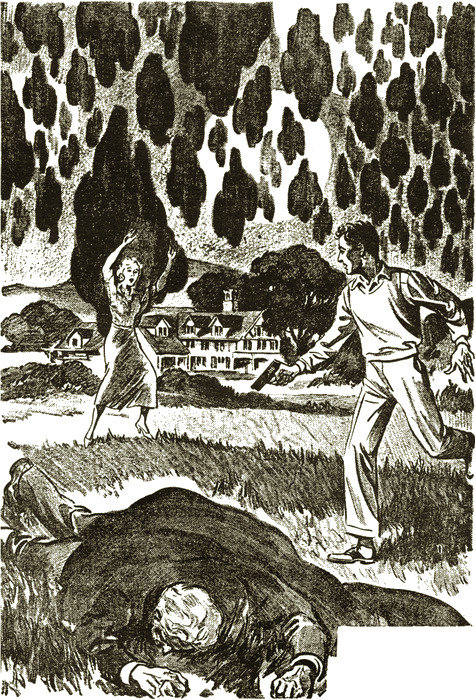

A mass clung to her shoulders, was sinking

swiftly out of sight, into her slender body.

JIM WENTWORTH lifted the old-fashioned knocker, let it drop with a resounding thud. Then he waited, leaning against the newel post that framed the door, and mopped his brow. It was hot, as only a Maine summer day can be, and he had trudged the last weary miles from the railroad station. If he failed in this quest—he grinned wryly—he'd have to walk all the way back to New York. A well-worn silver dime rattled lonesomely in his pocket.

It took a long time for some one to answer. Jim looked about him. The house was as lonesome as his dime; a long, one-story, rambling structure set by itself at the edge of the pine wilderness, with a half mile of dirt road interposing itself between civilization in the form of a concrete highway and its own exclusiveness. A queer place for the laboratory of a scientist like Matthew Draper, Jim reflected; but then Draper had always been known to be somewhat eccentric.

There was no stir of movement, however; and the windows were thick-shuttered. He slammed the knocker again, impatiently. The late-afternoon sun swept over the broad fields like a gleaming sword, illuminated the upper windows of the Harbor House, a mile away. Jim had passed it on his hike; a fashionable summer resort where the wealthy idled and flirted desperately to avoid boredom. He grimaced. It was dinner hour. Over there they would be sitting down to a host of courses, perfectly prepared, impeccably served, while he hadn't eaten more than a sandwich since noon. A sudden fear assailed him.

Suppose it had been a hoax; suppose Matthew Draper was not——

The door creaked, opened slightly. A girl peered warily through the crack. "What do you want?" she demanded. There was a quaver in her voice, a certain desperation.

Jim Wentworth had been trained to detect such things. He wondered, bent forward slightly to make out her features. But the shadows baffled him. Aloud he said: "I came all the way from New York to see Professor Draper. He advertised for a scientific assistant. I fill the bill, and—I need the job." He grinned ingratiatingly, trying to lure the girl out into the sun where he could see if her face lived up to the strange sense of strain in her voice. She refused to be lured. Instead, the thin opening narrowed even more.

"The position is—uh—filled," she declared. "I'm sorry. You had better go. There's a train from Sauk Corners at 7:10." She tried to shut the door, but Jim was too quick for her. His foot shot out, wedged itself into the crack.

"No, you don't," he said firmly. "I didn't spend my last nest egg on a trip to this neck of the woods for nothing. The station agent at Sauk Corners told me I was the only one to inquire the way here to-day. And"—his eye swept the rutted country road—"they'd have to ask to find this God-forsaken place." His sinewy fingers gripped the door edge. "You see, I used to know Professor Draper. I studied under him at Tech some years ago. So I'd rather get it direct from him."

"Oh-h-h!" the girl quavered, thrusting her slight body against the door to hold it from intrusion. Then urgency crept into her voice. "Please go away, Mr.—uh——"

"Wentworth! Jim Wentworth!" he told her cheerfully.

"Please go away," she repeated. "I can't explain, but it's important." She fumbled a moment; then a small, slim hand thrust out into the glare of the sun. "Here's money—for your fare, your trouble. I'm sorry."

Jim stared down at the proffered bills. The hand that held them was trembling. He shook his head, refused to withdraw his foot. "No can do," he submitted. "You're too anxious. I thought there was something wrong when I read the ad. Matthew Draper doesn't have to advertise for assistants. There are thousands of bright young physicists—and old ones, too—that'd give anything to work under him. Now, I've got to see him."

The girl tried vainly to close the door. "Please believe me," she implored. "You must go away—at once. Don't you see—it's for your own sake I'm doing this. I——" She bit her lip, stopped—as if she had said too much.

"You interest me strangely," Jim murmured, and shoved suddenly.

The girl fell back with a startled little cry; the door swung open. Jim stepped into a long, raftered reception room, glanced swiftly around. There seemed nothing wrong. It was comfortably fitted with easy-chairs, reading lamps, tables littered with the latest scientific magazines, and scatter rugs.

Open bookshelves lined the walls, crammed with an impressive array of technical volumes. Among them were a goodly number authored by Draper himself. "The Higher Mathematics of Space" was one; "An Inquiry into the Gravitational Warp" was another. Jim knew them all, knew of his old instructor's preoccupation with the abstruse properties of space.

EVERYTHING seemed normal, perfectly proper. Except, perhaps, that the windows were tight-shuttered, and the lamps that illumined the room glowed with an eerie tinge of violet, as if that end of the spectrum were being favored against the normal yellows.

He took a deep breath. He had braced himself against something—he knew not quite what. Then he remembered the girl. He swung on her. She faced him, fists tiny, quivering balls at her sides. Her face was pale, her eyes wide but steady. She was evidently under a terrific inner strain. Jim made a mental note to study that face more thoroughly—later, when he had more leisure. He was certain the study would be rewarding—and pleasant. But just now——

She came closer, taut, desperate. Her voice was a whisper, as if she did not wish to be overheard. "For the last time," she begged, "will you go—now, before it may be too late! Trust me; don't ask for reasons."

Her urgency, her obvious sincerity, shook his resolution. Before he had seen her full face, he had suspected foul play. Now, that was impossible. But there was mystery here—more! The girl was quite evidently scared. He couldn't leave her alone. And where was Draper?

He grinned tightly. "Sorry, miss," he answered slowly. "I trust you—that's why I'm staying. If you won't tell me what's wrong, Draper will."

"I am Draper," some one said calmly. "What can I tell you?"

The girl stiffened, moved quickly to the nearest table, pretended to be arranging the magazines. Over her shoulder she cast Jim an appealing glance. He understood, swung about to face the man who had quietly entered the room from the left. Through the open door Jim could see a tremendous laboratory, filling an entire wing of the structure. Machinery hummed and glowed, and the pungent smell of ozone flooded the reception room. Then the man had closed the door behind him.

"If you are the Professor Matthew Draper I used to know at Tech——"

Jim started. "But of course you are. I'm Jim Wentworth; took several courses with you back in 1926. Have knocked about a bit since; ran a railroad through an African jungle, got blown up in a rocket-fuel experiment, helped stage a revolution in China against the Japs, did some research under Bentley in California." He went on soberly, "Poor Bentley died; there was a depression; the colleges spewed forth thousands of keen young graduates willing to work for nothing; and I'm on my uppers. I saw your ad—I still remember your space-dynamic theory—and I came."

There was a perceptible, embarrassing pause. Keen, gray eyes seemed to pierce Jim through and through, to penetrate into the innermost recesses of his soul. The girl shifted uneasily at her pretended work.

Then, finally, the man said: "Ah, yes, of course. Wentworth! I remember you now. A brilliant student, one of the few who could really understand my theory. Glad to see you again." But his hand did not go out; and his eyes probed more keenly than ever.

JIM steeled himself with an effort. There was something wrong. He recognized Draper, of course. A little older, a little more gray at the temples, but that was due to the lapse of years. There was no mistaking the well-set, muscular frame, a little above the average height, the firm jaw, the bushy, overhanging eyebrows, the quick, piercing gaze.

But Jim had an odd feeling of discomfort. His old professor had hesitated in recognizing him—and it was a sincere hiatus, too, as if he had to call into play an outside memory, a memory that was not exactly indigenous to him. Draper had been famous for his phenomenal, instantaneous memory. He had been known to stop a total stranger in the street, demand of him whether or not he had on such and such a day, years before, been in Boston, walking on such and such a street at a specified hour. And been exactly right, too, though the startled accosted one had lost all recollection.

There were other things as well. The voice, for example. Draper's, all right, but with a queer intonation, a certain foreign preciseness, as if Draper were making a conscious effort to speak in a fashion that had once been easy and natural for him, but was no longer. In all his bearing, his manner, there was that sense of subtle duality, of alienness, of a deliberate willing to be what should have required no strain at all.

Jim held his features blank and composed, to betray to that searching scrutiny no trace of his inner unease. After all, he was thinking insane thoughts. Before him. without the shadow of a doubt, stood Professor Matthew Draper famous physicist, and propounder of startlingly novel theories on space.

"You'll do," said Draper suddenly. "Miss Gray will show you your room. You can wash, arrange things. We eat in half an hour. Then we'll get to work at once." A strange intensity crept into his voice. "There's no time to be lost. I must hurry. Every moment is precious."

With a little laugh he recovered himself, said more easily. "But let's not talk shop until we enter the lab. In the meantime let me introduce Claire Gray, my very faithful secretary. Been with me for years. Remained even when my assistants quit. I commend her to you for loyalty—uh—Jim." Then he was gone, back through the door to the left.

The girl stared at the new assistant with frightened eyes. Her finger crept to her lip, for silence. "This way, Mr. Wentworth," she said aloud in prim, business-like tones. He followed her, toward the right, into the other wing of the sprawling building. No words passed until they came to the room at the farther end.

It was simple, but adequate: a four-poster bed, a lowboy, several straight-backed chairs, a washstand. Jim dropped his battered bag on the floor, looked at the girl quizzically.

She had shut the door tight, backed against it with pressing hands. Her face was pale, her voice a panting whisper. "There is still time to go, Jim Wentworth," she said breathlessly. "Before dinner. There's an exit through this wing. He won't see you. If you hurry, you can catch the 7:10 at Sauk Corners." Her fright was dreadfully sincere.

"Why should I go, Claire Gray?" Jim demanded gravely. "I need the job, and Draper's the best man in the world to work under."

"You fool!" she cried desperately. "Are you blind? Didn't you see with your own eyes? You knew Matthew Draper back in Tech. Why do you think his assistants left him last week, secretly, at night? Ran away, that's what they did, swearing they wouldn't stay in this place another minute. And they'd been with him almost as long as I have."

"You didn't go," Jim pointed out, evading the questions. He wanted time to think, to piece out the puzzle himself. He was almost afraid of what the girl might say next.

"I?" She stammered and flushed. "I—I couldn't. They begged me to go with them." She raised her head suddenly. "Professor Draper's been like a father to me—my own parents are dead—and I couldn't leave him—in this condition. But you—you're not bound. Didn't you see? Didn't you notice? Hasn't he changed since Tech?"

"We all change with the course of years," Jim again evaded.

"Not that way," she declared. "And the change was sudden, instantaneous. Three weeks ago, in fact. He—he's a different man."

"He looks the same."

"It isn't that," she whispered. "The shell is Draper, the Matthew Draper we all knew. But inside there's something else, something alien, foreign. Something that peeps out at me inquiringly, scares me. I can't quite explain it. It's as if Matthew Draper had been submerged, and an alien entity had taken possession of his body."

"That's impossible," Jim said loudly. He was arguing against his own instincts as well as with the girl. "Rubbish! Nonsense! He remembered me. I'll bet if I asked him about little incidents at Tech he'd remember them, too."

"Of course," retorted Claire. "That's what makes it all the more frightening. But he'll remember them with an effort, willing himself to remember, as if he were doing so through an alien medium—a personality not his own. Broderick and Hanson noticed that at once—in the laboratory. There was an incomplete experiment. Oh, he finished it all right, but unenthusiastically, groping his way. And the solution was a queer one, along lines radically different from the way it had started.

"Then he threw everything aside, all the work that had absorbed him before the—the change. He started a new experiment with feverish haste, ordered materials by the carload, worked night and day, drove them with a dreadful intensity, as if every second counted—almost as if——"

"It was queer, they told me—that experiment, the machines he was building. Something not quite of this world; something outside all our concepts. They didn't understand what they were doing, and he refused to explain. You remember the old Draper—how clear, how lucid his explanations were."

Jim nodded.

THE girl went on, with a rush of words. "The experiment scared them. So did Draper. There were times when he did not think they were looking, and his features relaxed, as if he had been keeping a pose for their benefit. I—I've had that experience, too." She shivered. "It's dreadful—that look—a peep into a strange universe, at something not—not human! They couldn't stand it any more, and they went. They said this experiment might lead to God knew what consequences, and they wanted to be far away when it happened. That's why you must go, too—now."

"You're staying," Jim said very gently.

"I—I told you why," she declared defiantly.

"Then so will I."

"O-oh!" There was a perceptible pause. Then, "I didn't tell you everything," she said quietly. "Three weeks ago a man came here. He appeared to be a farmer—the average type—wind-tanned, face coarse-stubbled, rough-handed. But there was a certain intensity in his eyes. He demanded to see Professor Draper. I tried to ask him his business, but he pushed past me, into the lab. I heard a click, as if the door had locked. Then Draper's voice, surprised, inquiring—and silence. I was alone in the place. It was Betsy's day off, and Broderick and Hanson were at Sauk Corners, awaiting a shipment of supplies."

Her eyes held a far-off look. "I became afraid of the continued silence," she proceeded. "I knocked on the door. No answer. I knocked louder. There seemed a strange, slithering movement, as of something crawling, inching its way along the floor. I must have screamed. I know I started for the telephone, to get help. Then the door flung open, and the farmer came out. Behind him stood Draper.

"But even in the flood of my relief, I noticed at once the strange difference in them both. The intensity was gone from the intruder's eyes; he seemed bewildered, staggering. He looked around the room as if he had never seen it before, as if he didn't know how he came to be here. He muttered thickly, and fled out of the door. He was scared. And Matthew Draper—well—he was as you've just seen him—something alien, distinct. There was a triumphant look to him that was quickly veiled when he saw me. He stared at me—strangely; it seemed to me he was trying to place me, to remember me. Then he went back to the lab, shut the door. I never dared question him since. But"—and now Jim had to strain to hear her whispered words—"when I entered the lab a little later I saw something. A slimy trail across the floor, as though something damp and snail-like had crawled there."

She stopped. Jim's scalp prickled. Then he laughed. "You've let your imagination run away with you, Claire Gray. You've built up for yourself a horrible picture out of the flimsiest materials. The farmer had merely come with a message; perhaps he was a little drunk. Certainly Draper has a right to halt a line of experiments and start a new one. That may explain his change, his seeming preoccupation. He's hot on the trail of something. Such intensity of absorption changes a man, makes him absent-minded, causes memory to be something of an effort. He'll be himself as soon as he finishes."

He talked confidently, trying to convince himself as well as the girl. And failed in both instances. She looked at him quietly a moment, said in matter-of-fact tones, "The dining room is just off the entrance hall, on this side. Dinner will be served in fifteen minutes." Then she was gone.

THE meal passed without incident. There was only Draper, the girl and himself. The housekeeper, a fat, comfortable-looking native of the neighborhood, served with wholesome Maine heartiness, if not with effortless efficiency.

Matthew Draper did not seem disposed to talk much. He ate hurriedly, gulping his food, as if anxious to be done. Jim, alert for little things, noticed that he held his knife and fork a bit awkwardly, as if not quite accustomed to their use. The girl kept her eyes intent on her plate. She looked pale, weary. She did not speak.

Jim was forced to keep the conversational ball rolling. He did it with deliberate skill. He interspersed a casual flow of talk with even more casual references to Tech, little incidents of years before.

Every one of them was answered properly—by Draper. This in itself was strange. In ordinary talk a good many allusions to the past are permitted to drop without further remark. Not so here. To Jim it seemed as if, behind the hurried mask of his old professor, there was a desperate alertness, a wariness, an eagerness to allay suspicion. Yet always there was that gap, that pause, that obvious willing himself into the memory of the incidents. And always that strange impatience to be through, as though every moment were a precious part of eternity that was needlessly slipping through his fingers.

It was with audible relief that Draper pushed his chair back to announce the end of the meal. "That's that, Jim," he declared. "Sorry to rush you so, but we'll have to work a bit in the laboratory. I've got to finish what I'm doing as soon as possible. I must hurry. Hurry!" He seemed to forget their presence. "They can't wait much longer." He was speaking to himself.

Claire flashed the new assistant a stalled glance, looked away again. But Jim said cheerfully, "That's O.K. with me. I don't mind working nights."

The scientist jerked his head up. There was gratitude in his eyes. "Thanks!" he muttered. "Those fools, Broderick and Hanson, left me in a lurch, brought everything to the verge of ruin. But then, how could they know what they did?"

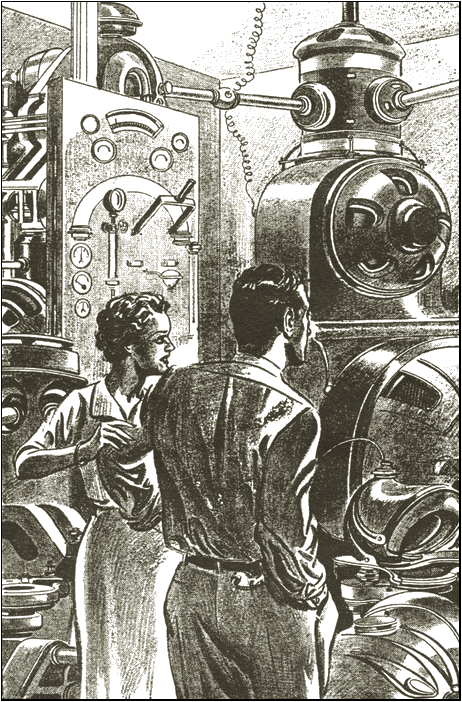

JIM had never seen quite such an array of apparatus in a private laboratory before. There were dynamos for the generation of current, Diesel engines, huge electronic tubes, cloud chambers for the study of disrupted atom tracks, electrostatic globes, great bar magnets, a high-temperature electric furnace for refractory metals, a mass spectrograph, an interferometer, and a profusion of other instruments, some of which Jim, for all his training, did not recognize. It took his breath away.

"Good Lord!" he said involuntarily. "They represent a fortune. I didn't know——" He stopped in embarrassment.

Draper smiled queerly. "You didn't know I was that wealthy, eh, Jim? I'm not. But the name of Matthew Draper is rather well-known; and my credit is good." He chuckled and added, "Especially when no one firm shipped more than a small part of the whole."

That startled Jim; then he forgot the strangeness of the statement in wonder at the apparatus that held the place of honor in the very center of the lab. Whereas every other available inch of space was crowded with instruments, the central portion was scrupulously bare except for this.

A huge, hollow cylinder of gleaming crystal rested solidly on a metallic base. It appeared some eight feet high and five feet in diameter, sufficient, thought Jim incongruously, to house a man comfortably. Fine metallic wire, spaced an inch apart, ran spirally around the transparent circumference, darted upward toward the roof of the lab, pierced through; and, at the bottom, embedded itself in the base of the metal block.

Enringing the cylinder were machines of intricate design. Jim had never seen their like before. Giant metallic mouths, their orifices swirling in queer, distorted curves, making a wavy pattern of gaping wideness toward the central transparency. Like prehistoric monsters, ready to spew forth flaming vibrations at the word of command.

"Good heavens!" Jim ejaculated. "What are those?"

Draper avoided his gaze. "Oh, they!" he muttered vaguely. "Part of the experiment. But come," he added quickly; "we have no time to lose. Must get to work. Please hook up those tubes in series with the cloud chamber. It's already prepared. Use soft X rays, helium, and argon. Shoot them through to get a constant stream of electrons. You know the technique, of course?"

Jim nodded, asked dryly, "For what purpose?"

"Set up your magnets to deflect the stream," Draper went on, unheeding. "That is, I want you to see what happens; take pictures. Hurry, please!"

Jim Wentworth stiffened, was going to retort angrily. This was not the leisurely, meticulous attitude of the Draper of old, the careful explanation of details, of ultimate purposes. Obviously, the scientist was reluctant to disclose what he was about, was laboring himself under a terrific urgency. Jim could see it in every move he made, in the feverish rush from instrument to instrument.

Then Jim relaxed, grinned. Very well, if old Draper wanted him merely as a technician, let it go. But to himself he determined to keep his eyes open, senses alert. He'd solve before long both the mystery of the machines and of Draper himself.

THE electrons broke off from the parent atoms, hurtled across the cloud chamber, made bright lines through the fog molecules, were deflected by the magnets. Everything was normal, usual. fie so reported to Draper.

The scientist jerked erect from the ring of metal monsters, groaned. He was suddenly gray and haggard. "More time lost," he mumbled. "I've got to get back, before it's too late. Try again," he screeched suddenly at Jim. "Step up the current to fifty thousand amperes; pass it first through the Agrav——" He pointed to the first of the queerly shaped enringing machines. "But be careful not to get in front of the orifice."

"What did you call it?" demanded Jim.

"Oh!" Draper seemed confused. "Just a name I gave it. Now hurry, hurry!"

But when, at three in the morning, the cloud chamber sizzled with streaking electrons, the picture was still normal, just as it should have been. Reluctantly, Draper called a halt; grim, despairing. He said good night with a feeble attempt at cordiality, saw Jim out of the laboratory, then closed and locked the door.

The young man was drunk with fatigue. Nevertheless, he stood outside the door, listening. He heard movements within, apparatus being shifted. Draper was continuing on his own. Evidently he did not intend to sleep. Puzzled, Jim went slowly to his room. So preoccupied was he with his thoughts that he almost jumped at the wraith-like figure that loomed up at him in the dark, in front of his door.

"I simply had to see you again," said a girl's voice. It was Claire. Without a word, Jim opened his door, switched on the light, closed it behind the girl. She was paler even than before. She had not slept. "Yes?" he said inquiringly.

"Did you—did you find out what he was doing?" she demanded hurriedly.

For the moment he was angry. What the devil did she mean by pumping him? If Draper wanted his experiment held a secret, it was not her business. Good Lord! Was she a spy for some rival, interested in what Draper was up to? Were there commercial possibilities in whatever it was? Then he grinned. She was too desperately sincere to be that.

"Not a thing," he declared cheerfully. "The old fellow wouldn't talk. And what I did was routine stuff."

She nodded. "Just as I thought. The others said the same. But those horrible machines. They give me the creeps." She gripped his arm suddenly. There was amazing strength in her slim fingers. "And Draper himself. I'm afraid—call it a woman's foolish intuition, if you will—but I'm afraid that something is going to happen soon that will mean disaster to us all—to you, to me, to the whole world, perhaps."

"Nonsense!" He placed his hand on her shoulder gently. She was not the hysterical type, but she was trembling. "It's been lonely here, and you've been brooding a lot of little things, magnifying them." He laughed shortly. "If it'll comfort you, I have a very efficient little automatic in my pocket. I always carry it."

"Guns won't help," she retorted. "But—good night."

FOR a week nothing happened—that is, on the surface. Claire said nothing more to the new assistant of her strange fears. Meals were served on time; Betsy, the housekeeper, waddled back and forth, keeping up a good-natured, interminable stream of meaningless conversation. The atmosphere of the place did not seem to affect her in the slightest. But then, nothing external ever ruffles your true down-Easter.

All day, and most of each night, Jim was in the laboratory. His work branched out. He made new alloys in the electric furnace, of materials furnished by Draper. There were curious, unusual combinations. Some of the products, to Jim's eye, possessed qualities that would mean millions commercially.

But Draper, seemingly, was not interested in that phase of it. He threw them into the discard impatiently, tried new fusions. He was searching for something definite. But invariably, four times a day, Draper would hand him samples of materials that had been breathed forth from the maw of the metal enringing monsters he had named Agravs, for disruption in the cloud chambers. And each time, as Jim, with growing puzzlement, reported nothing untoward in the reactions, new lines etched themselves into the scientist's haggard countenance.

He seemingly never slept. Long after Jim was reluctantly released from duty, in the early hours of the morning, he could hear the whine of the motors in the laboratory. Once he caught a new note; a sibilant, hissing noise, muted by the intervening barriers. Like the hiss of an angry snake. But it held inflections, curious seesaw intonations, as if it were a coherent language of sorts.

A strange reluctance withheld Jim from flinging open the door and discovering the source of the sound. He went to bed, troubled, grim of face. His sleep was disturbed. He tossed in a welter of strange dreams, in which Matthew Draper appeared in Proteus-like transformations.

As the second week grew and waned, a curious bond arose between the scientist and his assistant. The initial sense of distrust gradually wore off. It could hardly have been called liking, or affection; on both sides there was a realization of alienness. But there was a certain respect, an awareness of each other's attainments. Jim did his work doggedly, efficiently, unobtrusively giving valuable suggestions.

Still Draper did not take him into his confidence, or disclose the secret of the Agravs. Nor did Jim attempt any underhanded spying, though his brain worked furiously all day in the attempt to solve the mystery. For he was well aware by now, and Draper knew that he was aware, that some alien entity was inhabiting the body of his old professor, and possessing, besides the brilliance and knowledge of the savant, an additional fund of incredible extent. Knowledge that had not hitherto existed on Earth, that in the main did not seem to fit Earth conditions.

It was this that evidently delayed Draper, or the thing that appeared to be Draper. The correlation and the transference of a body of outside fundamentals to the laws and materials that governed Earth. Jim was able to help here, and Draper appeared duly grateful.

IT had early been forced upon Jim that the experiment had something to do with the properties of space—in fact, an attempt to modify those properties in some unknown fashion. Which was but natural, considering that Draper had been the foremost authority in the world on space and gravitational influences.

A dim light flickered in Jim's brain at that. Could it have been possible that this entity or personality which was now Draper had deliberately penetrated, in some unknown manner, into the form of the scientist in order to avail itself of that authoritative knowledge and perspicacity? Was it, in fact, that rough farmer intruder of whom Claire had spoken? If so, what had happened to Draper? How account for Draper's complete knowledge of his past, of his former associations? What was the purpose of this experiment? Why the dreadful haste? He was obviously racing against some contingent tragic denouement. What was it? Would it involve Draper only, or Jim and Claire as well, or the entire world, as the girl intuitively feared? Questions that troubled Jim through the tossing hours of supposed sleep, and during the furious energy of the lab.

Claire and Jim made it a nightly practice to compare notes in the privacy of the right wing, before going to sleep. Another bond was springing up between them—unawares—but very much of this Earth. Jim no longer scoffed at her intuitions. He, also, was afraid, now. Not for himself, nor, for that matter, of the thing that was Draper. "Whatever he is," he told the girl, "he means us no personal harm. Nor the world, either. His is a tremendous brain, far beyond that even of the old Draper. It frightens me; it's so—un-Earthly. That's the only word I can use to describe it."

"Do you think," whispered Claire, "he might lie a being from Mars, or Venus, who somehow managed to span the gulf and fused himself into Draper's body? Perhaps he's now trying to find a way to get back—the door by which he came had somehow closed in the interim."

Woman's intuition, sixth sense, whatever it may be called! But even she, with all her swift imaginings, could not encompass the entire, incredible truth, the utter incomprehensibility of Draper!

Jim laughed a bit at that. He was too practical, too much of the engineer, to go off into such wild fantasies. "The chances are," he declared, "the explanation, when it comes, will be much simpler, and more within the bounds of reason. What it will be, I don't pretend to know. We can only wait and see."

They did not have to wait long. The denouement came with stunning, unbelievable force. On the Monday of the third week Jim was staring aghast at the cloud chamber, scene of familiar daily routine. Something new had happened, so novel that he could only stare and rub his eyes in wonderment.

The familiar electron tracks no longer bent to the influence of the magnets. Instead, the bright sparkles flashed straight and undeviating across the fog, unheeding of the magnetic pull, to a point almost midway between the plates. Then something else happened. The tracks stopped dead! It was not merely that they collided with some interior substance—that would have been evidenced by a scattering of light, or a sharp-angled divergence of the path; they literally disappeared, vanished! The electrons had ceased to exist!

Jim frowned, glanced surreptitiously back at Draper. The scientist was busy with the adjustments of the spectrograph in the rear; he had not seen the untoward phenomenon.

Jim's brain raced feverishly. Wherein had this particular emission of electrons differed from all the other batches? For one thing, the current had been stepped up another notch; and, for the first time, had passed through the interior maws of the strange Agrav machines in a certain complicated crisscross of alternations, whose pattern he had tried to puzzle out mathematically in the privacy of his own room the night before, when Draper had first suggested it.

The mathematics had been incredible; he had been certain there were errors in his calculations, and had fallen into bed too tired to check his figures. Now, it struck him with blinding realization, perhaps he had been right. There had been exponentials of the tenth order in the resultant equations. Ten dimensions, when the universe of known things was limited, even in the relativity equations, to four!

HE checked himself firmly. He had a simple observational fact to report. That the electron emissions had not bent to magnetic stresses, and that they had disappeared at a given point. Never mind the theories. That would come later. As a loyal assistant, it was his duty to report at once.

But still he hesitated. There was no doubt in his mind that this was the phenomenon for which Draper had been waiting so feverishly. What, then, would happen next? Would he, Jim Wentworth, be the unwitting means of releasing some unknown, horrible doom upon them all? Matter had not yielded to normal, this-universe influences. It had vanished, suddenly, completely, dropped into some hole of which he had no present knowledge. What would it mean if this experiment could be universalized? What did Matthew Draper—or the being who seemed Draper—intend to do with this weapon?

He took a deep breath, walked steadily over to the still-bending scientist. "I think I have the result you've been looking for," he stated quietly.

Draper whirled. Flame sprang into his eyes, and died. "Meaning-——"

Jim explained rapidly, went over the procedure from beginning to end. Then he exhibited the photographic plates to substantiate his eyewitness account. "I've checked for every other possibility," he concluded, "and eliminated them. There's only one conclusion to be drawn. You have managed to divest electrons, at least, from the ordinary attributes of matter. More, you have annihilated matter without any corresponding manifestations of energy. It's a great discovery, one that will set the scientific world on its collective ear."

But Matthew Draper was paying no attention. His face was a stony mask, his body a graven image. But out of his eyes peeped a fierce, unhuman exultation, a flame that seared and burned.

"Thank you, Jim Wentworth," he said slowly. "You possess brains beyond most of your kind, and you have been—loyal, asking no questions, even when you suspected. I shall remember that. Now I ask you to leave me; there is much I must do alone. I shall expect you back at four in the afternoon. Not earlier, not later."

Before Jim knew quite what had happened, he was out in the reception room, and the strong lock to the laboratory had clicked irrevocably behind him.

Claire looked up from her work, startled. She had been answering polite, dunning notes, all of the same tenor: No doubt Professor Matthew Draper had overlooked, in the pressure of his work, their little bill for apparatus and supplies of the instant. Would he favor them with a remittance at his earliest convenience?

The bills ran to staggering totals. To each Claire sent an identical answer—that Professor Draper was away for a week: that on his return he would, without fail, forward the necessary check.

She rose quickly, anxious, overwrought. "What has happened?" she exclaimed, with an apprehensive look at the locked laboratory.

Jim grinned tiredly. "Nothing much, except that I've found for Draper whatever it was he was looking for." And for the second time that crucial morning he explained. "There is no doubt," he finished, "that the man we knew as Draper harbors an another-world entity. He let it slip out of the bag when he thanked me for—er—well, never mind. But he classed all of us together as your kind, thereby differentiating himself from the rest of humanity. Now the question is—what is he up to?"

Claire clung suddenly to him. "I'm afraid," she whispered. "Poor Draper, who had been a father to me—is dead. That which is walking around in his shape is the murderer, an alien being. God knows what else he. is planning."

She moved away suddenly, confused. "Perhaps we'd better get help—the State police—before he does something terrible."

Jim shook his head decisively. "No, that won't do. Whoever he is, I'm sure he doesn't intend to do any harm. Perhaps you were right, though, in the beginning. He was trying to find a way to get back to wherever he came from. Mars, Venus, perhaps. He's discovered it. It wouldn't be right for us to stop him."

"But the Matthew Draper that was!" Claire exclaimed desperately. "What about him?"

Jim frowned, grew grim. "I've thought of that," he admitted. "We must do something to restore him to his former status, if it's at all possible. But a lot of blundering police wouldn't help; they'd only make matters worse. Leave it to me."

THE hours dragged on leaden feet. At lunch Draper did not show up. The eastern wing of the house vibrated with the pounding of heavy machines, with the whine of the dynamos. The acrid taint of ozone permeated the entire structure. Evidently Draper was building up tremendous power. The meal passed in silence.

When Betsy cleared away the last dishes, she announced that she was going to Sauk Corners. The professor had told her to take the rest of the day off. "And if you ask me," she added significantly, "I don't know as I'll be comin' back. I kinda didn't care for the way the perfessor looked when he sneaked over to the kitchen to tell me. He 'peared a bit—well—teched in the head. I'd advise you to clear out, too, dearie," she addressed Claire. "This ain't no place for decent folk." And she flounced out.

Claire and Jim exchanged glances. "I—I think old Betsy is right," the girl said breathlessly. "There's still a chance, Jim. Let's get to the Harbor House. It's only a mile or so. There's a State trooper always on the grounds."

"No," Jim repeated grimly. "But you ought to go with Betsy," he added. "She'll drive you to the hotel. You need the day off, too. You can play golf, idle luxuriously, dance. Stay overnight. I'll pick you up in the morning."

"Jim Wentworth," she declared quietly, "you're trying to get rid of me. You're getting a bit afraid, also. It's no go. Either we leave together, or I'm seeing it through with you." And that was that.

At four o'clock Jim took a deep breath, looked quizzically at Claire, went quietly to the laboratory door, and flung it open. The girl followed him with firm tread.

The great interior was a hive of humming activity. Every dynamo, every motor, was whirring at full speed. A strange violet light bathed every nook and cranny. The galvanometers registered an incredible half a million amperes, voltmeters oscillated at the incredible figure of fifteen million volts. Power surged in almost visible waves through the laboratory. But what held them taut and speechless was the sight of Matthew Draper.

He stood within the crystal cylinder! He seemed taller than before; his eyes were burning coals of frenzied eagerness. His body quivered with impatience. He seemed like a whippet restrained on the leash, tense for the moment of release. Earth characteristics had dropped away from him. Matthew Draper, Earth scientist, was wholly submerged by—what?

Around the shimmering cylinder stood the ring of Agravs; long, squat, metallic monsters, their strangely curved mouths gaping and pointing directly at him. Huge cables snaked across the floor, connecting power machines, great electronic tubes, and Agravs, in intricate pattern. A gigantic knife switch had been cut into the circuit on a panel directly outside the enringing Agravs.

Draper turned at the sound of their entry. The fierce, unrestrained light in his eyes died, gave way to more human emotion. Almost, Jim thought he detected a certain sadness, a certain regret in that piercing gaze. But he must have been mistaken, for the flame leaped back again, more glittering than before.

He gestured to them. Involuntarily, Jim's hand closed tight in his trousers pocket on the flat automatic. It was fully loaded, and a cartridge belt hung snug around his waist under his khaki shirt. He had come prepared for all eventualities.

"YOU are prompt, Jim Wentworth, as usual," said Draper. He expressed no surprise at his secretary's presence. His voice penetrated the cylinder walls without distortion. Jim had often wondered at the composition of the transparent substance, but Draper had not explained, and there were no other samples of it he could have used for analysis. It was not glass, nor quartz. At the most, Jim had determined that its crystalline structure was arranged in polarized planes, parallel to the axes of the Agravs.

"At exactly ten minutes after four," Draper continued, "you are to close that switch." He pointed to the newly installed panel. "By exactly fifteen minutes after four, you are to be out of the house. You'll find my car on the driveway. The motor is going. The tank is full of gas. Get away without an instant's delay, and don't stop until you reach the Harbor House. And don't come back! That is imperative. My instructions must be followed minutely; the slightest deviation may mean disaster. And—you will find an envelope addressed to each of you at the Harbor House. You will both find yourselves amply rewarded for your work. That is all."

"Go away and do not come back! My directions must be followed

minutely; the slightest deviation may mean disaster!"

Claire save a little gasp. Her hand went out blindly to the man at her side for protection. Jim's lips tightened; he took a half step forward. "Now listen to me, Matthew Draper, or whoever you are," he rasped. "This farce has gone on long enough. I have, as you say, been extraordinarily patient; but it is time now for the show-down."

The scientist within the shimmering cylinder stiffened. A palpable wave of force seemed to lash out from his flaming eyes. Then he swerved to the electric clock on the wall. Its hands pointed to two minutes after four. "Have your say," he replied calmly. "You have eight minutes time. Not a second more."

"I have this to say," Jim retorted grimly. "You are not Matthew Draper; you are some strange being, entity—God knows what—that took violent residence in his body. I demand answers to the following questions: Who, in Heaven's name, are you? Where have you come from, and for what purpose? What have you done with Matthew Draper? What forces are involved in the manipulations of these monstrous Agravs? And what will happen when I pull the switch?"

"First, I must say this: "You are not Matthew Draper;

you are some strange being, entity—God knows

what—that took violent residence in his body. Why?"

"Softly," answered Draper with a tinge of mockery. "I would not have time to answer all your questions, even if I wished. But I do not wish. It is enough that you have guessed a dim part of the truth. I am not Matthew Draper. What I am, does not matter. You would not, could not possibly believe the real truth."

"I know the truth," Claire cried out. "You are a Martian, or a Venusian—a being of some other planet."

Draper smiled queerly. "I am not of your Earth; that much is true," he admitted. "But I cannot tell you more. The knowledge would make you mad, it would sound so utterly incredible to your limited intelligences. Enough that I have been here; am now returning.

Earth will know me no more." His voice took on steely determination. "Nor any more of my fellows, if what I propose is successful. And that, my Earth friends, you will discover to be of infinite advantage to you, though it is impossible for me to explain.

"Nor shall I explain the workings of the Agravs. You, Jim Wentworth, would have sufficient intelligence to reconstruct them. You, or others of your race, might foolishly try to follow into my world, in spite of all warnings. Such a course would prove disastrous to you, and possibly to us as well."

"Eve discovered this much," said Jim. "The cloud chamber experiments gave me the clue. Their emanations do things to space, and to matter. The ordinary laws no longer apply. Magnetism, light, heat, yes, perhaps even gravitation, have no influence. And the matter vanishes—where to, I have not been able to determine. Perhaps into a fourth dimension."

"You have discovered more than you should," said Draper, biting his lip. "Though the full, incredible truth is beyond your imagination. Perhaps I should destroy you before I leave; it might be wiser."

CLAIRE cried out; Jim's finger tightened on the trigger of his concealed automatic.

"But it is not necessary," continued Draper. "For, at four thirty, this building, and all it contains, will be thoroughly destroyed. I have seen to that. The place is mined with explosives, and a clockwork mechanism will set it off. That is why I gave you warning to leave immediately after you have performed your appointed task."

Jim compressed his lips. "That is just what I won't do," he declared, "unless you return Matthew Draper to us, alive and unharmed."

Draper's brow darkened. "It is impossible," he said angrily. "I am a part of him and he is a part of me. My continued life depends on this community of intra-position. It is unfortunate, but he must accompany me to my destination. Now hurry," he added hastily, hi'-, eye flicking to the wall clock. "In another minute, exactly, the switch must be pulled."

Jim settled hack comfortably on his heels. "Release Draper then," he insisted.

"I told you it is impossible," the immured scientist cried out in exasperation. "I've trusted you, Jim Wentworth. A clockwork mechanism to activate the switch might have gone astray; you, I thought, would not fail. You must believe me. It means disaster to a mighty race, to your universe as well, if you don't obey."

"Release Draper," Jim repeated stubbornly.

The clock ticked on. Ten seconds to go. "Fool!" shouted the man in the cylinder in an awful voice. "Do it now, or it will be too late."

Claire plucked at Jim's arm. "Quick! Obey him! He's really sincere. Something terrible will happen."

Jim shook his head. "He's bluffing; that's all."

Five seconds of ten after four!

Draper literally cowered. His face was a dreadful mask of anguish. "Claire Gray," he said thickly, "believe me! Your fate, the fate of all the universes, depend on knifing the switch. Quick."

Her eyes widened on him. "I believe you," she screamed suddenly, and darted for the panel.

Jim whirled, shouted savagely. "Tie's bluffing, I tell you. Don't touch it!"

"He's not," she panted. Her fingers reached up, pulled desperately down. The second hand clicked into the last position.

Jim grunted an oath, sprinted. If that switch made contact, his trump card would be gone. They would never see Draper again. What reason had they to believe that the entity in the cylinder was telling the truth? Perhaps the transparent material was a shield of force, to protect him from what was going to happen. How did they know that they would not unwittingly bring disaster to an unknowing world? Given time, he'd force the truth out of the man in the cylinder.

In his mad, forward rush, he collided with the snout of one of the Agravs. It pivoted around on a turntable, oscillated back and forth with the jarring vibration. Jim had no time to think of that. His sinewy hand jerked forward, caught at Claire's wrist. Too late! The blades made contact with an irrevocable click.

The violet flame deepened. Great sparks flared and sputtered over the copper flanges. It would be suicide to try and grasp the handle now. There was a humming noise that grew quickly into a full-throated roar.

Claire sobbed, "I shouldn't have done it, Jim!"

The roar grew louder. The building rocked with vibration. And high above it the half-outcry, half-piercing hiss, of Matthew Draper. Jim whirled. The cylinder was aglow in the violet bath. The spiral casing of wire flared a fiery red. The man himself was a gleaming torch of radiance. But his finger pointed desperately to the solitary Agrav which Jim had knocked askew.

It was oscillating on its pivoted base in a wide arc. Palpable vibrations, waves of violent cracklings, issued from its twisted mouth, steeped everything in its path in the strange, torch-like radiance. Apparatus, walls, hazed and became transparent. Beyond their confinement, the outer fields appeared; sky, road, the distant Harbor House. Then they, too, hazed and shimmered with violent transparence.

Then Claire's cry came to him, faint, far-off. He swung around again. She, also, was a flaring, misting waviness.

Her features blurred, mouth still open with the faintness of her cry.

Too late, Jim realized what he had done. With a groan he sprang for the wide-swinging Agrav. Or rather, tried to spring. For the curved maw, in its oscillation, bore directly upon him. The crackling waves spattered over him, past him. Something happened. A curious sense of lightness, of floating on air. His limbs seemed independent of his shrieking will. The universe seemed to flatten out, to roll away from him like a lifting curtain from a stage.

The laboratory receded into nothingness; so did Claire, the Agravs themselves. Only illimitable violet radiance remained. He was dropping—no, that was not the sensation, for that involved a feeling of weight, of gravitational tug. He was being released from the trammels of space, was emerging from its confines, was leaving it far behind.

The enveloping light roared and sang. It grew to unbearable intensity. There was a vast, soundless explosion, as if the universe itself had burst asunder. And with it, the individual who once had been Jim Wentworth seemed to burst into a thousand million sundering shards!

JIM WENTWORTH looked about him dazedly. His senses were still scattered, his mind not functioning efficiently. He seemed to be sitting at an angle, as if somehow he had landed on a mountainside. He struggled, half conscious, to his feet, and slipped. He tried to hold himself, couldn't. Down the smooth, steep floor of the laboratory he slithered, until, with a crash, he brought up, breathless and bruised, at the solid wood of the wall.

Warily he arose again, tried to get his bearings. The wall sagged away from him at a steep angle. It was but a semi-shell. Loose apparatus huddled in a smashed heap at its base. It extended its full length, but the inclosing sides were cut off abruptly.

Slowly, he turned, looked up at the place from which he had just tumbled. He caught his breath. The tilted floor of the lab was cut off as abruptly as the sides of an arc convex to himself. Beyond was—nothingness. Or rather, a faint cerise glow that extended interminably, seemingly to infinity itself. Nothing moved in that circumscribed expanse; no Sun, no Moon, no stars, no clouds.

He was thoroughly awake now. The Agravs had been in that upper part, so had the cylinder inclosing Matthew Draper. They were gone, with the rest of the house, the Maine woods, Earth, the universe itself. Swift pain stabbed suddenly through him. Where was Claire Gray?

As if in answer, a low moan came to him. He swung precariously on the angled floor, saw something stir in the heaped wreckage against the wall. He skidded toward the huddled girl, lifted her in his arms. She was alive, her eyelids fluttering. A shallow gash bled freely on her forehead. But—and he heaved a great sigh—she was alive!

He stanched the flow with his pocket handkerchief, rubbed her limbs briskly. He had no water. She opened her eyes, stared bewilderedly around. "What happened? Where are we?"

"I can answer the first question easily enough," he told her grimly. "Draper was right. My fool rush to stop you jerked one of his confounded Agravs around. We got the same dose that was meant only for himself, within the guarding walls of the cylinder. But just where we are is another matter." He pointed upward at the illimitable cerise. "There's one answer, and it looks senseless. The other must be on the other side of this wall." His face tightened. "We're going out to see."

IT was difficult picking their way through, the strewn rubbish. The door sagged crazily, and required force to swing open. The reception room was level, untouched. Nothing seemed to have happened in here. Jim stared. "That's funny," he muttered. Perhaps it was only the explosion that upended the lab—or what is left of the lab." New hope stirred. "Maybe that cerise business is only an optical illusion, and everything is as it was. Maybe——" He paused, grinned. "There's only one way to find out."

The lights still burned in the room. The windows were tight-shuttered. His hand gripped the knob of the door that led to the open. He looked at Claire, took a deep breath, flung it wide. A cry broke simultaneously from both. It was a cry of gladness.

The peaceful Maine countryside shimmered lazily before them. There was the meandering dirt road, the waving fields of grain, the several farmhouses, with the gray smoke curling slowly into the sky. In the distance, the Harbor House lifted its many windows. A man even, a normal human being, was trudging down the road toward them.

"Thank Heaven!" Claire said in a choked voice. "It was all a dream, a horrible nightmare."

But Jim's eyes narrowed against the glare of light. For one thing, it was faintly tinged with cerise—not the honest yellow-white of sunshine; for another, there was something strangely familiar in the dress, the walk, of that approaching figure. The man lifted his bowed head. Jim groaned. "I was afraid of that," he whispered.

"What?" demanded Claire. "Isn't everything all right?" Then she, too, saw the man. He was close to them now. A little cry broke from her. "Matthew Draper!"

Draper nodded wearily. His face was haggard and seamed with new lines. "Yes," he answered simply. "The old Draper; the vanished one to whom you remained loyal in spite of everything." He passed his hand over his brow. He was trembling. "Lord! What a horrible experience!"

Jim stared, bewildered. The alienness had gone out of Draper. There was no question of his complete Earthiness. Claire sobbed joyfully. "We misjudged the other. He released you after all; went back to his own world without harming any of us in the least."

Draper shook his head sadly. "You haven't seen. Look!" He pointed upward.

Heads flung back, they saw for the first time. High above, swimming in a cerise void, three suns, gigantic, rotating rapidly on flattened axes, one a deep orange, another a canary yellow, the third a dark blue, whirled around each other in swaying, complex orbits. The sky of Earth ended abruptly not over a mile overhead, cut off sharply and cleanly from the illimitable, superimposed cerise as with a knife.

Far distant, to one side, and over the Harbor House, hung a gigantic silver globe. Its metal-seeming surface was studded with flaming sparkles of light whose hues shifted with the majestic sweep of the multicolored suns across its gleaming convex. Jim rapidly estimated its distance as a thousand Earth miles, its size somewhat half that of Earth itself.

"We've been transported to a system in some distant nebula," he said aloud. "The home of the being who took your form, Professor Draper. The entire Earth has been shifted."

Draper shook his head again. "He warned you the truth would be incredible," he said. "Look behind you, for one thing."

They turned. The ground lifted up at a steep angle, even as the laboratory floor had done. There was a knife-like ridge, then—nothingness. Or rather, the infinite cerise of a space beyond their wildest dreams.

The Earth had been cut off sharply, in an arc convex to them. In that immense inane, far off, so far it seemed but a tiny green disk, was another globe, solitary, green-tinged, swimming in the impalpable, all-pervading glow. No suns spread their kindly rays over its surface; the dull green of its somber metal absorbed, rather than reflected, light. Claire shivered. "It's somehow sinister."

JIM turned slowly to the scientist. He was beginning to understand—and the knowledge left him shaken. "I gummed up the works. The Agrav I knocked out of line precipitated a segment of Earth into this nebula, universe, whatever it is, along with the entity that had taken possession of your body."

"A segment of about one hundred and twenty degree spread, with a radius of ten miles, a depth of some two miles, and an atmosphere of not over a mile," Draper confirmed. "Back on Earth, North America is being shaken by tremendous storms, due to the vacuum created; and, no doubt, later, there will be scientific expeditions to puzzle over the vast hole in northwestern Maine; and deep lamentations over the hundreds of people who were whirled with it into nothingness."

Jim said grimly. "Of course! I'd almost forgotten. There are others with us in the same boat." He waved toward the distant Harbor House, and laughed mirthlessly. "The nouveau riche, the pampered wealthy! Swell company for an incredible adventure like this! Bet they're still dancing, playing golf, not knowing what struck them. Imagine some one's astonishment, on the eighteenth hole, slicing a ball suddenly into a newly created hazard—a cerise nothingness."

"They're not so bad," Claire defended them. "Some of them are quite nice." Jim looked at her quickly. He was surprised at an unsuspected twinge of jealousy within him. But there were more serious, more tremendous problems at hand. "Before we go off half cocked, we'd better take stock, get our bearings." He addressed Draper directly. "Do you know where we are?"

"Yes." An odd reluctance made the scientist hesitate. Then he made up his mind to frankness. "You might as well know. Perhaps it'll help. We're in a different universe." He held up his hand in warning at Jim's half-sceptical nod. "I don't mean merely another galaxy, like the Great Nebula of Andromeda; we're out of our space time completely."

Something tightened around Jim's heart. "You mean another dimension?" he asked.

"Worse than that," Draper retorted. "I told you the truth would be incredible. We're in a place where even the dimensions have no meaning."

"Suppose you explain." Jim grunted. Claire said nothing. She was overwhelmed.

"It's rather difficult," the scientist submitted, "but I'll try. Before Einstein and relativity, our universe, space, was supposed to be infinite in extent. Journey as far as you wished, in any direction, for an infinite time, and you'd never get to the end of the universe."

"Go on," urged Jim.

"With Einstein, however, the conception changed. The size of our universe, or better still, space time, depended on the quantity of matter in the universe. Matter created space time, warped it around itself. The warp was, in itself, gravitation. But mathematical calculations proved the amount of matter to be limited. Hence space time itself is limited, warped around the universe matter in a gigantic hypershell, unbounded, because it is globular, but finite."

"That much we knew," Jim said.

"YES, but few have speculated as to the obvious problems arising out of this conception. True, it was known that the universe was expanding, eating into outer nonspace time, warping it into the familiar gravitational pattern around the outrushing nebula, but hardly any one ever thought to consider the inner core; in other words, what was inside of this hypershell of space time which constituted our universe.

"Those who did, like Eddington, ducked the issue. He maintained that only the skin, or shell of the hypersphere existed—that the skin existed without any inside. But my own researches, even before this—this happened to me, had convinced me that there an inside. And I am proven incontestably right by this terrific transposition of ours. We are no longer in our own universe, or any universe of the hypersphere of space time. That is a shell outside of us, inclosing us, yet as infinitely remote as if it held no existence.

"We are within the superimposed round of the familiar universe—we are the inside—in an incredible space time with completely novel properties."

"I was afraid of that," Jim said slowly. "We're on a mere sliver of Earth, sliced off by my own incredible folly, catapulted into something even more incredible than my folly, marooned for all eternity."

"It wasn't your fault," Claire cried warmly. "It was mine; for believing that—that other-universe creature who was——" She turned swiftly to Draper, awed. "Where, then, were you all that time?"

The scientist shivered. "If I live an eternity, I'll never forget the horror of it," he declared fervently. "It started with the abrupt visitation of the farmer. He was a farmer, but Insar had already pierced the unfathomable gulf from here into our hypershell, contacted Earth, and interpenetrated himself into the form of that poor, unknowing fellow. For Insar, as I discovered later, is an incredible entity, a colloidal, formless mass, structureless, alike in every part—and lifeless."

"Lifeless?" echoed Claire and Jim simultaneously. "That superintelligence lifeless!"

Draper puckered his brow with frowning thought. "It's hard to understand. I admit. Even I find it difficult; though, when we were fused together, so to speak, I caught glimmerings from the contact of his vast mind. It seems that he and his fellows are what, in our universe, would be considered that twilight borderland between living and nonliving matter.

"They are primal compounds, an interfusion of pure matter and pure thought—the two great principles of all universes. Yet they are neither one nor the other, nor separated as we find them. There is no structure—on the one hand, into electrons, protons; on the other, into the unknown vibrations we term thought, intellect, soul, if you will. Only when such structures are furnished them may they function and live. At least in our universe.

"Here, where the laws of being are different, no doubt these essences of pure thought and pure matter have an uninhibited life of their own, all the more vast and splendid for the lack of restrictions of body and structure."

"That sounds," Jim interposed excitedly, "like a description, only on an infinitely vaster scale, of certain strange borderline forms that were only recently discovered on Earth. I mean the ultraviruses. They, too, have been assumed to be lifeless, unable to propagate, vet, on contact with living forms, such as bacteria or animal tissues, they display activities similar to those of life. They absorb the living tissues; they grow and reproduce their kind They range in size from an organic molecule in unbroken grade to the tiniest of the bacteria. Some of our most terrible diseases are caused by them."

DRAPER looked startled. "I've heard of them, vaguely. They're, of course, out of my field. But it does sound like a striking similarity." Whereupon he dismissed that angle of it, and proceeded with his personal narrative.

"As I said, Insar required an Earthly form in order to manifest an Earth life. The farmer was evidently the first material at hand. But he was rather poor material for his purposes. I gathered that Insar, for some reason, had been exiled from his own universe, had been thrust unwillingly into ours. He wanted to get back, and some dreadful urgency drove him to a furious haste. He required an Earth intelligence more advanced, an Earth body more likely to get him the apparatus and supplies he needed to build his Agravs, than the farmer. He found me."

Draper blushed, stammered. "I don't mean that I was such an intelligence, but——"

"Insar was quite right in his choice," Jim interposed.

"Well—anyway—I was close at hand to the travel possibilities of this Maine countryman; I had a laboratory which held a good deal of apparatus useful for his purposes; and I knew something about the particular problem he was attacking—the piercing of space and its concomitant, gravitation. I don't know exactly what happened. But when the strange intruder burst into my laboratory, and stared at me with remarkably intense eyes, I must have fallen asleep.

"When I awoke, the visitor was gone, and I was—well—some one else. A new entity interpenetrated all my being, dominated my physical movements, drained my thought processes, was something that was not I. Yet all the while I was aware of what was going on—a potential, rather than an actual being. It was a choking, helpless sensation, such as one gets in nightmares."

He stopped, shivered again.

Jim had a swift vision of an incredible, amorphous body oozing out of the immobile farmer, inserting itself into all the interstices of Matthew Draper, becoming Matthew Draper; and he also shuddered.

"He quit your form on his return to his own universe, I suppose," he said aloud.

"Yes. I found myself suddenly walking down this road toward you."

"And the principle of the universe transposition?" Jim persisted. "Of the Agravs themselves? Did you get any inkling?"

"I was on the verge of it, in theory at least, before Insar came. Space is merely an attribute of matter—its clothing, so to speak. Gravitation is an attribute of the warp of space. Yow suppose it were possible to dissociate the clothing from the man; in other words, matter from its warp of space. What would happen?"

Jim puckered his forehead. "Matter would cease to exist in our space time. The laws of space would no longer apply. Gravitation among them."

"Exactly. Somehow—I don't pretend to know the process—Insar was able to flatten out the space that surrounded us by means of a vibration that emanated from the Agravs. By so doing, he withdrew us, and all of Earth within range of the machine you set swinging, from the properties of our space time. We were, in a way, free of our universe.

"Then it was that the interior universe, hitherto circumscribed, was enabled to act upon us, draw us toward it. There is no way of telling how long we dropped through a space time that flattened always out of our path, into this new space time. It might have been an instant; it might have been millions of years. But then, our concepts of time must perforce be discarded."

Jim started to his feet. They had been sitting on the steps that led into the house. "Other universe or not, I find Earth appetites asserting themselves with normal vehemence. I'm hungry."

"So am I." Claire piped up.

Draper smiled. "We carried with us, on this small segment of Earth and layer of atmosphere, all of Earth's properties. I must sorrowfully confess that I could eat, too."

THEY found, fortunately, that the kitchen was intact. There was ample food for at least a week. After that Jim shrugged. He felt better now that he had eaten. New vigor stirred in him—the vigor of pioneer forbears.

"If this is to be our new world," he said buoyantly, "we had better get it organized. There must lie several hundred people scattered on this sliver of Earth, wondering what it's all about. We've got a job ahead."

His eyes kindled; he proceeded with mounting enthusiasm. "Think of it; a bare hundred Earth people, marooned in a universe beyond their former imaginings, clinging precariously to a few square miles of ground. With these we must rebuild a civilization, provide food, shelter, clothing for all the generations that will spring from us, take our part in the immensity of the inner universe.

"Perhaps"—and he turned brooding eyes aloft at the rainbow-hued suns, the gleaming vastness of the silver sphere; a more somber glance at the dull-green, tremendously remote orb that seemed to cast a blight on a cerise infinity—"perhaps we may in time find a way to migrate to those other worlds, or planets, and find a larger sphere for our talents and activities."

"Captain John Smith leading the colonists to a new world," Claire contributed gayly.

A certain grimness settled on Jim. He was staring out at the Harbor House. "And like John Smith," he growled, "for the main I'll have a pack of lily-handed gentlemen—and ladies—who never did a day's work in their lives, and will expect those who did to continue to perform for their special benefit."

"You are rather bitter against the guests of the Harbor House," Claire said wonderingly. "Why?"

"Because," he answered fiercely. "I've had to work for what I got all my life. I've tried, in my modest way, to create things, whether it was railroads, or bridges, or help some one else advance the world's stock of knowledge a bit.

"Matthew Draper has done very much more—he thrust back the boundaries, made man a bit nearer the stars." He grinned suddenly. "Or nearer Infra-Universe, as it turned out. But, over there, they have been mere parasites, living on others' labors, contributing not a whit. Well," he went on grimly, "they'll contribute here, or damn well starve."

"They're not as bad as you paint them," Claire said softly. "I know a good many of them. You forget—or rather, you don't know—that when father was alive, I, too, was a gilded lily, and stopped at the Harbor House."

He looked at her queerly. "That's all been burned out by the fires of adversity," he retorted gruffly. "You've been doing your bit."

"We're running a little ahead of the picture," the scientist interposed. "We'll be at the most a mere handful, and obviously vastly inferior to at least some of the denizens of this new universe. That is, assuming that Insar was a fair example."

"We can't even assume that," Claire objected. "He had been exiled, cast out, by his own admission. That means there are others, more powerful, who were his enemies. Which also indicates that all is not peaceful in Infra-Universe, any more than it is in our own world."

"Exactly," Draper agreed. He shook his head gravely. "Our problems will include not only those inherent in adjusting ourselves to a new environment, but the possibility of conflict with unknown, and unknowable, forces and beings." He stared across infinity with troubled gaze. "I'm afraid we'll have to reckon with one of those spheres before long."

"Not the nearer one," protested Claire. "It's too beautiful! That must be Insar's home. It's that far-distant orb of green, solitary in the immensities as if there were a curse upon it, that sends cold shudders up and down my back every time I look at it." Wherein, as is usual with woman's intuitions, she was partly right and partly wrong. The entire truth was too complex and terrifying for hyper-universe instincts.

"Insar was racing to avert some incredible catastrophe," Draper murmured. "I wonder if he has succeeded."

"We're speculating idly," Jim declared with practical common sense, "and wasting valuable time. If we don't get started organizing this poor, exiled little sliver of Earth in a hurry, nothing else will matter very much. We'd better take stock, find out what our resources are. Come on!"

As they trudged down the rutted dirt road toward the concrete highway—fitting symbol of their strange predicament, beginning in abrupt nothingness, and terminating in the void—Jim said: "I've been wondering why, with the mass of our world reduced to infinitesimal proportions, don't we feel a difference in the gravitational tug? According to our hyper-universe laws, we should be incredibly light; the least of steps should send us soaring off the surface and out into the void."

"I've been thinking of that, also," Draper confessed. "The only explanation that occurs to me is that the Agravs tore away, along with us, an inclosing strip of space, warp and all. If our space is of a different order from that which exists in this Infra-Universe, then they wouldn't mix, in the fashion of oil and water, and the warp would remain constant, even though the residue of matter no longer possessed sufficient bending qualities. Which naturally would mean that the gravitational tug would not have varied."

THE first human habitation to which they came was a farmhouse. Green fields surrounded it, ripe with the dark of potato plants, with the yellow of tall, waving corn. A sleek cow turned wondering eyes at them, swished her tail lazily at the buzzing insects, and returned to the serious business of chewing her cud. An old sow suckled a squealing brood of future hams and rashers of bacon, oblivious of fine distinctions between one universe and another. Gray smoke curled lazily from a bedraggled brick chimney. Everything was peaceful, inert, with the brooding sultriness of late summer.

"One problem seems to have solved itself—at least for the while," Jim said joyfully. "Food!"

"Why, they don't even seem to realize what has happened," Claire burst out wonderingly.

"Of course not," Draper commented. "They just fell out of one universe, and into another; earth, fields, atmosphere and all. Strange suns and silver-shining globes mean nothing to cows and pigs. You felt the shock of disruption because you were at the very edge of the change. They wouldn't."

Jim shouted, "Hello, in there!"

There was the slow stir of feet within, the scraping of chairs. A figure blotted out the door space, peered out. "Howdy, strangers!" it said in a cracked, high-pitched voice. "Seems as if I hearn you call."

He was old and gnarled, and weathered by many summers and winters. His lantern jaws were still chewing vigorously. He had been disturbed from his evening meal.

"Gracious heavens!" Claire whispered unbelievingly. "He doesn't know!"

"You all right?" Jim queried.

"Why, sure!" the farmer returned wonderingly.

"And the rest of your family? All inside and O.K.?"

The man turned in some bewilderment to the dark interior. "Maria, Amos, Sal!" he called.

There was a confusion of voices, a dull thud of movement. "What's the matter, pa?" A stout, slatternly woman in faded gingham edged him slightly away from the door, stared at the intruders suspiciously. Two tow-headed children, bright-eyed, inquisitive, peeped out from behind their mother's skirts.

"You ain't tax collectors?" she demanded.

"No, just checking up," Jim responded cheerfully. "You haven't noticed anything wrong?"

"Why should we?" she snapped. There was no doubt as to who was the head of this particular family. "Exceptin' for strangers who disturb us at our meal," she added meaningly.

"Sorry we had to do that, ma'am." Jim bowed gallantly. "But it was necessary. You're not in Maine anymore, and life is going to be a bit different from now on."

"Not in Maine?" husband and wife chorused. A tinge of anger crept into the woman's voice. "Ye're jokin', stranger, and I ain't keen on jokes."

"Not at all," Jim assured her gravely. "If you'll just step out into the open and look at the sky, you'll notice the difference."

They all piled out at that, and stared, mouths agape, eyes round like saucers, at the incredible sky. The children reached up grubby fingers.

"Pretty!" said the little girl.

The boy started to howl. "Gimme!" he cried eagerly, pointing to the flashing sphere.

The woman compressed her lips with a snap. "It's a fake!" she said decisively, and glowered at the bringers of the news. "C'mon, Hiram; ain't got no time to be wasting on suchlike. Supper'll be gittin' cold."

"Yes, Maria," he answered meekly. "I'm a-comin'."

It took exhausting explanations to convince them the sky was not a show, put on by the strangers for some cryptic reason of their own; that they had been carried, willy nilly, into a strange and unknown universe.

WHEN the three, who perforce bad assumed leadership of the new state of affairs, had ended, and Draper had surreptitiously mopped a perspiring forehead, they were still only half convinced.

"Well," declared the woman reluctantly, "Mebbe it's so. But I don't see as it's much concern of our'n. We kin git along, wherever we be. Crops'll grow, and cows an' pigs'll litter." She slapped the children suddenly. "Stop gawping!" she scolded. "Ain't I told you time'n again never to gawp at people. Git inside!" She was already back inside the door. "Thankee, strangers," she called back. "But there ain't no call to go worryin' about us."

The old farmer shrugged, winked stealthily at his visitors, followed her in. The door slammed shut.

The three looked at each other. Claire suddenly doubled up with laughter. "They're just entering the most tremendous adventure that could possibly happen to human beings," she gasped, "and all they're afraid of is their supper getting cold."

"Whew!" Jim whistled. "And I was scared stiff of frightening them out of their senses!"

"The remarkable elasticity of the human spirit, or more accurately, the remarkable resistive inertia to all shattering novelties, is nowhere better exemplified than in down-East Yankees," said Draper. "Which, under present conditions, is rather a blessing."

They passed several other farmhouses on the way. In some, the inhabitants had noticed the change-over, and been mildly interested; in others, the men were taking advantage of the inexplicable length of the day to collect their hay, to finish up daylight chores. For the fragment of Earth was stationary in the vast inane, without rotatory spin or forward revolution. The three many-hued suns gyrated interminably overhead. It would always be day.

Life went on!

THE HARBOR HOUSE hove in sight. Here, if anywhere, in this abstracted sector of Maine, there would be panic, confusion, vast wonderment.