RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, October 1935, with "Intra-Planetary"

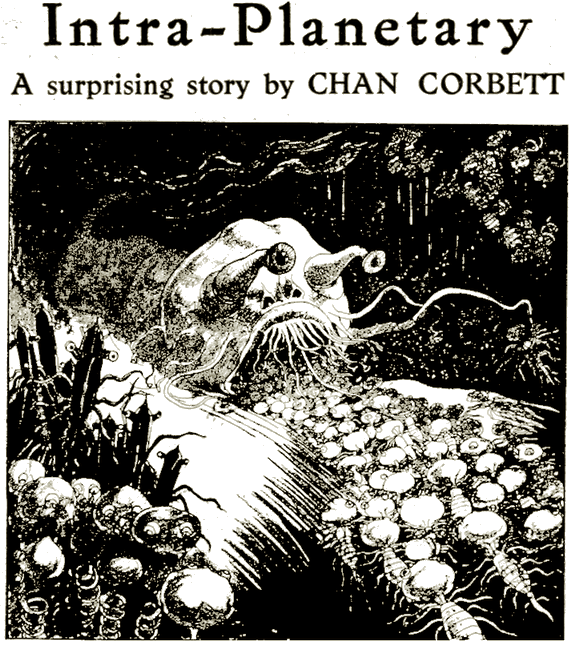

With a savage roar of vibrations the

ranks surged through the white monster.

TUBO was weary and a bit afraid. This was his fourth journey through the tremendous reaches of outer space, yet he liked it no more than he had the first. Even in the new space skin he had recently invented and been the first of all his tribe to use, the risks were desperately great. For the vast emptinesses between the worlds of his universe were peopled with strange terrors and unimaginable dangers.

Tubo felt a shudder pervade the semi-torpid roundness of his huddled being as he peered through the pale translucency of the enveloping space skin. He was helpless, exposed to the cruel sportiveness of chance. All the frantic science of those last feverish moments within the expiring world had been unable to gain him the secret of motile navigation in space. The strong currents that blew through the universe swept him about in aimless progression.

All around, in tempting profusion, bathed even as he, in the strange, fierce glow that permeated all space, moved inviting worlds, elongated, breasted the universe currents with erratic, incalculable orbits. How many times had he attempted to plot the path of the world he had recently quitted, to bring it within rigid mathematical laws, and failed?

Ah! That last sweep had brought his sheathed, protoplasmic form almost to the very surface of a lovely, heaving planet. He pushed violently with all his uncomplicated fluidity against the hardness of the space skin in a vain attempt to hurl himself upon that beckoning surface.

If only he could make contact, attach himself. In seconds he would have burrowed into one of the innumerable tunnels that led from the glow-exposed surface into the soft, warm, welcoming darkness of the interior. Life there was luxurious and food was to be had for the gulping.

But alas! A mocking cross-wind of space, a swift, incalculable swerve on the part of the plunging planet, and he was once more buffeted in emptiness. The terrible glow of the universe was beginning to take effect upon Tubo now. It was this inimical radiation that constituted the greatest hazard of space travel. It shriveled and seared and burned—even penetrated through the protective sheath in which he was enfolded.

He felt his body growing hard and taut. His delicate senses measured the rate of evaporation. His mind sped with lightning swiftness through intricate calculations. He had five minutes more of universe-time before the radiations would shrivel him to a lifeless husk. In that period he must effect a landing on a proper planet, or else——

Tubo was a great scientist, the greatest of his tribe—for that matter of all the tribes that peopled the planets of space. Other tribes had better natural protection than his; they could form space skins at will from the materials of their own bodies. Tubo and his kind had no such powers. All the more honor to him then for inventing and constructing an improvement on their natural covering.

And it had been Tubo who had discovered, in the depths of his laboratory, that the world they inhabited was a dying world. He grimaced bitterly to himself even now at the thought.

He had hoped, after three former forced hegiras, that this planet would prove his last resting place. It almost had—but in a different sense. He had been the only one to escape. All the others—those of his own tribe and of the numerous other tribes who inhabited the planets with them—had perished. A wave of resentment coursed over his quiescent, rounded protoplasm.

Tubo had no organs of thought as we know them, no differentiation of functions. Thought was a process of the totality of him, so were the other functions of life; ingestion of food, evacuation of excreta, reproduction, sensory perceptions. There were no male and female in the world of Tubo, nor was there death except by violence or accident. Tubo reproduced by binary fission, a splitting along a longitudinal axis. Tubo was not one, he was a million different split personalities.

IT was all the fault of those other tribes, he thought resentfully. Why didn't they leave him and his own tribe alone to a planet? Why did they persist in following, in colonizing where they colonized? Tubo's tribe ordinarily managed a peaceful existence.

True, the planet would sometimes cease its aimless, incalculable movements and remain quiescent in space. But that did not matter. Only once had a world succumbed into the frigidity of death because of them.

In all other cases it had been the fault of the crowding tribes who followed them, who ate and drank voraciously of the life-giving intra-planetary fluids, and exhausted the wealth of natural resources within an incredibly short time.

He would never forget the world he had just quitted. Just as he was comfortably settled, and his laboratory set up according to his satisfaction, he recognized the symptoms of a dying world. He had warned the others; they had not heeded him. He had barely time enough to inclose himself in his space suit, and hurl himself out of the current of the underground river into the swift gaseous exhalations that jerked with spasmodic regularity through the chief outer orifice of the dying world.

He was ejected just in time. A sudden swirling upheaval of subterranean gas thrust him violently into space, spinning and bobbing. Looking back, Tubo saw the elongated planet ripple all over its flexible surface; then it was immobile. The orifice remained a gaping hole, moveless and still. The subterranean explosions had ceased. No gas puffed out. The planet was dead.

Tubo shuddered with the narrowness of his escape. His comrades, friends, all the inhabitants who had lived and jostled with him over a hundred splitting generations, were doomed to a horrible, hopeless death. Imprisoned within the bowels of the dead world, while the heat of subterranean fires ebbed into destroying frigidity.

The broad, warm, life-giving rivers slowly congealed and held their struggling forms in a movelessness from which there was no escape, until they strangled and died in dreadful, bursting agonies.

Tubo was no sentimentalist. None of his kind was. He accepted life and death, especially the death of others. But it was striking closer and closer to himself each time. That last escape was too much by a hair's breadth for comfort. He was a scientist. Surely there must be some way—— He stopped himself grimly. Time enough for that. Meanwhile he was in peril of immediate dissolution. The glow was beating in upon him, piercing his shrinking body with strange agonies. In another space-minute, he calculated feebly——

Ah! A planet swarmed huge upon his vision. It was moving rapidly, rushing through the universe in an inscrutable orbit. If only—— A space flow swooped upon him, caught him in its vast force-thrust. It hurled him directly toward the lunging world, directly toward a gaping crater which led into the interior, where food, security and life beckoned to him.

Exultation beat through his rapidly desiccating frame, renewed his energies. Closer, closer, he was hurried, still in the clutch of the blessed current. Now he was at the very mouth of the orifice. It yawned before him with inviting blackness. Panic seized him then—panic and a sense of helpless suffocation. What if he were an instant too soon, an instant too late!

The planets of the universe were all volcanic in nature. At regular intervals the interior fires belched forth a hot effluvia of gases. An eruption now would send him careening back into outer space, tossing and bobbing. With awful clarity Tubo knew that this was his last chance. If he missed this world, he would die before chance could throw him in the path of another.

A faint eddy crossed the space current on whose bosom he was being carried. It came from the rapidly nearing planet. Nausea drenched his protoplasmic formlessness. Was it but the premonitory prelude to a geysering eruption, or was it—— A back eddy sucked at him, swept him out of the clutches of illimitable space, pulled him tumbling and twisting into the maw of a Stygian darkness.

Down, down the unfathomable gulf he dropped, like a plummet, past strange caverns and spongy traps, where lurked weird monsters whose single gulp was death, past them in safety, down, ever down, the wind of his flight whistling through his space skin, until, in a pale phosphorescent glow, he found himself hurtling through a series of hollow caverns, whose dark red, spongy walls glistened with a dripping dew.

FRANTICALLY he tried to stop himself. This was the ideal place for settlement; this was a home as good as the one he had just hurriedly quitted. Nowhere else within the recesses of this vast interior world would he find existence so secure, so comfortable.

Furthermore, during the long, terrible space journey, certain ideas had pulsed with gathering force through his being; plans had matured which he wished to put into effect at once.

Yet the beckoning red walls slipped upward with hopeless speed. In another instant the caverns would end, and he would find himself immersed in the subterranean river which would sweep him to remoter and more barren reaches. He bumped! Breathless eternity! Would he tear loose from this last hold, or would the friction between the soft pulp of the cavern wall and the smooth slipperiness of his space skin bring him to a halt? He cursed now the protective covering that had brought him safely through his interplanetary flight. His naked being, viscid and semi-flowing, would have perished long before this caught hold.

He quivered, swung aimlessly. The least shudder, and—— Ah! His swings grew shorter. The spongy wall enfolded him lovingly. He was being embedded. He was safe; he was home! He breathed a sigh of thankfulness.

An all-wise, omnipotent Being had guided him safely, had peopled the frightening depths of space with innumerable worlds, equipped to the last detail with all the necessities for life and continued existence. Not that he hadn't heard rumors of strange planets that roamed the galactic universe, to all outward seeming like these kindly worlds, whose interiors nevertheless harbored strange, poisonous compounds, whose mysterious depths meant instant death. He, Tubo, had been fortunate thus far——

He set to work at once. He uncoiled his huddled round form, straightened it to the rod-like length which was his normal shape. He pushed with all his strength against the resilient membrane of the space skin. It gave, punctured. With a gasp of thanksgiving he wriggled out, attached himself with a shuddering ecstasy to the soft, dripping cavern wall! It felt good. The red dew sucked into his naked form, swelled him with a satisfying feeling of fruition.

"Hello!" The vibration impacted on his delicate protoplasm, wriggled him around toward the speaker. He was not alone, naturally. Not a planet in the universe but was tenanted with swarms of beings—members of his own race, members of other races.

The person who had greeted him swung chattily from a nearby wall. He was not of his tribe; he was round and smooth and smaller. "A stranger here?" the round one asked in friendly fashion.

"Yes," Tubo told him. "My old world died. I've just come in from space."

"I know," the other remarked sympathetically. "It's happened to me, too Just as I get all set and comfortable, something always goes wrong with my planet, and I've got to get out in a hurry. I just came here myself a short time ago. Haven't even had a chance to split up yet. But here, we haven't introduced ourselves. My name's Strepton."

"Mine's Tubo," the scientist said. "Now look——"

But a change was taking place in Strepton. The round sphere of him commenced to quiver all over. The clear luminescence of his body clouded. The vibrations increased. Then slowly, at the poles of his being, two tiny indentations appeared, sank deeper and deeper until Tubo's new friend was attenuated in the middle like an hourglass.

Tubo never knew what made him jerk his rod-like form convulsively forward just then. Perhaps it was the inordinate keenness to vibration that had set him apart and made him greater than his fellows. But it saved his life.

For the oval white monster who had pounced out of the spongy recess in which it had been lurking, missed him by a millimicron. Its huge, voracious bulk slithered on, unable to stop itself, straight for the splitting, reproducing body of Strepton.

Tubo cried out a hoarse warning, knowing even as he did that it was useless. Those in the throes of parturition were particularly helpless, unable to duck or dodge or squirm to safety.

Already the white mass of the slithering monster was arching itself over the hapless Strepton, avid to ingest this toothsome morsel into its slimy depths.

A last shudder coursed through the fissuring being. There was a rending sound, and Strepton broke literally into two. The white beast gulped. Strepton the Second disappeared with a horrible sucking sound. The monster slavered and rippled with glutted satisfaction, and kept on sliding down the trickle of red dew. In another second he was out of sight and the slobbering sound of his digestion mercifully quenched.

TUBO stared after him with trembling anger. The planets held their perils as well as the reaches of outer space. Give him time, a well-equipped laboratory, and he would bring certain experiments on which he had already embarked to fruition. Then——

The idle, chatty voice of Strepton broke in on his grim resentment. "Almost had me that time, didn't he?"

Tubo swung around. "Yes," he said slowly, "but he got your child."

Strepton gave a ripple-like shrug. "That's life," he said easily. "Besides," he added humorously, "give me time and I'll have a thousand more."

Tubo had no chance to answer, for the inhabitants of his new world came swarming to bid him welcome. They surrounded him, and chattered and squeaked and wriggled—uncounted millions of them. Fellow tribesmen, long and rodlike; round orbs like Strepton, in a thronging profusion of species; and certain pallid, slinking, corkscrewing creatures from whom the others moved gingerly away. Tubo himself could not suppress a shudder at the sight of one pallid stranger who almost brushed up against him.

"Stinking outlaw!" he muttered angrily to himself. There was something gruesomely pale and lusterless about them. Of all the forms of life who peopled the universe they alone slunk and squirmed their thread-like forms furtively along, shunning the friendly gregariousness of the others.

The pallid shape spiralled rapidly near him. "You needn't make remarks about me," he squeaked. "Spira has his own tribe waiting for him." With that he wriggled toward a colony of corkscrew shapes, hanging in a ghastly cluster on a neighboring wall.

Tubo frowned, but the clamor of greeting swarmed around and over him. His fame had preceded him. There were those in this world whom he had met inside other planets, and who had seen his work. They murmured awed, broken phrases to the other inhabitants, until, from the farthermost nooks and crannies of the world, they flocked to see the famous scientist.

Tubo was almost crushed under the clambering throngs of his well-wishers. Like true sightseers they remained, refusing to give way to late, hurrying throngs as the news continued to spread. They gulped the thin streams of red fluid dry; they burrowed into the soft red walls and ate and ate and ate to repletion; they paused only to split in a hundred different ways and to thrust their new-born offspring upon the., spongy food of the caverns. The din was frightful; the crush unendurable. And all the while the pallid outlaws hung to a single spot, burrowing deeper and deeper with a certain terrible ferocity.

A clamor arose suddenly within the outer pressing ranks—a sound compacted of terror. Tubo, half-crushed, dazed under the weight of his well-wishers, knew that sound for what it was. A cold anger burned through him. Fools! Heedless, stupid fools, all of them! Their silly clamor and crowding and jostling had brought the avenging monsters of the planet upon them.

Already he could hear the peculiar, horrible slimy sound with which they engulfed their prey. Already the screams of the victims smote his quivering form, sent panic waves through the close-pressing hordes of his fellows. They surged blindly in all directions, seeking safety in tiny nooks and crannies.

Far off, bearing down upon them with steamy exhalations, was a flooding river. It was hot; hot with the forced temperature of the distant, interior fires. And on its flowing crest, rearing themselves avidly in glaring expectation, were myriads of white oval monsters. So many were they that the normal red-colored river was a pasty white—almost like Spira and his kind.

There was not a moment to be lost. Scattered as they were, the frightened multitude was an easy prey. The appetite of the white beasts was insatiable. They would hunt and harry and gobble until only the most securely hidden would escape. The unnatural warmth of the river that carried them in its bosom lent them added ferocity, while it weakened the delicate protoplasmic tissues of their victims.

IN a flash Tubo saw the answer to the problems that had been puzzling him, on which he had worked unavailingly before his former world had expired. But first there were other more immediate and pressing things to be done. His very life was at stake.

His long, slender form vibrated rapidly. The dear call of his kind rippled outward in a widening wave, impinged on the receptive protoplasm of his fellows.

"Stop where you are!" he shouted. "In flight there is death for all of us. We outnumber the enemy a hundred to one. Safety lies only in swift attack. Forward!"

The panicky hordes stopped irresolutely, wavered, then caught the contagion of his voice. A brave recklessness invaded their beings, filled them with strange new, satisfying ardors. Formerly they had always fled from the dread, engulfing monsters, trusting to the multiplying rapidity of their reproduction for the continuance of the species, but never had they dared to stand and fight. But now they had found a leader, and it was good.

The multitudes stopped, formed in close, solid ranks. Only the outlaw, pallid corkscrews, led by Spira, remained apart. They burrowed more and more rapidly, until they were completely inclosed and out of the noise of battle.

The white-dotted flood roared down upon the tribes. The white beasts reared themselves joyously and fell with slobbering, sucking sounds upon the massed ranks. Here was food in abundance, such as they had never seen before. Fear was not in their bodies; they had no organs for such neuroses.

But Tubo was already threading the phalanxes of the tribes with strong, whipping movements. "Forward!" he shouted and swam boldly into the swarming flood. Behind him grew a mighty yell, as the tribes, inflamed by the sight of their leader, hurled themselves after him.

The battle was on!

The enemy reared and swept into their slimy folds thousands of the struggling tribesmen. Screaming beings struggled hopelessly inside their fearsome maws and dissolved into fluid extinction before the horrified gaze of their fellows. The slaughter was terrific!

For a moment the ranks wavered. There was no fighting these terrible creatures. Then Tubo's voice rose strong and clear again. "Smother them with your numbers! It is your only chance!"

With a savage roar of vibrations they smashed forward. A hundred clung to each thrashing beast. Five, ten, fifteen, were swept with hideous screamings into the fatal bodies, but others took their places. The white monsters twisted and writhed and engulfed with sucking movements. But the tribesmen clung to their enemies with the tenacity of leeches. Slower and slower grew the thrashings, the convulsive jerkings, until, with a final shudder, the dread things lay limp and silent underneath their swarming weight.

The terrible planetary monsters had been defeated. For the first time in the history of the universe they had succumbed to a direct onslaught. The few remaining of the horde broke ranks, and swam hastily back against the untainted redness of the underground river, seeking their lairs in the caverns of the chalk-white cliffs, to lick their wounds and gain recruits from the ever-spawning rock.

The tribes went wild with joy. Uncounted thousands had died in the tremendous conflict. But that did not matter. The dead were dead, and those alive could now split and split to their heart's content, bearing innumerable progeny into this habitation that was now almost miraculously freed of the lurking menace. In an unbelievably short time they would swarm in such reckless profusion as no planet had ever witnessed before.

But Tubo was not exulting. A frowning quiver passed over his naked being. Strepton, pulsing rapidly with the strain of his recent exertions, and the near approach of a new parturition, asked anxiously: "Have you been hurt, Tubo?"

The scientist wriggled a negative. "It is not that. But have you felt, Strepton, how cold it is becoming?"

Strepton shivered suddenly. "B-rrr!

Yes! I hadn't noticed it before. It was so hot only a moment ago."

"Exactly. The interior fires have cooled. The white monsters stirred them to fever heat to overcome us. When that failed, the fires somehow quenched. Strepton," he went on impressively, "our planet is dying."

The little round fellow rolled over with fright. "Impossible!" he wailed. "I just got here. I couldn't make another space journey now. I'd die. I'd be——"

BUT Tubo was not listening to his complaints. He was thinking, thinking as hard and as fast as he had ever done in all his life. He, too, would not so soon be able to withstand the perils and strains of the inimical universe outside. It was definitely colder now.

The joyous multitudes had felt it, too. Binary fissions remained unfinished, as life processes slowed. The delicate protoplasm of their bodies quivered and jelled. Motility became a difficult, painful process. Anguish quivered on all their straining forms. Even the most stupid knew that the planet had abruptly slowed its forward motion, that somehow it had become motionless, quiescent, fixed in space. The planet was dying, and they——

Tubo saw everything. The red sponginess of the caverns, ordinarily a strong, regular expansion and contraction, subject to definite, calculable laws, now fluttered irregularly. The vibrations were slowing, becoming feebler. The red dew on which they fed was a trickle where it had been a flood, and a new stream burst out of the walls—thick, viscid, yellow, slimy. A poisonous exudation whose appearance was a ghastly horror.

The scientist wriggled sharply. "I have it, Strepton," he cried in high excitement.

"What?" asked his friend stupidly.

"The solution to our troubles. We've been fools all our lives—all the lives of the uncounted generations before us. We are greedy. A world, the universe itself, was a thing to be exploited as rapidly as possible, to be sucked dry of all its natural resources. We had enemies, it is true—the fierce white monsters. They ate us and gobbled us and held us down. We had only one weapon against them, that is, up till now. Our fecundity!

"We overwhelmed them by sheer procreation. If we split into new personalities faster than they could seek us out and destroy us, we exulted. We had been victorious. Blind fools that we were! Thereby we destroyed ourselves. Strepton, the white monsters were not our enemies; they were our best friends!"

The translucence of Strepton's roundness clouded. "Have you gone mad?" he exclaimed angrily. "If the others should hear you——"

"They shall!" Tubo cried. His surface was luminous with rapid thought. "I've found the secret. Listen, all of you," he raised his voice.

The moaning died. The tight-packed multitudes, stiff with approaching dissolution, looked fearfully toward the rod-like scientist.

Tubo was their leader. He had defeated the unconquerable planetary beasts. Perhaps he could do something now. It was terribly cold. The hot inner core of the world seemed to have quenched. The slow pulsations of the cavern walls were the merest quiver now. They were trapped in an expiring world.

"I have discovered the secret," Tubo shouted, "the scientific secret of the universe. It is balance! Our fortunes, our very lives, are inextricably bound up with the planets we inhabit. As long as we are sensible and moderate, the worlds of space maintain their inner fires, the red rivers flow with nutriment, the cavern walls provide us food and comfortable shelter. But once we become greedy and tear recklessly at the profusion of their natural resources, once we blindly and without thought spawn innumerable progeny, what happens? The planets cool, they expire, and we in our folly with them."

He paused, and looked over the stilled, breathless multitudes. "I hesitate to say this—it is only an analogy, you understand—but it is almost as though the senseless worlds of the universe, with their volcanic inner fires and regular eruptions, their caverns and swift flowing rivers, have a strange, formless, mineral life of their own. They can bear so much of us and no more. Crowd them to recklessness and they die of our profusion, even as we——"

A snicker interrupted him. As one the taut tribesmen turned to the sound of the scoffer. It was Spira, thrusting his pallid corkscrew shape out of the wall in which he had been comfortably embedded.

"Ho! Ho!" he snorted. "A philosopher, a spinner of moonshine. The next thing he'll be telling us that we're just parasites on the bodies of these mythical planet creatures of his—that their life is more important to the universe than ours."

"You shut up, Spira," Tubo cried, outraged, "and don't put your own sacrilegious thoughts in my mouth." He reared his rod-like body proudly.

"We tribesmen are the ultimate creations of the universe. We are the owners and inheritors thereof. The planets were formed by an all-wise Being for our maintenance and enjoyment. We possess the power of thought; we are the finest flower of existence. It is silly to think that evolution could have produced anything superior to us.

"I told you it was merely a tentative analogy; that the planets might—abstractly, you understand—possess a modicum of queer mineral existence of their own. But our time is getting short: it is getting colder and colder. Just now we have upset the balance of things, more definitely than ever before. We defeated the white beasts. We have crowded and spawned in tremendous profusion. As a result the planet has become a dying world."

"What's the answer then?" Strepton queried.

Tubo took a deep breath. "This! An end to our reckless, wasteful methods. An end to the rapid destruction of natural resources. A reestablishment of certain checks and balances which we destroyed by defeating the planetary monsters. They evidently had their niche in the scheme of things. They seemed our most deadly enemies; they killed, it is true, individuals of us, but by keeping our numbers in bounds they unwittingly maintained the delicate balance of nature, and in the larger sense, were our benefactors."

A LOW growl went up from his auditors. From time immemorial they had known the terrible beasts as the ogres of their existence, and now this Tubo came along and hailed them as brothers. It was ridiculous; more, it was——

"I suppose," squeaked Spira sarcastically, "we'll send our new friends a letter of invitation to come and munch on us. And apologies, too, for having dared assault their mightinesses."

Tubo checked the rising ripple of laughter with a blaze of quivering luminescence. "You won't have to apologize, Spira," he said pointedly. "While the other tribes were fighting and dying, you and your cowardly kind were safe ensconced in your hide-out." The pallid one wilted under the roar of acquiescence. With scared celerity, he burrowed back into the walls.

The scientist went on. "We must act, and at once. It may be too late even now. Don't worry about the planetary monsters. They fit somehow into the scheme of things, and we must let them live unharmed. But I don't intend permitting them to prey on us as of old. In the laboratory on my former world I evolved a defense against their depredations—a fluid which I can manufacture in huge quantities from the minerals of this planet. We'll pour it into the rivers and thus spread it to every corner of the world. It does not kill the beasts, but it renders them harmless; deprives them of their strength."

"But if you remove what you have called a salutary check upon us"—Strepton wrinkled his roundness in expostulation—"it will only make things worse."

"Not at all," Tubo answered calmly. "I am proposing a planned economy, a conservation of our natural resources, an expert balancing of forces—birth control, a new deal!"

"A new deal!" The phrase whispered from one to the other, grew from a whisper to a murmur, from a murmur to a torrential roar. It had such a satisfying, mouth-filling sound; it meant all things to all tribesmen; it held a content of vague, large promises that were difficult to pin down, and therefore all the more glamorous. Besides, the cold was creeping into their very vitals. The world was definitely dying, and only a fortunate few of all their number would be able to escape into the soul-searing reaches of outer space. Fewer still would find a new world in time. They had nothing to lose.

So it was that with hardly a dissenting vote the plan was adopted and Tubo acclaimed as the first dictator and coordinator. Spira and his brethren remained cannily out of sight.

Tubo organized things at once. Time was precious. He appointed Strepton his lieutenant. The tribes were counted and separated into companies. Each was given a definite task. The cold was creeping up on them, slowing their movements, freezing their delicate bodies. The planet had been fixed in one spot in space for an unconscionably long time. The volcanic explosions were barely perceptible.

But only to Strepton would Tubo confide his fears. To the others he was a driving dynamo of energy, a fount of radiating enthusiasm. He infected them with his vigor. In double-quick time a laboratory was set up, and a corps of willing, though inexpert assistants placed at his disposal. The chemical fluid was soon being manufactured in large quantities, and dumped into the languidly flowing rivers.

The next step was to put a stop to all procreation for a fixed period of time. Tubo worked feverishly at the problem. Finally it was solved. He found that the involuntary urge to binary fission was a function of the saline content of the rivers and of the amount of food ingested per unit of time.

The second half of the problem was easily attended to. Food was rationed out in scientifically calculated portions.

But the first was not so easy. It was only after Herculean labors that Tubo evolved an apparatus which extracted the reproduction-accelerating salt from the mighty rivers in sufficient quantities.

Then there was the task of getting rid of the glittering stores of crystals.

Tubo finally solved this seemingly insuperable problem by eliminating them through the numerous fissures and tiny tunnels that led to the outer surface of the planet. There it was left in huge, caked mountains.

The third step was to scatter the tribes to assigned habitations in the planet. Tubo had noted that whenever they swarmed in huge throngs as they did now, it played havoc with the secret internal economy of the world. Accordingly he had scouts map the entire interior of the world, bring him careful estimates of resources, mineral deposits, growths of food, navigable waterways, climate, ease of communication, etc.

Then, with this data on hand, and a knowledge of the peculiar requirements of each tribe and its characteristics, he was able to assign it to a suitable territory. Here he ran into difficulties.

For individual equations were involved. There were murmurs of autocracy, protests against particular assignments, cries of favoritism.

But Tubo crackled out his orders, unbending, harsh with strain. In the end he won. For the cold was a bitter ally. Already some of the weaker and more delicately nurtured had succumbed.

Blind obedience was their last chance of survival.

THEN Tubo called for volunteers from these tribes who could at will produce membranous space suits. Volunteers to wriggle their way to the surface of the dying planet, to cast themselves into the destructive radiations of outer space, and attempt their tortuous way to the other worlds of the system.

"But why?" Strepton, his lieutenant asked, puzzled.

"So that my work may not die," Tubo answered, exalted. "It is a question whether it is not too late to save our own world. The space volunteers will bring the tidings of my plan, of the technique I have evolved, to all the universe. They must organize even as we have fumblingly done, with more of leisure, with improved equipment. The new deal must go on, even though we as individuals die. The universe must be made into a safe, secure place for our people, with every world an ordered, flourishing economy, where chance and sudden death shall have been totally eliminated."

Strepton stared at him with awed admiration. It was a dazzling vision. "But why," he asked hesitatingly, "don't you go yourself? You have the space suit you invented. The chances here of survival, you admit, are slim. Why not escape while you have the chance?"

Tubo turned away. "My place is with my people," he said abruptly.

The volunteers were finally trained, sent on their hazardous missions. Others went, too, pallid with fear, forced out by numerous assisting shoves—Spira and his wretched tribe of outlaws.

Strepton shook his head. "They'll make trouble," he warned sagely. "You should have kept them here under your eye."

But Tubo smiled secretly and said nothing. He knew that Spira's tribe could not survive the inimical radiations of space. They shifted from world to world only on chance, occasional collisions between the planets. Tubo was not a sentimentalist, you see.

Now came a fearful period. The cold seemed to be getting more bitter, the streams grew more and more sluggish.

The tribesmen were dying in increasing numbers. The living could hardly crawl about their business. Tubo shut himself up in his laboratory, and gave way to despair. Had all his efforts been in vain? There was nothing else he could do.

Once Strepton crept slowly in to report a strange phenomenon. The barely moving red rivers had suddenly overflowed their banks—an inundation. "But the strangest thing of all," he reported in a queer, excited voice, "is the character of the new flood. It's a colorless liquid, and it's full of dead bodies. The dead bodies of our people! It's all over with us."

Tubo galvanized into action. He lashed out of the laboratory, stood on the banks of the torrential flood. Strepton had told the truth. Each wave cast up at his feet its bloated, sinister cargo. Rod-like people of his own tribe, round fellows like Strepton, thousands on thousands of them.

Strepton said in a hushed, miserable voice. "The world is dead. These are our people from the outlying districts."

Tubo bent over, examined them closely. When he straightened, there was a strained look on him. "They are not our people," he stated positively. "These are strangers from other planets, and they've been dead a long time."

"But how——" commenced Strepton, gasping.

"I don't know," Tubo cut him short. It was unbelievable, yet there was the evidence. The dead beings continued to wash through the subterranean channels. The tribesmen watched them with superstitious, fearful eyes. It was a judgment of the Almighty upon them, they whispered, for having hearkened to the blasphemous proposals of Tubo. He was flying in the face of nature, of things-as-they-are-and-always-would-be. This was the retribution.

But Tubo locked himself up in his laboratory and did not listen. This weird irruption was at present insoluble, yet he believed that it was in accordance with definite natural laws. Later, if things worked out, he would apply himself to the problem. If they didn't—he shrugged all over—it wouldn't matter either way.

The cold seemed now at a standstill. The rivers barely flowed. The inundation had subsided. The dead bodies were beginning to stink. The walls to which his laboratory was attached hardly vibrated. It took delicate instruments to discern the rate of expansion and contraction. His viscous, motile jelly was hardening. Death was not far off.

Then, with hopelessness creeping over him, he turned a lackluster form to his instruments. He quivered. Was it but the illusion of approaching death? The temperature filament. It showed a rise! A slight rise, it is true, but a definite, perceptible up-grade, nevertheless. Life surged through him again. Feverishly he examined his other instruments. The liquid-flow cilia. An increase in speed. The pressure bellows. The walls were heaving at a more regular rate, and with greater force.

Tubo flung himself outside. He shouted in stentorian tones. The colony of his cavern remained moveless, dulled in apathy. Then, as the purport of his exultant message penetrated their half-dead beings, they squirmed toward him, lifted themselves eagerly.

What was that? The dying planet was functioning again? Was it possible? Had Tubo really won through? Something rumbled and rolled echoing through all the caverns and subterranean rivers. A belch of hot, eruptive gases. The planet quivered; it moved. Once more it turned and heaved in space, after long quiescence.

A shout sprang from the multitude, was repeated and reechoed in a wide, expanding wave until not a colony in the remotest parts of the world but knew the glad news.

They were saved! And Tubo was their savior! Tubo, mightiest scientist since the universe began! Tubo, immortal dictator to a grateful people!

DR. TRUESDALE closed the door softly and carefully behind him, then capered and whooped.

"It's worked, Patterson, it's worked!" He was skinny and bald, and his eyes glittered behind thick lenses.

Eric Patterson, bacteriologist in the Madison Hospital, lifted his eyes from the microscope through which he was peering. "Eh, what's that?" he muttered vaguely. "What worked?"

"The serum, you fool!" Dr. Truesdale exploded. He skipped about like an elderly faun. "I'm rich; I'm famous now! The universal serum—Truesdale's serum—for all diseases. One injection and——"

"Tone down a bit," Patterson advised. "And tell me what happened to give you delusions of grandeur."

Truesdale sputtered: "Why, you insolent young puppy, you——" Then he laughed. "Come and see for yourself. You know the case in Room 13?" Patterson nodded. "Sure," he said bitterly. "I've just finished looking at a specimen of his blood. He's got the bugs of everything but the bubonic plague in his system. Swarms of tubercle bacilli, streptococci galore, and a lovely little colony of treponema pallida, the spirochetes of syphilis. It's a wonder he's lived this long, even in a coma. He should be dead by now."

"Dead nothing, you idiot!" Truesdale shouted. "He's alive, and not only alive and turning in his bed, but actually asking for food!"

"What's that?" Patterson asked sharply. "You told me half an hour ago his temperature had fallen from 106 to 95 within minutes; that his heart barely fluttered. No man has ever come out of that alive."

"Well, this man has," Truesdale retorted. "You fellows in the hospital laughed at my serum, wouldn't give it a chance. Well, I've showed you. He was as good as dead, anyway, so I sneaked him a dose while the chief was out. For an hour it was touch and go. Then he snapped out of it. Look at him."

Patterson looked. There was no question about it. The patient who by all the rules of medicine should have been ready for the slab was peevishly twisting his scrawny frame and babbling about steaks and he-man's food.

"Take a sample of his blood now," the doctor crowed.

Once more in the privacy of the laboratory, Patterson bent over his slides. When he arose, there was a queer look in his eyes.

"Truesdale," he said shakily, "I don't understand it. I've got scads of bugs under there as lively and active as you please. Every pathogenic variety you could think of. No," he interrupted himself, "there is one missing. The treponema pallida have disappeared, been wiped out. How in Hades that chap in there is not only alive, but with all the symptoms of recovery, beats me."

Truesdale was taken aback, but only momentarily. "What's the difference what bugs he's got in his system?" he chuckled. "He's cured, isn't he?"

And the patient was cured. A conference of grave and reverend doctors pronounced him as such; the man himself was positive of it. Yet his blood still swarmed with pathogenic bacteria.

Because it could do no harm, Truesdale's serum was tried on others in the hospital. A few cases unaccountably died, but the vast majority within a day showed unmistakable improvement. "Cause and effect," muttered Patterson skeptically.

But he kept his thoughts to himself. Even when it was noted that the geographical factor had a great deal to do with the efficacy of the serum. Only as it was given in slowly widening circles from the hospital did it work. And there were remarkable cures in individuals within the circles, individuals to whom the serum had not been administered. As if, Patterson thought, some influence were slowly radiating from the hospital, in ever-widening circles, evolving immunity to all diseases.

But, in the eyes of the world, and of most of the medical profession, Truesdale's serum was responsible. He became rich, famous, on the pinnacle of glory, almost overnight, while Patterson puzzled over his messy slides, his microscopes. The bugs were all there, in every specimen, yet somehow they had lost their capacity for harm.

He noted, too, the slight drop in blood salinity, the little deposits of free salt that evaporated on the skins of the recovering patients. And he also noted that the blood temperature of the human body had increased to a norm of 99.8 degrees. As though the entire human race had become slightly sick, slightly feverish, and thereby obtained an immunity against the further ravages of disease.

But there were no qualms, no misgivings, on the part of Truesdale and his henchmen. The serum was the cure-all; and he was the greatest benefactor the world had ever known. In the course of years, every one was inoculated with the serum, and gradually, sometimes after the use of the serum, sometimes in advance of it, the immunity spread over the earth. Every one was a little feverish, but no one died of disease. And the name of Doctor Truesdale went rocketing down the centuries, long after Patterson and his little doubts were dead and forgotten.

Even as the name of Tubo resounded in another and different universe.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.