RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, May 1938,

with "Island of the Individualists"

The man of the past, of the present, and of the

future meet the quintessence of selfishness.

THE stolen rocket ship winged swiftly over the shoreless sea. Within its slender hull three men peered down upon the moveless waters, faces haggard with hope deferred, eyes tense with a similar despair.

Sam Ward—man of the twentieth century—ducked his lean head toward the fuel tank, read the gauge for the hundredth time.

Beltan, Olgarch of Hispan, refused to turn his proud, aristocratic head. His sensitive fingers seemed engrossed with the controls. "Well, Sam," he asked quietly, "how much is there left?"

Kleon—the Greek who once had marched with Alexander the Great—did not even inquire. His Macedonian armor was tarnished from many suns and many rains, yet he clutched with still-fierce grip his keen-tipped javelin and battered shield. His sun-bright locks framed features clean-chiselled as on a medallion, his blue eyes swept the interminable wastes beneath.

Sam forced a grin to his cracked lips. "Less than there was ten minutes ago, Beltan," he replied, "and more than there will be ten minutes from now."

"Which means," remarked the Olgarch without a tremor, "that in ten minutes the fuel tank will be empty, and this rocket ship in which we fled from Harg will plunge headlong into the Pacific."

"Yes," said Sam.

Again there was a long silence, punctuated only by the soft roaring of the jets.

Kleon shaded his eyes, stared out at the dappled haze that seemed to stretch as far as the eye could see. "This is what comes of new-fangled inventions," he groaned. "At least when my trireme was driven from Nearchus' fleet by fierce storms, we hoisted sail and found our way to a land where the Cimmerians hailed me as Quetzal. But now we cleave the air, bound helplessly to a little tank of fiery liquid. It evaporates—and behold, we are no longer birds; instead, we emulate the fish of the sea. But—" he glanced sadly at his shield, at his rusted armor, "it is too long a way to swim."

"How far is it to land?" asked Beltan.

"As near as I can calculate," said Sam, "almost a thousand miles. Too far to swim, as friend Kleon has justly remarked."

The Greek shrugged. "I never did like the sea," he declared. "I prefer solid ground underfoot, where I can brace myself and charge the enemy with my good sword flashing. It is my fault. Had I not remarked about the sleeping Gymnosophists in the mountains of Tibet, this would never have happened."

"No more your fault than mine," Sam Ward told him warmly. "They were our last chance. We ranged over most of North America seeking evidences of other cities, other civilizations. Aside from Hispan we could find nothing. And always behind us, hemming us in, hunting us like rabbits, were the rocket hordes of Harg, headed by Vardu. Our only chance lay in escape across the Pacific, to find the sleepers who had given you the life-immobilizing formula."

"It is a pity that there was a leak in the tank," observed the Olgarch with calm indifference. "Otherwise we could have made it. As it is, I regret nothing. I have lived more completely this past six months with you two as comrades, than in all the prior years of purposeless luxury within the neutron walls of Hispan." He smiled reflectively. "A strange thing, our association. A Greek from the time of Alexander—an American from the twentieth century—and I, an Olgarch of Hispan, who once thought myself the proud apex of the ninety-eighth century. Nevertheless we——"

KLEON lifted his head; his straight, classic nose quivered. "Look!" he cried, and his voice sounded slightly cracked. "Look, my friends—yonder, to the left. There is a thicker haze upon the waters that——"

Sam jerked erect. His lean face tightened, his gray eyes stared unbelievingly. "Land!" he shouted. "An island where there should be no island. But of course! Eight thousand years is a long time in the Pacific. A volcanic eruption; a rising of the sea floor——"

He swung feverishly on the Olgarch. "Point the rocket's nose straight for it," he cried. "We are saved! Do you understand what I am saying, Beltan? We are saved!"

"Temporarily at least," Beltan amended quietly. Nothing ever ruffled his proud, aristocratic calm. "It seems like uninhabited land, and we have neither food nor means to leave again, once we come down. And remember, Vardu will hunt us relentlessly. His advance horde saw us wing out upon the ocean. They will follow."

Sam experienced a sudden sinking sensation in the pit of his stomach. The Olgarch was right. Already the steady roar of the rocket jets had given way to irregular sputterings. The tanks of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen were practically empty.

They were close enough now to view their alien haven with an attempt at detail. But a shimmering haze hid its surface from the view—a haze such as none of them had ever seen before.

The vast reaches of the ocean had cleared with the magical suddenness familiar to those who in all ages had sailed its magnificent bosom. The sun beat down with unobstructed glory, dazzled the blue surface into a burnished shield. Not the tiniest wisp of cloud fouled the expanse of sky and water.

But over the island—or what had seemed to be an island—an impalpable vagueness shimmered and danced. Its edges were confused and indeterminable, its domed obscurance a strange indefiniteness. Slight as gossamer, yet quenching the fierce heat of the sun—pulsing and vibrating with an inner life, yet neither refracting nor reflecting the beating blaze. The eye tried in vain to grasp its form and nature. It eluded the sight, it slid away in protean manifestations. Yet what lay underneath was as starkly invisible as though it were clad in many thicknesses of lead.

Kleon was a Greek of the Enlightenment, yet as he stared, ancient superstitions arose to trouble him. "By Zeus and Poseidon!" he cried in amaze, "these are but enchantments similar to those that the sorceress, Circe, employed. Let us not land, my comrades; let us rather go on."

"Easier said than done," Sam remarked dryly. "Listen to those rocket blasts. They're coughing their lungs out." Yet even Sam Ward, practical, coldly scientific, matter-of-fact, felt a queer tightening of his scalp at the sight of that shifting totality.

"What do you make of it, Beltan?" he asked anxiously as the slender craft hurled downward.

The Olgarch shook his tawny head. His eyes were troubled. "I had thought," he murmured, "that we of Hispan knew all things that were to be known. Even the fanatic science of Harg was no mystery to me. But this is something new—something beyond my knowledge. It is no mist, or novel refractions of layers of air. It seems impalpable, yet there is a sense of strength beyond that of stellene and neutron walls themselves. More, there comes up at me a strange impact—as if it held a queer sentience of its own. A withheld life that examines and weighs us in the balance even as we drop."

"I've had the same feeling," husked Kleon. "That is why I say——"

IT WAS too late. With a final gasping cough the rocket motors died. Beltan wrestled with the controls. Down, always down, in great, swinging circles, the ship sank like a wounded bird. The sea rushed up to meet them.

And the shimmering mist beneath!

Sam forced back a cry as they struck. There was nothing beneath—nothing that could be seen, that could be evaluated. In the distance, the moveless waves of the Pacific were hundreds of feet below.

There was nothing—yet the rocket ship shook in every stellene strut, swerved sideways, and slid along impenetrable nothingness. Down, down——

Beltan worked feverishly at the controls. Great globules of moisture beaded his brow. Kleon thrust vainly with heavy javelin at that along which they tumbled. Sam clung to the side as the craft tumbled and. fell.

Waves of force seemed to pluck at his brain. Mighty sluices of energy poured into his being, drained his veins of all volition, of all movement. The glittering mist swarmed over him, engulfed him. Keen lances probed his mind, sucked out his energy, flung him limp to the bottom of the hull. As in a daze he saw Kleon stagger from the rim, pitch moveless to his side. Dimly he heard the Olgarch's cry, saw the proud aristocrat struggle with the unseen influence, saw him stand upright, away from the controls, pitting his will against the immaterial shimmer that engulfed them all.

A moment Beltan stood, erect, battling with clenched teeth and white-drawn features, holding his own. Then, slowly but surely, he gave way. His tawny head bowed, his tall body arced away like a taut-strung bow, his eyes clouded and went blank.

Triumphantly the irresistible waves beat upon them, within the very fiber of their beings. Dimly, Sam felt keen sentience behind it all, probing, prying, searching——

Suddenly the rocket ship of Harg accelerated along the downward-curving mist, slid smoothly to a shuddering halt. The sheen of force-waves lifted, vanished. The plucking fingers within their brains ceased their restless prying. Strength surged back into their limbs. Astonished faces lifted from the hull. The three adventurers rose lithely to their feet. Once more they were masters of their wills, assured of the privacy of their brains.

"In the name of Castor and Pollux," swore the Greek, "what happened?"

"We are," said the Olgarch with tense calm, "in the presence of forces beyond any conceived of in Hispan."

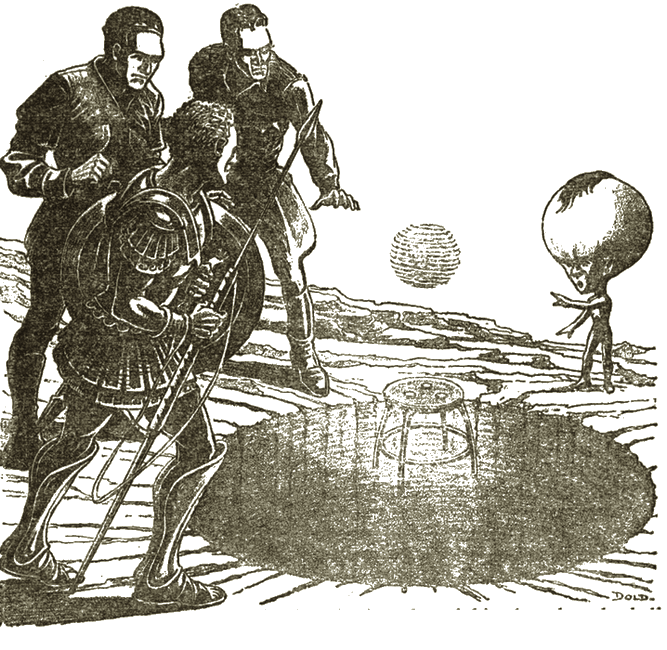

But Sam Ward, the practical, darted keen eyes around. "I see a man—a human being!" he said softly, and gripped his Colt hard.

THE man was seated on a cushioned mound, cross-legged, like the ancient fakirs of India. His body and limbs were shrunken and puny, and seemed unable to support the structure of his enormous head. From a spindle neck it rose, swelling upward like a top, from thin, small lips, a flattened nose, to colorless eyes turned introspectively inward, and a bulging, hairless forehead. Only a tiny tuft of hair—a scalplock—relieved the aridity of the ballooning skull.

He sat with great head resting on emaciated fingers. He seemed not to have seen his visitors, the differently modelled humans and their strange craft that had dropped upon him from the sky. He seemed unaware of all else in the universe but the ingrowing of his own contemplation.

"Bah!" snorted Kleon with a vast scorn. "Is he then the enchanter who inhabits this fantastic island? Why, I could break him in two with but a twist of my wrist."

"Don't try it, friend Kleon," warned Beltan. His gaze smoldered upon the oblivious creature. A strange respect crept unwillingly into his eyes. "Physical prowess is but an early stage of evolution. You typify that quite well. Sam Ward here represents the commingling of the mind and the brute. I had believed myself to be advanced in mental force. But here, before us———"

"You mean that this puny creature, who does not even know that we have intruded upon him, is superior to you?"

The Olgarch nodded his head. "He made me yield the very secrets of my existence," he answered simply, "of everything I had ever known or dreamt. Therefore——"

"Hey, there!" called Sam. "Who are you and what is this land?"

The seated man lifted his head slowly. He seemed to have awakened from a dream. His colorless eyes stared at his visitors. Sam reeled back. A wall of invisible force had struck him full in the face. It was like a physical blow.

"Sssh!" said the puny creature. His voice was rusty, halting, as though he had few occasions to use it. "You have disturbed my contemplation. I have lost the thread of my inner discourse."

Kleon, magnificently animal, looked down with open scorn at this defenseless, wretched apology for a human being. He had regained his usual composure, lost the first fright that had assailed him.

"Listen, old man," he said contemptuously, "we are strangers cast upon your desert island, in need of food and drink and shelter. Instead of mumbling nonsense at us, bestir yourself to hospitality."

The bulging head lifted slowly. The eyes veiled themselves. "Strangers?" he queried reflectively. "Not at all. You are Kleon, an Athenian, who dwelt in an unbelievably primitive world ten thousand years ago. With queer slavishness you followed a barbarous leader, hewing and slaying, into countries peopled with diverse races."

Kleon gasped. His particular god, the great Alexander, a barbarous leader? In his anger he forgot to be amazed. "How dare you—?" he started furiously.

The man ignored him, turned his veiled eyes to Beltan. "You," he said in halting phrases, "believe you are contemporaneous with me. But time is a function of thought, not of space and directive motion. Therefore I, Ens, who seemingly exist in the same time flow, actually am separated by many ages from you, Beltan, man of the ninety-eighth century, and denizen of the enclosed city of Hispan. It is true that you show evidences of an inner fumbling after the truth, but as yet it is but a blind groping."

The proud Olgarch said nothing. His handsome face betrayed no sign of his emotions.

CALMLY the large head twisted on its stem-like neck. "As for you, Sam Ward," he spoke, "you are a puzzle. You come from the twentieth century, a strange mixture of the unbelievably primitive and of dim aspirations. Kleon and Beltan are simple—pellucid—like their times. The mold was fixed—determined. But your age was a shifting complex. It was a fearsome stew in which the animal and the mental fought for mastery." His bulbous head swayed on its stem like an overgrown pod. "A bastard age, which even I, observing you, cannot wholly fathom."

"How in blazes do you know all this?" Sam exploded involuntarily.

Ens was no longer looking at them. His gaze was withdrawn, turned inward upon himself. He did not answer. He seemed to have forgotten their very existence. His shrunken body stiffened, his thin lips were closed.

Then slowly, even as the three adventurers stared, a queer shimmering haze moved outward in concentric waves, coalesced, deepened into a surrounding shell, cutting off the cross-legged man from their view.

Once more they were alone, next to their fuelless plane, on a barren, volcanic soil.

"Well, I'll be damned!" breathed Sam.

Kleon flung up his shield as if to guard himself, called on Pallas Athene for protection.

But Beltan said in a strange voice, "He explored our minds, our ages, found them valueless. Wherefore we no longer exist to him. He has returned to the contemplation of his own thoughts as the most important thing in all the universe."

"And that wall of force?" Sam demanded.

"The emanations of his thought."

"But," Kleon protested, "how can thought have physical being—texture?"

"Why not? Long ago it was determined that there was an electrical basis for thought. Some even went so far as to venture that it had an independent being of its own—that the universe itself was but the outer manifestation of the inner thought-structure. Here, on this barren island, there has been a curious evolution through the centuries. Ens and his predecessors, cut off even as Hispan and Harg from all contact with the rest of Earth, had disregarded the physical, the well-being of the body. Instead, they concentrated on the mind—upon the abstract contemplativeness of themselves and the inner universe. They developed powers of which even we in Hispan had no conception.

"Evidently Ens has discovered a method of projecting his thought waves, of interlacing them around himself in a web of force. Invisible—but without doubt more impenetrable than any material substance of which we have any knowledge. Within that shell, he is withdrawn from all outer distraction and interference, and able to pursue his absorbing abstractions in utter peace." Sam whistled. "At Harg I complained that their science was too practical, too immediate in its purposes. Here this strange being who calls himself Ens has gone to the opposite extreme. He just sits and sits and contemplates his own navel in complete satisfaction."

The Olgarch smiled. "Evolution plays queer tricks. This is one of them. Yet I have no doubt that if aroused, Ens and his immaterial thought could prove more powerful than all the legions of Harg."

Sam started. "Say, that's an idea," he exclaimed. "I wonder——"

BUT Kleon was growing impatient. "Are we going to starve in fruitless discussion," he complained, "or are we going to find some way of getting off this meaningless island?"

The American stopped. "As always, you are right, friend Kleon," he grinned. "I'm getting hungry myself, and there isn't a morsel of food in the plane." They looked around them for the first time, then. The island was of volcanic origin, and about ten miles across. There was not a tree, not a blade of grass, not a human habitation or sign of animal life. A more desolate, wasted surface could not be found outside the bleaknesses of the moon. Overhead, the sky was wholly obscured, secreted from view by the strange, shifting patterns of impalpable waves.

"Does this Ens, who so most discourteously withdrew himself from our sight, inhabit this desert by himself?" the Greek demanded. "If so, then we are indeed in parlous straits."

Sam squinted upward at the doming interlacements of thought. "It looks that way," he murmured. "Yet he's a wizard to have made all those emanations alone."

"By Ares, God of War," exploded Kleon. "I shall make him come out of his shell and help us. I do not believe in this metaphysical nonsense that stems from Plato. I myself am rather a disciple of the great Aristotle."

"Here, don't do that," Beltan cried. But already the Greek had run full tilt against the shining haze. His short broadsword was in his hand. His shield was before him in war-like pose. His javelin, slung by a thong over his back, rattled against the heavy armor. A magnificent fighting machine, unsurpassed in the history of the world! Racing irresistibly against an immaterial shimmer, a mere projection from the mind of a puny, shrunken man with over-large head.

The blade flashed in the air, descended with powerful, hacking stroke. It hewed against the pale web of thought. The keen steel stopped in midstroke as though it had hit a neutron wall. Sparks flamed outward in a dazzling spray. The weapon wrenched violently from his hand, flew ten paces away. Kleon catapulted backward in a sprawling heap.

Sam swore furiously, tugged at his Colt revolver. Without quite knowing what he did, his finger contracted on the trigger. His friend, comrade of incredible adventures, had been hurt—killed perhaps.

The steel-jacketed bullet crashed from the orifice, sped true to its mark. Sam gaped foolishly. The missile mushroomed against the invisible surface in a flare of blinding light, clunked solidly to the ground in a flattened disk.

Before he could shoot again, Beltan had him by the arm. The Olgarch's face was serious, concerned. "You are as bad as the Greek," he groaned. "A creature of impulses—of disastrous emotions. Our puny weapons are no match for the mighty thought of Ens. He could kill us with the merest flicker of his mind."

Kleon stumbled slowly to his feet. He stared incredulously at his still-tingling hand, picked up his stricken sword. A shadow of dawning awe overspread his haughty features. "By Zeus," he husked, "I had never dreamt my sword could be thus turned."

Sam looked down at his still-smoking Colt with a sheepish grin. "It seems," he observed, "that Ens does not wish to be disturbed."

"There are others on this island," Beltan said suddenly.

"Where?" chorused his friends.

The Olgarch pointed. "A goodly number. See those faint iridescent glows scattered over the ground—so faint they are hardly discernible? Members of the same race as Ens, perhaps, each enclosed in his own sphere of thought."

"The ultimate in privacy," Sam remarked. "I hope they're not all as standoffish as Ens. Let's get started. Now that Kleon brought up the subject, I'm very hungry."

THEIR feet crunched over hard lava and crumbly pumice. They were tired and hungry and in desperate straits. Somewhere over the Pacific, even now, were the hordes of Harg. Each fanatic soldier enclosed in an individual stellene rocket tube, bearing the stellene-tipped rod that flamed blasting disintegration, was searching for his prey, for new cities, new peoples to conquer on this Earth heretofore thought entirely desolate. A Totalitarian State, aflame with the lust for conquest, had poured out its men from their underground city after the escape of the three men from alien times. Under their new leader, Vardu, they were ruthless, vengeful.

"Here we are," said Kleon gloomily, halting before a swirl of interlocked vibrations. "Another one, secreted within his cocoon. How do we get him out?"

They called, they waved their hands, they shouted, they gesticulated. They even danced in frantic effort to pierce the swirling maze. But the shimmer did not change its tints, or open up to reveal who or what lay within.

At length Sam called a halt, exhausted. His lean face etched with angry bitterness. "Nice people, these intellectualized beings of the future," he panted heavily. "The very essence of hospitality. Me, I'd prefer a little less brain power and a little more of warm, human emotion."

"Evolution has its price, it seems," Beltan said calmly. "We of Hispan have found that out. So, too, have the hordes of Harg. A single faculty or group of faculties expands—but only at the expense of others. The latter—laggard in the race, or found to be useless—tend to atrophy."

"I'm still hungry," Kleon interposed.

"Beware the Greeks whose stomachs are empty," murmured Sam. "Let's try another of these birds."

The third and fourth and fifth of the enswathed denizens of the island paid no heed to their cries and entreaties. Even when Kleon, in an access of desperation, daringly flung his javelin at the exasperating shimmer and the weapon jerked back in a huge shower of flaming sparks, there came no response from the interior.

"It's curious," frowned the Olgarch. "No one since Ens has even taken the trouble to invade the privacy of our minds, to pluck out the secret of our presence on their island."

"We obviously are beneath their contempt," Sam snarled. "No fit subjects for their lofty contemplation, damn them!" He walked hastily over to the next dome of iridescence, fists clenched, jaw ridged with hard little muscles. "By God, I'm going to make this fellow open up if I have to——"

He stopped short. "Well, what do you know about that?" he exclaimed.

As he had approached, the interlacement had suddenly burst into a lively glow. Inquiring feelers seemed to thrust outward. Then, as if satisfied, the light faded, the impalpable surge of waves grew thinner and thinner until, suddenly, it was gone.

EXPOSED to their astonished view was another being. He was like Ens, yet somehow dissimilar. By the standards of the three comrades, he was but a puny thing, yet his body was not quite so shrunken, his head not so huge as that of Ens. He balanced himself precariously on his tiny feet, his eyes alert.

"Welcome, men of alien ages," he piped in a thin, shrill voice. "Welcome to the Island of Asto. My name is Kar."

"Praise be to Zeus, the Provider!" ejaculated the Greek. "At last we find a trace of hospitality on this accursed island. My own name, stranger, is——"

"Kleon," completed Kar with the ghost of a smile on his sallow face. "My own vibrations are interlocked into the overhead dome. I know your names, your, histories, your rather feeble thoughts. But you are a novelty on Asto, where nothing physical ever happens. I was waiting impatiently for your arrival before my thought-seclusion."

"But we almost missed you," Sam ejaculated. "There are hundreds of your kind, each wrapped up in the selfish garment of his thoughts. We tried in vain to attract the attention of half a dozen. Suppose we had given up before we came this way?"

"That would have been too bad," squeaked Kar. "For, to tell the truth, I am becoming tired of my solitary contemplation. You see," he smiled pallidly, "I am not as far advanced as the others of my race. I have not been able to subjugate the last traces of my lower animal emotions, of which you possess such an overabundance."

"Then why," inquired the Olgarch, "did you not beckon to us, or come over to greet us? Surely you possess the faculty of locomotion, even on those legs."

Kar glanced down at his feeble limbs with certain shame. "They are grossly animal, are they not?" he said with an apologetic air. "Capable even of a crude form of locomotion. I told you that I have lagged behind the status of the others, like Ens, who could not even rise as I do from seated contemplation. But we do not use limbs for locomotion. They belong to primitive times, even as your ships and rocket planes. We could, if we wished, transfer ourselves even to the farthest stars by the mere power of thought. But I would never have intruded on the privacy of Ens, or of any of the others. That is not done on Asto. It is, in fact, inconceivable. Each one of us is entitled to his privacy, to the solitary contemplation of his own excellencies, of his own ratiocinations."

"Individualists," Sam murmured. "Cold intellectualism of the worst kind."

"Naturally," Kar assented. "What else can the intellect be? Thought is essentially a solitary process, not a community affair. Long ago this island was delimited into prescribed areas, exclusive to the individual. We do not trespass on each other's privacy."

"This is all very well," Kleon interposed with a certain asperity. "I, myself, used to love philosophical discussions. I walked with Aristotle and I conversed at length with the Gymnosophists. But just now I confess that they are profitless in the presence of an empty belly."

Sam grinned faintly. "Now that you bring it up again——"

"You mean you are hungry?" demanded the bulbous-headed man with a show of surprise. "A grossly animal desire from which even we are not wholly exempt. Wait a moment."

Puzzled, the three comrades watched.

KAR had corrugated the damp skin of his great forehead. It wrinkled into frowning concentration. He stared with pulsing eyes at a round, smooth ball of crystal clearness that seemed suspended over the void of a pit that sank bottomlessly into the dark gray lava. They had not noticed it before.

Even as they followed his glance, the ball clouded under the impact of his will. Slowly it began to spin. Round and round and round, faster and faster, while the cloudiness deepened and became a lambent cherry-red.

Under the impulse of his thoughts

the ball spun more and more swiftly.

As it spun, deep within the cylindrical pit there came a hum, the whir of strange machinery. The hum deepened to a full-throated drone. The ground vibrated.

Then, suddenly, a tiny platform rose swiftly into view. On it, forlorn on the metal expanse, were three small pills. "Aspirin," thought Sam incredulously. Kar relaxed, waved his long, slender neck toward them invitingly. "One for each of you," he piped. "Food for your bodies."

Kleon's classic features darkened. Involuntarily his fingers tightened around the hilt of his sword. "That little pellet food?" he flared angrily. "You are pleased to jest with hungry men, friend Kar, and I am in no mood for jesting."

"Synthetic pellets," the Olgarch explained quickly to the hot-headed Greek. "Concentrated essence of food. Hispan has done the same. But this is a different process."

"A very simple one," the man of Asto said indifferently. "Within the pit that delves into the earth is a complex of machinery. That little ball you see is the governor. Its special substance is attuned to the varying vibrations of my thought. I but will the requisite wave lengths, and the ball spins obediently. Beneath, the proper machinery is activated, and in the space of seconds the finished product is thrust up for my use. All my simple physical needs are thus provided for. Each one on this island does the same."

"I can understand the principle," the Olgarch replied with interest. "Granting, of course, your special faculty of projecting thought at a distance. But surely on this barren land you have not the necessary organic elements for food and clothing. Hydrogen, oxygen, sulphur and phosphorus, perhaps; but how about carbon, nitrogen, iron and manganese?"

Kar stared at him. "Even your Hispan is obviously of a restarted culture," he retorted. "Here we do not worry about the elements. Our machines use only the primal stuff of matter—electrons and protons—and weave them into the requisite atoms by compelling them into the proper orbit-states of energy. But eat!"

Gingerly Sam picked up his pill. It seemed small enough within the bluntness of his fingers. He thrust it, nevertheless, into his mouth, swallowed it. So did the others.

Sam Ward gulped, bewildered. He had hardly felt the pellet slide down his throat, yet a sense of fullness, or repletion, had already spread through his system. Strange tastes, subtle, fragrant, luxuriously different, salivated his glands, breathed Epicurean delights. He turned in time to see the broad grin of delight on Kleon's face. The Greek smacked his lips resoundingly. "It is magic," he said with a satisfied air, "but it is a good magic."

"We have eaten and drunk, in a way," Beltan said quietly. "Now there are other matters to be considered. The rocket hordes of Harg, for instance."

SAM started. He had almost forgotten about them in the immediacies of this Island of Asto. He thrust a quick glance upward. The doming web of thought vibrations was still in place, shifting, swirling with inherent power. The sky was not visible. Surely they were safe. Then he frowned. If the three of them, in a single rocket craft, had managed to detect the island, surely Vardu with his rocketing soldiers would have no difficulty.

"Harg?" queried Kar in some surprise. "What do you mean?"

"Well, you see," Kleon began, and stopped abruptly.

A man had materialized in their midst!

He was taller than either Ens or Kar; his body was lean, but fairly well formed. Even his head, though larger than normal, did not bulge as much with protruding thought. Sam Ward took an instant dislike to his coldly calculating eyes, the thin sneer that warped his colorless lips.

One moment the ground next to Kar had been vacant; now he was there, comfortably standing, his will beating like heavy wings against the minds of the three alien comrades.

"I know that I have done violence to the inviolable traditions of Asto in intruding upon your privacy, oh Kar," he declared with a negligent air, "but you and I are the only ones of all our race who retain to some extent the primitive instinct of curiosity; I noted these strange visitants of yours, and desired to know more of their purpose and of these strangers from Harg of whom they speak."

Kar looked astounded. More, he seemed positively aghast. There was a new asperity in his tone that dulled its squeakiness. "Your invasion of my domain is an incredible act, Ras. In all my thousand years of contemplation, in all the former memories of my father, no man of Asto has done the like."

"Then it is time we break loose from a silly tradition," Ras said contemptuously. "I confess I am getting a bit tired with the company of my own mind. I have nothing more to explore therein. It begins to bore me. I require new stimuli, fresh outlooks." He turned his inscrutable eyes on the astonished trio. "Such as the presence of these men of alien times, for example—such as knowledge of these hordes of Harg of whom they speak with such obvious fear."

The Greek had given ground before this sudden apparition. Involuntarily his shield came up; his lips moved in silent appeals to his gods.

But Beltan's proud features displayed no outer perturbation. "I take it, friend Ras," he said, "that you transported your bodily frame along the thrust of your concentrated will?"

The tall Astonian turned with a thin-lipped smile. "Naturally," he assented. "The secret of thought-transportation was discovered three millenia ago by our fathers. Our minds, through long practice and concentration, have become storage batteries of extremely high potential. We thrust out a steady stream of beam-thoughtwaves to the point in space desired. The potential at the receiving end is considerably lower. Our bodies, polarized in the direction of the beam, and infused with electro-magnetic vibrations, descend from the higher to the lower potential. The speed is of the order of light."

"Then you could travel anywhere, and as far as you like?" Sam asked quickly.

"Of course."

"But why should we?" squeaked Kar. His perturbation at this unheard-of invasion of his privacy had passed. "Could we contemplate the problems of the universe any better amid other and stranger surroundings? If anything, the outward show would distract our ideas, dissipate our energies."

RAS favored him with a sardonic glance. "I told you, Kar, that I for one have reached the end of my inner cogitations. I can go no further. Without doubt I have not sloughed off the physical as much as the rest of you."

Kar was properly shocked. He wagged his bulbous head. "There is no end to the exploration of one's own mind," he piped. "Perhaps I, too, have lagged a bit behind the others. But look at Ens, look at a hundred others. In ten thousand years they still will not have reached the end."

Ras disregarded him. His penetrating eyes impacted on Sam. Desperately Sam blanked his mind against the prying waves that seemed to suck him dry. "Tell me more of this race of Harg," the Astonian demanded softly.

The twentieth-century man complied unwillingly. In any event, he reflected, he could not withhold secrets from these islanders. He told of their stumbling upon the hydraulic, stellene-enclosed city, of its fascist totalitarianism, its science, its incredible army of rocket soldiers. He described how they had managed to escape, with the aid of the Hetera Alanie; how Vardu had wrested control from Hanso and had sworn to subjugate the Earth. How they had ever fled before his pursuing hordes in the stolen rocket skip and found no other civilization but this Island of Asto.

"Except for the neutron city of Hispan," Ras said with a side glance at the Olgarch.

"Which is impregnable to all attack," declared Beltan with proud dignity.

"But you must take warning," asserted Sam. "When we sped out over the Pacific in last desperate flight, Vardu was close on our trail. His hordes will soon arrive. They have numbers, weapons of tremendous destruction. Even your thought-enclosures are insufficient. But if you will get to work, fashion counter-weapons as no doubt you can, you may rid all Earth of this threat to its safety."

"The mesh of all our thoughts is impenetrable to the combined superforces of the universe," piped Kar positively. "It is the fundamental substratum of matter as well as of space. It is eternal, indestructible. Even if the universe should flame in ruining destruction, the projection of our thoughts would nevertheless remain intact."

"I can well believe it," Kleon cried ruefully. He stared at his futile sword and javelin. Since they had been turned aside by an immaterial shimmer his child-like faith in himself had sagged. In spite of his adventures in Hispan, at Harg, and now on Asto, his mind was still too steeped in the habits of the old Greek world to grasp entire the mighty forces that ensuing centuries had unleashed.

"That is true," Ras said absently. He seemed to be absorbed in his own thoughts.

"But at least," insisted Beltan, "even if you are safe, think of the rest of Earth.

There may be other cities not nearly as advanced as you, whose defenses may not be proof against the might of Harg."

"They are no concern of ours," Ras answered brusquely. His eyes were speculative; a tiny smile thinned his lips.

"A thoroughly selfish attitude," cried Sam indignantly. But he was talking to thin air. A moment before Ras had stood there, close to Kar. Now, a wind stirred and rustled as air rushed in to fill the void of his form.

Kleon's blue eyes popped. "Aie!" he gasped. "Where did he go?"

"No doubt he went back to the privacy of his own meditations," Kar said indifferently. "He was bored with excess talk. It is a drain on our vitality to speak."

THE Olgarch shook his tawny head. There was rarely disapproval in his level eyes, but now a shadow had passed over them. "If this Island of Asto represents truly the intellectual advance of the future, then the outlook is dark indeed. Thought that has ingrown, rather than expanded—thought that seeks the inner seeds of specialized decay, that grows narrower as it waxes mighty. It seemingly brings in its train the exaltation of the individual and the total obliteration of the race. I'm beginning to think that evolution has taken the wrong path, that friend Kleon with his emphasis of the physical represents a more natural, wholesome course."

"Know you," Kleon flared angrily, "that I am a philosopher and a man of letters as well as a fighting man. I have witnessed the passage of ten thousand years and have seen nothing to compare with the flame of intellect that played over Athens and Corinth and Thebes and the cities of the Ionian coast."

"He is right," Sam affirmed. "A little more of the old Greek ideal of a sound mind in a sound body—a happy balancing—would have worked wonders for these overemphasized States of the future. Oligarchy in Hispan, Fascism in Harg—and Anarchic Individualism here in Asto."

"I chose my words badly," Beltan apologized. "That was in fact what I meant." He broke off abruptly, frowned. He turned slowly to Kar, whose eyes were already sinking within their sockets; as if he, too, were wearied with much talk.

"Where is the domain of Ras?"

The Astonian's eyes opened a trifle. His voice was a thin whisper. "To the left of Ens," he answered. "Now go. I am already wearied of your finite intellects. I wish to probe deeper into myself."

"But there are certain matters that must be settled," the Olgarch protested.

It was too late. The sound of his voice beat in vain against a blanketing screen of thought. Kar had faded from sight, was already hidden within the mesh of his vibratory intellect.

"That's that," declared Sam with a wry smile. "Nice people, these Astonians. Even Kar, who seemed the most human of them all."

"I say we leave them to their fate," Kleon declared angrily. "Let us go on to seek other cities."

"You forget," Sam reminded him, "we've run out of rocket fuel. I had wanted Kar to make us some, but he didn't give us a chance." He cupped his hands. "Hey, there, you within! Come out for a moment. We need a little help!"

But there came no answer from the enveloping shimmer.

The three stranded adventurers turned and stared at each other. Their plight was desperate. With Kar's withdrawal, the last chance of aid had vanished. As far as these self-centered intellects of Asto were concerned, they could starve without a helping hand being raised in their behalf. And ever present in their consciousness was the knowledge that the fanatic hordes of Harg were on the way. Each knew that little mercy might be expected from Vardu, their Leader.

"Let us seek Ras again," Beltan decided suddenly.

Sam shrugged. There had been something about that thin-lipped Astonian that had repelled. But anything was better than standing vacantly before a shimmer of impalpable thought.

They trudged through the crunching pumice in silence. The rocket ship loomed in front of them, disconsolate, futile-looking without the precious fuel.

They passed the hazy iridescence of many concealing curtains. Behind each a being roosted, oblivious to all but himself and the exploration of his own mind. Before each one they paused and tried to penetrate the silences, to rouse the creature within. They failed each time.

EVEN Beltan's proud calm took on sharp-edged tones at repeated failure. He fingered his electro-blaster as if tempted to try its power against the arrogant withdrawals. But he smiled wearily and thrust it back into his belt.

Ens was passed without even a hail. Then Sam stopped, looked about with a bewildered air. "That's funny," he remarked. "I could have sworn this was the spot to which Kar alluded as the seated domicile of Ras."

"It is," Beltan responded with a quiet frown. He pointed. "Look! There is a fresh-smoothed surface where a cylindrical pit once existed. Ras has obliterated it—filled it in!"

"But why?" Kleon demanded. "Where could he have gone?"

The Olgarch's eyes were steady. "I was afraid of this," he said. "He seemed restless, bored with his thousand years of contemplation. He has left the Island of Asto."

"Left it?" echoed the others.

"Yes. Our unexpected arrival gave him the idea. That, and the story he derived from our minds and our tongues.

He has gone to meet the oncoming hordes of Harg."

"To fight them alone!" exclaimed Kleon, his eyes kindling. "Aie! I had not expected such noble courage from a puny thing like him." He struck his javelin against his shield with a resounding clash. "I wish he had taken me along."

Sam said softly and with a certain tenderness: "You still possess the child-like faith of your day, my Kleon. You cannot understand the twisted corridors of these minds of the future. Ras has not gone to fight Vardu. He has gone forth to make an alliance with him, to propose that they join forces and thereby become irresistible. A mighty intellect joined to a mighty fanaticism. Nothing on Earth will be able to withstand that combination."

Beltan nodded somberly. "That was also in my mind, Sam," he said.

"But—but—" the Greek sputtered, "that would make him a traitor against his own kind. No man is so base——"

"Are they not?" Sam retorted grimly. "History is strewn with such examples. Your own Greek world had plenty. Besides, on this Island of Individualists there are no binding ties. Supreme selfishness is the approved rule."

Beltan said quietly and with emphasis, "Here they come now. Vardu was closer on our trail than I had thought."

Startled, they stared upward at the sky.

They beheld a sight thrilling, awe-inspiring—yet deathly ominous in its implications.

There was a rift in the weaving dome of thought-projections—the single community effort of the anarchic individuals of Asto. A neat round patch where, earlier, the emanations of Ras had fused the shield to a completed whole.

The blue sky beyond was aflame with hurtling projectiles. A hundred thousand Hargian soldiers, each enclosed in his stellene cylinder, grasping his stellene-tipped disintegration rod, face blazing with the inner fires of fanaticism.

Behind them blasted long streamers of fire, catapulting them straight for the Island of Asto at terrific speeds. The Pacific rocked and roared with the thunder of their coming. In the van, a huge rocket ship slammed along with all jets open.

"Run for it!" Sam yelled.

"Where to?" the Greek ejaculated.

"Back to Kar. If we can only make him understand!"

THEY raced over the furrowed lava, hearts pounding, ears deafened with the mighty vibrations. Already the hordes were pouring through the gap in the intangible haze.

Straight for the thought-enwrapped Ens they lanced. A thousand rods jerked forward; a thousand blasts of atomic destruction crashed through resistant air.

Horrified, the three fugitives stumbled blindly on, heads twisted backward to view the awesome sight.

An unequal battle! A lone puny being, wrapped only in the projections of his own thought, against a hundred thousand warriors, armed with weapons that crashed the atoms in their courses!

A dome of fiery red blazed with insupportable brilliance. The pumice ground flared and shattered into primal electrons. Billowing gases spattered into coruscating dust. Again and again the bolts crashed forth; again the meshed enlacement of Ens glowed and hissed.

"It's impossible for him to exist within that molten shell," Sam groaned. "They'll break through in another second."

"I'm not so sure," answered Beltan as he ran. "Thought is more primal than matter. Look!"

Kleon gasped, had stopped in mid-stride. Astounded, they stared back at the holocaust, forgetful of their own danger.

The beleaguered shell of Ens was expanding. Slowly at first, then more and more rapidly. The red tints shifted to a blinding white, then to an almost invisible, furious blue. The rocket-warriors clustered round it like a thousand stinging wasps; the pointed rods flamed with red destruction.

But the immaterial dome rushed outward with increasing speed. Its blazing surface caught the crowding vanguard of the Hargians. There was a series of tremendous detonations, a spray of cometary sparks. A hundred Hargians vanished into nothingness.

The assault redoubled. A thousand more hurtled forward, belching bolts of searing fire. The thought-shell flared anew under the tremendous impacts.

But steadily, remorselessly, the flaming traceries expanded, engulfed more and more of the rocket-warriors, whiffed them to extinction.

Sam was rooted in his tracks. "Good God!" he yelled. "No wonder the Astonians were not disturbed at our warnings. Why, he's wiping out the entire horde, singlehanded."

The Greek's eyes glowed with the lust of battle. He brandished his javelin joyously. "By Castor and Pollux, I take everything back I ever said. This puts Thermopylae into the shade."

But Beltan said: "It's simple enough. Thought is obviously the substratum of the universe. Its waves—more fundamental than electron trains—are unaffected by material weapons. But its own vibrations, when concentrated, set up a dissonance in the orbits of the atoms and burst them asunder."

"The point is," cried Sam, "that Harg is defeated, and whatever cities of Earth that may exist are saved."

Pain shadowed the Olgarch's eyes. "I am not so certain of that. Here comes the rocket ship."

The silvery craft plunged down into the melee with a thunder of jets. An amplifier ripped a fierce command through the turmoil and crash of battle.

"Back, men of Harg!"

WITHIN the shining hull two men stood erect. One was tall and dark of face; a tiny mustache rode his snarling lip.

"Vardu!" screamed Kleon, and lifted his javelin.

Sam caught his hand in time. "You fool," he cried. "You wouldn't last a moment if they knew you're here. Besides, Vardu's not the dangerous one now. It's Ras!"

The renegade Astonian stood at the side of the Hargian Leader. He was slighter, punier, with bulging, ungainly head. An unpleasant smile played over his thin lips.

Swiftly a haze enveloped them both, a screen behind which their features grew vague and shifting. The screen expanded to meet the onrushing shield of Ens. There was impact.

The very Island reeled on its foundations. A blast of hellish fire ran like a flaming sword deep into the earth, up to the very heavens. The overlaying, feebler curtain of vibrations ripped asunder like smoke puffs in a hurricane. The blue Pacific reared in mountain-high breakers. Sound screamed and battered at paralyzed eardrums. The stellene-enclosed men of Harg tossed violently in the gale. Sam was flattened to the ground.

Two mighty intellects opposed each other with weapons such as the world had never seen before! Projected thoughts, meeting in head-on collision like runaway stars, thrusting and heaving at each other with forces huger than those implicit in the bowels of the Sun.

The dazzled trio picked themselves up, crouched aghast at the titanic conflict. For once their reckless daring, their sense of self-confident arrogance deserted them. They felt like tiny insects in the presence of the elemental. Even the fanatics of Harg, trained to unthinking immolation, pressed back against the still-oncoming rush of their fellows. The stage was set for the solitary struggle!

For what seemed eons the conflict ebbed and flowed. The two spheres of thought crashed and flared and crashed again. The universe seemed to be split asunder.

Then, suddenly, it was over!

The blinding light flickered, grew pale. The thought-shells shimmered, thinned. The roar and thunder muttered away. The shells vanished.

Two antagonists, Astonians both, faced each other, naked, defenceless, their mighty thought-screens cancelled and made null and void by the mutually opposing forces.

Ras had a triumphant smile on his evil countenance. Vardu, next to him, looked scared, frightened out of his wits.

Ens, still seated on his cushioned mound, his futile shanks crossed beneath his spindly body, stared calmly upward at the threatening hordes. Ras said something sharply. Vardu jerked erect, crashed out an order through the amplifier.

"Slay!"

A hundred stellene rods uplifted, blasted forth screaming disintegration. Ens, still calmly staring, flashed to extinction.

WITH a huge shout of Harg! Harg! the countless hordes flung themselves upon the next Astonian, toward the other end of the island. Again the solid land shook and rumbled with the noise of battle.

"The blind, unutterable fools," panted Sam as he stumbled along. "If they'd only unite their thought screens, they could blast Ras and Vardu and all their men to hell and gone in an instant. This way they'll be butchered one by one."

"They are individualists," groaned the Olgarch. "In the course of thousands of years they have lost the faculty of community effort. Each is a law unto himself."

"They are weaklings, not men." countered Kleon fiercely, "in spite of their intellects. They deserve to be wiped out."

"Except that we go with them," Sam said with grim emphasis. "Our sole hope is to convince Kar before the mopping-up process reaches us. Ah. there he is!"

The dome-like evanescence was opaque, quiescent. Beltan raised his voice, shouted above the roar of farther battle. "Kar, oh Kar! Show yourself and hear us. Your own fate, the fate of all your comrades, depends upon your listening."

Slowly the shield grew transparent, fell away. Kar stared out at them with calm, untroubled glance. "Why do you disturb my meditations?" he piped. "You have broken the train of a deep problem involving the ultimate fate of the universe."

"In another few minutes it wouldn't matter anyway," Sam told him bitterly. "Ras has turned traitor, is leading the forces of Harg against his fellows. One by one they are easy prey. But if you can arouse them, get them to unite——"

Kar looked at him with queer surprise. "Unite?" he echoed. "That is a word we do not know. It would mean the end of all our privacy—the end of all secluded thought. The fine balance of our intellects would be destroyed forever."

"So you'd rather die, like rats in a trap!" Kleon cried.

Kar turned his bulging head toward the Greek. "Even death," he declared, "is better than sinking one's individuality in the common will—than losing one's identity."

They argued, they pleaded, they screamed insults and objurgations. But the Astonian was calm, immovable, impervious to all argument. And meanwhile, one by one, each by each, after gigantic conflicts, the farther island was being cleared. The din was terrific, the flashes of lightning blasts insupportable. The tide of war was swinging around, creeping toward them.

"All right, man of the future," Kleon ended angrily. "Die if you wish, without a struggle. I have seen enough of the future. I'm only sorry I did not fall in the fight with Porus. At least that would have been a glorious death, among my comrades and under the very eyes of great Alexander."

Kar meditated, shook his huge head on its spindly stalk. "I shall not die," he decided finally. "There are still certain problems to be solved."

"You mean," demanded Beltan, "that you will rouse your fellows, present a united front to the enemy?"

KAR looked at him with pitying condescension. "I do not mean that, stranger. That would be impossible. But I shall withdraw myself from Asto where I have meditated for more than a thousand years, and pursue my solitary thoughts in peaceful surroundings."

"Good!" exclaimed Sam. "You will take us with you?"

"Not at all," declared the Astonian. "You are intruders upon my privacy. You have disturbed me enough. Goodbye!"

Sam jerked forward, cursing—but he was stumbling over nothingness. A moment ago Kar had stood before them. Now he was gone—vanished with a whoosh of inrushing air.

"By Heracles," muttered Kleon, shaking his javelin savagely, "I wish I had run him through on the spot."

Beltan's aristocratic face was pale, yet unmoved. "We have lost our last chance," he said quietly. He unloosed the electro-blaster from his belt. "Come, my friends, at least we shall go down fighting, as befits brave men."

But Sam's brows were furrowed on the cylindrical pit before him—the pit which held deep within its bowels the machinery whereby Kar had manufactured all the wants of his former existence. The crystal ball still hung suspended over the void.

"I wonder—!" he spoke half to himself. He swung around, peered through the billowing smoke of disintegration, the appalling sheets of flame, against which the shrieking, hurtling rocket hordes of Harg seemed like so many demons. "Good!" he cried, "our craft is still intact." He whirled back on Beltan, eyes burning with a new luster. "Do you think you would know how to handle Kar's machinery?"

The Olgarch looked doubtful. "It is hard to say. From Kar's description I detected certain resemblances to what the Technicians of Hispan have evolved. But, of course, I couldn't manipulate his crystal ball by the power of thought. I'd have to work with the machinery direct. Why do you ask?"

"Our rocket craft, by some freak of good fortune, is still intact," Sam explained rapidly. "Now if we only had some rocket fuel—a few gallons of liquid hydrogen, a tank of liquid oxygen——"

"Say no more," declared the Olgarch decisively. "I understand. How long do you think it will be before the horde sweeps over to this end of the island?"

"About fifteen minutes."

Kleon groaned. "Little time enough." But already the Olgarch had unbuckled his electro-blaster, handed it to Sam, and had swung himself lithely over the edge of the pit. Anxiously, his two comrades peered down into the smooth-walled cylinder. Beltan was standing on a ledge that ran spirally down, moving sensitive fingers over the shiny surfaces of intricate machines whose very design were wholly foreign to Sam, not to speak of Kleon.

"What do you think?" Sam shouted. Beltan did not look up. His whole being was absorbed in a frantic effort to understand, to find a clue toward operation. "I don't know," his voice echoed up. "There are certain elements of familiarity, that is all as yet."

Kleon jerked suddenly erect, whirled, jabbed with his javelin in a single motion. Air screamed around them. Like a plummet, a Hargian soldier, his blond face cruel, hate-distorted, swooped out of the clouds of soot. A rocket jet blasted behind him. His hand held a lethal rod, its narrow muzzle snouted down through the monodirectional stellene envelope.

The javelin drove straight through the tiny opening. With a mighty thrust Kleon twisted. Then he was flung backward, the weapon jerked from his hand, borne down by the fierce momentum of that earthward drive.

But the Hargian's aim had been diverted. The blast of disintegration seared a great gap in the lava soil yards away. Sam levelled the electro-blaster. Blue bolts crashed forth. The soldier within his stellene tube crisped and flamed in death-agony.

"Whew!" Sam wiped his brow. "If it hadn't been for your quick wit, Kleon, our adventures would have been over."

"There will be more." The Greek picked himself up, breathing hard. "The flashes are moving our way now."

IT had been sheer luck that the hordes were still concentrated on the last few individualists at the farther end. And luckier still that billowing clouds of soot and dust made a thick pall over everything. Kleon was right. Where one had stumbled by accident upon them, there would be hundreds and thousands all too soon.

"Hurry, Beltan!" Sam yelled into the depths.

"I'm doing my best," the Olgarch answered. "I've already got an understanding of the fundamental principle of these machines, but how to get them started is another matter. Hold them off as long as possible."

"We'll do it," snapped Sam grimly. "Keep going!"

To Kleon he said: "Did you hear that?"

The Greek nodded joyously. His nostrils were wide, eager with the snuff of battle. He slung his javelin behind him, hefted his sword lovingly. His shield protected his breast. "Let them come, friend Sam. We'll show these creatures of the future that there were men in the olden days—men who knew how to fight and how to die."

Sam grinned affectionately. A tag of an old book ran in his mind. Three musketeers, three dauntless men separated by eons of time, yet as one against a hostile world. It was good to be of their company.

His fingers tightened on the electro-blaster. His own gun was useless against the stellene envelopes. Even Kleon's ancient sword was better. Shoulder to shoulder they stood, eyes alert, peering vainly into the hell of sound and flame and blanketing soot that enveloped them:

"Here comes one," shouted Kleon suddenly.

A red rocket trail ripped through the murk, blasted toward them. Sam saw the startled look in the Hargian's eyes as he zoomed unwittingly upon the crouched figures on the edge of the pit. He jerked frantically on his stellene rod. Sam loosed a stream of crackling electric charges. The man died with a jarring thud upon the hard, lava floor.

Even as he fell, Kleon lashed forward with a tremendous stroke. Another blundering soldier had hurtled out of the enshrouding gloom. The fierce thrust swung the hard stellene shell to one side. Its nose buried itself unharmed within the stony ground. But the figure within catapulted forward against the metal. His neck snapped to one side, broken.

"Good work!" Sam approved. "They're coming fast now."

Kleon grinned. This was life; this was exaltation. Death no longer mattered. His sword had held its own against the magical weapons of the future.

The surrounding fog began to belch forth Hargians. The brilliant sears of flame where Ras and his former comrades locked in tremendous struggle drew closer and closer. Soon they would be upon the embattled three in overwhelming mass.

"How's it going, Beltan?" Sam yelled anxiously.

The Olgarch's voice rose muffled, excited. "Give me another five minutes."

Sam set his teeth hard. "Ten, if necessary," he shouted back with false optimism. And as he shouted, he shot down another Hargian. How many charges were left within the mechanism he had no way of telling—but they must be few indeed.

They came fast and thick now. Kleon cut and thrust like some terrible god. By sheer weight of arm and power of shoulder he parried the hurtling—but unstable—rockets, sent them crashing to the ground. Sam's fingers ached with the searing heat of rapid fire. Around them, in a flaming circle, were dead men, each within his shell of stellene.

THEN, with a click, the electroblaster was empty. "That's the end," whispered Sam with a wry smile. "It was a good fight while it lasted."

Far beneath they heard a whoop. "I've got it," cried the Olgarch. "I've found the key. Within a minute—" Never had they heard him so excited.

"A minute," groaned Sam. "He might as well ask for eternity. Here they come."

To one side the hordes were massing, moving with relentless deliberation toward them. The other end of the island was bare of Astonians. Now they were coming to clean up the few who still remained within their shells of thought, too absorbed, too indifferent to flee to save their lives.

"Sam Ward!" Kleon cried out in a great voice. "How about the weapons of Harg? Surely you must know how to manipulate their secrets."

"Kleon, you old son!" Sam yelled joyfully. "Of course!"

He raced to those tubes where the rods had been thrust through the transparent covering in vain attempt to bring them into action. He ripped hard, jerked two free. One for Kleon and one for himself.

There was a tiny knob near the handle. A single pressure, and a beam of force sped to its mark.

Again they were armed!

Beltan's tawny head emerged suddenly from the pit, the muscles of his face tense with strain. His both hands tugged at two glass-like containers. Within their walls colorless liquids tumbled. Even as he stumbled out upon the ground the transparent walls clouded and frosted with snow. Liquid hydrogen—liquid oxygen.

"Run for the plane," Sam yelled. "We'll hold them off."

"Here they come," shouted the Greek.

The Hargians had seen them now. A detachment swung off from the main concentration of the horde, swooped for the three running men like falling meteors.

Screaming bolts of red lightning seared around them, blasted great holes in the smoking terrain. Sam and Kleon flung up their captured rods, squeezed down. The foremost Hargians puffed into clouds of dust, but more whooshed through the air like angry bees.

"A huge pit opened suddenly in front of Sam. The sleeve of his shirt vanished. A fiery pain etched his arm.

"Run, Beltan!" he shouted above the blistering turmoil. "We can't hold them off much longer."

THE Olgarch's face was white and drawn. His breath came in sobbing gulps. The cans were heavy and the ground rose about him in flying fragments. Ahead lay the inert rocket plane and the slim chance of safety. Behind, only two stout comrades to ward off an army of rocketing soldiers.

How he made it he never knew. How—in a sort of fevered nightmare—his stiffened fingers, burnt to the bone by the fierce cold of the liquids, emptied the containers into the proper tanks. Even stabbing at the controls while Sam and Kleon tumbled in was forever lost in fuddling memory.

As the slim craft trembled in every strut, and took off with full-throated roar, the huge ship of Vardu thundered along. Within its hull the Hargian Leader stood, sallow face furious, shouting indistinguishable words. At his side crouched Ras, his bulging forehead frowning in strained concentration. Around him rose a mist—a shimmering cloud that reached out after the fleeing plane.

"Faster!" screamed Sam. "Once that thought-screen envelops us, we're lost."

Beltan, black, sooty of face, staggered as in a dream, stumbled blindly against the controls. Somehow his wounded fingers found their mark, pressed with dying vigor.

The fleet ship responded like a startled bird. It accelerated with a screeching of tortured plates. The pursuing web of force reached out in avid swirls, missed, fell slowly behind. The heavy cruiser limped badly to the rear, outdistanced. The Island of Asto, with its holocaust of mighty minds, its barren soil a smoking welter, swarmed over by the triumphant hordes of Harg, vanished in the bosom of the Pacific.

Kleon roused himself, grinned through split lips. "What do we do now, oh Sam Ward?"

The American tottered to the bow, stared over the blue depths of a faint edging line on the horizon. "Harg has broken loose," he said grimly. "With Vardu in control, it was a menace to whatever peoples still exist on Earth. Now, reinforced by the tremendous intellect of Ras, it is an overwhelming threat. Yet we must not despair; we must find those other races—give them warning of what is coming."

"Still looking for your mythical city where evolution has gone ahead in accordance with twentieth-century dreams, eh Sam?" whispered the Olgarch with kindly irony.

"Yes!" It was a simple answer, but Sam's pain-struck eyes burned on the far horizon. There must be; there had to be——

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.