RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

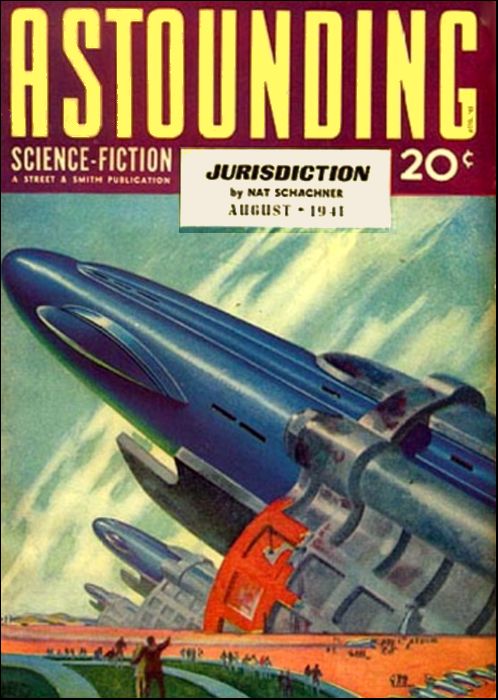

Astounding Science Fiction, August 1941, with "Jurisdiction"

Kerry Dale, sky-lawyer, proves a crook may be smart at sabotage, murder end assorted crime, but it takes a navigator to steal a sky-mine!

SIMEON KENTON, of Kenton Space Enterprises, Unlimited, was in a terrific temper. He paced up and down the confines of his office with short, rapid steps that tossed his deceptive halo of white hair into utter confusion. His mildly whiskered saint's visage was screwed up into unutterable knots. In his tight-clutched fingers was a blue spacegram which he shook violently at his daughter at each choking pause in his peroration.

"Dadblast that dingfoodled young scalawag of a Kerry Dale!" he exploded. "Look at this, will you? Of all the impudent, sonearned—I mean condarned—damn it, you know what I mean!" When Simeon Kenton was exasperated, his tongue had a habit of twisting and stumbling over the quick rush of his ideas.

"I think I know what you mean," his daughter, Sally, admitted demurely. Her eyes danced and secreted understanding, albeit slightly wicked, humor. She loved her irascible father, who was known to all and sundry as Old Fireball because of his habit of exploding on the slightest provocation. They might tilt at each other and parry deft strokes for the sheer intellectual joy of the thing, but underneath her slim, proud beauty there functioned a brain as keen and hard as the one that had propelled old Simeon to the commanding position he had achieved on the spaceways and in the industrial marts of the System.

Simeon Kenton, sole owner and guiding intelligence of the far-flung Kenton Space Enterprises, was more than a power. He was an institution. His spaceships traveled the charted lanes from Venus to the Jovian satellites and poked their sleek noses inquiringly into those reaches as yet unexplored. His word was the law and the prophets to thousands of hard-bitten spacemen who swore with many a public oath at his tyranny and wouldn't have exchanged it for the softest-cushioned job with any other outfit. Even the Interplanetary Commission, administrative arbiter of the spaceways, thought twice before they tangled in legal battle with explosive Old Fireball.

But one young man had refused to be overawed by the prestige of the Kenton name and had given him battle. More than that, he had won—much to Simeon's loud outward lamentation and secret inner delight. Simeon loved a good fight, and here at last was a foeman who seemed worthy of his steel. This very same Kerry Dale had been, not many months before, a subordinate young lawyer in his legal entourage.

"I think I know what you mean," Sally repeated. "You mean that Kerry Dale has turned down your proposition."

Old Simeon glared at her and waved the offending spacegram so violently it ripped in his fingers. "I offered to take him back into my service as a lawyer," he shouted. "I offered to forget that dirty trick he pulled on me about the colliding asteroids which cost me over a hundred thousand. I even hinted that within a year or so he might succeed that dithering ass, Roger Horn, as Chief of my Legal Department. I mentioned delicately I'd tear up that contract he had signed when drunk obligating him to eight more months of cargo-toting on my ships."

"Which was very sweet of you, Dad," murmured Sally, "considering that the said Mr. Dale has already wangled a general release out of you."

"Don't interrupt, child!" snapped her father. He returned to his grievance—the torn, fluttering spacegram in his hand. "Yet what do you think he had the didgosted effrontery to reply."

"I have a faint idea; but tell me, anyway."

"He says—confound him—he doesn't want a job. With me, or with anyone else. He's doing quite well on his own; and he expects to do even better. However, if I'd be willing to associate with him as an equal partner in some ventures he has in mind, he might consider me."

Old Simeon paused for breath. His blue eyes glared with baleful incongruity in the mild-mannered frame of his visage. "Me!" he choked. "Me, Simeon Kenton, being offered an equal partnership by a babe in arms, a puling young whelp!" His very beard seemed to quiver and grow electric at the enormity of the thought.

Then, suddenly he stopped and grinned. It was an impish, waggish grin that transformed his mobile countenance into a sunny burst. "Not at least," he amended, "until I've licked him and taken him down a peg or two."

"That might take a long time," Sally pointed out. "He won the first round over you, and he might just as well take the second and the third. I think, dad, his proposition isn't such a bad idea at that."

SALLY didn't tell her storm-tossed parent that she had already sent a spacegram to the subject of their debate congratulating him on his victory over the mighty Simeon. They had met only once, and then under rather untoward circumstances. To be exact, it was at the very moment that Kerry Dale was being fired by her father, or was resigning in hot dudgeon—the truth of the matter seemed to depend on who was telling the story. Sally had decided then and there that all the other eligible young men who danced constant attendance on her meant less than nothing. Though young Dale had seemingly not even given her a second glance, that didn't matter. He would, she was determined, and that in the very near future.

"Not a bad idea?" yelled Simeon. "It's a superlatively atrocious idea! Har-rumph! I grant you he knows law, but he's still a young snipperwhipper. Just because he took advantage of some obscure sections of a coff-eaten mode—I mean a mode-eaten coff—oh, ding it, you know what I mean—to steal my hard-earned money from me is no reason for this new foundconded impudence of his. Partner! Bah! And bah again!"

"And triple bah!" agreed Sally. "Nevertheless, suppose this same impudent young man decides to take his proposition, whatever it is, to Jericho Foote? You know Jericho. He'll very likely take him up on it, just to annoy you."

Now the name of Jericho Foote, President of Mammoth Exploitations, was like a red undershirt to a bull, or a cobra to a mongoose. Mammoth was Kenton's chief competitor along the spaceways. They fought for cargoes and trade routes and asteroids. Old Simeon, for all his spluttering and tough fiber, fought fairly and squarely; whereas Foote was devious and subterranean in his ways. He never met his explosive competitor in forthright, honest fashion; he never met anyone or anything that way. Dark and skulking methods were his particular delight; and the darker they were and the more they skulked, the better.

"That rubble-dyed Venusian swamp snake!" said Simeon incredulously. "He take up with Kerry Dale? Impossible! Dale is too—"

"Sensible?" Sally finished for him. "That is just what I've been saying. But if you turn him down—"

Her father calmed suddenly. "You love him, don't you?"

"Yes," she said. Being her father's daughter she never evaded an issue. "And I expect to marry him some day, whether he knows it now or not."

Looking at her, old Simeon could well believe it. No young man could long resist his slim, calm-eyed young daughter. He went to her and kissed her. His voice softened. "He's got the right stuff in him, Sally, in spite of his whangdoodled brashness. But his head's liable to grow too big for him if he gets what he wants too easily. Let him fight the hard way for success; the way I did. Let him fight me, if necessary; it will do him good. And I'll fight him back, tooth and nail. If he wins through, I want him to win on his own, and not because his future father-in-law made the way easy."

Sally nodded thoughtfully. Then a gay smile made a sunburst of her countenance. "All right, Dad. Go ahead and get in your dirtiest licks. But don't mind if I root for the other side."

"I won't." He flicked the telecaster into life. He scowled at the communications operator. "Take a spacegram," he roared. "Addressed to Kerry Dale, Planets, Vesta. 'Your impudent proposition doesn't even merit turning down. My own offer withdrawn. Sent merely out off pity. Wash my hands of you. Expect presently to wash my hands with you. Kenton.'

"There, that will hold him. Now we'll see what stuff he's made of." He turned grinning toward his daughter. But Sally was no longer there. She had slipped silently out of the office.

A frown replaced the grin. The bluster died. No longer was he master of men; only an anxious parent. He shook his head; screwed up his face in thought.

He returned to the telecaster, and connected with the Earth-Mars Navigation offices. The clerk recognized him. "Good morning, Mr. Kenton," he said obsequiously. "What may we do for you?"

"When's the next ship leaving for Planets?"

"This evening, sir, at 0:45. The Erebus blasts off from Cradle No. 4, sir."

"Good. Make one reservation for me. Under the name of John Carter. I don't want my presence on board known."

"Of course. We'll be most happy to take care of it for you. You wish Suite A, naturally, sir. It's the very best—"

But he was talking to a blank screen.

THE Erebus was the luxury liner of the space ways. One thousand feet long it was, its hardened dural hull gleaming like silver in the powerful floodlights. Its equipment was the last word and its appointments luxurious. It carried first-class passengers only and express packages of small bulk but high value.

The usual crowd of loungers, friends and relatives gathered on the brightly illuminated rocket field to see the Erebus off. The last warning signal had been given. The visitors trooped down the swaying gangplank over the open struts of the cradle in which the mighty ship pointed its nose slantingly toward the stars. People waved outside. The passengers stood within the observation deck, securely quartzed in, waving back.

Then the protective shields whirred into place, cutting off sight for the blast-off. The field crew moved toward the gangplank, ready to swing it away.

A small aerocab shot like a bat out of hell across the field, thrust out landing gear and scattered the crowd headlong before its slithering stop. The car hadn't come to a halt before the cabby had flung to the ground, snatched at a single lightweight bag with one hand and swung at the door with the other. But his passenger, a girl with wind-blown locks and hasty traveling costume, had already sprung lightly out.

"Yell for them to hold it," she cried impatiently. "Don't worry about me."

The crowd growled, resentful of narrow escape. "Who the hell does she think she is?" squeaked a burly roustabout. "Almost running us down like we were—"

"Hold the ship!" bellowed the cabby. "Miss Kenton's coming on board."

The ground crew had the gangplank swinging wide. The foreman jumped at the name as if he had been blasted. He bellowed in turn. The long steel slant jerked, moved back into place. The growls of the crowd gave way to straining of necks, excited comments. The roustabout stopped in midflight, gulped and retreated hastily into the protective anonymity of his fellows.

But Sally was too used to gapings and respectful murmurs to pay any attention. She was running with lithe swiftness toward the ship; the cabby puffing behind her.

"We didn't know," apologized the foreman hastily.

She favored him with a quick smile. "Neither did I," she told him and vanished within the reopened port.

The foreman was dazzled. The girl had gone, but the smile remained with him, to be treasured and brought out again and again for inspection. He even foolishly boasted of it to his stout, work-roughened wife that night while swallowing a midnight meal. And regretted it for days thereafter. For his wife had a jealous heart and a blistering tongue; and she brooked no rivals.

The harried and obsequious purser was having a rough time of it.

"If we had only known you were taking passage," he wailed, "I would without question have reserved Suite A for you, Miss Kenton. But you see—"

Sally stamped a trim, determined foot. She pretended indignation. "I don't see. Why, pray, may I not have Suite A?"

"It's already occupied. It was reserved only this morning. By a Mr. John Carter."

"And who the devil is this Mr. Carter that he rates the only decent suite on board this ship?"

The purser thought unhappily of the really luxurious quarters he had shown this imperious young lady and which she had turned down. He didn't realize that under her indignant-seeming exterior she was enjoying herself hugely. Unknown to old Simeon, she had returned to his private office while he was packing, and found the telautotyped plate of her father's reservation under the name of Carter. It took her ten seconds then to make up her mind to board the same ship to Vesta; it took her rather more time to throw a sufficiency of clothes together in a bag.

"I don't know who he is," confessed the purser, "but he seems a most irascible old man. Almost blasted me out of the room when I stopped in very courteously to ask him if he required anything."

Sally smiled at this unflattering description of her father; hastily shifted the smile to a frozen stare.

"Then get him out. Give him another room—five other rooms, for all I care. I want Suite A."

The purser was desolate. "I'd be glad to do anything in my power, but you haven't seen this man. He'd bite my head off if I asked him anything like that. And, after all, the Space Code says specifically—"

"Bother the Space Code! If you're so frightened of this fellow, I'll speak to him myself. Take me to him."

The automatic elevator dropped them to Deck 3; the moving catwalk sped them toward Suite A. The purser surreptitiously wiped his brow. These rich dames, who thought they owned the Universe!

His discreet buzz was answered by a blast from the annunciator.

"Come in!"

The annunciator distorted the voice, but it couldn't mask the impatient rasp to it. The purser shut his eyes and muttered a hasty prayer. There'd be sparks flying when these two met. He wished himself anywhere else but at this particular spot.

The door whirred open; and they stepped in.

It was a beautiful suite; there was no question of that. The walls were photomuraled on receptive metal to give the effect of smiling fields back-dropped by snow-capped mountains. The ceiling appeared an open sky in which glowed innumerable worlds. Couches nestled around a central bath of artificial flame. Open doors disclosed twin bedrooms and a bathing pool filled with activated waters.

A man's back bent away from them. He was seeking a book in the recessed shelves.

"Can't I get peace and quiet even out in space?" he grumbled. "What the devil do you want now?"

"I want this suite," said Sally in a throaty, altered voice. "And I want it in a hurry. I'll give you exactly five minutes to pack and get out."

The purser was horrified. "Now please—" he started in protest.

But the man had jerked erect and pivoted on them. He was furious. His wispy white hair bristled with electric anger. "Give five minutes! Why, you impertinent—"

His jaw dropped ludicrously. "Sally!" he shouted. "In the name of all the blink-eyed comets, what are you doing here?"

She kissed him. "Suppose I ask you the same question? You know you're subject to vertigo."

The purser's eyes goggled. Simeon Kenton! Old Fireball himself. Father and daughter. He fled before this strange, incomprehensible pair could turn on him.

"Don't be silly," old Simeon said indignantly. "You can't get vertigo in space. Everything's up."

Sally shook her finger at him. "No evasions, please."

He cleared his throat. "Harrumph! I'm going to Planets. A business deal, my dear. Something that came up suddenly."

"A business deal?" she echoed meaningly. "Now confess!"

"Yes, a business deal!" he returned heatedly. "And furthermore—" He stopped short. He glared. "Never mind about me. What the ding-ding about you?"

She patted his cheek. "I'm on the same business deal that you are, most reverend parent. Only I bet I thought of it first."

Then the humor of it struck them simultaneously, and they laughed until the tears came and their voices were weak.

"We're both dadgusted fools," cried Simeon. "Only I'm the older one. Very well, I'll talk to that uppity snapperwhipper. But first I'm going to take all his ill-gotten gains away from him. He needs taking down a peg; otherwise you'll find there'll be no living with him."

"I still bet on him, Dad. I have an idea he won't be so easy to take down."

"That remains to be seen," Simeon said grimly. "The first time he just caught me off guard."

Sally pressed the buzzer. The purser appeared, haggard, defeated.

"Move my bag in here," she ordered. "Into the bedchamber next the pool."

"Y-yes, Miss Kenton. Y-yes, Mr. Kenton. I didn't know—"

"And why didn't you know?" yelled Simeon. But the purser had fled again.

THEY didn't find Kerry Dale at Planets. In the twelve days of their journey to that roaring boomtown on the edge of the Asteroid Belt the bird had flown the coop. Flustered officials scurried to bring the mighty Simeon Kenton information. "Young Kerry Dale? Yes, sir, he blasted off four Earth-days before. In what? Why... uh... seems like the young fellow had bought himself an old tramp freighter and fitted it out for salvage operations. Had incorporated himself, in fact, under the laws of Vesta. Mighty flexible and generous, the Vestan corporation laws, sir. Nothing like those of Earth and Mars. Initial fees nominal, sir, and the taxes are practically nothing." The official permitted himself a respectful wink. "We don't believe in pestering business. Nothing paternal about us—ha, ha. If Mr. Kenton would care to look at the advantages of transferring legal title to Vesta, we'd be most happy to discuss—"

"Stop your infernal chattering," roared Simeon. "I don't give a tail-ringed hoot about your silly laws. I'm asking simple questions and I want simple answers."

"Y-yes, sir," stammered the frightened official. Old Fireball certainly lived up to his reputation.

"Where did he go to?"

The records came out tremblingly. Long nose buried into the documents, lifted. "N-no destination, sir. Just cruising through the Asteroid Belt. Under the articles of incorporation, Space Salvage, Inc., does not have to file the port of call of its vessel at the time of blasting off. Hm-m-m! A very peculiar charter, sir. There are lots of clauses in it I've never seen before. We're pretty free and easy about those things, but not that much. I'm surprised our laws experts passed it."

"You don't know Mr. Kerry Dale," smiled Sally.

The Kentons went back to their hotel—the single good one in the rushing, roaring, inclosed city of Planets.

"Har-rumph!" observed old Simeon. "We seem to have come on a wild-goose chase. Salvage, indeed! Piracy, more likely. He'll starve to death trying to find salvage work from here to Jupiter. There ain't many ships out and most o' them's mine. And my captains just don't let their ships break down. They know better. Oh, well, a fool and his ill-gotten gains're soon parted. We might as well go home, child."

Sally's eyes felt queer and blurry. What was the matter with her? Here she was acting like any silly schoolgirl; literally throwing herself at the head of a young man whom she had seen only once and who didn't care a hoot about her. She had sent him a spacegram and he hadn't even had the decency to acknowledge it. She had tossed decorum to the winds of space and rocketed to Planets and he was gone. Her father was right! He was a fool; an egoistic, self-centered fool. She'd show him! She'd go right back and forget—

"I'm staying here, Dad," she said aloud, miserably aware of her illogic.

"You're a rubble-dyed idiot, daughter," snorted Simeon. "And if you want to make a blasted show of yourself, go ahead. As for me, I'm going—"

They were moving across the soft-padded lobby of the hotel. A man was registering at the scanning booth. The scanner registered his picture and other pertinent data and transferred it to the photoelectric cells guarding the panel of the room to which he had been assigned.

He turned as they came up. His eyes wavered on the Kentons, smiled palely and slid past them.

Simeon stopped short. "Jericho Foote!"

Explosive contempt seared his voice. "What the devil is a slimy Venusian swamp snake like yourself doing out here in Planets?"

Jericho Foote, President of Mammoth Exploitations and old Simeon's chief rival, blinked at him sideways. He never looked any man straight in the face. His black hair was smoothed sleekly over a low forehead. His nose was pinched and brief, his lips bloodless and thin. His smile went underground and his face darkened.

"Some day I'll have the law on you for your slanderous tongue, Kenton," he scowled.

"Run to the law and be damned! I asked you a question."

"It's none of your business," snapped Foote and went hastily past them.

Sally stared thoughtfully after him. "He must have come on the Erebus with us. In secret, too. His name wasn't on the passenger list and he kept to his quarters. Oh, Dad; maybe my hunch was right. Maybe when you turned Kerry Dale down he teamed up with Foote."

"Then he teamed up with a skulking leohippus," growled Simeon. He began to walk quickly toward the scanning booth.

"What are you going to do?"

"Har-rumph! Register, of course. When skullduggery's afoot, Simeon Kenton's not the man to run away. Come on, Sally."

THE misnamed Flash rolled and wallowed in space and made loud, complaining noises every time the rockets jetted. It was a tub, rusty and dingy with long years of service, and the odors of suspicious freights clung to the interior in spite of thorough scrubbings. The tubes were out of line and gave a wabbling motion. The struts quivered and groaned. The motors pounded and clanked unceasingly. The heavens gyrated in sympathy and danced little, erratic jigs every time Kerry Dale glued his eyes to the observation telescope.

Yet he was inordinately proud of his craft; as proud as if she had been a swift, sleek racer capable of a thousand miles a second. He owned her—every rusted bolt of her; every squeak and rattle. He was no longer a penniless young lawyer out of a job; he was a man with vested property rights; President and total Board of Directors of Space Salvage, Inc. True, he had sunk practically every cent he had in this old scow, and business so far had been exactly nil. That didn't matter. Something was bound to turn up. His nimble wits would see to that. Good Lord—the Asteroid Belt was full of opportunities. If it wouldn't be one thing, it would be another. He had drawn his charter with infinite care. There were dozens of vague, rambling clauses in it that had meant nothing to the law experts of the Vestan Filing Bureau; but which in a pinch could cover practically any contingency. He could conduct salvage operations, own and operate mines, take title to stray asteroids, barter, trade with and sell to any natives he might find on the several planets and satellites, and in general, as he had thoughtfully inserted, "do any and all things which a natural person might do, not contrary to law."

Which, as Jem admiringly observed, practically gave Kerry the right to commit murder—in his corporate entity, of course.

Jem was his second in command. He had a last name—it appeared on articled indentures, on certain police records scattered over space—but none of his intimates knew what it was. Everyone called him Jem and nothing else. When Kerry had quit his menial labors as cargo wrestler on the Flying Meteor, a Kenton freighter, because of a certain general release he had cannily extracted from Old Fireball, Jem, who had been his foreman and superior, had quit with him. Even in the hold of the Flying Meteor Jem had humbly admitted Kerry's superiority, and he had jumped at the chance to throw in his fortunes with the brilliant, resourceful young lawyer.

Right now, however, Jem was a bit doubtful of the wisdom of his course. He had dropped a good job, with a steady, assured income and prospects of promotion, for a harebrained, crazy adventure. He wasn't accustomed to spaceships that rolled as though they were old-fashioned watercraft plunging through stormy seas. It made him space-sick. And every time the rusted plates squeaked and complained, he looked involuntarily around for the nearest safety boat.

"Besides," he told Kerry, continuing his growsing monologue, "where re we getting at? Nowhere, says I." He stared resentfully out at the wabbly heavens. "We've scooted out o' the reg'Iar lanes o' the Asteroid Belt. We ain't even headin' toward Jupeeter. If you could hold this blamed tub steady for half a minute, you'd see Jupeeter way the hell an' gone over to the right."

"Right!" Kerry agreed cheerfully. "If we're looking for salvage, we've got to keep away from the regular space lanes. The big outfits have their own patrol boats there. Kenton and Mammoth and Interworld and the rest. There're no pickings for us in there. But out here, if a ship gets into trouble, it would take weeks to raise up help, and that's where we come in."

"Yeah!" grumbled Jem, squinting at the solitudes that surrounded them outside the glassite observation post. "If there was a ship, and if she was in trouble. We ain't seen or raised another boat in these Godforsaken wastes for over a week."

The Flash shifted course and drove forward like a slightly indecisive corkscrew. The starboard rockets thundered and drew protesting cries from the very bowels of the craft. Jem winced and a terrible thought grew on him. "Say-y-y! That there thing works both ways."

"What do you mean?"

"About this here salvage business. S'pose we bust down. And I ain't saying it ain't mighty likely. Who's gonna save us?"

Kerry grinned. "Let's not worry about that until it happens. The Flash is fundamentally sound. Underneath her rust and creaky joints she's got a heart of gold. She'll outlive a hundred fancier, shinier ships."

BUT as the Flash drove on and on, far beyond the usual lanes, Kerry began to grow anxious. The hurtling, crisscrossing asteroids became fewer and fewer. Mars was a tiny point of light behind and Jupiter itself lost magnitude on the right. They were driving at an angle of sixty degrees to that giant planet. Space infolded them, huge, unfathomable, frightening.

Sparks sat patiently at the open visorscreen, waiting for messages that never came. The limited range of their apparatus forbade the reception of signals from the distant traveled courses; and not even a stutter came in from the fifty-million-mile radius of effective reach. They had this sector of space, seemingly, all to themselves.

For the hundredth time Kerry took out a well-thumbed sheaf of three spacegrams, reread them. He always read them in the same order. It was a bit of a ritual.

The first was the offer from Simeon Kenton to rehire him, with the tempting bait of eventual Chief of Legal Department hinted at. It was a most satisfying spacegram, even though he had turned down the offer. So Old Fireball, who hadn't even known of his existence while he had slaved loyally as an obscure member of the legal staff of Kenton Space Enterprises, now was sufficiently aware of his worth to make him a flattering proposal. And all because he had hornswoggled the old man with his tricky knowledge of the law.

The second spacegram was also from old Simeon. This was the yelping insult to his own refusal. He grinned over it. He could read the wounded, incredulous vanity under the violent phrases. The man of power had called him impudent. Well, he had been impudent. Deliberately so. The memory of that year of unrewarded toil still rankled, and the cavalier treatment he had received when he had asked for a raise. He'd never be subordinate again; to Kenton or to anyone else. They'd treat him as an equal or he'd go on his own. And he preferred to be on his own. A lone wolf, pitting his wits and skill against the men of power and money. They had sought to use his wits and skill at law for their own benefit. They had thought to suck him dry and then cast him aside. Well, he'd show them. He'd—

He paused over the third spacegram. Slowly he read it, though he knew every letter of it by heart. "Kerry Dale, Planets, Vesta," it read. "Congratulations. Keep up the good work!" And the signature was Sally Kenton!

He remembered only too clearly the stupefaction with which he had received it. He had just mulcted her father out of a cool hundred thousand. The ordinary daughter would have been furious at the man who had done it. He had met her only once, and then they hadn't spoken to each other. He had been too busy shaking her father and telling him things. He hadn't even known she was Sally Kenton, the toast of two worlds and the darling of the broadcasters.

Yet she had sent him this extraordinary congratulation. Why? His heart gave a great bound—and subsided. He became angry with himself. He was a fool to believe she meant it; that she had a certain personal interest in him. How could she? There was something else behind it. Something devious; something to her father's interest. Well, if they thought they could overreach him, they were both mightily mistaken.

Nevertheless he placed that particular spacegram very gently back in his pocket, taking care not to crease or dirty it in any way.

He went down into the radio room. Jem was lounging there, looking glum, talking to Sparks. All radio men ran to a pattern. They were slight and wiry and dried-out and bird-like in the brightness of their eyes and the quickness of their movements. This particular Sparks was no exception.

"How're they coming?" Kerry greeted.

SPARKS shook his head with rapid denial. "Nary a thing, Mr. Dale. Not even a code message from some lovesick matey to the gal he left behind in every port o' call. Not a whisper. If I didn't check the tubes regular, I'd think the blamed machine was out o' kilter."

"I say we oughta turn back," declared Jem vehemently. "This here salvage business ain't what it's cracked up to be."

"Maybe not," agreed Kerry. "But I was thinking of other fish to fry."

"What?" they chorused.

Kerry hesitated. "Well, I had wanted to keep the idea to myself until something turned up." He grinned wryly. "But nothing's turned up, so it doesn't matter now."

"Ain't even turned up a space mirage," grunted Jem.

"The regular asteroid lanes are pretty well covered by now," explained Kerry. "Even bits of debris not more than a few yards in diameter are staked out, filed and exploited. The first space rush is over. The original prospectors are drinking away their gains or they're dead; the big outfits moved in and took them over and put exploration on a systematic, fine-comb basis. But this patch of space hasn't been gone over much. I thought perhaps we'd run into a find. Something like that nickel-iron asteroid that brought Kenton almost six millions in cash."

"So that's it, huh?" snorted Jem disgustedly. "We come out here wild-goosing for treasure. That's even wuss than hunting for distressed ships to salvage where there ain't no ships. Sometimes a boat does go off course and gets into trouble. But y'oughta knowed there ain't any asteroids out in this part o' space. There's the reg'lar belt and there's the Trojan belt way the hell an' gone off to one side, what belongs to Jupeeter. But this here place where we're now ain't neither one nor tother."

"So I'm finding out," Kerry admitted. He shrugged his shoulders. "Well, I can't be blamed for trying. Especially when I got word there was a Kenton ship nosing around these parts looking for the same thing I was."

"What?" they both yelled. "A Kenton ship?"

"How d'you know?" demanded Sparks. "They keep those exploration boats pretty quiet."

"Oh," said Kerry airily, "a few drinks of jxulla back on Planets and a second mate who'd never drunk it before. Just before he passed out he said something about blasting off the next day under sealed orders. Seems a half-crazed prospector had been picked up in midspace by a Kenton ship. He died before they came in to port and the captain screened Old Fireball for orders. When Kenton heard what the ravings had been about, he told the captain to dump the body into space and keep quiet."

"The old man's still on his toes." Jem's tone was admiring. "He don't let nothing slip by."

Kerry said dismally, "I gave them a day's start, thinking I could keep them in sight. But they were speedier than I thought. Oh, well, it doesn't matter. I suppose they didn't find anything, either. They must have turned back."

"Like we should."

"Might as well, Jem. We're beginning to run short on fuel and provisions. Better tell the engineer—"

"Hey, what's that?" yelled Sparks suddenly.

A faint wisp of sound wavered from the open screen; and a pale shadow danced like a quaking aspen over the white expanse.

"It's a message," cried Kerry excitedly. "Step up the power."

SPARKS stepped up the power, but neither sound nor shadow gained in clarity.

"Hell!" said Sparks, disgusted. "It's a private wave length. Nothing for us."

"That's what you think," retorted Kerry. "Can't you get on that length?"

"I could; but I ain't."

"Why not?"

"It's against the law to listen in on private lengths. Says so in the regulations. I got 'em right here."

"Suppose as owner I order you to."

"Still wouldn't do it, Mr. Dale," Sparks answered doggedly. "It'd be worth my license. And besides, I don't aim to go breaking no laws." Kerry grinned approval. "Good for you, Sparks. Glad to hear you talk that way. As a lawyer I don't believe in breaking laws. But there's no law against interpreting the law so it swings to your side."

"The rule about listening in is plain's can be," insisted Sparks. "There never was no getting round it."

"Oh, no? On the 6th day of November, 2273, Chief Justice Clark, sitting in the Supreme Court of Judicature for the Planetary District of the Moon, handed down a unanimous decision in the case of Berry, plaintiff-appellee, versus Opp, defendant-appellant, covering an exactly similar situation.

"'The law,' he wrote, 'is not an inelastic instrument. It may be stretched on occasion to mete out substantial justice in eases where the march of time or the failure of the legislature to provide for all contingencies has vitiated the plain intent of the specific provisions. The appeal in the instant case comes within the broad equities of such interpretation. It is true that Section 348 of the Space Code is specific in its wording and provides for no exceptions. But it must be asked, what was the intent of the Interplanetary Commission? Obviously to safeguard individuals and corporations from any encroachment on the right of privacy. A private wave length, officially registered, is as much a private right, to be held free from interference, as any primitive telephone wire or stamped and sealed letter.'"

Kerry took a breath and plunged on while his audience of two just goggled.

"'Nevertheless,'" he continued quoting, "'consider the facts. The appellee's ship was in distress on the Earth-Moon run. A leak had developed. It was losing air fast. The ship operator sent out a signal of distress. The operator, in his excitement, sent it on the private length assigned to the appellee, instead of on the standard wave. The defendant-appellant, also on the Earth-Moon run, noted through his telescope the erratic course of the appellee's ship. He heard the faint buzz of the private message. Assuming that an emergency had arisen, and acting in good faith, he tuned in on the private length. He heard the call for help and hurried to the rescue. He saved the ship and saved its crew from death by asphyxiation.

"'Now the plaintiff, in defiance of all gratitude, sues the defendant for infringement of Section 348. Judicial notice may be taken by this Court that the purpose of the plaintiff is to offset a pending claim for salvage on the part of the defendant. The plaintiff does not come into court with clean hands. The Legislative never intended this section to cover such a manifest perversion of justice. It is plain that the question of good faith must be involved. The defendant acted in good faith. The judgment of the lower Court in favor of the plaintiff-appellee must accordingly be reversed, and judgment rendered for the defendant-appellant, and costs assessed in his favor in the lower Court and on appeal.'"

Kerry took another breath. "You will find the decision reported in the Interplanetary Reporter, Volume 991, Pages 462 to 478 inclusive," Sparks gulped. "You ain't ribbing me, sir?"

"If Mr. Dale tells it to you," Jem said severely, "it's so, down to the last dotting o' the i's."

"But... but I ain't never heard o' that," Sparks still protested, "and according to what you say, that there judge wrote that more'n a hundred years ago."

"Sure it's an old case, and of course you never heard of it. Even among lawyers very few have. The precise matter just never happened to come up again. But it's there, and it's law. It's never been overruled."

Sparks shook his head. "I still don't see—"

"The whole point is one of good faith. We hear a call out in the veritable wilds of space. There shouldn't even be a ship out here.

Suppose, say we, that ship's in trouble. Suppose the operator lost his head, the same as the fellow did in that old case of Berry versus Opp. We listen in, just to make sure. All in good faith. After we've heard enough to decide we made a mistake, that he's not in trouble, we cut off." A wide grin split Jem's face. "And meanwhile we can't help it if we heard things. Kerry Dale, you've got a head on your shoulders."

"We-ell!" said Sparks, half convinced.

"Hurry up!" Kerry was getting impatient. "They'll be off the waves before you get around to it."

Five minutes later Sparks was wiping his brow. "Damned if it aint a distress call," he said huskily. "That's the Flying Meteor, Captain Ball commanding."

"Holy cats!" exclaimed Jem. "My old ship! What's Ball doing all the way out here?"

"Our old ship," corrected Kerry, His face wore a thoughtful frown. "Iron Pants Ball doesn't lose his head so easily. He's trying to raise Planets or some other Kenton ship instead of sending out a general call. Why?"

"He ain't even sending on his regular equipment," said Sparks. "He's using an assembled rig. I can tell from the power. Something happened to his sending outfit. Smashed. And he's drifting. Fuel tanks clean. He ain't saying what's happened. Funny!"

"Damn funny!" nodded Kerry. "Well, boys, this is obviously a job for us; even though Ball isn't asking. Have you got his position?"

"Yeah. Shall I contact him and tell him we're coming?"

"No. I want to surprise him." Jem chuckled. "And what a surprise! He'll be fit to bust when he sees us two."

But Kerry's frown had deepened.

"Get the engineer to shove on full speed ahead, Jem," was all he said.

IT TOOK the better part of a day, Earth time, to make the run. The Flash was no speed demon, and she complained and whined and muttered vociferously at the treatment she was being accorded. But Kerry kept pushing her grimly. His thoughts he kept to himself.

The Flying Meteor had stopped sending. "Used up their emergency batteries," explained Sparks.

Space was quiet, except for the roar of their own tubes. The detectors picked up a small asteroid, too small and too distant as yet for sight in the electro scanners. It seemed about equidistant from the crippled ship and their own. The rest of space was swept clean. Nothing for a hundred million miles.

The Flying Meteor, when it hove into sight, was drifting helplessly. Slowly, at less than a mile a second; silent, its hull dim in the faint reflection from a far-off sun.

The Flash came up fast, Kerry opened the screen, put through a call.

No answer.

Sparks whistled. "They haven't a drop of juice left. Not even for local reception. I never heard of that happening before. There's something screwy."

But Kerry was already pouring his long legs into a space suit.

"Hurry, Jem," he said. "Get into yours. You and I are going visiting."

More than thirty precious minutes were consumed in maneuvering into position and cutting down speed to get alongside. The magnetic tractors went into action. The two ships drifted together. There was a slight bump, and the plates gripped.

Kerry and Jem clumped into the air chamber, closed the lock behind them, slid open the outer port. Jem tapped out the Space Code signal on the hull of the Flying Meteor. For a moment there was no answer.

"I hope they're not dead," he said with sudden anxiety. "They used to be my shipmates. There was—"

Then the taps came. "Stand by! We're opening. Manual power. No juice left."

Helmeted, rubber-sheathed men met other space-suited individuals. Air whooshed between. Then they were in Captain Ball's quarters, shrugging out of unwieldy outfits, shutting out with swift door-closing the staring, haggard crew.

"I thought my number was up this time," came Ball's muffled voice as he lifted his helmet. "If your ship hadn't providentially come up—" He choked, stared.

"You, Jem! Kerry Dale, you!"

Jem's fingers touched his forehead from long habit. "Yes, sir." Then he grinned. "Sort of a surprise, ain't it, Captain Ball?"

Kerry said: "It's a small Universe, isn't it? You used to be on the Earth-Belt run; and we were fooling around Planets. Yet here we meet almost beyond Jupiter. Luckily for you, as it turns out. We're in the salvage business, you know. Jem and I."

Ball's eyes narrowed. "The coincidence is too damn pat. I've been running into too many coincidences as it is."

"This one happens to be a lucky coincidence, captain." Kerry pointed out. "You do need salvage, don't you?"

Ball grimaced. "Can't help myself. My fine traps are bone-dry, my radio's twisted junk. My emergency batteries smashed. If I hadn't had one stowed away unnoticed among the medical supplies, I couldn't even have—" He stopped suddenly.

"You were saying?" Kerry murmured.

"Nothing." His face tightened. "If you could let me have four drums of fuel and half a dozen spare batteries, so I can get started toward Planets and raise headquarters there, Kenton Space Enterprises will pay you well."

"You forget," Kerry said softly, "we're in the salvage business; not a refueling station."

"Damn it, man! You'll get your salvage fees. One third of the ship's value, isn't it? Mr. Kenton will pay, and gladly. I'll sign papers. Only give me the stuff—"

"One third of the cargo, too."

"All right. All right. But hurry and—"

So there was nothing of value in the cargo, thought Kerry. Then why this all-fired hurry? He shook his head.

"Sorry, captain. The laws of salvage are funny that way. No towing; no salvage. Read Section 21, Subdivision 6—"

"You're too damn technical. You know as well as I that if I say so, Kenton will back me up, law or no law."

"Still no sale."

Ball scowled. "Blast you, Dale, have it your way then. Haul me back all the way to Planets. Only let me use your radio. I want to notify my base as to what's happened."

"Do you intend to use code, by any chance?" inquired Kerry.

The captain stared. "Naturally."

"Then still no sale. I have a strict rule on board my ship. No private wave lengths or private codes may be used on my instruments." He winked surreptitiously to Jem. "Haven't I, Jem?"

That worthy looked bewildered. "Huh? Oh, sure... sure! Uh... our Sparks, he's a funny guy that-away."

"Ball said coldly: "You fellows aren't talking to a blasted landsman. Stop the nonsense and get down to brass tacks. What's your game?" Kerry was equally cold and crisp. "That works both ways. What's your game, Captain Ball?"

"This is ridiculous!"

"Oh, it is, is it? Let me run over a few things with you. The Flying Meteor was taken off its regular run and blasted off under sealed orders. I find it adrift in a sector of space where no one ever goes."

"So you followed me, eh?"

Kerry ignored that. He ticked off his points like relentless hammer blows. "I repeat, I find you adrift. Your fuel is gone; your radio smashed. You might possibly have run out of fuel, though you're too good an officer to have permitted that. But you didn't smash your own radio. Someone else did that for you. If it was a hijacker, you'd have made no bones about telling us. Yet you're holding out on us. Why?"

Ball's face did not change so much as a muscle. It was a well-schooled face. "You're crazy!" he said.

Kerry shrugged. "All right, if that's the way you want it." He turned to Jem. "Come on, Jem. Captain Ball obviously doesn't wish for our assistance. Let's get back to the Flash. I want to investigate that asteroid that showed up on our detectors, anyway. Since we don't have to tow this tub—"

BALL lost his impassivity. "You mean you're going to let us drift out here like trapped animals?"

Kerry pretended astonishment. "Isn't that what you wanted? I thought it was, since you refuse to co-operate."

"You win, and be damned to you!" the captain said bitterly. "If there was any chance of getting through, I'd see you in hell first. But I can't let my men die like rats; and furthermore, it doesn't matter, anyway. They've got a good three-day start and they've got a fast ship. Faster than mine; and certainly faster than yours."

"Ah!" said Kerry. "That's better. Now start from the beginning." Ball took a deep breath. "Well, we were hunting for something. On a tip."

"Skip that part," Kerry advised. "I know about it. Did you find it; and what happened then?"

The captain stared. "Damn!" he said with feeling. "And we thought we were very secret about it. That makes two at least who knew."

"The other being—"

"Jericho Foote, the louse! You know—Mammoth Exploitations."

"Ah!" said Kerry again. "I know. The pot's beginning to boil. He followed you, too?"

"Not that swamp snake! He's too cunning to get tangled up directly. He hired an outfit; one of those that's always hanging around the Belt looking for trouble. I didn't know they were following until I located the asteroid. They kept out of range, using their detectors. They had extra-powerful ones."

"That asteroid you were hunting," said Kerry, "wouldn't by the merest chance be the one I just picked up in my detectors."

Ball glowered. "I suppose so. There isn't another one around this side of Jupiter."

"And there you found what you were after?"

The captain hesitated.

"You might as well tell me. Fin going to take a look-see anyway."

Ball shrugged. "The whole Universe might as well know now. That poor, crazed prospector was right. It isn't a big one—not over five miles across—but she's just loaded with thermatite."

"Thermatite!" Kerry and Jem looked swiftly at each other. "What percentage alloy?"

"No percentage. It's the pure thing. And a vein as thick as a spaceship. There's been nothing like it found in the System. I think this asteroid must have come from outside. The head of a comet, possibly, caught by Jupiter."

Kerry whistled softly. Thermatite was almost pure energy. It would undergo atomic disintegration without giving off gamma rays—hence could be used in very cheap, very light portable atomic engines that required no shielding. But what thermatite had so far been discovered was so alloyed with inert materials that the expense of extraction practically made up the difference, and transmuters couldn't afford to make it. A vein of pure thermatite meant a sizable fortune to the discoverer.

"What happened then?"

Dark anger lowered in the captain's face. "We had just staked out our claim when that damned pirate came up. We didn't have a chance. Practically my whole crew was out on the asteroid, unarmed; and they had a torpedo gun trained on us. There wasn't a thing we could do but curse and watch. They erased our monuments, raised their own; took over whatever thermatite we had already mined, emptied our fuel tanks, smashed our radio, and set us adrift."

"The dirty hijackers!" growled Jem. "They might as well have murdered you all and been done with it."

"Oh, no!" Ball said sarcastically. "They said as soon as they'd filed the claim properly in their names they'd report us adrift and have Kenton send a rescue ship out for us."

"By which time you'd be dead, if they reported you," Kerry said grimly. "This Foote is a rat!"

"That's the layout. That's why I want to use your radio. I want to raise Planets and have them arrested before they file."

Kerry shook his head. "It would be your word against theirs. They would claim you tried to hijack them. Besides, my radio has only a fifty-million-mile radius. By the time we'd get that close they'd already have filed."

The captain swore. He managed to concentrate a good deal into a few words. Jem just glowered.

Kerry thought a moment.

"You took enough observations to calculate the asteroid's orbital elements?"

"Naturally. Otherwise how would we be able to find her again; or file on her? It's quite an eccentric orbit, as you'd suspect from finding her all the way out here. I've never run into any quite like it before."

Kerry's eyes gleamed suddenly. "Hm-m-m! Mind if I look at your figures?"

"Damned if I know why you want to waste your time. We ought to get started for Planets right away." Ball's fists clenched. "I want to lay hands on a few people."

"There'll be no delay. Jem, get the tractors hitched up properly for towing. I'll be with you in a few minutes."

It was with reluctance that Ball brought out his charts. But there was nothing he could do about it. Kerry had the whip hand.

Kerry studied the charts in silence, made some rapid calculations. When he finally looked up his face was wiped clean of all emotion.

"I'm going to make you a proposition, Ball."

"What is it?"

"About the salvage. The Flying Meteor is a heavy boat as well as an expensive one. Towing her won't do my tractors or my hull any good. It's worth every bit of the salvage money. And that's going to run high. One third of your ship's value, and you know what that amounts to."

The captain grimaced. "What can I do? I'm in a tight spot."

Kerry stared up at the ceiling. "You've lost out on the asteroid. Foote's gang will file, and then assign to him. He's in the clear. He'll show a check in payment and claim his rights as an innocent purchaser for value. Whatever proceeding you might have against the hijackers would be lost against him. You couldn't prove in a court of law that they were his men?"

"N-no," Ball admitted. "I suppose not. I damn well know it, but I couldn't prove it."

"Exactly. And by the time we get back, they'll have vanished. There're plenty of hide-outs among the asteroids where they can hole up until the storm blows over."

"What are you driving at?"

Kerry met his gaze. "This. I'm going to do you a favor; and Old Fireball, your boss, a favor. Though God knows I have no reason to waste favors on him, I'm going to tow you to port free, gratis, and waive the salvage charges."

Ball came halfway out of his chair, "What?"

"In return for something, naturally. There's got to be consideration for a bargain, you know; otherwise the law holds it to be of no effect."

Ball sank back. "Ha! I see!"

"You don't. All I want is a proper assignment from you, as initial discoverer and authorized agent of Kenton Space Enterprises, Unlimited, of all your right, title and interest in and to the said asteroid, duly described, and of all the appurtenances thereto attached."

Suspicion glared in the captain's eye. "You mean you want to take an assignment of something that is valueless?"

"I don't say it's wholly valueless," Kerry said carefully. "I don't want to misrepresent. I think I can get a nuisance value out of the claim. I'm a lawyer, you know."

"And a good one, captain," Jem chimed in heartily.

The suspicion died in Ball. He even grinned. This Kerry Dale, smart as he thought he was, was a fool. Giving up substantial salvage for a remote possibility. The law of filing on newly discovered asteroids was definite. Two steps were required. First, setting up the proper monuments on the asteroid. Second, filing the requisite affidavits in the Claims Office of jurisdiction. In this case, Planets. One step alone was not sufficient. Prior monuments meant nothing; the date of filing controlled. Well, if Kerry Dale wanted to take the chance, who was he to stop him! In his mind's eye, Ball could hear old Kenton's approving chuckle. The old man was pretty sore over that last trick Dale had pulled on him.

"O.K.," he said. "Prepare the papers, and I'll sign them."

"After I take a look-see at the asteroid. I want to make sure your... uh... eyes didn't deceive you about that thermatite."

The captain grunted. "Suspicious, hey? Well, I suppose you're entitled to see for yourself."

THERE was no question about the thermatite. The quivering glow of it was visible a thousand miles away. It sparkled and danced with lambent flame along a wide streak in the dull, stony jaggedness of the tiny wanderer of space.

"Satisfied now?" demanded Ball. The sight of that precious vein which was rightfully his by prior discovery embittered him all over again. Some day he'd get those birds!

"Looks all right. We're landing, though."

"Why?"

"To reset your monuments. Filing's no good without them, you know."

Let him have his fun, thought Ball sourly. Nuisance value, my eye! That skunk, Foote, won't pay him a nickel.

The ceremony didn't take long. Four metal stakes were driven deep into the stone, exactly in the niches where Ball's old ones had been ripped out. Then a photograving of claim to title was etched deep within the area bounded by the stakes. Meanwhile, Jem gleefully broke off the evidences left by the hijackers.

"Now," said Kerry, "we'll sign our documents. Here's a waiver of salvage, properly prepared, wherein I agree to tow you into port and to accept in full payment thereof your assignment of rights in this asteroid. Please sign here."

For a moment the captain hesitated. This Kerry Dale was a pretty slick fellow. Did he have something up his sleeve? Hell, how could he?

Sometimes the smartest fellows overreached themselves. With a little smile he signed.

Carefully Kerry folded the assignment, placed it in his pocket. The captain buttoned up agreement with a sigh of satisfaction. "Let's get going," he said.

"Right. We start at once, Captain Ball. If you'll get back into the Flying Meteor—"

On the Flash, Jem said anxiously: "I didn't want to say nothing, Kerry; but it 'pears to me you done yourself out of some healthy money."

Kerry grinned. "So does Ball. Well, we'll see. Meantime, tell the engineer to pull away." He thrust a paper into Jem's hand. "I've plotted our course. Give these figures to him."

Jem stared at them. He knew something about the elements of space navigation. His face showed stupefaction. "This here ain't the right—" he exclaimed.

Kerry cut him short. "I'm the navigation officer on board, not you. Please follow orders." Then, with a smile, he patted Jem on the back. "Don't worry. I know what I'm doing."

Still bewildered, Jem went obediently below.

The lifting rockets spurted. The Flash, hitched firmly to the larger Flying Meteor, groaned in every strut. The tiny asteroid fell away. They swung a wide arc in space and moved steadily off. The asteroid dropped out of sight.

Kerry settled himself comfortably to await the expected explosion.

It was not long in coming.

The visorscreen buzzed sharply about an hour later. Kerry grinned. That would be Captain Ball. He had given him a single battery for his emergency rig; enough to establish communication between the two ships; but not nearly enough to raise anything outside of a few-thousand-miles range.

He opened the screen.

The captain's apoplectic countenance appeared. "Hey, Dale," he shouted, "where the hell are you going?"

"To port, of course. Where else?"

"You're either crazy, or no navigator! I've been watching the way we're heading this last hour. You'll never get to Planets on this course in a million years."

"Who said anything about Planets?"

Ball choked. "Well, I'll be—And where the hell are you going?"

"To Ganymede City, Ganymede, Sector of Jupiter. What's wrong with that?"

The captain's face was purple and green. He shook his fist. "What's wrong with that? Nothing, nothing except that I want to go to Planets. If you don't turn at once—"

"What will happen?" Kerry asked softly.

"I'll have the law on you! Simeon Kenton will have the law on you! We'll break you so hard you'll never be able to pick up the pieces. We'll sue you for damages on the contract."

Kerry composed himself into a more comfortable position. "You mean that waiver of salvage I just signed."

"I mean nothing else. You agreed to tow me to Planets."

"Look at it. If you'll find Planets mentioned once in there, I'll not only turn around but pay you salvage."

"Huh? Well... uh... maybe it isn't mentioned. That doesn't mean a thing. Any fool would know that's the port. That's where I came from; that's where you came from."

"I agreed to take you to port; and I'm taking you. Maybe you've forgotten, or maybe you never knew, but the Interplanetary Commission itself defined the word 'port' in a decision only about two years ago. It was in connection with a salvage claim. 'Port,' it said, 'in a contract of salvage, was to be construed as the nearest port of call to the place where the tow was commenced; it being understood, however, that the said point of entry was properly equipped with repair facilities sufficient to put the disabled tow into spaceworthy condition again. Surely, my dear captain, you don't deny that Ganymede City has proper repair docks? And certainly, if you'd look at your charts, you'd notice that we're a good fifty million miles closer to Ganymede City than to Planets."

Kerry put on a reproachful air. "Why, if I took you anywhere else I'd be guilty of a serious breach of contract; and Mr. Kenton would be perfectly within his rights in suing me."

"Damn your decisions and legal twistings!" Ball roared. "It was understood we were to go to Planets. Who the hell wants to go to Ganymede?"

"I do. I have business there. As for your understanding, I'm sorry you misunderstood. Naturally, if you were so keen on Planets you should have inserted it in the agreement."

Ball shook his fist again. "I'm coming on board—"

"Not on my ship," Kerry answered cheerfully. "My space lock's jammed. I'm afraid I won't be able to fix it until we get to Ganymede. See you there."

He reached over and blanked the screen on the torrent of language that the harassed captain was letting loose.

WITHIN a week they were on Ganymede, port of entry for the Jovian System, and capital of the Sector. Ganymede City was a frontier town, rough and sprawling and alive with adventurers come to seek their fortunes on the outskirts of civilization. But Kerry wasted no time on its sordid delights. He went to the proper officials to transact the business he had in mind, and blasted off for Planets as soon as it was completed and his supplies were replenished.

Captain Ball, irascible, vowing vengeance, took off a day after him. The first thing he had done, after being released from tow in the city's drydock, was to give orders to buy fuel for his tanks and to repair his radio. His next was to hasten to the police authorities to swear out a warrant against Kerry for breach of contract, kidnaping, forcible detainer and whatever else he could think of.

The police sent for Kerry. He came smilingly and stated his case. He exhibited his waiver; reached back of the official to take down a volume of the Interplanetary Commission's decisions, turned unerringly to the proper page and showed the text to him. The official read, looked impressed, and forthwith dismissed the case.

Ball stalked out, breathing vengeance. He hurried to the office of the Intersystem Communications System and sent off a long, blistering spacegram to Simeon Kenton, Megalon, Earth. He didn't know Simeon was on Planets. Then he rushed back to the drydock and lashed the repair men to a more furious gait.

Out in space, Jem said: "Whew! I never saw Captain Ball so mad before. He'll rip the insides of his ship getting to Planets ahead of us."

"Let him." Kerry was quite placid. "I'm in no hurry."

Jem shook his head. He was over his depth. There would be plenty of grief waiting for them on Vesta. Ball was hopping mad; Kenton would be hopping mad; and what Kerry had gotten out of it, he couldn't for the life of him see.

PLANETS rocked with excitement. There hadn't been so much excitement in that usually turbulent town since a section of the roofed inclosure had broken half a century before and exposed the population to the vacuum of space.

First a rakish craft had come into port, bearing all the marks of a long, fast journey. Tough-looking eggs had disembarked and hurried straight to the Claims Office. Filings were supposed to be confidential; but a clerk told a friend, who in turn told another, and within six hours the whole town buzzed with the discovery of a wandering asteroid worth a couple of dozen millions.

Twelve hours later there was more news. Jericho Foote had filed an assignment of the claim to himself, and the strangers had blasted off hurriedly without bothering to attend to the necessary formalities attending ship departures. The same clerk started this bit of information rolling also.

Jericho Foote met reporters with a modest air. Yes, he purchased the rights to an asteroid. Well, of course, there was supposed to be thermatite on it. How much? Maybe a couple of millions; it was hard to say. Did he know the strangers who had discovered it? No; never saw them before. But they had come to him with the papers authenticating their find, and some samples. The assay showed 07.24 percent purity. They seeded money in a hurry, and they offered the asteroid for sale. Why hadn't they gone to Simeon Kenton as well? A twisted smirk gloated on Foote's face. He didn't know; maybe it was because his reputation was better. The reporters took this down and whistled under their breaths. When Old Fireball would hear of this, there would be fireworks. Would Mr. Foote care to tell for publication what he had paid? Why, of course, boys. He showed them a canceled check, made payable to bearer. The check was for one hundred thousand dollars. He didn't tell them, naturally, that this was the price for hijacking Captain Ball.

When the news hit old Simeon he was stunned. So stunned that for an unprecedented five minutes he lost all flow of language. Sally couldn't understand his reaction. He hadn't told her about the Flying Meteor's secret mission; nor that part of his reason for coming to Planets had been to be on the spot for first news of the venture. She herself had wandered around the roaring town, feeling curiously empty and unsatisfied. Several weeks had passed and there had been no report from the salvage ship, Flash, nor from its owner-captain. Why she was staying on she didn't know. Yet every time she determined to take ship back to Earth her will gave way and she weakly remained.

"Why, what's the matter, Dad?" she exclaimed anxiously. She was alarmed over her father's sudden, choking, empurpled silence. "Just because that man, Foote, hints his reputation is better than yours is no reason for you to risk apoplexy. Everyone knows—"

Simeon found part of his voice. "It isn't that, Sally," he said hoarsely. "It's about Ball and the Flying Meteor."

"What about them?"

He told her then; of the dying prospector and his half-delirious story, of the secret expedition of the Flying Meteor. "I can't understand it," he concluded. "That there asteroid to which that louse, Foote, got an assignment is the very same one that Ball went after. And Ball should've been back by now.

There's funny work afoot, and I mean Foote."

HOW funny the work was, showed up three days later in the form of a long spacegram from Ball on Ganymede City, relayed from Earth. There were two portions to the spacegram, and both of them unsealed all of the explosive possibilities that dwelt under Simeon's mild-seeming exterior.

Even Sally had never heard him go on like this. For a solid half-hour he coruscated and sizzled. His language lifted the temperature of the hotel room by ten degrees. His epithets were triumphs of twisted word compoundings. For five minutes he'd devote himself to the slimy, subterranean, hell-spawned Foote. Then, for five minutes more he'd devote himself with equal expertness to a certain ding-danged, balloonheaded, smart-Alecky young feller by the name of Kerry Dale. Then he'd return to his characterizations of Foote.

Sally knew her father; knew it was no use to try and stop him when he was in this vein. Instead, she read the code spacegram that had touched him off. It spoke for itself. Hot fury assailed her at the first part; puzzlement at the second. It wasn't like Kerry. From what she had seen of the young man he didn't do things out of sheer nastiness. Always he had gained by his tricks. His was a hard, realistic code of ethics; but so was her father's. They each recognized in the other an antagonist worthy of his steel; and secretly they admired and respected each other.

But this stunt of hauling the Flying Meteor to Ganymede instead of to Planets and thereby ruining whatever slim chance there might have been of bringing the hijackers to justice didn't make sense. Neither did his waiver of the substantial salvage fees to take up an assignment of a claim that he surely must have known wasn't worth a cent.

Old Simeon finished with a resounding burst of oratory that started curls of smoke in the cushioned sofa. He picked up his walking stick—a flexible, ornamented bit of duraluminum—shouted to his daughter: "Send a spacegram to Roger Horn to come here right away. Tell him to charter a boat; a whole fleet of boats, if necessary. It's about time that stuffed windbag starts to earn the fees I'm paying him." Then he was gone.

He met Jericho Foote in the hotel lobby, surrounded by reporters, still hot on the scent of the story.

"Oh, oh!" murmured one of them to his fellows. "Here comes Old Fireball and there's that certain look in his eyes. Watch this. It's going to be good."

How good it was going to be even the hardened reporters did not know.

Old Simeon moved swiftly through them, paying no attention as they scattered from his path. Jericho Foote rose to meet him. A slight alarm assailed him, but it passed. After all, there were plenty of witnesses around.

"Well, if it isn't Kenton!" he exclaimed. "You're looking—"

Simeon said nothing. He lashed out swiftly with his cane. It caught Foote on the shoulder. He staggered back, crying out. Simeon followed relentlessly. Thwack! Swish! Crack! The cane whistled and sang about Foote's ears, slashed his body, cut down his upflung arm, thumped across his back as he turned to flee. Foote screamed for help, yelled for mercy. But still the cane sang and danced. It was whispered later that the reporters did not interfere until Foote had been soundly and thoroughly beaten, and then only because, after all, they didn't want actual murder committed. They didn't like Foote.

Foote was carried to bed and Kenton sallied triumphantly into the street. Foote commenced action against Kenton for fifty thousand dollars for assault and battery with a dangerous weapon and intent of mayhem. Kenton counterclaimed with a demand for one hundred thousand dollars damages for slander and innuendo that his, Kenton's, reputation wasn't all that it might be. Planets rubbed its collective hands and looked forward with glee to a fine summer.

ROGER HORN and Captain Ball arrived almost simultaneously; Horn puffing and gasping from the urgency of his call, the captain burning with desire for revenge against all and sundry.

Horn listened and hemmed and hawed. When the captain was through he looked worried. "Of course... hem... we have a good cause of action against these... haw... hijackers; if they can be found."

"To hell with them!" yelled Simeon. "I want you to get that asteroid back and get that Venusian swamp snake, Foote, in the bargain."

Horn cleared his throat. "Well, in the first place," he said judicially, "Captain Ball admits he can't prove in a court of law these... hem... scoundrels were hired by Foote."

"I can't," Ball growled.

"Therefore, Foote is an... ahem... innocent purchaser for value, and whatever claim of forcible entry and detainer may be alleged against his... ah... sellers cannot be imputed to him."

"Dadfoozle it!" shouted Simeon.

"I didn't need you to tell me that. Any law apprentice could've told me the same thing. I'm paying you disgusting sums to tell me how to get things done, not why it cant be done. I'll bet that scaddlewagged Dale would've—"

Horn winced. Damn Dale! He was sick and tired of hearing his name thrown in his false teeth every time. Then he brightened. He put on an air of dignity. "Speaking... ahem... of this... ah... young Dale, you lost whatever claim you might have had on the asteroid by assigning your rights to him. I have examined the document, Mr. Kenton, and I assure you it was properly drawn."

Simeon deflated. "Huh? Yeah—I suppose so." Then he, too, brightened. "Anyway, dadburn him! He outsmarted himself this time. Salvage would have amounted to a hundred thousand. Instead, all he's got is a worthless assignment." He turned suddenly on Horn. "You're sure, though, it is worthless?"

"As sure as I am of anything. I'm willing to stake my reputation—"

"Huh!" Old Simeon's snort was plainer than words. "Then how about getting after him for towing Ball to Ganymede?"

"Well... hem... I'll have to consult my books—"

"You won't have to," Ball said bitterly. "Dale consulted them before he started. He found a decision which permitted him to head for the nearest port, which was Ganymede City. You'll find it, my dear Mr. Horn," he added with biting sarcasm, "in the Decisions of the Interplanetary Commission, Volume 53, Page 209."

"But why did he take you there?" demanded Sally. "He lost by it as well as you. Didn't you say he's on his way here now?"

"Yes; and I don't know, Miss Sally."

Old Simeon regained his elastic good humor. "Just pure spite, my dear," he chuckled. "He found out he'd made a foolish bargain, and he took it out on the captain. After all, losing a hundred thousand in salvage would—"

"By this time, Mr. Kenton, you ought to realize I do nothing out of spite."

THEY all whirled. The door had opened silently.

"Kerry... Mr. Dale!" gasped Sally, surprised at the way her heart thumped. "When... when did you arrive?"

He looked leaner and fitter even than that single time she had seen him before. Space life agreed with him. He carried himself easily and there was a sureness about his movements and speech.

"About five minutes ago. I took an aerocab to beat the news. And just stick to Kerry. I like that better from your lips, Sally."

Simeon glared at him. "Harrumph! You have a nerve coming to me after the dirty trick you played."

Kerry became curiously humble. "That's why I came, Mr. Kenton. I felt... uh... under the circumstances it was no more than right that I make you a proposition."

"I'm not interested in your propositions, dingblast you!"

"Wait till you hear it. I'm willing to give you half of my assigned rights in the asteroid provided you pay me the full salvage on the Flying Meteor."

Old Simeon chuckled. He was in high good humor. "You're slipping, son. I'm really disappointed in you. I thought you were a young man who knew his way about." He shook his head sadly.

Kerry pretended surprise. "I don't understand, sir. Half of that assignment is worth—"

"Exactly nothing. No, son. You were too smart for your own good. You dropped the salvage money and I'm going to hold you to it. A contract is a contract."

"That's your final word?"

"Absolutely. Business is business."

"Good!" Kerry's countenance cleared. "I confess I did feel a little conscience-stricken, but you yourself tell me business is business."

"What do you mean?"

Kerry grinned. "Captain Ball may remember I checked the elements of that little asteroid before I offered to waive the salvage."

"Come to the point."

"The point is simple. Asteroid X is not, as everyone hastily assumed, a member of the Asteroid Belt. It's really a Trojan asteroid, though an unusual one. For, while it fulfills the classic conditions of the Trojan group in that it moves along a stable orbit which is equidistant from both Jupiter and the sun, it lies apart from the ones we have hitherto known—such as Hector, Nestor, Achilles, Agamemnon and the rest. In fact, it swings altogether on the opposite apex of the given equilateral triangle."

"What the ding-ding difference does it make what group it belongs to?" said Simeon impatiently. "An asteroid is an asteroid."

"In one sense, yes; in another, no. The regular asteroids make up an independent system. The Trojans depend wholly on Jupiter. The Trojans, Jupiter and the Sun all together give one of the known special solutions of the three-body problem. The Trojans, in effect, are satellites of Jupiter. Their orbits would go haywire if Jupiter's influence were ever removed. And that means, my dear sir, that the regional office having jurisdiction over Asteroid X is not Planets, on Vesta, as all of you thought—including Foote's pirates—but Ganymede City, which assumes charge of the Jovian System." They all spoke at once. Sally cried: "I see it all now!" Horn puffed like an ancient engine. Ball said "Damn!" with concentrated intensity. And Simeon roared: "That's why you dragged my ship all the way to Ganymede, you young snapperwhipper! So you could file that claim you swornhoggled me out of."

"I offered to split with you at bargain rates," Kerry said calmly. "You refused the offer."

"He's right," said Sally. "You did yourself out of a good thing by being too suspicious."

Simeon glared at her; glared at Kerry. Then he threw back his head and laughed until the tears trickled down his wispy beard.

"What's so funny, sir?" snapped Ball.

"That Dale beat me again. But I don't mind it so much thinking of Jericho Foote's face when he hears this. Even in bed he's been gloating. He spent a hundred thousand on his blessed pirates; and all he's got in exchange is a good caning."

THE door swung open again and Foote hobbled in. One arm was in a sling; his face was puffed and swollen; and he required a cane for support.

"Evidently Mr. Foote has already heard the good news," Kerry announced calmly. "I sent him a note as soon as I landed."

"You... your tricksters!"

screamed Foote. "I'll have the law on you. My hundred thousand! My asteroid! My arm! You can't get away with this—"

Kerry stepped up to him. His voice was dangerous. "Careful what you say, you old billy goat. You forget I landed on the asteroid. Your hirelings were so anxious to get back to you with their plunder that they left a bit of evidence behind. Something that belongs to you."

Foote shrank back in alarm. "It... it ain't so. They didn't dare... I mean, I don't know what you're talking about. Lemme see it!"

"You'll see it fast enough in court," Kerry assured him ominously. "On the very day, in fact, that your case against Mr. Kenton for assault and battery comes to trial."

Foote's face tried to wreathe itself into smiles and failed ignominiously. "Heh... heh! I was maybe a bit hasty. After all, I'm willing to let bygones be bygones."

"You mean—you'll drop the action?"

"Well... that is... if—"

"If I don't produce my evidence. O.K.! You sign a discontinuance and release, and I'll promise to keep what I've got out of public hands. But if at any time you—"

"I'll sign!" Foote croaked eagerly. "I think," said Kerry, "Mr. Horn, as Mr. Kenton's attorney, is capable of drawing such a simple little document."

Horn said pompously: "Young man, I—"

"Sit down and do it without palaver," Simeon rasped.

The lawyer sat down without another word and his pen made slow, dignified movements on a sheet of paper.

Foote snatched it tremblingly from him, and signed it without even reading the contents. "There!" he quavered. "Now how about that—"

"You have my word." Kerry's voice was awe-inspiring.

"Yes, of course; of course! Well, good day; good day to you all." And Foote hobbled out faster than he had come in.

Simeon cleared his throat. "Harrumph, young man. I didn't want to interfere, but I think Foote belongs in jail. If your evidence—" Kerry grinned. "Evidence? Do you think I'd have bargained to withhold evidence of a felony if I had any? I'm a lawyer, sir. I don't compound felonies."

"Then... then—"

"Not a scrap did I find. Sheer bluff, sir. And a guilty conscience on the part of the estimable Foote."

"Well, I'll be didgosted!"

Kerry bowed. "There's a bit on my conscience, too. After all, I did do you out of a valuable asteroid."

"Don't mention it, son. I'll do the same for you yet. No man ever got the final best of Simon Kenton yet."

"Here's hoping. But in the meantime I still have my conscience." His glance rested on Sally. "If Miss Kenton could be induced to help me spend some of my ill-gotten gains in town this evening, I'd feel I'd made some reparation."