RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, November 1937,

with "Lost in the Dimensions"

Instinctively, he knew that the lambent sphere

controlled the incandescent column—

Which explains why Roger Bacon's ideas were so in advance of his time——

THE unnamed box canyon was ideal for the purpose of Childs Peartree's frightening experiment. It buried itself into the remote reaches of the Peacock Range at the western tip of Arizona. On three sides it was inclosed by cliff walls that rose sheerly to heights of over a thousand feet. On the fourth side a corps of native workmen, under the direction of Fred Walcott, his young, hard-bitten assistant, had erected a stone barrier that blocked off effectually all possible curiosity seekers, if any there might be who would be tempted to traverse the fifty miles of intervening desert.

For almost a month the perspiring laborers had transported by pack-mule trains from the nearest railhead tons of strange equipment, queer machines at the sight of which they devoutly crossed themselves and mumbled hasty prayers. The canyon at best had an unsavory reputation among the superstitious Mexicans.

But the prospect of high wages and the heartening presence of an obviously competent and muscular young man like Fred Walcott held them to their tasks. They prepared the central platform, the bases for the dynamos, the small but super-powerful electrostatic machines; they helped set up the long blue vacuum tubes, the spectral wave troughs, the giant hyperbolic deflectors, the magnetic gravity-compensating coils, the vibration dampeners, and other novel instruments evolved by Peartree for the sole purposes of this culminating experiment.

They also helped string wires over the face of the precipitous cliffs, bringing surges of power from the canyon floor to the myriad reflectors that rimmed the high edges and made an inclosed cup of the canyon itself—a cup that would soon fill to the brim with Peartree's experiment.

Finally all preparations were complete. The workmen were paid off and left most willingly. Fred Walcott they could understand—he might have been a young mining engineer, accustomed to the outdoors, bronzed with much sun. The girl, Anne Howard, was also explicable in a fashion. Perhaps she was the old man's daughter; she obviously was in love with the younger man and he with her. She was beautiful, they agreed gravely among themselves, with her bright-blue eyes, her hair that shamed the sun with its glow, her firm, oval chin and slim, straight body which the whipcord breeches and white shirt flaring at the neck set off with gracious regard. Of which at least half was true. She was beautiful, and the sparks needed but the proper channeling to leap in open flame between the young man and the young woman.

But she was not old Peartree's daughter. She was his secretary, his buffer against the world, his assistant in the minor details of the laboratory, and very competent in all her protean capacities. It was only at her own vehement insistence that the two men had reluctantly permitted her to come along. The experiment they were contriving was most dangerous.

It was Childs Peartree himself, however, who excited the fearful regard of the Mexicans, and was the motivating reason for their haste in clattering away immediately on receiving their pay. To their superstitious eyes he was the high priest of all these strange goings-on, the only begetter of this fantastic machinery.

He was old and dried, like a leaf in the fall. His hands trembled with impatient eagerness; his hair was white and unkempt; his eyes pierced them with unendurable luster.

How were they to know that the name of Childs Peartree had been a power in the world up to three years before, when he had voluntarily retired from university honors to devote himself with a unified fanaticism to this last and greatest research of his life?

WHEN the hoofs of the departing mules faded into the silences of the surrounding mountains, Fred Walcott straightened from the final unnecessary tightening of a bolt, swept a last swift glance around the tiny canyon with its towering walls and rimming reflectors, said somberly, "I still think, Peartree, this is no place for Anne. If the experiment should succeed, the consequences may be incalculable. Even if it doesn't, you're setting loose some mighty dangerous forces."

The girl faced him furiously. "We've been through that before," she said. "I'm staying."

Old Peartree shrugged thin shoulders. "You see, Fred, I can't do a thing with her. And"—he smiled one of his rare smiles—"I don't think you can. either. Anne has a will of her own. Besides, there's nothing to worry about. This central platform on which we stand will protect us from harm. It is shielded. I have labored the mathematical equations and the areas involved to the last millimeter."

Fred shook his head stubbornly. "It's still a desperate gamble. Look what you're trying to do. You're attempting to clear a definite segment of space from all matter, all energy of whatever origin. Such a condition exists nowhere in all the universe. Even in the remotest sections of intergalactic space there exists an infinite interplay of light waves, electromagnetic surges, atoms and molecules of matter, free electrons, cosmic rays. According to the latest refinements on Einstein's original theory, space time itself is but a function of matter and its concomitant, energy. Remove the latter, and space time has no meaning. Perhaps it even disappears altogether."

The old scientist's eyes glowed. "Exactly," he agreed eagerly. "My own formulae point to the same conclusion. That is why I devoted the remaining years of my life to this crucial experiment, invented the machines that would divorce space of all its attributes, even the integral one of gravitation. It may be we shall pierce the ultimate secrets of the constitution of the universe."

"More likely," Fred avowed gloomily, "we'll blast ourselves out of existence in the attempt."

Anne said, with a certain amount of repressed pain, "If you are afraid, Fred, your horse is tethered outside the canyon."

He looked at her a moment, his eyes dark with anger, his lips tight and hard. Then, without a word, he stepped upon the shielding platform beside them, pushed down with bitter strength upon the master lever.

The girl started toward him, remorseful. "Fred," she gasped, "I didn't mean that——"

But it was too late. The die had been cast, the deed done. The experiment, for good or ill, was on its way!

Anne swung around with a startled cry. Fred's eyes widened in spite of himself. Peartree leaned forward, shaking as with ague.

AT THE down swing of the lever, the conglomerate of machines had flared into mighty being. The canyon buzzed with a million bees. The dynamos whirred and spun; the tall vacuum tubes flamed with multicolored lightnings; the electrostatic balls crackled and sparkled; the down-tilted reflectors on the cliff walls blazed with unendurable stabs of light.

A huge rainbow appeared suddenly, spanned the arc of the box canyon. The spectral colors surged and eddied, flashed with giant streamers to a dazzling brilliance.

Then everything faded, slowly but surely. Gravity flattened out its warping contours; all matter died within the prescribed area; the air went out with a soft whoosh; parts of the abutting cliffs, unwarily inside the zone, vanished into nothingness. Sound and heat went with them, electric impulses later, and, last of all, reluctantly, light. The rainbow gasped out its paling luster; the mountains disappeared from view—then, with a final rush, the world seemed to come to an end.

Nothing existed any more, neither time nor space nor light nor motion—only a tiny platform with its still buzzing machines, its three paralyzed occupants, its puny shield of force that guarded it from the enveloping blankness. It was a precarious island in the illimitable inane, a spot, of light and life and energy in a frozen nothingness.

The experiment had been a success!

Anne clung suddenly to the tall, lean young man at her side. All her valor was gone. This was more terrible than anything she had imagined. "Fred," she whispered, "I'm—afraid."

He might have retorted on certain biting phrases she had used, but he was beyond irony. He held a sickish feeling within him. Suppose what Peartree had done was beyond redemption. Suppose the process were irreversible, in spite of his confident assurances to the contrary. Suppose they were marooned forever on their island platform, doomed to await a slow and horrible death. The air that beat within the inclosing shield of force could last at the uttermost for a few hours.

Beyond that rim he could see nothing. It was black with a blackness beyond all human conceiving. No tiniest ray of light could penetrate that profound void, no faintest wave of energy stirred in those moveless depths. They were cut off from the rest of the world, from the universe of familiar things, more effectually than if they had been suddenly transported to the remotest galaxy. The thought stopped his heart, thickened his blood. He knew that a hundred yards to either side Earth still existed—matter, sunshine, heat, energy. But no life, no matter, no wave motion, could traverse that paltry distance. It was the perfect vacuum, the utter non-being that no human mind had heretofore conceived.

Childs Peartree's voice rose startlingly in the stillness. It was curiously bitter with disappointment. "Damn!" he said. "It's only a vacuum. I have emptied space, but the fundamental stuff of space time still exists." He sighed wearily. "All my theories were wrong. My life work has collapsed."

Fred stared around that inclosing wall of blankness. "How do you know space time exists out there?"

"Because," the old scientist retorted with asperity, "my equations call for no such thing as this featureless void. They demand, in fact, the appearance of a new space time. On the removal of our familiar four-dimensional continuum we should have been transported into a different series. I had hoped that we might even find a new universe, a new life, in that ultra-dimensional continuum beyond our own."

"Good Lord!" Fred cried. "You never told us; I never dreamed——"

Peartree averted his gaze. "You might have backed out if I had," he mumbled. "And I needed your help, and the help of Anne."

Fred was appalled; He had known that Peartree was ruthlessly fanatic in the name of science, but not to this extent. In the furtherance of his experiments he had been willing to sacrifice not only his own life, but the lives of others. Transportation to another dimensional space indeed! A trip from which there would have been no returning. Not, he told himself carefully, that he would have held back if the truth had been divulged to him; but to bring Anne along!

Peartree saw the gathering thundercloud, spoke hastily. "It does not matter now. I have failed. You may as well reverse the lever, stop the machines. I can study this silly phenomenon I have accomplished," he continued with quiet bitterness, "in the private recesses of my laboratory. I did not need all this space."

Unaccountably, Anne Howard was at his side. Her slender arm patted his drooping shoulder. "Please don't despair," she begged. "Perhaps you didn't evacuate space completely. There may be a tiny flaw in your calculations that can be rectified. And next time"—she threw a defiant glance at the young man—"you can count on me to go along with you—even into that ultradimensional universe."

FRED caught hold of the lever savagely. Just like a woman, he raged. She chose deliberately to misunderstand his motives, the reason for his obvious anger. Very well, then. His grip tightened; he started to swing upward. Almost he hoped, and cursed himself for a fool in so hoping, that there could be no return.

Halfway toward the locking notch, however, his fingers froze.

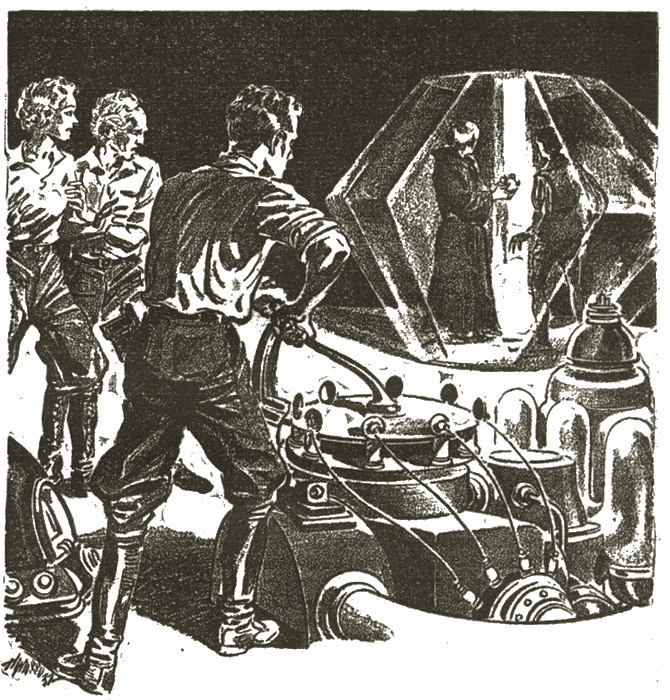

Out of the impenetrable black that surrounded them, hurtling into the field of warm illumination, materializing on the farther bare-swept end of the platform with not the tiniest thud, was a hive-shaped structure of gleaming crystal.

Two men stood within its shining depths, two men of strange demeanor and stranger costumes. The older one's brown, skinny hand clutched with desperate grip at a tiny sphere that writhed like a snake over a central column of incandescence. He was old and worn, with gray locks and peppered beard. His face was lean and hawk-like, his nose long and narrow, his lips bitter-bitten. Lines of harsh experience etched his forehead and hollowed his cheeks. A gray single garment enveloped his spare body, held around the middle by a woven cord. Dusty sandals shod his bare feet.

His companion was much younger, a mere lad, in fact. Light-brown ringlets framed his rounded, smooth-skinned face. A leather, tight-fitting jerkin, long, brown stockings up to leather breeches, and pointed shoes completed his attire.

They had not seen the platform upon which they had dropped out of the void; they had not noted the startled occupants thereon. Their heads were twisted backward over their shoulders, toward the featureless space from which they had emerged; and old eyes and young alike held a desperate, haunted terror. The lean fingers crawled over the sphere, started to twist.

Fred jerked out of his reverie, lunged forward with a shout. Instinctively, he knew that the lambent sphere controlled the incandescent column, that a further twist would send the strange mechanism catapulting from their world into the night of other space from which it had come. Peartree's experiment had been only too successful.

The youngster whirled on his pointed toes at the shout. There was a dreadful fear in his eyes. Then they widened in mutual amazement. He cried out sharply to the older man.

The gray-garmented one's hand trembled irresolutely, fell away from the orbed control. He swung and stared.

Peartree said very rapidly to himself, "Oh, my Lord!"

Anne cried out, "Fred, come back! They may mean harm!"

BUT Fred Walcott feared no man or beast, though they had come like plummets from another world. He sprang close to the hive-shaped crystal. It was of a material he had never seen; it was not of earth. He cupped his hands, shouted, "Do not be afraid. We are friends!" Then, suddenly, he felt sheepish. What would these strange visitants know of English?

Wonder filled the old man's face to the brim. The dread vanished from his eyes. "A miracle! A miracle, O John, son of Dominick!" he said hoarsely.

"These are men like ourselves; they speak our own patois of England."

The lad crossed himself devoutly. "Yet they are fantastically dressed," he objected. "It is incredible, master, that we could have returned. It is but another enchantment of the arch enchanter, Mardu—the foul fiends seize and rend him limb from limb."

"John, son of Dominick," the old man returned severely, "how often have I told you that Mardu is no enchanter, that he is the fiend himself, come from a hell beyond the seven crystalline spheres; that Heaven itself knows naught of him."

Childs Peartree merely gaped. He was beyond words.

Anne firmed her slender shoulders, pushed herself by a feat of will to Fred's side. "Are you sure we are not dreaming?" she whispered in seared accents.

The young man clenched sweaty palms. "That," he said harshly, "is the speech and dress of medieval England." He stared at the older man, at his gray garment, and the sweat broke out on his forehead also. "Anne!" He gripped her arm. "There was only one man in all that time who could have——" He broke off, raised his voice.

"Who are you?" he shouted. "What are your names and where do you come from?"

The old man said quietly: "If ye be in truth what ye seem, then are we rescued from Mardu and a doom more dreadful than any mortal could have encompassed. My name is only too familiar, stranger. I am Roger Bacon, Friar of the Franciscan Order, and this is my trusty lad and assistant, John, son of Dominick. But tell me, who are you, and what means this queer platform and its curious apparatus that partakes of the alchemical?"

Fred groaned. "I was afraid of this, Peartree. You succeeded beyond your dreams. You broke down the wall of space time that surrounded us, and somehow switched Roger Bacon from thirteenth-century England into our day and age."

The scientist was a taut, quivering bow. "Roger Bacon!" he repeated huskily. "The greatest of the medieval scientists! The man who prophesied the airplane, the automobile, the telescope. By Heaven, there is more to this than a mere transposition, Fred! No wonder he knew so much. He had discovered the secret of time travel." He gesticulated frantically. "Bacon, come out! We have heard of you, but not as you think. Your name appears in history as the first modern."

The Friar's eyes were puzzled. "In history?" He pondered the phrase. "In truth have we been so long gone that we are deemed dead?"

"A mere matter of over six hundred years," Peartree assured him. "This is 1937 Anno Domini, and this land is America, wholly unknown in your own time."

John, the son of Dominick, fell on his knees and prayed fervently. "This," he cried despairingly, "is the foul Mardu's revenge. I shall never see my own peaceful village again, with the fat kine wandering by the stream, nor the yellow locks and impish smile of Catherine that is like to tear my heart straight from the body."

"Hush your idle prating," Roger Bacon said severely. "This is matter we must understand." He twisted the squirming ball slightly. The central column flared to purple hue. The wall of the crystal inclosure seemed to vanish. He gathered his long gray robe of the Franciscans about him, padded out on sandaled feet. The lad followed more reluctantly.

"Now explain," he demanded with a philosophic calm.

THEY did, Childs Peartree and Fred and Anne, with quick, staccato phrases and hurried words. Much of it was obviously beyond the comprehension of the medieval man—space time, divorcement from matter and energy, warps, Einsteinian universe, modern geography and civilization.

But Friar Bacon seized on ultradimensional theory, nodded his head. "Of that," he declared with somber emphasis, while young John shivered, "I know much. We have been through many dimensions, beyond the crystalline spheres themselves, seeking escape from Mardu, seeking always a return to my own prison cell."

Then he explained.

"My story," he avowed, "is a strange one, even as this marvelous tale of yours. Because of my ponderings on alchemy, because of searchings into the things of nature, and not of Aristotle, Bonaventura, General of the Franciscans, placed me under surveillance in the Chapter of Paris. But in my cell, through the aid of this lad, John, son of Dominick, and the secret benevolence of one or two of the good Friars, I continued my experiments."

He stared at the banked instruments on the platform in frank puzzlement. "I know not how it happened. But something I did, or some combination of things, brought a void about myself and John even as this. We trembled. We trembled even more when this curious contrivance"—he indicated the hive-shaped traveler—"broke suddenly through the veil, precipitated itself at our feet. It held a demon within, black and hideous beyond conception."

"Satan himself," John muttered and crossed himself in fear.

"Perhaps," the Friar agreed. "We never were able to discover the truth. He spoke to us only in signs. Nevertheless, it seemed he had come from a distant place, beyond the heavens themselves, and there were more of his kind in that far-off land."

"A dweller in an ultra-dimension," Peartree breathed with repressed excitement.

"I have seen many such"—Bacon nodded—"but not such as he. But to continue. He treated us with manifest contempt, as if we were worms too poor for his feet to crush. He quit his shining conveyance, prowled around my cell, fingered my retorts and crucibles as though they were mere childish playthings."

"And all the while," the boy interjected, "I groveled in an agony of dread for my immortal soul."

Roger Bacon smiled. "I feared not for that," he said. "But there was an arrogant cruelty about the demon that minded me we would not escape alive from his clutches. I was not prepared to die. Furthermore, I always was of a mechanical, foolishly daring bent. I had noted what the black creature had done with the little gleaming 'sphere when he slowed down and thrust open the wall. I was sorely tempted.

"Even as he turned, having sated his curiosity on the poor contents of my cell, I thrust John, son of Dominick, headlong into the cage, sprang after. There was a huge cry—a scream not of this Earth—filled with a fury and venom that are indescribable. Flame shot forward toward me. I verily believe had it touched my body I would have crisped to a tiny cinder. But already my hand was on the hovering sphere. I twisted it desperately. Even as the flame darted out, the crystal wall misted over; the cell and its howling occupant disappeared, and we were enfolded in unutterable darkness."

HIS hand shook as it wiped his forehead. His head turned uneasily toward the surrounding void. "What happened after is a hideous nightmare. I mastered somewhat the control of the gleaming ball. At times we found ourselves unawares on worlds beyond our knowledge. One was red in color, parched and drear. Great canals tapped the water through the deserts. But the inhabitants drove us off with hurtling lightning bolts."

Fred breathed hard. "Mars!" he whispered.

"Then night, inclosed us. again. When it cleared, our conveyance tossed as though it were a feather in a seething cauldron of flame and fury. Another instant and we had been molten specks. But luckily, in the last gasp, I turned the ball."

Peartree shook violently. "Good Lord! They must have broken through space into the Sun!"

Roger Bacon said gravely: "I know not where it was, unless it were in hell itself. But then, as the black mist lightened again, we were in a world of metal. There was neither up nor down, nor side to side. Everything revolved and writhed and contorted in ever-changing shapes. Monstrous things hemmed us in, all of metal angles, and they shifted and retracted shapes and size even as we watched aghast. They were not human, yet they seemed endowed with life, Heaven forgive me for the sacrilege."

"It was there that Mardu caught up with us," said John.

"But how could he?" Anne protested. "You were in a different dimension; you had left him stranded back in thirteenth-century France."

"He had built himself another conveyance," the Friar explained. "Perhaps there were materials in my laboratory he could use. Yet it was our salvation that the crude materials of our world are not like the subtle elements he employed in this first incandescent column. What he made up in skill, he lost in the greater efficacy of the ship we stole. Nevertheless, he almost got us. We hurled ourselves into the void between the dimensions just in time. "Mardu!' he shouted after us in an ecstasy of rage. Whether that be a tremendous curse, we know not. We have called him ever since by that word."

"But if you lost him," Anne protested, "why were you so dreadfully afraid when you broke through to us?"

Friar Bacon smiled sadly. "We did not lose him. Always has he been on our trail. In universe on universe he follows us, like a hunting dog nosing a hare, like a falcon winging a drumming partridge. And always we escape by the merest hair-breadth, because our shining ball turns faster, our central shaft of flame is more subtle in its workings."

"He will catch us yet, master," the boy said with conviction.

The Friar's eyes darkened. "Never!" he affirmed with sudden energy. "Know ye, sirs and lady," he addressed the three, "this chase has been the greatest since Michael and his angels pursued the devilish hordes through tumbling chaos to hell. We have seen worlds and sights beyond the power of mortal tongue, we have been in places that Heaven itself knows nothing of; yet always we try to return to our own cozy time and the pleasant Earth with which we are familiar." His face saddened. "For the moment I thought that we had succeeded."

"Stay with us," Fred advised. "This is the nearest approach you may ever get. And once I reverse this lever and dissipate the ultra-void with which we have surrounded ourselves, you will be safe from Mardu, your pursuer. There will be no break in our space time for him to span."

"And I," Childs Peartree spoke up suddenly, "will utilize that strange machine of yours for purposes of my own."

"What purposes?" Fred demanded sharply.

The scientist's eyes were burning torches. "Why, to visit these vast other dimensions of which they speak, to survey all universes entire, to seek the secret of creation at its very source. What nobler, greater task "has ever awaited mortal man?"

"But you will never return," cried Anne.

"Bah! I do not wish to. Earth is but a small, dusty ball after all."

"You forget," said Fred quietly.

"Mardu!"

"I'll chance him," Peartree retorted, and started for the conveyance of shimmering crystal with its shining inner column of flame.

Fred jumped after him with a curse. He'd save the old fanatic from the consequence of his reckless enthusiasm by forcible means if necessary.

But it was John's terrible cry that stopped them both dead in their tracks.

Fred whirled. His hand streaked to his belt, where a .38 Colt fitted snug in a holster. It was too late!

OUT of the Stygian nothingness that surrounded their platform like a shoreless sea, another hive-shaped vehicle had materialized—a twin to the one in which Friar Bacon and the lad John had come. But it was cruder in material and workmanship. Even in that split second Fred noted that clumsy glass, cleverly welded into a single sheet, was its covering. The column by which it maneuvered through the dimensions seemed of fused Earthern crucibles, inclosed in a vacuum sheath of glass. Its glow' was duller, more subdued.

The vessel had floated to rest on the farther end of the platform. Its exterior shimmered wide, and a black figure glided forth—a being shaped like a man, though taller, dark as the void from which he had sprung. His face was pointed and elongated like one of Modigliani's painted creatures. His feet were clubbed and toeless. His eyes were slanting slits, and they flamed with furious fires.

"Mardu!" he screeched in a thin, eerie voice.

John, the son of Dominick, had fallen to his knees. "Domine, salve!" he shrieked. Roger Bacon pulled his cloak about his head, bent to the expected blast of extinction. Anne, close to the lever, seemed turned to stone.

Mardu, denizen of a strange dimension, saw Fred's swift motion. He saw the jerked-out muzzle of the gun. There was cold cruelty in his face, but there was also intelligence. He had never seen a gun before; his own weapon was a blast of energy built up out of space potential. Yet he knew that this inferior creature of a lesser world held a certain power of destruction. It might leap the intervening space before he could raise his hand. He took no chances.

With another screech he leaped. His long, boneless arms wrapped suddenly about the motionless girl. She screamed, struggled. But he was too powerful. Even as Fred leveled his gun despairingly, crashed forward to the rescue, Mardu had darted back into his vehicle, using Anne as a shield. From behind her squirming form his black, unjointed hand curled around the little ball.

Fred shot, directly for the glowing column.

The roar of the gun echoed deafeningly around the limited closure; smoke spumed from the muzzle. But the pointed dimension traveler was gone, catapulted into the circumambient void. And Anne and her captor, Mardu, had vanished with it.

Old Peartree stirred weakly. "He has taken Anne," he mumbled in a daze.

But Fred wasted no time. Grim-lipped, jaw tight with corded muscles, he whirled to the astounded Friar. "Quick!" he rasped. "Into the other machine! We're going after him."

Roger Bacon lowered his muffling robe. He made a gesture of utter futility. "But how can we?" he asked. "Already he is lost among the countless worlds."

"There must be a way," Fred said. "He managed to follow you, didn't he?"

John, son of Dominick, staggered to his feet. He shook with fear. "He will kill you," he cried. "He is Satan himself. His arm flashes lightnings."

Fred patted his holster grimly. "I, too, can flash lightnings on occasion. But this is no time to argue. We've got to make haste."

The thought of Anne, with her slim, pliant body, her bright, blue eyes, carried off by an alien creature into the unimaginable intervals of space time, was a searing torture to him. He knew now that he loved her—now that he had lost her forever.

"But——" started John.

"I'm not asking you to come along," Fred snapped. "Stay here with Pear-tree. You'll be safe with him."

The boy straightened. His eyes hardened with sudden maturity. "And lose all chance of ever seeing my Catherine again?" he said steadily. "Rather I'll take my risk with Mardu himself. I am coming."

"Good lad!" Fred approved. "Get in."

"Here!" the old scientist demanded in alarm. "How about me?"

"You've got to stay behind." Fred told him swiftly. "You won't be much help in a fight. And you'll have to keep this channel of communication open for us. Or else," he added with emphasis, "even if we do find Anne, we, too, will be wanderers through all eternity."

Then he swung inside, before Peartree could protest. "Let's start," he said.

Friar Roger Bacon took a deep breath. A prayer worked silently over his lips. Then lie twisted the ball.

THE incandescent column leaped into flaming life. A supernal glow blasted its depths. The crystal hive hazed, turned opalescent, then slowly cleared. The platform was gone; so was Childs Pear-tree and the apparatus he had evolved. Outside was nothingness—black as the pit, featureless, without form or substance. They seemed suspended in a shoreless void, where time and space and man himself had no meaning, no purpose.

"How can we ever find them in this?" John asked in despair.

But Fred Walcott was not listening. All his trained and critical intelligence was focused on the terrific problem before him. Quickly he learned whatever Friar Bacon could teach him of the mechanism of the interdimensional traveler. It was not much. The thirteenth-century man, philosopher, scholastic, groping scientist though he was, was not mentally equipped to grapple with the superscience of Mardu and his creation.

By trial and error he had discovered the method by which the slithering crystal ball controlled the column of heatless flame. That was all.

But Fred experimented, racing against a time that did not exist, feverishly bending every faculty to the task. While he blundered, Anne might already be lost forever in some unimaginable dimension.

He gave up at once the task of determining the nature of the energy column, of the materials of which the machine was composed. They were not of Earth, without doubt not of the universe in which Earth existed. Dimly, he sensed that here was an energy breakdown of the fundamental structure of subspace itself, the primitive continuum which underlay the space-time formulae of the several universes. But how it worked, how it shifted the hive-shaped structure from one dimension to another, through what patterned warp it operated, were beyond even his faculties. Nor was he interested just now. AH his being concentrated on the single task of tracking Mardu and the girl through the bewildering infinities in which they were enmeshed.

"There must be a way to trace his course," he said with quiet desperation. "Mardu knows it; he chased you from thirteeneth-century France to beyond the universe and back again."

"I do not know the method," Bacon declared with philosophic fatalism.

Fred flung himself intensely into the task. He turned and twisted the writhing ball; he searched every nook and cranny of the circumscribed inclosure—without success. He must have changed their hurtling flight a hundred times.

Once they flashed into a supernal blue in which worlds of fantastic geometric angles and curves spun and gyrated—and flashed out again: But no sign of Mardu, no sign of the method by which pursuit was possible.

As to a magnet, Fred returned time and again to the column of sourceless energy. Its smooth, shining surface raced with heatless flame. Fred considered it with furrowed brows. Somehow, within that lambent round——

WITH a cry, he leaned forward. The tiny sphere control hung quivering on the convexity. A thin hairline bisected it into hemispheres—so thin, so faint, he had not noted it before. With tentative finger nail, Fred tapped along the edge, seeking the inner mechanism. Even as he edged around, there was a tiny whir. The crystal ball swung open on a hemispherical axis. Its polished planes were opaque, and even as they stared, the surfaces clouded, cleared into miniature but mechanically perfect pictures.

Pictures of far-off universes, of vast nebula spiraling along the immensities, of triple and quadruple suns in intricate orbits, of huge life forms floating in the void, whose brooding intelligences caused the central column to flicker and fade with the impact of their mighty thoughts.

"I've got it," Fred shouted joyfully. "This is a subspace scanner, which picks up the energy flows of electron wave trains, and retranslates them into visual light." With taut fingers he swung the angle of the sphere.

The scene shifted to new quarters. A comet gleamed with pale, wild light, vanished. A city sprang into view, a jumble of strange towers and leaping fires. Creatures beyond human comprehension peopled its heights, swarmed out like bees in flight. Fred spun the angle.

Worlds tumbled on worlds; dimensions leaped into view and gave way in turn; space glittered like a whirling kaleidoscope, creation came and so did moveless death. But always Fred twisted the angles, seeking but one thing and one thing alone—the sight of a hive-shaped mechanism and of a black, ultradimensional creature and a slim, struggling girl within.

Then he saw them! In the remotest corner of the upper hemisphere, so infinitely remote that they were but microscopic pin points on a mosaic of endless universes. Yet even as he cried out fiercely, it seemed Mardu stared directly up at him with cruel mockery, and twisted the sphere. Like an evanescent mote in a beam of sunshine, they vanished into the illimitable inane.

Then—like an evanescent mote in a beam of sun-

shine—they vanished into the illimitable inane.

With grim intensity, Fred spun the scanning hemispheres through all the angles, caught them again. But even as he set the total sphere upon the. course, Mardu had dodged into nothingness again.

It became a game of hide and seek, a cosmic chase such as all the space times had never witnessed since the first creation—a deadly game in which Anne Howard was the pawn, and a thousand, thousand dimensions the field. They flashed through space of many colors; they startled strange civilizations with the apparition of their flight; they materialized within the depths of strange suns and stranger entities. And always Mardu, with his cruel grin, twisted and ducked, vanishing seconds or minutes or aeons—they had no means of judging time—before the space-crashing pursuit of his own machine.

John, son of Dominick, gaped like a fish at the dizziness of that terrific chase; even Friar Roger Bacon lost his philosophic calm and hunched over with blazing eyes. But Fred followed every vanishment, every sudden lurch into new spaces and new times, with remorseless rigor. He had the better machine, but Mardu was more skilled in operation. A sickening sensation overcame him.

He would never be able to catch up with the slippery prey. And sooner or later, in some unimaginable dimension, Mardu would achieve his native universe, would obtain the succor of his own kind, and blast Fred and his companions into dissipating nothingness.

ALL this while, a tiny, moveless doll, Anne Howard had crouched in the farthermost round of Mardu's machine, just as she had been flung in the first onslaught. Fred groaned his despair, thrust out his arm in a mute gesture of appeal to the pictured representation of the girl he loved. Her eyes lifted. They seemed to cling to his.

Slowly, Anne raised herself. Her slender body tightened like a drawn bow. She leaped with unleashed motion upon the huge black back of her captor. John, son of Dominick, cried out in unwitting, unheard encouragement, "A brave girl!"

Her impact staggered Mardu. His black paw wrenched at the sphere; he flung around to meet the attack. Then scene and all vanished, to give way to the featureless inane of some universe where space and time had not yet been created.

"She'll be killed," John gasped.

The old Friar groaned.

The sweat burst out in huge globules on Fred's forehead. Frantically, he turned the sphere, spun it round and round, trying to pick up the lost trail, to gain once more the sight of the struggling pair.

"There they are," the lad screamed. Fred stopped just in time. In his agony he had almost overleaped.

The girl was beating with vain, small fists upon the great bulk of her adversary. His mocking grin had given way to a soundless snarl of rage. He lifted his paw, clubbed her down with brutal blows. She sank quivering to the floor of the pictured cage. Fred, helpless, unimaginably remote, cursed frantically. But it was Roger Bacon who kept his wits about him. The gray-robed Franciscan Friar leaped to the control sphere, held it steady toward the far-distant scene.

Mardu straightened up from the motionless girl, grinning. Then his cruel eyes lighted with alarm. He sprang to his own sphere. It was too late. Directly alongside, spanning the intermediate dimensions, crashing into that alien space and time, materialized the pursuing trio.

His arm arced upward with the speed of light. But fast as he was, Fred Walcott was faster. The heavy Colt leaped from its holster, trigger pressed even as it leaped. The heavy bullet roared from the muzzle, slammed through the other-universe crystal, whizzed through a green-tinged space, splintered the farther glass of fused retorts, and caught Mardu, arm swinging upward, full in the forehead.

He fell backward, crashing into the ball control, hurtling into the column of incandescent glow. Flame sheeted outward; the vehicle expanded, burst into a thousand splintering shards.

"Protect us, Heavenly Father!" moaned John through whitened lips.

Fred jerked the ball madly. The side of their own conveyance misted, vanished.

Roger Bacon started forward with a cry of alarm. "Don't, my son! It is death what you intend."

But Fred had already catapulted out into the alien space. Through the flame and shifting smoke he saw the motionless form of Anne, floating in green-tinged nothingness as on a tideless sea.

His lungs filled to bursting. He gasped in the airless void. His hurtling body sped toward the limp girl; his hands groped out to catch her in fierce embrace. He seemed on fire with strange pricklings, with collapsing pressures. Perhaps this space was radioactive. There seemed no gravity. Far off, a rose-tinted world moved in the placid depths.

His brain was on fire, his lungs a gasping bellows. Anne was moveless in his arms—dead, perhaps. And he, too, was as good as dead. Fie thrashed arms and legs in frantic motion. He made no progress, could not. The pressures increased. He burned with torturing fires.

THEN something caught him, pulled. Air sighed past him with a thin whoosh; crystal materialized suddenly in front of him.

"Praise to the saints, my master lost not his head." John, son of Dominick, gasped heavily as he released his grip on the suffocated young man and the girl to whom he still clung with a fierce, unbreakable grip. "He manipulated the control so that we came alongside, and I was enabled to drag you both within."

The aged Friar shook his head sadly. "Aye, but we have lost much of precious air. It will be but a matter of little time before what is left will foul beyond endurance."

Anne moaned a little, opened her eyes. "Where am I?" she murmured. Then she saw Fred bending with agonized look, felt his strong arms tightening. She smiled faintly, happily, relapsed into unconsciousness.

Outside, in the strange green space, the exploded vessel drifted in a thousand scattered pieces. Amid the debris drifted, as well, Mardu, a round hole tunneled into his Stygian forehead.

Friar Bacon said with quiet resignation. "He is dead—devil or demon or whatever he was. No longer need we fear his eternal pursuit. You, Fred Walcott, man of my own Earth of a future time, have slain him for us. But to what profit? Even now the little remaining air grows stale, unbreathable. In but a few bare minutes we, too, shall be dead."

The young man deposited the girl gently on the floor. His mind raced. They must not die—not now! "How," he demanded tensely, "did you happen to crash through to our platform on Earth?"

The old man thought heavily. It was hard to think. There was a roaring in his brain from the lack of air. "I know not," he said with painful intake. "I know but that we two had despaired of all return, that I had held the crystal globe motionless in my hand while I had pondered what to do."

In one swift stride Fred was at the control, had gripped the shifting ball, held it taut. As he did so, the column waned and dulled to a mere thin phosphorescence. "That must be it," he gasped, fighting for breath. "You shut off the power unwittingly, and the break in space time that Peartree had engineered had drawn you through. If only——"

Light beat about them, brilliant, dazzling after the solid black to which they had become accustomed. Some one was shouting, incredulously, joyfully.

Fred blinked, grinned slowly. With utter recklessness he took a deep breath of the failing air.

Outside was the familiar platform, with Childs Peartree, his white hair tousled, wrestling frantically at the master lever. They had come home, home to Earth and the Peacock Mountains of Arizona, and the twentieth century!

THEY tried to persuade Friar Roger Bacon and young John, son of Dominick, to remain. The old Franciscan shook his head quietly. "This is not my time or age," he said. "I would be but a groping neophyte amid your marvels; I would never feel at home. Besides"—and his eyes glowed with a proud light—"I must tell my countrymen, the scholars I know, of what I have seen. Perhaps thus I may be able to remold my times nearer to truth and the future."

"And I"—the lad held himself very straight—"do wish to return to my pleasant village, and the, comely arms of my dearest Catherine."

"You will lose yourself once more in infinity," Fred declared. "Stay!"

"Nay!" answered the Friar confidently. "We shall return. I know more of the manipulation than I did before." Gravely, they shook hands; steadfastly, the pair stepped back into Mardu's machine. A final wave of farewell, a twist of the ball, and they had vanished into the black surrounding nonspace.

Fred held Anne tight to him, staring into the void with heartbreaking eyes. "They will never make it," he whispered huskily.

"But they did," answered Peartree. "Remember the Opus Major, the Opus Minor. In those ancient volumes are prophecies of our day, of the things which we explained to him."

Fred shook his head. "There is no mention of Mardu and the dimensional traveler. How do you account for that?"

"Easily! These volumes were written for the pope at his request. Nothing more was heard of them for many years. Very likely there was another manuscript, of such startling import that the pope ordered it hastily destroyed as stemming from the devil himself. Remember that Roger Bacon was soon thereafter imprisoned and held in close confinement, until, as a very old man, his mind tottering, he was released to die." Peartree's face clouded. "That," he said as if to himself, "is the common fate of pioneers."

He reached for the master lever. Slowly, it came up in reverse. The conglomerate of apparatus whined and hummed and buzzed. The circumscribing blackness gave way to gray. There was a roar of inrushing elements, of air and matter and energy and gravity. The platform rocked in the turmoil.

Then, as they clung close together in the whirling madness, sunshine blazed suddenly into the box canyon, and the mountains stared down upon them with eternal calm.

The experiment of Childs Peartree was over!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.